Abstract

Disclosure of HIV-positive status has important implications for patient outcomes and preventing HIV transmission, but has been understudied in TB-HIV patients. We assessed disclosure patterns and correlates of non-disclosure among adult TB-HIV patients initiating ART enrolled in the START Study, a mixed-methods cluster-randomized trial conducted in Lesotho, which evaluated a combination intervention package (CIP) versus standard of care. Interviewer-administered questionnaire data were analyzed to describe patterns of disclosure. Patient-related factors were assessed for association with non-disclosure to anyone other than a healthcare provider and primary partners using generalized linear mixed models. Among 371 participants, 95% had disclosed their HIV diagnosis to someone other than a healthcare provider, most commonly a spouse/primary partner (76%). Age, TB knowledge, not planning to disclose TB status, greater perceived TB stigma, and CIP were associated with non-disclosure in unadjusted models (p<0.1). In adjusted models, all point estimates were similar and greater TB knowledge (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.59 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.39–0.90) and CIP (aOR 0.20, 95% CI 0.05–0.79) remained statistically significant. Among 220 participants with a primary partner, 76% had disclosed to that partner. Significant correlates of partner non-disclosure (p<0.1) in unadjusted analyses included being female, married/cohabitating, electricity at home, not knowing if partner was HIV-positive, and TB knowledge. Adjusted point estimates were largely similar, and being married/cohabitating (aOR 0.03, 95% CI 0.01–0.12), having electricity at home (aOR 0.38, 95% CI 0.17–0.85) and greater TB knowledge (aOR 0.76, 95% CI 0.59–0.98) remained significant. In conclusion, although nearly all participants reported disclosing their HIV status to someone other than a healthcare provider at ART initiation, nearly a quarter of participants with a primary partner had not disclosed to their partner. Additional efforts to support HIV disclosure (e.g. counseling) may be needed for TB-HIV patients, particularly for women and those unaware of their partners’ status.

Keywords: HIV, tuberculosis, TB-HIV co-infection, disclosure, sexual partnerships

Introduction

Disclosure of HIV diagnosis is associated with improved antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence, better health outcomes, and reduced risk of transmission (Chandra, Deepthivarma, Jairam, & Thomas, 2003; Ostermann et al., 2015; Patel et al., 2012; Ramadhani et al., 2007; Stirratt et al., 2006; Tam, Amzel, & Phelps, 2015; Wong et al., 2009). However, some individuals experience negative outcomes following disclosure, including stigma, discrimination, and rejection or violence (Greeff et al., 2008; Maman, van Rooyen, & Groves, 2014; Nachega et al., 2012).

Co-infection with tuberculosis (TB) further complicates the disclosure process due to stigma surrounding both diseases (Daftary, 2012; Daftary & Padayatchi, 2012; Daftary, Padayatchi, & Padilla, 2007; Gebrekristos, Lurie, Mthethwa, & Karim, 2009; Gebremariam, Bjune, & Frich, 2010). TB-HIV patients who have not disclosed their HIV status face barriers in accessing optimal care for both HIV and TB (Chileshe & Bond, 2010; Daftary & Padayatchi, 2013; Gebremariam et al., 2010). However, HIV disclosure among TB-HIV patients has been understudied, and despite a World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation that HIV testing be offered to partners of TB-HIV patients (World Health Organization [WHO], 2012a, 2012b), disclosure within sexual partnerships has not been widely explored. Understanding correlates of disclosure will aid in identifying individuals who may benefit from additional disclosure counseling, resulting in improved outcomes for patients and their partners.

Utilizing data from TB-HIV patients initiating ART in Lesotho, which bears one of the highest burdens of both TB and HIV in the world (Lesotho Ministry of Health and Social Welfare and ICF Macro, 2015; WHO, 2015), we assessed patterns of disclosure of HIV status, and explored factors associated with non-disclosure to: anyone other than a healthcare provider; and primary sexual partners.

Methods

The START Study was a mixed-methods cluster-randomized implementation science trial in Lesotho; study methodology has been previously described (Howard et al., 2016). This analysis includes 191 and 180 participants from the combination intervention package (CIP) and standard of care (SOC) arms, respectively, who were enrolled in a measurement cohort and completed a baseline interviewer-administered questionnaire (Howard et al., 2016). Inclusion criteria included: ART initiation ≤8 weeks after TB treatment initiation; age 18+; English- or Sesotho-speaking; and capable of providing written informed consent. Multi-drug resistant TB cases were excluded.

The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Columbia University Medical Center and Lesotho’s National Health Institutional Review Board and Ethics Research Committee, and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01872390). All participants provided written informed consent.

The primary outcomes of this analysis were: self-reported disclosure of HIV status to someone other than a healthcare provider; and disclosure to primary sexual partners. Participants who reported disclosure were asked whether they had disclosed to specific individuals, including a spouse/primary partner, parent, sibling, child, other relative, and friend.

Correlates of interest included sociodemographics, and regionally validated measures of hazardous or harmful alcohol use (AUDIT, Cronbach’s alpha 0.86) (Chishinga et al., 2011; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993) and depressive symptoms (PHQ-9, Cronbach’s alpha 0.70) (Bhana, Rathod, Selohilwe, Kathree, & Petersen, 2015; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001; Monahan et al., 2009). We also measured support network size, understanding of written health information, and socially desirable response tendency (Reynolds, 1982) (Cronbach’s alpha 0.80). Study arm was investigated, as CIP participants may have had some exposure to the intervention, including 32 participants who enrolled after a disclosure flipchart was introduced in response to a need identified by healthcare providers.

We developed TB- and HIV-related knowledge items (7 true/false questions per disease) to assess broad understanding of transmission, symptoms, and treatment; knowledge scores were included as the total number of items answered correctly. Intent to disclose TB and a perceived TB stigma scale (14 4-point Likert items, Cronbach’s alpha 0.90) were included. Participants were asked if they knew of household members who were HIV-positive. Clinical variables included time since HIV diagnosis and CD4 count at ART initiation.

All analyses were conducted using SAS® 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Patterns of disclosure were described as proportions disclosing to specific groups. Unadjusted and adjusted associations with non-disclosure were assessed using generalized linear mixed models with a binary outcome (disclosed/not disclosed), with a random intercept for study site due to the cluster-randomized study design. Multivariable models included all correlates significant at p<0.1 in the unadjusted analyses.

Results

Among 371 participants, 56% were men; median age was 35 years (interquartile range [IQR] 30–44) and 54% were married or cohabitating. The median time since HIV diagnosis was 33 days, and among 212 participants with data, the median CD4 count at ART initiation was 151 cells/µL (IQR 59–307).

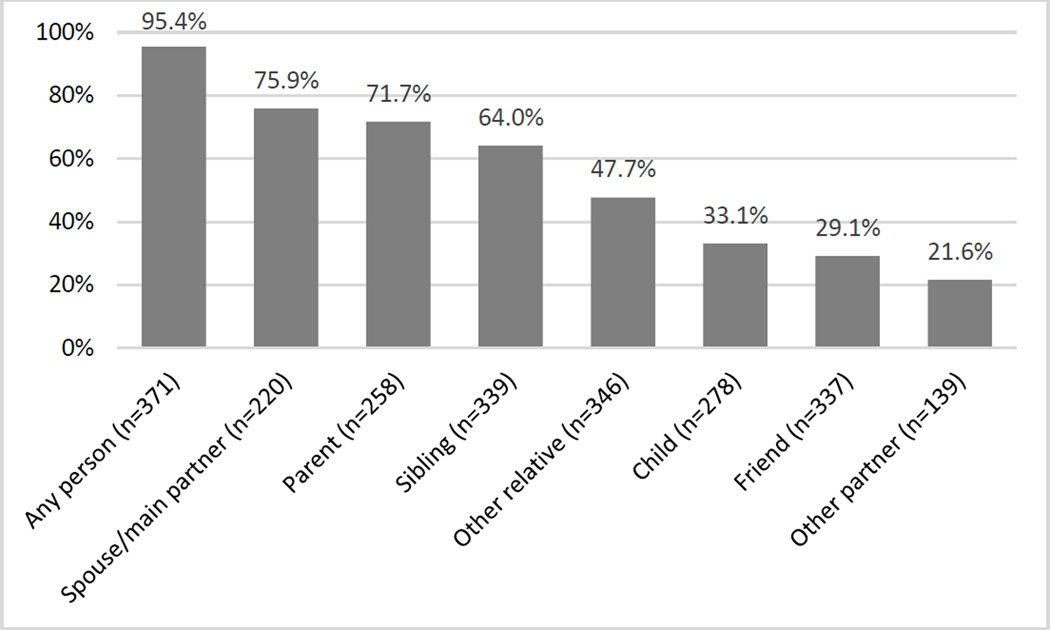

Nearly all participants (n=354, 95%) reported disclosing their HIV status to at least one person other than a healthcare provider. (Figure 1) Among those who had disclosed, the median number of people to whom participants had disclosed was 4 (IQR 2–5). Participants had most commonly disclosed to a spouse/primary partner (76%) or parent (72%).

Figure 1. Patterns of disclosure of HIV-positive status among START measurement cohort participants (N=371).

Proportion disclosed among participants with complete data and relevant disclosure recipient.

In unadjusted analyses, greater TB knowledge (OR 0.67 per item, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.51–0.87), planning to disclose TB status (OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.05–0.64), age (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.00–1.09), greater perceived TB stigma (OR 1.08, 95% CI 1.00–1.18) , and CIP (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.12–1.19) were all associated with non-disclosure to someone other than a healthcare provider at p<0.1; the adjusted point estimates (among N=332 with complete data) were similar to the unadjusted. (Table 1) In adjusted analyses, those with greater knowledge about TB (aOR 0.59 per item, 95% CI 0.39–0.90), and those in CIP (aOR 0.20, 95% CI 0.05–0.79) were less likely to report non-disclosure of HIV status. Planning to disclose TB status (aOR 0.24, 95% CI 0.24–1.02) was marginally associated with lower odds of reporting non-disclosure, while greater perceived TB stigma was marginally associated with greater odds of non-disclosure (OR 1.09 per point, 95% CI 1.00–1.19).

Table 1.

Correlates of non-disclosure of HIV-positive status to at least one person other than healthcare providers among START measurement cohort participants1

| HIV status disclosed (N=354, 95.4%) |

HIV status not disclosed (N=17, 4.6%) |

Crude OR for non-disclosure (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR for non-disclosure (95% CI)4 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | ||||

| Age, median (IQR)2 | 35 (30–43) | 42 (32–49) | 1.04 (1.00–1.09) | 1.03 (0.98–1.08) |

| Female, n (%)3 | 154 (96.3%) | 6 (3.7%) | 0.70 (0.25–1.95) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||

| Married/living together | 193 (95.5%) | 9 (4.5%) | 0.90 (0.34–2.41) | |

| Not married/living together | 94 (95.9%) | 4 (4.1%) | REF | |

| Head of household (sole/shared), n (%) | 158 (94.0%) | 10 (6.0%) | 2.09 (0.74–5.92) | |

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| None | 27 (93.1%) | 2 (6.9%) | REF | |

| Primary | 214 (93.9%) | 14 (6.1%) | 0.91 (0.19–4.24) | |

| Secondary or higher | 113 (99.1%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0.13 (0.01–1.46) | |

| Home amenities, n (%) | ||||

| Improved drinking water3 | 298 (94.9%) | 16 (5.1%) | 2.98 (0.38–23.26) | |

| Any electricity3 | 172 (96.6%) | 6 (3.4%) | 0.61 (0.22–1.69) | |

| Psychosocial variables | ||||

| Depressive symptoms, n (%) | ||||

| None | 100 (95.2%) | 5 (4.8%) | REF | |

| Mild | 143 (99.3%) | 1 (0.7%) | 0.14 (0.02–1.22) | |

| Moderate to severe | 99 (93.4%) | 7 (6.6%) | 1.31 (0.39–4.35) | |

| Hazardous or harmful alcohol use, n (%)3 | 86 (95.6%) | 4 (4.4%) | 1.18 (0.36–3.83) | |

| Size of support network, median (IQR)2 | 4 (3–9) | 2 (2–6) | 0.92 (0.81–1.06) | |

| Little trouble understanding written medical information, n (%)3 | 255 (96.6%) | 9 (3.4%) | 0.54 (0.18–1.60) | |

| Social desirability score, median (IQR)2 | 38 (35–44) | 44.5 (34–46) | 1.05 (0.96–1.15) | |

| TB- and HIV-related variables | ||||

| Time since HIV diagnosis, median days(IQR)2 | 30 (19–83) | 39.5 (29–94) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | |

| CD4 count/μL at ART initiation, median (IQR)2 | 155 (62–312) | 115 (37–135) | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | |

| Other person in home with HIV, n (%)3 | 124 (96.9%) | 4 (3.1%) | 0.64 (0.20–2.07) | |

| HIV knowledge, median (IQR)2 | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) | 0.95 (0.67–1.36) | |

| TB knowledge, median (IQR)2 | 6 (5–6) | 5 (4–6) | 0.67 (0.51–0.87) | 0.59 (0.39–0.90) |

| Plan to disclose TB status, n (%)3 | 327 (96.7%) | 11 (3.3%) | 0.18 (0.05–0.64) | 0.24 (0.06–1.02) |

| Perceived TB stigma score, median (IQR)2 | 41 (38–44) | 45 (39–50) | 1.08 (1.00–1.18) | 1.09 (1.00–1.19) |

| CIP study arm, n (%)3 | 186 (97.4%) | 5 (2.6%) | 0.38 (0.12–1.19) | 0.20 (0.05–0.79) |

Column numbers may not sum to totals due to missing data. Row percentages are provided among non-missing data (n missing: age, 1; head of household 6; depression category, 16; alcohol use, 7; support network size, 8; social desirability, 19; health literacy, 8; time since HIV diagnosis, 23; CD4 cell count, 159; other HIV in home, 19; plan to disclose TB, 11; TB stigma, 38).

Continuous variable; reference for odds ratio is a one-unit decrease.

Binary variable; reference group for odds ratio is the complementary value (i.e. male, not head of household, no improved drinking water, no electricity, no hazardous/harmful use, substantial trouble understanding written medical information, no one else in home is HIV+, does not plan to disclose TB status, SOC arm).

Among participants with complete covariate data (n=332).

Of 230 participants with a spouse/primary partner, 220 (96%) provided information about primary partner disclosure. Of these, 167 (76%) had disclosed their HIV status. (Table 2) In unadjusted models, being female (OR 2.28, 95% CI 1.21–4.31), married status (OR 0.03, 95% CI 0.01–0.10), electricity in the home (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.25–0.89), not knowing the primary partner’s HIV status (OR 7.75, 95% CI 1.80–33.33) and greater TB knowledge (OR 0.73 per item, 95% CI 0.59–0.90) were all associated with non-disclosure at p<0.1. In adjusted models, point estimates had similar interpretation; those who knew their partner was HIV-negative or did not know their partner’s status had much higher odds of non-disclosure than those who knew their partner was HIV-positive (aOR 4.20 95% CI 0.93–18.91), although this association was no longer significant. Participants who were married or living with their partner were less likely (aOR 0.03, 95% CI 0.01–0.12) to report non-disclosure than those who were not married or cohabitating. Those with electricity were also less likely to report non-disclosure (aOR 0.38, 95% CI 0.17–0.85), and for each additional correct TB knowledge item, participants were less likely to report non-disclosure (aOR 0.76 per item, 95% CI 0.59–0.98). Although marginally significant, women still had over twice the odds of non-disclosure compared to men (aOR 2.11, 95% CI 0.97–4.57).

Table 2.

Correlates of non-disclosure of HIV-positive status to the primary partner among START measurement cohort participants with spouse or other primary partner1

| HIV status disclosed (N=167, 75.9%) |

HIV status not disclosed (N=53, 24.1%) |

Crude OR for non-disclosure (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR for non-disclosure (95% CI)4 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | ||||

| Age, median (IQR)2 | 36.5 (31–44) | 38 (31–47) | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | |

| Female, n (%)3 | 54 (66.7%) | 27 (33.3%) | 2.28 (1.21–4.31) | 2.11 (0.97–4.57) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||

| Married/living together | 164 (83.7%) | 32 (16.3%) | 0.03 (0.01–0.10) | 0.03 (0.01–0.12) |

| Not married/living together | 3 (12.5%) | 21 (87.5%) | REF | REF |

| Head of household (sole/shared), n (%)3 | 92 (78.0%) | 26 (22.0%) | 0.97 (0.41–1.43) | |

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| None | 17 (77.3%) | 5 (22.7%) | REF | |

| Primary | 100 (73.0%) | 37 (27.0%) | 1.22 (0.42–3.55) | |

| Secondary or higher | 50 (82.0%) | 11 (18.0%) | 0.72 (0.22–2.41) | |

| Home amenities, n (%) | ||||

| Improved drinking water3 | 139 (74.7%) | 47 (25.3%) | 1.63 (0.63–4.20) | |

| Any electricity3 | 91 (82.7%) | 19 (17.3%) | 0.47 (0.25–0.89) | 0.38 (0.17–0.85) |

| Psychosocial variables | ||||

| Depressive symptoms, n (%) | ||||

| None | 49 (77.8%) | 14 (22.2%) | REF | |

| Mild | 63 (76.8%) | 19 (23.2%) | 1.05 (0.48–2.30) | |

| Moderate to severe | 50 (75.8%) | 16 (24.2%) | 1.11 (0.49–2.51) | |

| Hazardous or harmful alcohol use, n (%)3 | 39 (75.0%) | 13 (25.0%) | 1.17 (0.56–2.42) | |

| Size of support network, median (IQR)2 | 4 (3–8) | 4 (4–8) | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | |

| Little trouble understanding written medical information, n (%)3 | 117 (74.5%) | 40 (25.5%) | 1.79 (0.80–3.97) | |

| Social desirability score, median (IQR)2 | 37 (35–44) | 40 (35–46) | 1.02 (0.97–1.08) | |

| TB- and HIV-related variables | ||||

| Time since HIV diagnosis, median days (IQR)2 | 33 (20–158) | 38 (21–500) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | |

| CD4 cell count/μL at ART initiation, median (IQR)2 | 167 (70–280) | 105 (52–341) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | |

| Does not know if partner has HIV, n (%)3 | 128 (71.5%) | 51 (28.5%) | 7.75 (1.80–33.33) | 4.20 (0.93–18.91) |

| HIV knowledge, median (IQR)2 | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) | 1.12 (0.88–1.43) | |

| TB knowledge, median (IQR)2 | 6 (5–6) | 5 (4–6) | 0.73 (0.59–0.90) | 0.76 (0.59–0.98) |

| Plan to disclose TB status, n (%)3 | 149 (75.3%) | 49 (24.7%) | 4.27 (0.55–33.33) | |

| Perceived TB stigma score, median (IQR)2 | 41 (38–44) | 41 (39–46) | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) | |

| CIP study arm, n (%)3 | 84 (75.7%) | 27 (24.3%) | 1.03 (0.48–2.24) | |

Column numbers may not sum to totals due to missing data. Row percentages are provided among non–missing data (n missing: age, 1; head of household, 3; depression category, 9; alcohol use, 6; support network size, 7; social desirability, 13; health literacy, 7; time since HIV diagnosis, 17; CD4 count, 91; other HIV in home, 11; plan to disclose TB, 8; TB stigma, 23).

Continuous variable; reference for odds ratio is a one–unit decrease.

Binary variable; reference group for odds ratio is the complementary value (i.e. male, not head of household, no improved drinking water, no electricity, no hazardous/harmful use, substantial trouble understanding written medical information, knows partner is HIV+, does not plan to disclose TB status, SOC arm).

Covariate data were complete for all participants (n=220).

Discussion

Although disclosure has been widely studied in populations of HIV patients, this study represents one of the first investigations of HIV disclosure in TB-HIV patients. Our estimated disclosure prevalence (95%) is consistent with previous work in HIV-positive individuals (Longinetti, Santacatterina, & El-Khatib, 2014; Obermeyer, Baijal, & Pegurri, 2011). The correlates we found support qualitative literature: considerations about TB complicate decisions about HIV disclosure (Daftary, 2012; Daftary & Padayatchi, 2012; Daftary et al., 2007). Additional education and disclosure counseling about TB and HIV may increase disclosure, but community-based work to reduce stigma is needed, as counseling patients is likely insufficient if structural discrimination is widespread.

Nearly a quarter of our participants had not disclosed to their primary partner. This is consistent with previous reports in HIV-positive individuals (Obermeyer et al., 2011; Vu et al., 2012), but is concerning because of missed opportunities to offer HIV testing and referral to either treatment or prevention. Our findings of strong correlates support existing literature regarding common correlates of non-disclosure to partners, including being female, not being in a steady partnership, and not knowing the partner’s status (Abdool Karim et al., 2015; Daftary & Padayatchi, 2012; DiCarlo et al., 2014; Geary et al., 2014; Longinetti et al., 2014; Przybyla et al., 2013; Reda, Biadgilign, Deribe, & Deribew, 2013).

Couples-based testing has been suggested as a means to reduce gendered HIV stigma and improve rates of mutual disclosure (DiCarlo et al., 2014). This approach is recommended by the WHO, but does not commonly occur in TB clinics, where many patients are diagnosed with HIV (WHO, 2012a, 2012b). In cases where the partner is the TB treatment supporter, TB clinic visits may provide an opportunity to engage partners in HIV testing (WHO, 2012a). However, in Lesotho treatment supporters do not typically accompany patients to clinic visits. Our study confirms the continued need for efforts to reach partners of TB-HIV patients.

The study’s limitations include its cross-sectional nature and social desirability bias that may have yielded over-reporting of HIV disclosure. However, socially desirable response tendency was not associated with reporting disclosure. In addition, because participants were enrolled at ART initiation, we likely underestimated the prevalence of non-disclosure among all TB-HIV patients in Lesotho. We did not collect data on reasons for non-disclosure or consequences of disclosure.

Our study’s strengths included detailed information about disclosure, which allowed for robust description of disclosure patterns and assessment of a wide variety of correlates. The study’s design ensured that disclosure counseling was provided by healthcare providers, so estimates of disclosure prevalence were not affected by study-related procedures.

Conclusions

Due to the importance of HIV disclosure for patients’ and partners’ well-being, our results suggest that additional efforts to support disclosure, such as counseling or couple’s testing with mutual disclosure, are needed for TB-HIV patients, particularly for women and those who do not know their partners’ status.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the study participants for partaking in the study. We thank Mashale Shale, Limakatso Lebelo, Moeketsi Ntoane, staff at the study sites, village health workers in the surrounding communities, the Berea District Health Management Team and the Lesotho Ministry of Health for their invaluable assistance in conducting this study. We also thank Susie Hoffman for her feedback on early drafts.

This work was supported by is supported by the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of Award Number USAID-OAA-A-12-00022. EHL and YHM were supported by the National Institute of Allergy & Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers T32AI114398 and 1K01A104351, respectively. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. Government.

References

- Abdool Karim Q, Dellar RC, Bearnot B, Werner L, Frohlich JA, Kharsany AB, Abdool Karim SS. HIV-positive status disclosure in patients in care in rural South Africa: implications for scaling up treatment and prevention interventions. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(2):322–329. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0951-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhana A, Rathod SD, Selohilwe O, Kathree T, Petersen I. The validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire for screening depression in chronic care patients in primary health care in South Africa. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:118. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0503-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra PS, Deepthivarma S, Jairam KR, Thomas T. Relationship of psychological morbidity and quality of life to illness-related disclosure among HIV-infected persons. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54(3):199–203. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00567-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chileshe M, Bond VA. Barriers and outcomes: TB patients co-infected with HIV accessing antiretroviral therapy in rural Zambia. AIDS Care. 2010;(22 Suppl 1):51–59. doi: 10.1080/09540121003617372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chishinga N, Kinyanda E, Weiss HA, Patel V, Ayles H, Seedat S. Validation of brief screening tools for depressive and alcohol use disorders among TB and HIV patients in primary care in Zambia. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daftary A. HIV and tuberculosis: the construction and management of double stigma. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(10):1512–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daftary A, Padayatchi N. Social constraints to TB/HIV healthcare: accounts from coinfected patients in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2012;24(12):1480–1486. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.672719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daftary A, Padayatchi N. Integrating patients' perspectives into integrated tuberculosis-human immunodeficiency virus health care. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(4):546–551. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daftary A, Padayatchi N, Padilla M. HIV testing and disclosure: a qualitative analysis of TB patients in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2007;19(4):572–577. doi: 10.1080/09540120701203931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCarlo AL, Mantell JE, Remien RH, Zerbe A, Morris D, Pitt B, El-Sadr WM. 'Men usually say that HIV testing is for women': gender dynamics and perceptions of HIV testing in Lesotho. Cult Health Sex. 2014;16(8):867–882. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.913812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geary C, Parker W, Rogers S, Haney E, Njihia C, Haile A, Walakira E. Gender differences in HIV disclosure, stigma, and perceptions of health. AIDS Care. 2014;26(11):1419–1425. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.921278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebrekristos HT, Lurie MN, Mthethwa N, Karim QA. Disclosure of HIV status: Experiences of Patients Enrolled in an Integrated TB and HAART Pilot Programme in South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res. 2009;8(1):1–6. doi: 10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.1.1.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebremariam MK, Bjune GA, Frich JC. Barriers and facilitators of adherence to TB treatment in patients on concomitant TB and HIV treatment: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:651. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeff M, Phetlhu R, Makoae LN, Dlamini PS, Holzemer WL, Naidoo JR, Chirwa ML. Disclosure of HIV status: experiences and perceptions of persons living with HIV/AIDS and nurses involved in their care in Africa. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(3):311–324. doi: 10.1177/1049732307311118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard A, Hirsch-Moverman Y, Frederix K, Daftary A, Saito S, Gross T, Maama LB. The START Study to evaluate the effectiveness of a combination intervention package to enhance antiretroviral therapy uptake and retention during TB treatment among TB/HIV patients in Lesotho: rationale and design of a cluster randomized trial. Global Health Action. 2016 doi: 10.3402/gha.v9.31543. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesotho Ministry of Health and Social Welfare and ICF Macro. Lesotho Demographic and Health Survey 2014. 2015 Retrieved from Maseru, Lesotho. [Google Scholar]

- Longinetti E, Santacatterina M, El-Khatib Z. Gender perspective of risk factors associated with disclosure of HIV status, a cross-sectional study in Soweto, South Africa. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, van Rooyen H, Groves AK. HIV status disclosure to families for social support in South Africa (NIMH Project Accept/HPTN 043) AIDS Care. 2014;26(2):226–232. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.819400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan PO, Shacham E, Reece M, Kroenke K, Ong'or WO, Omollo O, Ojwang C. Validity/reliability of PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 depression scales among adults living with HIV/AIDS in western Kenya. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(2):189–197. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0846-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachega JB, Morroni C, Zuniga JM, Sherer R, Beyrer C, Solomon S, Rockstroh J. HIV-related stigma, isolation, discrimination, and serostatus disclosure: a global survey of 2035 HIV-infected adults. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2012;11(3):172–178. doi: 10.1177/1545109712436723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. AUDIT: Excerpted from NIH Publication No. 07-3769. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Audit.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Obermeyer CM, Baijal P, Pegurri E. Facilitating HIV disclosure across diverse settings: a review. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1011–1023. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostermann J, Pence B, Whetten K, Yao J, Itemba D, Maro V, Thielman N. HIV serostatus disclosure in the treatment cascade: evidence from Northern Tanzania. AIDS Care. 2015;(27 Suppl 1):59–64. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1090534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel R, Ratner J, Gore-Felton C, Kadzirange G, Woelk G, Katzenstein D. HIV disclosure patterns, predictors, and psychosocial correlates among HIV positive women in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 2012;24(3):358–368. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.608786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przybyla SM, Golin CE, Widman L, Grodensky CA, Earp JA, Suchindran C. Serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among people living with HIV: examining the roles of partner characteristics and stigma. AIDS Care. 2013;25(5):566–572. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.722601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadhani HO, Thielman NM, Landman KZ, Ndosi EM, Gao F, Kirchherr JL, Crump JA. Predictors of incomplete adherence, virologic failure, and antiviral drug resistance among HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(11):1492–1498. doi: 10.1086/522991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reda AA, Biadgilign S, Deribe K, Deribew A. HIV-positive status disclosure among men and women receiving antiretroviral treatment in eastern Ethiopia. AIDS Care. 2013;25(8):956–960. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.748868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Development of reliable and valid short forms of the marlowe-crowne social desirability scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1982;38(1):119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirratt MJ, Remien RH, Smith A, Copeland OQ, Dolezal C, Krieger D, Team SCS. The role of HIV serostatus disclosure in antiretroviral medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(5):483–493. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam M, Amzel A, Phelps BR. Disclosure of HIV serostatus among pregnant and postpartum women in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. AIDS Care. 2015;27(4):436–450. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.997662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu L, Andrinopoulos K, Mathews C, Chopra M, Kendall C, Eisele TP. Disclosure of HIV status to sex partners among HIV-infected men and women in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(1):132–138. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9873-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong LH, Rooyen HV, Modiba P, Richter L, Gray G, McIntyre JA, Coates T. Test and tell: correlates and consequences of testing and disclosure of HIV status in South Africa (HPTN 043 Project Accept) J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50(2):215–222. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181900172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guidance on couples HIV testing and counselling - including antiretroviral therapy for treatment and prevention in serodiscordant couples. 2012a [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO policy on collaborative TB/HIV activities: Guidelines for national programmes and other stakeholders. 2012b Retrieved from http://www.who.int/tb/publications/2012/tb_hiv_policy_9789241503006/en/ [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Lesotho Tuberculosis Profile. 2015 http://www.who.int/tb/country/data/profiles/en/