Abstract

HIV is common among individuals with substance use disorders, but relatively few studies have examined the impact of HIV status on response to substance abuse treatment. This secondary analysis compared patients seeking treatment for cocaine use with and without HIV in terms of substance use treatment outcomes. Primary treatment outcomes included treatment retention, longest duration of abstinence, and percent of negative samples; both substance use outcomes reflect abstinence from cocaine, alcohol and opioids concurrently. Participants (N=432) were enrolled in randomized clinical trials comparing contingency management (CM) to standard care, and 32 (7%) reported being positive for HIV. Overall, CM improved both treatment retention (average of 8.2 weeks compared to 6.0 weeks in the standard care condition) and longest duration of abstinence (average of 5.8 weeks compared to 2.8 weeks in the standard care condition), but did not have a significant effect on percent of negative samples. HIV status was not associated with treatment outcomes as a main effect, nor did it have an interaction effect with treatment condition. These results suggest a benefit of CM in substance abuse treatment irrespective of HIV status.

Keywords: substance abuse treatment, contingency management, HIV

1. Introduction

Among treatment-seeking illicit drug users, HIV prevalence rates are higher than national norms and can approach 14% (Des Jarlais et al., 2014; Des Jarlais et al., 2007). Substance use is associated with HIV contraction (DeBeck et al., 2009) and poorer medical outcomes (Lucas et al., 2006), including reduced antiretroviral treatment initiation (Doshi et al., 2012) and poor adherence to pharmacotherapies (Arnsten et al., 2002; Gonzalez, Mimiaga, Israel, Bedoya, & Safren, 2013; Ingersoll, 2004). Stimulants, in particular, can accelerate HIV progression, decreasing CD4 cell counts (Baum et al., 2009; Duncan et al., 2007; Pandare et al., 2014) and increasing HIV viral load (Nacher et al., 2009). Therefore, reducing substance use, especially among stimulant users, could be beneficial in improving HIV outcomes.

Patients with concurrent stimulant use disorders and HIV may have poorer substance use treatment outcomes than their counterparts without HIV due to more significant psychopathology. Depression, for example, is associated with both cocaine use disorder (Conway, Compton, Stinson, & Grant, 2006) and HIV (Do et al., 2014). Further, substance use and HIV together have an additive effect on depression (Lipsitz et al., 1994), and depressive symptoms are associated with lower abstinence rates (Dodge, Sindelar & Sinha, 2005). Individuals with HIV also report higher rates of anxiety disorders relative to those without HIV (Bing et al., 2001; Shacham, Onen, Donovan, Rosenburg, & Overton, 2014), and these disorders are linked to lower retention (Carroll, Power, Bryant, & Rounsaville, 1993) and reduced abstinence (Herbeck, Hser, Lu, Stark, & Paredes, 2006) in substance use treatment as well. Therefore, patients seeking treatment for a stimulant use disorder such as cocaine who also have HIV may have poorer substance abuse treatment outcomes than their counterparts without HIV, but this question has not been tested empirically. If they do have worse outcomes, this finding may justify providing enhanced efficacious interventions for substance abuse treatment patients with HIV.

Contingency management (CM) has the largest effect size of all psychosocial interventions for the treatment substance use disorders (Dutra et al., 2008) and is effective across demographic and comorbid conditions (García-Fernández, Secades-Villa, García-Rodríguez, Peña-Suárez, & Sánchez-Hervás, 2013; Messina, Farabee, & Rawson, 2003; Secades-Villa et al., 2013). CM provides tangible incentives as reinforcement for specified target behaviors, such as drug abstinence, and it is known for improving treatment retention (Miguel et al., 2016). Multiple studies have demonstrated the efficacy of CM for reducing cocaine use (see meta-analyses: Lussier, Heil, Mongeon, Badger, & Higgins, 2006; Prendergast, Podus, Finney, Greenwell, & Roll, 2006), and CM increases abstinence relative to a 12-step treatment approach in HIV positive substance users receiving care at an HIV clinic (Petry, Weinstock, Alessi, Lewis, & Dieckhaus, 2010). However, no known studies have evaluated whether patients seeking outpatient treatment for cocaine use who have HIV respond similarly to CM compared to their counterparts without HIV. This information is important because if patients with cocaine use disorder and HIV respond well to CM, then its use may be particularly justified in this population.

The primary aim of this study employing secondary analyses procedures was to investigate the impact of HIV status on substance use outcomes in response to standard care and CM treatment in patients with a cocaine use disorder in community based clinics. The primary trials (Petry et al., 2006; Petry, Alessi, Marx, Austin, & Tardif, 2005; Petry et al., 2004; Petry, Weinstock, & Alessi, 2011) all found CM conditions to have better treatment outcomes than standard care conditions, and the analyses described herein explored the main and interactive effects of HIV status and treatment condition on substance use outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants (n = 432) were cocaine use disorder patients who had HIV status information available and were enrolled in four randomized trials of CM for substance use treatment (Petry et al., 2006; Petry, Alessi, Marx, Austin, & Tardif, 2005; Petry et al., 2004; Petry, Weinstock, & Alessi, 2011). The four trials had similar inclusion criteria: age 18 years or older, English speaking, cocaine use disorder and beginning intensive outpatient treatment at a community-based substance abuse treatment clinic, and ability to understand study procedures. Exclusion criteria were being in recovery for gambling disorder (see Petry & Alessi, 2010; Petry et al., 2006) and significant uncontrolled psychiatric conditions (e.g., active suicidal ideation, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia). In regards to the latter, these outpatient clinics did not treat patients with severe, persistent and chronic diagnoses such as schizophrenia who are most often seen in specialized mental health clinics, and hence, such patients were rarely screened for participation in these studies. However, many patients at these clinics did have other mental health conditions (depression, anxiety, etc.) that did not prevent enrollment in the studies. Written informed consent was collected from all patients. The University Institutional Review Board approved study procedures.

2.2 Procedures

Following informed consent, demographic information including race, ethnicity, gender, age and education were collected along with drug use and treatment histories. Research assistants then administered the Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al., 1985) and checklists based on sections of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996). The ASI contains sections designed to evaluate seven domains of psychosocial functioning: medical, employment, alcohol use, drug use, legal, family/social, and psychiatric problems. Scores ranging from 0 to 1 are calculated for each domain, with higher scores indicating greater severity of symptoms. The ASI is reliable and valid in assessing severity of psychosocial and medical problems (Mäkelä, 2004; McLellan, Cacciola, Alterman, Rikoon, & Carise, 2006). Under the medical section of the ASI, participants in these four studies were asked to report their HIV status; response options included: “negative,” “positive,” “never been tested/do not know” status. Participants reporting “never been tested/do not know” status and those missing this data point were not included in the analysis (n = 141 of 573 total randomized). The primary reason for the missing data relates to an oversight in implementing study questionnaires. Specifically, the question regarding HIV status was added late to the assessment batteries at some sites, resulting in the initial subjects not being asked this item. We assessed whether data were missing completely at random using Little’s test, and results were not significant (p = .39), suggesting no systematic influences on missingness. Statistical analyses were performed on the 432 participants with HIV status information available.

2.3 Treatments

In each of the primary studies (Petry et al., 2006; Petry et al., 2005; Petry et al., 2004; Petry et al., 2011), a computerized procedure randomly assigned patients to treatment conditions. All participants received standard care that included a minimum of weekly group therapy sessions. Breath and urine samples were collected up to 24 times during the first 12 weeks of treatment. Breath samples were tested for alcohol using Alcosensor-IV Alcometers (Intoximeters, St Louis, MO, USA) and urine samples for opioids and cocaine using Ontrak TesTstiks (Roche, Somersville, NJ, USA). This standard care condition was compared to the same standard care plus one or more CM conditions in each of the four studies.

All CM conditions involved reinforcement for submission of negative samples or other clinically relevant, objectively determined behaviors such as attendance at counseling sessions, or completion of personalized goal-related activities as part of a treatment plan (e.g., complete a job application, schedule a doctor’s appointment). Reinforcement for abstinence was contingent upon samples testing negative for cocaine, opioids and alcohol concurrently (although most positive samples were for cocaine with <5% testing positive for other substances). Some benefits of CM relative to standard care were found for all studies. In the Petry et al. (2006) study outcomes of the reinforcement of two different behaviors were compared: submission of negative samples and completion of goal-related activities. Another study (Petry et al., 2005) compared prize reinforcement to voucher reinforcement for submission of negative samples. In the Petry et al. (2004) study, conditions awarding different magnitudes of prizes for submission of negative samples were compared. The Petry et al. (2011) study implemented CM in a group context and reinforced both attendance at group and submission of negative samples. Comparable treatments (e.g., intensity, duration) and identical assessment instruments across all studies allowed for cross-study analyses.

2.4 Data Analysis

Participants were dichotomized based on self-reported HIV status. The sample consisted of 32 (7%) known HIV positive and 400 (93%) participants who reported having received a negative test for HIV. Demographic and baseline characteristics were compared between groups using chi-square tests, independent t-tests, and Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA).

Multivariate general linear models (GLM) assessed relationships between HIV status, treatment condition (CM or SC) and their interaction on substance use treatment outcomes. Variables that differed between the groups based on HIV status were entered into the analysis as covariates unless otherwise noted. Two additional variables (primary study assignment: Petry et al., 2004, 2005, 2006, or 2011; and baseline sample results of positive or negative for any of the tested substances) were included due to their relationship with outcome measures (e.g., Kidorf, Stitzer, & Brooner, 1995; Petry, Barry, Alessi, Rounsaville, & Carroll, 2012; Preston et al., 1998). Primary treatment outcomes included: treatment retention, percent of negative samples submitted, and longest duration of abstinence (LDA). Retention was defined as weeks (0–12) retained in therapy at the outpatient treatment clinics. Percentage of samples testing negative for alcohol, cocaine, and opioids concurrently was calculated with the number of samples submitted in the denominator; this variable was unaffected by retention or missing samples and is the most conservative method for testing intervention effects in CM studies (see Petry et al., 2012). The LDA was calculated based upon the total number of consecutive weeks (0–12) in which participants submitted samples testing negative for all three substances. A period of abstinence was reset for unexcused absences on a testing day, failure to provide a sample, or if a sample tested positive for cocaine, opiates or alcohol. These two methods of presenting objective indices of substance use outcomes provide the range of outcomes both considering missed samples as positive (LDA) and not (percent negative with only submitted samples in the denominator making no assumptions about whether missing samples are positive or negative).

A percentage variable can also be derived by including missing samples in the denominator. Although this percentage correlates very highly with LDA (r = 0.89, p < .001), we included it, rather than the percentage variable considering only submitted samples, in a secondary GLM for the sake of completeness.

A formal power analyses was not conducted due to the retrospective and secondary nature of these analyses. However, sensitivity analyses revealed the ability to detect medium-to-large effect sizes by HIV status with the observed group sizes. Analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows (v 21), and 2-tailed alphas of p < 0.05 were interpreted as significant.

3. Results

Significant demographic and baseline differences were found between HIV positive and HIV negative participants (Table 1). On average, HIV positive participants were older by about 5 years and reported lower annual earned income by about $8,400. HIV positive participants reported significantly lower rates of full- and part-time employment than HIV negative participants. Even after controlling for differences in age, HIV positive participants reported about 4 more lifetime years of heroin use compared to those without HIV. Average ASI medical and employment scores were higher, indicating greater severity, for HIV positive participants.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics

| Variable | HIV Negative | HIV Positive | Statistical test (df), p |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 400 | 32 | |

| Study, n (%) | X2(3) = 3.67, 0.30 | ||

| Petry et al. (2004) | 97 (24.3) | 5 (15.6) | |

| Petry et al. (2005) | 103 (25.8) | 13 (40.6) | |

| Petry et al. (2006) | 64 (16.0) | 4 (12.5) | |

| Petry et al. (2011) | 136 (34.0) | 10 (31.3) | |

| Treatment group, n (%) | X2(1) = 0.21, 0.65 | ||

| Contingency management | 259 (64.8) | 22 (68.8) | |

| Standard care | 141 (35.3) | 10 (31.3) | |

| Race, n (%) | X2(2) = 0.08, 0.96 | ||

| African American | 232 (58.0) | 18 (56.3) | |

| Caucasian | 124 (31.0) | 10 (31.3) | |

| Other | 44 (11.0) | 4 (12.5) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | X2(1) = 0.001, 0.98 | ||

| Hispanic | 37 (9.3) | 3 (9.4) | |

| Other | 363 (90.75) | 29 (90.6) | |

| Male gender, n (%) | 197 (49.3) | 16 (50.0) | X2(1) = 0.01, 0.94 |

| Age* | 36.0 (8.6) | 41.1 (7.6) | t (430) = −3.23, 0.001 |

| Years of education | 11.9 (1.8) | 11.5 (2.0) | t (429) = 1.10, 0.27 |

| Employment status* | X2(2) = 9.96, 0.007 | ||

| Full Time | 176 (44.0) | 9 (28.1) | |

| Part time | 96 (24.0) | 4 (12.5) | |

| Other | 128 (32.0) | 19 (59.4) | |

| Earned annual income* | $10,327 (16,027) | $1,905 (4,137) | t (430) = 2.96, 0.003 |

| Baseline sample positive for cocaine, opioids or alcohol, n (%) | 78 (19.5) | 8 (25.0) | X2(1) = 0.55, 0.46 |

| Lifetime years of use ofa: | |||

| Cocaine | 10.5 (7.3) | 14.3 (7.5) | F (1) = 1.98, 0.16 |

| Alcohol | 14.0 (10.5) | 17.1 (10.4) | F (1) = 0.001, 0.97 |

| Heroin* | 1.8 (4.9) | 6.2 (10.3) | F (1) = 15.17, <0.001 |

| Marijuana | 8.3 (8.4) | 11.3 (10.6) | F (1) = 2.00, 0.16 |

| Past year substance use disorder, n (%) | |||

| Alcohol | 252 (63) | 21 (65.6) | X2(1) = 0.09, 0.77 |

| Opiates | 86 (30.1) | 8 (29.6) | X2(1) = 0.002, 0.96 |

| Addiction Severity Indexb | |||

| Medical* | 0.23 (0.34) | 0.41 (0.35) | t (430) = −2.85, 0.01 |

| Employment* | 0.72 (0.28) | 0.87 (0.24) | t (430) = −2.99, 0.003 |

| Alcohol | 0.21 (0.22) | 0.15 (0.20) | t (430) = 1.54, 0.12 |

| Drug use | 0.17 (0.09) | 0.15 (0.10) | t (429) = 1.30, 0.19 |

| Legal | 0.14 (0.21) | 0.07 (0.19) | t (429) = 1.87, 0.06 |

| Family/social | 0.19 (0.22) | 0.20 (0.23) | t (428) = −0.36, 0.72 |

| Psychological | 0.28 (0.24) | 0.25 (0.19) | t (427) = 0.63, 0.53 |

Note. Values are means and standard deviations unless otherwise indicated;

Analyses controlled for current age of participants.

Higher scores on the ASI indicate greater severity of symptoms.

Significant between group differences, p < .05

Study, baseline sample results, age, and ASI employment scores were entered in the GLM as covariates. Although differences also existed between groups on income and employment status, these variables were not included in the models due to overlap with ASI employment scores. Likewise, ASI medical scores were not included in the analysis due to overlap with the dichotomizing variable (HIV status). Lifetime years of heroin use was not entered into the analysis due to its high correlation with age, and lack of association with outcomes.

Treatment condition, study, baseline sample result, and ASI employment scores were related to outcomes. Treatment condition impacted retention, F(1, 423) = 7.35, p = .007 and LDA, F(1, 423) = 14.84, p < .001, but not percent negative samples, F(1, 423) = 1.13, p = .29. Overall, participants randomized to CM remained in treatment longer than those receiving standard care, with means and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of 8.2 (95% CI = 7.3 – 9.1) weeks versus 6.0 (95% CI = 4.7 – 7.3) weeks, respectively. Participants in CM conditions also achieved greater LDA, 5.8 (95% CI = 4.9 – 6.6) weeks, compared to participants randomized to standard care, 2.8 (95% CI = 1.6 – 4.1) weeks.

Study was related to weeks retained in treatment, F(1, 423) = 3.93, p = .05, but not percent negative samples or LDA, ps > .07. Baseline sample result was negatively associated with percent negative samples submitted during treatment, F(1, 423) = 277.12, p < .001 and LDA, F(1, 423) = 60.00, p < .001; its association with retention did not reach significance, F(1, 423) = 3.53, p = .06. ASI employment scores were negatively associated with percent negative samples submitted, F(1, 423) = 4.51, p = .03, but not LDA or retention, ps > .09.

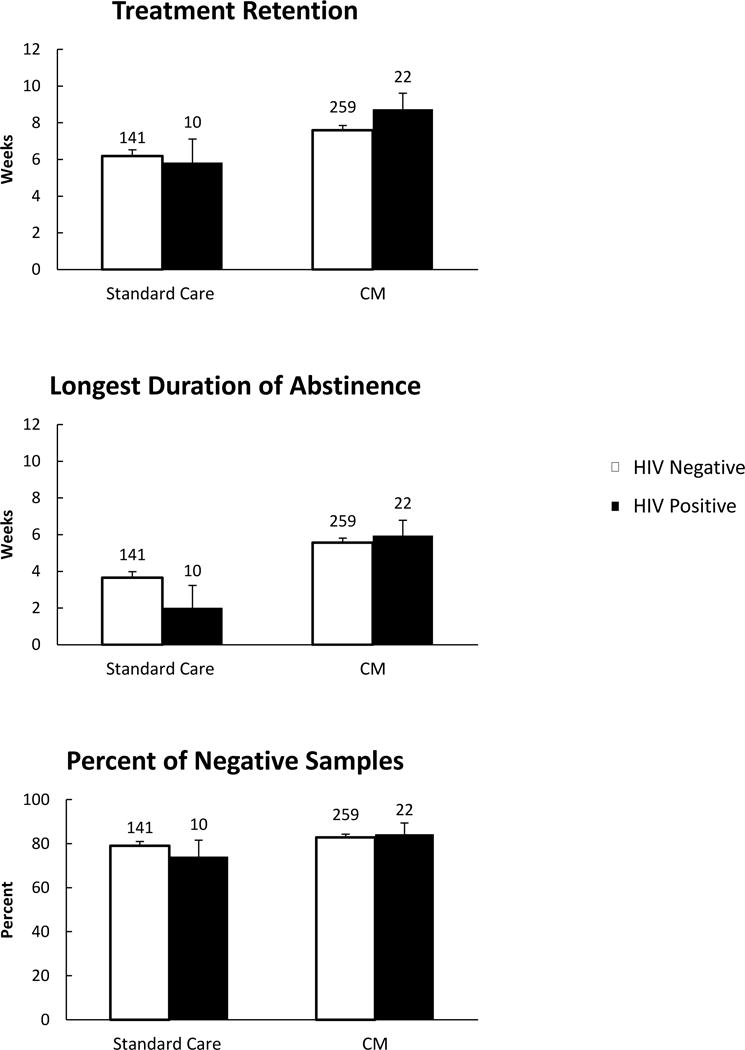

After controlling for these variables, the multivariate analysis did not reveal a main effect for HIV status (ps > .41) on substance abuse treatment outcomes (retention: 7.3 [95% CI = 5.8 – 8.8] weeks for HIV positive, 6.9 [95% CI = 6.5 – 7.3] weeks for HIV negative; percent of negative samples: 77.2% [95% CI = 68.3 – 86.1] for HIV positive, 80.9% [95% CI = 78.5, 83.3] for HIV negative; LDA: 4.0 [95% CI = 2.5 – 5.4] weeks for HIV positive, 4.6 [95% CI = 4.2 – 5.0] weeks for HIV negative). The interaction between HIV status and treatment condition on substance use treatment outcomes was also not significant (ps > .18). Figure 1 shows the weighted means (SE) of weeks retained in treatment, percent of negative samples, and LDA based on HIV status and treatment condition.

Figure 1.

Weighted means (SE) of the primary outcomes based on HIV status and treatment condition. Group n’s are provided above bars.

A secondary GLM analysis included percentage of samples testing negative for alcohol, cocaine, and opioids concurrently using number of scheduled samples in the denominator. As in the main model outlined above, the main effect of HIV status on percentage of samples negative was not significant, F(1, 423) = .17, p = .682, but the main effect of treatment condition was, F(1, 423) = 11.24, p < .001, and the interaction between HIV status and treatment condition approached significance, F(1, 423) = 2.90, p = .089. These results, however, should be interpreted with caution due to the high correlation between LDA and percentage of negative samples with missing samples in the denominator.

4. Discussion

Substance abuse treatment patients with HIV evidenced demographic differences and greater impairments across a range of domains at baseline compared to those who were HIV negative. Participants who were HIV positive were older, had more severe medical problems, reported lower incomes and were less likely to be employed full- or part-time compared to HIV negative participants, consistent with prior studies (Turrina et al., 2001; Rabkin et al., 1997). However, in contrast to prior findings (Lipsitz et al., 1994; Turrina et al., 2001), we did not find elevated levels of psychological symptoms among HIV positive compared to HIV negative substance users. This study used the ASI to assess psychopathology globally, while the prior studies used DSM-III-R criteria, a more sensitive index of specific mental disorders.

Contingency management treatment was efficacious in improving outcomes, regardless of HIV status. Both HIV positive and negative participants randomized to CM remained in treatment longer and achieved longer durations of abstinence than those randomized to standard care. These results are important because improved substance abuse treatment outcomes may ultimately translate to better health outcomes especially among HIV positive substance users, who are known to have poor initiation (Doshi et al., 2012) and adherence to antiretrovirals (Gonzalez et al., 2013). In addition, provision of CM to HIV positive substance abuse treatment patients may translate to societal benefits as these patients are less likely to transmit the virus both via sexual and intravenous routes when their substance use is treated (Metzger, Woody, & O’Brien, 2010).

Findings from the current study should be considered within the context of some limitations. First, this study did not assess access to HIV medical care or medical outcomes among participants. Larger and longer term studies with a more thorough assessment of these variables would be needed to estimate the medical and societal benefits of CM in HIV positive, and negative, substance abuse treatment patients. Second and related, the number of participants in the HIV positive group was small, and dividing them by type of treatment further reduced group size; this retrospective analysis only had power to detect medium-to-large differences. Third, HIV status was based upon self-report. Studies examining the validity of self-reported HIV status have found good correspondence between medically-confirmed HIV negative status and self-reported status among substance using populations (McCusker, Stoddard, & McCarthy, 1992; Strauss, Rindskopf, Deren, & Falkin, 2001). However, some persons deny their HIV status, and some were possibly positive without knowing it (Fisher, Reynolds, Jaffe, & Johnson, 2007; Strauss et al., 2001). The relatively low rate of HIV in this sample (7%) compared to other samples of substance abuse treatment patients (Des Jarlais et al., 2014; Des Jarlais et al., 2007) may represent a response bias or a relatively lower rate of HIV transmission among substance abuse treatment patients in this region of the country; it may also reflect a single negative HIV test, done years earlier. Future studies should confirm HIV status by biological indices. In addition, the date of HIV diagnosis was not obtained for all participants, and the influence of HIV diagnosis on substance use outcomes may change over time (Barroso & Sandelowski, 2004). Finally, this study focused on patients with cocaine use disorders, and cocaine is the stimulant most commonly used in the geographical region in which this study was conducted. Results may or may not differ for primary users of methamphetamine.

Despite limitations, this study has a number of strengths. A large overall sample size, minimal inclusion and exclusion criteria, and variation among CM protocols across studies allow for generalization of findings. In addition, participants were recruited from multiple community-based clinics, further enhancing generalization. Substance abuse treatment patients benefited from CM, regardless of their HIV status. These results add to the strong evidence base and general applicability of CM across a broad range of patient characteristics. Reinforcing abstinence in HIV positive patients may ultimately improve their medical outcomes and reduce the spread of HIV, and future larger scale studies should address these issues directly.

Highlights.

This study evaluates the impact of HIV status on treatment outcomes in response to standard care and CM.

CM improved treatment retention and longest duration of abstinence.

HIV status was not associated with substance abuse treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This study, and preparation of this report, were supported in part by NIH grants: P50-DA09241, P60-AA03510, R01-AA021446, R01-HD075630, and R01-AA023502.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Grant RW, Gourevitch MN, Farzadegan H, Howard AA, Schoenbaum EE. Impact of active drug use on antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV‐infected drug users. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002;17(5):377–381. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barroso J, Sandelowski M. Substance abuse in HIV-positive women. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2004;15(5):48–59. doi: 10.1177/1055329004269086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum MK, Rafie C, Lai S, Sales S, Page B, Campa A. Crack-cocaine use accelerates HIV disease progression in a cohort of HIV-positive drug users. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;50(1):93–99. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181900129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, London AS, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus–infected adults in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(8):721–728. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Power ME, Bryant K, Rounsaville BJ. One-year follow-up status of treatment-seeking cocaine abusers. Psychopathology and dependence severity as predictors of outcome. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1993;181(2):71–79. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199302000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67(2):247–258. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBeck K, Kerr T, Li K, Fischer B, Buxton J, Montaner J, Wood E. Smoking of crack cocaine as a risk factor for HIV infection among people who use injection drugs. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2009;181(9):585–589. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.082054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Arasteh K, McKnight C, Perlman DC, Feelemyer J, Hagan H, Cooper HLF. HSV-2 co-infection as a driver of HIV transmission among heterosexual non-injecting drug users in New York City. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e87993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Arasteh K, Perlis T, Hagan H, Abdul-Quader A, Heckathorn DD, Friedman SR. Convergence of HIV seroprevalence among injecting and non-injecting drug users in New York City. AIDS. 2007;21(2):231–235. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280114a15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do AN, Rosenberg ES, Sullivan PS, Beer L, Strine TW, Schulden JD, Skarbinski J. Excess burden of depression among HIV-infected persons receiving medical care in the United States: data from the medical monitoring project and the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge R, Sindelar J, Sinha R. The role of depression symptoms in predicting drug abstinence in outpatient substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28(2):189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doshi RK, Vogenthaler NS, Lewis S, Rodriguez A, Metsch L, Rio CD. Correlates of antiretroviral utilization among hospitalized HIV-infected crack cocaine users. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2012;28(9):1007–1014. doi: 10.1089/aid.2011.0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan R, Shapshak P, Page JB, Chiappelli F, McCoy CB, Messiah SE. Crack cocaine: effect modifier of RNA viral load and CD4 count in HIV infected African American women. Front Biosci. 2007;12:488–495. doi: 10.2741/2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):179–187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. User’s guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I Disorders—Research version. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DG, Reynolds GL, Jaffe A, Johnson ME. Reliability, sensitivity and specificity of self-report of HIV test results. AIDS care. 2007;19(5):692–696. doi: 10.1080/09540120601087004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Fernández G, Secades-Villa R, García-Rodríguez O, Peña-Suárez E, Sánchez-Hervás E. Contingency management improves outcomes in cocaine-dependent outpatients with depressive symptoms. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2013;21(6):482. doi: 10.1037/a0033995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A, Mimiaga MJ, Israel J, Bedoya CA, Safren SA. Substance use predictors of poor medication adherence: the role of substance use coping among HIV-infected patients in opioid dependence treatment. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(1):168–173. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0319-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbeck DM, Hser YI, Lu ATH, Stark ME, Paredes A. A 12-year follow-up study of psychiatric symptomatology among cocaine-dependent men. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(11):1974–1987. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll K. The impact of psychiatric symptoms, drug use, and medication regimen on non-adherence to HIV treatment. Aids Care. 2004;16(2):199–211. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001641048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidorf M, Stitzer ML, Brooner RK. Characteristics of methadone patients responding to take-home incentives. Behavior Therapy. 1995;25(1):109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitz JD, Williams JB, Rabkin JG, Remien RH, et al. Psychopathology in male and female intravenous drug users with and without HIV infection. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151(11):1662. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.11.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas GM, Griswold M, Gebo KA, Keruly J, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. Illicit drug use and HIV-1 disease progression: A longitudinal study in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;163(5):412–420. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. A meta‐analysis of voucher‐based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101(2):192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkelä K. Studies of the reliability and validity of the Addiction Severity Index. Addiction. 2004;99(4):398–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCusker J, Stoddard AM, McCarthy E. The validity of self-reported HIV antibody test results. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82(4):567–569. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.4.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Cacciola JC, Alterman AI, Rikoon SH, Carise D. The Addiction Severity Index at 25: origins, contributions and transitions. American Journal on Addictions. 2006;15(2):113–124. doi: 10.1080/10550490500528316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, Griffith J, Evans F, Barr HL, O’Brien CP. New data from the Addiction Severity Index reliability and validity in three centers. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1985;173(7):412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina N, Farabee D, Rawson R. Treatment responsivity of cocaine-dependent patients with antisocial personality disorder to cognitive-behavioral and contingency management interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(2):320. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger DS, Woody GE, O’Brien CP. Drug treatment as HIV prevention: A research update. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;55(Suppl 1):S32–S36. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f9c10b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel AQ, Madruga CS, Cogo-Moreira H, Yamauchi R, Simões V, da Silva CJ, Laranjeira RR. Contingency management is effective in promoting abstinence and retention in treatment among crack cocaine users in Brazil: A randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2016;30(5):536. doi: 10.1037/adb0000192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacher M, Adenis A, Hanf M, Adriouch L, Vantilcke V, El Guedj M, Couppié P. Crack cocaine use increases the incidence of AIDS-defining events in French Guiana. AIDS. 2009;23(16):2223–2226. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833147c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandhare J, Addai AB, Mantri CK, Hager C, Smith RM, Barnett L, Dash C. Cocaine enhances HIV-1–induced CD4+ T-Cell apoptosis: Implications in disease progression in cocaine-abusing HIV-1 patients. The American Journal of Pathology. 2014;184(4):927–936. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast M, Podus D, Finney J, Greenwell L, Roll J. Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: A meta‐analysis. Addiction. 2006;101(11):1546–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM. Prize-based contingency management is efficacious in cocaine-abusing patients with and without recent gambling participation. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;39(3):282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Carroll KM, Hanson T, MacKinnon S, Rounsaville B, Sierra S. Contingency management treatments: Reinforcing abstinence versus adherence with goal-related activities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(3):592. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Marx J, Austin M, Tardif M. Vouchers versus prizes: contingency management treatment of substance abusers in community settings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(6):1005. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Barry D, Alessi SM, Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM. A randomized trial adapting contingency management targets based on initial abstinence status of cocaine-dependent patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(2):276–285. doi: 10.1037/a0026883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Tedford J, Austin M, Nich C, Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ. Prize reinforcement contingency management for treating cocaine users: how low can we go, and with whom? Addiction. 2004;99(3):349–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Weinstock J, Alessi SM. A randomized trial of contingency management delivered in the context of group counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79(5):686. doi: 10.1037/a0024813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Weinstock J, Alessi SM, Lewis MW, Dieckhaus K. Group-based randomized trial of contingencies for health and abstinence in HIV patients. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2010;78(1):89. doi: 10.1037/a0016778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston KL, Silverman K, Higgens ST, Brooner RK, Montoya I, Schuster CR, Cone EJ. Cocaine use early in treatment predicts outcome in a behavioral treatment program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(4):691. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabkin JG, Johnson J, Lin SH, Lipsitz JD, Remien RH, Williams JB, Gorman JM. Psychopathology in male and female HIV‐positive and negative injecting drug users: longitudinal course over 3 years. Aids. 1997;11(4):507–515. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199704000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secades-Villa R, García-Fernández G, Peña-Suárez E, García-Rodríguez O, Sánchez-Hervás E, Fernández-Hermida JR. Contingency management is effective across cocaine-dependent outpatients with different socioeconomic status. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2013;44(3):349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shacham E, Onen NF, Donovan MF, Rosenburg N, Overton ET. Psychiatric Diagnoses among an HIV-Infected Outpatient Clinic Population. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care. 2014;15(2):126–130. doi: 10.1177/2325957414553846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss SM, Rindskopf DM, Deren S, Falkin GP. Concurrence of drug users’ self-report of current HIV status and serotest results. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2001;27(3):301–307. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200107010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrina C, Fiorazzo A, Turano A, Cacciani P, Regini C, Castelli F, Sacchetti E. Depressive disorders and personality variables in HIV positive and negative intravenous drug-users. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2001;65(1):45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]