Abstract

The accumulation and fate of model microbial “pathogens” within a drinking-water distribution system was investigated in naturally grown biofilms formed in a novel pilot-scale water distribution system provided with chlorinated and UV-treated water. Biofilms were exposed to 1-μm hydrophilic and hydrophobic microspheres, Salmonella bacteriophages 28B, and Legionella pneumophila bacteria, and their fate was monitored over a 38-day period. The accumulation of model pathogens was generally independent of the biofilm cell density and was shown to be dependent on particle surface properties, where hydrophilic spheres accumulated to a larger extent than hydrophobic ones. A higher accumulation of culturable legionellae was measured in the chlorinated system compared to the UV-treated system with increasing residence time. The fate of spheres and fluorescence in situ hybridization-positive legionellae was similar and independent of the primary disinfectant applied and water residence time. The more rapid loss of culturable legionellae compared to the fluorescence in situ hybridization-positive legionellae was attributed to a loss in culturability rather than physical desorption. Loss of bacteriophage 28B plaque-forming ability together with erosion may have affected their fate within biofilms in the pilot-scale distribution system. The current study has demonstrated that desorption was one of the primary mechanisms affecting the loss of microspheres, legionellae, and bacteriophage from biofilms within a pilot-scale distribution system as well as disinfection and biological grazing. In general, two primary disinfection regimens (chlorination and UV treatment) were not shown to have a measurable impact on the accumulation and fate of model microbial pathogens within a water distribution system.

Biofilms are organized in highly efficient and stable ecosystems and play a major role in the sorption of planktonic microorganisms from the bulk water, including indicator bacteria as well as microbial pathogens (3, 11, 33). Furthermore, distribution pipe biofilms are also implicated in reducing the aesthetic (taste, color, and odor) and microbiological quality of water through the continual detachment of biomass into the bulk water. The importance of biofilm processes, including the attachment, penetration, and detachment of particles, has been recognized in recent years, and a range of studies investigating the fate of model pathogens and indicators such as coliforms (20, 21), legionellae (22), and viruses (27, 32) in a range of model water distribution systems have been undertaken. The limitation of these and similar studies, however, is that they have failed to apportion particle accumulation and loss to biological (i.e., inactivation and predation) and physical (i.e., detachment and disinfection) phenomena.

During the current investigation, the effects of two primary disinfection methods, chlorination and UV treatment, on biofilm biomass and the fate of particles within naturally grown biofilms were investigated. The primary disinfection of potable water by UV photolysis is thought to increase biologically available carbon and stimulate microbial activity compared to conventional chlorination and may therefore influence biofilm development in a distribution system (5). To investigate this, a novel pilot-scale water distribution system representative of the Stockholm drinking-water distribution system was constructed within the Lovö Waterworks, Sweden. Naturally grown biofilms were exposed to hydrophobic and hydrophilic fluorescent polystyrene microspheres, Salmonella bacteriophage 28B, and Legionella pneumophila bacteria, and their accumulation and persistence in biofilms were measured over a 38-day experimental period.

Fluorescent microspheres have been used as surrogate particles in a variety of applications to examine and quantify the accumulation and fate of particulate material within microbial biofilms and are favored for their similarity to bacteria in size and cell surface properties as well as their resistance to biodegradation and disinfection (4, 6, 10, 19, 23, 24, 29). The latter two properties were exploited in this investigation to allow the separation of biological, i.e., loss in culturability, grazing from physical phenomena such as detachment. To compare the behavior of these particles to living bacterial cells, legionellae were also chosen as a bacterial model and pathogen. Legionellae have an advantage over microspheres in that they are living particles and furthermore have a distinct elongated morphology that can be easily resolved from indigenous biofilm bacteria. In addition to standard culture techniques, the quantification of legionellae was also performed directly by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

Enteric viruses provide a greater water-borne health concern than bacteria and are generally more resistant to disinfection (1, 2) and even more so when associated with sediments (8, 16, 28) and biofilms (27, 32). As a model for enteric virus behavior within a water distribution system, bacteriophages were used in the current study. Bacteriophages share many characteristics with human enteric viruses, such as size and morphology, as well as resistance to and persistence within conventional water treatment processes (12, 13).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

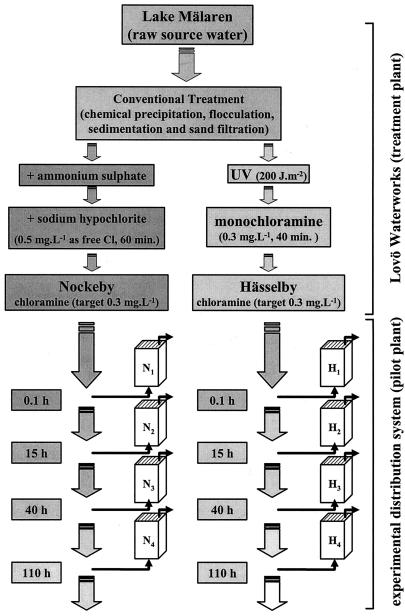

Two study sites within the Stockholm area were investigated. Hässelby district, which currently receives drinking water that has undergone UV treatment, and Nockeby district, which receives water treated with chlorine as a primary disinfectant. Raw water undergoes conventional treatment at the Lovö waterworks, including chemical precipitation by Al2(SO4)3 and flocculation, sedimentation, rapid and slow sand filtration prior to disinfection, and distribution at a target total chlorine residual of 0.3 mg liter−1 to the Nockeby and Hässelby districts (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic of the Lovö Waterworks and pilot-scale water distribution system. Identical systems, both chloraminated prior to distribution, were primarily disinfected by chlorination (Nockeby, left, N) and UV treatment (Hässelby, right, H). Biofilm sampling chambers were placed at locations N1 to N4 and H1 to H4, equating to water residence times of 0.1, 15, 40, and 110 h within the Stockholm distribution system, respectively, in each case.

Pilot-scale water distribution system and biofilm sampling devices.

Two pilot-scale water distribution systems comprised 1 km of 50-mm polyethylene tubing that was connected directly to the finished water. Biofilm sampling devices (chambers), equipped with 20 exchangeable glass slides, were located at various distances along each pilot-scale system equating to residence times of 0.1, 15, 40, and 110 h within the main Stockholm distribution system (Fig. 1, N1 to N4 and H1 to H4). The volume of each biofilm chamber was 215 ml, and water flowed through each up-flow device in a single pass at a rate of 12 liters h−1. The combined chlorine concentration was measured in each device with a Hach De100 chlorine monitor (Hach Industries Pty Ltd.).

Preparation of inocula and addition of particles.

Natural biofilms were allowed to develop on glass surfaces for a period of 8 weeks. Biofilm chambers were then exposed to 1.0-μm hydrophobic (sulfate modified) (total, 2.8 × 109) and hydrophilic (carboxylate modified) (3.3 × 109) fluorescent polystyrene microspheres (Molecular Probes), as well as L. pneumophila (ATCC 31215) (2.5 × 1010) and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium 28B somatic bacteriophages (9.5 × 1010). L. pneumophila had previously been cultivated on BCYE agar (Oxoid Pty Ltd., Hampshire, United Kingdom) after incubation at 36 ± 1°C for 72 h and adapted to oligotrophic conditions at 4°C for a further 72 h.

For the propagation of somatic 28B bacteriophages, an overnight culture of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium type 5 was inoculated with 28B bacteriophages in a colony-to-PFU (CFU:PFU) ratio of 1:1 and incubated for 18 ± 2 h at 37°C. Following incubation, NaCl was added to the mixture to a final concentration of 1 M to induce complete cell lysis, and the lysate was sonicated for 2 min to disrupt intact cells and disaggregate bacteriophages. The cell lysate was then clarified by centrifugation for 20 min at 4,500 × g (15°C) (SLA 3000 rotor) in a Sorvall RC5C Plus centrifuge (Kendro Laboratory Products Inc., Axeb AB Sollentuna, Sweden). Biofilm chambers were then isolated from the feed water, and the inocula (containing legionellae, bacteriophages, and spheres) was recirculated throughout each biofilm chamber by a peristaltic pump for a period of 24 h (day 0). After this time, each chamber was reconnected to feed water and operated in single-pass flow. The results from day 1 (24 h following the conclusion of the inoculation period) were used for the purpose of quantifying particle accumulation.

Biofilm sampling and microbial analysis.

On sampling days 1, 2, 6, 12, and 38, triplicate slides were removed from all sampling devices and placed in stomacher bags containing 20 ml of one-quarter-strength Ringer solution. The bags were sealed and placed on ice prior to further laboratory processing (within 2 h). Biofilm was removed from slide surfaces with sterile cell scrapers (TPP, Gothenburg, Sweden) and then homogenized in a stomacher (BagMixer, Interscience, St. Nom, France) for 1 min. The day prior to dosing (day 0), triplicate glass slides were removed from each chamber, the biofilm was collected as described above, and the number of biofilm bacteria in an 8-week-old biofilm that was to be exposed to microspheres, legionella, and bacteriophages was assessed by 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining (1 μg ml−1, 10 min) and direct epifluorescence microscopy on a Zeiss Axioskop microscope (Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany). This procedure was repeated for biofilms at the conclusion of the experimental period (day 38).

For the enumeration of fluorescent microspheres, appropriate volumes of biofilm homogenate were filtered with a 0.2-μm black polycarbonate membrane (Millipore Corp.) and viewed directly by epifluorescence microscopy. Homogenates were also used for assaying culturable L. pneumophila on BCYE agar (36 ± 1°C for up to 10 days) as described (15), and the results were expressed as CFU cm−2. L. pneumophila was also directly enumerated by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), following fixation in 3.7% formaldehyde at 4°C for 4 h, washed once, resuspended, and stored in phosphate-buffered saline with ethanol (1:1) at −20°C until enumeration by epifluorescence microscopy. For FISH analysis 10 μl of these samples was air dried in wells on Teflon-covered slides (Novakemi AB). The preparations were ethanol dehydrated, hybridized with the Cy3-conjugated 16S rRNA probe LEG705 (Genset Oligonucleotides Inc., Paris, France), a general probe specific for the family Legionellaceae (18), and incubated for 4 h at 46°C in a humidified chamber. Samples were washed thoroughly and enumerated by epifluorescence microscopy with filter set 41007a (545 and 610 nm; Chroma Technology Corp.). Grazers were identified by DAPI staining and epifluorescence microscopy and could be visualized as free-living protozoa containing bacterial cells.

The bacteriophages were enumerated from homogenates by a pour-plate dual-agar method on modified Scholtens agar (MSA) according to ISO Method 10705-2 (14) with the host strain S. enterica serovar Typhimurium type 5. Assimilable organic carbon (AOC) analyses were performed according to the method described by van der Kooij et al. (34) with the following amendments. Duplicate 500-ml samples were heated overnight at 60°C in Extran-washed bottles. After this time, samples were inoculated with Pseudomonas fluorescens strain P17 and incubated at 20°C. Colony counts were enumerated on nutrient agar by the drop-plate method after 3, 7, and 14 days at 20°C. AOC values were calculated with the yield coefficient for P. fluorescens of 4.1 × 106 CFU per μg of C (as acetate). For statistical evaluation and comparison of the data, the removal rates (k) of bacteria, bacteriophages, and spheres were described in terms of first-order inactivation with log10.

RESULTS

The concentration of combined chlorine decreased with increasing residence time, ranging from 0.17 and 0.25 mg liter−1 for H1 and N1 (residence time 0.1 h) to 0.03 and 0.01 mg liter−1 at the end of the pilot-scale water distribution systems, respectively (sites H4 and N4) (Table 1). Free chlorine could not be detected in either pilot-scale system. The pH of finished water within both pilot-scale water distribution systems was in the range of 7.5 to 8.5 and was independent of sampling location. The water temperature ranged from 5.2°C to 8.2°C, increasing with residence time throughout either system.

TABLE 1.

Combined chlorine (NH4Cl) (n = 4), temperature (n = 4), and total direct counts (TDC) of biofilm cells at day 0 (TDC0) and day 38 (TDC38) (n = 3) and AOC (n = 3) and grazers (n = 4) at sampling sites N1 to N4 and H1 to H4 representing residence times between 0.1 and 110 ha

| Site | Residence time (h) | NH4Cl (mg liter−1) | Temp (°C) | TDC0 (104 cm−2) | TDC38 (104 cm−2) | AOC (μg liter−1) | Grazers (cells cm−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | 0.1 | 0.17 ± 0.05 | 5.2 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 37 ± 16 | 79 ± 23 |

| N2 | 15 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 7.8 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 29 ± 20 | 391 ± 373 |

| N3 | 40 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 8.0 ± 0.7 | 16.0 ± 2.4 | 20.3 ± 2.2 | 26 ± 7 | 2,030 ± 1710 |

| N4 | 110 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 8.2 ± 0.8 | 9.5 ± 2.3 | 10.4 ± 0.7 | 27 ± 4 | 828 ± 172 |

| H1 | 0.1 | 0.25 ± 0.06 | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 38 ± 16 | <1 |

| H2 | 15 | 0.05 ± 0.04 | 7.1 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 25 ± 10 | 243 ± 12 |

| H3 | 40 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 7.3 ± 0.6 | 22.0 ± 1.1 | 23.3 ± 1.4 | 36 ± 15 | 567 ± 161 |

| H4 | 110 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 7.6 ± 0.7 | 10.0 ± 0.8 | 10.4 ± 0.8 | 28 ± 5 | 1,010 ± 737 |

All values are expressed ± 1 standard deviation.

Biofilm coverage on glass slide surfaces ranged from monolayers comprised of randomly located bacteria to complex aggregates and microcolonies. Biofilm thickness did not exceed 10 μm. Legionellae and salmonellae could not be detected in biofilms by culture or direct (FISH) methods prior to inoculation of the system. The total number of bacterial cells in the biofilms ranged from 1.4 × 104 to 2.2 × 105 cells cm−2 increasing significantly (P < 0.001) at sites N3 and H3 (40 h). At the sites representing a residence time of 110 h (N4 and H4), the numbers were also significantly higher than at the beginning of either system, however, significantly (P < 0.001) lower than at N3 and H3 (Table 1). When the corresponding sites of the two systems were compared, there was a trend of greater numbers of biofilm bacteria in the chlorinated (Nockeby) than in the UV-treated (Hässelby) system sites, except at distal sites (N4 and H4). The numbers of biofilm bacteria detected at the conclusion the experiment (day 38) were at virtually the same level as at day 0 (P ≥ 0.084) (R2 = 0.9726 for the Nockeby and 0.9901 for the Hässelby system) (Table 1).

Accumulation of microspheres.

The results from day 1 (24 h following the conclusion of the inoculation period) were used for the purpose of quantifying the numbers of accumulated model particles (legionellae, viruses, and microspheres). These numbers were normalized to 103 cells cm−2 of the initial biofilm density and also expressed as a percentage of the total number of dosed particles per total surface area in the slide chambers (Table 2). The number of accumulated hydrophobic microspheres per total surface represented 0.1 to 0.8% of the total number dosed (2.8 × 109) (Table 2). Normalized to biofilm density by 103 cells cm−2, hydrophobic microspheres accumulated within the biofilms on the order of 10 to 102 particles cm−2 (Table 2) with no significant difference found between sites within the UV-treated system (Hässelby) (P > 0.090). Significantly lower numbers of accumulated hydrophobic spheres (P = 0.015) were found at distal sites compared to proximal ones within the chlorinated (Nockeby) system.

TABLE 2.

Accumulation of microspheres, legionellae, and bacteriophages in biofilmsa

| Site | No. of hydrophobic spheres cm−2 | No. of hydrophilic spheres cm−2 | No. of culturable legionellae CFU cm−2 | FISH-positive legionellae cm−2 | Phages (PFU cm−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | 411 ± 311 (0.2) | 2,860 ± 1,580 (1.1) | 0.1 ± 0.2 (<0.001) | 32,900 ± 7,600 (1.7) | 4 ± 6 (<0.001) |

| N2 | 528 ± 372 (0.4) | 1,990 ± 502 (1.1) | 78 ± 18 (0.006) | 24,800 ± 8,000 (1.8) | 26 ± 5 (<0.001) |

| N3 | 57 ± 11 (0.3) | 142 ± 12 (0.6) | 1,810 ± 530 (1.6) | 6,000 ± 220 (3.4) | 5 ± 3 (<0.001) |

| N4 | 32 ± 8 (0.1) | 110 ± 37 (0.3) | 4840 ± 1910 (1.2) | 8,300 ± 1,000 (2.8) | 7 ± 2 (<0.001) |

| H1 | 151 ± 31 (0.2) | 713 ± 108 (0.6) | 15 ± 17 (0.002) | 21,200 ± 3,900 (2.4) | 21 ± 13 (<0.001) |

| H2 | 114 ± 23 (0.2) | 630 ± 24 (0.7) | 2 ± 3 (<0.001) | 13,200 ± 4,800 (2.0) | 7 ± 2 (<0.001) |

| H3 | 107 ± 69 (0.8) | 147 ± 126 (0.9) | 540 ± 390 (0.4) | 2,400 ± 27 (1.9) | 4 ± 2 (<0.001) |

| H4 | 91 ± 66 (0.3) | 172 ± 113 (0.5) | 2,700 ± 990 (1.0) | 4,100 ± 1,100 (1.6) | 6 ± 2 (<0.001) |

Mean values were normalized to 103 biofilm bacterial cells and expressed ± 1 standard deviation (n = 3) on day 1 of the experiment. Accumulated particles are also presented as a percentage (in parentheses) of the total number of dosed hydrophobic spheres (2.8 × 109), hydrophilic spheres (3.3 × 109), legionellae (2.5 × 1010), and Salmonella 28B bacteriophages (9.5 × 1010) per total surface area of the slide chambers (glass slide surface included).

The corresponding accumulation of hydrophilic spheres per total surface area within sampling devices represented 0.3 to 1.1% of the total number dosed (3.3 × 109) (Table 2). The hydrophilic spheres accumulated at one order of magnitude greater (102 to 103 particles cm−2) than hydrophobic spheres (Table 2). A significant decrease (P ≤ 0.045) in the accumulation of hydrophilic spheres occurred within both systems over the length of the pilot-scale water distribution system, however, no differences occurred between the two systems, with the exception of N2, where there were significantly more hydrophilic spheres than at H2 (P = 0.009).

Accumulation of legionellae.

The numbers of culturable legionellae accumulated in biofilms increased significantly (P ≤ 0.004) in both systems with increasing residence time (and decreasing combined chlorine concentration) (Table 2) with the exception of H2. Significantly higher (P ≤ 0.042) accumulation of legionellae was found in biofilms in the chlorinated Nockeby system compared to the UV-treated Hässelby system (except for proximal sites N1 and H1). The numbers of legionellae accumulated by biofilms as detected by FISH showed a pattern opposite that observed for culturable legionellae and almost identical to that of polystyrene microspheres (Table 2). No significant difference in the accumulation of FISH-positive legionellae in biofilms was found between the proximal sites (N1 and N2 as well as H1 and H2). At the distal sections, the total numbers of legionellae accumulated by biofilms (as enumerated by FISH) decreased significantly (P < 0.09) in both systems, as did fluorescent microspheres.

Accumulation of bacteriophages.

Low-level accumulation of bacteriophages was observed in biofilms representing, per unit of glass slide surface, 0.0001% of the total number dosed (9.5 × 1010) (Table 2). Within the chlorinated Nockeby system, only site N2 had significantly (P = 0.003) higher numbers of biofilm-accumulated bacteriophages compared to other sites (P < 0.09). Within the UV-treated Hässelby system, a significant difference between sites could not be established. In a pairwise comparison between the sites of the two systems, only N2 had significantly higher numbers of bacteriophages accumulated in biofilms than H2 (P = 0.004).

Persistence of microspheres, legionellae, and bacteriophage.

The results from days 2 to 38 were used for the purpose of quantifying the numbers of persistent model particles (legionellae, bacteriophages, and microspheres). No significant difference was observed in the loss of fluorescent microspheres from biofilms in the systems over the course of the experimental period (P ≥ 0.067). Reduction in bacteriophage numbers in biofilms was however generally higher in the UV-treated Hässelby system (k = 0.1 to 0.5) than in the chlorinated Nockeby system (k = 0.06 to 0.1) (Table 3), with a slightly lower reduction at distal sites in both pilot-scale water distribution systems (k = 0.08).

TABLE 3.

Decay constant (k) for fluorescent microspheres, Legionella bacteria, and bacteriophagesa

| Fluorescent microspheres

|

Legionellae (FISH)b | Method and site | Phages | Legionellae (culture) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobica | Hydrophilicb | ||||

| Chlorination | |||||

| <0.01 (0.01) | <0.01 (0.02) | 0.03 (0.81) | N1 | 0.06 (0.31) | 0.03 (0.01) |

| 0.04 (0.69) | 0.03 (0.66) | 0.04 (0.82) | N2 | 0.10 (0.95) | 0.28 (0.81) |

| 0.03 (0.43) | 0.04 (0.53) | 0.02 (0.41) | N3 | 0.11 (0.63) | 0.15 (0.55) |

| 0.03 (0.30) | 0.03 (0.42) | 0.01 (0.31) | N4 | 0.08 (0.84) | 0.10 (0.73) |

| UV treatment | |||||

| H1 | 0.26 (0.96) | <0.01 (0.01) | |||

| H2 | 0.10 (0.87) | 0.06 (0.06) | |||

| H3 | 0.50 (0.71) | 0.11 (0.47) | |||

| H4 | 0.08 (0.91) | 0.08 (0.88) | |||

The correlation coefficient (R2) for each decay constant is provided in parentheses.

No significant difference between Nockeby and Hässelby. Results for both have been combined.

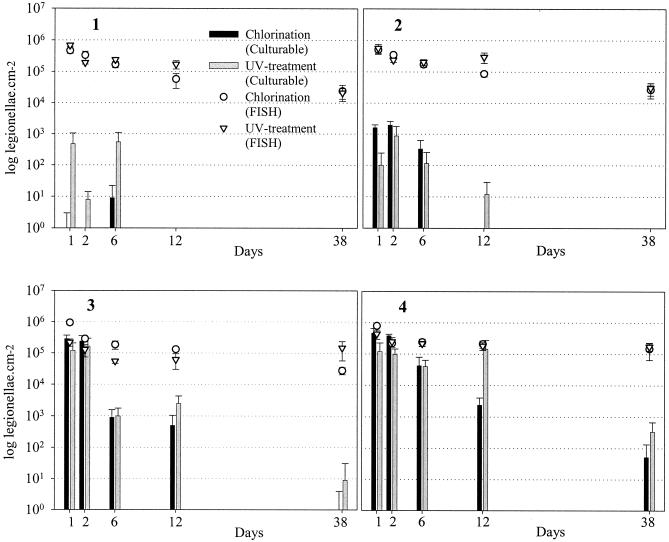

Chlorine disinfection had its greatest efficacy against L. pneumophila at the beginning of each system, with a greater than 5-log10 initial inactivation of culturable cells at H1 and N1 and 2.5 logs at H2 and N2, decreasing significantly at distal sites in the distribution systems (Fig. 2) (P < 0.05). At the proximal sites of both systems, there was no decrease in the number of culturable cells observed over the first 2 days, increasing to between 2 and 2.5 logs after 12 days and greater than 3 logs at the conclusion of the experimental period. Regrowth of legionellae during the current investigation did not occur since the temperatures were low (5.0 to 8.5°C). A combined chlorine concentration exceeding 0.2 mg liter−1 was sufficient to inhibit the establishment of culturable L. pneumophila within the pilot-scale water distribution system.

FIG. 2.

Culturable and total (FISH-positive) L. pneumophila located within biofilms in the chlorinated (Nockeby) and UV-treated (Hässelby) pilot-scale water distribution systems at sites 1 to 4, equating to residence times of 0.1, 15, 40, and 110 h, respectively, within the greater municipal system. Culturable and total L. pneumophila were enumerated over a 38-day period and expressed per square centimeter of coupon surfaces. Error bars, 1 standard deviation.

The number of L. pneumophila detected by standard culture methods often represented a small fraction of those that could be enumerated by FISH (Fig. 2). The ratio of culturable to total (FISH-positive) cells in Nockeby and Hässelby ranged from 0.002% (N1) and 0.07% (H1) to 58% (N4) and 65% (H4) on day 1 of the experimental period. At the conclusion of the experimental period (38 days), these figures ranged from 0% (N1 and H1) to 0.1% (N4) and 0.26% (H4). Despite the absence of culturable cells at the conclusion of the experimental period, FISH-positive cells were detected in both systems at all sites during this time. The reduction in FISH-positive cells represented 75 ± 25% of the original amount despite a 5-log reduction in culturable cells over the same period.

DISCUSSION

Biofilms can range in size from single scattered cells and monolayers 1 to 5 μm in depth to thick structures of several hundred micrometers (35). The total number of biofilm bacteria reported within potable water distribution systems varies naturally but is generally on the order of 107 cells cm−2 (17, 25, 26). In this study, sparse biofilm coverage on glass surfaces was observed. The elevated numbers of biofilm bacteria at distal sites in each system may be attributed in part to the absence of a measurable disinfectant residual (≤0.03 mg liter−1). Furthermore, the number of grazers observed strongly suggested that biofilm bacteria were affected by the grazing activity of free-living protozoa (predominantly amoebae) (Table 1), which adds to other microbial interactions within distribution pipe biofilms (3). No direct correlation between the number of biofilm bacteria and the AOC concentration could be determined.

Although hydrophilic spheres demonstrated an accumulation pattern different from that of the hydrophobic spheres in this study, the number of either could not be positively correlated to the bacterial counts in biofilms (R2 = 0.4). In general, at sites where biofilms were thinner, higher number of fluorescent microspheres attached to the substrata. As biofilm density increased on the slide surfaces, the number of attached spheres decreased significantly (P ≤ 0.045). Incorporation of particles into biofilms is dependent on the physical properties of the biofilm as well as the surface properties of the particulate matter and substrata (9, 30). The inference here is that the physicochemical properties of both the microspheres and the substratum influenced the accumulation of the hydrophobic spheres to a greater degree than biofilm density. Similar results have been reported, where no correlation between biofilm thickness and incorporation of fluorescent microspheres has been found (6, 23, 24, 29).

The significantly higher number of culturable legionellae accumulated by biofilms in both systems with increasing distance from the point of distribution demonstrated the effects of combined chlorine on their colonization. The correlation between attached culturable legionellae and indigenous biofilm bacteria at distal sites of both systems demonstrated that the accumulation of legionellae was more dependent on biofilm density rather than substrata. An incoherent relationship was observed between accumulated FISH-positive and culturable legionellae, where the former demonstrated a pattern almost identical to that of polystyrene microspheres. Culturable legionellae represented a small fraction of those that could be detected by FISH. While the exact human health significance of this finding remains unclear, it does suggest that the current detection by standard culture may not adequately describe the incidence of legionellae within a water distribution system.

Bacteriophages were accumulated by biofilms in similar numbers throughout the distribution system, suggesting that influences other than biofilm biomass (i.e., direct interaction with substrata and resistance to disinfection) may have governed their fate (27, 31, 32).

The minimal decrease in the number of fluorescent microspheres observed at sites over the course of the experimental period could be attributed to detachment (or desorption), as concluded by Eisenmann et al. (7). The physicochemical properties of both the microspheres and the substratum may therefore have influenced their fate. Despite a difference in initial accumulation, the loss of hydrophilic spheres was identical to that of hydrophobic spheres.

Despite differences in their initial accumulation, desorption in addition to loss of plaque-forming ability was the phenomenon most likely influencing the fate of bacteriophages over the course of the experimental period. The low numbers of 28B bacteriophages recovered from biofilms at sites H1 and N1 could be explained in part by the minimal biomass coverage on coupon surfaces. In other systems examined, the retention of bacteriophages has been shown to be a function of biofilm biomass (32). The effects of disinfection could not be discounted, however, since the number of bacteriophages increased with increasing residence time in either pilot-scale system.

A combined chlorine concentration exceeding 0.2 mg liter−1 was deemed sufficient to inhibit the establishment of culturable L. pneumophila within the pilot-scale water distribution system. The loss of FISH-positive cells, which closely resembled that of fluorescent microspheres, lends further weight to the assumption that the fate of culturable legionellae within the system is best described in terms of loss of culturability rather than physical desorption.

During the current investigation, the influence of primary disinfection methods (chlorination versus UV treatment) on biofilm growth could not be resolved, with biomass as determined by total direct counts, in each system found to be statistically similar. Furthermore, the nature of the primary disinfectant (UV and chlorine) was not found to influence the persistence (removal rate k) of bacteriophages and microspheres from the pilot-scale distribution system, though it did influence culturable legionellae. Their different rates of decay in the two different systems could not be clearly explained. Together with the finding that legionellae when assessed by direct (FISH) methods behaved almost identically to spheres in terms of both accumulation and persistence implies that in microbiological studies, spheres can function as an adequate surrogate for bacterial cells. Protozoan grazers punctuated the biofilms and in most cases contained many legionellae as well as microspheres. Biological grazing by free-living protozoa could therefore at least partially account for the loss of microspheres and legionellae, though further work will investigate the exact nature and size of this contribution.

Many of the processes involved in the behavior of pathogens and other particulates in a municipal water distribution system are generally unknown or at best poorly understood. The use of a range of model “pathogen” types permitted us to separate cause-and-effect relationships for the accumulation and fate of these particles, describing them in terms of biological (i.e., inactivation and predation) and physical (i.e., detachment) phenomena. The current study has demonstrated that desorption is one of the primary mechanisms affecting the fate of microspheres, legionellae, and bacteriophages in biofilms within a pilot-scale distribution system, followed by disinfection and biological grazing.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted as a part of the MISTRA research program “Sustainable Urban Water Management” (www.urbanwater.org), whose financial support is gratefully acknowledged. We also acknowledge all valuable financial and technical assistance provided by Stockholm Water, with particular thanks given to Ulf Eriksson and Bengt Göran Hellström for their invaluable cooperation and assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abad, F. X., R. M. Pintó, C. Villena, W. Gajardo, and A. Bosch. 1977. Astrovirus survival in drinking water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3119-3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackmer, F., K. A. Reynolds, C. P. Gerba, and I. L. Pepper. 2000. Use of integrated cell culture-PCR to evaluate the effectiveness of poliovirus inactivation by chlorine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2267-2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Block, J. C., K. Haudidier, J. L. Paquin, J. Miazga, and Y. Levi. 1993. Biofilm accumulation in drinking water distribution systems. Biofoul 6:333-343. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiou, C.-F., M. Torres-Lugo, B. J. Marinas, and J. Q. Adams. 1997. Nonbiological surrogate indicators for assessing ozone disinfection. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 89:54-66. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corin, N., P. Backlund, and T. Wiklund. 1998. Bacterial growth in humic waters exposed to UV-irradiation and simulated sunlight. Chemosphere 33:242-255. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drury, W. J., P. S. Stewart, and W. G. Characklis. 1993. Transport of 1-μm latex particles in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 42:111-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenmann, H., I. Letsiou, A. Feuchtinger, W. Beisker, E. Mannweiler, P. Hutzler, and P. Arnz. 2001. Interception of small particles by flocculent structures, sessile ciliates, and the basic layer of a wastewater biofilm. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4286-4292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferguson, C. M., A. M. de Roda Husman, N. Altavilla, D. Deere, and N. J. Ashbolt. 2003. Fate and transport of surface water pathogens in watersheds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 33:299-361. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flemming, H.-C. 1995. Sorption sites in biofilms. Water Sci. Technol. 32:27-33. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flood, J. A., and N. J. Ashbolt. 2000. Virus-sized particles can be entrapped and concentrated one hundred fold within wetland biofilms. Adv. Environ. Res. 3:403-411. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford, T. E. 1999. Microbiological safety of drinking water: United States and global perspectives. Environ. Health Perspec. 107191-7206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grabow, W. O. K. 2001. Bacteriophages: update on application as models for viruses in water. Water SA 27:251-268. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Havelaar, A. H., M. Butler, S. R. Farrah, J. Jofre, E. Marques, A. Ketratanakul, M. T. Martins, S. Ohgaki, M. D. Sobsey, and U. Zaiss. 1991. Bacteriophages as model viruses in water quality control. Water Res. 25:529-545. [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Organization for Standardization. 2002. Detection and enumeration of bacteriophages. 2. Enumeration of somatic coliphages. ISO-10705-2. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 15.International Organization for Standardization. 2002. Water quality-detection and enumeration of Legionella. ISO-11731. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 16.La Belle, R. L., and C. P. Gerba. 1979. Influence of pH, salinity, and organic matter on the adsorption of enteric viruses to estuarine sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 38:93-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LeChevallier, M. W., T. M. Babcock, and R. G. Lee. 1987. Examination and characterization of distribution system biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:2714-2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manz, W., R. I. Amann, R. Szewzyk, U. Szewzyk, T.-A. Stenström, P. Hutzler, and K.-H. Schleifer. 1995. In situ identification of Legionellaceae using 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes and confocal laser scanning microscopy. Microbiology 141:29-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mariñas, B. J., J. L. Rennecker, S. Teefy, and W. W. Rice. 1999. Assessing ozone disinfection with nonbiological surrogates. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 91:79-89. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMath, S. M., C. Sumpter, D. M. Holt, A. Delanoue, and A. H. L. Chamberlain. 1999. The fate of environmental coliforms in a model water distribution system. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 28:93-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Momba, M. N. B., T. E. Cloete, S. N. Venter, and R. Kfir. 1999. Examination of the behaviour of Escherichia coli in biofilms established in laboratory-scale units receiving chlorinated and chloraminated water. Water Res. 33:2937-2940. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murga, R., T. S. Forster, E. Brown, J. M. Pruckler, B. S. Fields, and R. M. Donlan. 2001. Role of biofilms in the survival of Legionella pneumophila in a model potable-water system. Microbiology 147:3121-3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okabe, S., H. Kuroda, and Y. Watanabe. 1998. Significance of biofilm structure on transport of inert particulates into biofilms. Water Sci. Technol. 38:163-170. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okabe, S., T. Yakuda, and Y. Watanabe. 1997. Uptake and release of inert fluorescence particles by mixed population biofilms. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 53:459-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olson, B. H., and L. A. Nagy. 1984. Microbiology of potable water. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 30:73-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedersen, K. 1990. Biofilm development on stainless steel and PVC surfaces in drinking water. Water Res. 24:239-243. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quignon, F., L. Kiene, Y. Levi, M. Sardin, and L. Schwartzbrod. 1997. Virus behaviour within a distribution system. Water Sci. Technol. 35:311-318. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rao, V. C., K. M. Seidel, S. M. Goyal, T. G. Metcalf, and J. L. Melnick. 1984. Isolation of enteroviruses from water, suspended solids, and sediments from Galveston Bay: survival of poliovirus and rotavirus adsorbed to sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48404-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reichert, P., and O. Wanner. 1997. Movement of solids in biofilms-significance of liquid phase transport. Water Sci. Technol. 36321-328. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stoodley, P., Z. Lewandowski, J. D. Boyle, and H. M. Lappin-Scott. 1999. Structural deformation of bacterial biofilms caused by short-term fluctuations in fluid shear an in situ investigation of biofilm rheology. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 645:84-92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Storey, M. V., and N. J. Ashbolt. 2003. Enteric virions and microbial biofilms-a secondary source of public health concern? Water Sci. Technol. 48:97-104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Storey, M. V., and N. J. Ashbolt. 2001. Persistence of two model enteric viruses (B40-8 and MS-2 bacteriophages) in water distribution pipe biofilms. Water Sci. Technol. 43:133-138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szewzyk, U., R. Szewzyk, W. Manz, and K.-H. Schleifer. 2000. Microbiological safety of drinking water. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:81-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Kooij, D., A. Visser, and W. A. M. Hijnen. 1982. Determining the concentration of easily assimilable organic carbon in drinking water. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 74:540-545. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wimpenny, J., W. Manz, and U. Szewzyk. 2000. Heterogeneity in biofilms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24:661-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]