Abstract

The potential importance of depending on others during adolescence in order to establish independence in young adulthood was examined across adolescence to emerging adulthood. Participants included 184 teens (46% male; 42% non-White), their mothers, best friends, and romantic partners, assessed at ages 13–14, 18, 21–22, and 25. Path analyses showed that associations were both partner and age specific: markers of independence were predicted by participants’ efforts to seek support from mothers at age 13, best friends at 18, and romantic partners at 21. Importantly, analyses controlled for support seeking from these partners at other ages, as well as for other potentially confounding variables including attachment security, scholastic/job competence, and physical attractiveness over time. Moreover, analyses suggested the transfer of support seeking behavior from mothers to best friends to romantic partners over time based on support given by the previous partner at an earlier age.

Keywords: Functional independence, Family relationships, Peer Relationships, Friendships, Romantic Relationships

One of the most challenging and emotionally fraught tasks of adolescence is learning to establish a balance between dependence and independence within social relationships (Allen, Hauser, Bell, & O’Connor, 1994; Grotevant & Cooper, 1985; Hill & Holmbeck, 1986). During adolescence, teens typically seek to gain independence from parents (although this is often replaced by dependency on peers), while nevertheless aiming to maintain a positive parent-teen relationship (Steinberg & Silverberg, 1986). Similar tensions then arise in peer relationships over time and manifest as pressures to avoid an appearance of dependency on peers, particularly with respect to peer influence and pressure (Berndt, 1979). Yet as central as strivings for independence may be to the adolescent, the ability to tolerate and even seek a certain degree of appropriate dependence in the short term may be crucial to actually achieving long-term independence (Allen & Land, 1999).

Little is known regarding the conditions under which dependence in parent and peer relationships during adolescence may be appropriate and helpful for ultimately achieving markers of independence in adulthood. This study examined the potential benefits of one form of volitional relational dependence – actively asking for help from others – as a predictor of future capacity for independent functioning in adulthood. Ultimately, this study sought to examine whether seeking support from specific others at developmentally salient times during adolescence, and thus assuming a position of greater dependence on others, might in turn predict greater independence in adulthood.

In late adolescence and early adulthood, attaining independence in domains such as education, work, financial management, residence, and tasks of daily life is critical to achieving full adult status and becoming self-sufficient (Arnett, 2001; Luyckx, Schwartz, Goossens, & Pollock, 2008). Attaining independence in these domains has been linked to benefits of both personal and societal significance, from greater subjective well being to increased compliance with societal norms (Arnett, 2001; Kins & Beyers, 2010). Attaining independence from the family of origin also contributes to positive relational outcomes such as better family relationships and increased chances of establishing a romantic relationship (Seiffge-Krenke, 2010; White & Rogers, 1997). Although adolescents are known for being fiercely protective of their independence and eager to establish their self-sufficiency, maintaining close relationships with a degree of dependency during adolescence may actually confer benefits for promoting greater independence in adulthood. Attachment theory posits that in a secure close relationship, the ability to establish healthy dependence with an attachment figure facilitates exploration of independence in the larger world (Bowlby, 1969/1982). An attachment figure serves as a source of support, help, guidance, and comfort during times of need, and knowledge of an attachment figure’s availability to provide such care when needed facilitates a willingness to learn and grow apart from the attachment figure. This sequence of using others to seek help when needed, and to explore, learn, and grow apart from them when it is not, is thought to be a catalyst for healthy adult functioning (Bowlby, 1988). Indeed, there is evidence that having an attachment figure that is able to meet dependency needs facilitates exploration and independence both in childhood and adulthood, with parents and romantic partners typically serving as such attachment figures, respectively, during these stages (Bowlby, 1988; Feeney, 2007).

Though much attention has been given to the significance of attachment relationships during childhood, and, to a lesser extent, in adulthood, the ways in which different types of attachment relationships might become more or less salient facilitators of healthy adult independence during adolescence is less well understood. Adolescence is marked by the developmentally appropriate emergence of increased interest in the peer group relative to parents, first with regard to interest in friendships and later with increased interest in romantic relationships. Thus, this developmental period is ideal for examining, a) how relying on others for help might contribute to future independence, and, b) how relying on different types of relationship partners for help at specific points in development might be particularly important for predicting such independence. Focal theory suggests that positive adaptation during adolescence is facilitated by focusing attention on different relationships at different ages, in part so that the adolescents’ psychological resources for negotiating relationships are not depleted by attempts to manage too many issues or relationships at one time (Coleman, 1974/1989). Coleman (1974) found empirical support for the focal model by finding that attitudes toward specific relationships (e.g., parents, friends, and romantic partners) peaked at different times during adolescence. Additional evidence has supported the idea of a changing focus and influence of different relationship partners during adolescence. For example, though parents tend to fulfill attachment needs throughout adolescence and young adulthood, the positive effects of parental support appear to be strongest in early adolescence and weaken across time into early adulthood (Helsen, Vollebergh, & Meeus, 2000; Markiewicz, Lawford, Doyle, & Haggart, 2006; Rosenthal & Kobak, 2010). This weakening of parental support occurs in the context of teens’ strivings to achieve independence from parents as they begin to turn increasingly to peers for support during mid- to late adolescence (Allen & Land, 1999; Buhrmester & Furman, 1987; Markiewicz et al., 2006; Steinberg & Silk, 2002; von Salisch, 2001). Although no research has yet examined the functional implications of actually requesting support from peers during adolescence, having peers who provide greater support has been associated with greater subjective well being, goal progress, and school success for individuals in later adolescence and early adulthood (Koestner, Powers, Carbonneau, Milyavskaya, & Chua, 2012; Rabaglietti & Ciairano, 2008; Ratelle, Simard, & Guay, 2013). However, during later adolescence and early adulthood, romantic partners become more salient as attachment figures as compared to friends for many young adults (Fraley & Davis, 1997; Markiewicz et al., 2006). Such increased reliance on romantic partners suggests that turning to these partners during this stage of development might be more useful for promoting independence than to turning to friends or parents. Indeed, there is strong evidence that young adults whose romantic partners indicate a willingness and availability to provide them with support both report and exhibit greater future independent functioning (Feeney, 2007). Another study of young adult dating couples found that specifically seeking support was associated with support received (i.e. instrumental support that was sought was provided), suggesting that actively seeking support within such relationships may be beneficial for getting one’s needs met and fostering positive growth (Collins & Feeney, 2000). However, no study to date has examined the potential differential importance of seeking support from parents, peers, and romantic partners across adolescence for achieving of markers of independence in early adulthood.

As previously mentioned, there is evidence that attachment behaviors are transferred over time from parents, to peers, to romantic partners (Fraley & Davis, 1997; Markiewicz et al., 2006), though the means by which these transfers occur are unclear. As development progresses, cumulative continuity theory suggests that learning to depend on parents in healthy ways in early adolescence might be predictive of future adaptive outcomes, primarily to the extent that this dependence predicts the development of similar capacities to rely appropriately upon friends and romantic partners later in development (Roberts & Caspi, 2003). Adolescents who depend appropriately upon parents for support might be most likely to later experience long-term benefits from learning to do so with peers and romantic partners. It is reasonable to suspect that such an appropriate reliance on parents in early adolescence might be predicated on parents’ willingness and ability to meet needs when called upon to do so; that is, to effectively provide the support they are asked for. Although this premise has never been examined across the adolescent to adulthood transition, evidence within late adolescence provides indirect support for the notion that support from parents may contribute to support processes within relationships with peers and romantic partners (Bokhorst, Sumter, & Westenberg, 2010; Inge Seiffge-Krenke, 2003). It is unknown, however, whether effective support provided by peers might similarly promote a future willingness to appropriately seek support from romantic partners. Furthermore, although the presence of supportive parents, peers, and romantic partners is obviously a benefit, previous research has generally failed to examine whether adolescents actively seeking such support (as opposed to simply finding themselves in supportive relationships) is a critical part of this process.

Present Study and Hypotheses

The present study used longitudinal, multi-method data obtained across a twelve-year span to examine the contribution of teens’ support seeking behavior in key relationships to markers of long-term independent functioning in young adulthood. Moreover, it sought to examine the contributions of support seeking to predictions of independence relative to other potentially confounding constructs assessed concurrently during early and late adolescence and early adulthood – attachment security, scholastic/job competence, and physical attractiveness. These constructs were included because of their documented associations with both receiving support from others and characteristics of independent functioning in young adulthood. For example, positive attachment with parents and peers has been linked to positive educational persistence and attainment and job competence (Fass & Tubman, 2002), as well as positive social competence, social support, and ego-resiliency in stressful contexts (Kobak & Sceery, 1988; Laible, 2007). Scholastic performance during adolescence predicts a greater likelihood of attaining of a high school diploma as well as postsecondary education, and cognitive ability longitudinally predicts learning, skill acquisition, task competence, and income level (Carver, 1990; Judge, Hurst, & Simon, 2009; Gottfredson, 1997; Ng et al., 2005). Physical attractiveness has been linked to greater educational support and attainment and positive job-related outcomes, including occupational success and earnings (Hosoda, Stone-Romero, & Coats, 2003; Judge et al., 2009; Langlois et al., 2000; Umberson & Hughes, 1987). All three constructs have also been associated with increased attention and social and instrumental support from others, which may foster continued achievement and success in domains of adult independence (Ceci & Williams, 1997; Kobak & Sceery; Langlois, 2000). Including these controls helps strengthen the possibility that any links found between support seeking behavior and markers of future independence are not simply due to these characteristics.

This study thus hypothesized that more persistent and direct efforts to ask for support from mothers, best friends, and romantic partners at developmentally salient points would predict markers of teens’ greater independence in young adulthood. Specifically, support-seeking behavior with mothers was hypothesized to be most developmentally salient – and thus most predictive of outcomes – in early adolescence, whereas support seeking from best friends and romantic partners was expected to become more salient (and predictive) in late adolescence (for friends) and emerging adulthood (for romantic partners). It was hypothesized that support seeking in these contexts and at these times would predict markers of independence even after controlling for attachment security, scholastic/job competence, and physical attractiveness assessed concurrently with support seeking at each time point.

Finally, it was hypothesized that support given by mothers in early adolescence would predict relative increases in teens’ future support seeking from friends in late adolescence, and that support given by friends in late adolescence would in turn predict teens’ relative increases in future support seeking from romantic partners in emerging adulthood after accounting for continuities in relationship-specific support seeking behavior, supporting the idea of the transfer of support processes across relationships during these stages of development.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants included 184 youth (86 male, 98 female) and their mothers, best friends, and romantic partners, followed longitudinally from age 13 to age 25. Participants were initially recruited from the seventh and eighth grades of a public middle school drawing from suburban and urban populations in the Southeastern United States. Students were recruited via an initial mailing to all parents of students in the school that gave them the opportunity to opt out of further contact with the study (N = 298). Only 2% of parents opted out of such contact. Families were subsequently contacted by phone, and 63% agreed to participate and had an adolescent who was able to participate in the study with a parent and best friend. Siblings of target adolescents and students already participating as a target adolescent’s best friend were ineligible for participation.

The final study sample of 184 youth was racially/ethnically and socio-economically diverse: 107 adolescents identified themselves as Caucasian, 53 as African-American, 2 as Hispanic/Latino, 2 as Asian American, 1 as American Indian, 15 as mixed ethnicity, and 4 as part of an “other” minority group. Parents of target adolescents reported a median family income in the $40,000–$59,999 range (M = 43,618, SD = 22,420). The sample appeared comparable to the overall population of the school from which it was drawn in terms of racial/ethnic composition (42% non-white in sample vs. ~ 40% non-white in school) and socio-economic status (mean household income = $43,618 in sample vs. $48,000 in the community at large).

Adolescents were first assessed at age 13 (M = 13.36, SD = .65) in 1999 by questionnaire as well as in an observed supportive interaction task with their mothers (n = 168) and with their self-nominated best, same-gendered friend (n = 179). Adolescents reported knowing their best friend for an average of about 4 years (M = 4.15, SD = 3.20) at this time. Adolescents returned at age 14 (M= 14.25, SD = .77) to complete the Adult Attachment Interview. At age 18 (M = 18.30, SD = .99), teens were again interviewed and participated in an observed supportive interaction task with their mothers (n = 103) and best friends (n = 161). Adolescents reported knowing their best friend for an average of 7 ½ years (M = 7.47, SD = 4.86) at this time. At age 18 teens were also invited to nominate a romantic partner of at least 2 months to be included in the study (N = 97) with whom they were also invited to participate in an observed supportive interaction task (n = 61). Although same-gender relationships were not excluded from the study, no same-gender relationships were reported at this time. Teens reported dating their romantic partner for an average of a little over 1 year (M = 14.65 months, SD = 13.59) at this time. At age 21, teens were again interviewed and invited to nominate a romantic partner of at least 2 months to be included in the study (N = 121), with whom they were invited to participate in an observed supportive interaction task (n = 88). Adolescents reported dating their romantic partner for an average nearly 2 years (M = 21.78 months, SD = 20.16) at this time. Participants and their close friends returned at age 22 (M = 22.80, SD = .95) to complete measures related to job/professional experience. At age 25, target participants and their mothers were re-assessed.

Adolescents provided informed assent, and their parents provided informed consent before each assessment (until participants were old enough to provide informed consent). The same assent/consent procedures were used for mothers, best friends, and romantic partners. Assessments took place in private offices within a university academic building for about 1–2 hours. Confidentiality was assured to all study participants and adolescents were told that their parents, friends, and romantic partners would not be informed of any of the answers they provided (respondents were assessed individually). Participants’ data were protected by a Confidentiality Certificate issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which protected information from subpoena by federal, state, and local courts. Transportation and childcare were provided if necessary. Adolescents, mothers, best friends, and romantic partners were all paid for their participation ($15/person/assessment initially, increasing gradually with age to $75/person/assessment later in early adulthood).

Attrition Analyses

Attrition analyses examined response bias based on missing data at the various follow-up time points of the study. These analyses first examined response bias based on the presence vs. absence of observational data at a subsequent time point. Comparisons of data collected at age 13 for participants with and without best friend observational data at age 18 indicated no differences on any data collected at age 13–14. Comparisons of data collected at ages 13 and 18 for participants with and without romantic partner observational data at age 21 indicated no differences on any variables at age 13–14 or 18. Thus, there were no differences for youth on study variables based on whether or not they were able to bring in a friend or romantic partner to participate with them in the study.

Analyses next examined response bias for youth with vs. without outcome data at age 25. Comparisons of data collected at ages 13–14, 18, and 21–22 for participants with and without mother-report data at age 25 indicated that participants with mother-report data at age 25 had greater levels of attachment security at age 13, greater observed calls for support to their best friends at age 18, were rated as more physically attractive at ages 18 and 21, and more likely to be female. Comparisons of data collected at ages 13–14, 18, and 21–22 for participants with and without self-report data at age 25 indicated that participants with self-report data at age 25 were rated as more physically attractive at age 13 and more likely to be female.

To best address any potential biases due to attrition in longitudinal analyses, full information maximum likelihood (FIML) methods were used with analyses, including all variables that were linked to missing data (i.e. where data were not missing completely at random). Because these procedures have been found to yield the least biased estimates when all available data are used for longitudinal analyses (vs. listwise deletion of missing data; Arbuckle, 1996), the entire sample of 184 participants was utilized for analyses evaluating calls for support to their mothers and best friends. A substantial proportion of the entire sample (n = 133) reported having engaged in a romantic relationship of at least two months by age 21; this sample of 133 participants was utilized for analyses evaluating calls for support to romantic partners. These samples thus provide the best possible estimates of variances and covariances in measures of interest and were least likely to be biased by missing data.

Measures

Support processes

Adolescents participated in an observed Supportive Behavior Task (SBT) with their mothers (8-minute task at ages 13 and 18), best friends (6-minute task at ages 13, 18, and 21), and romantic partners (6-minute task at ages 18 and 21), during which they asked their partner for help with a “problem they were having that they could use some advice or support about.” Thus, participants were free to discuss any problem of their choosing. These interactions were coded using the Supportive Behavior Coding System (Allen et al., 2001) for the constructs listed below. There were 15 coders of support processes used across the time of the study (13 females, 2 males; 13 White, 1 African-American, 1 Hispanic).

Support seeking

Support seeking behaviors reflect teens’ calls for instrumental and emotional support from their partner. Behaviors reflecting calls for instrumental support included statements of a need for instrumental advice or assistance, including a request for information that is helpful to the teen for meeting a specific goal (other than just to know the answer). Behaviors reflecting calls for emotional support included expressing strong emotion or distress about an emotionally-laden topic, self-disclosure of emotional information, and behaviors suggesting emotional relevance (i.e. sad expression or tone, signs of anxiety or nervousness) which express emotions in a way that pull for empathy or comfort. Higher scores on the support seeking scale are based on greater persistence of the call for support throughout the interaction and how important getting help appears to be to the teen. Support seeking behavior was coded on a 0 to 4 continuum with half-point intervals, with higher scores indicating more persistent and direct calls for support. Interrater reliability was calculated using intraclass correlation coefficients. ICCs for support seeking with mom (age 13) = .82, (age 18) = .72; with best friend (age 13) = .85, (age 18) = .73, (age 21) = .83; with romantic partner (age 18) = .90, age (21) = .80.

Support given

Support given by teens’ mothers at age 13 and best friends at age 18 was also assessed. Support given reflects instrumental and emotional support given from teens’ partners. Behaviors indicative of instrumental support given include recognizing that a problem exists, offering plans for how to solve the problem, keeping the conversation directed toward a solution, and making a commitment to help find a solution to the problem. Emotional support given reflects behaviors such as validation, sympathy, recognizing feelings, attempts to emotionally draw the seeker out and understand the emotions, and making a commitment to be emotionally available. Higher scores, rated on a 0–4 continuum with half-points intervals, are based on the supporter’s persistence in finding a solution and seeking information about the problem in order to “tune in” their response to the seeker’s needs. Interrater reliability was calculated using intraclass correlation coefficients. ICCs for support given from mom (age 13) = .90; from best friend (age 18) = .73.

Attachment Security

At age 14, the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI), a structured interview, and parallel coding system, the Q-sort (George, Kaplan, & Main, 1996; Kobak, Cole, Ferenz-Gillies, Fleming, & Gamble, 1993) were used to analyze individuals’ descriptions of their childhood relationships with their parents in both abstract terms and with specific supporting memories. The interview consisted of 18 questions and lasted an average of one hour. Slight adaptations to the adult version were made to make the questions more natural and easily understood by an adolescent population (Ward & Carlson, 1995). Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed for coding.

The AAI Q-sort (Kobak et al., 1993) was designed to parallel the AAI classification system (Main & Goldwyn, 1998) but yield continuous measures of qualities of attachment organization. For this system, two raters read a transcript and provided a Q-sort description by assigning 100 items into nine categories ranging from most to least characteristic of the interview, using a forced distribution. All interviews were blindly rated by at least two raters with extensive training in both the Q-sort and the AAI classification system. To establish validity, these Q-sorts were then compared with dimensional prototypes for secure strategies, preoccupied strategies, and dismissing strategies (see Kobak et al., 1993). The correlation of the 100 items of an individual’s Q-sort with each dimension (ranging on an absolute scale from – 1.00 to 1.00) was then taken as the participant’s scale score for that dimension. The Spearman-Brown reliability for the final security scale score was .82.

Although the system was designed to yield continuous scores, Q-sort scales have previously been reduced using an algorithm into classifications that largely agree with the three-category ratings from the AAI Classification System (Allen, Moore, Kuperminc, & Bell, 1998; Kobak et al., 1993). This system was designed to yield continuous measures of qualities of attachment organization rather than to replicate classifications from the Main and Goldwyn (1998) system. Prior work has compared the scores obtained within this lab to a subsample (N = 76) of adolescent AAIs that were classified by an independent coder with well-established reliability in classifying AAIs. We did this by converting the Q-sort scales described above into classifications using an algorithm described by Kobak et al. (1993). Using this approach, we obtained an 84% match for security versus insecurity between the Q-sort method and the classification method (K = .68). Prior research in adolescent samples has also indicated that security is highly stable over a two-year period (i.e., r = .61) (Allen, McElhaney, Kuperminc, & Jodl, 2004).

Because the AAI was not repeated in later study waves, attachment security at ages 18 and 21 was assessed with The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (Armsden & Greenberg, 1989). This assessment measures perceptions of adolescents’ relationships with their mother, father, and close friend in terms of how well they serve as sources of psychological security. The measure consisted of 25 five-point Likert-scale items assessing the degree of trust, communication, and alienation (reverse-scored) in each relationship. An overall attachment security scale was created by combining the total attachment scores for participants’ mother and father (participant reports) and closest friend (friend report). These overall attachment security scales demonstrated excellent reliability (α = .96 at age 18; α = .95 at age 21).

Scholastic/Job Competence

Participants’ best friends rated participants’ scholastic competence at age 13 using the Self-Perception Profile for Children, 8 to 13 (Harter, 1985). This 4-item measure assesses perceived cognitive competence as applied to schoolwork (α = .73). Best friends were asked to choose between two statements and then subsequently decide if the chosen statement was “sort of true for my friend” or “really true for my friend”. A sample item for scholastic competence at age 13 is: “Some kids feel like they are very good at their school work BUT Other kids worry about whether they can do the school work assigned to them.” At age 18, participants’ best friends rated participants’ combined scholastic and job competence using the Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents, 14 to 19 (Harter, 1988). In addition to assessing competence as applied to schoolwork, this 4-item measure also assesses the extent to which the participant feels that they have job skills, are ready to do well at part-time jobs, and is doing well at any job they may have (α = .73). A sample item related specifically to job competency is: “Some teenagers feel they do have enough skills to do well at a job BUT Other teenagers feel that they don’t have enough skills to do well at a job.” Because the Self-Perception Profile was not repeated in emerging adulthood, job competence was assessed at the most proximally available age to other emerging adult measures, age 22, using the combined positive work performance and positive academic/professional ambition scales from the Young Adult Adjustment Scale (Capaldi, King, & Wilson, 1992); the 14-item scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = .90). Sample items include: “Knows exactly what s/he wants to do in school or work” and “How much would you say that s/he works hard?” For all scales, higher scores indicate greater positive scholastic/job competency.

Physical Attractiveness

Physical attractiveness in adolescence and emerging adulthood was coded using a naïve rater strategy (Kopera, Maier, & Johnson, 1971; Patzer, 1985) at ages 13, 18, and 21. In a naïve coding system the construct is coded giving no specific instruction regarding the construct, but instead asking coders to apply their lay understanding of the meaning of the given construct/term. In this case, lay coders were told to rate attractiveness based on their own understanding of the common meaning of the term ‘physical attractiveness’. The coding team (n = 8) was ethnically diverse and included both males and females. Coding was based on observation of video recordings of adolescents during the first 30 seconds of an interaction task with peers (with sound off, and image of the peer obscured). Naïve coding systems attain reliability by compositing ratings from multiple raters, and in this case yielded highly reliable ratings at ages 13 (ICC = .85), 18 (ICC = .87) and 21 (ICC = .90). Higher scores indicate greater perceived attractiveness.

Family Income

Household family income was assessed at age 13. Mothers were asked to report their total annual household income before taxes. Possible answers included (1) Under $5,000, (2) $5,000–$9,999, (3) $10,000–$14,999, (4) $15,000–$19,999, (5) $20,000–$29,999, (6) $30,000–$39,999, (7) $40,000–$59,999, (8) $60,000 or more.

Functional independence

At age 25, mothers answered a 7-item questionnaire related to their perceptions of their young adults’ independence. Items for this scale were taken from the Young Adult Adjustment Scale by Capaldi, King, & Wilson, 1992. Sample items included “Is a responsible adult,” “Is able to take care of himself/herself,” “Is financially independent,” “Is happy,” and, “Is successful.” Internal consistency for this scale was excellent (Cronbach’s α =.92). Higher scores indicate greater functional independence.

Education level

At age 25, young adults reported about their highest level of completed education on a continuum of options: (1) 8th grade or less, (2) some high school, (3) general equivalency diploma (GED), (4) high school graduate, (5) associate’s degree, (6) bachelor’s degree, (7) some graduate work, (8) post-college degree, with higher scores indicating a higher level of completed education.

Employment status

At age 25, young adults reported whether they were currently employed (part- or full-time): 1 = yes, 0 = no.

Lives at Home with Parents

At age 25, young adults’ mothers reported whether participants lived with them (as opposed to just visiting) at any time during the previous year; 1 = lived with parents, 0 = did not live with parents.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Means and standard deviations for all substantive variables are presented in Table 1. Initial analyses examined the role of gender and family income in early adolescence on the primary measures examined in the study. Given initial findings suggesting relations of gender and family income to other variables in the study, gender and family income were included as covariates in all analyses. For descriptive purposes, Table 2 presents simple correlations among primary constructs examined in the study. These analyses show numerous significant correlations between calls for support with hypothesized developmentally salient partners and future markers of functional independence, as well as many significant correlations between potential confounding variables and markers of independence. These analyses also show that many of the indices of independence in adulthood were only modestly correlated with one another, suggesting that they provide relatively independent assessments of markers of independent functioning in young adulthood.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations with gender and family income for primary study variables

| Mean | SD | Gender | Income | N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Call to Mother (13) | 3.58 | 1.76 | .03 | .15* | 167 |

| 2. | Call to Friend (18) | 3.74 | 1.10 | −.01 | .05 | 161 |

| 3. | Call to Romantic Partner (21) | 3.73 | 1.40 | .17* | .04 | 77 |

| 4. | Functional Independence (25) | 36.83 | 7.40 | −.06 | .05 | 130 |

| 5. | Education Level (25) | 6 | – | −.04 | .22** | 158 |

| 6. | Currently Employed (25) | 76% | – | −.01 | .38*** | 161 |

| 7. | Lives at Home with Parent(s) (25) | 32% | – | .05 | .61*** | 134 |

| 8. | Attachment Security (14) | .25 | .42 | .02 | .06 | 174 |

| 9. | Scholastic Competence (13) | 12.37 | 2.79 | −.01 | .20** | 177 |

| 10. | Physical Attractiveness (13) | 3.68 | .76 | −.17** | .12 | 169 |

| 11. | Attachment Security (18) | 101.41 | 14.00 | .28*** | −.04 | 162 |

| 12. | Job Competence (18) | 12.65 | 2.44 | .06 | .07 | 109 |

| 13. | Physical Attractiveness (18) | 3.57 | .88 | .02 | .14 | 143 |

| 14. | Attachment Security (21) | 102.54 | 12.78 | .09 | .00 | 165 |

| 15. | Job Competence (22) | 24.93 | 5.49 | .23** | .09 | 105 |

| 16. | Physical Attractiveness (21) | 3.54 | .93 | .04 | .14 | 122 |

| 17. | Income | 43,618 | 22,420 | −.11 | – | 181 |

| 18. | Gender | 47% male | – | – | – | 184 |

Table 2.

Intercorrelations Between Constructs.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Call to Mother (13) | – | ||||||||||||||

| 2. | Call to Friend (18) | .19** | ||||||||||||||

| 3. | Call to Romantic Partner (21) | .26*** | .63*** | |||||||||||||

| 4. | Functional Independence (25) | .32*** | .34*** | .32*** | ||||||||||||

| 5. | Education Level (25) | .26*** | .19** | .18** | .54*** | |||||||||||

| 6. | Currently Employed (25) | .22** | .25*** | −.01 | .25** | .26*** | ||||||||||

| 7. | Lives at Home with Parent(s) (25) | −.24*** | −.13 | −.36*** | −.40*** | −.26*** | −.23** | |||||||||

| 8. | Attachment Security (14) | .33*** | .10 | .10 | .33*** | .31*** | .18** | −.26 | ||||||||

| 9. | Scholastic Competence (13) | .17* | .15* | −.05 | .28*** | .18** | .31*** | −.20** | .14 | |||||||

| 10. | Physical Attractiveness (13) | .14 | −.17* | .16 | .14 | .10 | .04 | −.31*** | −.01 | .12 | ||||||

| 11. | Attachment Security (18) | .08 | .09 | .17* | .19** | .12 | −.09 | −.05 | .21** | .01 | .00 | – | ||||

| 12. | Job Competence (18) | .23** | .06 | .20** | .23** | .25*** | .03 | −.13 | .14 | .14 | −.03 | .28*** | ||||

| 13. | Physical Attractiveness (18) | .23** | .14 | .10 | .23** | .22** | .23** | −.36*** | .34*** | .13 | .54*** | .15* | .10 | |||

| 14. | Attachment Security (21) | .01 | .17* | .14 | .18** | .01 | −.03 | −.04 | .21** | −.04 | .00 | .61*** | .29*** | −.01 | ||

| 15. | Job Competence (22) | .14 | .19* | .03 | .30*** | .36*** | −.05 | −.07 | −.01 | .04 | −.15* | .10 | .25*** | .13 | .15 | |

| 16. | Physical Attractiveness (21 | .31*** | .16* | .39*** | .31*** | .30*** | .15* | −.22** | .19** | .03 | .49*** | .06 | .06 | .73*** | −.01 | .41*** |

Note.

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001.

Primary Analyses

Hypotheses regarding relationships between calls for support during adolescence and markers of independent functioning in young adulthood were tested using path analysis in Mplus (v. 7.0) with FIML handling of missing data and Monte Carlo Integration (for dichotomous outcomes). Three different path models were initially estimated. The first path model tested associations between outcome markers of independent functioning and calls for support to mothers at age 13, a second model tested associations between outcomes and calls for support to best friends at age 18, and a third model tested associations between outcomes and calls for support to romantic partners at age 21. All models included gender, household income, attachment security, scholastic/job competence, and physical attractiveness. Attachment security, scholastic/job competence, and physical attractiveness were assessed in each model at the same developmental stage as participants’ call for support from a given partner (i.e. potential confounding variables were assessed and included at age 13–14 when examining predictions from calls for support to mothers at age 13, etc.). A final, full path model including all variables mentioned above was also tested in order to test the relative contributions of calls for support to each specific partner for predicting markers of independent functioning.

The hypothesis regarding the potential transfer of calls for support to mothers to best friends to romantic partners was examined using a hierarchical regression approach. Analyses were designed to assess the extent to which future levels of calls for support with a specific partner could be predicted by support given by an earlier developmentally-salient partner after controlling for initial levels of participants’ calls for support. The selected analytic approach of predicting the future level of a variable, while accounting for predictions from initial levels, yields one marker of relative change in that variable, for example, by allowing assessment of predictors of future calls for support while accounting for initial levels (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2013). In addition, covarying baseline levels of future behaviors eliminates the spurious effect whereby observed predictions are simply a result of cross-sectional associations among variables that are stable over time.

Support seeking as a developmentally salient predictor of independent functioning from early adolescence to early adulthood

Tables 3–5 show significant pathways from teens’ calls for support to their mothers, best friends, and romantic partners to markers of independence in young adulthood. More direct and persistent calls for support from teens to their mothers at age 13 predicted teens being rated as more functionally independent and having achieved a higher level of education at age 25. Teens’ calls for support to their best friends at age 18 predicted participants being rated as more functionally independent and as being employed full-time at age 25. Finally, teens’ calls for support to their romantic partners at age 21 predicted participants being rated as more functionally independent and less likely to live with their parents at age 25.

Table 3.

Predicting Markers of Functional Independence at age 25 from Calls for Support to Mother during Early Adolescence.

| Functional Independence (25) | Education Level (25) | Employment Status (25) | Lives at Home with Parent(s) (25) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| β final | 95% CI | R2 | β final | 95% CI | R2 | β final | 95% CI | R2 | β final | 95% CI | R2 | |

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Gender | −.05 | −.20–.11 | .02 | −.12–.16 | −.24* | −.44 –−.04 | −.05 | −.25 –.15 | ||||

| Income | .10 | −.06–.27 | .30*** | .17–.44 | .07 | −.12–.26 | −.17 | −.37–.03 | ||||

| Potential Confounds | ||||||||||||

| Attachment Security (14) | .23** | .06–.40 | .19* | .04–.33 | .12 | −.09–.32 | −.14 | −.36–.07 | ||||

| Scholastic Competence (13) | .22** | .06–.38 | .09 | −.05–.23 | .25** | .07–.44 | −.06 | −.28–.16 | ||||

| Physical Attractiveness (13) | .11 | −.05–.27 | .06 | −.08–.20 | −.01 | −.21–.19 | −.25* | −.47–−.04 | ||||

| Support Variable | ||||||||||||

| Call for Support to | .17* | .01.34 | .16* | .01–.30 | .15 | −.06–.35 | −.14 | −.36–.09 | ||||

| Mother (13) | .23*** | .25*** | .21** | .19* | ||||||||

Note. Gender coded as: 1 = males, 2 = females;

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001.

Table 5.

Predicting Markers of Functional Independence at age 25 from Calls for Support to Romantic Partner during Emerging Adulthood.

| Functional Independence (25) | Education Level (25) | Employment Status (25) | Lives at Home with Parent(s) (25) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| β final | 95% CI | R2 | β final | 95% CI | R2 | β final | 95% CI | R2 | β final | 95% CI | R2 | |

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Gender | −.17 | −.28–.13 | −.23* | −.26–.06 | −.16 | −.42–.05 | −.06 | −.27–.20 | ||||

| Income | .26* | .05–.49 | .41*** | .14–.48 | .11 | −.17–.33 | −.31* | −.45–.07 | ||||

| Potential Confounds | ||||||||||||

| Attachment Security (21) | −.03 | .00–.44 | −.10 | −.01–.36 | .02 | −.08–.41 | .09 | −.46–.04 | ||||

| Job Competence (22) | .28* | −.25–.19 | .51*** | .05–.40 | −.01 | −.18–.33 | −.06 | −.10–.43 | ||||

| Physical Attractiveness (21) | .11 | −.41–.20 | .09 | −.01–.37 | .09 | −.24–.32 | .05 | −.40–.20 | ||||

| Support Variable | ||||||||||||

| Call for Support to | .42** | .16–.70 | .27 | −.15–.39 | .10 | −.38–.44 | −.40* | −.68–−.01 | ||||

| Romantic Partner (21) | .31** | .42*** | .06 | .22 | ||||||||

Note.

Gender coded as: 1 = males, 2 = females;

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001.

Transfer of support seeking across relationships and developmental periods

Analyses next examined correlations between calls for support to best friends at age 13 (M = 3.53, SD = 1.60) and calls for support to best friends at age 18 (M = 3.76, SD = 1.12; r = .20, p < .01), and between support given from mothers at age 13 (M = 3.61, SD = 1.79) and calls for support to best friends at age 18 (r = .20, p < .01). Hierarchical regression analyses presented in Table 6 show that after controlling for gender, income, and calls for support to best friends at age 13, there was a significant positive effect of support given from mothers at age 13 on calls for support to best friends at age 18. Correlations were also used to examine potential bi-directional links between calls for support to romantic partners at age 18 (M = 3.75, SD = 1.43) and calls for support to romantic partners at age 21(M = 4.00, SD = 1.22; r = .23, p < .01), and between support given from best friends at age 18 (M = 3.61, SD = 1.79) and calls for support to romantic partners at age 21 (r = .57, p < .001). Hierarchical regression analyses presented in Table 7 show that after controlling for gender, income, and calls for support to romantic partners at age 18, there was a significant positive effect of support given from best friends at age 18 on calls for support to romantic partners at age 21.

Table 6.

Predicting Relative Change in Calls for Support from Best Friend from Support Given by Mother.

| Call for Support to Best Friend (18) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| β entry | β final | ΔR2 | R2 | |

| Step 1. | .06 | |||

| Gender | .22** | .21** | ||

| Income | .12 | .06 | ||

| Step 2. | .04** | .10* | ||

| Call for Support to | .20** | .17 | ||

| Best Friend (13) | ||||

| Step 3. | .02 | .12* | ||

| Support Given from | .15* | .15* | ||

| Mother (13) | ||||

Note.

Gender coded as: 1 = males, 2 = females;

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01.

Table 7.

Predicting Relative Change in Calls for Support from Romantic Partner from Support Given by Best Friend.

| Call for Support to Romantic Partner (21) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| β entry | β final | ΔR2 | R2 | |

| Step 1. | .01 | |||

| Gender | .10 | .10 | ||

| Income | −.06 | −.12 | ||

| Step 2. | .23* | .24 | ||

| Call for Support to | .45* | .12 | ||

| Romantic Partner (18) | ||||

| Step 3. | .11** | .34* | ||

| Support Given from | .51** | .51** | ||

| Best Friend (18) | ||||

Note. Gender coded as: 1 = males, 2 = females;

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01.

Post hoc analyses

Support seeking from alternative partners at alternative developmental periods

To examine the potential developmental saliency of calling for support from mothers at age 13, best friends at age 18, and romantic partners at age 21 relative to other relationship partners at these ages, separate alternative path models were tested with calls for support to best friends at age 13, calls for support to mothers and romantic partners at age 18, and best friends at age 21, respectively, as predictor variables. There were no significant associations between calls for support to any of these partners at these respective ages and any of the markers of independent functioning at age 25.

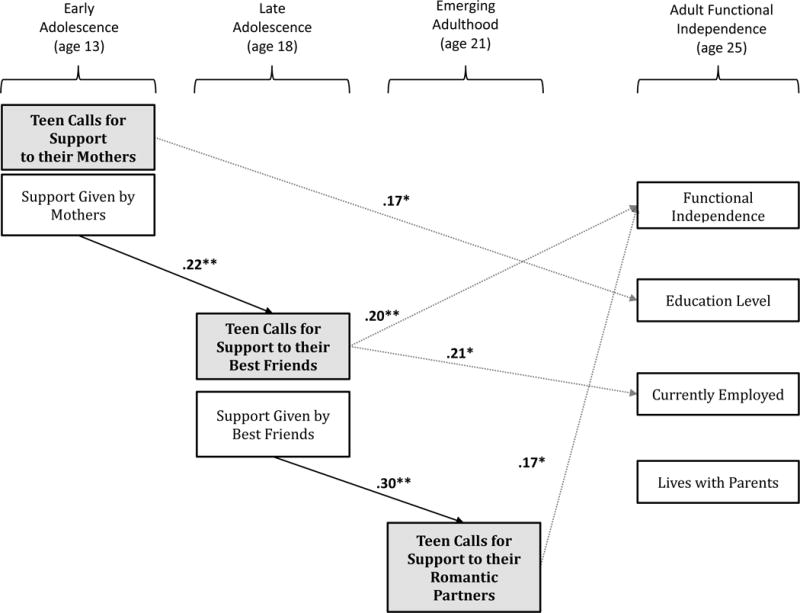

A final, full path model including all variables from the models outlined in Tables 3–5, support given from mothers at age 13 and from friends at age 18, and the variables described in the preceding paragraph, largely maintained the results described above, with the exception that the pathway from calls for support to mothers at age 13 was no longer predictive of functional independence and calls for support to romantic partners at age 21 was no longer predictive of living at home with parents (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overall path model of associations between support-seeking and support-giving behavior during different developmental periods and markers of adult functional independence in young adulthood. The model includes attachment, scholastic/job competence, and physical attractiveness at each time period, as well as calls for support to best friends at age 13, mothers and romantic partners at age 18, and best friends at age 21 (not pictured).

Variance explained by calls for support

Significant findings from path models were then probed as individual regression equations to determine the additional variance explained by each significant call for support variable after controlling for gender and income and potential confounding variables. Call for support to mothers at age 13 predicted a significant change in the variance explained for functional independence at age 25 (ΔR2 = .02, p < .05) and education level at age 25 (ΔR2 = .02, p < .05). Call for support to best friends at age 18 predicted a significant change in the variance explained for functional independence at age 25 (ΔR2 = .05, p < .01) and for current employment at age 25 (ΔR2 = .05, p < .05). Call for support to romantic partners at age 21 predicted a significant change in the variance explained for functional independence at age 25 (ΔR2 = .10, p < .001) but not for lives at home with parents at age 25 (ΔR2 = .04, p < .08).

Transfer of support seeking across alternative relationships

Post hoc analyses were also conducted to test whether the transfer of support seeking across partners and developmental periods would occur in opposite directions (i.e. support from best friends at 13 to call for support to mothers at 18 and support from romantic partners at 18 to calls for support to best friends at 21). However, support given from best friends at age 13 did not predict a relative increase in calls for support to mothers at age 18 and support given from romantic partners at age 18 did not predict a relative increase in calls for support to best friends at age 21.

Discussion

Many youth typically place great value on achieving individualistic markers of adulthood, such as becoming independent from parents and attaining the capacity to become a self-sufficient individual (Arnett, 1998). Though the ultimate achievement of adult status for the current generation – from both objective and subjective perspectives – tends to occur in the late twenties and early thirties, nearly three-quarters of individuals have attained stable employment, achieved financial independence, and moved out of their parents’ home by age thirty (Arnett, 2004; Goldscheider & Goldscheider, 1999). However, the factors that predict successful functional independence in adulthood in the years beforehand are less clear. Adolescence and emerging adulthood are often characterized as times when youth seek to increase their independence from others, and the extent to which youth are successful at achieving such independence throughout these periods might on its face appear to be a rather obvious potential marker of becoming a functionally independent adult. The results of this study suggest some nuance to this potential hypothesis; namely that maintaining appropriate levels of dependence on specific types of relationship partners during these years may be a key catalyst for helping youth to successfully reach markers of independent functioning. That is, a willingness to continue to look to others for help and support throughout adolescence and emerging adulthood may be crucial for establishing new levels of independence, and who youth turn to when may be equally as important.

This study found that adolescents’ willingness to ask their mothers, best friends, and romantic partners for support at different, yet specific, developmentally-appropriate stages of adolescence and emerging adulthood predicted a greater likelihood of achieving several markers of adult status by age 25. Greater efforts to seek support from parents at age 13, from best friends at age 18, and from romantic partners at age 21 each emerged as significant predictors of various qualities of future adult independence. Attachment theory offers some potential explanations for why these specific partners, at these particular ages, might be particularly influential with regard to youth’s development. According to this theory, parents are established as attachment figures that provide security and companionship in infancy and childhood, and continue to serve as primary figures through the beginning of early adolescence. Research suggests that parental support may be more influential during early adolescence and relatively less so over time as friends and romantic partners begin to fulfill attachment needs (Markiewicz, Lawford, Doyle, & Haggart, 2006). This may be in part because of the changing nature of youth’s attachment needs over time. During adolesence, focus is heightened with regard to issues that, from the adolescent’s perspective, may be more comfortably discussed with peers as compared to parents, such as social and romantic concerns (Buhrmester & Furman, 1987). During late adolescence and early adulthood, there is typically interest in establishing increased intimacy within relationships as well as a desire to fulfill sexual needs, which may be best fulfilled for youth by romantic partners. Evidence suggests that romantic relationships become more psychologically meaningful for youth relative to friendships, and that the intimacy provided by this type of relationship is particulary valuable during emerging adulthood (Meeus, Brange, van der Valk, & de Wied, 2007).

Cumulative continuity theory also provides a framework for understanding the results of this study. Teens’ more persistent and direct efforts to seek support from their mothers at age 13 were predictive of them being rated as more functionally independent and as having achieved a higher level of education 12 years later at age 25. Cumulative continuity theory would suggest that a proclivity of a teen to seek support from their mothers might be an interactional style that will lead them to seek support in future relationships (Caspi, Bem, & Elder, 1989). It may also be that teens who feel comfortable asking their mothers for help in early adolescence, and make efforts to do so, find greater success navigating tasks of adolescence that ultimately build upon each other and lead to success in adulthood. Thus, the contingency of perceiving benefits of seeking support may also increase the likelihood that youth continue to do so with others. Moreover, post-hoc tests of an alternative model revealed that seeking support from best friends at age 13 did not predict any markers of independence at age 25. In early adolescence, seeking support from parents may still be in adolescents’ best interests, as peers may not necessarily be any more skilled at handling problems of adolescence than teens are and thus not prepared to adequately address teens’ needs. Indeed, turning to peers prematurely during early adolescence has been associated with increased susceptibility to peer pressure and risk for problem behavior (Rosenthal & Kobak, 2010). In addition, at this age, seeking help from one’s mother may still seem appropriate with regard to peer norms, as the importance of teens’ peer networks for support processes is still just starting to emerge (Helsen et al., 2000).

By age 18, however, the developmental significance of seeking support from mothers appeared to give way to using peer relationships in this regard. Calls for support to best friends at age 18 were predictive of teens being rated as more functionally independent and as being currently employed at age 25. It may be that toward the end of adolescence, youth feel more comfortable trusting that their peers have endured similar or relevant experiences that might be useful for teens to draw from to support them through their own problems. Tests of alternative models considering calls for support to mothers and to romantic partners at this age did not reveal any significant associations between calls with these partners and markers of independence in adulthood. Adolescents may consider parents to be out of touch with the nature of their concerns by this age, or may desire to assert independence from parents by turning to peers for help instead (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992). It is also possible that romantic partners are not yet trusted enough as sources of support for adolescents at this age, as intimacy needed to facilitate such trust may not develop in such relationships until teens are slightly older (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992; Markiewicz et al., 2006).

Calls for support with romantic partners, however, emerged at age 21 as a significant predictor of functional independence and living independently of the parental home at age 25. Tests of an alternative model found that calls for support from best friends at age 21 were not predictive of any markers of adult status at age 25, reinforcing the notion that romantic partners may be particularly salient sources of support at this age. It is possible that romantic relationships become more trusted as sources of support by this time relative to friends. Participants reported romantic relationships averaging nearly 2 years duration at age 21, which has been theorized to be about the amount of time needed for a romantic relationship to become a more intimate attachment-type relationship, which may facilitate support seeking and provision (Fraley & Davis, 1997).

Notably, these predictions from support seeking to markers of independence were significant even after controlling for teens’ levels attachment security, scholastic/job competence, and physical attractiveness across all time periods examined. Each of these constructs has been linked in previous research to a greater provision of help and support from others, as well as to outcomes of interest to this study (Ceci & Williams, 1997; Kobak & Sceery; Langlois, 2000). Thus, controlling for these variables, including their potentially changing nature over time, strengthens an interpretation that support seeking behavior, and not one of these related factors, is a significant primary predictor of future independent functioning.

These findings not only suggest a changing salience of supportive partners during adolescence and emerging adulthood, but also offer one possibility for how such change may occur. It may be that support provided by a developmentally-salient partner at a prior stage of adolescence might in some way prepare youth for support seeking behavior with a new developmentally-salient partner at a later stage of adolescence. Results provided some evidence of this possibility, indicating that support provided by mothers at age 13 was predictive of more effortful calls for support to best friends at age 18. Notably, this finding was obtained even after accounting for teens’ levels of calls for support to best friends at age 13, thus suggesting that mothers’ support contributed to a relative increase in calls for support to friends over time. Similarly, support provided by best friends at age 18 significantly predicted more effortful calls for support to romantic partners at age 21 after controlling for teens’ calls for support to romantic partners at age 18. This suggests that support provided by best friends in late adolescence contributes to a relative increase in support seeking behavior with romantic partners in emerging adulthood. It may be that receiving higher quality support from mothers at age 13 increases teens’ confidence that when they seek support from others they are likely to receive it, making them more likely to take risks asking their friends for help in later adolescence. The same process may play out with regard to receiving help from peers in later adolescence and becoming more comfortable seeking support from romantic partners in emerging adulthood.

Overall, these findings suggest that choosing to depend on others for help during adolescence may have significant positive implications for later independent functioning in adulthood. Although adolescence is a life stage marked by autonomy development, these findings indicate that teens who ultimately attain markers of adult status are not those who aim to handle life’s problems completely independently, but rather those who appropriately seek help from others during times of need. Moreover, whom teens rely on, and when, seems to play a key role in predicting whether or not they will achieve functional independence in young adulthood. Findings suggest what may be a normative progression from relying on mothers, then friends, then romantic partners for support across adolescence and into emerging adulthood, and that support provided by earlier partners may set the stage for seeking support from alternative partners in the future.

This study was bolstered by its longitudinal nature and use of multiple methods, including observed calls for support with different relationship partners across adolescence, and both self- and mother-reports of markers of functional independence in young adulthood. Although this study utilized a large number of variables over a long range of time, attrition was relatively low. Predictions of calls for support to markers of adult status were found even after controlling for potentially confounding variables including attachment security, scholastic/job competence, and physical attractiveness, all assessed during the same developmental period as teens’ calls for support to each respective type of relationship partner. Similarly, predictions of future calls for support from earlier support given were found after controlling for earlier calls for support. Although causal pathways cannot be demonstrated without experimental methods, findings are consistent with the idea that support seeking processes during adolescence and emerging adulthood may be an underlying driving process that facilitates functional independence in adulthood.

Nevertheless, there are several important limitations to keep in mind. As previously mentioned, although strengthened by a longitudinal design, the correlational nature of this study precludes the confirmation of causal hypotheses regarding the achievement of functional independence in young adulthood. Conclusions from this study are based on a relatively small sample of youth from the Southeastern United States, and may not be representative of the general population. Although we observed the strength and persistence of adolescents’ calls for support with various partners, this study did not assess how often teens typically turn to specific partners for support at different points during adolescence, which may also be a critical variable for predicting future behavior. For example, it may be that there is an optimal reliance on others that, when surpassed, signals a type of dependency that inhibits independent functioning. This study also did not have information directly regarding the perceived quality of the relationships considered, which might be an important moderator of effects. Though use of multiple reporters throughout the study might be considered a strength, it would have been useful to have additional reporters’ perspectives in some instances, such as parents’ perceptions of scholastic/job competence and youths’ perceptions of their independence. Moreover, it was not always possible to use the same measure for a given construct assessed in the study. This study also did not assess potential changes in teens’ functional behavior during adolescence that may develop as a result of seeking help from others. That is, it may be that seeking help from others facilitates new autonomous experiences in adolescence that continue to build on one another and permit youth to develop the skills and confidence necessary to function independently as an adult. This study also did not have the opportunity to examine processes prior to adolescence that may represent formative experiences for support seeking behavior or functional independence. Finally, only one type of support seeking – teens’ willingness to ask for help when specifically tasked with doing so – was examined, meaning that additional research will be needed to determine if support seeking in alternative contexts yields similar results.

Taken together, these findings suggest the potential importance of considering the development of functional independence in young adulthood as a process that involves an earlier appropriate dependence on others to achieve. Although results indicated that such dependence may take place at several points during adolescence and emerging adulthood with different relationship partners, it appears that support provided by earlier developmentally-salient relationships may set the stage for support-seeking behaviors with subsequent partners. This suggests that individuals who have the greatest success in meeting developmental tasks of adulthood may be those who at the outset of adolescence start to recognize the benefits of asking others for help and begin doing so, transitioning to different types of relationship partners over time to meet this need. Thus, ultimately attaining markers of adult status may be a function of learning how to be independent from some individuals during different points in development while at the same time learning how to be appropriately dependent on others.

Table 4.

Predicting Markers of Functional Independence at age 25 from Calls for Support to Best Friend during Late Adolescence.

| Functional Independence (25) | Education Level (25) | Employment Status (25) | Lives at Home with Parent(s) (25) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| β final | 95% CI | R2 | β final | 95% CI | R2 | β final | 95% CI | R2 | β final | 95% CI | R2 | |

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Gender | −.08 | −.25–.08 | −.02 | −.17–.13 | −.24* | −.45–−.03 | −.04 | −.25–.17 | ||||

| Income | .20** | .05–.36 | .37*** | .24–.50 | .11 | −.08–.30 | −.22* | −.41–−.03 | ||||

| Potential Confounds | ||||||||||||

| Attachment Security (18) | .05 | −.16–.26 | .08 | −.11–.27 | −.12 | −.38–.15 | .07 | −.20–.34 | ||||

| Job Competence (18) | .17 | −.02–.36 | .15 | −.03–.33 | .02 | −.23–.27 | −.14 | −.39–.11 | ||||

| Physical Attractiveness (18) | .15 | −.02–.32 | .11 | −.04–.26 | .17 | −.05–.39 | −.32** | −.54– −.09 | ||||

| Support Variable | ||||||||||||

| Call for Support to | .27*** | .11–.44 | .14 | −.01.29 | .25** | .05–.46 | −.03 | −.24–.18 | ||||

| Best Friend (18) | .22*** | .24*** | .19* | .20* | ||||||||

Note. Gender coded as: 1 = males, 2 = females;

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001.

Acknowledgments

This study and its write-up were supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health (9R01 HD058305-11A1 & R01-MH58066).

References

- Achenbach T. Child behavior checklist/4-18. Burlington: University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T, Rescorla L. Manual for the ASEBA adult forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; Burlington, VT: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hall F, Insabella G, Land D, Marsh P, Porter M. Supportive behavior coding system. Charlottesville: University of Virginia; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hauser ST, Bell KL, O’Connor TG. Longitudinal Assessment of Autonomy and Relatedness in Adolescent-Family Interactions as Predictors of Adolescent Ego Development and Self-Esteem. Child Development. 1994;65(1):179–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Land D. Attachment in adolescence. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. 1999:319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, McElhaney KB, Kuperminc GP, Jodl KM. Stability and change in attachment security across adolescence. Child Development. 2004;75:1792–1805. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00817.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Moore C, Kuperminc G, Bell K. Attachment and adolescent psychosocial functioning. Child Development. 1998:1406–1419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. Unpublished revised version. Univeristy of Washington; Seattle, Washington: 1989. Inventory of parent and peer attachment: Revised manual. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Learning to stand alone: The contemporary American transition to adulthood in cultural and historical context. Human Development. 1998;41(5–6):295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Conceptions of the transition to adulthood: Perspectives from adolesence through midlife. Journal of Adult Development. 2001;8(2):133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. BDI, Beck depression inventory: manual. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ. Developmental changes in conformity to peers and parents. Dev Psychol. 1979;15(6):608–616. [Google Scholar]

- Bokhorst CL, Sumter SR, Westenberg PM. Social support from parents, friends, classmates, and teachers in children and adolescents aged 9 to 18 years: Who is perceived as most supportive? Soc Dev. 2010;19(2):417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. Vol. 1. New York: Basic Books; 1969/1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A secure base. New York: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Furman W. The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development. 1987:1101–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, King J, Wilson J. Young Adult Adjustment Scale. Unpublished instrument, Oregon Social Learning Center 1992 [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Bem DJ, Elder GH. Continuities and consequences of interactional styles across the life course. Journal of Personality. 1989;57(2):375–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1989.tb00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver RP. Intelligence and reading ability in Grades 2–12. Intelligence. 1990;14(4):449–455. [Google Scholar]

- Ceci SJ, Williams WM. Schooling, intelligence, and income. American Psychologist. 1997;52(10):1051. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JC. Relationships in adolescence. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JC. The focal theory of adolescence: A psychological perspective. The social world of adolescents. 1989:43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Feeney BC. A safe haven: An attachment theory perspective on support seeking and caregiving in intimate relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78(6):1053–1073. doi: 10.1O37//OO22-3514.78.6.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fass ME, Tubman JG. The influence of parental and peer attachment on college students’ academic achievement. Psychology in the Schools. 2002;39(5):561–573. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney BC. The dependency paradox in close relationships: accepting dependence promotes independence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92(2):268. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Davis KE. Attachment formation and transfer in young adults’ close friendships and romantic relationships. Pers Relatsh. 1997;4(2):131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Age and Sex Differences in Perceptions of Networks of Personal Relationships. Child Development. 1992;63(1):103–115. doi: 10.2307/1130905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George C, Kaplan N, Main M. Adult attachment interview. Department of Psychology, University of California; Berkeley: 1996. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider F, Goldscheider C. The changing transition to adulthood: Leaving and returning home. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson LS. Why g matters: The complexity of everyday life. Intelligence. 1997;24(1):79–132. [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD, Cooper CR. Patterns of interaction in family relationships and the development of identity exploration in adolescence. Child Development. 1985:415–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Unpublished manuscript. University of Denver; 1985. The self-perception profile for children: Revision of the perceived competence scale for children. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Unpublished manuscript. University of Denver; 1988. The self-perception profile for adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- Helsen M, Vollebergh W, Meeus W. Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolesence. J Youth Adolesc. 2000;29(3):319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Hill JP, Holmbeck GN. Attachment and autonomy during adolescence. Annals of Child Development. 1986;3(45):145–189. [Google Scholar]

- Hosoda M, Stone-Romero EF, Coats G. The effects of physical attractiveness on job-related outcomes: A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Personnel Psychology. 2003;56(2):431–462. [Google Scholar]

- Judge TA, Hurst C, Simon LS. Does it pay to be smart, attractive, or confident (or all three)? Relationships among general mental ability, physical attractiveness, core self-evaluations, and income. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2009;94(3):742. doi: 10.1037/a0015497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Childhood depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1990;31(1):121–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1990.tb02276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kins E, Beyers W. Failure to Launch, Failure to Achieve Criteria for Adulthood? Journal of Adolescent Research. 2010;25(5):743–777. doi: 10.1177/0743558410371126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Cole H, Ferenz-Gillies R, Fleming W, Gamble Attachment and emotion regulation during mother-teen problem-solving: A control theory analysis. Child Development. 64:231–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Sceery A. Attachment in late adolescence: Working models, affect regulation, and representations of self and others. Child Development. 1988:135–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koestner R, Powers TA, Carbonneau N, Milyavskaya M, Chua SN. Distinguishing autonomous and directive forms of goal support: their effects on goal progress, relationship quality, and subjective well-being. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2012;38(12):1609–1620. doi: 10.1177/0146167212457075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopera AA, Maier RA, Johnson JE. Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association. American Psychological Association; 1971. Perception of physical attractiveness: The influence of group interaction and group coaction on ratings of women. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Beck AT. An empirical-clinical approach toward a definition of childhood depression. Depression in childhood: Diagnosis, treatment, and conceptual models. 1977:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Laible D. Attachment with parents and peers in late adolescence: Links with emotional competence and social behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43(5):1185–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Langlois JH, Kalakanis L, Rubenstein AJ, Larson A, Hallam M, Smoot M. Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(3):390. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Solomon A, Seeley JR, Zeiss A. Clinical implications of" subthreshold" depressive symptoms. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2000;109(2):345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx K, Schwartz SJ, Goossens L, Pollock S. Employment, Sense of Coherence, and Identity Formation: Contextual and Psychological Processes on the Pathway to Sense of Adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2008;23(5):566–591. doi: 10.1177/0743558408322146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Goldwyn R. Adult attachment scoring and classification system. University of California; Berkeley: 1998. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Markiewicz D, Lawford H, Doyle AB, Haggart N. Developmental Differences in Adolescents’ and Young Adults’ Use of Mothers, Fathers, Best Friends, and Romantic Partners to Fulfill Attachment Needs. J Youth Adolesc. 2006;35(1):121–134. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-9014-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meeus WH, Branje SJ, van der Valk I, de Wied M. Relationships with intimate partner, best friend, and parents in adolescence and early adulthood: A study of the saliency of the intimate partnership. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007;31(6):569–580. [Google Scholar]

- Ng TW, Eby LT, Sorensen KL, Feldman DC. Predictors of objective and subjective career success: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology. 2005;58(2):367–408. [Google Scholar]

- Patzer GL. The physical attractiveness phenomena. Springer Science & Business Media; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Rabaglietti E, Ciairano S. Quality of friendship relationships and developmental tasks in adolescence. Cognition, Brain, & Behavior. 2008;12(2):183–203. [Google Scholar]

- Ratelle CF, Simard K, Guay F. University Students’ Subjective Well-being: The Role of Autonomy Support from Parents, Friends, and the Romantic Partner. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2013;14(3):893–910. doi: 10.1007/s10902-012-9360-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Caspi A. The cumulative continuity model of personality development: Striking a balance between continuity and change in personality traits across the life course Understanding human development. Springer; 2003. pp. 183–214. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal NL, Kobak R. Assessing adolescents’ attachment hierarchies: Differences across developmental periods and associations with individual adaptation. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20(3):678–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke. Predicting the timing of leaving home and related developmental tasks: Parents’ and children’s perspectives. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2010;27(4):495–518. doi: 10.1177/0265407510363426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I. Testing theories of romantic development from adolescence to young adulthood: Evidence of a developmental sequence. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2003;27(6):519–531. doi: 10.1080/01650250344000145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Silk JS. Parenting adolescents. Handbook of parenting. 2002;1:103–133. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Silverberg SB. The vicissitudes of automony in early adolescence. Child Development. 1986;57:841–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1986.tb00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Hughes M. The impact of physical attractiveness on achievement and psychological well-being. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1987:227–236. [Google Scholar]

- von Salisch M. Children’s emotional development: Challenges in their relationships to parents, peers, and friends. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2001;25(4):310–319. [Google Scholar]

- Ward MJ, Carlson EA. Associations among adult attachment representations, maternal sensitivity, and infant-mother attachment in a sample of adolescent mothers. Child Development. 1995;66:69–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White LK, Rogers SJ. Strong Support but Uneasy Relationships: Coresidence and Adult Children’s Relationships with Their Parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1997;59(1):62–76. doi: 10.2307/353662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]