Abstract

This study uses data from a survey of NIH Mentored Career Development grant awardees to determine if sponsorship critical for career advancement of young professionals differs among men and women.

The term sponsorship describes advocacy on behalf of a high-potential junior person by powerful senior leaders that is critical for the career advancement of young professionals. Distinct from the advisory role of a mentor, sponsorship requires senior leaders to risk their reputations by using their influence to provide high-profile opportunities that their mentees would otherwise not have.

In business, women benefit less from sponsorship than men, which may contribute to a “gender gap” in leadership. Lack of sponsorship may play a similar role in a “gender gap” among leaders in academic medicine. We surveyed National Institutes of Health (NIH) Mentored Career Development (K) grant awardees to determine if sponsorship differs among men and women.

Methods

As part of a broader study of career development, we conducted a postal survey in 2014 of all recipients of NIH K08 and K23 grants awarded in from January 2006 to December 2009 who remained in academic positions by 2014 to assess sponsorship experiences and the impact of sponsorship on academic success. Academic success was defined as satisfying at least 1 of the following criteria: (1) serving as principal investigator on an R01 or grants totaling more than $1 million since receipt of K award; (2) publishing 35 or more peer-reviewed publications; or (3) appointment as dean, department chair or division chief. Respondents were asked to report sponsorship experiences, including an invitation to serve as an oral discussant or panelist at a national meeting, write an editorial, serve on an editorial board, or serve on a national committee, including NIH study section or grant review panel. Sex of mentors and mentees was determined by self-report. We also created a single composite binary measure of sponsorship, defined as reporting at least 1 of these 4 sponsorship experiences. Respondents were also asked if their mentor acted as a sponsor by helping them obtain desirable positions or creating opportunities for them to impress important people. We used the χ2 tests to assess the association of the composite measure of sponsorship and academic success and to compare proportions between men and women. Additionally we constructed multiple variable logistic models for the composite measure of success and for its components as outcomes separately to adjust the estimated effect of the sex of the mentee for mentee demographics (age, race), job characteristics (grant type, year of grant award, medical specialty), level of funding for the NIH institute that granted the K award, and the level of NIH funding received by the individual’s institution of employment.

Results

Of the 1066 respondents (62.4% of 1708 originally surveyed), 995 remained in academic medicine in 2014 and constituted the analytic sample; 461 (46%) were women, 703 (71%) white, and mean (SD) age was 43 (4.3) years. Sponsorship was significantly associated with success (P < .001); 298 of 411 men (72.5%) and 193 of 327 women (59.0%) who reported sponsorship were successful, compared with 71 of 123 men (57.7%) and 60 of 134 women (44.8%) who did not report sponsorship.

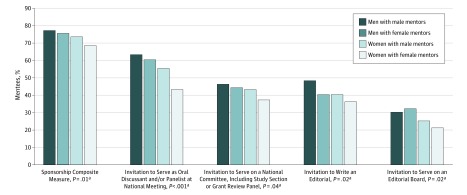

Any sponsorship experience, as well as specific sponsorship experiences, were more commonly reported by men than women, with significant differences between men and women (Figure). No sex differences were observed for perceptions of the mentor’s use of influence to support the mentee’s advancement (290 of 449 women [64.6%] and 344 of 527 men [65.3%]; P = .16) or bringing the mentee’s accomplishments to the attention of important people (260 of 449 women [57.9%] and 319 of 531 [60.5%]; P = .44).

Figure. Experiences of Sponsorship by Sex.

This graph depicts self-reported experiences of sponsorship by K08 and K23 award recipients for men with male mentors (n = 442), men with female mentors (n = 89), women with male mentors (n = 323), and women with female mentors (n = 131). Unadjusted percentages are depicted for each of 4 individual sponsorship experiences and for a composite binary measure of having reported at least 1 of the 4 individual experiences.

aP values evaluate the presence of a difference between men and women holding National Institutes of Health (NIH) Mentored Career Development (K) awards in regression models that adjust for other demographic characteristics (age, race), job characteristics (grant type, year of grant award, medical specialty), level of funding for the NIH institute that granted the K award, and level of NIH funding received by the individual’s institution of employment.

Discussion

What might explain these sex differences in sponsorship? Female mentees may have less powerful mentors who are therefore unable to act as sponsors, may less actively request sponsorship opportunities, or may require (or be viewed as requiring) other types of mentorship (such as advice on navigating professional obstacles based on sex or work-life balance) that crowds out the time mentors have to pursue sponsorship; also, mentors may be less likely to think of female mentees for sponsorship opportunities. Much less likely, given this highly qualified cohort, is that male mentees received more sponsorship based on superior merit.

Given that sponsorship appears common and is associated with success, further attention to gender equity in this regard is critical. Male and female mentors alike should consciously act as sponsors by reviewing opportunities and offering high-profile opportunities to mentees. Mentees should seek connections with higher-level leaders to cultivate sponsors as part of their mentorship team. More widespread sponsorship may not only enhance the careers of individual women but may also help to increase the diversity of perspectives leading the national conversation in academic medicine.

References

- 1.Hewlett S, Peraino K, Sherbin L, Sumberg K; the Center for Work-Life Policy . The Sponsor Effect: Breaking Through the Last Glass Ceiling. Harvard Business Review Research Report 2010. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing; 2010. https://hbr.org/product/the-sponsor-effect-breaking-through-the-last-glass-ceiling/10428-PDF-ENG. Accessed January 19, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewlett SA. Forget a Mentor, Find a Sponsor. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foust-Cummings H, Dinolfo S, Kohler J Sponsoring women to success. Catalyst Report. 2011. http://www.catalyst.org/system/files/sponsoring_women_to_success.pdf. Accessed December 13, 2016.

- 4.Travis EL, Doty L, Helitzer DL. Sponsorship: a path to the academic medicine C-suite for women faculty? Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1414-1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jagsi R, DeCastro R, Griffith KA, et al. . Similarities and differences in the career trajectories of male and female career development award recipients. Acad Med. 2011;86(11):1415-1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]