Significance

The spatial and temporal control of complex loci’s expression is often effected by distant regulatory elements. At the IgH locus, class switch recombination (CSR) is preceded by transcription of the recombining genes and is controlled by the 3′ regulatory region (3′RR) in a stimulus-dependent manner. Why the 3′RR-mediated up-regulation of transcription is delayed to the mature B-cell stage is unknown. We show that an inducible CTCF insulator is involved in this process. Deletion of the insulator led to specific deregulation of transcription and CSR at earlier developmental stages. Insertion of a promoter downstream of the insulator led to its premature activation. Thus, the 3′RR has developmentally controlled potential to constitutively activate target promoters, but its activity is blocked by the insulator.

Keywords: B lymphocyte, IgH locus, insulator, germline transcription, class switch recombination

Abstract

Class switch recombination (CSR) plays an important role in adaptive immune response by enabling mature B cells to switch from IgM expression to the expression of downstream isotypes. CSR is preceded by inducible germline (GL) transcription of the constant genes and is controlled by the 3′ regulatory region (3′RR) in a stimulus-dependent manner. Why the 3′RR-mediated up-regulation of GL transcription is delayed to the mature B-cell stage is presently unknown. Here we show that mice devoid of an inducible CTCF binding element, located in the α constant gene, display a marked isotype-specific increase of GL transcription in developing and resting splenic B cells and altered CSR in activated B cells. Moreover, insertion of a GL promoter downstream of the CTCF insulator led to premature activation of the ectopic promoter. This study provides functional evidence that the 3′RR has a developmentally controlled potential to constitutively activate GL promoters but that this activity is delayed, at least in part, by the CTCF insulator, which borders a transcriptionally active domain established by the 3′RR in developing B cells.

Expression of complex loci is developmentally programmed or induced by specific stimuli and is often controlled by distant regulatory elements within relatively large chromatin domains. Transcriptional and architectural factors play an important role in the establishment and maintenance of these domains and facilitate long-range interactions between regulatory elements and target promoters (1, 2). The Ig heavy chain (IgH) locus is expressed in a lineage- and developmental stage-dependent manner. Various cis-acting elements including promoters, enhancers, and insulators control IgH locus expression and are engaged in multiple long-range interactions (3, 4).

Factors such as YY1, PAX5, IKAROS, CTCF, and Cohesin play important roles in various aspects of long-range events at the IgH locus, including V(D)J recombination, CSR, and promoter/enhancer and enhancer/enhancer interactions (3–6). Multiple CTCF binding elements (CBEs) were reported along the IgH locus. The majority of these CBEs lie within the variable domain (7), and two CBEs were identified within the VH-D intergenic region (7–9). At the 3′ end of the locus, ∼10 CBEs were identified downstream of the 3′RR and are thought to delineate the 3′ border of the IgH locus (10). More recently, a discrete CBE was identified within the α constant gene (11), but its role in vivo is presently unknown.

Upon antigen challenge, mature B cells can undergo CSR that allows B cells to change the heavy-chain constant domain of an IgM to IgG, IgE, or IgA. CSR to a particular isotype is induced by specific external stimuli, including antigens, mitogens, cytokines, and intercellular interactions. CSR is mediated by highly repetitive sequences called switch (S) sequences located upstream of the constant exons and is preceded by germline (GL) transcription of the S sequences that originates from GL promoters, named I promoters (12).

The 3′RR is composed of four enhancers—hs3a, hs1.2, hs3b, and hs4—and controls CSR by regulating GL transcription across S sequences. This entails a long-range control of multiple upstream I promoters (6, 13). Gene-targeted deletion of individual enhancers had no effect on GL transcription (14–16). In contrast, deletion of both hs3b and hs4 or of the whole 3′RR dramatically impaired GL transcription (e.g., refs. 17, 18). Thus, the prevailing notion is that the 3′RR-mediated activation of GL transcription preceding CSR is restricted to mature B cells (17–19). This leaves it unknown whether the 3′RR is programmed to activate GL promoters of the IgH constant domain only after activation of B cells or whether it can do so in a developmentally regulated, constitutive manner before induction.

Here we show that the 3′RR has the potential to prematurely activate upstream GL promoters in developing and resting B cells, though in an isotype-restricted manner. This activity is delayed by an inducible CTCF insulator that borders an active domain in which the 3′RR displays a bidirectional transcriptional activity.

Results

Specific Increase of Sγ3, Sγ2b, and Sγ2a GL Transcription in 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ Resting B Cells.

A DNase I hypersensitive site (hs) was detected within the Cα3–Cαmb intervening sequence of the mouse α constant gene (20) and was recently shown to bind CTCF in resting, but not in activated, splenic B cells (11). The CBE is conserved in the human α1 and α2 constant genes (Fig. S1). To elucidate the function of this element in vivo, the Cα3–Cαmb intervening sequence encompassing the hs and the CBE (hereafter called 5′hs1RI) was deleted by gene targeting (Fig. 1A). The extent of the deletion was checked by sequencing the relevant region in genomic DNA of 5′hs1RI-deficient splenic B cells and by chromatin immunoprecipitation assays, which confirmed the lack of binding of CTCF and SMC1 and SMC3 subunits of the Cohesin complex in 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ B cells (Fig. S2 A–C and Table S1).

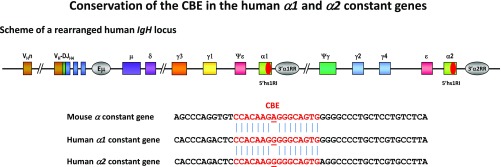

Fig. S1.

The CBE within the Cα3-αmb intron is highly conserved between the mouse α and the human α1 and α2 constant genes. Partial sequence alignment between the mouse and human sequences containing the CBE (in red). The mouse and the human CTCF binding motifs differ by only one nucleotide (underlined).

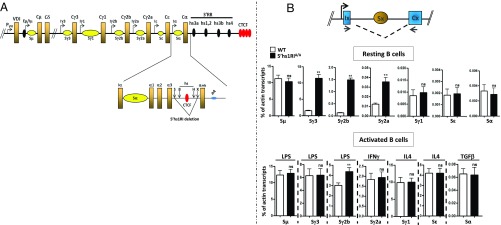

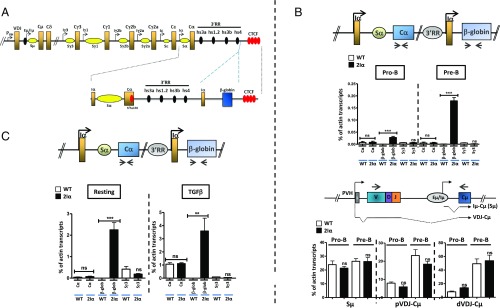

Fig. 1.

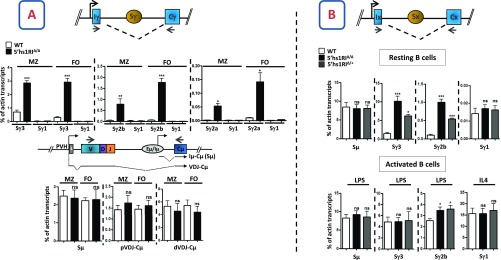

Specific increase of Sγ3, Sγ2b, and Sγ2a GL transcripts in 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ splenic B cells. (A) Deletion of 5′hs1RI. (Top) Scheme of a rearranged IgH locus. The α constant gene is magnified in the scheme below which also highlights the relative position of the hs and the CBE targeted by 5′hs1RI deletion. Only 4 out of ∼10 CTCF sites are shown downstream of the 3′RR. B, BstEII; H, HincII; S, SphI; X, XbaI. pA, polyadenylation sites of the membrane form of α HC transcript. (B) Analysis of GL transcription in resting and activated B cells. (Top) A constant gene; x stands for any isotype. The relative position of the primers used to detect spliced GL transcripts is indicated. Total RNAs were prepared from purified CD43− WT and 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ splenic B cells or at day 2 poststimulation, reverse-transcribed, and the indicated GL transcript levels quantified by qRT-PCR (n = 4). **P < 0.01; ns, not significant.

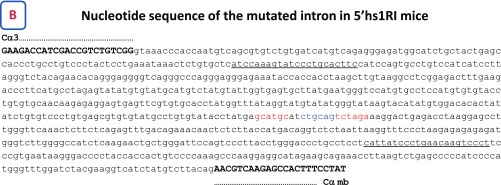

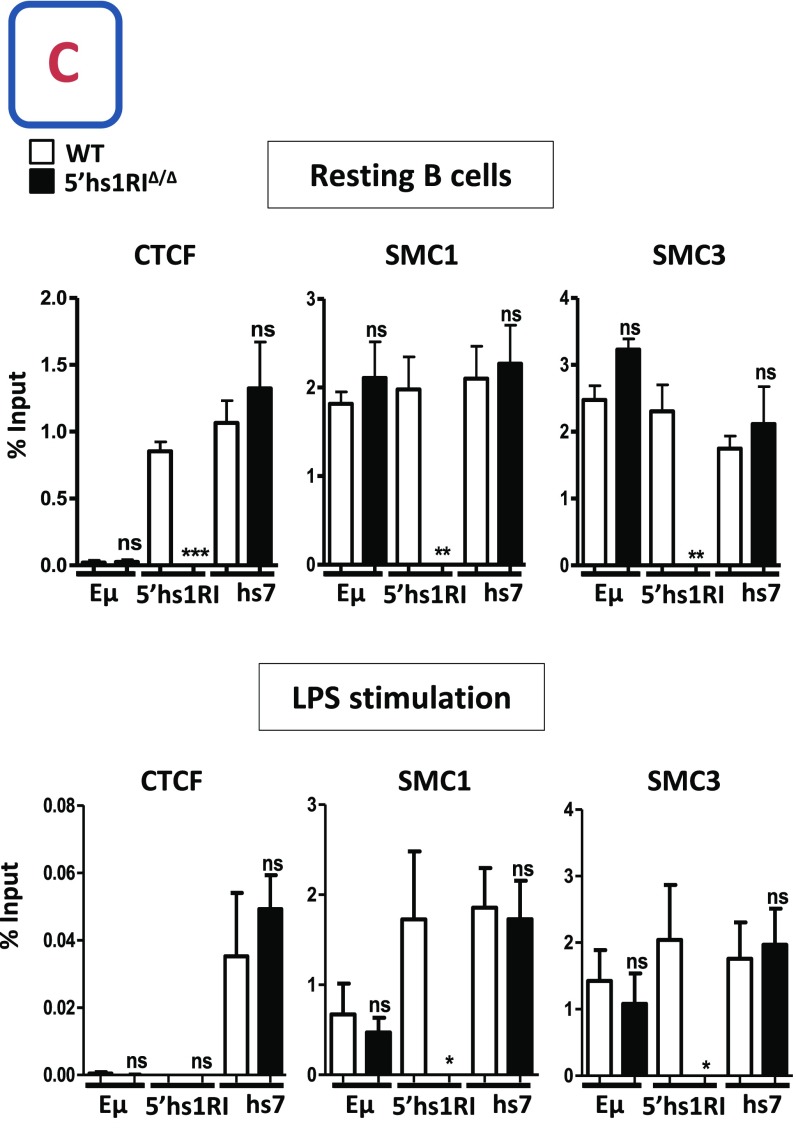

Fig. S2.

Generation of 5′hs1RI mutant mice. (A) Deletion of the 5′hs1RI element. Upper shows a rearranged IgH locus. The large BamHI fragment encompassing the α constant gene, the 5′hs1RI element, and the hs3a enhancer is highlighted. In the 5′ arm of the targeting vector, the intervening region containing the 5′hs1RI element was replaced by a PstI site. αm stands for the mutated version of the α membrane exon (α mb) in which the terminal tyrosine was replaced by Glycine. Left shows an example of PCR screening on genomic DNA from the tail of 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ mice. B, BamHI; N, NotI; P, PstI; R, EcoRI; S, SphI; Sl, SalI; X, XbaI. Only the pertinent sites are shown (not to scale). (B) Nucleotide sequence of the mutant Cα3-αmb intervening region. The nucleotide sequence downstream of the Cα3 exon encompassing the 5′hs1RI deletion was determined after PCR on genomic DNA from 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ splenic B cells. The deleted sequence between SphI and XbaI sites (in red) was replaced by a PstI site (in blue). The sequences of the 3′ part of the Cα3 exon and the 5′ part of the αmb exon are shown in bold capital letters and the remaining intron sequences by lowercase letters. The sequences of the primers used for PCR screening are underlined and listed in Table S1. (C) Lack of CTCF and Cohesin binding to the deleted 5′hs1RI. ChIP assays were performed on chromatin from resting B cells of the indicated genotypes. The antibodies used and the targeted sequences (Eµ enhancer, 5′hs1RI, and hs7 downstream of the 3′RR) are indicated (n = 3). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

Table S1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer transcription analysis | Sequence | Tm °C |

| GL transcription | ||

| Iµ-Fw | CTCTGGCCCTGCTTATTGTTG | 60 |

| Cµ-Rev | GAAGACATTTGGGAAGGACTGACT | 60 |

| Iγ3-Fw | TGGGCAAGTGGATCTGAACAC | 60 |

| Cγ3-Rev | CTCAGGGAAGTAGCCTTTGACA | 60 |

| Iγ1-Fw | GGCCCTTCCAGATCTTTGAG | 60 |

| Cγ1-Rev | GGATCCAGAGTTCCAGGTCAC | 60 |

| Iγ2b-Fw | CACTGGGCCTTTCCAGAACTA | 60 |

| Cγ2b-Rev | CACTGAGCTGCTCATAGTGTA | 60 |

| Iγ2a-Fw3 | GAAGGTTCATCGGGAAAGGC | 60 |

| Cγ2a-Rev1 | GCCAGTTGTATCTCCACACACAG | 60 |

| Iε-Fw3 | ACTAGAGATTCACAACGCCTGGGA | 60 |

| Cε-R3 | AGGGTCATGGAAGCAGTGCCTTTA | 60 |

| Iα-ST-Fw | GGGTGACTCAGGCTGTTGTGG | 60 |

| CαR | GAGCTGGTGGGAGTGTCAGTG | 60 |

| Iα-H2-F1 | CCTGGGAGCCCTCCACTGGG | 60 |

| Iα-H2-R1 | CGCCACTGTTCCAGCGCTCA | 60 |

| Hβglob-F2 | TGCTGGTCTGTGTGCTGGC | 60 |

| Hβglob-R3 | GACTTAGGGAACAAAGGAACC | 60 |

| 3′RR eRNAs | ||

| HS3a-F | GGCTCCTGTACTAGATCGATGG | 62 |

| HS3a-R | ACTGTCCCAGTTGCAGCCC | 62 |

| HS1.2–3′F | GGGTGGCTCAACACCCCAGG | 62 |

| HS1.2–3′R | TGGGCTGAGGCAGGCCAAGA | 62 |

| HS3b-F1 | TGAGGGCCAGGGCCCAATGA | 62 |

| HS3b-R1 | GGATCTCGGTCCTGGTAACTGGCT | 62 |

| HS4-F1 | CAGGCAAGGTGATGTGGATGAGAG | 64 |

| HS4-R2 | AGGTCTACACAGGGGCTCTG | 64 |

| VDJ-Cµ transcription | ||

| VHJ558-Fw | GCGAAGCTTARGCCTGGGRCTTCAGTGAAG | 60 |

| VH7183-Fw | GCGAAGCTTGTGGAGTCTGGGGGAGGCTTA | 60 |

| Cµ-Rev | GAAGACATTTGGGAAGGACTGACT | 60 |

| Normalization | ||

| Actin 4-Fw | TACCTCATGAAGATCCTGA | 60 |

| Actin 5-Rev | TTCATGGATGCCACAGGAT | 60 |

| Gapdh-Fw | GGTGAAGGTCGGTGTGAACG | 60 |

| Gapdh-Rev | CTCGCTCCTGGAAGATGGTG | 60 |

| mYWHAZ-F2 | AGATGAAGCAGAAGCAGGAGAAG | 60 |

| mYWHAZ-R | CAGCATGGATGACAAATGGTCAC | 60 |

| ChIP | ||

| CTCF–Sp1-F | ACACAAAGTTCTACAACCAGGTA | 61 |

| CTCF–Sp1-R | CCTTTACTCCACTCTTGCTCTG | 61 |

| BKB Eµ-F | TGGCAGGAAGCAGGTCAT | 60 |

| BKB Eµ-R | GGACTTTCGGTTTGGTGG | 60 |

| BKB34-F | AATACGTTCCTAGGGCCTAACGATACT | 60 |

| BKB34-R | TGGAGACGCCACAGGTGTATC | 60 |

| qDC-PCR | ||

| Sµ–Sγ CSR | ||

| SµR | GACCAATAATCAGAGGGAAGAATAATAG | 58 |

| Cγ3qPCR | AGCCATCACAATAACCATCTTCCTG | 58 |

| Sγ1up1-Fw | TGAGTAGAAGCAGGGGAGC | 58 |

| Sγ2bup1-Fw | GAAAAAGGGATGGGAAAGCACTC | 58 |

| Sγ2aup3-Fw | GGAAAGGGATGGGAAAGGAC | 58 |

| Normalization | ||

| AcRqPCR-Fw | GCACACAAACCACTAAACTACTCACTAT | 58 |

| AcRqPCR-R | TGGTGATAGAGGCAGGAAGA | 58 |

| PCR screening of 5′hs1RI mice | ||

| CaLCR-F | ATCCAAAGTATCCCTGCACTTC | 57 |

| CaLCR-R3 | AGGGACTTGTTCAGGGATAATG | 57 |

The finding that CTCF bound 5′hs1RI in resting but not in activated B cells (ref. 11 and Fig. S2C) led us to hypothesize that the 5′hs1RI may act as a CTCF insulator to the 3′RR in resting B cells, in which case deletion of the 5′hs1RI element would result in premature activation of upstream GL promoters before B-cell activation. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed GL transcription in resting B cells. Total RNAs from CD43− sorted splenic B cells derived from WT and 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ littermates were extracted, reverse-transcribed, and analyzed by qPCR. With the exception of the constitutive Sµ GL transcription, derived from Eµ/Iµ promoter, GL transcription across the downstream S regions is barely detectable for most isotypes in unstimulated splenic B cells but is induced upon appropriate stimulation (17, 18, 21).

Strikingly, Sγ3 GL transcripts were markedly up-regulated in unstimulated 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ splenic B cells compared with WT controls. There was also a significant increase of Sγ2b and Sγ2a GL transcript levels, though clearly less marked for Sγ2a transcripts. In contrast, no such up-regulation was detected for Sγ1, Sε, and Sα GL transcripts whose levels were extremely low (Fig. 1B, Top). In 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ LPS-activated B cells, Sγ3 transcript levels were comparable to their WT counterparts, and those of Sγ2b were slightly higher than WT levels. The transcript levels of the other isotypes were comparable between mutants and WT controls upon appropriate stimulation (IFNγ stimulation for Sγ2a, IL4 stimulation for Sγ1 and Sε, and TGFβ stimulation for Sα) (Fig. 1B, Bottom). These findings were obtained regardless of the origin of the WT and 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ mice—that is, littermates or from different litters. We conclude that in resting B cells, the 5′hs1RI deletion has a major effect on Sγ3, Sγ2b, and Sγ2a GL transcription specifically.

We then investigated whether up-regulation of Sγ3, Sγ2b, and Sγ2a GL transcription in 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ resting B cells correlated with a perturbed expression pattern in marginal zone (MZ) versus follicular (FO) B cells. Although the levels of Sγ1, Sε, and Sα were extremely low and did not vary, Sγ3 transcript levels were higher in both MZ and FO mutant B cells. Sγ2b and Sγ2a transcript levels were also increased in both populations, though the increase was higher in the FO B-cell population (Fig. S3A). Thus, 5′hs1RI deletion leads to increased levels of Sγ3, Sγ2b, and Sγ2a transcripts in both MZ and FO B cells.

Fig. S3.

(A) GL transcription in MZ and FO B cells of 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ mice. Total RNAs were prepared from sorted MZ B cells (B220+CD21highCD23−) and FO B cells (B220+CD21−CD23high), reverse-transcribed, and the indicated transcript levels quantified by qRT-PCR (n = 4). dVDJ-Cµ, distal VHJ558-containing µ transcripts; pVDJ-Cµ, proximal VH7183-containing µ transcripts. (B) GL transcription in heterozygous mice. Total RNAs were prepared from CD43− WT, heterozygous, and homozygous splenic B cells and at day 2 poststimulation, and the indicated GL transcript levels were quantified by qRT-PCR (n = 4). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

To investigate whether 5′hs1RI deletion affects GL transcription in trans, we quantified GL transcript levels in unstimulated WT, heterozygous, and homozygous splenic B cells from littermates. We focused on Sγ3 and Sγ2b as their levels were higher in mutant B cells. The levels of Sγ3 and Sγ2b GL transcripts in heterozygous mice were roughly half those in homozygous mice (Fig. S3B). Upon appropriate stimulation and in agreement with the biallelic nature of GL transcription (22), GL transcript levels were comparable regardless of the genotype (Fig. S3B), indicating that in the absence of 5′hs1RI, Sγ3 and Sγ2b GL transcription is likely up-regulated in cis. We conclude that 5′hs1RI mainly acts in cis.

The 5′hs1RI Deletion Exerts Its Effect Without Altering the 3′RR eRNAs Levels.

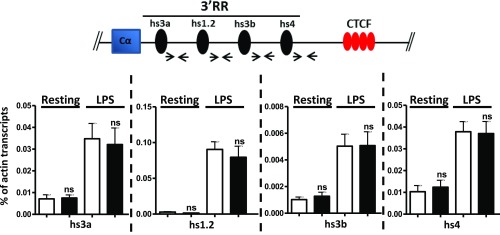

Although their levels are low, the 3′RR transcripts [3′RR enhancer RNAs (eRNAs)] can readily be detected upon stimulation of splenic B cells and correlate with the 3′RR activity in activated B cells (23, 24). Additionally, recent work involved hs4 eRNA in long-range interactions with a far downstream non-Ig sequence (25). Because the deletion of 5′hs1RI may have impacted the long-range interactions of the 3′RR and potentially altered its activity, it was important to check the effect of the mutation on the 3′RR eRNA levels.

To this end, hs3a, hs1-2, hs3b, and hs4 eRNA levels were quantified by qRT-PCR. The 3′RR eRNA levels were at the background levels in WT and 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ pro-B cells. In pre-B cells, only low levels of hs4 eRNAs were detected in both genotypes. Importantly, although still low in unstimulated splenic B cells, the 3′RR eRNA levels did not vary in mutant B cells compared with their WT counterparts. Similarly, we found no difference between the 3′RR eRNA levels in WT and 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ-activated B cells (Fig. S4).

Fig. S4.

The 5′hs1RI deletion exerts its effect without altering the 3′RR eRNAs levels. (Top) Relative position of the primers used downstream of each 3′RR enhancer. Total RNAs were prepared at day 2 post-LPS stimulation, and the indicated eRNAs levels were quantified by qRT-PCR (n = 4). ns, not significant.

Thus, the 5′hs1RI deletion did not alter the 3′RR eRNA levels. Therefore, the effect of the mutation on Sγ3, Sγ2b, and Sγ2a GL transcription cannot be ascribed to deregulated expression of the known 3′RR eRNAs.

The 5′hs1RI Deletion Differentially Affects CSR.

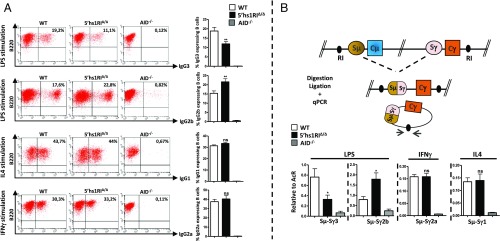

The specific increase of Sγ3, Sγ2b, and Sγ2a transcript levels in resting B cells and those of Sγ2b in LPS-activated splenic B cells led us to investigate the effect of 5′hs1RI deletion on CSR. To this end, sorted CD43− splenic B cells were induced to switch, and surface expression of IgGs was monitored by FACS. Surprisingly, IgG3 surface expression was reduced, whereas that of IgG2b was increased. In contrast, surface expression of IgG2a and of IgG1 was unaltered (Fig. 2A). These findings were confirmed by quantifying the levels of postswitch transcripts by qRT-PCR (Fig. S5A) and of CSR events at the genomic level by quantitative digestion/circularization-PCR (qDC-PCR) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

The 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ deletion affects CSR. (A) CD43− sorted splenic B cells with the indicated genotypes were induced to switch to IgG3 and IgG2b (LPS stimulation), to IgG1 (IL4 stimulation), or to IgG2a (IFNγ stimulation). At day 4.5 poststimulation, the cells were stained with the indicated antibodies. The statistical data are shown at Right (n = 7). (B) Genomic DNAs were purified from activated splenic B cells (day 4.5) and assayed by qDC-PCR (Top; RI, EcoRI). Quantification of CSR events was performed by qPCR (n = 7). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ns, not significant.

Fig. S5.

The 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ deletion affects CSR in vivo and in vitro. (A) Total RNAs were prepared from activated splenic B cells (day 4.5), reverse-transcribed, and postswitch (Iµ-Cγ, γ representing γ3, γ2b, γ2a, or γ1) GL transcript levels quantified by qRT-PCR (n = 7). (B) Six-week-old mice were immunized intraperitoneally with TNP-Ficoll or PBS at days 0 and 14. For each immunization, six WT (red) and six mutant (black) mice were used. Serum was collected at the indicated days, and IgG titers were quantified by ELISA. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

Because IgG3, IgG2b, and IgG2a production can be induced in a T-independent manner, we quantified their serum levels by ELISA at various time points after i.p. immunization with TNP-Ficoll. At day 28 postimmunization, IgG3 titers were significantly reduced, whereas those of IgG2a were increased. For IgG2b, although the increase was not statistically significant, the trend was consistently toward increased levels in mutant mice (Fig. S5B). Thus, at least with regard to TI type II antigens and within the limits of our time course, 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ mice display a defective IgG3-mediated and an enhanced IgG2a- and IgG2b-mediated humoral response.

The above data lead us to conclude that 5′hs1RI contributes to the regulation of CSR to IgG3, IgG2b, and IgG2a in vivo and in vitro.

Differential Up-Regulation of GL Transcription and Alteration of CSR in 5′hs1RI-Deleted Mice Start in Developing B Cells.

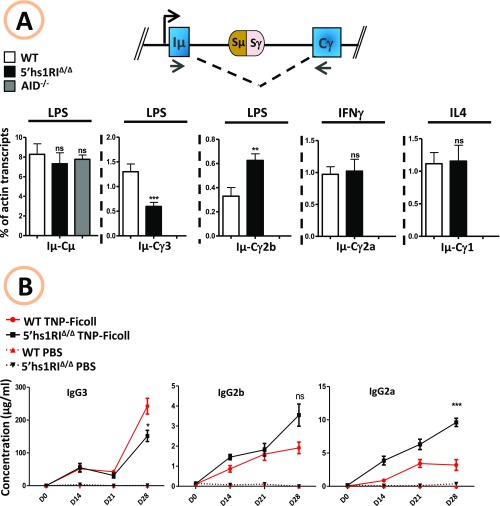

The striking increase of Sγ3, Sγ2b, and Sγ2a transcript levels in unstimulated 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ splenic B cells led us to ask at which developmental stage this up-regulation was initiated. To this end, Sγ3, Sγ2b, and Sγ2a GL transcripts were quantified in sorted pro–B-cell and pre–B-cell populations from WT and 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ littermates. Sγ3 GL transcripts started to be detected at the pro–B-cell stage onwards, whereas Sγ2b GL transcripts were readily detectable in pre-B cells. In contrast, Sγ2a GL transcripts were at the background level in pro-B and pre-B cells (Fig. 3A, Top). The mutation targeted Sγ3 and Sγ2b GL transcripts specifically (Fig. 3A, Bottom).

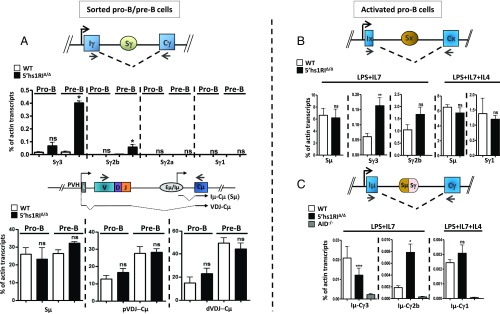

Fig. 3.

The effect of 5′hs1RI deletion on GL transcription and CSR starts in developing B cells. (A) Total RNAs were prepared from sorted WT and 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ pro-B (B220+IgM−CD43high) and pre-B (B220+IgM−CD43low) cells, and GL transcript levels were quantified by qRT-PCR for Sγ GL transcripts (Top) and for Sµ GL transcripts (Iµ-Cµ) and µ HC transcripts (pVDJ-Cµ and dVDJ-Cµ) (Bottom) (n = 3, each experiment starting with a pool of at least three mice per genotype). dVDJ-Cµ, distal VHJ558-containing µ transcripts; pVDJ-Cµ, proximal VH7183-containing µ transcripts. (B and C) Sorted pro-B cells were grown for 4 d in the presence of IL7 and activated with LPS or LPS+IL4. At day 2 poststimulation, total RNAs were prepared and subjected to qRT-PCR as in A. Preswitch (B) and postswitch (C) GL transcript levels were quantified for the indicated isotypes (n = 3 for each set of GL transcripts). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

Accordingly, when purified pro-B cells were grown in vitro and stimulated in the presence of LPS, Sγ3 transcript levels clearly increased. The increase of Sγ2b transcript levels was not statistically significant, although the trend was consistently toward the increase in activated mutant pro-B cells. In contrast, Sγ1 transcript levels were unaltered (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, by using postswitch transcript levels as a measure of the efficiency of CSR, we found a defective CSR to Sγ3 and an increased CSR to Sγ2b in LPS-activated mutant pro-B cells. In contrast, no alteration of CSR to Sγ1 was detected upon IL4 stimulation (Fig. 3C). Thus, although CSR frequency in activated pro-B cells is manifold lower than in activated splenic B cells, the altered pattern of CSR to Sγ3 and Sγ2b is strikingly similar.

We conclude that the specific effect of 5′hs1RI deletion on Sγ3 and Sγ2b GL transcription starts in developing B cells already.

Premature Activation of a Duplicated Iα GL Promoter Downstream of the 3′RR.

Analysis of GL transcription in 5′hs1RI-deleted mice led us to provisionally conclude that the 3′RR had the potential to activate GL promoters in developing B cells already but (i) that this activity was insulated from upstream GL promoters by 5′hs1RI and (ii) that in the absence of the insulator, the 3′RR activity was prematurely targeted toward Iγ3, Iγ2b, and Iγ2a GL promoters specifically. One implication of these notions is that constitutive activity is an inherent feature of the 3′RR within the chromatin domain downstream of 5′hs1RI, from pro–B-cell stage up to resting splenic B cells. If so, insertion of any GL promoter downstream of 5′hs1RI would lead to premature activation of that promoter. To provide a functional support to this notion, we generated a mouse line in which we inserted a chimeric transcription unit driven by Iα GL promoter, downstream of the 3′RR (hereafter called 2Iα mice; Fig. 4A and Fig. S6). All analyses were performed on homozygous 2Iα mice.

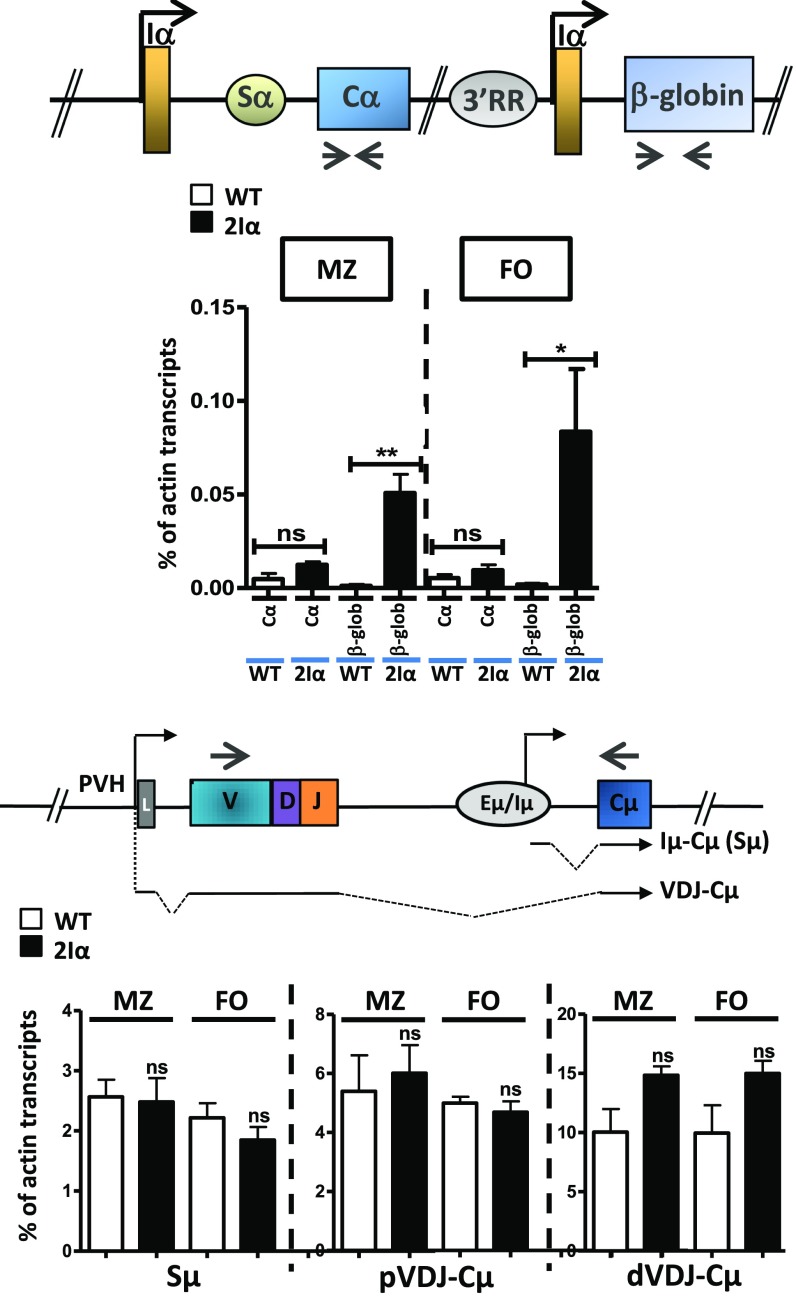

Fig. 4.

Duplication of Iα GL promoter downstream of the 3′RR. (A) Scheme of a rearranged IgH locus. The inserted transcription unit is composed of the mouse Iα GL promoter followed by the terminal intron and exon of the human β-globin gene. The localization of 5′hs1RI within the α constant gene is indicated. (B) For the endogenous α constant gene and for the ectopic transcription unit, the primers were designed within Cα1 exon (Cα transcripts) and the β-globin exon (β-glob transcripts), respectively. Total RNAs were prepared from sorted pro-B and pre-B cells, and the indicated transcript levels were quantified by qRT-PCR (n = 4). (C) Total RNAs were prepared from CD43− splenic B cells and at day 2 post-TGFβ stimulation, and the endogenous Cα and the β-globin transcript levels were quantified by qPCR (n = 4). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

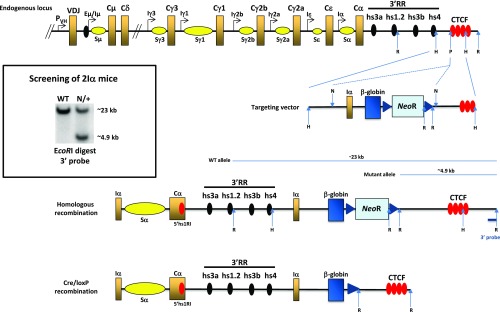

Fig. S6.

Insertion of an ectopic transcriptional unit downstream of the 3′RR. Genomic DNA from the tails of 2Iα mice was extracted, digested with EcoRI, and assayed by Southern blot. The external 3′ probe is a cloned 0.6 kb HincII–EcoRI fragment. Only the pertinent restriction sites are shown. H, HindIII; N, NotI; P, PmlI; R, EcoRI. Not all CTCF sites are shown. The relative position of the 5′hs1RI within the α constant gene is indicated by a red oval.

To determine at which developmental stage the ectopic Iα GL promoter was activated, we quantified β-globin transcripts in pro-B, pre-B, MZ, and FO B cells and TGFβ-activated splenic B cells. The endogenous Iα-derived GL transcripts were readily detected in TGFβ-activated B cells essentially (Fig. 4 B and C and Fig. S7). Interestingly, upon TGFβ stimulation, GL transcripts derived from the endogenous Iα GL promoter of 2Iα mice were just as abundant as those derived from the endogenous Iα GL promoter of WT mice (Fig. 4C), indicating that the ectopic Iα GL promoter did not interfere with the activity of its endogenous counterpart. Importantly, the transcripts derived from the ectopic Iα GL promoter started to be detected in pro-B cells (Fig. 4B) and their levels increased in resting B cells (Fig. 4C).

Fig. S7.

GL transcription in MZ and FO B cells of 2Iα mice. Total RNAs were prepared from sorted MZ B cells (B220+CD21highCD23−) and FO B cells (B220+CD21−CD23high), reverse-transcribed, and the indicated transcript levels quantified by qRT-PCR (n = 4). dVDJ-Cµ, distal VHJ558-containing µ transcripts; pVDJ-Cµ, proximal VH7183-containing µ transcripts. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ns, not significant.

We conclude that insertion of the ectopic Iα GL promoter downstream of the 3′RR results in premature activation of the promoter.

Discussion

The present study reveals an important role for the 5′hs1RI element in IgH locus expression along B-cell development. The 5′hs1RI emerges as a cis-acting regulatory element that acts, at least in part, as an inducible CTCF insulator. One function of 5′hs1RI is to block premature activation of specific GL promoters—that is, Iγ3, Iγ2b, and Iγ2a GL promoters—before B-cell activation, strongly suggesting that 5′hs1RI is somehow involved in the transcriptional silencing of these promoters. This developmentally controlled, isotype-restricted targeting displayed by 5′hs1RI suggests specific mechanisms and implies that silencing of Iγ1, Iε, and Iα likely involves other mechanisms/elements.

Interestingly, the 5′hs1RI deletion did not alter the 3′RR eRNA levels. Additionally, Sγ3 transcript levels were increased in 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ resting B cells in the absence of any obvious increase of 3′RR eRNA levels, suggesting that up-regulation of 3′RR eRNAs was not absolutely required for the 3′RR to exert its constitutive, isotype-specific, activity. It could be that the 3′RR eRNAs are not required for the constitutive activity of the 3′RR and/or for the targeting of GL promoters, before B-cell activation and 3′RR induction. In support of this interpretation, Iγ3 GL promoter in 5′hsRIΔ/Δ-deleted mice and ectopic Iα GL promoter in 2Iα mice were activated at the pro–B-cell stage at which no 3′RR eRNAs could be detected. Alternatively, low levels of eRNAs may be sufficient for the opening of enhancers’ chromatin and the triggering of the 3′RR enhancing activity. In pro-B cells specifically, this would imply that very low levels of hs4 eRNAs would be sufficient to trigger the 3′RR enhancing activity.

Significantly, 5′hs1RI contributes to the regulation of CSR in a relatively complex way. Although increased CSR to IgG2b correlated with increased Sγ2b GL transcription, CSR to IgG3 was defective despite seemingly abundant Sγ3 GL transcription. A likely mechanism could be promoter interference (26, 27) incurred by the downstream, more active Iγ2b GL promoter, which may explain the drop of Sγ3 transcripts to WT levels upon LPS stimulation and the subsequent decrease of CSR to IgG3.

Interestingly, the CBE at the 5′hs1RI element and CBE2 at the IGCR1 share identical sequence (TCCACAAGAGGGCAG) and therefore the same orientation. Building on previous findings on the sequence convergence of interacting CTCF sites (28) and on the interactions engaging IGCR1 CBE2 and the Super Insulator downstream of the IgH locus (29, 30), it is plausible that the 5′hs1RI CBE interacts with the CBEs downstream of the IgH locus. This may indirectly support the notion that the 5′hs1RI CBE somehow contributes to the insulation of the 3′RR from upstream GL promoters before B-cell activation.

Previous chromosome conformation capture assays on unstimulated splenic B cells (31) or on a pro–B-cell line (32) detected relatively high cross-linking frequencies between the 3′RR and Iγ3 GL promoter and between the 3′RR and Iγ2b GL promoter, suggesting some proximity between the 3′RR and these promoters before B-cell activation. Our study suggests that 5′hs1RI somehow precludes premature 3′RR-mediated activation of Iγ3 and Iγ2b (and to some extent Iγ2a) GL promoters in pro-B cells up to resting splenic B cells. The finding that 5′hs1RI-bound CTCF was evicted upon B-cell activation suggests that CTCF could be involved in this process. Clearly, additional mutational studies are needed to clarify this issue. In immunological terms, it should be noted that MZ B cells mainly switch to IgG3 but can also switch to IgG2b and IgG2a, in response to T-cell–independent antigens (33). We speculate that the developmentally programmed 3′RR/Iγ3 and 3′RR/Iγ2b close-by positioning evolved, at least in part, to enable rapid IgG3 and IgG2b responses by MZ B cells.

Our initial working hypothesis was that deletion of 5′hs1RI would lead to premature activation of all upstream GL promoters with the possible exception of Iγ1 GL promoter (e.g., refs. 17, 18, 21). Strikingly, only Iγ3, Iγ2b, and Iγ2a GL promoters were targeted in the absence of 5′hs1RI. Notwithstanding this isotype restriction, it is clear that the 3′RR displays a constitutive transcriptional enhancer activity and that it already has the potential to activate upstream GL promoters of the IgH constant domain before antigenic induction. A reasonable inference is that the 3′RR could activate any GL promoter brought under its control within the transcriptionally active domain established by the 3′RR downstream of the 5′hs1RI element before B-cell activation. The premature activation of the ectopic Iα GL promoter provided a functional support to this notion. The downstream CBEs that mark the 3′ end of the IgH locus (10) likely delineate the 3′ border of this active domain. Our data with 2Iα mice suggest, but do not prove, that the 3′RR has a bidirectional activity, just that the effect on further downstream sequences is likely blocked by the 3′CBEs. However, we do not infer that the mechanisms of action of the 3′RR on upstream and downstream promoters (relatively to the 3′RR) are necessarily the same.

Materials and Methods

Mice, Antibodies, and Cytokines.

The generation of the mutant mice, the antibodies, and the cytokines used are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Mice and Ethical Guidelines.

The WT, heterozygous, and homozygous mutants were of 129Sv background. The experiments on mice have been carried out according to the CNRS ethical guidelines and were approved by the Regional Ethical Committee.

Cell Sorting and Splenic B-Cell Activation.

Single cell suspensions from the bone marrows or spleens were obtained by standard techniques. Pro-B cells were sorted as IgM−B220+CD43high and pre-B cells as IgM−B220+CD43low. Splenic B cells were negatively sorted by using CD43-magnetic microbeads and LS columns (Miltenyi). Culture conditions used to induce GL transcription and CSR in pro-B cells and splenic B cells and FACS protocol are detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

qRT-PCR.

Total RNAs were prepared from sorted pro-B cells, pre-B cells, MZ B cells, FO B cells, resting splenic B cells, and B cells at day 2 or 4.5 poststimulation. Total RNAs were reverse-transcribed (Invitrogen) and subjected to qPCR using Sso Fast Eva Green (BioRad). Actin, Gapdh, and Ywhaz transcripts were used for normalization and yielded similar results. Only normalization by Actin transcripts is shown. (–RT) controls were included in all of the experiments. The primers used are listed in SI Materials and Methods.

qDC-PCR.

Genomic DNAs were purified from WT, 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ, and AID−/− splenic B cells at day 4.5 poststimulation. The EcoRI digestion and circularization steps were as described (32). Ligation products were subjected to qPCR. Acetylcholine receptor gene was used for normalization.

Statistical Analysis.

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (GraphPad Prism), and overall differences between values from WT and mutant mice were evaluated by an ANOVA parametric test with Newman–Keuls posttest and t test with Mann–Whitney posttest. The difference between means is significant if P < 0.05 (*), very significant if P < 0.01 (**), and extremely significant if P < 0.001 (***).

SI Materials and Methods

Generation of 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ Mice.

The backbone of the targeting construct was a modified pBluescript II KS− (Stratagene), and the 5′ arm (∼2.2 kb XbaI–NotI modified fragment) contained the last Cα exons and the deleted membrane exon intronic sequence. In this intron, the ∼1.6 kb sequence containing a DNase I hs and a CTCF binding site, both located between the SphI and XbaI sites, was deleted. A PCR-amplified sequence containing a mutated version of the membrane exon (the terminal tyrosine was replaced by glycine) was appended downstream of the SphI site bringing in a BamHI site and a NotI site at the 3′ part of the 5′ arm. The 3′ arm (∼2.6 kb EcoRI–BamHI fragment) was modified into a NotI–SalI fragment and ligated to the 5′ arm-containing vector. The ∼1.3 kb floxed NeoR cassette was then inserted as NotI fragment and the ∼2 kb HSV thymidine kinase gene as a SalI fragment. The final targeting construct was checked by sequencing and linearized by cutting with PvuI restriction enzyme.

Generation of 2Iα Mice.

The mouse Iα promoter/exon (∼840 bp) and the human β-globin last intron/exon (∼1,100 bp) were amplified by PCR and ligated/cloned as SpeI–HindIII and HindIII–ClaI fragments, respectively, in a modifed pBluescript KS II−. The resulting construct was checked by sequencing. NeoR gene, flanked by two loxP sites, was inserted as a ClaI fragment (∼1.3 kb). The unique SalI site in the resulting plasmid was modified into NotI site. In parallel, in a plasmid containing the ∼6 kb HindIII sequence 3′ of hs4, the unique PmlI site (at ∼2.3 kb downstream of the 5′ HindIII site) was modified into NotI site and used to clone the Iα–β-globin–NeoR insert. A SalI fragment containing the HSV thymidine kinase cassette was finally inserted at the unique XhoI site. The targeting construct was checked by sequencing the appropriate junctions and was linearized by cutting with PvuI restriction enzyme.

Screening of 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ and 2Iα Mice.

The ES cell line CK35 (129Sv) (kindly provided by C. Kress, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) was transfected by electroporation and selected using G418 (300 μg/mL) and ganciclovir (2 μM). Recombinant clones were identified by PCR and Southern blot analysis after a BamHI digest (5′hs1RI clones) or EcoRI digest (2Iα clones), with external 5′ and 3′ probes, respectively. One ES clone of each construct showing homologous recombination was injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts. The male chimeras were then mated with C57BL/6 females to derive a permanent mouse line. GL transmission of the mutation was checked by PCR and Southern blot as for the ES clones. Homozygous N/N mutant mice were mated with EIIa-Cre transgenic mice. The progeny was checked by PCR for Cre-mediated deletion of NeoR. Additional checks were made by sequencing pertinent regions in the genomic DNA. Mice were crossed with 129Sv mice for at least eight generations.

Antibodies and Cytokines.

PE-conjugated anti-CD43 and FITC-conjugated anti-IgG3 antibodies were purchased from BD-Pharmingen. PE- and APC-conjugated anti-B220, FITC-conjugated anti-IgM, FITC-conjugated anti-IgG1, PE-conjugated anti-IgG2b, PE-conjugated anti-IgG2a, APC-conjugated anti-CD21, and FITC-conjugated anti-CD23 were from BioLegend. LPS was purchased from Sigma; anti–IgD-dextran from Fina Biosolutions; IL7, TGF-β, B-LyS, and IL5 from R&D; and anti-CD40 and IL4 from eBiosciences. Anti-CTCF and anti-IgG antibodies were purchased from Millipore, anti-SMC1 from Bethyl, and anti-SMC3 from Abcam. ELISA kit was from Southern Biotech.

Induction of GL Transcription and CSR.

To induce GL transcription and CSR, negatively sorted CD43− splenic B cells were cultured for 2 d and 4.5 d, respectively, at a density of 5 × 105 cells per mL in the presence of LPS (25 µg/mL) + anti–IgD-dextran (3 ng/mL) (hereafter LPS stimulation), LPS (25 µg/mL) + anti–IgD-dextran (3 ng/mL) + IFNγ (20 ng/mL) (IFNγ stimulation), LPS (25 µg/mL) + anti–IgD-dextran (3 ng/mL) + IL4 (25 ng/mL) (IL4 stimulation), or LPS (25 µg/mL) + anti–IgD-dextran (3 ng/mL) + IL4 (10 ng/mL) + IL5 (5 ng/mL) + BLyS (5 ng/mL) + TGFβ (2 ng/mL) (TGFβ stimulation).

Sorted pro-B cells from WT, 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ, and AID−/− were cultured as described (32, 34) in the presence of IL7 (2 ng/mL) for 4 d at a density of 4 × 104 cells per mL and then induced to switch by culturing the cells at the same density and IL7 concentration in the presence of LPS (50 µg/mL) or LPS + IL4 (25 ng/mL) for 2 d.

Flow Cytometry.

At day 4.5 poststimulation, B cells were washed and stained with anti–B220-APC and either anti–IgG3-FITC, anti–IgG2b-PE, anti–IgG2a-PE, or anti–IgG1-FITC. Activated B cells from AID-deficient mice (unable to initiate CSR) were included throughout as negative controls. Data were obtained on 3 × 104 viable cells by using a Coulter XL apparatus (Beckman Coulter).

ELISA.

Six-week-old mice were immunized intraperitoneally with TNP-Ficoll (25 µg/mL) (Santa Cruz) or PBS and challenged again at day 14. For each immunization, 6 WT and 6 mutant mice were used. Serum was collected at day 0, 14, 21, and 28. Plates were coated with 10 µg/mL of TNP. Anti-TNP titers were quantified by standard ELISA.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation.

ChIP experiments were performed as described (11), starting with 20 × 106 cells for resting B cells and 10 × 106 for activated B cells.

qDC-PCR.

Genomic DNAs were purified from WT, 5′hs1RIΔ/Δ, and AID−/− splenic B cells at day 4.5 poststimulation. After EcoRI digestion and circularization, ligation products were subjected to qPCR. Acetylcholine receptor gene was used for normalization. Note that the Sγ3-forward primer is located downstream of the γ3 constant gene; therefore, all CSR events to Sγ3 are presumably detected. Sγ1-, Sγ2b-, and Sγ2a-specific forward primers are located upstream of the EcoRI site toward the end of Sγ1, Sγ2b, and Sγ2a regions; thus, the few CSR events potentially involving the short remaining S sequences downstream of the EcoRI site are not detected.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bernardo Reina San Martin and Laurent Delpy for critical reading of the manuscript and Supriyo De for help with bioinformatics. We also thank the animal facility staff and F. L’Faqihi/V. Duplan-Eche/A.-L. Iscache, at the IPBS and Purpan CPTP plate-form, respectively, for their excellent work. This work was supported by Institut National du Cancer Grant INCA_9363/PLBIO15-134, the Agence Nationale de la Recherche Grant ANR-16-CE12-0017, the Fondation ARC pour la Recherche sur le Cancer Grant PJA 20141201647, the Ligue Contre le Cancer-Comité de Haute-Garonne, and the Cancéropôle Grand Sud-Ouest.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1701631114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bulger M, Groudine M. Functional and mechanistic diversity of distal transcription enhancers. Cell. 2011;144:327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ong CT, Corces VG. CTCF: An architectural protein bridging genome topology and function. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:234–246. doi: 10.1038/nrg3663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bossen C, Mansson R, Murre C. Chromatin topology and the regulation of antigen receptor assembly. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:337–356. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumari G, Sen R. Chromatin interactions in the control of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene assembly. Adv Immunol. 2015;128:41–92. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atchison ML. Function of YY1 in long-distance DNA interactions. Front Immunol. 2014;5:45. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birshtein BK. Epigenetic regulation of individual modules of the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus 3′ regulatory region. Front Immunol. 2014;5:163. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Degner SC, Wong TP, Jankevicius G, Feeney AJ. Cutting edge: Developmental stage-specific recruitment of cohesin to CTCF sites throughout immunoglobulin loci during B lymphocyte development. J Immunol. 2009;182:44–48. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Featherstone K, Wood AL, Bowen AJ, Corcoran AE. The mouse immunoglobulin heavy chain V-D intergenic sequence contains insulators that may regulate ordered V(D)J recombination. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:9327–9338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.098251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo C, et al. CTCF-binding elements mediate control of V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2011;477:424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature10495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garrett FE, et al. Chromatin architecture near a potential 3′ end of the IgH locus involves modular regulation of histone modifications during B-cell development and in vivo occupancy at CTCF sites. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1511–1525. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.4.1511-1525.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas-Claudepierre AS, et al. The cohesin complex regulates immunoglobulin class switch recombination. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2495–2502. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stavnezer J, Guikema JE, Schrader CE. Mechanism and regulation of class switch recombination. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:261–292. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khamlichi AA, Pinaud E, Decourt C, Chauveau C, Cogné M. The 3′ IgH regulatory region: A complex structure in a search for a function. Adv Immunol. 2000;75:317–345. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(00)75008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manis JP, et al. Class switching in B cells lacking 3′ immunoglobulin heavy chain enhancers. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1421–1431. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vincent-Fabert C, et al. Ig synthesis and class switching do not require the presence of the hs4 enhancer in the 3′ IgH regulatory region. J Immunol. 2009;182:6926–6932. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bébin AG, et al. In vivo redundant function of the 3′ IgH regulatory element HS3b in the mouse. J Immunol. 2010;184:3710–3717. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinaud E, et al. Localization of the 3′ IgH locus elements that effect long-distance regulation of class switch recombination. Immunity. 2001;15:187–199. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vincent-Fabert C, et al. Genomic deletion of the whole IgH 3′ regulatory region (hs3a, hs1,2, hs3b, and hs4) dramatically affects class switch recombination and Ig secretion to all isotypes. Blood. 2010;116:1895–1898. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-264689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rouaud P, et al. Enhancers located in heavy chain regulatory region (hs3a, hs1,2, hs3b, and hs4) are dispensable for diversity of VDJ recombination. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:8356–8360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.341024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kakkis E, Mercola M, Calame K. Strong transcriptional activation of translocated c-myc genes occurs without a strong nearby enhancer or promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:77–96. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cogné M, et al. A class switch control region at the 3′ end of the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus. Cell. 1994;77:737–747. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delpy L, Le Bert M, Cogné M, Khamlichi AA. Germ-line transcription occurs on both the functional and the non-functional alleles of immunoglobulin constant heavy chain genes. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2108–2113. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Péron S, et al. AID-driven deletion causes immunoglobulin heavy chain locus suicide recombination in B cells. Science. 2012;336:931–934. doi: 10.1126/science.1218692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braikia F-Z, et al. A developmental switch in the transcriptional activity of a long-range regulatory element. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35:3370–3380. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00509-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pefanis E, et al. RNA exosome-regulated long non-coding RNA transcription controls super-enhancer activity. Cell. 2015;161:774–789. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seidl KJ, et al. Position-dependent inhibition of class-switch recombination by PGK-neor cassettes inserted into the immunoglobulin heavy chain constant region locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3000–3005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oruc Z, Boumédiène A, Le Bert M, Khamlichi AA. Replacement of Igamma3 germ-line promoter by Igamma1 inhibits class-switch recombination to IgG3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20484–20489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608364104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rao SS, et al. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell. 2014;159:1665–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin SG, Guo C, Su A, Zhang Y, Alt FW. CTCF-binding elements 1 and 2 in the Igh intergenic control region cooperatively regulate V(D)J recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:1815–1820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424936112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benner C, Isoda T, Murre C. New roles for DNA cytosine modification, eRNA, anchors, and superanchors in developing B cell progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:12776–12781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512995112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wuerffel R, et al. S-S synapsis during class switch recombination is promoted by distantly located transcriptional elements and activation-induced deaminase. Immunity. 2007;27:711–722. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar S, et al. Flexible ordering of antibody class switch and V(D)J joining during B-cell ontogeny. Genes Dev. 2013;27:2439–2444. doi: 10.1101/gad.227165.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cerutti A, Cols M, Puga I. Marginal zone B cells: Virtues of innate-like antibody-producing lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:118–132. doi: 10.1038/nri3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sayegh CE, Jhunjhunwala S, Riblet R, Murre C. Visualization of looping involving the immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus in developing B cells. Genes Dev. 2005;19:322–327. doi: 10.1101/gad.1254305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]