Abstract

Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) is known to have diverse effects on brain structure and function, including the promotion of stem cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus. However, the intracellular pathways downstream of the IGF-1 receptor that contribute to these diverse physiological actions remain relatively uncharacterized. Here, we demonstrate that the Ras-related GTPase, RIT1, plays a critical role in IGF-1-dependent neurogenesis. Studies in hippocampal neuronal precursor cells (HNPCs) demonstrate that IGF-1 stimulates a RIT1-dependent increase in Sox2 levels, resulting in pro-neural gene expression and increased cellular proliferation. In this novel cascade, RIT1 stimulates Akt-dependent phosphorylation of Sox2 at T118, leading to its stabilization and transcriptional activation. When compared to wild-type HNPCs, RIT1 −/− HNPCs show deficient IGF-1-dependent Akt signaling and neuronal differentiation, and accordingly, Sox2-dependent hippocampal neurogenesis is significantly blunted following IGF-1 infusion in knockout (RIT1 −/−) mice. Consistent with a role for RIT1 function in the modulation of activity-dependent plasticity, exercise-mediated potentiation of hippocampal neurogenesis is also diminished in RIT1 −/− mice. Taken together, these data identify the previously uncharacterized IGF1-RIT1-Akt-Sox2 signaling pathway as a key component of neurogenic niche sensing, contributing to the regulation of neural stem cell homeostasis.

Introduction

Adult neurogenesis is a dynamic process in which new neurons are generated from neural stem/progenitor cells (NPCs) through the carefully orchestrated regulation of proliferation and neuronal fate determination. Adult born neurons have the ability to functionally integrate into the hippocampal circuitry and have been found to contribute to select types of hippocampal-dependent learning and memory tasks1. A critical feature of adult neurogenesis is its regulation by diverse physiological, pathological, and pharmacological stimuli, including exercise, aging, traumatic brain injury, epilepsy, and antidepressants2. NPCs are normally quiescent, but once activated are capable for self-renewal to maintain the neural stem cell population and to produce dividing progenitors capable of differentiating into neurons3–5. Significantly, the maintenance and proliferation of adult NPCs, and the differentiation, migration, and maturation of adult born neurons, are known to be regulated by extracellular growth factor signaling pathways6, 7. Growth factor signaling is known to control a variety of intracellular regulatory mechanisms within NPCs, including transcription factors and epigenetic regulators that serve to finely coordinate gene expression during neurogenesis2. For example, the transcription factor Sex-determining region Y related HMG box 2 (Sox2) has well-established roles in maintaining stem cell/progenitor cell properties in diverse cellular populations8, 9, including neuronal stem cell self-renewal and neurogenesis10.

Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) signaling has been implicated in the regulation of adult neurogenesis11–13. For example, conditional deletion of the IGF-1 receptor gene (Igf1r) results in an almost complete loss of the dentate gyrus (DG) in mice14 while exogenous IGF-1 promotes enhanced HNPC proliferation15, 16, and directs the generation of mature granule cells15–18. These effects rely on the ability of activated IGF-1R to activate diverse intracellular regulatory cascades, including the ERK MAP kinase and PI3-kinase/Akt pathways19, 20. In particular, Akt signaling has been reported to play a central role in IGF-1-mediated HNPC proliferation and neuronal differentiation21–24. IGF-1/Akt signaling is also known to control neuronal transcription factor activity22, 25, however the nature of the specific transcriptional pathway(s) involved in IGF-1 dependent neural stem cell activation remain incompletely characterized.

Running is a particularly potent instigator of hippocampal neurogenesis with evidence from human and animal research indicating that exercise improves hippocampal function, synaptic plasticity, learning, and modulates depression26. Lineage tracing studies27 have demonstrated that voluntary exercise increases the number of Sox2+ neural stem cells in the DG, and importantly, pharmacological inhibition of Akt has been found to inhibit exercise-mediated enhancement of adult hippocampal neurogenesis28, 29. Since, exercise increases the availability of several classes of growth factors, including IGF-130, this work suggests a link between physiological/growth factor cues, Akt signaling, and the regulation of neurogenesis. The discovery of signaling pathways that enhance adult neurogenesis may lead to therapeutic strategies for improved memory function due to aging or following injury. Therefore, it is important to develop a detailed molecular understanding of these cascades.

The Ras-related GTPase, RIT1, is expressed throughout the central nervous system and within the developing brain31–33. Despite its widespread expression, RIT1 function remains incompletely characterized34. We have previously demonstrated that RIT1 serves as a central regulator of stress-activated MAPK activity and pro-survival signaling35. In keeping with a role in directing survival signaling, adult born immature neurons lacking RIT1 display significantly increased rates of trauma-induced loss following contusive brain injury36. Surprisingly, RIT1 knockout (RIT1 −/−) mice also exhibit a significant delay in the innate restoration of neurogenesis following brain injury36, suggesting that RIT1 controlled signaling contributes to the period of enhanced hippocampal neurogenesis observed following brain insult37. More recently we identified somatic RIT1 mutations in a subset of human lung adenocarcinomas, and found that ectopic expression of mutated RIT1 in cell culture activates Akt signaling and promotes cellular transformation38. Importantly, expression of oncogenic RIT1 also stimulates the Akt-dependent proliferation of HNPCs39. Here, we demonstrate the physiological importance of RIT1 function by establishing a role for RIT1 in both IGF-1 dependent control, and exercise-enhanced stimulation, of hippocampal neurogenesis. Using in vivo and in vitro genetic strategies to manipulate RIT1 function, we find that IGF-1 stimulates a RIT1-Akt-Sox2 signal transduction cascade in HNPCs that leads to increased neurogenesis. In this pathway, RIT1-Akt activity results in phosphorylation of Sox2 at T118, to increase Sox2 transcriptional activity, enabling IGF-1 directed activation of the neurogenic program.

Results

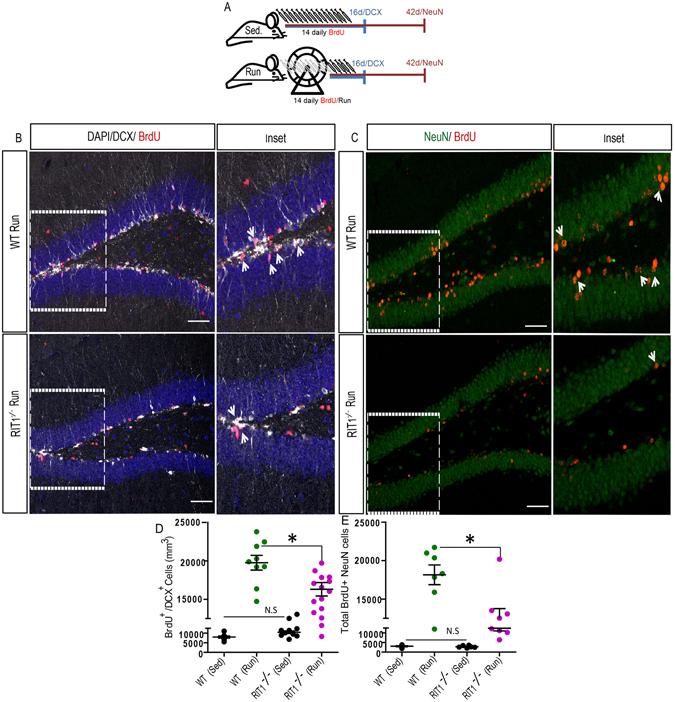

Loss of RIT1 alters exercise-induced neurogenesis

We have shown that RIT1 deficiency alters hippocampal neurogenesis following traumatic brain injury by delaying the post-concussive recovery of immature neurons without affecting basal rates of neurogenesis36. However, whether RIT1 contributes to the regulation of adult neurogenesis more broadly in response to physiological stimuli is unknown. Importantly, RIT1 is known to be expressed in HNPCs, supporting a potential role for RIT1 in the regulation of neural progenitor function39. To assess the role of RIT1 in voluntary exercise-enhanced hippocampal neurogenesis40, RIT1 knockout (RIT1 −/−) (n = 17) and wild-type (n = 23) mice were randomly assigned to either sedentary or running groups (running wheels were preinstalled in the housing cages permitting voluntary exercise), and the impact of RIT1 loss on exercise-enhanced neurogenesis assessed at either day 16 or 42 (Fig. 1A). Both wild-type and RIT1 −/− mice in the runner groups ran an average distance of ~10 kilometers a day with no inherent difference arising from RIT1 deficiency (wild-type: 10.25 ± 1.14 km/d; RIT1 −/−: 10.10 ± 0.59 km/d, p = 0.86, n = 3). During the trial, mice received one daily intraperitoneal BrdU injection (50 mg/kg) for the first 2 weeks, to label proliferating neuroblasts (BrdU+/DCX+ cells) (analysis day 16) (Fig. 1B) and maturing neurons (analysis day 42; 1 month post-BrdU chase) (BrdU+/NeuN+) (Fig. 1C). While lineage tracing detected approximately equivalent numbers of BrdU labeled proliferating neuroblasts (p > 0.05) and mature neurons (p > 0.05) in sedentary housed mice (p > 0.05), RIT1 −/− mice displayed a significantly lower density of proliferating neuroblasts (*p < 0.01), and neurons that matured from these neuroblasts following running exercise than wild-type controls (*p = 0.01) (Fig. 1D,E). These data suggest that RIT1 signaling contributes to the proliferation and neuronal differentiation following voluntary exercise.

Figure 1.

Adult neurogenesis in RIT1 −/− and WT littermates housed under running conditions. (A) Schematic of experimental design (see methods for details). WT and RIT1 −/− mice were injected daily with BrdU (50 mg/kg, i.p) for 14 days while housed in either sedentary or running cages and either analyzed for newborn neuroblasts (DCX+/BrdU+) (day 16) or the generation of mature neurons (NeuN+/BrdU+) (day 42). Representative coronal hippocampal sections from the dentate gyrus of (B) 16d mice immunostained for DCX (white, pseudocolor), BrdU (red, white arrowheads) and DAPI, or (C) 42d mice co-immunostained with NeuN (green) and BrdU (red; white arrowheads). The inserts are at higher magnification. The arrow heads indicate either newborn neuroblasts (B) or mature neurons (C). Scale bar, 20 μm. (D) Quantitative analysis of newborn immature hippocampal neurons (BrdU+/DCX+) following 16 days of running or sedentary housing (*p < 0.01, two-way ANOVA). (E) Quantitative analysis of BrdU+ mature neurons (NeuN+) at day 42 (*p < 0.01, two-way ANOVA). The results are presented as mean ± SEM (WT, n = 17; RIT1 −/−, n = 23).

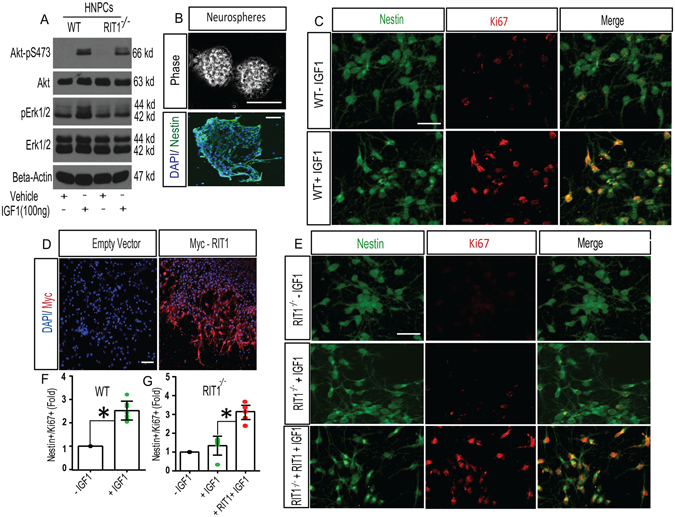

RIT1 contributes to IGF-1 dependent neurogenesis

Running exercise increases the availability of several classes of growth factor, including BDNF and IGF-1, which have known roles in regulating adult neurogenesis30. While RIT1 plays a role downstream of diverse mitogen-activated receptors34, we have previously shown that BDNF signaling in primary hippocampal neuron cultures is not altered by RIT1 deficiency36. In agreement with earlier in vitro studies41, IGF-1 exposure (100 ng/ml, 15 min) led to robust ERK and Akt activation in wild-type hippocampal cultures (Fig. 2A). Importantly the activation of both kinases was blunted (~55% of kinase phosphorylation of WT hippocampal neuronal cultures, n = 3, p < 0.05) in RIT1 −/− cultures as monitored by anti-phospho-specific immunoblotting (Fig. 2A). Consistent with a role for RIT1 in IGF-1 signaling, wild-type primary hippocampal neural progenitor cells (HNPCs) (Fig. 2B) displayed increased proliferation (p < 0.01) following IGF-1 exposure (Fig. 2C,F), while RIT1 −/− HNPCs failed to respond (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2E,G), as assessed by confocal microscopy (co-stained Nestin+/Ki67+ cells). Expression of Myc-tagged RIT1 rescued IGF-1 dependent proliferation in RIT1 −/− HNPCs (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2D,E and G). These data suggest that RIT1 plays a key role in IGF-1 signaling and contributes to HNPC proliferation in vitro.

Figure 2.

RIT1 loss disrupts IGF-1-mediated in vitro HNPC proliferation. (A) Lysates from cultured WT and RIT1 −/− HNPC cultures were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies following IGF-1 stimulation (100 ng/ml; 15 min). Representative images were cropped from the original blots run in parallel. (B) Phase contrast and immunocytochemical detection of Nestin (green) and DAPI (blue) of neurospheres clonally expanded from the dentate gyrus of wild-type mice. (C) Proliferation of WT HNPCs was assessed by immunocytochemical detection of Nestin (green) and Ki67 (red) 24 h following stimulation with or without IGF-1 (50 ng/ml). Scale bar, 15 μm. (D) Representative confocal images of transfected Myc-tagged RIT1 (red) expression in dissociated WT HNPCs. Scale bar, 10 μm. (E) Transfected RIT1 −/− HNPCs (Myc-tagged RIT1 or empty vector) were left untreated or stimulated with IGF-1 (50 ng/ml) and proliferation was assessed at 24 h by immunohistochemical detection of Nestin (green) and Ki67 (red). Scale bar, 15 μm. (F,G) Quantification of IGF-1 mediated HNPC proliferation (Nestin+/Ki67+)/200 cells counted from 5–6 fields in WT (*p < 0.05 nonparametric one tailed t-test), RIT1 −/−, and following re-expression of Myc-RIT1 in RIT1 −/− HNPCs (*p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). Results are presented as mean ± SEM calculated from three separate experiments.

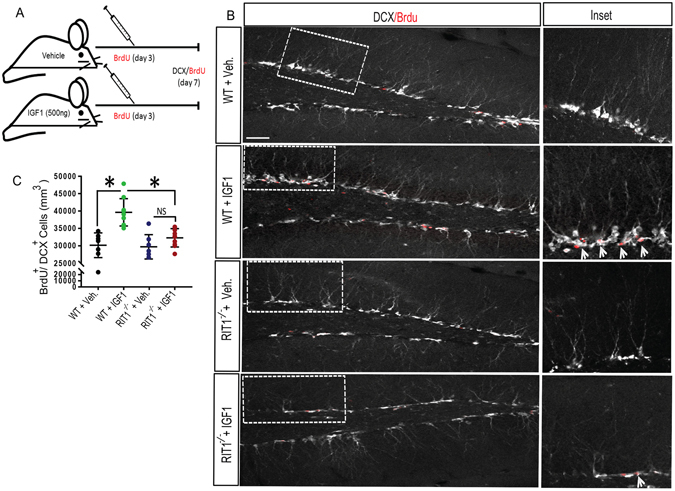

We next asked whether RIT1 signaling contributes to IGF-1-dependent in vivo stimulation of hippocampal neurogenesis15. In agreement with previous studies15, 16, 18, peripheral infusion of exogenous recombinant IGF-1 (500 ng/kg/day) (Fig. 3A) was found to induce neurogenesis in the mouse hippocampus (Fig. 3B). Using BrdU labeling, we found a significant increase in newborn BrdU+/DCX+ immature neurons in the dentate granule cell layer of the hippocampus of WT mice after 7 d of peripheral IGF-1 administration, when compared to vehicle controls (Fig. 3B,C). While vehicle treated WT and RIT1 −/− mice displayed similar numbers of BrdU+/DCX+ newborn immature neurons, IGF-1 dependent progenitor cell proliferation was significantly blunted in the dentate of RIT1 −/− mice (Fig. 3B,C) (p < 0.05). Taken together, both in vivo and in vitro data indicate that RIT1 plays a critical role in IGF-1 induced neurogenesis.

Figure 3.

RIT1 deficiency impairs IGF-1-dependent adult neurogenesis. (A) WT and RIT1 −/− mice (n = 10 per genotype) were continuously administered either rhIGF-1 (500 ng/kg/day) or vehicle via subcutaneous pump infusion for 1 week. At day 3 of infusion, mice were i.p. injected with BrdU (50 mg/kg) (×4) over 12 h. (B) Representative coronal hippocampal sections co-immunostained for BrdU (red) and DCX (white) (Scale bar 20 μm). The inserts are at higher magnification. Arrowheads (white) indicate newborn DCX+/BrdU+ neuroblasts. (C) Quantification of the BrdU+/DCX+ proliferating neuroblast density (cell counts/mm3) within the dentate gyrus of WT and RIT1 −/− mice (*p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA). Results are presented as mean ± SEM.

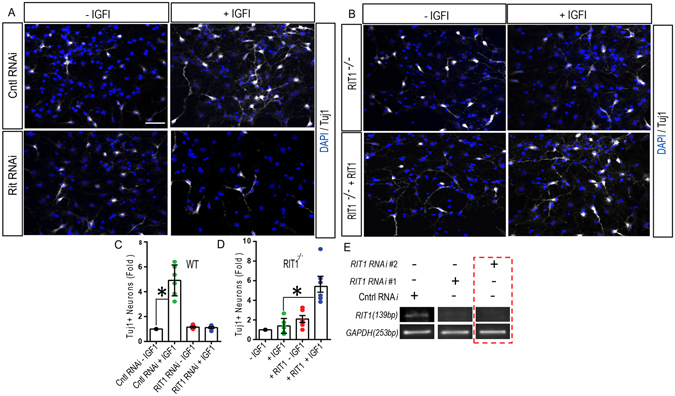

IGF-1 regulates neurogenic transcription factor expression in HNPCs

IGF-1 has been shown to direct the differentiation of hippocampal NPCs to mature granule neurons17, and IGF-1 treatment of wild-type HNPC cultures significantly increased the number of Tuj1+ neurons (Fig. 4A,C) (p < 0.05). In keeping with a central role for RIT1 in IGF-1 signaling, the ability of IGF-1 to stimulate HNPC neuronal induction was significantly blunted following RNAi-mediated RIT1 silencing (Fig. 4A,C and E), resulting in significantly fewer Tuj1+ neurons when compared with HNPC cultures treated with control RNAi (p < 0.05). Similar results were seen in cultured RIT1 −/− HNPCs, in which IGF-1 stimulation failed to promote the robust neuronal differentiation observed in WT cultures (Fig. 4B,D). Importantly, the neurogenic deficit in RIT1 −/− HNPCs could be rescued by re-expression of Myc-tagged RIT1 (Fig. 4B and D) (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

RIT1 knockdown impairs IGF-1-dependent neural induction of HNPCs. (A) WT HNPC cultures were left untreated (-IGF1) or treated with IGF-1 (50 ng/ml, 24 h) following infection with either control (Cntl) or RIT1-RNAi lentivirus and co-immunostained with Tuj1 (white, pseudo color) and DAPI (nuclei; blue) (Scale bar 10 μm). (B) RIT1 −/− HNPCs were transfected with or without Myc-tagged RIT1 and co-immunostained with Tuj1 (white, pseudocolor) and for nuclei (DAPI: blue) following vehicle or IGF-1 stimulation (50 ng/ml, 24 h). (C,D) Quantification of Tuj1+ cells (n = 500 cells from 5–6 random fields) in HNPCs following either lentiviral-mediated RIT1 knockdown, or gene rescue in RIT1 −/− HNPCs, with or without IGF-1 stimulation (*p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). (E) RT-PCR analysis of lentiviral-mediated RIT1 RNAi silencing efficiency in HNPCs. RIT1#2 RNAi was used in all subsequent studies.

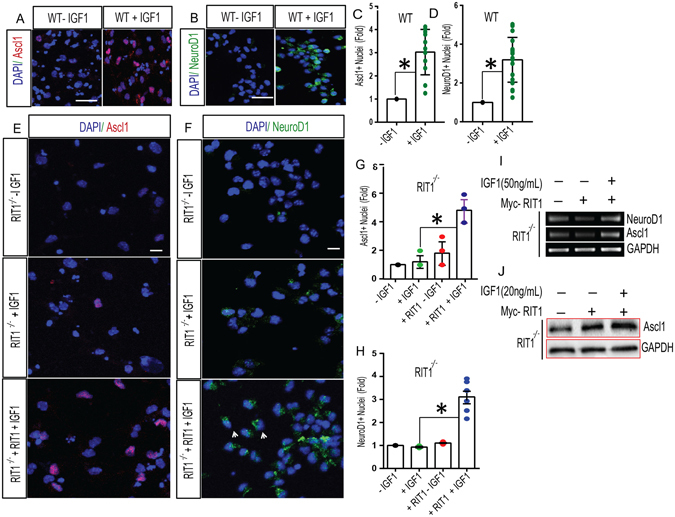

Adult neurogenesis involves the activation of a multistep transcriptional network42 including the sequential expression of Ascl143 and NeuroD144, 45 transcription factors. To determine whether IGF-1 stimulation of HNPCs results in the activation of this transcriptional cascade, we used immunohistochemical analysis to determine the effect of IGF-1 on Ascl1 and NeuroD1 expression in HNPCs. As seen in Fig. 5, IGF-1 stimulation of HNPCs (50 ng/ml IGF-1, 24 h) resulted in a prominent increase in both Ascl1 (Fig. 5A and C) and NeuroD1 (Fig. 5B and D) expressing HNPCs. Consistent with a role for RIT1 in this process, IGF-1 stimulation failed to significantly increase levels of either Ascl1 or NeuroD1 in RIT1 −/− HNPCs (Fig. 5E–H) (p > 0.05), but importantly, Myc-RIT1 re-expression was capable of restoring IGF-1-dependent increases in both transcription factors (Fig. 5E–H) (p < 0.05). Consistent with these data, RT-PCR analysis demonstrates that IGF-1 stimulation leads to an increase in the expression of both NeuroD1 and Ascl1, in a manner that depends upon RIT1 (Fig. 5I). Furthermore, immunoblotting demonstrates a RIT1-dependent increase in Ascl1 protein levels following IGF-1 (20 ng/ml) stimulation in HNPCs (Fig. 5J). Thus, RIT1 deficiency blunts IGF-1-dependent regulation of pro-neurogenic gene expression and neural differentiation of HNPCs.

Figure 5.

Role for RIT1 in IGF-1-dependent neuronal differentiation. (A,B) Representative confocal images of Ascl1 (red) and NeuroD1 (green) expression in WT HNPCs with or without IGF-1 (50 ng/ml, 24 h) stimulation. Scale bar, 20 μm. (C,D) Quantification (n = 200 cells from 5–6 fields) of Ascl1+ or NeuroD1+ neural precursor cells in WT HNPCs with or without IGF-1 stimulation (*p < 0.05, nonparametric one tailed t-test). (E,F) Representative confocal images of Ascl1+ (red) and NeuroD1+ (green) cells in RIT1 −/− HNPCs or RIT1 −/− HNPCs following re-expression of Myc-RIT1, with and without IGF-1 stimulation (50 ng/ml, 24 h). Scale bar, 15 μm. (G,H) Quantification of Ascl1+ precursors (*p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA) and NeuroD1+ neuronal precursors (*p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA) following RIT1 complementation with or without IGF-1 stimulation. (I) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR demonstrates IGF-1-mediated increases in NeuroD1 and Ascl1 expression in RIT1 −/− HNPCs following RIT1 complementation. Representative images of the gene bands were cropped from the original agarose gels. (J) Representative Western blot showing RIT1-dependent increase in Ascl1 protein following IGF-1 (20 ng/ml) stimulation of RIT1 −/− HNPCs. Representative images of the protein bands were cropped from the original blots run in parallel. Results are presented as mean ± SEM calculated from three separate experiments.

IGF-1 regulates SOX2 stability and transcriptional activity in HNPCs

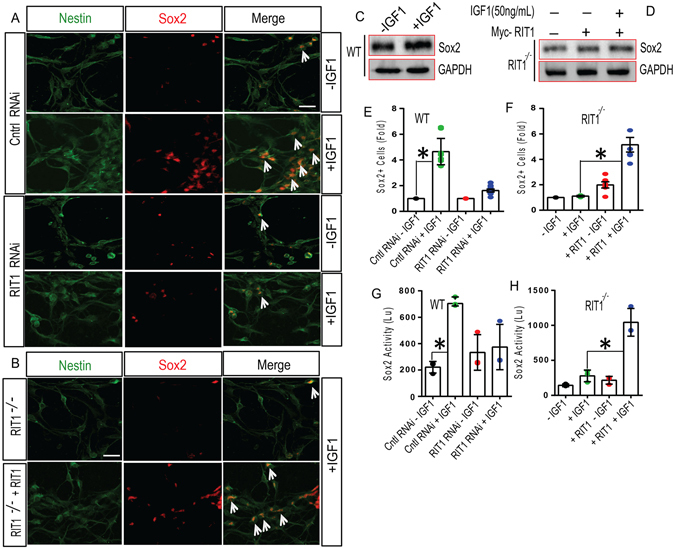

Recent work has shown that the transcription factor SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 2 (SOX2), is expressed by adult NSCs, and required both for the maintenance of NPC pluripotency and in establishing the epigenetic state required for neuronal differentiation in response to neurogenic cues46. We have recently found that constitutively activate RIT1 is capable of stimulating SOX2-dependent gene expression39. To evaluate whether RIT1-SOX2 signaling contributes to IGF-1-dependent neurogenesis, we analyzed the effect of IGF-1 on SOX2 protein levels in HNPCs. As seen in Fig. 6, IGF-1 (50 ng/ml, 24 hrs) stimulation of wild-type HNPCs resulted in a prominent increase in SOX2+ cells (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6A,E), and SOX2 protein levels (Fig. 6C). RNAi-dependent RIT1 silencing blunted the IGF-1 mediated increase in SOX2 protein levels (Fig. 6A,E) (p < 0.05). A similar result was seen in IGF-1 stimulated RIT1 −/− HNPCs (Fig. 6B,D,F), with re-expression of RIT1 capable of restoring the IGF-1-dependent increase in SOX2 levels (Fig. 6B,D,F) (p < 0.05). Importantly, robust SOX2 transcriptional activity was observed in wild-type HNPCs following IGF-1 stimulation (50 ng/ml) (p < 0.01), but failed to induce SOX2 reporter activity in HNPCs following RNAi-mediated RIT1 silencing (Fig. 6G). Similar results were seen in RIT1 −/− HNPCs with the deficit in SOX2 transcriptional activity rescued by re-expression of wild-type RIT1 (p < 0.1) (Fig. 6H). Taken together, these data suggest that IGF-1-dependent hippocampal neurogenesis involves a RIT1-SOX2 signaling cascade.

Figure 6.

RIT1 contributes to IGF-1-mediated Sox2 stabilization and transcriptional activation. (A) Representative confocal images of Sox2+ cells from WT HNPC cultures left untreated (-IGF1) or treated with IGF-1 (50 ng/ml; 24 h) (Scale bar, 15 μm) following infection with either control (Cntl) or RIT1-directed RNAi (RIT1#2) and co-immunostained with Nestin (green) and Sox2 (red). The arrowheads (white) indicate HNPCs that express Sox2. (B) Representative micrographs of Sox2 expression in RIT1 −/− HNPCs, with and without re-expression of Myc-RIT1 following IGF-1 (50 ng/ml; 24 h) stimulation (Scale bar 15 μm). (C) Immunoblotting for SOX2 in WT HNPCs with or without stimulation with IGF-1 (50 ng/ml; 24 h). Representative images were cropped from the original blots run in parallel. (D) Immunoblotting for SOX2 levels in RIT1 −/− HNPCs in the presence of transiently transfected Myc-RIT1 and IGF-1 stimulation (50 ng/ml; 24 h). Representative images were cropped from the original blots run in parallel. (E,F) Quantification (fold-change) of Sox2+ cells in the indicated HNPC cultures following IGF-1 stimulation (50 ng/ml; 24 h) are presented as mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). (G,H) Quantification of Sox2 luciferase reporter activity in cultured WT, RIT1 −/−, or RIT1 −/− HNPCs following Myc-RIT1 complementation, with or without IGF-1 stimulation (50 ng/ml, 24 h) are presented as mean ± SEM from three separate experiments (*p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA).

IGF-1/RIT1/Akt-dependent SOX2-T118 phosphorylation during neuronal induction

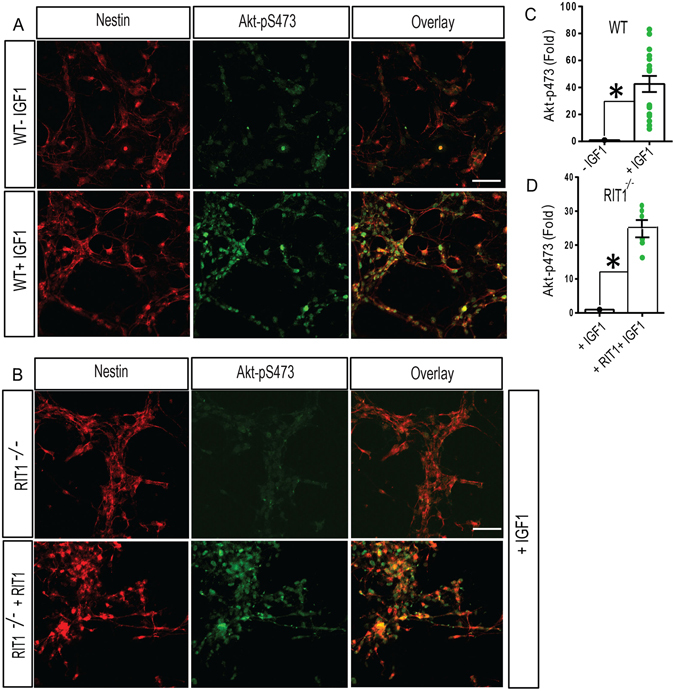

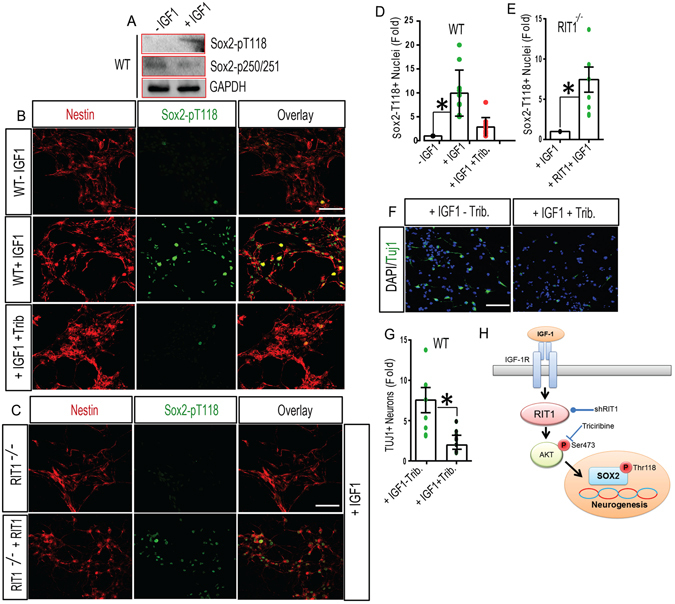

Recent studies have found that SOX2 is regulated by a methylation-phosphorylation switch, in which phosphorylation at T118 stabilizes the SOX2 protein and enhances its transcriptional activity in embryonic stem cells47. Whether a similar mechanism operates to control SOX2 during hippocampal neurogenesis is unknown, but since neural expression of active RIT1 promotes SOX2-T118 phosphorylation39, we hypothesized that this cascade contributes to IGF-1 dependent SOX2 activation in HNPCs. In support of this notion, we observed IGF-1-dependent stimulation of Akt activity in wild-type HNPCs, as detected by phospho-specific AktS473 immunofluorescence (Fig. 7A,C) (p < 0.01). In agreement with our earlier data (Fig. 2A), RIT1 −/− HNPCs displayed blunted Akt activation (Fig. 7B,D) (p < 0.01) which could be rescued by RIT1 re-expression (Fig. 7B,D). Western blotting found that IGF-1 exposure dramatically increased the phosphorylation of SOX2 at T118 while the phosphorylation at Ser25/Ser251 was unaffected (Fig. 8A). Confocal laser scanning microscopy also showed higher number of phospho-SOX2-T118+ nuclei in wild-type HNPCs (Fig. 8B,D) (p < 0.05). Pharmacological blockade of Akt signaling with Triciribine48 inhibited the number of phospho- SOX2-T118+ nuclei following IGF-1 stimulation (Fig. 8B,D). IGF-1-dependent SOX2-T118 phosphorylation was also blunted in RIT1 −/− HNPCs, and this deficit could be complemented by expression of exogenous RIT1 (Fig. 8C,E). The loss of SOX2 in adult HNPCs has been shown to decrease the expression of pro-neural genes, compromising the differentiation of newborn neurons46. Importantly, Akt inhibition significantly reduced the number of Tuj1+ neurons in IGF-1 treated HNPC cultures (Fig. 8F,G) (p < 0.01). Taken together, these data indicate that IGF-1 directs a downstream RIT1-Akt-SOX2 signaling cascade to regulate neurogenesis (Fig. 8H).

Figure 7.

RIT1 contributes to IGF-1-mediated Akt activation. (A,B) Representative confocal images of WT, RIT1 −/−, or RIT1 −/− HNPCs completed by re-expression with Myc-RIT1. HNPC cultures were co-immunostained for phospho-Akt S473 (green) and Nestin (red) following vehicle or IGF-1 stimulation (50 ng/ml; 24 h). Scale bar, 20 μm. (C,D) Quantification of phospho-Akt S473 levels following IGF-1 stimulation of the indicated HNPC cultures is presented as mean ± SEM calculated from three separate experiments (*p < 0.01, nonparametric one tailed t-test).

Figure 8.

IGF-1-dependent Sox2 phosphorylation relies on RIT1-Akt signaling. (A) Immunoblotting for levels of Sox2 phospho-Ser250/Ser251 and SOX2 phospho-T118 with and without IGF-1 stimulation (50 ng/ml; 24 h). Representative images were cropped from the original blots run in parallel. (B,C) Representative confocal images of phospho-Sox2 T118+ nuclei in WT, RIT1 −/−, or RIT1 −/− HNPCs complemented by re-expression of Myc-RIT1 left untreated (-IGF-1) or 24 h after stimulation with IGF-1 (50 ng/ml) or co-stimulated with IGF-1 and the Akt inhibitor Triciribine (3 µM Trib.) and immunostained for phospho-Sox2 T118 (green) and Nestin (red). Scale bar, 20 μm. (D,E) Quantification of Nestin+/Sox2 T118+ cells following IGF-1 stimulation of WT HNPCs with or without Akt inhibition (1–4 uM Trib.) (*p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA) or IGF-1 stimulation of RIT1 −/− HNPCs with or without RIT1 complementation (*p < 0.05, nonparametric one tailed t-test) (≥200 cells counted from 5–6 fields). (F) Representative confocal images of HNPCs co-immunostained for Tuj1+ (green) and DAPI (nuclei, blue) following IGF-1 (50 ng/ml) stimulation with or without Akt inhibition (1–4 uM Trib.). (G) Quantification of Tuj1+ neurons in WT HNPCs following IGF-1 stimulation (50 ng/ml) ± Triciribine (3 μM) (≥500 cells from 5–6 fields) (*p < 0.05, nonparametric t-test). Data are presented as mean ± SEM calculated from three separate experiments. (H) Schematic diagram of the putative IGF-1/RIT1/Akt/Sox2 signal transduction cascade. The sites of pharmacological inhibition (⊥) and the target of shRNA silencing reagents (•) are indicated.

Discussion

Studies in the mammalian central nervous system support an essential role for insulin and insulin-like growth factors in stem cell self-renewal, neurogenesis, and cognitive function through distinct ligand-mediated receptor activation cascades13. Although IGF-1 has long been associated with the regulation of neural stem cell biology, and much is known about the diversity of IGF-1-dependent signaling cascades19, mechanisms by which IGF-1 governs neurogenesis remain incompletely characterized. Here, we provide evidence for the involvement of RIT1 as a critical downstream component of IGF-1-dependent, and exercise-mediated enhancement, of hippocampal neurogenesis. We demonstrate that, IGF-1 regulates Sox2 activation and neuronal differentiation in a RIT1-dependent fashion in HNPCs, with RIT1 directing IGF-1-mediated expression of the pro-neuronal Ascl1 and NeuroD1 genes, and Akt-dependent up-regulation of Sox2 transcriptional activity. Thus, we demonstrate that RIT1/Akt signaling plays a crucial role in IGF-1 dependent neural cell fate selection by controlling Sox2 function.

During both CNS development and adult neurogenesis, IGF-1/IGF-1R signaling has been found to regulate the proliferation and survival of neuronal progenitors as well as the generation, differentiation, and maturation of neurons11, 12, 18, 49–51. Circulating IGF-1 has been implicated in the beneficial effects of exercise on brain function, including increased hippocampal neurogenesis15, 52. Previous findings have also identified roles for IGF-1 signaling in neuronal precursor proliferation and neuronal differentiation24, 53–56. Our results provide new insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying exercise-enhanced and IGF-1-driven hippocampal neurogenesis. The blunted neurogenic response of exercised RIT1 −/− mice suggests that RIT1 participates in the transduction of running stimuli to promote enhanced hippocampal neurogenesis, whether in response to IGF-1 or another exercise myokine57, 58. Not surprisingly, RIT1 deficiency does not result in a complete block of exercise-enhanced neurogenesis (Fig. 1), as neurogenesis is controlled by a broad and sophisticated regulatory network6. Indeed, other Ras-related G-proteins are likely involved, as Ras-GRF2, a calcium-regulated exchange factor for Ras and Rac GTPases, has been found to contribute neurogenesis in response to enriched environment59. However, the failure of IGF-1 infusion to stimulate neuroblast proliferation in RIT1 −/− mice suggests that RIT1 plays an essential role in IGF-1 dependent regulation of hippocampal neurogenesis, as other Ras family GTPases cannot compensate for RIT1 loss. While a number of studies have implicated elevated IGF-1 levels as a putative mediator of exercise induced neurogenesis15, 52, and our data would support a role for IGF-1/RIT1 in the benefits of exercise on brain plasticity, a growing literature suggests that a variety of factors beyond IGF-1 likely contribute to this process. Indeed, recent studies have identified the exercise myokine, cathepsin B (CTSB)58, as an important mediator of the neurogenic benefits of exercise, and additional peripheral blood factors have been shown to improve brain plasticity in aged animals57. Therefore, further studies are needed to determine whether RIT1, or other Ras family GTPases, contribute to these signaling pathways.

A growing literature supports a central role for Akt is the regulation of neuronal stem cell proliferation60, 61, including the control of exercise-mediated hippocampal neurogenesis28, 62 and IGF-1 signaling in neuronal stem cells22, 41, 63. Our observation that IGF-1-mediated ERK and Akt activity is blunted in RIT1 −/− HNPC cultures (Fig. 2), but not following BDNF stimulation36, suggests that RIT1 deficiency might generate an IGF-1 selective, rather than global, defect in growth factor signaling within the HPNC niche. While these data implicate RIT1 as a key downstream regulator of neuronal IGF-1 signaling, the full contribution of RIT1 to IGF-1 signal transduction remains to be addressed, particularly details on how RIT1 deficiency impacts gene expression. In addition, it is important to identify the guanine nucleotide exchange factor(s) (GEF) involved in coupling IGF-1R activation to stimulation of neuronal RIT1 signaling. This is complicated by the fact that while activation of a SOS/Shc-Grb2 complex has been associated with in vitro RIT1 activation following either NGF or PCAP stimulation of pheochromocytoma cells, biochemical analysis has yet to identify a bona fide RIT1GEF. IGF-1 has been shown to be neuroprotective in models of traumatic brain injury64, 65, stroke and ischemic injury66, 67, preventing apoptotic death and promoting cell survival. As expression of active RIT1 has been shown to be neuroprotective in vitro 37, studies are underway to determine activated RIT1 signaling is neuroprotective, capable of reducing behavioral deficits in the setting of brain trauma.

Sox2 is involved in the maintenance and proliferation of NPCs in vivo, neurosphere formation in vitro 68, 69, and plays a key role in somatic cell reprogramming70–73. Furthermore, voluntary running is known to increase dividing Sox2+ HNPCs in the dentate gyrus leading to enhanced neurogenesis27. We find potentiation of Sox2 transcriptional activity, stabilization of Sox2 protein levels, and increased proliferation and neural differentiation of HNPCs following IGF-1 stimulation, suggesting that IGF-1/RIT1 regulation of Sox2 may represent a fundamental mechanism for controlling neurogenesis. IGF-1 has been shown to regulate Sox2 in a variety of systems, including human mesenchymal74 and colonic stem cells75. Thus, it is possible that IGF-1/RIT1 signaling might regulate Sox2 activity in diverse cell populations. We present data indicating that Akt is required for IGF1/RIT1-dependent Sox2 activity. This extends recent studies showing that Akt signaling contributes to the regulation of embryonic stem cell fate by controlling Sox2 stabilization and transcriptional activity by a phosphorylation at threonine 118 (T118)47. Consistent with a conserved regulatory mechanism, we find that IGF-1 stimulates Sox2 T118 phosphorylation in HNPCs, resulting in higher levels of Sox2 T118+ nuclei (Figs 6 and 8). Using RIT1 −/− HNPCs, RNAi methods, and pharmacological Akt inhibition, we demonstrate that RIT1 and Akt are required for IGF-mediated Sox2 transcriptional activation and neuronal differentiation (Figs 6–8). Following traumatic brain injury we have shown that conditional overexpression of IGF-1 leads to increased hippocampal neurogenesis64, 76, while post-TBI neurogenesis is delayed in RIT1 −/− mice36. Whether these changes rely upon changes in Sox2 function remains to be determined.

Interestingly, there is a growing literature suggesting that IGF-1 is critical for malignant transformation and metastasis of cancer cells77–79, and that Sox2 controls tumor initiation and cancer stem-cell function80, 81. We have found that conditional RIT1 overexpression in the dentate gyrus leads to the robust generation of neuroblasts39. Recently, we also identified RIT1 as a novel driver oncogene in a subset of human lung adenocarcinomas, and our data suggest PI3K/Akt inhibition as a potential therapeutic strategy in RIT1-mutated tumors38. Studies are underway to determine whether oncogenic RIT1-dependent tumorigenesis involves activation of Akt-Sox2 signaling.

In summary, we demonstrate a key role for the Ras-related GTPase, RIT1, in both IGF-1 and exercise-induced neurogenesis. IGF-1 dependent NPC proliferation and neural differentiation are inhibited by genetic deletion of the RIT1 gene. We also present data that provides new insight into the mechanisms underlying IGF-1-directed neurogenesis. Our findings reveal that a previously uncharacterized IGF-1/RIT1/Akt/Sox2 signaling cascade is import for regulating the proliferation and differentiation of neural precursors within the dentate gyrus. Collectively, these data provide new insight into mechanisms by which IGF-1 signaling and Sox2 function in neural stem-cell maintenance, embryogenesis and neuronal development.

Materials and Methods

Mouse running and BrdU labeling

RIT1 −/− mice have been previously described36. 12-week-old male RIT1 −/− mice and their WT littermates were divided into 2 groups and randomly placed in standard-sized rat cages (6 mice per cage) with (running group) or without (sedentary group) 2 (6 inch) running wheels82. Wheel running activity for each genotype was monitored 24 h/day and 7 days/week using ClockLab software (Actimetrics, Inc). For lineage labeling experiments, each mouse independent of housing was intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected with BrdU (50 mg/kg, in 0.9% Saline) once daily for the first 14 days of the experiment. Newborn immature neuron assessment was performed 2 days after the last BrdU injection (day 16). Neural maturation was quantified 1 month after the last BrdU injection (day 42). Following the either length of housing (16 or 42 days) mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (65 mg/kg, i.p.), transcardially perfused with heparinized saline followed by 10% buffered formalin, and decapitated. After 24 h of post-fixation in 10% buffered formalin, brains were removed from the skull, post-fixed for an additional 24 h, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose, and quickly frozen in isopentane. Serial coronal 40 µm sections were cut using a freezing sliding microtome (Dolby-Jamison). Every tenth section (400 µm intervals between sections) was selected as a set for further analysis. All experimental procedures were approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with guidelines established by the National Institutes of Health in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animals were housed at up to 5 mice per cage in the University of Kentucky Medical Center vivarium with a 14:10-hour light/dark photoperiod and were provided food and water ad libitum.

Subcutaneous IGF-1 infusion

Osmotic pumps (ALZET) were filled aseptically with 0.2-µm-filter sterilized saline or rIGF-1 (National Hormone and Peptide Program, Torrance, CA). 12-week-old RIT1−/− mice (n = 25) and their wild-type littermates were randomly divided into 2 groups (IGF-1 or control), anesthetized with isoflurane, and implanted subcutaneously dorsally16 for 7 days. The infusion rate of rIGF-1 was 500 ng/kg/day. At day 3 of infusion, mice were i.p. injected with BrdU (50 mg/kg) at 3 h intervals for 12 h.

Hippocampal neuronal stem cell (HNPC) cultures

Primary HNPC cultures were prepared as describe39. HNPCs were isolated from wild-type and RIT1 −/− mice as described83. Briefly, mice were euthanized, the brain dissected and placed in immersion buffer (HBSS (1x) with no Ca2+ or Mg2+ containing 1x antibiotic solution (Gibco)). Using a stereomicroscope, dentate gyrus (DG) from hippocampi were dissected and placed in ice-cold immersion buffer. DG (4–5/genotype) were washed with HBSS (1x) containing antibiotic, incubated at 37 °C for 30–45 min with frequent shaking in enzymatic digestion solution (0.25% trypsin in 1 × HBSS with activated papain), trypsin activity was quenched by repeated washing with DMEM (5–10 ml), and placed in 37 °C culture medium (containing DMEM/F12 (1:1), supplemented with 0.3% B27 without insulin, 20 ng/ml of EGF and 10 ng/ml bFGF, and antibiotics). HNPCs were released by trituration (3–4 times) into single cells using fire polished Pasteur pipettes. Approximately, 50 × 104 cells were plated in 12 well plates for suspension culture. Neurospheres were evident by day 3. For passage, neurospheres were pooled and mechanically dissociated into single cells and seeded into suspension in growth media in presence of EGF and bFGF (see above). For immunocytochemistry and immunoblotting, single cell suspensions derived from neurospheres were plated on poly D-Lysine coated coverslips or 6 well plates. HNPCs used in this study were Nestin+ (HNPC lineage) and >2 passages which promotes homogeneity in the cell population.

RNAi-mediated silencing in HNPCs

Lentiviral vector pZIP-mCMV containing the RIT1 pri-shRNA sequence (TGCTGTTG ACAGTGAGCGACACGAAGTTCGGGAGTTTAAATAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTATTTAAACTCCCGAACTTCGTGGTGCCTACTGCCTCGGA) was purchased from transOMIC Technologies (Huntsville, AL). Lentivirus was generated in 293LTV cells using the packaging vectors PsPAX2 and pMD2.G (Univ. Kentucky Genetic Technology Core). The efficiency of RNAi silencing in HNPCs was determined to be >70% using RT-PCR and confocal microscopy. Briefly, HNPCs after passage were allowed to assume normal morphology for 24–48 h before RNAi silencing. Growth medium was removed and stored as per our previously described method84, 1 µl of polybrene (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added in 1x HBSS for 10 min at 37 °C followed by repeated washes in 1x DPBS. Growth medium was premixed with 3 MOIs of either non-targeting control or RIT1-RNAi expressing lentivirus and placed on cells for 4–12 h at 37 °C. Cells were allowed to recover in fresh growth medium for 48–72 h to permit RIT1 silencing.

Cell transfection and neuronal differentiation

For HNPC transfection, fresh neurospheres were dissociated and approximately 105 cells were plated on poly-D-lysine coated coverslips/6 well plates. Cells were transfected 72 h after plating, using Jetprime transection reagent85 according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and allowed to recover cells 48 h before analysis. For IGF-1 stimulation of HNPCs, DMEM was supplemented with F12 (1:1) and FGF2 (10 ng/ml). For HNPC neuronal differentiation analysis, cells were placed in Neurobasal medium containing 1% FBS and RA (1 µM) for 4–6 days.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence or immunocytochemistry was performed as per our previously published method84. Mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (65 mg/kg, i.p.), transcardially perfused with 0.98% saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde, and decapitated84. Brains were removed from the skull, subject to post-fixation (2–3 days) at 4 °C in 4% paraformaldehyde, subject to increasing concentrations of sucrose (10–30%: O/N for each 10% step), and dissected under a stereomicroscope for hippocampus. Tissue blocks were embedded in OCT and snap frozen. All the blocks were stored at −80 °C for at least 2 days before coronal sections (15 µM or 40 µM) were cut using a cryostat, and mounted on superfrost plus slides (Fisher). Antigen retrieval was performed in citrate pH 6.2. For BrdU, antigen retrieval was performed with warm trypsin (0.25%) containing 2N HCl for 5 min at RT. The sections were extensively washed with PBS and incubated in blocking and permeablizing buffer [1% serum (matching the secondary antibody host), 1% Triton X-100 in 1 × PBS) for 10 min at RT followed by extensive washing (4 × PBS). After blocking, primary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer (0.01 M PBS pH 7.2 containing 1% serum, 0.05% Tween 20 and 0.1% Triton X-100) and applied to the sections O/N (4 °C). Dilutions were: rabbit anti-DCX (1:500); NeuN (1:3000), Rat anti-BrdU (Sigma, 1:800), Sox2 (Abcam, 1:300), Goat NeuroD1 (Santa Cruz, 1:200), Rabbit Nestin (Covance, 1:300), Rabbit Aktp473 (Cell Signaling Technology, 1:400) and Mouse Sox2pT118 (ECM Biosciences, 1:200). On the following day, sections were washed with 1 × PBS (x4) and secondary antibody (goat-anti-rabbit IgG FTIC: 1:1,000; either conjugated with Alexa 488, Alexa 568, Alexa 594 or PE) diluted in blocking buffer was applied for 2 h in the dark. Sections were then washed with 1 × PBS (x4), air dried, and cover slipped with SlowFade Gold containing DAPI. For immunocytochemistry, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at RT, permeablized, and blocked as described for tissue sections. Representative images were captured using a Nikon CKX31 A1 confocal microscope or Nikon C2 confocal microscope. All images were acquired using the NIS Elements software package (University of Kentucky License).

Image acquisition and analysis

Analysis was performed as previously described86. Briefly, isotype control slides were mounted to nullify nonspecific signals from either the Nikon C2 confocal or Nikon A2 confocal prior to mounting non-primary antibody treated slides and channels were adjusted to the individual secondary fluorophore. The numerical aperture and intensity values were optimized to minimize oversaturation and the channel data, pin hole details were recorded, and images recorded at 1024 pixels and 16x speed (Nikon C2 Confocal). Groups of images (3–6 images per specimen) were analyzed using ImageJ. For example, alternate color masks were applied to determine double positive (Nestin+/Ki67+) or single positive (Nestin+ only) for ≥200 nuclei from 5–6 random fields (for normalization), and data converted to relative fold changes. A similar approach was used to determine neuronal differentiation and the number Sox2+ and Sox T118+ HNPCs. For Akt activation following IGF-1 stimulation, the intensity profile of ≥50 cells from 15 random fields were normalized to DAPI using ImageJ. The mean was determined from 5–8 images per group. Quantification of immature (DCX+/BrdU+) and mature neuron analysis (NeuN+/BrdU+) was performed as previously described36. Briefly, to quantify the fluorescently labeled cells in the dentate gyrus, three sections (pre-epicenter, epicenter, post-epicenter, 400 μm intervals) were counted using a Nikon Eclipse E600 fluorescence microscope (40× objective). The focal plane was moved throughout the z-axis to capture each positive cell. To estimate the volume of the dentate gyrus, images were collected using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M fluorescence microscope (10× objective). The volume of the dentate gyrus was then calculated by multiplying the area of the dentate gyrus measured using ImageJ (NIH) by the thickness of each section (40 μm). Cell density was obtained by dividing total cell counts by the total volume of the dentate gyrus for the three sections that were counted.

Western blotting

Tissues/cells were homogenized using a Next Advance Bullet Blender at 4 °C in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris·HCl pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM Na3VO4, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1x protease inhibitor cocktail). Whole cell lysates were resolved on SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (12 h, 0.08 mA), and protein abundance and phosphorylation determined by immunoblotting with the appropriate phospho-specific antibodies and band intensity quantified using a ChemiDoc MP with Image Lab software (Bio-Rad)35, 36.

Luciferase gene reporter assay

Cignal Sox2 luciferase reporter was obtained from Qiagen (CCS-0038L). HNPCs were transfected with reporter and transduced with RNAi (Control RNAi or RIT1 RNAi), while RIT1 −/− HNPCs were co-transfected with the reporter and Myc-RIT1 (as indicated) or empty vector, and stimulated with/without IGF-1 (50 ng/ml, 24 h) in presence of FGF2 (10 ng/mL). Cells were washed with PBS and luciferase activity determined using a firefly luciferase assay kit (Promega) after passive lysis as described39.

Statistical analysis

The data is presented as Mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was carried out by either one way/two way ANNOVA combined with post hoc analysis using Tukey Kramer multiple comparisons or nonparametric unpaired one tailed t-test. Significance reported in this manuscript is p < 0.05. Any changes with p > 0.05 were considered to be insignificant.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 NS045103(DAA) and R01 NS072302 (KES) from the NINDS and the Kentucky Spinal Cord and Head Injury Research Trust (Grants 12-1A and 16-1)(DAA) and a Kentucky Lung Cancer Research Grant(DAA). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, or preparation of the manuscript. We wish to thank Dr. Michael Mendenhall for assistance in the generation of recombinant viruses. The authors acknowledge the use of facilities in the University of Kentucky Center for Molecular Medicine Genetic Technologies Core. This core is supported in part by NIH Grant Number P30GM110787. We also acknowledge Linda Simmerman in the Spinal Cord and Brain Injury Center and Dr. Carole Moncman in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry for help with confocal microscopy.

Author Contributions

S.M., W.C., K.E.S., and D.A.A. designed the studies; S.M., W.C. and S.W.C., performed research; S.M., W.C., S.W.C., K.E.S., and D.A.A. analyzed data; S.M. and D.A.A. wrote the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Sajad Mir and Weikang Cai contributed equally to this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Christian KM, Song H, Ming GL. Functions and dysfunctions of adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2014;37:243–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071013-014134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: significant answers and significant questions. Neuron. 2011;70:687–702. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonaguidi MA, et al. In vivo clonal analysis reveals self-renewing and multipotent adult neural stem cell characteristics. Cell. 2011;145:1142–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gage FH, Temple S. Neural stem cells: generating and regenerating the brain. Neuron. 2013;80:588–601. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spalding KL, et al. Dynamics of hippocampal neurogenesis in adult humans. Cell. 2013;153:1219–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faigle R, Song H. Signaling mechanisms regulating adult neural stem cells and neurogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:2435–2448. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mu Y, Lee SW, Gage FH. Signaling in adult neurogenesis. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:416–423. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu K, et al. The multiple roles for Sox2 in stem cell maintenance and tumorigenesis. Cellular signalling. 2013;25:1264–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarkar A, Hochedlinger K. The sox family of transcription factors: versatile regulators of stem and progenitor cell fate. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Archer TC, Jin J, Casey ES. Interaction of Sox1, Sox2, Sox3 and Oct4 during primary neurogenesis. Dev Biol. 2011;350:429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez AM, Torres-Aleman I. The many faces of insulin-like peptide signalling in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:225–239. doi: 10.1038/nrn3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Kusky J, Ye P. Neurodevelopmental effects of insulin-like growth factor signaling. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2012;33:230–251. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziegler AN, Levison SW, Wood TL. Insulin and IGF receptor signalling in neural-stem-cell homeostasis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:161–170. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu W, Ye P, O’Kusky JR, D’Ercole AJ. Type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor signaling is essential for the development of the hippocampal formation and dentate gyrus. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:2821–2832. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aberg MA, Aberg ND, Hedbacker H, Oscarsson J, Eriksson PS. Peripheral infusion of IGF-I selectively induces neurogenesis in the adult rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2896–2903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02896.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trejo JL, Carro E, Torres-Aleman I. Circulating insulin-like growth factor I mediates exercise-induced increases in the number of new neurons in the adult hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1628–1634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01628.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nieto-Estevez V, et al. Brain Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Directs the Transition from Stem Cells to Mature Neurons During Postnatal/Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Stem Cells. 2016;34:2194–2209. doi: 10.1002/stem.2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Kusky JR, Ye P, D’Ercole AJ. Insulin-like growth factor-I promotes neurogenesis and synaptogenesis in the hippocampal dentate gyrus during postnatal development. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8435–8442. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08435.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen P. The twentieth century struggle to decipher insulin signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:867–873. doi: 10.1038/nrm2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siddle K. Signalling by insulin and IGF receptors: supporting acts and new players. J Mol Endocrinol. 2011;47:R1–10. doi: 10.1530/JME-11-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bracko O, et al. Gene expression profiling of neural stem cells and their neuronal progeny reveals IGF2 as a regulator of adult hippocampal neurogenesis. J Neurosci. 2012;32:3376–3387. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4248-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peltier J, O’Neill A, Schaffer DV. PI3K/Akt and CREB regulate adult neural hippocampal progenitor proliferation and differentiation. Dev Neurobiol. 2007;67:1348–1361. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuan H, et al. The regulatory mechanism of neurogenesis by IGF-1 in adult mice. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;51:512–522. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8717-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X, et al. IGF-1 promotes Brn-4 expression and neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells via the PI3K/Akt pathway. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oishi K, et al. Selective induction of neocortical GABAergic neurons by the PDK1-Akt pathway through activation of Mash1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13064–13069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808400106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voss MW, Vivar C, Kramer AF, van Praag H. Bridging animal and human models of exercise-induced brain plasticity. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17:525–544. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suh H, et al. In vivo fate analysis reveals the multipotent and self-renewal capacities of Sox2+ neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:515–528. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruel-Jungerman E, et al. Inhibition of PI3K-Akt signaling blocks exercise-mediated enhancement of adult neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity in the dentate gyrus. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ransome MI, Hannan AJ. Impaired basal and running-induced hippocampal neurogenesis coincides with reduced Akt signaling in adult R6/1 HD mice. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2013;54:93–107. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cotman CW, Berchtold NC, Christie LA. Exercise builds brain health: key roles of growth factor cascades and inflammation. Trends in neurosciences. 2007;30:464–472. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee CH, Della NG, Chew CE, Zack DJ. Rin, a neuron-specific and calmodulin-binding small G-protein, and Rit define a novel subfamily of ras proteins. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6784–6794. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-06784.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lein PJ, et al. The novel GTPase Rit differentially regulates axonal and dendritic growth. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4725–4736. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5633-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wes PD, Yu M, Montell C. RIC, a calmodulin-binding Ras-like GTPase. The EMBO journal. 1996;15:5839–5848. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi GX, Cai W, Andres DA. Rit subfamily small GTPases: regulators in neuronal differentiation and survival. Cell Signal. 2013;25:2060–2068. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai W, et al. An evolutionarily conserved Rit GTPase-p38 MAPK signaling pathway mediates oxidative stress resistance. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:3231–3241. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-05-0400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cai W, et al. Rit GTPase signaling promotes immature hippocampal neuronal survival. J Neurosci. 2012;32:9887–9897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0375-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cai W, Rudolph JL, Sengoku T, Andres DA. Rit GTPase regulates a p38 MAPK-dependent neuronal survival pathway. Neurosci Lett. 2012;531:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berger AH, et al. Oncogenic RIT1 mutations in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2014;33:4418–4423. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mir, S., Cai, W. & Andres, D. A. RIT1 GTPase Regulates Sox2 Transcriptional Activity and Hippocampal Neurogenesis. J Biol Chem, doi:10.1074/jbc.M116.749770 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Voss MW, Vivar C, Kramer AF, van Praag H. Bridging animal and human models of exercise-induced brain plasticity. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17:525–544. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalluri HS, Vemuganti R, Dempsey RJ. Mechanism of insulin-like growth factor I-mediated proliferation of adult neural progenitor cells: role of Akt. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:1041–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hodge RD, Hevner RF. Expression and actions of transcription factors in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Dev Neurobiol. 2011;71:680–689. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andersen J, et al. A transcriptional mechanism integrating inputs from extracellular signals to activate hippocampal stem cells. Neuron. 2014;83:1085–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao Z, et al. Neurod1 is essential for the survival and maturation of adult-born neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1090–1092. doi: 10.1038/nn.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuwabara T, et al. Wnt-mediated activation of NeuroD1 and retro-elements during adult neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1097–1105. doi: 10.1038/nn.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amador-Arjona A, et al. SOX2 primes the epigenetic landscape in neural precursors enabling proper gene activation during hippocampal neurogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E1936–1945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421480112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fang L, et al. A methylation-phosphorylation switch determines Sox2 stability and function in ESC maintenance or differentiation. Mol Cell. 2014;55:537–551. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang L, et al. Akt/protein kinase B signaling inhibitor-2, a selective small molecule inhibitor of Akt signaling with antitumor activity in cancer cells overexpressing Akt. Cancer research. 2004;64:4394–4399. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beck KD, Powell-Braxton L, Widmer HR, Valverde J, Hefti F. Igf1 gene disruption results in reduced brain size, CNS hypomyelination, and loss of hippocampal granule and striatal parvalbumin-containing neurons. Neuron. 1995;14:717–730. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90216-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chaker Z, Aid S, Berry H, Holzenberger M. Suppression of IGF-I signals in neural stem cells enhances neurogenesis and olfactory function during aging. Aging Cell. 2015;14:847–856. doi: 10.1111/acel.12365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Russo VC, Gluckman PD, Feldman EL, Werther GA. The insulin-like growth factor system and its pleiotropic functions in brain. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:916–943. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trejo JL, Carro E, Torres-Aleman I. Circulating insulin-like growth factor I mediates exercise-induced increases in the number of new neurons in the adult hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1628–1634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01628.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arsenijevic Y, Weiss S, Schneider B, Aebischer P. Insulin-like growth factor-I is necessary for neural stem cell proliferation and demonstrates distinct actions of epidermal growth factor and fibroblast growth factor-2. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7194–7202. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07194.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brooker GJ, et al. Endogenous IGF-1 regulates the neuronal differentiation of adult stem cells. J Neurosci Res. 2000;59:332–341. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(20000201)59:3<332::AID-JNR6>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Drago J, Murphy M, Carroll SM, Harvey RP, Bartlett PF. Fibroblast growth factor-mediated proliferation of central nervous system precursors depends on endogenous production of insulin-like growth factor I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2199–2203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mairet-Coello G, Tury A, DiCicco-Bloom E. Insulin-like growth factor-1 promotes G(1)/S cell cycle progression through bidirectional regulation of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway in developing rat cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2009;29:775–788. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1700-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katsimpardi L, et al. Vascular and neurogenic rejuvenation of the aging mouse brain by young systemic factors. Science. 2014;344:630–634. doi: 10.1126/science.1251141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moon HY, et al. Running-Induced Systemic Cathepsin B Secretion Is Associated with Memory Function. Cell Metab. 2016;24:332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Darcy MJ, Trouche S, Jin SX, Feig LA. Ras-GRF2 mediates long-term potentiation, survival, and response to an enriched environment of newborn neurons in the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2014;24:1317–1329. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Amiri A, et al. Pten deletion in adult hippocampal neural stem/progenitor cells causes cellular abnormalities and alters neurogenesis. J Neurosci. 2012;32:5880–5890. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5462-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Groszer M, et al. Negative regulation of neural stem/progenitor cell proliferation by the Pten tumor suppressor gene in vivo. Science. 2001;294:2186–2189. doi: 10.1126/science.1065518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zheng HQ, et al. Physical exercise promotes recovery of neurological function after ischemic stroke in rats. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:10974–10988. doi: 10.3390/ijms150610974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ye P, D’Ercole AJ. Insulin-like growth factor actions during development of neural stem cells and progenitors in the central nervous system. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:1–6. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Madathil SK, et al. Astrocyte-Specific Overexpression of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Protects Hippocampal Neurons and Reduces Behavioral Deficits following Traumatic Brain Injury in Mice. PloS one. 2013;8:e67204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rubovitch V, Edut S, Sarfstein R, Werner H, Pick CG. The intricate involvement of the Insulin-like growth factor receptor signaling in mild traumatic brain injury in mice. Neurobiology of disease. 2010;38:299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fletcher L, et al. Intranasal delivery of erythropoietin plus insulin-like growth factor-I for acute neuroprotection in stroke. Laboratory investigation. J Neurosurg. 2009;111:164–170. doi: 10.3171/2009.2.JNS081199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhu W, et al. Insulin growth factor-1 gene transfer enhances neurovascular remodeling and improves long-term stroke outcome in mice. Stroke. 2008;39:1254–1261. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.500801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brazel CY, et al. Sox2 expression defines a heterogeneous population of neurosphere-forming cells in the adult murine brain. Aging Cell. 2005;4:197–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2005.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Favaro R, et al. Hippocampal development and neural stem cell maintenance require Sox2-dependent regulation of Shh. Nature neuroscience. 2009;12:1248–1256. doi: 10.1038/nn.2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim J, et al. Direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts to neural progenitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:7838–7843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103113108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ring KL, et al. Direct reprogramming of mouse and human fibroblasts into multipotent neural stem cells with a single factor. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thier M, et al. Direct conversion of fibroblasts into stably expandable neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ferretti C, et al. Role of IGF1 and IGF1/VEGF on human mesenchymal stromal cells in bone healing: two sources and two fates. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20:2473–2482. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.D’Addio F, et al. Circulating IGF-I and IGFBP3 Levels Control Human Colonic Stem Cell Function and Are Disrupted in Diabetic Enteropathy. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:486–498. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carlson SW, et al. Conditional overexpression of insulin-like growth factor-1 enhances hippocampal neurogenesis and restores immature neuron dendritic processes after traumatic brain injury. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2014;73:734–746. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baxter RC. IGF binding proteins in cancer: mechanistic and clinical insights. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:329–341. doi: 10.1038/nrc3720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pollak M. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor signalling in neoplasia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:915–928. doi: 10.1038/nrc2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yu H, Rohan T. Role of the insulin-like growth factor family in cancer development and progression. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92:1472–1489. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.18.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Boumahdi S, et al. SOX2 controls tumour initiation and cancer stem-cell functions in squamous-cell carcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:246–250. doi: 10.1038/nature13305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Siegle JM, et al. SOX2 is a cancer-specific regulator of tumour initiating potential in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4511. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH. Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:266–270. doi: 10.1038/6368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Guo W, Patzlaff NE, Jobe EM, Zhao X. Isolation of multipotent neural stem or progenitor cells from both the dentate gyrus and subventricular zone of a single adult mouse. Nature protocols. 2012;7:2005–2012. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mir S, Sen T, Sen N. Cytokine-induced GAPDH sulfhydration affects PSD95 degradation and memory. Mol Cell. 2014;56:786–795. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Park DH, et al. Activation of neuronal gene expression by the JMJD3 demethylase is required for postnatal and adult brain neurogenesis. Cell reports. 2014;8:1290–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Merkle FT, et al. Generation of neuropeptidergic hypothalamic neurons from human pluripotent stem cells. Development. 2015;142:633–643. doi: 10.1242/dev.117978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]