Significance

Cytoplasmic dynein is a complex intracellular molecular motor primarily responsible for many crucial retrograde transport functions within cells. Its mechanism is distinct from the mechanism of other transport motors and remains poorly understood. This work examines the structural dynamics of actively translocating dynein motors in single-molecule detail to reveal a previously unknown role of stalk flexibility in dynein stepping. By integrating these findings with previously published structural information, we present a unified model of the dynein translocation mechanism. A detailed understanding of this mechanism provides insight into how dynein is able to navigate around obstacles in vivo. The experimental techniques presented here may be broadly applicable to the study of rotational motions in other molecular systems.

Keywords: dynein, polarization, single molecule, TIRF, molecular dynamics

Abstract

The force-generating mechanism of dynein differs from the force-generating mechanisms of other cytoskeletal motors. To examine the structural dynamics of dynein’s stepping mechanism in real time, we used polarized total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy with nanometer accuracy localization to track the orientation and position of single motors. By measuring the polarized emission of individual quantum nanorods coupled to the dynein ring, we determined the angular position of the ring and found that it rotates relative to the microtubule (MT) while walking. Surprisingly, the observed rotations were small, averaging only 8.3°, and were only weakly correlated with steps. Measurements at two independent labeling positions on opposite sides of the ring showed similar small rotations. Our results are inconsistent with a classic power-stroke mechanism, and instead support a flexible stalk model in which interhead strain rotates the rings through bending and hinging of the stalk. Mechanical compliances of the stalk and hinge determined based on a 3.3-μs molecular dynamics simulation account for the degree of ring rotation observed experimentally. Together, these observations demonstrate that the stepping mechanism of dynein is fundamentally different from the stepping mechanisms of other well-studied MT motors, because it is characterized by constant small-scale fluctuations of a large but flexible structure fully consistent with the variable stepping pattern observed as dynein moves along the MT.

Dynein is a molecular motor that walks processively toward the minus end of microtubules (MTs) in an ATP-dependent manner (1–3). Axonemal dyneins drive the motility of eukaryotic cilia and flagella, whereas cytoplasmic dynein is responsible for a wide range of functions within eukaryotic cells, including the retrograde transport of cargo such as autophagosomes in neurons (4), alignment of the mitotic spindle (5, 6), and chromosome segregation during mitosis (7). Disruption of dynein-mediated neuronal transport has been implicated in neurodegeneration (8), and mutations in dynein and dynein-associated proteins can cause a range of diseases, including spinal muscular atrophy (9, 10), lissencephaly (11) and Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 2 (reviewed in ref. 12). Despite the importance of dynein function, the mechanism by which dynein walks along the MT is not yet well understood.

The motor domains of dynein are formed from six concatenated AAA domains, interrupted by a long, antiparallel, coiled-coil stalk that emerges from AAA4 and terminates in the microtubule-binding domain (MTBD) and the buttress that extends from AAA5 and is thought to stabilize the stalk (13, 14). Two motor domains form a dimer via their N-terminal tails (2, 3). ATP binding and hydrolysis drive dynein mechanochemistry; the binding of ATP to AAA1 induces a conformational change leading to dissociation of the MTBD from the MT. Hydrolysis on the dissociated head induces a primed conformation that then rebinds to the MT. The forward step, or power stroke, is coupled to release of phosphate and ADP (15–17). The “linker domain,” which spans the face of the AAA ring and connects the tail to AAA1, undocks and moves across the face of the ring upon ATP binding to AAA1 (18) and has been shown to play an important role in the translocation mechanism (19, 20). How this motion of the linker leads to cargo translation toward the minus end of the MT is unclear.

Although high-resolution electron microscopy (EM) and X-ray experiments have provided detailed information about structural changes among the different nucleotide states of dynein, single-molecule studies have provided dynamic information on motions along the MT. Dynein walks along MTs with a variable step size (21) using a combination of hand-over-hand and inchworm stepping (22, 23). Step size and the likelihood of the leading or trailing head to step are regulated by head-to-head separation (22, 23). Dynein also takes frequent sideways and backward steps (21, 24). Such a variable stepping mechanism is unique among molecular motors, because the most studied myosins and kinesins tend to move more unidirectionally and consistently in a hand-over-hand manner (25–28).

Multiple models have been proposed to explain the stepping mechanism of cytoplasmic and axonemal dynein. These models are based on structural and biophysical studies as well as comparison with mechanisms of other transport motors, such as myosin and kinesin. A classic power-stroke model suggests that, analogous to myosin V (28), the stalk rotates about a fixed point, the MTBD, and acts as a lever arm to produce translation of the ring and cargo (Fig. 1A) (29). EM studies with both cytoplasmic (30, 31) and axonemal (32) dynein provide some support for stalk rotation. Rotations of the ring may enable dynein to reach various tubulin subunits during a step (33). In contrast, other structural studies of axonemal dynein report that the stalk and ring domain rotate much less relative to the MT throughout different nucleotide states (34, 35). In an alternate model to a power-stroke mechanism, the stalk and ring adopt an almost fixed orientation relative to the MT and the linker acts as a lever to produce force by straightening and thereby pulling cargo forward (14, 31, 36) (Fig. 1B). This model is sometimes referred to as a winch mechanism (36, 37).

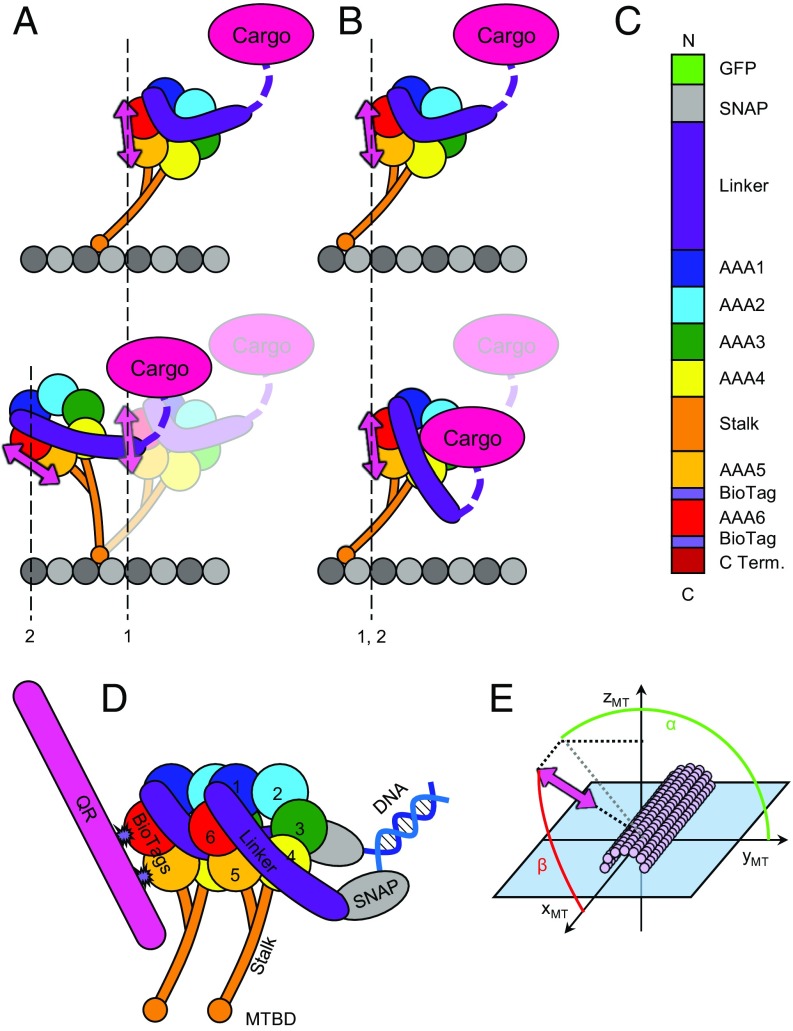

Fig. 1.

(A) Power-stroke stepping model. The ring and the stalk tilt with respect to the MT as a rigid lever arm, resulting in translocation of both the cargo and the motor domain from position 1 to position 2. In this model, the fluorescent probe used in this study (pink doubled-headed arrow) would translocate from position 1 (prepower stroke) to position 2 (postpower stroke) and undergo a rotation of the same magnitude as the ring and stalk. (B) Linker swing or winch stepping model. The ring and stalk maintain a relatively fixed orientation with respect to the MT. Translocation of the cargo is a result of linker (violet segment) straightening in a working stroke and docking to the ring. The probe undergoes little or no translocation or rotation during this conformational change. (C) Domain organization of the 331-kDa tail-truncated and doubly biotinylated dynein construct. Biotinylation target sequences (light purple, “BioTag”) are inserted in AAA5 and AAA6 of the ring domain. C Term., C terminus. (D) Schematic of the heterodimeric dynein construct. Dynein is dimerized via short cDNA oligonucleotides covalently attached to SNAP tags at the dynein N terminus. Heterodimeric constructs contain one doubly biotinylated head, as shown in C, and one wild-type head that lacks the BioTags. (E) Definition of probe orientation angles with respect to the MT frame of reference. The x axis points toward the direction of dynein motion (the minus end of the MT). The y axis is in the plane of the microscope slide. Angles are expressed in terms of α (green), the azimuthal angle of the probe around the MT, and β (red), the probe angle relative to the MT axis.

We used a single-molecule method combining polarized total internal reflection fluorescence (polTIRF) microscopy with nanometer localization to measure the 3D orientation and position of the ring domain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cytoplasmic dynein while walking along MTs in real time. To the extent that the base of the stalk, stabilized by the buttress, remains fixed relative to the ring, motions of the ring relate to flexibility of the connection through the stalk to the MT. The extent of these motions as dynein generates force along the MT will help to discriminate between models describing the underlying molecular mechanisms. Fluorescent semiconductor quantum rods (QRs) exhibit polarized emission and were used to label the AAA ring at a fixed angle and track its position and orientation over time. We observed that the ring undergoes small, frequent angle changes with a mean of 8°. Surprisingly, angle changes were only weakly coupled to stepping. Angle changes occurred more than twice as often as steps along the MT track, suggesting unexpected flexibility of the dynein stalk. Angular measurements were collected for dyneins labeled at two independent sites on opposite sides of the ring. The mean probe angle differed for the two sites, but the magnitude and dynamics of the angle changes were very similar. We used molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to investigate further the degree of flexibility within the stalk and hinge region connecting the MTBD. These data again emphasize the role of flexibility and argue against a mechanism in which the working stroke results from the tilting of the MT-binding stalk. Instead, these data support a model in which interhead strain produces opposing torques in the two heads, resulting in bending of the stalk and hinging at the MTBD. This flexibility can account for the variability of dynein stepping patterns. Together with recent EM data (30, 35), our observations support a unique stepping mechanism for an essential cellular motor based on docking of the linker and flexing of the stalk.

Results

Labeling Dynein with Polarized Quantum Nanorods for PolTIRF Measurements.

To visualize ring rotations and translations with high resolution, we tightly coupled polarized QRs to the dynein ring at specific locations. We used a well-characterized 331-kDa, tail-truncated cytoplasmic dynein construct in which the dynein heads were dimerized by DNA oligonucleotides. These constructs were previously shown to exhibit velocities and run lengths similar to the full-length molecule (21, 23). The dynein ring was labeled by inserting biotinylation sites (38) either in AAA5 and AAA6 (Fig. 1 C and D) or in AAA2 and AAA3. Both doubly biotinylated constructs showed ATP-dependent velocities similar to the constructs lacking the insertions (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), indicating that insertion of the biotinylation sites does not disrupt motor activity. NeutrAvidin-coated QRs, which have well-polarized fluorescence emission, were attached bifunctionally to the two biotinylation sites using a biotin-avidin linkage (39, 40). Initial experiments with QRs containing much lower NeutrAvidin density yielded highly variable and fluctuating orientations, indicating that bifunctional attachment produces a fixed orientation of the QR relative to the dynein ring. The inserted biotin target sequences did not disrupt processive motor activity, but rod binding decreased observed translocation velocities (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). This slowing may be a result of drag due to the size of the QR or interactions of the QR with the MT or slide surface. Of note, constructs with QRs spanning AAA5 to AAA6 and AAA2 to AAA3 show similar slowing (SI Appendix, Table S1), suggesting that it is not a result of constraining the relative motions of the AAA domains (e.g., between AAA5 and AAA6) and does not qualitatively change the mechanical properties of the motor.

To measure tilting of the dynein ring domain concurrent with stepping, we developed a method for polTIRF imaging using an EMCCD camera as a detector. This technique was modified from methods previously used to measure the tail rotations of myosin V (41). Here, circularly polarized light excites the fluorescent sample; the emitted fluorescence is split into four components, polarized at 0°, 45°, 90°, and 135° around the optical axis, and is projected onto the camera detector in a spatially separated manner (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). The orientation of the probe emission dipole, parallel to the long axis of the QR (39), is determined from the relative intensities of the four component polarized fluorescence intensities in each image (42). Orientation is expressed in terms of angles α and β relative to the MT (Fig. 1E). Position is measured at subpixel resolution by fitting a Gaussian distribution (26) to the total image of each QR, accurately combined from all four channels. We confirmed that this approach can appropriately detect orientation changes of the probes by imaging labeled dynein bound to axonemes on a rotating stage in the absence of ATP (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

The Dynein Ring Tilts While Stepping.

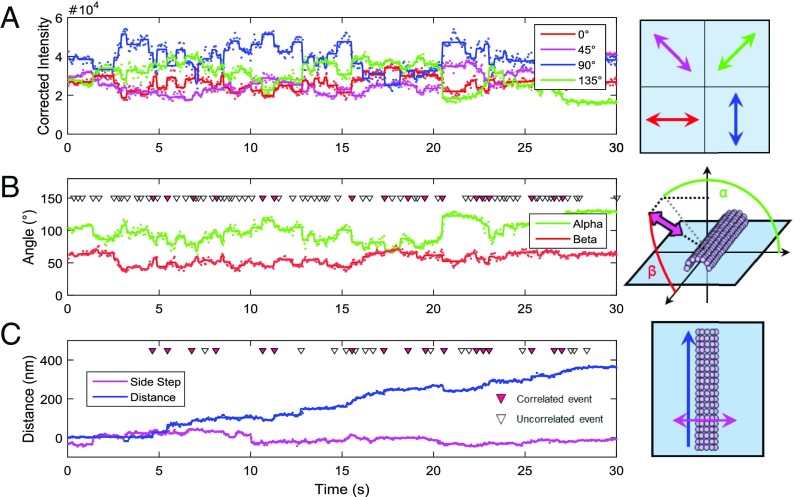

Dynein motors labeled with a QR were tracked using polTIRF while moving processively along MTs. We focused initially on constructs labeled with QDs spanning between AAA5 and AAA6. The position and orientation of single-dynein motors were measured simultaneously (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Consistent with previous work, single-molecule tracking of dynein’s position along the MTs revealed forward and backward steps of variable size (21, 43) (Fig. 3A), indicating that the presence of the QR does not disrupt dynein’s stepping mechanics. During motility, the dynein ring tilts both azimuthally around the MT, in α, and axially in the plane of the MT, in β (Fig. 2B). Change point analysis (44) was used to detect abrupt changes in α or β (or both) objectively with 95% confidence. Contrary to expectations based on EM imaging in the plane of the dynein ring (30–32, 35), rotational changes in α and β were similar in both frequency and magnitude (Fig. 3 B and C), with <|Δα|> = 6.7° ± 0.17° (SEM) and <|Δβ|> = 5.47° ± 0.1° (SEM). The measured angle changes assume that the polarized probe is oriented in the plane of the dynein ring. To determine the possible effect of the probe binding to dynein out of the plane of the ring, we calculated the angular distributions if the probe had been randomly oriented. The adjusted values are <|Δα|> = 11.4° and <|Δβ|> = 9.95°. The actual magnitudes of the ring rotations are likely in between these adjusted values and the measured values listed above because both represent extreme cases. This adjustment does not affect our conclusions; thus, for consistency, all further analysis assumes the probe is oriented in the plane of the ring.

Fig. 2.

(A) Polarized fluorescence intensities measured at 0° (red), 45° (magenta), 90° (blue), and 135° (green) with respect to the microscope x axis and normalized for differential channel sensitivity. Dots represent the values measured in each camera frame, and bold lines are the same data averaged between identified state transitions or change points (Materials and Methods). (B) Probe angles α (green) and β (red) calculated from the intensities in A. Dots denote angles calculated from frame-by-frame intensities, whereas solid lines show the angles calculated from the intensities averaged between change points. (C) Distance traveled along the path of the MT (blue) or the sideways deviations from that path (side steps, magenta) by the same dynein motor shown in A and B. Dots show the positions of the dynein measured in each frame, and solid lines are the positions averaged between steps identified as change points. Triangles mark the times of detected angle changes (B) or steps along the MT path (C). Correlated steps and angle changes are marked with solid red triangles, whereas uncorrelated angle changes (B) and steps (C) are marked with open triangles. Data were collected at 100 μM MgATP.

Fig. 3.

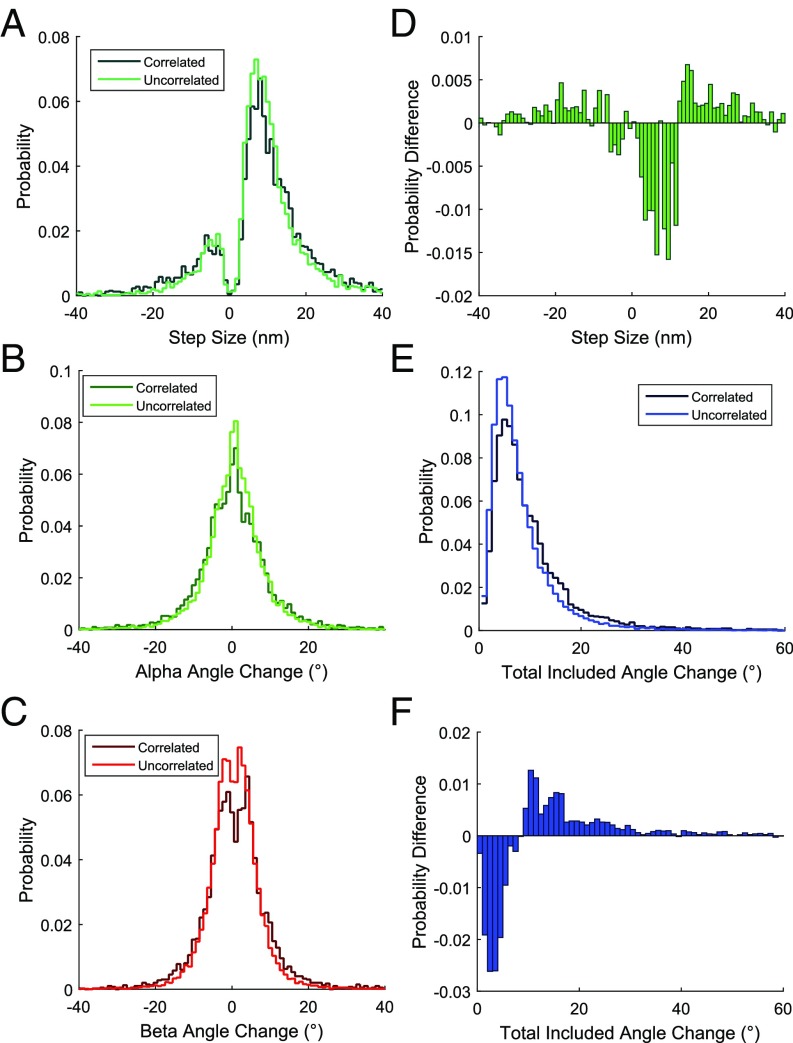

Histograms of all step sizes and angle changes for all events measured at 100 μM ATP with QRs attached to AAA5 and AAA6 (Nmotors = 142). (A) Probability distribution of step sizes either correlated with an angle change (green) or not correlated with an angle change (uncorrelated, dark green). Histograms were normalized so that the total heights of all of the bars add up to 1.0. Probabilities are then calculated directly from histogram bar heights. A step change and angle change were considered correlated if they occurred within one frame (50 ms) of each other (Ncorrelated = 3,972, Nuncorrelated = 4,361). Probability distributions of α (B, green), β (C, red), or total included (E, blue) angle changes either correlated with a step (correlated, darker lines) or not correlated with a step (uncorrelated, lighter lines) are shown (Ncorrelated = 3,972, Nuncorrelated = 15,010). (D) Probability difference between the step size distributions plotted in A (correlated step probability minus uncorrelated step probability). (F) Probability difference between total included angle change distributions plotted in E (correlated angle change probability minus uncorrelated angle change probability).

Next, we calculated changes in the total included angle, defined as the spherical arc between the orientations before and after each step (Fig. 3E). This analysis indicated that tilting events were more frequent than steps: On average, 2.2 angle changes occur per step at 100 μM ATP (Table 1). Typical angle changes were small [8.3° ± 0.1° (SEM)], with 95% of total included angle changes less than 21°. We measured the same values for dynein walking along axonemes instead of MTs and found the total included angle to be only slightly larger (9.13° ± 0.19°). The magnitude of these angle changes suggests small reorientations of the ring relative to the MT rather than large conformational changes predicted by a power-stroke model (Discussion). The distributions for only those angles occurring with a standard 14- to 18-nm step appear similar to the distributions of all angles (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), suggesting that potential disruption to the stepping pattern caused by binding of the QR does not alter the mechanics of the ring motions.

Table 1.

Step and angle change rates as determined by fitting double exponentials to dwell time distributions

| Nucleotide | Fast stepping rate, s−1 | Slow stepping rate, s−1 | Fast angle change rate, s−1 | Slow angle change rate, s−1 | No. of angle changes per step (average) | Steps correlated with angle changes, % | Angle changes correlated with steps, % |

| None | 9.06, +4.01, −2.35 | 0.758, +0.068, −0.062 | 5.03, +1.359, − 0.922 | 0.936, +0.223, −0.223 | 2.508 | 33.06 | 13.67 |

| 25 μM ATP | 5.93, +0.843, −0.665 | 1.465, +0.098, −0.093 | 6.90, +2.057, −1.094 | 1.87, +0.349, −0.315 | 2.213 | 43.66 | 20.04 |

| 50 μM ATP | 5.06, +0.456, −0.439 | 1.539, +0.070, −0.058 | 6.93, +1.085, −0.876 | 1.88, +0.268, −0.298 | 2.318 | 46.03 | 20.49 |

| 100 μM ATP | 5.19, +0.351, −0.343 | 1.594, +0.055, −0.049 | 6.38, +0.501, −0.453 | 1.76, +0.204, −0.189 | 2.307 | 47.00 | 20.91 |

| 200 μM ATP | 5.31, +0.455, −0.445 | 1.702, +0.082, −0.083 | 6.42, +0.736, −0.641 | 1.82, +0.224, −0.253 | 2.109 | 45.08 | 21.96 |

| 100 μM ADP | 10.68, +4.17, −2.99 | 0.820, +0.071, −0.058 | 3.46, +0.985, −0.500 | 0.619, +0.191, −0.130 | 1.8711 | 27.41 | 14.97 |

Numbers of angle changes per step are listed regardless of correlation. The percentages of correlated steps or angle changes were calculated as the numbers of correlated steps or angle changes divided by the total numbers of steps or angle changes. Because there were more angle changes than steps, the correlated events were a smaller fraction of all angle changes than they were of steps. Upper (+) and lower (−) 95% CIs were determined by bootstrapping.

We compared angle changes that were correlated with steps along the MTs with angle changes that were not correlated with steps. A step and an angle change were considered correlated if they occurred within one frame (50 ms) of each other as determined by change point analysis. Only 20.9% of angle changes were correlated with steps at 100 μM ATP, indicating that ∼80% of the angle changes occur while the labeled head is bound to the MT. Conversely, 47.7% of steps were correlated with angle changes (Table 1). The difference between the fraction of correlated steps and the fraction of correlated angle changes is due to the higher number of angle changes. The number of angle changes correlated with steps and the number of steps correlated with angle changes are the same. Due to the higher frequency of angle changes, the ratio of correlated events to the total number of angle changes (0.209) is smaller than the ratio of correlated events to the total number of steps (0.477). Although some of the uncorrelated angle changes can be attributed to stepping of the unlabeled head, which would not be seen in the position trace, the majority appear to reflect the pronounced flexibility of the dynein motor domain. This frequent tilting, together with the small magnitude of the angle changes, suggests that dynein is flexible, adopting a range of different conformations throughout translocation.

Angle changes that are correlated with steps tend to be slightly larger than angle changes that are uncorrelated; this trend can be seen in a difference histogram as a depletion of the population of smaller angle changes and an increase in the population of larger angle changes (Fig. 3F). Similarly, both forward and backward steps that are correlated with angle changes tend to be larger than uncorrelated steps (Fig. 3D). Within the subset of events exhibiting both a step change and an angle change, the magnitudes of steps and angle changes are loosely correlated, with large variability in the size of angle changes (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). In correlated events, the dynein ring tilts 0.22° [95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.1874–0.2693°] per nanometer of step size along the axis of the MT, demonstrating a very slight positive correlation between step size and the magnitude of angle change (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). This relationship suggests that the stalk flexes or hinges at the MTBD to accommodate larger steps, resulting in our observed larger angle changes tending to increase with step size. The step dependence of angle change can be used to estimate mechanical compliance of the MT-binding stalk and the connector between the two rings (Discussion). Together, these data indicate that changing the relative position of the two heads, (i.e., taking a step) tends to produce larger angle changes than the angle changes that occur when both heads are stably bound and that the magnitude of the angle change depends on the size of the step. However, the small differences between the two populations and the occurrence of many uncorrelated events suggest that steps and angle changes are only weakly coupled. This weak coupling may contribute to dynein’s variable stepping pattern.

Dynein Tilting Detected at AAA2 and AAA3.

All of the previous results were obtained using the dynein construct with biotinylation sites in AAA5 and AAA6. To test whether the observations were general features of the dynein ring or, alternatively, were specific to this set of sites, we performed a similar series of experiments using dynein biotinylated in domains AAA2 and AAA3. Based on the positions of the inserted biotinylation sites, the angle of the QR relative to the MT would be expected to differ between the two constructs. As anticipated, the distribution of axial angles, β, of the rod relative to the MT was quite different (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), supporting the expectation that the QRs often lay across and align with the two biotinylation sites. All of the dynamic results, however, including the velocity and step size, as well as the magnitude, frequency, and correlation of angle changes, were essentially the same in the two constructs (SI Appendix, Figs. S8 and S9 and Table S1). Thus, the QRs seem to report global rotation of the ring rather than local or relative motions between AAA domains in the ring.

Tilting Frequency Shows Little Dependence on ATP Concentration.

If dynein undergoes a working stroke in which the stalk and ring tilt to produce the translocation (the classic power-stroke model), the dwell time distribution of angle changes should be tightly coupled to each step along the MT. We measured dynein stepping and tilting rates at a range of ATP concentrations from nucleotide absence up to 200 μM ATP, as well as at 100 μM ADP in the absence of ATP. Stepping dwell time distributions are fit well by single exponentials. Stepping rates are ATP-dependent (Table 1), although even some steps are observed in the absence of ATP. The ratio of forward to backward steps decreases with decreasing ATP concentration, resulting in a decrease in the forward velocity that is more pronounced than the decrease in the stepping rate.

Distributions of dwell times between angle changes were fit significantly better by double exponential decays than by single exponentials (P < 0.01), possibly indicating two distinct populations of tilts (45) (Table 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). Stepping dwell times were also fit to two-phase exponentials, consistent with stepping of the labeled head often followed by the unlabeled head (Table 1). Surprisingly, both the faster and slower components of the angular dwell time distributions are only weakly dependent on nucleotide concentrations. Although tilting and stepping rates are dependent on ATP, the ratio of steps to angle changes was constant across the nucleotide concentrations tested. Similarly, the fraction of correlated steps and angle changes remained constant. These data suggest that ring rotations are only weakly coupled with the ATPase cycle, and are therefore unlikely to be the result of a mechanism, such as a power-stroke model, in which rotational changes would be predicted to be tightly correlated with ATP hydrolysis and with stepping.

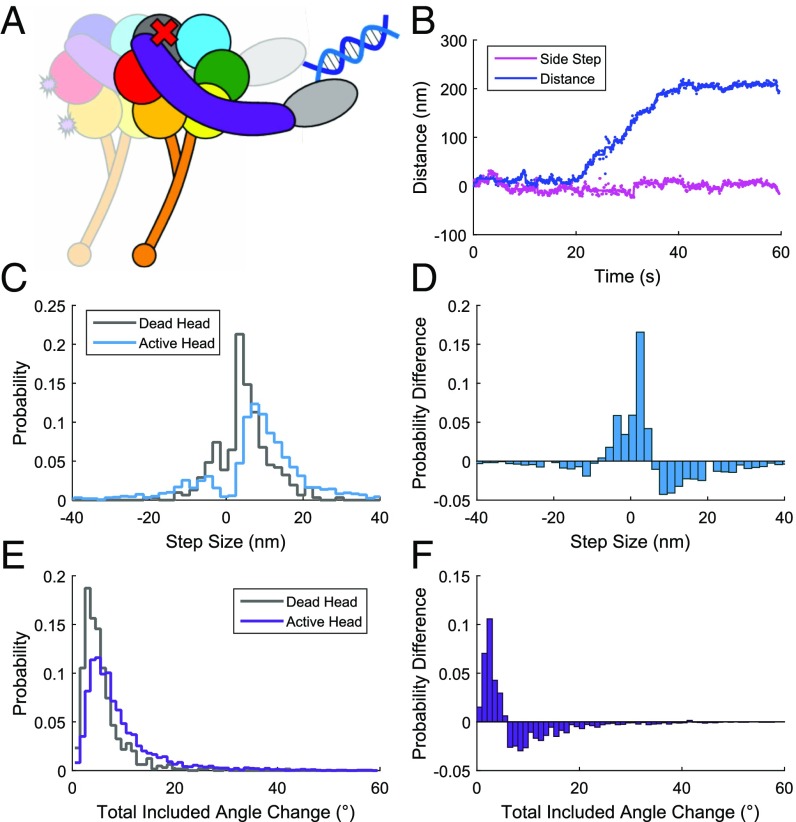

The Dynein Ring Is Constrained When Dragging an Inactive Head.

Ring rotations were also measured in the context of a heterodimer with one inactive or “dead” head (Fig. 4 A and B), because it has been shown that a dynein construct having only a single active head is still able to move processively as long as the second head retains the ability bind to the MT (46). We used a heterodimeric construct in which the active head was doubly biotinylated and labeled with a QR, whereas the other unlabeled head contained a P-loop (Walker A) K-to-A mutation in AAA1, which renders it unable to bind or hydrolyze ATP (47). This dead-head construct has smaller step sizes and angle changes than QR labeled “wild-type” dynein (Fig. 4 C–F). Ring rotations are reduced from 9.13° ± 0.19° to 5.22° ± 0.16° (SEMs) total included angle change when walking along axonemes. The dead head is presumably dragged behind the active one (48), apparently limiting the flexibility or range of motions of the active head. The processive motility of this QR-labeled dead-head heterodimer, albeit at a slower velocity, indicates that the QR does not suppress activity of the labeled head (Fig. 4 A and B). Although the velocity is reduced with QRs bound, the mechanics are thus not markedly disrupted.

Fig. 4.

Steps and angle changes of a “dead-head” heterodimeric construct measured at 100 μM MgATP on axonemes (Nmotors deadhead = 13, Nmotors WT = 38). (A) Schematic of the dynein heterodimer construct used in this experiment. One head contains a lysine-to-alanine mutation at residue 1,802, which renders it unable to bind ATP in AAA1, creating a dead head (denoted by a red x). The active head contains the two biotinylation sites as shown in Fig. 1C. The two heads are dimerized using cDNA oligonucleotides bound to their respective N-terminal SNAP tags. (B) Distance traveled along the path of an axoneme (blue) or sideways deviations from the path (side steps, magenta) by a single dynein motor tracked using QR fluorescence. Dots are the position measured in each camera frame, and solid lines are positions averaged between detected steps. (C) Probability distribution of step sizes of a QR-labeled heterodimer paired with either a dead-head mutant (gray) or an active wild-type head (blue) on axonemes (Ndeadsteps = 310, NWTsteps = 1,616). (D) Probability difference of the data plotted in C, dead-head construct steps minus active construct. (E) Probability distribution of total included angle changes of a QR-labeled heterodimer paired with either a dead-head mutant (gray) or an active wild-type head (purple) (Ndeadangles = 646, NWTangles = 3,107). (F) Probability difference of the data plotted in E, dead-head construct minus active head construct.

Angle Changes Reflect Dynein Flexibility.

Forces from the dynein ring are applied to the MT through the α-helical coiled-coil stalk and globular MTBD domain during translocation. Rotational motions of the ring thus depend on these forces and the mechanical compliance of the stalk and MTBD hinge. Previous EM studies of axonemal dynein suggest that there is a slight bending of the stalk during translocation (35), whereas EM studies of isolated cytoplasmic dyneins support the presence of a hinge at the MTBD (30). Because both bending of the stalk and hinging at the MTBD could explain our observed small ring rotations, we performed an MD simulation for a system comprising the dynein stalk and MTBD to examine the contributions of stalk flexing and hinging to the overall flexibility. Although an earlier simulation study (49) calculated motions of the stalk and MTBD over 50 ns, we extended the time scale to 3.3 μs (among other differences; Materials and Methods) to sample motions more thoroughly at thermal equilibrium. The mechanical characterizations based on simulation data considered 8.8 nm of the distal stalk coiled-coil region, approximately the flexible portion of the stalk that extends outward from the buttress, as well as the MTBD (residues 2,918–3,165). Simulations were performed based on the prepower-stroke conformation of dynein, because thermal motions that signal flexibility cannot be sampled with the stalk tethered to the MT and the postpower-stroke conformation of the stalk may be unstable without MT contact (2). The registry shift between the prepower- and postpower-stroke states (50) is unlikely to cause a major change in flexibility (31). Movie S1 shows an animated rendering of the MD simulation.

The persistence length, Lp, of the dynein coiled-coil, calculated by tangent correlation analysis of conformations sampled in the MD simulation, was estimated to be 250 nm (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Considering the dynein stalk as a rigidly anchored cantilever, the mechanical stiffness at the free end for the first bending mode is given by κs = 3 Lp kBT/Lc3, where kBT = 4.28 × 10−21 J at the 310 K temperature of the MD simulation and Lc = 8.8 nm contour length. The corresponding stiffness of the stalk at the free end is 4.7 pN/nm.

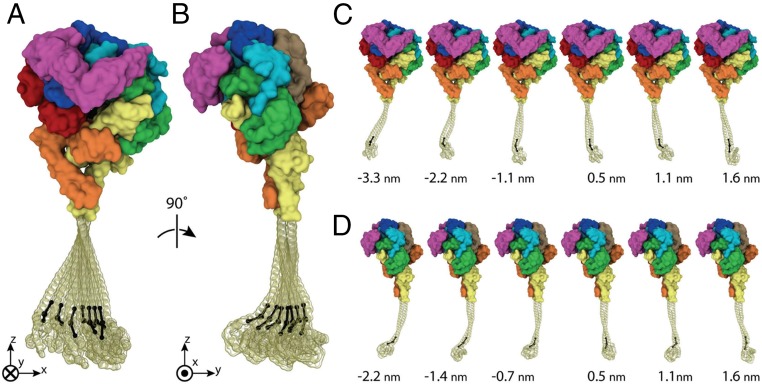

Notably, the data in the tangent correlation plot (SI Appendix, Fig. S10) do not form a perfectly straight line, suggesting that the flexibility of the coiled-coil is not homogeneous along its length. Frames from the MD simulation were aligned with respect to the heptad at the base of the stalk to evaluate lateral fluctuations of the distal tip of the stalk, measured as the joint between the stalk and MTBD (the hinge vertex). As suggested by tangent correlation analysis, the fluctuations are not symmetrical, but are somewhat higher in amplitude in the direction parallel to the plane of the dynein ring (defined here as the x-direction; Fig. 5A and SI Appendix, Fig. S11A) than in the direction perpendicular to the ring (defined as the y-direction, Figs. 5B and SI Appendix, Fig. S11A). The SDs and values of variance of these fluctuations are σx = 0.97 nm, <x2> = 0.938 nm2 and σy = 0.73 nm, <y2> = 0.532 nm2 in the x- and y-directions, respectively. The source of this difference is the ribbon-like, rather than cylindrical, nature of the coiled-coil. This influence of coil shape on flexibility in the x- and y-directions can be seen from the still views from the simulation in Fig. 5 C and D and in Movie S1.

Fig. 5.

All-atom MD simulations of the dynein stalk demonstrate its flexibility along the coiled-coil region and at the MTBD hinge. An overlay of seven representative frames, each from the ensemble of 330,000 collected over 3.3 μs, selected to illustrate 99% of the structural distribution of stalk positions in the plane of the ring (A) and perpendicular to the plane of the ring (B) is shown. Distributions are determined with respect to alignment of the stalk to the heptad at its base (as described in Materials and Methods) and capture the distal tip of the stalk (hinge vertex) at its point closest to zero displacement and three equally spaced displacements out to ±2.5 SD in each plane. (C and D) Individual frames from A and B, with displacement of the distal tip of the stalk (hinge vertex) indicated in nanometers. Images were rendered using VMD 1.9.2 (64).

At the base of the coiled-coil, just below the stalk/buttress joint, the two component α-helices line up side by side nearly perpendicular to the plane of the ring (Fig. 5A), leading to higher flexibility in the plane of the ring, which is also the expected direction of the MT (the x–z plane; Fig. 5C). Approximately one-half to two-thirds of the way farther along the stalk, the flat face of the coiled-coil ribbon is rotated ∼90°, such that the two helices line up parallel to the ring (Fig. 5B), conferring flexibility perpendicular to the ring and MT (the y–z plane; Fig. 5D). The composite superimposed views of frames from the simulation (Fig. 5 A and B) show these flexions; the majority of lateral fluctuations within the plane of the ring stem from bending at the base of the coiled-coil, from which the extended stalk represents a longer lever; the majority of lateral fluctuations perpendicular to the ring stem from the bending closer to the tip, following the ∼90° rotation of the ribbon.

The apparent stiffness of the tip of the stalk was calculated based on lateral fluctuations of the distal end of the coiled-coil (stalk/MTBD hinge vertex) applying the fluctuation/dissipation relation, , producing values of κsx and κsy of 4.56 and 8.05 pN/nm in the ring-parallel (x) and ring-perpendicular (y) directions, respectively. These stiffness values are pertinent to considering tilting motions in relation to intermolecular forces between the rings. Because the stiffness value computed from Lp more closely matches the stiffness estimated in the x-direction based on the rigid cantilever approach, this analysis indicates that overall stalk flexibility is dominated by fluctuations in the plane of the ring, which correspond roughly to the plane of the MT.

Similar analysis of the fluctuations in longitudinal twisting of the stalk leads to κt = 75.9 pN/nm per radian torsional stiffness. The corresponding torsional persistence length, Lpt = κt⋅Lc/kBT = 156 nm, is comparable to the value (100 nm) for a coiled-coil estimated by Wolgemuth and Sun (51) using a coarse-grained model of two interwound α-helices. Frames from the MD simulation were aligned with respect to a theoretically bound MT to characterize the compliance of the stalk/MTBD hinge. Rotational stiffness of the hinge in the plane of the MT (related to β-angle) and azimuthally around the MT (related to α-angle) are κhx = 41.5 and κhy = 136.1 pN/nm per radian, respectively. The axis of rotation of the hinge is very close (within ∼3° on average) to parallel to the MT axis (i.e., rotation of the stalk about that hinge is mainly in the plane of the MT). These values are used in the following section (Discussion) to estimate the forces in the linkers and segment connecting the rings related to tilting of the rings.

Discussion

Using our method of combined polTIRF and subpixel localization, we determined 3D orientation measurements of the dynein motor during active translocation in real time. We simultaneously measured the position and orientation of the AAA ring domain of S. cerevisiae cytoplasmic dynein and found that the ring tilts during processive stepping, enabling us to expand upon previously proposed stepping models. Rotations of the ring domain are quite small, frequent, and only loosely coupled with stepping. These dynamic observations allow us to rule out a classic power-stroke mechanism of stepping because the measured angle changes are too small and uncorrelated. Instead, our results suggest a flexible stalk model defined by frequent small-angle changes that are only weakly correlated with stepping and are related to flexibility of the stalk and MTBD hinge, as well as tension between the two heads. This model is consistent with the elegant EM studies looking at dynein bound to MTs in both primed and unprimed conformations. These structural approaches suggest only small differences in orientation of the ring relative to the MT between the two states (30, 35).

The Power-Stroke Model of Dynein Stepping.

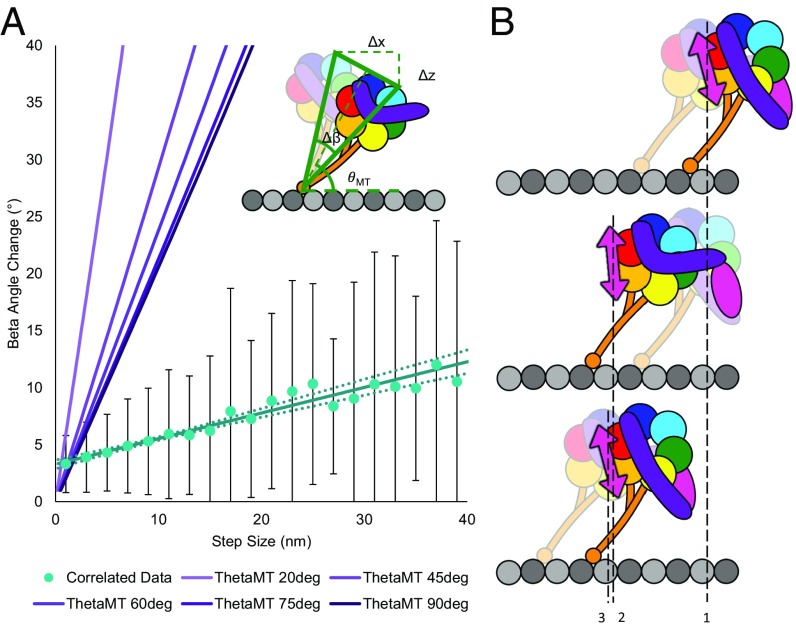

A power-stroke model of stepping, characteristic of the myosin V motor lever arm, involves the tilting of the lever arm in the leading filament-bound head, generating tension on the trailing head, which swings forward during a step. Applying this type of model to dynein, when the trailing head detaches from the MT and moves forward to produce a step, the stalk and ring of the attached head would tilt relative to the MT, possibly hinging at the MTBD (Fig. 6A). The biotinylation sites in our dynein construct are positioned ∼28 nm from the MTBD. Based on this geometry, the simplest tilting stalk model would predict greater than 30° of rotation of the ring in the plane of the MT (β) to produce a typical 16-nm step, or 25° of rotation to produce our observed mean forward step size of 12 nm. These predictions are in striking contrast to our observation that 95% of β-angle changes are less than 15°, with a mean of 5.4°.

Fig. 6.

(A) Magnitudes of β-angle changes correlated with forward steps as a function of step size (teal points). Magnitudes of correlated forward steps and β-angle changes are gathered and averaged in 2-nm bins. Error bars are SDs of the angle changes in each bin. The data are fit by a line with a slope of 0.22° (95% CI = 0.1874–0.2693°) per nanometer of fluorophore (ring) translocation along the MT. CIs for the fitted line, determined by bootstrapping (45), are marked by dotted lines. Purple lines show the expected β-angle change (Δβ) as a function of step size predicted if dynein were to step using a rigid-stalk power stroke (Inset). The predicted shape of the step size and angle change relationship depends on the angle of the stalk relative to the MT (θMT, Inset), shown by different shades of purple lines, with θMT [in degrees (deg)] increasing as the lines become darker. The data do not fit the power-stroke model, which would predict larger angle changes with magnitudes closely related to the step size. (B) Flexible stalk model supported by observed small and frequent angle changes. Stalk flexing due to interhead torsion causes small ring rotations both when the labeled head steps (probe, denoted by pink arrow, position 1 to position 2), resulting in an angle change correlated with a step, and when the unlabeled head steps (probe position 2 to position 3), resulting in an angle change not correlated with a step.

An additional prediction of the tilting stalk power-stroke model is that rotations of the ring would be tightly coupled to stepping and the ATPase cycle. Thus, a translocation should be observed each time the ring tilts due to the long distance between the probe and the postulated point of hinge rotation at the MTBD junction near the MT. There should also be a direct correlation of step size and in-plane rotation (β) following the equation Δx = 2l⋅sin(Δβ/2), where Δx is the step size, l is the distance from the point of rotation to the fluorescent probe (∼28 nm), and Δβ is the change in the β-angle. This relationship is nearly linear for angle changes less than about 50°. At 100 μM ATP, less than 21% of the observed angle changes occur simultaneously with a step; yet, even if only the subset of angle change events that occur with steps is compared, the sizes of steps and angle changes are only weakly correlated, and the relationship predicted by the stalk-stroke model (violet lines in Fig. 6A) markedly overestimates the measured rotations (green points in Fig. 6A).

Together, these results provide strong evidence against a stepping mechanism for dynein in which force is produced exclusively by a tilting stroke of the MT-binding stalk. Instead, our data suggest a less strict mechanism where rotations of the ring are not tightly coupled to steps, but are instead a product of dynein’s flexibility and interhead tension. Our results are consistent with EM data obtained from axonemal dynein, which suggest that the angle of the dynein stalk relative to the MT does not change markedly with nucleotide state in the head (34, 35).

The Flexible Stalk Model of Dynein Stepping.

In our proposed stepping model (Fig. 6B), the stalk and ring remain at an almost fixed orientation relative to the MT, whereas changes in nucleotide state regulate dynein’s affinity for the MT and cause conformational changes of the linker. When dynein undergoes a forward step in which the trailing head becomes the leading head (Fig. 6B, Top to Middle transition), tension transmitted through the linker changes from a forward pulling force to a backward pulling force. Thus, the stalk, which was bent forward, is now bent in the opposite direction, and the ring rotates. This mechanism is consistent with previous work showing that the size and magnitude of steps are related to the interhead distance (22, 23), and that the stepping rate depends on the magnitude and direction of an applied force (43). A larger step size results in a larger change in the interhead distance and a greater change in the interhead tension. This finding is demonstrated by the positive correlation between the step size and magnitude of the correlated angle change (Fig. 6A). As interhead distance increases, the tension between the two heads increases, resulting in greater rotation of the ring. Very large steps observed may be due to multiple steps occurring within a single camera frame or to brief detachments and reattachments to the MT. The correlation between step size and rotation is weak, however, indicating considerable variability among individual steps, again fully consistent with the overall flexibility characteristics of the dynein motor. Steps often occur in the absence of angle changes. Many of these steps are small translocations that presumably alter the interhead distance and tension only slightly. Larger steps without tilting may result from low-tension trailing to low-tension leading transitions. Angle changes that occur without a step are likely often the result of steps by the unlabeled head. However, they may also be caused by flexible transitions, with the discrete angles indicating local energetic minima.

In a mechanism where linker straightening results in translocation, the ring and stalk would remain at a relatively fixed orientation with respect to the MT (34, 36). However, the model does not require that they remain completely fixed. Instead, intramolecular forces between the two heads of the double-headed attached state are predicted to cause the small tilting motions observed in this study. There are two possible ways that the orientation of the ring domain could change in the context of a flexible stalk mechanism. The first possible cause is hinging at the MTBD. This possibility is supported by EM analysis of Dictyostelum cytoplasmic dynein, which detected variable angles between the MT and dynein (30). Hinging at the MTBD could result in orientation changes both in the plane of the MT (β) and around it (α), although according to our results, the hinge and stalk flexibilities are greater in β than in α. This hinging is distinct from a stalk power-stroke mechanism in which the tilting is the main cause of translocation and a requirement for stepping. The second possible cause of ring rotation is stalk flexing, which is compatible with the MD simulations and with EMs of axonemal dynein (36). In the flexible stalk mechanism, dynein can step without hinging.

Mechanics of Dynein Tilting.

QRs spanning two distinct labeling sites from AAA5 to AAA6 and from AAA2 to AAA3 gave very similar dynamics and angle changes (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S9 and Table S1). This result indicates that the small magnitude of the angle changes and their weak correlation with stepping along the MT are not properties of one location on the structure or relative motions between the domains during the mechanochemical cycle, but apply broadly to the whole ring. The angle, β, of the QR relative to the MT axis differs between the two constructs, as expected from the different positioning of the biotinylation sites. The highest peaks in the distributions of β-angles for the two constructs differ by 31° (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), which is in close agreement with the expected angle (35°) between lines drawn through the two pairs of biotinylation sites in the crystal structure [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 4AKG] (52). Both of these lines are in the plane of the ring. This result implies that the ring is oriented in the plane of the MT. If the ring were oriented perpendicular to the MT, then the β-angles of QRs on the two constructs would be the same, whereas the azimuth angles, α, would differ. Thus, the different β-distributions strongly support the notion, derived from many EM studies (30–32) but shown here for dynein while it is active, that the ring is approximately parallel to the MT.

The mechanical characteristics of the stalk and stalk/MTBD hinge can be related to the tilting of the dynein ring, measured from the polarized fluorescence intensities of the QRs bound to the ring, assuming the stalk emerges from the stalk/buttress joint at a fixed angle. Mechanical compliance (Cs) in the direction of the MT axis is given by = 0.93 nm⋅pN−1, where θ is the angle of the stalk relative to the MT, κsx (piconewtons per nanometer) is the bending stiffness of the stalk, and κhx (piconewtons per nanometer per radian) is the torsional stiffness of the stalk/MTBD hinge. Approximately 90% of this compliance is derived from the hinge, and 10% of it is due to bending of the stalk.

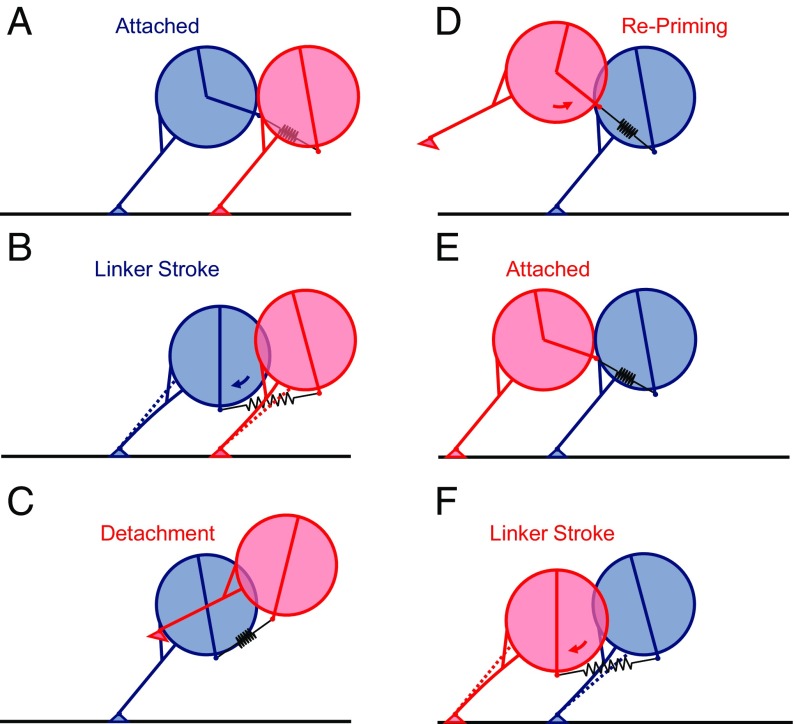

When the two stalk heads are bound a total distance, dt, from each other along the MT, force, Fc, in the elastic connection between the two rings (e.g., the linkers and dimerization domains) will pull the front head backward and the rear head forward (Fig. 7 B and F) by a distance of dr = Fc⋅Cs = dc⋅kc⋅Cs, where dc and kc are the extension and stiffness of the ring-ring connection, respectively. Although there is high variance, the rotational angle change per unit step size given by Fig. 6A is S = 0.22° (95% CI = 0.1874–0.2693°) per nanometer. Ring rotation per nanometer of motion along the MT, due to stalk bending and tilting, is given by Δθ/Δdr = 1/(Lc sin (θ)). Combining this equation with Cs gives = 0.025 pN⋅nm−1. This value and the estimates of other mechanical parameters are very similar to the mechanical parameters estimated from ring tilting in electron micrographs by Imai et al. (30) (SI Appendix, Table S2). Although Imai et al. (30) do not discuss stalk bending, they do note that κc is too small to correspond to the dimerized GST peptide or the hybridized DNA connecting the rings in our constructs, implying extra flexibility in the connection between the two rings, such as in the linker domains themselves.

Fig. 7.

Cartoons illustrate hypothetical steps in dynein walking. (A) Two heads in the initial attached configuration. (B) Conformational changes of the linker as it straightens from the primed state to the unprimed state, denoted by blue arrow, cause an increase in interhead tension. This tension pulls the two rings toward each other, causing flexing of the stalk, bending at the MTBD, and tilting of the rings. (C) Upon detachment of the trailing head (red), interhead tension is relieved, biasing the detached head forward. (D) Linker repriming, denoted by red arrow, in the unbound (red) head provides more forward bias to the step, increasing the likelihood that it will bind ahead (E) of its previous position. (F) New leading (red) head undergoes its power stroke, tilting the heads toward each other again.

At 8.3 nm, 16.6 nm, and 24.9 nm of separation, dt, between the MT-binding sites, the deflection sizes of the rings, dr, along the MTs are calculated to be 0.18 nm, 0.37 nm, and 0.55 nm, respectively, dt = dc + 2⋅dr = Fc⋅(1/kc + 2⋅Cs), and corresponding step sizes measured at the ring, sr = dc, are 7.9 nm, 15.9 nm, and 23.8 nm, thereby broadening the distribution of measured step sizes. Intramolecular forces at the three values of dt are 0.2 pN, 0.4 pN, and 0.6 pN, which are well within the 3- to 5-pN force-generating capability of the motor (43, 46, 53, 54).

The consequences of the flexible stalk model of dynein stepping are pictured in Fig. 7. After a head binds the MT (blue leading head in Fig. 7A), its linker domain straightens to pull the cargo and partner head forward toward the minus end of the MT (Fig. 7B). Due to hinging at the stalk/MTBD hinge and due to cantilever bending of the stalk, the two rings tilt toward each other (Fig. 7B). This strain is relieved when the trailing head (pink in Fig. 7C) detaches. Repriming of the linker position in the detached head swings it forward (Fig. 7D), although the detached head is likely to undergo considerable fluctuations, which are not depicted. Reattachment (Fig. 7E) is followed by the linker straightening in the new leading head (red in Fig. 7F), again tilting the two rings. Forward progress in this scheme is due both to the linker pulling toward the MT minus end and to the repriming motion of the detached head, which swings it forward (Fig. 7 C and D). Bhabha et al. (33) also postulated that repriming (reversal of the working stroke) in the detached stepping head biases the MTBD position in the forward minus-end direction. The attachment can occur at any of several of the tubulin subunits in its range. The rings tilt with each step regardless of whether the head labeled with the QR or its partner is stepping. Only when the labeled head steps, however, is there a translocation along the MT, thereby providing an explanation for approximately twice as many tilting motions as steps detected in the experiments.

Overall, our results support a flexible stalk model in which the amplitude of dynein ring and stalk rotational motions is fairly small once a step is complete and both dynein heads are bound to MT subunits. The duration of stepping is very short relative to the time spent in the two-head–bound configuration, causing our orientation measurements to be dominated by the angles of the dynein rings while both of them are bound. The orientation changes we do observe are consistent with hinge tilting and stalk bending caused by the intermolecular force in the connecting domains and linkers, which pull the trailing head forward and the leading head backward by 0.2–0.6 pN. Previous experimental evidence for rotation of the rings was derived solely from static images obtained by EM (30, 34), whereas we provide dynamic measurements collected in real time during stepping. Nevertheless, the results from the earlier EM studies are consistent with the rather small-angle changes we observed.

As suggested by our analyses, the motion that produces force or steps forward is not a stalk power stroke (Fig. 1A), but a consequence of straightening of the N-terminal linker region between the ring and the connecting dimerization domain (Figs. 1 and 7). In that case, the flexibility we detected in the MTBD hinge and the shaft of the stalk become important in enabling attachment to the next MT site. Limited flexibility may produce a bias of attachment in the minus-end direction because the MTBD is oriented relative to the stalk at the acute angle required for forward binding, but not rearward binding. Flexibility may lead to the observed variation in step size and direction while maintaining a bias toward the minus end, and it could play a role in dynein’s ability to navigate around obstacles on the MT (55). The amount of thermal wobbling that occurs during the “search” for this site is unknown; however, the stalk conformations sampled during our MD simulation suggest that a wide range of space may be explored. In myosin V, the predominant evidence (56, 57) is that the detached head swivels freely and sweeps out a large orientational space until it encounters the next actin subunit. High-speed angular measurements of the dynein ring and stalk will be required to elucidate the dynamics of thermal motions while dynein heads are detached during a step.

Materials and Methods

Dynein Expression and Purification.

Tail-truncated homodimeric and heterodimer dynein constructs were expressed in S. cerevisiae behind a galactose promoter using Kluyveromyces lactis URA3 replacement as a selectable maker for BioTag insertion. BioTags plus short linkers were inserted following A3666 in AAA5 and P4032 in AAA6. The tags were biotinylated in vivo by the endogenous yeast biotin ligase (38) (SI Appendix, Supplemental Methods). Constructs were purified using IgG affinity followed by tobacco etch virus protease cleavage. Both expression and purification methods have been published previously (21). Homodimeric constructs were dimerized using an N-terminal GST tag, and heterodimeric constructs were dimerized by cDNA oligonucleotides modified with benzylguanine-GLA-NHS SNAP ligand (New England Biolabs) at either the 5′ or 3′ end and covalently linked to an N-terminal SNAP tag (58) following the previously published protocol (23, 58).

PolTIRF Microscopy.

PolTIRF imaging was done on a Nikon TI-E TIRF microscope modified to allow direct laser illumination. Samples were illuminated with a 532-nm laser (CrystaLaser) through custom optics. Emission illumination was divided into polarized components using a home-built optical system (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). The fluorescence emission beam was split independent of polarization by a pellicle beamsplitter (ThorLabs). The two resulting beams were split into 0° and 90° or 45° and 135° analyzer components using a polarizing beamsplitter cube (ThorLabs) and a wire grid polarizer (ThorLabs), respectively. Polarized beam paths were directed onto a Photometrics Evolve EMCCD camera spatially separated so that the beams did not overlap.

Precise alignment of the emission analyzers was determined by placing a polarizer on the microscope stage at known orientations in 5° increments (ρ) and illuminating with unpolarized light. Intensity curves were fit with sin2(ρ) functions to determine the orientation, φ, of the analyzers from the fitted curve for each channel (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). Relative channel sensitivities were calibrated daily by imaging an isotropic solution of QRs to determine the relative intensity of an unpolarized sample in each channel (Iφ). A sample of water was imaged to determine the background (Bφ). Channel sensitivity (Cφ,) was calculated relative to the 0° channel: Cφ = (Iφ − Bφ)/(I0° − B0°). C0° = 1 by definition. Further details of polarization analysis are given in SI Appendix, Supplemental Methods.

Quantum nanorods sized 56.3 × 5.6 nm were synthesized in organic solvent and coated with NeutrAvidin as previously described (40).

Flow cells were constructed using a glass side and coverslip stuck together with double-sided tape (Scotch 3M) (59). Experiments were performed using individual MT tracks or sea urchin axoneme MT bundles. For single-MT experiments taxol-stabilized porcine MTs were attached to the coverslip surface using antitubulin antibody (Sigma anti–β-tubulin III antibody) in BRB80 solution [80 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (pH 6.8), 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 1.25 mg/mL casein] supplemented with 20 μM taxol (Cytoskeleton, Inc.). The antitubulin antibody bound nonspecifically to amino-silane–treated coverslips. Axonemes were bound nonspecifically to untreated glass coverslips in BRB80 buffer. Dynein was bound to MT in the absence of ATP in dynein lysis buffer [30 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 2 mM Mg-acetate, 1 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol, 1.25 mg/mL casein, 1 mM DTT, 20 μM taxol] at concentrations sufficiently low to resolve single molecules using GFP fluorescence. Dynein bound to MTs was labeled with excess NeutAvidin-coated QRs (∼20 nM) in dynein lysis buffer. Unbound QRs were thoroughly washed away with dynein lysis buffer. Imaging solution contained 30 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 2 mM Mg-acetate, 1 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol, 1.25 mg/mL casein, 10 mM DTT, 300 μg/mL glucose oxidase (Sigma), 120 μg/mL catalase (Sigma), 0.4% (wt/vol) glucose, 100 μM ATP (unless otherwise specified), and 20 μM taxol. Experiments on axonemes were performed using the same solutions but with taxol excluded.

MD Simulations.

An all-atom model comprising the dynein stalk and MTBD was prepared based on the crystal structure of human cytoplasmic dynein-2 in the primed conformation (PDB ID code 4RH7) (18). The model encompassed residues 2,847–3,234 and included two short α-helices connected via loops on either side of the stalk/ring interface in AAA4 to serve as positional anchors for the dynein fragment. Missing side chains in the stalk were added with SCWRL4 (60). Assessment using SOCKET 3.03 (61) confirmed that stalk residues CC1:2,918–2,977 and CC2:3,106–3,165 were packed according to the knobs-in-holes arrangement characteristic of a coiled-coil, with coil registration in the β+ state as appropriate for a primed dynein stalk (50). Protonation states and hydrogen coordinates were assigned to the model using the propKa 3.0 (62) option of PDB2PQR 2.0.0 (63) for an environmental pH of 7. The CIonize plug-in of VMD 1.9.2 (64) was used to place Na+ and Cl− ions around the model according to the local electrostatic potential. The model was then suspended in an 18.0 × 21.6 × 11.0-nm box of explicit water molecules with sufficient additional Na+ and Cl− ions to produce charge neutrality at 150 mM NaCl. The solvated dynein stalk/MTBD system (total of 253,000 atoms) was parameterized with the CHARMM36 (65, 66) force field and the CHARMM TIP3P water model (67). MD simulations were performed with NAMD 2.10 (68) as described in SI Appendix, Supplemental Methods, producing a final production trajectory totaling 3.3 μs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J. H. Lewis for assistance with software development, M. S. Woody for providing insight on angular measurement corrections and programming, and Dr. P. Purohit for helpful discussion regarding torsional stiffness. The MD simulations used in this work were made possible through the Blue Waters sustained-petascale computing project supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) Awards OCI-0725070 and ACI-1238993, the State of Illinois, and the “Computational Microscope” NSF Petascale Computing Resource Allocations Award ACI-1440026. This work was funded by NIH Grants P01-GM087253, R01-GM086352, and 9P41GM104601, and by NIH Training Grant T32-GM008275.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1620149114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Paschal BM, Vallee RB. Retrograde transport by the microtubule-associated protein MAP 1C. Nature. 1987;330:181–183. doi: 10.1038/330181a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts AJ, Kon T, Knight PJ, Sutoh K, Burgess SA. Functions and mechanics of dynein motor proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:713–726. doi: 10.1038/nrm3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cianfrocco MA, DeSantis ME, Leschziner AE, Reck-Peterson SL. Mechanism and regulation of cytoplasmic dynein. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2015;31:83–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100814-125438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maday S, Wallace KE, Holzbaur EL. Autophagosomes initiate distally and mature during transport toward the cell soma in primary neurons. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:407–417. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201106120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cottingham FR, Gheber L, Miller DL, Hoyt MA. Novel roles for saccharomyces cerevisiae mitotic spindle motors. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:335–350. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.2.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li YY, Yeh E, Hays T, Bloom K. Disruption of mitotic spindle orientation in a yeast dynein mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10096–10100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howell BJ, et al. Cytoplasmic dynein/dynactin drives kinetochore protein transport to the spindle poles and has a role in mitotic spindle checkpoint inactivation. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:1159–1172. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaMonte BH, et al. Disruption of dynein/dynactin inhibits axonal transport in motor neurons causing late-onset progressive degeneration. Neuron. 2002;34:715–727. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harms MB, et al. Mutations in the tail domain of DYNC1H1 cause dominant spinal muscular atrophy. Neurology. 2012;78:1714–1720. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182556c05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez-Carrera LA, Wirth B. Dominant spinal muscular atrophy is caused by mutations in BICD2, an important golgin protein. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:401. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy JR, Holzbaur EL. Cytoplasmic dynein/dynactin function and dysfunction in motor neurons. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2006;24:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maday S, Twelvetrees AE, Moughamian AJ, Holzbaur EL. Axonal transport: Cargo-specific mechanisms of motility and regulation. Neuron. 2014;84:292–309. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter AP, Cho C, Jin L, Vale RD. Crystal structure of the dynein motor domain. Science. 2011;331:1159–1165. doi: 10.1126/science.1202393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kon T, et al. The 2.8 Å crystal structure of the dynein motor domain. Nature. 2012;484:345–350. doi: 10.1038/nature10955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imamula K, Kon T, Ohkura R, Sutoh K. The coordination of cyclic microtubule association/dissociation and tail swing of cytoplasmic dynein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16134–16139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702370104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holzbaur EL, Johnson KA. ADP release is rate limiting in steady-state turnover by the dynein adenosinetriphosphatase. Biochemistry. 1989;28:5577–5585. doi: 10.1021/bi00439a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holzbaur EL, Johnson KA. Microtubules accelerate ADP release by dynein. Biochemistry. 1989;28:7010–7016. doi: 10.1021/bi00443a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt H, Zalyte R, Urnavicius L, Carter AP. Structure of human cytoplasmic dynein-2 primed for its power stroke. Nature. 2015;518:435–438. doi: 10.1038/nature14023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho C, Vale RD. The mechanism of dynein motility: Insight from crystal structures of the motor domain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts AJ, et al. ATP-driven remodeling of the linker domain in the dynein motor. Structure. 2012;20:1670–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reck-Peterson SL, et al. Single-molecule analysis of dynein processivity and stepping behavior. Cell. 2006;126:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeWitt MA, Chang AY, Combs PA, Yildiz A. Cytoplasmic dynein moves through uncoordinated stepping of the AAA+ ring domains. Science. 2012;335:221–225. doi: 10.1126/science.1215804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiu W, et al. Dynein achieves processive motion using both stochastic and coordinated stepping. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:193–200. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Z, Khan S, Sheetz MP. Single cytoplasmic dynein molecule movements: Characterization and comparison with kinesin. Biophys J. 1995;69:2011–2023. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80071-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yildiz A, Tomishige M, Vale RD, Selvin PR. Kinesin walks hand-over-hand. Science. 2004;303:676–678. doi: 10.1126/science.1093753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yildiz A, et al. Myosin V walks hand-over-hand: Single fluorophore imaging with 1.5-nm localization. Science. 2003;300:2061–2065. doi: 10.1126/science.1084398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun Y, et al. Single-molecule stepping and structural dynamics of myosin X. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:485–491. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forkey JN, Quinlan ME, Shaw MA, Corrie JE, Goldman YE. Three-dimensional structural dynamics of myosin V by single-molecule fluorescence polarization. Nature. 2003;422:399–404. doi: 10.1038/nature01529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mallik R, Carter BC, Lex SA, King SJ, Gross SP. Cytoplasmic dynein functions as a gear in response to load. Nature. 2004;427:649–652. doi: 10.1038/nature02293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imai H, et al. Direct observation shows superposition and large scale flexibility within cytoplasmic dynein motors moving along microtubules. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8179. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts AJ, et al. AAA+ Ring and linker swing mechanism in the dynein motor. Cell. 2009;136:485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burgess SA, Walker ML, Sakakibara H, Knight PJ, Oiwa K. Dynein structure and power stroke. Nature. 2003;421:715–718. doi: 10.1038/nature01377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhabha G, Johnson GT, Schroeder CM, Vale RD. How dynein moves along microtubules. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ueno H, Yasunaga T, Shingyoji C, Hirose K. Dynein pulls microtubules without rotating its stalk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19702–19707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808194105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin J, Okada K, Raytchev M, Smith MC, Nicastro D. Structural mechanism of the dynein power stroke. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:479–485. doi: 10.1038/ncb2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarlah A, Vilfan A. The winch model can explain both coordinated and uncoordinated stepping of cytoplasmic dynein. Biophys J. 2014;107:662–671. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burgess SA, Knight PJ. Is the dynein motor a winch? Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kulman JD, Satake M, Harris JE. A versatile system for site-specific enzymatic biotinylation and regulated expression of proteins in cultured mammalian cells. Protein Expr Purif. 2007;52:320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diroll B, Dadosh T, Koschitzky A, Goldman Y, Murray C. Interpreting the energy-dependent anisotropy of colloidal nanorods using ensemble and single-particle spectroscopy. J Phys Chem C Nanomat Interfaces. 2013;117:23928–23937. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lippert LG, et al. NeutrAvidin functionalization of CdSe/CdS quantum nanorods and quantification of biotin binding sites using biotin-4-fluorescein fluorescence quenching. Bioconjug Chem. 2016;27:562–568. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohmachi M, et al. Fluorescence microscopy for simultaneous observation of 3D orientation and movement and its application to quantum rod-tagged myosin V. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:5294–5298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118472109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu CY, Vanden Bout DA. Analysis of orientational dynamics of single fluorophore trajectories from three-angle polarization experiments. J Chem Phys. 2008;128:244501. doi: 10.1063/1.2937730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gennerich A, Carter AP, Reck-Peterson SL, Vale RD. Force-induced bidirectional stepping of cytoplasmic dynein. Cell. 2007;131:952–965. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beausang JF, Goldman YE, Nelson PC. Changepoint analysis for single-molecule polarized total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy experiments. Methods Enzymol. 2011;487:431–463. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381270-4.00015-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woody MS, Lewis JH, Greenberg MJ, Goldman YE, Ostap EM. MEMLET: An easy-to-use tool for data fitting and model comparison using maximum-likelihood estimation. Biophys J. 2016;111:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belyy V, Hendel NL, Chien A, Yildiz A. Cytoplasmic dynein transports cargos via load-sharing between the heads. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5544. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeWitt MA, Cypranowska CA, Cleary FB, Belyy V, Yildiz A. The AAA3 domain of cytoplasmic dynein acts as a switch to facilitate microtubule release. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:73–80. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cleary FB, et al. Tension on the linker gates the ATP-dependent release of dynein from microtubules. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4587. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nishikawa Y, et al. Structure of the entire stalk region of the Dynein motor domain. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:3232–3245. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kon T, et al. Helix sliding in the stalk coiled coil of dynein couples ATPase and microtubule binding. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:325–333. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolgemuth CW, Sun SX. Elasticity of alpha-helical coiled coils. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;97:248101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.248101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schmidt H, Gleave ES, Carter AP. Insights into dynein motor domain function from a 3.3-Å crystal structure. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:492–497. S1. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nicholas MP, et al. Control of cytoplasmic dynein force production and processivity by its C-terminal domain. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6206. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cho C, Reck-Peterson SL, Vale RD. Regulatory ATPase sites of cytoplasmic dynein affect processivity and force generation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25839–25845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802951200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dixit R, Ross JL, Goldman YE, Holzbaur EL. Differential regulation of dynein and kinesin motor proteins by tau. Science. 2008;319:1086–1089. doi: 10.1126/science.1152993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beausang JF, Shroder DY, Nelson PC, Goldman YE. Tilting and wobble of myosin V by high-speed single-molecule polarized fluorescence microscopy. Biophys J. 2013;104:1263–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dunn AR, Spudich JA. Dynamics of the unbound head during myosin V processive translocation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:246–248. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Keppler A, et al. A general method for the covalent labeling of fusion proteins with small molecules in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:86–89. doi: 10.1038/nbt765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beausang JF, Sun Y, Quinlan ME, Forkey JN, Goldman YE. Construction of flow chambers for polarized total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (polTIRFM) motility assays. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2012;2012:712–715. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot069385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krivov GG, Shapovalov MV, Dunbrack RL., Jr Improved prediction of protein side-chain conformations with SCWRL4. Proteins. 2009;77:778–795. doi: 10.1002/prot.22488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Walshaw J, Woolfson DN. Socket: A program for identifying and analysing coiled-coil motifs within protein structures. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:1427–1450. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Søndergaard CR, Olsson MH, Rostkowski M, Jensen JH. Improved treatment of ligands and coupling effects in empirical calculation and rationalization of pKa values. J Chem Theory Comput. 2011;7:2284–2295. doi: 10.1021/ct200133y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dolinsky TJ, et al. PDB2PQR: Expanding and upgrading automated preparation of biomolecular structures for molecular simulations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Web server issue):W522–W525. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.MacKerell AD, et al. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.MacKerell AD, Jr, Feig M, Brooks CL., 3rd Improved treatment of the protein backbone in empirical force fields. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:698–699. doi: 10.1021/ja036959e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jorgensen W, Chandrasekhar J, Madura J, Impey R, Klein M. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Phillips JC, et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.