Summary

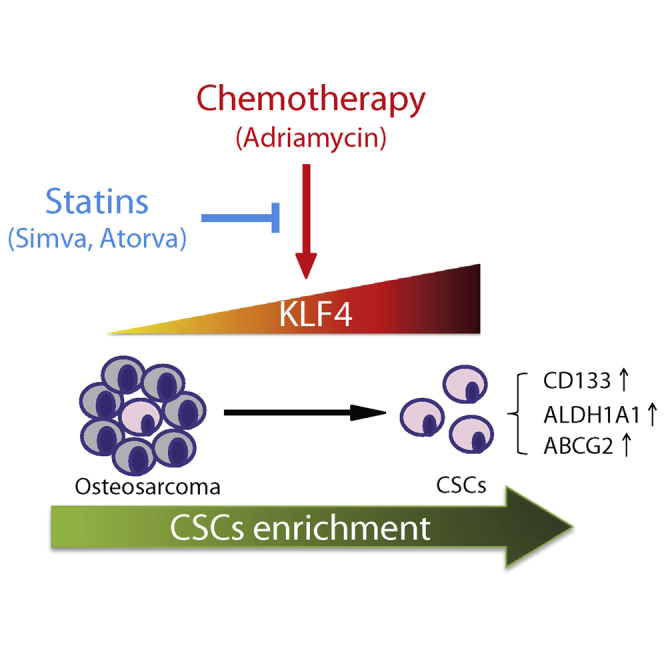

Adriamycin-based combination chemotherapy is the standard first-line treatment for osteosarcoma, but tumor recurrence and metastasis occurs in most cases. Recent evidence suggests that microenvironmental stress such as chemotherapy can lead to the enrichment of cancer stem cells (CSCs), which result in cancer metastasis, recurrence, and drug resistance. However, the exact mechanisms underlying this phenomenon and how to target CSCs are still open questions. Herein, we report that Adriamycin treatment induces a stem-like phenotype and promotes metastatic potential in osteosarcoma cells through upregulating KLF4. KLF4 knockdown blocks Adriamycin-induced stemness phenotype and metastasis capacity. We further screen that statins remarkably reverse Adriamycin-induced CSC properties and metastasis by downregulating KLF4. Most strikingly, simvastatin severely impaired Adriamycin-enhanced tumorigenesis of KHOS/NP cells in vivo. These data suggest that Adriamycin-based chemotherapeutics may simulate CSCs through activation of KLF4 signaling and that selective inhibition of KLF4 with statins should be considered in the development of osteosarcoma therapeutics.

Keywords: KLF4, Adriamycin, cancer stem cells, metastasis, osteosarcoma, statins

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Adriamycin treatment induces a stemness phenotype in osteosarcoma cells

-

•

KLF4 is a key transcriptional regulator of ADR-induced osteosarcoma cancer stemness

-

•

Simvastatin reverses ADR-induced CSC properties by downregulating KLF4

-

•

Simvastatin abolishes ADR-enhanced tumorigenesis of KHOS/NP cells in vivo

In this article, Ying, He, and colleagues show that Adriamycin-based chemotherapeutics may simulate CSCs through activation of KLF4 signaling and that selective inhibition of KLF4 with statins, the cholesterol-lowering agents, remarkably reverse the Adriamycin-induced CSC properties and metastasis in osteosarcoma. Their findings suggest that targeting of KLF4 with statins may be considered in the development of osteosarcoma therapeutics.

Introduction

Osteosarcoma is an aggressive tumor of growing bones that is encountered in children and adolescents and is characterized by a high malignant and metastatic potential (Kansara et al., 2014). Adriamycin (doxorubicin; ADR) came into use for the treatment of osteosarcoma in the early 1970s. The agent intercalates into DNA and induces topoisomerase II-mediated single- and double-strand breaks in DNA. It has been reported to be the most effective agent for the treatment of osteosarcoma. Currently, ADR-based combination chemotherapy (ADR with methotrexate, cisplatin, and ifosfamide) is the standard first-line treatment for osteosarcoma patients. However, despite the advances achieved with multidisciplinary application of ADR-based chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgical ablation of primary tumors, the improved cure rate reported initially has not changed over those of the 1970s (Chou and Gorlick, 2006). Approximately 40%–50% of patients develop pulmonary metastases after receiving seemingly effective multidisciplinary chemotherapy. Drug resistance almost invariably occurs, limiting the therapeutic effectiveness of ADR. ADR-based chemotherapy shrinks the tumor mass but may also exert a selective pressure on the tumor cells, leading to outgrowth of the fittest surviving cell clones.

There is increasing awareness that heterogeneous osteosarcomas contain a subpopulation of cancer stem cells (CSCs) with enhanced tumorigenicity and chemoresistance (Basu-Roy et al., 2013, Liu et al., 2011). These cells are endowed with self-renewal abilities and can drive tumor growth, dissemination, and recurrence after chemotherapy. The existence of CSCs is believed to be responsible for the failure of clinical chemotherapy for osteosarcoma. We have previously shown that CD49F−CD133+ osteosarcoma cells had an inhibited osteogenic fate, with osteosarcoma-initiating cell-like properties of self-renewal, strong tumorigenicity, strong lineage differentiation ability, and high chemoresistance (Ying et al., 2013). Moreover, other studies have also reported that some subpopulations of osteosarcoma cells express prospective CSC markers, including CD133, CD117, Stro-1, and ALDH (Adhikari et al., 2010, Fujii et al., 2009, Honoki et al., 2010, Tirino et al., 2011). CSCs can result from oncogenic transformation of normal stem cells or acquisition of stemness-related properties by non-stem cancer cells in response to microenvironmental signals (Friedmann-Morvinski and Verma, 2014). Several studies have suggested that chemotherapy can promote or enhance a CSC-like phenotype in differentiated tumor cells (Chen et al., 2012, Liu et al., 2013, Rizzo et al., 2011). It has been reported that ADR chemotherapy induces a phenotypic stem-like cell transition in osteosarcoma cells via WNT/β-CATENIN signaling (Martins-Neves et al., 2016). Consistent with this finding, in this study we also show that exposure to ADR treatment induces a stemness and metastasis phenotype in osteosarcoma cells. Hence, multiple connections likely exist between ADR chemotherapy and the enrichment of CSCs. However, the exact mechanisms underlying this phenomenon and how to target CSCs are still open questions.

Remarkably, the process of dedifferentiation or reprogramming of somatic cells by Yamanaka factors (OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, and C-MYC), many of which are oncogenes, offers a new insight into CSCs (Schwitalla et al., 2013, Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006). Almost any differentiated cell can be sent back in time to a pluripotent state by expressing the appropriate transcription factors. Therefore, OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, and C-MYC are critical factors in the creation of induced pluripotent stem cells. In fact, a previous study revealed the introduction of these defined reprogramming factors (OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, and C-MYC) into MCF-10A nontumorigenic mammary epithelial cells could transform the bulk of the cells into tumorigenic CD44+CD24low cells with CSC properties. Ectopic coexpression of C-MYC and HER2 in breast cancer cells led to the acquisition of a self-renewing phenotype (Nair et al., 2014). SOX2 was also demonstrated to maintain the self-renewal ability of tumor-initiating cells in osteosarcoma (Basu-Roy et al., 2013). In addition, KLF4 displays a potent oncogenic role in mammary tumorigenesis, likely by maintaining stem cell-like features (Yu et al., 2011). Moreover, by activating an exogenous OCT-4 promoter in primary osteosarcoma cells, OCT-4/GFP+ cells displayed properties of cancer-initiating cells (Levings et al., 2009). In view of this, we hypothesize that OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, and C-MYC may have important roles in regulating the ADR-enhanced stemness and metastasis phenotype in osteosarcoma cells.

In this study we demonstrated that ADR, which is used for osteosarcoma treatment, induces stemness properties in differentiated osteosarcoma cells through activation of KLF4 signaling. Moreover, we found that statins, the cholesterol-lowering agents, remarkably reverse the ADR-induced CSC properties and metastasis in osteosarcoma by downregulating KLF4. These results add valuable information regarding the reprogramming of stemness networks in osteosarcoma that may contribute to therapy failure, and suggest that targeting of KLF4 with statins may be another strategy to improve suppression of this elusive stem cell population.

Results

ADR Enhances Cancer Stemness and Metastasis of Osteosarcoma Cells

To study whether ADR may promote CSC-like properties in osteosarcoma cells, we first generated a dose-response curve with increasing concentrations of ADR in KHOS/NP and U2OS cell lines and in primary osteosarcoma cells (MDOS-20). As shown in Figure 1A, ADR decreased cell proliferation in all osteosarcoma cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. To avoid obvious cytotoxicity, we then chose a 20% inhibitory concentration (IC20) of ADR for each of the cell lines to use in subsequent studies (KHOS/NP cells: 50 nM; U2OS and MDOS-20 cells: 100 nM). We then explored whether ADR treatment induced an increase in the proportion of CD133+ cells, a CSC marker for osteosarcoma. As shown in Figure 1B, ADR treatment for 24 hr remarkably increased the ratio of CD133+ cells in all three osteosarcoma cell cultures, including KHOS/NP, U2OS, and primary MDOS-20 cells. To better characterize ADR-induced cancer stemness, we further performed a tumorsphere assay, which is ideal for identifying CSC properties as it highlights the capacity of cells for self-renewal and their ability to form a three-dimensional sphere, similar to a tumor (Lonardo et al., 2012). Compared with vehicle controls, osteosarcoma cells showed on average 2-fold more sphere-formation capacity after ADR exposure (Figure 1C). Moreover, ADR also progressively enhanced the number of floating spheres in a dose-dependent manner (Figure S1), suggesting that CSC activities are enriched in ADR-treated cells. Additionally we assessed the mRNA expression levels of several osteosarcoma stem cell marker genes, namely CD133 (Tirino et al., 2011), ALDH1A1 (Wang et al., 2011), and ABCG2 (Di Fiore et al., 2009) using qRT-PCR. The results showed that gene expression of CD133 exhibited the highest fold change compared with untreated cells (KHOS/NP 2.70-fold, U2OS 13.64-fold, and MDOS-20 2.30-fold). The expression of ALDH1A1 and ABCG2 was also upregulated upon ADR treatment (Figure 1D), and the protein levels of CD133 were also upregulated by ADR in osteosarcoma cells (Figure S2). We further determined whether enhanced self-renewal and stemness activity in ADR-treated cells were correlated with increased expression of stem/progenitor cell-associated genes using a microarray analysis. As expected, molecules involved in regulation of self-renewal signaling pathways were upregulated in ADR-treated KHOS/NP cells compared with control cells, including those in the NOTCH, WNT, and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) pathways (Figure 1E), indicating that a stem cell-like gene expression profile might be induced by ADR treatment in the osteosarcoma cells. Together, these results indicated that ADR could enhance the cancer stemness of osteosarcoma cells.

Figure 1.

ADR Induces Cancer Stemness of Osteosarcoma Cells

(A) The osteosarcoma cells were treated with different concentrations of ADR for the indicated times, followed by a growth inhibition assessment using an sulforhodamine B assay. Results are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 versus control group on day 1. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 versus control group on day 3. δp < 0.05, δδp < 0.01, δδδp < 0.001, versus control group on day 5.

(B) Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of the CD133+ subpopulation of osteosarcoma cells treated with the indicated concentrations of ADR for 24 hr. KHOS/NP, U2OS, and MDOS-20 cells were treated with 50, 100 or 100 nM ADR, respectively. Results are represented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

(C) KHOS/NP, U2OS, and MDOS-20 cells treated with the indicated concentrations of ADR for 7 days were subjected to a tumor sphere-formation assay. Left: representative images of osteospheres. Right: quantification of the assay. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 versus control.

(D) qRT-PCR was used to detect the mRNA level of osteosarcoma stem cell markers (CD133, ALDH1A1, and ABCG2). KHOS/NP, U2OS, and MDOS-20 cells were treated with 50, 100, or 100 nM ADR for 24 hr. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 versus control.

(E) Heatmap depicting the upregulation of the genes involved in the NOTCH, WNT, and TGF-β signaling pathways after ADR treatment in KHOS/NP cells. The color bar represents the expression ratio on a log2 scale (ADR versus control).

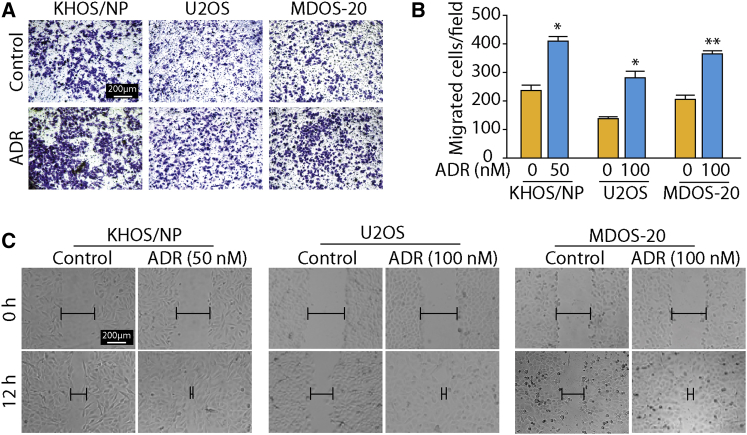

Increasing evidence suggests that metastatic capacity is closely linked to the CSC phenotype (Li et al., 2007). Therefore, we investigated the effect of ADR on osteosarcoma metastasis using Transwell and scratch assays. The migration assays showed that, compared with the control cells, ADR-exposed osteosarcoma cells traversed more efficiently into the lower portion of the Transwell chamber (Figures 2A and 2B). Similarly, the ability of the cells in the ADR treatment group to repair the cell scratch was significantly higher than that of the cells in the control group (Figure 2C), indicating that ADR may promote the migration capacity of osteosarcoma cells. Taken together, our results clearly suggest that ADR can enhance cancer stemness and metastasis in osteosarcoma cells.

Figure 2.

ADR Induces Metastasis of Osteosarcoma Cells

(A and B) Transwell migration assays were used to assess the migration ability of osteosarcoma cells. Osteosarcoma cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of ADR for 24 hr during the migration assay. Representative images of migrated cells from three independent experiments are shown in (A) and the results are summarized in (B). Results are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 versus control.

(C) Scratch assay of osteosarcoma cells grown in the presence or absence of ADR. KHOS/NP, U2OS, and MDOS-20 cells were treated with 50, 100, or 100 nM ADR, respectively, for 12 hr. Representative images of migrated cells from three independent experiments are shown.

KLF4 Is Critical for ADR-Enhanced Cancer Stemness and Metastasis

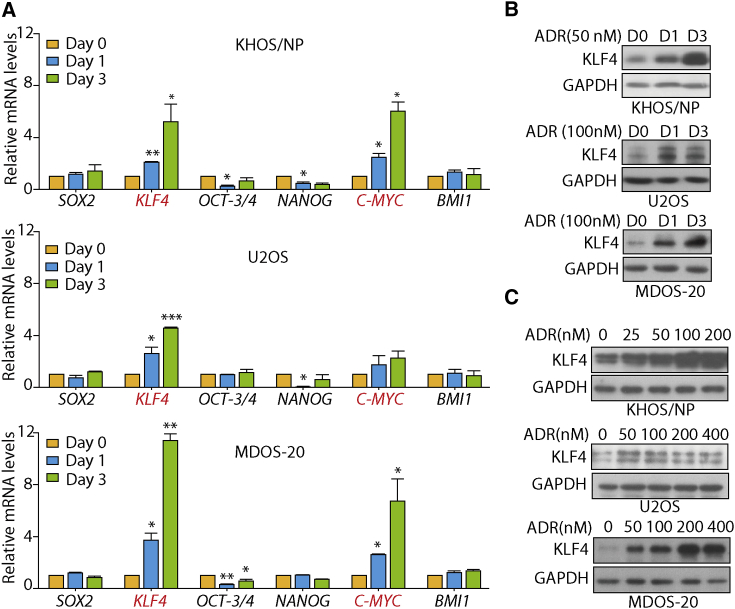

It has been well documented that stemness-associated genes, including SOX2, KLF4, OCT-3/4, NANOG, C-MYC, and BMI1, are essential to maintain the pluripotency of the stem cell phenotype (Fong et al., 2008, Loh et al., 2006, Moon et al., 2011, Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006). Moreover, there is a wealth of evidence to suggest that overexpression of these genes occurs in human malignancies and confers CSC characteristics (Abdouh et al., 2009, Ibrahim et al., 2012, Leis et al., 2012). Therefore, we wondered whether these genes may contribute to ADR-induced cancer stemness. To test this, we used qRT-PCR to examine the effect of ADR on the mRNA expression levels of these genes. As shown in Figure 3A, the mRNA levels of SOX2, NANOG, OCT3/4, and BMI1 were not upregulated by ADR treatment in KHOS/NP, U2OS, and primary MDOS-20 cells. However, ADR treatment significantly upregulated the transcription level of KLF4 in a time-dependent manner in all three osteosarcoma cells, whereas an elevated expression of C-MYC was only observed in KHOS/NP and MDOS-20 cells, not in U2OS cells. As KLF4 is indispensable for the maintenance of stem cells, we then focused on its function in ADR-enhanced cancer stemness. Consistently, the protein expression levels of KLF4 were obviously upregulated after ADR treatment in a time- and dose-dependent manner in all three osteosarcoma cell lines (Figures 3B and 3C). These data suggest that KLF4 may play a critical role in ADR-enhanced cancer stemness and metastasis.

Figure 3.

ADR Selectively Upregulates KLF4 Expression at the mRNA and Protein Levels in All Osteosarcoma Cells

(A) KHOS/NP, U2OS, and primary MDOS-20 cells were exposed to 50, 100, or 100 nM ADR, respectively, for 24 hr or 72 hr. qRT-PCR was used to detect the mRNA level of stem cell-related markers (SOX2, KLF4, OCT3/4, NANOG, C-MYC, and BMI1). Error bars in all panels represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 versus control.

(B) Western blotting showing the expression levels of KLF4 protein in osteosarcoma cells following ADR treatment for the indicated times. KHOS/NP, U2OS, and primary MDOS-20 cells were exposed to 50, 100, or 100 nM ADR, respectively.

(C) Western blotting showing the expression levels of KLF4 protein in osteosarcoma cells following treatment with increasing concentration of ADR for 24 hr. (B and C) GAPDH was the loading control. Representative images from three independent experiments are shown.

Depletion of KLF4 Reverses ADR-Enhanced Cancer Stemness and Metastasis

To determine whether upregulation of KLF4 is indeed responsible for the ADR-promoted osteosarcoma stem cell phenotype, we used small interfering RNA (siRNA) to knock down KLF4 expression in KHOS/NP cells. As shown in Figure 4A, the expression of siKLF4 #1 and #2 obviously reduced KLF4 protein expression in KHOS/NP cells compared with the scramble controls. KLF4 silencing significantly inhibited ADR-induced enrichment of CD133+ cells in the osteosarcoma cells, as indicated by the drop in the percentage of CD133+ cells from 33.8% ± 6.97% in ADR-treated control cells to 9.72% ± 0.89% and 18.0% ± 1.29% in ADR-treated siKLF4 #1 and #2 cells (Figure 4B), indicating that KLF4 silencing might inhibit the stemness induced by ADR. In addition, KLF4 suppression also greatly prevented ADR-increased sphere formation, decreasing it to levels comparable with those observed in control groups (Figure 4C). Similarly, the KLF4 siRNAs effectively attenuated the transcriptional level of stem cell-related markers (CD133, ABCG2, and ALDH1A1) induced by ADR treatment (Figure 4D). These results clearly suggest that KLF4 activation plays a key role in ADR-enhanced cancer stemness.

Figure 4.

KLF4 Is Involved in Regulating ADR-Induced Osteosarcoma Stemness

(A) Western blotting analysis of KLF4 expression. KHOS/NP cells were transfected with KLF4 siRNA or Mock (control siRNA) for 48 hr, followed by treatment with ADR (50 nM) for 24 hr.

(B) KHOS/NP cells transfected with KLF4 siRNA or Mock (control siRNA) were treated with ADR (50 nM) for 24 hr, and the percentage of the CD133+ subpopulation of osteosarcoma cells was determined by FACS analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

(C) KHOS/NP cells transfected with KLF4 siRNA or Mock (control siRNA) were treated with ADR (50 nM) for 7 days. The number of osteospheres per 100,000 cells seeded was calculated. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗∗p < 0.01 versus untreated Mock cells. ##p < 0.01 versus ADR-treated Mock cells.

(D) qRT-PCR was used to detect the mRNA level of osteosarcoma stem cell markers. KHOS/NP cells transfected with KLF4 siRNA or Mock (control siRNA) were treated with ADR (50 nM) for 24 hr. Results are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 versus untreated Mock cells. #p < 0.05 versus ADR-treated Mock cells.

(E) Quantification of KHOS/NP cells transfected with KLF4 siRNA or Mock (control siRNA) that migrated following treatment with ADR (50 nM) for 24 hr. Representative fields of cells from three independent experiments that have migrated across the membrane are shown on the left, and the results are summarized on the right. ∗p < 0.05 versus untreated Mock cells. ##p < 0.01 versus ADR-treated Mock cells.

Next, we sought to delineate whether activation of KLF4 is involved in the ADR-induced metastasis potential. Notably, silencing KLF4 almost completely abrogated ADR-promoted cell migration (Figure 4E) and the wound-closure capability of KHOS/NP cells (Figure S3). Taken together, these data suggest that depletion of KLF4 significantly reverses ADR-enhanced osteosarcoma cancer stemness and metastasis.

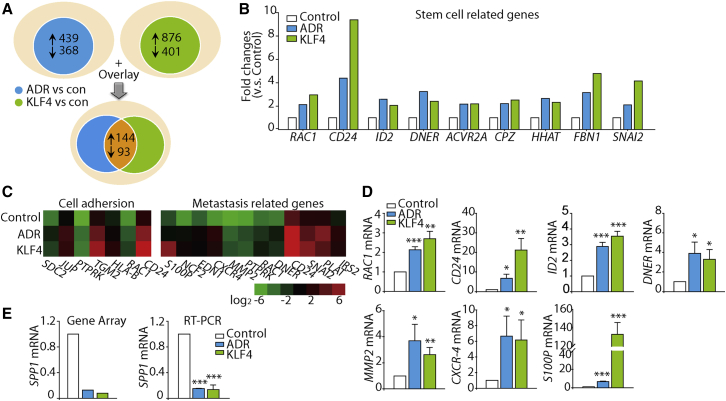

KLF4 Is a Transcriptional Regulator of ADR-Enhanced Cancer Stemness

To identify patterns of gene expression that might provide a molecular explanation for the role of KLF4 in modulating osteosarcoma cancer stemness after ADR treatment, we compared gene expression profiles of KHOS/NP cells treated with vehicle, ADR, and KLF4 overexpression using microarray analysis. Genes whose expression differed by ≥2-fold in ADR-treated versus control cells were identified, with 439 genes upregulated and 368 genes downregulated. Similarly, we compared gene expression profiles of KLF4-overexpressing cells and control cells, and found 1,277 genes that were altered (2-fold difference; 876 genes upregulated, 401 genes downregulated). Following overlay analysis, approximately 273 genes were found and then clustered (Figure 5A and Table S1). In this cluster, we found that several genes associated with cancer stemness were upregulated, such as RAC1, CD24, ID2, DNER, ACVR2A, CPZ, HHAT, FBN1, and SNAI2 (Figure 5B), indicating that both ADR treatment and KLF4 overexpression induced the stemness phenotype of KHOS/NP cells. Genes associated with cell motility and metastasis were also elevated under both ADR treatment and KLF4 overexpression (Figure 5C). The differential expression of representative genes was validated with a real-time RT-PCR analysis, and the results closely mirrored the expression levels for these genes assessed by the microarray analysis (Figure 5D). Intriguingly, we also found that the osteoblast differentiation marker SPP1 was decreased in both KLF4 overexpressing and ADR-treated cells in comparison with the vehicle-treated control cells (Figure 5E). Collectively these data imply that KLF4 may modulate these gene expression profiles, thus contributing to the enhanced osteosarcoma cancer stemness characteristic induced by ADR.

Figure 5.

Mechanisms Underlying the Induction of KLF4 by ADR in Regulation of Osteosarcoma Cancer Stemness

(A) Schematic representation of the gene expression profile comparisons of KHOS/NP cells (2-fold difference; blue: ADR versus control; green: KLF4 versus control) and the overlay analysis.

(B) Microarray data of upregulated stem cell/progenitor marker genes in KHOS/NP cells (blue: ADR versus control; green: KLF4 versus control).

(C) Heatmap of genes correlated with cell motility.

(D) Validation of the microarray data of (C) and (B) using qRT-PCR. Selected genes from different functional groups were validated with qRT-PCR. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 versus control. Data are presented as mean ± SD; at least three independent experiments were performed.

(E) Microarray analysis and qRT-PCR detection of SPP1 mRNA expression in KHOS/NP cells. The gene expression levels were validated with qRT-PCR. ∗∗∗p < 0.001 versus control. qRT-PCR data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

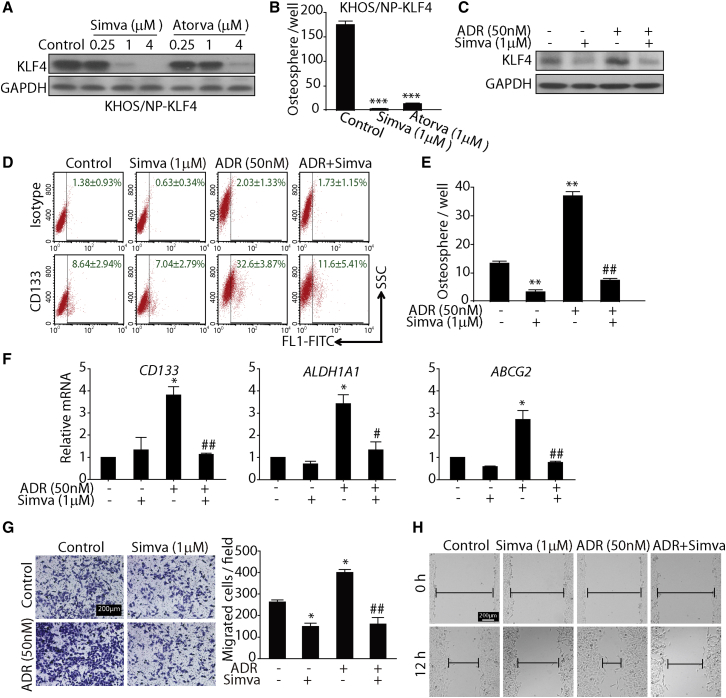

Statins Inhibit the ADR-Induced Cancer Stemness and Metastasis Traits of Osteosarcoma Cells by Targeting KLF4

The aforementioned findings collectively demonstrated that ADR could enhance the stemness and metastasis traits of osteosarcoma cells by upregulating KLF4 expression. In contrast, these acquired phenotypes were attenuated with concomitant use of KLF4 siRNA during chemotherapy, indicating that KLF4 is a potential target to overcome osteosarcoma stemness and tumor metastasis. We subsequently established a stable cell line ectopically expressing KLF4 and then attempted to screen candidate compounds to target KLF4 and inhibit osteosarcoma cancer stemness. To our surprise we found that statins, the cholesterol-lowering agents, reduced the expression of KLF4 in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6A). We then evaluated the anti-sphere-forming capability of statins in KLF4-overexpressing KHOS/NP cells. As shown in Figure 6B, both simvastatin and atorvastatin effectively reduced the increased sphere formation mediated by KLF4 overexpression, indicating that statins may target KLF4 to inhibit its expression and thereby reduce the CSC properties in osteosarcoma cells.

Figure 6.

Statins Inhibit KLF4 Expression and Osteosarcoma Cancer Stemness Traits In Vitro

(A) Transduction of KHOS/NP cells with a lentiviral vector encoding the cDNA of KLF4 at an MOI of 10. Then 72 hr after transduction, KHOS/NP-KLF4 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of simvastatin and atorvastatin for 24 hr. Western blotting was performed to detect KLF4 and GAPDH expression.

(B) KHOS/NP-KLF4 cells were treated with simvastatin (1 μM) or atorvastatin (1 μM) for 7 days. The number of osteospheres per 100,000 cells seeded was calculated. ∗∗∗p < 0.001 versus control.

(C) Western blotting analysis of KLF4 expression in KHOS/NP cells treated with ADR (50 nM), simvastatin (1 μM), or both drugs in combination for 24 hr.

(D) FACS analysis of the CD133+ subpopulation of osteosarcoma cells treated with ADR (50 nM), simvastatin (1 μM), or both drugs in combination for 24 hr. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Representative images are shown.

(E) Simvastatin completely blocked the sphere formation induced by ADR. KHOS/NP cells were treated with ADR (50 nM) alone, simvastatin (1 μM) alone, or both drugs in combination for 7 days during osteosphere formation. ∗∗p < 0.01 versus with untreated cells. ##p < 0.01 versus with ADR-treated cells.

(F) qRT-PCR was used to detect the mRNA level of osteosarcoma stem cell markers. KHOS/NP cells were treated with ADR (50 nM) alone, simvastatin (1 μM) alone, or both drugs in combination for 24 hr. ∗p < 0.05 versus untreated group. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 versus ADR group.

(G and H) Transwell migration assay (G) and scratch assay (H) of KHOS/NP cells treated with ADR (50 nM), simvastatin (1 μM), or both drugs in combination for 24 hr. Representative images from three independent experiments are shown. ∗p < 0.05 versus with untreated cells. ##p < 0.01 versus with ADR-treated cells.

Error bars in all bar graphs represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

We then tested whether the effect of simvastatin could be reproduced in ADR-induced osteosarcoma cancer stemness models. As expected, simvastatin could effectively reverse ADR-enhanced KLF4 protein expression (Figure 6C). Moreover, simvastatin could obviously block the ability of ADR to enhance the population of CD133+ cells; the percentage of CD133-positive cells decreased from 32.6% ± 3.87% to 11.6% ± 5.41% (ADR versus ADR plus simvastatin) (Figure 6D). Similar responses were also observed in sphere cultures of osteosarcoma cells, as simvastatin significantly abrogated the increase in the number of spheres induced by ADR (Figure 6E). In addition, simvastatin also reduced the expression of specific stem cell markers as determined by qRT-PCR (Figure 6F). Altogether, these findings demonstrate that simvastatin can reduce the osteosarcoma cancer stemness induced by ADR treatment in vitro.

Subsequently, we evaluated whether simvastatin influenced the ADR-induced tumor metastasis trait. As shown in Figures 6G and 6H, simvastatin significantly ameliorated the increased scratch repair and migration abilities induced by ADR in osteosarcoma cells. Collectively these data suggest that simvastatin can abrogate ADR-enhanced osteosarcoma cancer stemness and metastasis by inhibiting KLF4.

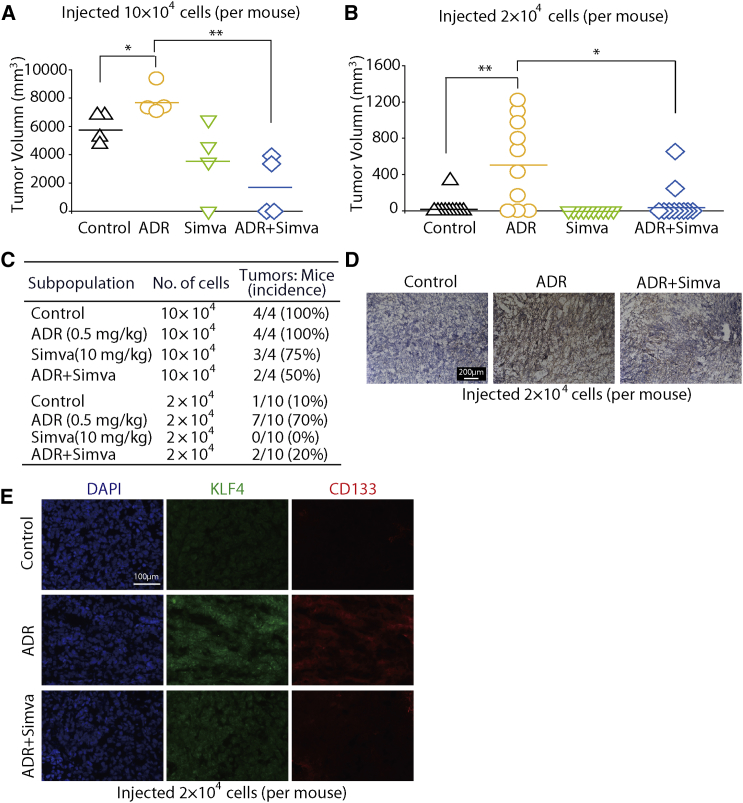

Simvastatin Reverses ADR-Increased Tumorigenesis in an Osteosarcoma Xenograft Model

To investigate whether ADR could promote cancer development in vivo, we established a BALB/c (nu/nu) mouse model subcutaneously injected with KHOS/NP cells following ADR treatment. We injected 10 × 104 or 2 × 104 KHOS/NP cells into mice. As expected, four out of four mice injected with 10 × 104 cells generated tumors. However, of the ten mice injected with 2 × 104 cells, only one generated a tumor (Figures 7A and 7B), which indicated that a reduction in cell number for transplantation (from 10 × 104 to 2 × 104 cells) was associated with a reduced tumor incidence (from 100% to 10%). Interestingly, ADR treatment resulted in a large increase in the tumor incidence in the groups injected with 2 × 104 cells, from 10% in the control group to 70% in the ADR treatment group. These results support the proposal that ADR can promote tumorigenesis of osteosarcoma cells.

Figure 7.

Simvastatin Reverses the ADR-Enhanced Tumorigenesis

(A and B) Scatterplots of tumor volume. Xenograft models using NOD/SCID mice with subcutaneously injected KHOS/NP cells were used to evaluate the in vivo effects of simvastatin on ADR-induced tumorigenesis. n = 4 in 10 × 104 cells group and n = 10 in 2 × 104 cells group. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

(C) Summary of xenograft tumor formation in NOD/SCID mice after different treatment.

(D and E) Simvastatin suppressed ADR-induced KLF4 expression in KHOS/NP human xenograft models. KHOS/NP xenografts were established by injecting 2 × 104 cells subcutaneously into nude mice. (D) KLF4 expression in tumor tissues from different groups was determined with immunohistochemical staining. (E) Immunofluorescence analysis with antibodies targeting CD133 and KLF4; nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. In both (D) and (E) the sample in the simvastatin group is vacant, and representative images of other groups' osteosarcoma samples are shown. Representative images from three independent experiments are shown.

We also tested the effect of simvastatin on the ADR-enhanced tumorigenesis of KHOS/NP cells in vivo. As shown in Figures 7A and 7C, of the groups injected with 10 × 104 cells, tumor incidence in the ADR plus simvastatin group (50%) was much lower than that in the ADR group (100%). In the groups injected with 2 × 104 cells, simvastatin also significantly inhibited the tumor incidence, from 70% (7/10) in the ADR treatment group to 20% (2/10) in the ADR plus simvastatin group (Figures 7B and 7C). These data indicate that simvastatin can significantly inhibit ADR-enhanced tumorigenesis.

We further analyzed whether the expression levels of KLF4 were regulated by ADR and simvastatin in the KHOS/NP xenografts using immunohistochemical staining. The results showed that the expression levels of KLF4 in the ADR group were higher than in the saline control group, whereas the levels of KLF4 in the ADR plus simvastatin group were almost similar to those of the saline control group (Figure 7D). These results indicated that ADR promotes the expression of KLF4, which can be reversed by simvastatin. Moreover, immunofluorescence results also showed that ADR treatment enhanced the expression of both KLF4 and CD133; however, simvastatin could clearly block the ADR-mediated activation of KLF4 and CD133 (Figure 7E). Thus, we concluded that ADR appears to promote a stem-like phenotype through activation of KLF4 signaling in osteosarcoma cells, whereas simvastatin diminishes the ADR-enhanced tumor-initiating ability.

Discussion

Chemotherapy is a systemic treatment involving the use of chemical agents to stop the growth of cancer cells. Although chemotherapy effectively eliminates cancer cells, its opposite effects that enhance the malignancy of the treated cancers have also been reported (Bertolini et al., 2009, Liu et al., 2013). ADR-based combination chemotherapy is the standard first-line treatment for advanced osteosarcoma. Despite the relevance of first-line chemotherapy, osteosarcoma recurs in most cases. The clinical benefits of therapy have reached a plateau, and local recurrence is still a major problem (Botter et al., 2014). CSCs exhibit enhanced chemo-/radiotherapy resistance, and their survival following cancer treatment is believed to be responsible for tumor recurrence and metastasis (Dela Cruz, 2013). Thus, understanding the impact of chemotherapy on cancer stemness and its underlying mechanisms is essential for identification of new therapeutic strategies to prevent tumor relapse. Here, we provide direct evidence that the first-line chemotherapy drug ADR can enhance stemness, metastasis traits, and cross-drug resistance to paclitaxel (Figure S4) in osteosarcoma by upregulating KLF4 expression. Our in vitro and in vivo studies also suggest that simvastatin can effectively prevent ADR-induced stemness by downregulating KLF4 expression.

Accumulating evidence has shown that CSCs may not only originate from transformation of normal stem cells but also may arise from dedifferentiation of cancer cells. An increasing body of evidence indicates that dedifferentiation of cancer cells can be induced by different environmental cues (inflammation, hypoxia, and serum deprivation) through epigenetic or genetic regulation. For example, TGF-β1 could promote non-osteosarcoma stem cell dedifferentiation into a subpopulation with stem cell characteristics (Zhang et al., 2013). In our study, we showed that treatment with ADR elevated the number of CD133+ cells in the osteosarcoma cell lines and primary osteosarcoma cells. This induction effect could not have resulted from eliminating CD133- cells, which are more sensitive to ADR, and preserving the CD133+ cells that were present before treatment because a limited number of cells were killed by the low dose of ADR (approximately the IC20) used for each cell line during treatment. These results indicated that ADR might induce dedifferentiation of osteosarcoma cells.

Specific transcriptional networks play an essential role in sustaining the growth and self-renewal of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and neoplastic stem-like cells. Expression of a defined and limited set of transcription factors (i.e., SOX2, OCT3/4, NANOG, KLF4, C-MYC, and BMI1) can reprogram mouse and human somatic cells to induce pluripotent stem cells (Moon et al., 2011, Schwitalla et al., 2013, Wang et al., 2013). These reprogramming transcription factors are frequently overexpressed in human cancers, and their expression levels are often correlated with tumor progression and poor prognosis (Abdouh et al., 2009, Frank et al., 2010). Our present study found that ADR treatment could selectively elevate KLF4 expression. In contrast, knockdown of KLF4 inhibited ADR-induced osteosarcoma stemness and metastasis. Previous research has confirmed that KLF4, a zinc-finger transcriptional regulator, can maintain the pluripotent and undifferentiated state of human ESCs (Chan et al., 2009, Zhang et al., 2010). Furthermore, our microarray experiment results showed that expression of stemness and metastasis-related genes, such as RAC1, CD24, ID2, DNER, HHAT, FBN1, CXCR4, and Slug, were significantly increased. Thus, we speculated that these genes might be downstream of KLF4 to regulate ADR-induced cancer stemness. ADR is well known as an inhibitor of topoisomerase II and induces single- and double-strand breaks in DNA. Although the mechanism of how ADR-induced DNA damage affects the KLF4 expression is unclear, there is evidence showing that KLF4 is required for p53-mediated induction of p21 in response to DNA damage, suggesting that ADR-induced upregulation of KLF4 might be correlated with DNA damage (Rowland and Peeper, 2006). Therefore, further studies are needed to explore the mechanism of KLF4 in regulating ADR-induced cancer stemness.

3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors, better known as statins, are the drugs most widely used to reduce serum cholesterol and decrease the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. In the past, research on statins has focused on their anti-cancer effect through inhibition of cell proliferation, induction of apoptosis, or inhibition of angiogenesis (Gauthaman et al., 2009a). In addition, a number of studies have found that use of these drugs could significantly suppress the development of various cancers including liver (Singh et al., 2013), breast (Ahern et al., 2014), gastric (Singh and Singh, 2013), and colorectal cancer, while diminishing cancer-related mortality (Nielsen et al., 2012, Zhong et al., 2015). These findings imply that statins may affect cancer stemness, which could explain its utility for cancer prevention. Our studies revealed that statins such as simvastatin could antagonize ADR-induced osteosarcoma stemness due to downregulation of KLF4 protein levels, but it is unclear how statins target KLF4 protein. We found that simvastatin has a little influence on the mRNA expression levels of KLF4 (data not shown); therefore, further studies are needed to determine whether statins could affect the protein stability or other protein synthesis process of KLF4. In addition, a few studies have reported that statins can reduce cancer stemness through regulation of RHOA/P27kip1 signaling or bone morphogenetic protein signaling (Ginestier et al., 2012, Kodach et al., 2011). Besides, it is also reported that statins could inhibit the growth of variant human ESCs as well as downregulate pluripotency-related genes including Growth differentiation factor-3, NANOG, and OCT-4 (Gauthaman et al., 2009b). Accordingly, these studies designating the role of these factors should be considered in future studies.

In conclusion, we provided evidence showing that ADR promotes a stem-like phenotype through activation of KLF4 signaling in osteosarcoma cells and that statins can inhibit the expression of KLF4 and reverse ADR-driven stemness and metastasis. Therefore, our data not only provide a possible mechanism of tumor recurrence in ADR-treated patients with osteosarcoma, but also help to promote the development of anti-CSC therapeutic targets and to optimize a therapeutic strategy to eradicate osteosarcoma.

Experimental Procedures

Drugs and Reagents

Simvastatin (Simva), atorvastatin (Atorva), and paclitaxel (Taxol) were from Selleck Chemicals. Human recombinant epidermal growth factor (rhEGF) and human recombinant basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF basic) were purchased from Peprotech. Adriamycin and DAPI were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Primary antibodies to KLF4 (catalog #sc-20691) and GAPDH (#sc-25778) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Cell Culture

U2OS cells were obtained from the Cell Bank of the China Science Academy, Shanghai and were cultured in RPMI-1640 (HyClone) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco Laboratories). KHOS/NP cells were maintained in DMEM (Gibco) containing 10% FBS. Primary osteosarcoma cells (MDOS-20) were established from tumor lesions taken from surgical biopsies and grown in DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with FBS as previously described (Zhang et al., 2014). Primary cells of passage numbers between 3 and 20 were used in the experiments. In addition, 293FT cells were grown in conditioned medium composed of DMEM, 10% FBS, 1 mM L-glutamine (Gibco), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 1% minimum essential medium-nonessential amino acids (Gibco).

Cell Transfection, Lentivirus Packaging, and Cell Transduction

The pCCL-c-MNDU3c-X2-PGK enhanced GFP plasmid was kindly provided by Dr. D.B. Kohn (Children's Hospital Los Angeles/University of Southern California). The pCCL-KLF4 plasmid was constructed according to the pMXs-hKLF4 Retroviral Vector (Cell Biolabs). Using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), vesicular stomatitis virus-pseudotyped vectors were produced by cotransient transfection of 293FT cells with expression constructs (pCCL-KLF4 or empty pCCL vectors), pRD8.9 packaging plasmids, and pMD.G envelope plasmids at a ratio of 5:5:1. Sodium pyruvate induction was performed by following the manufacturer's instructions. After 48 hr of transfection, supernatants were harvested, centrifuged, and filtered with a 0.4-μm filter. For stable transfection, osteosarcoma cells were grown in 6-well plates at 60%–70% confluence and then transduced with 1 mL of lentiviral vector particles (MOI = 10:1) in the presence of 6 μg/mL polybrene for 24 hr. The following day, the medium was removed and replaced with fresh culture medium. Positive transductants were selected with puromycin and examined after 2–3 days by determining the percentage of cells expressing the GFP reporter gene with flow cytometry and the expression of KLF4 with western blotting.

Western Blotting Analysis

Proteins in the lysates were equalized and then analyzed by western blotting using specific antibodies as described previously (Cao et al., 2015). The antibody against KLF4 (sc-20691) can recognize isoform 1 and isoform 2 of KLF4 protein.

Real-Time qPCR

Total RNA isolation and reverse transcription were conducted using a method described previously (Cao et al., 2015). The primers used are listed in Table S2. The results were normalized to those of the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

Flow Cytometry

After drug treatment for 24 hr, cells were harvested by trypsin treatment and suspensions were prepared shortly before analysis. For flow-cytometry analysis, cells (1 × 105 cells/100 μL buffer, 5% FBS in PBS) were placed on ice for 30 min and then incubated with a pure anti-CD133 (AC133) antibody (catalog #130-105-225, Miltenyi Biotec) for 45 min. Mouse isotype control immunoglobulin G antibody (#130-104-580, Miltenyi Biotec) was used as negative control for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) gating. After being washed, the cells were incubated with an Alexa 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for 30 min and washed again before analysis using a BD FACScaliber flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The fluorescence intensity was analyzed with Cell Quest Software (BD Biosciences).

Sphere-Formation Assay

The number of live osteosarcoma cells was determined using trypan blue staining, and single-cell suspensions were seeded in ultra-low attachment 6-well plates (Corning) at different densities per well (KHOS/NP, 1 × 105 cells; U2OS, 2 × 105 cells; MDOS-20, 2 × 105 cells). Serum-free DMEM/F12 (Life Technologies) supplemented with 20 ng/mL rhEGF, 20 ng/mL FGF basic, N2 (1:100; Life Technologies), and 500 units/mL penicillin-streptomycin was used as the culture medium. KHOS/NP, U2OS, and MDOS-20 cells were treated with 50, 100, and 100 nM ADR, respectively, for 7 days. Osteosphere cultures were photographed using a phase-contrast microscope (Olympus), and osteospheres ≥50 μm in diameter were counted.

Cell Transfection

The siRNA duplexes were synthesized by Genepharma. The sequences of the siRNAs used were as follows: KLF4-1#, 5′-UGA GAU GGG AAC UCU UUG UGU AGG U-3′; and KLF4-2#, 5′-AUC GUU GAA CUC CUC GGU CUC UCU C-3′. The transfection was performed using Oligofectamine reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

cDNA Microarray

The RNA samples were hybridized using a GeneChip PrimeView Human Gene Expression Array from Gene Tech. After scanning, the hybridization signals were collected for further analysis.

3,3′-Diaminobenzidine Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were dewaxed, rehydrated, and subjected to antigen retrieval for 30 min at 95°C. Tissues were exposed to a 1:50 dilution of anti-KLF4 antibody overnight at 4°C. A Histostain-Plus Kit was then used following the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunofluorescence

Cryostat sections were fixed and permeabilized. KLF4 and CD133 antibodies were used, followed by Alexa Fluor 488 or 594. Nuclei were visualized by staining with DAPI.

Migration Assay

For the scratch assay, osteosarcoma cells were grown to near confluence in a 24-well plate. Artificial wounds were created by disrupting cell monolayers with a sterile pipette tip. Cellular debris was aspirated and conditioned medium (with or without treatment with the indicated drugs) was added to the wells. Images of cell migration into the artificial wound were taken 0 and 12 hr after wounding.

For the Transwell chamber tests, osteosarcoma cells (2 × 104) were resuspended in culture medium and placed onto an uncoated membrane in the upper chamber (24-well insert, 8 μm, Corning Costar). DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS was used as an attractant in the lower chamber. After being incubated for 24 hr, the cells that migrated through the membrane were stained with 1% crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich).

Xenotransplantation

BALB/c (nu/nu) mice (National Rodent Laboratory Animal Resource, Shanghai), 4–5 weeks of age, were used for all experiments. The Animal Research Committee at Zhejiang University approved all animal studies, and animal care was provided in accordance with institutional guidelines. For tumorigenicity assays, serial dilutions of KHOS/NP cells were subcutaneously injected into nude mice. The mice were divided into four groups: treatment with ADR alone, simvastatin alone, ADR plus simvastatin, and no treatment. Treatment was initiated at the same time as cell implantation. Mice without identified tumors were monitored for 6 months after injection of cells and euthanized at the indicated times.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD, and the significance of differences between the values of the groups was determined with Student's t test. Differences were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05.

Author Contributions

M.Y. and Q.H. conceived the project. Y.L. and M.X. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. M.X. performed statistical analysis. B.Y. and Q.H. provided financial support. Y.L. and M.Y. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. D.B. Kohn for providing lentivirus pR Δ8.9 and pMD.G plasmids. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81473227), the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (No. 81625024), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Published: May 25, 2017

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes four figures and two tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.04.025.

Contributor Information

Meidan Ying, Email: mying@zju.edu.cn.

Qiaojun He, Email: qiaojunhe@zju.edu.cn.

Accession Numbers

The entire microarray dataset is available at the GEO database under accession number GEO: GSE96892.

Supplemental Information

References

- Abdouh M., Facchino S., Chatoo W., Balasingam V., Ferreira J., Bernier G. BMI1 sustains human glioblastoma multiforme stem cell renewal. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:8884–8896. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0968-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari A.S., Agarwal N., Wood B.M., Porretta C., Ruiz B., Pochampally R.R., Iwakuma T. CD117 and Stro-1 identify osteosarcoma tumor-initiating cells associated with metastasis and drug resistance. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4602–4612. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern T.P., Lash T.L., Damkier P., Christiansen P.M., Cronin-Fenton D.P. Statins and breast cancer prognosis: evidence and opportunities. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e461–e468. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70119-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu-Roy U., Basilico C., Mansukhani A. Perspectives on cancer stem cells in osteosarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2013;338:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini G., Roz L., Perego P., Tortoreto M., Fontanella E., Gatti L., Pratesi G., Fabbri A., Andriani F., Tinelli S. Highly tumorigenic lung cancer CD133+ cells display stem-like features and are spared by cisplatin treatment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:16281–16286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905653106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botter S.M., Neri D., Fuchs B. Recent advances in osteosarcoma. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2014;16:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J., Wang Y., Dong R., Lin G., Zhang N., Wang J., Lin N., Gu Y., Ding L., Ying M. Hypoxia-induced WSB1 promotes the metastatic potential of osteosarcoma cells. Cancer Res. 2015;75:4839–4851. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K.K., Zhang J., Chia N.Y., Chan Y.S., Sim H.S., Tan K.S., Oh S.K., Ng H.H., Choo A.B. KLF4 and PBX1 directly regulate NANOG expression in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2114–2125. doi: 10.1002/stem.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Li Y., Yu T.S., McKay R.M., Burns D.K., Kernie S.G., Parada L.F. A restricted cell population propagates glioblastoma growth after chemotherapy. Nature. 2012;488:522–526. doi: 10.1038/nature11287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou A.J., Gorlick R. Chemotherapy resistance in osteosarcoma: current challenges and future directions. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2006;6:1075–1085. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.7.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dela Cruz F.S. Cancer stem cells in pediatric sarcomas. Front Oncol. 2013;3:168. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fiore R., Santulli A., Ferrante R.D., Giuliano M., De Blasio A., Messina C., Pirozzi G., Tirino V., Tesoriere G., Vento R. Identification and expansion of human osteosarcoma-cancer-stem cells by long-term 3-aminobenzamide treatment. J. Cell Physiol. 2009;219:301–313. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong H., Hohenstein K.A., Donovan P.J. Regulation of self-renewal and pluripotency by Sox2 in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1931–1938. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank N.Y., Schatton T., Frank M.H. The therapeutic promise of the cancer stem cell concept. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:41–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI41004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann-Morvinski D., Verma I.M. Dedifferentiation and reprogramming: origins of cancer stem cells. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:244–253. doi: 10.1002/embr.201338254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H., Honoki K., Tsujiuchi T., Kido A., Yoshitani K., Takakura Y. Sphere-forming stem-like cell populations with drug resistance in human sarcoma cell lines. Int. J. Oncol. 2009;34:1381–1386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthaman K., Fong C.Y., Bongso A. Statins, stem cells, and cancer. J. Cell. Biochem. 2009;106:975–983. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthaman K., Manasi N., Bongso A. Statins inhibit the growth of variant human embryonic stem cells and cancer cells in vitro but not normal human embryonic stem cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009;157:962–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00241.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginestier C., Monville F., Wicinski J., Cabaud O., Cervera N., Josselin E., Finetti P., Guille A., Larderet G., Viens P. Mevalonate metabolism regulates Basal breast cancer stem cells and is a potential therapeutic target. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1327–1337. doi: 10.1002/stem.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honoki K., Fujii H., Kubo A., Kido A., Mori T., Tanaka Y., Tsujiuchi T. Possible involvement of stem-like populations with elevated ALDH1 in sarcomas for chemotherapeutic drug resistance. Oncol. Rep. 2010;24:501–505. doi: 10.3892/or_00000885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim E.E., Babaei-Jadidi R., Saadeddin A., Spencer-Dene B., Hossaini S., Abuzinadah M., Li N.N., Fadhil W., Ilyas M., Bonnet D. Embryonic NANOG activity defines colorectal cancer stem cells and modulates through AP1-and TCF-dependent mechanisms. Stem Cells. 2012;30:2076–2087. doi: 10.1002/stem.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansara M., Teng M.W., Smyth M.J., Thomas D.M. Translational biology of osteosarcoma. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2014;14:722–735. doi: 10.1038/nrc3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodach L.L., Jacobs R.J., Voorneveld P.W., Wildenberg M.E., Verspaget H.W., van Wezel T., Morreau H., Hommes D.W., Peppelenbosch M.P., van den Brink G.R. Statins augment the chemosensitivity of colorectal cancer cells inducing epigenetic reprogramming and reducing colorectal cancer cell 'stemness' via the bone morphogenetic protein pathway. Gut. 2011;60:1544–1553. doi: 10.1136/gut.2011.237495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leis O., Eguiara A., Lopez-Arribillaga E., Alberdi M.J., Hernandez-Garcia S., Elorriaga K., Pandiella A., Rezola R., Martin A.G. Sox2 expression in breast tumours and activation in breast cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 2012;31:1354–1365. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levings P.P., McGarry S.V., Currie T.P., Nickerson D.M., McClellan S., Ghivizzani S.C., Steindler D.A., Gibbs C.P. Expression of an exogenous human Oct-4 promoter identifies tumor-initiating cells in osteosarcoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5648–5655. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Tiede B., Massague J., Kang Y. Beyond tumorigenesis: cancer stem cells in metastasis. Cell Res. 2007;17:3–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Ma W., Jha R.K., Gurung K. Cancer stem cells in osteosarcoma: recent progress and perspective. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:1142–1150. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2011.584553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.P., Yang C.J., Huang M.S., Yeh C.T., Wu A.T., Lee Y.C., Lai T.C., Lee C.H., Hsiao Y.W., Lu J. Cisplatin selects for multidrug-resistant CD133+ cells in lung adenocarcinoma by activating Notch signaling. Cancer Res. 2013;73:406–416. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh Y.H., Wu Q., Chew J.L., Vega V.B., Zhang W.W., Chen X., Bourque G., George J., Leong B., Liu J. The Oct4 and Nanog transcription network regulates pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:431–440. doi: 10.1038/ng1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonardo E., Frias-Aldeguer J., Hermann P.C., Heeschen C. Pancreatic stellate cells form a niche for cancer stem cells and promote their self-renewal and invasiveness. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:1282–1290. doi: 10.4161/cc.19679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins-Neves S.R., Paiva-Oliveira D.I., Wijers-Koster P.M., Abrunhosa A.J., Fontes-Ribeiro C., Bovee J.V., Cleton-Jansen A.M., Gomes C.M. Chemotherapy induces stemness in osteosarcoma cells through activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Cancer Lett. 2016;370:286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon J.H., Heo J.S., Kim J.S., Jun E.K., Lee J.H., Kim A., Kim J., Whang K.Y., Kang Y.K., Yeo S. Reprogramming fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells with Bmi1. Cell Res. 2011;21:1305–1315. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair R., Roden D.L., Teo W.S., McFarland A., Junankar S., Ye S., Nguyen A., Yang J., Nikolic I., Hui M. c-Myc and Her2 cooperate to drive a stem-like phenotype with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2014;33:3992–4002. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S.F., Nordestgaard B.G., Bojesen S.E. Statin use and reduced cancer-related mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1792–1802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo S., Hersey J.M., Mellor P., Dai W., Santos-Silva A., Liber D., Luk L., Titley I., Carden C.P., Box G. Ovarian cancer stem cell-like side populations are enriched following chemotherapy and overexpress EZH2. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2011;10:325–335. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland B.D., Peeper D.S. KLF4, p21 and context-dependent opposing forces in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:11–23. doi: 10.1038/nrc1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwitalla S., Fingerle A.A., Cammareri P., Nebelsiek T., Goktuna S.I., Ziegler P.K., Canli O., Heijmans J., Huels D.J., Moreaux G. Intestinal tumorigenesis initiated by dedifferentiation and acquisition of stem-cell-like properties. Cell. 2013;152:25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P.P., Singh S. Statins are associated with reduced risk of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2013;24:1721–1730. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Singh P.P., Singh A.G., Murad M.H., Sanchez W. Statins are associated with a reduced risk of hepatocellular cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:323–332. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K., Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirino V., Desiderio V., Paino F., De Rosa A., Papaccio F., Fazioli F., Pirozzi G., Papaccio G. Human primary bone sarcomas contain CD133+ cancer stem cells displaying high tumorigenicity in vivo. FASEB J. 2011;25:2022–2030. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-179036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Park P., Zhang H., La Marca F., Lin C.Y. Prospective identification of tumorigenic osteosarcoma cancer stem cells in OS99-1 cells based on high aldehyde dehydrogenase activity. Int. J. Cancer. 2011;128:294–303. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.L., Chiou S.H., Wu C.W. Targeting cancer stem cells: emerging role of Nanog transcription factor. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:1207–1220. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S38114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying M., Liu G., Shimada H., Ding W., May W.A., He Q., Adams G.B., Wu L. Human osteosarcoma CD49f(-)CD133(+) cells: impaired in osteogenic fate while gain of tumorigenicity. Oncogene. 2013;32:4252–4263. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F., Li J., Chen H., Fu J., Ray S., Huang S., Zheng H., Ai W. Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) is required for maintenance of breast cancer stem cells and for cell migration and invasion. Oncogene. 2011;30:2161–2172. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P., Andrianakos R., Yang Y., Liu C., Lu W. Kruppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) prevents embryonic stem (ES) cell differentiation by regulating Nanog gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:9180–9189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.077958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.X., Wu H.T., Zheng J.H., Yu P., Xu L.X., Jiang P., Gao J., Wang H., Zhang Y. Transforming growth factor beta 1 signal is crucial for dedifferentiation of cancer cells to cancer stem cells in osteosarcoma. Stem Cells. 2013;31:433–446. doi: 10.1002/stem.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Zhou Q., Zhang N., Li W., Ying M., Ding W., Yang B., He Q. E2F1 impairs all-trans retinoic acid-induced osteogenic differentiation of osteosarcoma via promoting ubiquitination-mediated degradation of RARalpha. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:1277–1287. doi: 10.4161/cc.28190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S., Zhang X., Chen L., Ma T., Tang J., Zhao J. Statin use and mortality in cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41:554–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.