Abstract

Objective. To design and implement an instrument capable of providing students with valuable peer feedback on team behaviors and to provide results of the administration of the instrument.

Methods. A three-part instrument was designed that requires teammate rankings with justification on attributes aligned with school outcomes and team functioning, reporting of student behaviors, and provision of feedback on the value of peer contributions to their team. Score results after three years of administration were analyzed.

Results. Six evaluations per year were completed by members of four different professional classes over a three-year time period. Mean scores increased slightly as students progressed through the program. Students were able to differentially score peers on attributes and behaviors.

Conclusion. The peer evaluation instrument presented here provides formative and summative feedback through qualitative and quantitative scores that allow students to acknowledge differential contributions of individual team members.

Keywords: team-based learning, TBL, peer evaluation, peer assessment, pharmacy

INTRODUCTION

Peer evaluation is used in various educational settings, including medical and professional schools, as a means to supplement evaluations made by faculty. In order to be useful as a formative and summative tool, the peer evaluation process must be accepted by students. Judgments by student peers must be guided by quality criteria or performance scales that support the content validity of the measurement.1,2 Under such conditions, peer evaluation has been found to be reliable and to correlate positively with faculty evaluations of students in both medical and pharmacy education.1,2

The Regis University School of Pharmacy (RUSOP) uses team-based learning (TBL) as the primary pedagogy in most courses curriculum-wide. According to standard TBL practices, peer evaluation is an essential component of the grading process, used to recognize the contributions of individuals to the success of the team.3 However, not all programs that report using TBL use a peer evaluation process.4 The formative utility of peer evaluation is evident when students begin to monitor their own behaviors and make adjustments in anticipation of summative assessments. This reflects the ability of peer evaluation to create social control of the learning environment. Students who are conscious that peer evaluation will affect their course grade are more accountable for actively participating in the learning process.4

Teams are formed in the first semester using a method intended to distribute attributes and liabilities. Students remain on the assigned team in all team-based courses for an entire semester. After the first semester, team selection is randomized with two caveats: no three team members may appear on the same team in two consecutive semesters, and all teams must have members of the opposite sex. Teams are comprised of five or six members, depending upon the size of the matriculating class.

The peer evaluation process at RUSOP has evolved in response to the unsatisfactory results of using previously described instruments. The peer evaluation instrument utilized in the 2009-2010 academic year in RUSOP TBL courses was modified from the Texas Tech Method5 and constituted 10% of each student’s overall grade. Students used the form at the conclusion of the fall 2009 semester to categorize their teammates’ performance on each of 12 items. Scores indicate students’ performance as “too little,” “just right,” “too much,” or degrees in between, using a 9-point scale.

After the 2009 fall semester, the team performance survey (TPS), an 18-point instrument used to assess the quality of team interactions6 was administered to RUSOP students. When using the graded RUSOP peer evaluation instrument, six out of 10 teams gave every one of their team members a perfect score. In contrast, no teams received perfect scores on the ungraded TPS. Written comments on the RUSOP peer evaluation instrument were consistent with the TPS results, such that students identified opportunities to improve team interactions despite submitting perfect numerical scores. These conflicting findings suggest that students are able to discern effective team member performance, yet are not willing to provide quantitative evaluations that would negatively affect a team member’s overall grade.

Data obtained from the TPS and peer evaluation form – in combination with feedback from student assessment, governance groups, and one-on-one faculty advising interactions – confirmed widespread reluctance among students to critically score the 12-item RUSOP peer evaluation instrument because of the potential for negatively impacting a fellow student’s grade. “Straight-lining” of student peer evaluation scores led to inflation of the student’s grades, which gave cause to drop the grade weight from 10% in the fall semester to 2% the following spring. The instrument’s inability to capture qualitative feedback from peers made it difficult for students to identify areas for improvement and led to the decision to create a new instrument for the 2010-2011 academic year.

We present this new instrument and discuss the results collected from utilizing the new process for three full academic years, and provide results of validation studies.

METHODS

A task force was assembled with representative faculty members from the curriculum, assessment, and student affairs standing committees. The overall goal of the task force was to create a process to identify differential behavior and effort among students within a team while also providing a template for students to give and receive peer-to-peer feedback. Student representation on the task force was equal to that of faculty to achieve the greatest level of student engagement possible. Three behaviors – principled, supportive, and responsible – were identified as well-aligned with our school’s mission and deemed valuable to team formation, cohesiveness, and effectiveness. These behaviors were defined with respect to teamwork and provided the structure for the creation of the instrument.

The new peer evaluation process created by the task force includes student education on peer assessment, a three-part instrument, and a protocol for administering both a formative (midterm) and summative (end of term) peer evaluation. The process includes a mandatory review of the formative results with each student’s assigned faculty adviser. During orientation, each incoming class receives a presentation delivered by a student representative to educate students on team dynamics and the value of peer feedback. Included is a team application activity that provides practice in the recognition and assessment of common team behaviors. The session concludes with a faculty-facilitated skit that exhibits “effective” and “blocking” team member behaviors.

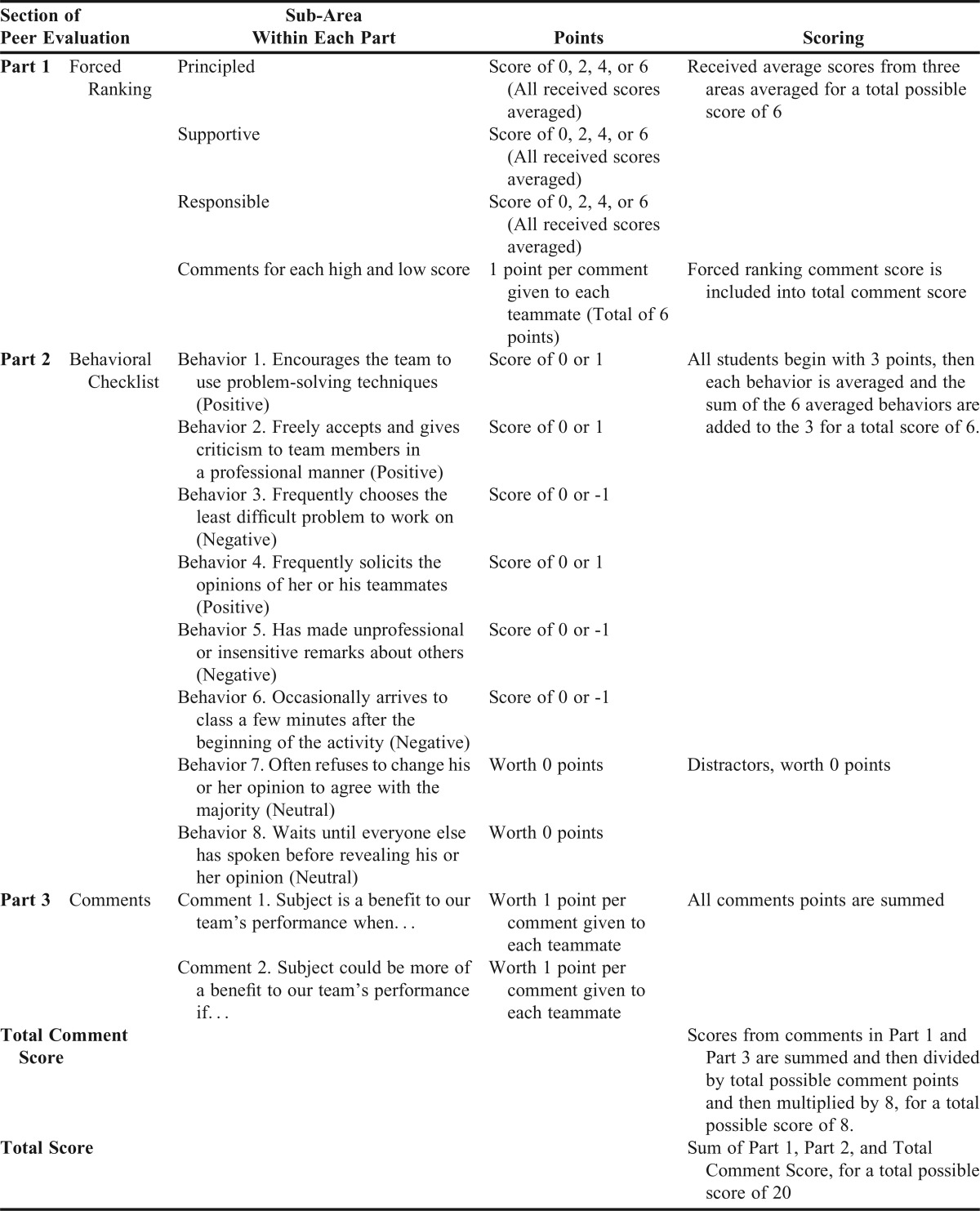

The evaluation instrument developed by RUSOP (Table 1) contains three parts: a forced-ranking table with the categories of responsible, supportive, and principled; a behavioral checklist, including beneficial and harmful behaviors; and required comments, including one positive statement and one statement that is intended to bring improvement in a given area.

Table 1.

Description of Peer Components and Scoring

The categories included in the forced ranking matrix are three qualities (responsible, supportive, and principled) that are highly valued at our university. To guide each student’s selections, these are defined on the instrument as follows. A “responsible” teammate arrives to class on time and is well-prepared, always completes his or her share of the work, is reliable and loyal to the team’s goals, etc.; a “supportive” teammate cooperates with team members, listens to others’ opinions and ideas, reflects on the team’s progress, is sensitive to others’ needs, etc. A “principled” teammate strives to learn more than the bare minimum, encourages integrity and honesty, shows respect to all team members, is self-confident to the benefit of the team, etc.

The three qualities are additionally assessed using behaviorally anchored statements, as described in Part 2 below. All teammates are ranked in descending order for each category according to their ability to exhibit characteristic qualities, such that the teammate who best exemplifies the category is given the top ranking. The student must rank every teammate for each category, and no two teammates may receive the same ranking. In the event that a team has six members, the score of 4 is used twice, which provides an additional middle score to be assigned. The student is required to justify the top and bottom rankings in each category with descriptive statements and is awarded points toward their own peer evaluation for doing so.

Part 2 consists of a checklist of behaviors that relate to interactions within the team. The student completes the checklist for each teammate and checks any statements that apply to that teammate’s observed behaviors. When checked, behavior statements may influence the score positively, negatively, or not at all. Some of these behavioral statements refer to the qualities assessed in Part 1 and allow for a measure of internal consistency for the instrument. For example, a teammate who “frequently solicits the opinions of her or his teammates” is considered a supportive teammate. Accordingly, the rankings in Part 1 also are expected to be consistent with the checked behavioral statements in Part 2.

Part 3 is a prompted response with an open field to generate comments for constructive feedback. A student who completes prompts on all members’ contributions to team performance receives points toward their own evaluation.

A student’s score on the peer evaluation is calculated from the three parts of the instrument for a total of 20 possible points. The forced ranking section can generate a total possible score of 6 points. Students can receive a 0, 2, 4, or 6 from each teammate on each of the three qualities. The student receives an average score for each of the three qualities and a single score that represents their individual average of all qualities. Teams generally have only five members, but those teams having six members are directed to use the score “4” twice in their rankings.

The behavioral checklist in Part 2 is worth a total of 6 points, and all students begin with a baseline point value of 3 points. The checklist contains statements that describe three positive behaviors worth 1 point each, three negative behaviors worth -1 point each, and two additional statements worth 0 points each. Each behavior score is averaged, then the sum of all behaviors is added to the baseline points. Students are blinded as to the scoring value of each statement.

In the comments section (Part 3), students are prompted to describe ways in which teammates benefit team performance and ways in which they can provide greater benefit. The points from these prompted comments combined with the points awarded for the comments required to justify the high and low ranking in Part 1 are normalized to a total point value of 8. An evaluator who provides these two comments for each of their teammates, in addition to providing justification comments for the highest and lowest rankings in Part 1, receives 8 points toward their own peer evaluation grade. The substance of these comments are not analyzed; students receive points regardless of content. The total score of the instrument is the sum of Parts 1 and 2, and the total comment score, for a total possible score of 20.

Students complete the formative peer evaluation in the first few weeks of a new academic semester. Students are then required to meet with their faculty advisers to discuss areas in which the student has been a benefit to their team and areas where improvement is needed to provide a higher benefit to the team. Adviser-mediated review dictates that peer feedback is anonymously presented to students and assists students with identifying areas for growth.

The formative peer evaluations allow students to witness how the evaluation will be translated into a grade and plan changes to their behavior before the summative evaluation takes place. This practice is consistent with reports demonstrating that when students receive thoughtful comments by peers in a timely and confidential manner, along with support from advisers, they find the process powerful, insightful, and instructive.7

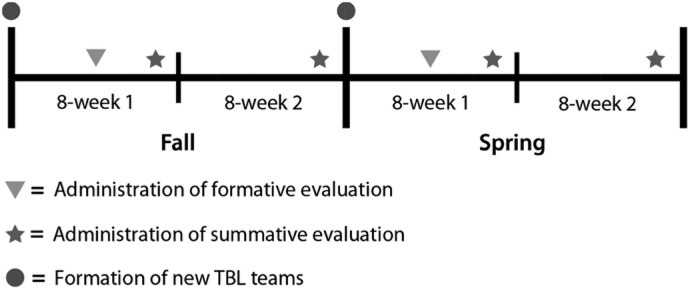

The summative evaluation administered at the end of each course represents 10% of individual student grades in all TBL courses. These results are presented to students through their faculty advisers to aid in the continual development of the individual’s ability to function on a team. It should be noted that RUSOP courses are eight weeks and, therefore, there are two courses per semester. As such, there are three administrations of peer evaluation in each semester, one formative evaluation at the beginning of the first course, and a summative evaluation after the completion of each individual course (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Peer Evaluation Administration Timeline.

To assess peer evaluation scores, a data set was assembled that included RUSOP students in the first to third year of pharmacy school from the academic years 2010-2011 to 2012-2013. These data included all formative and summative peer evaluations from fall and spring semesters, a total of six administrations per year. Variables were added to the data to identify the student being evaluated, the evaluator, the evaluation type, and the student’s class. Validation studies excluded the first year of data to alleviate any potential anomalies that may result from administration of a new instrument.

In examining the distribution of grades using the forced ranking section, it was important to analyze trends within each academic year and among the six evaluations given to each class.There was an initial concern that over time individual teams would collaborate to “game the system” and begin to distribute rankings evenly across all team members.

Individual scores on the forced ranking and behavioral checklist portions of the instrument were categorized as above average, average, or below average based on the distribution of scores. Standard deviations and means were calculated by class for each peer evaluation. Scores falling between -1 and +1 standard deviation of the mean were classified as average.

Scores greater than one standard deviation under or over the mean were classified as above or below average scores, respectively. These classifications were used to determine the percent distribution of scores. As the third part of the evaluation form is qualitative, data acquired from this part were not used to determine inter-team discrimination.

A structural validity test was conducted on the peer evaluations using a qualitative, grounded theory approach to compare the comments given in the forced ranking section of the instrument to the numerical score given in the same section. This test ensures that when an evaluator ranks a particular student as either the most or least principled/supportive/responsible of the team, they are justifying that ranking with a comment that matches. A codebook was established a priori to determine comment match and not match with the traits. One of the researchers used this codebook to analyze the qualitative data. To be considered a match, a comment was required to provide additional feedback consistent with the most or least ranking among the team’s members for each of the three traits: principled, supportive, and responsible. A comment match was indicated with a dummy variable, where 1 equals a match in which the comment supported the ranking of most or least principled/supportive/responsible, and a 0 indicated the comment did not match the ranking. Comments that simply stated the word “principled,” “supportive,” or “responsible” with no explanation, those that said all team members were equal, and comments indicating scores were randomly assigned were designated as not a match with the traits.

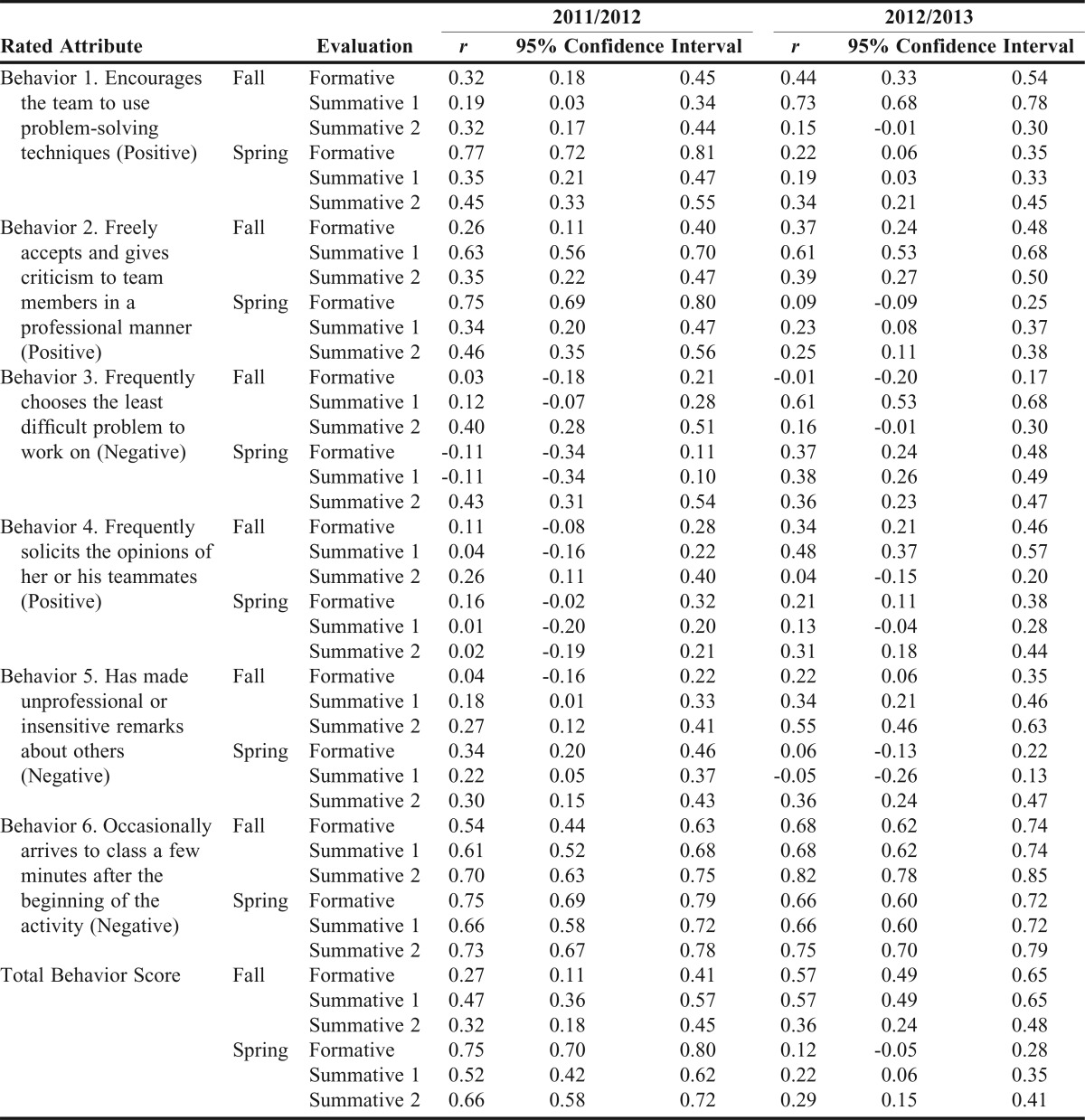

A content validity test was conducted to correlate the subject’s scores with that of the individual’s attributes.7 Because a subject is evaluated within each administration of the peer evaluation by each member of his/her team, that subject will have multiple ratings for each part. An Intraclass Correlation Case 3 (ICC[3,κ]) analysis was conducted to measure the rater reliability of the mean of the forced ranking section (ie, the three attribute categories and the total score for Part 1) and the behaviors checklist (ie, the value of each of the six behaviors and the total score for Part 2) of the peer evaluation instrument.8,9 We utilized an ICC[3,κ] model taking the form of:

|

Where μ is the overall population mean of the ratings; ai is the difference from μ of the mean of rater i’s ratings; bj is the difference from μ of subject j’s mean rating; abij is the difference in rater i’s rating tendency; and ε is the error term.

An ICC[3,κ] was conducted on each of the peer evaluation results; coefficients and confidence intervals were reported for each item. An a priori coefficient estimate of .30 or higher was selected as being a fair strength of agreement between raters.10

RESULTS

Approximately 4,950 observations were made for ∼275 students completing six evaluations per year. The number of students receiving average scores in the first year was approximately 73%, increasing to approximately 80% in the third year of administration (Figure 2). There has been consistency in scores in the forced ranking part over three years (AY 2010-2011, x=3, max=5.5, min=0.7, SD=0.6; AY 2011-2012, x=3, max=5.5, min=0, SD=0.5; AY 2012-2013, x=3.1, max=6, min=0, SD=0.7.

Of note in the behavioral checklist scores was the trend upward of the overall mean as the instrument aged from year 1 to year 3 (AY 2010-2011, x=5.5, max=6, min=3.3, SD=0.5; AY 2011-2012, x=5.6, max=6, min=2.5, SD=0.5; AY 2012-2013, x=5.6, max=6, min=2, SD=0.5). A direct result of an increased mean is that the number of students who fell into the average score category increased over time.

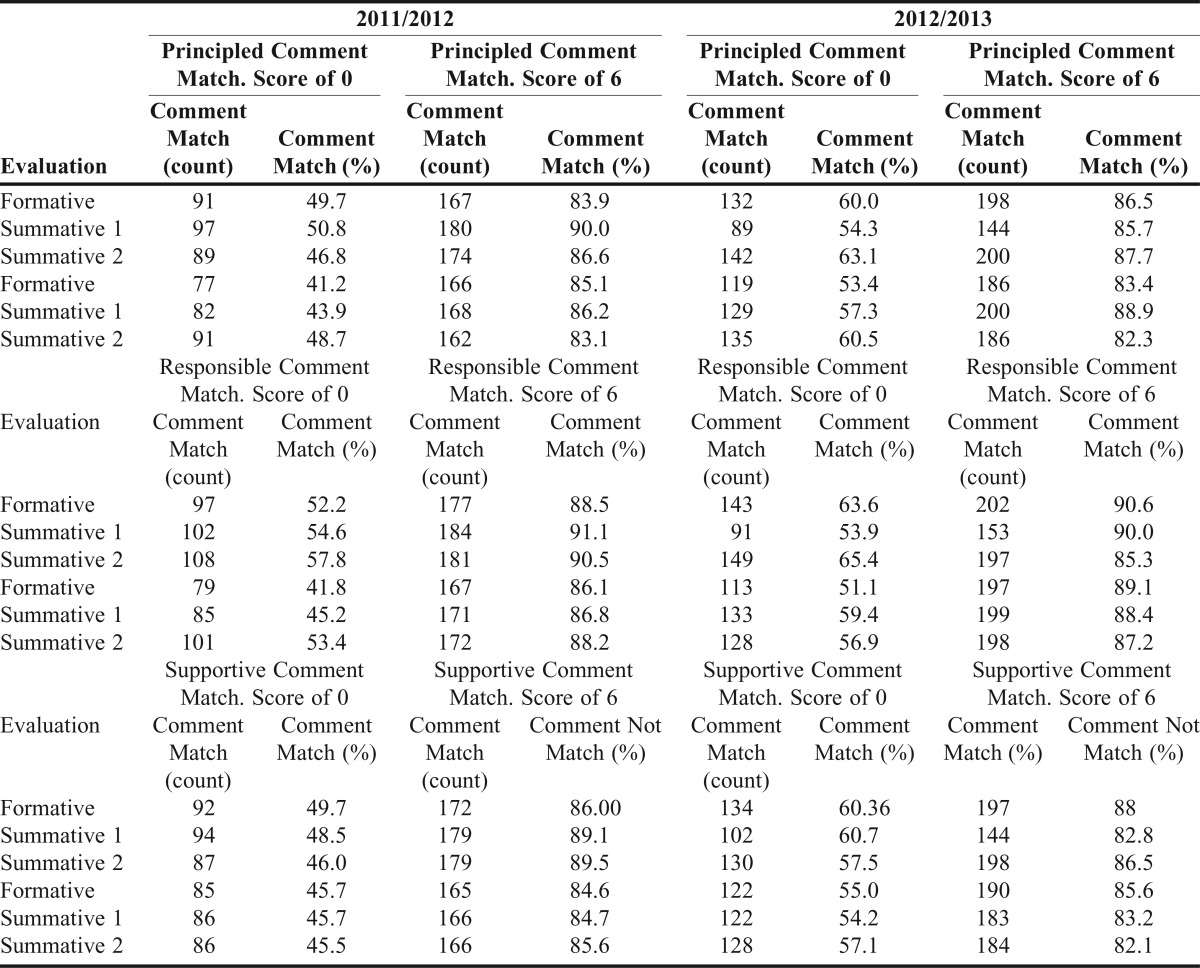

In examining the structural validity of Part 1 of the peer evaluation instrument, differences exist between the percent match between comments and rankings for those ranked as most and those ranked as least (Table 2). For rankings of least, comments matched rankings 41.2% to 65.3% across all evaluations. When the evaluator ranked the subject as most, comments matched rankings 82.1% to 91.1% across all evaluations.

Table 2.

Comment-Score Match for Part 1 of the 2011/2012 and 2012/2013 Administration of the Peer Evaluation Instrument

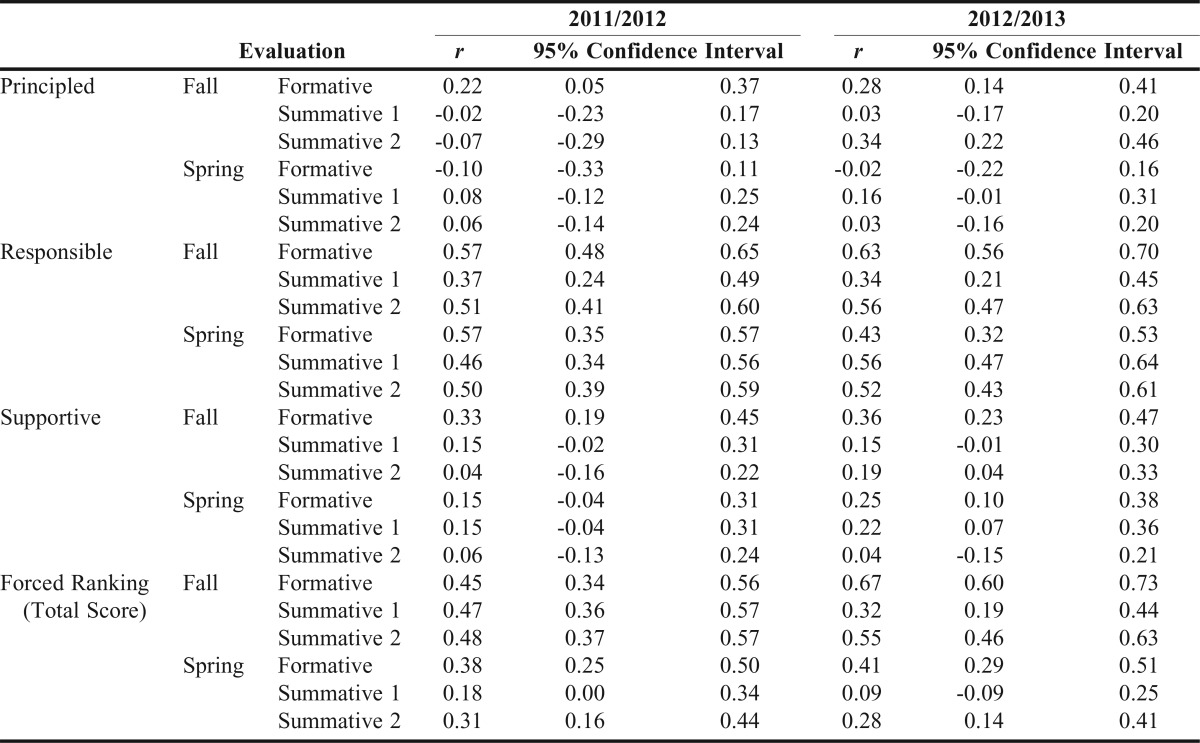

The ICC[3,κ] results for Part 1, forced ranking, of the peer evaluations demonstrate different levels of agreement among raters for each of the three attributes that constitute Part 1 of the peer evaluation (Table 3). The principled and supportive attributes have ICC coefficient estimates that are, on average, well below .30 for the six peer evaluations conducted during the two observed academic years.

Table 3.

Intraclass Correlation Case 3 (ICC[3,k]) of Part 1 of the Peer Evaluation Instrument

The responsible attribute demonstrates more promising coefficient estimates that are at least above a .3, with a majority of the six evaluations nearing or exceeding a level of .5. The coefficient estimates for the total score for Part 1 of the evaluation also demonstrate higher agreement. However, it looks as if these levels might be confounded by the responsible attribute.

The ICC[3,κ] analysis of Part 2, the behavioral checklist, produced coefficient estimates for the positive behaviors at or above a .30 level of agreement between raters for all or most of the evaluations administered (Table 4). Four of 12 evaluations of performance on Behavior 1 yielded coefficient estimates below .30 (r=.19; .15; .22; .19), where the other eight evaluations had coefficient estimates between r=.32 to .77. Four of 12 evaluations of performance on Behavior 2 yielded coefficient estimates that were below .30 (r=.26; .09; .23; .25) with the remaining coefficient estimates between r=.35 and .75. Behavior 6 had the highest consistent coefficient estimate of r=.54 to .82, with no evaluations with a coefficient below the a priori level.

Table 4.

Intraclass Correlation Case 3 (ICC[3,k]) of Part 2 of the Peer Evaluation Instrument

Of the negative behaviors, 3, 4, and 5 indicate low levels of agreement between raters. Behavior 3 had coefficient estimates between r=-.11 to .61, however six of the 12 estimates were below r=.16. For behavior 4, nine of the 12 estimates were below the .30 level. Behavior 5 had seven of the 12 estimates below the .30 level with a range of r=-.05 to .55.

DISCUSSION

The Regis University SOP faculty and student task force developed a novel peer evaluation instrument that provides authentic feedback to students to improve their contributions as team members. Further, the tool provides student-generated data regarding team member performance for use in determining student grades in a TBL environment. The analyses of peer evaluation scores presented here demonstrate that some students use the tool to differentiate between levels of student performance rather than game the system to maximize grades of fellow students independent of their performance. Finally, the process and instrument can be adapted for use for a variety of team sizes.

The highest score possible on Part 1 is 6 points, which represents half of the evaluation points awarded by peers. The lowest possible score on Part 1 is 0 points. Note that in order to receive a score of 6 or 0 points on Part 1, the student must be unanimously ranked at the top or bottom of every category by all teammates. Only exceptional ability or failure to demonstrate each of these characteristics will produce the highest or lowest scores.

If every student is perceived as contributing equally to team performance, all team members should receive a score of 3 points for Part 1, on average. Although this average score is only 50% of the total points possible for this part, when combined with points from other parts of the evaluation, it can result in a final score of 17 out of 20 (85%).

The forced ranking section of the new instrument requires students to differentiate teammates in the three qualities: responsible, supportive, and principled. These three categories derive from programmatic outcomes that reflect the Jesuit tradition of values-centered education focusing on personal development and leadership in the service of others. In addition, these qualities are related to team cohesiveness and effectiveness. Initial concern was voiced that students would strategically score teammates in this part such that all students on a team received similar scores. However, the results show that some students are able to evaluate teammates differentially in terms of the three behavioral qualities measured by the instrument. This observation is supported by the fact that in each academic year the minimum score for this category is equal to or approximately zero and that the maximum for each academic year is between 5.5 and 6 (Figure 2).

Students appear willing to identify those peers who excel as teammates and also identify the few percentage of peers who need to improve considerably. The observation that students who have used the same instrument for consecutive evaluations do not appear to be evenly distributing scores such that all students receive similar grades further supports the conclusion that a large percentage of students are willing to score teammates based on performance.

The scores for Part 2 range from 0 to 6 points, representing the other half of the evaluation points awarded by peers. Any student who earns unanimous recognition for all three positive behaviors and no negative behaviors will receive 6 points. Any student who earns unanimous recognition for all three negative behaviors and no positive behaviors will receive 0 points. The baseline points are intended to avoid the possibility of generating an overall negative score, which would be difficult to interpret in traditional grading schemes. As a result, an important distinction between Parts 1 and 2 is that every student on the team can earn full points on Part 2 if every student is recognized as exhibiting all (and only) beneficial team behaviors. The students, therefore, may choose to award points based on behaviors that lead to or detract from team successes, but also could assign all teammates the maximum point value.

Positive statements in Part 2 help identify ways in which students are contributing to team performance. Additionally, these statements provide advisers with opportunities to praise students for performance in certain areas of team function. Quantitatively rewarding the student reinforces team-building behaviors.

One reason for labeling and scoring particular statements as “negative” is to send the message that certain behaviors can be deleterious to team cohesiveness. Quantitatively, the effect of exhibiting team-blocking behaviors is a reduction in the student’s peer evaluation grade. The intended effect of being recognized by peers as interfering with team cohesiveness is increased self-awareness and the potential for remediating negative behaviors.

The additional statements in Part 2 describing neutral or ambiguous behaviors are intended to stimulate thought during the evaluation rather than generate points for grading. Data from Part 2 suggest that students are willing to check positive and negative behaviors based on merit rather than in an effort to maximize teammate scores. Unlike the forced ranking section, students have the option of awarding each teammate 6 points on the behavior checklist. The fact that scores for each academic year range from 2 to 6 shows that students are willing to distinguish good teammates from those who are not performing as well.

The points awarded in Part 3 are not conferred as a result of peer opinion, but are earned by completing all required comments for feedback. As a result, each student is accountable for earning 8 points (40%) of his or her own peer evaluation grade. This value was selected to generate significant impetus for students to provide comments to their peers.

The instrument demonstrates a level of validity consistent for use in a high stakes environment. The structural validity of the peer evaluation instrument was measured utilizing comment-score matching for the forced rankings and indicated students are more likely to make a qualitative comment in support of the highest ranking than the lowest ranking. Students assigning a 0 to a peer may feel as if ranking a student at the lowest position is equivalent to saying that team-member is not principled/ responsible/ supportive. The lowest position (a score of 0 on a team of 5) would be the fourth most principled/ responsible/supportive person on the team. Within a high-functioning team, the “fourth most” position may actually reflect strong performance. Because of this possible misconception, students may have difficulty providing what could be interpreted as a negative comment. This interpretation of these results would indicate the instrument is structurally valid for the highest rankings and their matching comments. The instrument itself could be modified to allow students to select from a list of text responses (ie, most supportive, second most supportive, etc.) instead of from a numerical scale that includes 0. Adjustments to the training provided prior to using the instrument should be made to educate students on the true meaning of a low ranking and how to provide constructive and useful feedback to their team members. Finally, additional education could be provided to students to assist them in discerning most and fourth most rankings among their peers.

Based on the content validity evaluation using an intra-rater reliability analysis, the instrument, on average, was more consistent between raters with the “responsible” attribute. The principled and supportive categories did not provide similar results, with the majority of the evaluations falling well below the a priori agreement level. It may be easier for students to identify traits related to a team-member being responsible, leading to more agreement among raters for that attribute. The behaviors related to being principled and supportive may be more difficult to identify or observe leading to more variability in rankings. This would indicate that the measurements of principled and supportive attributes are not substantively valid, and students are having difficulty aligning these concepts to real-world behaviors. Additional education for students to assist with identifying teammate behaviors that are principled and supportive may improve the performance of the instrument in these areas.

Regarding the content validity of Part 2, there seems to be more consistency and agreement between evaluators when rating team members on positive behaviors than negative behaviors. It would seem, more often than not, that students are more willing to agree with each other and assign positive points to their team members than they are to assign negative points. Being on a team does create a sense of camaraderie and may lead to friendship bias when assigning points to peers. Because of this friendship bias phenomenon, it can be difficult to accurately ascertain from peers if a team member is demonstrating a negative behavior. Internal research does find that the instrument is fairly good at identifying team members who are overall a benefit or could be more of a benefit to the team. However, the great majority of students will fall into the average category.

The nature of the pharmacy program prevents a more rigorous analysis of the instrument because of the changes of teams each semester. Therefore, the ability of conducting an intra-rater reliability analysis over all three years is limited to only semester timeframes. In addition, the formative nature of instrument is intended to create growth among the student. Thus, we expect not to see the same results among a team between formative and summative assessments.

CONCLUSION

Student peer evaluation can be a vital source of feedback for students learning in a team environment such as team-based learning. In addition, in courses using team-based learning, peer evaluation reflects student-generated assessment of the contribution to team learning by each team member. The peer evaluation instrument developed and implemented by Regis University School of Pharmacy provides formative and summative feedback through qualitative and quantitative scores that allows students to acknowledge differential contributions of individual team members. Authentic and actionable feedback, communicated to students through faculty advisers, holds students accountable for their own behavior while giving them opportunities for improvement and personal development.

REFERENCES

- 1.Speyer R, Pilz W, Van Der Kruis J, Brunings JW. Reliability and validity of student peer assessment in medical education: a systematic review. Med Teach. 2011;33(11):e572–e585. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.610835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine RE, Kelly PA, Karakoc T, Haidet P. Peer evaluation in a clinical clerkship: students’ attitudes, experiences, and correlations with traditional assessments. Acad Psychiatry. 2007;31(1):19–24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.31.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michaelsen LK, Knight AB, Fink LD. Team-Based Learning: A Transformative Use of Small Groups. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Publishing Group; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohland MW, Layton RA, Loughry ML, Yuhasz AG. Effects of behavioral anchors on peer evaluation reliability. J Eng Educ. 2005;94(3):319–326. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michaelsen LK, Parmelee DX, McMahon KK, Levine RE. Team-Based Learning for Health Professions Education: A Guide to Using Small Groups for Improving Learning. Stylus Publishing, LLC. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson BM, Levine RE, Kennedy F, et al. Evaluating the quality of learning-team processes in medical education: development and validation of a new measure. Acad Med. 2009;84(10):S124–S127. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b38b7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Predicting the performance of measures in a confirmatory factor analysis with a pretest assessment of their substantive validities. J Appl Psychol. 1991;76(5):732–740. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrews FM. Construct validity and error components of survey measures: a structural modeling approach. Public Opin Q. 1984;48(2):409–442. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calder BJ, Phillips LW, Tybout AM. The concept of external validity. J Consum Res. 1982;9(3):240–244. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferguson L. External validity, generalizability, and knowledge utilization. J Nurs Scholars. 2004;36(1):16–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]