Abstract

The US continues to lead the world in research and development (R&D) expenditures, but there is concern that stagnation in federal support for biomedical research in the US could undermine the leading role the US has played in biomedical and clinical research discoveries. As a readout of research output in the US compared with other countries, assessment of original research articles published by US-based authors in ten clinical and basic science journals during 2000 to 2015 showed a steady decline of articles in high-ranking journals or no significant change in mid-ranking journals. In contrast, publication output originating from China-based investigators, in both high- and mid-ranking journals, has steadily increased commensurate with significant growth in R&D expenditures. These observations support the current concerns of stagnant and year-to-year uncertainty in US federal funding of biomedical research.

Biomedical research drives discovery and advances our understanding of human health and disease. The research enterprise also plays significant developmental and economic roles, fuels training of the next generation of physician and scientist investigators, and creates new technologies and jobs. Despite its importance, federal support for biomedical research in the US has been relatively unchanged for over a decade. For example, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which provides the bulk of federal funding for biomedical research, has had an essentially flat budget of ~$30 billion since 2008 until the $2 billion increase in 2016 for a total of ~$32 billion (1) and the additional increase of $2 billion for fiscal year 2017 that will boost the NIH budget to ~$34 billion (2). Although much of the budget increases have been directed to earmarked initiatives (e.g., Alzheimer disease, with $400 million of additional funds in 2017), the increase is welcome since the earmarks allow a potential net gain of support for investigator-initiated research. This stagnation in federal support for research raises many concerns, including whether the US will ultimately lose its global lead in biomedical research output and innovation as measured by scientific research articles, patents, and science and technology workforce (3). This concern is fueled by the relative decline in public sector and private industry research and development (R&D) expenditures in the US (compound –1.9% annual growth rate for 2007 to 2012, adjusted for inflation), as compared with an increase of 32.8% for China and 10%–11% for Singapore and South Korea (4).

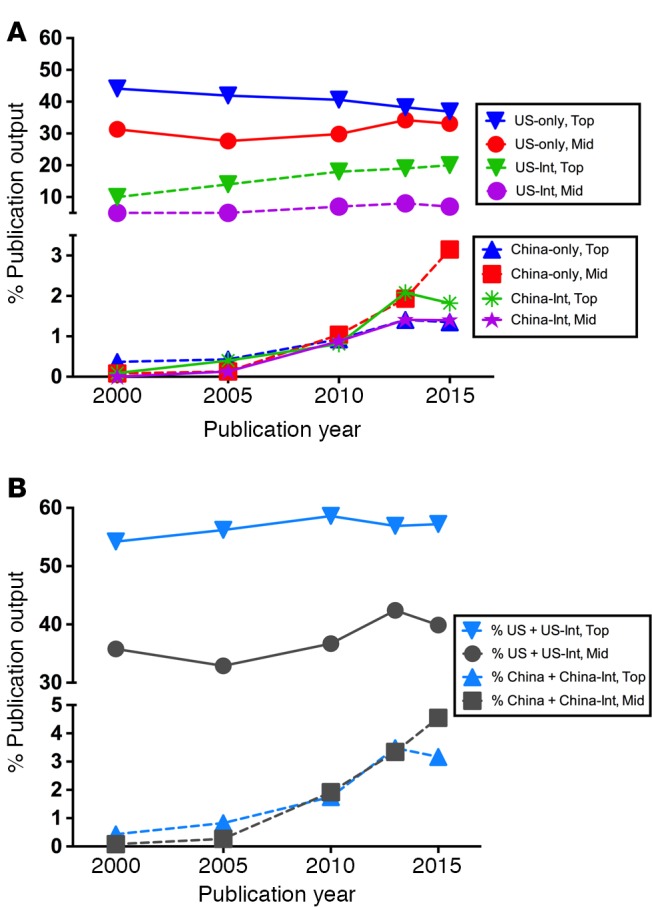

As a measure of research output, we analyzed a select group of high-ranking clinical (JAMA, Lancet, New England Journal of Medicine) and basic science (Cell, Nature, Science), and mid-ranking clinical (British Medical Journal, JAMA Internal Medicine) and basic science (Journal of Cell Science, FASEB Journal) journals. The number of original research publications for these journals was individually and systematically estimated for the years 2000, 2005, 2010, 2013, and 2015 (see supplemental section for methods of accruing the articles; reviews, editorials, and commentaries were not included in the analysis; supplemental material available online with this article; https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.95206DS1). For each article, the reported countries of origin for the corresponding authors and collaborators were tabulated, and manuscripts were classified into those arising from collaborations from one or more countries (e.g., the US vs. non-US). The percentage of basic and clinical manuscripts in high-ranking journals that include international collaborations increased from 26% of total publications in 2000 to 47% in 2015 (Supplemental Table 1), commensurate with a dramatic increase in the average number of papers with multiple authors (Supplemental Table 2). Although the percentage of papers published in high-ranking journals that originated solely from US-based authors decreased during 2000 to 2015, this was accompanied by an increase in papers from US-based corresponding authors in collaboration with international investigators (Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 1). During this 15-year span, the US maintained the highest ranking in terms of producing the most basic and clinical research articles published in high-ranking journals (Table 1; the same applies to publications in mid-ranking journals, Supplemental Table 3). Notably, China ranked as number 14 during 2000 with 0.4% of total high-impact article output, but gradually and steadily ascended to the fourth-ranked country with 1.4% of the total output (Table 1). The rise in output from China was noted in all manuscript categories we examined, including manuscripts that involved collaboration by China and other international authors (Figure 1). Great Britain and Germany maintained their second and third ranking, respectively; however, one notable drop in the ranking was Italy, which was among the top ten during 2000 and 2005 (Table 1) but moved outside the top-ten list for the years 2010, 2013, and 2015.

Figure 1. Biomedical research publication output for the US and China from 2000 to 2015.

(A) The percentage of manuscripts originating from China or the US that include international collaborations has been steadily increasing during the past 15 years regardless of the journal impact (China: P = 0.03 for high-impact and P = 0.008 for mid-impact journals; US: P = 0.001 for high-impact and P = 0.05 for mid-impact journals). In contrast, the percentage of manuscripts that originated from US-based authors during 2000 to 2015 has decreased in high-impact journals (P = 0.007) or remained relatively unchanged for mid-impact journals (P = 0.28), while those originating from China-based authors has steadily increased in both high-impact (P = 0.02) and mid-impact journals (P = 0.04). (B) The percentage of manuscripts from the combined China-only authors and China-international collaborations has been steadily increasing regardless of the journal type (P = 0.001 and 0.04 for high- and mid-impact journals, respectively), while there has not been a significant change for the combined US-only and US-international publications for high-impact (P = 0.17) or mid-impact (P = 0.15) journals.

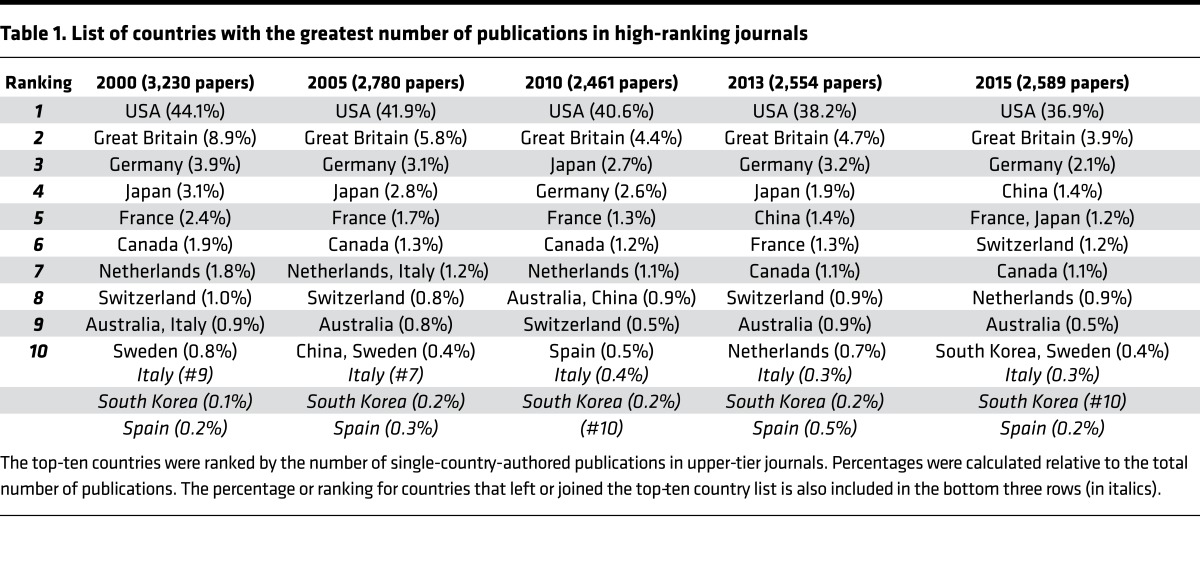

Table 1. List of countries with the greatest number of publications in high-ranking journals.

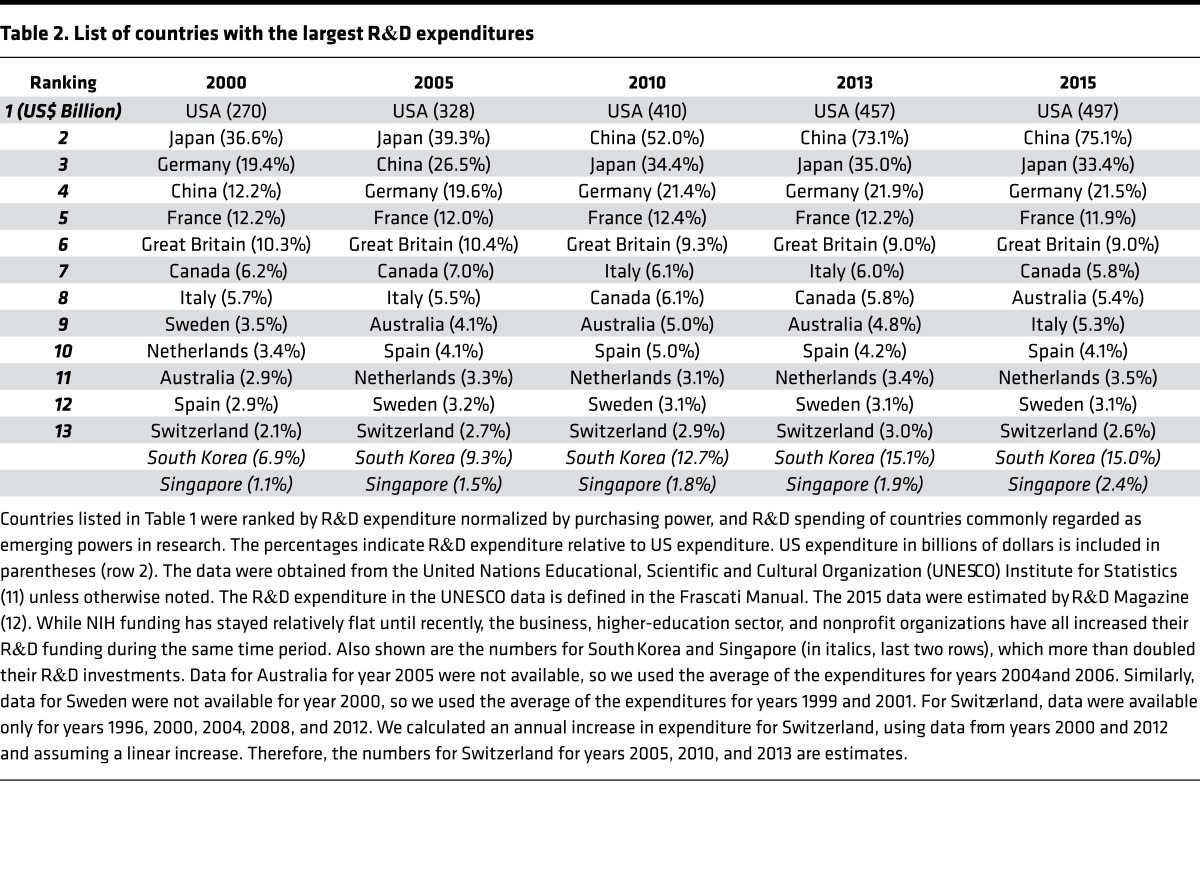

Parallel to the rise of China in terms of publication output is the dramatic increase in R&D expenditures (normalized by purchasing power) relative to US expenditures. For example, China expenditures in 2000 were only 12.2% of the US, but this increased steadily and dramatically to more than 70% during 2013 and 2015 (Table 2). Of the top-ten countries in R&D expenditures after the US, China is the only country that has catapulted, while the remaining countries have not had major shifts in their expenditures (Table 2).

Table 2. List of countries with the largest R&D expenditures.

The analysis we describe provides a detailed snapshot of 2000 to 2015 trajectories from ten journals that cover clinical and basic sciences. This is a very small number compared with the full corpus of research publications — there are more than 17,000 science and engineering journals listed in the Scopus database alone. However, our in-depth analysis of the ten journals allowed us to discern the publication trends between journals of different rankings and journals of basic and clinical research. The general trends we observe are similar to those identified in larger samples. For example, the output for China has increased significantly when comparing total science and engineering articles in 2003 (6.4% for China vs. 26.8% for the US of total world publications) versus 2013 (18.2% for China vs. 18.8% for the US) (5). This indicates that our sample analysis is likely to be representative of other top journals, though it is possible that the trends may be different for subdisciplines in the biomedical sciences. The steady increase in international collaborations in the ten journals we examined (Supplemental Table 1) is also evident across all science and engineering disciplines (ranging from astronomy to biological, medical, and social sciences) as detailed in the 2016 National Science Foundation (NSF) report that compared data from 2000 versus 2013 (5).

In summary, our analysis shows that, even though the US still has a pronounced presence in biomedical research publications, there is a shift toward US-international collaboration instead of US-based research coupled with a decline in US-based research published in high-ranking journals (Figure 1). The increase in US-international collaboration is more obvious in high-ranking than mid-ranking journals, suggesting that this trend is indicative of a decline in US discoveries instead of the adoption of a more collaborative research culture. Should this decline alarm US researchers and policy makers? The good news is that the US clearly continues to lead in terms of its output and its investment in R&D (Figure 1, Tables 1 and 2, and refs. 2, 4, 5). However, stagnation of research funding in the US is a major concern that is compounded by year-to-year uncertainty in funding and the dependence on annual budget approval by Congress. Although throwing money at a problem is not a cure, the investments in R&D that China (6) and South Korea (7) have made are paying off in publication output, while investments in R&D as a percentage of the gross domestic product in the US and the European Union have been relatively flat for several years (7). If current trends in R&D investments continue, it is predicted that China’s support for research will exceed that of the US by 2022 (8). In addition to the need to enhance and stabilize the investment in fundamental and translational research and training, there are both strain and drain problems in the biomedical research enterprise and its workforce that have been eloquently highlighted (9) but not addressed. Increased and stable support for the NIH, NSF, and other federal funding agencies is needed, together with investments and support by businesses (e.g., a recent ad by business leaders published in the Wall Street Journal; ref. 10). Importantly, strong input and endorsement by the public with engagement by the research community are also essential if we are to maintain the lead in biomedical research that the US has enjoyed. The implications are immense, including economic and societal in addition to security and global ramifications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Scott Friedman for his helpful comments.

Footnotes

Address correspondence to: Marisa Conte, Taubman Health Sciences Library, University of Michigan, 1135 E. Catherine Street, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-2038, USA. Or to: Bishr Omary, Department of Molecular & Integrative Physiology, University of Michigan Medical School, 7720 Medical Science II, 1301 E. Catherine Street, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-5622, USA.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Published: June 15, 2017

Reference information:JCI Insight. 2017;2(12):e95206. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.95206.

Contributor Information

Jing Liu, Email: ljing@umich.edu.

Santiago Schnell, Email: schnells@umich.edu.

References

- 1. Appropriations (Section 2). National Institutes of Health. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/what-we-do/nih-almanac/appropriations-section-2 Updated April 17, 2016. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- 2. How science fares in the U.S. budget deal. Science. http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/05/how-science-fares-us-budget-deal Published May 1, 2017. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- 3.Moses H, Matheson DH, Cairns-Smith S, George BP, Palisch C, Dorsey ER. The anatomy of medical research: US and international comparisons. JAMA. 2015;313(2):174–189. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakma J, Sun GH, Steinberg JD, Sammut SM, Jagsi R. Asia’s ascent--global trends in biomedical R&D expenditures. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(1):3–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1311068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Science and Engineering Indicators. National Science Foundation. https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2016/nsb20161/uploads/1/nsb20161.pdf Accessed May 18, 2017.

- 6.Van Noorden R. China by the numbers. Nature. 2016;534(7608):452–453. doi: 10.1038/534452a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zastrow M. Why South Korea is the world’s biggest investor in research. Nature. 2016;534(7605):20–23. doi: 10.1038/534020a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins FS. Exceptional opportunities in medical science: a view from the National Institutes of Health. JAMA. 2015;313(2):131–132. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.16736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alberts B, Kirschner MW, Tilghman S, Varmus H. Opinion: Addressing systemic problems in the biomedical research enterprise. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(7):1912–1913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500969112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Business Leaders agree. Wall Street Journal. September 2016:A14. http://cdn.annenbergpublicpolicycenter.org/wp-content/uploads/Basic_Research_Annenberg_WSJ_9_30_16.pdf Accessed May 18, 2017.

- 11. Science, technology and innovation: Gross domestic expenditure on R&D (GERD), GERD as a percentage of GDP, GERD per capita and GERD per researcher. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. http://data.uis.unesco.org/Index.aspx?queryid=74 Accessed May 18, 2017.

- 12. 2016 Global R&D Funding Forecast. R&D Magazine. https://www.iriweb.org/sites/default/files/2016GlobalR%26DFundingForecast_2.pdf Accessed May 18, 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.