Abstract

Dopamine D3 receptor ligands are potential medications for psychostimulant addiction. Medication assessment may benefit from preclinical studies that evaluate chronic medication effects on choice between an abused drug and an alternative, nondrug reinforcer. This study compared acute and chronic effects of dopamine D2- and D3-preferring ligands on choice between intravenous cocaine and palatable food in rats. Under baseline conditions, cocaine maintained dose-dependent increases in cocaine choice and reciprocal decreases in food choice. Acutely, the D2 agonist R-(−)-norpropylapomorphine (NPA) and antagonist L-741,626 [3-[[4-(4-chlorophenyl)-4-hydroxypiperidin-l-yl]methyl-1H-indole] produced leftward and rightward shifts in cocaine dose-effect curves, respectively, whereas the partial agonist terguride had no effect. All three drugs dose-dependently decreased food-maintained responding. Chronically, the effects of R-(−)-norpropylapomorphine and L-741,626 on cocaine self-administration showed marked tolerance, whereas suppression of food-reinforced behavior persisted. Acute effects of the D3 ligands were less systematic and most consistent with nonselective decreases in cocaine- and food-maintained responding. Chronically, the D3 agonist PF-592,379 [5-[(2R,5S)-5-methyl-4-propylmorpholin-2-yl]pyridin-2-amine] increased cocaine choice, whereas an intermediate dose of the D3 antagonist PG01037 [N-[(E)-4-[4-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl]but-2-enyl]-4-pyridin-2-ylbenzamide] produced a therapeutically desirable decrease in cocaine choice early in treatment; however, tolerance to this effect developed, and lower and higher doses were ineffective. D3 ligands failed to significantly modify total cocaine intake but caused persistent decreases in food intake. Thus, D2-and D3-preferring ligands showed distinct profiles, consistent with different pharmacological actions. In addition, these results highlight the role of acute versus chronic treatment as a determinant of test drug effects. With the possible exception of the D3 antagonist PG01037, no ligand was promising in terms of cocaine addiction treatment.

Introduction

Substance use disorders have become a problem of epidemic proportions in the United States and worldwide. Cocaine remains one of the most widely used illegal substances, and despite decades of research, there is no approved medication to treat addiction to cocaine (O’Connor et al., 2014; Skolnick, 2015; Czoty et al., 2016). Ligands acting at receptors of the dopamine D2 family (D2/D3/D4) modulate cocaine self-administration behavior in laboratory animals: agonists produce leftward shifts of the cocaine dose-effect function, whereas antagonists produce rightward shifts consistent with surmountable antagonism (Bergman et al., 1990; Caine et al., 1999; Barrett et al., 2004). As medication strategies, D2-preferring or nonsubtype-selective D2-family antagonists were not promising, largely because of adverse effects limiting the use of effective doses, and because “anticocaine” effects observed with acute administration eroded when given chronically (see the Discussion). The D3 subtype attracted attention as a potential target for treating psychostimulant addiction, owing to its restricted localization and high concentration in parts of the mesolimbic reward pathway, its high affinity for dopamine, and the differential alteration of D2 versus D3 receptor availability as a consequence of psychostimulant use (for review see Heidbreder and Newman, 2010; Keck et al., 2015; Sokoloff and Le Foll, 2017). Specifically, postmortem and positron emission tomography studies suggest that at least some psychostimulant users, especially heavy users, have elevated D3 receptor availability and decreased D2 receptor availability relative to controls (Staley and Mash, 1996; Segal et al., 1997; Boileau et al., 2012; but see Meador-Woodruff et al., 1995). In rats and monkeys, long-term cocaine exposure was shown to increase D3 receptor availability, decrease D2 receptor availability, and/or decrease D2/D3 ratios (Le Foll et al., 2002; Neisewander et al., 2004; Nader et al., 2006; Collins et al., 2011). Unlike D2 receptor antagonists, D3 receptor antagonists administered acutely do not decrease cocaine self-administration under experimental conditions in which cocaine is available at relatively low cost (e.g., low response requirement, no competing reinforcers), but they can decrease cocaine taking under higher cost conditions, although selectivity over reduction in food-reinforced responding was often moderate (Heidbreder and Newman, 2010; Sokoloff and Le Foll, 2017).

Critical review of laboratory animal evaluations of candidate medications strongly supports the notion that predictive validity is dependent on the inclusion of chronic dosing regimens, whereas acute-only results have often been misleading (Haney and Spealman, 2008; Czoty et al., 2016; see specific examples in the Discussion). Furthermore, effects on cocaine self-administration (i.e., direct reinforcing effects of cocaine) have predicted clinical efficacy better than modulation of subjective or conditioned effects alone (Comer et al., 2008; Haney and Spealman, 2008). One type of self-administration assay, choice procedures, is gaining popularity, with various proposed advantages over single-reinforcer assays (Banks et al., 2015a; Banks and Negus, 2017). Choice procedures allow behavior allocation to be assessed independently of rates of responding, and they also allow simultaneous evaluation of effects on cocaine and food intake. Most importantly for this investigation, we have found that choice procedures in rats are well suited to comparing acute versus chronic effects of pharmacological manipulations. We previously used a choice procedure to compare acute and subchronic effects of d-amphetamine, and of the D2/D3 partial agonist aripiprazole, obtaining results in line with human studies (Thomsen et al., 2008, 2013; Greenwald et al., 2010; Haney et al., 2011). Other evidence also supports a concordance between effects of medication maintenance on cocaine choice in preclinical studies, cocaine choice in human laboratory studies, and cocaine use in clinical trials (Foltin et al., 2015; Czoty et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2016; Lile et al., 2016).

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate dopamine D3 receptor–selective (or D3-preferring) ligands, both agonists and antagonists, as a continuous (sub)chronic treatment, in a direct comparison with D2 receptor ligands. The effects of chronic administration were also compared with acute dosing effects. Table 1 shows the ligands tested and their respective affinities for D2 and D3 receptors, with references from previously published sources. All compounds penetrate the blood-brain barrier, except for RGH-237 [N-{4-[4-(3-aminocarbonyl-phenyl)-piperazin-1-yl]-butyl}-4-bromo-benzamide], which showed poor brain penetration but still showed behavioral effects consistent with partial D3 receptor agonist activity (Heidbreder and Newman, 2010; Mason et al., 2010; Morgan et al., 2012; and see references in Table 1). We tested the hypothesis that D2 and D3 receptor ligands would differ in chronic as well as acute effects and, specifically, that chronic administration of a D3 receptor ligand could decrease cocaine self-administration in the cocaine versus food choice procedure in rats.

TABLE 1.

Classifications based on relative efficacies and affinities for dopamine D2 or D3 receptors determined in vitro, from published reports.

| Ligand | Classification | Binding Selectivity (D2 − Ki/D3 − Ki) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPA | D2/D3 agonist | 0.6–8 | Freedman et al., 1994; Sautel et al., 1995 |

| Terguride | D2/D3 partial agonist | 1.1 | Millan et al., 2002 |

| L-741,626 | D2-preferring antagonist | 0.02–0.07 | Kulagowski et al., 1996; Millan et al., 2000; Caine et al., 2002 |

| PD-128,907 | D3-preferring agonist | 6.3–210 | Pugsley et al., 1995; Sautel et al., 1995 |

| PF-592,379 | D3-selective agonist | >470 | Attkins et al., 2010; Collins et al., 2012 |

| RGH-237 | D3-selective partial agonist | >1000 | Gyertyán et al., 2007 |

| PG01037 | D3-selective antagonist | 133 | Grundt et al., 2005 |

Materials and Methods

Animals

Experimentally naïve male Sprague-Dawley rats were acquired at 8 weeks of age from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and acclimated to the laboratory for at least a week before training began. Rats were housed individually with free access to water in a temperature- and humidity-controlled facility maintained on a 12-hour/12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 07:00). Rats were fed approximately 17 g standard rat chow daily (Rat Diet 5001; PMI Feeds, Inc., St. Louis, MO), adjusted to maintain a healthy 400–500 g body weight. For enrichment, “treats” were provided once or twice weekly, typically bacon-flavored biscuits (5 g; Bio-Serve, Frenchtown, NJ). Behavioral testing was conducted during the light phase. Husbandry and testing complied with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Committee on Laboratory Animal Resources, and all protocols were approved by the McLean Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Apparatus

Operant conditioning chambers (21 cm × 29.5 cm × 24.5 cm) and associated hardware from MED Associates (Georgia, VT) were placed within sound-attenuating cubicles equipped with a house light and an exhaust fan. Each chamber contained three response levers 3 cm above the grid floor, two “reinforcer” levers (referred to as the “left” and “right” levers) on one wall, and a third “observer” lever centered on the opposite wall. A steel cup between the reinforcer levers, 2 cm above the floor, served as a receptacle for the delivery and consumption of liquid food reinforcers. A three-light array (red, yellow, and green) was located above the right lever and illuminated to signify the availability of food. An identical array with one additional yellow light was located above the left lever and was used to signal the cocaine dose available. A white light was located above the observer lever. Each cubicle also contained two syringe pumps (3.3 rpm, model PHM-100, MED Associates, Georgia, VT) for the delivery of liquid food and intravenous cocaine, respectively, through Tygon tubing. Cocaine was delivered using a single-channel fluid swivel (MS-1; Lomir Biomedical, Malone, NY) mounted on a balance arm, which allowed rats free movement.

Operant Training and Surgery

Rats were trained and tested in a cocaine versus food choice procedure as previously described (Thomsen et al., 2008, 2013, 2014). Between the completion of the acute dosing experiments and the start of the chronic dosing experiments, the procedure was slightly modified in two ways to allow for more efficient training: 1) acute experiments used static levers, whereas retractable levers were used in the chronic experiments; and 2) the reinforcer magnitudes (food concentration and cocaine doses) were adjusted slightly (see below). All other parameters and training methods were identical and are briefly outlined below.

Food Training.

First, lever pressing was acquired in daily 2-hour sessions, with liquid food (75 µl vanilla- flavored Ensure nutrition drink; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott, IL) reinforcing responding under a fixed ratio (FR) 1 schedule of reinforcement. Food was diluted to 56% in water for acute dosing experiments and to 32% for chronic experiments. Illumination of the triple cue light above the right lever signaled food availability, and cues were turned off at reinforcer delivery. Responses on the other levers (cues off) were recorded but had no scheduled consequences. When ≥50 reinforcers were earned within one 2-hour session, the response requirement was gradually increased to FR 5. When rats again earned ≥50 reinforcers, a chain schedule was introduced in which one response on the observer lever initiated an FR 5 schedule on the right lever (see Thomsen et al., 2013 for details). When rats again earned ≥50 food reinforcers per session for five consecutive sessions (training criteria), they were implanted with catheters.

Surgery and Catheter Maintenance.

Rats were anesthetized with an isoflurane/oxygen vapor mixture and implanted with chronic indwelling jugular vein catheters (see Thomsen and Caine, 2005). A catheter was inserted 3.7 cm into the external jugular vein and anchored to the vein. The catheter ran subcutaneously to the midscapular region where the base was located. Single doses of an analgesic (5 mg/kg ketoprofen) and an antibiotic (10 mg/kg amikacin) were administered subcutaneously immediately before surgery. Rats were allowed approximately 7 days of recovery before being given access to intravenous cocaine. During this period, a prophylactic dose of cefazolin (30–40 mg/kg) was delivered daily through the catheter. Thereafter, catheters were flushed daily with sterile saline containing heparin (3 USP U/0.1 ml). Catheter patency was verified daily by withdrawing and immediately reinfusing a few microliters of blood through the catheter (enough for visual detection of blood); if blood could not be withdrawn, catheter patency was tested by administering 0.05–0.1 ml of a ketamine-midazolam mixture (15 + 0.75 mg/ml) through the catheter and observing prominent signs of sedation within 3 seconds of infusion. Only data collected with demonstrated patent catheters were included.

Cocaine Self-Administration Training.

Cocaine self-administration started with daily 2-hour sessions, under an FR 1 FR 1 timeout 20 seconds chain schedule, left lever active. Responses on the right lever were recorded and reset the ratio requirement on the left lever. Sessions started with a noncontingent “priming” cocaine infusion, and then flashing of the full cue light array over the left lever indicated the availability of cocaine at 1.0 mg /kg per infusion. Cues were turned off at reinforcer delivery. The response requirement was gradually increased to FR 1 FR 5, and training continued until cocaine self-administration behavior stabilized, which was defined as three consecutive sessions with ≥10 mg/kg cocaine self-administered per 2-hour session and ≥90% of left plus right lever responses emitted on the drug-reinforced lever. Sessions were then modified to include five 20-minute components of cocaine availability (1.0 mg/kg per infusion), with 2-minute intercomponent timeout periods, using the same schedule of reinforcement. This schedule remained in effect until behavior stabilized (i.e., ≥10 mg/kg cocaine self-administered per session and ≥1 reinforcer earned per component). Rats were then given access to 0.32 mg/kg cocaine per infusion for at least 1 day before choice training began, to observe increased rates of responding.

Cocaine versus Food Choice Training.

Daily sessions consisted of five 20-minute components separated by 2-minute timeout periods. Responding was reinforced under a FR 1 [concurrent FR 5 FR 5] chain schedule, with responding on the right lever being reinforced with liquid food and responding on the left being reinforced with cocaine infusions of increasing doses for each component as follows: 0, 0.032, 0.1, 0.32, and 1.0 mg/kg per infusion (in the acute experiment) or 0, 0.056, 0.18, 0.56, and 1.0 mg/kg per infusion (in the chronic experiment). Responding on one reinforcer lever reset the ratio requirement on the other. Cocaine doses were achieved by varying the infusion time, adjusted to each rat’s body weight. The light array over the left lever flashed when cocaine was available, indicating the unit dose available: no light for 0, green for 0.032/0.056 mg/kg per infusion, green plus yellow for 0.10/0.18 mg/kg per infusion, green plus yellow plus red for 0.32/0.56 mg/kg per infusion, and green plus yellow plus red plus yellow for 1.0 mg/kg per infusion; cues were turned off at reinforcer delivery. Per component, 15 total reinforcers were available (completion of the response requirement on the left lever during availability of the zero cocaine dose counted as one reinforcer). If all 15 reinforcers were earned in less than 20 minutes, all stimulus lights were extinguished, and responding had no scheduled consequences for the remainder of the 20-minute component. Choice training continued until behavior stabilized satisfying the criteria: 1) three consecutive sessions with ≥5 reinforcers/component earned in components 1–4 and 2) ≥1 reinforcer earned in component 5, and 3) with the dose of cocaine producing ≥80% cocaine choice on any given day remaining within one-half log unit of the 3-day mean.

Testing

Once training was completed, we tested the effects of D2- and D3-preferring agonists, partial agonists, and antagonists, under acute and chronic dosing conditions. Rats were allocated to test groups randomly. As much as possible, doses of each drug were tested within subjects, but due to attrition, additional rats had to be added to some dose groups. Rats had at least three sessions of baseline between acute doses or at least 1 week between chronic doses. Baseline choice behavior had to satisfy the original criteria (see above) in order for a rat to test again. If the cocaine dose maintaining ≥80% cocaine choice was within one-half log unit of the previously established baseline, a rat could test again; if not, a new stable 3-day baseline was established with the criteria described above.

In the acute treatment experiment, we tested the D2 agonist R-(−)-norpropylapomorphine (NPA; 0.01, 0.032, 0.1, 0.32, 0.56, and 1.0 mg/kg), the D2/D3 partial agonist terguride (0.032, 0.1, 0.32, 0.56, and 1.0 mg/kg), the D2 antagonist L-741,626 [3-[[4-(4-chlorophenyl)-4-hydroxypiperidin-l-yl]methyl-1H-indole] (0.32, 1.0, 3.2, 5.6 mg/kg), the D3 agonist PD-128,907 [(4aR,10bR)-3,4a,4,10b-tetrahydro-4-propyl-2H,5H-[1]benzopyrano-[4,3-b]-1,4-oxazin-9-ol hydrochloride] (0.1, 0.32, 1.0, 3.2, and 5.6 mg/kg), the D3 partial agonist RGH-237 (10, 32, 56 mg/kg), and the D3 antagonist PG01037 [N-[(E)-4-[4-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl]but-2-enyl]-4-pyridin-2-ylbenzamide] (1.0, 3.2, 10, 18, and 32 mg/kg), as well as corresponding vehicles, with doses presented in counterbalanced sequence. All drugs were administered intraperitoneally, 10 minutes before the session.

In the chronic treatment experiment, the D3-preferring agonist PD-128,907 was replaced by the then newly available, more selective D3 agonist PF-592,379 [(5-[(2R,5S)-5-methyl-4-propylmorpholin-2-yl]pyridin-2-amine] (Attkins et al., 2010). We previously reported the effects of acute and chronic administration of the partial D2/D3 agonist aripiprazole using the same assay (Thomsen et al., 2008); therefore, partial agonists were not evaluated as chronic treatment in this investigation. Chronic treatment was achieved with the use of osmotic minipumps (Alzet model 2ML1; Durect, Cupertino, CA) that were implanted subcutaneously under brief isoflurane/oxygen vapor anesthesia and delivered drug continuously at a rate of 10 µl/h. Before implantation, filled minipumps were primed overnight in sterile 0.9% saline at 37–38°C as directed by the manufacturer. On day 1, rats were tested 2 hours after pump implantation, and the pumps were then left in place for 7 days, during which time rats were tested daily as they had been during training. Chronic treatments tested were as follows: NPA (0.00032, 0.001, 0.0032, and 0.01 mg/kg per hour), L-741,626 (0.056, 0.18, 0.32, and 0.56 mg/kg per hour), PF-592,379 (0.56, 1.8, and 3.2 mg/kg per hour), and PG01037 (0.56, 1.8, 3.2, and 5.6 mg/kg per hour). Drug concentrations were adjusted for each rat according to body weight. Treatment was stopped by removing the minipump. We previously verified that 7 days of continuous water administration and presence of the minipumps did not produce any significant changes in choice behavior (Thomsen et al., 2013), and the present data set includes low doses that showed no effect (e.g., NPA, PF-592,379). Therefore, to reduce the number of animal lives needed, we did not include further chronic vehicle groups. Data are reported for the first and last day for brevity, and intervening days typically showed gradual shifts from the acute effects to the chronic effects.

Drugs

Cocaine hydrochloride was provided by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse (Bethesda, MD). PF-592,379 was supplied by P. Butler and was synthesized at Pfizer (Sandwich, UK) as previously described (Attkins et al., 2010). PG01037 dihydrochloride was supplied by A.H. Newman and was synthesized at the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse Medicinal Chemistry Section as previously described (Grundt et al., 2005). RGH-237 was supplied by I. Gyertyán and synthesized at Gedeon Richter (Budapest, Hungary) as previously described (Gyertyán et al., 2007). All other drugs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Cocaine and terguride were dissolved in 0.9% saline. PF-592,379, PD-128,907 hydrochloride, and PG01037 dihydrochloride were dissolved in sterile water. NPA hydrochloride was dissolved in 0.1% ascorbic acid in water, L-741,626 was dissolved in 22% β-cyclodextrin in water, and RGH-237 was dissolved in ethanol and diluted to a final vehicle of 5% ethanol, 47.5% polyethylene glycol, and 47.5% water. Doses reflect the weights of the respective salts.

Data Analysis

The primary dependent variables recorded for each component were 1) number of cocaine injections earned, 2) number of food reinforcers earned, and 3) percent cocaine choice, which was calculated as follows: (number of ratios completed on the cocaine-associated lever ÷ total number of ratios completed) × 100. Total cocaine intake per session (in milligrams per kilogram) and total food reinforcers earned per session were also calculated for each rat. Total response rate (total number of responses ÷ total time responses had scheduled consequences) and response rate on the reinforcer levers alone (calculated using the time these levers were extended) were also recorded but are not reported because they added no significant information on treatment effects, relative to numbers of reinforcers earned. The significance level was set at P < 0.05. No data points collected with patent catheters were excluded (no “outliers”).

For the acute treatments, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the effects of test drugs and cocaine dose on numbers of cocaine and food reinforcers earned per component, with factors being cocaine dose (repeated measures, within subjects) and treatment dose (between subjects). For the chronic experiment, repeated-measures two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the effects of test drugs and cocaine dose on numbers of cocaine and food reinforcers earned per component, with factors being cocaine dose and treatment day (i.e., baseline, first day, after 1 week). Because all doses of a test compound could not always be tested in each rat (within subjects), each chronic drug dose was analyzed separately, so that test versus baseline could be analyzed within subjects. Significant effects on a test day were scrutinized post hoc by Bonferroni post-test versus vehicle/baseline. In both acute and chronic experiments, the effect of cocaine dose was always highly significant and is not reported for each analysis, for brevity.

The percent cocaine choice data were used to calculate A50 values (potency), defined as the dose of cocaine that produced 50% cocaine choice in each rat, and determined by interpolation from two adjacent points spanning 50% cocaine choice. In cases in which cocaine choice was 50%–60% at the lowest dose, extrapolation was used (<4% of all values). In cases in which cocaine choice was >60% at the lowest dose, a value of 0.018 or 0.032 mg/kg per injection was assigned (i.e., quarter-log below the lowest cocaine dose tested, in the acute and chronic experiments, respectively) as a conservative estimate. Because many treatments, especially chronic, produced leftward shifts in the cocaine choice curve, these estimates amounted to 16% of all A50 values. Similarly, in cases in which cocaine choice was <40% at the highest dose, a value of 1.8 mg/kg per injection was assigned (two values, <0.5% of total). Group means and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from the log(10) of individual A50 values but are reported transformed back to linear values for ease of reading. In some cases, responding was completely suppressed in one or more rats for some time/dose points, resulting in missing values for the choice measure, precluding the use of repeated-measures ANOVA for this measure. Instead, the log-transformed A50 values were compared by one-way ANOVA for the acute experiment (factor: dose, between subjects) and two-way ANOVA for the chronic experiment (factors: treatment dose, between subjects; test day, within subjects, using pooled baseline data for all rats tested with any dose of that drug). Significant effects or interactions were examined by one-way ANOVA for each time point. Significant effects were followed by the Dunnett multiple-comparisons test versus vehicle or baseline. Total cocaine intake and total food reinforcers earned per session were analyzed in the same way as A50 values.

Results

Acute Administration

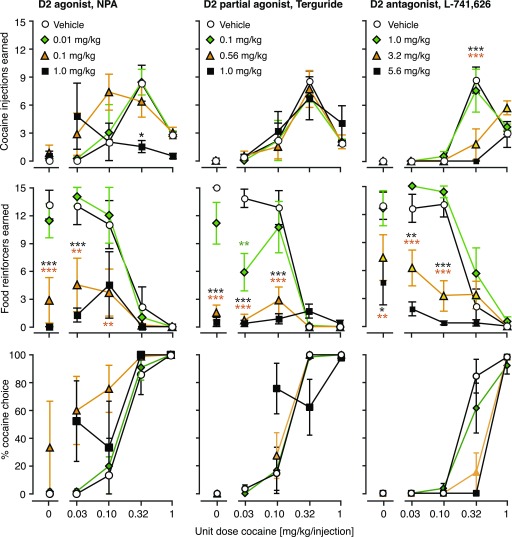

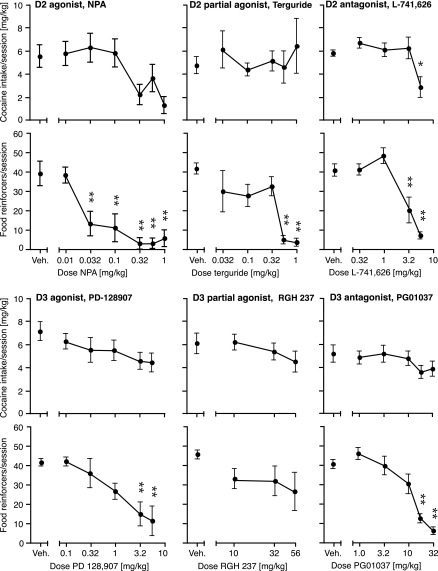

In a first experiment, we tested the acute effects of pretreatment with D2 and D3 agonists, partial agonists, and antagonists on cocaine versus food choice. Figure 1 shows the effects of the D2 agonist NPA, the D2/D3 partial agonist terguride, and the D2 antagonist L-741,626 on numbers of cocaine injections and food reinforcers earned, as well as percent cocaine choice. To avoid crowding, three doses were selected for graphical presentation for each ligand, omitting some low and/or intermediate doses. Likewise, Fig. 2 shows the effects the D3 agonist PD-128,907, the D3 partial agonist RGH-237, and the D3 antagonist PG01037. The corresponding potencies of cocaine to produce 50% cocaine choice (A50 values) are reported in Table 2 (all doses tested). Total cocaine intake per session and total food reinforcers were also calculated and are presented in Fig. 3 for all doses tested.

Fig. 1.

Acute dosing effects of dopamine D2-preferring ligands on concurrent cocaine self-administration and food-reinforced responding as a function of cocaine dose. The abscissae show the unit dose of cocaine (in milligrams per kilogram per injection), and the ordinates show cocaine injections earned (top), food reinforcers earned (center), and percent cocaine choice (bottom), per component. Group sizes are presented in Table 2. Choice data for higher pretreatment doses may have a lower group size because of missing values and are not shown when responding was reduced to the point that percent choice could be calculated for fewer than two rats. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (versus vehicle, Bonferroni post-test after significant ANOVA).

Fig. 2.

Acute dosing effects of dopamine D3-preferring ligands on concurrent cocaine self-administration (top), food-reinforced responding (center), and percent cocaine choice (bottom), as a function of cocaine dose. Group sizes are presented in Table 2. Other details are as in Fig. 1.

TABLE 2.

Changes in cocaine choice A50: acute administration experiment

Values are given as group sizes (n) and group means (95% confidence limits). Doses are given in milligrams per kilogram per injection of cocaine that produced 50% cocaine choices.

| D2 |

D3 |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agonist (NPA) | Partial Agonist (Terguride ) | Antagonist (L-741,626) | Agonist (PD-128,907) | Partial Agonist (RGH-237) | Antagonist (PG01037) | ||||||||||||

| Dose |

n |

Group Mean |

Dose |

n |

Group Mean |

Dose |

n |

Group Mean |

Dose |

n |

Group Mean |

Dose |

n |

Group Mean |

Dose |

n |

Group Mean |

| Vehicle | 7 | 0.18 (0.11–0.29) | Vehicle | 7 | 0.15 (0.11–0.21) | Vehicle | 8 | 0.21 (0.16–0.28) | Vehicle | 11 | 0.15 (0.11–0.19) | Vehicle | 8 | 0.21 (0.15–0.27) | Vehicle | 6 | 0.15 (0.11–0.21) |

| 0.01 | 5 | 0.16 (0.09–0.27) | 0.032 | 4 | 0.12 (0.06–0.26) | 0.32 | 8 | 0.21 (0.15–0.27) | 0.10 | 6 | 0.19 (0.17–0.20) | 10 | 8 | 0.11 (0.07–0.20) | 1.0 | 5 | 0.22 (0.15–0.34) |

| 0.032 | 6 | 0.06 (0.02– 0.18) | 0.10 | 7 | 0.15 (0.10–0.22) | 1.0 | 8 | 0.29 (0.17–0.48) | 0.32 | 7 | 0.29 (0.15–0.57) | 32 | 8 | 0.15 (0.07–0.30) | 3.2 | 8 | 0.14 (0.06–0.33) |

| 0.10 | 6 | 0.03 (0.02–0.08)* | 0.32 | 7 | 0.14 (0.10–0.20) | 3.2 | 9 | 0.44 (0.27–0.71)* | 1.0 | 8 | 0.21 (0.15–0.29) | 56 | 8 | 0.24 (0.17–0.33) | 10 | 8 | 0.14 (0.09–0.20) |

| 0.32 | 7 | 0.03 (0.01–0.06)** | 0.56 | 6 | Not calculated | 5.6 | 6 | Not calculated | 3.2 | 8 | 0.15 (0.05–0.44) | 18 | 6 | Not calculated | |||

| 0.56 | 6 | 0.03 (0.01–0.06)** | 1.0 | 6 | Not calculated | 5.6 | 6 | 0.05 (0.01–0.14)* | 32 | 8 | Not calculated | ||||||

| 1.0 | 4 | 0.04 (0.01–0.17) | |||||||||||||||

Not calculated indicates that responding was suppressed completely in more than one-half of the animals, resulting in missing percent choice values.

P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 versus vehicle (Dunnett multiple-comparisons test after significant ANOVA).

Fig. 3.

Acute effects of dopamine D2-preferring or D3-preferring ligands on total cocaine intake and total food reinforcers per session. The abscissae show the dose of pretreatment drug (in milligrams per kilogram), and the ordinates show total cocaine intake (in milligrams per kilogram per session) (top) or total food reinforcers earned per session (bottom). Group sizes are presented in Table 2. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (Dunnett multiple-comparisons test versus vehicle after significant ANOVA).

The D2 agonist NPA produced dose-dependent leftward shifts in the cocaine reinforcers dose-effect curve, with a significant cocaine dose by NPA dose interaction [F(24,140) = 2.29, P < 0.01]; effects of 0.32, 056, and 1.0 mg/kg reached significance post hoc (P < 0.01; Fig. 1). NPA also produced marked decreases in numbers of food reinforcers earned (NPA dose [F(6,140) = 9.47, P < 0.0001], interaction [F(24,140) = 3.71, P < 0.0001]), with doses from 0.032 mg/kg and up producing significant decreases (P < 0.01). This reallocation of behavior from food toward cocaine resulted in dose-dependent leftward shifts in the cocaine choice curve, with corresponding decreases in A50 values [F(6,32) = 3.92, P < 0.01 (see Table 2 for statistical analysis). NPA’s effects on reinforcers earned resulted in dose-dependent decreases in both total cocaine intake [F(6,35) = 2.94, P < 0.05] and total food reinforcers earned [F(6,35) = 9.49, P < 0.0001], although post hoc comparisons on cocaine intake did not reach significance (Fig. 3).

The D2/D3 partial agonist terguride did not affect cocaine reinforcers earned significantly, up to doses that significantly suppressed food reinforcers (terguride dose [F(5,128) = 9.30, P < 0.0001], interaction [F(20,128) = 5.74, P < 0.0001]), significant at 0.1, 0.56, and 1.0 mg/kg (P < 0.05). Terguride did not affect cocaine choice curves or A50 values consistently or significantly (Table 2). Terguride also failed to affect total cocaine intake significantly but did produce significant decreases in total food reinforcers earned [F(5,31) = 10.7, P < 0.0001] (see Fig. 3).

The D2 antagonist L-741,626 produced effects opposite to NPA on the cocaine reinforcers curve (i.e., dose-dependent rightward shifts) (L-741,626 dose [F(4,136) = 4.74, P < 0.01], interaction [F(16,136) = 5.98, P < 0.0001]). Effects of 3.2 and 5.6 mg/kg reached significance (P < 0.001; Fig. 1). L-741,626 also decreased the numbers of food reinforcers earned (L-741-626 dose [F(4,136) = 12.0, P < 0.0001], interaction [F(16,136) = 5.64, P < 0.0001]), at the same doses that affected cocaine reinforcers, 3.2 and 5.6 mg/kg (P < 0.05). The combined effect on the cocaine choice curve was dose-dependent rightward shifts with corresponding increases in A50 values [F(3,27) = 2.91, P = 0.05], significant at the highest dose (P < 0.05; Table 2). Although intermediate doses of L-741,626 increased the number of high-dose cocaine injections earned, total cocaine intake was only increased marginally; however, the highest dose of L-741,626 decreased cocaine intake [F(4,40) = 5.12, P < 0.01]. The same profile was apparent for total food reinforcers earned [F(4,40) = 18.0, P < 0.0001] (see Fig. 3).

The D3 agonist PD-128,907 produced downward shifts in the cocaine reinforcer curve at intermediate doses and a downward/leftward shift at the highest dose (treatment by cocaine interaction [F(20,160) = 2.32, P < 0.001]). Effects were significant at 0.32, 3.2, and 5.6 mg/kg (P < 0.05; Fig. 2). PD-128,907 also produced marked downward and downward/rightward shifts in the food reinforcers curve (PD-128,907 dose [F(5,160) = 6.69, P = 0.0001], interaction [F(20,160) = 4.79, P < 0.0001]), with significant effects at doses from 0.1 mg/kg and up (P < 0.05). The effect on percent cocaine choice was mixed, with small, nonsignificant rightward shifts at intermediate doses and significant leftward shifts at the higher doses. Thus, PD-128,907 modulated A50 values [F(5,35) = 3.62, P < 0.01], with a significant decrease at 5.6 mg/kg (see Table 2). Effects of PD-128,907 on total cocaine intake were modest and not statistically significant (Fig. 3), whereas effects on food were more pronounced [F(5,41) = 7.02, P < 0001].

The D3 partial agonist RGH-237 and the D3 antagonist PG01037 each produced moderate, nonsignificant leftward shifts in the cocaine reinforcer curve at lower doses and moderate downward shifts at high doses (Fig. 2). However, the effect reached significance only for RGH-237 (interaction [F(12,112) = 1.90, P < 0.05]), the highest dose of 56 mg/kg producing a significant downward shift (P < 0.05). Both ligands dose-dependently decreased the number of food reinforcers earned (RGH-237 by cocaine interaction [F(12,112) = 1.92, P < 0.05]; PG01037 dose [F(5,136) = 17.0, P = 0.0001], interaction [F(20,136) = 5.43, P < 0.0001]). RGH-237 produced significant decreases at 10 and 56 mg/kg (P < 0.05), PG01037, at 18 and 32 mg/kg (P < 0.0001). Neither ligand affected cocaine choice curves or A50 values systematically or significantly (Table 2). Likewise, neither drug affected total cocaine intake significantly, but PG01037 did decrease total food reinforcers earned dose-dependently [F(5,35) = 17.9, P < 0.0001], as shown in Fig. 3.

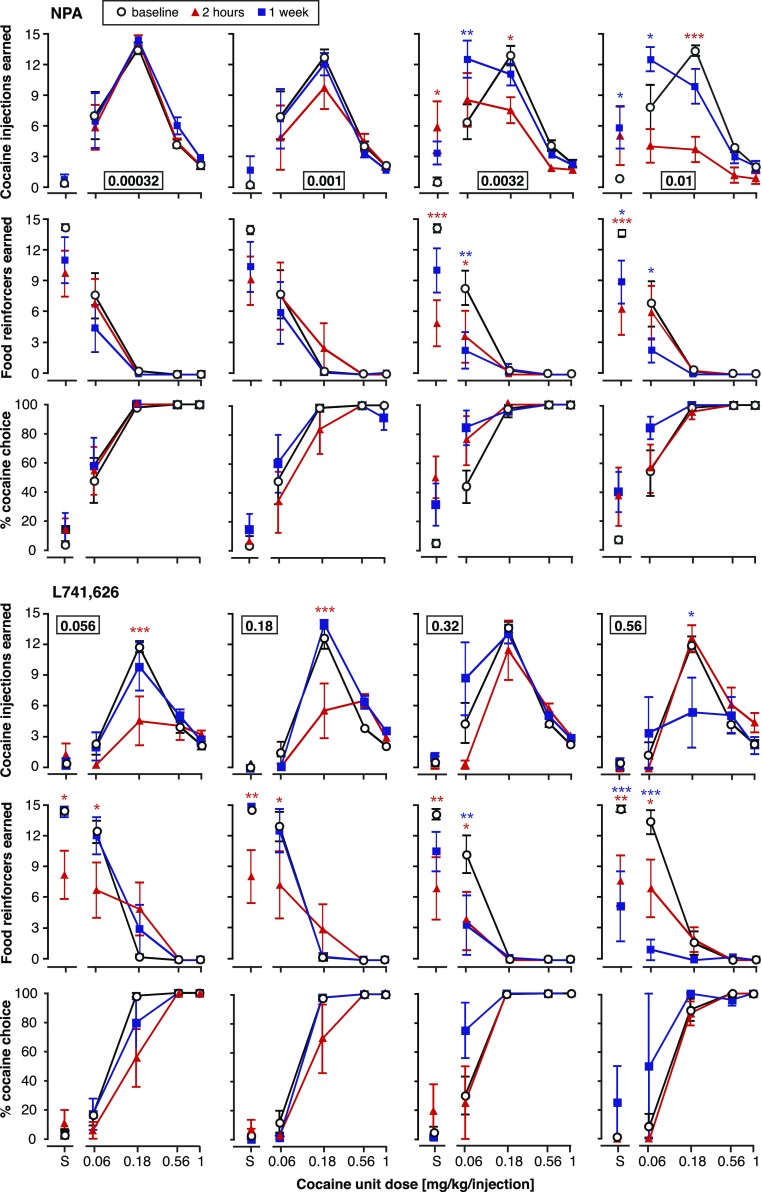

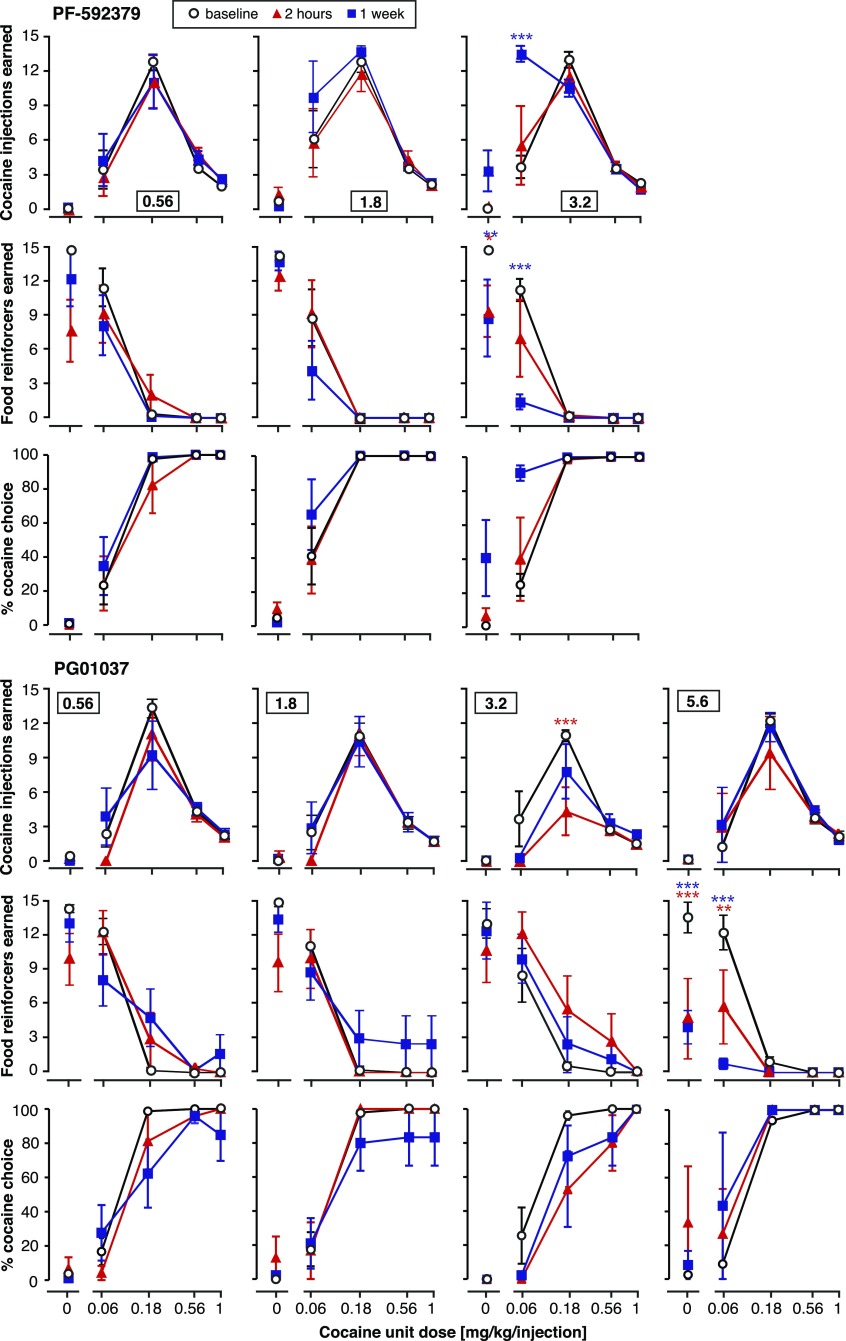

Chronic Administration

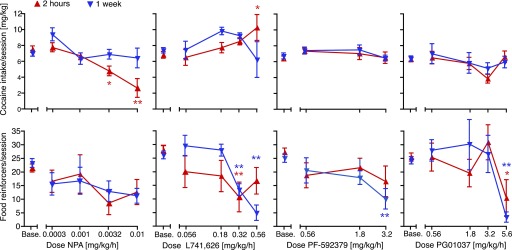

Figure 4 shows the acute and chronic effects of continuous administration of the D2 agonist NPA and the D2 antagonist L-741,626 on numbers of cocaine injections and food reinforcers earned and percent cocaine choice, as a function of treatment dose (one dose per panel “column”). Figure 5 shows the acute and chronic effects of continuous administration of the D3 agonist PF-592,379 and the D3 antagonist PG01037 in the same fashion. Data are reported for the first and last day for brevity, and intervening days typically showed gradual shifts from the acute effects to the chronic effects.

Fig. 4.

Acute versus chronic effects of continuously administered dopamine D2-preferring ligands on concurrent cocaine self-administration and food-reinforced responding. Data from baseline, day 1 (2 hours of administration), and day 7 (1 week of continuous administration) are shown. The abscissae show the unit dose of cocaine (in milligrams per kilogram per injection), and the ordinates show cocaine injections earned (top), food reinforcers earned (center), and percent cocaine choice (bottom), per component. Group sizes are presented in Table 3. Choice data for higher pretreatment doses may be a lower group size because of missing values and are not shown when responding was reduced to the point that percent choice could be calculated for fewer than two rats. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (versus baseline, Bonferroni post-test after significant ANOVA). Red asterisks refer to day 1, and blue asterisks refer to the chronic 1-week test.

Fig. 5.

Acute versus chronic effects of continuously administered dopamine D3-preferring ligands on concurrent cocaine self-administration, food-reinforced responding, and percent cocaine choice. Group sizes are presented in Table 3. Other details are as in Fig. 4.

The corresponding potencies of cocaine to produce 50% cocaine choice (A50 values) are reported in Table 3. Total-session cocaine intake and total food reinforcers were also calculated, and are presented in Fig. 6.

TABLE 3.

Changes in cocaine choice A50: chronic administration experiment

Values are given as group sizes (n) and group means (95% confidence limits). Doses are given in milligrams per kilogram per injection cocaine.

| Ligand | n | Day 1 | 1 Week |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPA | |||

| Baseline | 11 | 0.06 (0.04–0.07) | – |

| 0.00032 | 6 | 0.05 (0.03–0.08) | 0.05 (0.03–0.08) |

| 0.001 | 6 | 0.08 (0.04–0.17) | 0.05 (0.03–0.08) |

| 0.0032 | 6 | 0.04 (0.03–0.06) | 0.04 (0.03–0.06) |

| 0.01 | 6 | 0.05 (0.03–0.08) | 0.03 (0.03–0.04) |

| L-741,626 | |||

| Baseline | 15 | 0.09 (0.07–0.10) | – |

| 0.056 | 6 | 0.19 (0.11–0.32)* | 0.08 (0.06–0.12) |

| 0.18 | 6 | 0.14 (0.08–0.24) | 0.10 (0.10–0.10) |

| 0.32 | 5 | 0.08 (0.04–0.13) | 0.05 (0.03–0.09)** |

| 0.56 | 4 | 0.11 (0.10–0.13) | Not calculated |

| PF-592,379 | |||

| Baseline | 8 | 0.07 (0.06–0.09) | – |

| 0.56 | 6 | 0.10 (0.06–0.16) | 0.07 (0.05–0.11) |

| 1.8 | 6 | 0.07 (0.04–0.10) | 0.05 (0.03–0.08) |

| 3.2 | 5 | 0.06 (0.04–0.11) | 0.03 (0.03–0.03)* |

| PG01037 | |||

| Baseline | 21 | 0.08 (0.06–0.10) | – |

| 0.56 | 6 | 0.12 (0.08–0.19) | 0.11 (0.05–0.24) |

| 1.8 | 6 | 0.08 (0.06–0.12) | 0.13 (0.04–0.39) |

| 3.2 | 6 | 0.20 (0.11–0.38)* | 0.15 (0.07–0.33) |

| 5.6 | 4 | 0.07 (0.03–0.14) | Not calculated |

Not calculated indicates that responding was suppressed completely in more than one-half of the animals, resulting in missing percent choice values.

P < 0.01; **P < 0.05; versus baseline (Dunnett multiple-comparisons test after significant ANOVA).

Fig. 6.

Acute versus chronic effects of continuously administered dopamine D2-preferring or D3-preferring ligands on total cocaine intake and total food reinforcers per session. Data from baseline, day 1 (2 hours of administration), and day 7 (1 week of continuous administration) are shown. The abscissae show the dose of pretreatment drug (in milligrams per kilogram), and the ordinates show total cocaine intake (in milligrams per kilogram per session) (top) or total food reinforcers earned per session (bottom). Group sizes are presented in Table 3. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (Dunnett multiple-comparisons test versus baseline after significant ANOVA).

The D2 agonist NPA produced leftward and downward shifts in the cocaine self-administration curve, with marked tolerance after a week of treatment. Cocaine reinforcers were affected significantly at the two highest doses, as a function of treatment day: at 0.0032 mg/kg per hour (cocaine dose by treatment interaction [F(8,50) = 4.05, P < 0.001]) and at 0.01 mg/kg per hour (treatment [F(2,50) = 13.4, P < 0.0001], interaction [F(8,50) = 3.87, P < 0.01]). In the same dose range, NPA significantly decreased the number of food reinforcers earned, but this effect was not generally diminished after chronic administration: at 0.0032 mg/kg per hour (treatment [F(2,50) = 8.10, P < 0.001], interaction [F(8,50) = 3.87, P < 0.01]), and at 0.01 mg/kg per hour (main [F(2,50) = 4.32, P < 0.05], interaction [F(8,50) = 2.92, P < 0.001]). Percent cocaine choice was shifted to the left, with corresponding decreases in A50 values (treatment day [F(1,30) = 5.20, P < 0.05]), although the effect did not reach statistical significance on specific days (Table 3). The shift in the cocaine dose-effect curve toward the lower cocaine doses resulted in a significant decrease in total cocaine intake on day 1, but this effect was abolished after a week of treatment (see Fig. 6; effect of treatment dose, treatment time, and interaction all P ≤ 0.001). Total food intake was decreased as a function of NPA dose [F(4,60) = 3.04, P < 0.05], with no effect of treatment time or dose by time interaction (i.e., no significant tolerance).

Conversely, the D2 antagonist L-741,626 produced rightward shifts in the cocaine curve, which showed a high degree of tolerance up until the highest dose (0.56 mg/kg per hour), which produced a downward shift only as chronic treatment, suggesting drug accumulation or perhaps sensitization (see Fig. 4 for statistical details). L-741,626 also decreased the number of food reinforcers earned, and this effect showed tolerance only at the two lowest doses. In fact, exacerbation of the effect upon chronic administration was apparent at the higher doses. L-741,626 also affected cocaine choice, as measured by A50 values, differentially as acute and chronic treatment (two-way ANOVA, effect of L-741,626 dose [F(3,28) = 4.42, P < 0.05], treatment day [F(1,28) = 12.1, P < 0.01], and dose by time interaction [F(3,28) = 3.46, P < 0.05]). Specifically, choice curves were shifted to the right, and A50 values increased, on day 1 [F(4,31) = 4.09, P < 0.01], with the converse effect after 1 week of treatment [F(3,28) = 3.12, P < 0.05] (see Table 3). As shown in Fig. 6, the rightward shift in the cocaine curve (i.e., shift toward higher cocaine doses) resulted in an increase in total cocaine intake acutely, and this effect dissipated after chronic administration (L-741,626 dose by time interaction [F(4,31) = 3.55, P < 0.05]). Total food intake was decreased both acutely and chronically (see Fig. 6; effect of treatment dose [F(4,31) = 8.41, P = 0.0001], dose by time interaction [F(4,31) = 3.68, P < 0.05]).

The D3 agonist PF-592,379 had no effect on numbers of cocaine injections earned acutely, up to doses that decreased food reinforcers. However, the highest dose (3.2 mg/kg per hour) produced a leftward or upward shift in the ascending limb of the cocaine dose-effect curve after a week of continuous administration (see Fig. 5; treatment [F(2,40) = 5.89, P < 0.01], interaction [F(8,40) = 5.91, P < 0.0001]). This shift was not accompanied by a decrease in the high-dose cocaine injections (descending limb). A trend toward the same effect was apparent at the intermediate dose of 1.8 mg/kg per hour. Food reinforcers similarly were only affected significantly at the highest dose, which produced a decrease both acutely and chronically (treatment [F(2,40) = 8.79, P < 0.001], interaction [F(8,40) = 3.79, P < 0.01]). Thus, after chronic treatment with the D3 agonist, behavior was reallocated from food toward cocaine taking, and percent cocaine choice was shifted leftward, with decreased A50 values (two-way ANOVA effect of treatment day [F(1,21) = 5.78, P < 0.05] and dose [F(3,21) = 1.22, P < 0.05]), significant after chronic administration only [F(13,21) = 5.94, P < 0.01], Table 3). Despite this shift, seen only at the lowest unit dose of cocaine, total cocaine intake was not significantly modified by PF-592,379, acutely or chronically (Fig. 6). Food intake was suppressed moderately, and as much or more so by chronic administration relative to acute administration (effect of PF-592,379 dose [F(3,21) = 4.43, P < 0.05]).

The D3 antagonist PG01037 had no effect on numbers of cocaine injections earned at most doses, acutely or chronically but did produce a downward shift in the cocaine curve at the intermediate-high dose of 3.2 mg/kg per hour, with partial tolerance after 1 week of treatment (treatment day [F(2,50) = 4.86, P < 0.05], interaction [F(8,50) = 2.45, P < 0.05]). This decrease in cocaine choice was accompanied by a moderate and nonsignificant increase in food reinforcers. However, the highest dose (5.6 mg/kg per hour PG01037) decreased food-reinforced behavior significantly without affecting cocaine, and this effect on food remained as pronounced or more pronounced after 1 week (see Fig. 5; treatment [F(2,30) = 17.4, P = 0.0001], interaction [F(8,30) = 5.99, P < 0.0001]). Consequently, percent cocaine choice was shifted moderately to the right with the treatment dose of 3.2 mg/kg per hour, as supported by a significant increase in A50 values (effect of dose PG01037 [F(4,37) = 2.85, P < 0.05]; see Table 3). The doses of 0.56 and 1.8 mg/kg per hour doses produced only modest, nonsignificant rightward shifts in the cocaine choice curve, indicating a narrow dose window or variable effect of PG01037. Although 3.2 mg/kg per hour appeared to be the most effective dose across rats, some individual variability was observed, some rats indicated a decrease in cocaine self-administration at lower doses. The shift produced by 3.2 mg/kg per hour was greatly attenuated after chronic treatment and was only statistically significant on day 1 [F(4,37) = 4.58, P < 0.01] (see Table 3). Regardless of treatment time, PG01037 treatment failed to significantly alter total cocaine intake per session, whereas food intake was decreased at the highest dose of PG01037 (effect of dose [F(4,38) = 3.62, P < 0.05] (Fig. 6).

Discussion

The dopamine D3 receptor continues to be of interest as a potential target for cocaine addiction medications. D3 receptor antagonists have generally failed to decrease the direct reinforcing effects of cocaine but can decrease conditioned responding (for review, see Sokoloff and Le Foll, 2017). However, the evaluation of D3 receptor ligands has mostly concentrated on acute dosing. Preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated that chronic administration of dopamine receptor ligands, and dopamine transporter ligands, can affect cocaine intake and other addiction-related effects of cocaine very differently from their acute effects. Nonselective dopamine receptor antagonists (e.g., flupenthixol), D2 receptor antagonists (e.g., risperidone), and D1/D5 receptor antagonists (SCH 39166 [(6aS-trans)-11-chloro-6,6a,7,8,9,13b-hexahydro-7-methyl-5H-benzo[d]naphth[2,1-b]azepin-12-ol] or SCH 23390 [(R)-(+)-7-chloro-8-hydroxy-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-3-benzazepine]) have been evaluated preclinically and clinically. All showed antagonism of cocaine’s effects, including reduced self-administration, as acute dosing but were ineffective or increased cocaine intake and/or subjective effects of cocaine as chronic treatment, with good agreement between human studies (Romach et al., 1999; Grabowski et al., 2000; Haney et al., 2001; Nann-Vernotica et al., 2001; Loebl et al., 2008; Kishi et al., 2013) and laboratory animal studies (Kleven and Woolverton, 1990; Negus et al., 1996; Negus, 2003; Hutsell et al., 2016). Similar effects were obtained with the D2/D3 partial agonist aripiprazole (Stoops et al., 2007; Bergman, 2008; Thomsen et al., 2008; Haney et al., 2011; Lofwall et al., 2014).

Conversely to dopamine receptor antagonists, agonist medication strategies using chronic administration of monoamine releasers such as d-amphetamine, methamphetamine, phenmetrazine, or their prodrugs decreased cocaine taking and cocaine choice in humans (Grabowski et al., 2001; Shearer et al., 2003; Mooney et al., 2009; Greenwald et al., 2010; Pérez-Mañá et al., 2011; Nuijten et al., 2016), monkeys (Negus, 2003; Negus and Mello, 2003; Czoty et al., 2010, 2011; Banks et al., 2011, 2013, 2015b; Hutsell et al., 2016), and rats (Chiodo et al., 2008; Thomsen et al., 2013). Acutely, amphetamines mimic and increase behavioral and subjective effects of cocaine and increase cocaine intake/choice (Barrett et al., 2004; Thomsen et al., 2013). Thus, both agonist and antagonist dopaminergic manipulations show either profound tolerance or indeed a complete reversal of effect direction between acute and chronic administration. Therefore, it is becoming clear that potential cocaine addiction medication strategies must be evaluated using chronic or subchronic dosing conditions to better predict effects of clinical use, in which medications will most likely be administered as chronic treatment to promote abstinence.

Although there is mounting evidence to support the efficacy of agonist medications with psychostimulant properties such as d-amphetamine (but not of direct dopamine receptor agonists), the acceptance and U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of those agonist medications is faced with serious challenges based on concerns about their addictive potential and safety (Pérez-Mañá et al., 2011; Minozzi et al., 2015; Negus and Henningfield, 2015). Here, we used a cocaine versus food choice assay in rats to compare acute and chronic dosing effects of dopamine D2 and D3 receptor agonists and antagonists. A primary objective of these studies was to evaluate D3 receptor agonists and antagonists as (sub)chronic treatments and to test the hypothesis that chronic administration may decrease cocaine choice and/or intake, despite the general lack of an acute effect of D3 receptor–selective ligands on cocaine self-administration. D2 receptor agonists and antagonists were also tested using acute and chronic treatment regimens to allow for direct comparisons.

Table 4 presents a summary of treatment effects in this investigation, as well as previous results obtained with aripiprazole and d-amphetamine for comparison. Acute dosing with D2 receptor ligands produced results in agreement with previous single-reinforcer experiments (Caine et al., 2000; Haile and Kosten, 2001; Barrett et al., 2004; Rowlett et al., 2007): the agonist NPA shifted the cocaine self-administration dose-effect curve to the left, the antagonist L-741,626 shifted the curve to the right, and the partial agonist had little effect. All three compounds also suppressed food-reinforced responding, which is also consistent with single-reinforcer studies (Barrett et al., 2004). Acute effects of the D3 receptor ligands differed from this typical agonist/antagonist profile. A flattening of the cocaine self-administration curve was observed with the highest dose of the agonist PD-128,907 and with lower doses of both the partial agonist RGH-237 and of the antagonist PG01037. The variable and nonsignificant increase in self-administration of a low dose of cocaine most likely reflects modulation of the conditioned reinforcing effects of the cocaine-associated cues, rather than an increase in the reinforcing effect of cocaine or direct reinforcing effects of the D3 receptor ligand, based on previous studies failing to demonstrate reinforcing effects of D3 receptor–selective ligands, as well as the fact that cocaine choices were not increased in the no-cocaine component in our investigation (Beardsley et al., 2001; Collins and Woods, 2009; Collins et al., 2012). Lower doses of PD-128,907 and higher doses of RGH-237 or PG01037 produced downward shifts of similar magnitude in cocaine and food choices, suggesting nonselective suppression of behavior rather than modulation of cocaine’s reinforcing effects specifically. This is consistent with a general lack of effect of D3 receptor ligands in single-reinforcer cocaine self-administration studies in monkeys and rodents at doses that did not also cause general suppression of behavior (Beardsley et al., 2001; Gál and Gyertyán, 2003; Achat-Mendes et al., 2009; Caine et al., 2012). It is also possible that both stimulation and blockade of D3 receptors can mediate a moderating effect on reward pathways, at least in rats. Although it is speculative, this notion of D3 systems as performing a “dampening,” modulatory function is consistent with both PD-128,907 and PG01037 decreasing intracranial self-stimulation acutely in rats (Lazenka et al., 2016).

TABLE 4.

Summary of present and previous findings

Effects refer to total cocaine intake per session, total food reinforcers per session, and percent cocaine choice, respectively.

| Classification | Ligand | Acute Effects |

Chronic Effects |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cocaine Intake | Food Intake | Cocaine Choice | Cocaine Intake | Food Intake | Cocaine Choice | ||

| D2 agonist | NPA | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | – | ↓ | (↑) |

| D2/D3 partial agonist | Terguride | – | ↓ | – | |||

| D2 antagonist | L741,626 | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | – | ↓ | ↑ |

| D3 agonist | PD-128,907 | – | ↓ | ↑ | |||

| D3 agonist | PF-592,379 | – | ↓ | ↑ | |||

| D3 partial agonist | RGH-237 | – | (↓) | – | |||

| D3 antagonist | PG01037 | – | ↓ | – or ↓ | – | ↓ | – |

| D2/D3 partial agonist | Aripiprazole medium dosea | (↓) | (↓) | ↓ | – | ↓ | – |

| D2/D3 partial agonist | Aripiprazole high dosea | (↑) | (↓) | – | (↑) | ↓ | (↑) |

| Monoamine reuptake inhibitor | d-Amphetamineb | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | (↓) | ↑ | ↓ |

↓, decrease; ↑, increase; –, no change. Arrows in parentheses indicate trends that did not reach statistical significance.

Chronic administration of a D2 receptor agonist (NPA) or antagonist (L741,626) also produced effects in agreement with previous studies in monkeys. For example, in agreement with our study, chronic 5-day treatment with NPA in rhesus monkeys initially shifted the cocaine self-administration curve to the left and down and decreased cocaine intake, but tolerance developed after 5-day administration, at least in subordinate monkeys (Czoty and Nader, 2013). NPA also produced some cocaine-lever choice during the first component, both acutely and after continuous administration, when no cocaine was available. This is consistent with acute effects of D2-family receptor agonists in rats and monkeys under similar conditions, as well as with NPA functioning as a positive reinforcer in monkeys (Weissenborn et al., 1996; Barrett et al., 2004; Gasior et al., 2004; Rowlett et al., 2007). Consistent with our findings using L741,626, chronic L741,626 or eticlopride suppressed food- and cocaine-reinforced responding nonselectively in monkeys (Claytor et al., 2006; Achat-Mendes et al., 2010). Despite an initial decrease in cocaine choice with one dose of L741,626 in this study, both NPA and L741,626, if anything, increased percent cocaine choice after continuous administration and neither decreased total cocaine intake.

Chronic administration of a D3 receptor agonist (PF-592,379) or antagonist (PG01037) also produced effects distinct from the D2 ligands. Acutely, PF-592,379 moderately decreased food choices with no effect on cocaine, but chronic PF-592,379 increased self-administration of low doses of cocaine while further decreasing food choices. This undesirable profile is in agreement with the effects of a D3-preferring partial agonist in monkeys, and of 15-day treatment with pramipexole, which strongly increased positive subjective effects of cocaine in humans (Achat-Mendes et al., 2009; Newton et al., 2015). Unlike NPA, PF-592,379 produced little responding on the cocaine-associated lever during the first component, consistent with the notion that D3-preferring agonists can enhance the conditioned reinforcing effects of cocaine-associated cues but maintain little responding per se (Collins and Woods, 2009; Collins et al., 2012). Consistent with the acute dosing data and with previous single-reinforcer studies in monkeys, PG01037 had minimal effects on cocaine self-administration up to doses that also suppressed food-reinforced responding (Achat-Mendes et al., 2010). However, consistent with choice studies in monkeys, 3.2 mg/kg PG01037 produced a significant downward shift in the cocaine curve, with tolerance after continuous administration (Czoty and Nader, 2015; John et al., 2015a). A higher dose suppressed responding nonselectively. Although effects on food did not reach statistical significance, it is perhaps worth noting that PG01037 was the only treatment that increased food intake after chronic administration in our studies, whereas L741,626 mostly decreased food-reinforced responding. This is consistent with recent studies using dopamine receptor knockout mice, which indicated that D2, rather D3 or D4, receptors mediate reinforcing effects of food (Soto et al., 2016).

In terms of total cocaine intake and overall food-reinforced behavior, none of the treatment regimens offered promising medication-like profiles in this assay. Up to doses that disrupted food-reinforced behavior, no compound decreased cocaine intake significantly. Similarly, the 5-HT1A agonist and D3/D4 antagonist buspirone reduced cocaine self-administration in monkeys acutely, but it increased cocaine choice after 5-day treatment and failed to improve time to relapse or cocaine taking in clinical trials (Bergman et al., 2013; Winhusen et al., 2014; John et al., 2015b; Bolin et al., 2016; but see Mello et al., 2013). In fact, buspirone increased cocaine use in women (Winhusen et al., 2014). One possible reason for the variable and typically modest effects of PG01037 and other D3 receptor antagonists may be highly variable sensitivity between individuals, which was observed here and in monkeys (Czoty and Nader, 2015; John et al., 2015a). For all compounds tested, the effects of high doses on food-reinforced behavior persisted or increased during chronic administration. Although blood drug levels were not measured, it is likely that some or all ligands were tested up to doses that produced moderate drug accumulation, although the development of sensitization rather than tolerance is also possible. Drug accumulation is most likely to have occurred for L-741,626 and PF-592,379 based on pilot pharmacokinetic studies (PF-592,379) and the observation that rats typically required at least 3 days to re-establish baseline levels of responding after minipump removal with those ligands. Regardless of mechanism, the dissociation of chronic effects on cocaine and food indicates that distinct pharmacological mechanisms underlie effects on cocaine and nondrug reinforcement. Unfortunately, this profile may suggest that dose-limiting, undesirable effects of dopamine receptor ligands in humans may also be resistant to tolerance.

In conclusion, the cocaine versus food choice procedure in rats produced data consistent with studies in monkeys and human subjects. Furthermore, these findings underline the importance of testing chronic or subchronic administration of compounds of interest at the preclinical stage. In particular, both the D2 antagonist L-741,626 and the D3 antagonist PG01037 decreased cocaine choice at some dose as acute treatment, but after 1 week, neither drug significantly altered cocaine choice. Here, access to cocaine was not suspended during treatments, and it is possible that effects of chronic D3 receptor antagonism could be larger if tested under suspended access conditions (Czoty and Nader, 2013). However, the difficulty in establishing abstinence in cocaine-dependent patients means that candidate medications should also be evaluated under conditions of continued cocaine access during treatment (Moran et al., 2017). Other factors that may influence the effectiveness of dopamine receptor ligands include feeding conditions, age, sex, and social status (Czoty and Nader, 2013, 2015; Baladi et al., 2014; Collins et al., 2014; Jupp et al., 2016), and our data may not generalize to smaller/leaner subjects, females, and so forth. It would be of interest to examine cocaine self-administration behaviors of rats living in social groups, where access to social interactions, mating, and so forth would arguably function as competing reinforcers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Amy Newman and Peter Grundt (National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse, Intramural Research Program) for providing PG01037 for this study. They also thank Drs. István Gyertyán and Krisztina Gál and Richter Gedeon Ltd. for providing RGH-237 for this study. Finally, they thank John Miller, Dana Angood, and Justin Hamilton for expert technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- FR

fixed ratio

- L-741,626

3-[[4-(4-chlorophenyl)-4-hydroxypiperidin-l-yl]methyl-1H-indol

- NPA

R-(−)-norpropylapomorphine

- PD-128,907

(4aR,10bR)-3,4a,4,10b-tetrahydro-4-propyl-2H,5H-[1]benzopyrano-[4,3-b]-1,4-oxazin-9-ol hydrochloride

- PF-592,379

5-[(2R,5S)-5-methyl-4-propylmorpholin-2-yl]pyridin-2-amine

- PG01037

N-[(E)-4-[4-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl]but-2-enyl]-4-pyridin-2-ylbenzamide

- RGH-237

N-{4-[4-(3-aminocarbonyl-phenyl)-piperazin-1-yl]-butyl}-4-bromo-benzamide

- SCH 23390

(R)-(+)-7-chloro-8-hydroxy-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-3-benzazepine

- SCH 39166

(6aS-trans)-11-chloro-6,6a,7,8,9,13b-hexahydro-7-methyl-5H-benzo[d]naphth[2,1-b]azepin-12-ol]

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Barrett, Negus, Caine.

Conducted experiments: Barrett, Caine.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Butler.

Performed data analysis: Thomsen.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Thomsen, Barrett, Butler, Negus, Caine.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse [Grants R00DA027825 (to M.T.), T32DA07252 (to A.C.B.), R01DA026946 (to S.S.N.), and R29DA12142 (to S.B.C.)]. M.T. was also supported by funds from Psychiatric Centre Copenhagen while completing portions of the manuscript.

References

- Achat-Mendes C, Grundt P, Cao J, Platt DM, Newman AH, Spealman RD. (2010) Dopamine D3 and D2 receptor mechanisms in the abuse-related behavioral effects of cocaine: studies with preferential antagonists in squirrel monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 334:556–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achat-Mendes C, Platt DM, Newman AH, Spealman RD. (2009) The dopamine D3 receptor partial agonist CJB 090 inhibits the discriminative stimulus but not the reinforcing or priming effects of cocaine in squirrel monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 206:73–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attkins N, Betts A, Hepworth D, Heatherington AC. (2010) Pharmacokinetics and elucidation of the rates and routes of N-glucuronidation of PF-592379, an oral dopamine 3 agonist in rat, dog, and human. Xenobiotica 40:730–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baladi MG, Newman AH, France CP. (2014) Feeding condition and the relative contribution of different dopamine receptor subtypes to the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 231:581–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Blough BE, Fennell TR, Snyder RW, Negus SS. (2013) Effects of phendimetrazine treatment on cocaine vs food choice and extended-access cocaine consumption in rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 38:2698–2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Blough BE, Negus SS. (2011) Effects of monoamine releasers with varying selectivity for releasing dopamine/norepinephrine versus serotonin on choice between cocaine and food in rhesus monkeys. Behav Pharmacol 22:824–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Hutsell BA, Blough BE, Poklis JL, Negus SS. (2015b) Preclinical assessment of lisdexamfetamine as an agonist medication candidate for cocaine addiction: effects in rhesus monkeys trained to discriminate cocaine or to self-administer cocaine in a cocaine versus food choice procedure. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 18:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Hutsell BA, Schwienteck KL, Negus SS. (2015a) Use of preclinical drug vs. food choice procedures to evaluate candidate medications for cocaine addiction. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry 2:136–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Negus SS. (2017) Insights from preclinical choice models on treating drug addiction. Trends Pharmacol Sci 38:181–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AC, Miller JR, Dohrmann JM, Caine SB. (2004) Effects of dopamine indirect agonists and selective D1-like and D2-like agonists and antagonists on cocaine self-administration and food maintained responding in rats. Neuropharmacology 47 (Suppl 1):256–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley PM, Sokoloff P, Balster RL, Schwartz JC. (2001) The D3R partial agonist, BP 897, attenuates the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine and D-amphetamine and is not self-administered. Behav Pharmacol 12:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman J. (2008) Medications for stimulant abuse: agonist-based strategies and preclinical evaluation of the mixed-action D-sub-2 partial agonist aripiprazole (Abilify). Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 16:475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman J, Kamien JB, Spealman RD. (1990) Antagonism of cocaine self-administration by selective dopamine D(1) and D(2) antagonists. Behav Pharmacol 1:355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman J, Roof RA, Furman CA, Conroy JL, Mello NK, Sibley DR, Skolnick P. (2013) Modification of cocaine self-administration by buspirone (Buspar®): potential involvement of D3 and D4 dopamine receptors. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 16:445–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boileau I, Payer D, Houle S, Behzadi A, Rusjan PM, Tong J, Wilkins D, Selby P, George TP, Zack M, et al. (2012) Higher binding of the dopamine D3 receptor-preferring ligand [11C]-(+)-propyl-hexahydro-naphtho-oxazin in methamphetamine polydrug users: a positron emission tomography study. J Neurosci 32:1353–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolin BL, Lile JA, Marks KR, Beckmann JS, Rush CR, Stoops WW. (2016) Buspirone reduces sexual risk-taking intent but not cocaine self-administration. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 24:162–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine SB, Negus SS, Mello NK. (2000) Effects of dopamine D(1-like) and D(2-like) agonists on cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys: rapid assessment of cocaine dose-effect functions. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 148:41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine SB, Negus SS, Mello NK, Bergman J. (1999) Effects of dopamine D(1-like) and D(2-like) agonists in rats that self-administer cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 291:353–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine SB, Negus SS, Mello NK, Patel S, Bristow L, Kulagowski J, Vallone D, Saiardi A, Borrelli E. (2002) Role of dopamine D2-like receptors in cocaine self-administration: studies with D2 receptor mutant mice and novel D2 receptor antagonists. J Neurosci 22:2977–2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine SB, Thomsen M, Barrett AC, Collins GT, Grundt P, Newman AH, Butler P, Xu M. (2012) Cocaine self-administration in dopamine D3 receptor knockout mice. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 20:352–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiodo KA, Läck CM, Roberts DC. (2008) Cocaine self-administration reinforced on a progressive ratio schedule decreases with continuous D-amphetamine treatment in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 200:465–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claytor R, Lile JA, Nader MA. (2006) The effects of eticlopride and the selective D3-antagonist PNU 99194-A on food- and cocaine-maintained responding in rhesus monkeys. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 83:456–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Butler P, Wayman C, Ratcliffe S, Gupta P, Oberhofer G, Caine SB. (2012) Lack of abuse potential in a highly selective dopamine D3 agonist, PF-592,379, in drug self-administration and drug discrimination in rats. Behav Pharmacol 23:280–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Jackson JA, Koek W, France CP. (2014) Effects of dopamine D(2)-like receptor agonists in mice trained to discriminate cocaine from saline: influence of feeding condition. Eur J Pharmacol 729:123–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Truong YN, Levant B, Chen J, Wang S, Woods JH. (2011) Behavioral sensitization to cocaine in rats: evidence for temporal differences in dopamine D3 and D2 receptor sensitivity. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 215:609–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Woods JH. (2009) Influence of conditioned reinforcement on the response-maintaining effects of quinpirole in rats. Behav Pharmacol 20:492–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Ashworth JB, Foltin RW, Johanson CE, Zacny JP, Walsh SL. (2008) The role of human drug self-administration procedures in the development of medications. Drug Alcohol Depend 96:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czoty PW, Gould RW, Martelle JL, Nader MA. (2011) Prolonged attenuation of the reinforcing strength of cocaine by chronic d-amphetamine in rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 36:539–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czoty PW, Martelle JL, Nader MA. (2010) Effects of chronic d-amphetamine administration on the reinforcing strength of cocaine in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 209:375–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czoty PW, Nader MA. (2013) Effects of dopamine D2/D3 receptor ligands on food-cocaine choice in socially housed male cynomolgus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 344:329–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czoty PW, Nader MA. (2015) Effects of oral and intravenous administration of buspirone on food-cocaine choice in socially housed male cynomolgus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 40:1072–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czoty PW, Stoops WW, Rush CR. (2016) Evaluation of the “pipeline” for development of medications for cocaine use disorder: a review of translational preclinical, human laboratory, and clinical trial research. Pharmacol Rev 68:533–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin RW, Haney M, Rubin E, Reed SC, Vadhan N, Balter R, Evans SM. (2015) Development of translational preclinical models in substance abuse: effects of cocaine administration on cocaine choice in humans and non-human primates. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 134:12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman SB, Patel S, Marwood R, Emms F, Seabrook GR, Knowles MR, McAllister G. (1994) Expression and pharmacological characterization of the human D3 dopamine receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 268:417–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gál K, Gyertyán I. (2003) Targeting the dopamine D3 receptor cannot influence continuous reinforcement cocaine self-administration in rats. Brain Res Bull 61:595–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasior M, Paronis CA, Bergman J. (2004) Modification by dopaminergic drugs of choice behavior under concurrent schedules of intravenous saline and food delivery in monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 308:249–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski J, Rhoades H, Schmitz J, Stotts A, Daruzska LA, Creson D, Moeller FG. (2001) Dextroamphetamine for cocaine-dependence treatment: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 21:522–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski J, Rhoades H, Silverman P, Schmitz JM, Stotts A, Creson D, Bailey R. (2000) Risperidone for the treatment of cocaine dependence: randomized, double-blind trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 20:305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald MK, Lundahl LH, Steinmiller CL. (2010) Sustained release d-amphetamine reduces cocaine but not ‘speedball’-seeking in buprenorphine-maintained volunteers: a test of dual-agonist pharmacotherapy for cocaine/heroin polydrug abusers. Neuropsychopharmacology 35:2624–2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundt P, Carlson EE, Cao J, Bennett CJ, McElveen E, Taylor M, Luedtke RR, Newman AH. (2005) Novel heterocyclic trans olefin analogues of N-4-[4-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl]butylarylcarboxamides as selective probes with high affinity for the dopamine D3 receptor. J Med Chem 48:839–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyertyán I, Kiss B, Gál K, Laszlovszky I, Horváth A, Gémesi LI, Sághy K, Pásztor G, Zájer M, Kapás M, et al. (2007) Effects of RGH-237 [N-4-[4-(3-aminocarbonyl-phenyl)-piperazin-1-yl]-butyl-4-bromo-benzamide], an orally active, selective dopamine D(3) receptor partial agonist in animal models of cocaine abuse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 320:1268–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haile CN, Kosten TA. (2001) Differential effects of D1- and D2-like compounds on cocaine self-administration in Lewis and Fischer 344 inbred rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 299:509–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Rubin E, Foltin RW. (2011) Aripiprazole maintenance increases smoked cocaine self-administration in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 216:379–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Spealman R. (2008) Controversies in translational research: drug self-administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 199:403–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Ward AS, Foltin RW, Fischman MW. (2001) Effects of ecopipam, a selective dopamine D1 antagonist, on smoked cocaine self-administration by humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 155:330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder CA, Newman AH. (2010) Current perspectives on selective dopamine D(3) receptor antagonists as pharmacotherapeutics for addictions and related disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1187:4–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutsell BA, Negus SS, Banks ML. (2016) Effects of 21-day d-amphetamine and risperidone treatment on cocaine vs food choice and extended-access cocaine intake in male rhesus monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend 168:36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John WS, Banala AK, Newman AH, Nader MA. (2015b) Effects of buspirone and the dopamine D3 receptor compound PG619 on cocaine and methamphetamine self-administration in rhesus monkeys using a food-drug choice paradigm. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 232:1279–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John WS, Newman AH, Nader MA. (2015a) Differential effects of the dopamine D3 receptor antagonist PG01037 on cocaine and methamphetamine self-administration in rhesus monkeys. Neuropharmacology 92:34–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AR, Banks ML, Blough BE, Lile JA, Nicholson KL, Negus SS. (2016) Development of a translational model to screen medications for cocaine use disorder I: choice between cocaine and food in rhesus monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend 165:103–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jupp B, Murray JE, Jordan ER, Xia J, Fluharty M, Shrestha S, Robbins TW, Dalley JW. (2016) Social dominance in rats: effects on cocaine self-administration, novelty reactivity and dopamine receptor binding and content in the striatum. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 233:579–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck TM, John WS, Czoty PW, Nader MA, Newman AH. (2015) Identifying medication targets for psychostimulant addiction: unraveling the dopamine D3 receptor hypothesis. J Med Chem 58:5361–5380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi T, Matsuda Y, Iwata N, Correll CU. (2013) Antipsychotics for cocaine or psychostimulant dependence: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry 74:e1169–e1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleven MS, Woolverton WL. (1990) Effects of continuous infusions of SCH 23390 on cocaine- or food-maintained behavior in rhesus monkeys. Behav Pharmacol 1:365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulagowski JJ, Broughton HB, Curtis NR, Mawer IM, Ridgill MP, Baker R, Emms F, Freedman SB, Marwood R, Patel S, et al. (1996) 3-((4-(4-Chlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl)-methyl)-1H-pyrrolo-2,3-b-pyridine: an antagonist with high affinity and selectivity for the human dopamine D4 receptor. J Med Chem 39:1941–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazenka MF, Legakis LP, Negus SS. (2016) Opposing effects of dopamine D1- and D2-like agonists on intracranial self-stimulation in male rats. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 24:193–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Foll B, Francès H, Diaz J, Schwartz JC, Sokoloff P. (2002) Role of the dopamine D3 receptor in reactivity to cocaine-associated cues in mice. Eur J Neurosci 15:2016–2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lile JA, Stoops WW, Rush CR, Negus SS, Glaser PE, Hatton KW, Hays LR. (2016) Development of a translational model to screen medications for cocaine use disorder II: Choice between intravenous cocaine and money in humans. Drug Alcohol Depend 165:111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loebl T, Angarita GA, Pachas GN, Huang KL, Lee SH, Nino J, Logvinenko T, Culhane MA, Evins AE. (2008) A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of long-acting risperidone in cocaine-dependent men. J Clin Psychiatry 69:480–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofwall MR, Nuzzo PA, Campbell C, Walsh SL. (2014) Aripiprazole effects on self-administration and pharmacodynamics of intravenous cocaine and cigarette smoking in humans. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 22:238–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason CW, Hassan HE, Kim KP, Cao J, Eddington ND, Newman AH, Voulalas PJ. (2010) Characterization of the transport, metabolism, and pharmacokinetics of the dopamine D3 receptor-selective fluorenyl- and 2-pyridylphenyl amides developed for treatment of psychostimulant abuse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 333:854–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador-Woodruff JH, Little KY, Damask SP, Watson SJ. (1995) Effects of cocaine on D3 and D4 receptor expression in the human striatum. Biol Psychiatry 38:263–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Fivel PA, Kohut SJ, Bergman J. (2013) Effects of chronic buspirone treatment on cocaine self-administration. Neuropsychopharmacology 38:455–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ, Gobert A, Newman-Tancredi A, Lejeune F, Cussac D, Rivet JM, Audinot V, Dubuffet T, Lavielle G. (2000) S33084, a novel, potent, selective, and competitive antagonist at dopamine D(3)-receptors: I. Receptorial, electrophysiological and neurochemical profile compared with GR218,231 and L741,626. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 293:1048–1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ, Maiofiss L, Cussac D, Audinot V, Boutin JA, Newman-Tancredi A. (2002) Differential actions of antiparkinson agents at multiple classes of monoaminergic receptor. I. A multivariate analysis of the binding profiles of 14 drugs at 21 native and cloned human receptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 303:791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]