Abstract

The purposes of this exploratory pilot were to describe perceived barriers to participation in cervical cancer prevention research, and identify culturally-appropriate communication strategies to recruit Asian women into cancer prevention research. This thematic analysis of transcripts, from focus groups and in-depth interviews, was conducted in English, Vietnamese, and Mandarin Chinese, at a community clinic in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Thirty participants were either Vietnamese (35%) or Chinese (65%). Mean age was 36.8 (SD 9.9 years). Reasons for non-participation were: lack of time, inconvenience, mistrust of institutions and negative experiences, lack of translated materials, feeling intimidated by English, and the lack of translation of key words or terms. Enhancers of participation were: endorsement by a spouse, monetary compensation, and a personalized approach that offers a benefit for Asian women. To increase participation, first one must remove language barriers and, preferably, use specific dialects. Second, one must specify if benefits are indirectly or directly related to the family or cultural group. Asian research participants in our study consistently expressed that a significant motivator was their desire to be of help, in some way, to a family member or to the Asian community in general.

Keywords: Asian women, Vietnamese, Chinese, Research participant, Recruitment strategies, Women’s health research

Background

Cervical cancer is the second most common malignant disease in women worldwide, and the leading cause of death in women in countries without screening programs [1 3]. Incidence rates vary between different countries. Per 100,000 women there are 20–29.9 cases in Vietnam; 10–19.9 case in Thailand and Laos; and 2–9.9 cases in the United States and China [4]. In the United States (US), disparities exist by race and ethnicity resulting in incidences per 100,000 as follows: Hispanic 14.7, African American 13.0, Asian American 9.3, White 8.6, and American Indian/Alaskan 7.2 [5]. The incidence for Vietnamese American women is particularly striking at 43.0 per 100,000, among the highest worldwide, and even higher than rates documented in Vietnam [6].

An Asian woman’s lifetime risk of cervical cancer in the US is 1 in 138. About 3,670 women died from this disease in 2007 [5]. Nationally, an estimated 11,150 new cases of cervical cancer will be diagnosed each year. This figure does not include the many more women diagnosed with cervical dysplasia (pre-cancer) who will require colposcopy, biopsy, cryosurgery, or other treatment to prevent cancer progression. However, sixty-eight percent of Asian American women reported having the lowest rate of Pap testing (64%) compared to Whites (84%), African Americans (86%) and Latinas age 18 or older (78%) [7]. Failure to receive routine Pap tests can result in missed opportunities to treat cervical dysplasia before it becomes malignant. Women with low rates of Pap testing are the ones who would benefit most from HPV vaccination.

Asian Women Participation in Research

A major concern among researchers is the insufficient data on the health status of Asian women [8] as a result of low participation in clinical trials [9]. Des Jarlais et al. [10] reported that among 13,433 women recruited for a breast cancer prevention study, Asians women had the highest rate of refusal (55.4%) compared to Blacks (40.7%), Latinas (33.4%) and Whites (37.4%). Three reasons are documented for low enrollment rates: (1) the absence of translated study materials in their native language [11] and the associated high costs of translation, which may contribute to systematic exclusion from clinical trials; [12, 13] (2) passive exclusion associated with cultural stereotypes; [14] and (3) lack of confidence in physicians, and the feeling that physicians look down on them [15, 16].

Chinese and Vietnamese people constitute a large proportion of a growing population, both nationally and in the study area (Pennsylvania) [17]. Many of them are low-income immigrants with limited English proficiency [18–21]. Consequently, there is a growing need to expand our understanding of this population. We need to identify the existing barriers to employing effective prevention strategies and identify specific ways to develop culturally appropriate strategies to recruit Asian women as research participants.

Asian American women are disproportionately affected by cervical cancer, and this group has been underrepresented in clinical research [22–24]. A targeted approach is needed to adequately recruit Asian American women into comprehensive studies of the multiple factors that contribute to their risk for cervical cancer. There are some data on Asian-American women and the behavioral factors associated with medical procedures such as Pap testing. We need more information on behavioral issues related to participation in HPV and HPV vaccine uptake trials, treatment protocols, and studies related to cancer risk.

Methods

This descriptive pilot explores perceived barriers and facilitators to participation in prevention research that focuses on cervical cancer. We examine ways to develop effective, culturally-appropriate communication strategies to recruit Chinese- and Vietnamese-American women into cervical cancer prevention studies that include biosampling. The methodology follows the recommendations of Johnstone et al. [25] and Culley et al. [26] to use focus groups to identify barriers and provide a gateway to participation in research. We used thematic content analysis of narrative data to answer the specific research questions: what are the barriers to participation in research among Asian American women at-risk for cervical cancer; and what specific recruitment strategies could enhance study enrollment?

Participants

The study targeted Chinese-American or Vietnamese-American women between the ages of 21 and 65 years. Women were eligible if they spoke English, Mandarin, or Vietnamese. A woman was not eligible if she had a personal history of cervical cancer or hysterectomy (no cervix). Approval for human subject research was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania (UPENN), the Abramson Cancer Center of UPENN, and the Philadelphia Department of Public Health (PDPH). Written consent forms were prepared in English, Chinese and Vietnamese. All were approved by the IRB at UPENN and PDPH.

Recruitment

Women were recruited, during regular clinic hours, in the waiting area of a District Health Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This health clinic offers family planning/prenatal clinic and approximately 40% of patients are Chinese or Vietnamese immigrants. All participants were given monetary compensation ($25) for time and travel and a copy of their signed consent. The recruitment team consisted of four female staff members from the Penn Asian Health Initiatives (PAHI). They were trained in human subject research and in the techniques of conducting focus groups and in-depth interviews. All four individuals were bilingual in English and in either Mandarin or Vietnamese and all had advanced knowledge of Chinese or Vietnamese culture. In particular, the bi-lingual and bi-cultural Principle Investigator and project coordinator provided training to recruitment staff on institutional recruitment protocols and clinical research recruitment policies.

Recruiters approached women who they determined met eligibility criteria. Recruiters initiated the process in English and, depending on the response of the individual, either transitioned to speaking in the same language as the individual or signaled for another recruiter who spoke that language to continue the process in the spoken language. A recruiter presented the study to the individual using a script that was approved by the UPENN/PDPH-IRB. The script explained the study, the required action from the individual to participate, and the risks associated with participation. Individuals were informed of their right not to participate. Those who agreed to participate were presented a language-appropriate consent form for signature and given a copy of that document. Informed consent was confirmed verbally over the course of data collection.

Data Collection

The two most common Asian languages spoken in the US are Chinese and Vietnamese [27]. Among those who speak these, less than half speak English “very well” [28]. Interviews were conducted in the language preferred by the participants’ [29–31].

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. The names and other identifiable information were deleted. Although our goal was to have multiple participants for each focus group, there were several occasions when only one person was able to attend. In such cases, we conducted a one-to-one interview.

Translation Procedures

Translators were Chinese or Vietnamese-speaking individuals with bi-lingual abilities and an in-depth understanding of the respective cultures. The materials subjected to systematic translation were: recruitment and interview guides, audio-taped interviews, and self-report questionnaires. The process for translating written materials included the following steps. First, audio-tapes and written documents (e.g. scripts) were translation from the original language to the targeted language. Second, the translations were reviewed by a committee of experts (including bilingual/bicultural investigators) [32] for accuracy in meaning. Third, these documents were translation back to the original language to confirm the retention of the meaning and the context. [32]A different set of bilingual translators “back-translated” the materials from Chinese or Vietnamese to English. Forth, a second review by experts and lay people was conducted to assess content validity, readability, etc. Finally, all linguistically discordant items were reconciled. The final materials accurately reflected the intent of the wording in the original language [33]. These materials were assessed for readability at the grade level (according to Flesch-Kincaid) of 6.8 [32].

Systematic back-translation is especially important. Back-translation is the evaluation of the proximity of the meaning of content from the source as compared to the translated version. This method is used to identify language conversion errors by translating back from the target language to the source language. Translating written words from one language to another can easily preserve the definitions of the words. However, translation that preserves the conceptual equivalence of whole sentences and paragraphs is more difficult and therefore benefits from back-translation. Capturing cultural context may also require changes to the format of an instrument and the interviewing procedure.

Measures

Data were collected using questionnaires and interviews. The patient-reported items included socio-demographics such as age, ethnicity, country of birth, and language skills/preferences; and selected behaviors such as (a) previous experience with biomedical research, (b) most recent Pap test, and (c) HPV vaccination history. The interview guide queried opinions about participating in biomedical research and bio-sampling.

Analysis

Text data were derived from 234 pages of transcription from 17 focus groups/interviews. Thematic content analysis of narrative data [34] developed themes using theory-driven or prior-research-driven methods and then applied a code to a “critical incident” or example of a conceptual construct, for example, a “barrier to participation” [35, 36]. Coding of narrative data was at two levels [37]. First level (open coding) was line-by-line to search for comments related to experiences as research subjects, and the kinds of studies. The surrounding text was examined for links to specific feelings or judgments about the experiences. The second level of coding grouped the experiences and judgments into categories (themes) that matched the conceptual constructs of: (a) reasons to participate, (b) reasons to refuse participation, (c) enhancers of participation, and (d) approaches to recruitment [33]. We reexamined the surrounding text for links to specific statements that described ways to improve recruitment or enhance research participation among Asian women [38]. The statements were assigned a positive value (facilitating participation) or a negative value (hindering participation). Interviewers’ and translators’ impressions were noted and incorporated into the analyses.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Over a period of 20 weeks, a total of 231 Asian women were approached and invited to participate. Sixty-nine women agreed to participate. Thirty-nine women did not return for the qualitative study. Participation rate was 43% of those who initially expressing interest. Non-participation was mostly due to challenges in the scheduling of their office visits. Of the thirty who completed the study, 35% identified themselves as Vietnamese and 65% as Chinese. Ages ranged from 22 to 58 years with a mean age of 36.8 (SD 9.9 years). Three participants were born in the US. The remainder (N = 27) immigrated to the US at ages ranging from 12 to 52 years (mean age 29.6, SD 11.3 years). For additional characteristics see Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample

| Characteristics (N = 30) | Range, Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 22–59, 36.8 (9.9) |

| Age at immigration (years) | 12–52, 29.7 (11.3) |

| N (%) | |

| Ethnicity | |

| Vietnamese | 9 (35) |

| Chinese | 11 (65) |

| Spoken language | |

| Chinese | 12 (40) |

| English | 9 (30) |

| Vietnamese | 9 (30) |

| Country of birth | |

| USA | 3 (10) |

| Vietnam | 9 (30) |

| China/Taiwan | 8 (27) |

| Other (Mostly Indonesia) | 10 (33) |

| English proficiency | |

| Very well | 5 (17) |

| Well | 10 (33) |

| Not well | 13 (43) |

| Not at all | 2 (7) |

| Preferred native language (non-English) for focus group discussion |

18 (60) |

| Other demographics | |

| Employed for pay, part or full time | 13 (43) |

| Has health insurance | 6 (20) |

| Finished 12 years school | 25 (83) |

| Some schooling in USA | 18 (60) |

| Married, living with partner | 20 (67) |

| Has a daughter | 17 (68) |

| Has health insurance | 6 (20) |

Preventive health behaviors varied across the sample. The majority (63%, N = 19) reported having had a least one pelvic exam, but 38% (N = 11) reported never having a Pap test, while one participant was unsure. Of those reporting having had a Pap test (N = 18), 94% (N = 17) were tested within the last 2 years. Forty percent (N = 12) of the women knew about the HPV Vaccine specifically by name but only one had been vaccinated. This project was the first encounter with research for over 86% of participants (N = 26). Of those who had been research subjects (N = 3), only 1 had provided a bio-sample and this was not blood.

Barriers to Participation in Research

Participants reported several important barriers to participating in research related to women’s health issues and cervical cancer risk in particular. Major barriers to participation were: limited time, mistrust, privacy issues, and inclusion of bio-sampling in the process.

The most frequently reported reason for non-participation in research was “lack of time, inconvenience, and competing interests” (see Table 2). This was a major inhibitor of participation in research even when alternative opportunities were conveniently presented.

Table 2.

Psychosocial barriers to participation

| Cases = number of Individuals who identified the concept | ||

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual category | ||

| Concepts | Cases (%) |

|

| Barrier to participation |

Lack of time, inconvenience | 18(60) |

| Mistrust of Institutions, negative experience |

9(30) | |

| Loss of privacy | 6(20) | |

| Language not English | 5(17) | |

| Specific fears: needles, cancer | 5(17) | |

| Sexuality as topic | 4(13) | |

| Confusing research with medical care | 4(13) | |

| No personal relevance | 3(10) | |

| Shame, stigma | 2(7) | |

| Required to give blood sample | 1(3) | |

| Long term participation | 1(3) | |

| Diff concept of medicine | 1(3) | |

| Medications part of procedure | 1(3) | |

| Biosampling | Need reason why | 7(23) |

| Too precious to give | 4(13) | |

| Associated with sickness | 3(10) | |

| Personally intrusive | 3(10) | |

Sixty percent (N = 18) of the participants reported a concern for their limited time at least twice in their interviews. The second most frequently reported reason for not participating in research was “mistrust of institutions and negative experiences” (30%, N = 9). Such mistrust was acquired vicariously through the experiences of others or through mass media illustrations of research. Recalling the experience of a family member, one woman stated that her relative “…was vaccinated while going to school. She had a serious fever. She’s afraid now.”

The simple act of interacting with strangers was the source of suspicion and mistrust, which is increased when language was a barrier or the bilingual recruiter and participant spoke different dialects. Three barriers to participation that were related to mistrust were “loss of privacy (20%, N = 6) and “traditional beliefs,” (20%, N = 6), and “sexuality as a topic” (13%, N = 4).

Privacy was an issue to all women but older women were reticent to discuss sexuality issues. Older participants tended to be more traditional or “isolationist” and not willing to be in research. Older women in this study did not elaborate on this barrier. However, the recruiters observed that when some older women arrived at the clinic with their spouses, they would look to them to sanction participating, prior to agreeing.

When asked about women’s health research that involved bio-sampling, participants expressed general reticence. Seventeen percent (N = 14) reported one or more specific concerns with bio-sampling. Among these 43% (N = 6) were Vietnamese, 36% (N = 5) were Chinese, and 21% (N = 3) further specified that they were Chinese-Indonesian. Six percent (N = 5) expressed two or more from among the following: “associated with illness,” “need a reason,” “personal intrusion,” “too precious to spare,” and “citing a negative experience of another.” Participants made a distinction between types of samples, such as blood and other tissue. Four participants reported believing that blood, in particular, was “too precious to give” (13%, N = 4). Another knowledgeable participant knew that blood contained her DNA and therefore said she would hesitate to allow blood sampling.

Language Issues

Finally, language was confirmed as a barrier to participation. Language was inextricably linked to all other obstacles to participation in women’s health research (17%, N = 5). Participants named “lack of translated materials,” “feeling intimidated by English,” and the lack of translation of key words or terms. In addition, even if translation was attempted, differences in dialect or pronunciation could dissuade participation.

Enhancers of Participation in Women’s Health Research

Participants were asked to think about reasons why an Asian woman would be willing to enroll in research. Major enhancers to participation were: personal gain, benefit to other Asian women, and endorsement by a spouse.

The most frequently reported reason to enroll in women’s health research was for “personal gain” of medical help, information, and compensation (67%, N = 20). Personal gain was not entirely unexpected. Thirteen percent of participants made comments that suggested confluence of the aims of medical care and the aims of research (see Table 2). A second reason was for the “benefit of others” (40%, N = 12). This reason was often mentioned along with “personal benefit.” Of those who wished to benefit others, 60% specifically referred to Asian Americans. An altruistic rationale for participating was evident for both Chinese and Vietnamese participants. Participants reported that the likelihood of participating in research was increased if it was endorsed by a spouse (27%, N = 8), if compensation was offered (20%, N = 6), and if the approach was personalized (17%, N = 5).

Strategies to Enhance Recruitment

During focus groups and one-to-one interviews, participants were asked to offer their opinion on what could be done to improve a researcher’s success in enrolling Asian women in research. Four main approaches were suggested, (1) recruitment should be conducted in the language of the participants, (2) the content of the study materials should be personalized, (3) recruitment should be conducted at group events in the Asian community, and (4) recruitment should be conducted at the time of a previously scheduled medical visit. Each of the four approaches, in effect, provided a solution for the principal barriers identified by the participants (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Strategies and inclusion phrases

One suggested approach was to conduct recruitment efforts in the language of the participants. Fourteen percent (N = 4) explicitly recommended (1) preparing study materials in the language of the target group, (2) translating and using key phrases in English language study documents; and (3) using a recruiter who was fluent in the language of the group to be recruited. A young woman advised: “People like to hear their native language.…even if you don’t speak it perfectly, they are more comfortable and more trusting.”

Participants suggested an approach to overcome the barriers of “mistrust and negative experiences”. This could be done by using personalized recruitment materials. Participants noted that personal instructional content was a key contributor to improving success. Participants (30%, N = 10) suggested that recruitment materials should contain information on the “knowledge to be gained” and the “value of the research” to their reference group. Their comments illustrated the importance of also personalizing the process of research. To tap into the enhancer of the “desire to benefit self” and “benefit others,” participants (17%, N = 5) suggested describing research projects at group events that are organized at churches or social meeting places for the purpose of providing health information.

Finally, as a way to reduce the barrier of “limited time,” participants (13%, N = 4) suggested integrating study enrollment activities with routine or other medical visits. For example, one woman noted “they make it convenient because it’s scheduled on my time.”

Discussion

Our results illustrate that, with few exceptions, the barriers to participation in research are modifiable and enhancers are easily applied. A personal, individualized approach by the recruiter, in a relatively private locale, is preferred over an approach that is public. Our sample was already generally compliant with preventive health practices, and therefore did not necessarily represent women at highest risk or greatest need for intervention to improve their use of preventive health services. Even though our sample was not among those at highest risk, participants reported a main reason to be in research as “getting information for a family member.” Therefore, these participants may deliver vital information to relatives who are at higher-risk for cervical cancer [39, 40].

Language as a barrier is not as easily modifiable as one may presume. Even though we were conducting our study in three languages, participants identified language as a significant deterrent. Differences in dialect increased the cultural divide. The problem of dialect may be reduced if research staff is employed from the target population. This is a method used in community-based participatory research. Accommodating different dialects in a research study may not be practical or economically feasible unless the target group is extremely specific.

Two major reasons for non-participation were the lack of time and inconvenience. These reasons may reflect the considerable value placed by Asian Americans on the work ethics of high productivity and achievement [15]. Simply put, Asian women may consider their time as poorly spent on such activities as research. It is therefore essential that, if possible, an absolute value be associated with research participation. A person’s availability and competing obligations are outside the purview of research teams. However, we have the ability to assist potential study participants to consider time spent as a research participant as “altruistic” and therefore, valuable.

The notion of altruism in the Asian cultures does not necessarily apply to all people. A main reason for participating in research was to “help our family and community.” Participants in the study clearly specified that their beneficence was intended, first for individuals within their immediate family, next for the immediate circle of friends and associates, and then for the cultural group with whom they identified. The notion of the “greater good” radiated out from concentric circles of personal relationships with the nuclear family at the center and the larger world most distantly removed. Recruitment may be enhanced by framing the language of beneficence as directed to self, family, and for the greater good of their cultural social sphere.

Language-Specific Recruitment Materials

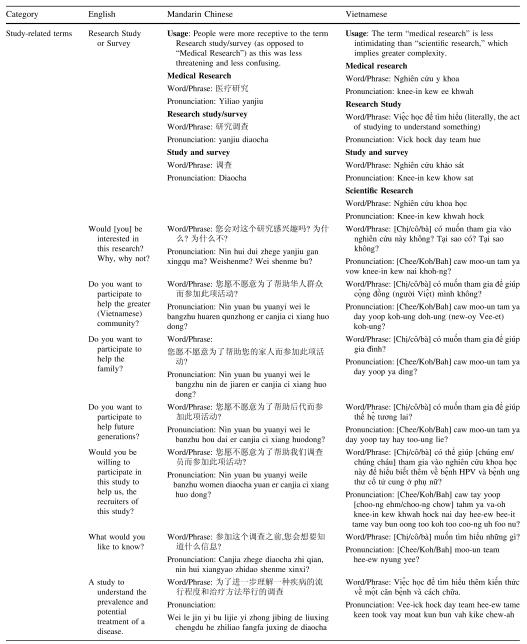

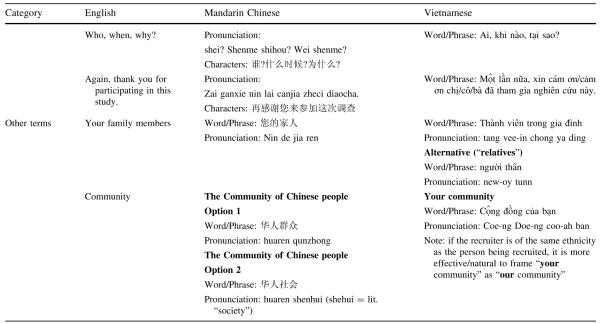

The work of Ahmad et al. [41] with women at risk for breast cancer, supports using written culturally-tailored, language-specific health educational materials to promote screening within a targeted population. To apply the recommendation of our participants we prepared key phrases, excerpted from interviews and matched these with enhancers to participation and validated by participants. These phrases, when translated and used in study materials, may increase enrollment of Asian Americans (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Key words and terms in English with usage in Mandarin Chinese and Vietnamese

Combining strategies can enhance the probability of successful recruitment. The first and most important strategy is to remove the language barriers. All material should be prepared in the language of the target group. Encounters by recruiters and data collectors must be in the language of the participant and preferably in the specific dialect. Research participation will be enhanced if the benefits of research are specified as indirectly or directly related to one’s family or their social sphere. For example, the “greater good” is the good of their community of family, friends, Asian subgroup, and so on, in that order.

Issues to Monitor

Participants were somewhat-to-very confused about the difference between research and medical care. As a strategy, several participants suggested combining medical visits with research enrollment. The suggestion to integrate research study enrollment activities with routine or other medical visits may be efficient and save time, but may also contribute to a woman’s confusion. This may ultimately compromise the integrity of informed consent.

The participants’ reactions to the addition of bio-sampling, was negative. The negative reaction was especially strong if bio-sampling included giving blood. The most poignant objection was fueled by the belief that blood was “too precious to spare.” The reason most often reported, however, was they were not given “a good reason to do so.” This objection may be easily reversed by a concerted effort to explain the ultimate value of such research to self, family, and other Asian women “like herself.”

Limitations

This pilot study allowed us to identify limitations that may need to be addressed before designing and conducting larger definitive clinical trials. The proportion of participants of Chinese ethnicity (65%) challenges our ability to apply findings to women from ethnic backgrounds not included in the sample. The range of ages for our participants was wide, making it difficult to make general statements about any particular age group, but this diversity of age enabled us to capture a broader view of the experiences of the study population.

The initial use of focus groups for data collection was limiting. We found that the richness of the transcript data was quite variable, with some of the focus groups being notably cursory in comparison to individual interviews. We attribute this to the sensitive, private nature of the topic. In addition, the reticence by focus group participants to elaborate on their comments resulted in the interviewers suggesting potential responses and asking if participants might agree. It is possible that this approach either helped participants “find the appropriate words” or implied the “correct” response.

While well suited for an exploratory pilot study and an excellent source of first-hand experiences from participants, collecting data using focus groups has its limitations. It may be cumbersome, time consuming and is not appropriate for clinical trials. The research design must dictate the most appropriate data collection strategy after advantages and disadvantages are weighed. Group interviews may provide a community forum for subjects to discuss women’s health issues and medical research, but they also lend to automatic agreement among members when one participant distinguishes herself as well-spoken or highly informed. Group settings can provide psychological support for a woman commenting on sensitive and personal issues, such as HPV and Pap tests. If the woman’s response garners positive support and acknowledgement from fellow subjects, she may feel reassured in this environment. Other women may perceive this comfort and, in turn, feel more confident in expressing their opinions. In addition, the group interview creates a more dynamic environment for discussion. On the other hand, if a participant perceives that other women are reacting negatively to her comments, she will be less likely to further contribute her opinions. Introverted women may simply affirm the comments of extroverted participants rather than expressing their individual opinion. It is widely recognized that Asian Americans will agree with their family and community to avoid dissension and isolation.

One-on-one interviews may produce more honest responses to questions on sensitive, personal topics. The alternating of focus groups with one-to-interviews corrected the influence of the directed prompts. In general, one-to-one in-depth interviews were more productive of themes and an open exchange of opinions than were focus group interviews. The success of one-to-one encounters punctuates the recommendation that future research recruitment efforts should be as private and personal as possible.

While participants initially felt uncomfortable discussing gynecological issues, this discomfort subsided as discussion proceeded. A majority of the women were sexually active or had had a pap smear (this information should be verified). They were, therefore, familiar with and more or less willing to discuss their experience with gynecological exams. Subjects demonstrated apprehension in discussing the sexual health of their daughters. Subjects assumed that their daughters were not sexually active and therefore did not need the HPV vaccine. Also, they presumed that vaccination might give license to promiscuity.

In addition, comfort levels are also dependent on the ability of the interviewer to create a rapport with the subject. Unlike group interviews, individual interviews will not illustrate the importance of family and community in decisions regarding sexual health and medical research. Since Asian Americans significantly value community relationships, individual interviews may not capture the contribution of this socio-cultural factor.

Finally, because the sample size is small (n = 30) one must be cautious about generalizing to the larger population and thus presents the need to test these findings in clinical trials.

Future Directions

The strategies generated from our work can be employed to facilitate recruitment of Chinese and Vietnamese American women for cancer control research. This pilot provides practical guidelines and specific techniques for recruiting Asian women into cancer control research. The next steps should test the extent to which the inclusion of key phrases and approaches may improve recruitment for research involving bio-sampling. The cultural competency of research recruiters is essential to engage the under-studied population of Asian American women into research. Culturally appropriate research will require additional resources and additional costs of time and money. However, the ultimate benefit to science from improved validity and generalizability will outweigh these costs.

A long term application of this study is to increase participation by Asian women in medical research, and to explore the transferability of strategies identified in the tables. Among the recommended strategies, one must first remove language barriers and preferably use specific dialects during recruitment, enrollment and data collection. Second, one must specify if benefits are indirectly or directly related to the family or cultural group. Researches should expect that potential participants will be highly motivated to enroll in a study with these benefits. The strategies proposed by this pilot should first be tested among a similar population of women who are sought as participants in research involving prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. The phrases contained in both Tables 3 and 4 can be readily used in future studies, even if the research study recruiter does not speak fluently Chinese or Vietnamese. One may simply point to the corresponding statement on the table to ask the question or give instructions.

Berger and Luckman [42] describe the social construction of reality as the process in which persons and groups interacting, together form, over time, concepts or mental representations of each other’s actions. These concepts eventually become habituated into reciprocal roles played by the actors in relation to each other. Asian women at risk for cervical cancer play an important role in the process of creating scientific reality. Our knowledge and experience as clinicians and researchers methodically combined with their knowledge and beliefs about their health needs and culture may help embed research participation into the fabric of their culture society. The social group of Asian women will ultimately benefit from the individual’s participation in scientific inquiry.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a Pilot Grant from the Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania which was funded, in part, by a grant with the Pennsylvania Department of Health. The Pennsylvania Department of Health specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations, or conclusions. The authors also wish to thank Ying-Chu Chen, James Ming Chu, and Natalie Shih for translation assistance, and Shainy Thaibarambil and Dr. Nino Vittorio from the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, Health Center #2 for facilitation of participant recruitment.

References

- 1.Munoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S, et al. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer [see comment] N Engl J Med. 2003;348(6):518–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(5):1167–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI28607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Cancer Society . Cancer facts and figures 2005. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Cancer Society . Cancer facts and figures 2007. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller B, Kolonel L, Bernstein L, et al. Racial/ethnic patterns of cancer in the United States 1988–1992. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda: 1996. NIH Pub. No. 96–4104. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status [see comment] CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54(2):78–93. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yi JK. Are Asian/Pacific Islander American women represented in women’s health research? Women’s Health Issues. 1996;6(4):237–8. doi: 10.1016/1049-3867(96)00013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang L-F, Tait AR, Polley LS. Demographic differences between consenters and non-consenters in an obstetric anesthesiology clinical trial. Int J Obstet Anesthesiol. 2004;13:159–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Des Jarlais G, Kaplan CP, Haas JS, Gregorich SE, Perez-Stable EJ, Kerlikowske K. Factors affecting participation in a breast cancer risk reduction telephone survey among women from four racial/ethnic groups. Prev Med. 2005;41:720–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly M, Ackerman PD, Ross LF. The participation of minorities in published pediatric research. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(6):777–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hussain-Gambles M, Atkin K, Leese B. South Asian participation in clinical trials: the views of lay people and health professionals. Health Policy. 2006;77:149–65. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hussain-Gambles M. South Asian patients’ views and experiences of clinical trial participation. Family Pract. 2004;21:636–42. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussain-Gambles M. Ethnic minority under-representation in clinical trials: whose responsibility is it anyway? J Health Organ Manage. 2003;17:138–45. doi: 10.1108/14777260310476177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong P, Chienping FL, Nagasawa R, Lin T. Asian Americans as a model minority: self-perceptions and perceptions by other racial groups. Soc Perspect. 1998;41(1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brugge D, Kole A, Lu W, Must A. Susceptibility of elderly Asian immigrants to persuasion with respect to participation in research. J Immigrant Health. 2005;7(2):93–101. doi: 10.1007/s10903-005-2642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Office of Minority Health Asian Americans profile. Internet Web Page http://www.omhrc.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=1&lvlID=5. Accessed 27 June 2006.

- 18.Miller B. Racial/ethnic patterns of cancer in the United States 1988–1992. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Census 2000 Factfinder Results (Philadelphia County) 2000 www.factfinder.census.gov. Updated Last Updated Date. Accessed 5 March 2010.

- 20.Barnes JS, Bennett CE. The Asian population: 2000. US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau; 2/2002–2002. CK2BR/01–16, US Census Report. [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Census Bureau Census 2000 factfinder results (SE Pennsylvania) Internet web site www.factfinder.census.gov. Accessed 13 Dec 2005.

- 22.Killien M, Bigby JA, Champion V, et al. Involving minority and underepresented women in clinical trials: The National Centers of Excellence in Women’s Health. J Women’s Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9:1061–70. doi: 10.1089/152460900445974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robertson NL. Clinical trial participation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 1994;74:2687–91. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19941101)74:9+<2687::aid-cncr2820741817>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCarthy CR. Historical background of clinical trials involving women and minorities. Acad Med. 1994;69:695–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199409000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnstone E, Sandler JR, Addauan-Andersen C, Sohn SH, Fujimoto VY. Asian women are less likely to express interest in fertility research. Fertil Steril. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.08.011. Article in Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Culley L, Hudson N, Raport F. Using focus groups with minority ethnic communities: researching infertility in British South Asian communities. Qual Health Res. 2007;17:102–12. doi: 10.1177/1049732306296506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin HB, Bruno R. Language use and English-speaking ability: 2002. US Census Bureau, US Department of Commerce; 2003. CK2BR 29. [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Census Bureau Census 2000 Factfinder Results (Nationwide) Internet web site www.factfinder.census.gov. Accessed 30 Oct 2005.

- 29.Vari-Cartier P. Development and validation of a new instrument to assess readability of Spanish prose. Mod Lang J. 1981;65(2):141–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matial-Carello L, Chavez G, Negron G, Canino G, Aguilar-Gaxola S, Hoppe S. The Spanish translation and cultural adaptation of five mental health outcome measures. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2003;27:291–313. doi: 10.1023/a:1025399115023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brislin RW. Back translation for cross cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1970;1:185–216. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flesch R. A new readability yardstick. J Appl Psychol. 1948;32:221–33. doi: 10.1037/h0057532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tran TV, Dung N, Conway K. A cross-cultural measure of depressive symptoms among Vietnamese Americans. Soc Work Res. 2003;27(1):56. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manning P, Cullum-Swan B. Narrative, content, and semiotic analysis. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, editors. Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials Handbook of qualitative methods. Sage; Thousand Oaks: 1998. pp. 246–273. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krippendorf K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. 2nd Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strauss A, Corbin S. Basics of qualitative research. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd Sage; Thousand Oaks: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagayama Hall GC, Okazaki S. Asian American psychology: the science of lives in context. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang W, Ta VM. Social connections, immigration-related factors, and self-rated physical and mental health among Asian Americans. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(12):2104–12. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahmad F, Cameron J, Stewart DE. A tailored intervention to promote breast cancer screening among South Asian immigrant women. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:575–86. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berger PL, Luckmann T. The social construction of reality: a treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Anchor Books; Garden City: 1966. [Google Scholar]