Abstract

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is a T cell-mediated autoimmune disease that causes inflammation around anagen-phase hair follicles. Insufficient levels of vitamin D have been implicated in a variety of autoimmune diseases.

Aim

To investigate the status of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) in patients with AA, serum 25(OH)D concentrations were compared between AA patients and healthy controls and thus determine if a possible association exists between serum 25(OH)D levels and AA.

Material and methods

The study comprising 41 patients diagnosed with AA and 32 healthy controls was conducted between October 2010 and March 2011. The serum vitamin D levels of the study group were determined by high performance liquid chromatography. Serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, and parathyroid hormone were also evaluated.

Results

The study was based on 41 patients aged between 20 and 50 (mean: 32.8 ±7.5). The control group included 32 healthy persons aged between 20 and 51 (mean: 32.7 ±7.5). Serum 25(OH)D levels in patients with AA ranged from 5.0 to 38.6 ng/ml with a mean of 8.1 ng/ml. Serum 25(OH)D levels in healthy controls ranged from 3.6 to 38.5 ng/ml with a mean of 9.8 ng/ml. There was no statistically significant difference in the serum vitamin D level between AA patients and healthy controls (p > 0.05).

Conclusions

Deficient serum 25(OH)D levels are present in patients with AA. However, considering the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in Turkey, no difference was noted between AA patients and controls.

Keywords: alopecia areata, autoimmunity, vitamin D

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is a tissue-specific autoimmune T cell-mediated disease. The exact pathogenesis of AA is not fully understood. However, recent available evidence supports an autoimmune targeting of hair follicles. The histological feature of AA is lymphocyte infiltration around and within affected hair follicles. Also macrophages and Langerhans cells around and within the hair follicles have been observed [1, 2]. Alopecia areata is an autoimmune disease and many autoimmune conditions are associated with reduced vitamin D levels, including rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus and multiple sclerosis [3].

Vitamin D is a fat soluble steroid synthesized in the skin from 7-dehydrocholesterol (as a hormone) or ingested with food (as a vitamin). It has a role in mediating the normal function of both the innate and adaptive immune systems and initiates biological responses via binding to the vitamin D receptor (VDR) that is widely distributed in most tissues. Vitamin D has been implicated in processes that may trigger or exacerbate autoimmunity [4, 5]. Various studies report that vitamin D levels are associated with the incidence and/or severity of some autoimmune diseases including multiple sclerosis, lupus erythematosus, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and rheumatoid arthritis [6–9]. Also vitamin D analogues are effective topical therapies for cutaneous autoimmune conditions including psoriasis and vitiligo [10].

Aim

The aim of this study was to evaluate the status of vitamin D in patients with AA. Because of the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in our geographic area, we also evaluated the levels in a healthy control group and compared the two groups between October 2010 and March 2011. In order to minimize the effect of seasonal changes on vitamin D levels, the study was conducted during the fall and winter months.

Material and methods

This study was carried out in the Department of Dermatology with the approval of the Hospital Ethics Committee. Patients and controls had to sign informed consent, according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients

This study was conducted in the Department of Dermatology of the Turgut Ozal University Hospital, Ankara, Turkey from October 2010 to March 2011. Forty-one patients with AA (26 males and 15 females) and 32 healthy control subject (18 males and 14 females) were studied. Exclusion from analysis was based upon oral vitamin D supplementation; major cardiovascular, liver, kidney or digestive disease; treatment for AA 1 month before testing; or refusal to have laboratory testing.

Patient demographics including gender, age, history of AA onset, main site of involvement, duration and progression of the disease, Fitzpatrick skin phenotype, and personal and family history of comorbid autoimmune diseases were acquired during patient interviews in the department.

Methods

We evaluated the levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D), calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and parathyroid hormone (PTH). Vitamin D was assessed as deficient if 25(OH)D levels were < 20 ng/ml, insufficient if between 20 and 30 ng/ml, and sufficient if > 30 ng/ml.

Assays

Serum calcium, phosphorus, and ALP levels were measured with a spectrophotometric device using a commercial kit (Roche Integra 800). Vitamin D was quantified by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Vertical Mark of Column device by UFLC-SHIMADZU, with features by Verti SepTM GES C18HPLC Column, ImmuChrom GmbH lot number VD-130218F). Serum levels of PTH were measured by a chemiluminescence immunoassay device (Siemens Centaur XP).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows, version 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, United States). Normal or non-normal distributions of continuous variables were determined by the Shapiro Wilk test. The mean differences between groups were compared by using the Student’s t-test; otherwise, the Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis tests were used according to the number of independent groups for the comparisons of median values. When the p-value from the Kruskal-Wallis test statistics is statistically significant, the Conover’s non-parametric multiple comparison test was used to determine which group differs from the others.

Categorical data were analysed by the Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact test (where applicable). The degree of association between the duration of symptoms and vitamin D levels was evaluated by Spearman’s correlation analysis. Multiple Logistic Regression analysis was applied for determining the best predictor(s) to discriminate between case and control groups. Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals for each independent variable were also calculated. A value of p less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The study included 41 patients (26 males, 15 females) aged between 20 and 50 (mean: 32.8 ±7.5). The control group included 32 healthy people (18 males, 14 females) aged between 20 and 51 (mean: 32.7 ±7.5). There was no statistically significant difference between patient and control groups with respect to the mean age. Fifteen patients had a single patch and 26 patients had multiple patches; all lesions were on the scalp (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data of the patient and control groups

| Variables | Controls (n = 32) | Patients (n = 41) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 32.7 ±7.5 | 32.8 ±7.5 | 0.961† |

| Gender: | 0.535‡ | ||

| Male | 18 (56.3%) | 26 (63.4%) | |

| Female | 14 (43.7%) | 15 (36.6%) | |

| Fitzpatrick skin phenotype: | 0.587‡ | ||

| Type II | 4 (12.5%) | 8 (19.5%) | |

| Type III | 20 (62.5%) | 21 (51.2%) | |

| Type IV | 8 (25.0%) | 12 (29.3%) | |

| Vitamin D [ng/ml] | 8.1 (5.0–38.6) | 9.8 (3.6–38.5) | 0.508¶ |

| Vitamin D [ng/ml]: | |||

| ≥ 30 | 1 (3.1%) | 2 (4.9%) | 1.000# |

| 21–29 | 1 (3.1%) | 4 (9.8%) | 0.377# |

| < 20 | 30 (93.8%) | 35 (85.3%) | 0.453# |

| < 10 | 19 (59.4%) | 22 (53.7%) | 0.479# |

| Calcium | 9.4 ±0.44 | 9.4 ±0.47 | 0.954† |

| Phosphorus | 3.4 ±0.43 | 3.4 ±0.56 | 0.678† |

| ALP | 71.3 ±20.0 | 78.9 ±18.8 | 0.101† |

| PTH | 57.1 (19.8–247.0) |

64.5 (22.7–143.5) |

0.415¶ |

Student’s t test,

Pearson’s χ2,

Mann-Whitney U test,

Fisher’s exact test.

Among the 41 patients with AA, a family history of AA was present in 12 (29.3%) patients; Hashimoto thyroiditis was found in 4 (9.8%) patients; type I diabetes mellitus occurred in 6 (14.6%) patients, and rheumatoid arthritis was found in 2 (4.9%) patients. An autoimmune disease was present in 4 (9.8%) patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients with AA (n = 41)

| Variables | Result |

|---|---|

| Duration of alopecia areata [months]: | |

| < 1 | 13 (31.7%) |

| 1–3 | 10 (24.4%) |

| 4–6 | 5 (12.2%) |

| > 6 | 13 (31.7%) |

| Involvement: | |

| Single | 15 (36.6%) |

| Multiple | 26 (63.4%) |

| Comorbid autoimmune disease: | 4 (9.8%) |

| Hashimoto thyroiditis | 4 (9.8%) |

| Family history: | 12 (29.3%) |

| Hashimoto thyroiditis | 4 (9.8%) |

| Type I diabetes mellitus | 6 (14.6%) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 (4.9%) |

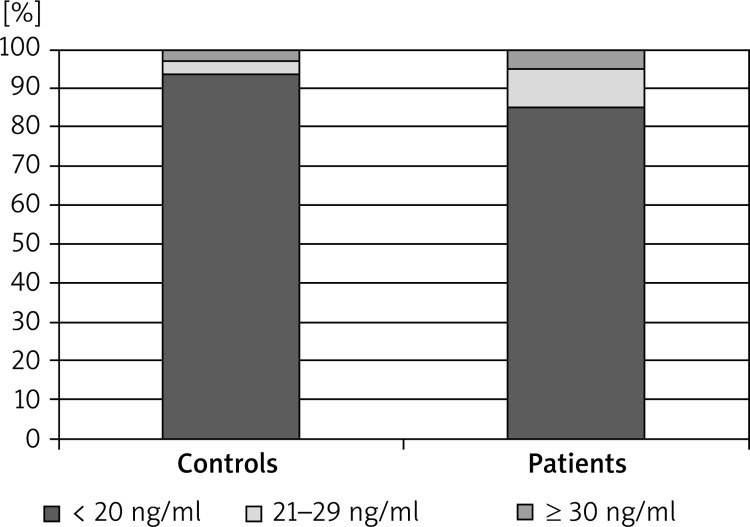

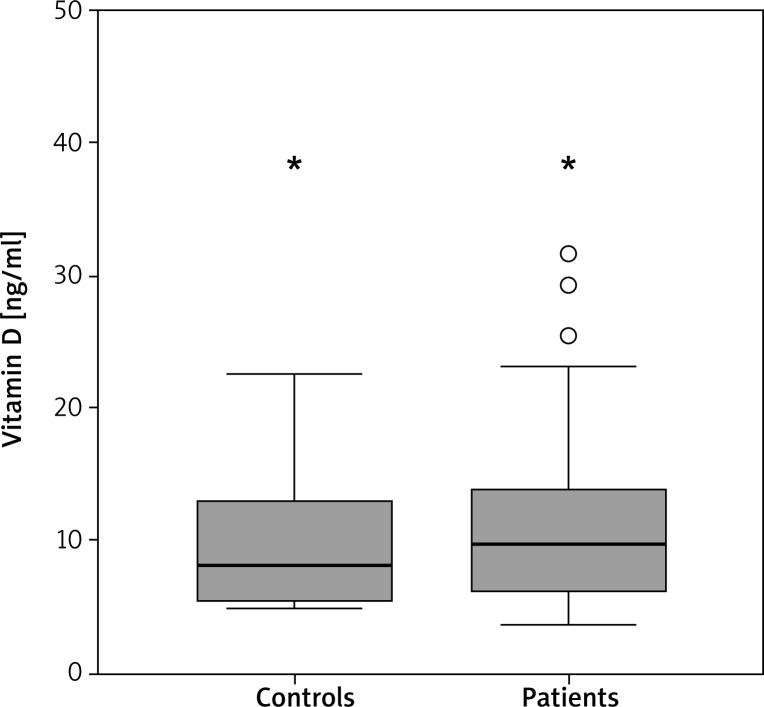

Serum 25(OH)D levels in patients with AA ranged from 5.0 to 38.6 ng/ml with a mean of 8.1 ng/ml. Overall, 93.8% had a vitamin D deficiency, 3.1% had a vitamin D insufficiency, and 3.1% had sufficient levels of vitamin D. Serum 25(OH)D levels in the healthy control group ranged from 3.6 to 38.5 ng/ml with a mean of 9.8 ng/ml. Overall, 85.3% had a deficiency, 9.8% had an insufficiency, and 4.9% had sufficient levels of vitamin D. There was no statistically significant difference in the serum vitamin D level between AA patients and healthy controls (p > 0.05) (Figures 1 and 2). When the proportion of men and women in the study groups was investigated, there was no statistically significant difference in 25(OH)D levels (p > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Comparison of serum 25(OH)D levels between alopecia areata patients and controls

Figure 2.

Comparison of vitamin D levels between controls and patients. The horizontal lines in the middle of each box indicates the median, while the top and bottom borders of the box mark the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers above and below the box mark the maximum and minimum vitamin D levels

The serum 25(OH)D levels under 10 ng/ml were observed in 53.7% of patients and 59.4% of the control group. There was no statistically significant difference in the serum vitamin D levels under 10 ng/ml between AA patients and controls (p > 0.05).

There was no statistically significant difference between the patient and control group with the respect to the levels of calcium, phosphorus, ALP, and PTH (p > 0.05).

Results of the logistic regression models are presented in Table 3. The logistic regression analysis showed no significant effect of age, gender, or skin type on vitamin D status.

Table 3.

The results of multivariate analysis

| Variables | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 0.986 | 0.922–1.054 | 0.675 |

| Gender: | |||

| Female | 1.000 | – | – |

| Male | 0.819 | 0.254–2.636 | 0.737 |

| Fitzpatrick skin phenotype: | |||

| Type II | 1.000 | – | – |

| Type III | 0.568 | 0.138–2.347 | 0.435 |

| Type IV | 0.627 | 0.132–2.979 | 0.557 |

| Vitamin D | 1.036 | 0.961–1.116 | 0.359 |

| Calcium | 0.823 | 0.259–2.619 | 0.741 |

| Phosphorus | 1.410 | 0.497–3.995 | 0.518 |

| ALP | 1.024 | 0.994–1.054 | 0.117 |

| PTH | 0.999 | 0.984–1.014 | 0.901 |

Discussion

The hair follicle is a highly hormone-sensitive organ [2]. Vitamin D is a hormone that plays an important role in regulation of calcium homeostasis, both in cell growth and differentiation, as well as immune system regulation [4, 5]. Based on biological effects, a normal 25(OH)D level is ≥ 30 ng/dl. Vitamin D deficiency is being increasingly recognised worldwide due to differences in the dietary intake of vitamin D, varying durations of exposure to sunlight or the use of supplements, the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency shows different patterns across various populations [11]. Various studies report that vitamin D levels are associated with the incidence and/or severity of some autoimmune disorders including type I diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, and inflammatory bowel disease [6]. Recent studies have indicated that vitamin D deficiency can be a significant risk factor for AA occurrence [12–15].

A study by Yılmaz et al. revealed low serum 25(OH)D levels in patients with AA compared with healthy controls [12]. Mahamid et al. found a strong correlation between AA and vitamin D deficiency in a study of 23 patients [13]. In another study, Aksu et al. showed that serum 25(OH)D levels were inversely correlated with disease severity of AA [14]. In a study based on 156 patients with AA and 148 controls, d’Ovidio et al. found that the insufficiency or deficiency of 25(OH)D was not significantly different between patients with AA and controls. However, a deficiency in 25(OH)D was present in 42.4% of patients, which was significantly higher than the 29.5% observed in healthy controls. In addition, the decreased level of 25(OH)D was not correlated with a pattern or extent of hair loss [15].

Our results do not agree with previous reports demonstrating the association between AA and vitamin D deficiency. In our study, we found that patients had a deficiency of 25(OH)D, but there was no statistically significant difference in the serum vitamin D levels between AA patients and healthy controls (p > 0.05). This may be due to the universal tendency toward lower values of 25(OH)D in our geographical area. Hekimsoy et al. found a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency (74.9%) and an insufficiency (13.8%) in a population-based sample in the Aegean region of Turkey [16]. In a study on 1010 paediatric patients in Turkey, Orun et al. found that the deficiency (24.3%) and insufficiency (16.5%) of 25(OH)D were frequent in childhood, especially in the adolescent period [17]. Van der Meer et al. demonstrated that vitamin D status in the Turkish population varied widely in Turkey, according to sunscreen usage, insufficient intake of vitamin D in the diet, darker skin colours, and the habit of using clothing to cover most of the body [18].

Vitamin D is recognized as the sunlight vitamin. The major source of this vitamin is skin synthesis of vitamin D. More than 90% of the vitamin D requirement for most people comes from casual exposure to sunlight. Natural dietary sources of vitamin D are limited [19]. In Middle Eastern populations who live in sunny climates, very low vitamin D levels have been reported, particularly populations from Lebanon, Iran, Jordan and Turkey [20–22]. This may be due to common environmental factors such as latitude, seasonality, pollution, customs or cultural issues, diet, or fortified-food policies. In addition, individual sociocultural and behavioural factors such as clothing, use of sunscreens with high sun protection factor, sunbathing habits, skin pigmentations, time spent outdoors, and insufficient playgrounds may affect the status of serum vitamin D levels.

Our study has a few limitations. The study sample of 41 healthy individuals was small and the fact that blood samples were collected only once during the late fall and winter months between October and March. It would be useful to evaluate patients at different times of the year to study seasonal variations. Multicentre studies from different geographic areas around Turkey are needed.

Conclusions

We found decreased serum 25(OH)D levels in patients with AA, but there was no statistically significant difference in the serum vitamin D level between AA patients and healthy controls. Further studies are needed to clarify the association between a deficiency of 25(OH)D and AA. But still in our opinion, we recommend screening blood vitamin D levels in AA patients and if deficient, adding oral vitamin D to the AA treatment protocol.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Alkhalifah A, Alsantali A, Wang E, et al. Alopecia areata update: part I. Clinical picture, histopathology, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:177–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilhar A, Kalish RS. Alopecia areata: a tissue specific autoimmune disease of the hair follicle. Autoimmun Rev. 2006;5:64–9. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kriegel MA, Manson JE, Costenbader KH. Does vitamin D affect risk of developing autoimmune disease? A systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;40:512–31. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hewison M. Vitamin D and the immune system: new perspectives on an old theme. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39:365–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LoPiccolo MC, Lim HW. Vitamin D in health and disease. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2010;26:224–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2010.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agmon-Levin N, Shoenfeld Y. Prediction and prevention of autoimmune skin disorder. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009;301:57–64. doi: 10.1007/s00403-008-0889-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergler-Czop B, Brzezińska-Wcisło L. Serum vitamin D level – the effect on the clinical course of psoriasis. Adv Dermatol Allergol. 2016;33:445–9. doi: 10.5114/ada.2016.63883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karagün E, Ergin C, Baysak S, et al. The role of serum vitamin D levels in vitiligo. Adv Dermatol Allergol. 2016;33:300–2. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2016.59507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kucharska A, Szmurło A, Sińska B. Significance of diet in treated and untreated acne vulgaris. Adv Dermatol Allergol. 2016;33:81–6. doi: 10.5114/ada.2016.59146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amano H, Abe M, Ishikawa O. First case report of topical tacalcitol for vitiligo repigmentation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:262–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lips P, Hosking D, Lippuner K, et al. The prevalance of vitamin D inadequacy among women with osteoporosis: an international epidemiological investigation. J Intern Med. 2006;260:245–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yılmaz N, Serarslan G, Gokce C. Vitamin D concentrations are decreased in patients with alopecia areata. Vitam Trace Elem. 2012;1:105–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahamid M, Abu-Elhija O, Samamra M, et al. Association between vitamin D levels and alopecia areata. Isr Med Assoc J. 2014;16:367–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aksu Cerman A, Sarikaya Solak S, Kivanc Altunay I. Vitamin D deficiency in alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1299–304. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.d’Ovidio R, Vessio M, d’Ovidio FD. Reduced level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in chronic/relapsing alopecia areata. Dermatoendocrinol. 2013;5:271–3. doi: 10.4161/derm.24411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hekimsoy Z, Dinç G, Kafesçiler S, et al. Vitamin D status among adults in the Aegean region of Turkey. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:782. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orun E, Sezer S, Kanburoglu MK, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in healthy children and adolescent. Clin Invest Med. 2015;38:E261–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van der Meer IM, Middelkoop BJ, Boeke AJ, Lips P. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among Turkish, Moroccan, Indian and Sub-Sahara African populations in Europe and their countries of origin: overview. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:1009–21. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1279-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holick MF. Sunlight and vitamin D for bone health and prevention of autoimmune diseases, cancers, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(6 Suppl):1678S–88S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1678S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gannagé-Yared MH, Chemali R, Yaacoub N, et al. Hypovitaminosis D in a sunny country: relation to lifestyle and bone markers. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:1856–62. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.9.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mishal AA. Effects of different dress styles on vitamin D levels in healthy young Jordanian women. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:931–5. doi: 10.1007/s001980170021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lips P. Vitamin D status and nutrition in Europe and Asia. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:620–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]