Abstract

The role of angiogenesis factors in skeletal muscle dysfunction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is unknown. The first objective of this study was to assess various pro- and antiangiogenic factor and receptor expressions in the vastus lateralis muscles of control subjects and COPD patients. Preliminary inquiries revealed that angiopoietin-2 (ANGPT2) is overexpressed in limb muscles of COPD patients. ANGPT2 promotes skeletal satellite cell survival and differentiation. Factors that are involved in regulating muscle ANGPT2 production are unknown. The second objective of this study was to evaluate how oxidants and proinflammatory cytokines influence muscle-derived ANGPT2 expression. Angiogenic gene expressions in human vastus lateralis biopsies were quantified with low-density real-time PCR arrays. ANGPT2 mRNA expressions in cultured skeletal myoblasts were quantified in response to proinflammatory cytokine and H2O2 exposure. Ten proangiogenesis genes, including ANGPT2, were significantly upregulated in the vastus lateralis muscles of COPD patients. ANGPT2 mRNA levels correlated negatively with forced expiratory volume in 1 s and positively with muscle wasting. Immunoblotting confirmed that ANGPT2 protein levels were significantly greater in muscles of COPD patients compared with control subjects. ANGPT2 expression was induced by interferon-γ and -β and by hydrogen peroxide, but not by tumor necrosis factor. We conclude that upregulation of ANGPT2 expression in vastus lateralis muscles of COPD patients is likely due to oxidative stress and represents a positive adaptive response aimed at facilitating myogenesis and angiogenesis.

Keywords: COPD, skeletal muscles, angiogenesis, angiopoietins, myogenesis, cytokines

marked reductions in limb muscle strength and endurance are among the important manifestations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) that contribute to the compromised lifestyles experienced by patients with the disease (27). Morphologically, limb muscles exhibit wasting, shifts in fiber-type distribution that result in an increase of type II fibers, altered mitochondrial enzyme activity, and reduced muscle O2 uptake (5, 19, 20, 24, 25, 46). Skeletal muscle perfusion and O2 uptake are highly dependent on the size of the capillary-fiber interface (22), which, in turn, is regulated by complex interactions between proangiogenesis factors, which promote neovascularization and vascular stability, and angiostatic factors, which inhibit angiogenesis and cause vascular cell apoptosis. In skeletal muscles, proangiogenesis factors include vascular endothelial cell growth factors (VEGFs), fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), platelet-derived growth factors, and angiopoietins (8). Among these factors, only the VEGF family of growth factors has been assessed in terms of expression and localization in skeletal muscles of limb muscles of COPD patients. Significant elevations of VEGFA and VEGFB mRNA levels have been observed in the tibialis anterior muscles of patients with moderate COPD (24). In comparison, relatively low levels of VEGFA protein have been found in the vastus lateralis muscles of patients with severe COPD, compared with control subjects (5). No information is as yet available regarding expression levels of other angiogenic or angiostatic factors in skeletal muscles of COPD patients.

The first objective of this study, therefore, was to assess various angiogenesis factor and receptor expressions in the vastus lateralis muscles of patients with severe COPD and age- and activity-matched control subjects. While performing initial screening, we observed that angiopoietin-2 (ANGPT2) expression was significantly elevated relative to control subjects. ANGPT2 is a member of the angiopoietin family of angiogenesis factors and acts as a ligand for TIE2 receptors (36). ANGPT2 is expressed in the endothelium, tumor cells, macrophages, and muscle cells (21, 28, 30, 36, 40). In endothelial cells, ANGPT2 binds to TIE2 receptors with similar affinity to that of angiopoietin-1 (ANGPT1). However, whereas ANGPT1 is a strong agonist of TIE2 receptors, the ability of ANGPT2 to activate TIE2 receptors is highly dependent on the cell type and context (9).

Investigators have paid considerable attention to identifying those factors that regulate endothelial-derived ANGPT2 expression and how ANGPT2 influences endothelial cell survival and differentiation (17, 32, 43, 44). However, little attention has been paid to identifying the factors that regulate ANGPT2 production in muscle cells or to its functional significance in skeletal muscle. The second objective of our study, therefore, was to assess those factors that may be involved in the regulation of ANGPT2 expression in skeletal muscles of COPD patients. The rationale for selecting ANGPT2 for further analysis is based on our recent findings that ANGPT2 plays a dual role in enhancing skeletal muscle regenerative capacity, by promoting angiogenesis of endothelial cells and by promoting myogenesis of skeletal satellite cells (39). In the present study, we specifically assessed influences of proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and interferon-β (IFN-β), and oxidants, such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), on muscle-derived ANGPT2 expression. Our emphasis on cytokines and oxidants is based on several observations, including the observations that inflammatory mediators are elevated in the plasma and muscles of COPD patients during severe exacerbation of the disease (41, 45), and that oxidative stress develops in the skeletal muscles of these patients, both at rest and following exercise (1, 4, 15).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Three sets of experiments were performed. The study was approved by the ethics review boards of Centre de Recherche, Hôpital Laval, Institut Universitaire de Cardiologie et de Pneumologie de l'Université Laval, Quebec, Canada, and Evangelismos Hospital, University of Athens Medical School, Greece. Informed, written consent was obtained from all subjects.

Experiment 1: Expressions of Angiogenesis-related Factors in the Vastus Lateralis Muscle

Differential expressions of 92 angiogenesis-related genes in the vastus lateralis muscles of control subjects and patients with severe COPD were evaluated using low-density real-time PCR arrays. Sixteen men were recruited (Hôpital Laval, Laval, Quebec, Canada). Of these subjects, eight had severe COPD, and eight had normal lung function (Table 1). COPD diagnosis was established using Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease guidelines (16). Exclusion criteria included chronic respiratory failure, bronchial asthma, coronary artery disease, neuromuscular disease, chronic metabolic disease, and/or treatment with drugs known to alter muscle structure and function. No patient was receiving long-term O2 therapy. All subjects were classified as sedentary according to a physical activity questionnaire adapted for older and retired subjects (10). Needle biopsies of the vastus lateralis muscle were performed at midthigh level, as described by Bergström (7), and tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Table 1.

Characteristics of control subjects and COPD patients that contributed vastus lateralis biopsies subsequently subjected to low-density real-time PCR array analysis for angiogenesis-related gene expression (experiment 1)

| Control | COPD | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 8 | 8 |

| Age, yr | 70.2 ± 1.7 | 68.7 ± 3.6 |

| Men, % | 100 | 100 |

| Height, m | 1.70 ± 0.02 | 1.72 ± 0.02 |

| Weight, kg | 76.9 ± 3.7 | 72.3 ± 5.1 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.5 ± 1.0 | 24.3 ± 1.6 |

| Left thigh CSA, mm2 | 9,536 ± 787 | 8,617 ± 684 |

| FEV1, liters | 2.92 ± 0.21 | 1.34 ± 0.06* |

| FEV1, %predicted | 94.4 ± 4.1 | 42.00 ± 2.5* |

| FVC, liters | 3.90 ± 0.27 | 3.19 ± 0.29* |

| FVC, %predicted | 100.6 ± 4.9 | 79 ± 5.3* |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 74.3 ± 2.0 | 43.4 ± 3.7* |

| V̇o2max, l/min | 1.95 ± 0.11 | 1.46 ± 0.09* |

| Maximum work load, W | 145 ± 8.4 | 111.8 ± 9.2* |

| Smoking history, pack·yr | 9.5 ± 4.4 | 49.2 ± 8.6* |

Values are means ± SE; n, no. of subjects. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BMI, body mass index; CSA, cross-sectional area; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; V̇o2max, maximum O2 consumption.

P < 0.001, compared with control subjects.

Pulmonary function tests and anthropometric measurements.

Spirometry (pre- and postbronchodilation) and phlethysmographic lung volumes, two standard pulmonary function tests, were performed on COPD patients according to previously described guidelines (2) and related to normal values of Knudson et al. (29) and Goldman and Becklake (18), respectively. For control subjects, spirometry alone was performed. Height and weight were measured according to standardized methods.

Computed tomography.

Computed tomography of the right thigh, halfway between the pubic symphisis and the inferior condyle of the femur, was performed prebiopsy to quantify midthigh cross-sectional areas (CSA) (37).

Muscle fiber type and capillary density.

Muscle sections from vastus lateralis biopsies of control subjects and COPD patients were stained for myofibrillar ATPase activity, according to the single-step ethanol-modified technique (35). Muscle fibers were classified according to staining intensity: type I (nonstained); type IIa (slightly stained); and type IIx (darkly stained). Sections were also stained using the α-amylase-periodic acid shift method to visualize capillaries (3). Capillary density of each section was quantified as the number of capillaries per muscle fiber and as the number of capillary contacts per muscle fiber CSA (3). Two indexes of muscle capillarization were quantified: 1) the capillary-to-fiber ratio was obtained by dividing the total number of capillaries by the total number of fibers on 200 randomly selected fibers; and 2) the capillary contact-to-fiber CSA ratio was obtained by dividing the number of capillary contacts for 40 randomly selected fibers of each type by the mean CSA of the corresponding fibers.

Detection of angiogenesis-related gene expression.

Total RNA was extracted from human muscle biopsies using a GenElute Mammalian Total RNA Miniprep Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON). Quantification and purity of total RNA was assessed by A260/A280 absorption. RNA (2 μg) was reverse transcribed using Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase Kits and random primers (Invitrogen Canada, Burlington, ON). Reactions were incubated at 42°C for 50 min and at 90°C for 5 min. mRNA expressions of 92 angiogenesis-related genes and related receptors in the vastus lateralis muscles of eight control subjects and eight COPD patients (Table 1) were measured using TaqMan Human Angiogenesis Gene Signature Low-Density Arrays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) spotted on a microfluidic card (four replicates per assay). Four genes (ADAMTS1, GAPDH, PECAM1, and PGK1) and 18S were used as controls. Each assay consisted of a forward and reverse primer at a final concentration of 900 nM and a TaqMan 6-FAM dye/MGB-labeled probe at 250 nM final concentration. Assays were gene specific and designed to span an exon-exon junction. For each sample (25 ng total input RNA/μl), 100 μl of cDNA were combined with an equal volume of TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, mixed by inversion, and spun briefly in an Eppendorf 5415D microcentrifuge (Brinkmann Instruments, Westbury, NY). After cards reached room temperature, 100 μl of each sample were loaded into each of eight ports on the array. Cards were centrifuged for 1 min at 1,200 rpm. Cards with excess sample in the fill reservoir were spun for an additional 1 min. Immediately following centrifugation, cards were sealed with TaqMan Low-Density Array Sealer to prevent cross-contamination. Final volumes in each well were <1.5 μl, making the final concentration ∼15 ng per reaction. Real-time RT-PCR amplifications were run on an ABI Prism 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). The thermal profile was as follows: 2 min at 50°C (to activate uracil-DNA glycosylase); 10 min at 95°C (activation); 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C (denaturation); and 45 cycles of 1 min at 60°C (annealing and extension). Real-time RT-PCR data were quantified using an SDS 2.2.2 software package (Applied Biosystems). Results from each card were quantified separately using an automatic baseline and a manual threshold of 0.10 to record cycle thresholds (CT). Assays that did not yield a CT of <40 cycles were treated as missing data. Relative quantifications of target genes were determined using the ΔΔCT method according to the following procedures:

- Normalization of CT values per sample: Tthe arithmetic mean CT value of the five endogenous control genes (CT normalization factor) was calculated. Then the ΔCT target gene for a given target gene was calculated as follows:

Averaging control samples: The mean value of the ΔCT target gene of all control subjects (control ΔCT target gene) was then calculated.

Difference from the mean of control subjects: Difference between the ΔCT target gene and control ΔCT target gene (ΔΔCT target gene) for control subjects and COPD patients was then calculated as follows: ΔΔCT target gene = ΔCT target gene − control ΔCT target gene.

- Relative expression: Relative expression (RQ) was calculated formulas follows:

A Student t-test was used to detect differences in RQ values between control subjects and COPD patients. P < 0.05 values were considered significant. Detected genes are listed in Table 1.

Experiment 2: Verification of ANGPT2 Expression in the Vastus Lateralis and Diaphragm Muscles

A second set of experiments was performed on a larger number of control subjects and COPD patients to verify that ANGPT2 levels are indeed elevated in limb muscles of COPD patients compared with control subjects. To assess whether ANGPT2 is also elevated in the respiratory muscles, diaphragm muscle biopsies were assessed. VEGFA mRNA levels were measured because VEGF is the only angiogenesis factor whose expression has been previously investigated in limb muscles of COPD patients. ANGPT1 mRNA levels were measured because of similarities in structure and action between ANGPT1 and ANGPT2. CD31 mRNA levels were measured as a marker of endothelial cells and used to assess whether elevated ANGPT2 mRNA levels might relate to increased endothelial cell abundance. In this experiment, vastus lateralis muscle biopsies were obtained from 14 control subjects (including 8 subjects from experiment 1) and 16 COPD patients (including 8 patients from experiment 2) (see Table 4). Needle biopsies were performed as described above. For the diaphragm cohort, 13 COPD patients (12 men and 1 woman) undergoing thoracotomy due to localized lung neoplasm (10 patients) or bullous lung diseases (3 patients) were recruited (see Table 5). In addition, eight control subjects (all men) with normal pulmonary functions undergoing thoracotomy due to localized lung neoplasm (seven subjects) or bullous lung diseases (one subject) were recruited (see Table 5). Diaphragm muscle biopsies were obtained from the anterior costal diaphragm, lateral to the insertion of the phrenic nerve, and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Table 4.

Characteristics of control subjects and COPD patients that contributed vastus lateralis biopsies subsequently subjected to gene-specific expression assays and immunoblotting (experiment 2)

| Control | COPD | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 16 | 14 |

| Age, yr | 65.4 ± 2.1 | 71.2 ± 3.3 |

| Men, % | 100 | 100 |

| Height, m | 1.70 ± 0.02 | 1.69 ± 0.02 |

| Weight, kg | 79.4 ± 2.7 | 75.8 ± 3.4 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.4 ± 0.9 | 26.4 ± 1.1 |

| Left thigh CSA, mm2 | 9,662 ± 478 | 7,765 ± 387* |

| FEV1, liters | 3.15 ± 0.21 | 1.24 ± 0.09* |

| FEV1, %predicted | 101.7 ± 4.5 | 42.4 ± 3.1* |

| FVC, liters | 4.05 ± 0.23 | 2.73 ± 0.14* |

| FVC, %predicted | 104.2 ± 4.2 | 72.13 ± 3.1* |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 77.6 ± 1.7 | 45.9 ± 1.8* |

| PaO2, Torr | 106.5 ± 4.1 | 67.4 ± 2.2* |

| PaCO2, Torr | 32.1 ± 1.6 | 38.7 ± 2.1* |

| pH | 7.44 ± 0.01 | 7.43 ± 0.01 |

| Smoking history, pack·yr | 8.1 ± 3.2 | 46.8 ± 7.4* |

Values are means ± SE; n, no. of subjects. BMI, body mass index; PaO2, arterial PO2; PaCO2, arterial Pco2.

P < 0.001, compared with control subjects.

Table 5.

Characteristics of control subjects and COPD patients that contributed diaphragm biopsies subjected to gene-specific expression assays and immunoblotting (experiment 2)

| Control | COPD | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 8 | 13 |

| Age, yr | 70.1 ± 2.4 | 65.1 ± 2.7* |

| Men, % | 100 | 100 |

| Height, m | 1.74 ± 0.02 | 1.70 ± 0.02 |

| Weight, kg | 79.5 ± 2.8 | 74 ± 3.2 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.2 ± 1.2 | 25.3 ± 1.0 |

| FEV1, liters | 2.66 ± 0.3 | 1.67 ± 0.08* |

| FEV1, %predicted | 92.3 ± 8.1 | 54.3 ± 2.2* |

| FVC, liters | 3.36 ± 0.30 | 3.0 ± 0.1* |

| FVC, %predicted | 90.1 ± 8.5 | 77.1 ± 2.1* |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 79.8 ± 2.8 | 55.8 ± 2.3* |

| PaO2, Torr | 82 ± 1.7 | 75.4 ± 2.2* |

| PaCO2, Torr | 37.7 ± 1.6 | 39.8 ± 1.1 |

| pH | 7.39 ± 0.01 | 7.40 ± 0.01 |

Values are means ± SE; n, no. of subjects.

P < 0.05, compared with control subjects.

Real-time PCR.

Total RNA extractions from vastus lateralis and diaphragm samples and reverse transcriptions were performed as described in experiment 1. To quantify expressions of ANGPT1, ANGPT2, VEGF, CD31, and 18S (endogenous control), TaqMan Gene Expression Assays specific to these genes were used. Real-time PCR was performed using an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). The thermal profile was as follows: 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 30 s at 57°C, and 33 s at 72°C. All real-time PCR experiments were performed in triplicate. Relative quantifications of human mRNA levels of target genes were determined using the threshold cycle (ΔΔCT) method, as described in experiment 1, except that only one endogenous control gene (18S) was used. A Student t-test was used to detect differences between control subjects and COPD patients. P < 0.05 values were considered significant.

Immunoblotting.

Frozen vastus lateralis muscle biopsies obtained from control subjects and COPD patients were homogenized in six volumes (wt/vol) of homogenization buffer (pH 7.4, 10 mM HEPES buffer, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.32 mM sucrose, and 10 μg/ml each of leupeptin, aprotinin, and pepstatin A). Crude homogenates were centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. Supernatants were collected and used for immunoblotting of ANGPT2 protein. Samples (50 μg total protein) were boiled for 5 min and then loaded onto tris-glycine SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were electrophoretically separated, transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, blocked for 1 h with 5% nonfat dry milk, and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary monoclonal anti-ANGPT2 antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Proteins were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and ECL reagents (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA). Equal loading of protein was confirmed by stripping membranes and reprobing with anti-β-tubulin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). Blots were scanned with an imaging densitometer, and optical densities of protein bands were quantified with ImagePro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Carlsbad, CA). Predetermined molecular weight standards were used as markers. Protein concentrations were measured by the Bradford method, with BSA as a standard.

Experiment 3: Cytokine and Oxidant Regulation of Muscle-derived ANGPT 2 Production

Primary human muscle precursor cells (human myoblasts) were generously provided by Dr. E. Shoubridge (McGill University, Montréal, QC) and cultured in skeletal muscle basal medium (SkBM) supplemented with 15% inactivated fetal bovine serum (34) using a SkBM Bullet Kit (Cambrex, East Rutherford, NJ). Myoblasts were plated into 12-well plates (105 cells/well) and maintained for 24 h in SkBM culture medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum. To evaluate cytokine and H2O2 effects on ANGPT1 and ANGPT2 expressions, cells were stimulated with recombinant human TNF-α (20 ng/ml), IFN-γ (10 ng/ml), IFN-β (25 ng/ml), H2O2 (0.5 mM and 1 mM), or a control solution of phosphate-buffered saline. Cells were collected 24 h later, and ANGPT1 and ANGPT2 mRNA levels were measured using real-time PCR (as above). Relative ANGPT1 and ANGPT2 mRNA levels were determined using the ΔΔCT method. 18S was used as an endogenous control gene.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SE in Figs. 1 and 3. Differences in characteristics of control subjects and COPD patients were detected with Student t-tests, and P < 0.05 values were considered significant. In experiment 2, Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to assess correlations between different variables between control subjects and COPD patients. In experiment 3, for a given intervention (cytokine or H2O2), differences in the expression of ANGPT1 and ANGPT2 were detected using a two-way analysis of variance, followed by a Tukey test. P < 0.05 values were considered significant.

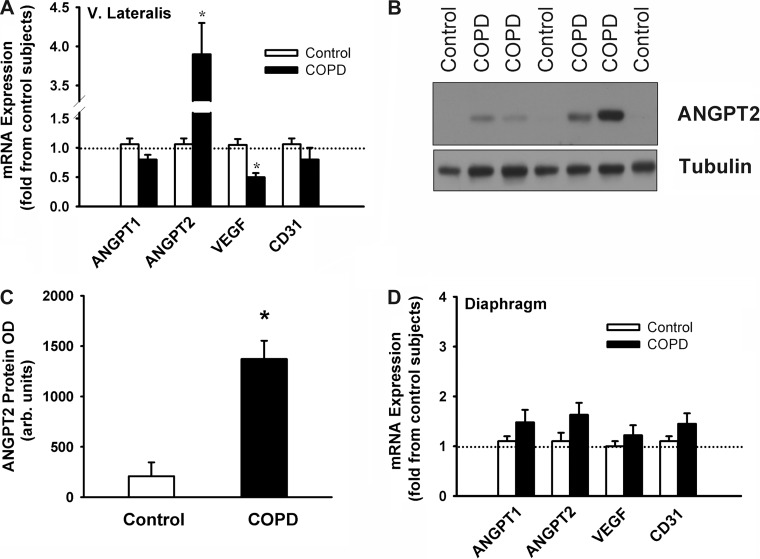

Fig. 1.

A: mRNA expression of angiopoietin-1 (ANGPT1), angiopoietin-2 (ANGPT2), VEGF, and CD31 in vastus lateralis and diaphragm muscles of control subjects and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients (experiment 2). B and C: representative immunoblot of ANGPT2 protein expression (B) and ANGPT2 protein optical densities (OD; C) in vastus lateralis muscles of control subjects and COPD patients (experiment 2). D: mRNA expression of ANGPT1, ANGPT2, VEGF, and CD31 in diaphragm muscles of control subjects and COPD patients (experiment 2). Values are means ± SE, expressed as fold change relative to control subjects. *P < 0.05, compared with control values.

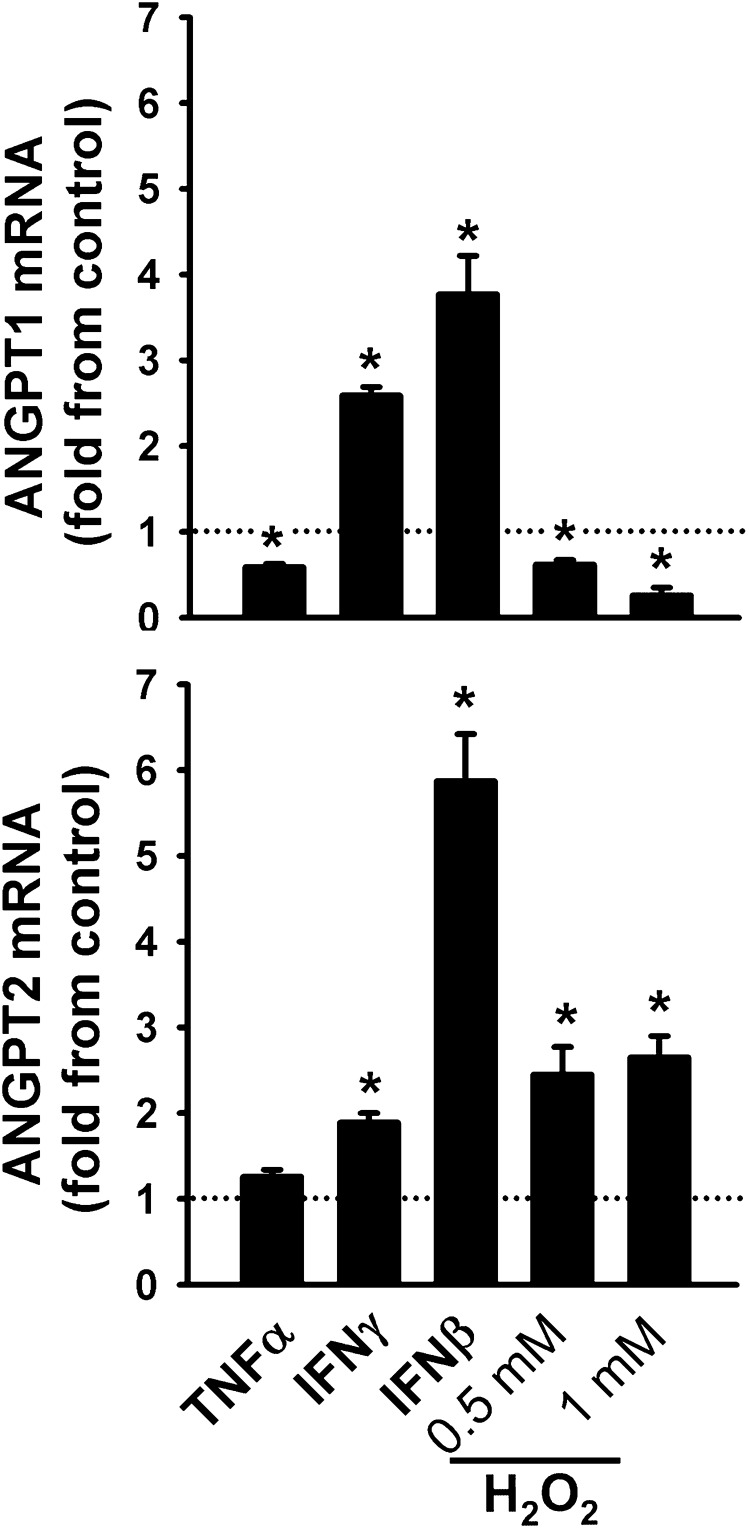

Fig. 3.

ANGPT1 (top) and ANGPT2 (bottom) mRNA expression in human skeletal myoblasts exposed for 24 h to tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and interferon-β (IFN-β), and two concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Values are means ± SE, expressed as fold change relative to PBS-treated cells (control). *P < 0.05, compared with control values. N = 6.

RESULTS

Experiment 1

No significant differences in age, weight, thigh CSA, nutritional status, or capillary density were observed between the eight control subjects and eight COPD patients (Tables 1 and 2). However, forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), FEV1-to-FVC ratios, maximum oxygen consumption, and maximum work load were significantly lower in COPD patients (Table 1). Table 3 shows results of low-density real-time PCR arrays for angiogenesis-related genes in the vastus lateralis muscles of control subjects and COPD patients. Expressions of 10 proangiogenesis genes [angiogenin (ANG), ANGPT2, EGF-like repeats and discoidin I-like domain 3 (EDIL3), ephrin B2 (EPHB2), FGF2, follistatin (FST), FoxC2 (FOXC2), Groβ (CXCL2), prolactin (PRL), and stromal-derived factor 1 (CXCL12)] were significantly higher in the vastus lateralis muscles of COPD patients compared with control subjects, whereas expressions of collagen, type XV, α1 (COL15A1) and the angiogenesis inhibitor troponin I (TNNI1, slow) were significantly lower (Table 3).

Table 2.

Capillarization of vastus lateralis muscle biopsies obtained from subjects and patients included in experiment 1

| Control | COPD | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 8 | 8 |

| Capillary-to-fiber ratio | 3.30 ± 0.27 | 3.40 ± 0.31 |

| No. of capillary contacts | ||

| Type I | 4.2 ± 0.28 | 4.2 ± 0.39 |

| Type IIa | 2.7 ± 0.21 | 2.9 ± 0.35 |

| Type IIx | 2.7 ± 0.35 | 3.4 ± 0.67 |

| Capillary contact/fiber CSA, μm2 | ||

| Type I | 0.70 ± 0.05 | 0.66 ± 0.05 |

| Type IIa | 0.66 ± 0.06 | 0.63 ± 0.06 |

| Type IIx | 0.72 ± 0.04 | 0.72 ± 0.08 |

Values are means ± SE; n, no. of subjects.

Table 3.

List of gene codes, full names, fold change from control, and accession number of angiogenesis-related genes and receptors detected with low density PCR arrays

| Gene Code | Full Name | Fold Change From Control | Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angiopoietins and angiopoietin-like genes | |||

| ANGPT1 | Angiopoietin-1 | 1.33 ± 0.16 | NM_001146 |

| ANGPT2 | Angiopoietin-2 | 3.10 ± 0.19* | NM_001147 |

| ANGPT4 | Angiopoietin-4 | ND | NM_015985 |

| ANGPTL1 | Angiopoietin-like 1 | 1.33 ± 0.15 | NM_004673 |

| ANGPTL2 | Angiopoietin-like 2 | 1.11 ± 0.18 | NM_012098 |

| ANGPTL3 | Angiopoietin-like 3 | ND | NM_014495 |

| ANGPTL4 | Angiopoietin-like 4 | 1.04 ± 0.15 | NM_139314 |

| TEK | TEK tyrosine kinase (TIE-2 receptors) | 1.14 ± 0.10 | NM_000459 |

| TIE1 | Tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin-like and EGF-like domains 1 | 1.18 ± 0.11 | NM_005424 |

| Vascular endothelial growth factors and related genes | |||

| VEGF-A | Vascular endothelial growth factor A | 1.15 ± 0.20 | NM_003376 |

| VEGFB | Vascular endothelial growth factor B | 1.14 ± 0.10 | NM_003377 |

| VEGFC | Vascular endothelial growth factor C | 1.16 ± 0.09 | NM_005429 |

| FIGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor D | 1.06 ± 0.10 | NM_004469 |

| FLT1 | fms-related tyrosine kinase 1 (VEGFR-1) | 0.95 ± 0.10 | NM_00209 |

| FLT3 | fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 | 1.29 ± 0.21 | NM_004419 |

| FLT4 | fms-related tyrosine kinase 4 (VEGFR-3) | 0.89 ± 0.18 | NM_182925 |

| KDR | Kinase insert domain protein receptor (Flk-1, VEGFR2) | 1.11 ± 0.12 | NM_002253 |

| NRP1 | Neuropilin-1 | 1.05 ± 0.08 | NM_003873 |

| NRP2 | Neuropilin-2 | 1.06 ± 0.10 | NM_201266 |

| PROK-1 | Endocrine gland-derive vascular endothelial growth factor | 1.09 ± 0.15 | NM_032414 |

| Miscellaneous pro-angiogenic genes | |||

| AMOT | Angiomotin | 1.04 ± 0.09 | NM_133265 |

| ANG | Angiogenin | 1.82 ± 0.11* | NM_001145 |

| CEACAM1 | Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule | 0.95 ± 0.11 | NM_001712 |

| CD44 | CD44 molecule | 1.16 ± 0.11 | NM_000610 |

| CDH5 | VE cadherin | 1.02 ± 0.09 | NM_001795 |

| CTGF | Connective tissue growth factor | 1.31 ± 0.19 | NM_001901 |

| EDG1 | Sphinosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 | 1.12 ± 0.09 | NM_001400 |

| EDIL3 | EGF-like repeats and discoidin I-like domains 3 | 2.45 ± 0.34* | NM_005711 |

| ENPP2 | Ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase /phosphodiesterase 2 | 1.02 ± 0.15 | NM_006209 |

| EPHB2 | Ephrin B2 receptors | 1.92 ± 0.21* | NM_004433 |

| F2 | Coagulation factor 2 | 1.05 ± 0.09 | NM_000506 |

| FOXC2 | Mesenchyme forkhead 1 | 2.31 ± 0.32* | NM_005251 |

| FST | Follistatin | 2.82 ± 0.49* | NM_006350 |

| GRN | Granulin | 0.91 ± 0.07 | NM_002087 |

| HEY1 | Hairy/enhancer-of-split related with YRPW motif 1 | 1.31 ± 0.19 | NM_012258 |

| KIT | Kit oncogene | 0.90 ± 0.11 | NM_000222 |

| LEP | Leptin | 0.94 ± 0.08 | NM_000230 |

| MDK | Neurite growth promoting factor 2 | 1.22 ± 0.13 | NM_002391 |

| MMP2 | Matrix metallopeptidase 2 | 1.13 ± 0.10 | NM_004530 |

| PECAM1 | Platelet/endothelial adhesion molecule 1 | 0.98 ± 0.09 | NM_000442 |

| PGK1 | Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | 1.02 ± 0.09 | NM_000291 |

| PLG | Plasminogen | ND | NM_000301 |

| PRL | Prolactin | 2.21 ± 0.07* | NM_000948 |

| PROX1 | Prospero-related homeobox1 | 0.86 ± 0.21 | NM_002763 |

| PTN | Pleiotrophin | 0.95 ± 0.09 | NM_002825 |

| XLKD1 | Lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluron receptor 1 (LYVE1) | 0.89 ± 0.15 | NM_006691 |

| Growth factors | |||

| CSF3 | Colony stimulating factor 3 | 1.02 ± 0.18 | NM_172220 |

| ECGF1 | Platelet-derived endothelial growth factor 1 | 1.23 ± 0.19 | NM_001953 |

| FGF1 | Fibroblast growth factor 1 | 1.05 ± 0.18 | NM_000800 |

| FGF2 | Fibroblast growth factor 2 | 1.91 ± 0.21* | NM_002006 |

| FGF4 | Fibroblast growth factor 4 | ND | NM_002007 |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor | 1.29 ± 0.21 | NM_000601 |

| PDGFB | Platelet-derived growth factor β polypeptide | 1.10 ± 0.13 | NM_002608 |

| PDGFRA | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor α polypeptide | 1.16 ± 0.11 | NM_006206 |

| PDGFRB | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor β polypeptide | 1.28 ± 0.14 | NM_002609 |

| PTN | Pleiotrophin | 1.19 ± 0.18 | NM_002825 |

| TGFBA | Transforming growth factor α | 1.19 ± 0.13 | NM_003236 |

| TGFB1 | Transforming growth factor β1 | 1.14 ± 0.09 | NM_000660 |

| Chemokines and cytokines | |||

| CXCL2 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 2 (Groβ) | 1.91 ± 0.21* | NM_002089 |

| CXCL8 | Interleukin-8 | 1.22 ± 0.15 | NM_000584 |

| CXCL10 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 (IP-10) | 1.21 ± 0.19 | NM_001565 |

| CXCL12 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12 (SDF-1) | 1.54 ± 0.16* | NM_000609 |

| IFNB1 | Interferon-β1 | 0.83 ± 0.12 | NM_002176 |

| IFNG | Interferon-γ | 1.35 ± 0.15 | NM_000619 |

| IL12A | Interleukin-12A | 1.12 ± 0.22 | NM_000882 |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor α | 0.89 ± 0.12 | NM_000594 |

| TNFSF15 | Tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 15 | 0.84 ± 0.13 | NM_005118 |

| Matrix genes and integrins | |||

| COL4A1 | Collagen, type IV, α1 | 1.14 ± 0.16 | NM_001845 |

| COL4A2 | Collagen, type IV, α2 | 1.04 ± 0.11 | NM_001846 |

| COL4A3 | Collagen, type IV, α3 | 1.28 ± 0.21 | NM_000091 |

| COL15A1 | Collagen, type XV, α1 | 0.61 ± 0.13* | NM_001855 |

| COL18A1 | Collagen, type XVIII, α1 | 1.22 ± 0.17 | NM_130445 |

| FBLN5 | Fibulin-5 | 1.32 ± 0.19 | NM_006329 |

| FGA | Fibrinogen α-chain | ND | NM_000499 |

| FN1 | Fibronectin-1 | 1.22 ± 0.21 | NM_212476 |

| HSPG2 | Perlecan | 1.10 ± 0.12 | NM_005529 |

| ITGA4 | Integrin-α4 | 0.86 ± 0.14 | NM_000885 |

| ITGAV | Integrin- αV | 1.11 ± 0.11 | NM_002210 |

| ITGB3 | Integrin-β3 | 1.04 ± 0.11 | NM_000212 |

| Angiogenesis inhibitors | |||

| ADAMTS1 | ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif1. | 11 ± 0.91 | NM_006988 |

| BAI-1 | Brain-specific angiogenesis inhibitor 1 | 1.11 ± 0.21 | NM_001702 |

| CHGA | Chromogranin | ND | NM_001275 |

| LECT1 | Leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 1 (Lect-1) | ND | NM_007015 |

| PF4 | Platelet factor 4 | 0.89 ± 0.14 | NM_002619 |

| SEMA3F | Semaphorin 3F | 1.34 ± 0.21 | NM_004186 |

| SERPINB5 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor clade B, member 5 | ND | NM_002639 |

| SERPINC1 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor clade C, member 1 | 1.29 ± 0.22 | NM_000488 |

| SERPINF1 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor clade F, member 1 | 1.19 ± 0.18 | NM_002615 |

| THBS1 | Thrombospondin-1 | 1.24 ± 0.18 | NM_003246 |

| THBS2 | Thrombospondin-2 | 1.23 ± 0.15 | NM_003247 |

| TIMP2 | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 | 1.03 ± 0.07 | NM_003255 |

| TIMP3 | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 | 1.11 ± 0.17 | NM_000462 |

| TNMD | Tenomodulin | 1.22 ± 0.13 | NM_022144 |

| TNNI1 | Troponin I type 1 | 0.63 ± 0.12* | NM_003281 |

| VASH1 | Vasohibin 1 | 1.21 ± 0.14 | NM_014909 |

Biopsies were obtained from vastus lateralis muscles of eight patients with severe COPD (experiment 1). Values are means ± SE, expressed as fold change relative to control subjects.

P < 0.05, compared with control subjects. ND, not detected.

Experiment 2

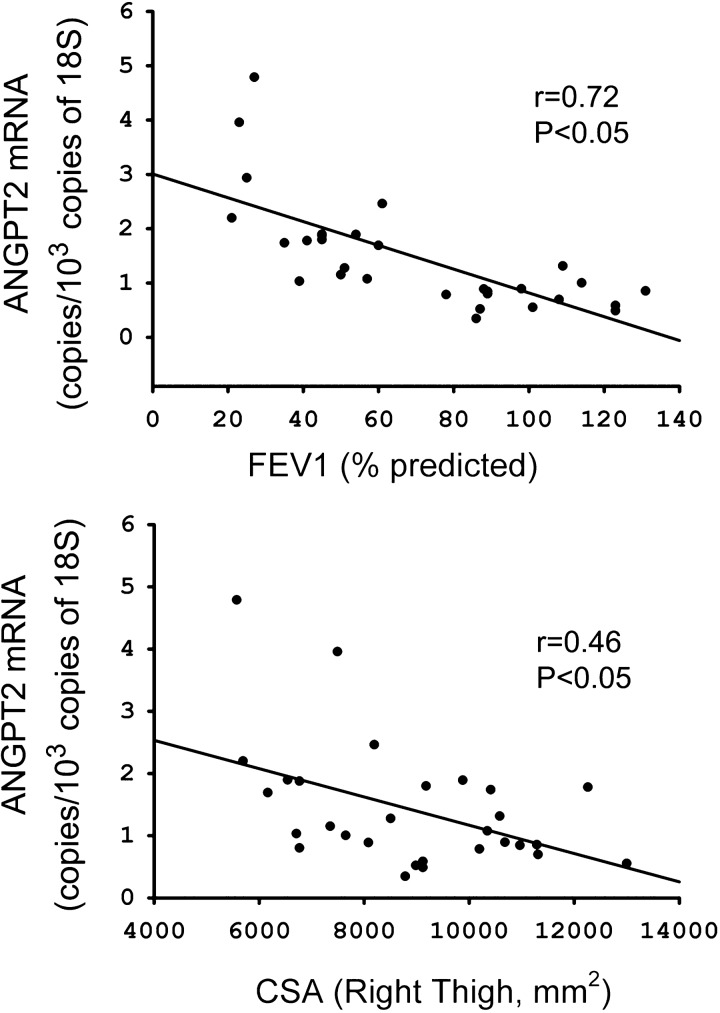

Characteristics of vastus lateralis and diaphragm cohorts are listed in Tables 4 and 5. No significant differences in age, weight, or nutritional status were observed between control subjects and COPD patients (Tables 4 and 5). However, FEV1, FVC, FEV1-to-FVC ratios, and arterial Po2 values were significantly lower in each group of COPD patients compared with their corresponding control groups (Tables 4 and 5). ANGPT2 mRNA levels were ∼3.8-fold higher in vastus lateralis muscles of COPD patients (P < 0.05), compared with the diaphragm, whereas ANGPT1 and CD31 levels did not significantly differ between the two groups (Fig. 1A). Immunoblotting revealed significantly greater ANGPT2 protein levels in vastus lateralis muscles of COPD patients compared with control subjects (Fig. 1, B and C), but significantly lower levels of VEGF mRNA (Fig. 1A). No significant differences in ANGPT1, ANGPT2, VEGF, and CD31 mRNA levels were observed between the diaphragms of control subjects and COPD patients (Fig. 1D). ANGPT2 mRNA levels in the vastus lateralis correlate negatively with predicted percent FEV1 (r = 0.72, P < 0.05) and right thigh CSA (r = 0.46, P < 0.05) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Relationship between ANGPT2 mRNA expression, forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1; %predicted; top), and right thigh cross-sectional area (CSA; bottom) in vastus lateralis muscles of control subjects and COPD patients.

Experiment 3

In human myoblasts, expressions of ANGPT1 and ANGPT2 mRNA were significantly induced by the proinflammatory cytokines IFN-γ and IFN-β (Fig. 3). TNF-α significantly attenuated ANGPT1, but had no effect on ANGPT2 (Fig. 3). The oxidant H2O2 exerted differential effects on angiopoietin expression, significantly attenuating ANGPT1, and significantly upregulating ANGPT2 (Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study are as follows: 1) in the vastus lateralis muscles of COPD patients, 10 proangiogenesis factors that promote neovascularization and vascular stabilization are significantly upregulated; 2) levels of one of these factors, ANGPT2, positively correlate with severity of COPD and degree of muscle wasting; 3) muscle-derived ANGPT1 and ANGPT2 expressions are significantly induced by interferons, but are differentially regulated by H2O2: ANGPT1 is significantly downregulated by H2O2, whereas ANGPT2 is significantly upregulated.

Angiogenesis-related Gene Expression in Human Vastus Lateralis Muscles

Skeletal muscle fiber production of angiogenesis-related factors plays a number of important roles related to the stabilization of capillary networks and maintenance of normal O2 supply to active muscle fibers. The importance of normal capillarity in muscle performance is delineated by a strong positive relationship between peak exercise O2 consumption and muscle capillary density (23). In patients with moderate or severe COPD, no information exists as to whether reduced limb muscle contractile function is mediated, in part, by abnormalities in angiogenesis factor production. To the best of our knowledge, there have only been two published studies that evaluate the expression of VEGF family members in limb muscles of COPD patients. Barreiro et al. (5) reported that VEGFA protein levels are significantly lower in the vastus lateralis muscles of patients with severe COPD compared with control subjects, while Jatta et al. (24) found no differences in mRNA expressions of VEGFA, VEGFB, and VEGFC genes in the tibialis anterior muscles of similar patients. In the present study, we found that 10 proangiogenesis factors are significantly upregulated in limb muscles of COPD patients compared with control subjects (Table 3). These factors are known to promote neovascularization, enhance vasculature stability, and protect endothelial cells against proapoptotic stimuli. We, therefore, propose that limb muscles of COPD patients possess greater potentials for angiogenesis and vascular stability than do those of control subjects, even in the face of reduced VEGF expression (Fig. 1).

Molecular mechanisms responsible for upregulation of specific proangiogenesis factors in muscles of COPD patients were not fully investigated in the present study; however, we found that expression of the transcription factor FOXC2 is significantly elevated in COPD patients (Table 3). FOXC2 is a member of the FOXO family of transcription factors that regulate the expression of angiogenesis factors, including ANGPT2 in endothelial cells (12). FOXC2 plays a positive role in embryonic vascular development and promotes the production of several angiogenesis factors in the mature vasculature (33). The importance of FOXC2 to the regulation of muscle-derived angiogenesis factors, such as those that are upregulated in COPD patients, remains to be confirmed.

Another important factor that may have influenced the upregulation of proangiogenesis factors in COPD patients is the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Angiogenesis factor production, particularly that of VEGF from muscle cells, is regulated by ROS (31). In the present study, we found that H2O2 triggered significant upregulation of muscle-derived ANGPT2 expression (Fig. 3). These results strongly support the theory that relatively high ROS levels in the skeletal muscles of COPD patients are involved in the upregulation of ANGPT2. Furthermore, it is likely that the relatively milder oxidative stress that is seen in the diaphragm, compared with the limb muscles, might underlie the lesser degree of ANGPT2 induction observed in the diaphragms of COPD patients (Fig. 1).

Proinflammatory cytokines may also influence the regulation of angiogenesis factors in skeletal muscles of COPD patients. In our laboratory's recent study, we reported that interleukin-1β reduces muscle ANGPT2 expression, while TNF-α and interleukin-6 exert no effects (39). In the present study, we found that the proinflammatory interferons IFN-β and IFN-γ exert strong stimulatory effects on muscle-derived ANGPT1 and ANGPT2 production (Fig. 3). These effects are similar to those observed in tumor cells (13), but differ from the inhibitory effects of interferons on angiopoietin expression in endothelial cells (6) and osteoclasts (26), indicating that interferons regulate angiopoietin production in a cell type-dependent manner. Whether interferons are responsible for the elevated ANGPT2 levels that are seen in limb muscles of COPD patients remains speculative, because limited information is available regarding interferon levels in these patients (5).

We observed that muscle-derived ANGPT1 expression significantly declines in response to H2O2 exposure, whereas interferons stimulate ANGPT1 production (Fig. 3). These findings emphasize the importance of oxidative stress in driving muscle-derived angiopoietin production toward increased ANGPT2 expression, while simultaneously attenuating ANGPT1 expression (Fig. 3). The functional relevance of this inhibitory effect of H2O2 on ANGPT1 to overall skeletal muscle function remains to be investigated. However, we speculate that reduced ANGPT1 production may result in oxidative stress-mediated muscle dysfunction in COPD patients by attenuating its proangiogenic and promyogenic effects.

Functional Roles of ANGPT2 in Skeletal Muscles

Very little is known about the functional roles of angiopoietins in skeletal muscle. Dallabrida et al. (11) have reported that ANGPT1 and ANGPT2 proteins enhance adhesion of skeletal satellite cells to extracellular matrixes. Our group found that ANGPT2 strongly stimulates survival of cultured skeletal myoblasts and enhances the differentiation of these cells into myotubes (39). We also found that the prosurvival effect of ANGPT2 on myoblasts is mediated through direct activation of important prosurvival pathways, including the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT and ERK1/2 pathways (39). ANGPT2 may also enhance the release of secondary mediators that act in an autocrine fashion to enhance muscle cell viability. These mediators include leptin, which is induced by ANGPT2 in muscle cells and acts to protect cells against the cytotoxic effects of H2O2 (14).

ANGPT2 promotes survival and stimulates myoblast differentiation (39), indicating that it plays a positive role in promoting the myogenesis program of skeletal muscle satellite cells. Enhanced ANGPT2 expression in limb muscles of COPD patients is, therefore, probably a positive adaptation designed to improve the regenerative capacities of muscles in response to injury. Little is as yet known about the abilities of primary cells to repair muscle fiber injury in skeletal muscles of COPD patients, although Martinez-Llorens et al. (38) have reported that satellite cell number and activation status are significantly higher in external intercostal muscles, compared with control subjects, indicating the presence of an active muscle fiber repair program. Thus, in addition to a stimulatory effect on the myogenesis program, ANGPT2 is also likely to promote muscle repair through induction of angiogenesis.

Muscle regeneration requires coordinated induction of angiogenesis and myogenesis programs. Myogenesis originates with resident satellite cells (muscle precursors), while angiogenesis originates from endothelial cells and is regulated, to a large extent, by factors that are produced by neighboring muscle cells (42). Although it is likely that ANGPT2 modulates angiogenesis in regenerating skeletal muscles by acting directly on TIE2 receptors on the surface of endothelial cells, it is also entirely conceivable that ANGPT2 enhances angiogenesis by acting on the release of proangiogenesis factors from skeletal muscle cells. Further studies are, therefore, required to identify the molecular mechanisms through which ANGPT2 regulates angiogenesis and myogenesis in skeletal muscles.

In summary, this study indicates that several proangiogenesis factors, including ANGPT2, are significantly upregulated in the vastus lateralis muscles of COPD patients, and that this ANGPT2 expression is positively regulated by interferons and H2O2. On the basis of these findings, and on those of previous studies documenting a positive effect of ANGPT2 on skeletal muscle cell survival and differentiation, we propose that ANGPT2 may play a positive role in improving the limb muscle regenerative capacities of COPD patients.

Study Limitations

A major limitation of this study pertains to the fact that a relatively low number of control subjects and COPD patients were recruited for low-density array screening of angiogenesis-related genes. One reason for this is that the vastus lateralis muscle biopsy is an invasive procedure, thereby restricting the number of available volunteers. Moreover, very restrictive inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to the selection of equal numbers of control subjects and COPD patients, with the expectation that they should have very similar characteristics, including physical activity and nutritional status. It should be emphasized, however, that one of the main findings of experiment 1, that ANGPT2 expression is upregulated in the vastus lateralis muscles of patients with COPD, was verified in experiment 2 using a relatively larger population of COPD patients, including those with muscle wasting. Results of that experiment confirmed that ANGPT2 expression is indeed upregulated in the vastus lateralis muscle, relative to a correspondingly larger population of control subjects.

GRANTS

This study is funded by grants from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR). M. Mofarrahi is the recipient of a CIHR Post-Doctoral Fellowship and Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship-Doctoral Award. S.N.A. Hussain is the recipient of a James McGill Professor award, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: M.M., I.S., S.H., Y.G., and R.D. performed experiments; M.M., I.S., T.V., S.H., Y.G., R.D., F.M., and S.N.A.H. analyzed data; M.M. and S.N.A.H. drafted manuscript; M.M., I.S., T.V., S.H., Y.G., R.D., F.M., and S.N.A.H. approved final version of manuscript; I.S., T.V., F.M., and S.N.A.H. conception and design of research; T.V., S.H., Y.G., R.D., F.M., and S.N.A.H. interpreted results of experiments; S.N.A.H. prepared figures; S.N.A.H. edited and revised manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Allaire J, Maltais F, LeBlanc P, Simard PM, Whittom F, Doyon JF, Simard C, Jobin J. Lipofuscin accumulation in the vastus lateralis muscle in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Muscle Nerve 25: 383–389, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Thoracic Society. Standards for the diagnosis and care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 152: S77–S120, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andersen P. Capillary density in skeletal muscle of man. Acta Physiol Scand 95: 203–205, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barreiro E, Gea J, Corominas JM, Hussain SNA. Nitric oxide synthases and protein oxidation in the quadriceps femoris of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 29: 771–778, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barreiro E, Schols AM, Polkey MI, Galdiz JB, Gosker HR, Swallow EB, Coronell C, Gea J. Cytokine profile in quadriceps muscles of patients with severe COPD. Thorax 63: 100–107, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Battle TE, Lynch RA, Frank DA. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 activation in endothelial cells is a negative regulator of angiogenesis. Cancer Res 66: 3649–3657, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bergstrom J. Percutaneous needle biopsy of skeletal muscle in physiological and clinical research. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 35: 609–616, 1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bloor CM. Angiogenesis during exercise and training. Angiogenesis 8: 263–271, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brindle NP, Saharinen P, Alitalo K. Signaling and functions of angiopoietin-1 in vascular protection. Circ Res 98: 1014–1023, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Couillard A, Maltais F, Saey D, Debigare R, Michaud A, Koechlin C, LeBlanc P, Prefaut C. Exercise-induced quadriceps oxidative stress and peripheral muscle dysfunction in COPD patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 167: 1664–1669, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dallabrida SM, Ismail N, Oberle JR, Himes BE, Rupnick MA. Angiopoietin-1 promotes cardiac and skeletal myocyte survival through integrins. Circ Res 96: e8–e24, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Daly C, Pasnikowski E, Burova E, Wong V, Aldrich TH, Griffiths J, Ioffe E, Daly TJ, Fandl JP, Papadopoulos N, McDonald DM, Thurston G, Yancopoulos GD, Rudge JS. Angiopoietin-2 functions as an autocrine protective factor in stressed endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 15491–15496, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dickson PV, Hamner JB, Streck CJ, Ng CY, McCarville MB, Calabrese C, Gilbertson RJ, Stewart CF, Wilson CM, Gaber MW, Pfeffer LM, Skapek SX, Nathwani AC, Davidoff AM. Continuous delivery of IFN-beta promotes sustained maturation of intratumoral vasculature. Mol Cancer Res 5: 531–542, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eguchi M, Liu Y, Shin EJ, Sweeney G. Leptin protects H9c2 rat cardiomyocytes from H2O2-induced apoptosis. FEBS J 275: 3136–3144, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Engelen MP, Schols AM, Does JD, Deutz NE, Wouters EF. Altered glutamate metabolism is associated with reduced muscle glutathione levels in patients with emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161: 98–103, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fabbri LM, Hurd SS. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD: 2003 update. Eur Respir J 22: 1–2, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fiedler U, Scharpfenecker M, Koidl S, Hegen A, Grunow V, Schmidt JM, Kriz W, Thurston G, Augustin HG. The Tie-2 ligand angiopoietin-2 is stored in and rapidly released upon stimulation from endothelial cell Weibel-Palade bodies. Blood 103: 4150–4156, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goldman HI, Becklake MR. Respiratory function test. Normal values at median altitudes and prediction of normal result. Am Rev Tuberc 79: 457–467, 1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gosker HR, Kubat B, Schaart G, van Dijk PJ, Wouters EF, Schols AM. Myopathological features in skeletal muscle of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 22: 280–285, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gosker HR, van Mameren H, van Dijk PJ, Engelen MP, van der Vusse GJ, Wouters EF, Schols AM. Skeletal muscle fibre-type shifting and metabolic profile in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 19: 617–625, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gu J, Yamamoto H, Ogawa M, Ngan CY, Danno K, Hemmi H, Kyo N, Takemasa I, Ikeda M, Sekimoto M, Monden M. Hypoxia-induced up-regulation of angiopoietin-2 in colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep 15: 779–783, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hepple RT, Hogan MC, Stary C, Bebout DE, Mathieu-Costello O, Wagner PD. Structural basis of muscle O2 diffusing capacity: evidence from muscle function in situ. J Appl Physiol 88: 560–566, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ingjer F. Effects of endurance training on muscle fibre ATP-ase activity, capillary supply and mitochondrial content in man. J Physiol 294: 419–432, 1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jatta K, Eliason G, Portela-Gomes GM, Grimelius L, Caro O, Nilholm L, Sirjso A, Piehl-Aulin K, Abdel-Halim SM. Overexpression of von Hippel-Lindau protein in skeletal muscles of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Pathol 62: 70–76, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jobin J, Maltais F, Doyon JF, LeBlanc P, Simard PM, Simard AA, Simard C. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: capillarity and fiber-type characteristics of skeletal muscle. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 18: 432–437, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kasama T, Isozaki T, Odai T, Matsunawa M, Wakabayashi K, Takeuchi HT, Matsukura S, Adachi M, Tezuka M, Kobayashi K. Expression of angiopoietin-1 in osteoblasts and its inhibition by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma. Transl Res 149: 265–273, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kim HC, Mofarrahi M, Hussain SN. Skeletal muscle dysfunction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 3: 637–658, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim I, Kim JH, Moon SO, Kwak HJ, Kim NG, Koh GY. Angiopoietin-2 at high concentration can enhance endothelial cell survival through the phosphatidylinsitol 3′-kinase/AKT signal transduction pathway. Oncogene 19: 4549–4552, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Knudson RJ, Slatin RC, Lebowitz MD, Burrows B. The maximal expiratory flow-volume curve. Normal standards, variability, and effects of age. Am Rev Respir Dis 113: 587–600, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Koga K, Todaka T, Morioka M, Hamada J, Kai Y, Yano S, Okamura A, Takakura N, Suda T, Ushio Y. Expression of angiopoietin-2 in human glioma cells and its role for angiogenesis. Cancer Res 61: 6248–6254, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kosmidou I, Xagorari A, Roussos C, Papapetropoulos A. Reactive oxygen species stimulate VEGF production from C2C12 skeletal myotubes through a PI3K/Akt pathway. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280: L585–L592, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krikun G, Schatz F, Finlay T, Kadner S, Mesia A, Gerrets R, Lockwood CJ. Expression of angiopoietin-2 by human endometrial endothelial cells: regulation by hypoxia and inflammation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 275: 159–163, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kume T. Foxc2 transcription factor: a newly described regulator of angiogenesis. Trends Cardiovasc Med 18: 224–228, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lochmuller H, Johns T, Shoubridge EA. Expression of the E6 and E7 genes of human papillomavirus (HPV16) extends the life span of human myoblasts. Exp Cell Res 248: 186–193, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mabuchi K, Sreter FA. Actomyosin ATPase. II. Fiber typing by histochemical ATPase reaction. Muscle Nerve 3: 233–239, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maisonpierre PC, Suri C, Jones PF, Bartunkova S, Wiegand SJ, Radziejewski C, Compton D, McClain J, Aldrich TH, Papadopoulos N, Daly TJ, Davis S, Sato T, Yancopoulos GD. Angiopoietin-2, a natural antagonist for Tie-2 that disrupts in vivo angiogenesis. Science 277: 55–62, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marquis K, Debigare R, Lacasse Y, LeBlanc P, Jobin J, Carrier G, Maltais F. Midthigh muscle cross-sectional area is a better predictor of mortality than body mass index in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166: 809–813, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Martinez-Llorens J, Casadevall C, Lloreta J, Orozco-Levi M, Barreiro E, Broquetas J, Gea J. Activation of satellite cells in the intercostal muscles of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Bronconeumol 44: 239–244, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mofarrahi M, Hussain SN. Expression and functional roles of angiopoietin-2 in skeletal muscles. PLos One 6: e22882, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mofarrahi M, Nouh T, Qureshi S, Guillot L, Mayaki D, Hussain SNA. Regulation of angiopoietin expression by bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L955–L963, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Montes de OM, Torres SH, De SJ, Mata A, Hernandez N, Talamo C. Skeletal muscle inflammation and nitric oxide in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 26: 390–397, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rhoads RP, Johnson RM, Rathbone CR, Liu X, Temm-Grove C, Sheehan SM, Hoying JB, Allen RE. Satellite cell-mediated angiogenesis in vitro coincides with a functional hypoxia-inducible factor pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C1321–C1328, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Roviezzo F, Tsigkos S, Kotanidou A, Bucci M, Brancaleone V, Cirino G, Papapetropoulos A. Angiopoietin-2 causes inflammation in vivo by promoting vascular leakage. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 314: 738–744, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Singh H, Tahir TA, Alawo DO, Issa E, Brindle NP. Molecular control of angiopoietin signalling. Biochem Soc Trans 39: 1592–1596, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Takabatake N, Nakamura H, Abe S, Inoue S, Hino T, Saito H, Yuki H, Kato S, Tomoike H. The relationship between chronic hypoxemia and activation of the tumor necrosis factor-alpha system in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161: 1179–1184, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Whittom F, Jobin J, Simard PM, LeBlanc P, Simard C, Bernard S, Belleau R, Maltais F. Histochemical and morphological characteristics of the vastus lateralis muscle in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Med Sci Sports Exerc 30: 1467–1474, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]