Abstract

Background:

Diabetic patients are more susceptible to cutaneous fungal infections. The higher blood sugar levels cause increasing the cutaneous fungal infections in these patients. The main objective of this study was to find the frequency of fungal infections among cutaneous lesions of diabetic patients and to investigate azole antifungal agent susceptibility of the isolates.

Materials and Methods:

In this study, type 1diabetes (n = 78) and type 2 diabetes (n = 44) comprised 47 cases (38.5%) with diabetic foot ulcers and 75 cases (61.5%) with skin and nail lesions were studied. Fungal infection was confirmed by direct examination and culture methods. Antifungal susceptibility testing by broth microdilution method was performed according to the CLSI M27-A and M38-A references.

Results:

Out of 122 diabetic patients, thirty (24.5%) were affected with fungal infections. Frequency of fungal infection was 19.1% in patients with diabetic foot ulcer and 28% of patients with skin and nail lesions. Candida albicans and Aspergillus flavus were the most common species isolated from thirty patients with fungal infection, respectively. Susceptibility testing carried out on 18 representative isolates (13 C. albicans, five C. glabrata) revealed that 12 isolates (10 C. albicans and two C. glabrata isolates) (66.6%) were resistant (minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC] ≥64 mg/ml) to fluconazole (FCZ). Likewise, eight isolates (80%) of Aspergillus spp. were resistant (MIC ≥4 mg/ml), to itraconazole.

Conclusion:

Our finding expands current knowledge about the frequency of fungal infections in diabetic patients. We noted the high prevalence of FCZ-resistant Candida spp., particularly in diabetic foot ulcers. More attention is important in diabetic centers about this neglected issue.

Keywords: Diabetes, diabetic foot ulcer, fluconazole, itraconazole

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is the most common endocrine metabolic disease.[1] The prevalence of DM in Iran has been reported 7–17% and is increasing in most populations.[2] Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is more common than T1D. The predisposing factors, high blood glucose, vascular insufficiency, neuropathy and various immunological disturbances, facilitate conditions for colonization of pathogenic fungi, including Candida, Dermatophytes, Malassezia, Zygomycetes, Aspergillus, and Fusarium species in DM patients.[3,4,5] Therefore, screening and early detection of fungal infections in high-risk individuals is critical for prevention of grave complications such as foot amputation. In some diabetic patients, developing cutaneous lesions and nail infections has been documented.[6] More than 75% of DM patients are at risk for diabetic ulcers. Diabetic foot ulcer is one of the most important complications in diabetic patients. About 15% of foot ulcers in diabetic patients lead to amputations. Although for every 30 s, one leg is amputated in the world due to DM, 80% of these cases are preventable.[7] The foot lesions are often chronic and resistant to treatment. These ulcers are prone to secondary infections; bacterial, fungal, and viral.[8] Poor controlled had significantly higher fungal infection in diabetic foot ulcers and require careful attention and management.[9] There are rare reports about the diabetic foot ulcers and cutaneous fungal infections in patients with DM in Iran and also lack of comprehensive studies on the antifungal susceptibility patterns of the isolates in the world. Hence, we designed this study to determine the azole susceptibility (fluconazole (FCZ) on yeasts and itraconazole (ITC) on molds) of the isolated species to improve management of DM patients.

Materials and Methods

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study performed in Isfahan, Iran, from December 2014 to April 2015.

Sample collection

The study population consisted of DM patients with cutaneous lesions admitted to the hospitals and diabetic centers of Isfahan in Iran. A questionnaire form was developed to record demographic data and medical history of the patients, type of diabetes, examination details, and type of the lesions. Patient-related data were collected in accordance with the applicable rules concerning the review of research ethics committees at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and informed consent.

Identification

The foot ulcer samples, skin, and nail specimens of cutaneous lesions were sent to the laboratory for further processing. Species identification of yeast isolates was performed with standard procedures including morphology, cornmeal agar test, and CHROMagar Candida (HiMedia, Mumbai, India). All Aspergillus isolates were originally identified by macroscopic and microscopic morphology of conidia and conidia-forming structures. The isolates were cultured on sabouraud dextrose agar at 30°C for 1 week.

In vitro antifungal susceptibility testing

In vitro antifungal susceptibility testing was performed using a broth microdilution method according to the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M27-A for yeasts and M38-A guidelines for filamentous fungi.[10] The final concentrations of ITC (0.0313–16 μg/ml) and FCZ (0.125–64 μg/ml) performed in the wells.[11,12]

RPMI 1640 plus 2% glucose (pH 7.0) as the test medium and a final inoculum of 0.5–2.5 × 103 colony-forming unit (CFU)/ml prepared spectrophotometrically for yeast and final concentration of 0.4–5 × 104 CFU/ml for mold fungi. The microtiter plates were incubated at 35°C for 24–48 h and visual readings were performed with a microtiter reading mirror. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for the azoles was defined as the lowest concentration of the azole that inhibited the visible growth of the microorganism. Quality control strains Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019, Candida krusei ATCC 6258, and Aspergillus flavus ATCC 204304 were used in all experiments by the CLSI recommended.[13]

Isolates with MIC <8z mg/ml were considered to be susceptible to FCZ whereas isolates with MIC >64 mg/ml were considered to be resistant as well as isolates with MICs between 16 and 32 mg/ml were FCZ susceptible-dose dependent (S-DD).

Likewise, isolates were considered susceptible to ITC with MIC ≤1 μg/ml, intermediate with MIC 2 μg/ml and resistant isolates to ITC with MIC ≥4 μg/ml, according to the CLSI for mold fungi.

Statistical methods

Baseline data of the participants between groups were compared by t-test and Chi-square test as appropriate IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp was used for statistical analyses.

Results

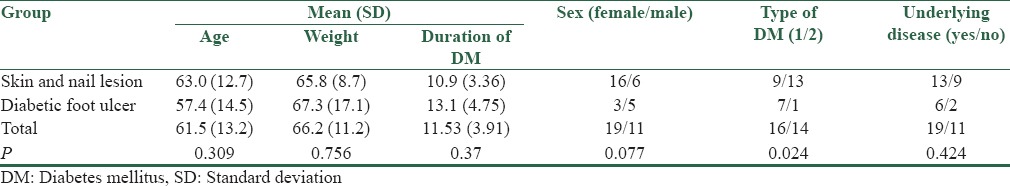

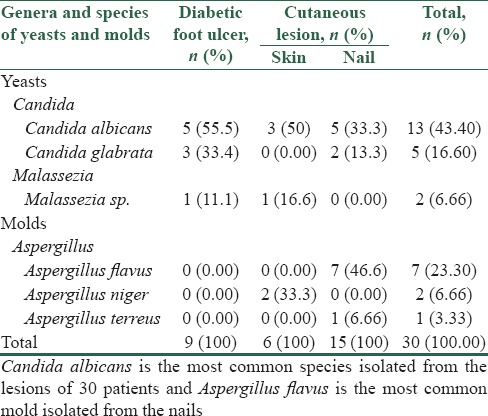

One hundred and twenty-two patients participated in this study, 78 (64%) with T1D and 44 (36%) with T2D. From a total of nine patients with diabetic foot ulcers, five (55%) had a history of amputation and the mean of their blood glucose level were ≥200 mg/dl [Figure 1]. More than 80% of patients with diabetic foot ulcers had a history of trauma and burns, and more than 50% of them had neuropathic ulcers. Baseline characteristics of the participants with fungal infections are presented in Table 1. The fungal infection was significantly different in two groups with two types of diabetes (P = 0.024). Among 122 DM patients, 75 with skin and nail lesions and 47 were with diabetic foot ulcers where thirty (24.5%) patients were affected with fungal infections. Frequency of fungal infection was 19.1% in patients with diabetic foot ulcer and 28% of patients with skin and nail lesions. Sixty-six percent of the diabetic foot ulcer lesions had culture-proven bacterial infections compared with 19% of the lesions were affected with Candida and Malassezia yeasts [Figure 2] as well as 7 (14.8%) of these type lesions were found to be sterile. The most common fungal pathogen isolated from DM lesions was the genus Candida, so that Candida albicans (43.3%), Candida glabrata (16.6%), and Malassezia sp. (6.66%) were the most isolated yeasts, followed by the opportunistic molds; A. flavus (23.3%), A. niger (6.66%), and A. terreus (3.3%) [Table 2].

Figure 1.

Diabetic foot ulcer

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participants with positive fungal infections

Figure 2.

Candida albicans and Candida glabrata on CHROMagar candida

Table 2.

Yeasts and molds isolated from the lesions of diabetic patients

Susceptibility testing carried out on 18 representative isolates (13 C. albicans, five C. glabrata) revealed that four isolates (22.2%) were susceptible (MIC, ≤8 mg/ml) to FCZ while 2 C. glabrata isolates in diabetic foot ulcers (11.11%) were (S-DD, MIC 16–32 mg/ml) and 12 isolates (ten C. albicans and two C. glabrata isolates) (66.6%) were resistant (MIC ≥64 mg/ml) to FCZ. Five of these isolates were recovered with diabetic foot ulcers and seven resistant isolates from skin and nail lesions. Likewise, eight isolates (80%) of Aspergillus spp. were resistant (MIC ≥4 mg/ml), one isolate (10%) was intermediate (MIC 2–4 mg/ml), and one isolate (10%) was susceptible (MIC ≤1) to ITC.

Discussion

The present study exhibited a high frequency of fungal infection in diabetic and diabetic foot ulcer patients. Fungal infections are usually neglected aspects of cutaneous lesions in DM patients. Our findings indicated more than 80% of patients with diabetic foot ulcers had a history of trauma and burns, and more than 50% of them had neuropathic ulcers. In our study, C. glabrata showed the highest rate of intermediate susceptibility to the FCZ. Trauma and burns with an impaired leukocyte functions in diabetic patients with poorly controlled diabetes could be the risk factors for the high prevalence of fungal infection.[14,15,16] In Seattle, 46% of the amputations were related to ischemia, 59% to infection, 61% to neuropathy, 81% to faulty wound healing, 84% to ulceration, 55% to gangrene, and 81% to initial minor trauma.[17]

At the present study, we found two clinical isolates from diabetic patients had moderate resistance to FCZ. The lower sensitivity of Iranian isolates from DM patients and their increased MIC patterns of antifungal agents may be related to the geography of the subject population, the environment of the lesion and microbial flora that exist in the lesions. Meanwhile, the type of diabetes were significant in both diabetic foot ulcer or skin and nail groups with fungal infections, but the average duration of diabetes, age, weight, and the history of having underlying disease were not significantly different [Table 1]. In the present study, T2D was the most common type for skin and nail lesions whereas T1D was the most common type in foot ulcers patients. Surveillance studies indicate that azole-resistance is increasing in yeast species, and several alterations of the gene encoding 14-demethylase (ERG11/cyp51) have been reported for FCZ-resistant clinical isolates of C. albicans.[18,19] In the recent decade, there has been a significant increase in infections caused by non-albicans species of Candida, particularly, C. glabrata and C. krusei.[20] The greatest concern for FCZ resistance is related to C. glabrata and in the current study; we found two C. glabrata isolates with moderate resistance to FCZ (susceptibles dosis dependiente) in diabetic foot ulcers.

From a total of 100 DM patients in Delhi, 64% showed one or more cutaneous manifestations. They reported 11 patients with dermatophytosis, two patients with candidal intertrigo and one patient with candidal paronychia.[21] However, at the present study, frequency of fungal infection was 19.1% in patients with diabetic foot ulcer and 28% of patients with skin and nail lesions. Bansal et al., in 2008, evaluated a range of microbial flora in diabetic foot ulcer in India. They found about 91% and 9% of the lesions were affected by bacteria and fungi, respectively.[22] We found twice more yeast infections in diabetic foot ulcers in Isfahan, and the same results were reported by Saba et al. in another province of Iran in 2008.[23] Our findings described the genus Candida, and particularly C. albicans has been the most predominantly isolated fungus from diabetic foot ulcers like the other reports from India and Iran.[22,23] In another study done in Zagreb, Candida parapsilosis was identified as prominent yeast in these type of lesions.[24] In a study done by Lugo-Somolinos and Sánchez was showed that 31% of dermatophytosis diabetic patients had culture-proven fungal infections compared with 33% of the control group.[25] In our study, although dermatophytosis was not found among the75 DM patients with skin and nail lesions but fungal infection was found in 19.1% patients with diabetic foot ulcer. However, from the total of 122 DM patients, 30 (24.5%) of the yeasts (Candida, Malassezia) and the molds Aspergillus spp. were identified [Table 2]. Literature data on the frequency of fungal infection on different type of cutaneous lesions is significantly different. Gupta et al. showed that diabetic patients with onychomycosis were more at risk for diabetic ulcers and gangrene (12.2%) than normal individuals with onychomycosis.[26] Table 2 shows C. albicans is the most common yeast isolated from the diabetic foot ulcer, skin and nail lesions and A. flavus was the most prominent causative agent of onychomycosis in DM patients in Isfahan. Dorko et al., in a study on DM patients in Slovakia, found that C. albicans was the most frequent yeast in patients with onychomycosis followed by C. parapsilosis.[27] A literature review about determining the antifungal sensitivity of the isolates from cutaneous and diabetic foot ulcers are very scarce; however, in a study done on the yeasts isolated from oral lesions from diabetic and nondiabetic subjects; no differences were observed in antifungal susceptibility of the six agents tested between Candida isolates. The authors describe the difference in the antifungal resistance of the isolates from the two populations of DM patients may be related to the differences in the therapeutic management of candidal infections between the two local areas.[28] Choice of appropriate treatment and correct monitoring of fungal cutaneous infections can prevent significant morbidity in patients with diabetes. Terbinafine and ITC have been used to treat onychomycosis in DM patients have efficacy and safety profiles comparable to those in the nondiabetic population.[29] No breakpoints are established for Aspergillus sp. susceptibility is defined as ≤2 mg/L for ITC.

Conclusion

Our findings showed high prevalence of fungal infection in diabetic and diabetic foot ulcer patients, and C. albicans was the prominent fungus isolated from these patients. Wise consideration of the possibility of fungal infections, early recognition, and appropriate treatment ensure rapid healing and eliminate amputation risk, minimize mortality, and costs.

Financial support and sponsorship

Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Grant No: 393366).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Murphy-Chutorian B, Han G, Cohen SR. Dermatologic manifestations of diabetes mellitus: A review. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2013;42:869–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larijani B, Zahedi F. Epidemiology of diabetes mellitus in Iran. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2002;1:7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh N, Armstrong DG, Lipsky BA. Preventing foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. JAMA. 2005;293:217–28. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rangel-Guerra R, Martínez HR, Sáenz C. Mucormycosis. Report of 11 cases. Arch Neurol. 1985;42:578–81. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1985.04060060080013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehrer RI, Howard DH, Sypherd PS, Edwards JE, Segal GP, Winston DJ. Ann Intern Med. 93.5th ed. 1980. Mucormycosis; pp. 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romano G, Moretti, Di Benedetto A, Giofrè C, Di Cesare E, Russo G, et al. Skin lesions in diabetes mellitus: Prevalence and clinical correlations. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1998;39:101–6. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(97)00119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakker K, Riley P. The year of the diabetic foot. Diabetes Voice. 2005;50:11–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aye M, Masson EA. Dermatological care of the diabetic foot. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:463–74. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200203070-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chellan G, Shivaprakash S, Karimassery Ramaiyar S, Varma AK, Varma N, Thekkeparambil Sukumaran M, et al. Spectrum and prevalence of fungi infecting deep tissues of lower-limb wounds in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2097–102. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02035-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rex J, Alexander B, Andes D, Arthington-Skaggs B, Brown S, Chaturveli V. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; approved standard – Third edition (M27-A3) Vol. 28. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espinel-Ingroff A, Dawson K, Pfaller M, Anaissie E, Breslin B, Dixon D, et al. Comparative and collaborative evaluation of standardization of antifungal susceptibility testing for filamentous fungi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:314–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.2.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Espinel-Ingroff A, Fothergill A, Ghannoum M, Manavathu E, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Pfaller M, et al. Quality control and reference guidelines for CLSI broth microdilution susceptibility method (M 38-A document) for amphotericin B, itraconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5243–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.10.5243-5246.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfaller MA. Antifungal drug resistance: Mechanisms, epidemiology, and consequences for treatment. Am J Med. 2012;125(1 Suppl):S3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borzotta AP, Beardsley K. Candida infections in critically ill trauma patients: A retrospective case-control study. Arch Surg. 1999;134:657–64. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.6.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Church D, Elsayed S, Reid O, Winston B, Lindsay R. Burn wound infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:403–34. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.2.403-434.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delamaire M, Maugendre D, Moreno M, Le Goff MC, Allannic H, Genetet B. Impaired leucocyte functions in diabetic patients. Diabet Med. 1997;14:29–34. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199701)14:1<29::AID-DIA300>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pecoraro RE, Reiber GE, Burgess EM. Pathways to diabetic limb amputation. Basis for prevention. Diabetes Care. 1990;13:513–21. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.5.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vandeputte P, Larcher G, Bergès T, Renier G, Chabasse D, Bouchara JP. Mechanisms of azole resistance in a clinical isolate of Candida tropicalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4608–15. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4608-4615.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brun S, Bergès T, Poupard P, Vauzelle-Moreau C, Renier G, Chabasse D, et al. Mechanisms of azole resistance in petite mutants of Candida glabrata. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1788–96. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1788-1796.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krcmery V, Barnes AJ. Non-albicans Candida spp. causing fungaemia: Pathogenicity and antifungal resistance. J Hosp Infect. 2002;50:243–60. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2001.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahajan S, Koranne RV, Sharma SK. Cutaneous manifestation of diabetes mellitus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:105–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bansal E, Garg A, Bhatia S, Attri AK, Chander J. Spectrum of microbial flora in diabetic foot ulcers. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2008;51:204–8. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.41685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saba F, Hadi SM, Rabe’eh F, Javad NM, Monavvar A, Mohsen G, et al. Mycotic infections in diabetic foot ulcers in Emam Reza Hospital, Mashhad, 2006-2008. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2011;4:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mlinariæ-Missoni E, Kaleniæ S, Vukeliæ M, De Syo D, Belicza M, Vaziæ-Babiæ V. Candida infections in diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetol Croat. 2005;34:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lugo-Somolinos A, Sánchez JL. Prevalence of dermatophytosis in patients with diabetes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:408–10. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70063-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta AK, Konnikov N, MacDonald P, Rich P, Rodger NW, Edmonds MW, et al. Prevalence and epidemiology of toenail onychomycosis in diabetic subjects: A multicentre survey. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:665–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dorko E, Baranová Z, Jenca A, Kizek P, Pilipcinec E, Tkáciková L. Diabetes mellitus and candidiases. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2005;50:255–61. doi: 10.1007/BF02931574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manfredi M, McCullough MJ, Polonelli L, Conti S, Al-Karaawi ZM, Vescovi P, et al. In vitro antifungal susceptibility to six antifungal agents of 229 Candida isolates from patients with diabetes mellitus. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2006;21:177–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2006.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayser P, Freund V, Budihardja D. Toenail onychomycosis in diabetic patients: Issues and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:211–20. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200910040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]