Abstract

Disorders of pain neural systems are frequently chronic and, when recalcitrant to treatment, can severely degrade the quality of life. The pain pathway begins with sensory neurons in dorsal root or trigeminal ganglia and the neuronal subpopulations that express the TRPV1 ion channel transduce sensations of painful heat and inflammation, and play a fundamental role in clinical pain arising from cancer and arthritis. In the present study we elucidate the complete transcriptomes of neurons from the TRPV1 lineage and a non-TRPV1 neuro-glial population in sensory ganglia through the combined application of next-gen deep RNA-Seq, genetic neuronal labeling with fluorescence-activated cell sorting, or neuron-selective chemoablation. RNA-Seq accurately quantitates gene expression, a difficult parameter to determine with most other methods especially for very low and very high expressed genes. Differentially expressed genes are present at every level of cellular function from the nucleus to the plasma membrane. We identified many ligand receptor pairs in the TRPV1 population suggesting that autonomous presynaptic regulation maybe a major regulatory mechanism in nociceptive neurons. The data define, in a quantitative, cell population specific fashion, the molecular signature of a distinct and clinically important group of pain-sensing neurons and provide an overall framework for understanding the transcriptome of TRPV1 nociceptive neurons.

Keywords: pain, nociception, RNA-Seq, transcriptome, dorsal root ganglion, C-fibers, Aδ fibers, TRPV1, capsaicin, resiniferatoxin, neuropeptides, autocrine, paracrine, GPCR, TRP-channels, bradykinin, Cre, glutamate, kainate, AMPA receptors, metabotropic glutamate receptors, cholinergic receptors, potassium channels, maxi K+ channels, natriuritic polypeptide B, Nppb, galanin, somatostatin, GDNF, BDNF, NGF, MCP1, CCL1, CCL2, TrkA, TrkB, TrkC, c-kit, c-ret, synaptoneurin, Piezo, Vglut1, P2X3, neurexophillin, neurexin, cerebellin, P2Y receptors, P2X3 receptors, ectonucleotidases, adenosine receptors, purinergic receptors, CDK5, tyrosine hydroxylase, hippocalcin, NAV1.7, NAV1.8, NAV1.9, Hox genes, homeobox

INTRODUCTION

Detailed investigations of the molecular biology of nociceptive neurons are key elements for advancing basic knowledge of pain-sensing neural circuits and translational investigations for pain control, but their complete molecular repertoire, their transcriptome, has not been fully ascertained. The subset of nociceptive Aδ and C-fiber primary afferents that express the TRPV1 ion channel transduce signals arising from exposure to painful heat, inflammatory and chemical stimuli, and low pH.63,91 Chemoablation of these neurons and/or their axonal projections using resiniferatoxin (RTX), a potent vanilloid agonist, rapidly and effectively eliminates nociceptive input.39,68 Loss of TRPV1 neuronal input yields analgesia to acute experimental nociceptive stimuli in rodents or bone cancer pain from osteosarcoma in companion dogs.8 In humans, intrathecal administration of RTX is being evaluated in intractable cancer pain, <http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00804154> and preliminary results suggest sustained improvement in pain symptoms.29,31,54 Based on their pivotal role, the precise molecular signature of TRPV1-expressing DRG neurons is hypothesized to be critical for understanding the molecular biology of nociception and the ability to respond to tissue damage and inflammatory clinical pain.

RNA-Seq presents several unique attributes for the investigation of molecular interrelationships,28 although methods including subtraction cloning, SAGE, and microarrays have been evaluated.6,46,103 We examine the TRPV1 neuronal transcriptome by combining RNA-Seq with genetic and chemoablative strategies for enriching/deleting TRPV1 neurons from sensory ganglia. Neurons from bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC)-transgenic, TRPV1-promoter-Cre recombinase mice expressing red fluorescent protein were isolated by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). In the adult, this has the advantage of broadly including the majority of nociceptive modalities, itch, and several other modalities.1,59–62,77,79,104 To provide a contrasting transcriptome, the TRPV1-lineage neurons were eliminated by expressing diphtheria toxin (DTA) using the same BAC-TRPV1-promoter line of mice.62 The cells remaining in the DRG were then subjected to RNA-Seq. To confirm the mouse genetic manipulations, we injected rat trigeminal ganglion with RTX to remove TRPV1-expressing neurons.39 As with the DTA lesion, the ganglionic cells remaining after the RTX lesion were subjected to RNA-Seq. These manipulations yield three differentially-expressed populations of DRG transcripts: (1) TRPV1-lineage (TRPV1L) or (2) TRPV-depleted (TRPV1D) populations, and (3) those equally expressed/common to both groups. These RNA-Seq data outline the beginnings of a “nociceptome” and define critical molecular interrelationships for experimental and in silico analyses.

Here we report multiple new transcripts in the TRPV1L population such as the hippocalcin family of calcium binding proteins and receptor subunits related to nociceptive or analgesic processes.2,74 We also identify interrelated gene families hypothesized to be involved in potential autocrine or paracrine presynaptic molecular microcircuits which can control nerve terminal excitability. For example, transcripts coding for a purinergic ion channel –> adenosine generating enzyme –> G-protein coupled receptor cascade are abundantly present in TRPV1L neurons and may sequentially increase and then decrease nociceptor excitability following tissue damage and ATP release.107 Individually, all three elements in this cascade have been targets of analgesic manipulations or drug development efforts.27,42,89,107 Potential autocrine regulatory loops are revealed by co-expression of neuropeptide-receptor pairs suggesting multiple mechanisms for dynamic, autonomous regulation of nociceptive nerve terminal excitability. These data highlight molecular pathways and mechanisms involved in acute and neuropathic pain, neurological disorders affecting peripheral nerve, and potential routes to new therapies.

METHODS

Animal Studies

Animals were maintained with water and food ad libitum and housed in groups of 2–3 on a 12 hr light-dark cycle. The procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed in accordance with the NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and the International Association for the Study of Pain.

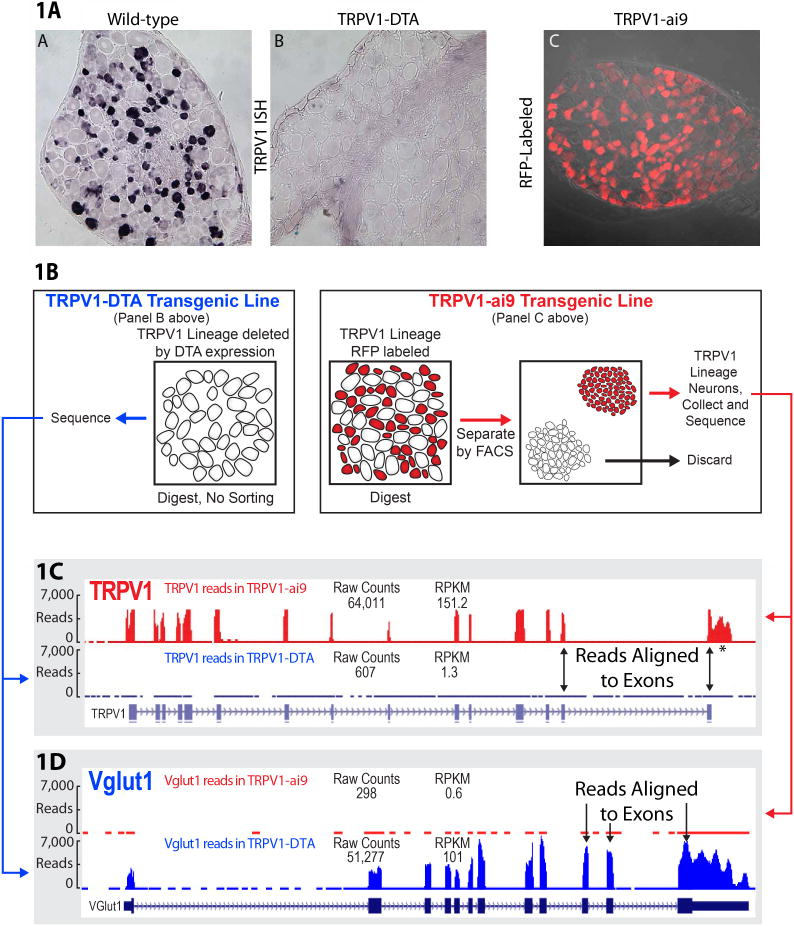

TRPV1-Lineage DRG Labeling and Isolation

Transgenic mice were engineered to express Cre recombinase under control of the TRPV1 promoter.62 These TRPV1-Cre animals were crossed with the promoter line ai9 ROSA-stop-tdTomato creating TRPV1-ai9 mice whose dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and trigeminal ganglia selectively contained neurons marked with the red fluorescent protein tdTomato (Figure 1A, Panel C). DRG tissue depleted of the TRPV1-lineage population was obtained by Cre-mediated excision of a floxed transcriptional stop 5′ to the diphtheria toxin fragment A coding sequence.62 TRPV1-Cre dependent excision activates DTA expression resulting in the specific ablation of Cre-expressing TRPV1-lineage neurons. Figure 1A panels A and B show TRPV1 in situ hybridization in the wild type and diphtheria toxin expressing ganglion. The TRPV1 lineage neurons have been removed after diphtheria toxin expression (Figure 1A, panel B). Figure 1A panel C shows the red fluorescent protein expression in the TRPV1-lineage neurons. The selectivity of Cre expression has been confirmed using double label in situ hybridization.62 To prepare the material for RNA-Seq (Figure 1B), dorsal root ganglia were dissected from two to three groups of 10 mice from each of the two genotypes (TRPV1-DTA and TRPV1-ai9). The DRGs were dissociated enzymatically, and, for the TRPV1-ai9 mice, the cell suspension was subjected to cell sorting on a FACS Vantage SE (BD Biosciences) at 18 psi. DAPI staining was used for exclusion of dead cells. RFP+ neurons were sorted to >97% purity and were collected and extracted for total RNA. For the TRPV1D mice, the dissociated cells were directly extracted for total RNA. This procedure is shown diagrammatically in Figure 1B. Figure 1C and 1D illustrate two things: read enrichment and read alignment. For each gene in panels C and D, the exon structure is shown below the read panels. Note that the histogram-like accumulation of reads aligns to the exon structure. Figure 1C shows the enrichment of TRPV1 sequences in the RFP-sorted, TRPV1-lineage neurons and the lack of TRPV1 reads in the TRPV1-DTA preparation. In contrast, Figure 1D shows the enrichment of Vglut1 reads in the DTA preparation and the lack Vglut1 reads in the RFP-sorted, TRPV1-lineage neurons. Both of these genes were picked for illustrative purposes because they were very strongly differentially expressed and Vglut1 is a marker for large diameter proprioceptive neurons. For example, in the TRPV1L neuron, 63,000 reads from the deep RNA sequencing runs align with the TRPV1 exons. An exception is indicated with an asterisk, which denotes a 3′ extension and this is discussed further in relationship to Figure 6. These aspects are considered further in the DRG RNA-Seq metrics section.

Figure 1. Assessment of TRPV1 Enrichment Manipulation.

1a. Results of in situ hybridization for TRPV1 are shown for (a) wild type mouse DRG, (b) TRPV1D (TRPV1-DTA), and (c) TRPV1L (TRPV1-ai9) ganglia. Figure 1 B illustrates the procedure for cell deletion using the TRPV1-DTA transgenic mouse line and isolation of the RFP TRPV1L neurons. The panels of Figure 1C and 1D show alignments of raw reads for TRPV1 and Vglut1 (vesicular glutamate uptake, Slc17a7) mRNAs to their exon structures in the TRPV1L neurons and the TRPV1D preparation. Reference sequences are shown below the reads (the asterisk denotes a 3′ extension of the TRPV1 transcript which is analyzed further in Figure 6). Both the alignment and in situ hybridization show that the TRPV1 BAC-transgenic RFP labeling and FACS strongly enriched for TRPV1 and that the DTA lesion is thorough, as almost no TRPV1 transcripts are detectable in ganglia from the TRPV1D mice. Both of these genes were picked for illustrative purposes because they were very strongly differentially expressed. Vglut1 is a marker for large diameter proprioceptive neurons.10 These aspects are considered further in the DRG RNA-Seq metrics section.

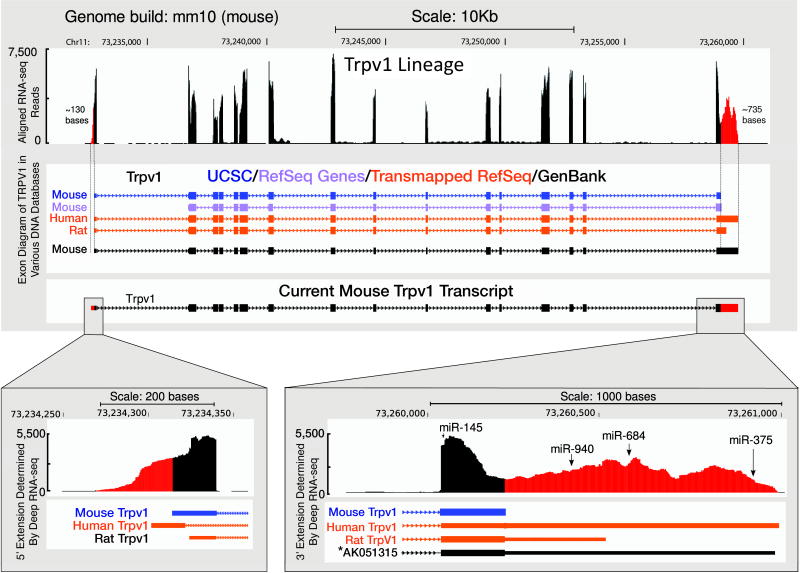

Figure 6. Illustration of Mouse 5′ and 3′ UTR Annotation.

The region in red corresponds to the 5′ and 3′ UTR extensions using the TRPV1L deep sequencing data. The location of three evolutionarily conserved miRNA binding sites are identified in the 3′extension. The region of the mouse genome (mm10) was extracted and aligned with the corresponding region in rat (rn5) and human (hg19) genomes using the UCSC genome table browser. The aligned sequence was used as input by TargetScan to predict the miRNA binding sites. Please note that NCBI Mus musculus Annotation Release 104 now corresponds to the extensions which we illustrate and the exact sequence in SFig3 includes these data.

Intratrigeminal resiniferatoxin injection

The potent TRPV1 agonist resiniferatoxin (RTX) was used to deplete the adult rat sensory ganglion of TRPV1-expressing neurons. RTX activates the TRPV1 ion channel and produces a cytoplasmic calcium overload that selectively kills TRPV1-expressing primary afferent neurons. RTX was stereotaxically injected into the trigeminal ganglion as described earlier (Karai 2004).39 Briefly, the rat is placed in a stereotaxic frame; the coordinates for the intratrigeminal injection were 2.5 mm posterior and 1.5 mm lateral to bregma; the depth is determined during the course of needle placement. The main technical considerations are (a) use of a shallow bevel needle (45° custom ordered from Hamilton), and (b) once the needle gently contacts the base of the skull it is retracted 0.5 mm so the opening of the needle bore is embedded completely within the ganglionic tissue. Ganglia were removed at day 10 after microinjection.

Technical Caveats

Some alterations in gene expression may have occurred as a result of genetic manipulations and/or tissue preparation steps. The acute dissection of ganglion and enzymatic liberation of cell followed by FACS may have induced some genes. The FACS sorting is a relatively brief procedure (10 minutes) although the pressure for running the sorter is a critical variable. For example PSIs above 20 tended to lyse the cells and reduce or completely eliminate intact RNA. The microinjection may also have resulted in some alterations related to the lesion that were not fully resolved by day 10 when we sampled the tissue.

RNA Isolation

Rats were euthanized by CO2 exposure. The trigeminal ganglia were removed from the base of the skull and the L4 and L5 DRGs were removed after laminectomy. Tissues were frozen immediately in dry ice, and stored at −80°C until processed. Samples were homogenized in l ml Qiazol reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) using a Polytron homogenizer. The RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) plus an additional step of DNase treatment was used to isolate total RNA. The RNA integrity was assessed by gel electrophoresis on Agilent Bioanalyzer. Samples with a RNA integrity number (RIN) above 8.5 were sequenced.

Sample Preparation and Next-Gen Sequencing

Poly A+ isolation, size fragmentation, cDNA synthesis, size selection, ligation of Illumina (San Diego, CA) paired end adaptors and next-gen sequencing were performed at the NIH Intramural Sequencing Center (NISC) according to their standard protocols. Briefly, Poly-A selected mRNA libraries were constructed from 1 μg total RNA using the Illumina TruSeq RNA Sample Prep V2 Kits according to manufacturer’s instructions except where noted. The cDNAs were fragmented to ~275 bp using a Covaris E210 machine. Amplification was performed using 10 cycles to minimize the risk of over-amplification. Unique barcode adapters were applied to each library. Equal volumes of individual libraries were pooled and run on a MiSeq Illumina. The libraries were then repooled based on the MiSeq demultiplexing results. The pooled libraries (N=4 per pool) were sequenced on two lanes of an Illumina HiSeq2000 using version 3 chemistry. The data were processed using RTA version 1.13.48 and CASAVA 1.8.2. For the TRPV1L and D samples, we sequenced to a depth of approximately 166 and 178 million paired end reads of 100 bases each on the HiSeq 2000. An earlier run on an Illumina Genome Analyzer (GAIIX) provided an average of 36.7 million reads of 35 bases each; the correlation coefficients from the two platforms (after removing unannotated genes and genes expressed below 1 RPKM) were 0.93 and 0.94 (Figure S1).

Mapping and Assembly of RNA-Seq Reads

FastQC (version 0.10.0) was used to run preliminary QC analyses. All reads had an average minimum per base sequence quality score above 28, indicative of a high quality sequencing run, and did not require trimming before being mapped. RNA-Seq unified mapper program (RUM v2.05) was selected to align the 100 base reads to the appropriate genome because of the accuracy and speed of this algorithm over other popular aligners for next-generation sequencing.26 Mouse mm10 and rat rn4 assemblies were used for mapping by RUM yielding three groups of reads: unique, non-unique, and not mapped. A summary of unique and non-unique mapped reads can be viewed in Table S1. The mapped reads were assembled using gene models from RefSeq, UCSC, and Ensembl databases. The UCSC table browser was used to convert the various database accession ids (used as ids in RUM) to gene symbols. A perl script was used to select one instance for each gene from the different isoforms and/or gene models. The selection was based on the number of reads mapped to the gene model, and the database source of the gene model. Preference was given to the model that accounted for the most reads mapped and RefSeq and UCSC databases were given preference over Ensembl. By selecting the gene instance with the highest read count, the major isoform of each gene or the most well supported gene structure was considered for differential expression. While we did not perform extensive analysis of alternate splicing events, we looked at isoforms of the genes in Table S2 (TRPV1L 5X or greater fold difference), and confirmed that, overwhelmingly, the assignment of the gene to either the TRPV1 lineage or depleted group was not affected by the choice of the isoform. There are 269 genes in Table S2 and of those 51 have one or more isoforms. From the genes that have isoforms, only 2 genes (3%) had an isoform with an expression level above 1 RPKM that was opposite from the selected major isoform.

Technical Caveats

The RPKM expression values presented within this manuscript are determined by the mapping tool used and the selected gene model; minor differences in values are expected across different RNA-Seq mapping tools and with the use of different gene models. With poly-A selection, we mainly detect protein coding transcripts. It is noteworthy that while the mouse genome is very well annotated, increasing amounts of RNA-Seq data make genome re-annotation a fluid and continuously evolving process, thus remapping of the RNA-Seq data may result in some new genes being discovered.

Immunohistochemistry: animals were deeply anesthetized with ketamine or pentobarbital and perfused transcardially with cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. For double labeling, tissues were cryoprotected in 20% sucrose, frozen, and blocks were sectioned (10μ) by Histoserv, Inc (Germantown, MD). Slide mounted sections were washed 3×1 min in HEPES Immunostaining Buffer (HIB) containing 145mM NaCl, 5mM KCl, 1.8mM CaCl2, 0.8mM MgCl2 and 10mM HEPES, pH 7.4, followed by washing 3×1 min in dH2O. Sections were subjected to antigen retrieval by microwaving for 2 min at 300 W, cooling for 1 min, microwaving for an additional 4 min at 180 W and then cooling for 30 min followed by washing 3×1 min in HIB then 3×1 min in dH2O. Sections were blocked with 10% normal goat serum for 1 hr at RT and then washed 3×1 min in dH2O. The sections were then incubated at RT for 1 hr with rabbit anti-TRPV1 antibody in HIB (1:1000, BioReagents). Sections were washed 3×1 min in HIB then 3×1 min in dH2O prior to incubating for 1 hr at RT with Alexa Fluor 647 donkey anti-rabbit antibody in HIB (1:150, Abcam). Sections were washed 3×1 min in HIB then 3×1 min in dH2O prior to coverslipping and imaged using a Zeiss Axio Imager.Z2. Slides were incubated overnight in HIB at 4°C to remove coverslip. To remove the initial primary and fluorescent antibodies, sections were subjected to a second round of antigen retrieval and stained as above with rabbit anti-hippocalcin antibody (1:10,000, Abcam) followed by donkey anti-rabbit FITC (1:150, Jackson). Images from both stainings were aligned based on DAPI to determine co-localization.56

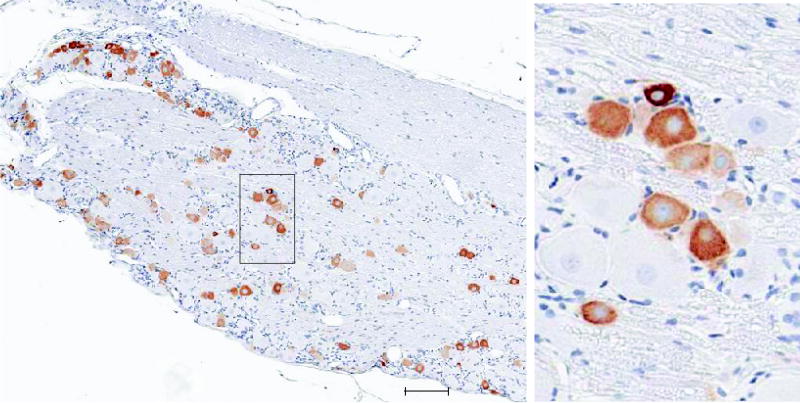

For TRPV1 alone, six micron sections were cut from a paraffin block containing the L4 and L5 dorsal root ganglia. Following deparaffinization and epitope unmasking with Target Retrieval Solution (S1700, Dako, Carpinteria, CA) at 95° C for 20 min, sections were blocked with 10% normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) and incubated overnight at 4° C with the primary TRPV1 antibody. Antibody detection was performed using Vectastain Elite Rabbit IgG and Peroxidase Substrate Kits (SK-4700 and SK-4100, Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA). Sites of peroxidase activity were visualized using 3,3-diaminobenzidene tetrahydrochloride (DAB); sections were then counterstained with hematoxylin. Control specimens for the assessment of non-specific binding were processed in an identical way, except for omission of the primary antibody. Histological sections were visualized by scanning with a 20X objective in an Aperio ScanScope slide scanner. A typical section from whole DRG is shown with a subsection enlarged.

5′ and 3′ UTR extension

The region corresponding to the mouse genome (mm10) that was covered by at least 50 bases was extracted and aligned with the corresponding region in rat (rn5) and human (hg19) genomes using the UCSC genome table browser.40 The aligned sequences were used as input into the TargetScan algorithm47 to report evolutionary conservation of miRNA seed regions.

RESULTS

DRG RNA-Seq Metrics

RNA-Seq and Level of Expression

RNA-Seq data are derived from sequencing of nucleic acid and an alignment of the sequence to a reference genome which results in accurate quantitation and unambiguous assignment of gene identity; the process yields highly reproducible results.51,57,66 The data reported here derive from 21 samples (Supplemental Table 1) in four different cohorts, (a) four sequencing runs averaging 34 and 172 million paired end reads of the TRPV1L and TRPV1D mouse Bac transgenic manipulations (Figure 1A), (b) intratrigeminal rat resiniferatoxin cell deletion (N=7, 4 controls and 3 lesioned animals), (c) basal rat DRG (N=9), and (d) a rat “mixed tissue” preparation consisting of equal amounts of total RNA from cerebral cortex, cerebellum, midbrain, hypothalamus, hindbrain, spinal cord, retina, pituitary, heart, liver, lung, kidney, skeletal muscle, small intestine and adrenal gland (113 million paired end reads) for a total of ~2.5 billion individual reads. The treatments and total reads per tissue sequenced are supplied in Supplemental Table 1. The methodological pipeline and criteria used for mapping and filtration are detailed in Supplemental Figure 1 and frequency histograms comparing level of gene expression to number of genes in these different preparations can be found in Supplemental Figure 2. This latter figure allows an appreciation of the overall distribution and number of genes, out of the total of ~12,500 ganglionic genes that are expressed at low, medium, and high levels.

RNA-Seq Unified Mapper (RUM) was used for alignment of sequence reads to the genome; the number of mapped reads is expressed as reads per kilobase of transcript per million bases sequenced (RPKM);26 an example of a typical alignment is seen in Figure 1C and 1D. Genes with >20 raw reads are considered expressed and those with an RPKM of ≥1 are analyzed in this paper. In instances where families of genes are analyzed, low expressed genes are not excluded from discussion. It is recognized that ≥ 1 RPKM is a stringent criterion. A more relaxed criterion would include a portion of the ~3,300 genes expressed between 0.1 and 1.0 RPKM a portion of which are included in a supplemental table (STable7). Behavioral and drug studies suggest that genes with relatively low expression are capable of having a functional impact on nociceptive processes with pharmacological implications. An example is the bradykinin 2 receptor GPCR (Bdkrb2), which is expressed at 1.3 RPKM. Bradykinin is a well-known peptide algesic mediator, and Bdkrb2 antagonists have been tested as analgesic agents.76,87 Thus, a recurrent theme in this paper is that the absolute level of expression may not be a full predictor of functional impact and application of additional genetic targets and labeling will be required to obtain a complete transcriptional matrix of nociceptive neuronal populations.

Mouse DRG

Mapping the 170 million read mouse TRPV1L and TRPV1D ganglionic gene expression data with RUM yielded ~25,000 distinct transcripts. Functionally unannotated and non-coding transcripts were separated out, at which point ~16,200 gene transcripts met the inclusion criterion of 20 raw reads or more. Out of this group, 12,683 transcripts had a RPKM of one or greater, our main criterion for further analysis. RNA-Seq to a depth of 36.7 million unpaired reads on the Illumina GaIIx yielded 12,583 expressed transcripts. The correspondence between the number of transcripts is consistent with data from chicken99 and observations that ultra-high sequencing depth mainly aids detection of non-coding, low-expression RNA’s.93 Taken together, our data indicate that cells of the DRG express about 12,500 well expressed, functionally annotated genes transcripts coding for defined proteins.

Rat DRG

The rat sequencing consisted of 40 ± 5.6 million paired end reads (N=9) and yielded 10,992 distinct transcripts that met the eligibility criteria of >20 raw reads, ≥1 RPKM and annotated in either the Refseq, UC Santa Cruz, or Ensembl databases. Examination of the data after filtration and annotation exclusion showed an apparent lower number of genes (~1500) expressed in rat which reflects the more complete annotation of the mouse genome rather than absence of the transcript in the rat.

Assessment of TRPV1 Enrichment and Depletion

Results of in situ hybridization for TRPV1 are shown in Figure1A for (a) wild-type, (b) TRPV1D, (TRPV1-DTA) and (c) TRPV1L (TRPV1-ai9) mouse DRG. The use of FACS to isolate RFP-labeled neurons yielded strong differential expression: a 100-fold enrichment of TRPV1 transcripts was observed compared to the ganglia in which TRPV1-lineage neurons are eliminated. It is important to note that, because of the sorting, most of the transcripts in the TRPV1L preparation are of neuronal origin. Throughout this paper, we use the terms “differentially” or “predominantly” to mean a higher level of expression in one population vs. another, but frequently the difference in expression is not absolute.

The DTA lesion is thorough and no TRPV1 neurons are detectable in ganglia from these mice. The resulting transcriptome analysis shows that TRPV1 mRNA was nearly absent in the DTA lesioned transcriptome, while other genes are strongly differentially expressed in the TRPV1D ganglia (Figure 1C, 1D). Vglut1 (Slc17a7) a vesicular glutamate transporter is 170-fold differentially expressed in TRPV1D ganglia compared to the TRPV1L neurons (Figure 1D) and immunocytochemistry shows it is mainly localized to large diameter proprioceptive DRG neurons.10 Osteopontin (Spp1) is also strongly differentially expressed in the TRPV1D ganglia and is highly expressed in non-nociceptive muscle spindle afferents as seen with immunocytochemistry.33 Population specific expression extends to developmentally important transcription factors such as short stature homeobox 2 (shox2), which shows a 38-fold enriched expression in the TRPV1D population and is a developmental determinant for a subpopulation of TrkB expressing DRG neurons,82 consistent with TrkB expression in the TRPV1D population (Figure 2). While the neuronal components of the TRPV1D transcriptome are mainly non-nociceptive, this preparation also contains satellite cells, Schwann cells and blood vessels. The same cellular heterogeneity applies to intact ganglia. Thus, in whole rat ganglia and TRPV1D mouse preparation we detect substantial amounts of myelin protein zero and proteolipid myelin protein 22 transcripts from Schwann cells, and even hemoglobin transcripts (Hbb-a1 and -a2) from reticulocytes (Figure S2).

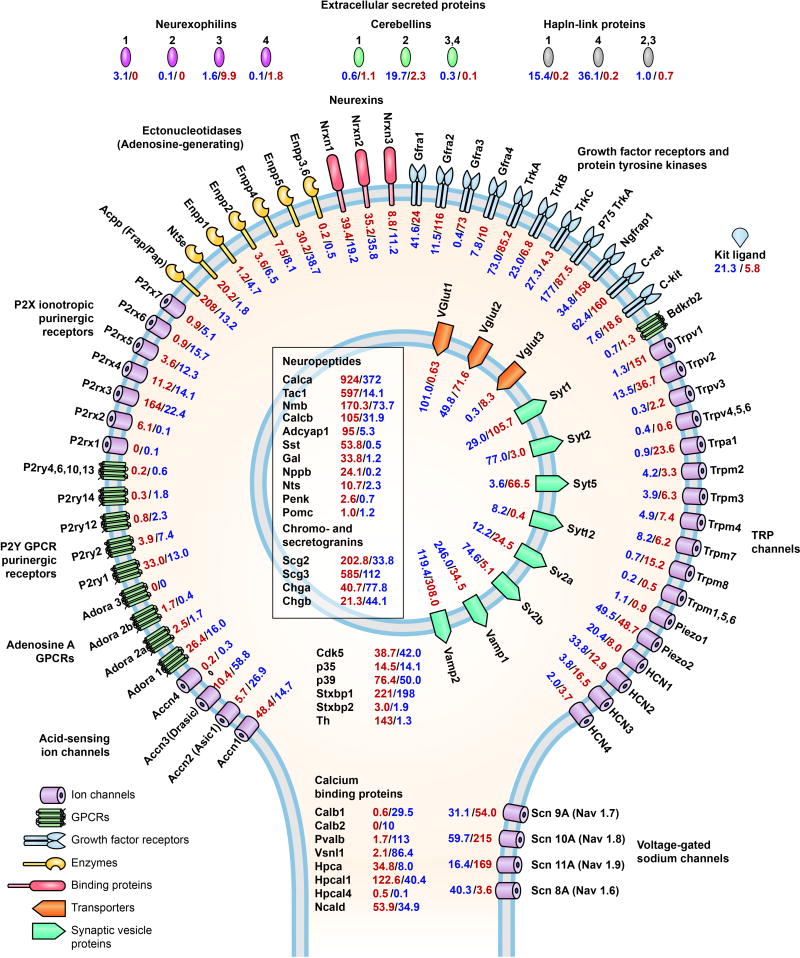

Figure 2. Primary Afferent Nerve Ending.

This figure illustrates a primary afferent nerve ending and shows levels of transcripts coding for families of ion channels, enzymes, GPCRs, growth factor receptors, intracellular and vesicular proteins, neuropeptides, and extracellular linking proteins placed in the cellular locations of the corresponding proteins. The quantitative values for the TRPV1L neurons are in red and the TRPV1D population in blue. In the figure, the outside rim is formed by the plasma membrane and a round synaptic vesicle (light blue) is in the interior. The RPKM values for adenosine, P2Y purinergic/pyrimidine GPCRs, P2X3 purinergic ionotropic receptors, as well ectonucleotidases that can convert ATP, ADP or AMP to adenosine are arrayed on the left side. Neurexins, neurexophilins, cerebellins, and the Halpn extracellular link proteins found in perineuronal nets are at the top. Growth factor tyrosine kinase receptors, TRPA1, the TRPV and TRPM families, putative mechanosensitive Piezo 1 and 2, and the hyperpolarization activated cyclic nucleotide-gated potassium channel (HCN) family of ion channels are on the right side. At the bottom are several voltage gated sodium channels, the families of parvalbumin and hippocalcin calcium binding proteins, and proteins related to cyclin-dependent protein kinase 5 (Cdk5).97 [Gene symbols/names- Nt5e: 5′-ectonucleotidase; Enpp[1,2,4,5,6]: ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase; Gfra[1,2,3,4]: glial cell line derived neurotrophic factor family receptor alpha; TrkA: Ntrk1, neurotrophic tyrosine kinase, receptor, type 1; TrkB: Ntrk2, neurotrophic tyrosine kinase, receptor, type2; TrkC: Ntrk3, neurotrophic tyrosine kinase, receptor, type 3; p75 TrkA: nerve growth factor receptor; Ngfrap1: nerve growth factor receptor associated protein 1; Bdkrb2: bradykinin receptor B2; HCN[1,2,3,4]: hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic nucleotide-gated K+ channel; Vglut1: Slc17a7, solute carrier family 17 (vesicular glutamate transporter), member 7; Vglut2: Slc17a6, solute carrier family 17 (vesicular glutamate transporter), member 6; Vglut3: Slc17a8, solute carrier family 17 (vesicular glutamate transporter), member 8; Syt[1,2,5,12]: Synaptotagmin; Sv2[a,b]: synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2; Vamp[1,2]: synaptobrevin, vesicle-associated membrane protein; Calca, Calcb: Cgrp[alpha, beta], calcitonin gene-related polypeptide; Tac1: tachykinin 1; Nmb: neuromedin B; Adcyap1: adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide 1 (PACAP); Sst: somatostatin; Gal: galanin; Nppb: natriuretic peptide B; Nts: neurotensin; Penk: preproenkephalin; Pomc: proopiomelanocortin; Scg[2,3]: secretogranin; Chga: chromogranin A; Chgb: chromogranin B (also called secretogranin 1); Cdk5: cyclin-dependent kinase 5; p35: Cdk5 regulatory subunit 1; p39: Cdk5 regulatory subunit 2; Stxbp1: Munc18-1, syntaxin binding protein 1; Stxbp2: Munc18b, syntaxin binding protein 2; Th: tyrosine hydroxylase; Calb[1,2]: calbindin; Pvalb: parvalbumin; Vsnl1: visinin-like 1; Hpca: hippocalcin; Hpcal[1,4]: hippocalcin-like; Ncald: neurocalcin delta

TRPV1L Transcripts: Molecular Signatures of Nociceptive Neurons

Quantitative Aspects and Guide to the Tables

In the following sections, two aspects of gene expression are considered: the absolute level of expression (RPKM) and the fold-differential expression; both facets are captured in Table 1 and Figure 2. We mainly focus on transcripts coding for known or potential mediators of nociceptive transduction or analgesic drug actions. All genes in Table 1 and the supplemental tables are listed by their gene symbol as found in NCBI gene database. However, in the literature they may be identified by many aliases or common names, thus, finding the entry may require accessing the gene menu of NCBI < www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/. Additionally, the accession id is provided in the supplemental tables to identify the exact gene isoform that was used in the analysis, which in almost all cases is the main splice variant (see methods). Genes expressed below 1 RPKM are included in a separate tabulation (Table S7). If a particular gene of interest is not found, it either (a) may not be expressed or (b) the annotation may not yet be validated in the current mouse genome build; for mouse the latter is less likely. To facilitate gene searches we supply supplemental Table 8 which is alphabetized based on gene symbol. This table is particularly useful for looking up gene families.

Table 1.

Molecular Signature of TRPV1L Neurons.

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Lineage RPKM | Depleted RPKM | Adjusted Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand and Voltage Gated Ion Channels, Channel Subunits and Channel Interacting proteins | ||||

| Scn11a | sodium channel, voltage-gated, type XI, alpha; Nav1.9 | 169.2 | 16.4 | 10.3 |

| P2rx3 | purinergic receptor P2X, ligand-gated ion channel, 3 | 163.6 | 22.4 | 7.3 |

| Trpv1 | transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily V, member 1 | 151.2 | 1.3 | 105.3 |

| Kcnip4 | a-type potassium channel modulatory protein 4 | 133 | 19.6 | 6.8 |

| Grik1 | glutamate receptor, ionotropic, kainate 1 | 130.8 | 8.6 | 15.1 |

| Kcnip2 | a-type potassium channel modulatory protein 2 | 102.2 | 14.8 | 6.9 |

| Scn3b | sodium channel, voltage-gated, type III, beta | 39.9 | 7.8 | 5.1 |

| Trpc3 | transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily C, member 3 | 38.9 | 4.8 | 7.9 |

| Kcnh6 | potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily H (eag-related), member 6, KV11.2 | 30.6 | 2.5 | 11.9 |

| Chrna6 | cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha polypeptide 6 | 30.3 | 4 | 7.4 |

| Trpa1 | transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily A, member 1 | 23.6 | 0.9 | 22.6 |

| Kcnmb1 | potassium large conductance calcium-activated channel, subfamily M, BKbeta1, Maxi K β1 | 16.3 | 3.6 | 5 |

| Trpm8 | transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily M, member 8 | 15.2 | 0.7 | 18.4 |

| Kcnc2 | potassium voltage gated channel, Shaw-related subfamily, member 2, KV3.2 | 9.9 | 0.7 | 12.6 |

| Kcnk12 | potassium channel, subfamily K, member 12, THIK2, tandem pore domain K+ channel | 8.9 | 0.8 | 9.9 |

| G-protein Coupled Receptors and Associated Proteins | ||||

| Rgs4 | regulator of G-protein signaling 4 | 606 | 125.2 | 5 |

| Rgs10 | regulator of G-protein signaling 10 | 222.9 | 28.6 | 7.8 |

| Mrgprd | MAS-related GPR, member D | 125.4 | 4.2 | 29.1 |

| Gnb4 | guanine nucleotide binding protein (G protein), beta 4 | 68 | 8.1 | 8.3 |

| F2rl2 | coagulation factor II (thrombin) receptor-like 2; PAR3 | 57.5 | 10.1 | 5.6 |

| Gna14 | guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha 14 | 53 | 4.9 | 10.6 |

| Lpar3 | lysophosphatidic acid receptor 3 | 45.8 | 1.9 | 22.8 |

| Mrgpra3 | MAS-related GPR, member A3 | 37.4 | 6.3 | 5.8 |

| Rgs3 | regulator of G-protein signaling 3 | 37.4 | 6.5 | 5.7 |

| Mrgprx1 | MAS-related GPR, member X1 | 28.6 | 1.3 | 21.3 |

| Rgs8 | regulator of G-protein signaling 8 | 22.6 | 0.8 | 26 |

| Ptgdr | prostaglandin D receptor | 20 | 1.4 | 13.3 |

| Mrgprb5 | MAS-related GPR, member B5 | 17.3 | 0.7 | 21.9 |

| Gpr35 | G protein-coupled receptor 35 | 17.3 | 1 | 15.5 |

| Npy1r | neuropeptide Y receptor Y1 | 17.3 | 2.4 | 7 |

| Npy2r | neuropeptide Y receptor Y2 | 14.6 | 1.4 | 10 |

| Agtr1a | angiotensin II receptor, type 1a | 13.3 | 1.6 | 8 |

| Lpar5 | lysophosphatidic acid receptor 5 | 13.1 | 0.9 | 13.1 |

| Sstr2 | somatostatin receptor 2 | 11.2 | 0.3 | 28.5 |

| Neuropeptides and Cytokines | ||||

| Calca* | calcitonin-related polypeptide alpha; CGRP | 924.2 | 372.1 | 2.5 |

| Tac1 | tachykinin 1; substance P | 597.7 | 14.1 | 42 |

| Calcb* | calcitonin-related polypeptide beta; CGRP2 | 105.4 | 31.9 | 3.3 |

| Adcyap1 | adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide 1; PACAP | 95 | 5.3 | 17.6 |

| Cartpt | CART prepropeptide | 64.7 | 2.1 | 29 |

| Sst | somatostatin; growth hormone release-inhibiting factor | 53.8 | 0.5 | 97.3 |

| Gal | galanin | 33.8 | 1.2 | 25.7 |

| Nppb | natriuretic peptide precursor type B | 24.1 | 0.2 | 86.9 |

| Ccl1 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 1 | 7.8 | 0.3 | 22.5 |

| Nts* | neurotensin | 10.7 | 2.3 | 4.4 |

| Synaptic Vesicle Proteins and Associated Synaptic Proteins | ||||

| Scg3 | secretogranin III | 585.8 | 111.5 | 5.2 |

| Scg2 | secretogranin II; secretoneurin | 202.8 | 33.8 | 6 |

| Synpr | synaptoporin | 184.9 | 14 | 13.1 |

| Mal2 | mal, T-cell differentiation protein 2 | 124.8 | 6.4 | 19.1 |

| Syt7 | synaptotagmin VII | 75.1 | 9.3 | 8 |

| Nptx2 | neuronal pentraxin 2 | 73.8 | 10.4 | 7 |

| Syt9 | synaptotagmin IX | 66.9 | 6.2 | 10.7 |

| Syt5 | synaptotagmin V | 66.5 | 3.8 | 17.3 |

| Nptxr | neuronal pentraxin receptor | 66.3 | 12.6 | 5.2 |

| Nrsn1 | neurensin 1 | 65.4 | 11.5 | 5.6 |

| C1ql4 | complement component 1, q subcomponent-like 4 | 31.8 | 1.4 | 21.9 |

| Syt16 | synaptotagmin XVI | 3.6 | 0.3 | 8.7 |

| Transcription Factors, mRNA-binding proteins and Transcription Related and Splicing Factors | ||||

| Prdm12 | PR domain zinc finger protein 12 | 136.4 | 21.8 | 6.2 |

| Nbl1 | neuroblastoma, suppression of tumorigenicity 1 | 132.9 | 22.6 | 5.9 |

| Tshz2 | teashirt zinc finger family member 2 | 115.8 | 19.3 | 6 |

| Ldb2 | LIM domain binding 2 | 103.5 | 5 | 20.4 |

| Carhsp1 | calcium regulated heat stable protein 1 | 66.7 | 7.9 | 8.3 |

| Fos | FBJ osteosarcoma oncogene; cFos | 59.6 | 1.7 | 34.1 |

| Junb | Jun-B oncogene | 55.8 | 9.8 | 5.6 |

| Celf6 | bruno-like 6, RNA binding protein (Drosophila) | 41.5 | 1.1 | 35.4 |

| Runx1 | runt related transcription factor 1 | 35.2 | 2.4 | 14 |

| Egr1 | early growth response 1; Krox-1; nerve growth factor-induced protein A | 30 | 4.3 | 6.9 |

| Klf5 | Kruppel-like factor 5; basic transcription element-binding protein 2 | 27.5 | 3 | 8.9 |

| Paqr5 | progestin and adipoQ receptor family member V | 27.4 | 1 | 24.9 |

| Bex1 | brain expressed gene 1 | 26.7 | 1 | 24.9 |

| Zfp36 | zinc finger protein 36 | 21.7 | 3.4 | 6.2 |

| Growth Factors, Matrix and Glycoproteins, Cell Adhesion, Semaphorins, and Cytokine Receptors and Modulators | ||||

| Cd24a | CD24a antigen; nectadrin | 924.2 | 83.6 | 11 |

| Fgf13 | fibroblast growth factor 13, microtubule regulation | 395.2 | 76.1 | 5.2 |

| Cd55 | CD55 antigen; complement decay-accelerating factor | 226.6 | 39.6 | 5.7 |

| sgigsf | cell adhesion molecule 1; Cadm1 | 158.4 | 22.4 | 7 |

| Gfra2 | glial cell line neurotrophic factor family receptor alpha 2; neurturin receptor | 115.7 | 11.5 | 9.9 |

| Ly86 | lymphocyte antigen 86 | 109.5 | 13.7 | 8 |

| Cd44 | CD44 antigen; hyaluronate receptor | 81.4 | 5.2 | 15.3 |

| Plxnc1 | plexin C1; semaphorin receptor | 77.6 | 10.3 | 7.4 |

| Gfra3 | glial cell line derived neurotrophic factor family receptor alpha 3 | 73.5 | 0.4 | 148.6 |

| Stac1 | src homology three (SH3) and cysteine rich domain | 47.2 | 6.2 | 7.5 |

| Ccdc68 | cutaneous T-cell lymphoma-associated antigen | 28 | 2.1 | 12.8 |

| Cgref1 | cell growth regulator with EF hand domain 1 | 24.9 | 4.7 | 5.2 |

| Osmr | oncostatin M receptor | 23.6 | 1.8 | 12.8 |

| Il31ra | interleukin 31 receptor A | 22 | 0.6 | 33.9 |

| Socs3 | suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 | 14.6 | 2.2 | 6.5 |

| Membrane, Structural and Rho/Rac Proteins | ||||

| Tmem233 | transmembrane protein 45b | 461.8 | 55.5 | 8.3 |

| Tmem45b | transmembrane protein 45B | 178.1 | 6.6 | 26.8 |

| Tubb2b | tubulin, beta 2a | 254.2 | 37.1 | 6.8 |

| Rasgrp1 | RAS guanyl releasing protein 1 | 90.5 | 2.5 | 34.8 |

| Ctxn3 | cortexin 3 | 81.3 | 4.2 | 18.8 |

| Ctxn1 | cortexin 1 | 62.8 | 8.8 | 7.1 |

| Rarres1 | retinoic acid receptor responder (tazarotene induced) 1 | 60.1 | 9.1 | 6.5 |

| Rasgrp | RAS guanyl releasing protein 1 | 51.1 | 1.5 | 31.8 |

| Cpne2 | copine II | 48.5 | 7.2 | 6.7 |

| Nrn1l | neuritin 1-like, Cpg15-2 | 46.2 | 6.7 | 6.8 |

| Tmem158 | transmembrane protein 158 | 45.7 | 2.1 | 20.8 |

| Rab27b | RAB27b, member RAS oncogene family | 22.6 | 4.4 | 5.1 |

| Arhgap26 | Rho GTPase activating protein 26 | 21.6 | 3.4 | 6.3 |

| Hspa1b | 70kDa heat shock protein 1B; chaperone protein | 16.8 | 3 | 5.4 |

| Ms4a3 | membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A, member 3 | 6.6 | 0.7 | 8.3 |

| Kinases, Phosphatases, Proteases, Mmps, Phosphodiesterases and Other Enzymes and Enzyme inhibitors | ||||

| Lxn | latexin; endogenous carboxypeptidase inhibitor | 328.5 | 66.3 | 5 |

| Prkcd | protein kinase C, delta | 224.8 | 24.4 | 9.2 |

| Acpp | acid phosphatase, prostate; PAP | 207.6 | 13.2 | 15.6 |

| Plcb3 | phospholipase C, beta 3 | 202.2 | 28.4 | 7.1 |

| Dusp26 | MAP kinase phosphatase 8 | 169.3 | 14.4 | 11.6 |

| Th | tyrosine 3-hydroxylase | 142.8 | 1.3 | 103.7 |

| Dgkh | diacylglycerol kinase, eta | 91.9 | 12.3 | 7.4 |

| Gpx3 | glutathione peroxidase 3 | 90.6 | 6.9 | 13 |

| Camk2a | calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II alpha | 79.7 | 9 | 8.8 |

| Ppp1r1a | protein phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 1A | 51.3 | 7.3 | 7 |

| Hs6st2 | heparan sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase 2 | 42.8 | 6.4 | 6.6 |

| Prkcq | protein kinase C, theta | 40.3 | 3.1 | 12.7 |

| Mmp25 | matrix metallopeptidase 25 | 35.7 | 4.1 | 8.5 |

| A3galt2 | alpha 1,3-galactosyltransferase 2 (isoglobotriaosylceramide synthase) | 33.5 | 2 | 15.7 |

| Dgki | diacylglycerol kinase, iota | 28.9 | 5.5 | 5.2 |

| Transporters, Trafficking and Interacting Proteins | ||||

| Fxyd2 | FXYD ion transport regulator 2; ATPase subunit gamma | 2196.7 | 252.1 | 8.7 |

| Aqp1 | aquaporin 1 | 152.6 | 21.9 | 6.9 |

| Atp2b4 | ATPase, Ca++ transporting, plasma membrane 4 | 18.5 | 2.1 | 8.4 |

| Slc4a11 | solute carrier family 4, sodium bicarbonate transporter-like, member 11 | 15.8 | 2.2 | 6.8 |

| Slc45a3 | solute carrier family 45, member 3 | 15.2 | 2.6 | 5.7 |

| Slc37a1 | solute carrier family 37 (glycerol-3-phosphate transporter), member 1 | 10.1 | 1.9 | 5.2 |

| Slc10a6 | solute carrier family 10 (sodium/bile acid cotransporter family), member 6 | 9.2 | 0.5 | 15.5 |

| Slc17a8 | sodium-dependent inorganic phosphate cotransporter, member 8 | 8.3 | 0.3 | 22.9 |

| Slc16a12 | monocarboxylic acid transporters, member 12 | 6.3 | 0.5 | 10.6 |

| Slc47a2 | solute carrier family 47, member 2 | 3.7 | 0.5 | 6.1 |

| Slc7a3 | solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 3 | 3 | 0.3 | 7.8 |

Genes in the TRPV1L preparation with a differential expression level of 5X and greater above values in the TRPV1D preparation were grouped into functional categories. Each category was sorted based on quantitative expression (high to low) from the deep RNA-Seq datasets. The table contains the top ~10–20 TRPV1L highest expressed genes within each category; this is only a sampling and the full listing is found in STable2. The adjusted fold change values are color coded: Red: >20 fold, Blue: 20-10 fold, and Green: < 10 Fold difference.

Calca, Calcb, and Nts, while not having a differential above 5X, are included because of their relevance to nociception.

Table 1 and Supplemental Table 2 provide the molecular signature of the TRPV1L transcriptome based on differential expression of 5-fold or greater. The transcripts are placed into nine functional categories (10–19 per category) listed from high to low based on quantitative transcript levels (RPKM). It is notable that our cutoff of ≥ 5-fold enrichment is arbitrary and many familiar genes associated with nociceptive processes are not on this list. This in no way minimizes or impugns their role in nociception, but simply reflects lower differential expression and/or performance of a function common to both TRPV1L and D DRG neurons. The theme of differential expression is continued in the remaining supplemental tables (STable3-STable7) which tabulate the remaining differentially expressed genes in TRPV1L and D populations and genes common to both. Together these transcriptome data greatly expand the nodes for connecting molecular processes with our understanding of nociception, its modulation and the differentiation of DRG neuronal functions. Obviously, many but by no means all, of the well expressed DRG genes have been the subjects of pain research and the fact that they are enriched is consistent with the methodological focus on nociceptive neurons.

Potassium Channels

A striking feature of the TRPV1L population is the high representation of differentially expressed potassium channels: out of the 30 ligand and voltage gated ion channels in the 5-fold or greater group, 12 (40%) are K+ channel subunits or modulatory proteins (Tables 1, S2 and S3). In the TRPV1L and D preparations, ~115 K+ channels and interacting proteins are identified and ~90 are expressed at ≥ 1 RPKM. Transcripts for two A-type channel modulatory proteins Kcnip (KChIP) 4 and 2 were the highest expressed (>100 RPKM) and both contain an EF hand calcium binding motif (Table 1). While these have not been studied in DRG, the proteins can affect K+ channel trafficking49 and knockout of Kcnip2 increased susceptibility to limbic seizures, suggesting that Kcnip2 may also influence DRG neuronal excitability.69 The TRPV1L neurons also differentially express both β1 and β2 subunits of the high conductance MaxiK (BK, Kcnmb) channel which is calcium regulated. The potential colocalization of multiple K+ channels and modulators suggests a system for membrane potential control that may be triggered by calcium entry subsequent to activation of TRPV1. Numerous efforts have been aimed at developing K+ “channel opener” compounds, mainly as antiepileptics,67 and some have been partially explored for analgesic activity.14,95 Implementation of the present transcriptome data may facilitate fine-tuning of K+ channel isoform targeting for analgesic therapeutic purposes.

Cholinergic Receptors

A second example of data mining related to analgesics is the acetylcholine receptors. The discovery of the analgesic actions of the nicotinic cholinergic agonist epibatidine emphasized a role for acetylcholine receptors at the ganglionic and/or spinal levels.3,96 Table 1 shows that the α6 subunit is highly expressed in the TRPV1L population (30.3 RPKM in TRPV1L vs 4.0 RPKM in TRPV1D), consistent with expression and colocalization studies.19,23 Despite these data, the α6 subunit appears to have been largely ignored in favor of experiments using the α7 subunit. Interestingly, the α7 subunit is also well expressed in DRG but in an inverse fashion: mainly in the TRPV1D population (5.3 RPKM for TRPV1L vs 30.8 for TRPV1D). Transcriptome analysis disclosed a strong expression of the nicotinic β2 subunit (common to both populations 16.3 and 20.2 RPKM for TRPV1L vs D) and a strong differential expression (5.3 vs. 0.1 RPKM) of the β3 subunit in the TRPV1L neurons. These quantitative considerations suggest that differential α6, β3 or β2 subunit expression may be key determinants for development of nociceptive neuron specific analgesic cholinergic agents.

RGS Proteins

An examination of the G-protein coupled receptors and associated proteins category in Table 1 and Supplemental Table 2 reveal an overrepresentation of Regulators of G Protein Signaling (RGS proteins, n=5) compared to the TRPV1D population (n=1) (Tables S4A and B). The RGS proteins are multifunctional modulators of GPCRs that generally increase the GTPase activity of active Gα subunits thereby reducing the amplitude and time course of GPCR signaling.85 The order of expression levels in TRPV1L neurons is RGS4>10≫3>8≫14 with RGS4 and RGS10 exhibiting very high expression (606 and 222.9 RPKM, respectively). Several studies have implicated RGS proteins in DRG nociceptive functions related to partial axotomy-induced neuropathy15,88 and regulation of opioid and metabotropic glutamate receptor function.16,94 Most opioid receptor-RGS interaction studies have focused on spinal and supraspinal sites and investigated either analgesia or addiction22 but no work has directly focused on the DRG. Knock-in of a RGS insensitive Gα was shown to increase morphine analgesia and the effect was partially attributed to enhanced opioid mediated disinhibitory actions in the periaqueductal gray. However, given the high concentrations of RGS proteins in the TRPV1L population, actions on the “input function” coming from DRG afferents need further consideration and targeting of the TRPV1L RGS isoforms may be a route to modulation of opioid receptor action44 in peripheral neurons.

Mrg Receptors

Four Mrg receptors are expressed ≥ 5 fold in the TRPV1L neurons. This is consistent with their roles in nociception and itch. MAS-related GPR, member D (Mrgprd) is the most highly expressed GPCR in the DRG (125.4 RPKM) and exhibits a 29-fold differential expression compared to TRPV1D. Mouse behavioral studies suggest that Mrgprd alone does not affect responsiveness to noxious thermal stimuli. However, dual ablation of DRG neurons expressing Mrgprd and TRPV1 produces a large decrease in sensitivity to noxious thermal stimuli and dual ablation of Mrgprd- and TRPM8-coexpressing neurons reduces responses to extreme cold.77 These data are consistent with the idea that Mrgprd neurons are polymodal nociceptors that are activated indirectly by the consequences of extreme temperature. In fact Mrgprd-cell deficient mice have profoundly reduced responses to ATP, as well as reduced sensitivity to mechanical stimuli, which is not surprising given the complement of ligand gated and mechanosensitive ion channels expressed by these neurons (Figure 2). 80 MAS-related GPR, member A3 (Mrgpra3) and MAS-related GPR, member X1 (Mrgprx1) receptors respond to various chemical puritogens and appear to be markers of itch sensory neurons.50,75 In mouse, Mrg genes are greatly expanded.106 We detected 16 Mrg receptors in murine DRG and 11 were differentially expressed in the TRPV1L population (between 1.3 to 125.4 RPKM). By comparison rat DRG only expresses the Mrgpra1, b4, d, e, r, h and x1 paralogs, the RPKM values are 9.3, 0.8, 21.3, 21.2, 4.6, 1.6, 14.4, respectively.

Taken together the above transcriptome analyses show that a detailed quantitative and cell-specific understanding of expression levels of paralogs and receptor subunits can have a profound effect on integrating molecular and neuronal functions and ultimately circuit operations for nociception and analgesia. This theme is further explored in Figures 2, 4A, and 4B, which illustrate the molecular “micro-circuit relationships” that can be extracted from the TRPV1L transcriptome.

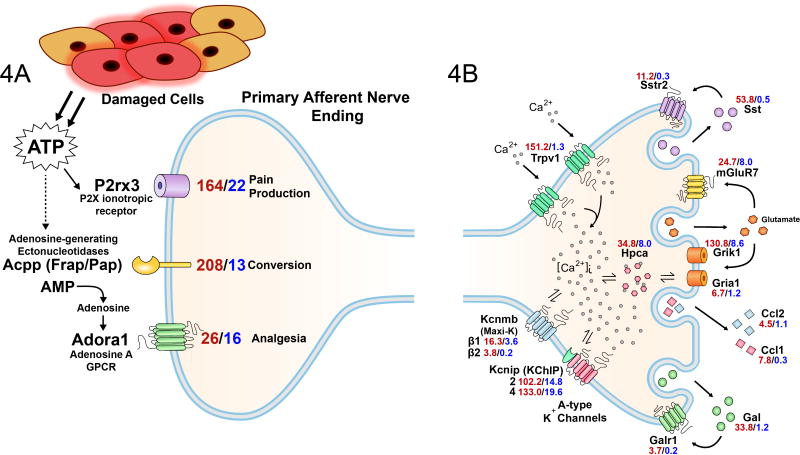

Figure 4. Integratory Molecular Circuits in TRPV1L Neurons.

Diagram showing how expression of linked signaling pathways and transmitter-receptor pairs can generate (A) paracrine and (B) potential autocrine signaling pathways to control the excitatory and inhibitory status of the peripheral nerve endings. (A) Purinergic nociceptive signaling can be modified by co-expressed ATP metabolizing ectonucleotidases and subsequent activation of adenosine A receptors to generate an analgesic component [P2rx3: P2X3, purinergic receptor, ligand-gated ion channel, 3; Acpp: prostatic acid phosphatase; Adora1: adenosine A1 G-protein coupled receptor]. (B) Depiction of several potential autocrine and calcium-dependent processes. Levels of expression receptors; all show higher expression (3- to15-fold) in the TRPV1L population and can support excitatory and inhibitory feedback by binding released glutamate. Neuropeptide receptor pairings for the Somatostatin receptor 2 (Sstr2) and somatostatin (Sst) and galanin receptor 1 (Galr1) and galanin (Gal) support a presynaptic autocrine inhibitory role. We identify several new calcium regulated process in the TRPV1L population based on differential expression of the hippocalcins and the potassium channel interacting proteins Kcnip2 and 4, all of which contain EF hand calcium binding motifs. The β1 and β2 MaxiK channel are also Ca++-regulated and can modulate nerve terminal hyperpolarization. Hippocalcin (Hpca) is known to play a regulatory role for AMPA receptor function (see text). The overall goals of the paracrine, autocrine and calcium binding proteins are hypothesized to mediate autonomous regulation of nerve terminal excitability and [Ca++]i under conditions of acute and chronic tissue damage or inflammation. [Gene symbols/names- mGluR7: Grm7, metabotropic glutamate receptor 7; Grik1: glutamate receptor, ionotropic, kainate 1; Gria1: glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA 1; Ccl2: MCP-1, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2; Ccl1: chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 1; Kcnmb: potassium large conductance calcium-activated channel, subfamily M, beta member]

TRPV1L Transcripts: Purines, Peptides, Cytokines and Paracrine-Autocrine Communication

General orientation

The following sections explore in more detail: (a) interpretation of the expression data in terms of neuronal heterogeneity even within the TRPV1 population (Figure 3), (b) some of the relationships devolving from Figure 2 and the tables (mainly Table 1) that integrate several signaling pathways into multifactorial presynaptic regulatory networks (Figure 4A, B), and (c) an example of co-localization of a calcium binding proteins (the hippocalcins) identified by RNA-Seq within TRPV1 neurons (Figure 5).

Figure 3. TRPV1 Expression in DRG.

Immunocytochemical staining for TRPV1 shows a gradient of expression in adult rat DRG neurons. The heterogeneity of TRPV1 expressing neurons ranges from small densely stained cell bodies, more lightly stained medium sized neurons and a range of very faintly stained neurons of various sizes. Many large unstained neurons are also visible. This can be seen in the panoramic view and appreciated better at the high magnification. This range of TRPV1 expression is subsumed in the TRPV1 lineage population thus the level of expression of genes other than TRPV1 can also vary. The large unstained neurons are contained in the TRPV1D preparation. Scale bar: 100μ

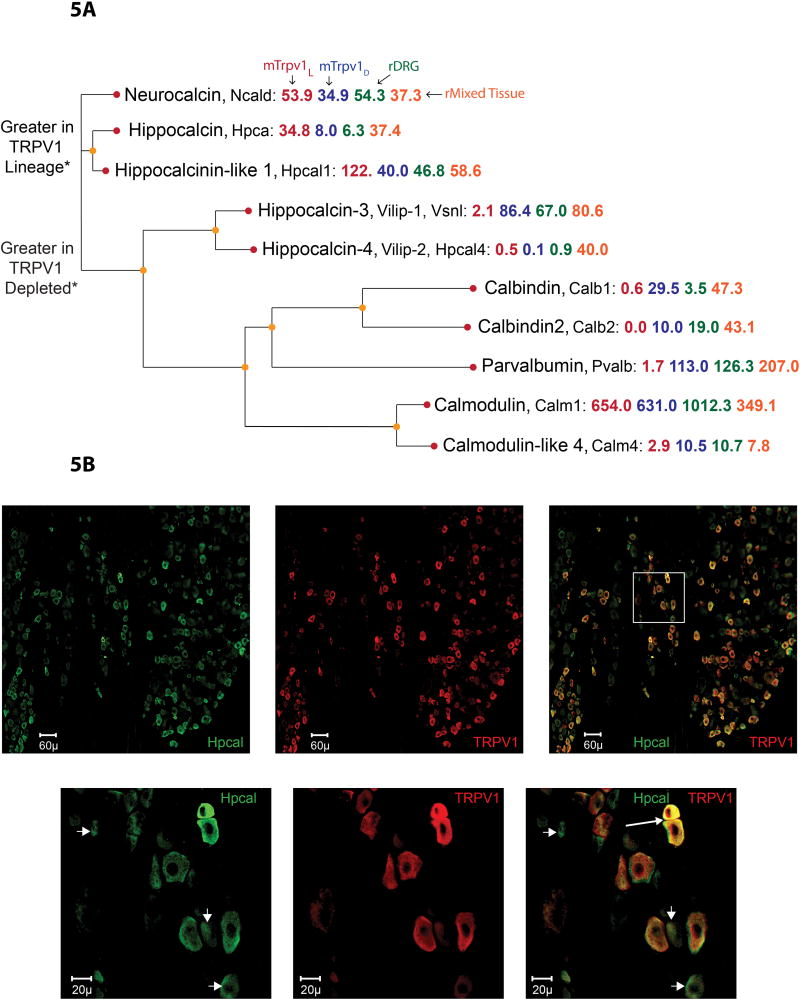

Figure 5. Hippocalcin in DRG.

(A) Molecular relationships, determined by protein sequence alignment in Clustal Omega, between the EF hand gene family members is depicted in this dendrogram. RNA-Seq data for TRPV1L, TRPV1D, whole rat DRG, and rat mixed tissue are given in red, blue, green and orange, respectively. Sequence alignment of hippocalcin and hippocalcin like 1 proteins reveals them to be nearly identical (not shown) and the carboxy-terminal directed antibody used for immunocytochemistry will detect both proteins. (B) Double label immunocytochemistry shows colocalization of hippocalcin (green) and TRPV1 (red). Panels on the right show merged images with many double labeled cells. In lower right panel the arrow points to two very strong coexpressing neurons and the arrowheads point to neurons that predominantly express only hippocalcin. The whole tissue sample was acquired by scanning at three emission wavelengths as a series of fields at 40X with excitation emission filters for DAPI, Alexa 488 and Alexa 594. Consistent with the transcriptional expression data showing major expression of hippocalcin in the TRPV1L neurons, but also detectable expression in the TRPV1D preparation, a range of dual and single labeled neurons are seen for either TRPV1, hippocalcin or both.

Figure 2 illustrates a primary afferent nerve ending and the cellular locations of proteins coding for families of ion channels, enzymes, GPCRs, growth factor receptors, intracellular and vesicular proteins, neuropeptides, and extracellular linking proteins. The corresponding transcript levels are placed next to the protein. Several gene families are portrayed in detail such that most members of a family are listed, even if the values do not reach the ≥ 1 RPKM cutoff (e.g., Trpm1, 5 and 6). Proteins are identified by the gene symbols from NCBI. Full protein names for many of the genes indicated are in the figure legend. It is important to note that the molecules depicted in Figure 2 are not necessarily expressed in a single nerve ending; rather the respective peripheral nerves collectively express these molecules. In addition, as depicted, Figure 4 shows various molecules in the same nerve ending. Such co-localization of a ligand and receptor, for example somatostatin and Somatostatin receptor 2 (Sst and Sstr2) in TRPV1L neurons, needs further verification by anatomical co-localization studies, although somatostatin is known to inhibit DRG neurons via Sstr2. It is also important to note that a paracrine relationship may apply if the ligand and its receptors are in adjacent nerve endings.

Heterogeneity within the TRPV1 population

Neuronal labeling through the developmental TRPV1 lineage allows us to more broadly sample neuronal populations related to nociceptive modalities. At this stage of exploration, we felt that the lineage strategy was more advantageous than to more narrowly focus on the TRPV1 population as it exists in the adult, which is also heterogeneous as shown in Figure 3. The heterogeneity in cell size and intensity of staining is evident in the immunohistochemical staining for TRPV1. Variation in Trpv1 staining intensity also can be seen in Figure 5b and in many publications that mainly use immunofluorescence64,83 and in part reflects expression in a subpopulation of Aδ neurons.64 Thus, the absolute level of expression for each gene needs to be interpreted in terms of a neuronal population within which variation in expression level can occur.

In terms of nociceptive modalities, our data, as well as results from others, dating back to the early 1970’s, support the hypothesis that the adult DRG is likely a mixture of polymodal nociceptors and more refined subpopulations of modality specific nociceptors and non-nociceptive neurons.5,11,18,41,64,72 Figure 3, in which multiple populations of TRPV1 expressing cells can be seen, emphasizes this fact. In addition, in a recent paper,64 we show that injection of resiniferatoxin in the periphery (hind paw) causes a profound loss to both noxious heat and to thermal stimuli that produce tissue damage. This observation, which is obtained at a high dose of RTX, is consistent with a range of TRPV1 expression within a range of nociceptive subtypes. Additional labeling and sorting techniques will be required to isolate and further define these specific subpopulations to obtain a deeper molecular-level understanding of neuronal populations in the DRG.

Purine, Pyrimidine and ASIC receptors and Conversion of ATP to Adenosine

The TRPV1L neuronal lineage shows strong expression of the acid-sensing (proton-gated) ion channel 2, Accn1 (Asic2), the Adenosine 2A and P2Y1 GPCRs, the P2X3 ATP-gated ion channel, and the ectonucleotidases FRAP (fluoride resistant acid phosphatase, Acpp, PAP) and Nt5e (5′ ectonucleotidase). The high expression of Accn1/Asic2 suggests that this paralog is a major acid sensing ion channel subtype responding to an acidic inflammatory environment in the TRPV1L population. Accn3/Drasic exhibits the inverse pattern, although expression overlaps substantially. When the ectonucleotidases are included, the quantitative relationships support the idea that a cascade of transmitter ATP production and enzymatic processing occurs upon tissue damage (Figure 4A). We hypothesize, that ATP released from damaged cells activates TRPV1L neurons through the P2X3 ionotropic receptor (the major P2X subtype on the TRPV1L population). At the same time, high concentrations of extracellular, locally tethered ectonucleotidases can convert ATP to adenosine, which can activate the adenosine A1 GPCR to reduce afferent excitability.107 In this paracrine fashion the nerve ending converts an algesic substance to an analgesic substance. It is known through in vitro and in vivo studies with RTX that calcium overload can produce a long-term inactivation of nociceptive endings.39, 63,68,72 While we use this inactivation property for therapeutic purposes (<http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00804154>), in situations of tissue damage, pain sensitivity and the functional integrity of the peripheral nerve ending must be preserved until the damaging stimuli are terminated or removed. RNA-Seq also identifies a new set of intracellular calcium binding molecules, the hippocalcins (Hpca, Hpcal1) that are 3–4 fold enriched in Trpv1L neurons and may reduce free internal calcium levels resulting from excessive or prolonged P2X3 or TRPV1 activation. Thus, multiple molecules and mechanisms may be engaged to maintain the physiological and structural integrity of nociceptive nerve endings in conditions of massive tissue damage or prolonged chronic pain (Figure 4A,B).

Synaptogranins and Cytokines

Subpopulation-enriched expression was also observed for synaptic vesicle proteins. The intra-vesicular proteins secretogranin-2 and -3 are highly and predominantly expressed in the TRPV1L population (Figure 2 center). Neuropeptides are concentrated in the TRPV1L neurons and are known to be stored in large dense core vesicles, which co-store the granins. While members of the granins are expressed in all neuroendocrine tissues, the 33 amino acid peptide secretoneurin, derived from secretogranin-2, has been reported to play a role in neuroimmune interactions mediated by DRG neurons.38 Although a distinct receptor had not been identified for this peptide, it has been shown to be cleaved from the precursor, stored in C-fiber dense core vesicles, released peripherally in certain pathological states, such as rheumatoid and osteoarthritis and has macrophage chemoattractant properties.86

Two other macrophage chemoattractant molecules are preferentially expressed in the TRPV1L population, CCL1 and CCL2 (monocyte chemoattractant peptide 1, MCP-1). Both have been investigated for neuroimmune interactions in several studies, especially MCP-1.37,102 The receptors for these cytokine molecules are not expressed in sensory ganglionic tissue. These data raise the possibility that vesicles of primary afferents store one or both cytokines and that nociceptive nerve endings play an active role in monocyte recruitment. Interestingly, leukocyte diapedesis appears to occur at both the peripheral and central ends of the primary afferents. In models of nerve injury, monocyte infiltration from peripheral blood has been demonstrated in the dorsal horn,20 and peripherally, monocytes make up a second wave of infiltrating leukocytes into inflamed tissue, the first wave being predominantly neutrophils. These data are consistent with the idea that the primary afferent ending can shape nociceptive responses to tissue injury and local regulation of specific leukocyte populations at primary afferent nerve termination zones. Both CCL1 and CCL2/MCP-1 contain signal peptides consistent with processing in the regulated secretory pathway and vesicular storage, however, the co-localization of CCL1, CCL2 and secretoneurin is illustrative, and whether they are in the same vesicle requires further studies (Figure 4B).

Neuropeptides

Transcripts coding for neuropeptides display more prominent expression in the TRPV1L population (Tables 1, S2, and S3). None of the classical neuropeptides are differentially expressed in the TRPV1D population (Table S4A). Again, it is important to point out that the word “differential” does not equate to absolute, and we include in Table 1 the Calca and Calcb transcripts encoding CGRPα and β which are highly expressed, but the expression overlaps into both TRPV1L and TRPV1D cellular populations. This is consistent with many co-localization studies which indicate a broad array of DRG neurons express CGRP. In contrast, many other neuropeptide transcripts (preprotachykinin (Tac1), pituitary adenylate cyclase activating peptide (Adcyap1), cocaine and amphetamine regulated peptide (Cartpt), somatostatin (Sst), Galanin (Gal), and natriuritic polypeptide B [Nppb]) are strongly differentially expressed in the TRPV1L population (avg. of 50-fold).

Potential Autocrine Communication by Neuropeptides

Examination of the RNA-Seq data for neuropeptide-receptor pairs suggested the potential for autocrine or paracrine communication. Cases where both ligand and receptor are made by the same set of neurons include somatostatin (Sst) and galanin (Gal) (Figure 4B). In the mouse, strong differential expression of transcripts coding for Sst (97-fold) and Gal (25-fold) is seen in the TRPV1L population, which also primarily expresses somatostatin receptor 2 (Sstr2) and galanin receptor 1 (Galr1). Sst inhibits primary afferent nociceptive functions and gene knockouts identify Sstr2 as the receptor mediating analgesic actions.35 Similarly, galanin has been shown to inhibit the efferent local effector functions activated by RTX or capsaicin-sensitive peripheral nerve terminals in a fashion consistent with a presynaptic site of action.24 These data support an inhibitory presynaptic autocrine function for both Sst/Sstr2 and Gal/Galr1 peptide-receptor pairs and we speculate, as with the purinergic paracrine circuit, an autocrine mechanism that functions to regulate excitability of afferent endings in situations of prolonged tissue damage and chronic pain. Pharmacologically this can be manifested as analgesia, but in pathophysiological conditions we hypothesize that the inhibitory functions participate in preserving the physiological and anatomical integrity of the primary afferent ending.

Potential Autocrine Communication by Glutamate

The excitatory amino acid glutamate may also participate in autocrine/paracrine communication via the kainate and AMPA subtypes of glutamatergic receptors. Expression of the kainate subtype (Grik1, 130.8 RPKM) far exceeds that of the AMPA receptor Gria1, 6.7 RPKM). Ionotropic glutamate receptors are generally heteromeric and the other subunits are also expressed to varying degrees (Tables S3, S4 and S5). Expression of kainate and AMPA receptors may represent an excitatory presynaptic “opponent process” to the above analgesic neuropeptide scenarios (Figure 4B) and kainic acid is known to excite peripheral nerve endings.105 Metabotropic glutamate receptors are also expressed, the highest levels were for mGluR7 (Grm7: TRPV1L 24.7 and TRPV1D 8.0 RPKM), the expression levels for the other isoforms were below 1.5 RPKM in the TRPV1L neurons; several other mGLuRs are made in the TRPV1D population (Tables S4A, B). These quantitative measures suggest that mGluR7 is the main metabotropic glutamate receptor paralog performing a presynaptic function in murine nociceptive neurons. As such, mGluR7 also fits the “transmitter-receptor pairing” criterion to form an autocrine molecular circuit. In this case an analgesic function may be engaged since local injection of a mGluR7 allosteric agonist attenuated carrageenan-induced and post-surgical hyperalgesia.17

Other receptor families

Table 1 and Table S2 contain the GPCRs Lpar3 and 5 that bind lysophaphatidic acid, an algesic mediatior and a target for therapeutic anti-lysophaphatidic acid antibodies.25 Two receptors for neuropeptide Y, Npy1r and 2r are expressed in TRPV1L neurons, however, while NPY is not well expressed in basal state ganglion, it is strongly induced following axotomy.45,98 Thus, it is possible that newly synthesized NPY and the two preexisting NPY receptors could form an autocrine loop following nerve injury. Growth factor receptors are also highly differentially expressed with the strongest TRPV1L transcripts being glial cell line derived growth factors 3 and 1 (Gfra3, Gfra1, Figure 2). Genes for most of the tyrosine kinase growth factor receptor ligands (GDNF, artemin, neurturin, persephin, neurotrophin 3, and NGF) are not expressed in DRG. Exceptions are BDNF (9.7/5.2), CNTF (4.4/46.7), and C-kit ligand (5.8/21.3); values are RPKM in TRPV1L/TRPV1D populations. Roles for NGF and BDNF have been reviewed.58,70 For c-kit both the ligand and receptor are expressed in the TRPV1L and D populations and developmentally are involved in early DRG differentiation and neurite growth cone extension.30 In the adult, intrathecal injection of c-kit ligand is reported to produce sensitization in a variety of pain tests.90,92 Additionally, the inhibition of c-kit with monoclonal antibodies has been reported to reduce heat and cold pain sensitivity in humans.12

RTX Lesion of Rat Trigeminal TRPV1 Neurons

Stereotaxic microinjection of RTX into rat trigeminal ganglion to remove TRPV1-expressing neurons at 10 days provided a validation of the mouse TRPV1 manipulation and allowed the mouse dataset to be extended to the rat. We analyzed gene expression in the cell remaining in the ganglion after RTX treatment. The trigeminal ganglion and the dorsal root ganglion share a very similar overall gene expression pattern.21 We examined the similarity between TG and lumbar DRG using the quantitative rat data for genes in Figure 2 as a test transcript set. The resultant DRG:TG correlation coefficient was significant with a R2 value of 0.88 (Figure S4, panel A). From our more global analysis of ganglionic transcriptomes, one difference we noted was that, out of 18 Hox genes present in the lumbar DRG, Hoxd1 is the only Hox gene also expressed in the trigeminal ganglion (Figure S4, panel B).

Table S6 contains the comparison of the rat RTX data with the TRPV1L 5X and above differentially expressed genes (Tables 1 and S2). 85% of the TRPV1L genes expressed at or above 3 RPKM in the functional groups of “Ligand and Voltage Gated Ion Channels,” “Transporters and Channel Interacting Proteins,” and “GPCRs and Associated Proteins” were significantly down regulated after intraganglionic injection of RTX. Unlike the genetic expression of diphtheria toxin, the microinjection generally leaves some low expressing TRPV1 neurons intact, which can attenuate the degree of decrease (Karai et al., 2004).39 The RTX dataset also indicates the polymodal nature of some neurons in the TRPV1L population: loss of TRPV1-expressing neurons was accompanied by significant decreases in TRPM8 (cold), Trpa1 (chemo-nociception), TRPC3 (light touch), Mrgprd (pinch and high threshold stimuli), and Mrgprx1 (itch and nociception).79 The overlap between the mouse genetic labeling/ablation and rat RTX chemoablation suggest a core “nociceptome” that is key to understanding the first steps in pain processing. These genes, in turn, are embedded in a supporting transcriptional network that can also be exploited for further understanding of nociception.

Species Differences

Tyrosine Hydroxylase

We made a comparison between rat and mouse DRGs. The vast majority of transcripts showed similar levels of expression. One conspicuous species differences occurred for TH, the first enzyme in the catecholamine biosynthetic pathway. TH is highly expressed in mouse DRG TRPV1L neurons (143 RPKM) compared to whole rat DRG (0.7 RPKM). In rat, TH immunostaining shows infrequent, sporadic staining of DRG neurons,78 which matches the low transcript abundance. The comprehensive nature of RNA-Seq indicates that the catecholamine synthetic pathway apparently ends with TH in both mouse and rat. Transcripts coding for aromatic amino acid decarboxylase, dopamine β-hydroxylase, and vesicular dopamine or norepinephrine uptake were either not detectable or were below 1.0 RPKM, consistent with the earlier neuroanatomical studies.9 Thus, it is tempting to speculate that L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA), the end product of TH, has a unique role in mouse C-fiber low-threshold mechano-sensory neurons. However, deep sequencing showed that Moxd1, a dopamine β-hydroxylase paralog,13 is well expressed (19.1 RPKM) in the TRPV1L neurons suggesting that β-hydroxyL-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine may also be an enzymatic end product and potential transmitter.

Neuropeptides

Several neuropeptides also exhibit strong differential species expression, notably the cocaine and amphetamine regulated transcript (CART, Cartpt), galanin (Gal), natriuretic peptide precursor b (Nppb), and neurotensin (Nts). CART, Gal, Nppb and Nts and are mainly expressed in the TRPV1L population (RPKM: CART 64.7 vs 2.1; Gal 33.8 vs 1.2; Nppb 24.1 vs 0.2; Nts 10.7 vs 2.3; enriched vs depleted, respectively, see Table 2 and Figure 2), but in whole rat ganglion these peptides are expressed at much lower levels (CART 1.1, Gal 3.2, Nppb 0.7, and Nts 0.6 RPKM). Nonetheless, such low levels can translate into a measureable signal in immunocytochemical studies. In rat, CART-positive neurons only account for ~1.26% of > 25,000 trigeminal ganglion neurons,36 and, based on additional colocalization markers, some may be TRPV1-expressing Aδ neurons.63 Most of the other familiar neuropeptides (Calcitonin gene related peptides (Calca, Calcb), preprotachkinin precursor (substance P, Tac1), somatostatin (Sst) and pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide 1 (Adcyap1, PACAP) are well expressed in both mouse and rat DRG.

Hippocalcin Expression and New Transcript Annotations Resulting from Deep Sequencing

Immunocytochemical Localization of Hippocalcin (Hpca) in Rat DRG

The calcium binding proteins calbindin D28, parvalbumin and calretinin have been used to label subpopulations of DRG neurons.32,84 Up till now the presence of the hippocalcins in DRG has not been appreciated. RNA-Seq transcriptome data indicate that hippocalcin (Hpca) and hippocalcin-like protein 1 (Hpcal1) are highly expressed in the TRPV1L population. Amino acid sequence comparisons show that the two hippocalcins are very similar and diverge from the parvalbumins and calbindins (Figure 5A). Immunofluorescent staining of DRG reveals that Hpca immunoreactive neurons are in the small to medium size range consistent with the nociceptive class of DRG neurons. Immunofluorescent double labeling shows colocalization of TRPV1 with hippocalcin, consistent with predominant expression in TRPV1L neurons (Figure 5B). The hippocalcin calcium binding proteins provide new markers for the TRPV1 population of DRG neurons and may play key roles in regulating nerve terminal free calcium in conditions of acute and chronic pain. This potential role is illustrated as part of Figure 4B.

5′ and 3′ Untranslated Regions (5′ and 3′-UTRs) and MicroRNA Binding Sites in the TRPV1 Gene

Earlier studies on RNA-Seq have been used for genomic re-annotations and studying alternate splicing events.28 Deep transcriptome sequencing can also be used to provide a more complete assessment of 5′ and 3′ UTRs and the information content therein. In the present report, using TRPV1 as an example, we analyzed the Refseq entries of mouse, rat and human. Deep sequencing showed that the 5′ and 3′ mouse UTRs are extended approximately 130 and 735 bases, respectively (Figure 6 and S3). The 5′ sequence reported herein extends beyond the Refseq entries for mouse, rat, and human and suggests the start site for transcription is upstream from the current database annotation. This is significant because the genetic control elements for transcription are at the 5′ end and accurately determining the start site allows more precise mapping of transcriptional control elements and a better understanding of molecular transcription mechanisms for TRPV1 expression or any other genes that need reannotation. The 3′ extension brings the mouse sequence into register with the human and rat annotations and provides a new consensus 3′-UTR. (Note: the above predicted 5′ and 3′ UTR extensions have been recently incorporated into the TRPV1 Refseq gene model and now correspond fairly well to extensions seen in our RNA-Seq data). It has recently been observed that 3′-UTRs frequently contain binding sites for regulatory microRNAs.4 We identified 3 consensus sites that were conserved between mouse, rat and human for the microRNAs miR-940, miR-684, miR-375 (Figure 6). The conservation of the miRNA binding sequences between species implies potential direct roles for miRNAs in TRPV1 regulation in DRG neurons. However, none of the early studies of miRNA in DRG after peripheral inflammation or nerve injury examined the above three miRNAs.7,43,48 This suggests more comprehensive bioinformatic and experimental approaches to the analysis of miRNAs in DRG are necessary to guide experimentation and to delineate the roles of miRNAs in pain models.

DISCUSSION

The present sets of experiments were conducted to probe the pain transcriptome in primary afferent neurons. Our understanding of nociceptive molecular biology is rudimentary at best and has not yet been dissected with a strategy that combines genetic labeling with comprehensive transcriptome sequencing. Using such an approach we have elucidated the complete transcriptome of an important and clinically relevant population of nociceptors: those that express TRPV1. We make the assertion of clinical relevance based on our previous and current work in animals and humans using the TRPV1 neuronal/nerve terminal deletion reagent resiniferatoxin, which is presently being evaluated as a pain treatment in patients with advanced cancer and has been shown to be effective to treat pain in canine osteosarcoma.29,31,54

Molecular Elements for Integrative Communication

We examine many aspects of nociceptive processes and pharmacology within the TRPV1L population. One of the more important observations to emerge from this research is the identification of several new potential autocrine and paracrine molecular communication and control pathways as illustrated in Figure 4. The presence of multiple molecular microcircuits in dorsal root ganglion highlights the crucial role for autonomous, presynaptic regulatory mechanisms. The representation of both inhibitory and excitatory autocrine/paracrine loops suggests, at least at the peripheral terminals, that the nociceptive sensory ending has elaborated a diverse set of control mechanism for maintaining sensitivity in chronic pain states. It is known that excessive excitation can produce calcium cytotoxicity and “deactivate” the nerve ending. Such a deactivation would make the nerve terminal insensitive to the local nociceptive environment thereby losing the protective function of pain. Thus, maintaining excitability in persistent pain states is a critical requirement of nociceptive nerve endings and both peptidergic and metabotropic glutamate receptors as well as ectonucleotidases are hypothesized to reduce excitation. Interestingly excitatory glutamatergic kainite and AMPA receptors are present apparently to maintain a balance. In addition, these processes are bolstered by multiple intracellular calcium regulatory mechanisms involving calcium binding proteins, such as the hippocalcins and calcium regulated potassium channel interacting proteins. These data quantitatively identify a rich repertoire for combinatorial approaches to pain control.