Abstract

Fast-evolving MHC class I polymorphism serves to diversify NK cell and CD8 T cell responses in individuals, families, and populations. As only chimpanzee and bonobo have strict orthologs of all HLA class I, their study gives unique perspective on the human condition. We defined polymorphism of Papa-B, the bonobo ortholog of HLA-B, for six wild bonobo populations. Sequences for Papa-B exon 2 and 3 were determined from the genomic DNA in 255 fecal samples, minimally representing 110 individuals. Twenty-two Papa-B alleles were defined, each encoding a different Papa-B protein. No Papa-B is identical to any chimpanzee Patr-B, human HLA-B, or gorilla Gogo-B. Phylogenetic analysis identified a clade of MHC-B, defined by residues 45–74 of the α1 domain, which is broadly conserved among bonobo, chimpanzee, and gorilla. Bonobo populations have 3–14 Papa-B allotypes. Three Papa-B are in all populations, and they are each of a different functional type: allotypes having the Bw4 epitope recognized by killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) of NK cells, allotypes having the C1 epitope also recognized by KIR, and allotypes having neither epitope. For population ML these three Papa-B are the only Papa-B allotypes. Although small in number, their sequence divergence is such that the nucleotide diversity (mean p-distance) of Papa-B in ML is greater than in the other populations, and also greater than expected for random combinations of three Papa-B. Overall, Papa-B has substantially less diversity than Patr-B in chimpanzee subspecies and HLA-B in indigenous human populations, consistent with bonobo having experienced narrower population bottlenecks.

Introduction

In vertebrates, the MHC is a genomic region containing numerous immune system genes. Of these, the MHC class I and II genes are distinguished from all other vertebrate genes by the depth and breadth of their allelic polymorphism (1). MHC class I and II genes encode cell-surface glycoproteins that bind endogenous and pathogen-derived peptide antigens and present them to various families of lymphocyte receptors. Dedicated to adaptive immunity, MHC class II present antigens of extracellular pathogens to CD4 T cells (2, 3). In contrast, MHC class I function in innate immunity, adaptive immunity, and formation of the placenta during reproduction. During infection, MHC class I present peptide antigens of intracellular pathogens, notably viruses, to the receptors of NK cells of innate immunity (4) and CD8 T cells of adaptive immunity (5). During reproduction, MHC class I on fetal trophoblast cells present peptides of paternal origin to receptors of maternal, uterine NK cells (6). Because of these distinctive functions, MHC class I has a more diverse and rapidly evolving polymorphism than MHC class II (7–9).

As a consequence of the more rapid evolution of MHC class I, the only living species that have strict orthologs of all the polymorphic human MHC class I genes, HLA-A, -B and -C, are the great apes: chimpanzee, bonobo, gorilla, and orangutan (10). Co-evolving with MHC-A, -B and -C is the family of killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) (6, 11). Members of this family are inhibitory and activating receptors that recognize a set of alternative epitopes specified by sequence motifs at residues 76–83 in the α1 domain of MHC class I (12–16). These epitopes comprise the Bw4 epitope carried by subsets of MHC-A and -B allotypes, the C1 epitope carried by subsets of MHC-B and -C allotypes, and the C2 epitope carried by the subset of MHC-C allotypes that lack the C1 epitope (4, 6, 11, 14, 16, 17). The interactions between KIR and their MHC class I ligands are further diversified by sequence variation in the peptide bound by MHC class I, polymorphism at residues in MHC class I other than 76–83, and the high polymorphism of KIR, which rivals that of MHC class I (18–22). These interactions serve to modulate the development and function of NK cells (11). The diversity of MHC-KIR interactions individualizes NK cell responses, as is evident from the broad range of human diseases that correlate with HLA class I and KIR polymorphisms. (23–26).

Comparative studies of the genetics and function of chimpanzee MHC class I (27–32) and KIR (33–35) have provided a unique and valuable perspective that has increased knowledge and understanding of the human immune system. Providing equal opportunity for this approach is the bonobo (Pan paniscus), the sibling species to chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) that is as closely related to the human species as are chimpanzees (36). Our previous study of captive bonobos indicated that the bonobo KIR locus had undergone a process of gene loss and attenuation of KIR avidity for MHC class I similar to humans (37). However, limiting the interpretation of those results was an almost complete lack of knowledge of the bonobo MHC. Studies of captive bonobos identified only eight alleles each for MHC-A and -B, and five alleles for MHC-C (10, 38–42). In a recent study of the wild chimpanzee populations of Gombe National Park, Tanzania we defined the polymorphism of Patr-B (32), the ortholog of HLA-B, the most polymorphic human MHC class I gene (10, 27, 32, 43, 44). That investigation required development of a method for isolating Patr-B from chimpanzee feces. Because of the close phylogenetic relationship of chimpanzee and bonobo that method was directly applicable to the analysis of Papa-B, the bonobo ortholog of Patr-B and HLA-B. Here we define Papa-B of wild bonobos resident at sites throughout the bonobo range in the Democratic Republic of Congo (45).

Materials and Methods

This project is not classified as animal research by the Stanford Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care (APLAC) according to National Institutes of Health guidelines. Fecal samples from wild-living bonobos were collected non-invasively. Permission to collect samples in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) was granted by the DRC’s Ministry of Scientific Research and Technology, Department of Ecology and Management of Plant and Animal Resources of the University of Kisangani, Ministries of Health and Environment, and National Ethics committee. Use of the Yerkes National Primate Research Center bonobo samples was approved under Stanford APLAC-9057.

Study sites, sample collection, and sample typing

As described by Li et al. (45), teams of local trackers collected 255 fecal samples from non-habituated bonobos at six separate sites distributed throughout the bonobo range in the DRC: Malebo (ML), Lui-Kotale (LK), Ikela (IK), Balanga (BN), Kokolopori (KR) and Bayandjo (BJ) (Fig. 1, 2). Samples were obtained opportunistically and placed into an equal volume of RNAlater (Life Technologies), with each sample being labeled with a number, field site code, and GPS coordinates, whenever possible. Because the field sites lack refrigeration, samples were kept at ambient temperature before they were frozen (typically several weeks, but up to several months in some cases). Samples from ML were frozen at −80°C at the Institut National de Recherche Biomédicale in Kinshasa before being sent directly to the University of Montpellier, France. Samples from the five other sites were frozen at −20°C in the central laboratory at Kisangani, from where they were then sent to the United States. DNA was extracted from the samples and analyzed for mitochondrial hypervariable D-loop haplotype and by genotyping for 4–8 microsatellite loci (Li et al. (45): LK, IK, KR; this study: ML, BN, and BJ). For the fecal samples from ML, BN, and BJ, the sex of sample donors was determined using the PCR-based method described by Sullivan et al. (46).

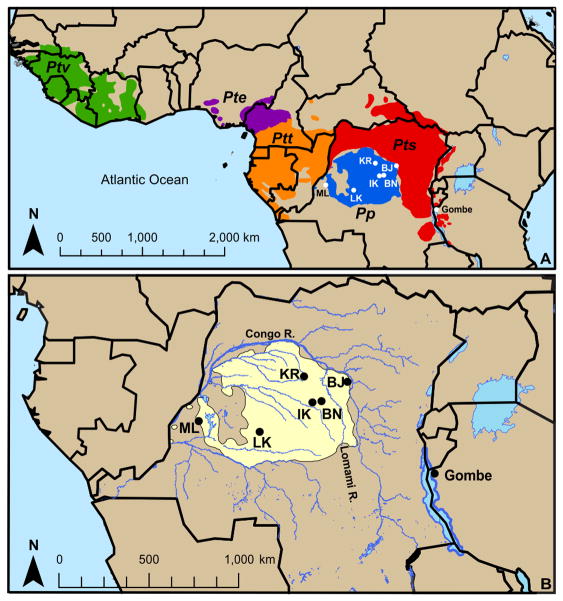

Figure 1. The bonobo range and locations of the populations studied.

(A) Map of Africa showing the range of bonobos (Pan paniscus, Pp) and the four chimpanzee subspecies (Pan troglodytes verus (Ptv, western), ellioti (Pte, Nigeria-Cameroon), troglodytes (Ptt, central), and schweinfurthii (Pts, eastern)). Location of the six bonobo study sites within the Democratic Republic of the Congo are shown by white circles and labeled with their two-letter codes: Malebo (ML), Lui-Kotale (LK), Ikela (IK), Balanga (BN), Kokolopori (KR), and Bayandjo (BJ)). The sites are separated by distance of approximately 30–1000 km. Also marked is the location of the wild Pts chimpanzee population in Gombe National Park, Tanzania. (B) Shown is an enlarged view of the six bonobo study sites (black circles) labeled with their two-letter codes and the Gombe Pts chimpanzee population. The bonobo range is highlighted in yellow, and blue lines show the rivers of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

DNA extraction and Papa-B PCR and sequencing

DNA was extracted from fecal samples using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) and the protocol described by Wroblewski et al. (32). Fecal DNA was amplified in three separate PCR reactions to yield exons 2 and 3 of Papa-B (as described for chimpanzees by Wroblewski et al. (32)). Exons 2 (270 bp) and 3 (276 bp) were targeted because they encode, respectively, the α1 and α2 domains that form the peptide-binding site of MHC-B. The α1 and α2 domains are the most variable and functionally engaged part of MHC-B. Each exon was amplified separately using primers designed from the intron sequences that flank the exons. These are conserved between chimpanzee Patr-B and bonobo Papa-B. The two standard PCR reactions produced amplicons of 425 bp (exon 2) and 411 bp (exon 3), similar sizes to the 137–328 bp amplicons of the bonobo microsatellite typing system. The third reaction was designed specifically to amplify exon 2 of alleles of the chimpanzee Patr-B*17 lineage (429 bp amplicon), which the standard exon 2 primers cannot amplify. This amplification was applied to all samples that appeared homozygous for exon 2 using the standard primers. However, no bonobo had an allele related to the Patr-B*17 lineage, either for exon 2 or exon 3.

We used the forward primer to sequence all PCR products. When this sequence indicated the presence of a novel allele, or when the sequence was ambiguous, the PCR products were cloned and sequenced. On detecting a candidate novel allele of Papa-B, its identity was confirmed with a second amplification, either from another individual or an independent amplification from the same individual. Before being applied to fecal DNA from wild bonobos, the standard pairs of amplification primers were validated by their capacity to amplify and sequence exons 2 and 3 of Papa-B from DNA extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of two captive bonobos (Lorel (Papa-B*01:01, *07:01) and Matata (homozygous Papa-B*07:01)) obtained from the Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center (Atlanta, Georgia). Bonobo PBMCs were isolated from samples of peripheral blood by Ficoll gradient separation. DNA was extracted from PBMCs using the QIAamp DNA Blood kit (Qiagen).

Papa-B allele inference

Because we amplified exons 2 and 3 separately we had to infer the phase of the exons to define the alleles. When exon 2 and 3 sequences were identical to those of a previously characterized allele (e.g. Papa-B*07:01), they were assumed to signify that allele and were paired together (Supplemental Fig. 1A). For heterozygous individuals containing an exon 2 and 3 pair from a previously identified allele, the other exon 2 and 3 pair was then inferred to define the second allele (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Most alleles (exon 2 and 3 pairs) were amplified more than once from different fecal DNA samples (from different individuals) and in different heterozygous combinations. Therefore, the repeated exon pair was inferred to comprise an allele, identifying the remaining pair as the second allele (Supplemental Fig. 1B). For all alleles observed in only one or two individuals at a particular site, all but one were observed in heterozygous genotypes (both for exons 2 and 3) with alleles commonly observed in other individuals and/or at other sites (Fig. 2, Supplemental Table 1A–F). This facilitated the identification of alleles according to the above criteria. In one exception, a novel exon 3 sequence was obtained from just one KR sample that was heterozygous for the exon (Fig. 2B, Supplemental Table 1E). However, it was unclear whether both exon 3 sequences shared the same, single exon 2 sequence obtained from the sample. Therefore, conservatively, we did not assign the unique exon 3 sequence a companion exon 2 sequence, and the exon 3 sequence was given the provisional allele name Papa-B*21:01 (Fig. 4, see Supplemental Fig. 1C for more detail).

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and allele frequency differences

We used Genepop v4.2 (Hardy Weinberg exact test, using probability test) to test for deviations between the observed genotype frequencies and those expected under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium for all 110 bonobos, as well as the five well-sampled populations. Genepop uses the Markov chain method to estimate p-values (47, 48). Differences in allele frequencies were tested with Fisher’s exact tests using Graphpad QuickCalcs.

Phylogeny, pairwise differences, and amino acid variability

Neighbor-joining trees of MHC-B nucleotide sequences were created using the Tamura-Nei model in MEGA6 (49), with pairwise deletion and 1,000 bootstrapped replications. MEGA6 was also used to calculate pairwise distances between nucleotide sequences, using pairwise deletion and p-distance. The difference between the mean p-distances was tested with unpaired t tests using GraphPad QuickCalcs. The Wu-Kabat Variability Coefficient (W) was used to assess the amino acid diversity at each position in the α1 and α2 domains of MHC-B (50, 51). For each position in the sequence, the coefficient was calculated as (N*k)/n, where N is the total number of sequences, k is the number of different amino acid residues occurring at that position, and n is the number of sequences in which the most common amino acid at that position is observed.

Additional MHC-B data sets

Several MHC-B data sets were used to examine bonobo Papa-B variation in context. More than 4,600 human HLA-B alleles have been identified in human populations worldwide, through the typing of prospective donors of hematopoietic stem cells for clinical transplantation (43). For our analyses the HLA-B dataset was reduced to a set of 20 HLA-B alleles that represent all human variation (Supplemental Table 1G) (Robinson et al. in revision). Fifteen Gogo-B alleles from Western gorilla (Gorilla gorilla) and 64 Patr-B alleles from chimpanzee were also included. Patr-B alleles were also identified as being specific to chimpanzee subspecies (Fig. 1A): western Pan troglodytes (P. t.) verus (Ptv) (21 alleles), central P. t. troglodytes (Ptt) (8 alleles), and eastern P. t. schweinfurthii (Pts) (16 alleles) (32). Patr-B in the fourth chimpanzee subspecies, P. t. ellioti (Pte), has yet to be studied.

Data sets of Patr-B from two chimpanzee populations were compared to Papa-B in bonobo populations. One population comprises the 125 wild Pts chimpanzees of Gombe National Park Tanzania (32). The other comprises 32 wild born Ptv chimpanzees from Sierra Leone that were used to found the captive population formerly housed at the Biomedical Primate Research Center (BPRC) in the Netherlands (31). HLA-B allele frequencies for six human populations were included in the comparisons. Four are indigenous populations: the Hadza from Tanzania (52), the Tao from Taiwan (53, 54), the Asaro from Papua New Guinea (55), and the Yucpa from Venezuela (56). The other two human populations are admixed urban populations: Africans from Kampala, Uganda (57) and Europeans from Bergamo, Italy (53, 54).

Results

Study of six separated bonobo populations identified 22 Papa-B alleles

We studied MHC variation in bonobos resident at six sites in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): Malebo (ML), Lui-Kotale (LK), Ikela (IK), Balanga (BN), Kokolopori (KR) and Bayandjo (BJ). These sites are between 30 and 1000 km apart and, collectively, they represent much of the bonobo range (Fig. 1). A total of 255 samples of bonobo feces were used to study Papa-B, the ortholog of chimpanzee Patr-B and human HLA-B. Only two fecal samples were obtained from site BJ, whereas 36–67 samples were collected from each of the other sites (Fig. 2A). Because almost all amino-acid sequence diversity and the sites of functional interaction localize to the α1 and α2 domains of MHC class I (6, 11), we targeted these domains of Papa-B. The methods used were those developed in our study of Patr-B polymorphism in the wild chimpanzee population of Gombe National Park in Tanzania (32).

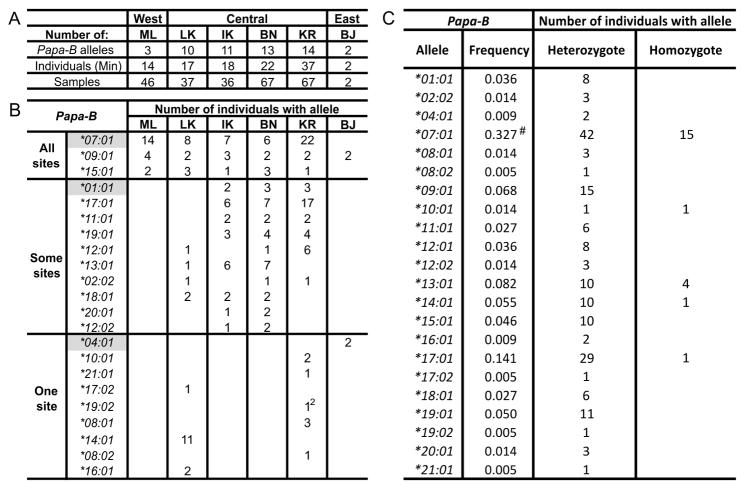

Figure 2. Summary of fecal sampling and Papa-B genotyping results.

(A) For each population is given: the number of Papa-B alleles; the minimum estimate of the number of individuals sampled, as determined by the combination of mitochondrial haplotypes and microsatellite and Papa-B genotypes (Individuals (Min)); and the number of fecal samples genotyped (Samples). West, Central and East denote the three regional bonobo populations, as defined by FST distances based on mitochondrial haplotype (70). (B) Distribution of Papa-B alleles among individuals in the six study sites. The alleles are grouped according to their presence in all sites (top), two or three sites (middle) and one site (bottom). Alleles found in a single individual at one site were detected either from one sample (1) or two (12). Previously identified Papa-B alleles are highlighted in gray. (C) Papa-B allele frequencies in the total study population of 110 bonobos are given in numerical order, along with the number of bonobos that possess the allele as heterozygotes or homozygotes. #Papa-B*07:01 is more frequent than the other alleles (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.0001). Papa-B*07:01 appears to have an excess of homozygotes, but this is because of the large number of homozygotes expected and observed in the ML population, which only has three Papa-B alleles.

Exon 2, encoding the α1 domain, and exon 3, encoding the α2 domain, were separately amplified by PCR from DNA isolated from bonobo feces and sequenced. By comparing the exon 2 and 3 sequences obtained from all 255 fecal samples, we could define, unambiguously, which combination of exon 2 and 3 is present in each Papa-B allele (Supplemental Fig. 1). This approach defined 22 different Papa-B alleles (Fig. 2). Three of these, Papa-B*01:01, -B*04:01 and -B*07:01, were known from earlier studies of very small numbers of captive bonobos (39, 41). Thus 19 of the Papa-B alleles identified here in wild bonobos are novel.

Because the identity of the individual bonobo providing each fecal sample is unknown, we cannot know precisely how many bonobos from each site contributed to our study. However, a minimum size for each population was obtained from the number of combined microsatellite genotypes, mitochondrial haplotypes, and Papa-B genotypes detected in the population (Fig. 2A, Supplemental Table 1A–F). In total we studied a minimum of 110 bonobos, a comparable number to the 125 Gombe chimpanzees studied for Patr-B (32). Between 14 and 37 bonobos were studied for each of the five well-represented sites, and the two BJ samples came from different individuals (Fig. 2A, Supplemental Table 1A–F). Although both BJ samples typed identically as heterozygous for Papa-B*04:01 and Papa-B*09:01, they differ in microsatellite genotype (Supplemental Table 1F). In subsequent comparative analyses we will use the word ‘populations’ to refer to the five well-represented sites.

Between 3 and 14 Papa-B alleles were identified in each of five bonobo populations (Fig. 2A). Eight of the Papa-B alleles were found in only one of the five populations (Fig. 2B). In addition, a ninth allele, Papa-B*04:01 was found only in the two BJ individuals (Fig. 2B). Ten of the Papa-B alleles were observed in two or three populations. In contrast, the Papa-B*07:01, -B*09:01, and -B*15:01 alleles were present in all five populations (Fig. 2B), and they were also among the most frequent Papa-B alleles (Fig. 2C), accounting for 44.1% of all Papa-B. With a frequency of 32.7%, Papa-B*07:01 has a significantly higher frequency than any other Papa-B allele (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.0001). The genotype frequencies, for each population and for their combination, conform to Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (Genepop v4.2, Hardy Weinberg exact test, using probability test) (Fig. 2C, Supplemental Table 1A–F). This result indicates that we have defined the common Papa-B alleles in the five populations, and that any undetected allele has relatively low frequency. That Papa-B*04:01 was found only in BJ samples, indicates that this Eastern population of bonobos likely harbors additional novel Papa-B alleles.

Bonobo and chimpanzee share a distinctive clade of MHC-B alleles

Phylogenetic trees constructed from hominid MHC-B sequences typically show shallow branches and little evidence for long-lived alleles or allelic lineages (27, 32) (Fig. 3A (exon 2) and Fig. 3B (exon 3), Supplemental Fig. 2). An exception is a deeper branch formed by the exon 2 sequences of a trans-species clade of chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes, Patr-B), western gorilla (Gorilla gorilla, Gogo-B), and human (Homo sapiens, Hosa, HLA-B) MHC-B alleles (28, 31, 32) (Fig. 3A, Supplemental Fig. 2). Defining this Hosa-Patr-Gogo clade (Clade 1) is a sequence motif in codons 62–74 of exon 2 (28, 32) (Fig. 3C, Supplemental Table 1H). Included in Clade 1 are human HLA-B*57:01 and chimpanzee Patr-B*06:03, alleles associated with control of the progression of HIV-1 and SIVcpz infection, respectively (31, 32, 58–63). Remarkably, no bonobo Papa-B allele clusters in this trans-species clade (Fig. 3A, Supplemental Fig. 2). Since this clade is predicted to have been present in the common ancestor of chimpanzee and bonobo, it appears to have been subsequently lost by the bonobo lineage. A possible factor contributing to this loss is that bonobos, unlike chimpanzees and humans, are not endemically infected with a primate lentivirus corresponding to chimpanzee SIVcpz and human HIV-1 (45, 64–67).

Figure 3. Two trans-species clades of MHC-B alleles.

Shown are neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees constructed from the sequences of exon 2 (A), which encodes the α1 domain, and exon 3 (B), which encodes the α2 domain. Included are all bonobo Papa-B, chimpanzee Patr-B, and gorilla Gogo-B alleles, and representative human HLA-B alleles. Allele names are colored blue for Papa-B and black for Patr-B. When known, Patr-B are colored according to subspecies: western Ptv (green), central Ptt (orange), and eastern Pts (red). Representative HLA-B alleles are in bold black and gorilla Gogo-B alleles in purple. Nodal bootstrap values are based on 1000 replications. Nodes with less than 50% support were collapsed (Full trees are shown in Supplemental Fig. 2.). The brackets in (A) show two trans-species clades of alleles. Clade 1 contains HLA-B, Patr-B, and Gogo-B alleles (Hosa-Patr-Gogo). Clade 1 was identified previously (28, 32) and contains alleles associated with control of HIV-1 progression (HLA-B*57:01) and SIVcpz (Patr-B*06:03) infection (31, 32, 58–63). Clade 2, defined in this study, includes HLA-B, Patr-B, Papa-B, and Gogo-B alleles (Hosa-Patr-Papa-Gogo). HLA-B*27:05, in Clade 2, also associates with control of HIV-1 progression (61), however its inclusion in the clade is supported weakly. HLA-B*27:05 differs from the clade Papa-B and Patr-B allotypes at key functional positions (63 and 70), which contribute to differences in their position 2 (P2) peptide-binding motif (C). Because arginine is the P2 residue of the HIV Gag KK10 epitope targeted by HLA-B*27:05 (80, 81), the associated protective effects of HLA-B*27:05 are unlikely to be preserved by Clade 2 bonobo and chimpanzee alleles, which are likely to bind peptides with P2 proline. (C) Table of amino-acid sequence differences in residues 45–74 of the MHC-B α1 domain. Representatives of each sequence motif within this region for the alleles of tree A are included in the upper part (The full allele set is given in Supplemental Table 1H.). Allotype names are colored according to species or subspecies, as in (A). Identity to the consensus is denoted by a dash. Highlighted in tan are the regions containing motifs that define Clade 1, positions 62–74 (28, 32) and Clade 2, positions 45–74 (Supplemental Fig. 3). Additional HLA-B sequences with the Clade 2 motif are given in the lower portion. Black-filled boxes between the two sets of sequences show which positions contribute to binding sites for peptide, TCR, and KIR. Positions 45, 63, 66, 67, and 70 contribute to the B pocket of the MHC-B molecule, which binds the anchor residue, typically at position 2 (P2), of nonamer peptides. Under “Anchor” are listed the P2 residues for each MHC-B allotype (compiled from the SYFPEITHI database of MHC ligands and peptide motifs, http://www.syfpeithi.de/ (82) and de Groot et al. (31)). MHC-B P2 residues that were inferred from known ligands are italicized and in gray.

Including Papa-B alleles in phylogenetic analysis of MHC-B revealed a second deep branch, Clade 2, that includes subsets of chimpanzee and bonobo MHC-B alleles (Fig. 3A, Supplemental Fig. 2). Defining Clade 2 is a sequence motif in codons 45–74 of exon 2 (Fig. 3C, Supplemental Fig. 3, Supplemental Table 1H). The key clade-defining residues are E45, M52, N63, A69 and Q70, as well as three alternative residues at position 67 (C, F or Y) (Fig. 3C, Supplemental Table 1H). HLA-B allotypes in this clade underwent species-specific divergence, changing M52 to I52. Several of the clade-defining residues contribute to the B pocket, which has a crucial role in binding peptides to MHC class I (68, 69). Comparing residues 45–74 of Clades 1 and 2 identifies eight positions of difference. The degree and pattern of sequence diversity within this region strongly suggests that Clade 1 and Clade 2 Papa-B bind distinct sets of peptide antigens, which also differ from those bound by other Papa-B (Fig. 3C, Supplemental Table 1H).

The Clade 2 Papa-B and Patr-B alleles represent a lineage of Pan-B alleles that was present in the common ancestor of bonobos and chimpanzees. Consistent with this hypothesis, Papa-B*07:01 and Papa-B*09:01, both Clade 2 members, are present in the five bonobo populations (Fig. 2). Likewise for the chimpanzee, Clade 2 alleles were identified in three chimpanzee subspecies: two in western Ptv, four in central Ptt, and two in eastern Pts (Fig. 3A). (Nothing is known of Patr-B in the fourth chimpanzee subspecies, Pte.) Further supporting our hypothesis, some Clade 2 bonobo and chimpanzee alleles have identical exon 2 sequences. Papa-B*08:01 shares exon 2 with Patr-B*12:02, and Papa-B*09:01 shares exon 2 with Patr-B*11:01 and Patr-B*11:02. It is most likely that the shared exons were inherited from the common ancestor of bonobo and chimpanzee. Of note, the exon 2 sequences of chimpanzee Patr-B*11:01 (28, 39), Patr-B*11:02 (27), and Patr-B*12:02 (27, 28), which are shared with bonobo, have been found only in Ptt, a chimpanzee subspecies whose range borders that of bonobo (Fig. 1).

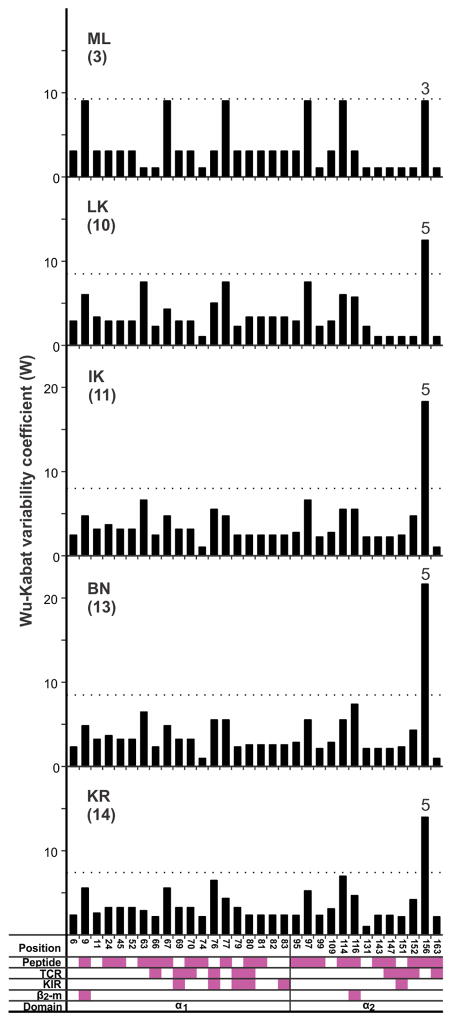

Common and widespread Papa-B allotypes carry the Bw4 and C1 epitopes

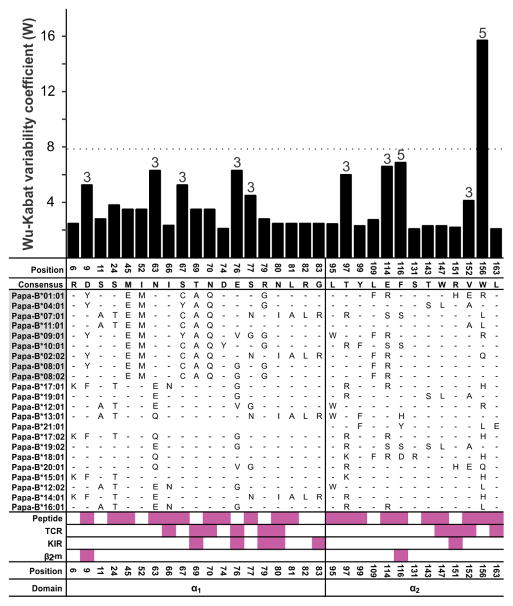

The peptide-binding domains of the 22 Papa-B allotypes differ at 32 positions of amino acid substitution (Fig. 4). This compares with 57 positions for Patr-B and 178 for HLA-B. Almost all these variable positions are associated with functional interactions of the α1 and α2 domains with peptide, TCR, KIR, and β2-microglobulin. The Papa-B α1 domain has more variable positions (N = 19) than the α2 domain (N = 13). Of the 32 variable positions, 22 are dimorphisms, eight are trimorphisms, and two display five alternative amino-acid residues (Fig. 4). The ten positions exhibiting more than two residues are evenly distributed between the two domains, but the α2 domain contains positions 116 and 156 that exhibit five alternative residues. Calculation of the Wu-Kabat coefficient of variability (50, 51) shows that position 156 has a much higher variability than all the other positions (Fig. 4, upper portion).

Figure 4. High amino acid sequence variability in Papa-B focuses on position 156 in the α2 domain.

Plotted in the upper panel is the coefficient of amino acid sequence variability, W, for Papa-B allotypes. Only polymorphic positions are shown. The horizontal dotted line marks the value of W that is twice the mean value for W at all polymorphic positions. For positions that are not dimorphisms, the observed number of alternative amino acids is given above the bar. The lower panel shows amino-acid sequence differences that distinguish the Papa-B allotypes. Identity to the consensus is denoted by a dash. Based on the criteria for phasing exon 2 and exon 3 sequences, Papa-B*21:01 could not be assigned an α1 (exon 2) sequence (see Materials and Methods for details) (Supplemental Fig. 1). Clade 2 allotypes (Hosa-Patr-Papa-Gogo) are highlighted in gray. Pink-filled boxes denote positions that contribute to binding sites for peptide, TCR, KIR, and β2-microglobulin (β2-m), the invariant subunit of MHC class I.

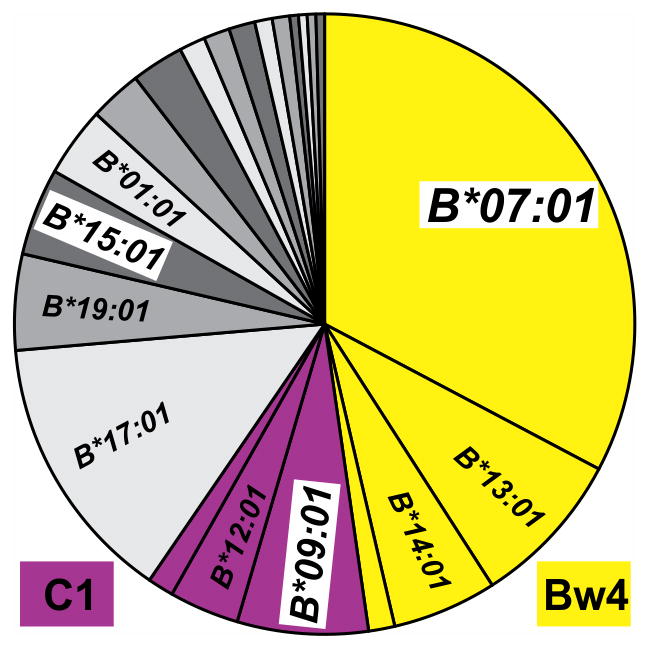

The Bw4 epitope recognized by KIR is defined by a sequence motif at positions 76–83 in the α1 domain (6, 11). Having this sequence motif are four bonobo allotypes: Papa-B*07:01, -B*02:02, -B*13:01, and -B*14:01 (Fig. 4). Together, they account for 47.7% of the Papa-B in the bonobo population (Fig. 2C, 5). The C1 epitope recognized by KIR is defined by a sequence motif at positions 76 and 80 in the α1 domain (6, 11). Having this motif are three bonobo allotypes: Papa-B*09:01, -B*12:01 and -B*20:01. These C1+ allotypes account for 11.8% of the Papa-B in the bonobo population. Papa-B*07:01 and Papa-B*09:01, both Clade 2 molecules and the most common Bw4+ and C1+ allotypes, respectively, are present in all five bonobo populations (Fig. 2, Supplemental Table 1A–F). Thus, we see a balance in bonobo populations between three types of Papa-B allotype: one having the Bw4 epitope, one having the C1 epitope, and one having neither epitope.

Figure 5. Pie chart of Papa-B allele frequencies in the study population of 110 bonobos.

Alleles encoding the Bw4 KIR ligand are colored yellow, and those encoding the C1 KIR ligand are colored purple. Alleles that do not encode a KIR ligand are in shades of gray. Alleles present at more than 3% in the population are labeled. Papa-B*07:01, B*09:01, and B*15:01, highlighted by white boxes, are present in all five well-sampled bonobo populations.

Bonobo Papa-B is less diverse than chimpanzee Patr-B and human HLA-B

Among the 546 nucleotides of exons 2 and 3, 58 exhibit nucleotide variation among the 22 Papa-B alleles. This number is comparable to 59 positions in eight Ptt Patr-B alleles but is lower than 86 positions present in 16 Pts Patr-B alleles, 91 in 21 Ptv Patr-B alleles, and 88 in 20 HLA-B alleles. These comparisons provided a first insight that Papa-B has more limited diversity than its orthologs in humans and chimpanzee subspecies.

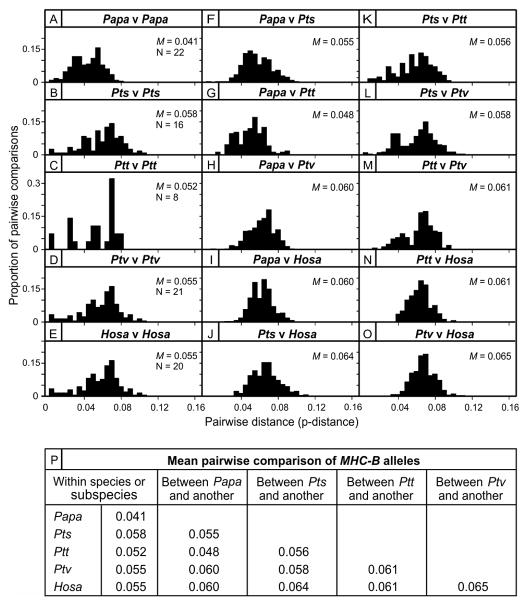

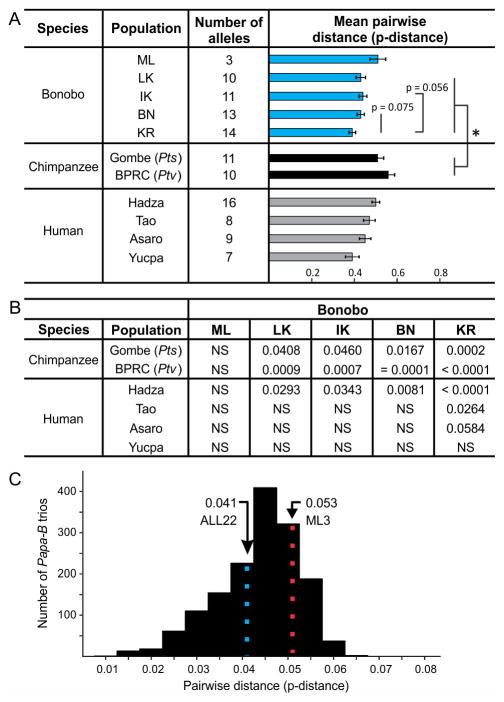

MHC-B diversity was further compared by analysis of the nucleotide differences (p-distance) between pairs of alleles from within each species or subspecies (Fig. 6). The mean p-distance of 0.041 for Papa-B (Fig. 6A) is significantly less than the mean p-distances for Pts-Patr-B (mean = 0.058, p < 0.0001, Fig. 6B), Ptt-Patr-B (mean = 0.052, p = 0.0015, Fig. 6C), Ptv-Patr-B (mean = 0.055, p < 0.0001, Fig. 6D), and HLA-B (mean = 0.055, p < 0.0001, Fig. 6E) (The statistical comparisons are also summarized in Supplemental Table 1I). Of note are the similar mean p-distances for humans and each chimpanzee subspecies.

Figure 6. Bonobo Papa-B has less nucleotide sequence diversity than chimpanzee Patr-B and human HLA-B.

(A-O) Within-group comparisons of p-distances for MHC-B alleles (exons 2 and 3) are plotted as histograms. (F-O) Between-group comparisons. Mean p-distances (M) are given in the individual panels (A-O) and are also summarized in panel (P); N gives the number of alleles (A-O). See Supplemental Table 1I for statistical results. Papa: Pan paniscus; Pts: Pan troglodytes (P. t.) schweinfurthii; Ptt: P. t. troglodytes; Ptv: P. t. verus; Hosa: Homo sapiens.

P-distances were also calculated for comparisons between one Papa-B allele and one chimpanzee or human MHC-B allele. Comparison with Pts-Patr-B gave a mean p-distance of 0.055 (Fig. 6F), compared to 0.048 with Ptt-Patr-B (Fig. 6G), 0.060 with Ptv-Patr-B (Fig. 6H), and 0.060 with HLA-B (Fig. 6I) (p < 0.0001 for both Papa-Pts-Patr and Papa-Ptt-Patr compared to Papa-Ptv-Patr, Supplemental Table 1I). This result shows that Papa-B is more similar to Pts-Patr-B and Ptt-Patr-B, the two chimpanzee subspecies whose range borders that of bonobos, than to Ptv chimpanzees. For inter-species comparisons involving one Papa-B allele, the range of mean p-distances is 0.048–0.60 (Fig. 6F–I), whereas that for inter-species comparisons not involving a Papa-B allele is 0.056–0.065 (Fig. 6J–O). A summary of the mean p-distances is given in Fig. 6P (Statistical comparisons are also summarized in Supplemental Table 1I.). Thus the nucleotide diversity of MHC-B in bonobo is significantly less than that in humans and three chimpanzee subspecies, and is significantly more similar to that in Ptt and Pts chimpanzees than Ptv chimpanzees.

Comparison of Wu-Kabat variability coefficients (50, 51) shows that Papa-B also has the lowest variability in amino acid sequence (Fig. 7). In Papa-B, only position 156 has high variability, having more than twice the mean (Fig. 4 (upper portion), 7A). This contrasts with six positions of high variability in Pts-Patr-B (Fig. 7B) and four in Ptv-Patr-B (Fig. 7C). Comparable differences are seen for human populations. The Hadza, hunter-gatherers from Tanzania (52) (Fig. 7D), Yucpa Amerindians (56) (Fig. 7F), and urban populations from Italy (53, 54) (Fig. 7G) and Uganda (57) (Fig. 7H) all have four highly variable positions, whereas the indigenous Taiwanese Tao population has only two (53, 54) (Fig. 7E). Like bonobos, position 156 is variable in Pts chimpanzees and dominated by nonpolar residues (Supplemental Table 1J). However, position 156 is approximately half as variable in Pts chimpanzees as it is in bonobos (Fig. 7A,B). This difference is because Papa-B has a balance between leucine (22.7%) and tryptophan (31.8%), whereas Patr-B is biased to leucine (66.7% in Ptv-Patr-B and 50% in Pts-Patr-B) (Supplemental Table 1J).

Figure 7. Comparison of MHC-B amino acid sequence variability in bonobo, chimpanzee, and humans.

Plots of the coefficient of amino-acid sequence variability, W, for MHC-B allotypes within bonobo (A), Pts chimpanzees (B), Ptv chimpanzees (C), three indigenous human populations (D-F), and two urban human populations (G,H). N gives the number of allotypes for each population. Black vertical bars represent positions with no sequence variability; gray bars represent dimorphic positions; and blue bars represent polymorphic positions. The horizontal dotted line is set at twice the mean value of W for all variable positions within a population. The pink-filled boxes show which positions contribute to binding sites for peptide, TCR, KIR, the invariant subunit β2-microglobulin (β2-m), and CD8 T-cell co-receptor (CD8). The Hadza (52), Tao (53, 54), and Yucpa (56) are indigenous populations from Africa (Tanzania), Asia (Taiwan), and South America (Venezuela), respectively; Bergamo and Kampala are admixed urban populations from Europe (Italy) and Africa (Uganda) (53, 54), respectively.

ML bonobos maintain considerable diversity with only three Papa-B alleles

On the basis of mitochondrial DNA sequence, it was previously suggested that bonobos subdivide into three geographically separate groups corresponding to the western, central and eastern areas of their range (70) (Fig. 1, 2A). Of the sites we studied, ML is western, LK, IK, BN, and KR are central, and BJ is eastern. Of the five well-represented sites, ML has only three Patr-B alleles compared to 10–14 alleles in the four central sites (Fig. 2A, 8A). The three Papa-B of ML bonobos represent distinct functional allotypes. Papa-B*07:01 has the Bw4 epitope, Papa-B*09:01 has the C1 epitope, and Papa-B*15:01 has neither epitope (Fig. 4, 5).

Figure 8. Comparison of Papa-B diversity in the five bonobo populations.

(A) Shown are the number of alleles and mean p-distances (+/− standard error of the mean) for MHC-B in the five bonobo populations and their comparison with chimpanzee and human populations. Representing chimpanzee are the wild Gombe Pts (32) and captive BPRC Ptv (31) populations. The p-values shown are from unpaired t tests. *Statistical results of comparisons between bonobo populations and those of chimpanzees and humans are given in (B). The indigenous human populations represent Africa (Hadza, Tanzania) (52), East Asia (Tao, Taiwan) (53, 54), Melanesia (Asaro, Papua New Guinea) (55), and South America (Yucpa, Venezuela) (56). (B) P-values from comparisons of the p-distances of populations in (A) (unpaired t tests). (C) Distribution of mean p-distances for all possible trios of Papa-B alleles that can be permuted from the set of 22 Papa-B (N = 1540). The colored, vertical and dotted lines show the means for all possible Papa-B trios (ALL22, blue dots) and for the three Papa-B alleles of the ML population (ML3, red dots).

ML bonobos maintain considerable nucleotide diversity as assessed by mean pairwise difference (p-distance). Papa-B diversity is highest in ML, of intermediate value in LK, IK and BN, and lowest in KR (Fig. 8A). Papa-B diversity in central bonobo populations is significantly less than Patr-B diversity in wild Pts Gombe chimpanzees (32) and a captive Ptv population (31) but comparable to HLA-B diversity in four indigenous human populations (Fig. 8A,B). In contrast, Papa-B diversity in ML is comparable to that of chimpanzee Patr-B and human HLA-B (Fig. 8A,B), and is higher than the mean diversity for all possible combinations of three Papa-B alleles (Fig. 8C). Differences in amino acid sequence diversity are also seen between the five bonobo populations. In the LK, IK, BN, and KR populations, position 156 stands out as the one highly variable position (Fig. 9), as also observed in the total bonobo population (Fig. 4 (upper portion), 7A). Although ML has only three Papa-B allotypes, each has a different residue at position 156 (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Comparison of Papa-B amino acid sequence variability in five bonobo populations.

Plots of the coefficient of amino-acid sequence variability, W, for the Papa-B allotypes of the five bonobo populations (numbers of allotypes are given in parentheses). The horizontal dotted line marks the value for W that is twice the mean W value for the polymorphic positions in each population. Above position 156 is given the number of alternative amino acid residues occurring at that position. The pink-filled boxes denote positions that contribute to binding sites for peptide, TCR, KIR, and the invariant subunit β2-microglobulin (β2-m).

The bonobo populations differ in the frequency distribution of their Papa-B alleles (Fig. 10). Most similar are the IK and BN bonobos (Fig. 10), living at closely located sites in the central range (Fig. 1). The frequency of Papa-B allotypes that have the Bw4 epitope is similar (36.4–41.7%) in the three most central sites (IK, BN, and KR), but is higher in the more western populations (67.6% in LK and 78.6% in ML) (Fig. 10A). The frequency of Papa-B allotypes having the C1 epitope is similar (8.8–11.4%) in four of the populations but noticeably higher in ML (14.3%). In all five populations the Papa-B*07:01 allele, encoding the Bw4 epitope, is the most frequent or the second most frequent Papa-B allele (Fig. 10B–C). In ML, the Papa-B*07:01 allele is particularly dominant (Fig. 10C). A less extreme dominance by one MHC-B allele is seen in the captive Ptv chimpanzee population, as well as the Hadza and Tao human populations (32) (Fig. 10C). Like the Gombe chimpanzees, the LK and KR bonobo populations have two high frequency alleles and a majority of low frequency alleles (32). In the IK and BN populations there is a less skewed distribution of allelic frequencies, similar to the urban human populations of Kampala and Bergamo (32).

Figure 10. MHC-B allele distribution in bonobo, chimpanzee, and human populations.

(A) Pie charts for each population showing the proportions of Papa-B alleles that encode the Bw4 epitope (shades of yellow) or the C1 epitope (shades of purple). Alleles not encoding Bw4 or C1 are shaded gray. Each pie segment corresponds to a different allele. Segments in different pies that have identical yellow or purple color denote the same allele, but alleles in the same shade of gray are not necessarily the same allele. Shown for each population are the frequencies, as percentages, for the alleles encoding an epitope recognized by KIR (Bw4 or C1) and alleles that encode neither epitope (None). (B) Pie charts for each population showing frequencies of the 22 Papa-B alleles. Each allele is defined by a different color that is maintained between pies. Segments are organized in order of decreasing frequency. (C) Comparison of the distributions of MHC-B allele frequency distributions in five bonobo populations (upper panels), two chimpanzee (lower panels, left), and four human populations (lower panels, right). The bars give the MHC-B allele frequencies in order of decreasing frequency (top to bottom). The bar graphs for the bonobo populations use the same color scheme to distinguish the Papa-B alleles as in (B). For the chimpanzee and human, each population is distinguished by bars of a different color, but within a population all alleles are colored identically. The Gombe chimpanzees are of the Pts subspecies (red) (32), and the BPRC population is of the Ptv subspecies (green) (31). HLA-B allele frequencies are also shown for the Hadza (52), Tao, Kampala, and Bergamo human populations (black) (53, 54). The Hadza and Tao are indigenous populations from Africa (Tanzania) and Asia (Taiwan), respectively; Kampala and Bergamo are admixed urban populations from Africa (Uganda) and Europe (Italy), respectively. N gives the number of individuals analyzed. Allele frequencies were compared using Fisher’s exact tests. The narrower black brackets (ML, BPRC, Hadza, Tao) show that the most common allele is significantly more frequent than the second-most common allele; the wider black brackets (KR, Gombe) show that the two most common alleles are significantly more frequent than the third-most common allele, but do not differ significantly from each other (p-values given below the bracket (p < 0.0001 applies to both high-frequency Gombe alleles)). In LK, the most common allele is significantly more frequent than the third-most common allele; gray brackets (LK, KR) note alleles that were of nearly significantly different frequencies (p-values < 0.1).

Discussion

Bonobos and chimpanzees are sibling species and humans’ closest relatives (36). These great apes are invaluable for understanding all aspects of human evolution. This is particularly true for the highly polymorphic MHC class I genes that function in innate immunity, adaptive immunity, and reproduction (6, 11). Strict orthologs of all the classical human MHC class I genes (HLA-A, -B and -C) are present only in great apes (10). Moreover, it is in chimpanzee and bonobo that the organization of the MHC class I gene family is most like that of humans (10, 11, 38). Although there has been steady acquisition of knowledge of the chimpanzee MHC since the late 1980s (10, 27, 28, 71, 72), next to nothing is known about the bonobo MHC (10, 38–42). Emphasizing this paucity, the numbers of MHC-B sequences currently deposited in MHC databases are eight for bonobo, 64 for chimpanzee, and 4,647 for human (43, 44). The eight Papa-B sequences were derived from captive bonobos of unknown provenance (39, 41).

In contrast, we have studied Papa-B in six populations of wild-living bonobos (45). This approach enabled us to study the polymorphism of Papa-B and place it in the context of the bonobo’s natural population structure. In studying at least 110 individuals, we identified 22 Papa-B alleles among the six populations. This number compares to the 11 Patr-B alleles present in 125 chimpanzees, forming three communities, in Gombe National Park of Tanzania (32) (Fig. 1). The set of Papa-B alleles is less diverse than comparable sets of HLA-B and Patr-B alleles, and this holds true even when Patr-B are limited to those alleles of a single chimpanzee subspecies. Our results are consistent with whole genome comparisons, which concluded that bonobos experienced a severe population bottleneck and consequently exhibit a strong signature of inbreeding (36).

Phylogenetic analysis identified two trans-species clades of MHC-B, which are defined by sequence motifs in part of the antigen recognition site contributed by the α1 domain. The Pan clade (Clade 2) is broadly conserved among African apes, including some Papa-B of bonobo and Patr-B of the three chimpanzee subspecies studied. The other trans-species MHC-B clade (Clade 1), which includes some human, chimpanzee, and gorilla MHC-B alleles (28, 32), correlates with resistance to disease progression of human HIV-1 (HLA-B*57:01) and chimpanzee SIV (Patr-B*06:03) infections (31, 32, 58–63). However, none of the 22 Papa-B alleles are a part of Clade 1. This absence could be due to insufficient sampling of bonobo populations. In this regard it is unfortunate that we had only two samples from the BJ site. This population is separated from the other populations by the Lomami River (Fig. 1B), which is a known barrier to bonobo gene flow (70, 73). The possibility of BJ bonobos having Papa-B alleles that eluded our analysis is likely because Papa-B*04:01 was found only in the two BJ bonobos. A relevant and intriguing fact is that SIV has never been detected in bonobos, either in the wild or captivity (45, 74). In contrast, two of the four chimpanzee subspecies (Fig. 1A), Ptt and Pts, have endemic SIVcpz infection (65). It is possible that Clade 1 Papa-B alleles are present at low frequency within bonobos in absence of pressure from SIV infection to drive them to higher frequency. Alternatively, Clade 1 was present in the common ancestor of chimpanzee and bonobo but was subsequently lost on the bonobo branch.

The ML population provides an informative example of a population bottleneck in bonobos. Of similar size to the LK and IK populations, ML has only three Papa-B alleles compared to 10 in LK and 11 in IK. For comparison, the South Amerindian Yucpa, a small and bottlenecked human population, has seven HLA-B alleles (56). One important characteristic of the three ML Papa-B allotypes (Papa-B*07:01, -B*09:01, and -B*15:01) is that they are the only Papa-B present in all five well-sampled study populations. A second important characteristic is that they represent three functionally distinctive groups of Papa-B. Papa-B*07:01 has the Bw4 epitope recognized by KIR (6, 11). Papa-B*09:01 carries the C1 epitope, also recognized by KIR (6, 11). In contrast, Papa-B*15:01 has neither Bw4 nor C1 and is thus dedicated to presenting peptide antigens to the antigen receptors of CD8 T cells. Their presence in all populations and retention through the bottleneck experienced by ML bonobos indicate that this combination of three Papa-B allotypes has been essential for the survival of bonobo populations. Supporting this hypothesis, the sequence differences between these allotypes give ML bonobos the highest nucleotide diversity of the five populations. Moreover, this diversity is higher than the mean p-distance of all possible combinations of three Papa-B alleles.

Conservation of Bw4 and C1 in the five bonobo populations points to the importance that interactions of these epitopes with KIR could have in the education and immune response of bonobo NK cells (6, 11). Comparison of the human and chimpanzee KIR families identified similarities in their component KIR but differences in the organization of the KIR locus (11, 35). Chimpanzee KIR haplotypes are variations on a theme of multiple strong inhibitory HLA-C receptors (33, 35). In contrast, the human KIR locus has two distinctive forms, which are present and balanced in all human populations (6, 56). Human KIR A haplotypes are similar to chimpanzee KIR, whereas human KIR B haplotypes have genes encoding additional activating KIR and weaker inhibitory KIR (6, 22, 35). The KIR A and B haplotype difference influences NK cell responses and correlates with a wide range of infectious and inflammatory diseases, as well as pregnancy syndromes and outcomes of clinical therapies, notably hematopoietic cell transplantation (25, 26, 75–79). A first analysis of the bonobo KIR region showed it is different again from both the chimpanzee and the human KIR loci (37).

Bonobo KIR haplotypes form two distinctive groups, with even frequency in the cohort of nine captive bonobos studied (37). One haplotype group resembles chimpanzee KIR haplotypes (11, 35, 37). The other group has contracted in size, leaving only the conserved framework genes that define the ends and the center of the KIR locus (37). Missing are the genes that, in humans, encode the KIR that recognize Bw4 and C1. This division of bonobo KIR haplotypes into two qualitatively different groups parallels the division of the human KIR locus into A and B haplotypes (11, 37) and contrasts with the chimpanzee KIR locus (11, 35). In humans there is increasing evidence that the KIR A and KIR B haplotype difference evolved as a compromise between NK cell functions in immunity and reproduction (6, 22). That could also be the case for the bonobo KIR haplotype groups. The considerable insight gained from this population study of one bonobo MHC class I gene makes targeted capture and next generation sequencing of entire bonobo MHC and KIR regions an exciting proposition. A method for such analysis of human HLA and KIR has proved applicable to chimpanzee and should also apply to bonobo (20) (Norman et al. in revision).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

For permission to collect samples in the DRC we thank the Ministry of Scientific Research and Technology, the Department of Ecology and Management of Plant and Animal Resources of the University of Kisangani, the Ministries of Health and Environment, and the National Ethics committee. We thank the staff of the World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF/DRC), the Institut National de Recherches Biomédicales (INRB, Kinshasa, DRC), Didier Mazongo, Octavie Lunguya, Muriel Aloni, and Valentin Mbenz for samples from Malebo, DRC. We thank Bonobo Conservation Initiative and Vie Sauvage for assistance and facilitation of sample collection at Kokolopori. We also thank Yerkes National Primate Research Center for providing samples used in the methodological validation of this study.

Footnotes

The bonobo MHC genetic data generation and analysis, as well as the microsatellite genotyping for ML, BN, and BJ bonobos, was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI24258, R01 AI31168). All other bonobo sample and data collection was primarily supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R37 AI050529, R01 AI120810, R01 AI091595, and P30 AI045008), the Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le SIDA (ANRS), France (grants N° ANRS 12182, ANRS 12555, and ANRS 12325), and the Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), France. Sample collection at Kokolopori was also supported by Harvard University and the Arthur L. Greene Fund. Samples received from Yerkes National Primate Research Center were collected with funding from ORIP/OD P51 OD011132.

All sequences were submitted to the GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) and Immuno Polymorphism (IPD) (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ipd/mhc/) databases, with allele names, except Papa-B*21:01, assigned by IPD (GenBank accession numbers: Papa-B*17:01 (KX786188), Papa-B*11:01 (KX786189), Papa-B*19:01 (KX786190), Papa-B*09:01 (KX786191), Papa-B*12:01 (KX786192), Papa-B*13:01 (KX786193), Papa-B*10:01 (KX786194), Papa-B*21:01 (KX786195), Papa-B*17:02 (KX786196), Papa-B*19:02 (KX786197), Papa-B*02:02 (KX786198), Papa-B*08:01 (KX786199), Papa-B*18:01 (KX786200), Papa-B*20:01 (KX786201), Papa-B*15:01 (KX786202), Papa-B*12:02 (KX786203), Papa-B*14:01 (KX786204), Papa-B*08:02 (KX786205), Papa-B*16:01 (KX786206).

Abbreviations used in this article: β2-m, beta-2 microglobulin; BPRC, Biomedical Primate Research Center; DRC, Democratic Republic of Congo; Gogo, Gorilla gorilla; Hosa, Homo sapiens; KIR, killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor; Papa, Pan paniscus; Patr, Pan troglodytes; Pts, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii; Ptt, Pan troglodytes troglodytes; Ptv, Pan troglodytes verus

References

- 1.Kelley J, Walter L, Trowsdale J. Comparative genomics of major histocompatibility complexes. Immunogenetics. 2005;56:683–695. doi: 10.1007/s00251-004-0717-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown JH, Jardetzky T, Saper MA, Samraoui B, Bjorkman PJ, Wiley DC. A hypothetical model of the foreign antigen binding site of Class II histocompatibility molecules. Nature. 1988;332:845–850. doi: 10.1038/332845a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villadangos JA. Presentation of antigens by MHC class II molecules: getting the most out of them. Mol Immunol. 2001;38:329–346. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(01)00069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colonna M, Samaridis J. Cloning of immunoglobulin-superfamily members associated with HLA-C and HLA-B recognition by human natural killer cells. Science. 1995;268:405–408. doi: 10.1126/science.7716543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zinkernagel RM, Doherty PC. Restriction of in vitro T cell-mediated cytotoxicity in lymphocytic choriomeningitis within a syngeneic or semiallogeneic system. Nature. 1974;248:701–702. doi: 10.1038/248701a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parham P, Moffett A. Variable NK cell receptors and their MHC class I ligands in immunity, reproduction and human evolution. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:133–144. doi: 10.1038/nri3370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein J, Figueroa F. Evolution of the major histocompatibility complex. Crit Rev Immunol. 1985;6:295–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes AL, Nei M. Evolution of the major histocompatibility complex: independent origin of nonclassical class I genes in different groups of mammals. Mol Biol Evol. 1989;6:559–579. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi K, Rooney A, Nei M. Origins and divergence times of mammalian class II MHC gene clusters. J Hered. 2000;91:198–204. doi: 10.1093/jhered/91.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams EJ, Parham P. Species-specific evolution of MHC class I genes in the higher primates. Immunol Rev. 2001;183:41–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1830104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guethlein LA, Norman PJ, Hilton HG, Parham P. Co-evolution of MHC class I and variable NK cell receptors in placental mammals. Immunol Rev. 2015;267:259–282. doi: 10.1111/imr.12326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wan AM, Ennis P, Parham P, Holmes N. The primary structure of HLA-A32 suggests a region involved in formation of the Bw4/Bw6 epitopes. J Immunol. 1986;137:3671–3674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyington JC, Sun PD. A structural perspective on MHC class I recognition by killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors. Mol Immunol. 2002;38:1007–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colonna M, Borsellino G, Falco M, Ferrara GB, Strominger JL. HLA-C is the inhibitory ligand that determines dominant resistance to lysis by NK1-and NK2-specific natural killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:12000–12004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.12000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winter CC, Long EO. A single amino acid in the p58 killer cell inhibitory receptor controls the ability of natural killer cells to discriminate between the two groups of HLA-C allotypes. J Immunol. 1997;158:4026–4028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gumperz JE, Litwin V, Phillips JH, Lanier LL, Parham P. The Bw4 public epitope of HLA-B molecules confers reactivity with natural killer cell clones that express NKB1, a putative HLA receptor. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1133–1144. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biassoni R, Falco M, Cambiaggi A, Costa P, Verdiani S, Pende D, Conte R, Di Donato C, Parham P, Moretta L. Amino acid substitutions can influence the natural killer (NK)-mediated recognition of HLA-C molecules. Role of serine-77 and lysine-80 in the target cell protection from lysis mediated by” group 2” or” group 1” NK clones. J Exp Med. 1995;182:605–609. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malnati MS, Peruzzi M, Parker KC, Biddison WE. Peptide specificity in the recognition of MHC class I by natural killer cell clones. Science. 1995;267:1016–1018. doi: 10.1126/science.7863326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajagopalan S, Long EO. The direct binding of a p58 killer cell inhibitory receptor to human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-Cw4 exhibits peptide selectivity. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1523–1528. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.8.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norman PJ, Hollenbach JA, Nemat-Gorgani N, Marin WM, Norberg SJ, Ashouri E, Jayaraman J, Wroblewski EE, Trowsdale J, Rajalingam R. Defining KIR and HLA class I genotypes at highest resolution via high-throughput sequencing. Am J Hum Gen. 2016;99:375–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graef T, Moesta AK, Norman PJ, Abi-Rached L, Vago L, Aguilar AMO, Gleimer M, Hammond JA, Guethlein LA, Bushnell DA. KIR2DS4 is a product of gene conversion with KIR3DL2 that introduced specificity for HLA-A* 11 while diminishing avidity for HLA-C. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2557–2572. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hilton HG, Norman PJ, Nemat-Gorgani N, Goyos A, Hollenbach JA, Henn BM, Gignoux CR, Guethlein LA, Parham P. Loss and gain of natural killer cell receptor function in an African hunter-gatherer population. PLOS Genet. 2015;11:e1005439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trowsdale J, Knight JC. Major histocompatibility complex genomics and human disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2013;14:301–323. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin MP, Carrington M. Immunogenetics of HIV disease. Immunol Rev. 2013;254:245–264. doi: 10.1111/imr.12071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kulkarni S, Martin MP, Carrington M. The Yin and Yang of HLA and KIR in human disease. Sem Immunol. 2008;20:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khakoo SI, Carrington M. KIR and disease: a model system or system of models? Immunol Rev. 2006;214:186–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams EJ, Cooper S, Thomson G, Parham P. Common chimpanzees have greater diversity than humans at two of the three highly polymorphic MHC class I genes. Immunogenetics. 2000;51:410–424. doi: 10.1007/s002510050639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Groot NG, Otting N, Argüello R, Watkins DI, Doxiadis GGM, Madrigal JA, Bontrop RE. Major histocompatibility complex class-I diversity in a West African chimpanzee population: implications for HIV research. Immunogenetics. 2000;51:398–409. doi: 10.1007/s002510050638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams E, Parham P. Genomic analysis of common chimpanzee major histocompatibility complex class I genes. Immunogenetics. 2001;53:200–208. doi: 10.1007/s002510100318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Groot NG, Otting N, Doxiadis GG, Balla-Jhagjhoorsingh SS, Heeney JL, van Rood JJ, Gagneux P, Bontrop RE. Evidence for an ancient selective sweep in the MHC class I gene repertoire of chimpanzees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11748–11753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182420799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Groot NG, Heijmans CMC, Zoet YM, de Ru AH, Verreck FA, van Veelen PA, Drijfhout JW, Doxiadis GGM, Remarque EJ, Doxiadis IIN, van Rood JJ, Koning F, Bontrop RE. AIDS-protective HLA-B*27/B*57 and chimpanzee MHC class I molecules target analogous conserved areas of HIV-1/SIVcpz. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15175–15180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009136107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wroblewski EE, Norman PJ, Guethlein LA, Rudicell RS, Ramirez MA, Li Y, Hahn BH, Pusey AE, Parham P. Signature patterns of MHC diversity in three Gombe communities of wild chimpanzees reflect fitness in reproduction and immune defense against SIVcpz. PLOS Biol. 2015;13:e1002144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moesta AK, Abi-Rached L, Norman PJ, Parham P. Chimpanzees use more varied receptors and ligands than humans for inhibitory killer cell Ig-like receptor recognition of the MHC-C1 and MHC-C2 epitopes. J Immunol. 2009;182:3628–3637. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moesta AK, Graef T, Abi-Rached L, Aguilar AMO, Guethlein LA, Parham P. Humans differ from other hominids in lacking an activating NK cell receptor that recognizes the C1 epitope of MHC class I. J Immunol. 2010;185:4233–4237. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abi-Rached L, Moesta AK, Rajalingam R, Guethlein LA, Parham P. Human-specific evolution and adaptation led to major qualitative differences in the variable receptors of human and chimpanzee natural killer cells. PLOS Genet. 2010;6:e1001192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prado-Martinez J, Sudmant PH, Kidd JM, Li H, Kelley JL, Lorente-Galdos B, Veeramah KR, Woerner AE, O/’Connor TD, Santpere G, Cagan A, Theunert C, Casals F, Laayouni H, Munch K, Hobolth A, Halager AE, Malig M, Hernandez-Rodriguez J, Hernando-Herraez I, Prufer K, Pybus M, Johnstone L, Lachmann M, Alkan C, Twigg D, Petit N, Baker C, Hormozdiari F, Fernandez-Callejo M, Dabad M, Wilson ML, Stevison L, Camprubi C, Carvalho T, Ruiz-Herrera A, Vives L, Mele M, Abello T, Kondova I, Bontrop RE, Pusey A, Lankester F, Kiyang JA, Bergl RA, Lonsdorf E, Myers S, Ventura M, Gagneux P, Comas D, Siegismund H, Blanc J, Agueda-Calpena L, Gut M, Fulton L, Tishkoff SA, Mullikin JC, Wilson RK, Gut IG, Gonder MK, Ryder OA, Hahn BH, Navarro A, Akey JM, Bertranpetit J, Reich D, Mailund T, Schierup MH, Hvilsom C, Andres AM, Wall JD, Bustamante CD, Hammer MF, Eichler EE, Marques-Bonet T. Great ape genetic diversity and population history. Nature. 2013;499:471–475. doi: 10.1038/nature12228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajalingam R, Hong M, Adams EJ, Shum BP, Guethlein LA, Parham P. Short KIR haplotypes in pygmy chimpanzee (Bonobo) resemble the conserved framework of diverse human KIR haplotypes. J Exp Med. 2001;193:135–146. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.1.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper S, Adams EJ, Wells RS, Walker CM, Parham P. A major histocompatibility complex class I allele shared by two species of chimpanzee. Immunogenetics. 1998;47:212–217. doi: 10.1007/s002510050350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McAdam SN, Boyson JE, Liu X, Garber TL, Hughes AL, Bontrop RE, Watkins DI. A uniquely high level of recombination at the HLA-B locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5893–5897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McAdam SN, Boyson JE, Liu X, Garber TL, Hughes AL, Bontrop RE, Watkins DI. Chimpanzee MHC class IA locus alleles are related to only one of the six families of human A locus alleles. J Immunol. 1995;154:6421–6429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martínez-Laso J, Gómez-Casado E, Arnaiz-Villena A. Description of seven new non-human primate MHC-B alleles. Tissue Antigens. 2006;67:85–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2005.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawlor DA, Edelson BT, Parham P. MHC-A locus molecules in pygmy chimpanzees: conservation of peptide pockets. Immunogenetics. 1995;42:291–295. doi: 10.1007/BF00176447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson J, Halliwell JA, Hayhurst JD, Flicek P, Parham P, Marsh SG. The IPD and IMGT/HLA database: allele variant databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;43:D423–D431. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson J, Halliwell JA, McWilliam H, Lopez R, Marsh SG. IPD—the immuno polymorphism database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;41:D1234–D1240. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y, Ndjango JB, Learn GH, Ramirez MA, Keele BF, Bibollet-Ruche F, Liu W, Easlick JL, Decker JM, Rudicell RS. Eastern chimpanzees, but not bonobos, represent a simian immunodeficiency virus reservoir. J Virol. 2012;86:10776–10791. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01498-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sullivan KM, Mannucci A, Kimpton CP, Gill P. A rapid and quantitative DNA sex test: fluorescence-based PCR analysis of XY homologous gene amelogenin. Biotechniques. 1993;15:636–638. 640–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raymond M, Rousset F. GENEPOP (version 1.2): population genetics software for exact tests and ecumenicism. J Hered. 1995;86:248–249. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rousset F. genepop’007: a complete re-implementation of the genepop software for Windows and Linux. Mol Ecol Resour. 2008;8:103–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kabat E, Wu T, Bilofsky H. Unusual distributions of amino acids in complementarity-determining (hypervariable) segments of heavy and light chains of immunoglobulins and their possible roles in specificity of antibody-combining sites. J of Biol Chem. 1977;252:6609–6616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu TT, Kabat EA. An analysis of the sequences of the variable regions of Bence Jones proteins and myeloma light chains and their implications for antibody complementarity. J Exp Med. 1970;132:211–250. doi: 10.1084/jem.132.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Henn BM, Gignoux CR, Jobin M, Granka JM, Macpherson J, Kidd JM, Rodríguez-Botigué L, Ramachandran S, Hon L, Brisbin A. Hunter-gatherer genomic diversity suggests a southern African origin for modern humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:5154–5162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017511108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gonzalez-Galarza FF, Christmas S, Middleton D, Jones AR. Allele frequency net: a database and online repository for immune gene frequencies in worldwide populations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D913–D919. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.González-Galarza FF, Takeshita LY, Santos EJ, Kempson F, Maia MHT, da Silva ALS, e Silva ALT, Ghattaoraya GS, Alfirevic A, Jones AR. Allele frequency net 2015 update: new features for HLA epitopes, KIR and disease and HLA adverse drug reaction associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;43:D784–D788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Main P, Attenborough R, Chelvanayagam G, Gao X. The peopling of New Guinea: evidence from class I human leukocyte antigen. Hum Biol. 2001:365–383. doi: 10.1353/hub.2001.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gendzekhadze K, Norman PJ, Abi-Rached L, Graef T, Moesta AK, Layrisse Z, Parham P. Co-evolution of KIR2DL3 with HLA-C in a human population retaining minimal essential diversity of KIR and HLA class I ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18692–18697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906051106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kijak G, Walsh A, Koehler R, Moqueet N, Eller L, Eller M, Currier J, Wang Z, Wabwire-Mangen F, Kibuuka H. HLA class I allele and haplotype diversity in Ugandans supports the presence of a major east African genetic cluster. Tissue Antigens. 2009;73:262–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2008.01192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kiepiela P, Leslie AJ, Honeyborne I, Ramduth D, Thobakgale C, Chetty S, Rathnavalu P, Moore C, Pfafferott KJ, Hilton L. Dominant influence of HLA-B in mediating the potential co-evolution of HIV and HLA. Nature. 2004;432:769–775. doi: 10.1038/nature03113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Migueles SA, Sabbaghian MS, Shupert WL, Bettinotti MP, Marincola FM, Martino L, Hallahan CW, Selig SM, Schwartz D, Sullivan J. HLA B* 5701 is highly associated with restriction of virus replication in a subgroup of HIV-infected long term nonprogressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2709–2714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050567397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gao X, Bashirova A, Iversen AK, Phair J, Goedert JJ, Buchbinder S, Hoots K, Vlahov D, Altfeld M, O’Brien SJ. AIDS restriction HLA allotypes target distinct intervals of HIV-1 pathogenesis. Nat Med. 2005;11:1290–1292. doi: 10.1038/nm1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaslow R, Carrington M, Apple R, Park L, Munoz A, Saah A, Goedert J, Winkler C, O’brien S, Rinaldo C. Influence of combinations of human major histocompatibility complex genes on the course of HIV–1 infection. Nat Med. 1996;2:405–411. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pereyra F, Addo MM, Kaufmann DE, Liu Y, Miura T, Rathod A, Baker B, Trocha A, Rosenberg R, Mackey E. Genetic and immunologic heterogeneity among persons who control HIV infection in the absence of therapy. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:563–571. doi: 10.1086/526786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Altfeld M, Addo MM, Rosenberg ES, Hecht FM, Lee PK, Vogel M, Xu GY, Draenert R, Johnston MN, Strick D. Influence of HLA-B57 on clinical presentation and viral control during acute HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2003;17:2581–2591. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200312050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Keele BF, Van Heuverswyn F, Li Y, Bailes E, Takehisa J, Santiago ML, Bibollet-Ruche F, Chen Y, Wain LV, Liegeois F, Loul S, Ngole EM, Bienvenue Y, Delaporte E, Brookfield JF, Sharp PM, Shaw GM, Peeters M, Hahn BH. Chimpanzee reservoirs of pandemic and nonpandemic HIV-1. Science. 2006;313:523–526. doi: 10.1126/science.1126531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sharp PM, Hahn BH. Origins of HIV and the AIDS pandemic. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011;1:a006841. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Van Heuverswyn F, Li Y, Bailes E, Neel C, Lafay B, Keele BF, Shaw KS, Takehisa J, Kraus MH, Loul S. Genetic diversity and phylogeographic clustering of SIVcpzPtt in wild chimpanzees in Cameroon. Virology. 2007;368:155–171. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Santiago ML, Rodenburg CM, Kamenya S, Bibollet-Ruche F, Gao F, Bailes E, Meleth S, Soong SJ, Kilby JM, Moldoveanu Z, Fahey B, Muller MN, Ayouba A, Nerrienet E, McClure HM, Heeney JL, Pusey AE, Collins DA, Boesch C, Wrangham RW, Goodall J, Sharp PM, Shaw GM, Hahn BH. SIVcpz in Wild Chimpanzees. Science. 2002;295:465. doi: 10.1126/science.295.5554.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bjorkman PJ, Saper MA, Samraoui B, Bennett WS, Strominger JL, Wiley DC. The foreign antigen binding site and T cell recognition regions of class I histocompatibility antigens. Nature. 1987;329:512–518. doi: 10.1038/329512a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Madden DR. The three-dimensional structure of peptide-MHC complexes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:587–622. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.003103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kawamoto Y, Takemoto H, Higuchi S, Sakamaki T, Hart JA, Hart TB, Tokuyama N, Reinartz GE, Guislain P, Dupain J. Genetic structure of wild bonobo populations: diversity of mitochondrial DNA and geographical distribution. PLOS One. 2013;8:e59660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mayer W, Jonker M, Klein D, Ivanyi P, Van Seventer G, Klein J. Nucleotide sequences of chimpanzee MHC class I alleles: evidence for trans-species mode of evolution. EMBO J. 1988;7:2765–2774. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lawlor DA, Ward FE, Ennis PD, Jackson AP, Parham P. HLA-A and B polymorphisms predate the divergence of humans and chimpanzees. Nature. 1988;335:268–271. doi: 10.1038/335268a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eriksson J, Hohmann G, Boesch C, Vigilant L. Rivers influence the population genetic structure of bonobos (Pan paniscus) Mol Ecol. 2004;13:3425–3435. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Van Dooren S, Switzer WM, Heneine W, Goubau P, Verschoor E, Parekh B, De Meurichy W, Furley C, Van Ranst M, Vandamme AM. Short Communication: Lack of Evidence for Infection with Simian Immunodeficiency Virus in Bonobos. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2002;18:213–216. doi: 10.1089/08892220252781275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nakimuli A, Chazara O, Hiby SE, Farrell L, Tukwasibwe S, Jayaraman J, Traherne JA, Trowsdale J, Colucci F, Lougee E. A KIR B centromeric region present in Africans but not Europeans protects pregnant women from pre-eclampsia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:845–850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413453112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moffett A, Hiby SE, Sharkey AM. The role of the maternal immune system in the regulation of human birthweight. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2015;370:20140071. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hiby SE, Walker JJ, O’Shaughnessy KM, Redman CW, Carrington M, Trowsdale J, Moffett A. Combinations of maternal KIR and fetal HLA-C genes influence the risk of preeclampsia and reproductive success. J Exp Med. 2004;200:957–965. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cooley S, Trachtenberg E, Bergemann TL, Saeteurn K, Klein J, Le CT, Marsh SG, Guethlein LA, Parham P, Miller JS. Donors with group B KIR haplotypes improve relapse-free survival after unrelated hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2009;113:726–732. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-171926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cooley S, Weisdorf DJ, Guethlein LA, Klein JP, Wang T, Marsh SG, Spellman S, Haagenson MD, Saeturn K, Ladner M. Donor killer cell Ig-like receptor B haplotypes, recipient HLA-C1, and HLA-C mismatch enhance the clinical benefit of unrelated transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. J Immunol. 2014;192:4592–4600. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Goulder PJR, Phillips RE, Colbert RA, McAdam S, Ogg G, Nowak MA, Giangrande P, Luzzi G, Morgan B, Edwards A, McMichael AJ, Rowland-Jones S. Late escape from an immunodominant cytotoxic T lymphocyte response associated with progression to AIDS. Nat Med. 1997;3:212–217. doi: 10.1038/nm0297-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nixon DF, Townsend AR, Elvin JG, Rizza CR, Gallwey J, McMichael AJ. HIV-1 gag-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes defined with recombinant vaccinia virus and synthetic peptides. Nature. 1988;336:484–487. doi: 10.1038/336484a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rammensee HG, Bachmann J, Emmerich NPN, Bachor OA, Stevanović S. SYFPEITHI: database for MHC ligands and peptide motifs. Immunogenetics. 1999;50:213–219. doi: 10.1007/s002510050595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.