Abstract

Background

The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in childhood and adolescence is 5–11 cases per 100 000 persons per year, corresponding to a new diagnosis of IBD in 800–1470 patients in Germany each year.

Methods

This review is based on pertinent publications retrieved by a selective search in PubMed, including guidelines from Germany and abroad.

Results

Children and adolescents with IBD often have extensive involvement and an aggressive course of disease. Nonetheless, infliximab and adalimumab are the only biological agents that have been approved for this group of patients. In Crohn’s disease, exclusive enteral nutrition is the treatment of first choice for inducing a remission. Patients with (peri-)anal fistulae are treated primarily with infliximab. Corticosteroids and aminosalicylates should be used with caution. In contrast, children and adolescents with ulcerative colitis are treated with either aminosalicylates or prednisolone to induce a remission. As a rule, maintenance pharmacotherapy with thiopurines in Crohn’s disease and severe ulcerative colitis, or with aminosalicylates in mild to moderate ulcerative colitis, is indicated for several years, at least until the end of puberty. Patients with refractory disease courses are treated with methylprednisolone, anti-TNF-a-antibodies, and/or calcineurin inhibitors. The spectrum of surgical interventions is the same as for adults. Specific aspects of the treatment of children and adolescents with IBD include adverse drug effects, the areas of nutrition, growth, and development, and the structured transition to adult medicine.

Conclusion

Children and adolescents with IBD or suspected IBD should be cared for by pediatric gastroenterologists in a center where such care is provided. Individualized treatment with multidisciplinary, family-oriented long-term care is particularly important. Drug trials in children and adolescents are needed so that the off-label use of drugs to patients in this age group can be reduced.

The incidence of Crohn’s disease in Germany is up to 6.6 per 100 000 population. Its prevalence is approximately 100 to 200 per 100 000 population (1). For ulcerative colitis, the incidence in Germany is 3.0 to 3.9 per 100 000 population, and its prevalence approximately 160 to 250 per 100 000 population (2). Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is diagnosed before the age of 18 years in approximately 25% of all patients; approximately one-quarter of all affected children and adolescents are under the age of 10 years at diagnosis (3). Children and adolescents with IBD are more likely to have more severe intestinal involvement at diagnosis and faster disease progression than adults (4). Treatment recommendations for children and adolescents are different than those for adults (5– 13, e1). The treatment of children and adolescents with suspected or confirmed IBD should comply with these recommendations and be performed by pediatric gastroenterologists (1, 2). Multidisciplinary treatment of children and adolescents with IBD is complex, especially because it requires the availability of numerous subdisciplines (e2). Data on children and adolescents with IBD in Germany is recorded in the CEDATA-GPGE registry of the German-speaking Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition (GPGE, Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Gastroenterologie und Ernährung) (14, 15). This paper addresses the increasingly important subject of medical care for children and adolescents with IBD in the context of aspects specific to ages at which development is ongoing.

Methods

This article is based on a selective search of the literature in PubMed. Both German (1, 2) and European (11– 13) guidelines for both the above-mentioned diseases are available and were consulted. For the diagnosis of IBD, the available data is mostly limited to case series, but treatment recommendations are usually based on controlled trials or meta-analyses of controlled trials.

Diagnosis

As with adults, IBD is suspected in children and adolescents when initial diagnostic examination reveals a combination of symptoms and abnormal laboratory findings (including fecal inflammatory markers). It is diagnosed if there are abnormal findings in clinical history and on physical examination using endoscopy and radiology, including histopathological evaluation of stepwise biopsies from the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract (16).

Symptoms

Although the clinical presentation of IBD in children and adolescents can be similar to that found in adults, some of the disease phenotype is substantially different. This can be caused by, for example, specific complications, sometimes age-specific, such as growth retardation or delayed puberty (table). For Crohn’s disease in particular, variability between individuals is particularly great in childhood and adolescence. It is not uncommon for symptom onset to be very hard to notice. Because symptoms differ in degree of severity and intensity, in individual cases they can be confused with nonspecific or functional complaints (17, 18). The most common extraintestinal manifestation of IBD in children and adolescents is impaired growth/growth retardation; this is particularly true of Crohn’s disease, in which impaired growth/growth retardation occurs in 10 to 30% of cases. Approximately 10% of children and adolescents have other extraintestinal manifestations of IBD at diagnosis; these can also occur in adults (19) (table).

Table. Inflammatory bowel disease symptoms and differential diagnoses in childhood and adolescence.

| Symptoms | Extraintestinal manifestations | Differential diagnoses |

|

|

|

Clinical history and physical examination

Children and adolescents with IBD are more likely than adults to have a positive family history of IBD. This indicates that genetic factors play a greater role in IBD when initial manifestation occurs during childhood or adolescence (20, e3). Intestinal inflammation in infants and young children can be caused by a number of genetic defects that can lead to involvement of the immune system and the intestinal epithelium (this is known as monogenic IBD). Approximately 1% of children and adolescents with IBD are less than 1 year old; around 15% are younger than 6 years (21). Full physical examination must include oral and perianal inspection (rectal examination if necessary) and evaluation of height and weight using age- and sex-specific percentile curves and pubertal development (Tanner stages). A height z-score of less than –2.5 indicates significant impaired growth/growth retardation. Body mass index (BMI) and rate of growth (in centimeters per year) are also calculated, on the basis of anthropometric data. BMI below the 10th percentile and/or rate of growth less than 5 cm per year (in children older than 2 years) indicates significant impaired growth/growth retardation.

Laboratory diagnostics

As in adults, diagnosis of IBD requires blood and stool tests (1, 2, 16) (etable 1). Diagnostic procedures for celiac disease must be performed in children and adolescents with growth retardation and/or nonbloody diarrhea (22). In children with suspected IBD before the age of 2 years, primary immunodeficiency must also be ruled out (21). Disease onset before the age of 6 years is probably caused by a genetic, possibly monogenic, immunodeficiency with intestinal inflammation typical of IBD. The incidence of very early disease onset is approximately 4.37 per 100 000; its prevalence is 14 per 100 000 (21). The possibility of an underlying food allergy must also be considered (23, e4).

eTable 1. Blood and stool tests for suspected inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents.

| Blood tests | Stool tests | Additional tests |

|

|

|

Endoscopy and histopathology

If suspected IBD is confirmed on the basis of clinical history, physical examination, and laboratory findings, the patient requires treatment by an experienced pediatric gastroenterologist. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and ileocolonoscopy are usually performed under sedation (or general anesthesia). During endoscopy stepwise biopsies are taken from all sections of the gastrointestinal tract, including those which are endoscopically normal. These then undergo histopathological evaluation (e5– e7).

Imaging diagnostics

Involvement of the small intestine is assessed using either magnetic resonance (MR) enterography with oral contrast only (administered per os or via nasogastric tube) or video capsule endoscopy (16). MR enterography can be performed from the age of 3 or 4 years. In addition, high-resolution transabdominal Doppler ultrasound is highly suitable as a screening or monitoring examination in children. Conventional X-ray is used if ileus, subileus, or toxic megacolon is suspected, and to determine bone age (left hand). Computed tomography is used only in emergencies or where other diagnostic procedures have failed, due to the radiation burden it entails. MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is used in children and adolescents for certain specific issues (e.g. suspected liver/bile duct involvement).

Differential diagnoses

The main differential diagnoses for IBD in children and adolescents are summarized in the Table (17, 18, 22, 24, 25).

Classification

The Paris classification for inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents is closely based on the Montreal classification for IBD in adults. Among other issues, it stratifies risk before the beginning of treatment (16, 28, e8). Clinical indices are of proven value in assessing disease activity, particularly within studies. They were developed specifically for children and adolescents with Crohn’s disease (etable 2) and ulcerative colitis (etable 3) (8, 9, e1). However, because of the increasing importance of specific biomarkers (particularly fecal calprotectin), these indices require revision (e9, e10).

eTable 2. Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activitiy Index (PCDAI).

| Criterion | Characteristics | Score | |

| Clinical symptoms | |||

| Abdominal pain | • None • Mild, brief, does not interfere with activities • Moderate/severe, daily, longer lasting, affects activities, nocturnal |

0 5 10 |

|

| Stools | • 0–1 liquid stools, no blood • Up to 2 semi-formed with small blood or 2 to 5 liquid stools per day • Gross bleeding or ≥6 liquid stools or nocturnal diarrhea |

0 5 10 |

|

| General well-being | • Well, no limitation of activities • Below par, occasional difficulties in maintaining age appropriate activities • Very poor, frequent limitation of activities |

0 5 10 |

|

| Physical examination | |||

| Changes in body weight over 4 to 6 months | • Weight gain, desired stable weight, or voluntary weight loss • Involuntary stable weight or involuntary weight loss of 1 to 9% • Weight loss ≥10% |

0 5 10 |

|

| Height at diagnosis or Height velocity at follow-up |

• <1 channel decrease • ≥ 1, <2 channel decrease • >2 channel decrease or • Height velocity ≥ –1 standard deviation • Height velocity < –1 standard deviation but > –2 standard deviations • Height velocity ≤ –2 standard deviations |

0 5 10 0 5 10 |

|

| Abdomen | • Normal, no tenderness, no mass • Tenderness, or mass without tenderness • Tenderness, involuntary guarding, definite mass |

0 5 10 |

|

| Perineum | • None, asymptomatic tags • 1–2 indolent fistula, scant drainage, no tenderness of abscess • Active fistula, drainage, tenderness or abscess |

0 5 10 |

|

| Extra-intestinal manifestations:

Fever ≥38.5 °C for 3 days in previous week Arthritis Uveitis Erythema nodosum Pyoderma gangrenosum |

None 1 ≥2 |

0 5 10 |

|

| Laboratory findings | |||

| Hematocrit | ≤10 years | >33 28–32 <28 |

0 2.5 5 |

| Girls, 11–19 years | ≥ 34 29–33 <29 |

0 2.5 5 |

|

| Boys, 11–14 years | ≥ 35 30–34 <30 |

0 2.5 5 |

|

| Boys, 15–19 years | ≥ 37 32–36 <32 |

0 2.5 5 |

|

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (mm/hr.) | <20 20–50 50 |

0 2.5 5 |

|

| Albumin level (g/dL) | ≥ 3.5 3.1–3.4 ≤ 3.0 |

0 5 10 |

|

| Total score | |||

| ≤10 points 10–30 points 30–100 points |

Inactive (remission) Mild activity Moderate to severe activity |

…………………… | |

eTable 3. Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activitiy Index (PUCAI).

| Criterion | Characteristics | Score |

| Abdominal pain | • No pain • Pain can be ignored • Pain cannot be ignored |

0 5 10 |

| Rectal bleeding | • None • Small amount only, in less than 50% of stools • Small amounts with most stools • Large amounts (>50% of stool content) |

0 10 20 30 |

| Stool consistency of most stools | • Formed • Partly formed • Completely unformed |

0 5 10 |

| Number of stools per 24 hours | 0–2 3–5 6–8 8 |

0 5 10 15 |

| Nocturnal stools (any episode causing wakening) | • No • Yes |

0 10 |

| Activity level | • No limitation of activity • Occasional limitation of activity • Severely restricted activity |

0 5 10 |

| Total (0 to 85 points) | <10: remission 10 to 40: mild activity 40 to 65: moderate activity 65 to 85: high activity |

................ |

Treatment

Specific features of IBD in children and adolescents

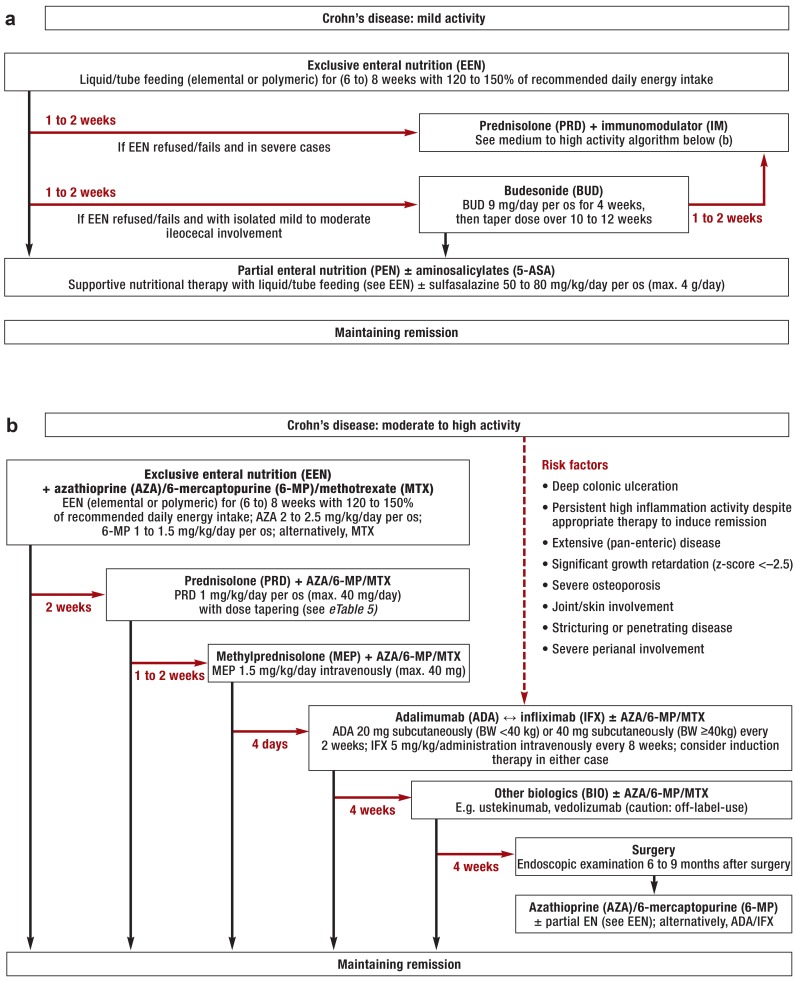

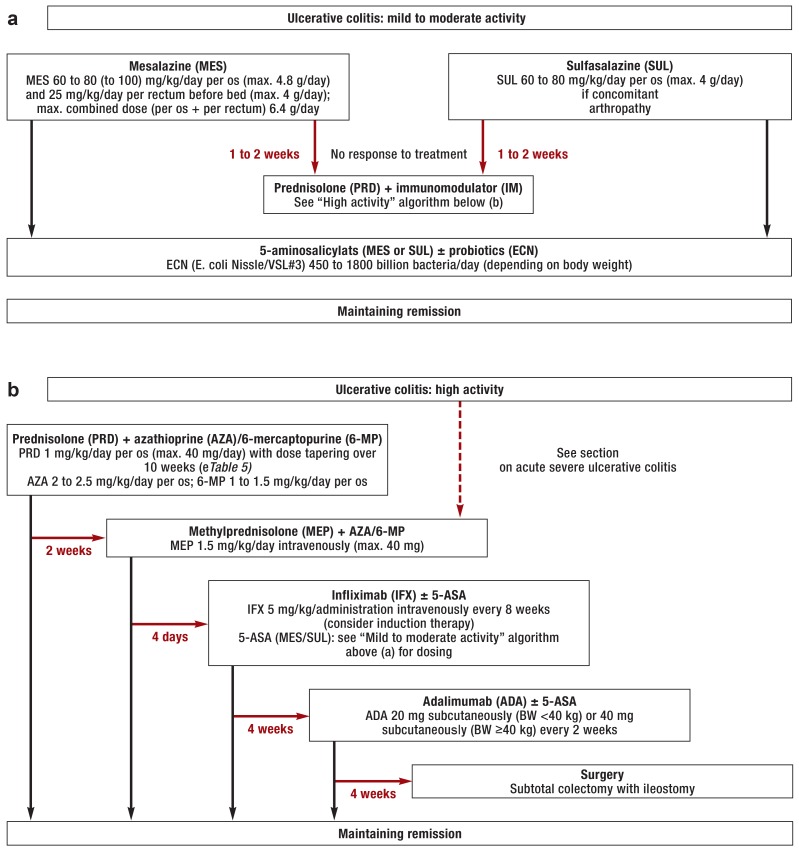

Treatment for IBD in patients under the age of 18 years differs from treatment recommendations for adults, sometimes substantially (1, 2, 27, 28). Two examples of this are intensiveness of treatment and drug authorization. eTable 4 details randomized clinical trials in children and adolescents with IBD (e11– e22). The main differences between treatment algorithms for children and adolescents and those for adults are shown in the eBox (11, 12, 27, e17, e23). Detailed written information on all aspects of IBD written specifically for children, adolescents, parents, schoolteachers, and kindergarten teachers is available, as are apps for smartphones and tablets and an IBD booklet specifically for children and adolescents. The treatment concept also includes seminars for physicians, patients, and parents and IBD training programs for children and adolescents. Children from the age of approximately 4 years must be either supervised when they take tablets or trained in doing so; alternatively, medication can be provided in alternative pharmaceutical forms. Treatment algorithms for children and adolescents with IBD are summarized in Figures 1 and 2.

eTable 4. Randomized clinical trials in children and adolescents with IBD.

| Trial | Intervention | Patient cohort | Trial design | Findings | Main ADRs |

| Griffiths A et al. 1993 (e16) |

5-ASA 50 mg/kg BW/day (max. 3 g/day) per os vs. placebo |

13 patients with active Crohn’s disease of the small intestine; age 5 to 18 years; trial period August 1988 to February 1991 |

Single-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover (2 × 8 weeks with 4-week washout phase); 20 weeks’ follow-up |

43% vs. 0% clinical response in week 8 (5-ASA vs. placebo; p = 0.130); clinical response vs. no clinical response in week 20 (5-ASA vs. placebo; p = 0.03) | Not observed |

| Levine A et al. 2003 (e22) |

Budesonide 9 mg/day per os vs. prednisone 40 mg/day per os |

33 patients with active, mild to moderate Crohn’s disease; age 8 to 18 years; trial period not stated |

Multicenter (n = 13), open-label; 12 weeks’ follow-up | 47% vs. 50% clinical remission in week 12 (budesonide vs. prednisone; not significant); 32% vs. 71% side effects (budesonide vs. prednisone; p <0.05) | 8% vs. 36% muscle involvement, 32% vs. 71% moon facies (budesonide vs. prednisone; p = 0.07 and p <0.05) |

| Escher JC et al. 2004 (e18) |

Budesonide 9 mg/day per os vs. prednisolone 1 mg/kg BW/day per os |

48 patients with active Crohn’s disease of the ileum and/or ascending colon; age 6 to 16 years; trial period April 1998 to December 2000 |

Multicenter (n = 36), double-blind; placebo-controlled; 12 weeks’ follow-up |

55% vs. 71% clinical remission in week 8 (budesonide vs. prednisolone; p = 0.25); higher morning plasma cortisol level (i.e. less adrenal suppression) in budesonide group (p = 0.003) | 50% vs. 80% glucocorticoid-associated ADRs (budesonide vs. prednisolone; p = 0.03); moon facies (23% vs. 60%; p = 0.01); acne (5% vs. 28%; p = 0.03) |

| Cezard JP et al. 2009 (e21) |

Mesalazine 50 mg/kg BW/day vs. placebo for 12 months | 122 patients with active Crohn’s disease; age <18 years; trial period 1991 to 1993 and 1996 to 1999 |

Multicenter (n = 17), double-blind, placebo-controlled; 12 months’ follow-up |

57% vs. 39% relapse after 12 months (mesalazine vs. placebo; not significant) | 1% vs. 3% adverse reactions (mesalazine vs. placebo) |

| Markowitz J et al. 2000 (e17) |

6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) 1.5 mg/kg BWday vs. placebo (plus prednisone 40 mg/day in both groups) |

55 patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease; age 12 to 18 years; trial period not stated |

Multicenter (n = 18), placebo-controlled, double-blind, 18 months’ follow-up |

89% clinical remission in week 48 in both groups; shorter concomitant prednisone medication in 6-MP group (p <0.001); lower cumulative prednisone dose in 6-mp group in weeks 24, 48, and 72 (p <0.01); 9% vs. 47% relapse (6-mp vs. placebo; p = 0.007) | Mild leukopenia (22%), elevated transaminases (15%) |

| Hyams J et al. 2012 (e13) |

Adalimumab 20 mg vs. 40 mg every 2 weeks subcutaneously (BW≥40 kg) or 10 mg vs. 20 mg every 2 weeks subcutaneously (BW<40 kg) |

192 patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease; age 6 to 17 years; trial period April 2007 to May 2010 |

Multicenter (n = 45), double-blind, open-label induction phase (4 weeks); 48 weeks’ follow-up | 28% vs. 39% clinical remission in week 26 (adalimumab 10/20 mg vs. 20/40 mg; p = 0.075) | Dose-independent: infections (55%), reaction at injection site (10%) |

| Hyams J et al. 2007 (e11) |

Infliximab 5 mg/kg BWevery 8 weeks vs. every 12 weeks intravenously | 112 patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease; age 6 to 17 years, trial period February 2003 to March 2004 |

Multicenter (n = 34) open-label, open-label induction phase (10 weeks); crossover (dose/interval modification); 54 weeks’ follow-up | 88% clinical response vs. 59% clinical remission in week 10; 64% vs. 33% clinical response in week 54 (infliximab every 8 vs. 12 weeks; p = 0.002); 56% vs. 24% clinical remission in week 54 (infliximab every 8 vs. 12 weeks; p <0.001) | Independent of interval: infections (56%), infusion reaction (18%) |

| Ruemmele FM et al. 2009 (e14) |

Infliximab 5 mg/kg BW every 8 weeks vs. on demand intravenously | 40 patients with acute-phase Crohn’s disease; age 7 to 17 years; trial period May 2002 to April 2005 |

Multicenter (n = 11), open-label, open-label induction phase (10 weeks); crossover (dose/interval modification); 60 weeks’ follow-up | 85% clinical remission in week 10; 83% vs. 61% clinical response in week 60 (infliximab every 8 weeks vs. on demand; p = 0.011); 23% vs. 92% relapse (infliximab every 8 weeks vs. on demand; p <0.003) | Independent of interval: infections (38%); headache, fever, skin reactions (8% each) |

| Hyams J et al. 2012 (e12) |

Infliximab 5 mg/kg BW every 8 weeks vs. every 12 weeks intravenously | 60 patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis; age 6 to 17 years; trial period August 2006 to June 2010 |

Multicenter (n = 23), open-label, open-label induction phase (10 weeks); 54 weeks’ follow-up | 73% clinical response in week 8; 38% vs. 18% clinical remission in week 54 (infliximab every 8 vs. 12 weeks; p = 0.146) | Independent of interval: infections (60%); infusion reaction (16%) |

| Quiros JA et al. 2009 (e15) |

5-ASA 2.25 g vs. 6.75 g/day per os | 68 patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis; age 5 to 17 years; trial period August 2004 to March 2006 |

Multicenter (n = 23), double-blind, 8 weeks’ follow-up | 37% vs. 45% clinical response, 9% vs. 12% clinical remission in week 8 (5-ASA 2.25 g vs. 6.75 g/day; not significant) | Dose-independent: headache (15%), abdominal pain (25%) |

| Romano C et al. 2010 (e19) |

Betamethasone dipropionate (BDP) 5 mg/day per os for 8 weeks followed by 5-ASA 80 mg/kg BW/day per os for 4 weeks vs. 5-ASA 80 mg/kg BW/day per os for 12 weeks |

30 patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis (pancolitis or left-sided colitis); age <18 years; trial period not stated |

Single-center, open-label; 12 months’ follow-up | 80% vs. 33% clinical remission in week 4 (BDP vs. 5-ASA; p <0.025); better clinical response in bdp group in weeks 8 (p <0.003) and 12 (p <0.015); 73% vs. 27% endoscopic remission in week 12 (bdp vs. 5-asa; p <0.025) | No significant adverse reactions reported |

| Ferry GD et al. 1993 (e20) |

Olsalazine 30 mg/kg BW/day (max. 2 g/day) per os vs. Sulfasalazine 60 mg/kg BW/day (max. 4 g/day) |

56 patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis; aged 2 to 17 years; trial period June 1987 to July 1989 |

Multicenter (n = 13); double-blind; 12 weeks’ follow-up | 39% vs. vs. 79% clinical remission in week 12 (olsalazine vs. sulfasalazine; p = 0.006); 36% vs. 4% failure to respond to treatment (olsalazine vs. sulfasalazine; p = 0.005) | 39% vs. 46% adverse reactions (olsalazine vs. sulfasalazine): headache, nausea, vomiting, rash, itching, diarrhea, and/or fever |

5-ASA: 5-aminosalicylates; BW: Body weight; ADR: Adverse drug reaction

Figure 1.

Treatment algorithms for children and adolescents with Crohn’s disease: a) mild activity; b) moderate to high activity

Black arrows: clinical response to treatment; red arrows: no response to treatment within the stated time period or treatment refused; ±: administer if required; ↔:equally valid treatment options; BW: body weight.

The procedure outlined here is closely based on the consensus recommendations of international specialized societies (ECCO, ESPGHAN) (11).

Preparation for immunosuppressant therapy

Patients’ vaccination status and infectious disease history should be ascertained before beginning treatment. If a patient is not sufficiently protected by prior vaccinations, the necessary vaccinations—in line with the patient’s age and with current vaccination recommendations—should be administered before immunosuppressant treatment is begun. This is particularly important for live vaccines, as these are usually contraindicated later, i.e. during immunosuppressant treatment (e24, e25). Inactivated vaccines can and should be used even in immunosuppressed children and adolescents (ideally, for optimal efficacy, at least 2 weeks before the beginning of immunosuppressant treatment or during stable disease phases). In addition, latent tuberculosis must be ruled out using clinical history, chest X-ray, and a tuberculosis blood test (ɣ-interferon assay) before immunosuppressant treatment is begun (particularly before anti-TNF-a antibody therapy). The genotype (or activity) of thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) should be determined before thiopurine therapy is administered; this is because hereditary low or absent TPMT activity entails an increased risk of severe thiopurine-induced bone marrow toxicity (11, 29, e26).

Inducing remission

First-line treatment to induce remission in children and adolescents with Crohn’s disease, regardless of severity, is exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN) via liquid or tube feeding (11, 30– 32). Exceptions to this are children and adolescents who present risk factors (particularly anal fistulae): for this group, primary treatment is infliximab therapy (11). Formula feeding can be administered orally, via a nasogastric tube, or via a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube as part of EEN. Regarding PEGs, caution is required in cases of isolated involvement of the upper gastrointestinal tract proximal to the Treitz ligament (e27). If therapy has had no effect after 1 to 2 weeks or if treatment is refused by the patient or the patient’s family, glucocorticoid treatment is administered instead. TNF-a blockers (adalimumab, infliximab) are authorized for the treatment of Crohn’s disease in patients over the age of 6 years. If any risk factors are present, TNF-a blockers should be used as initial remission induction therapy (11). Prognostic risk factors for severe disease progression in children and adolescents with Crohn’s disease are listed in Figure 1b (11). In children and adolescents with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis, remission is induced using 5-aminosalicylates; corticosteroids are used if disease activity is high or the disease is severe (12). Long-term and/or frequent use of corticosteroids in children and adolescents is no longer current practice, among other reasons because of their severe side effects for growth and physical development (11). eTable 5 states the recommendations for tapering prednisone or prednisolone dosing (11, 13).

eTable 5. Recommended dosing and tapering schedule for prednisone or prednisolone.

|

Week 1 |

Week 2 |

Week 3 |

Week 4 |

Week 5 |

Week 6 |

Week 7 |

Week 8 |

Week 9 |

Week 10 |

Week 11 |

| 60 mg | 50 mg | 40 mg | 35 mg | 30 mg | 25 mg | 20 mg | 15 mg | 10 mg | 5 mg | 0 mg |

| 50 mg | 40 mg | 40 mg | 35 mg | 30 mg | 25 mg | 20 mg | 15 mg | 10 mg | 5 mg | 0 mg |

| 45 mg | 40 mg | 40 mg | 35 mg | 30 mg | 25 mg | 20 mg | 15 mg | 10 mg | 5 mg | 0 mg |

| 40 mg | 40 mg | 30 mg | 30 mg | 25 mg | 25 mg | 20 mg | 15 mg | 10 mg | 5 mg | 0 mg |

| 35 mg | 35 mg | 30 mg | 30 mg | 25 mg | 20 mg | 15 mg | 15 mg | 10 mg | 5 mg | 0 mg |

| 30 mg | 30 mg | 30 mg | 25 mg | 20 mg | 15 mg | 15 mg | 10 mg | 10 mg | 5 mg | 0 mg |

| 25 mg | 25 mg | 25 mg | 20 mg | 20 mg | 15 mg | 15 mg | 10 mg | 5 mg | 5 mg | 0 mg |

| 20 mg | 20 mg | 20 mg | 15 mg | 15 mg | 12.5 mg | 10 mg | 7.5 mg | 5 mg | 2.5 mg | 0 mg |

| 15 mg | 15 mg | 15 mg | 12.5 mg | 10 mg | 10 mg | 7.5 mg | 7.5 mg | 5 mg | 2.5 mg | 0 mg |

Maintaining remission

Immunosuppressants (thiopurines, methotrexate) and/or biologics (adalimumab, infliximab) are generally used to maintain remission in children and adolescents with Crohn’s disease (11). Because of the high relapse rate after cessation of EEN, in moderate to severe Crohn’s disease immunomodulators (i.e. thiopurines, or methotrexate if thiopurines are not tolerated) should be used to maintain remission at the same time as EEN is begun to induce it. Partial enteral nutrition (PEN), if appropriate in combination with 5-aminosalicylates (if there is only colonic involvement), can be used as maintenance therapy if the patient responds well to EEN and Crohn’s disease activity is initially mild (11). Even when Crohn’s disease activity is initially moderate or severe, PEN can be used as supportive therapy in addition to pharmacological maintenance therapy. Budesonide is used rarely and only for selected Crohn’s disease patients under the age of 18 years with mild to moderate ileocecal involvement (11). In children and adolescents with ulcerative colitis, 5-aminosalicylates are used to maintain remission, in combination with thiopurines or biologics (infliximab) if involvement is extensive or severe (12). Surgery is an established part of therapy for serious or complicated progression in the long term. Indications for surgery in children and adolescents with IBD are de facto the same as for adults; as it is known to have the potential for complications, it should be performed only by surgeons experienced in IBD surgery (e28). Finally, due to the trials conducted to date and drug authorizations for children and adolescents with IBD, off-label drug use or individualized treatment approaches such as other biologics (e.g. vedolizumab, ustekinumab, or golimumab in children under the age of 6 years) are often required (27).

Acute severe ulcerative colitis

Acute severe ulcerative colitis in children and adolescents is treated with methylprednisolone (1 to 1.5 mg/kg/day intravenously in 2 divided doses, maximum 60 mg/day) (13, 33). Until thiopurines take effect, second-line treatment involves calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine, tacrolimus) or infliximab. TNF-a blockers (infliximab) are an option for maintenance therapy if there is no response to thiopurines, steroids are not tolerated, or if there is increased cyclosporine toxicity (13). Subtotal colectomy with ileostomy should be considered early in cases of acute severe ulcerative colitis or toxic megacolon if there is no response to conservative treatment (13).

Optimizing treatment

Treatment adherence problems are not uncommon, particularly during puberty and among adolescents (e29). Adherence has been found to decrease between the ages of 7 and 17 years (e30). Optimization of existing treatment should be the first step if treatment failure is suspected and before every escalation of therapy. This includes checking medication adherence, dosing, and efficacy. In addition, therapeutic drug monitoring with testing for thiopurine metabolites (6-TGN and 6-MMP) or for trough levels and antibodies against infliximab and adalimumab (29, 34) and biomarker dynamics (particularly fecal calprotectin) plays an important role in the treatment of children and adolescents with IBD. This is particularly true when thiopurines and/or TNF-a blockers lose clinical efficacy (e9, e10). Testing for thiopurine metabolites is part of checking for adherence.

Long-term treatment

Follow-up

Subsequent checkups performed by a pediatric gastroenterologist are usually required at least every 3 months (more frequently in complicated or treatment-refractory cases). These are particularly important to enable impaired growth, delayed puberty, nutritional deficiencies, drug side effects, opportunistic and other infections, and extraintestinal manifestations to be treated promptly (35, e31). Endoscopic or histological re-evaluation is indicated before major changes to treatment and when response to treatment is uncertain (12). Colitis-associated cancers can occur in IBD patients even before the age of 18 years and necessitate appropriate screening (35, 36).

Growth and nutrition

Impaired growth can be prevented or mitigated through swift diagnosis (calculation of genetic target height, growth prognosis based on bone age), appropriate/intensive treatment with sparing corticosteroid use, and sufficient energy/nutrient intake (36). Children and adolescents with IBD require concomitant treatment by nutritional therapists, as their nutritional status is usually critical (37, e32, e33). Intravenous ferric carboxymaltose is the preferred treatment for iron deficiency, which is common. Vitamin D should be administered at a dose of 600 IU/day in children and adolescents with IBD, as for healthy children and adolescents; the recommended calcium intake is 1000 mg/day for children aged between 4 and 8 years and 1300 mg/day for those aged 9 to 18 years. Children and adolescents with IBD require regular vitamin D and calcium supplementation, as regular family food often fails to comply with these recommendations (35, 36, e34, e35). Alternatively, single oral administration of vitamin D3 may be sufficient (e36). The target serum concentration of 25 hydroxyvitamin D (25-OHD) is above 30 ng/mL (e37).

Psychosocial treatment

Children and adolescents with IBD are at increased risk of psychosocial problems and psychiatric illness (particularly depression). These can have adverse effects on school attendance, education, leisure activities, medication adherence, and quality of life (38, e38– e41). Case studies suggest that 25 to 40% of IBD patients, usually adolescents, show signs of clinical depression (e42, e43). Concomitant treatment in the form of initial psychological counselling/evaluation and, if necessary, psychotherapy is therefore recommended for children and adolescents with IBD (e44, e45).

Transition

A structured transition program (e.g. the Berlin Transition Program) should provide a comprehensive, accompanied transition from adolescent to adult care, with costs covered. This is because deficiencies in care during this particularly critical phase result in treatment interruptions, insufficient treatment compliance, and increased frequency of complications that are probably avoidable (10, 39, e28, e46, e47).

Additional information on IBD is provided by the German-speaking Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition (GPGE, Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Gastroenterologie und Ernährung) at www.gpge.de and the German Association for Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (DCCV, Deutsche Morbus Crohn/Colitis ulcerosa Vereinigung) at www.dccv.de.

Figure 2.

Treatment algorithms for children and adolescents with ulcerative colitis: a) mild to moderate activity; b) high activity

Black arrows: clinical response to treatment; red arrows: no response to treatment within the stated time period or treatment refused; ±: administer if required; BW: body weight

Adalimumab has not been formally authorized in Germany for the treatment of ulcerative colitis in children or adolescents (off-label use).

The procedure outlined here is closely based on the consensus recommendations of international specialized societies (ECCO, ESPGHAN) (12, 13).

Key Messages.

There are differences between the diagnosis and treatment of children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and treatment recommendations for adults.

The most common extraintestinal manifestation of IBD, particularly Crohn’s disease, in childhood and adolescence is impaired growth/growth retardation.

Children and adolescents with IBD are at increased risk of psychosocial problems and psychiatric illness.

Children and adolescents with IBD require concomitant treatment by nutritional therapists to prevent and treat malnutrition.

Treatment adherence falls between the ages of 7 and 17 years. It is particularly problematic during puberty and in adolescents.

eBOX. Differences between IBD treatment for children and adolescents and for adults.

First-line treatment for children and adolescents with Crohn’s disease, regardless of severity, is exclusive enteral nutrition.

Pharmacological maintenance therapy lasting several years—usually at least until the end of puberty or transition to adult care—is indicated for patients who have not yet reached adulthood.

In adults with Crohn’s disease, abstinence from nicotine use is indicated to maintain remission, but pharmacological therapy is not.

Primary treatment for children and adolescents with Crohn’s disease and anal fistulae is infliximab therapy. This option is not part of adult treatment algorithms.

Thiopurines are of considerably more benefit in maintaining IBD remission (e.g. to reduce steroid use) in children and adolescents than in adults.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Caroline Shimakawa-Devitt, M.A.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Däbritz has received consultancy and lecture fees and reimbursement of travel expenses from Abbvie, Nestlé, Shire, Humana, and Takeda.

Prof. Gerner has received consultancy fees from Abbvie and lecture fees and reimbursement of travel expenses from Abbvie and MSD.

Dr. Enninger has received consultancy fees from the Nestlé Nutrition Institute and lecture fees and reimbursement of travel expenses from Abbvie, Nutricia, and the Nestlé Nutrition Institute.

Dr. Claßen has received lecture fees from Abbvie, Falk, Nestlé, Nutricia, and MSD; reimbursement of travel expenses from Abbvie and MSD; and funding for a commissioned clinical study from Janssen Biologics B.V.

Prof. Radke has received consultancy fees from MSD and Abbvie; reimbursement of travel expenses from MSD, Abbvie, Falk, and Nestlé; lecture fees from MSD, Abbvie, and Falk; authors’ fees from MSD and Abbvie; and research funding from MSD.

References

- 1.Preiß JC, Bokemeyer B, Buhr HJ, et al. [Updated German clinical practice guideline on “diagnosis and treatment of Crohn‘s disease” 2014] Z Gastroenterol. 2014;52:1431–1484. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1385199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dignass A, Preiß JC, Aust DE, et al. [Updated German guideline on diagnosis and treatment of ulcerative colitis, 2011] Z Gastroenterol. 2011;49:1276–1341. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1281666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benchimol EI, Fortinsky KJ, Gozdyra P, van den Heuvel M, van Limbergen J, Griffiths AM. Epidemiology of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of international trends. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:423–439. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jakobsen C, Bartek J Jr., Wewer V, et al. Differences in phenotype and disease course in adult and paediatric inflammatory bowel disease—a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1217–1224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosen MJ, Dhawan A, Saeed SA. Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:1053–1060. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sauer CG, Kugathasan S. Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: highlighting pediatric differences in IBD. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94:35–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Assa A, Avni I, Ben-Bassat O, Niv Y, Shamir R. Practice variations in the management of inflammatory bowel disease between pediatric and adult gastroenterologists. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:372–377. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyams JS, Ferry GD, Mandel FS, et al. Development and validation of a pediatric Crohn‘s disease activity index. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1991;12:439–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner D, Otley AR, Mack D, et al. Development, validation, and evaluation of a pediatric ulcerative colitis activity index: a prospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:423–432. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baldassano R, Ferry G, Griffiths A, Mack D, Markowitz J, Winter H. Transition of the patient with inflammatory bowel disease from pediatric to adult care: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;34:245–248. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200203000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruemmele FM, Veres G, Kolho KL, et al. Consensus guidelines of ECCO/ESPGHAN on the medical management of pediatric Crohn‘s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1179–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turner D, Levine A, Escher JC, et al. Management of pediatric ulcerative colitis: joint ECCO and ESPGHAN evidence-based consensus guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:340–361. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182662233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner D, Travis SP, Griffiths AM, et al. Consensus for managing acute severe ulcerative colitis in children: a systematic review and joint statement from ECCO, ESPGHAN, and the Porto IBD Working Group of ESPGHAN. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:574–588. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buderus S, Scholz D, Behrens R, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in pediatric patients—characteristics of newly diagnosed patients from the CEDATA-GPGE registry. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:121–127. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timmer A, Behrens R, Buderus S, et al. Childhood onset inflammatory bowel disease: predictors of delayed diagnosis from the CEDATA German-language pediatric inflammatory bowel disease registry. J Pediatr. 2011;158:467–473 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levine A, Koletzko S, Turner D, et al. ESPGHAN revised porto criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:795–806. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benninga MA, Faure C, Hyman PE, St James Roberts I, Schechter NL, Nurko S. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: neonate/toddler. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1443–1455. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hyams JS, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, Shulman RJ, Staiano A, van Tilburg M. Functional disorders: children and adolescents. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1456–1468. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harbord M, Annese V, Vavricka SR, et al. The first European evidence-based consensus on extra-intestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:239–254. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kammermeier J, Dziubak R, Pescarin M, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic characterisation of inflammatory bowel disease presenting before the age of 2 years. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:60–69. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uhlig HH, Schwerd T, Koletzko S, et al. The diagnostic approach to monogenic very early onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:990–1007 e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabo IR, et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:136–160. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31821a23d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papadopoulou A, Koletzko S, Heuschkel R, et al. Management guidelines of eosinophilic esophagitis in childhood. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:107–118. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182a80be1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koletzko S, Niggemann B, Arato A, et al. Diagnostic approach and management of cow‘s-milk protein allergy in infants and children: ESPGHAN GI Committee practical guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:221–229. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31825c9482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caubet JC, Szajewska H, Shamir R, Nowak-Wegrzyn A. Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergies in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2017;28:6–17. doi: 10.1111/pai.12659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levine A, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, et al. Pediatric modification of the Montreal classification for inflammatory bowel disease: the Paris classification. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1314–1321. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wehkamp J, Gotz M, Herrlinger K, Steurer W, Stange EF. Inflammatory bowel disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:72–82. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruemmele FM, Hyams JS, Otley A, et al. Outcome measures for clinical trials in paediatric IBD: an evidence-based, expert-driven practical statement paper of the paediatric ECCO committee. Gut. 2015;64:438–446. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benkov K, Lu Y, Patel A, et al. Role of thiopurine metabolite testing and thiopurine methyltransferase determination in pediatric IBD. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:333–340. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182844705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zachos M, Tondeur M, Griffiths AM. Enteral nutritional therapy for induction of remission in Crohn‘s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000542.pub2. CD000542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Day AS, Whitten KE, Sidler M, Lemberg DA. Systematic review: nutritional therapy in paediatric Crohn‘s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:293–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dziechciarz P, Horvath A, Shamir R, Szajewska H. Meta-analysis: enteral nutrition in active Crohn‘s disease in children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:795–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turner D, Griffiths AM. Acute severe ulcerative colitis in children: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:440–449. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jossen J, Dubinsky M. Therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016;28:620–625. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rufo PA, Denson LA, Sylvester FA, et al. Health supervision in the management of children and adolescents with IBD: NASPGHAN recommendations. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:93–108. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31825959b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeFilippis EM, Sockolow R, Barfield E. Health care maintenance for the pediatric patient with inflammatory bowel disease. Pediatrics. 2016;138 doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1971. e20151971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forbes A, Escher J, Hebuterne X, et al. ESPEN guideline: clinical nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nutr. 2017;36:321–347. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brooks AJ, Rowse G, Ryder A, Peach EJ, Corfe BM, Lobo AJ. Systematic review: psychological morbidity in young people with inflammatory bowel disease—risk factors and impacts. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:3–15. doi: 10.1111/apt.13645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeisler B, Hyams JS. Transition of management in adolescents with IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:109–115. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Turner D, Levine A, Walters TD, et al. Which PCDAI version best reflects intestinal inflammation in pediatric Crohn‘s disease? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64:254–260. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Louis E, Dotan I, Ghosh S, Mlynarsky L, Reenaers C, Schreiber S. Optimising the inflammatory bowel disease unit to improve quality of care: expert recommendations. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:685–691. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Kugathasan S, Baldassano RN, Bradfield JP, et al. Loci on 20q13 and 21q22 are associated with pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1211–1215. doi: 10.1038/ng.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Furuta GT, Forbes D, Boey C, et al. Eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (EGIDs) J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:234–238. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318181b1c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Magro F, Langner C, Driessen A, et al. European consensus on the histopathology of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:827–851. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Annese V, Daperno M, Rutter MD, et al. European evidence based consensus for endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:982–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the Crohn‘s and Colitis Foundation of America. Differentiating ulcerative colitis from Crohn disease in children and young adults: report of a working group of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the Crohn‘s and Colitis Foundation of America. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:653–674. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31805563f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749–753. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.082909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Dabritz J, Musci J, Foell D. Diagnostic utility of faecal biomarkers in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:363–375. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i2.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Musci JO, Cornish JS, Dabritz J. Utility of surrogate markers for the prediction of relapses in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:531–547. doi: 10.1007/s00535-016-1191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Hyams J, Crandall W, Kugathasan S, et al. Induction and maintenance infliximab therapy for the treatment of moderate-to-severe Crohn‘s disease in children. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:863–873. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Hyams J, Damaraju L, Blank M, et al. Induction and maintenance therapy with infliximab for children with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:391–399 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Hyams JS, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, et al. Safety and efficacy of adalimumab for moderate to severe Crohn‘s disease in children. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:365–374 e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Ruemmele FM, Lachaux A, Cezard JP, et al. Efficacy of infliximab in pediatric Crohn‘s disease: a randomized multicenter open-label trial comparing scheduled to on demand maintenance therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:388–394. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Quiros JA, Heyman MB, Pohl JF, et al. Safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics of balsalazide in pediatric patients with mild-to-moderate active ulcerative colitis: results of a randomized, double-blind study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:571–579. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31819bcac4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Griffiths A, Koletzko S, Sylvester F, Marcon M, Sherman P. Slow-release 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy in children with small intestinal Crohn‘s disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;17:186–192. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199308000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Markowitz J, Grancher K, Kohn N, Lesser M, Daum F. A multicenter trial of 6-mercaptopurine and prednisone in children with newly diagnosed Crohn‘s disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:895–902. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.18144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Escher JC European Collaborative Research Group on Budesonide in Paediatric IBD. Budesonide versus prednisolone for the treatment of active Crohn‘s disease in children: a randomized, double-blind, controlled, multicentre trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:47–54. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200401000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Romano C, Famiani A, Comito D, Rossi P, Raffa V, Fries W. Oral beclomethasone dipropionate in pediatric active ulcerative colitis: a comparison trial with mesalazine. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:385–389. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181bb3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Ferry GD, Kirschner BS, Grand RJ, et al. Olsalazine versus sulfasalazine in mild to moderate childhood ulcerative colitis: results of the Pediatric Gastroenterology Collaborative Research Group Clinical Trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;17:32–38. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199307000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Cezard JP, Munck A, Mouterde O, et al. Prevention of relapse by mesalazine (Pentasa) in pediatric Crohn‘s disease: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gcb.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Levine A, Weizman Z, Broide E, et al. A comparison of budesonide and prednisone for the treatment of active pediatric Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;36:248–252. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200302000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Boyle BM, Kappelman MD, Colletti RB, Baldassano RN, Milov DE, Crandall WV. Routine use of thiopurines in maintaining remission in pediatric Crohn‘s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9185–9190. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i27.9185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Schleker T, Speth F, Posovszky C. Impfen beim immunsupprimierten Kind. Pädiatrische Praxis. 2016;85:363–384. [Google Scholar]

- E25.Wasan SK, Baker SE, Skolnik PR, Farraye FA. A practical guide to vaccinating the inflammatory bowel disease patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1231–1238. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E26.Coenen MJ, de Jong DJ, van Marrewijk CJ, et al. Identification of patients with variants in TPMT and dose reduction reduces hematologic events during thiopurine treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:907–1017 e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Heuschkel RB, Gottrand F, Devarajan K, et al. ESPGHAN position paper on management of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60:131–141. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Radke M. [Chronic inflammatory bowel disease: transition from pediatric to adult care] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2015;140:673–678. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-101713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.Spekhorst LM, Hummel TZ, Benninga MA, van Rheenen PF, Kindermann A. Adherence to oral maintenance treatment in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:264–270. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.LeLeiko NS, Lobato D, Hagin S, et al. Rates and predictors of oral medication adherence in pediatric patients with IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:832–839. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182802b57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E31.Veereman-Wauters G, de Ridder L, Veres G, et al. Risk of infection and prevention in pediatric patients with IBD: ESPGHAN IBD Porto Group commentary. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:830–837. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31824d1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E32.Bischoff SC, Koletzko B, Lochs H, Meier R. [Clinical nutrition in gastroenterology (part 4)—inflammatory bowel diseases] Aktuel Ernahrungsmed. 2014;39:e72–e98. [Google Scholar]

- E33.Valentini L, Volkert D, Schütz T, et al. [DGEM terminology for clinical nutrition] Aktuel Ernahrungsmed. 2013;38:97–111. [Google Scholar]

- E34.Levin AD, Wadhera V, Leach ST, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:830–836. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1544-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E35.Pappa HM, Mitchell PD, Jiang H, et al. Maintenance of optimal vitamin D status in children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a randomized clinical trial comparing two regimens. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:3408–3417. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E36.Shepherd D, Day AS, Leach ST, et al. Single high-dose oral vitamin D3 therapy (Stoss): a solution to vitamin D deficiency in children with inflammatory bowel disease? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;61:411–414. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E37.Pappa H, Thayu M, Sylvester F, Leonard M, Zemel B, Gordon C. Skeletal health of children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:11–25. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31821988a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E38.Engelmann G, Erhard D, Petersen M, et al. Health-related quality of life in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease depends on disease activity and psychiatric comorbidity. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2015;46:300–307. doi: 10.1007/s10578-014-0471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E39.Kilroy S, Nolan E, Sarma KM. Quality of life and level of anxiety in youths with inflammatory bowel disease in Ireland. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:275–279. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318214c131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E40.Reigada LC, Hoogendoorn CJ, Walsh LC, et al. Anxiety symptoms and disease severity in children and adolescents with Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60:30–35. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E41.Giannakopoulos G, Chouliaras G, Margoni D, et al. Stressful life events and psychosocial correlates of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease activity. World J Psychiatry. 2016;6:322–328. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v6.i3.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E42.Szigethy E, Levy-Warren A, Whitton S, et al. Depressive symptoms and inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents: a cross-sectional study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:395–403. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200410000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E43.Clark JG, Srinath AI, Youk AO, et al. Predictors of depression in youth with Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:569–573. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E44.Thompson RD, Craig A, Crawford EA, et al. Longitudinal results of cognitive behavioral treatment for youths with inflammatory bowel disease and depressive symptoms. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2012;19:329–337. doi: 10.1007/s10880-012-9301-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E45.Keethy D, Mrakotsky C, Szigethy E. Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease and depression: treatment implications. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2014;26:561–567. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E46.Paine CW, Stollon NB, Lucas MS, et al. Barriers and facilitators to successful transition from pediatric to adult inflammatory bowel disease care from the perspectives of providers. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:2083–2091. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E47.Müther S, Rodeck B, Wurst C, Nolting HD. [Transition to adult care for adolescents with chronic disease Current developments] Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2014;162:711–718. [Google Scholar]