Abstract

We have constructed an improved recombination-based in vivo expression technology (RIVET) and used it as a screening method to identify Vibrio cholerae genes that are transcriptionally induced during infection of infant mice. The improvements include the introduction of modified substrate cassettes for resolvase that can be positively and negatively selected for, allowing selection of resolved strains from intestinal homogenates, and three different tnpR alleles that cover a range of translation initiation efficiencies, allowing identification of infection-induced genes that have low-to-moderate basal levels of transcription during growth in vitro. A transcriptional fusion library of 8,734 isolates of a V. cholerae El Tor strain that remain unresolved when the vibrios are grown in vitro was passed through infant mice, and 40 infection-induced genes were identified. Nine of these genes were inactivated by in-frame deletions, and their roles in growth in vitro and fitness during infection were measured by competition assays. Four mutant strains were attenuated >10-fold in vivo compared with the parental strain, demonstrating that infection-induced genes are enriched in genes essential for virulence.

Much remains to be learned about genes that the facultative pathogen Vibrio cholerae induces during infection and how their protein products function during the complex and dynamic process in which this pathogen adapts to the human small intestine. Several new methods have been developed that are helping us to explore this process, including in vivo expression technology (IVET), signature-tagged mutagenesis, microarray technology, differential fluorescence induction, in vivo-induced antigen technology, and real-time reverse transcription-PCR, among others. A specific IVET method, recombination-based IVET (RIVET), has been used previously to identify V. cholerae genes that are induced during infection of infant mice (1, 4). RIVET is very sensitive to low or transient expression of in vivo-induced (ivi) genes during infection and is therefore capable of identifying members of this potentially interesting class of genes. However, this sensitivity is also a double-edged sword, as some ivi genes have low-to-moderate levels of expression in vitro and will therefore be lost during library construction, i.e., there will be premature excision (resolution) of the selectable cassette in such strains. In the present study, we have developed a modified RIVET that can overcome this main disadvantage and used it as a large-scale screening method to identify V. cholerae genes that are transcriptionally induced during infant mouse infection. Briefly, the new system incorporates two different resolvable cassettes that differ in the efficiency of excision, as well as three different alleles of the resolvase-encoding gene tnpR that have different efficiencies of translation initiation. These modifications extend the number of V. cholerae strains that are unresolved in vitro that can be generated in the final library. Additional modifications include the incorporation of positive selection for resolved strains, as well as a preselection step for eliminating strains partially resolved in vitro. These modifications increase the efficiency of the screening method and reduce the frequency of false positives, respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructions and antibiotics used.

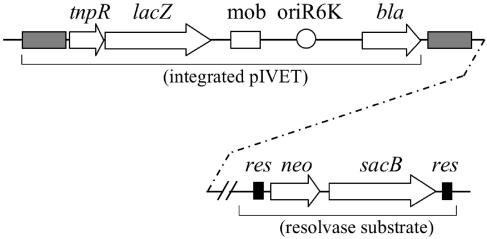

All of the PCR primers used to construct plasmids are listed in Table 1. All of the plasmids and strains used are listed in Table 2. Unless stated otherwise, the antibiotics used in plates were ampicillin (AP) at 100 μg ml−1, rifampin (RIF) at 10 μg ml−1, and kanamycin (KM) at 50 μg ml−1. 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) was used at 40 μg ml−1. New RIVET plasmids lacking extraneous sequences found in the original RIVET plasmid pIVET5 were constructed with genes and other functional sequences present in pIVET5 (2) or pGP704 (16). Briefly, as shown in Fig. 1, each contains an oriR6K origin that needs the host-encoded protein π (pir gene product) for replication, the broad-host-range mobilizable region mobRP4, bla for ampicillin resistance, a promoterless allele of tnpR, and a promoterless allele of the Escherichia coli lacZ gene. A transcriptional terminator and a multiple cloning site (MCS) were placed immediately 3′ of bla. Just downstream of the MCS are the tnpR and lacZ genes, which are transcriptionally coupled. All of these sequences were amplified by PCR from pIVET5 and ligated to make pIVET5n. The PCR primer pairs used to amplify bla, oriR6K, mobRP4, tnpR, and lacZ were BLA-F and BLA-R, ORI-F and ORI-R, MOB-F and MOB-R, TNPR-F and TNPR-R, and LACZ-F and LACZ-R, respectively. All PCRs used Pfu polymerase (Stratagene). pIVET5n was used as the template to construct three derivatives altered in the tnpR ribosome-binding sequence (RBS). Plasmid derivatives pGOA1193, pGOA1194, and pGOA1195 were thus made by PCR with primers TNPR-F4 and TNPR-R4, TNPR-F6 and TNPR-R4, and TNPR-F5 and TNPR-R4, respectively. After amplification, the PCR products were circularized by intramolecular ligation. Each of these primer pairs incorporated stop codons in all three frames between the MCS and tnpR plus one of three different RBSs for tnpR. The RBSs for tnpR(pGOA1193), tnpRmut168(pGOA1194), and tnpRmut135(pGOA1195) are TTTAGGA, TTTAAGA, and TTTGAGA, respectively. The entire DNA sequence of pGOA1193 and the tnpR RBSs of pGOA1194 and pGOA1195 were determined to confirm their correct structure (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide PCR and DNA sequencing primers used in this study

| Primera | 5′-3′ sequence | Use |

|---|---|---|

| VC1500-F0 | AGGGAAATCGACGCTGATTC | SOE PCR |

| VC1500-F1 | CCTATACTGTTTAATGACAC | SOE PCR |

| VC1500-F2 | GCTCCTATTGTAGGTTGTTTGAATGAGTCA | SOE PCR |

| VC1500-R1 | AAACAACCTACAATAGGAGCCGCCATTAAC | SOE PCR |

| VC1500-R2 | CTTTGAGAGAAATGGTCAAG | SOE PCR |

| VC2487-F0 | AACATAGAGTGCATACCTAG | SOE PCR |

| VC2487-F1 | GGAAGGATGTGTGATGAGAG | SOE PCR |

| VC2487-F2 | AAAGCATTTGTGACGTGAATATTAGTGTTC | SOE PCR |

| VC2487-R1 | ATTCACGTCACAAATGCTTTTCTCCATTAC | SOE PCR |

| VC2487-R2 | GCATAAACAACTCATCATTG | SOE PCR |

| VC0488-F0 | AGTATCAGCAACGATTACAG | SOE PCR |

| VC0488-F1 | CCTGTCACGAGTGATTGCTC | SOE PCR |

| VC0488-F2 | GGAAGTTATGTAATGGCAATGCGCTGGATA | SOE PCR |

| VC0488-R1 | ATTGCCATTACATAACTTCCTCATTGTTAT | SOE PCR |

| VC0488-R2 | TAGAAGCGTCTCTTAAACTG | SOE PCR |

| VC0622-F0 | ATCTTACGCGGTAGACTATC | SOE PCR |

| VC0622-F1 | TGGGAAGTCGCTTACTGCTC | SOE PCR |

| VC0622-F2 | ACGTTTTTTGTAAAGCAATCCGCAAGCGAG | SOE PCR |

| VC0622-R1 | GATTGCTTTACAAAAAACGTGAGGAGAATG | SOE PCR |

| VC0622-R2 | ATAATGGCTCTTTGCCTGAG | SOE PCR |

| VC0874-F0 | GTCGTGATGTTGAACTGG | SOE PCR |

| VC0874-F1 | CCATCGAACAAAACCATGACG | SOE PCR |

| VC0874-F2 | TGGTGAATTACATGGGCTATCTCCTCTGG | SOE PCR |

| VC0874-R1 | ATAGCCCATGTAATTCACCACTCATGAGG | SOE PCR |

| VC0874-R2 | CTTTGCGATAACCGTTGATT | SOE PCR |

| VC0130-F0 | GGTGTATGACCAAGCGCATC | SOE PCR |

| VC0130-F1 | GAGCGAGACGCTTGAGCAAG | SOE PCR |

| VC0130-F2 | CTTGCGTTACATAAAGAGCTGATAAGCCAG | SOE PCR |

| VC0130-R1 | TCAGCTCTTTATGTAACGCAAGACGC | SOE PCR |

| VC0130-R2 | CGTTTCAACTCTCGCTGCTC | SOE PCR |

| VC2705-F0 | CTGCGATTAACGACTTGATG | SOE PCR |

| VC2705-F1 | GCTATTAGGCTGCTAACCTAAG | SOE PCR |

| VC2705-F2 | GTATTAACTTACATCGAGATGAAGGAAG | SOE PCR |

| VC2705-R1 | CATCTCGATGTAAGTTAATACTGACTACTCAA | SOE PCR |

| VC2705-R2 | GTGATGCTCCCTGCATTG | SOE PCR |

| VC2646-F0 | GAGATCATGCACGAAGTGCTG | SOE PCR |

| VC2646-F1 | AATTTGTGGTTGCTGCGAAC | SOE PCR |

| VC2646-F2 | ACTCACATTGTAACAAATCGCTAAATGTCA | SOE PCR |

| VC2646-R1 | CGATTTGTTACAATGTGAGTTCAGTTAATTACAC | SOE PCR |

| VC2646-R2 | TTGAGTTCACGATATACCTG | SOE PCR |

| BLA-F | CGCGGAACCCCTATTTGT | pIVETn construction |

| BLA-R | GTCTGACAGTTACCAATG | pIVETn construction |

| ORI-F | CGCTAGTTTGTTTTGACT | pIVETn construction |

| ORI-R | CAGCAGTTCAACCTGTTG | pIVETn construction |

| MOB-F | CAGCCGACCAGGCTTTCC | pIVETn construction |

| MOB-R | CTTTTTGTCCGGTGTTGG | pIVETn construction |

| TNPR-F | CGACCCGGGAGATCTCAATTGTTCGAATTTAGGATACATTTTTAT | pIVETn construction |

| TNPR-R | GCGGTACCTTATGTTAGTTGCTTTCA | pIVETn construction |

| LACZ-F | GCGGTACCACAGGAAACAGCTATGACC | pIVETn construction |

| LACZ-R | TTATTATTTTTGACACCA | pIVETn construction |

| TNPRWTF4 | GAGAATTTAGGATAAATTTTTATGCGACTTTTTGGTTACG | pIVETn construction |

| TNPR135F5 | GAGAATTTGAGATAAATTTTTATGCGACTTTTTGGTTAC | pIVETn construction |

| TNPR168F6 | GAGAATTTAAGATAAATTTTTATGCGACTTTTTGGTTACG | pIVETn construction |

| TNPR-R4 | ACAATTGAGATCTCGAGAAAAAGC | pIVETn construction |

| NEO-F | CGCTCTAGAGGCCTGTGTG | Cassette construction |

| NEO-R | CTGAGATCTAATGCTCTGCCAGTGTTAC | Cassette construction |

| IRGA-F | ATCTTGCATAGGTATTTGACC | PirgA cloning |

| IRGA-R | GCTGGCGCATTTTGAATCA | PirgA cloning |

| SACB1 | GGAAGATCTGATCCTTTTTAACCCATCACATATA | Cassette construction |

| SACB-R1 | CTTCTAGAAAAGGTTAGGAATACGGTTAG | Cassette construction |

| 1RES-F | TCTATTGAATTCCGTCCGAAATATTATAAATTATCGCAC | Cassette construction |

| 1RES-R | TCTAATCTCGAGTGTATCCTAAATCAAATATCGGACAAG | Cassette construction |

| 1RES1-F | TCTAATGAATTCCGTCCGAAATATTACAAATTATCGCAC | Cassette construction |

| 2RES-F | TCTAATCTCGAGTCTAGACGTCCGAAATATTATAAATTATCGCAC | Cassette construction |

| 2RES1-F | TCTAATCTCGAGTCTAGACGTCCGAAATATTACAAATTATCGCAC | Cassette construction |

| 2RES-R | TCTAATGGTACCTGTATCCTAAATCAAATATCGGACAAG | Cassette construction |

| VIVI-F | GACAGCGTGGCACAAAAAAGAGAG | Cassette confirmation |

| VIVI-R | ACCAAAACTCACCCATCCGAGAG | Cassette confirmation |

| T3 | AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGG | Cassette integration |

| T7 | AATACGACTCACTATAGGGC | Cassette integration |

Primers for VCA1008 SOE PCR are described in reference 18.

TABLE 2.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strains or plasmid | Relevant genotype or phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| V. cholerae | ||

| CVD110 | E7946 El Tor Ogawa Δ(cep-ctxB) hlyA::mer::ctxB Hgr | 15 |

| GOA1264 | Spontaneous Rifr form of CVD110 Rifr | This work |

| GOA1245 | GOA1264 res cassette Rifr Kmr Sucs | This work |

| GOA1246 | GOA1264 res1 cassette Rifr Kmr Sucs | This work |

| GOA6W | GOA1264 lacZ::pGP704 Apr LacZ− | Laboratory strain |

| GOA1745 | GOA1245 irgA::pGOA1196 Rifr Kmr Sucs | This work |

| GOA1746 | GOA1245 irgA::pGOA1197 Rifr Kmr Sucs | This work |

| GOA1747 | GOA1246 irgA::pGOA1196 Rifr Kmr Sucs | This work |

| GOA1748 | GOA1246 irgA::pGOA1197 Rifr Kmr Sucs | This work |

| GOA1737 | GOA1264 ΔVC1500 Rifr | This work |

| GOA1738 | GOA1264 ΔVC2487 Rifr | This work |

| GOA1739 | GOA1264 ΔVC0488 Rifr | This work |

| GOA1740 | GOA1264 ΔVC0622 Rifr | This work |

| GOA1741 | GOA1264 ΔVC0874 Rifr | This work |

| GOA1742 | GOA1264 ΔVC0130 Rifr | This work |

| GOA1743 | GOA1264 ΔVC2705 Rifr | This work |

| GOA1744 | GOA1264 ΔVC2646 Rifr | This work |

| E. coli | ||

| SM10λpir | thi recA thr leu tonA lacY supE RP4-2-Tc::Mu λ::pir Kmr | Laboratory strain |

| DH5αλpir | F− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR1 supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1::pir | 10 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRR51 | pBR322::(res-tet-res) | 20a |

| pGP704 | oriR6K mobRP4 Apr | 16 |

| pAC212 | pGP704::neo | Laboratory plasmid |

| pCVD442 | oriR6K mobRP4 sacB Apr Sucs | 5 |

| pSL134 | pPCR-Script::(res1-res1) | Laboratory plasmid |

| pGOA1 | pSL134lacZ::(res1-neo-sacB-res1) | This work |

| pGOA2 | pPCR-Script::(res) | This work |

| pGOA3 | pPCR-Script::(res1) | This work |

| pGOA4 | pPCR-Script::(res-res) | This work |

| pGOA5 | pPCR-Script::(res1-res1) | This work |

| pGOA6 | pGOA4::neo-sacB | This work |

| pGOA7 | pGOA5::neo-sacB | This work |

| pSL111 | pGP704::lacZ | Laboratory plasmid |

| pIVET5 | oriR6K mobRP4 lacZ tnpR Apr | 2 |

| pIVET5n | pIVET5 derivative | This work |

| pRES | pSL111::(res-neo-sacB-res) | This work |

| pRES1 | pSL111::(res1-neo-sacB-res1) | This work |

| pGOA1193 | pIVET5n tnpR | This work |

| pGOA1194 | pIVET5n tnpRmut168 | This work |

| pGOA1195 | pIVET5n tnpRmut135 | This work |

| pGOA1196 | pGOA1193::PirgA | This work |

| pGOA1197 | pGOA1195::PirgA | This work |

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the second-generation RIVET method. A hypothetical integration of pGOA1193 into the genome to generate a merodiploid is shown along with one of the two resolvase substrate cassettes used in this study (the res version is shown). In the example shown, the two regions of the genome are unlinked, which is indicated by the dashed line. Genes are shown by open arrows and are labeled (tnpR, resolvase; lacZ, β-galactosidase; bla, ampicillin resistance; neo, kanamycin resistance; sacB, sucrose sensitivity). The two other plasmids used in this study, pGOA1194 and pGOA1195, are identical to pGOA1193, except for alterations in the tnpR ribosome-binding sequence. The res sequences, which are recognized by resolvase, are shown as filled rectangles. The mobilization (mob) and origin of replication (oriR6K) are shown by the open rectangle and circle, respectively. The genomic fragment that was cloned into the pIVET derivative and allowed homologous recombination into the genome is shown by the gray filled rectangle. Note that in the merodiploid product of this recombination, this fragment is duplicated downstream of the integrated plasmid as shown.

Construction of V. cholerae transcriptional fusion libraries.

The strain used to construct the library, designated GOA1264, was a spontaneously rifampin-resistant (Rifr) strain derived from E7946 El Tor Ogawa derivative CVD110. A resolvable cassette, illustrated in Fig. 1, incorporating the neo and sacB genes flanked by res or res1 sequences was inserted into the lacZ locus of GOA1264 by allelic exchange as described previously (2). To construct the cassette, the neo gene was PCR amplified from plasmid pAC212 with primers NEO-F and NEO-R, and sacB was PCR amplified from pCVD442 with primers SACB1 and SACBR1. The products were ligated into pSL134 to generate pGOA1. The res and res1 sequences were PCR amplified from pRR51 and pSL134 with primers 1RES-F and 1RES-R and primers 1RES1-F and 1RES-R, respectively. The res and res1 products were cloned into pPCR-Script Amp SK(+) (Stratagene) to generate plasmids pGOA2 and pGOA3, respectively. Next, a second set of primers, 2RESF and 2RESR or 2RES1F and 2RESR, was used to PCR amplify a second copy of res or res1. These were inserted immediately next to their counterparts in pGOA2 and pGOA3 to generate plasmids pGOA4 and pGOA5, in which the res and res1 sequences are directly repeated. The sacB-neo genes were subcloned from pGOA1 into XbaI-digested pGOA4 and pGOA5 to generate pGOA6 and pGOA7, respectively. The res and res1 cassettes were PCR amplified from pGOA6 and pGOA7 with primers T3 and T7 and ligated into KpnI-digested pSL111 treated with T4 DNA polymerase. The final plasmids were designated pRES and pRES1, and their structures were confirmed by DNA sequencing (data not shown). pRES and pRES1 were mobilized into strain GOA1264 by conjugation, and allelic exchange was used to place each cassette into the lacZ locus as previously described (2). The res and res1 cassette-containing strains were designated GOA1245 and GOA1246, respectively. The correct placement of the resolvable cassettes was confirmed by PCR with primers VIVIF and VIVIR, which flank the lacZ gene.

Libraries of V. cholerae genomic fragment fusions to tnpR were made in E. coli SM10λpir. The genome of GOA1264 was partially digested with either restriction enzyme Sau3AI or Tsp509I, and then the fragments between 1.5 and 3 kb were purified from agarose gels. pGOA1193, pGOA1194, and pGOA1195 were digested with BglII or MfeI, which yield compatible cohesive ends with Sau3AI and Tsp509I, respectively. The digested plasmids were dephosphorylated with calf intestinal phosphatase (New England Biolabs) and purified from agarose gels. The genomic fragments were ligated into the BglII and MfeI sites upstream of the promoterless resolvase allele in each of the digested plasmids. Thus, a total of six separate ligations were done. Each ligated DNA was electroporated into E. coli DH5αλpir, the transformed cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, and then each was plated for selection of transformants on LB agar supplemented with AP at 50 μg ml−1. Approximately 15,000 transformants were pooled from each of the six ligation combinations. Plasmid DNA was purified en masse from each of the six pools and electrophoresed on agarose gels. Recombinant plasmids 8.5 to 10 kb in size were purified from the gels, electroporated into E. coli SM10λpir, and after 1 h of growth at 37°C in LB broth, cells were plated for selection of Apr transformants on LB agar supplemented with AP at 50 μg ml−1. Approximately 20,000 transformants were pooled from each of the six electroporations and stored at −70°C in 10% glycerol.

Construction of irgA-tnpR fusion strains.

To generate V. cholerae strains with transcriptional fusions of irgA to two tnpR alleles, a genomic fragment containing the irgA promoter was PCR amplified with primers IRGA-F and IRGA-R, which contain BglII restriction sites in their 5′ ends. The amplification products were digested with BglII, and then each was ligated separately into the BglII sites in pGOA1193 and pGOA1195 as previously described (12). The resulting plasmids were mobilized into GOA1245 and GOA1246 by conjugation. Insertion-duplication into the irgA locus was confirmed by PCR (data not shown). Resolution of the resulting reporter strains was measured after growth in LB broth containing a range of ferrous iron concentrations as previously described (12).

Preselection of fusion strains that are inactive in vitro.

Each of the six E. coli SM10λpir plasmid libraries was mobilized into GOA1245 and GOA1246 by conjugation at 37°C for 1 h on AAWP02500 filters (Millipore) on the surface of LB agar plates. Thus, a total of 12 matings were done. Unresolved transconjugants were selected on LB agar supplemented with RIF, AP, KM, and X-Gal. Eleven thousand six hundred sixteen colonies were isolated by picking individual light blue ones with sterile toothpicks. The light blue colonies harbor tnpR-lacZ fusions that are inactive or expressed at a low-level (data not shown). The 11,616 colonies were composed roughly equally of strains from each of the 12 matings. Each colony was grown individually in microtiter plate wells in 100 μl of LB broth plus RIF at 10 μg ml−1, AP at 50 μg ml−1, and KM at 25 μg ml−1 at 37°C for 4 to 5 h and then incubated overnight at room temperature.

A second preselection step to specifically eliminate partially resolved strains was done. For this, each of the 11,616 strains in microtiter plate wells was diluted 1:2,000 in 2 ml of LB broth in deep-well microtiter plates. Five microliters from each diluted culture was spotted onto rectangular LB agar plates plus RIF and also onto LB agar lacking NaCl plus RIF and 10% sucrose. The plates were incubated for 16 h at 30°C, and then the approximate percent resolution of each strain was determined by dividing the number of colonies on the RIF-sucrose plate by the number of colonies on the RIF plate. All strains determined to have resolved to approximately 1% or less were pooled from the microtiter plates, and aliquots were frozen at −70°C in 20% glycerol. The final transcriptional fusion library consisted of 8,734 strains of V. cholerae, each harboring a fusion that was inactive or active at a low level when cells were grown in vitro in LB broth.

Screening for V. cholerae ivi genes.

An aliquot of the library was thawed and grown for approximately 10 generations at 37°C in LB broth plus RIF at 10 μg ml−1, AP at 50 μg ml−1, and KM at 25 μg ml−1 to late exponential phase. The cells were then diluted 1:10 in LB broth and used to intragastrically inoculate 5-day-old CD-1 mice with 50 μl (approximately 5 × 106 CFU) as previously described (2). After 24 h, the mice were euthanized, their small intestines were removed and homogenized in 2 ml of LB broth plus 20% glycerol, and serial dilutions were plated on LB agar minus NaCl plus 10% sucrose and RIF. The plates were incubated for 16 h at 30°C. Individual colonies were picked and grown in LB broth plus RIF at 10 μg ml−1 and AP at 50 μg ml−1. The integrated plasmids were recovered from these strains as previously described (2). Approximately 200 bases of V. cholerae DNA flanking the 5′ end of tnpR was sequenced from each recovered plasmid by arbitrary primed PCR and DNA sequencing as previously described (14). The flanking sequences were compared to the V. cholerae N16916 genome database with blastN (http://tigrblast.tigr.org/cmr-BLAST/index.cgi?database=GVC.seq). The sequence information obtained also revealed which tnpR allele was present in the fusion.

Fusion strain reconstructions and quantification of resolution.

The recovered plasmids of interest were concentrated by ethanol precipitation and resuspension in 10 μl of deionized water. Each plasmid was electroporated into E. coli DH5αλpir and then selected on LB agar plus AP at 50 μg ml−1 and X-Gal. For each plasmid, one blue colony was selected and inoculated into LB broth plus AP at 50 μg ml−1. Note that the basal level of plasmid lacZ expression is high in this E. coli host and the rarely observed white and light blue colonies were found to harbor spontaneous deletions of large portions of the plasmid including part or all of lacZ (data not shown). Plasmid DNA was prepared from each E. coli DH5αλpir transformant strain and electroporated into E. coli SM10αλpir with selection for Apr transformants. Approximately 50 to 200 transformant colonies were pooled from each electroporation and mated with either GOA1245 or GOA1246, followed by selection for unresolved transconjugants as described above. The extent of resolution of each strain after growth in LB broth and after infection of infant mice was measured as previously described (2), except that the percent resolution for each strain was calculated by dividing the titer on LB agar minus NaCl plus RIF and 10% sucrose by the titer on LB agar plus RIF.

Construction of deletion mutation strains.

In-frame deletions of the entire coding sequence of selected V. cholerae ivi genes were constructed in pCVD442 by splicing by overlap extension (SOE) PCR (21) with the oligonucleotide primer pairs in Table 1. Each recombinant pCVD442 plasmid was electroporated into E. coli SM10λpir and transferred to V. cholerae strain GOA1264 by conjugation. Allelic exchange was done as previously described (5), and the chromosomal deletion mutations were confirmed by PCR with primers F0 and R2 (Table 1), followed by DNA sequencing (data not shown).

Competition assays.

Each of the ivi gene deletion strains of V. cholerae (naturally LacZ+) was tested for virulence by competition assays against isogenic LacZ− wild-type strain GOA6W. The GOA6W strain contains a pGP704 insertion in the lacZ locus. Each deletion strain and GOA6W were grown to mid-exponential phase in LB broth plus RIF at 10 μg ml−1 and mixed 1:1. Approximately 105 CFU were inoculated intragastrically into 8 to 10 infant mice as previously described (2). In vitro competition assays were done in parallel by using each of the prepared inocula to inoculate 2 ml of LB broth with 104 CFU; after which the cultures were grown for 16 h at 37°C with aeration, representing approximately 18 generations. The ratio of the test strain to the wild-type strain in each inoculum, as well as in the resulting bacterial populations recovered from the in vitro and in vivo competition assays after 16 and 24 h, respectively, was determined by plating serial dilutions of the outputs on LB agar plus RIF at 10 μg ml−1 and X-Gal at 40 μg ml−1. The in vivo and in vitro competitive indices were calculated by dividing the in vivo or in vitro output ratios of the test strain to GOA6W by the respective input ratios.

RESULTS

Improvements of RIVET.

The original version of RIVET, which was applied to the discovery of V. cholerae ivi genes, used transcriptional fusions to a promoterless resolvase gene (tnpR) in order to couple transcriptional induction to excision of a tetracycline resistance cassette flanked by TnpR recognition sequences (res) (2). The excision of the cassette, being irreversible, led to a phenotypic change (tetracycline sensitivity) that could subsequently be screened for by replica plating.

The RIVET screening method used in the present study incorporates three modifications with respect to the original RIVET method. First, the gene cassette that is the target for TnpR has two reporter genes, neo and sacB, instead of a gene for tetracycline resistance (Fig. 1). The neo gene confers resistance to the antibiotic KM. The sacB gene encodes the levansucrase from Bacillus subtilis. This enzyme produces toxic products in the presence of sucrose and as a result prevents V. cholerae from growing on 10% sucrose plates. Thus, when the sacB-neo genes are excised from the genome by the action of TnpR, the resolved strain becomes sensitive to kanamycin and resistant to sucrose, allowing positive selection. Second, the screening method incorporates three different alleles of the tnpR gene in the pIVET plasmid (Fig. 1) that differ in translation efficiency. Because many ivi genes have low-to-moderate levels of expression in vitro, they require a less active tnpR allele to remain unresolved prior to infection. This modification allows an increase in the number and variety of fusion strains that make up the final library. The third modification was to incorporate a prescreening step to eliminate fusion strains with low levels of resolution in vitro but that were nevertheless still capable of growing on media containing KM. Briefly, the prescreening method involved growing each fusion strain overnight to stationary phase in LB broth in the absence of KM selection and then plating serial dilutions on both LB agar and LB agar supplemented with sucrose. After overnight incubation of the plates, the bacterial titer on sucrose plates was divided by the titer on LB agar in order to calculate the percent resolution that occurred during the growth of each strain in broth. We collected only those fusion strains that resolved to ≤0.1% for inclusion in our library. As will become evident below, these three modifications have greatly improved the efficiency and accuracy of the screening method.

The V. cholerae strain used in our screening method is a derivative of strain CVD110 (E7946 El Tor Ogawa). This toxin-deficient strain has been used before for human vaccine trials and was very efficient at colonizing the human intestine compared with other vaccine strains (15). After genetically modifying this strain (rifampin resistance and res cassette incorporation), we tested if its ability to colonize the infant mouse small intestine was maintained. In single-strain infections, its level of colonization after 24 h (2 × 106 CFU) was equivalent to that of parental strain CVD110 (8 × 105 CFU).

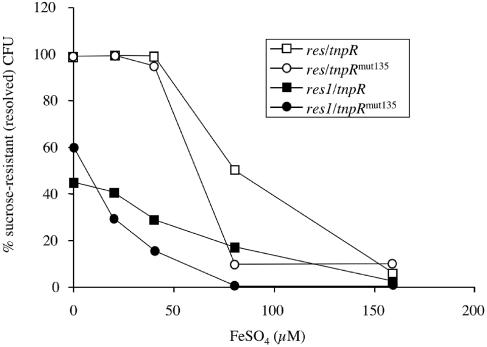

Another preliminary experiment done was to assay the in vitro resolution efficiencies of our final V. cholerae reporter strain constructs with the iron-repressible irgA promoter transcriptionally fused to tnpR in two versions of the RIVET plasmid, pGOA1193 and pGOA1195. The extent of resolution was measured after 8 h of growth in LB broth containing various concentrations of ferrous iron. As the concentration of ferrous iron decreased, level of resolution for each of the strains increased, although with a different dose response for each strain (Fig. 2). Strains GOA1745 and GOA1746, harboring the more sensitive res cassette, resolved more readily than the respective isogenic strains GOA1747 and GOA1748, which contained the res1 mutant cassette. Likewise, strains GOA1745 and GOA1747, harboring the higher translational efficiency tnpR allele, resolved more readily than the respective isogenic strains GOA1746 and GOA1748, which contained the less efficient tnpRmut135 allele. These dose responses are in accordance with the expected levels of resolution previously reported for similar strain constructs (12).

FIG. 2.

Resolution levels versus iron concentration for four V. cholerae reporter strains harboring an iron-repressed fusion to tnpR. Symbols: open squares, GOA1745 (lacZ::res-neo-sacB-res irgA::tnpR); open circles, GOA1746 (lacZ::res-neo-sacB-res irgA::tnpRmut135); solid squares, GOA1747 (lacZ::res1-neo-sacB-res1 irgA::tnpR); solid circles, GOA1748 (lacZ::res1-neo-sacB-res1 irgA::tnpRmut135).

Screening for V. cholerae ivi genes.

The final V. cholerae tnpR fusion strain library contained 8,734 strains each having no or only a very low level of resolution after growth in LB broth. To assess the randomness of the library, we recovered the integrated plasmids from 200 randomly selected strains and sequenced the fusion joints as described in Materials and Methods. Sequences flanking the 5′ end of tnpR were compared to the V. cholerae genome (7) with the blastN algorithm. The results indicated that 95% of the V. cholerae fusion strains are unique.

We inoculated the library intragastrically into 120 infant mice and, after infection for 24 h, plated serial dilutions of small intestinal homogenates on sucrose plates. We isolated a total of 384 sucrose-resistant (resolved) strains on sucrose plates. We attempted to recover the integrated plasmid from each strain and sequence the fusion junctions as described in Materials and Methods. Briefly, the nonreplicating plasmid is able to excise from the chromosome at a low frequency. As a result, the plasmid can be captured by plasmid DNA purification and electroporation into an E. coli strain that supports plasmid replication. Such captured plasmids retain the original V. cholerae genomic DNA insert fused to tnpR. We failed to recover the plasmid or obtain the DNA sequence of the fusion junction for 43 of these, whereas the remainder comprised 122 unique junctions. Ninety-four of the 122 unique gene fusions were plus strand fusions (the tnpR gene was in the same transcriptional orientation as the gene into which it was integrated). We reconstructed 47 of the plus strand fusions into the unresolved GOA1245 and GOA1246 strain backgrounds (res and res1 cassettes, respectively). Each reconstructed strain was tested for resolution in vitro (growth in LB broth) and in vivo (infant mouse infection). Forty (85%) of the 47 reconstructed fusion strains resolved to a greater extent during infection than during growth in vitro and thus contained bona fide ivi genes (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

V. cholerae gene products identified by RIVET as being transcriptionally induced during infection of the infant mouse small intestine compared to during growth in LB broth

| Gene producta: | Cassetteb | Allelec | % of CFU resolved

|

Ratiof | No. of miceg | P valueh | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitrod | In vivoe | ||||||

| VCA1008 | res | tnpRmut135 | <0.1 | 77 | 770 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VC2487 | res1 | tnpRmut168 | <0.1 | 72 | 720 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VC2641 | res1 | tnpRmut135 | <0.1 | 70 | 700 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VC0488 | res | tnpRmut168 | <0.1 | 22 | 221 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VC0063 | res1 | tnpRmut135 | 0.1 | 22 | 220 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VCA1057 | res | tnpRmut135 | 0.3 | 35 | 117 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VCA0773 | res1 | tnpRmut168 | 1 | 100 | 100 | 7 | <0.05 |

| VC0622 | res1 | tnpRmut168 | 0.1 | 10 | 100 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VC1111 | res | tnpRmut135 | <1 | 87 | 87 | 6 | <0.05 |

| VC0207 | res | tnpRmut168 | <0.1 | 8 | 80 | 8 | 0.2 |

| VC0721 | res1 | tnpRmut135 | <0.1 | 4 | 40 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VC1658 | res | tnpRmut168 | 3 | 88 | 30 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VC2373 | res1 | tnpRmut168 | 0.1 | 3 | 30 | 4 | 0.1 |

| VC0201 | res1 | tnpRmut135 | 0.6 | 17 | 28 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VCA0529 | res | tnpR | 0.2 | 2 | 20 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VC0874 | res1 | tnpR | <1 | 19 | 19 | 5 | <0.05 |

| VC1173 | res | tnpRmut168 | 1 | 16 | 16 | 4 | 0.2 |

| VC0202 | res1 | tnpR | 7 | 94 | 13 | 3 | <0.05 |

| VC0203 | res1 | tnpRmut168 | 2 | 25 | 13 | 7 | <0.05 |

| VC1137 | res | tnpRmut135 | <1 | 12 | 12 | 8 | <0.05 |

| VC1535 | res | tnpR | 8 | 93 | 12 | 19 | <0.05 |

| VC1275 | res | tnpR | 8 | 85 | 11 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VC0130 | res1 | tnpRmut168 | 0.2 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 0.1 |

| VC1338 | res1 | tnpR | 3 | 30 | 10 | 4 | 0.05 |

| VC2621 | res | tnpRmut168 | 12 | 90 | 7.5 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VCA0632 | res1 | tnpR | 11 | 77 | 7 | 3 | <0.05 |

| VC2419 | res | tnpRmut135 | 5 | 34 | 6.8 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VC1500 | res | tnpR | 10 | 66 | 6.6 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VCA0752 | res | tnpRmut168 | 4 | 24 | 6 | 7 | <0.05 |

| VCA0687 | res | tnpRmut168 | 0.2 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 0.05 |

| VC2705 | res | tnpR | 3 | 12 | 4 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VC1687 | res | tnpRmut135 | 5 | 18 | 3.6 | 4 | 0.07 |

| VC2742 | res1 | tnpRmut168 | 1.4 | 5 | 3.6 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VCA0016 | res1 | tnpRmut168 | 7 | 24 | 3.4 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VCA0242 | res1 | tnpR | 2.5 | 8.4 | 3.4 | 4 | 0.1 |

| VC2646 | res1 | tnpRmut135 | 8 | 18 | 2.2 | 3 | 0.07 |

| VC2130 | res1 | tnpRmut168 | 35 | 76 | 2.2 | 4 | <0.05 |

| VC1619.1 | res | tnpRmut168 | 13 | 25 | 1.9 | 8 | <0.05 |

| VCA0014 | res | tnpRmut168 | 12 | 18 | 1.5 | 4 | 0.1 |

| VC1034 | res1 | tnpR | 75 | 100 | 1.3 | 4 | <0.05 |

Gene product designation by the Institute for Genomic Research.

res or res1 cassette in GOA1245 or GOA1246 strain background, respectively.

Wild-type, mut168, or mut135 RBS mutant allele of tnpR gene fused to V. cholerae gene.

Percent resolved CFU determined after 11 generations in LB broth.

Percent resolved CFU determined after 24 h of infection in the infant mouse small intestine.

The ivi genes were ranked by their ratio of percent resolution in vivo/in vitro.

Number of mice used per experiment to determine percent resolution in vivo.

Calculated by Student's two-tailed t test between the percent resolution values obtained in vivo and in vitro.

V. cholerae ivi gene functions.

Since we only reconstructed a subset of the original 122 unique gene fusions recovered from mice, the composition of the final confirmed set of ivi genes in terms of gene categories was altered by our subjective selection. For example, one-third of the unique plus strand fusions were in the conserved/hypothetical category but only 10% of our confirmed genes were in this category. In addition, since we decided to study only plus strand fusions, we have undermined the potential role of putative regulatory RNAs in virulence (see Discussion). This notwithstanding, many (15%) of the confirmed ivi genes were previously identified by screening for ivi genes (2; A. Camilli, D. Merrell, and M. Angelichio, unpublished data) or for essential virulence genes (3, 14).

Among the confirmed ivi genes identified are three genes related to chemotaxis: VCA0773 (methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein), VC1535 (methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein), and VC2130 (fliI; flagellum-specific ATP synthase). A large number of metabolic genes, 13, were identified: VC2641 (argH; argininosuccinate lyase), VC1111 (bioA; adenosylmethionine-8-amino-7-oxononanoate aminotransferase), VC1173 (trpG; anthranilate synthase component II), VC1338 (acnA; aconitase hydratase 1), VC1137 (hisA; phosphoribosylformimino-5-aminoimidazole carboxamide ribotide isomerase), VCA1057 (oxidoreductase short-chain dehydrogenase), VC2373 (gltB1; glutamate synthase, large subunit), VCA0016 (glgB; 1,4-α-glucan branching enzyme), VCA0014 (malQ; 4-α-glucanotransferase), VC1034 (udp-1; uridine phosphorylase), VCA0242 (sgbH; putative hexulose-6-phosphate synthase), VC2646 (ppc; phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase), and VC0063 (thiF). Of these genes and pathways, bioB, trpG, and malQ were previously identified as essential virulence genes (3, 14) while argA and VCA0773 were identified as ivi genes (2; Camilli et al., unpublished).

One of the 41 GGDEF domain-containing proteins encoded in the V. cholerae genome, the product of gene VC0130, is induced in mice (Table 3). GGDEF domains are believed to catalyze synthesis of cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP). Recently, a role in virulence for the V. cholerae VieA protein, which can degrade c-di-GMP, was reported (23, 23a), suggesting that c-di-GMP signaling plays an important regulatory role in virulence.

The second largest class of genes identified as ivi genes are the 12 involved in transport across the envelope: VC1008 (putative outer membrane protein), VC0488 (putative extracellular solute-binding protein), VC1275 (conserved protein similar to proteins from the TRAP transport systems), VC0207 (PTS system, sucrose-specific IIBC component), VC0201-0202-0203 [iron(III) ABC transporter components; ATP-binding protein, periplasmic iron compound-binding protein, and permease protein, respectively], VCA0687 [iron(III) ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein], VC1658 (sdaC2; serine transporter), VC2705 (putative sodium solute symporter), VCA0529 (kup; potassium uptake protein, Kup system), and VC0721 (phosphate ABC transporter, putative periplasmic phosphate-binding protein).

Three of the ivi genes may be involved in sensory systems: VC0622 (putative sensory box sensor histidine kinase/response regulator), VCA0752 (trxC; thioredoxin 2), and VC1500 (PqiA family protein).

One putative RTX toxin was identified, the product of the VC1619.1 gene. This protein could have important roles during infection, like many previously described RTX toxins (6, 11).

Four ivi genes are predicted to be involved in various aspects of nucleic acid metabolism, including VC2419 (xerD; integrase/recombinase protein), VCA0632 (MutT/nudix family protein), VC2621 (extracellular nuclease-related protein), and VC2742 (rbn; RNase BN). The extracellular nuclease gene VC2621 was previously identified as an ivi gene (Camilli et al., unpublished).

Finally, there were a number of hypothetical conserved ivi genes (3), including VC2487 (encoding a product similar to glycosyltransferases), VC0874 (hypothetical), and VC1687 (encoding a product similar to inorganic pyrophosphatase/exopolyphosphatase).

Competition assays of V. cholerae mutant strains in vitro and in infant mice.

Some ivi genes are likely to play important roles during colonization but may be redundant, while others may play essential, nonredundant roles. To determine if some of the identified ivi genes fall into the latter class, we made in-frame deletions of the entire coding sequence of nine ivi genes and tested each strain by competition assay during in vitro growth and infant mouse infection. The VCA1008 deletion strain was tested as part of a separate study of V. cholerae outer membrane porins (18); however, it should be noted that its level of attenuation in vivo was found in that study to be 40-fold but with no detectable growth defect in vitro. In this study, three deletion strains showed attenuation levels of more than 10-fold (Table 4). These are strains with deletions in VC2487, VC0874, and VC2705, which were attenuated 20-, 22-, and 14-fold, respectively, in vivo. Our attempt to make an in-frame deletion of VC1619.1 (encoding a putative RTX toxin) was unsuccessful, and this was not rigorously pursued.

TABLE 4.

Competition assays of V. cholerae ivi null mutant strains during growth in vitro and in the infant mouse small intestine

| Gene product mutated | Function | Competitive indexa

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro | In vivo | ||

| VC1500 | Pqi family | 3.9b | 0.74b |

| VC2487 | Conserved protein | 0.56 | 0.049b |

| VC0488 | Extracellular binding protein | 1.6b | 0.56 |

| VC0622 | Histidine kinase | 2.2b | 0.61b |

| VC0874 | Hypothetical protein | 0.95 | 0.045b |

| VC0130 | GGDEF protein | 1.3 | 0.55 |

| VC2705 | Sodium symporter | 0.57 | 0.07b |

| VC2646 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase | 1.4b | 0.67b |

Competitive indices were calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Each in vitro competition was done with two independent LB broth cultures, and each in vivo competition used between 8 and 10 infant mice.

Significant difference from parent strain (P < 0.05) by Student's two-tailed t test using as the control group competitions between parent strain GOA1264 and GOA6W, a virulent control strain harboring a plasmid insertion in lacZ.

DISCUSSION

The IVET methods are the only established ones for large-scale screening for ivi genes within infected animal tissues. Although transcriptional profiling by DNA microarrays has been used to measure gene expression averages within in vivo populations of V. cholerae, it has thus far required compromising the anatomy of the animal by closing off sections of small intestine with ligatures (ileal-loop model) (24). Of the IVET methods, the RIVET system has unique advantages, primarily its sensitivity to transient and/or low-level gene expression, as well as the absence of selective pressure placed upon bacteria during infection (22). However, the same sensitivity is also a major disadvantage in that many gene fusion strains that have low-to-moderate levels of transcription in vitro cannot be identified because such strains resolve and thus are eliminated during library construction. The screening method that we report here, which uses a combination of three tnpR alleles with different translation initiation efficiencies and two resolvable cassettes with different resolution efficiencies, minimizes this limitation. Our results show that this second-generation RIVET method is able to detect a wider range of ivi genes than the previous version (2).

Other improvements of our screening method include the incorporation of the sacB gene in the resolvable cassette and a preselection step to eliminate partially resolved strains. Livny and Friedman (13) recently reported a variation of RIVET, termed SIVET for “selectable IVET,” in which resolution generates a functional chloramphenicol resistance gene, allowing positive selection of resolved strains. Inclusion of sacB in our resolvable cassette similarly allows positive selection of resolved strains (on agar supplemented with sucrose). The ability to positively select resolved strains and the preselection step have improved the efficiency and accuracy of the screening method. Indeed, the present screening method identified 85% of the putative ivi genes that were reconstructed and tested as bona fide ivi gene fusions whereas only 35% of those obtained by the prior RIVET screening method were ivi genes (2). In comparing our data with previous microarray data obtained from V. cholerae grown in LB broth, we see that the majority (98%) of our ivi genes fall below the 80th percentile of rank order gene expression in LB broth (24). This fact indicates that the preselection step that was added to the RIVET screening procedure was effective at removing fusion strains that are active in vitro.

Many ivi genes identified by this screening method could be important players in the adaptation of V. cholerae to the small intestine. The product of the VC1619.1 gene is similar to RTX toxins, which include cytolytic toxins (hemolysins and leukotoxins), metalloproteases, and lipases. The presence of tandemly repeated nonapeptides (GGXGXDX[L/I/V/W/Y/F]X; 6 to 40 times) is a sine qua non characteristic of this family of toxins. VC1619.1 has seven such repeats at its carboxy-terminal end. In addition, the protein has six cadherin-related domains in its central segment. This protein may contribute to induction of an inflammatory response in the infected host, as has been previously described for another V. cholerae toxin belonging to this family (6). Some of the ivi genes may play roles in adaptation to stressful conditions. VC0622 is homologous to BaeS (bacterial adaptive response), which has been shown to be involved in sensing cell envelope stresses, including spheroplast formation and overexpression of misfolded proteins (19). Also, the putative PqiA-homologous protein VC1500 may sense envelope stresses. This protein is an integral membrane protein and is related to proteins that are induced by the herbicide paraquat, which generates reactive oxygen species (9). Thioredoxin 2, which was also identified by our screening method, is known to play a role in oxidative stress responses in other bacteria (20). Another potentially important gene for host adaptation is the mutT ortholog VCA0632. Interestingly, V. cholerae has 11 paralogs of the MutT/nudix protein family. MutT-related proteins degrade 8-oxoguanosine, one of the most abundant kinds of DNA lesion resulting from oxidative stress (8). It is possible that prevention or correction of oxidative DNA damage is an important adaptive response of V. cholerae during infection (17).

Several of the ivi genes identified by this screening method are likely to be involved in nutrient acquisition. Two ivi genes related to phosphate acquisition (VC0721 and VC1687) were detected. In addition, one more phosphate-related gene was detected in the 94 putative ivi genes initially isolated (VC0723; polyphosphate kinase homolog). Also, two genes involved in glycogen metabolism (VCA0016 and VCA0014) were detected. The induction of these genes during infection suggests that in mice phosphate and energy sources are scarce and perhaps polyphosphates and stored carbohydrates are required for survival in this environment.

Approximately half (19 of 40) of the ivi gene products are predicted to be localized to the surface of V. cholerae. This indicates that genes detected by the RIVET system are enriched for those important for interaction with the surroundings, as would be expected from a theoretical point of view. On the other hand, of the 40 ivi genes identified only 1 may belong to a known class of virulence factors (putative RTX protein). This finding is not new (2) and suggests that the majority of the ivi genes may not belong to the standard virulence gene category.

In comparing the results of our screening method with those of a published microarray screening method (24), it should be noted that there is little overlap in the ivi genes detected. Only 15% of our genes (6 of 40) had levels of induction of >2 in rabbit loop microarrays and, conversely, the microarray study identified approximately 700 genes with levels of induction of >2 (ca. 22% of the total studied). Therefore, microarrays used to detect genes induced in vivo in animal tissues appear to be more sensitive and comprehensive than the RIVET method. One factor to consider in this light is that microarrays measure steady-state mRNA concentration changes rather than transcriptional initiation per se. Thus, if many of the genes that are induced in vivo are mostly regulated by mRNA degradation, the RIVET method may not be very suitable for their detection but microarrays would. On the other hand, microarrays can only be used to study gene expression at the time of sampling, whereas RIVET can detect genes that are turned on transiently at any stage of infection. Although additional microarray experiments can be done to examine expression at other times of infection, some times may not be feasible because not enough bacteria are present for isolation of sufficient amounts of RNA.

Genes VC1111 (bioB), VC1173 (trpG), and VCA0014 (malQ) and their respective metabolic pathways were previously reported to be essential for infectivity by signature-tagged mutagenesis screening methods (4, 14). In this and a related study (18), we found that 7 of the 10 ivi genes tested were important to achieve wild-type levels of intestinal colonization. Three of these mutants were only mildly attenuated, whereas four were attenuated >10-fold. This percentage (40%) is similar to the overall percentage (47%) of ivi genes that are required for virulence in animal models compiled from numerous IVET screening methods done on a number of different pathogens (1). Of the genes identified in this work, the most attenuated was VCA1008 (18). This result is interesting because VCA1008 was also the most highly induced ivi gene identified by our screening method. In a separate study, we have shown that VCA1008 is the only known porin in V. cholerae required for virulence (18). The next most attenuated mutant strain (attenuated 20-fold) carried VC2487, which was also the second most highly induced ivi gene identified. However, after these two, this correlation between the level of transcriptional induction in vivo and importance for virulence no longer held, demonstrating that the tunable RIVET method is robust in finding bona fide virulence genes. A possible explanation for the lack of attenuation of VC0488 and VC0130 and the small attenuation levels of VC1500, VC0622, and VC2646 is redundancy. In the case of VC0130 (GGDEF protein), there are 40 other genes in V. cholerae that contain a GGDEF domain, each predicted to synthesize c-di-GMP. Consequently, a single mutation of only one gene of the entire family may not result in an observable phenotype.

Our results demonstrate that the second-generation RIVET method described herein is able to efficiently and reliably detect V. cholerae ivi genes in the infant-mouse model of cholera. The identification and characterization of such genes may contribute to the development of more efficacious vaccines to protect against cholera.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Center for Vaccine Development in Baltimore for generous help in preparing the gene fusion library.

This work was supported by Pew Latin American Fellowship P0337SC to C.G.O and NIH grants AI45746 and AI55058 to A.C. and AI19716 to J.B.K.

Editor: V. J. DiRita

REFERENCES

- 1.Angelichio, M. J., and A. Camilli. 2002. In vivo expression technology. Infect. Immun. 70:6518-6523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camilli, A., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1995. Use of recombinase gene fusions to identify Vibrio cholerae genes induced during infection. Mol. Microbiol. 18:671-683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiang, S. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1998. Use of signature-tagged transposon mutagenesis to identify Vibrio cholerae genes critical for colonization. Mol. Microbiol. 27:797-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiang, S. L., J. J. Mekalanos, and D. W. Holden. 1999. In vivo genetic analysis of bacterial virulence. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 53:129-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donnenberg, M. S., and J. B. Kaper. 1991. Construction of an eae deletion mutant of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by using a positive-selection suicide vector. Infect. Immun. 59:4310-4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fullner, K. J., J. C. Boucher, M. A. Hanes, G. K. Haines III, B. M. Meehan, C. Walchle, P. J. Sansonetti, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2002. The contribution of accessory toxins of Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor to the proinflammatory response in a murine pulmonary cholera model. J. Exp. Med. 195:1455-1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heidelberg, J. F., J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, L. Umayam, S. R. Gill, K. E. Nelson, T. D. Read, H. Tettelin, D. Richardson, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. Vamathevan, S. Bass, H. Qin, I. Dragoi, P. Sellers, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, R. D. Fleishmann, W. C. Nierman, and O. White. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imlay, J. A., S. M. Chin, and S. Linn. 1988. Toxic DNA damage by hydrogen peroxide through the Fenton reaction in vivo and in vitro. Science 240:640-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koh, Y. S., and J. H. Roe. 1995. Isolation of a novel paraquat-inducible (pqi) gene regulated by the soxRS locus in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:2673-2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolter, R., M. Inuzuka, and D. R. Helinski. 1978. Trans-complementation-dependent replication of a low molecular weight origin fragment from plasmid R6K. Cell 15:1199-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lally, E. T., R. B. Hill, I. R. Kieba, and J. Korostoff. 1999. The interaction between RTX toxins and target cells. Trends Microbiol. 7:356-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee, S. H., D. L. Hava, M. K. Waldor, and A. Camilli. 1999. Regulation and temporal expression patterns of Vibrio cholerae virulence genes during infection. Cell 99:625-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Livny, J., and D. I. Friedman. 2004. Characterizing spontaneous induction of Stx encoding phages using a selectable reporter system. Mol. Microbiol. 51:1691-1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merrell, D. S., D. L. Hava, and A. Camilli. 2002. Identification of novel factors involved in colonization and acid tolerance of Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1471-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michalski, J., J. E. Galen, A. Fasano, and J. B. Kaper. 1993. CVD110, an attenuated Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor live oral vaccine strain. Infect. Immun. 61:4462-4468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller, V. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1988. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol. 170:2575-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Rourke, E. J., C. Chevalier, A. V. Pinto, J. M. Thiberge, L. Ielpi, A. Labigne, and J. P. Radicella. 2003. Pathogen DNA as target for host-generated oxidative stress: role for repair of bacterial DNA damage in Helicobacter pylori colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:2789-2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osorio, C. G., H. Martinez-Wilson, and A. Camilli. 2004. The ompU paralogue vca1008 is required for virulence of Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 186:5167-5171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raffa, R. G., and T. L. Raivio. 2002. A third envelope stress signal transduction pathway in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1599-1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raman, S., T. Song, X. Puyang, S. Bardarov, W. R. Jacobs, Jr., and R. N. Husson. 2001. The alternative sigma factor SigH regulates major components of oxidative and heat stress responses in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 183:6119-6125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20a.Reed, R. R. 1981. Transposon-mediated site-specific recombination: a defined in vitro system. Cell 25:213-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Senanayake, S. D., and D. A. Brian. 1995. Precise large deletions by the PCR-based overlap extension method. Mol. Biotechnol. 4:13-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slauch, J. M., and A. Camilli. 2000. IVET and RIVET: use of gene fusions to identify bacterial virulence factors specifically induced in host tissues. Methods Enzymol. 326:73-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tischler, A. D., and A. Camilli. 2004. Cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 53:857-869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23a.Tischler, A. D., S. H. Lee, and A. Camilli. 2002. The Vibrio cholerae vieSAB locus encodes a pathway contributing to cholera toxin production. J. Bacteriol. 184:4104-4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu, Q., M. Dziejman, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2003. Determination of the transcriptome of Vibrio cholerae during intraintestinal growth and midexponential phase in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:1286-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]