Abstract

Objective

During the clinical encounter, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patient goals for care often go unexplored. The aim of the present systematic review was to identify needs, goals and expectations of RA patients in order better to guide systematic elicitation of patient goals in clinical encounters.

Methods

An academic librarian searched MEDLINE, PsychINFO and the Cochrane Library using a specialized algorithm developed to identify articles about patient goals for RA care. Investigators screened search results according to prespecified inclusion criteria and then reviewed included articles and synthesized the evidence qualitatively, utilizing an inductive approach.

Results

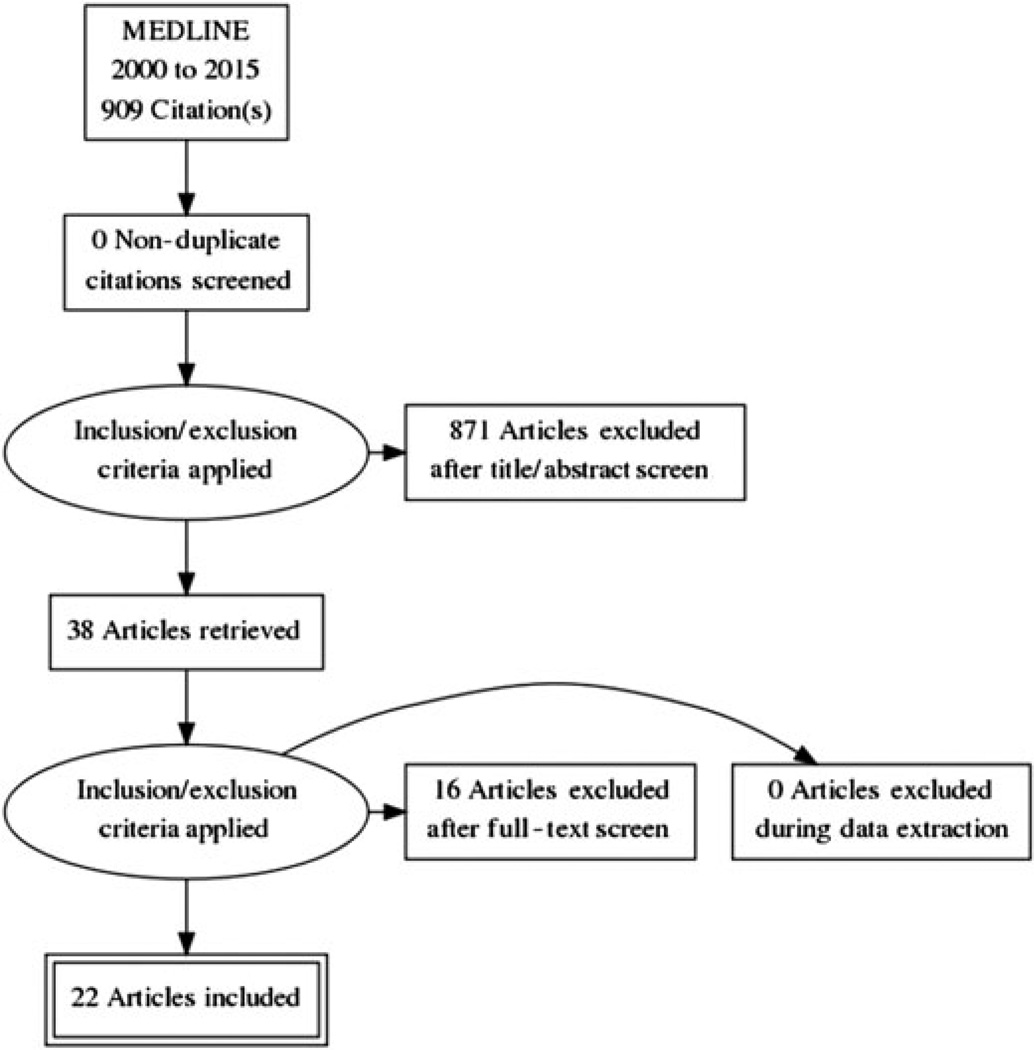

A total of 909 titles were retrieved in the literature search, of which 871 were excluded after a title/abstract screen. Of the remaining 38, 22 papers were included in the final review. Investigators identified four major themes in the literature: (a) the bodily experience of RA; (b) achieving normalcy and maintaining wellness; (c) social connectedness and support; and (d) interpersonal and healthcare system interactions.

Conclusion

Patients’ goals when receiving care for RA are multidimensional and span several facets of everyday life. Goals for RA care should be collaboratively developed between patients and providers, with particular attention to the patient’s life context and priorities.

Keywords: Goals, patient-centred care, patient–physician communication, rheumatoid arthritis

1 | INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) affects up to 1% of the population in the United States, causing significant disability and excess mortality, and incurring up to $20 billion in annual costs (Birnbaum et al., 2010). In the last two decades, advances in treatments and treatment strategies have made remission in RA an achievable outcome, yet, with the expansion of these options, patients and clinicians face complex decisions regarding RA care. Effective care must integrate the benefits, costs and side effects of treatment with patients’ preferences and goals of care. The provision of high-quality care through effective communication with patients and their caregivers is essential, and should include patient–provider communication around goal setting.

While it is possible for clinicians to assess individual-level goals for RA care during the medical encounter, it is unclear which goals are most important to people with RA across different patient populations and whether clinicians systematically elicit patient goals during visits. Current treatment strategies involve the RA clinical management model Treat to Target (TTT), which is supported by evidence from randomized controlled trials as a way to achieve better clinical outcomes as compared with usual care (Fransen, Moens, Speyer, & van Riel, 2005; Grigor et al., 2004; Symmons, 2005; Verstappen et al., 2007). TTT is a ‘treatment strategy in which the clinician treats the patient aggressively enough to reach and maintain explicitly specified and sequentially measured goals, such as remission or low disease activity’ (Solomon et al., 2014). While the ‘target‘ of low disease activity is an unquestionably important clinical goal, patients may have other clinical and nonclinical goals and preferences that must be considered when delivering RA care and developing treatment plans. A shared understanding that involves assessments of disease activity, treatment strategies and individual goals may promote better alignment between patients and clinicians, and lead to higher decision quality and medication adherence, and improved health outcomes (Bodenheimer & Handley, 2009; Heisler et al., 2003).

The objective of the present study was to review the existing literature on the needs, goals and expectations of RA patients in order better to guide a systematic elicitation of goals that matter to patients. As the extant literature in this area is largely qualitative, the present paper reports the results of a narrative analysis through a synthesis of recurring themes and identification of current gaps in knowledge. The potential implications for the treatment of RA, patient engagement strategies and educational interventions are discussed.

2 | METHODS

A search of MEDLINE, PsycINFO and the Cochrane Library between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2015 was performed by an academic librarian using a specialized algorithm to find studies about RA patient goals and expectations for care. The search incorporated the following subject terms: rheumatoid arthritis, goals, health priorities, attitude to health, needs, expectations, activities of daily living, quality of life and treatment outcome. Search results were limited to papers in the English language and adult patient populations. The titles and abstracts of papers were retrieved and screened manually by investigators. The inclusion criteria for the papers were empirical investigations, quantitative or qualitative, involving assessments of the needs, goals and expectations of adult patients with RA.

Investigators utilized inductive methods drawn from grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014; Glaser & Strauss, 2009) to analyse the studies identified in our search. Following the general principles of interpretative qualitative data analysis, investigators first screened selected articles and reflected on them by taking notes on their observations of article content in a process called ‘memoing’ (Bernard, 2011). Investigators then utilized these memos during a process of open coding, in which codes were assigned to sections of text deemed to be meaningful and relevant to the objectives of the literature review. Using a preliminary coding schema developed from the open coding process, investigators inductively analysed data in ways that facilitated the emergent themes and then constructed a conceptual rendering of relationships between themes. As an additional form of data analysis, a member of the research team extracted goals from the included studies and systematically organized these goals into a spreadsheet.

In order to ensure trustworthiness, or achievement of high credibility and objectivity, two of the authors, with different backgrounds, examined the data independently. The lead author EH holds an MA in anthropology and specializes in medical anthropology and qualitative research methods, while JB is a practising rheumatologist and health services researcher. While these authors have different backgrounds, agreement on primary themes was reached. In addition, group meetings with three of the authors were held in order to achieve consensus on conceptualized themes and to also further refine thematic categories.

3 | RESULTS

A total of 909 titles were retrieved from MEDLINE. Searches of PsycINFO and the Cochrane Library did not produce any relevant articles. Investigators excluded 871 articles after reviewing titles and abstracts. Of the remaining 38 papers read in full, 16 were excluded (Figure 1). A total of 22 papers met the final inclusion criteria (Table 1). In 11 of these, the identification of patient goals for RA care was the primary scope. The methodological approaches of the studies varied and included qualitative (N = 12), quantitative (N = 9) and mixed methods (N = 1) designs.

FIGURE 1.

Literature review flow diagram

TABLE 1.

Domain-categorized rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patient individual goals (n = 481)

| The bodily experience of RA n = 161 |

Achieving normalcy and wellness maintenance n = 134 |

Social connectedness and support n = 33 |

Interpersonal and systemic healthcare interactions n = 153 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintain/improve function (31) | Self-efficacy (31) | Social support (13) | Patient-centred care (27) |

| General disease improvement (18) | Normalcy (25) | Social connection (9) | RA patient education improvement (26) |

| Pain improvement (18) | General well-being (20) | Awareness of RA (6) | Access to rheumatology care (18) |

| Energy improvement (17) | Employment (18) | RA peer support (5) | Sensitive care delivery (18) |

| Stay mobile (16) | Freedom (16) | Access to support services (14) | |

| Decrease medication side effects (9) | Improved mood (12) | Effective communication (13) | |

| Prevent progression (9) | Home life (9) | Good relationship with provider (10) | |

| Swelling improvement (8) | Reduce stress (3) | Early RA care improvement (8) | |

| Reduction in medication (7) | Care coordination improvement (7) | ||

| Stiffness Improvement (6) | Trust in provider (6) | ||

| Improve treatment (6) | Access to primary care (2) | ||

| Improvement in physical appearance (4) | Cost effective treatment (2) | ||

| Medication efficacy (4) | Equity in RA treatment access (2) | ||

| Sex and intimacy (3) | |||

| Fine motor skills improvement (2) | |||

| General health maintenance (2) | |||

| Remission (1) |

Across the 22 reviewed studies, a total of 481 individual goals were identified (Table 2). Our analysis identified four major thematic domains: (a) the bodily experience of rheumatoid arthritis; (b) achieving normalcy and maintaining wellness; (c) social connectedness and support; and (d) healthcare interactions. It should be noted that these themes are not discrete categories as there is overlap among these groupings. However, viewing patient goals in thematic categories provides a useful framework for better understanding the complexity of the RA care experience.

TABLE 2.

Methodological approaches of studies on rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patient goals involving RA treatment

| Citation | Setting | Sample | Mean disease duration, years |

Data collection methods |

Analytic strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahlmen et al., 2005 | 4 Swedish academically affiliated rheumatology clinics |

25 RA patients | 14 (range: 3–44) | 4 focus groups; recording and transcription |

Inductive thematic analysis |

| Bergsten et al., 2011 | Swedish rheumatology hospital |

16 RA patients, | 14 (range: 2–42) | Exploratory interviews |

Grounded theory |

| Bernatsky et al., 2010 | Canadian regional public health system w./academic affiliation |

18 RA patients; 13 family physicians; 14 rheumatologists; 14 therapists; 9 decision makers; 4 nurses |

15 focus groups | Qualitative content analysis |

|

| Buitinga et al., 2012 | Dutch hospital outpatient rheumatology clinic |

16 RA patients | 12.9a (range: 1–39) |

3 focus groups; semi-structured guide; recording and transcription |

Qualitative coding according to ICF domains |

| Carr et al., 2003 | 5 British clinical centres in urban areas |

39 RA patients | 12a (range: 2–26) |

5 focus groups | Interpretative phenomenological analysis |

| Funahashi & Matsubara, 2012 | Japanese outpatient rheumatology clinic |

165 RA patients, treated with DMARDS |

Survey using measures designed to assess expectations and satisfaction with treatment |

Frequency calculation and chi-square test |

|

| Heiberg & Kvien, 2002 | Norwegian county-based patient register |

1,024 RA patients | 12.7 (SD 11.1) | Survey using measures from Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales 2, Modified Health Assessment Questionnaire and visual analogue scale for pain and fatigue |

Distribution calculations; 2-sample t-tests; chi-square tests; logistic regression analyses |

| Hewlett et al., 2005 | 3 British rheumatology centres in urban areas |

323 RA patients | 13.7 (SD 11.1) | Survey with ranking questions |

Factor analysis |

| Hofmann et al., 2015 | Outpatient clinic in South-East England |

1st phase: 17 RA patients; 2nd phase: 22 RA patients |

Phase 1 sample: 11 (range: 3–44); phase 2 sample: N/A |

1st phase: 3 focus groups; 2nd phase: qualitative feedback on draft questionnaire |

Thematic content analysis |

| Ishikawa et al., 2006 | Japanese rheumatology clinic, academic affiliation in urban area |

115 RA patients | 13.3 (SD 9.4) | Questionnaire completed post-clinical encounter |

Regression analyses |

| Jacobi et al., 2004 | Dutch tertiary and secondary outpatient rheumatology clinics register |

683 RA patients | 10.7 (range: 1.5–57.8) |

Survey with ranking questions (quote-questionnaire method) |

Regression analyses |

| Kristiansen et al., 2012a | 2 Danish hospitals | 11 RA patients | 5.9 (range: 0.2–27) |

2 focus groups | Qualitative content analysis |

| Kristiansen et al., 2012b | 2 Danish hospital outpatient clinics |

32 RA patients purposively sampled |

5.9 (range: 0.27–27) |

6 focus groups | Qualitative content analysis |

| Radford et al., 2008 | British rheumatology nurse specialist clinic |

11 RA patients, purposively sampled |

11.1a (range: 0.4–30) |

2 focus groups | Qualitative content analysis |

| Robinson & Walker, 2012 | British National Health Service outpatient departments |

100 RA patients | 15.6 (range: 1–38) |

Structured interviews | Descriptive statistics |

| Salt & Peden, 2011 | US rheumatology clinic, academic affiliation |

30 female RA patients, purposively sampled |

Semi-structured interviews |

Grounded theory | |

| Sanderson et al., 2010a | Outpatient department at academically affiliated British hospital |

23 RA patients | 17.7 (range: 3–40) |

In-depth interviews | Grounded theory |

| Sanderson et al., 2010b | 3 British outpatient rheumatology departments; British database of anti- tumour necrosis factor therapy patients; British psychological support database; British national RA foundation membership registry |

1st phase: 26 RA patients, purposively sampled; 2nd phase: 254 RA patients |

1st phase: 5 nominal groups with discussion 2nd phase: mailed surveys |

1st phase: qualitative analysis 2nd phase: Cronbach’s alpha coefficient calculation; principal component analysis; chi-square tests |

|

| ten Klooster et al., 2007 | Dutch register of RA patients on a specific therapy |

173 RA patients | 9.9 95% CI | Survey assessment of health status with the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales 2 at baseline, and 3 and 12 months |

Descriptive statistics; paired 2-tailed t-tests with Bonferroni correction; McNemar’s tests |

| van Tuyl et al., 2015 | British medical centre; Dutch medical centre; Austrian medical centre |

47 RA patients | 8, 9b (range:1– 40) |

9 focus groups | Inductive thematic analysis |

| Ward et al., 2007 | Outpatient department at a British teaching hospital |

25 RA patients | 13 (range: 2–32) | Structured interviews | Atheoretical content analysis |

| Wen et al., 2012 | 4 Chinese medical centres; 1 Japanese medical centre; 1 US medical centre |

270 RA patients; 111 physicians |

Comparison of listed clinic visit priorities among RA patients and physicians |

Descriptive statistics; KJ-method analysis of free descriptions; analyses of agreement |

Calculated by A.S. from published data.

A mean of 8 years was reported in Table 1, a mean of 9 years was cited in the text.

CI, confidence interval; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; ICF, International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health; SD, standard deviation.

3.1 | The bodily experience of rheumatoid arthritis

The physical symptomology of RA was identified as a theme in which patients reported specific goals related to general disease improvement and minimization of RA symptoms. Broad goals in this domain included functionality (N = 13), pain reduction (N = 12), lessening of joint swelling and stiffness (N = 8), increased energy levels (N = 7) and mitigating the undesired impacts of medications (N = 6). Less often mentioned was the prevention of further progression of RA damage (N = 5) and concerns related to sexuality and reproduction (N = 2). Examples of specific functionality goals included improvements in grip force (Ahlmen et al., 2005), muscle strength (Ahlmen et al., 2005; van Tuyl et al., 2015), arm function (Heiberg & Kvien, 2002; ten Klooster, Veehof, Taal, van Riel, & van de Laar, 2007), bending (Heiberg & Kvien, 2002; ten Klooster et al., 2007), engagement in physical activities (Funahashi & Matsubara, 2012; Salt & Peden, 2011; Sanderson, Morris, Calnan, Richards, & Hewlett, 2010a) and mobility (Ahlmen et al., 2005; Buitinga, Braakman-Jansen, Taal, & Laar, 2012; Carr et al., 2003; Heiberg & Kvien, 2002; Robinson & Walker, 2012; Salt & Peden, 2011; Sanderson et al., 2010a; Sanderson, Morris, Calnan, Richards, & Hewlett, 2010b; ten Klooster et al., 2007). The results indicated that pain-related treatment goals among RA patients involved the elimination (Funahashi & Matsubara, 2012) or reduction of pain to manageable levels (Heiberg & Kvien, 2002; Hofmann et al., 2015; Salt & Peden, 2011; Sanderson et al., 2010a, 2010b; ten Klooster et al., 2007; Wen et al., 2012). A decrease in fatigue (Ahlmen et al., 2005; Buitinga et al., 2012; Carr et al., 2003; Funahashi & Matsubara, 2012; Hewlett et al., 2005; Sanderson et al., 2010a, 2010b), finding ways to avoid worsening fatigue (Buitinga et al., 2012; Carr et al., 2003) and desire for an improvement in energy levels (Sanderson et al., 2010a, 2010b; Salt & Peden, 2011) were also described. RA patients reported expectations for pharmacological treatment that involved decreased side effects (Buitinga et al., 2012; Carr et al., 2003; Hewlett et al., 2005; Kristiansen, Primdahl, Antoft, & Hørslev-Petersen, 2012a; Salt & Peden, 2011; Sanderson et al., 2010b) and ensured efficacy (Carr et al., 2003; Hofmann et al., 2015; Salt & Peden, 2011). Interestingly, despite the emphasis on remission found in TTT recommendations, remission was only explicitly identified as a treatment goal by RA patients in one study (Wen et al., 2012). However, patient goals included concepts reflecting a desire for disease remission, including absence (van Tuyl et al., 2015) or reduction of symptoms (Ahlmen et al., 2005; Bergsten, Bergman, Fridlund, & Arvidsson, 2011; Carr et al., 2003), and decreased intensity of flares (Sanderson et al., 2010a, 2010b).

Subjective conceptions of the self were also linked to the physical manifestations of RA. Results from the study by Salt and Peden (2011) indicated the importance of feeling good about one’s physical appearance. Similarly, researchers documented the importance of having a positive body image (Hewlett et al., 2005) and not feeling embarrassed about the visible manifestations of RA (Hofmann et al., 2015; Sanderson et al., 2010b).

3.2 | Achieving normalcy and maintaining wellness

Maintaining wellness and achieving a sense of normalcy despite the presence of chronic illness emerged as an important goal of RA treatment among patients. Within this domain, we identified freedom (N = 10), normalcy (N = 9), general well-being (N = 9), self-efficacy (N = 9) and mood improvement (N = 4) as broad goals. Specific treatment goals related to freedom, included increasing (Bergsten et al., 2011; Carr et al., 2003; Sanderson et al., 2010a, 2010b) or maintaining (Hewlett et al., 2005; Hofmann et al., 2015; Salt & Peden, 2011; van Tuyl et al., 2015) independence, and avoiding dependence on medications (Buitinga et al., 2012; Ward et al., 2007) or other people (Buitinga et al., 2012; Carr et al., 2003). Patients reported preferences for treatment outcomes that involved finding ways to live normally (Ahlmen et al., 2005; Carr et al., 2003; Hewlett et al., 2005; Hofmann et al., 2015; Kristiansen, Primdahl, Antoft, & Hørslev-Petersen, 2012b; Sanderson et al., 2010a, 2010b, van Tuyl et al., 2015), to be perceived by others as normal (Ahlmen et al., 2005; Kristiansen et al., 2012b) and to ‘forget’ about (Carr et al., 2003; Sanderson et al., 2010a) or minimize the focus on (Sanderson et al., 2010b) having RA.

Getting enjoyment out of life (Ahlmen et al., 2005; Buitinga et al., 2012; Hewlett et al., 2005, Sanderson et al., 2010a, 2010b) while feeling well (Carr et al., 2003; Hewlett et al., 2005; Hofmann et al., 2015; Sanderson et al., 2010a, 2010b) and working to improve overall quality of life (Funahashi & Matsubara, 2012; Sanderson et al., 2010a, 2010b) were deemed important. Confidence (Ahlmen et al., 2005; Bergsten et al., 2011; Sanderson et al., 2010b), acceptance (Bergsten et al., 2011; Buitinga et al., 2012; Hofmann et al., 2015; Salt & Peden, 2011) and motivation (Sanderson et al., 2010a, 2010b) influenced perceptions of self-efficacy. Moreover, finding meaning in the illness experience (Bergsten et al., 2011; Buitinga et al., 2012), feelings of control (Ahlmen et al., 2005; Buitinga et al., 2012; Hewlett et al., 2005; Hofmann et al., 2015; Sanderson et al., 2010a, 2010b; Ward et al., 2007) and the ability to ‘do the things you want to do’ were identified as important capabilities (Sanderson et al., 2010a, 2010b). Lastly, RA patients reported that developing emotional coping skills (Hofmann et al., 2015; Sanderson et al., 2010b), improving mood (Heiberg & Kvien, 2002; Sanderson et al., 2010a, 2010b; ten Klooster et al., 2007), reducing stress (Heiberg & Kvien, 2002; Sanderson et al., 2010a, 2010b; ten Klooster et al., 2007) and addressing depression (Sanderson et al., 2010a, 2010b; Wen et al., 2012) were treatment priorities.

The physical and psychosocial impact of RA shapes an individual’s ability to adapt and perform the functional activities of everyday life. Our analysis of the literature revealed that RA patients wanted support in achieving goals related to their work (N = 12) and home lives (N = 5). They identified returning to or maintaining employment (Hofmann et al., 2015; Kristiansen et al., 2012a, 2012b; Ward et al., 2007; Wen et al., 2012), workplace support (Kristiansen et al., 2012b) and fulfilling work expectations (Ahlmen et al., 2005; Funahashi & Matsubara, 2012; Heiberg & Kvien, 2002; Hewlett et al., 2005; Kristiansen et al., 2012a; Robinson & Walker, 2012; Sanderson et al., 2010a, 2010b) as important considerations in the identification of treatment priorities. In addition, they deemed the ability to complete household tasks (Heiberg & Kvien, 2002; ten Klooster et al., 2007) and to maintain the same role within the household (Hewlett et al., 2005; Robinson & Walker, 2012) as important. Participation in work in and outside of the home is integral to the way people build a sense of identity (Beech, 2008) and, given the overarching impact of RA on a person’s everyday life, it is important to consider their work and domestic lives in developing treatment goals.

3.3 | Social connectedness and support

Results from the literature indicated that social support (N = 8) and social connections (N = 6) are important outcomes to RA patients. Examples of social support include psychosocial care (Ahlmen et al., 2005; Bergsten et al., 2011) positive encouragement (Wen et al., 2012) and help from family and friends in the completion of daily tasks (Bergsten et al., 2011). These patients also indicated a need for increased family support (Bergsten et al., 2011; Heiberg & Kvien, 2002; Radford et al., 2008; ten Klooster et al., 2007) and adequate levels of social support in general (Bergsten et al., 2011; Hofmann et al., 2015; Kristiansen et al., 2012a). They reported preferences for treatment outcomes that facilitated improved social connectedness through participation in social activities (Heiberg & Kvien, 2002; Hewlett et al., 2005; ten Klooster et al., 2007), management of social roles and expectations (Ahlmen et al., 2005; Kristiansen et al., 2012a) and the development of new interests and relationships (Sanderson et al., 2010b).

While RA patients viewed interactions with family members, friends and communities as important to their well-being, some pointed to a problematic a gap in the knowledge of RA in the general population (N = 6). These patients articulated a desire for increased awareness of RA in the community (Bernatsky et al., 2010; Hofmann et al., 2015; Ward et al., 2007) as well as to be recognized by others as experts on living with RA (Ahlmen et al., 2005). This is also true of RA patients’ interactions with the healthcare system and the people within the system delivering medical care.

3.4 | Interpersonal and healthcare system interactions

Given that RA is a chronic disease requiring intensive self and clinical management, RA patients often have frequent interactions with the healthcare system. Results from the literature point to the salience of contact with clinicians, nurses and the wider system in the lives of people with RA. Our analysis of this theme revealed that these patients identify preferences for positive dealings with the healthcare system that involve effective patient–provider communication (N = 10), availability of support services (N = 8), access to rheumatologists (N = 7), RA education (N = 7), patient-centred care (N = 7), sensitive healthcare delivery (N = 6) and care coordination (N = 5). Less often mentioned, but important to a number of RA patients, were primary care access (N = 2), cost-effective RA care (N = 2) and trust in healthcare providers (N = 2). Effective patient–provider communication was conceptualized by RA patients as active listening on behalf of the provider (Carr et al., 2003; Salt & Peden, 2011), reviewing current disease status (Kristiansen et al., 2012a; Ward et al., 2007; Wen et al., 2012), discussing complications (Wen et al., 2012), addressing medication efficacy (Kristiansen et al., 2012a; Radford et al., 2008; Wen et al., 2012) and ensuring the provision of clinic visiting time for answering questions (Salt & Peden, 2011) and provider feedback (Bergsten et al., 2011). Many RA patients prioritized support services such as social work (Kristiansen et al., 2012b), mental health services (Hofmann et al., 2015; Radford et al., 2008) and physical therapy in treatment (Ahlmen et al., 2005; Bergsten et al., 2011). These patients indicated the importance of having access to specialty rheumatology care (Ahlmen et al., 2005; Bergsten et al., 2011; Buitinga et al., 2012; Carr et al., 2003; Salt & Peden, 2011; Sanderson et al., 2010b; Wen et al., 2012) and RA education for themselves and their families (Bernatsky et al., 2010; Jacobi et al., 2004; Kristiansen et al., 2012b; Hofmann et al., 2015; Radford et al., 2008; Salt & Peden, 2011; Ward et al., 2007; Wen et al., 2012) for the achievement of treatment goals. Next, RA patients emphasized that patient-centred care involving patient-directed decision making (Bergsten et al., 2011; Carr et al., 2003; Hofmann et al., 2015; Ishikawa, Hashimoto, & Yano, 2006; Jacobi et al., 2004; Kristiansen et al., 2012b; Salt & Peden, 2011: Ward et al., 2007) and sensitive healthcare delivery characterized by empathy (Bergsten et al., 2011; Ishikawa et al., 2006; Radford et al., 2008; Salt & Peden, 2011), mutual respect (Kristiansen et al., 2012a; Salt & Peden, 2011) and kindness (Jacobi et al., 2004; Salt & Peden, 2011) were important treatment priorities. Lastly, RA patients articulated that priority for effective care coordination among different healthcare personnel (Bernatsky et al., 2010; Jacobi et al., 2004; Radford et al., 2008; Sanderson et al., 2010b), improved access to primary care services (Bernatsky et al., 2010; Carr et al., 2003), knowledge of the costs associated with treatments (Jacobi et al., 2004; Wen et al., 2012) and trust in providers’ capabilities (Jacobi et al., 2004; Kristiansen et al., 2012a; Salt & Peden, 2011; Ward et al., 2007).

4 | DISCUSSION

In the present review, we identified 453 individual goals organized into 42 broad groupings, which in turn fell into four major themes: (a) the bodily experience of RA; (b) achieving normalcy and wellness maintenance; (c) social connectedness and support; and (d) interpersonal and healthcare system interactions. Our analysis indicated that existential givens, such as agency, responsibility, connection, meaning and emotion, influence the ways that people experience RA. Moreover, living with RA is multidimensional and involves issues that extend beyond clinical needs, and patients must leverage social connections and supports in order to navigate the physical and existential experience of chronic illness. In addition, subjective conceptions of the self are interrelated with the everyday experience of managing a chronic disease like RA.

The findings of the present study are broadly consistent with those of the prior literature on goal setting in the context of patient-centred care in chronic disease treatment. Patient-centred care and goal setting are associated with improved outcomes in chronic disease (Heisler et al., 2003), in ways that enhance patient satisfaction, quality of care and health outcomes, and decrease health costs and health disparities (Epstein, Fiscella, Lesser, & Stange, 2010). Studies in primary care settings have shown that patients with clearly defined health goals demonstrate more effective self-management behaviours (Brownell & Cohen, 1995; Levetan et al., 2005; Yates, Davies, Gorely, Bull, & Khunti, 2009) and that a collaborative style of patient engagement in the development of treatment goals increases patient understanding and motivation to follow treatment plans (Heisler et al., 2003; Bodenheimer & Handley, 2009). In the context of diabetes care, which is similar to that of RA, in that it is a chronic condition that requires intensive self-management, patient–provider agreement on treatment strategies is associated with higher patient self-efficacy and self-management (Heisler et al., 2003). This evidence supports the importance of a strong patient–provider relationship characterized by effective communication and trust. An intersubjective understanding of a health condition and associated treatment strategies is essential for fostering a trusting patient–provider relationship that facilitates the delivery of high-quality care (Saba et al., 2006). The identification of care goals deemed to be important by the patient is an essential first step in fostering a patient–provider relationship characterized by trust and shared experience.

There were limitations to the current review. First, the data were derived from predominantly qualitative studies, and the quality of data collection was difficult to judge. Second, the studies did not allow for an analysis of goals by individual patient characteristics (e.g. ethnicity, age, gender, socioeconomic status, disease severity) that might influence care priorities. Lastly, it was difficult to determine from the studies, which were mostly qualitative, the relative weight that patients place on each goal or group of goals; however, it seemed that physical symptomology was more of a focus among RA patients who were experiencing the earlier stages of RA than for those in the later stages.

Communication around goals in RA has as yet been largely unexplored. However, explorations and identification of RA goals are in line with national directives for patient-centred care (Smolen et al., 2010). Guidelines for RA treatment found in the National Health Service’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend that a ‘negotiated position’ be reached by patients and clinicians on treatment goals as true remission may not always be achievable (Watts, 2010). While clinicians have clear directives regarding goals of therapy for RA, it is unknown if these disease activity-centric goals align with patient goals. To promote truly patient-centred care for RA patients, it is imperative to assess and integrate patient goals into treatment plans in a systematic way.

The present study highlighted four domains from the literature into which patient goals for RA care may fall. This taxonomy can now be utilized by clinicians caring for patients with RA. Initial goals for care can be elicited by clinicians and guided by these domains to ensure that the patient voice is heard and addressed in care decisions made jointly. The domains identified in the present review can be used to populate a tablet- or paper-based tool to elicit patient goals for RA care prior to visits with rheumatology clinicians, and then discussed together and used to inform and support shared decision making. Future research on how to improve patient-centred care in RA can include the development and testing of tools designed to elicit patient goals, incorporate them into existing decision aids and improve goal concordance between patients and clinicians.

For RA patients who must contend with the reality of living with chronic disease, there may be significant challenges in their ability to integrate clinicians’ recommendations while also dealing with work, family or social obligations and coping with the physical symptoms of the condition. In order to avoid undue burden of RA treatment, goals must be developed collaboratively and the RA illness experience should be evaluated by the clinician and patient in the context of the patient’s life situation (May, Montori, & Mair, 2009). Future research should involve incorporating knowledge of patient preferences for RA care into the development of a tool designed to elicit RA patient goals. Such a tool may work to improve communication around goal setting and support patient–clinician collaboration in the context of patient-centred RA care.

Acknowledgments

The current work is part of a larger study, ‘Goal Concordance in Rheumatoid Arthritis in Diverse Populations’, approved by the Joint Institutional Review Board at the VA Portland Health Care System and Oregon Health and Science University. Support for this research was provided by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health grant K23-AR-064372. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of the facilities at the Center to Improve Veteran Involvement in Care, VA Portland Health Care System.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Ahlmen M, Nordenskiold U, Archenholtz B, Thyberg I, Ronnqvist R, Linden L, Mannerkorpi K. Rheumatology outcomes: The patient’s perspective. A multicentre focus group interview study of Swedish rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2005;44(1):105–110. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech N. On the nature of dialogic identity work. Organization. 2008;15(1):51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bergsten U, Bergman S, Fridlund B, Arvidsson B. ‘Striving for a good Life’ – The management of rheumatoid arthritis as experienced by patients. Open Nursing Journal. 2011;5(1):95–101. doi: 10.2174/1874434601105010095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HR. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman Altamira; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bernatsky S, Feldman D, De Civita M, Haggerty J, Tousignant P, Legaré J, Roper M. Optimal care for rheumatoid arthritis: A focus group study. Clinical Rheumatology. 2010;29(6):645–657. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum H, Pike C, Kaufman R, Maynchenko M, Kidolezi Y, Cifaldi M. Societal cost of rheumatoid arthritis patients in the US. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2010;26(1):77–90. doi: 10.1185/03007990903422307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Handley MA. Goal-setting for behavior change in primary care: An exploration and status report. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;76(2):174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell KD, Cohen LR. Adherence to dietary regimens 1: An overview of research. Behavioral Medicine. 1995;20(4):149–154. doi: 10.1080/08964289.1995.9933731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buitinga L, Braakman-Jansen L, Taal E, Laar MA. Future expectations and worst-case future scenarios of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A focus group study. Musculoskeletal Care. 2012;10(4):240–247. doi: 10.1002/msc.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr A, Hewlett S, Hughes R, Mitchell H, Ryan S, Carr M, Kirwan J. Rheumatology outcomes: The patient’s perspective. Journal of Rheumatology. 2003;30(4):880–883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, Stange KC. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2010;29(8):1489–1495. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransen J, Moens HB, Speyer I, van Riel PL. Effectiveness of systematic monitoring of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity in daily practice: A multicentre, cluster randomised controlled trial. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2005;64(9):1294–1298. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.030924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funahashi K, Matsubara T. What RA patients expect of their – Treatment discussion over the result of our survey. Clinical Rheumatology. 2012;31(11):1559–1566. doi: 10.1007/s10067-012-2048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Piscataway, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Grigor C, Capell H, Stirling A, McMahon AD, Lock P, Vallance R, Kincaid W. Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): A single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9430):263–269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16676-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiberg T, Kvien TK. Preferences for improved health examined in 1,024 patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Pain has highest priority. Arthritis Care & Research. 2002;47(4):391–397. doi: 10.1002/art.10515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler M, Vijan S, Anderson RM, Ubel PA, Bernstein SJ, Hofer TP. When do patients and their physicians agree on diabetes treatment goals and strategies, and what difference does it make? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18(11):893–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewlett S, Carr M, Ryan S, Kirwan J, Richards P, Carr A, Hughes R. Outcomes generated by patients with rheumatoid arthritis: How important are they? Musculoskeletal Care. 2005;3(3):131–142. doi: 10.1002/msc.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann D, Ibrahim F, Rose D, Scott DL, Cope A, Wykes T, Lempp H. Expectations of new treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: Developing a patient-generated questionnaire. Health Expectations. 2015;18(5):995–1008. doi: 10.1111/hex.12073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa H, Hashimoto H, Yano E. Patients’ preferences for decision making and the feeling of being understood in the medical encounter among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research. 2006;55(6):878–883. doi: 10.1002/art.22355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi C, Boshuizen HC, Rupp I, Dinant H, Van Den Bos GAM. Quality of rheumatoid arthritis care: The patient’s perspective. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2004;16(1):73–81. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen TM, Primdahl J, Antoft R, Hørslev-Petersen K. It means everything: Continuing normality of everyday life for people with rheumatoid arthritis in early remission. Musculoskeletal Care. 2012a;10(3):162–170. doi: 10.1002/msc.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen TM, Primdahl J, Antoft R, Hørslev-Petersen K. Everyday life with rheumatoid arthritis and implications for patient education and clinical practice: A focus group study. Musculoskeletal Care. 2012b;10(1):29–38. doi: 10.1002/msc.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levetan CS, Dawn KR, Murray JF, Popma JJ, Ratner RE, Robbins DC. Impact of Computer-generated personalized goals on cholesterol lowering. Value in Health. 2005;8(6):639–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.00057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May C, Montori VM, Mair FS. We need minimally disruptive medicine. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 2009;339:b2803. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford S, Carr M, Hehir M, Davis B, Robertson L, Cockshott Z, Hewlett S. ‘It’s quite hard to grasp the enormity of it’: Perceived needs of people upon diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Musculoskeletal Care. 2008;6(3):155–167. doi: 10.1002/msc.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SM, Walker DJ. Negotiating targets with patients: Choice of target in relation to occupational state. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2012;51(2):293–296. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saba GW, Wong ST, Schillinger D, Fernandez A, Somkin CP, Wilson CC, Grumbach K. Shared decision making and the experience of partnership in primary care. Annals of Family Medicine. 2006;4(1):54–62. doi: 10.1370/afm.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salt E, Peden A. The complexity of the treatment: The decision-making process among women with rheumatoid arthritis. Qualitative Health Research. 2011;21(2):214–222. doi: 10.1177/1049732310381086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson T, Morris M, Calnan M, Richards P, Hewlett S. What outcomes from pharmacologic treatments are important to people with rheumatoid arthritis? Creating the basis of a patient core set. Arthritis Care & Research. 2010a;62(5):640–646. doi: 10.1002/acr.20034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson T, Morris M, Calnan M, Richards P, Hewlett S. Patient perspective of measuring treatment efficacy: The rheumatoid arthritis patient priorities for pharmacologic interventions outcomes. Arthritis Care & Research. 2010b;62(5):647–656. doi: 10.1002/acr.20151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, Breedveld FC, Boumpas D, Burmester G T2T Expert Committee. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: Recommendations of an international task force. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2010;69(4):631–637. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.123919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon DH, Bitton A, Katz JN, Radner H, Brown EM, Fraenkel L. Review: Treat to target in rheumatoid arthritis: Fact, fiction, or hypothesis? Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2014;66(4):775–782. doi: 10.1002/art.38323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symmons D, Tricker K, Roberts C, Davies L, Dawes P, Scott DL. The British Rheumatoid Outcome Study Group (BROSG) randomised controlled trial to compare the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of aggressive versus symptomatic therapy in established rheumatoid arthritis. Health Technology Assessment. 2005;9:34. doi: 10.3310/hta9340. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3310/hta9340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Klooster PM, Veehof MM, Taal E, van Riel PL, van de Laar MA. Changes in priorities for improvement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis during 1 year of anti-tumour necrosis factor treatment. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2007;66(11):1485–1490. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.069765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tuyl LH, Hewlett S, Sadlonova M, Davis B, Flurey C, Hoogland W, Boers M. The patient perspective on remission in rheumatoid arthritis: ‘You’ve got limits, but you’re back to being you again’. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2015;74(6):1004–1010. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstappen SM, Jacobs JW, van der Veen MJ, Heurkens AH, Schenk Y, ter Borg EJ Utrecht Rheumatoid Arthritis Cohort study group. Intensive treatment with methotrexate in early rheumatoid arthritis: Aiming for remission. computer assisted management in early rheumatoid arthritis (CAMERA, an open-label strategy trial) Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2007;66(11):1443–1449. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.071092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward V, Hill J, Hale C, Bird H, Quinn H, Thorpe R. Patient priorities of care in rheumatology outpatient clinics: A qualitative study. Musculoskeletal Care. 2007;5(4):216–228. doi: 10.1002/msc.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts RA. Rheumatoid arthritis national clinical guideline. Rheumatology. 2010;49(2):399–399. [Google Scholar]

- Wen H, Ralph Schumacher H, Li X, Gu J, Ma L, Wei H, Dinnella J. Comparison of expectations of physicians and patients with rheumatoid arthritis for rheumatology clinic visits: A pilot, multicenter, international study. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 2012;15(4):380–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2012.01752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates T, Davies M, Gorely T, Bull F, Khunti K. Effectiveness of a pragmatic education program designed to promote walking activity in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(8):1404–1410. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]