Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Though anecdotally linked, few studies have investigated the impact of facial paralysis on depression and quality of life (QOL).

OBJECTIVE

To measure the association between depression, QOL, and facial paralysis in patients seeking treatment at a facial plastic surgery clinic.

DESIGN, SETTING, PARTICIPANTS

Data were prospectively collected for patients with all-cause facial paralysis and control patients initially presenting to a facial plastic surgery clinic from 2013 to 2015. The control group included a heterogeneous patient population presenting to facial plastic surgery clinic for evaluation. Patients who had prior facial reanimation surgery or missing demographic and psychometric data were excluded from analysis.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

Demographics, facial paralysis etiology, facial paralysis severity (graded on the House-Brackmann scale), Beck depression inventory, and QOL scores in both groups were examined. Potential confounders, including self-reported attractiveness and mood, were collected and analyzed. Self-reported scores were measured using a 0 to 100 visual analog scale.

RESULTS

There was a total of 263 patients (mean age, 48.8 years; 66.9% were female) were analyzed. There were 175 control patients and 88 patients with facial paralysis. Sex distributions were not significantly different between the facial paralysis and control groups. Patients with facial paralysis had significantly higher depression, lower self-reported attractiveness, lower mood, and lower QOL scores. Overall, 37 patients with facial paralysis (42.1%) screened positive for depression, with the greatest likelihood in patients with House-Brackmann grade 3 or greater (odds ratio, 10.8; 95% CI, 5.13–22.75) compared with 13 control patients (8.1%) (P < .001). In multivariate regression, facial paralysis and female sex were significantly associated with higher depression scores (constant, 2.08 [95% CI, 0.77–3.39]; facial paralysis effect, 5.98 [95% CI, 4.38–7.58]; female effect, 1.95 [95% CI, 0.65–3.25]). Facial paralysis was associated with lower QOL scores (constant, 81.62 [95% CI, 78.98–84.25]; facial paralysis effect, −16.06 [95% CI, −20.50 to −11.62]).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

For treatment-seeking patients, facial paralysis was significantly associated with increased depression and worse QOL scores. In addition, female sex was significantly associated with increased depression scores. Moreover, patients with a greater severity of facial paralysis were more likely to screen positive for depression. Clinicians initially evaluating patients should consider the psychological impact of facial paralysis to optimize care.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE

2.

Facial expression serves as a sophisticated, conserved mechanism to convey emotional information during social interactions.1 A breakdown of this important social communication tool affects both a person’s self-concept and observers’ inferences.2 One potential breakdown experienced by patients is the loss of facial nerve function. Patients with facial paralysis can have impaired facial movement and resting facial asymmetry, resulting in facial deformity.

Across cultures and generations, facial deformity has been associated with significant psychosocial repercussions, including social stigma and psychological distress.2 Consequently, patients with facial deformity often experience negative self-image, low self-esteem, and social isolation.3 For patients without support and unable to cope, the social and psychological distress may lead to the development of maladaptive behaviors and depression.4 Along with understanding the universal impact of facial deformity, there has been further interest in understanding the associated penalties specific to the population of individuals with facial paralysis. Prior studies have found that observers perceive faces with facial paralysis as less attractive, more bothersome, and having a negative affect display compared with normal faces.5–7 Moreover, observers gazing at a paralyzed face have an altered pattern of facial attention.8 Given these findings, we can expect patients with facial paralysis to experience difficulties with social interactions and psychological distress. These negative consequences can lead patients to seek treatment by a facial plastic surgeon with the hopes of restoring facial appearance, self-image, and overall quality of life (QOL). While prior studies have underscored the impact for facial deformities in general, few studies have specifically investigated the psychological impact of facial paralysis involving depression and QOL.3,4,9,10 Furthermore, prior studies have not characterized the impact of facial paralysis severity on depression. Identifying patients with significant emotional distress resulting in depression supports optimal patient outcomes and experience.

The aim of the present study was to better understand the association between facial paralysis, depression, and QOL in patients seeking treatment by a facial plastic reconstructive surgeon. We hypothesize that patients with facial paralysis will have worse depression scores and consequently lower QOL scores compared with normal individuals. Moreover, our secondary hypothesis is that patients with facial paralysis are more likely to screen positive for depression compared with normal individuals. We postulate that, similar to patients with other facial deformities, patients with facial paralysis will report lower mood and self-attractiveness scores compared with normal individuals.

Methods

Patient Population and Study Overview

Johns Hopkins institutional review board approval was received for this prospective observational study. Patients initially presenting for unilateral facial paralysis evaluation were prospectively enrolled from October 2013 to March 2016 in the facial plastic surgery clinic of 3 facial plastic surgeons (P.J.B., K.D.O.B, and L.E.I.). Patients with facial paralysis of all levels of severity and etiologies were eligible. A heterogeneous group of control patients without facial paralysis was prospectively enrolled at initial presentation to a facial plastic surgery clinic. All patients 18 years or older and English speaking were eligible. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Patients were excluded (1) if they were younger than 18 years, (2) had prior facial paralysis surgery, (3) had a head and neck malignant neoplasm, (4) had prior head and neck surgery, and (5) were unable to independently complete questionnaires. Patients who did not have demographic or psychometric data were excluded from the model analysis. Patients were not compensated for participating.

Data Collection

Demographic information, clinical history, facial paralysis etiology, laterality of facial paralysis, and facial paralysis severity were collected by trained study personnel. Demographic data included age, sex, race, marital status, highest level of education, and socioeconomic status. Facial paralysis etiology was determined by clinical history. The House Brackman (HB) grade (1–6) was determined from baseline photographs.11

Patient psychometric data were collected using either paper or web-based validated questionnaires: (1) Beck Depression Inventory, (2) QOL, (3) self-reported attractiveness, and (4) overall mood. Patients were instructed to complete the questionnaires in an untimed manner. As previously described, the Beck Depression Inventory12 includes 21 questions with total scores ranging from 0 to 63, with higher scores corresponding to increasing depression, and scores of 10 or lower characterized as normal. Patients scoring 10 or higher on the Beck Depression Inventory were categorized as screening positive for at least mild depression (positive depression screen).12 Patients reported overall QOL on a visual analog scale from 0 (death) to 100 (perfect health).13 Patients rated their own attractiveness using a visual analog scale of 0 (least attractive) to 100 (most attractive). Patients rated their overall mood using a visual analog scale of 0 (very sad) to 100 (very happy).

Study Objectives

The primary objective was to measure the associations between depression, QOL, and facial paralysis. The secondary objective was to determine the likelihood of screening positive for mild depression in facial paralysis and control groups. Finally, we sought to compare mean QOL, depression, attractiveness, and overall mood scores between patients with facial paralysis (hereinafter, facial paralysis group) and control groups.

Statistical Analysis

Data were collected using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCAP; https://www.project-redcap.org) and analyzed using Stata SE software (version 13; StataCorp). Multiple analytic techniques were used in this study with the experiment-wide significance level set at α = .05.

Demographic and Psychometric Comparisons

Demographic characteristics and facial paralysis characteristics were examined. Next, differences in mean Beck Depression Inventory scores, QOL scores, self-reported attractiveness, and overall mood scores between facial paralysis and control groups were analyzed using the Hotelling T2, assuming a multivariate normal distribution, followed by individual planned hypothesis testing using t test. The Bonferroni method was used to correct for multiple comparisons.

Positive Depression Screen

The association between facial paralysis and screening positive for at least mild depression was examined. Subsequently, the effect of facial paralysis severity on the likelihood of screening positive for depression controlling for sex was examined using multiple logistic regression.

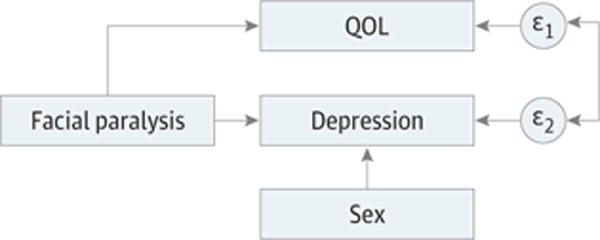

Structural Equation Modeling

Structural equation modeling was used to understand the associations between depression, QOL, and facial paralysis accounting for female sex, a known confounder for depression.14 As previously described, when relating patient-reported instruments to underlying domains and concepts, structural equation modeling is an effective approach to create an asymmetric multivariate regression model involving observed variables accounting for intrinsic sources of variance and covariance.15–17 A conceptual framework was generated to reflect the associa-tionsinourstructuralequationmodel(Figure).Sensitivityanaly-sis for missing data was performed using multiple imputation.18

Figure. Conceptual Path Diagram Demonstrating the Associations Among the Variables in the Structural Equation Model.

QOL indicates quality of life, ε1 indicates the error term for quality of life, and ε2 indicates the error term for depression.

Results

A total of 263 patients were prospectively enrolled from October 2013 to March 2016. Of the 263 eligible patients, 250 patients fully completed the provided questionnaires, with a response rate of 95.1%. Thirteen patients were excluded from analysis. Most patients were white (79%), female (67%), married or engaged (63%), and educated with a 4-year college degree (36%). The mean (SD) age was 49 (16) years. Overall, 88 patients (33.5%) were in the facial paralysis group and 175 patients (66.5%) were in the control group (Table 1). Comparison of sex distribution between both groups revealed no significant difference ( ; P = .81). Within the facial paralysis group (Table 2), the most common facial paralysis etiologies included acoustic neuroma resection (31.8% of patients) and Bell palsy (29.6%) and the most common facial paralysis severity was HB grade 6 (11.0%).

Table 1.

Demographic Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Facial Paralysis (n = 88) |

Control (n = 275) |

|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 52.0 (14.9) | 47.5 (15.6) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 30 (34.1) | 57 (32.6) |

| Female | 58 (65.9) | 118 (67.4) |

| Race | ||

| White | 72 (81.8) | 135 (77.1) |

| African American | 7 (7.9) | 24 (13.7) |

| Hispanic | 4 (4.6) | 4 (2.3) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 4 (4.6) | 7 (4.0) |

| Other | 1 (1.1) | 5 (2.9) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 26 (29.5) | 72 (41.4) |

| Married or engaged | 62 (70.5) | 102 (58.6) |

| Educational status | ||

| High school/GED test | 10 (11.4) | 15 (8.7) |

| Some college | 15 (17.0) | 21 (12.1) |

| 2-y college degree | 6 (6.8) | 12 (6.9) |

| 4-y college degree | 31 (35.2) | 64 (37.0) |

| Master’s degree | 16 (18.2) | 47 (27.2) |

| Doctoral degree | 10 (11.4) | 14 (8.1) |

Abbreviation: GED, General Educational Development.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients With Facial Paralysis

| Facial Paralysis Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Etiology of facial paralysis | |

| Acoustic neuroma | 28 (31.8) |

| Bell palsy | 26 (29.6) |

| CNS tumor | 6 (6.8) |

| Ramsay Hunt syndrome | 5 (5.7) |

| Iatrogenic | 4 (4.6) |

| Otologic | 4 (4.6) |

| Other | 4 (4.6) |

| Parotid malignant neoplasm | 3 (3.4) |

| Facial schwannoma | 3 (3.4) |

| Trauma | 3 (3.4) |

| Congenital | 2 (2.3) |

| Severity of facial paralysis, HB grade | |

| I (Control) | 175 (66.5) |

| II | 19 (7.2) |

| III | 20 (7.6) |

| IV | 9 (3.4) |

| V | 11 (4.2) |

| VI | 29 (11.0) |

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system tumor; HB, House-Brackmann.

Patient psychometric characteristics are presented in Table 3. Multivariate analysis using Hotelling T2 test comparing mean Beck Depression Inventory scores, QOL scores, self-reported attractiveness, and overall mood scores revealed a significant difference between the group with facial paralysis and the control group (T2 = 71.24; F4,240 = 17.59; P < .001). Further planned hypothesis testing, correcting for multiple comparisons, showed that patients with facial paralysis had significantly higher depression scores (t248 = −7.17; P < .001), lower QOL scores (t261 = 7.07; P < .001), lower self-reported attractiveness (t256 = 5.93; P < .001), and lower mood scores (t261 = 5.79; P < .001).

Table 3.

Psychometric Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Group, Mean (SD)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Facial Paralysis (n = 88) |

Control (n = 176) |

|

| QOL, scale of 0–100 | 65.6 (16.8) | 81.7 (14.0) |

| BDI category, range, 0–63, % | 9.4 (8.5) | 3.4 (4.6) |

| Normal (0–9)b | 58 | 91 |

| Mild depression (10–18) | 31 | 8 |

| Moderate depression (19–29) | 8 | 1 |

| Severe depression (≥30) | 3 | 0 |

| Attractiveness (0–100) | 51.3 (21.4) | 66.0 (16.8) |

| Overall mood (0–100) | 56.6 (21.7) | 70.8 (16.5) |

Abbreviations: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; QOL, quality of life.

P < .001 for all comparisons; corrected for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni procedure.

Standard cutoff scores indicating severity of depression.

Overall, 37 patients with facial paralysis and 13 control patients screened positive for at least mild depression. A positive depression screen was significantly more common in the facial paralysis group (42.1%) compared with the control group (8.1%; ; P < .001). The prevalence of depression in the control group, which contains more female patients, similarly reflects the prevalence of depression in the United States population (7.6%).19 There was no significant association between facial paralysis etiology and screening positive for depression ( ; P = .93).

Multiple logistic regression (LR) analysis examining the association of facial paralysis severity and the likelihood of screening positive for depression (controlled for female sex) showed that compared with patients without paralysis, patients with HB grade 3 or greater facial paralysis were significantly associated with a positive depression screen ( ; P < .001; constant, 0.06; 95% CI, 0.03–0.14). The odds of patients screening positive for depression significantly increased in patients with HB grade 3 or greater (OR, 10.80; 95% CI, 5.12–22.75) compared with control patients. However, there was no significant increase in the odds of screening positive for depression for patients with HB grade 2 (OR, 3.15; 95% CI, 0.91–10.96; P = .07) compared with control patients.

It has been previously noted that facial deformities and female sex are associated with depression.4,14 Moreover, facial paralysis has been shown to be associated with lower QOL.20,21 However, there is no significant difference in quality life between men and women.22 With consideration of these findings, a structured equation model is presented in Table 4 showing the impact of facial paralysis and female sex on depression scores and the impact of facial paralysis on QOL scores. Results from sensitivity analysis for missing data using multiple imputation did not show significantly different outcomes; hence, the simpler model is presented. On structural equation modeling, facial paralysis and female sex were significantly associated with higher depression scores (constant, 2.08 [95% CI, 0.77–3.39]; facial paralysis effect, 5.98 [95% CI, 4.38–7.58]; female effect, 1.95 [95% CI, 0.65–3.25]). In addition, facial paralysis was associated with lower QOL scores (constant, 81.62 [95% CI, 78.98–84.25]; facial paralysis effect, −16.06 [95% CI, −20.50 to −11.62]).

Table 4.

Structural Equation Model for Quality of Life (QOL) and Depression

| Fixed Effects, Variable or Covariate | Coefficient | SE (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| QOLa | ||

| Facial paralysisb,c | −16.06 | 2.26 (−20.50 to −11.62) |

| Constantc | 81.62 | 1.34 (78.98 to 84.25) |

| Depressiond | ||

| Facial paralysisc | 5.98 | 0.82 (4.38 to 7.58) |

| Femalee,f | 1.95 | 0.66 (0.65 to 3.25) |

| Constantc | 4.03 | 0.52 (3.01 to 5.06) |

| Random Effects, Parameter | Estimate | SE (95% CI) |

| Variance, residual | ||

| (QOL) facial paralysis | 292.3 | 26.15 (245.38 to 348.41) |

| (Depression) female | 37.8 | 3.39 (31.78 to 45.13) |

| Covariance, residual (QOL, depression) | −64.5 | 7.81 (−79.77 to −49.17) |

Abbreviations: QOL, quality of life; SE, standard error.

QOL, coded on a scale of 0 to 100.

Facial paralysis absent, 0; facial paralysis present, 1.

P < .001.

Depression, coded on a scale of 0 to 63.

Female patient, 0; male patient, 1.

P= .003.

Discussion

In this study population, treatment-seeking patients with facial paralysis were associated with higher depression scores and lower QOL scores compared with patients without facial paralysis. Moreover, female patients were associated with higher depression scores. When screening for depression, patients seeking treatment for facial paralysis were significantly more likely to screen positive for at least mild depression compared with control patients. Furthermore, patients with more severe facial paralysis (HB grade ≥3) were significantly more likely to screen positive for depression. In addition to higher depression and lower QOL scores, patients with facial paralysis had significantly lower self-reported attractiveness and overall mood scores compared with control patients. These findings emphasize the importance of considering the psychological impact of facial paralysis, and its bearing on QOL, on patients seeking treatment for facial paralysis.

A person’s self-concept is a dynamic construct associated with intrapersonal and interpersonal processes.23 This multidimensional framework arises from information a person gathers about himself or herself influencing perceptions of personal attributes akin to the process of assimilation and accommodation described by Jean Piaget.24 A prior study25 has shown that stability and clarity in a person’s self-concept is positively correlated with extraversion, positive affect, and self-esteem. However, disruption of one’s self-concept creates dissonance between the perceived “actual” and “ideal” self, which can be associated with depression, anxiety, and neuroticism.23,26 Facial paralysis and the resultant facial deformity are examples of potential disruption. Ishii et al5,6 showed that patients with facial paralysis have impaired affect display and are considered less attractive. Moreover, the asymmetry associated with facial paralysis causes a measurable attentional distraction.8,27 These findings underscore the potential negative implications of facial paralysis on social interactions. In a study by Bradbury et al28 involving structured patient interviews, 89.6% of patients with facial paralysis complained of intrusive questions regarding their appearance from strangers and acquaintances with half of the group experiencing psychological distress. These experiences damage a patient’s self-concept, deter social interactions, and promote social isolation.3 Consequently, patients internalizing these negative interactions may adjust their self-image. Our results support this concept because patients with facial paralysis had significantly lower self-reported attractiveness compared with patients without facial paralysis. Furthermore, the psychosocial distress associated with facial paralysis has the potential to result in depression.

Various studies have investigated the association of facial deformity and depression.4,29–31 However, few studies have characterized the impact of facial paralysis on depression. In a retrospective study, Walker et al32 found that 40% of patients with facial paralysis showed symptoms suggestive of an anxiety or depressive mood disorder. Moreover, Pouwels et al33 showed that 27% of patients with facial paralysis, either before or after surgery, were identified as having a depressive disorder. Similarly, we found that a significant proportion of the patients with facial paralysis screened positive for depression at initial evaluation compared with control patients. Furthermore, our results demonstrate a significantly increased likelihood of patients screening positive for depression in those presenting with more severe paralysis (ie, HB grade ≥3).

In the present study, we further describe the association of facial paralysis and depression by presenting a statistical model showing that patients with facial paralysis are significantly associated with an increase in depression scores. Regression quantified the effect of facial paralysis while accounting for the impact of female sex, a known confounder for depression (Table 4).14 These findings suggest that clinicians evaluating patients seeking treatment for facial paralysis may wish to consider either formal or informal screening for depression, particularly in patients with HB grade 3 or greater paralysis. In doing so, clinicians can identify patients who are at greater risk for postoperative dissatisfaction given the underlying depressive disorder, which may ultimately lead to happier patients.28,34 Importantly, clinicians may even refer patients to the appropriate psychiatric services, mitigating the significant costs and morbidity associated with untreated depression.35–37

Patients often seek treatment for facial paralysis in hopes of restoring their QOL. Several studies have examined the association between facial paralysis and QOL.20,21,38,39 In 2 cross-sectional studies assessing QOL in patients with acoustic neuroma, Ryzenman et al21 found that 28% of patients were significantly affected by facial weakness, and Lee et al38 found a significantly lower QOL scores in patients with facial paralysis compared with normal patients. Looking at patients with all-cause facial paralysis at initial presentation, Kleiss et al20 found that patients with facial paralysis have a mean (SD) baseline Facial Clinimetric Evaluation score of 47.3 (19.2) representing health-related QOL on a scale of 0 to 100. Our study expands on these findings by comparing QOL scores between patients with all-cause facial paralysis and control patients and presenting a model showing that QOL scores are significantly affected by facial paralysis. Relative to the average QOL scores reported by the US population (81–87 out of 100), our results demonstrate a significant decrease in QOL for patients with facial paralysis (Table 4).40 These findings emphasize the importance of considering QOL when treating patients with facial paralysis to achieve our goal of optimizing patient outcomes.

Limitations

There are several limitations when examining the associations among depression, QOL, and facial paralysis. First, we could not capture all patients with facial paralysis in the population. We were limited to assessing patients seeking treatment for facial paralysis, which may differ psychologically from patients who do not present for evaluation. It is possible that patients presenting for treatment are inherently predisposed to increased psychosocial distress compared with the other patients with facial paralysis. Next, our study does not consider duration of paralysis at the time of presentation when assessing depression. However, prior studies32,41 report mixed results regarding the association between duration of paralysis and mood disorders. In addition, our study relies on specific subjective psychometric instruments to infer the complex, multifaceted domains of QOL and depression. We likely missed other factors affecting these domains. Yet, we can account for these variables in the residual variance of our regression model. Finally, the population in this study included only patients presenting to a facial plastic surgery clinic, which limits the generalizability of the results.

Nonetheless, these data demonstrate that patients with facial paralysis are significantly associated with lower QOL and higher depression scores. To better understand QOL and depression in the population of patients with facial paralysis, future investigations should strive to include both patients presenting to all clinicians and patients who do not present for evaluation. In addition, future studies may find patient predictors associated with a worse psychological response to facial paralysis. This may highlight the range of innate coping ability allowing patients to preserve their self-concept. In addition, further investigation is warranted to better characterize the effect of facial paralysis severity on psychological health. Finally, future prospective studies may examine the effect of facial reanimation surgery on depression and QOL. With the aim of providing patient-centered care to improve QOL, identifying patients with significant psychosocial distress resulting in depression allows clinician to deliver treatment potentially restoring facial appearance, mental health, and self-concept.

Conclusions

Facial paralysis was significantly associated with increased depression scores and worse QOL scores. Consistent with prior literature, female sex is also significantly associated with increased depression scores. Furthermore, there is no significant association between facial paralysis etiology and screening positive for depression. However, patients with more severe facial paralysis (HB grade ≥3) were more likely to screen positive for depression. Clinicians initially evaluating patients seeking treatment for facial paralysis should consider the psychological impact of facial paralysis to better direct patients to the appropriate psychiatric services if required.

Key Points.

Question

What is the association between facial paralysis, depression, and quality of life in patients seeking treatment by a facial plastic reconstructive surgeon?

Findings

In study of 263 patients, patients seeking treatment for facial paralysis were significantly associated with higher depression scores and lower quality-of-life scores compared with patients without facial paralysis. Moreover, patients with greater severity of facial paralysis were significantly more likely to screen positive for depression.

Meaning

Clinicians initially evaluating patients should consider the psychological impact of facial paralysis to better direct patients to appropriate services if needed.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Nellis had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Nellis, M. Ishii, Boahene, L. E. Ishii.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Nellis, M. Ishii, Byrne, Dey, L. E. Ishii.

Drafting of the manuscript: Nellis, L. E. Ishii.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Nellis, M. Ishii, Dey, L. E. Ishii.

Administrative, technical, or material support: M. Ishii, Boahene, L. E. Ishii.

Study supervision: M. Ishii, Byrne, Dey, L. E. Ishii.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Previous Presentation: This study was an oral presentation at the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Spring Meeting; May 19–20, 2016; Chicago, Illinois.

References

- 1.Frith C. Role of facial expressions in social interactions. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364(1535):3453–3458. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw WC. Folklore surrounding facial deformity and the origins of facial prejudice. Br J Plast Surg. 1981;34(3):237–246. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(81)90001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macgregor FC. Facial disfigurement: problems and management of social interaction and implications for mental health. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1990;14(4):249–257. doi: 10.1007/BF01578358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valente SM. Visual disfigurement and depression. Plast Surg Nurs. 2004;24(4):140–146. doi: 10.1097/00006527-200410000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishii L, Godoy A, Encarnacion CO, Byrne PJ, Boahene KD, Ishii M. Not just another face in the crowd: society’s perceptions of facial paralysis. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(3):533–538. doi: 10.1002/lary.22481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishii LE, Godoy A, Encarnacion CO, Byrne PJ, Boahene KD, Ishii M. What faces reveal: impaired affect display in facial paralysis. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(6):1138–1143. doi: 10.1002/lary.21764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dey JK, Ishii M, Boahene KD, Byrne PJ, Ishii LE. Changing perception: facial reanimation surgery improves attractiveness and decreases negative facial perception. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(1):84–90. doi: 10.1002/lary.24262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishii L, Dey J, Boahene KD, Byrne PJ, Ishii M. The social distraction of facial paralysis: objective measurement of social attention using eye-tracking. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(2):334–339. doi: 10.1002/lary.25324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levine E, Degutis L, Pruzinsky T, Shin J, Persing JA. Quality of life and facial trauma: psychological and body image effects. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;54(5):502–510. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000155282.48465.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradbury E. Meeting the psychological needs of patients with facial disfigurement. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;50(3):193–196. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93(2):146–147. doi: 10.1177/019459988509300202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shmueli A. The visual analog rating scale of health-related quality of life: an examination of end-digit preferences. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:71. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin LA, Neighbors HW, Griffith DM. The experience of symptoms of depression in men vs women: analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(10):1100–1106. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deshpande PR, Rajan S, Sudeepthi BL, Abdul Nazir CP. Patient-reported outcomes: a new era in clinical research. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2(4):137–144. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.86879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atkinson MJ, Lennox RD. Extending basic principles of measurement models to the design and validation of patient reported outcomes. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:65. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bollen K, Lennox R. Conventional wisdom on measurement: a structural equation perspective. Psychol Bull. 1991;110(2):305–314. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.2.305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patrician PA. Multiple imputation for missing data. Res Nurs Health. 2002;25(1):76–84. doi: 10.1002/nur.10015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pratt LABD. Depression in the US Household Population, 2009–2012. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. (Vol NCHS Data Brief No. 172). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleiss IJ, Hohman MH, Susarla SM, Marres HA, Hadlock TA. Health-related quality of life in 794 patients with a peripheral facial palsy using the FaCE scale: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Otolaryngol. 2015;40(6):651–656. doi: 10.1111/coa.12434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryzenman JM, Pensak ML, Tew JM., Jr Facial paralysis and surgical rehabilitation: a quality of life analysis in a cohort of 1,595 patients after acoustic neuroma surgery. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26(3):516–521. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000169786.22707.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mercier C, Péladeau N, Tempier R. Age, gender and quality of life. Community Ment Health J. 1998;34(5):487–500. doi: 10.1023/a:1018790429573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markus H, Wurf E. The dynamic self-concept: a social psychological perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 1987;38(1):299–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.38.020187.001503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piaget J. Piaget’s Theory. 3rd. New York, NY: Wiley; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campbell JD, Assanand S, Di Paula A. The structure of the self-concept and its relation to psychological adjustment. J Pers. 2003;71(1):115–140. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.t01-1-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Styła R. Shape of the self-concept clarity change during group psychotherapy predicts the outcome: an empirical validation of the theoretical model of the self-concept change. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1598. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dey JK, Ishii LE, Byrne PJ, Boahene KD, Ishii M. Seeing is believing: objectively evaluating the impact of facial reanimation surgery on social perception. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(11):2489–2497. doi: 10.1002/lary.24801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradbury ET, Simons W, Sanders R. Psychological and social factors in reconstructive surgery for hemi-facial palsy. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59(3):272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lima LS, Ribeiro GS, Aquino SN, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in patients with cleft lip and palate. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;81(2):177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lim SY, Lee D, Oh KS, et al. Concealment, depression and poor quality of life in patients with congenital facial anomalies. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(12):1982–1989. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2010.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Sousa A. Psychological issues in oral and maxillofacial reconstructive surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46(8):661–664. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.07.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walker DT, Hallam MJ, Ni Mhurchadha S, McCabe P, Nduka C. The psychosocial impact of facial palsy: our experience in one hundred and twenty six patients. Clin Otolaryngol. 2012;37(6):474–477. doi: 10.1111/coa.12026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pouwels S, Beurskens CH, Kleiss IJ, Ingels KJ. Assessing psychological distress in patients with facial paralysis using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69(8):1066–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sykes JM. Managing the psychological aspects of plastic surgery patients. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;17(4):321–325. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e32832da0f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kessler RC. The costs of depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vilhauer JS, Cortes J, Moali N, Chung S, Mirocha J, Ishak WW. improving quality of life for patients with major depressive disorder by increasing hope and positive expectations with future directed therapy (FDT) Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(3):12–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mavros MN, Athanasiou S, Gkegkes ID, Polyzos KA, Peppas G, Falagas ME. Do psychological variables affect early surgical recovery? PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e20306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee J, Fung K, Lownie SP, Parnes LS. Assessing impairment and disability of facial paralysis in patients with vestibular schwannoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133(1):56–60. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindsay RW, Bhama P, Hadlock TA. Quality-of-life improvement after free gracilis muscle transfer for smile restoration in patients with facial paralysis. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2014;16(6):419–424. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2014.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fryback DG, Dunham NC, Palta M, et al. US norms for six generic health-related quality-of-life indexes from the National Health Measurement study. Med Care. 2007;45(12):1162–1170. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31814848f1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fu L, Bundy C, Sadiq SA. Psychological distress in people with disfigurement from facial palsy. Eye (Lond) 2011;25(10):1322–1326. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]