Abstract

Subcellular calcium signalling silencing is a novel and distinct cellular and molecular adaptive response to rapid cardiac activation. Calcium signalling silencing develops during short‐term sustained rapid atrial activation as seen clinically during paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF). It is the first ‘anti‐arrhythmic’ adaptive response in the setting of AF and appears to counteract the maladaptive changes that lead to intracellular Ca2+ signalling instability and Ca2+‐based arrhythmogenicity. Calcium signalling silencing results in a failed propagation of the [Ca2+]i signal to the myocyte centre both in patients with AF and in a rabbit model. This adaptive mechanism leads to a substantial reduction in the expression levels of calcium release channels (ryanodine receptors, RyR2) in the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and the frequency of Ca2+ sparks and arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves remains low. Less Ca2+ release per [Ca2+]i transient, increased fast Ca2+ buffering strength, shortened action potentials and reduced L‐type Ca2+ current contribute to a substantial reduction of intracellular [Na+]. These features of Ca2+ signalling silencing are distinct and in contrast to the changes attributed to Ca2+‐based arrhythmogenicity. Some features of Ca2+ signalling silencing prevail in human AF suggesting that the Ca2+ signalling ‘phenotype’ in AF is a sum of Ca2+ stabilizing (Ca2+ signalling silencing) and Ca2+ destabilizing (arrhythmogenic unstable Ca2+ signalling) factors. Calcium signalling silencing is a part of the mechanisms that contribute to the natural progression of AF and may limit the role of Ca2+‐based arrhythmogenicity after the onset of AF.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, atrial myocyte, calcium dynamics, calcium imaging

Abbreviations

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular calcium concentration

- CaMKII

Ca2+/calmodulin dependant kinase II

- CaT

calcium transient

- CRU

calcium release unit

- DAD

delayed afterdepolarization

- EAD

early afterdepolarization

- LTTC

voltage gated L‐type Ca2+ channel

- ICa,L

L‐type Ca2+ current

- IP3R

inositol‐1,4,5‐trisphosphate‐receptor

- ITI

transient inward current

- [Na+]i

intracellular sodium concentration

- NCX

Na+/Ca2+ exchanger

- PKA

protein Kinase A

- RyR2

ryanodine receptor type 2

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- TT

T‐tubule

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia, with a prevalence of > 6% in the population (Kannel et al. 1998). Despite advances in understanding the underlying disease mechanisms and the development of more effective treatment options, prevalence of AF is projected to increase even further (Kirchhof et al. 2013). Recent guidelines advocate a ‘personalized’ management of AF, which focuses on treating AF according to individual disease mechanisms (Kirchhof et al. 2013). It is becoming more evident that the different aetiologies of AF lead to distinct ‘types’ of AF. This implies that atrial fibrillation is likely a common endpoint for disparate pathomechanisms. It is therefore crucial to better understand the mechanisms underlying these different types of AF to be able to offer treatment and/or preventative measures specifically tailored to a type of AF.

Subcellular Ca2+ signalling undergoes complex changes as part of the atrial remodelling process before and/or after the initiation of the arrhythmia (Greiser et al. 2011). It is still contentious, however, which role these changes play in AF arrhythmogenesis. Specifically, the contribution of Ca2+‐based arrhythmogenic mechanisms to AF initiation and maintenance remains controversial. The characterization of the novel mechanism of subcellular Ca2+ signalling silencing shows that the rapid atrial rate, which occurs after the onset of AF, initiates an adaptive protective response rather than arrhythmogenic Ca2+ instability. Ca2+ signalling silencing counteracts the rapid rate‐induced intracellular Ca2+ overload and results in an anti‐arrhythmic stabilization of subcellular Ca2+ signalling.

There is evidence that unstable intracellular Ca2+ signalling occurs in AF (Hove‐Madsen et al. 2004; Neef et al. 2010). This Ca2+ signalling instability has been suggested to contribute to atrial arrhythmogenicity and the maintenance of AF in patients (Voigt et al. 2012). The discovery of Ca2+ signalling silencing suggests that the Ca2+ signalling ‘phenotype’ present in a specific AF patient is the sum of Ca2+ stabilizing (i.e. Ca2+ signalling silencing) and Ca2+ destabilizing (i.e. arrhythmogenic Ca2+ instability) factors. Consistent with this concept is the finding that in some patients the effects of Ca2+ signalling silencing appear to prevail (Greiser et al. 2014). The identification of the Ca2+ silencing response has important implications for clinical AF and the role of Ca2+‐based arrhythmogenesis in the natural progression of AF.

Normal Ca2+ handling in atrial myocytes

Membrane depolarization activates voltage‐gated L‐type Ca2+ channels (LTCCs). This initiates the influx of a small amount of Ca2+ into the cardiac myocyte. The small increase in subsarcolemmal Ca2+ triggers the release of larger quantities of Ca2+ from the nearby Ca2+ storage organelle of the cardiac myocyte, the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), through its Ca2+ release channels, the ryanodine receptors (RyR2). This transient increase in intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) initiates contraction as free Ca2+ binds to the myofilaments. This Ca2+‐induced Ca2+ release, which is characteristic for cardiac excitation–contraction coupling, is fundamentally the same in atrial and ventricular myocytes (Bers, 2001). Relaxation occurs as Ca2+ is released from the myofilaments, re‐sequestered into the SR by the SR Ca2+‐ATPase and extruded from the cell by the sarcolemmal Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX).

Atrial calcium release

Calcium release units (CRUs) consist of groups of RyR2s that are formed in specialized regions of the SR (Franzini‐Armstrong et al. 1999). Upon activation this primary Ca2+ release unit produces a Ca2+ spark, which is the fundamental Ca2+ release event (Cheng et al. 1993). In atrial myocytes CRUs are organized along the Z‐disk of the sarcomere and spaced ∼1 μm apart, similar to CRU organization in ventricular myocytes (Chen‐Izu et al. 2006).

Important modulation of the RyR2s’ sensitivity to triggering by [Ca2+]i is achieved through phosphorylation, nitrosylation and oxidation (O'Brien et al. 2015). Higher RyR2 Ca2+ sensitivity has been implicated in contributing to unstable arrhythmogenic Ca2+ signalling in ventricular (heart failure) and atrial (atrial fibrillation) disease (see below) and a distinct alteration in RyR2 phosphorylation is part of Ca2+ signalling silencing. While RyR2s are the major Ca2+ release channels in cardiac myocytes, Ca2+ release in atrial myocytes appears to be modulated by inositol‐1,4,5‐trisphosphate‐receptors (IP3Rs), which colocalize to RyR2s and are much more abundant in atrial than ventricular myocytes (Lipp et al. 2000). IP3Rs are activated by IP3 that is generated in response to G protein‐coupled receptor or receptor tyrosine kinase stimulation. The precise effect of IP3R‐mediated modulation of atrial Ca2+ release is controversial in the literature. However, knockout of the predominant cardiac isoform of IP3R (type 2) abolished an endothelin 1‐mediated positive inotropic and arrhythmogenic effect (Li et al. 2005), suggesting that IP3Rs can be potent modulators of atrial calcium signalling.

Cellular arrhythmogenic mechanisms: Ca2+ waves and ectopic focal discharges

Ca2+‐based arrhythmogenicity caused by unstable intracellular Ca2+ signalling is mediated by (1) intracellular Ca2+ waves and (2) Ca2+‐activated inward current. Ca2+ ‘overload’ (i.e. increased [Ca2+]SR) (Wier et al. 1987) increases the sensitivity of the RyR2s to be activated by cytosolic [Ca2+]i. This higher [Ca2+]i sensitivity leads to an increased probability of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+ waves. Under these conditions, in addition to the Ca2+ release initiated by an action potential (AP), there can be Ca2+ release events during diastole between the normal AP initiated events. When [Ca2+]i increases due to spontaneous Ca2+ release events, a Ca2+‐based membrane current is activated during diastole. This arrhythmogenic transient inward current (I TI), which is carried by the NCX, is responsible for the generation of delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs) (Berlin et al. 1989). When DADs are sufficiently large they can trigger an extrasystole. Additionally, Ca2+‐activated I TI can occur during repolarization and then contribute to early afterdepolarizations (EADs), which can also trigger extrasystoles. Also, during short APs in the presence of a high [Ca2+]SR, two conditions found during AF, NCX‐mediated late phase 3 EADs can occur (Patterson et al. 2007).

Calcium signalling silencing: an anti‐arrhythmic response to rapid activation

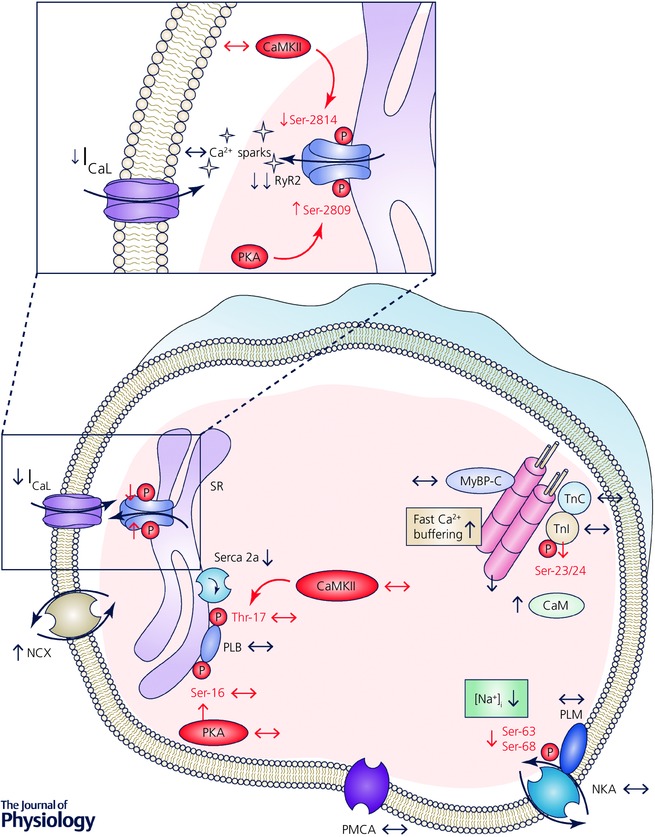

Calcium signalling silencing constitutes the atrial Ca2+ signalling responses to a sustained high atrial activation rate in the absence of cardiovascular disease. Surprisingly, sustained rapid atrial activation does not lead to arrhythmogenic intracellular Ca2+ signalling in healthy atria. Instead, rapid rate alone produces Ca2+ signalling silencing. This mechanism acts to mitigate the effects of the high atrial rate with respect to Ca2+ instability. Key features of Ca2+ signalling silencing are (1) the failure of the centripetal intracellular Ca2+ wave propagation, which results in significantly reduced central‐cellular Ca2+ release, which underlies a reduced whole cell Ca2+ transient; (2) distinct remodelling of the RyR2 complex including a substantial reduction of RyR2 protein expression and reduced CaMKII‐mediated RyR2 phosphorylation; and (3) low intracellular sodium concentration ([Na+]i), which further contributes to the ‘unloading’ of Ca2+. The above mechanisms lead to an unchanged (compared to controls) low rate of Ca2+ sparks and arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves, another important feature of Ca2+ signalling silencing. (For an overview of changes in key Ca2+ handling proteins in Ca2+ signalling silencing, see Fig. 1.) Taken together, Ca2+ signalling silencing prevents arrhythmogenic intracellular Ca2+ signalling instability via novel and distinct mechanisms.

Figure 1. Schematic depiction of changes in function, expression and phosphorylation levels of key Ca2+ handling proteins in Ca2+ signalling silencing.

Arrows denote direction of change; see text for details. CaM, calmodulin; CaMKII, Ca2+/calmodulin‐dependent kinase II; I CaL, L‐type Ca2+ current; MyBP‐C, myosin‐binding protein C; NCX, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger; NKA, Na+/K+‐ATPase; P, phosphate group; PKA, protein kinase A; PLB, phospholamban; PLM, phospholemman; PMCA, plasma membrane Ca2+‐ATPase; RyR2, ryanodine receptor type 2; Ser, serine residue; Serca2a, SR Ca2+‐ATPase type 2a; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; Thr, threonine residue; TnI, troponin I; TnC, troponin C.

Failure of the intracellular Ca2+ wave

Increased fast Ca2+ buffering, NCX upregulation and reduced L‐type Ca2+ current

Intracellular fast Ca2+ buffering strength is increased in Ca2+ signalling silencing due to increases in calmodulin protein expression and increased myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (reduced troponin I phosphorylation, Fig. 1) (Greiser et al. 2014). Atrial cells without T‐tubules rely on Ca2+ diffusion between neighbouring RyR2 clusters to activate regenerative Ca2+ release from the periphery to the core of the myocyte (Berlin, 1995; Hüser et al. 1996). The higher fast Ca2+ buffering strength impedes Ca2+ diffusion in Ca2+ signalling silencing and contributes to the failure of the intracellular Ca2+ wave. The increased sensitivity of NCX to [Ca2+]i seems to be a beneficial mechanism when myocytes that have undergone Ca2+ signalling silencing are rapidly activated. With high rate, Ca2+ entry will be greater due to the high activation frequency of the L‐type Ca2+ current (I Ca,L) even when I Ca,L amplitude is reduced. With the increased Ca2+ entry, NCX is better able to balance that high influx with a relatively higher efflux of Ca2+ than would be the case if the [Ca2+]i sensitivity of the NCX were the same as it is in normal cells. This higher efflux of Ca2+ is reflected in the shortened decay of the subsarcolemmal Ca2+ transient (CaT), which contributes to the failure of the intracellular Ca2+ wave by reducing the subsarcolemmal trigger Ca2+ for the centripetal intracellular Ca2+ wave. In Ca2+ signalling silencing the unique combination of increased Ca2+ buffering strength, upregulated NCX function, reduced I Ca,L and unchanged Ca2+ release properties of the SR (see below) contribute to the failure of the intracellular Ca2+ wave propagation.

Remodelling of the ryanodine receptor complex and arrhythmogenic Ca2+ release

Calcium signalling silencing leads to a distinct remodelling of the RyR2 complex. This entails a substantial and unique reduction of RyR2 protein expression (by ∼80%), increased RyR2 phosphorylation at a predominant PKA site (Ser2809) and reduced phosphorylation at a predominant CaMKII site (Ser2814). Additionally, expression of CaMKIIδ and auto‐phosphorylated CaMKII (CaMKIIpTh286) remains at normal levels (Greiser et al. 2014). While a moderate (20–40%) reduction in RyR2 protein expression levels is reported in most studies in AF patients and AF models (Voigt et al. 2012), it is not as substantial as in calcium signalling silencing. This has important functional implications for Ca2+ spark behaviour. As the RyR2 cluster grid is unchanged in calcium signalling silencing (Greiser et al. 2014), it can be deduced that the individual RyR2 clusters have a significantly reduced number of RyR2 channels. Simulations using an atrial cell model show that an 80% reduction in the number of RyR2 channels in a cluster results in a similarly significant reduction in Ca2+ spark frequency (Greiser et al. 2014). Reduced Ca2+ spark frequency resulting from ‘depleted’ RyR2 clusters can be offset by higher levels of RyR2 phosphorylation, which increase RyR2 open probability (Carter et al. 2006) and will therefore increase Ca2+ spark frequency. Increased RyR2 phosphorylation is a characteristic finding in human AF (Vest et al. 2005; El‐Armouche et al. 2006; Voigt et al. 2012) and AF models (Greiser et al. 2009). Phosphorylation‐mediated RyR2 sensitization has been implicated in underlying unstable Ca2+ signalling (i.e. increased Ca2+ spark frequency and diastolic Ca2+ leak) in AF. Indeed, high CaMKII expression levels are consistently found in atria of AF patients (Tessier et al. 1999; Neef et al. 2010). Moreover, a CaMKII inhibitor normalized increased Ca2+ spark frequency and diastolic Ca2+ leak in human atrial myocytes from AF patients with increased RyR2 phosphorylation at a predominant CaMKII site (Ser2814) (Neef et al. 2010) and reduced the number of DADs recorded from atrial myocytes from patients with AF (Voigt et al. 2012). In calcium signalling silencing, however, the effect of high RyR2 phosphorylation levels at a predominant PKA site (Ser2809) on Ca2+ spark frequency was mitigated by the substantial RyR2 protein depletion resulting in unchanged low Ca2+ spark and Ca2+ wave rates ([Ca2+]SR is unchanged) (Greiser et al. 2014). While increased RyR2 phosphorylation levels at Ser2809 have been found to increase RyR2 open probability (Carter et al. 2006), other reports indicate Ser2030 as the dominant RyR2 PKA phosphorylation site (Xiao et al. 2005). Thus, there is some controversy as to the role of PKA‐mediated RyR2 phosphorylation, but it appears that increased levels of RyR2 phosphorylation at the predominant CaMKII site at Ser2814 facilitate arrhythmogenic unstable Ca2+ signalling in atrial myocytes. Rapid rate, which had been implicated in the activation of CaMKII in AF (Neef et al. 2010), does not induce increases in CaMKII expression in healthy atria and, importantly, even reduced RyR2 phosphorylation levels at the crucial CaMKII site (Ser2814). Thus, the ‘non‐activation’ of CaMKII by rapid rate in healthy atria is an important component of the calcium signalling silencing mechanism. It further suggests that activation of CaMKII in AF and subsequent increases in RyR2 phosphorylation are likely due to other mechanisms, most likely pre‐existing cardiovascular disease (e.g. cardiomyopathy, heart failure).

Finally, IP3R protein expression (Yamada et al. 2001) and agonists (endothelin‐1, angiotensin II) in the IP3 signalling cascade are upregulated in AF (Goette et al. 2000; Mayyas et al. 2010). The role for IP3R‐mediated Ca2+ release in atrial myocytes remains controversial (see above), likely due to the technically difficult evaluation of this Ca2+ release mechanism. Further studies are clearly warranted and might help to elucidate Ca2+ release properties in different AF aetiologies.

Low [Na+]i

[Na+]i is an important regulator of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and altered [Na+]i underlies alterations in intracellular Ca2+ handling in heart disease (e.g. in heart failure) (Pogwizd & Bers, 2004). While this is well known, data regarding [Na+]i homeostasis in atrial disease remain sparse. The first quantitative measurements of [Na+]i in viable atrial myocytes were provided by our study as a part of the calcium signalling silencing mechanism. Resting [Na+]i in normal rabbit atrial myocytes is low (6.86 ± 0.36 mmol l−1) and was reduced in rapid rate‐induced calcium signalling silencing (4.02 ± 0.49 mmol l−1) (Greiser et al. 2014). The low [Na+]i appears to be a consequence of well‐known features of sustained rapid atrial activation: reduction of I Ca,L and shortening of the atrial action potential duration (Greiser & Schotten, 2013). Reduced I Ca,L combined with a short action potential duration leads to a substantial reduction in Ca2+ entry in these cells. Consequently, Na+ entry via NCX is also reduced when sarcolemmal Ca2+ is in pump–leak balance. Calculations of Ca2+ and Na+ membrane fluxes over one activation cycle show that the reduced Ca2+ entry entails a significant reduction in Na+ entry through the NCX. During 1 Hz stimulation 4 times as much Na+ enters the cell through the NCX than through Na+ channels (Despa et al. 2002). At rest Despa et al. reported a 100% higher Na+ influx through NCX than via Na+ channels in rabbit ventricular myocytes (Despa et al. 2002). The substantial reduction of Ca2+ entry through I Ca,L and Ca2+ extrusion (via NCX) together with the coupled reduction in Na+ entry are likely the main mechanism underlying the low [Na]i in calcium signalling silencing.

Thus, the unexpected and novel mechanism of low [Na+]i‐mediated Ca2+ ‘unloading’ as a consequence of rapid rate underlines the importance of Na+ homeostasis in atrial disease. More specifically, increases in late Na+ current have been reported in atrial myocytes from AF patients and have been suggested to underlie Ca2+‐based arrhythmogenesis in AF (Sossalla et al. 2010). However, another study showed that the increases in the late Na+ current in myocytes from AF patients disappeared when recordings were performed at 37°C (Poulet et al. 2015). Given the importance of [Na+]i homeostasis for Ca2+‐based arrhythmogenesis, future studies focusing on atrial [Na+]i handling in AF are needed. Atrial myocytes from patients in AF are likely to show a degree of Na+ unloading due to calcium signalling silencing (as a consequence of the rapid rate).

Role of T‐tubules

In cardiac myocytes, T‐tubules (TTs) are sarcolemmal invaginations of the surface membrane that occur at the Z‐line and have transverse and longitudinal elements (Soeller & Cannell, 1999). Ventricular myocytes have abundant TTs with regular organization (Soeller & Cannell, 1999). This leads to a close proximity of LTCCs to RyR2s in these cells and facilitates a near simultaneous increase in [Ca2+]i after membrane depolarization. In atrial myocytes TT density is lower and TTs are less well organized. In addition, there is evidence for differences in the LTCC microdomain. In a recent study LTCCs in rat ventricular myocytes were found to be located in the TTs, whereas in rat atrial myocytes ∼30% of LTCCs were located in caveolae. Interestingly, reduction of caveolae in atrial cells reduced the frequency of spontaneous calcium release events in these cells (Glukhov et al. 2015). This finding suggests that differences in LTCC–TT microdomains contribute to the differences between atrial and ventricular [Ca2+]i signalling. Atrial TTs occur with higher abundance in sheep (Dibb et al. 2009; Lenaerts et al. 2009), dog (Wakili et al. 2010) and mice (Greiser et al. 2014). A mainly longitudinally oriented, substantial TT system has been described in rat atrial myocytes (Kirk et al. 2003). On the other hand, TTs are sparse in human, cat, rabbit and guinea‐pig atrial cells (Forbes et al. 1990; Berlin, 1995; Hüser et al. 1996; Richards et al. 2011; Greiser et al. 2014). Importantly, in these cells there is a significant delay between the subsarcolemmal and central‐cellular CaT, which is due to the lack of TTs (Hüser et al. 1996; Greiser et al. 2014). Atrial cells with abundant TTs, on the other hand, have a ‘ventricular’ pattern of intracellular Ca2+ release resulting in a homogeneous CaT. Indeed, the spatio‐temporal heterogeneity of the human atrial CaT and its relation to the lack of TT in these cells was already described in a seminal study by Hatem and coworkers (Hatem et al. 1997). Importantly, the amplitudes of the subsarcolemmal and central‐cellular CaT are similar during steady‐state field stimulation in rabbit and human atrial myocytes. Ca2+ signalling silencing induces a significant reduction of the central‐cellular CaT, without affecting the amplitude of the subsarcolemmal CaT (Greiser et al. 2014). This ‘silencing’ of the central‐cellular part of the CaT also underlies the reduced whole cell Ca2+ transient seen in atrial myocytes isolated from patients with AF (Greiser et al. 2014) showing that key aspects of Ca2+ signalling silencing prevail in AF. Reduced central CaTs have been previously described in AF models in sheep and dog atrial myocytes. The reduced central CaTs in these models were due to significant TT depletion, which reduced LTCC–RyR2 pairs (Dibb et al. 2009; Lenaerts et al. 2009; Wakili et al. 2010).

Thus, in species with functionally important atrial TTs (sheep, dog, mouse), TT depletion is an important mechanism of altered Ca2+ signalling in various models of atrial remodelling. In atrial cells with sparse TTs, calcium signalling silencing reduces central CaT amplitudes independently of changes in TT abundance. Further, isolated human left atrial myocytes from the posterior left atrium, a region close to the arrhythmogenic pulmonary vein sleeves, were found to have no functionally relevant TTs in either control or AF myocytes (Greiser et al. 2014). Should this subcellular anatomy be consistent throughout the left atrium, it would strongly suggest that TT depletion is not an important mechanism in human AF, but rather that rapid rate induced Ca2+ signalling silencing underlies the reduction of the central‐cellular CaT in human AF.

Relevance of Ca2+ silencing in the natural progression of AF

Calcium signalling silencing is the first ‘anti‐arrhythmic’ adaptive mechanism induced by a feature of AF that was thought to further the arrhythmia, namely rapid atrial activation. Sustained rapid rates that develop as a precursor to the arrhythmia as episodes of paroxysmal AF prevent the development of arrhythmogenic Ca2+ instability. It follows that the Ca2+ signalling ‘phenotype’ in a specific AF patient is the sum of all changes in intracellular Ca2+ signalling. Whether arrhythmogenic Ca2+ instability or anti‐arrhythmic silencing will prevail is likely to depend on the aetiology or ‘type’ of AF (Fig. 2). Heart failure, which predisposes to AF, leads to unstable arrhythmogenic Ca2+ instability in ventricular cells (Pogwizd & Bers, 2004). It is therefore likely that unstable Ca2+ signalling contributes to the initiation of AF in heart failure. Indeed, a canine heart failure model produced unstable atrial Ca2+ signalling resulting in increased DADs (Yeh et al. 2008). Similarly, the only transgenic mice that develop spontaneous sustained AF have a cardiomyopathy induced by high [Na+]i (Wan et al. 2016), suggesting Ca2+‐based arrhythmogenesis as an underlying mechanism.

Figure 2. Schematic diagram for the proposed role of Ca2+ signalling silencing in Ca2+‐based arrhythmogenesis during the natural progression of different types of AF.

See text for details.

The effects of Ca2+ signalling silencing can persist in patients as shown in our data from human AF. The failure of the centripetal intracellular Ca2+ wave, which is a key feature of Ca2+ signalling silencing, is observed in field stimulated atrial cells from patients with persistent AF (Greiser et al. 2014). Similarly, reduced rather than enhanced spontaneous ectopic activity was reported in isolated atrial trabeculae from patients with persistent AF compared to trabeculae from patients in sinus rhythm (Christ et al. 2014).

It may well be that underlying cardiovascular disease (e.g. heart failure, ischaemic heart disease) produces a Ca2+‐based arrhythmogenic substrate and that Ca2+‐based arrhythmogenic mechanisms contribute to the initiation of AF in these patients. After the onset of AF, however, some degree of Ca2+ silencing will occur and Ca2+‐based arrhythmogenesis at this point might not further contribute to AF maintenance. Similarly, in patients without accompanying heart disease (‘lone AF’), Ca2+‐based arrhythmogenesis might not play a role in initiation and maintenance of AF (Fig. 2). Consistent with this concept is the fact that lone rapid atrial pacing or experimental AF as such has never been shown to produce an enhanced rate of atrial ectopic activity (Schotten et al. 2011).

In summary, future studies are needed that focus on the pathophysiological characteristics of different AF aetiologies. Arrhythmogenic unstable Ca2+ signalling, for example, is more likely to occur in AF developing in heart failure patients than in patients with lone atrial fibrillation, where Ca2+ signalling silencing might be dominant. Elucidating distinct changes in [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i homeostasis for different AF aetiologies will be crucial for developing ‘personalized’ therapeutic concepts for individual AF patients.

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by a Scientist Development Grant from the American Heart Association (14SDG20110054) to the author.

Biography

Maura Greiser trained in Internal Medicine/Cardiology in Aachen, where her interest in atrial fibrillation developed. She then did a PhD with Uli Schotten and Maurits Allessie in Maastricht. After that she moved to Baltimore to join Jon Lederer's group where her work continued to focus on atrial Ca2+ signalling in atrial fibrillation. She joined the faculty at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in the Department of Physiology.

References

- Berlin JR (1995). Spatiotemporal changes of Ca2+ during electrically evoked contractions in atrial and ventricular cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 269, H1165–H1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin JR, Cannell MB & Lederer WJ (1989). Cellular origins of the transient inward current in cardiac myocytes. Role of fluctuations and waves of elevated intracellular calcium. Circ Res 65, 115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers DM (2001). Excitation‐Contraction Coupling and Cardiac Contractile Force. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Carter S, Colyer J & Sitsapesan R (2006). Maximum phosphorylation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor at serine‐2809 by protein kinase a produces unique modifications to channel gating and conductance not observed at lower levels of phosphorylation. Circ Res 98, 1506–1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen‐Izu Y, McCulle SL, Ward CW, Soeller C, Allen BM, Rabang C, Cannell MB, Balke CW & Izu LT (2006). Three‐dimensional distribution of ryanodine receptor clusters in cardiac myocytes. Biophys J 91, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Lederer WJ & Cannell MB (1993). Calcium sparks: elementary events underlying excitation‐contraction coupling in heart muscle. Science 262, 740–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ T, Rozmaritsa N, Engel A, Berk E, Knaut M, Metzner K, Canteras M, Ravens U & Kaumann A (2014). Arrhythmias, elicited by catecholamines and serotonin, vanish in human chronic atrial fibrillation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 11193–11198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Despa S, Islam MA, Pogwizd SM & Bers DM (2002). Intracellular [Na+] and Na+ pump rate in rat and rabbit ventricular myocytes. J Physiol 539, 133–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibb KM, Clarke JD, Horn MA, Richards MA, Graham HK, Eisner DA & Trafford AW (2009). Characterization of an extensive transverse tubular network in sheep atrial myocytes and its depletion in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2, 482–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El‐Armouche A, Boknik P, Eschenhagen T, Carrier L, Knaut M, Ravens U & Dobrev D (2006). Molecular determinants of altered Ca2+ handling in human chronic atrial fibrillation. Circulation 114, 670–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes MS, Van Niel EE & Purdy‐Ramos SI (1990). The atrial myocardial cells of mouse heart: a structural and stereological study. J Struct Biol 103, 266–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzini‐Armstrong C, Protasi F & Ramesh V (1999). Shape, size, and distribution of Ca2+ release units and couplons in skeletal and cardiac muscles. Biophys J 77, 1528–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glukhov AV, Balycheva M, Sanchez‐Alonso JL, Ilkan Z, Alvarez‐Laviada A, Bhogal N, Diakonov I, Schobesberger S, Sikkel MB, Bhargava A, Faggian G, Punjabi PP, Houser SR & Gorelik J (2015). Direct evidence for microdomain‐specific localization and remodeling of functional L‐type calcium channels in rat and human atrial myocytes. Circulation 132, 2372–2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goette A, Arndt M, Röcken C, Spiess A, Staack T, Geller JC, Huth C, Ansorge S, Klein HU & Lendeckel U (2000). Regulation of angiotensin II receptor subtypes during atrial fibrillation in humans. Circulation 101, 2678–2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiser M, Kerfant BG, Williams GS, Voigt N, Harks E, Dibb KM, Giese A, Meszaros J, Verheule S, Ravens U, Allessie MA, Gammie JS, van der Velden J, Lederer WJ, Dobrev D & Schotten U (2014). Tachycardia‐induced silencing of subcellular Ca2+ signaling in atrial myocytes. J Clin Invest 124, 4759–4772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiser M, Lederer WJ & Schotten U (2011). Alterations of atrial Ca2+ handling as cause and consequence of atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res 89, 722–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiser M, Neuberger HR, Harks E, El‐Armouche A, Boknik P, de Haan S, Verheyen F, Verheule S, Schmitz W, Ravens U, Nattel S, Allessie MA, Dobrev D & Schotten U (2009). Distinct contractile and molecular differences between two goat models of atrial dysfunction: AV block‐induced atrial dilatation and atrial fibrillation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 46, 385–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiser M & Schotten U (2013). Dynamic remodeling of intracellular Ca2+ signaling during atrial fibrillation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 58, 134–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatem SN, Bénardeau A, Rücker‐Martin C, Marty I, de Chamisso P, Villaz M & Mercadier JJ (1997). Different compartments of sarcoplasmic reticulum participate in the excitation‐contraction coupling process in human atrial myocytes. Circ Res 80, 345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hove‐Madsen L, Llach A, Bayes‐Genís A, Roura S, Rodriguez Font E, Arís A & Cinca J (2004). Atrial fibrillation is associated with increased spontaneous calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in human atrial myocytes. Circulation 110, 1358–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hüser J, Lipsius SL & Blatter LA (1996). Calcium gradients during excitation‐contraction coupling in cat atrial myocytes. J Physiol 494, 641–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ & Levy D (1998). Prevalence, incidence, prognosis, and predisposing conditions for atrial fibrillation: population‐based estimates. Am J Cardiol 82, 2N–9N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhof P, Breithardt G, Aliot E, Al Khatib S, Apostolakis S, Auricchio A, Bailleul C, Bax J, Benninger G, Blomstrom‐Lundqvist C, Boersma L, Boriani G, Brandes A, Brown H, Brueckmann M, Calkins H, Casadei B, Clemens A, Crijns H, Derwand R, Dobrev D, Ezekowitz M, Fetsch T, Gerth A, Gillis A, Gulizia M, Hack G, Haegeli L, Hatem S, Hausler KG, Heidbuchel H, Hernandez‐Brichis J, Jais P, Kappenberger L, Kautzner J, Kim S, Kuck KH, Lane D, Leute A, Lewalter T, Meyer R, Mont L, Moses G, Mueller M, Munzel F, Nabauer M, Nielsen JC, Oeff M, Oto A, Pieske B, Pisters R, Potpara T, Rasmussen L, Ravens U, Reiffel J, Richard‐Lordereau I, Schafer H, Schotten U, Stegink W, Stein K, Steinbeck G, Szumowski L, Tavazzi L, Themistoclakis S, Thomitzek K, Van Gelder IC, von Stritzky B, Vincent A, Werring D, Willems S, Lip GY & Camm AJ (2013). Personalized management of atrial fibrillation: Proceedings from the fourth Atrial Fibrillation competence NETwork/European Heart Rhythm Association consensus conference. Europace 15, 1540–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk MM, Izu LT, Chen‐Izu Y, McCulle SL, Wier WG, Balke CW & Shorofsky SR (2003). Role of the transverse‐axial tubule system in generating calcium sparks and calcium transients in rat atrial myocytes. J Physiol 547, 441–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenaerts I, Bito V, Heinzel FR, Driesen RB, Holemans P, D'hooge J, Heidbüchel H, Sipido KR & Willems R (2009). Ultrastructural and functional remodeling of the coupling between Ca2+ influx and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release in right atrial myocytes from experimental persistent atrial fibrillation. Circ Res 105, 876–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zima AV, Sheikh F, Blatter LA & Chen J (2005). Endothelin‐1‐induced arrhythmogenic Ca2+ signaling is abolished in atrial myocytes of inositol‐1,4,5‐trisphosphate (IP3)‐receptor type 2‐deficient mice. Circ Res 96, 1274–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipp P, Laine M, Tovey SC, Burrell KM, Berridge MJ, Li W & Bootman MD (2000). Functional InsP3 receptors that may modulate excitation‐contraction coupling in the heart. Curr Biol 10, 939–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayyas F, Niebauer M, Zurick A, Barnard J, Gillinov AM, Chung MK & Van Wagoner DR (2010). Association of left atrial endothelin‐1 with atrial rhythm, size, and fibrosis in patients with structural heart disease. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 3, 369–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neef S, Dybkova N, Sossalla S, Ort KR, Fluschnik N, Neumann K, Seipelt R, Schöndube FA, Hasenfuss G & Maier LS (2010). CaMKII‐dependent diastolic SR Ca2+ leak and elevated diastolic Ca2+ levels in right atrial myocardium of patients with atrial fibrillation. Circ Res 106, 1134–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien F, Venturi E & Sitsapesan R (2015). The ryanodine receptor provides high throughput Ca2+‐release but is precisely regulated by networks of associated proteins: a focus on proteins relevant to phosphorylation. Biochem Soc Trans 43, 426–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson E, Jackman WM, Beckman KJ, Lazzara R, Lockwood D, Scherlag BJ, Wu R & Po S (2007). Spontaneous pulmonary vein firing in man: relationship to tachycardia‐pause early afterdepolarizations and triggered arrhythmia in canine pulmonary veins in vitro. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 10, 1067–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogwizd SM & Bers DM (2004). Cellular basis of triggered arrhythmias in heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc Med 14, 61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulet C, Wettwer E, Grunnet M, Jespersen T, Fabritz L, Matschke K, Knaut M & Ravens U (2015). Late sodium current in human atrial cardiomyocytes from patients in sinus rhythm and atrial fibrillation. PLoS One 10, e0131432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards MA, Clarke JD, Saravanan P, Voigt N, Dobrev D, Eisner DA, Trafford AW & Dibb KM (2011). Transverse (t‐) tubules are a common feature in large mammalian atrial myocytes including human. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301, H1996–H2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotten U, Verheule S, Kirchhof P & Goette A (2011). Pathophysiological mechanisms of atrial fibrillation: a translational appraisal. Physiol Rev 91, 265–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soeller C & Cannell MB (1999). Examination of the transverse tubular system in living cardiac rat myocytes by 2‐photon microscopy and digital image‐processing techniques. Circ Res 84, 266–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sossalla S, Kallmeyer B, Wagner S, Mazur M, Maurer U, Toischer K, Schmitto JD, Seipelt R, Schöndube FA, Hasenfuss G, Belardinelli L & Maier LS (2010). Altered Na+ currents in atrial fibrillation effects of ranolazine on arrhythmias and contractility in human atrial myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol 55, 2330–2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessier S, Karczewski P, Krause EG, Pansard Y, Acar C, Lang‐Lazdunski M, Mercadier JJ & Hatem SN (1999). Regulation of the transient outward K+ current by Ca2+/calmodulin‐dependent protein kinases II in human atrial myocytes. Circ Res 85, 810–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vest JA, Wehrens XH, Reiken SR, Lehnart SE, Dobrev D, Chandra P, Danilo P, Ravens U, Rosen MR & Marks AR (2005). Defective cardiac ryanodine receptor regulation during atrial fibrillation. Circulation 111, 2025–2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt N, Li N, Wang Q, Wang W, Trafford AW, Abu‐Taha I, Sun Q, Wieland T, Ravens U, Nattel S, Wehrens XH & Dobrev D (2012). Enhanced sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak and increased Na+‐Ca2+ exchanger function underlie delayed afterdepolarizations in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. Circulation 125, 2059–2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakili R, Yeh YH, Qi XY, Greiser M, Chartier D, Nishida K, Maguy A, Villeneuve LR, Boknik P, Voigt N, Krysiak J, Kääb S, Ravens U, Linke WA, Stienen GJ, Shi Y, Tardif JC, Schotten U, Dobrev D & Nattel S (2010). Multiple potential molecular contributors to atrial hypocontractility caused by atrial tachycardia remodeling in dogs. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 3, 530–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan E, Abrams J, Weinberg RL, Katchman AN, Bayne J, Zakharov SI, Yang L, Morrow JP, Garan H & Marx SO (2016). Aberrant sodium influx causes cardiomyopathy and atrial fibrillation in mice. J Clin Invest 126, 112–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wier WG, Cannell MB, Berlin JR, Marban E & Lederer WJ (1987). Cellular and subcellular heterogeneity of [Ca2+]i in single heart cells revealed by fura‐2. Science 235, 325–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao B, Jiang MT, Zhao M, Yang D, Sutherland C, Lai FA, Walsh MP, Warltier DC, Cheng H & Chen SR (2005). Characterization of a novel PKA phosphorylation site, serine‐2030, reveals no PKA hyperphosphorylation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor in canine heart failure. Circ Res 96, 847–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada J, Ohkusa T, Nao T, Ueyama T, Yano M, Kobayashi S, Hamano K, Esato K & Matsuzaki M (2001). Up‐regulation of inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate receptor expression in atrial tissue in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 37, 1111–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh YH, Wakili R, Qi XY, Chartier D, Boknik P, Kääb S, Ravens U, Coutu P, Dobrev D & Nattel S (2008). Calcium‐handling abnormalities underlying atrial arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in dogs with congestive heart failure. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 1, 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]