This article reports the cardiac safety data from a single institutional retrospective cohort study of patients with HER2‐positive breast cancer treated with dose‐dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC) followed by paclitaxel with trastuzumab and pertuzumab in the neoadjuvant setting followed by completion of 1 year of adjuvant anti‐HER2 therapy.

Keywords: Cardiotoxicity, Heart failure, Trastuzumab, Pertuzumab

Abstract

Background.

Trastuzumab and pertuzumab are approved for the neoadjuvant treatment of human epidermal growth receptor 2 (HER2)‐positive breast cancer, but cardiac safety data is limited. We report the cardiac safety of dose‐dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC) followed by paclitaxel, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab (THP) in the neoadjuvant setting followed by adjuvant trastuzumab‐based therapy.

Methods.

Fifty‐seven patients treated with neoadjuvant dose‐dense AC‐THP followed by adjuvant trastuzumab‐based therapy between September 1, 2013, and March 1, 2015, were identified. The primary outcome was cardiac event rate, defined by heart failure (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class III/IV) or cardiac death. Patients underwent left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) monitoring at baseline, after AC, and serially during 1 year of anti‐HER2 therapy.

Results.

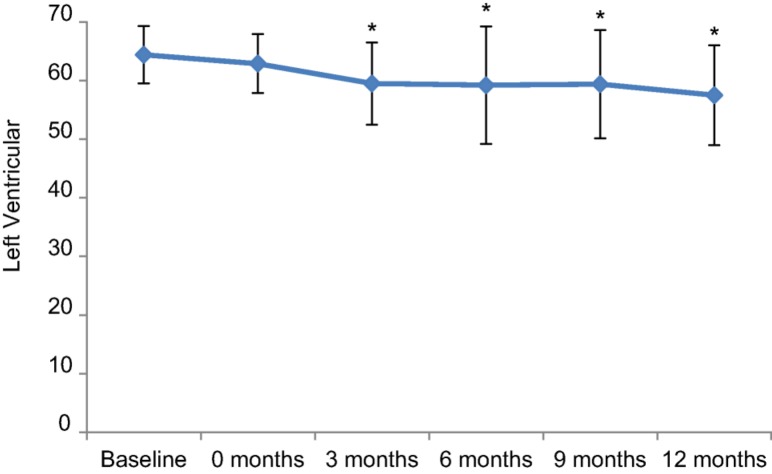

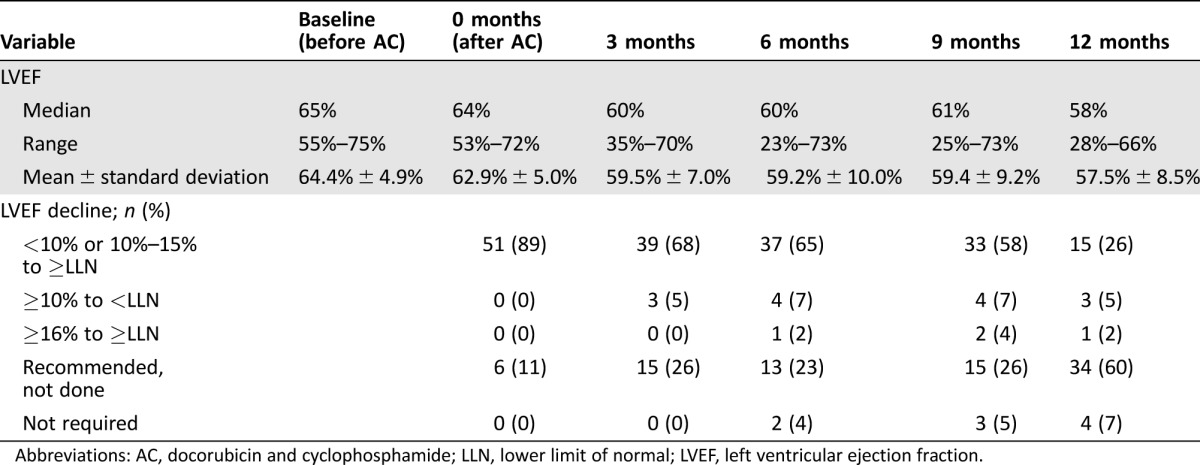

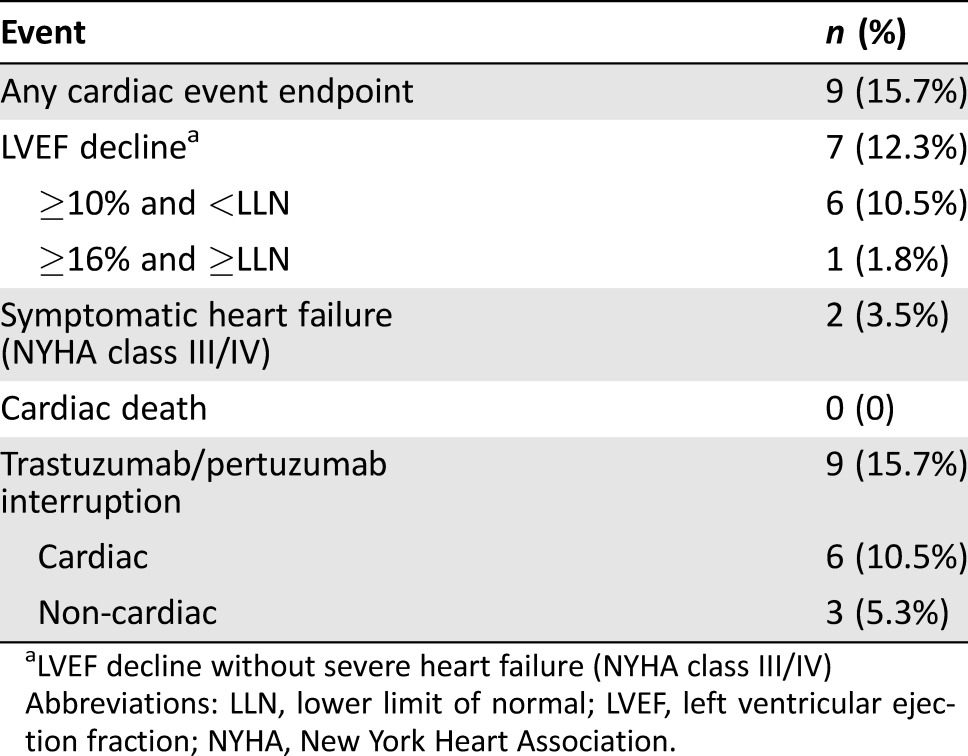

The median age was 46 years (range 26–68). Two (3.5%) patients developed NYHA class III/IV heart failure 5 and 9 months after initiation of trastuzumab‐based therapy, leading to permanent discontinuation of anti‐HER2 treatment. Seven (12.3%) patients developed a significant LVEF decline (without NYHA class III/IV symptoms). The median LVEF was 65% (range 55%–75%) at baseline and 64% (range 53%–72%) after AC, and decreased to 60% (range 35%–70%), 60% (range 23%–73%), 61% (range 25%–73%), and 58% (range 28%–66%) after 3, 6, 9, and 12 months (± 6 weeks) of trastuzumab‐based therapy.

Conclusion.

The incidence of NYHA class III/IV heart failure after neoadjuvant AC‐THP (followed by adjuvant trastuzumab‐based therapy) is comparable to rates reported in trials of sequential doxorubicin and trastuzumab. Our findings do not suggest an increased risk of cardiotoxicity from trastuzumab plus pertuzumab following a doxorubicin‐based regimen.

Implications for Practice.

Dual anti‐human epidermal growth receptor 2 (HER2) therapy with trastuzumab and pertuzumab combined with standard chemotherapy has received accelerated approval for the neoadjuvant treatment of stage II–III HER2‐positive breast cancer. Cardiac safety data for trastuzumab and pertuzumab in this setting are limited to clinical trials that utilized epirubicin‐based chemotherapy. Formalized investigations into the cardiac safety of trastuzumab and pertuzumab with doxorubicin‐ (rather than epirubicin) based regimens are important because these regimens are widely used for the adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatment of breast cancer. The known role of HER2 signaling in the physiological adaptive responses of the heart provides further rationale for study on the potential cardiotoxicity of dual anti‐HER2 blockade. Findings from this retrospective study provide favorable preliminary data on the cardiac safety of trastuzumab and pertuzumab in combination with a regimen of neoadjuvant doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel, one of the preferred breast cancer treatment regimens, according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

摘要

背景. 曲妥珠单抗和帕妥珠单抗已获批用于人类表皮生长因子受体2(HER2)阳性乳腺癌的新辅助治疗, 但心脏安全性数据有限。我们报告了患者依次使用多柔比星和环磷酰胺(AC)以及紫杉醇、曲妥珠单抗和帕妥珠单抗(THP)进行剂量密集型新辅助治疗, 随后接受以曲妥珠单抗为基础的辅助治疗时的心脏安全性。

方法. 共有57例患者于2013年9月1日至2015年3月1日期间接受剂量密集型AC‐THP新辅助治疗, 随后接受以曲妥珠单抗为基础的辅助治疗。主要结局为心脏事件的发生率, 定义为心力衰竭[纽约心脏协会(NYHA)III/IV级]或心源性死亡。在基线时、AC治疗后以及为期1年的抗HER2治疗期间连续监测患者的左心室射血分数(LVEF)。

结果. 患者的中位年龄为46岁(范围:26‐68岁)。2例(3.5%)患者分别在开始以曲妥珠单抗为基础的治疗后5个月和9个月出现NYHA III/IV级心力衰竭, 并因此永久性中止抗HER2治疗。7例(12.3%)患者的LVEF显著降低(不伴NYHA III/IV级症状)。基线时中位LVEF为65%(范围:55%‐75%), AC治疗后为64%(范围:53%‐72%), 以含曲妥珠单抗的方案治疗后3个月、6个月、9个月和12个月(± 6周)时分别降至60%(范围:35%‐70%)、60%(范围:23%‐73%)、61%(范围:25%‐73%)和58%(范围:28%‐66%)。

结论. AC‐THP新辅助治疗(随后进行以曲妥珠单抗为基础的辅助治疗)后NYHA III/IV级心力衰竭的发生率与多柔比星和曲妥珠单抗序贯治疗试验中报告的发生率相当。我们的结果显示, 在基于多柔比星的方案后以曲妥珠单抗联合帕妥珠单抗进行治疗时, 心脏毒性风险并未增加。The Oncologist 2017;22:642–647

对临床实践的提示:曲妥珠单抗和帕妥珠单抗双重抗HER2治疗联合标准化疗已获得加速审批, 用于II‐III期HER2阳性乳腺癌的新辅助治疗。曲妥珠单抗和帕妥珠单抗在此种条件下的心脏安全性数据仅来源于使用含表柔比星的化疗方案进行的临床试验。曲妥珠单抗和帕妥珠单抗联合基于多柔比星(而非表柔比星)的方案已广泛用于乳腺癌的辅助治疗和新辅助治疗, 因此有必要正式考察其心脏安全性。现已阐明HER2信号传导在心脏生理适应性反应中的作用, 这为抗HER2治疗双重阻滞的潜在心脏毒性提供了进一步的研究依据。本项回顾性研究的结果就曲妥珠单抗和帕妥珠单抗与由多柔比星和环磷酰胺及随后的紫杉醇组成的新辅助治疗方案(根据美国国家综合癌症网络, 此为乳腺癌首选治疗方案之一)联用时的心脏安全性提供了有利的初步数据。

Introduction

Approximately 20%–25% of all primary invasive breast cancers overexpress the human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 (HER2) [1]. Overexpression of HER2 is associated with a more aggressive clinical phenotype and worse prognosis [2]. Results from four phase‐III randomized trials demonstrate that trastuzumab administered in combination with chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting significantly improves outcomes for women with early‐stage breast cancer [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. The Neoadjuvant Herceptin (NOAH) study demonstrated an improvement in event‐free and overall survival with the addition of trastuzumab to neoadjuvant chemotherapy [9]. Further improvements in pathologic complete response rates were achieved with the administration of dual anti‐HER2 therapy with trastuzumab and pertuzumab in the NeoSphere and TRYPHAENA trials, leading to the approval of pertuzumab in the neoadjuvant setting [10], [11].

Cardiotoxicity, specifically, a significant decline of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) with or without heart failure, is an important adverse effect associated with trastuzumab, particularly when given in combination with anthracycline‐based therapy [12]. The rate of severe heart failure (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class III or IV) has been reported from 0.5% to 4.1% in the clinical trials of trastuzumab in the adjuvant setting [3], [4], [5], [6], [13]. There is a concern that use of dual anti‐HER2 therapy and, thus, more complete HER2 blockade may result in increased cardiotoxicity given the importance of HER2 signaling for growth, repair, and survival of cardiomyocytes [14], [15]. Previous studies have reported on the cardiac safety of trastuzumab and pertuzumab in combination with taxane‐based chemotherapy in patients with metastatic HER2‐positive breast cancer [16], [17]. Similarly, trastuzumab and pertuzumab in combination with epirubicin‐based chemotherapy was well tolerated from a cardiac standpoint in the TRYPHAENA study [11]. However, no current published data is available on the cardiac safety of trastuzumab plus pertuzumab administered sequentially after a doxorubicin‐based treatment, a regimen that is endorsed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and widely used for the adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatment of HER2‐positive breast cancer [18]. Here we report the cardiac safety data from a single institutional retrospective cohort study of patients with HER2‐positive breast cancer treated with dose‐dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC) followed by paclitaxel with trastuzumab and pertuzumab (THP; AC→THP) in the neoadjuvant setting followed by completion of 1 year of adjuvant anti‐HER2 therapy.

Materials and Methods

Women diagnosed with early‐stage HER2‐positive breast cancer from September 1, 2013, to March 1, 2015, were identified in the medical records database with a waiver approved by the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Search criteria consisted of patients who had HER2‐positive breast cancer being treated with pertuzumab and trastuzumab in the neoadjuvant setting during this time period. All patients had HER2‐positive disease defined by an immunohistochemical score of 3+ or by a fluorescent in‐situ hybridization ratio of ≥2.0. Patients received dose‐dense AC (60/600 mg/m2) every 2 weeks for four cycles with pegylated granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor support followed by weekly paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) for 12 weeks with trastuzumab (8 mg/kg loading dose followed by 6 mg/kg) and pertuzumab (840 mg loading dose followed by 420 mg) every 3 weeks from the start of paclitaxel.

A retrospective chart review was performed with the following data extracted: patient demographics, tumor characteristics, cancer treatment details, and baseline cardiovascular comorbidities (i.e., hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease). Clinical stage was determined by the breast surgeon's assessment at the initial visit based on clinical examination and available imaging. Data from all LVEF assessments by two‐dimensional echocardiography, multi‐gated acquisition scan, or cardiac MRI were obtained. The primary outcome was a cardiac event, defined as NYHA class III/IV heart failure or cardiac death in patients treated with dose‐dense AC→THP at any time from the start of neoadjuvant doxorubicin‐based treatment to the completion of 1 year of adjuvant trastuzumab‐based therapy. The secondary cardiac outcome was a significant LVEF decline without severe heart failure (NYHA class III/IV) in the same time period, defined by an absolute decline of ≥10% from baseline to below the lower limit of normal (53% at our institution) [19] or ≥16% (and above the lower limit of normal). Interruption of anti‐HER2 therapy was defined by interruption of one or more doses or ≥6 weeks between doses. All patients were followed until completion of 1 year of adjuvant trastuzumab‐based therapy or interruption of adjuvant trastuzumab‐based therapy.

Descriptive statistics were used for patient characteristics. Continuous measures were summarized as median and range or mean and standard deviation, whereas categorical measures were summarized as frequency and percent. Comparisons in LVEF from baseline to 0 (pre‐trastuzumab), 3, 6, 9, and 12 months (±6 weeks) of anti‐HER2 therapy were made using a paired Student's t test.

Results

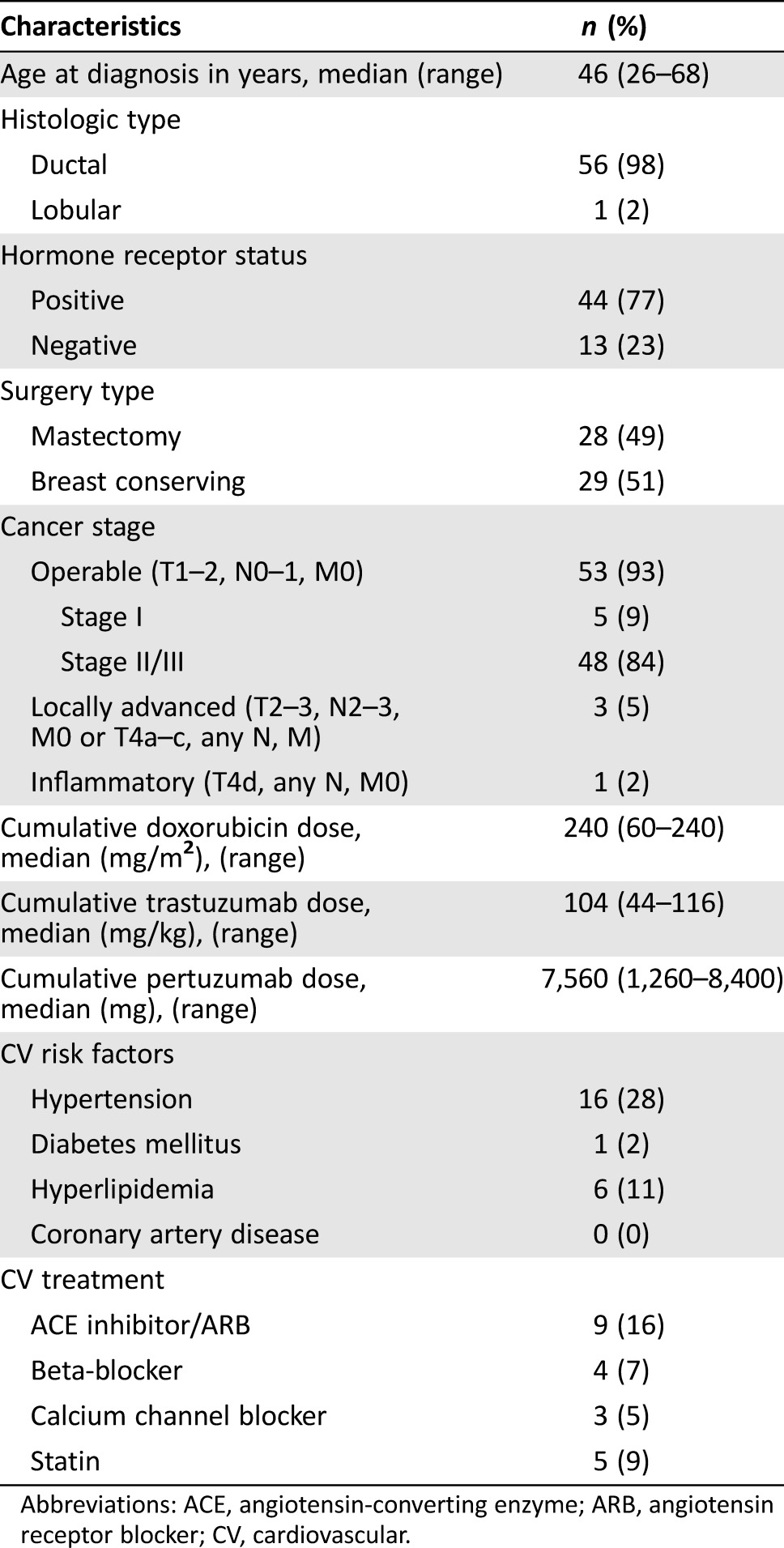

Between September 1, 2013, and March 1, 2015, 66 patients were treated with trastuzumab and pertuzumab in the neoadjuvant setting. In total, 57 patients were evaluable for the primary endpoint (three did not receive anthracycline chemotherapy, one pursued care elsewhere, one developed metastatic disease during chemotherapy, one received AC postoperatively, two did not receive weekly paclitaxel, and one had incomplete medical records). The median age was 46 years (range, 26 to 68 years); 53 (93%) patients were younger than 65 years. The median number of cycles of AC was four (range one to four), and the median number of cycles of trastuzumab and pertuzumab in the neoadjuvant setting was six (range three to eight) and six (range two to eight), respectively. After the neoadjuvant phase, patients underwent definitive breast surgery; 29 (51%) and 28 (49%) underwent lumpectomy and mastectomy, respectively. In the adjuvant phase, 55 (96%) received trastuzumab with pertuzumab with a median cycle number of 12 (range one to 13); two (4%) received trastuzumab alone (range 11 to 13 cycles). Overall, eight of 57 (14%) patients did not complete a full course of anti‐HER2 therapy (≥17 cycles) due to the following: two for symptomatic heart failure (NYHA class III or IV), two for asymptomatic LVEF decline, one for a possible cardiac adverse event (i.e., palpitation and atypical chest pain), one for patient refusal, one for physician preference, and one lost to follow‐up. Baseline clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CV, cardiovascular.

Changes in Cardiac Function

All patients had a normal baseline LVEF prior to the initiation of breast cancer treatment. The median LVEF was 65% (range 55% to 75%) at baseline and 64% (range 53% to 72%) after completion of anthracycline chemotherapy. There was a decline in median LVEF (p < .01 at all time points) at 3 months (60%, range 35% to 70%), 6 months (60%, range 23% to 73%), 9 months (61%, range 25% to 73%), and 12 months (58%, range 28% to 66%) (Fig. 1, Table 2). Based on current cardiac monitoring recommendations [20], a LVEF assessment was recommended but not performed in 6 (11%), 15 (26%), 13 (23%), 15 (26%), and 34 (60%) of the patients at 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months (±6 weeks) of anti‐HER2 therapy.

Figure 1.

Time course of left ventricular ejection fraction in 57 patients with human epidermal growth receptor 2 (HER2)‐positive breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant dose‐dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide and paclitaxel, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab followed by completion of anti‐HER2 therapy in the adjuvant setting. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. *p < .01 versus baseline.

Table 2. Summary of LVEF during neoadjuvant treatment period (baseline to 3 months of trastuzumab/pertuzumab) and adjuvant phase (3 to 12 months) and changes from baseline values (n = 57).

Abbreviations: AC, docorubicin and cyclophosphamide; LLN, lower limit of normal; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Primary and Secondary Cardiac Events

Of 57 evaluable patients, two (3.5%; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.4% to 12.1%) had a primary cardiac event with NYHA class III or IV heart failure (Table 3), and no cardiovascular associated deaths were observed. The first patient was 64 years old with history of hypertension that was well controlled on an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB). LVEF at baseline and upon completion of anthracycline chemotherapy was 59% and 57%, respectively. No additional LVEF assessments were performed due to patient noncompliance until approximately 9 months after initiating trastuzumab‐based therapy, when she was hospitalized for evaluation of shortness of breath at rest. An echocardiogram revealed severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVEF 25%), and trastuzumab and pertuzumab were permanently discontinued. After initiation of heart failure treatment with a beta‐blocker and escalating doses of ARB, LVEF improved to 42% at 6 months after cessation of anti‐HER2 therapy. The second patient was 63 years old with history of hypertension but was on no antihypertensive medications. LVEF at baseline and upon completion of anthracycline chemotherapy was 69% and 58%, respectively. Approximately 4.5 months after initiating trastuzumab‐based therapy, she developed a decrease in LVEF to 47% associated with exertional shortness of breath. The patient was treated with β‐blocker and angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. However, LVEF declined further to 20%–25% with progressively worsening heart failure symptoms (NYHA class III) requiring hospitalization, and trastuzumab and pertuzumab were permanently discontinued. A cardiology evaluation revealed the presence of multivessel obstructive coronary artery disease; however, the etiology of her heart failure was attributed to adverse effects from anthracycline and anti‐HER2 treatment.

Table 3. Cardiac events.

LVEF decline without severe heart failure (NYHA class III/IV)

Abbreviations: LLN, lower limit of normal; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

In terms of the secondary cardiac endpoint, seven (12.3%; 95% confidence interval: 5.1% to 23.7%) patients developed a significant LVEF decline (without severe heart failure symptoms). Six patients had a decline in LVEF of ≥10% from baseline to below the lower limit of normal (LLN): four patients had an interruption of trastuzumab and pertuzumab, one patient had LVEF decline at completion of anti‐HER2 therapy, and one patient was lost to follow‐up. One patient had a decline in LVEF ≥16% to above the LLN (from baseline of 75% to 57%), but she safely continued trastuzumab and pertuzumab without interruption. In the four patients with interruption of trastuzumab and pertuzumab, dual anti‐HER2 therapy was reinitiated 2–9 months later after recovery of LVEF; however, one patient developed a recurrent LVEF decline, resulting in permanent discontinuation. Complete details of primary and secondary cardiac events can be found in the supplemental online Table 1.

Discussion

In the current study, the use of dual anti‐HER2 therapy with trastuzumab and pertuzumab in combination with paclitaxel after dose‐dense AC in the neoadjuvant setting was generally well tolerated from a cardiac standpoint. The incidence of severe heart failure (NYHA class III/IV) and significant LVEF decline observed in this study are comparable to the rates reported in clinical trials of sequential anthracyclines and trastuzumab (without pertuzumab) [3], [4], [5]. Importantly, it does not appear that dual anti‐HER2 blockade with trastuzumab and pertuzumab following doxorubicin‐based chemotherapy increases the risk of severe heart failure or LVEF decline above and beyond the risk associated with single‐agent trastuzumab combined with standard chemotherapy. This further supports the cardiac safety that we and others have reported for dual anti‐HER2 therapy in the metastatic setting [16], [17]. The efficacy data in terms of pathologic complete response from neoadjuvant AC followed by THP have been reported in a separate manuscript [21]. The BERENICE and APHINITY trials will provide prospective data on the cardiac safety of regimens that include AC followed by a taxane with trastuzumab plus pertuzumab (NCT02132949, NCT01358877).

The molecular mechanisms associated with cardiotoxicity induced by anti‐HER2 agents, either alone or in combination, remain largely unknown. Binding of neuregulin‐1, an extracellular ligand, to HER2 receptors in cardiomyocytes activates multiple downstream pathways, including PI3K/Akt and extracellular signal‐regulated kinase 1/2 [22]. Differences in the cardiotoxic potential of anti‐HER2 antibodies may be attributable to the unique epitopes of HER2 recognized by each antibody and differential effects on downstream signaling pathways [23]. Dysregulation of autophagy in cardiomyocytes has recently been proposed as another potential mechanism of cardiotoxicity caused by trastuzumab, but not pertuzumab [24]. This may provide further mechanistic insight into the lack of increased cardiotoxicity when pertuzumab is added to trastuzumab therapy. The risk of cardiotoxicity is further potentiated when anti‐HER2 agents are administered sequentially after anthracycline chemotherapy. Given the known efficacy and increased cardiac safety profile of non‐anthracycline chemotherapy regimens, this raises the question of whether the risk–benefit ratio favors use of non‐anthracycline chemotherapy regimens (e.g., docetaxel and carboplatin) over anthracycline‐based regimens (e.g., doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and taxane) for treatment of HER2‐positive disease [25]. The most rigorous evidence available to date supports the use of anthracycline‐based regimens in patients with moderate to high risk HER2‐positive disease, although non‐anthracycline regimens remain an important treatment option for patients with a significant cardiac history or other clinical reasons to avoid anthracyclines.

Cardiotoxicity that develops in women without any preexisting cardiovascular risk factors remains a challenge. For example, two of the nine patients who developed significant LVEF decline without severe heart failure symptoms in our study were young (age <50 years), had a pre‐anthracycline LVEF >55%, and had no history of hypertension, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia. These patients would not be identified as at risk by available prediction models, highlighting the need for better predictors for use in clinical practice [26], [27]. The unexplained variability in the observed cardiovascular adverse effects of anti‐HER2 therapy suggests that genetic factors may play a role in one's susceptibility to chemotherapy‐induced cardiotoxicity. The majority of studies to date have utilized a candidate‐gene approach to identify genetic risk markers, focusing on genes involved in drug absorption, distribution, and metabolism [28], [29], [30]. However, a limited understanding of the underlying mechanism of cardiotoxicity limits future advances using a candidate‐gene approach and may suggest the need to consider a broader genome‐wide approach [31].

Our study is limited by its retrospective nature and limited sample size. However, the study is important because we ascertained patient‐specific information regarding the time course and severity of LVEF decline as well as the clinical course of cardiotoxicity for each patient through a comprehensive review of the electronic medical record. This approach allowed for careful adjudication of cardiac endpoints, thereby overcoming a limitation of larger studies that have relied on the use of administrative data [32], [33], [34]. Longer‐term cardiac follow‐up beyond the immediate breast cancer treatment period is needed to evaluate the occurrence of late cardiac adverse effects. Although anthracycline‐induced cardiotoxicity has been described as occurring many years after treatment, more recent data suggests that cardiotoxicity most often presents within the first year [35]. Furthermore, extrapolating from long‐term follow‐up data of clinical trials of trastuzumab‐based therapy in the adjuvant setting, the low incidence of cardiac events after a median follow‐up of 7 to 8 years is reassuring [13], [27].

Conclusion

In summary, the cardiac safety profile of a neoadjuvant doxorubicin‐based regimen followed by THP with completion of 1 year of adjuvant trastuzumab‐based therapy is encouraging. Our results do not suggest an increase in risk of cardiotoxicity from the addition of pertuzumab to standard therapy. We eagerly await the efficacy and cardiac safety results of ongoing clinical trials of dual anti‐HER2 therapy in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Roche/Genentech. This work was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

For Further Reading: Anthony F. Yu, Nandini U. Yadav, Anne A. Eaton et al. Continuous Trastuzumab Therapy in Breast Cancer Patients With Asymptomatic Left Ventricular Dysfunction. The Oncologist 2015;20:1105–1110.

Implications for Practice: Cardiotoxicity is the most common reason for patients with HER2‐positive breast cancer to receive an incomplete course of life‐saving trastuzumab therapy. Data from this study suggest that continuous trastuzumab may be safe in patients with asymptomatic cardiotoxicity and left ventricular ejection fraction of ≥50%. Given the substantial oncologic benefit of trastuzumab, increasing efforts are needed to ensure that patients complete the full course of treatment without interruption. Current recommendations for trastuzumab interruption in patients who develop cardiotoxicity should be re‐evaluated.

Author Contributions

Concept/Design: Anthony F. Yu, Chau T. Dang

Provision of study material or patients: Jasmeet Singh, Chau T. Dang

Collection and/or assembly of data: Anthony F. Yu, Chau T. Dang

Data analysis and interpretation: Anthony F. Yu, Jasmeet Singh, Rui Wang, Jennifer E. Liu, Anne Eaton, Kevin Oeffinger, Richard M. Steingart, Clifford A. Hudis, Chau T. Dang

Manuscript writing: Anthony F. Yu, Richard M. Steingart, Chau T. Dang

Final approval of manuscript: Anthony F. Yu, Jasmeet Singh, Jennifer E. Liu, Anne Eaton, Kevin Oeffinger, Richard M. Steingart, Clifford A. Hudis, Chau T. Dang

Disclosures

Chau T. Dang: Roche, Genentech (RF). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

Supplementary Information

References

- 1. Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG et al. Human breast cancer: Correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER‐2/neu oncogene. Science 1987;235:177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seshadri R, Firgaira FA, Horsfall DJ et al. Clinical significance of HER‐2/neu oncogene amplification in primary breast cancer. The South Australian Breast Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:1936–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2‐positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1673–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Slamon D, Eiermann W, Robert N et al. Adjuvant trastuzumab in HER2‐positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1273–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Piccart‐Gebhart MJ, Procter M, Leyland‐Jones B et al. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2‐positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1659–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perez EA, Romond EH, Suman VJ et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2‐positive breast cancer: Planned joint analysis of overall survival from NSABP B‐31 and NCCTG N9831. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3744–3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD, Piccart‐Gebhart MJ et al. 2 years versus 1 year of adjuvant trastuzumab for HER2‐positive breast cancer (HERA): An open‐label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;382:1021–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Slamon DJ, Eierman W, Robert NJ et al. Ten year follow‐up of the BCIRG‐006 trial comparing doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel (AC®T) with doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel and trastuzumab (AC®TH) with docetaxel, carboplatin and trastuzumab (TCH) in HER2+ early breast cancer patients: Proceedings of the 38th Annual Meeting of the CTRC‐AACR San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, 2015 Dec 8-12, San Antonio, TX. Philadelphia (PA). AACR, 2016.

- 9. Gianni L, Eiermann W, Semiglazov V et al. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant trastuzumab in patients with HER2‐positive locally advanced breast cancer (NOAH): Follow‐up of a randomised controlled superiority trial with a parallel HER2‐negative cohort. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:640–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gianni L, Pienkowski T, Im YH et al. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in women with locally advanced, inflammatory, or early HER2‐positive breast cancer (NeoSphere): A randomised multicentre, open‐label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schneeweiss A, Chia S, Hickish T et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab in combination with standard neoadjuvant anthracycline‐containing and anthracycline‐free chemotherapy regimens in patients with HER2‐positive early breast cancer: A randomized phase II cardiac safety study (TRYPHAENA). Ann Oncol 2013;24:2278–2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Telli ML, Witteles RM. Trastuzumab‐related cardiac dysfunction. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2011;9:243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Azambuja E, Procter MJ, van Veldhuisen DJ et al. Trastuzumab‐associated cardiac events at 8 years of median follow‐up in the Herceptin Adjuvant Trial (BIG 1‐01). J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2159–2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crone SA, Zhao YY, Fan L et al. ErbB2 is essential in the prevention of dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat Med 2002;8:459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cote GM, Sawyer DB, Chabner BA. ERBB2 inhibition and heart failure. N Engl J Med 2012;367:2150–2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Swain SM, Ewer MS, Cortes J et al. Cardiac tolerability of pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel in patients with HER2‐positive metastatic breast cancer in CLEOPATRA: A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled phase III study. The Oncologist 2013;18:257–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yu AF, Manrique C, Pun S et al. Cardiac safety of paclitaxel plus trastuzumab and pertuzumab in patients with HER2‐positive metastatic breast cancer. The Oncologist 2016;21:418–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Breast Cancer—NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (Version 1.2016). Available at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf. Accessed April 7, 2016.

- 19. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor‐Avi V et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: An update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015;28:1–39.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Genentech: Herceptin (trastuzumab) : Highlights of prescribing information, 04/2015 update. Available at http://www.gene.com/download/pdf/herceptin_prescribing.pdf. Accessed on March 7, 2017.

- 21. Singh JC, Mamtani A, Barrio A et al. Pathologic complete response rate with neoadjuvant doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel with trastuzumab and pertuzumab in patients with HER2‐positive early stage breast cancer: A single center. The Oncologist 2017;22:139–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. De Keulenaer GW, Doggen K, Lemmens K. The vulnerability of the heart as a pluricellular paracrine organ: Lessons from unexpected triggers of heart failure in targeted ErbB2 anticancer therapy. Circ Res 2010;106:35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fedele C, Riccio G, Malara AE et al. Mechanisms of cardiotoxicity associated with ErbB2 inhibitors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;134:595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mohan N, Shen Y, Endo Y et al. Trastuzumab, but not pertuzumab, dysregulates HER2 signaling to mediate inhibition of autophagy and increase in reactive oxygen species production in human cardiomyocytes. Mol Cancer Ther 2016;15:1321–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burstein HJ, Piccart‐Gebhart MJ, Perez EA et al. Choosing the best trastuzumab‐based adjuvant chemotherapy regimen: Should we abandon anthracyclines? J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2179–2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ezaz G, Long JB, Gross CP et al. Risk prediction model for heart failure and cardiomyopathy after adjuvant trastuzumab therapy for breast cancer. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e000472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Romond EH, Jeong JH, Rastogi P et al. Seven‐year follow‐up assessment of cardiac function in NSABP B‐31, a randomized trial comparing doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel (ACP) with ACP plus trastuzumab as adjuvant therapy for patients with node‐positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2‐positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3792–3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blanco JG, Leisenring WM, Gonzalez‐Covarrubias VM et al. Genetic polymorphisms in the carbonyl reductase 3 gene CBR3 and the NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 gene NQO1 in patients who developed anthracycline‐related congestive heart failure after childhood cancer. Cancer 2008;112:2789–2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stanton SE, Ward MM, Christos P et al. Pro1170 Ala polymorphism in HER2‐neu is associated with risk of trastuzumab cardiotoxicity. BMC Cancer 2015;15:267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Visscher H, Ross CJ, Rassekh SR et al. Pharmacogenomic prediction of anthracycline‐induced cardiotoxicity in children. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1422–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jensen BC, McLeod HL. Pharmacogenomics as a risk mitigation strategy for chemotherapeutic cardiotoxicity. Pharmacogenomics 2013;14:205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thavendiranathan P, Abdel‐Qadir H, Fischer HD et al. Breast cancer therapy‐related cardiac dysfunction in adult women treated in routine clinical practice: A population‐based cohort study. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2239–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen J, Long JB, Hurria A et al. Incidence of heart failure or cardiomyopathy after adjuvant trastuzumab therapy for breast cancer. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:2504–2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bowles EJ, Wellman R, Feigelson HS et al. Risk of heart failure in breast cancer patients after anthracycline and trastuzumab treatment: A retrospective cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012;104:1293–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cardinale D, Colombo A, Bacchiani G et al. Early detection of anthracycline cardiotoxicity and improvement with heart failure therapy. Circulation 2015;131:1981–1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.