Abstract

Purpose

Although fear of recurrence (FCR) is common among cancer survivors, it remains unclear what factors predict initial levels (e.g., prior to surgery) or changes in FCR in the post-treatment period. Among women treated for breast cancer, this study evaluated the effects of demographic, clinical, symptom, and psychosocial adjustment characteristics on the initial (preoperative) levels of FCR and trajectories of FCR over the six months following surgery.

Methods

Prior to and for six months following breast cancer surgery, 396 women were assessed for demographic and clinical (disease and treatment) characteristics, symptoms, psychological adjustment characteristics, and quality of life (QOL). FCR was assessed using a four-item subscale from the QOL instrument. Hierarchical linear modeling was used to examine changes in FCR scores and to identify predictors of inter-individual differences in preoperative FCR levels and trajectories over six months.

Results

From before surgery to six months postoperatively, women with breast cancer showed a high degree of inter-individual variability in FCR. Preoperatively, women who lived with someone, experienced greater changes in spiritual life, had higher state anxiety, had more difficulty coping, or experienced more distress due to diagnosis or distress to family members reported higher FCR scores. Patients who reported better overall physical health and higher FCR scores at enrollment demonstrated a steeper decrease in FCR scores.

Conclusions

These findings highlight inter-individual heterogeneity in initial levels and changes in FCR over time among women undergoing breast cancer surgery. Further work is needed to identify women most at risk for FCR during survivorship.

Keywords: oncology, breast cancer, fear of recurrence, psychological symptoms, symptom trajectories, hierarchical linear modeling

INTRODUCTION

Fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) is one of the most pervasive concerns and unmet needs of cancer survivors [1–3]. FCR is associated with decrements in mental, physical, and social aspects of quality of life (QOL) and can persist long after completion of active treatment [2, 4–6]. Across a number of cross-sectional studies, FCR was positively correlated with anxiety [7–14], avoidance [5, 7, 8, 10, 11], depressive symptoms [2, 7, 8, 10–13, 15] denial [12], cognitive intrusions, [2, 7, 8, 10, 11], and higher threat appraisal [16]. However, findings are inconsistent regarding the relationships between FCR and disease stage or treatment [1, 5, 17–19].

A number of longitudinal studies evaluated FCR among cancer survivors in order to identify its prevalence, persistence, and risk factors (see [1, 20] for systematic reviews). A recent systematic review found that FCR tended to remain stable over time and that higher baseline levels of FCR predicted higher levels of FCR over time [1]. However, among existing longitudinal studies, predictors of FCR varied considerably across studies. Moreover, because linear or logistic regression analyses were typically performed, little is known about demographic and clinical characteristics that predict inter-individual variability in initial levels of and changes in FCR over time.

Hierarchical linear modeling (HLM), a type of longitudinal data analysis, affords the opportunity to examine inter-individual differences in the trajectories of FCR. Its usefulness in this context is to identify what demographic and clinical characteristics predict initial levels of FCR, as well as the trajectories of FCR. Only one study was found that used a type of HLM to evaluate FCR over time [21]. In this prospective study, Actor-Partner Independence Model (APIM) was used to examine predictors of FCR in cancer survivors and their family caregivers. This study identified higher level of family stressors, less positive meaning of the illness, and younger age as predictors of fear of recurrence in both patients and family caregivers [21].

To our knowledge, no studies have used HLM to evaluate predictors of inter-individual differences in FCR in a diagnostically homogeneous sample of breast cancer patients prior to and following breast cancer surgery. Such an analysis would enhance our understanding of what factors contribute to elevated FCR prior to surgery and to changes in the levels of FCR in the post-treatment period. Therefore, the purposes of this study were to identify the trajectories of FCR among women who were assessed preoperatively and monthly for six months following breast cancer surgery and to evaluate whether specific demographic, clinical, symptom, and psychosocial adjustment characteristics predicted the initial (preoperative) levels of FCR and characteristics of the trajectories of FCR over the six months following surgery.

METHODS

Patients and Settings

Patients and settings

This longitudinal study is part of a larger study that evaluated neuropathic pain and lymphedema in a sample of women who underwent breast cancer surgery. The methods for this study are described in detail elsewhere [22–25]. In brief, patients were recruited from Breast Care Centers located in a Comprehensive Cancer Center, two public hospitals, and four community practices. Women were eligible if they were ≥18 years of age; were scheduled to undergo breast cancer surgery on one breast; were able to read, write, and understand English; and provided written informed consent. Patients were excluded if they were having bilateral breast cancer surgery and/or had distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis. A total of 516 patients were approached and 410 enrolled in the study (response rate 79.5%). The major reasons for refusal were: too busy, overwhelmed with the cancer diagnosis, or insufficient time available to complete the baseline assessment prior to surgery.

Instruments

At enrollment, demographic information was obtained. At each subsequent assessment, patients provided information on current treatments for breast cancer. Medical records were reviewed to obtain information on stage of disease, surgical procedure, neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatments, and reconstructive surgery.

Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scale is widely used to evaluate functional status in patients with cancer and has well established validity and reliability [26]. Patients rated their functional status using the KPS scale that ranged from 30 (“I feel severely disabled and need to be hospitalized”) to 100 (“I feel normal; I have no complaints or symptoms”).

Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire (SCQ), which was developed to assess comorbidity in clinical and health service research settings [27], consists of 13 common medical conditions, rated for presence, treatment status, and functional limitations (range of possible scores 0 to 39). The SCQ has well-established validity and reliability and has been used in studies of patients with a variety of chronic conditions [27, 28].

Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale consists of 20 items representing the major symptoms in the clinical syndrome of depression. Scores can range from 0 to 60, with scores of ≥16 indicating the need for clinical evaluation for major depression. The CES-D has well-established concurrent and construct validity [29, 30]. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90.

Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventories (STAI-T and STAI-S) consist of 20 items, each rated from 1 to 4. Total scores for each scale can range from 20 to 80, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety. The STAI-T measures a person’s predisposition to anxiety and estimates how a person generally feels. The STAI-S measures an individual’s transitory emotional response, with items assessing worry, nervousness, tension, and apprehension related to how a person feels “right now”. Scores ≥31.8 and ≥32.2 suggest higher levels of trait and state anxiety, respectively [31, 32]. Both inventories have well-established criterion and construct validity and internal consistency [33]. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alphas for the STAI-T and STAI-S were 0.88 and 0.95, respectively.

Patients were asked to indicate if they had pain in the breast. If they reported in the affirmative they were asked to rate the intensity of their pain (i.e., pain now, average and worst pain) using a NRS that ranged from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain). Numeric rating scales are valid and reliable measures of pain intensity [34].

Quality of Life

Patient Version (QOL-PV) is a 41-item instrument that measures four dimensions of QOL in cancer patients (i.e., physical well-being, psychological well-being, spiritual well-being, social well-being) as well as a total QOL score. Each item is rated on a 0 to 10 NRS with higher scores indicating a better QOL. The QOL-PV has established validity and reliability [35, 36]. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the QOL-PV total score was .86 and for the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being subscales the coefficients were 0.70, 0.79, 0.75, and 0.61, respectively. For this analysis, the following individual items from the QOL-PV were selected as potential predictors based on prior literature and conceptual relationships to FCR [1, 6]: overall physical health, overall quality of life, happiness, feeling in control of things in life, life satisfaction, feeling useful, having sufficient support from others, importance of religious participation, importance of other spiritual activities, change in spiritual life since diagnosis, positive changes due to illness, having a purpose/mission for life, hopefulness, difficulty coping as a result of disease and treatment, distress related to initial diagnosis, distress of illness to family, interference with personal relationships, and isolation caused by illness or treatment.

Fear of Cancer Recurrence (FCR) subscale

Four items from the QOL-PV were selected to construct the FCR outcome measure. These items asked women to rate their fear of: (1) future diagnostic tests; (2) a second cancer; (3) recurrence; and (4) metastasis, on a scale of 0 (“no fear”) to 10 (“extreme fear”). The Cronbach’s alpha for this four-item subscale was 0.94.

Study Procedures

The Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco and at each study site approved the study. During the patient’s preoperative visit, a staff member explained the study to the patient. For those women willing to participate, the staff member introduced the patient to the research nurse, who met with the women, determined eligibility, and obtained written informed consent prior to surgery. After providing consent, the patient completed the enrollment questionnaires (Assessment 0). Patients were contacted two weeks after surgery to schedule the first post-surgical appointment. The research nurse met with the patients in their home, the Clinical Research Center, or the clinic at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 months after surgery. During each study visit, the women completed the study instruments.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics and frequency distributions were generated on the sample characteristics, and baseline symptom severity scores using SPSS version 22 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois). For each of the seven assessments, a mean FCR score was calculated as the outcome variable in the HLM analyses.

HLM, based on full maximum likelihood estimation, was done using the software developed by Raudenbush and colleagues [37]. Change in FCR scores was analyzed at two levels: within persons (level 1) and between persons (level 2). At level 1, FCR scores were a function of person-specific change parameters plus error. Three level 1 models were compared to determine whether the patients’ FCR scores did not change over time (i.e., no time effect), changed at a constant rate (i.e., linear time effect), or changed at a rate that accelerated or decelerated over time (i.e., quadratic effect). At this point, the model was constrained to be unconditional (i.e., no predictors) and likelihood ratio tests were used to determine the best model. These analyses identified the change parameters that best described individual changes in FCR over time.

At level 2, FCR scores were modeled as the individual change parameters (i.e., intercept, slope) as a function of the proposed predictors listed in Table 1. To improve estimation and efficiency, an exploratory level 2 analysis was completed in which each potential predictor was assessed to determine whether it was associated with FCR scores. Only predictors with t-values >2.0, indicating a significant association, were selected for subsequent model testing. All significant predictors from the exploratory analyses were entered into the model to predict each individual change parameter. Only predictors that maintained a statistically significant contribution in conjunction with other variables were retained in the final model. A p-value of <0.05 indicated statistical significance. Combining level 1 with level 2 results in a mixed model with fixed and random effects [37].

Table 1.

Variables identified from exploratory analyses as potential predictors of fear of cancer recurrence, based on t-values ≥2.00, indicated by filled boxes (■) for women prior to and following breast cancer surgery.

| VARIABLES | INTERCEPT | LINEAR | QUADRATIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS | |||

|

| |||

| Age | ■ | ||

| Education | |||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Living alone | ■ | ||

| Married/partnered | ■ | ||

| Employed | |||

| Self-administered Comorbidity Questionnaire score | |||

|

| |||

| CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS | |||

|

| |||

| Karnofsky Performance Status score | |||

| Post-menopausal status | ■ | ||

| Stage of disease | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Type of surgery | |||

| Reconstruction to breast at time of surgery | |||

| Sentinel node biopsy | |||

| Axillary lymph node dissection | ■ | ||

| Received neoadjuvant therapy | |||

| Time since diagnosis | |||

|

| |||

| SYMPTOMS | |||

|

| |||

| Trait anxiety | ■ | ||

| State anxiety | ■ | ||

| Depressive symptoms | ■ | ||

| Hot flash occurrence | |||

| Hot flash severity | |||

| Hot flash distress | |||

| Current average daily pain | ■ | ||

|

| |||

| PSYCHOSOCIAL ADJUSTMENT CHARACTERISTICS | |||

|

| |||

| Overall physical health | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Overall quality of life | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Happiness | ■ | ||

| In control of things in life | ■ | ||

| Life satisfaction | ■ | ||

| Feelings of usefulness | ■ | ||

| Sufficient support from others | ■ | ||

| Importance of religious participation | |||

| Importance of other spiritual activities | |||

| Change in spiritual life | ■ | ||

| Positive changes due to illness | |||

| Purpose/mission for life | |||

| Hopefulness | ■ | ||

| Difficulty coping as a result of disease and treatment | ■ | ||

| Distress related to initial diagnosis | ■ | ||

| Distress (of illness) to family | ■ | ||

| Interference with personal relationships | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Isolation caused by illness or treatment | ■ | ||

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

The demographic, disease, symptom, and psychological adjustment characteristics of the 396 patients are presented in Table 2. Patients were approximately 55 years of age, primarily white (65%), well-educated, and had a high functional status score.

Table 2.

Demographic, clinical, symptom, and psychological adjustment characteristics of women (N=396).

| CHARACTERISTIC | MEAN (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54.9 (11.6) |

| Education (years) | 15.7 (2.6) |

| Karnofsky Performance Status score | 93.2 (10.3) |

| SCQ total score (13 items) | 4.3 (2.8) |

| Trait Anxiety score (enrollment) | 35.3 (8.8) |

| State Anxiety score (enrollment) | 41.6 (13.3) |

| CES-D score (enrollment) | 13.7 (9.7) |

| Fear of Recurrence score (enrollment) | 5.9 (3.1) |

| % (N) | |

|

| |

| Ethnicity (white) | 64.9 (257) |

| Lives alone (yes) | 23.7 (94) |

| Married/partnered (yes) | 41.4 (164) |

| Employed (yes) | 47.7 (189) |

| Post-menopausal (yes) | 64.9 (257) |

| Stage of disease: | |

| 0 | 18.4 (73) |

| I | 38.4 (152) |

| IIA or B | 34.9 (138) |

| IIIA,B, or C | 8.1 (32) |

| IV | 0.3 (1) |

| Type of surgery: | |

| Mastectomy | 19.7 (78) |

| Breast Conservation | 80.3 (318) |

| Reconstruction at time of surgery (yes) | 21.7 (86) |

| Sentinel node biopsy (yes) | 82.6 (327) |

| Axillary lymph node dissection (yes) | 37.1 (147) |

| Received neoadjuvant therapy | 19.9 (79) |

| Had pain in breast prior to surgery | 27.5 (109) |

Abbreviations: CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale; SCQ = Self-administered Comorbidity Questionnaire

Individual and Mean Change in the Outcome Measures

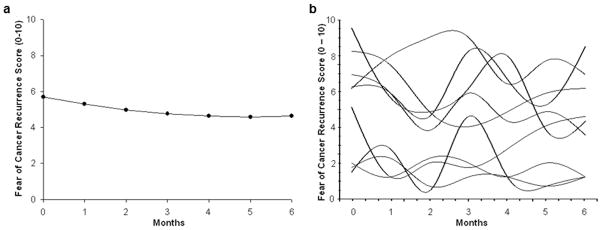

The first HLM analysis examined how FCR scores changed over the course of 6 months. Two models were estimated in which the function of time was linear and quadratic. The final estimate of fixed effects revealed that a quadratic model fit the data best (see Table 3 and Figure 1A). It should be noted that the mean scores for the groups depicted in Figures 2A – 2H are estimated or predicted means based on the HLM analyses.

Table 3.

Hierarchical linear model of fear of cancer recurrence scores for women following breast cancer surgery.

| COEFFICIENT (SE) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| VARIABLE | UNCONDITIONAL MODEL | FINAL MODEL |

| FIXED EFFECTS | ||

| Intercept | 5.670 (0.154) b | 5.842 (0.133) b |

| Timea (linear rate of change) | −0.436 (0.063) b | −0.444 (0.058) b |

| Time2 (quadratic rate of change) | 0.044 (0.009) b | 0.045 (0.009) b |

| TIME INVARIANT COVARIATES | ||

| Intercept | ||

| Lives alone | −0.654 (0.270) c | |

| Change in spiritual life since diagnosis | 0.117 (0.036) c | |

| State anxiety (prior to surgery) | 0.042 (0.010) b | |

| Difficulty coping as result of disease and treatment | 0.256 (0.063) b | |

| Distress related to initial diagnosis | 0.269 (0.050) b | |

| Distress (of illness) to family | 0.154 (0.052) c | |

| Linear | ||

| Overall physical health | −0.093 (0.029) c | |

| Fear mean score (prior to surgery) | −0.098 (0.017) b | |

| Quadratic | ||

| Overall physical health | 0.013 (0.005) c | |

| Fear mean score (prior to surgery) | 0.014 (0.002) b | |

| VARIANCE COMPONENTS | ||

| In intercept | 7.764 b | 3.859 b |

| In linear rate | 0.537 b | 0.307 b |

| In quadratic rate | 0.008 c | 0.005 b |

| GOODNESS-OF-FIT DEVIANCE (parameters estimated) | 10389.299 (10) | 10153.725 (20) |

| MODEL COMPARISON (X2 [df]) | 53.959 (4) b | |

Time was coded 0 at the time of the preoperative visit.

p < 0.001,

p < 0.05

Fig. 1.

Trajectories of fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) scores for (a) the unconditional model, and (b) a random selection of 10 patients’ FCR scores over the course of the 6-month study

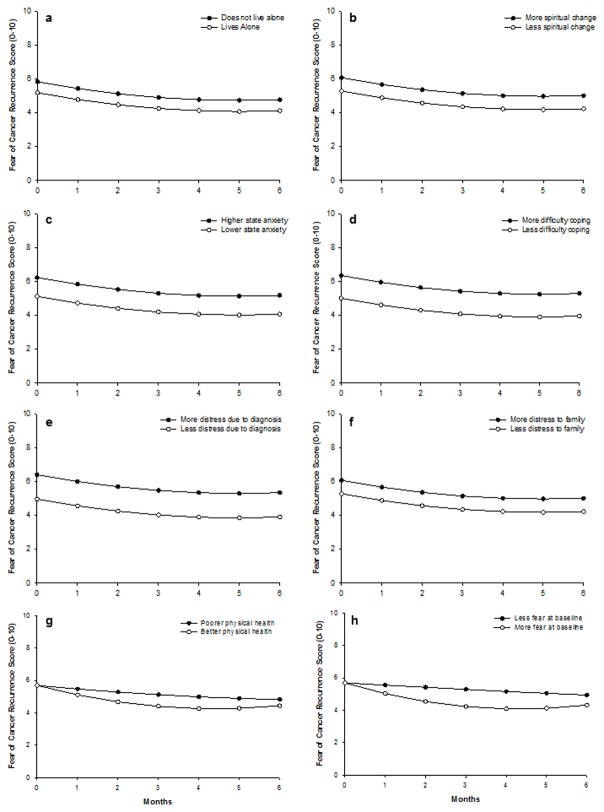

Fig. 2.

Trajectories of fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) scores by (a) living circumstances, (b) changes in spiritual life (c) state anxiety at enrollment, (d) difficulty coping as a result of treatment/disease, (e) distress due to the initial diagnosis, (f) distress of the illness to family, (g) overall physical health, and (h) FCR scores at enrollment. For the continuous variables, higher/lower differences were calculated based on 1 standard deviation above/below the mean score

The estimates of the quadratic change model are presented in Table 3 (unconditional model). Because the model has no covariates (i.e., unconditional), the intercept represents the estimated mean FCR score (i.e., 5.67 on a 0 to 10 scale) prior to surgery. The estimated linear rate of change in FCR scores was −0.44 (p < 0.001), and the estimated quadratic rate of change was 0.04 (p < 0.001). As illustrated in Figure 1A, FCR scores declined significantly across the 6 months of the study, but appeared to plateau at approximately 4 months.

Although the results indicate a sample-wide decline in FCR scores, they do not imply that all patients exhibited the same trajectories. The variance in individual change parameters estimated by the models (see “Variance Components”, Table 3) indicates substantial inter-individual differences in the intercept and trajectories of FCR scores. Therefore, examination of inter-individual differences in the individual change parameters was warranted. As shown in Figure 1B, a spaghetti plot of individual trajectories from a random subset of patients visually demonstrates this variability in FCR scores.

Inter-individual Differences in the Trajectories of FCR Scores

The second stage of the HLM analysis tested the hypothesis that the trajectories of FCR scores varied based on specific person, disease, treatment, symptom, and/or psychological adjustment characteristics that were found to influence FCR [1, 6, 19].

As shown in the final model in Table 3, six characteristics predicted inter-individual differences in the intercept for FCR scores: living alone, changes in spiritual life since the cancer diagnosis, state anxiety prior to surgery (i.e, at enrollment), difficulty coping as a result of disease/treatment, distress related to the initial cancer diagnosis, and the distress (of illness) to family. Overall physical health and FCR scores prior to surgery were the only characteristics that significantly predicted linear and quadratic slope parameters.

To illustrate the effects of each of these characteristics on the intercepts and trajectories of FCR scores, Figure 2 displays the adjusted change curves for FCR scores that were estimated based on differences in the significant predictors reported above. For the continuous variables, higher versus lower differences were calculated based on 1 standard deviation above/below the mean score.

In brief, patients who did not live alone, who experienced greater changes in spiritual life, had higher state anxiety at enrollment, had more difficulty coping, experienced more distress due to the diagnosis, and whose diagnosis caused more distress to family members reported higher FCR scores at enrollment. Patients who reported better overall physical health and higher FCR scores at enrollment demonstrated a steeper decrease in FCR scores, which leveled off approximately 4 months after breast cancer surgery, and then increased slightly at 6 months after surgery.

DISCUSSION

This study is the only one, to our knowledge, that used HLM to evaluate predictors of change in FCR over time in women undergoing surgery for breast cancer. While previous literature demonstrated overall high levels, associated distress, and persistence of FCR [1], the present study highlights the substantial amount of heterogeneity in the experience of FCR prior to surgery and over time in women with breast cancer.

After adjusting for relevant covariates, a number of characteristics were found to predict a higher level of FCR at the beginning of the study: not living alone, change in spiritual life since diagnosis, higher state anxiety, greater difficulty coping as a result of disease and treatment, greater distress related to initial diagnosis, and greater distress of illness to family.

These findings corroborate and build on previous work that examined FCR. Across a number of studies, trait and state anxiety were associated with FCR in women with breast cancer [1, 7, 18, 38, 39]. While specific characteristics of anxiety symptoms were not assessed in this sample, the nature of the thoughts that patients with higher levels of FCR experience is similar to that of obsessions (intrusive, unwanted thoughts) [7]. In addition, patients with higher levels of FCR may have a distinct profile from those with lower levels of FCR, whose thoughts are more similar to “worries” (perceived by the individual as rational and ego-syntonic). In addition, intrusive thoughts, hyperarousal, and avoidance, which are all closely related to anxiety, were found to be associated with higher levels of FCR [17]. Additional work on “negative metacognitions” (e.g., the thought that worrying itself is harmful) suggests that these thoughts are associated with higher levels of FCR in young breast cancer survivors [40]. Future studies need to provide more detailed descriptions of the nature and correlates of anxiety in survivors with FCR, as specific types of anxiety interventions may be warranted for subgroups of patients.

Distress related to the cancer diagnosis and greater difficulty coping were associated with higher levels of FCR in prior work [1, 41]. For example, pre-operative distress predicted FCR post-surgically, at three months, and at twelve months [4]. In terms of coping, self-efficacy (confidence in one’s ability to cope with an experience) was inversely correlated with FCR in breast cancer survivors [39].

Taken together, the characteristics identified in this study that were associated with higher FCR prior to surgery are consistent with the social cognitive theory of coping self-efficacy [42, 43], in particular the role of self-efficacy in posttraumatic recovery [44]. This model posits that an outcome related to threat appraisal (in this case, FCR) is predicted by coping self-efficacy, which in turn is influenced by both adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies. Coping self-efficacy is the individual’s sense that she can cope. While often measured by specific scales [45], self-efficacy in the present study is best represented by the variable “difficulty coping.”

Social influences contribute to coping, but are filtered through the self-efficacy lens. While it may appear paradoxical that not living alone was associated with greater FCR, viewed through the social cognitive lens, it is possible that women with lower coping self-efficacy had more trouble coping with the interpersonal aspects of the diagnosis. Similarly, feeling that one’s illness is causing distress to family members may be more distressing to those with lower coping self-efficacy, leading to greater overall distress and FCR. Previous studies found that interpersonal factors (e.g., negative interactions, perceived lower social support) were related to FCR [18, 19].

While findings regarding the relationship between religious/spiritual coping and FCR are inconsistent [1], our finding that a higher level of spiritual change associated with the cancer diagnosis was associated with greater FCR is consistent with previous work that found a correlation between greater use of religious/spiritual coping and lower FCR. However, one can speculate that the relationship between spiritual change and FCR may be mediated primarily by coping. People who are better able to integrate a new diagnosis into their social, psychological, and spiritual lives (perhaps stressing one of these coping strategies more than the others) may be more confident in their ability to cope with future illness-related events, such as a recurrence. Additional research studies and different approaches to data analysis (e.g., mediation analyses) are needed to clarify the postulated relationships.

Two characteristics, better overall physical health and higher FCR scores at enrollment, significantly predicted steeper declines in FCR scores over the six months of the study. The finding that better physical health predicted a steeper decrease in FCR is a novel finding, as few studies that have examined FCR over time have characterized trajectories of FCR or predictors of those trajectories [1]. A previous study found that a higher number of physical symptoms predicted FCR at one year following a cancer survivorship rehabilitation program in a sample (n=1,281) of diagnostically heterogeneous cancer patients [19]. Taken together, these findings suggest that higher levels of physical symptoms may predict persistence of FCR over time, while better physical health predicts greater reductions in FCR over time. However, given differences in longitudinal analytic methods used as well as variability in measures of physical health, symptoms and FCR, further work is needed to clarify how FCR changes over time in relation to physical symptoms and overall health.

The finding that higher FCR scores at enrollment predicted a steeper decrease in FCR may indicate that these women had more room for FCR to decline, or that, at least in those with higher levels of FCR, some psychological adaptation occurs over time. Further work identifying mechanisms responsible for such adaptation is needed and could point toward interventions specifically targeting those patients with higher FCR scores at diagnosis or treatment initiation.

Several limitations warrant consideration. First, we derived a FCR subscale from a broader QOL instrument. While this subscale has adequate psychometric properties, it was not designed nor validated as a measure of FCR. Future work should examine changes in FCR over time using measures that were developed and validated for this purpose (e.g., the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory [2]). Second, because our sample was relatively homogeneous in terms of demographic characteristics, these findings may not be generalizable to more diverse populations of patients with breast cancer. Third, because we did not assess whether women in this study had current or past diagnoses of anxiety (or other psychiatric) disorders, it is not possible to determine whether the presence of anxiety disorders in some patients may have influenced our results.

Despite these limitations, this work provides a novel perspective on FCR in women with breast cancer. Using HLM, we demonstrated a large amount of inter-individual heterogeneity in women’s ratings of FCR both prior to and for six months after surgery for breast cancer. Further work is needed to identify those women who may be most at risk for FCR both early and later in the disease, treatment, and survivorship phases. Early interventions that target high-risk women, for example by targeting their coping self-efficacy, might help buffer against the persistence of FCR over time. Thus, descriptive longitudinal work, as well as intervention research, are needed to develop both a deeper understanding of FCR as well as effective approaches to reduce this common and distressing condition.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) (CA107091, CA118658), and was supported by NIH/NCRR UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131. Dr. Miaskowski is supported by a grant from the NCI (K05 CA168960) and is an American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor. Dr. Langford is supported by a Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program Postdoctoral Fellowship (W81XWH-11-1-0719). Dr. Merriman is supported by a training grant from the NINR (T32 NR011972). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, Dixon M, Hayden C, Mireskandari S, Ozakinci G. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:300–322. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0272-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simard S, Savard J. Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory: development and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:241–251. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0444-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ness S, Kokal J, Fee-Schroeder K, Novotny P, Satele D, Barton D. Concerns across the survivorship trajectory: results from a survey of cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40:35–42. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.35-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, Huggins ME. The first year after breast cancer diagnosis: hope and coping strategies as predictors of adjustment. Psychooncology. 2002;11:93–102. doi: 10.1002/pon.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vickberg SM. The Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS): a systematic measure of women’s fears about the possibility of breast cancer recurrence. Ann Behav Med. 2003;25:16–24. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2501_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee-Jones C, Humphris G, Dixon R, Hatcher MB. Fear of cancer recurrence--a literature review and proposed cognitive formulation to explain exacerbation of recurrence fears. Psychooncology. 1997;6:95–105. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199706)6:2<95::AID-PON250>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simard S, Savard J, Ivers H. Fear of cancer recurrence: specific profiles and nature of intrusive thoughts. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:361–371. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skaali T, Fossa SD, Bremnes R, Dahl O, Haaland CF, Hauge ER, Klepp O, Oldenburg J, Wist E, Dahl AA. Fear of recurrence in long-term testicular cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2009;18:580–588. doi: 10.1002/pon.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simard S, Savard J. Screening and comorbidity of clinical fear of cancer recurrence. Psychooncology. 2009;18(Suppl 2):S171. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0424-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirai K, Shiozaki M, Motooka H, Arai H, Koyama A, Inui H, Uchitomi Y. Discrimination between worry and anxiety among cancer patients: development of a Brief Cancer-Related Worry Inventory. Psychooncology. 2008;17:1172–1179. doi: 10.1002/pon.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lebel S, Rosberger Z, Edgar L, Devins GM. Emotional distress impacts fear of the future among breast cancer survivors not the reverse. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3:117–127. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Llewellyn CD, Weinman J, McGurk M, Humphris G. Can we predict which head and neck cancer survivors develop fears of recurrence? J Psychosom Res. 2008;65:525–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deimling GT, Bowman KF, Sterns S, Wagner LJ, Kahana B. Cancer-related health worries and psychological distress among older adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;15:306–320. doi: 10.1002/pon.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, Peters ML, de Rijke JM, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J. Concerns of former breast cancer patients about disease recurrence: a validation and prevalence study. Psychooncology. 2008;17:1137–1145. doi: 10.1002/pon.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J. Quality of life and non-pain symptoms in patients with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:216–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGinty HL, Goldenberg JL, Jacobsen PB. Relationship of threat appraisal with coping appraisal to fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2012;21:203–210. doi: 10.1002/pon.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehnert A, Berg P, Henrich G, Herschbach P. Fear of cancer progression and cancer-related intrusive cognitions in breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2009;18:1273–1280. doi: 10.1002/pon.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Perez M, Schootman M, Aft RL, Gillanders WE, Jeffe DB. Correlates of fear of cancer recurrence in women with ductal carcinoma in situ and early invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:165–173. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1551-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehnert A, Koch U, Sundermann C, Dinkel A. Predictors of fear of recurrence in patients one year after cancer rehabilitation: A prospective study. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:1102–1109. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.765063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thewes B, Butow P, Bell ML, Beith J, Stuart-Harris R, Grossi M, Capp A, Dalley D. Fear of cancer recurrence in young women with a history of early-stage breast cancer: a cross-sectional study of prevalence and association with health behaviours. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:2651–2659. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1371-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mellon S, Kershaw TS, Northouse LL, Freeman-Gibb L. A family-based model to predict fear of recurrence for cancer survivors and their caregivers. Psychooncology. 2007;16:214–223. doi: 10.1002/pon.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miaskowski C, Cooper B, Paul SM, West C, Langford D, Levine JD, Abrams G, Hamolsky D, Dunn L, Dodd M, Neuhaus J, Baggott C, Dhruva A, Schmidt B, Cataldo J, Merriman J, Aouizerat BE. Identification of patient subgroups and risk factors for persistent breast pain following breast cancer surgery. J Pain. 2012;13:1172–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Onselen C, Paul SM, Lee K, Dunn L, Aouizerat BE, West C, Dodd M, Cooper B, Miaskowski C. Trajectories of sleep disturbance and daytime sleepiness in women before and after surgery for breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:244–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kyranou M, Paul SM, Dunn LB, Puntillo K, Aouizerat BE, Abrams G, Hamolsky D, West C, Neuhaus J, Cooper B, Miaskowski C. Differences in depression, anxiety, and quality of life between women with and without breast pain prior to breast cancer surgery. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunn LB, Cooper BA, Neuhaus J, West C, Paul S, Aouizerat B, Abrams G, Edrington J, Hamolsky D, Miaskowski C. Identification of distinct depressive symptom trajectories in women following surgery for breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2011;30:683–692. doi: 10.1037/a0024366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karnofsky D, Abelmann WH, Craver LV, Burchenal JH. The use of nitrogen mustards in the palliative treatment of carcinoma. Cancer. 1948;1:634–656. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2003;49:156–163. doi: 10.1002/art.10993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunner F, Bachmann LM, Weber U, Kessels AG, Perez RS, Marinus J, Kissling R. Complex regional pain syndrome 1--the Swiss cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA. Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45:5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheehan TJ, Fifield J, Reisine S, Tennen H. The measurement structure of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. J Pers Assess. 1995;64:507–521. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6403_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fletcher BS, Paul SM, Dodd MJ, Schumacher K, West C, Cooper B, Lee K, Aouizerat B, Swift P, Wara W, Miaskowski CA. Prevalence, severity, and impact of symptoms on female family caregivers of patients at the initiation of radiation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:599–605. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spielberger CG, Gorsuch RL, Suchene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Anxiety (Form Y): Self Evaluation Questionnaire. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bieling PJ, Antony MM, Swinson RP. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Trait version: structure and content re-examined. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36:777–788. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jensen MP. The validity and reliability of pain measures in adults with cancer. J Pain. 2003;4:2–21. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2003.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferrell BR, Wisdom C, Wenzl C. Quality of life as an outcome variable in the management of cancer pain. Cancer. 1989;63:2321–2327. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890601)63:11<2321::aid-cncr2820631142>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Padilla GV, Presant C, Grant MM, Metter G, Lipsett J, Heide F. Quality of life index for patients with cancer. Res Nurs Health. 1983;6:117–126. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770060305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Sage Press; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lebel S, Beattie S, Ares I, Bielajew C. Young and worried: Age and fear of recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Health Psychol. 2013;32:695–705. doi: 10.1037/a0030186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ziner KW, Sledge GW, Bell CJ, Johns S, Miller KD, Champion VL. Predicting fear of breast cancer recurrence and self-efficacy in survivors by age at diagnosis. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39:287–295. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.287-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thewes B, Bell ML, Butow P. Fear of cancer recurrence in young early-stage breast cancer survivors: the role of metacognitive style and disease-related factors. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2059–2063. doi: 10.1002/pon.3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waldrop DP, O’Connor TL, Trabold N. “Waiting for the other shoe to drop:” distress and coping during and after treatment for breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2011;29:450–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heitzmann CA, Merluzzi TV, Jean-Pierre P, Roscoe JA, Kirsh KL, Passik SD. Assessing self-efficacy for coping with cancer: development and psychometric analysis of the brief version of the Cancer Behavior Inventory (CBI-B) Psychooncology. 2011;20:302–312. doi: 10.1002/pon.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Philip EJ, Merluzzi TV, Zhang Z, Heitzmann CA. Depression and cancer survivorship: importance of coping self-efficacy in post-treatment survivors. Psychooncology. 2013;22:987–994. doi: 10.1002/pon.3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benight CC, Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: the role of perceived self-efficacy. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:1129–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chesney MA, Neilands TB, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Folkman S. A validity and reliability study of the coping self-efficacy scale. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11:421–437. doi: 10.1348/135910705X53155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]