Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Hair transplant is among the most common cosmetic services sought by men, with more than 11 000 procedures performed in 2014. Despite its growing popularity, the effect of hair transplant on societal perceptions of youth, attractiveness, or facets of workplace and social success is unknown.

OBJECTIVES

To determine whether hair transplant improves observer ratings of age, attractiveness, successfulness, and approachability in men treated for androgenetic alopecia and to quantify the effect of hair transplant on each of these domains.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

A randomized controlled experiment was conducted from November 10 to December 6,2015, using web-based surveys featuring photographs of men before and after hair transplant. One hundred twenty-two participants recruited through various social media platforms successfully completed the survey. Observers were shown 2 side-by-side images of each man and asked to compare the image on the left with the one on the right. Of 13 pairs of images displayed, 7 men had undergone a hair transplant procedure and 6 had served as controls. Observers evaluated each photograph using various metrics, including age, attractiveness, successfulness, and approachability. A multivariate analysis of variance was performed to understand the effect of hair transplant on observer perceptions. Planned posthypothesis testing was used to identify which variables changed significantly as a result of the transplant.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

Observer ratings of age (in number of years younger) and attractiveness, successfulness, and approachability (on a scale of 0 to 100; scores higher than 50 indicate a positive change).

RESULTS

Of the 122 participants in the survey, 58 were men (47.5%); mean (range) age was 27.1 (18–52) years. The initial multivariate analysis of variance revealed a statistically significant multivariate effect for transplant (Wilks λ = 0.9646; P < .001). Planned posthypothesis analyses were performed to examine individual differences across the 4 domains. Findings determined with t tests showed a significant positive effect of hair transplant on observers’ perceptions of age (mean [SD] number of years younger, 3.6 [2.9] years; P < .001), attractiveness (mean [SD] score, 58.5 [17.5]; P < .001), successfulness (mean [SD] score, 57.1 [17.1]; P = .008), and approachability (mean [SD] score, 59.2 [18.1]; P = .02).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Men were perceived as being younger and more attractive by casual observers after undergoing hair transplant. Participants also rated posttransplant faces as appearing more successful and approachable relative to their pretransplant counterparts. These aspects have been shown to play a substantial role in both workplace and social success, and these data demonstrate that hair transplant can improve ratings universally across all 4 domains.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE

NA.

Androgenetic alopecia (AGA) is a common condition that leads to varying degrees of hair loss in both men and women. It has been estimated1 that rates of AGA in men older than 40 years approach 50%. Hair loss in affected individuals is progressive and assumes 1 of 7 characteristic patterns as classified by the Norwood-Hamilton scale.2,3 There exists a pathophysiologic association between this type of hair loss and androgen exposure,4 a link that has been integral in the development of medical treatment for AGA.5

Despite the fact that AGA is a prevalent condition evaluated in the dermatologic community, it has not garnered the attention that might be expected for such a common condition. This is likely a result of AGA often being regarded as a mild dermatologic condition or cosmetic disorder.6,7 Androgenetic alopecia may appear to be of little medical consequence since it is not typically associated with significant medical morbidity or mortality,8 and there is not a significant disruption of normal physiologic functioning. However, this characterization fails to acknowledge the profound psychosocial implications of hair loss on self-esteem and identity.

There is a growing body of literature aimed at elucidating the effect of hair loss on quality of life. Studies9 demonstrate that individuals experiencing hair loss have reduced self-esteem and self-confidence as well as higher self-consciousness, all of which may place them at a social disadvantage. This supposition is reinforced by literature10,11 reporting that men who are balding are rated poorly compared with men who are not balding in domains such as physical attractiveness, likeability, and overall life (career and personal) success. These realities provide strong motivation for individuals affected by AGA to seek treatment for this condition.

The mainstay of treatment for AGA can be divided into 2 categories: medical and surgical. Both minoxidil and finasteride have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in AGA.5,12 Although the mechanism of action of minoxidil is not completely understood, it has been shown5 to slow the rate of hair loss and, to a much lesser extent, increase hair growth and survival. The use of finasteride, a 5-a reductase inhibitor, is based on the association between AGA and androgen exposure. Finasteride prevents the conversion of testosterone to dihydroxytestosterone via enzyme inhibition, and the congenital absence of this enzyme is associated with a population-wide absence of AGA.13 Clinical trials confirmed the efficacy of finasteride; men had significantly less hair loss.14,15

For many, medical treatment alone does not provide desired results and surgical treatment of AGA has gained popularity over the past several decades.12 Hair restoration surgery in mainstream medicine dates back to the 1950s, and the seminal article describing this technique details the use of 4-mm punch grafts.16 Today the most widely used technique is micrografting by the traditional strip method or the follicular unit extraction method.17,18 This outpatient procedure requires a great deal of technical skill and endurance on the part of the surgeon since it can take multiple hours to dissect the follicles. However, patients perceive micrografting positively owing to the favorable risk-benefit ratio.18 These factors have undoubtedly contributed to the growing popularity of hair transplant in recent years.

In 2014, hair transplant was among the most common cosmetic services sought by men, with more than 11 000 procedures performed.19 Despite its growing popularity, few studies have explored the effect of hair transplant on societal perceptions. Through this study, we aimed to determine whether hair transplant improves observer ratings of age, attractiveness, successfulness, and approachability in men treated for AGA. In addition, we sought to quantify the effect of hair transplant on each domain.

Methods

Participants

One hundred twenty-two participants (63 women and 58 men; 1 declined to specify sex) completed the study from November 10, 2015, to December 6, 2015. Ages of study participants ranged from 18 to 52 years. Survey takers were excluded from the study if they were younger than 18 years or had psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia or an autism spectrum disorder, owing to differences in how these individuals direct attention toward a face as well as how they convey and infer emotional states from a face.20 Participants were naive to the specific purpose of the study. Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study from Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Boards. The first page of the survey described the task and relevant exclusion criteria. Respondents were notified that continuing on to the survey would serve as informed consent for their participation. Survey takers were also informed that they would be eligible to enter a drawing for a $20 Amazon gift card upon successful completion of the survey by entering their email address.

Instrument

Images of men who had undergone hair transplant were selected from a database containing photographs of patients who have been treated within the Division of Facial Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the Facial Plastic Surgery Center. Both pretransplant and posttransplant photographs were obtained. Control faces (men who had not undergone transplant) were selected from a separate research photograph database of patients to ensure that these individuals had not undergone significant cosmetic procedures between the 2 photographs. Controls were demographically matched according to age and sex to the surgical patients.

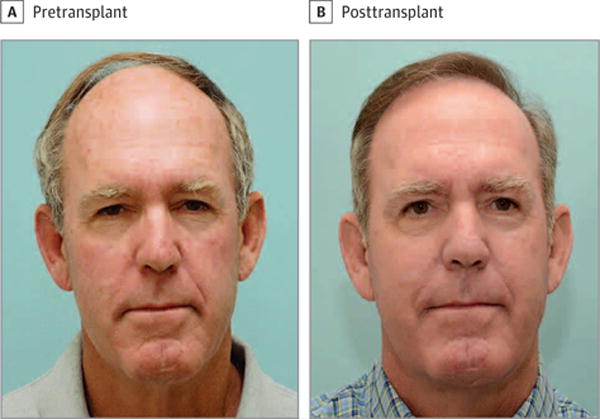

Six of the selected men did not have a hair restoration procedure in the time between their 2 photographs and were considered controls. Seven of the selected men had undergone a hair transplant procedure, each of whom had a pretransplant and a posttransplant photograph displayed. Observers were shown 2 side-by-side images of each man and asked to rate age, attractiveness, successfulness, and approachability by comparing the image on the left with the one on the right (Figure 1). Each survey contained all 13 pairs of photographs. The order in which the pairs of photographs were presented was randomized for each survey taker.

Figure 1. Representative Depiction of Survey Image Presentation.

Observers were asked to compare the image on the left (A) with the image on the right (B).

Surveys were built using Qualtrics Survey Software (Qualtrics). A link was disseminated via various social media platforms. Survey questions were designed to assess observer perceptions when comparing 2 images of each man. Participants were asked to evaluate how much younger the individual in the photograph on the right appeared relative to the photograph on the left. They were provided with a 10-point scale, as well as the option to select 0 if they did not believe that the person on the right appeared younger. Observers were also asked to rank the perceived attractiveness, successfulness, and approachability of the image on the right compared with the image on the left. For these measures, survey takers were provided with a 100-point slider bar. The bar began at 50, which corresponded to no difference. Moving the bar to the right corresponded to a positive change in these measures, while moving the bar to the left corresponded to a more negative rating. The order of the photographs was standardized: in the hair transplant group, the photograph on the left was always the pretransplant image and the photograph on the right was the posttransplant image.

Statistical Analysis

We performed our statistical analysis using Stata, version 13 SE (StataCorp). Observer ratings across each of 4 domains (age, attractiveness, successfulness, and approachability) were collected and studied. Our primary goal was to determine whether a statistically significant difference in observer ratings existed between the control and transplant groups. Following this determination, we aimed to identify the domains in which statistically significant changes existed. We conducted a 1-way multivariate analysis of variance with 4 dependent variables (age, attractiveness, successfulness, and approachability) using 1 factor (transplant) with 2 levels (control and transplant). This test allowed us to determine whether the hair transplant affected any of the domains of interest. Planned posthypothesis testing (unpaired, 2-tailed t test) was used to determine which of the variables changed significantly as a result of the transplant.

Next, we estimated the effect size for the domains of interest using a standardized mean difference and ordinal rank change approach. Variance component analysis of the data allowed us to separate variances due to participant biases from the regression residuals, and thus obtain more precise estimates of the true variances of the population’s attractiveness, successfulness, and approachability distributions. These variances were used to normalize the measured differences and calculate a standardized mean difference (Cohen d corrected for observer bias). Two standardized mean differences are presented: (1) differences measured in men who underwent hair transplant from the test baseline, and (2) differences between the no-transplant and transplant groups. Estimated ordinal rank change was obtained as follows: 100 random individuals were rank ordered from lowest to highest in a domain of interest, a hair transplant was performed on the 50th individual (ie, one of average attractiveness in a group of 100 men), and the group was then re-ordered. The estimated ordinal rank change represents the change in ranking of the individual who had a hair transplant. Using the attractiveness domain as an example, after the person ranked 50th receives a hair transplant, he should be ranked between 59 and 69 (higher number corresponding to a more favorable position). Mean differences are presented for test baseline to measured effect (baseline) and measured effect to nontransplanted controls (bias corrected). To estimate the ordinal rank change we integrated and scaled the appropriate normal distributions in Mathematica, version 10.3 (Mathematica), which provided an approximation for how much a hair transplant will shift the ordinal rankings of average individuals, as defined above, within the domains of interest.

Results

One hundred twenty-two participants successfully completed the survey. They were heterogeneous with respect to age, sex, and educational level (Table 1). Participants also reported self-rated attractiveness on a scale of 0 to 100, with 0 being least attractive and 100 being most attractive.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Observers

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (range), y | 27.1 (18–52) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 63 (51.6) |

| Male | 58 (47.5) |

| Other/prefer not to specify | 1 (0.8) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 8 (6.6) |

| African American | 3 (2.5) |

| Hispanic | 7 (5.7) |

| White | 102 (83.6) |

| Other/prefer not to specify | 2 (1.6) |

| Educational level | |

| Less than high school | 1 (0.8) |

| High school or GED | 10 (8.2) |

| Some college | 27 (22.1) |

| 2-y College degree | 6 (4.9) |

| 4-y College degree | 51 (41.8) |

| Master’s degree | 21 (17.2) |

| Doctoral degree | 6 (4.9) |

| Self-rated attractiveness, mean (SD)a | 65 (17) |

| Most important facial feature | |

| Eyes | 72 (59.0) |

| Mouth | 22 (18.0) |

| Hair | 22 (18.0) |

| Nose | 6 (4.9) |

| Ears | 0 |

Abbreviation: GED, general educational development.

Self-rated attractiveness was reported on a scale of 0 to 100 (0, least attractive; 100, most attractive).

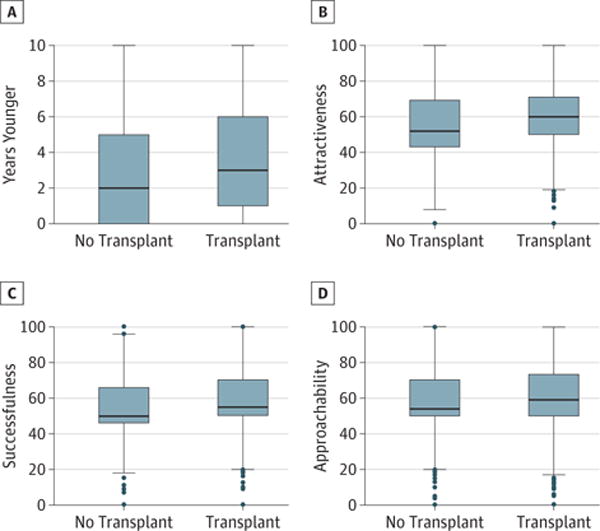

The raw data were gathered and studied to glean initial impressions of survey responses. Observer gradings of age, attractiveness, successfulness, and approachability are plotted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Differences in Observer Ratings Across the 4 Domains.

Ratings shown for years younger (A), attractiveness (B), successfulness (C), and approachability (D). Boxes contain values within the 25th–75th percentile. The solid line within the box represents the median value; whisker lines, range of values falling below the 25th percentile and above the 75th percentile; bullets, outliers of the data set.

These results demonstrated changes in observer gradings between the transplant and nontransplant groups. The initial MANOVA revealed a statistically significant multivariate effect for transplant (Wilks λ = 0.9646 [P < .001]; Pillai trace,21 0.0354 [P < .001]; Lawley-Hotelling trace,22,23 0.0367 [P < .001]; Roy largest root,24,25 0.0367 [P < .001]). Planned posthypothesis t tests were performed to determine which of the variables changed significantly as a result of the transplant. Each dependent variable was tested separately, and the results are summarized in Table 2. The data demonstrate that men who undergo hair transplant are graded as younger and more attractive, successful, and approachable than their pretransplant counterparts.

Table 2.

Differences Across the Domainsa

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | t Test | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Transplant | Transplant | |||

| Years younger | 2.6 (2.8) | 3.6 (2.9) | −7.29 | <.001 |

| Attractiveness, scoreb | 54.8 (18.5) | 58.5 (17.5) | −4.08 | <.001 |

| Successfulness, scoreb | 55.0 (17.5) | 57.1 (17.1) | −2.39 | .008 |

| Approachability, scoreb | 57.3 (18.2) | 59.2 (18.1) | −2.09 | .02 |

Degree of freedom was1584in all measures.

Rated on a scale of 1 to 100; scores higher than 50 indicate a positive change.

Effect sizes of hair transplant on attractiveness, successfulness, and approachability are listed in Table 3. Individuals who underwent transplant were found to be a mean of 3.6 (95% CI, 3.4–3.8) years younger after a hair transplant and 1.1 (95% CI, 0.8–1.3) years younger than the control group.

Table 3.

Change in Domain Rankings Following Transplant

| Characteristic | Baseline | Bias Corrected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMD | Ordinal Rank Change | SMD | Ordinal Rank Change | |

| Attractiveness | 0.51 | 19 | 0.22 | 9 |

| Successfulness | 0.46 | 18 | 0.13 | 5 |

| Approachability | 0.44 | 21 | 0.11 | 5 |

Abbreviation: SMD, standardized mean difference.

Discussion

The rationale for the study design was based on the wisdom of the crowd theory, which suggests that the judgments of a collective group will be more accurate than the individual contributions of its members. Sir Francis Galton26 popularized this theory in the early 1900s when he asked a large group of individuals to guess the weight of an ox. Although the individual guesses were wide ranging, the group’s collective average was close to the correct weight. Use of this theory remains pervasive in modern society, contributing to estimations of, for example, the stock market and political elections.27,28 Similarly, we relied on this theory when conducting our survey to understand societal perceptions. Despite a large range in individual ratings among participants, we trust that the mean grading of each transplant recipient will accurately represent the ratings attributed to these faces by society as a whole.

The data presented in this study indicate what we believe to be novel findings regarding hair restoration surgery. Analyses revealed statistically significant effects of hair transplant on observer gradings of youth. Men were reported to look younger after hair transplant. Men who underwent this procedure were also perceived as being more attractive, successful, and approachable than their pretransplant counterparts by casual observers. The improvement across these domains is significant, and the results from the integration of the standardized mean differences allow us to present data in a way we believe will be meaningful to both patients and physicians. By converting these values to number of people per 100, we have been able to provide a measure of how much an average person will improve in a given domain’s rankings after undergoing a hair transplant. For example, if 100 people were randomly sampled and then ranked and ordered according to their attractiveness, the effect of hair transplant for an average patient would result in moving from position 50 to 69, with higher values corresponding to a more positive rating. For successfulness and approachability rankings, men would move from position 50 to positions 68 and 71 after transplant, respectively.

Previous studies9,10,29 have described the psychosocial consequences of hair loss. Many of these consequences were related to self-perceptions and included diminished self-esteem and a lost sense of identity. The present study did not focus on self-image or ratings, but enhancing our understanding of the patients’ perceptions following this procedure would further augment this body of literature. Our study did, however, delve into the societal perceptions of men before and after surgery.

It has been shown10,11 that men who have lost hair are considered less attractive, less likeable, and less successful. Our results validate these findings in that men who had not undergone transplant are judged less favorably across these domains than are those who receive a transplant. In addition to validating the literature that suggests hair loss in men is associated with a social penalty, these data provide essential information about the efficacy of hair transplant in improving observer perceptions. The results of the present study may suggest that the hair transplant procedure can ameliorate some of the societal consequences of hair loss in men with AGA.

Although the results of this study proved statistically sound, as a pilot effort, we recognize the limitations of the small population and survey design. First, the survey comprised only 13 sets of photographs. Although sufficient for this type of preliminary study, follow-up studies will aim to expand and diversify the images shown within the survey to make the data more generalizable. The images used in the survey were selected from a photograph database and lacked standardization. In addition, studies have shown30 that lighting can alter facial perception. A more uniform selection of photographs with regard to lighting and background would be needed to avoid biasing observer ratings. We also elected to show photographs with the individuals in repose. It has been shown31 that smiling has a significant effect on observer perception of personality traits. Therefore, this neutral facial expression may have negatively affected ratings of attractiveness, successfulness, and approachability. Additional studies will be required to examine the differences in ratings when individuals are in smile and repose expressions to understand the effect of facial expression on observer perceptions.

There was also bias introduced by the survey design. For each set of photographs, the observer was asked to compare the image on the right with the image on the left. These instructions primed viewers to expect a difference between the 2 photographs in favor of the one on the right, but we pursued this study design to reduce potential survey fatigue and confusion. To understand the effect of image presentation on observer ratings, we included 6 pairs of control images with men who had not undergone hair transplant. The ratings of the control images revealed an observer preference for the image on the right; this individual was most often rated as younger and more attractive, successful, and approachable. Understanding the standardized mean differences and ordinal rank change for hair transplant recipients relative to controls was used to control for this potential bias. Even after accounting for this bias, hair transplant recipients still ranked 9 positions more attractive, 5 positions more successful, and 5 positions more approachable on a 0- to 100-point scale, with higher values corresponding to a more-positive rating. We expect that the true effect of the hair transplant procedure on each domain lies between the raw values and the values obtained after comparing the gradings of hair transplant recipients with those of controls. To better understand the value of the hair transplant on each domain, future studies should include more sophisticated randomization of pretransplant and posttransplant photographs.

A final point of consideration that becomes increasingly important as we aim to measure the effect size of a hair transplant is the candidacy of the recipient. There are many factors that contribute to the appropriateness of transplant, including age, pattern of hair loss, and number of follicular units needed to transplant. Due to the random image selection, we included a range of ages and variety of hair loss patterns. In addition, the men in this study had undergone what are considered to be small procedures on average of 1200 grafts. Thus, observers are asked to make judgments about results that may be subtle considering the small graft sizes. We believe that the effect size of this procedure will increase with better candidacy (eg, younger men), individuals with increasing amounts of hair loss, and those undergoing larger-sized grafts. Even after the above limitations are considered, the data prove to be robust, and this study should serve as a proof of concept for future investigations into the effect of cosmetic procedures on societal perceptions.

Conclusions

Individuals with AGA treated with hair transplant were rated as more attractive, successful, and approachable following surgery. They were also rated as appearing younger. These findings are relevant inbuilding an evidence-based body of literature surrounding the efficacy of hair transplant in the treatment of AGA.

Key Points.

Question

Does hair transplant improve casual observer ratings of age, attractiveness, successfulness, and approachability in men treated for androgenetic alopecia?

Findings

This randomized controlled survey of 122 participants indicated that men who underwent hair transplant were rated as appearing significantly more youthful, attractive, successful, and approachable.

Meaning

This study represents a pilot effort to contribute to an evidence-based body of literature to support the efficacy of hair transplant in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Ms Bater had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: All authors.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Bater, M. Ishii, Joseph, Nellis, L. E. Ishii.

Drafting of the manuscript: Bater, M. Ishii.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Bater, M. Ishii, Su, Nellis, L. E. Ishii.

Administrative, technical, or material support: M. Ishii, Joseph, Su, Nellis, L. E. Ishii.

Study supervision: M. Ishii, L. E. Ishii.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Additional Contributions: Kelli Nash and LouEllen Michel, RN, CORLN (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine), assisted with image collection. There was no financial compensation. We thank the patientdepicted in Figure 1 for granting permission to publish this information.

References

- 1.Thomas J. Androgenetic alopecia-current status. Indian J Dermatol. 2005;50(4):179–190. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamilton JB. Patterned loss of hair in man; types and incidence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1951;53(3):708–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1951.tb31971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norwood OT. Male pattern baldness: classification and incidence. South Med J. 1975;68(11):1359–1365. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197511000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis JA, Stebbing M, Harrap SB. Polymorphism of the androgen receptor gene is associated with male pattern baldness. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116(3):452–455. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Price VH. Treatment of hair loss. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(13):964–973. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909233411307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han SH, Byun JW, Lee WS, et al. Quality of life assessment in male patients with androgenetic alopecia: result of a prospective, multicenter study. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24(3):311–318. doi: 10.5021/ad.2012.24.3.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cranwell W, Sinclair R. Male androgenetic alopecia. In: De Groot LJ, Beck-Peccoz P, Chrousos G, et al., editors. Endotext. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc; p. 2000. Updated February 29, 2016. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK278957/. Accessed May 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stough D, Stenn K, Haber R, et al. Psychological effect, pathophysiology, and management of androgenetic alopecia in men. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(10):1316–1322. doi: 10.4065/80.10.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson D, Gonzalez M, Finlay AY. The effect of hair loss on quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(2):137–139. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wells PA, Willmoth T, Russell RJ. Does fortune favour the bald? psychological correlates of hair loss in males. Br J Psychol. 1995;86(pt 3):337–344. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1995.tb02756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cash TF. Losing hair, losing points? the effects of male pattern baldness on social impression formation. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1990;20(2):154–167. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avram MR, Cole JP, Gandelman M, et al. Roundtable Consensus Meeting of the 9th Annual Meeting of the International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery The potential role of minoxidil in the hair transplantation setting. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28(10):894–900. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rittmaster RS. Finasteride. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(2):120–125. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199401133300208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufman KD, Olsen EA, Whiting D, et al. Finasteride Male Pattern Hair Loss Study Group Finasteride in the treatment of men with androgenetic alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(4, pt1):578–589. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leyden J, Dunlap F, Miller B, et al. Finasteride in the treatment of men with frontal male pattern hair loss. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(6, pt 1):930–937. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orentreich N. Autografts in alopecias and other selected dermatological conditions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1959;83:463–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1960.tb40920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiell RC. A review of modern surgical hair restoration techniques. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2008;1(1):12–16. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.41150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dua A, Dua K. Follicular unit extraction hair transplant. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3(2):76–81. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.69015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Plastic Surgery Statistics Report. 2014 http://www.plasticsurgery.org/Documents/news-resources/statistics/2014-statistics/plastic-surgery-statsitics-full-report.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2016.

- 20.Nakano T, Tanaka K, Endo Y, et al. Atypical gaze patterns in children and adults with autism spectrum disorders dissociated from developmental changes in gaze behaviour. Proc Biol Sci. 2010;277(1696):2935–2943. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pillai KCS. Some new test criteria in multivariate analysis. Ann Math Stat. 1955;26(1):117–121. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawley DN. A generalization of Fisher’s z-test. Biometrika. 1938;30(1–2):180–187. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hotelling H. A generalized t test and measure of multivariate dispersion In: Proceedings of the Second Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1951. pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roy SN. On a heuristic method of test construction and its use in multivariate analysis. Ann Math Stat. 1955;24(2):220–238. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roy SN. P-statistics or some generalisations in analysis of variance appropriate to multivariate problems. Sankhya Indian J Stat. 1939;4:381–396. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galton F. Vox populi. Nature. 1907;75:450–451. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Surowiecki J. The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many Are Smarter Than the Few and How Collective Wisdom Shapes Business, Economies, Societies, and Nations. New York, NY: Doubleday; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Surowiecki J. Mass intelligence. Forbes. 2004 May 24; http://www.forbes.com/global/2004/0524/019.html. Accessed March 13, 2016.

- 29.Hunt N, McHale S. The psychological impact of alopecia. BMJ. 2005;331(7522):951–953. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7522.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stratou G, Ghosh A, Debevec P, Morency LP. Effect of illumination on automatic expression recognition: a novel 3D relightable facial database. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition and Workshops. 2011:611–618. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehu M, Little AC, Dunbar RIM. Sex differences in the effect of smiling on social judgments: an evolutionary approach. J Soc Evol Cult Psychol. 2008;2(3):103–121. [Google Scholar]