Abstract

Diploid budding yeast undergoes rapid mitosis when it ferments glucose, and in the presence of a non-fermentable carbon source and the absence of a nitrogen source it triggers sporulation. Rich medium with acetate is a commonly used pre-sporulation medium, but our understanding of the molecular events underlying the acetate-driven transition from mitosis to meiosis is still incomplete. We identified 263 proteins for which mRNA and protein synthesis are linked or uncoupled in fermenting and respiring cells. Using motif predictions, interaction data and RNA profiling we find among them 28 likely targets for Ume6, a subunit of the conserved Rpd3/Sin3 histone deacetylase-complex regulating genes involved in metabolism, stress response and meiosis. Finally, we identify 14 genes for which both RNA and proteins are detected exclusively in respiring cells but not in fermenting cells in our sample set, including CSM4, SPR1, SPS4 and RIM4, which were thought to be meiosis-specific. Our work reveals intertwined transcriptional and post-transcriptional control mechanisms acting when a MATa/α strain responds to nutritional signals, and provides molecular clues how the carbon source primes yeast cells for entering meiosis.

Biological significance

Our integrated genomics study provides insight into the interplay between the transcriptome and the proteome in diploid yeast cells undergoing vegetative growth in the presence of glucose (fermentation) or acetate (respiration). Furthermore, it reveals novel target genes involved in these processes for Ume6, the DNA binding subunit of the conserved histone deacetylase Rpd3 and the co-repressor Sin3. We have combined data from an RNA profiling experiment using tiling arrays that cover the entire yeast genome, and a large-scale protein detection analysis based on mass spectrometry in diploid MATa/α cells. This distinguishes our study from most others in the field—which investigate haploid yeast strains—because only diploid cells can undergo meiotic development in the simultaneous absence of a non-fermentable carbon source and nitrogen. Indeed, we report molecular clues how respiration of acetate might prime diploid cells for efficient spore formation, a phenomenon that is well known but poorly understood.

Keywords: Proteome, Transcriptome, Fermentation, Respiration, Ume6 Rim4

1. Introduction

Budding yeast is an important model organism for biochemical studies, genetic analyses and genomic profiling of cell growth and division, and cell differentiation [1–3]. In addition, it is useful for the field of toxicogenomics, which investigates the cellular response to environmental stressors and drugs; [4,5], reviewed in [6].

Saccharomyces cerevisiae was the first eukaryote for which the complete genome sequence was determined (see Saccharomyces Genome Database, SGD) [7,8]. The protein-coding part of the yeast genome includes verified genes, which are conserved open reading frames (ORFs) typically associated with a biological process, uncharacterized genes, which play no known roles, and dubious genes, which are assumed not to encode functional proteins [8]. The yeast transcriptome has been studied in numerous conditions using microarrays and RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) [9–12]. Furthermore, protein-profiling experiments detected nearly all theoretically predicted yeast proteins in pre-fractionated extracts from growing cells [13,14]. Very recent feasibility studies reported vastly improved experimental protocols yielding quantitative information about protein concentrations in total cell extracts [15–17].

To produce the metabolite adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is critical for storing chemical energy, yeast cells process fermentable and non-fermentable carbon sources by activating distinct metabolic pathways. Fermentation of sugars such as glucose and fructose is efficient and down-regulates enzymes required for metabolizing alternative carbon sources via a process called carbon catabolite repression; reviewed in [18]. Fermentation leads to the accumulation of glycerol and ethanol, which are further processed via oxidation. When yeast cells are cultured in rich medium in the presence of the two-carbon compound acetate, they use the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and the glyoxylate cycle for energy production [19,20]. Previous analyses of yeast cell growth under highly controlled conditions limited for carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and sulphur revealed that both transcriptional control and post-translational regulation mechanisms play roles in the response to nutrient starvation [21–23]. Fermentation and respiration are not only relevant for understanding yeast growth and development but also for human diseases; for example, the so-called Warburg effect has been observed in tumor cells that excessively ferment glucose into lactate [24].

Ume6 is the DNA binding subunit of two conserved repressor complexes including either the histone deacetylase (HDAC) Rpd3 and the co-repressor Sin3 [25,26], or the chromatin-remodeling factor Isw2 [27]. Ume6 was initially identified as a mitotic repressor for early meiosis-specific genes, and later shown to orchestrate metabolic functions, stress response, and the onset of meiotic differentiation [28–30]. Among others, Ume6 directly represses SIP4, which encodes a C6 zinc cluster transcriptional activator involved in gluconeogenesis, during growth in the presence of glucose [30,31]. Ume6 becomes unstable when vegetatively growing cells switch from metabolizing glucose to processing acetate, and is temporarily degraded during meiosis by the anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C), before it accumulates again at later stages of spore formation [32,33].

In earlier work we have developed Direct Iterative Protein Profiling (DIPP) to comprehensively analyze the proteome of fermenting diploid yeast cells in a cost-effective manner by widely available standard mass spectrometry [34]. In the present study we report the changes in the proteome of diploid MATa/α yeast cells undergoing logarithmic growth in rich medium with fermentable glucose (YPD) or non-fermentable acetate (YPA) in the context of corresponding RNA-profiling data from wild-type cells and a ume6 mutant strain. This approach enabled us to gain insight into molecular events that underlie the switch from fermentation to respiration, and that prime diploid MATa/α cells for the transition from mitotic growth to meiotic differentiation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Culture conditions for protein profiling

Samples from YPD (yeast extract, peptone and dextrose) were cultured as published [34]. In addition, cells grown in YPD were transferred into 100 ml YPA (rich medium with acetate) pre-warmed to 30 °C at a cell density of 2 × 106 cells/ml and cultured until they reached 3 × 107 cells/ml, before they were harvested in two 50 ml aliquots and washed with sterile water. The pellets were then snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

2.2. Construction of gene deletion strains

To reduce the chance of unlinked mutations affecting the growth experiments, both copies of target genes were deleted in homozygous diploid cells. Most deletions were made in the BY4743 background using the method as published [35]. Three deletions were made in the related strain JHY222 [36].

2.3. Plate growth assays

To monitor the growth phenotype of deletion strains we used two methods. Homozygous diploid strains were streaked on YD/G418 and grown at 30 °C for three days. Single colonies from each strain were suspended in water and diluted to approximately 100 cells/μl. 4 μl of cell suspension was spotted onto YPD and YPEG (ethanol, glycerol) plates and incubated at 30 °C for two days (YPD) and three days (YPEG). Alternatively, strains were re-streaked for single colonies on YPD, YPA and YPEG plates, and incubated at 30 °C for three days (YPD) or four days (YPA, YPEG).

2.4. Protein detection by immunofluorescence

Rim4 immunostaining was done as described [37]. Briefly, cells were fixed in 70% ethanol for 1 h at room temperature, washed with PBS and incubated for 60 min at 37 °C with a mouse anti-V5 monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen, USA) diluted 1:200 in 1× PBS 0.1% Tween 20. Cells were washed three times for 3 min each with 1× PBS 0.1% Tween 20 and incubated with a secondary Alexa Fluor 488 Goat Anti-Mouse antibody (Invitrogen) diluted 1:10,000 in 1× PBS. Cells were again washed and mounted in Antifade solution (Vector Laboratories) containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 1 μg/ml) to stain DNA. Acquisition of images was done using a Zeiss AxioImager M1 microscope equipped with an AxioCam MRC5 camera controlled by AxioVision 4.7.1 software using standard settings (Zeiss, Le Pecq, France).

2.5. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

Ume6/DNA complexes formed in vivo were precipitated using a standard assay with SK1 cells cultured in rich medium (YPD). A 50 ml mid-log culture was cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Cross-linked Ume6/DNA complexes were quenched with 140 mM glycine (Sigma, USA) for 5 min, collected, washed and eluted before reversing crosslinks. Finally, DNA was precipitated, digested with proteinase K and amplified by Q-PCR as published. Relative ChIP signals were calculated using the formula (2^-IP (CT target − CT control)/input (CT target − CT control)). The NUP85 coding region was used as an internal control [32,38].

2.6. Protein extraction, sample pre-fractionation and peptide analysis by mass spectrometry

Duplicate samples from YPA were pre-fractionated, and the samples were analyzed using DIPP as published [34]. Data were analyzed using the Proteome Discoverer 1.2 software in conjunction with Mascot (Matrixscience) and SEQUEST database search engines to identify peptides and proteins. In the first step the MS/MS spectra were compared to annotation data for budding yeast proteins (Saccharomyces Genome Database release 06/01/2010) [8]. The mass tolerance for MS and MS/MS was set at 10 ppm and 0.5 Dalton. Trypsin selectivity was set to full, with one miss cleavage possible. The protein modifications were fixed carbamidomethylation of cysteines, variable oxidation of methionine, variable acetylation of lysine and variable phosphorylation of serine, threonine and tyrosine. Peptides identified were selected via Xcorr values and the Mascot score to achieve a false discovery rate of 1% and a false positive rate of 5%. We used Proteome Discoverer to assemble peptides detected in the first and second run, which are then masked in subsequent LC-MS/MS analyses. Before the third analysis step was executed, we combined peptide exclusion files from the first two runs. Peptides that were not masked were exported as a text file containing uncharged and accurate mass values (at five decimals) and a retention time window of approximately 1 min. The instrument was set to function with uncharged masses and to calculate the mass of a peptide based on its exact mass and charge state. A mass tolerance of ±10 ppm was employed to filter out peptides already identified within the specified retention time window.

2.7. Minimum Information About a Proteomics Experiment (MIAPE) compliance

The mass spectra and search result data files are available for downloading at the Yeast Resource Center Public Data Repository (YRC PDR) via www.yeastrc.org/pdr/becker2014/ [39].

2.8. Culture conditions for RNA profiling

Triplicate samples of SK1 wild-type and ume6 mutant strains were cultured in YPD, YPA and SPII using standard media and conditions [30,40].

2.9. Probe synthesis, GeneChip hybridization and scan

RNA profiling with Yeast Genome 2.0 GeneChips was done as published [41].

2.10. Differential expression analysis of wild-type versus ume6 mutant strains

To identify up-regulated genes in ume6 mutant we first performed a quantile normalization and then selected genes for which the expression level was above the 25th percentile (9.006) in at least one condition, and that showed a fold-change >2 between mutant and wild-type. A limma test with a False Discovery Rate (FDR) 5% was done to identify genes differentially expressed and up-regulated in the ume6 mutant. The statistical filtration was done using R [42,43].

2.11. Tiling array expression data integration

DNA-strand specific whole-genome expression data obtained with tiling arrays and duplicate samples from diploid SK1 cells cultured in rich medium (YPD) and rich medium with acetate (YPA) were integrated and compared to the mass spectrometry measurements; data processing methods and expression threshold level parameters were as published [36]. For each gene annotated in the reference genome, we selected the segments derived from Sc_tiling experiments, which overlapped its coordinates, and computed an average value for the gene. Therefore, each segment’s contribution to the overall signal is proportional to its overlap with the corresponding gene. Equivalent values were computed for overlapping anti-sense transcripts for each gene. Genes were organized into 11 clusters, and for each gene (as represented by segments) we extracted the list of the clusters it was associated with.

2.12. Microarray expression data

Expression signals were obtained with Affymetrix DNA-strand specific tiling arrays (Sc_tlg) from reference [36].

2.13. Regulatory motif prediction

The URS1 motif was predicted using the published Promoter Analysis Protocol (PAP) [44].

2.14. Global genomics data integration

Information about protein and genes and the Gene Ontology annotation data were down-loaded from SGD [8]. The relative abundance data of proteins expressed in log-phase growth were extracted from the quantitative Western blot analysis of TAP-tagged strains available via SGD (http://yeastgfp.yeastgenome.org/) [45]. Phosphorylated site predictions were extracted from [46]. Genome annotation data for haploid S288c and SK1 strains were used as published [34].

2.15. Identifying target genes showing a similar pattern as the reference genes

We filtered genes similar to KGD1, MDH1, MDH2, SDH1, FUM1, IDH1, ACO1, CIT1, MLS1, and ICL1 whereby (i) the target genes were expressed above the background (BG) = 5.99 in YPD and YPA, (ii) the fold change between expression in YPD and YPA was >2.0, (iii) the log-expression in YPA was >12, and (iv) we observed >3-fold more bands to contain the protein in YPA than YPD.

2.16. Gene Ontology enrichment analysis

We performed the GO enrichment analysis with the GOToolBox [47], using a hypergeometric law and a Benjamini and Hochberg correction for multiple testing. Biological Process GO annotations with corrected p-values <0.01 were selected.

2.17. Identification of proteins detected specifically in YPA

We selected proteins for which peptides were found only in YPA but not YPD classified the genes, which encode them into loci, which are not significantly differentially expressed in YPD and YPA, which are differentially expressed in YPD and YPA, with a fold-change >1.5 as assessed by a linear models for microarray data (LIMMA) statistical test with FDR = 5%, and genes, which are expressed < BG = 5.99 in YPD and > BG = 5.99 in YPA, with a fold-change >1.5 as assessed by a limma statistical test with FDR = 5% [42,43].

3. Results

3.1. Experimental design

To determine the proteome in the presence of glucose or acetate we combined previously published DIPP data on rapid growth in rich medium with glucose (YPD) [34], with a new dataset from cells cultured in a medium where glucose was replaced by acetate (YPA). We included published RNA profiling data from YPD and YPA samples that were analyzed with tiling arrays (Sc_tlg) [36]. We previously reported that SIP4, CAT8 and ADR1—which encode transcription factors involved in gene expression during the diauxic shift—are strongly de-repressed in a ume6 mutant (GeneChip expression data are shown in www.germonline.org; [48]) [49]. Since a large-scale in vivo protein–DNA interaction study showed that Ume6 binds to their promoters (ChIP-Chip in vivo binding data are shown in www.germonline.org) [31], we investigated the role of the Rpd3/Sin3/Ume6 regulatory complex in respiring diploid cells. To this end, we used expression data from UME6 wild-type cells and a ume6 mutant strain (Lardenois, Walther, Becker et al., in preparation; the complete dataset will be published elsewhere). The transcriptome and proteome data were then integrated with functional genomics data [4,8,50]. To allow for direct comparison with previous studies, we have employed standard flask culture conditions for asynchronous cell division in rich media with glucose or acetate—the latter is used as a non-fermentable carbon source in pre-sporulation growth medium [40,51,52]—and cell differentiation in sporulation medium.

3.2. The proteome of diploid budding yeast during fermentation and respiration

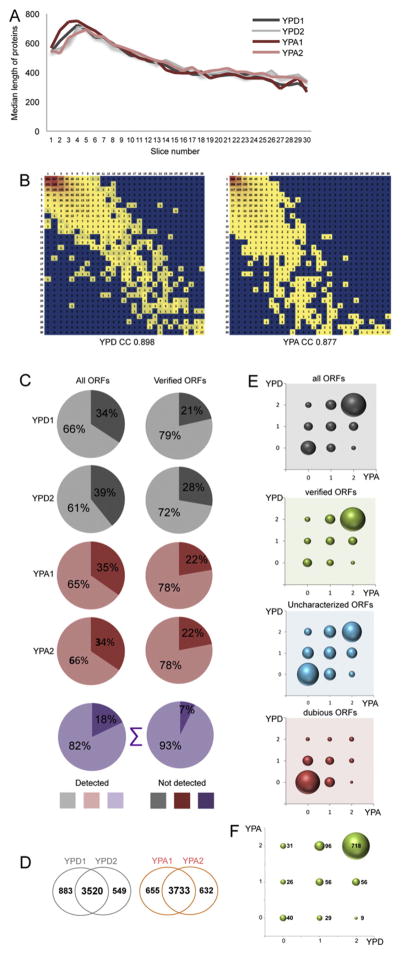

Like in earlier work on the proteome of cells cultured in YPD [34], we found that protein size and migration speed in the gel—that is, protein presence in gel slices 1 (top) to 30 (bottom)—are correlated similarly across YPA replicates (Fig. 1A, Table 3). We also observed that the number of bands a protein was present in was highly reproducible in both media (correlation coefficient r2 0.898 in YPD and 0.877 in YPA; Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

The proteome of fermentation and respiration. (A) Protein length in amino acids (y-axis) is plotted against the gel slice number (x-axis) for the color coded samples as shown (B) The number of proteins reproducibly found in gel slices 1–30 are plotted. (C) Pie charts show the percentages of proteins encoded by all open reading frames (ORFs) or verified ORFs for rich medium with glucose (YPD) in grey, for rich medium with acetate (YPA) in red, and for the total number of proteins in violet. (D) Venn diagrams show the numbers of proteins detected in sample replicates. (E) Color coded bubble charts show the patterns of detection (0 means not detected, 1 signifies that the protein was detected in one replicate, 2 means that it was detected in both replicates) in YPD (y-axis) versus YPA (x-axis). Data are given in grey for all ORFs, in green for verified ORFs, in blue for uncharacterized ORFs, and in red for dubious ORFs. (F) A bubble chart shows the detection pattern in YPD replicates (x-axis) versus YPA samples (y-axis) for proteins known to localize to mitochondria like in panel E.

Table 3.

Protein detection patterns versus gene annotation and protein length.

| YPD | YPA | Average length (all ORFs) | Average length (verified ORFs) | Median length (all ORFs) | Median length (verified ORFs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 234 | 309 | 126 | 247 |

| 0 | 1 | 308 | 376 | 212 | 335 |

| 0 | 2 | 416 | 443 | 370 | 412 |

| 1 | 0 | 327 | 393 | 229 | 346 |

| 1 | 1 | 388 | 434 | 349 | 417 |

| 1 | 2 | 482 | 502 | 416 | 447 |

| 2 | 0 | 361 | 389 | 338 | 353 |

| 2 | 1 | 471 | 496 | 422 | 451 |

| 2 | 2 | 576 | 581 | 468 | 476 |

By combining data obtained with cells cultured in rich media with glucose or acetate we detected 5513 out of 6713 predicted proteins in at least one of the four samples (82%, taking verified, uncharacterized and dubious genes into account). More specifically, we found 4517 of 4877 proteins encoded by verified genes (93%; Table 1, Fig. 1C). Among 4952 proteins detected in YPD, 3520 were found in both samples, while 883 and 549 were detected only in YPD1 or YPD2, respectively. Likewise, among 5020 protein scored as present in YPA, 3733 were reproducibly detected, while 655 and 632 were present only in replicates 1 or 2 (Fig. 1D). As expected, the vast majority of verified ORFs encode proteins, which are expressed highly enough to be detected in almost all samples, while the output among uncharacterized genes is split into two major groups that are either reproducibly detected, or that are undetectable in the experimental conditions used (Table 2, Fig. 1E).

Table 1.

Gene annotation versus protein detection.

| Annotation | YPD1 | YPD2 | YPA1 | YPA2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All yeast ORFs | 4416 | 4079 | 4379 | 4400 |

| Verified ORFs | 3833 | 3525 | 3793 | 3804 |

| Uncharacterized ORFs | 444 | 396 | 441 | 437 |

| Dubious ORFs | 117 | 139 | 126 | 142 |

Table 2.

Reproducibility of protein detection versus gene annotation.

| YPD | YPA | All ORFs | Verified | Uncharacterized | Dubious |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1090 | 356 | 266 | 491 |

| 0 | 1 | 368 | 198 | 74 | 90 |

| 0 | 2 | 175 | 131 | 30 | 13 |

| 1 | 0 | 381 | 207 | 77 | 85 |

| 1 | 1 | 504 | 335 | 85 | 59 |

| 1 | 2 | 547 | 446 | 82 | 16 |

| 2 | 0 | 94 | 67 | 20 | 7 |

| 2 | 1 | 415 | 331 | 61 | 20 |

| 2 | 2 | 3011 | 2769 | 215 | 20 |

In the case of dubious ORFs we detect few proteins, which is in keeping with the notion that many of these loci are annotation artefacts. However, we note that 20 proteins encoded by dubious ORFs are detected in all four YPD/YPA samples (Fig. 1E, Supplemental file S1, Class 1 detection pattern, filter for “dubious”). Among them, Yjr146w was detected in an earlier protein profiling study [45] and two other proteins may be involved in cell aging (Yim2 [53]) or drug-resistance (Imd1 [54]). For eight dubious ORFs we also detect corresponding mRNAs: YMR173W-A almost entirely overlaps DDR48; weak expression of mRNA was observed for YBL071C, YCR013C, YHR056W-A, YLR339C, YMR075C-A and YPR197C and YMR304C-A appears to be co-expressed with the partially overlapping SCW10 locus. In the cases of YAL016C-B, YBR191W-A, YKL165C-A, YLR163W-A, YMR052C-A, YNL319W and YPR136C no expression signals were observed with tiling arrays; these cases are either false positive peptide scores or the transcript levels are below the threshold level of detection of tiling arrays.

Among approximately 1000 proteins known to localize to mitochondria we detect the majority (718) in all samples; notably, 57 proteins are scored as present only in cells grown in YPA (including 31 that are detected in both YPA replicates). To the contrary, only 9 proteins were found exclusively in cells cultured in YPD (Fig. 1F).

We conclude that DIPP detects the vast majority of known yeast proteins and that growth in acetate increases the protein content of mitochondria in accordance with their metabolic role in respiration [55–57]. Finally, the group of dubious ORFs may represent an opportunity for the discovery of genes involved in vegetative growth.

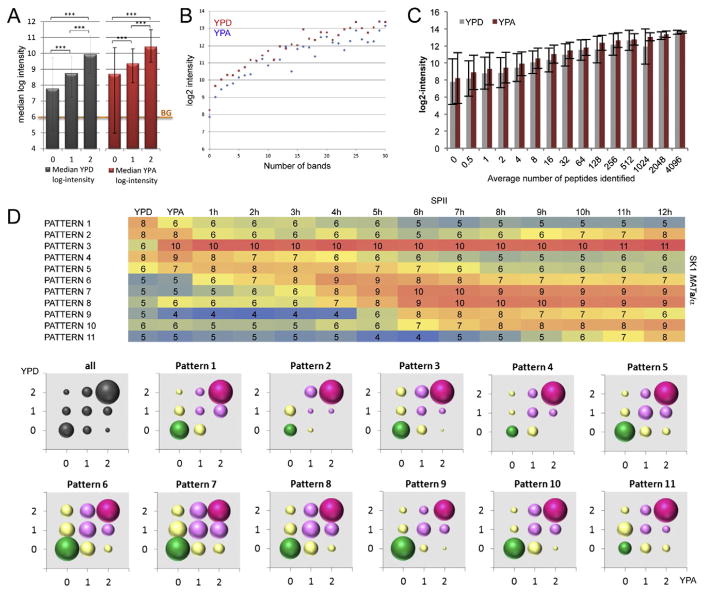

3.3. Comparing expression levels and protein detection patterns in diploid MATa/α cells

We subsequently asked if DIPP’s capacity to detect a protein was related to the overall expression level of the corresponding gene, and found that the median intensities of log-transformed microarray expression signals increase with the number of samples in which the proteins are detected by DIPP in cells cultured in YPD or YPA (Fig. 2A). Gene expression values are also positively correlated with the number of bands a protein is detected in, and the average number of peptides identified (Fig. 2B, C). To further correlate gene expression and protein function, we compared protein profiles in YPD and YPA media with mRNA concentrations during fermentation (YPD), respiration (YPA) and sporulation (SPII hourly time points from 1 to 12) using our published tiling array data from SK1 MATa/α wild-type cells [36]. Consistently, we found that proteins encoded by genes showing peak expression in cells undergoing mitotic divisions tend to be reproducibly detected in one or both growth media (Fig. 2D, patterns 1–4). On the contrary, proteins encoded by genes for which mRNA synthesis is induced during early, middle and late stages of meiosis and gametogenesis, are not—or at least not reproducibly—detected in mitotic cells (Fig. 2D, patterns 5–10). It is unclear why in the case of very late sporulation genes the DIPP pattern is slightly shifted toward protein detection again; perhaps it reflects the fact that certain proteins play roles during mitotic growth and spore formation (Fig. 2D, pattern 11).

Fig. 2.

The correlation between gene expression and protein detection. (A) A color-coded bar diagram shows median log microarray signal intensities (y-axis) for proteins that were not detected (0), detected in one replicate (1), or detected in both replicates (2) in YPD and YPA (x-axis) in grey and red, respectively. An orange line shows the background (BG) threshold signal. (B) log2-transformed intensity values (y-axis) are plotted against the number of gel slices (x-axis) proteins were detected in for YPD (red) and YPA (blue). (C) A bar diagram shows the average log intensity (y-axis) versus the average number of peptides identified (x-axis) in YPD (grey) and YPA (red). The standard deviation is indicated. (D) A heatmap shows the microarray gene expression profiles (1–11) ordered over peak signals. Log-transformed values are color-coded (blue indicates low signals and red indicated high signals). Rich media (YPD, YPA) and hourly time points in sporulation medium (SPII) are given at the top. The strain is indicated to the right. Color-coded bubble charts summarizing protein detection patterns are shown like in Fig. 1E for 11 expression patterns as indicated.

3.4. Transcriptional regulation versus post-transcriptional control during fermentation and respiration

We first asked if proteins important for metabolizing acetate showed correlated profiles of mRNA induction and protein accumulation. To address this question, we determined the mRNA/protein patterns underlying the switch from processing glucose to metabolizing acetate in the cases of genes essential for the process. We selected 10 reference proteins required for respiration, and found them both in fermenting and respiring cells (Fig. S1A and Table 4) [8]. Subsequently, we selected 60 genes, which show RNA/protein patterns similar to the reference genes (Fig. S1B). Gene Ontology terms enriched in this group point to metabolic processes (cellular respiration, p-value 1.45 × 10−7; carboxylic acid metabolic process, 1.24 × 10−24), and a response to nutritional cues (nitrogen compound biosynthetic process, 3.52 × 10−7; Fig. S1C). We next assayed genes involved in mitochondrial inheritance and function (AIM41, YCP4), the TCA cycle (LSC2), ethanol metabolism (ADH2), iron transport (FTH1), cell structure (CWP1), stress response (CMK2, LSB3, YJR085C), and possibly respiration (Ypr010c-a via interaction with Fcj1 [58]) for growth on a non-fermentable carbon source. However, none of them failed to grow on YPA and YEPG media after incubation at 30 °C; FUM1, ACO1, OM14 and PTH1 were used as positive controls (Fig. S1D). We conclude that proteins important for growth on acetate are not necessarily present only in respiring cells but already accumulate during fermentation.

Table 4.

Reference gene expression and protein abundance.

| ORF | Length (aa) | YPD (log2) | YPA(log2) | 2|YPA – YPD| | No slices in YPA | No slices in YPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDH2 | 377 | 8.14 | 13.37 | 37.5 | 1.5 | 29 |

| ICL1 | 557 | 8.19 | 13.81 | 49.2 | 17 | 29 |

| MLS1 | 554 | 6.63 | 13.46 | 113.8 | 12 | 29.5 |

| SDH1 | 640 | 10.07 | 12.83 | 6.8 | 17.5 | 26 |

| FUM1 | 488 | 11.19 | 13.07 | 3.7 | 18 | 26 |

| ACO1 | 778 | 12.01 | 13.17 | 2.2 | 27.5 | 30 |

| MDH1 | 334 | 11.29 | 12.77 | 2.8 | 15.5 | 23 |

| CIT1 | 479 | 9.76 | 13.2 | 10.8 | 20.5 | 28 |

| IDH1 | 360 | 11.56 | 13.14 | 3.0 | 16.5 | 21 |

| KGD1 | 1014 | 10.4 | 12.57 | 4.5 | 21 | 27.5 |

Ume6 coordinates the transition between cell growth and development, and both its concentration and DNA binding activity decrease when cells are cultured in acetate [30,32,59,60]. To learn more about the transcriptional control mechanisms that contribute to the mitotic regulation of genes differentially expressed during fermentation and respiration we combined URS1 motif predictions with genome-wide expression data from wild-type cells and ume6 mutant cells. We find that likely direct Ume6 targets are induced in YPA. This comprises six genes for which promoters contain known URS1 motifs (ACH1, ACS1, CAT2, GDH2, PRX1, UBI4), and three genes that have promoters containing predicted URS1 elements (ADY2, PRB1, OM14; Fig. S1B and Supplemental file S1). ADY2 encodes a membrane bound acetate permease essential for the packaging of meiotic nuclei into four spores [61,62]. The latter function is apparently specific for Ady2 since no meiotic phenotype was reported for its paralog Ato2 [63]. To validate our motif predictions and the RNA profiling data we confirmed that Ume6 binds to the promoters of ACH1 and ADY2 in vivo using chromatin immunoprecipitation assays. The binding signal intensities were found to be in the same range as the Ume6 targets CAR1 and HOP1 ([28,64,65]; Fig. S1E). Furthermore, ume6 mutants in three different genetic backgrounds fail to grow normally on YPA and—in the case of W303—display increased cell size (Fig. S1F, G) [29]. These findings extend the metabolic role of the Rpd3/Sin3/Ume6 regulator as diploid cells switch from fermentation to respiration.

3.5. Protein profiling reveals that carbon-source specificity is biased toward acetate

We next sought to distinguish genes that are transcription-ally controlled by Rpd3/Ume6, from those that are regulated at the post-transcriptional level when diploid cells switch from fermentation to respiration. We therefore assembled a list of 94 proteins detected only in YPD and 169 proteins found only in YPA and then used tiling array data to filter three groups of YPD/YPA mRNA patterns in each medium.

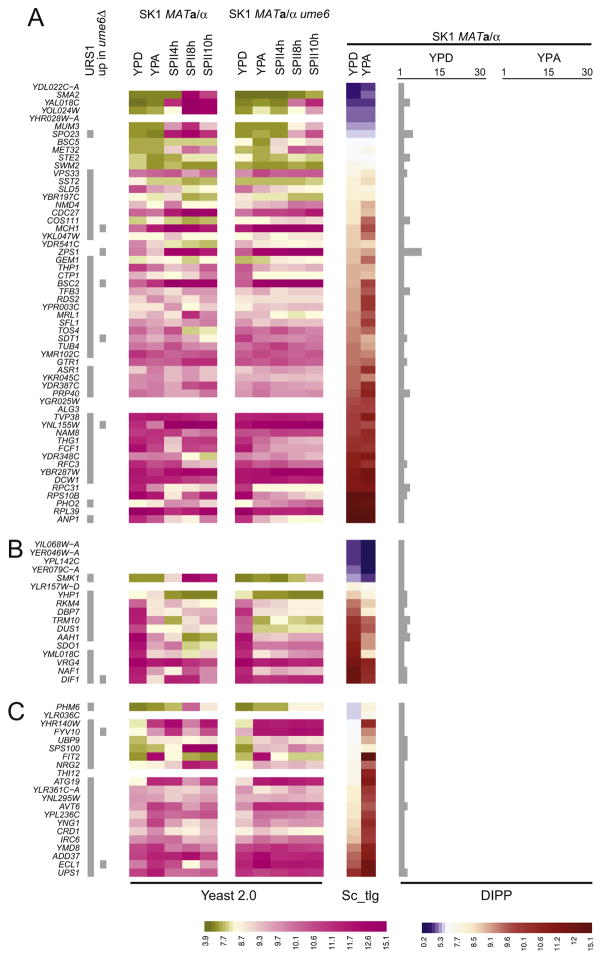

The first YPD-specific group includes 56 genes for which we detect a gradient of similar concentrations (that is, the differences are not statistically significant) in both YPD and YPA (Fig. 3A). This group contains Spo23 (a Spo1 interactor [66]) and Mum3 (spore wall formation [67]), for which weak mRNA signals are detected in YPD [36], and five genes up-regulated in the ume6 mutant (BSC2, MCH1, SDT1, YNL155W, ZPS1).

Fig. 3.

Ume6-target gene profiling and YPD protein/mRNA detection patterns. (A) A color-coded heatmap indicates predicted URS1 motifs (grey squares), and de-repression in a vegetatively growing ume6 mutant (up in ume6Δ). A green to pink color scale indicates gene expression measured by Yeast Genome 2.0 GeneChips in rich media (YPD, YPA), and three time points in sporulation medium (SPII 4 h, 8 h and 10 h) in wild-type (SK1 MATa/α) versus ume6 mutant strains (SK1 MATa/α ume6). The color change was set to be consistent with the tiling array expression background. A blue to red color scale indicates the expression level determined with tiling arrays in YPD and YPA. For proteomic data, the number of bands (from 0 to 30) within which a given protein was detected is summarized in bar diagrams given in light grey. GeneChip data (Yeast Genome 2.0), tiling array data (Sc_tlg), and mass spectrometry data (DIPP) are indicated at the bottom. Scales for Yeast Genome 2.0 (left) and Sc_tlg data (right) are given at the bottom. (B) Data are shown for selected genes that show similar patterns as the reference genes. (C).

The second YPD-specific group comprises 17 genes for which mRNAs coherently peak in rich medium (Fig. 3B). We note the presence of supposedly sporulation-specific Smk1 (MAP kinase required or spore wall assembly [68]) in this group. We also find another gene showing elevated levels during growth in the absence of Ume6 (DIF1).

The third YPD-specific group covers 21 genes for which mRNAs peak in YPA (Fig. 3C). This pattern clearly indicates that transcription and translation and protein stability are uncoupled for these loci. Again, we detect a protein considered to be sporulation-specific (Sps100, involved in spore wall formation [69]), for which tiling array data show clear expression in dividing cells [36].

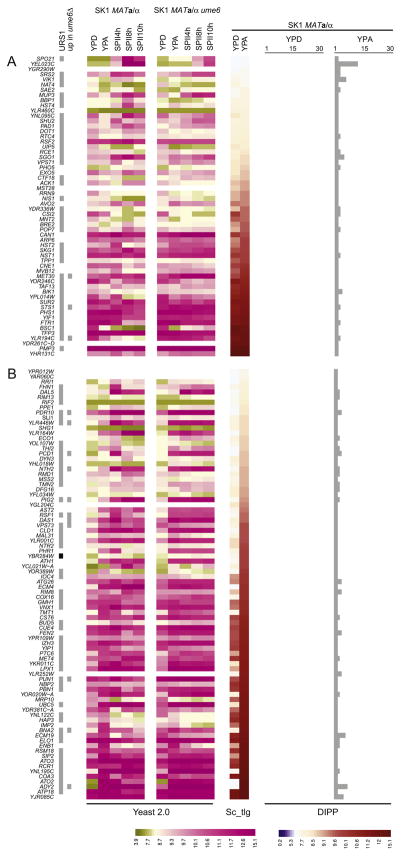

The first YPA-specific group includes 58 genes for which we observe similar mRNA levels across media (Fig. 4A). Among the proteins that accumulate in YPA we found Spo21, which is mainly involved in meiosis specific modification of the spindle pole body, but for which a function in nutrient utilization was also reported [70,71], and Sae2, a protein involved in DNA-damage response and meiotic double strand break repair [72,73]. This group also contains MET30, STS1 and YLR194C, which harbor predicted URS1 motifs in their promoters and are partially de-repressed in acetate in the absence of Ume6 (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Gene expression and Ume6-dependency for proteins detected only in YPA. (A) A color-coded heatmap is given like in Fig. 3 showing proteins detected only in YPA, for which we observe a gradient of similar tiling array signals in YPD and YPA. (B) Examples of YPA-specific proteins encoded by genes for which we observe significantly different expression levels are shown. Scales are given at the bottom.

The second YPA-specific group comprises 97 loci for which mRNA is detected at various levels in YPD but its concentration increases in YPA (Fig. 4B). URS1 motif predictions and RNA profiling data indicate that these genes include eleven new potential Ume6 targets involved in acetate transport and spore packaging (ADY2), respiration (RSF1), energy metabolism (BNA2), cell wall integrity (PUN1), protein transport (VPS73), protein turnover (DAS1), protein modification (PIG1), thermotolerance (NTH2), DNA repair (PDC1), multi-drug transport (PDR10), and stress response (YLR446W). Interestingly, we also find RIM8 and RIM13, which control RIM1, a positive regulator of sporulation and invasive growth [74,75], and IMP2, a gene required for respiration and sporulation [76].

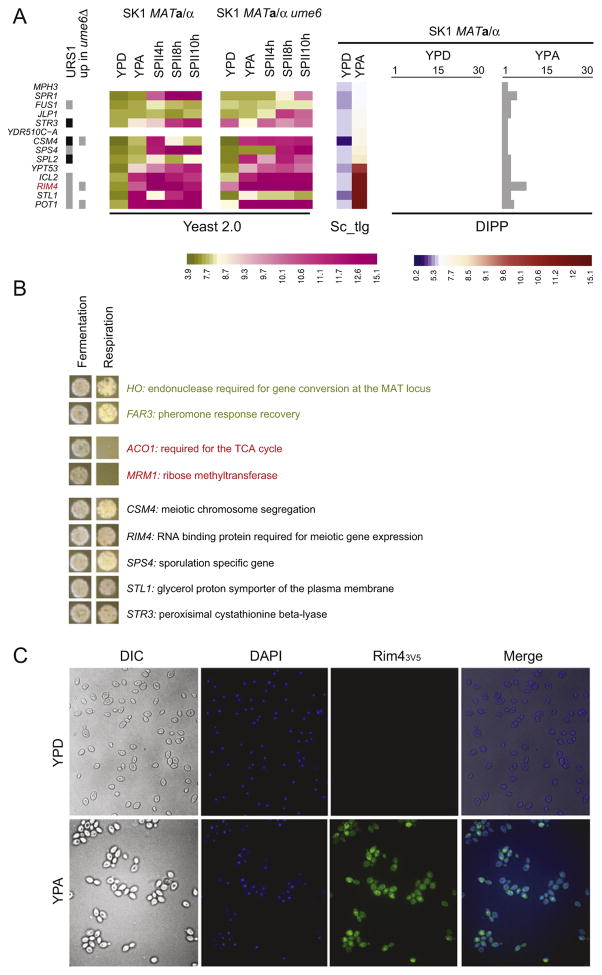

The third YPA-specific group consists of 14 genes for which mRNAs and proteins are detected only in YPA (Fig. 5A). Some gene functions are consistent with growth in YPA, such as energy metabolism controlled by glucose and ethanol (ICL2), stress-induced protein transport (YPT53), stress response (SPL2), carbohydrate transport (MPH3), glycerol transport (STL1), sulphur catabolism important for efficient anaerobic growth (JLP1), amino acid biosynthesis (STR3), and fatty-acid oxidation (POT1). Furthermore, we identified a dubious gene (YDR510C-A), a gene involved in cell fusion during mating (FUS1), and another four genes previously considered to be meiosis-specific (CSM4, RIM4, SPR1 and SPS4 [77–82]). To find out if genes showing such patterns played new roles during respiration, we used a plate growth assay to analyze diploid homozygous csm4, rim4, sps4, stl1 and str3 mutants in the presence of fermentable- or non-fermentable carbon sources. None of the mutants appeared to be respiration deficient. HO and FAR3 were used as negative controls, and ACO1 and MRM1 were positive controls (Fig. 5B). The third group includes three genes with known URS1 motifs (CSM4, SPl2, STR3) and two new targets that contain predicted Ume6 binding sites in their upstream regions (POT1, RIM4). Rim4 is an RNA-binding protein important for mRNA translation during meiosis and spore formation [78,79]. Since the Ume6 level decreases and its ability to bind DNA diminishes when cells enter respiration, it is possible that RIM4 is partially de-repressed in YPA [32,59,60]. To rule out that Rim4 accumulates in YPA because the protein is strongly induced in a small sub-population of cells undergoing premature sporulation [77,78], we analyzed a strain expressing C-terminally tagged Rim4 (which showed normal growth and sporulation properties), and found that all cells cultured in YPA expressed the protein (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Correlating gene expression, protein detection and protein localization patterns. (A) A color-coded heatmap like in Fig. 3 is shown for 14 target genes with an expression and a proteomic pattern specific for YPA. (B) The outcome of a plate patch assay on YPD (fermentation) versus YPEG (respiration) is shown for positive and negative controls in red and green, respectively and new targets given in black. (C) Immunofluorescence data are shown for tagged Rim4 (Rim43V5) in cells cultured in YPD and YPA. Cells were visualized using differential interference contrast microscopy (DIC). DNA and proteins were visualized using a fluorophor (DAPI) and an antibody against the tag (Rim43V5), respectively, and both are displayed together to detect nuclear signals and cytoplasmic signals (Merge).

4. Discussion

We integrated transcriptome and proteome data from growing diploid MATa/α yeast cells cultured in rich medium, and pre-sporulation medium where glucose was replaced by the non-fermentable carbon source acetate. We interpreted the output in the context of functional information. Our results contribute to yeast genome annotation, and they help gain insight into the molecular processes, which coordinate energy metabolism with stress response during cell growth and differentiation.

4.1. Why are proteins absent although the cells contain their cognate mRNAs?

For 1630 ORFs we find evidence for mRNAs but not for proteins in at least one medium (some proteins in this category also fall into the class of 5513 proteins detected in at least one medium, which is why their sum is greater than the total number of 6713 predicted proteins). The proteins in this group tend to be somewhat smaller than the global average (median of 231 amino acids versus 358 for all proteins; p-value of Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction < 2.2 × 10−16; Fig. S2A). 598 proteins are less than 150 amino acids long, and may therefore have been lost during the pre-fractionation procedure, but for 1032 cases other explanations such as annotation artefacts, special biological roles or inherent instability during growth seem more likely. Indeed, among 1032 ORFs we find 47 dubious genes and 200 uncharacterized genes. Furthermore, significantly enriched terms from the Biological Process Gene Ontology reveal functions likely not important during fast mitotic growth in rich media: this includes processes related to retroviruses and gametogenesis such as transposition, RNA-mediated and transposition (p-value: 6.28 × 10−32), reproduction (7.38 × 10−5), reproductive process (3.85 × 10−5), and DNA recombination (2.08 × 10−8). Other pathways are DNA metabolic process (0.00141), protein catabolic process (0.00264), proteolysis (0.00400), regulation of biological quality (0.00868), and notably, response to chemical stimulus (0.00343), reflecting in part the activity of stress-response genes likely repressed during growth under perfect conditions (Fig. S2B).

4.2. Gene expression and protein function

We identified two genes as potentially important for fermentation (YJR085C, YPR010C-A), which were not among the loci studied by systematic gene deletion experiments and chemoprofiling [50,83]. Strain lacking these genes did, however, not display any discernible growth phenotype in plate assays using ethanol/glycerol or acetate as non-fermentable carbon sources (Fig. S1C). Since the genes have no obvious paralog, genetic redundancy cannot explain this result. Given that Yjr085c is a mitochondrial protein induced by chemically induced DNA damage, it is possible that its role is limited to a stress response other than processing a non-fermentable carbon course [55,57,58,84]. Likewise, Ypr010c-a interacts with, among others, Ubi4 (protein degradation) and Nab2 (mRNA export), which are involved in DNA replication stress [58,85,86]. Yjr085c and Ypr010c-a may therefore exert their activities only under experimental conditions unrelated to carbon metabolism.

4.3. Nutritional control of cell fate involves the HDAC Rpd3/Sin3/Ume6 complex

We identified 14 loci for which we detected both mRNA and proteins exclusively in YPA. This group includes four cases—CSM4, SPR1, SPS4, and RIM4—thought to be active only in sporulating cells. It is unclear why previous studies did not observe these proteins in dividing cells as well, but it might be due to cell culture protocols and strain backgrounds. Csm4 localizes to the nuclear envelope and is required for the mobility of telomeres during meiosis, and Sps4 was initially reported to be a meiosis-specific gene induced during middle sporulation [80,82]. In SK1, we find that the CSM4 and SPS4 are weakly transcribed in YPA and strongly induced when cells have initiated meiosis (SGV; www.germonline.org). This low level of expression might be enough for the proteins to accumulate. The detection of Spr1 in YPA is unexpected because the protein acts during late sporulation where it renders spores thermoresistant [87]. Moreover, tiling array data show that SPR1 is only partially expressed in YPA from what appears to be an internal transcription start site (SGV via www.germonline.org), and it is possible that the overlapping antisense lncRNA SUT785 contributes to SPR1’s mitotic repression. Perhaps the fortuitous expression of a shorter mRNA or mRNA levels below our threshold level of detection is sufficient to allow for the accumulation of a truncated or a full-length version of Spr1 in YPA. RIM4 is induced in YPA as opposed to an earlier report where neither mRNA nor protein was detected in this medium [77]. Both studies used the SK1 strain and YPA pre-sporulation medium but work by Soushko and Mitchell was done in an SK1-derived background lacking the GAL80 regulator, which somehow may influence RIM4 expression. The upstream region of RIM4 contains URS1 motifs and was found to interact with Ume6 in vivo [31,77]. Moreover, we observe that the RIM4 mRNA is de-repressed in ume6 mutant cells cultured in YPD and YPA. While the data imply that RIM4 is transcriptionally controlled like a typical early meiotic gene [88], our results beg the question why RIM4 is induced in YPA when the Rpd3/Sin3/Ume6 repressor complex is still active. It is known that acetate triggers Ume6’s degradation and negatively influences its ability to bind DNA, which perhaps enables Rim4 to accumulate during vegetative growth in respiring cells (at least in a genetic background that sporulates efficiently) [32,59,60]. It is not clear why Rim4 accumulates in YPA, because it does not seem to be involved in producing energy with a non-fermentable carbon source (see Fig. 4B). However, the protein is required for the complex and highly stage-specific translational control of many proteins during meiosis via binding to 5′-UTRs, including some that are important for M-phase [79]. We therefore speculate that Rim4’s early accumulation in respiring cells during late-log phase enables the SK1 background to rapidly progress through the meiotic differentiation pathway once it is triggered by the onset of Ime1 expression [2].

We have recently reported that the Rpd3/Sin3/Ume6 complex represses early meiotic transcript isoforms with extended 5′-UTRs during vegetative growth [89]. This, together with the observations reported here, raises the interesting possibility that the progressive degradation of Ume6 during the switch from fermentation to respiration and sporulation, simultaneously de-represses the 5′-UTR interacting protein Rim4 and long transcript isoforms that are bound by the protein [79].

5. Conclusion

The present study reveals complex regulatory processes affecting mRNA and protein stability that underlie the transition from fermentation to respiration in sporulation-competent diploid yeast cells. Moreover, it provides further insight into the role of the conserved HDAC complex Ume6/Rpd3/Sin3 in coordinating metabolic functions with stress response and cellular differentiation in a simple eukaryote. Given the recent major advances in proteomics [17] the next goal will be to determine the comprehensive proteome of the entire diploid yeast life cycle, and to integrate this information with the transcriptome, functional annotation data and protein networks.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2015.01.015.

Acknowledgments

We thank Olivier Collin for providing us with access to the GenOuest bioinformatics infrastructure, Olivier Sallou for system administration, Emmanuelle Com for uploading the proteome data to the PRIDE repository, and Angelika Amon and Luke Edwin Berchowitz for tagged Rim4. Yuchen Liu was funded by a Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FDT20100920148) 4th year PhD fellowship. This work was supported by the grants National Institute of General Medical Studies (P41 GM103533) at the US National Institutes of Health to M. R. and Inserm Avenir R07216NS, and Région Bretagne CREATE R11016NN awarded to M. P.

Footnotes

Transparency document

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in the online version.

References

- 1.Cullen PJ, Sprague GF., Jr The regulation of filamentous growth in yeast. Genetics. 2012;190:23–49. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.127456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neiman AM. Sporulation in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2011;189:737–65. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.127126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goranov AI, Amon A. Growth and division—not a one-way road. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:795–800. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giaever G, Flaherty P, Kumm J, Proctor M, Nislow C, Jaramillo DF, et al. Chemogenomic profiling: identifying the functional interactions of small molecules in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:793–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307490100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlecht U, St Onge RP, Walther T, Francois JM, Davis RW. Cationic amphiphilic drugs are potent inhibitors of yeast sporulation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dos Santos SC, Teixeira MC, Cabrito TR, Sa-Correia I. Yeast toxicogenomics: genome-wide responses to chemical stresses with impact in environmental health, pharmacology, and biotechnology. Front Genet. 2012;3:63. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goffeau A, Barrell BG, Bussey H, Davis RW, Dujon B, Feldmann H, et al. Life with 6000 genes. Science. 1996;274(546):63–7. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherry JM, Hong EL, Amundsen C, Balakrishnan R, Binkley G, Chan ET, et al. Saccharomyces Genome Database: the genomics resource of budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D700–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lashkari DA, DeRisi JL, McCusker JH, Namath AF, Gentile C, Hwang SY, et al. Yeast microarrays for genome wide parallel genetic and gene expression analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13057–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.David L, Huber W, Granovskaia M, Toedling J, Palm CJ, Bofkin L, et al. A high-resolution map of transcription in the yeast genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5320–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601091103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagalakshmi U, Wang Z, Waern K, Shou C, Raha D, Gerstein M, et al. The transcriptional landscape of the yeast genome defined by RNA sequencing. Science. 2008;320:1344–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1158441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Godoy LM, Olsen JV, Cox J, Nielsen ML, Hubner NC, Frohlich F, et al. Comprehensive mass-spectrometry-based proteome quantification of haploid versus diploid yeast. Nature. 2008;455:1251–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Picotti P, Bodenmiller B, Mueller LN, Domon B, Aebersold R. Full dynamic range proteome analysis of S. cerevisiae by targeted proteomics. Cell. 2009;138:795–806. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thakur SS, Geiger T, Chatterjee B, Bandilla P, Frohlich F, Cox J, et al. Deep and highly sensitive proteome coverage by LC-MS/MS without prefractionation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M110 003699. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.003699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagaraj N, Kulak NA, Cox J, Neuhauser N, Mayr K, Hoerning O, et al. System-wide perturbation analysis with nearly complete coverage of the yeast proteome by single-shot ultra HPLC runs on a bench top Orbitrap. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:M111 013722. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.013722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hebert AS, Richards AL, Bailey DJ, Ulbrich A, Coughlin EE, Westphall MS, et al. The one hour yeast proteome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:339–47. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.034769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gancedo JM. Yeast carbon catabolite repression. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:334–61. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.334-361.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zaman S, Lippman SI, Zhao X, Broach JR. How Saccharomyces responds to nutrients. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:27–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee YJ, Jang JW, Kim KJ, Maeng PJ. TCA cycle-independent acetate metabolism via the glyoxylate cycle in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2011;28:153–66. doi: 10.1002/yea.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gutteridge A, Pir P, Castrillo JI, Charles PD, Lilley KS, Oliver SG. Nutrient control of eukaryote cell growth: a systems biology study in yeast. BMC Biol. 2010;8:68. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boer VM, de Winde JH, Pronk JT, Piper MD. The genome-wide transcriptional responses of Saccharomyces cerevisiae grown on glucose in aerobic chemostat cultures limited for carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, or sulfur. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3265–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castrillo JI, Zeef LA, Hoyle DC, Zhang N, Hayes A, Gardner DC, et al. Growth control of the eukaryote cell: a systems biology study in yeast. J Biol. 2007;6:4. doi: 10.1186/jbiol54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diaz-Ruiz R, Rigoulet M, Devin A. The Warburg and Crabtree effects: on the origin of cancer cell energy metabolism and of yeast glucose repression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1807;2011:568–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kadosh D, Struhl K. Targeted recruitment of the Sin3–Rpd3 histone deacetylase complex generates a highly localized domain of repressed chromatin in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5121–7. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rundlett SE, Carmen AA, Suka N, Turner BM, Grunstein M. Transcriptional repression by UME6 involves deacetylation of lysine 5 of histone H4 by RPD3. Nature. 1998;392:831–5. doi: 10.1038/33952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldmark JP, Fazzio TG, Estep PW, Church GM, Tsukiyama T. The Isw2 chromatin remodeling complex represses early meiotic genes upon recruitment by Ume6p. Cell. 2000;103:423–33. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steber CM, Esposito RE. UME6 is a central component of a developmental regulatory switch controlling meiosis-specific gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:12490–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strich R, Surosky RT, Steber C, Dubois E, Messenguy F, Esposito RE. UME6 is a key regulator of nitrogen repression and meiotic development. Genes Dev. 1994;8:796–810. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.7.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams RM, Primig M, Washburn BK, Winzeler EA, Bellis M, et al. The Ume6 regulon coordinates metabolic and meiotic gene expression in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13431–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202495299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harbison CT, Gordon DB, Lee TI, Rinaldi NJ, Macisaac KD, Danford TW, et al. Transcriptional regulatory code of a eukaryotic genome. Nature. 2004;431:99–104. doi: 10.1038/nature02800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mallory MJ, Law MJ, Sterner DE, Berger SL, Strich R. Gcn5p-dependent acetylation induces degradation of the meiotic transcriptional repressor Ume6p. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:1609–17. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-06-0536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strich R, Khakhina S, Mallory MJ. Ume6p is required for germination and early colony development of yeast ascospores. FEMS Yeast Res. 2011;11:104–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavigne R, Becker E, Liu Y, Evrard B, Lardenois A, Primig M, et al. Direct iterative protein profiling (DIPP)—an innovative method for large-scale protein detection applied to budding yeast mitosis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:M111 012682. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.012682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winzeler EA, Shoemaker DD, Astromoff A, Liang H, Anderson K, Andre B, et al. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science. 1999;285:901–6. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lardenois A, Liu Y, Walther T, Chalmel F, Evrard B, Granovskaia M, et al. Execution of the meiotic noncoding RNA expression program and the onset of gametogenesis in yeast require the conserved exosome subunit Rrp6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1058–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016459108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scherthan H, Trelles-Stricken E. Yeast FISH: delineation of chromosomal targets in vegetative and meiotic yeast cells. In: Liehr T, editor. Springer lab manual on FISH technology. Springer; 2002. pp. 329–45. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meluh PB, Koshland D. Budding yeast centromere composition and assembly as revealed by in vivo cross-linking. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3401–12. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riffle M, Malmstrom L, Davis TN. The Yeast Resource Center Public Data Repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D378–82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Primig M, Williams RM, Winzeler EA, Tevzadze GG, Conway AR, Hwang SY, et al. The core meiotic transcriptome in budding yeasts. Nat Genet. 2000;26:415–23. doi: 10.1038/82539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlecht U, Demougin P, Koch R, Hermida L, Wiederkehr C, Descombes P, et al. Expression profiling of mammalian male meiosis and gametogenesis identifies novel candidate genes for roles in the regulation of fertility. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:1031–43. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-10-0762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smyth GK. Limma: linear models for microarray data. In: Gentleman VCR, Dudoit S, Irizarry R, Huber W, editors. Bioinformatics and computational biology solutions using R and bioconductor. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Team RDC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trepos-Pouplard M, Lardenois A, Staub C, Guitton N, Dorval-Coiffec I, Pineau C, et al. Proteome analysis and genome-wide regulatory motif prediction identify novel potentially sex-hormone regulated proteins in rat efferent ducts. Int J Androl. 2010;33:661–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghaemmaghami S, Huh WK, Bower K, Howson RW, Belle A, Dephoure N, et al. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425:737–41. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hornbeck PV, Kornhauser JM, Tkachev S, Zhang B, Skrzypek E, Murray B, et al. PhosphoSitePlus: a comprehensive resource for investigating the structure and function of experimentally determined post-translational modifications in man and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D261–70. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin D, Brun C, Remy E, Mouren P, Thieffry D, Jacq B. GOToolBox: functional analysis of gene datasets based on Gene Ontology. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R101. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-12-r101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lardenois A, Gattiker A, Collin O, Chalmel F, Primig M. GermOnline 4.0 is a genomics gateway for germline development, meiosis and the mitotic cell cycle. Database. 2010;2010:baq030. doi: 10.1093/database/baq030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Galdieri L, Mehrotra S, Yu S, Vancura A. Transcriptional regulation in yeast during diauxic shift and stationary phase. OMICS. 2010;14:629–38. doi: 10.1089/omi.2010.0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hillenmeyer ME, Fung E, Wildenhain J, Pierce SE, Hoon S, Lee W, et al. The chemical genomic portrait of yeast: uncovering a phenotype for all genes. Science. 2008;320:362–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1150021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klapholz S, Waddell CS, Esposito RE. The role of the SPO11 gene in meiotic recombination in yeast. Genetics. 1985;110:187–216. doi: 10.1093/genetics/110.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jambhekar A, Amon A. Control of meiosis by respiration. Curr Biol. 2008;18:969–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burtner CR, Murakami CJ, Olsen B, Kennedy BK, Kaeberlein M. A genomic analysis of chronological longevity factors in budding yeast. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:1385–96. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.9.15464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hyle JW, Shaw RJ, Reines D. Functional distinctions between IMP dehydrogenase genes in providing mycophenolate resistance and guanine prototrophy to yeast. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28470–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303736200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reinders J, Zahedi RP, Pfanner N, Meisinger C, Sickmann A. Toward the complete yeast mitochondrial proteome: multidimensional separation techniques for mitochondrial proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:1543–54. doi: 10.1021/pr050477f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Renvoise M, Bonhomme L, Davanture M, Valot B, Zivy M, Lemaire C. Quantitative variations of the mitochondrial proteome and phosphoproteome during fermentative and respiratory growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Proteome. 2014;106:140–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sickmann A, Reinders J, Wagner Y, Joppich C, Zahedi R, Meyer HE, et al. The proteome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13207–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135385100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tkach JM, Yimit A, Lee AY, Riffle M, Costanzo M, Jaschob D, et al. Dissecting DNA damage response pathways by analysing protein localization and abundance changes during DNA replication stress. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:966–76. doi: 10.1038/ncb2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mallory MJ, Cooper KF, Strich R. Meiosis-specific destruction of the Ume6p Repressor by the Cdc20-directed APC/C. Mol Cell. 2007;27:951–61. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Law MJ, Mallory MJ, Dunbrack RL, Jr, Strich R. Acetylation of the transcriptional repressor Ume6p allows efficient promoter release and timely induction of the meiotic transient transcription program in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:631–42. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00256-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rabitsch KP, Toth A, Galova M, Schleiffer A, Schaffner G, Aigner E, et al. A screen for genes required for meiosis and spore formation based on whole-genome expression. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1001–9. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paiva S, Devaux F, Barbosa S, Jacq C, Casal M. Ady2p is essential for the acetate permease activity in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2004;21:201–10. doi: 10.1002/yea.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gentsch M, Kuschel M, Schlegel S, Barth G. Mutations at different sites in members of the Gpr1/Fun34/YaaH protein family cause hypersensitivity to acetic acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae as well as in Yarrowia lipolytica. FEMS Yeast Res. 2007;7:380–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park HD, Luche RM, Cooper TG. The yeast UME6 gene product is required for transcriptional repression mediated by the CAR1 URS1 repressor binding site. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1909–15. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.8.1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vershon AK, Hollingsworth NM, Johnson AD. Meiotic induction of the yeast HOP1 gene is controlled by positive and negative regulatory sites. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3706–14. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.9.3706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tevzadze GG, Pierce JV, Esposito RE. Genetic evidence for a SPO1-dependent signaling pathway controlling meiotic progression in yeast. Genetics. 2007;175:1213–27. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.069252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Engebrecht J, Masse S, Davis L, Rose K, Kessel T. Yeast meiotic mutants proficient for the induction of ectopic recombination. Genetics. 1998;148:581–98. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.2.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krisak L, Strich R, Winters RS, Hall JP, Mallory MJ, Kreitzer D, et al. SMK1, a developmentally regulated MAP kinase, is required for spore wall assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2151–61. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.18.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Law DT, Segall J. The SPS100 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is activated late in the sporulation process and contributes to spore wall maturation. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:912–22. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.2.912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bajgier BK, Malzone M, Nickas M, Neiman AM. SPO21 is required for meiosis-specific modification of the spindle pole body in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1611–21. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.6.1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cai H, Kauffman S, Naider F, Becker JM. Genomewide screen reveals a wide regulatory network for di/tripeptide utilization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2006;172:1459–76. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.053041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Prinz S, Amon A, Klein F. Isolation of COM1, a new gene required to complete meiotic double-strand break-induced recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1997;146:781–95. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.3.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McKee AH, Kleckner N. A general method for identifying recessive diploid-specific mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, its application to the isolation of mutants blocked at intermediate stages of meiotic prophase and characterization of a new gene SAE2. Genetics. 1997;146:797–816. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.3.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Su SS, Mitchell AP. Identification of functionally related genes that stimulate early meiotic gene expression in yeast. Genetics. 1993;133:67–77. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li W, Mitchell AP. Proteolytic activation of Rim1p, a positive regulator of yeast sporulation and invasive growth. Genetics. 1997;145:63–73. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Donnini C, Lodi T, Ferrero I, Puglisi PP. IMP2, a nuclear gene controlling the mitochondrial dependence of galactose, maltose and raffinose utilization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1992;8:83–93. doi: 10.1002/yea.320080203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Soushko M, Mitchell AP. An RNA-binding protein homologue that promotes sporulation-specific gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2000;16:631–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(200005)16:7<631::AID-YEA559>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Deng C, Saunders WS. RIM4 encodes a meiotic activator required for early events of meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Genet Genomics. 2001;266:497–504. doi: 10.1007/s004380100571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Berchowitz LE, Gajadhar AS, van Werven FJ, De Rosa AA, Samoylova ML, Brar GA, et al. A developmentally regulated translational control pathway establishes the meiotic chromosome segregation pattern. Genes Dev. 2013;27:2147–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.224253.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Conrad MN, Lee CY, Chao G, Shinohara M, Kosaka H, Shinohara A, et al. Rapid telomere movement in meiotic prophase is promoted by NDJ1, MPS3, and CSM4 and is modulated by recombination. Cell. 2008;133:1175–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wanat JJ, Kim KP, Koszul R, Zanders S, Weiner B, Kleckner N, et al. Csm4, in collaboration with Ndj1, mediates telomereled chromosome dynamics and recombination during yeast meiosis. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Garber AT, Segall J. The SPS4 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes a major sporulation-specific mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:4478–85. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.12.4478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Giaever G, Chu AM, Ni L, Connelly C, Riles L, Veronneau S, et al. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature. 2002;418:387–91. doi: 10.1038/nature00935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee MW, Kim BJ, Choi HK, Ryu MJ, Kim SB, Kang KM, et al. Global protein expression profiling of budding yeast in response to DNA damage. Yeast. 2007;24:145–54. doi: 10.1002/yea.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Finley D, Ozkaynak E, Varshavsky A. The yeast polyubiquitin gene is essential for resistance to high temperatures, starvation, and other stresses. Cell. 1987;48:1035–46. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90711-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kuhlmann SI, Valkov E, Stewart M. Structural basis for the molecular recognition of polyadenosine RNA by Nab2 Zn fingers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:672–80. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Muthukumar G, Suhng SH, Magee PT, Jewell RD, Primerano DA. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SPR1 gene encodes a sporulation-specific exo-1,3-beta-glucanase which contributes to ascospore thermoresistance. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:386–94. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.2.386-394.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mitchell AP. Control of meiotic gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:56–70. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.1.56-70.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lardenois A, Stuparevic I, Liu Y, Law MJ, Becker E, Smagulova F, et al. The conserved histone deacetylase Rpd3 and its DNA binding subunit Ume6 control dynamic transcript architecture during mitotic growth and meiotic development. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(1):115–28. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]