Abstract

To evaluate a new way of meeting the growing demand for training prospective resource parents, our study compared the efficacy of a blended online and in-person approach with a traditional classroom-only approach. Findings based on a sample of 111 resource parent prospects showed significantly greater gains in knowledge from pre- to posttest for the blended approach over the classroom-only approach. The blended approach also produced dramatically lower dropout rates during preservice training. Both groups made significant gains in parenting awareness from pre to post, but those gains were greater for the classroom-only approach. Post hoc analyses examined this finding more closely. Satisfaction with training was comparably high for both groups. Gains in knowledge and awareness were sustained at a 3-month follow-up assessment.

Keywords: adoptive parents, blended training, foster parents, hybrid training, kinship caregivers, preservice training, randomized trial, parent assessment, resource parents, web-based training

State and county child welfare agencies across the United States are struggling with meeting the ongoing demands of providing quality preservice training for prospective resource parents, a large group that includes non-relative (traditional) foster parents, relative (kinship) foster parents, and pre-adoptive parents (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2012). The goals of preservice training are challenging: Agencies must provide potential resource parents with the core information they will need to understand children with special needs; parenting strategies for children who have experienced trauma; and an understanding of a child's need for safety, permanency, and well-being. The training period is also a time for mutual assessment, when the potential caregiving family assesses their willingness, ability, and resources (Petras & Pasztor, 2016), and the agency considers whether the family has the capacity to meet the needs of children in care.

The Demand for Preservice Training

The demand for preservice training for all three types of prospective resource parents is unremitting. In FY2014, non-relative foster families were caring for 190,454 children (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015). The high rate of attrition among this group means an estimated 150,000 prospective resource parents have to be recruited and trained each year (FosterParentCollege.com, 2015). Relative foster families were caring for another 120,334 children in FY2014 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015). The need to train this group of parents continues to grow due to national initiatives promoting the placement of children with relatives (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2013; Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008). The demand for training adoptive parents is also high, given that more than 50,000 foster children, many of whom have special needs, are adopted per year with public child welfare agency involvement (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015).

Barriers to Completion of Traditional Preservice Training

Although preservice training is critically important, the burden it imposes on prospective resource families is substantial. The most popular curriculums used for this purpose require up to 39 hours of in-person attendance (Grimm, 2003; National Resource Center for Family-Centered Practice and Permanency Planning, 2008). In-person training also poses hardships and inconveniences related to travel costs, scheduling, child care, and time off of work. The inflexibility of scheduled classroom training requirements can be off-putting and discourage general applicants from completing training. In some locales, for instance (Wilson, Katz, & Geen, 2005), prospective resource parents were informed that if they missed more than one class, they would need to retake the training from the beginning. Among those who decided to drop out of training—and hence, to not adopt—one of the top reasons given was the duration of the process (18%), which includes the extensive preservice training requirements (Wilson et al., 2005). Non-completion has thus been a common problem for traditional preservice training for a variety of reasons (Groza, Riley-Behringer, Cage, & Lodge, 2012).

Blended Training

An innovative instructional approach used in a variety of settings is variously called “web-enhanced,” “hybrid,” or “blended” training. These terms all refer to a combination of electronic or web-based and face-to-face education. Blended training—the term applied to the intervention in this study—melds the advantages of both approaches (Bonk & Graham, 2006; Clark & Mayer, 2011). The increased convenience of online training is readily apparent and often cited by students and trainees (Güzer & Caner, 2014). One central reason users like blended training is that the online portion allows time and place scheduling to be highly flexible (Melton, Bland, & Chopak-Foss, 2009). The effectiveness of blended training has been shown to match or surpass that of traditional, classroom approaches (Means, Toyama, Murphy, & Baki, 2013). In fact, on specific variables such as satisfaction, motivation, dropout rate, and knowledge retention, blended training has been found to be superior (Güzer & Caner, 2014; Hughes, 2007; Melton et al., 2009).

A blended approach should be well suited for the preservice training needs of prospective resource parents and the agencies responsible for training them. Specifically, parents are able to view and interact with core, knowledge-based and awareness-raising parts of the training online, allowing them to train at home and thereby eliminating the need for child care and travel. Fewer in-person training sessions reduces the inconveniences and costs associated with attendance, while still giving parents opportunities to meet and interact with other prospective resource parents, have direct contact with agency staff, and participate in the mutual assessment process. For agencies, the online instructional modules assure standardized delivery of core information by experts. Providing fewer face-to-face sessions allows agencies to reduce the commitment of staff time and other resources to training, while still permitting them to assess prospective resource parents in person and to present mandated and agency-specific information. Given the apparent advantages of blended training compared to the traditional classroom approach, in the current study we examine the effectiveness of a blended approach at increasing parenting knowledge and awareness. We also examine whether a blended approach improves trainees' satisfaction with the training they receive.

Methods

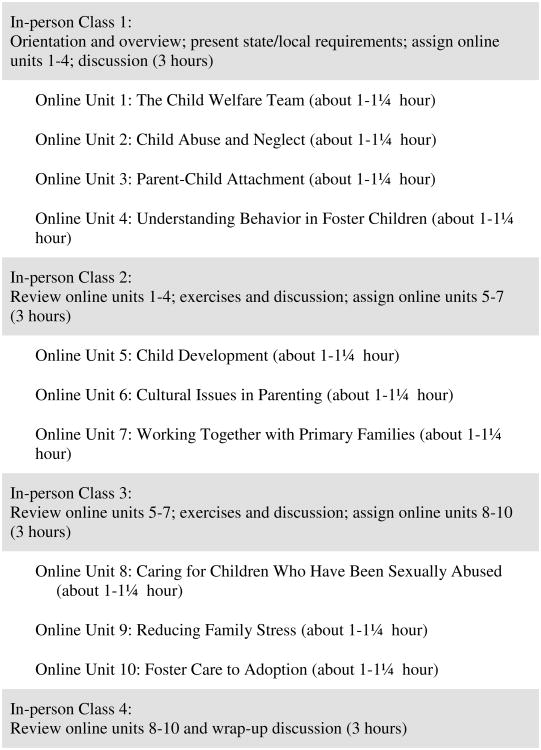

Our study, conducted in the Portland, Oregon metropolitan area, compared the efficacy of the Blended Preservice Training curriculum, which combines in-person meetings and online courses, with Foundations in Fostering, Adopting, or Caring for Relative Children Training, a traditional classroom-only curriculum. For the study, the Blended curriculum included four 3-hour classroom meetings that addressed specific requirements for training in Oregon and that gave parents and agencies the opportunity for mutual assessment. It also included 10 self-paced online units, updated and adapted for the web by Northwest Media, Inc. from a classroom curriculum originally developed by the Institute for Human Services (IHS) for the Ohio Child Welfare Training Program. Betsy Keefer Smalley, co-author of the IHS curriculum, collaborated with Northwest Media on the adaptation and assured that the Blended curriculum was complete and comparable to the original. The online courses, eight of which were co-authored and either presented or co-presented by Keefer Smalley, consisted of video presentations, story narratives, interactive exercises, review questionnaires, and printable supplements. (See Figure 1 for the topics covered in the Blended training's in-person and online classes.)

Figure 1. Flow of Blended Training's In-person Classes and Online Units.

Note. Study participants in the Blended group had 12 hours of in-person training and an average of 10-12½ hours of online training (depending on the rate at which they completed the online classes' interactive exercises).

The classroom-style Foundations curriculum was developed by Portland State University Child Welfare Partnership and the State of Oregon Department of Human Services (DHS). Currently used for preservice training throughout Oregon, the Foundations training consists of eight 3-hour meetings and covers the following topics: 1) Oregon DHS System Orientation, 2) The Importance of Birth Families, 3) Child Development and the Impact of Abuse, 4) Sexual Abuse, 5) Behavior Management, 6) Valuing the Child's Heritage, 7) Working with the Child's Family, and 8) Next Steps for Foster Parents, Relative Caregivers, and Prospective Adoptive Parents.

Although the organization of material for the Blended and Foundations programs is different, a careful review established that the content of the two programs substantially overlapped. The review was conducted in preparation for the study by Maureen Lovejoy, an Oregon DHS trainer for over 18 years who had detailed knowledge of the Foundations program and who had contracted with NWM to serve as the study administrator and lead trainer. She viewed all 10 of the Blended curriculum's online courses several times and read all online supportive course materials. In comparing the Blended and Foundations programs, Lovejoy determined that there were several topics missing from the Blended training curriculum that were important to DHS training and certification staff in the participating counties. Therefore, Blended in-person meetings 2-4 were modified to include the following missing topics: Medication Management, Introduction to Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders, Caring for LGBTQ Youth, Addiction and Family Systems, and Out-of-Home-Care Assessments (the Oregon process).

As part of her review, Lovejoy also compared the terminology used in the two curriculums and examined items in the study questionnaires to ensure that language and content were appropriate for participants in both the Blended and Foundations trainings. Since the questionnaires were originally developed based on the Blended curriculum, she identified terms in them that would need to be adjusted, e.g., “kinship care” is the term used in the Blended curriculum, whereas “relative care” is used in Foundations. Such differences in terminology between the two programs were explained by the trainers during the study's in-person meetings.

At the end of her review, Lovejoy concluded that the two preservice training programs, although not identical in the information delivered, tapped essentially similar content areas and were generally comparable. Based on Lovejoy's review, Oregon DHS agreed to participate in our study and to accept treatment group participants' completion of the Blended training in lieu of the Foundations training for purposes of certifying them as resource parents. We therefore proceeded with arrangements to conduct our study comparing the relative efficacy of the two curriculums at increasing trainees' knowledge and awareness of core issues, as well as participant satisfaction.

Sample

Our final sample for the pre-post study included 111 prospective resource (foster, adoptive, and kinship) parents. The mean age of study participants was 40.2 years (SD = 10.4). Sixty-two percent of the sample was female. Racially, 85% were White, 5% were Black or African American, 2% were American Indian or Alaska Native, 7% were more than one race, and 2% were other or unknown; ethnically, 6% identified as Hispanic or Latino.

Of the 111 study participants, there were 57 in the treatment group (Blended training), and 54 in the comparison group (Foundations training). The two groups were similar on age, gender, ethnicity, and race. In terms of education, the treatment group was more likely to have participants with “some college” or “AA degree” as their highest level of education, whereas the comparison group had more participants with a bachelor's degree. The comparison group also had more participants in the $70,000 or over income level for the family.

Eighty-four participants in the pre-post study later completed a 3-month follow-up assessment (47 in the treatment group and 37 in the comparison group). In the follow-up sample, the only significant demographic difference between the groups was on age, with the treatment group being significantly older than the comparison group. (See Table 1 for the sample demographics by group for both the pre-post and follow-up study samples.)

Table 1. Demographics for the Pre-Post and Follow-up Study Samples, by Study Group.

| Pre-Post Study Sample | Follow-up Study Sample | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Treatment Group Blended Training n = 57 | Comparison Group Foundations Training n = 54 | Treatment Group Blended Training n = 47 | Comparison Group Foundations Training n = 37 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

|

|

|||||||||

| Age * | 41.9 | 10.8 | 38.3 | 9.8 | 42.5 | 11.0 | 36.8 | 8.5 | |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

|

|

|||||||||

| Gender | Female | 34 | 59.6 | 35 | 64.8 | 29 | 61.7 | 25 | 67.6 |

| Male | 23 | 40.4 | 19 | 35.2 | 18 | 38.3 | 12 | 32.4 | |

| Ethnic Background | Hispanic/Latino | 1 | 1.8 | 5 | 9.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 8.1 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 52 | 91.2 | 48 | 88.9 | 44 | 93.6 | 34 | 91.9 | |

| Unknown | 4 | 7.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 6.4 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Hispanic and Not Hispanic | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Race | White | 47 | 82.5 | 47 | 87.0 | 39 | 83.0 | 32 | 86.5 |

| Black | 4 | 7.0 | 1 | 1.9 | 3 | 6.4 | 1 | 2.7 | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 | 3.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| More than 1 race | 3 | 5.3 | 5 | 9.3 | 3 | 6.4 | 4 | 10.8 | |

| Other or Unknown | 1 | 1.8 | 1 | 1.9 | 1 | 2.1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Education | High School or Less | 7 | 12.3 | 6 | 11.1 | 7 | 14.9 | 3 | 8.1 |

| Some College or AA Degree * | 31 | 54.4 | 19 | 35.2 | 23 | 49.0 | 13 | 35.1 | |

| BA/BS Degree * | 10 | 17.5 | 20 | 37.0 | 8 | 17.0 | 13 | 35.1 | |

| MA/MS or PhD | 9 | 15.8 | 9 | 16.7 | 9 | 19.2 | 8 | 21.6 | |

| Income | Under $30,000 | 7 | 12.3 | 3 | 5.6 | 6 | 12.8 | 2 | 5.4 |

| $30,000-$49,999 | 8 | 14.0 | 9 | 16.7 | 7 | 14.9 | 7 | 18.9 | |

| $50,000-$69,999 | 20 | 35.1 | 11 | 20.4 | 17 | 36.2 | 7 | 18.9 | |

| $70,000 or over * | 22 | 38.6 | 31 | 57.4 | 17 | 36.2 | 21 | 56.8 | |

In the pre-post sample, but not in the follow-up sample, the two groups were significantly different based on comparison of proportions in this demographic group with two-tailed tests and significance level .05. At follow-up only, the treatment group was significantly older.

Hypotheses

Based on the literature cited in the Blended Training section above, as well as our own previous study comparing online and in-person training (Delaney, Nelson, Pacifici, White, & Keefer Smalley, 2012), we hypothesized there would be significantly greater improvements for the Blended training than for the Foundations training on parenting knowledge and awareness, as well as higher satisfaction ratings. We also expected that improvements on parenting knowledge and awareness would be sustained at higher levels for the Blended training than for the Foundations training after 3 months.

Procedure

The study took place in Multnomah, Washington, and Clackamas Counties in Oregon, with the cooperation of the state's DHS and later with the Boys and Girls Aid of Oregon. Prospective resource parents in Oregon are required to take preservice training when a kinship, foster, or adopted child is placed or is about to be placed in their home. Oregon kinship families are required to attend the Foundations orientation meeting but have one year to complete the rest of the preservice training.

Prospective resource parents who had signed up for and attended one of 21 orientation sessions in Multnomah and Washington Counties during the study period heard a brief presentation about the study. Parents who felt qualified (had access to a computer and the internet), volunteered to participate, and provided informed consent were randomly assigned to one of two groups: a treatment group that received the Blended training or a comparison group that received the state's standard Foundations training. Couples were assigned to the same group. Each participant was emailed a unique link to the study site on FosterParentCollege.com to access and complete the online questionnaires (pre, post, and follow-up) and, for treatment group participants only, to view the online modules of the Blended training. Participants were linked directly to the study site, bypassing FosterParentCollege.com and blocking access to its other courses.

Following the orientation, parents assigned to the Blended training were instructed to view the first cluster of four online modules. When the Blended group met for the second scheduled in-person meeting, these modules were reviewed, classroom exercises were given, and the parents were assigned a second cluster of three online modules. The third in-person meeting followed the same format and was followed by the final cluster of three online modules. The fourth and final meeting included a review of the previous modules, a discussion, and interactive group activities. (In addition, as mentioned above, trainers also covered at the in-person meetings the topics that Lovejoy had identified as missing from the Blended curriculum.) Fifty-seven participants completed the Blended training in an average time of just under 9 weeks. (While the target number had been 60 per group, a decision was made not to conduct further Blended series and to be satisfied with the number that had been achieved.) Participants' progress was monitored and, when necessary, lagging participants were reminded by email to complete viewing the units. If a class meeting was missed, parents were given the opportunity to make it up. The in-person meetings for the Blended training were conducted by two very experienced and recently retired state trainers hired by Northwest Media.

Parents assigned to the comparison group completed the study's pretest assessment online and then took the standard classroom-only Foundations training. Unfortunately, reaching the target number for this group proved elusive and far more time consuming than anticipated, as the dropout rate was quite high. As noted previously, non-completion is a common problem for traditional in-person training such as Foundations (Groza et al., 2012). Reasons cited by study dropouts included difficulty finding time to attend the eight in-person training sessions and difficulty finding caregivers for their children so they could attend. When it became clear that there would likely be fewer than 25 comparison group completers in Multnomah and Washington Counties, a decision was made to seek help from Clackamas County DHS, which had a series of upcoming Foundations trainings scheduled. Random assignment was compromised when all participants recruited from these trainings were assigned to the comparison group, in an effort to balance the number of subjects in the two study groups. Between the three counties, participants who completed the Foundations training did so in an average time of about 11 weeks.

Still far short of the targeted number, when we learned that Boys and Girls Aid of Oregon would soon be offering a DHS-approved weekend Foundations training series, we secured their participation in the study and assigned all the parents to the comparison group. These departures from randomization, while not ideal, were necessitated by the time and money constraints of this grant-funded study. The fact that the two study groups were comparable on the measured demographic variables provided a greater sense of confidence about their equivalence. An additional 25 participants were recruited for the comparison group through Boys and Girls Aid, of whom 20 completed the Foundations curriculum during an intensive weekend training. Including these 20 parents gave us enough subjects in the comparison group to complete the study. The Foundations classroom training for the comparison group was conducted by four experienced state trainers and an experienced Boys and Girls Aid trainer.

Participants in both groups completed all assessment measures for the study online; parents in the comparison group had access only to the measures online, and not to the Blended curriculum. All participants had to complete the pre-intervention assessment before attending their second in-person class and the post-intervention assessment after attending the final in-person class. In the case of the Boys and Girls Aid group, the pretest measures were completed prior to attending the weekend training and the posttest measures at the end of the weekend training. Three months after completing the posttest assessment, participants in both study groups were contacted by email and invited to participate in an online follow-up assessment. Comparison group participants who completed the follow-up trial were given an opportunity to view the online portions of the Blended training free of charge.

The study participants had a wide range of technical skills, but as the lead trainer commented in her final report, “there were amazingly very few user issues and the ones that occurred were remedied almost immediately” (Lovejoy, 2014, p. 1). Throughout the study, we offered phone and email technical support to both groups. The website also has a technical self-help window, plus a comment button that allows users to directly comment to our software engineer on a one-on-one basis.

Measures

The pretest battery included questionnaires on background information, parent knowledge, and parent awareness. The posttest battery included the questionnaires on knowledge and awareness, as well as questionnaires on user satisfaction with the training approaches and, for the treatment group, usability of the online training. Assessment at the 3-month follow-up trial included the questionnaires on knowledge and awareness, as well as additional items about participants' placement experiences. All study measures were self-report measures presented online.

Background Information

An 8-item background information questionnaire was developed to obtain participants' basic demographics, including gender, age, and ethnic and racial background.

Knowledge Questionnaire

A 50-item scale was developed to assess subjects' overall knowledge of material covered in the training programs. Between 25 and 60 multiple-choice items were initially drafted for each of the 10 units of the Blended curriculum. As the production for each unit was completed, the pool of items for that unit was administered online to a group of 25 prospective resource parents, to determine acceptable levels of difficulty and clarity of wording. Items with correct response rates of 80% or higher were deemed too easy and dropped. Next, the content developers of the Blended training were asked to narrow the selection to the eight items that they judged were most important and representative for each unit. We then sent the 80 items to the study's head trainer of the Blended curriculum (who was also an experienced Foundations trainer) and asked her to identify items that were most relevant to the content in the Foundations program. A sufficient number of items overlapped so that we could further reduce the number to five items per unit, for a total of 50 items. Each subject's score on the 50-item scale was the percentage of correct responses; group means were used for analysis.

Awareness Questionnaire

A 20-item scale was developed to assess parents' self-perceptions of how well they recognize and understand parenting issues. While the items were drawn from the same content as the knowledge items, there was not a direct correspondence between items from the two measures. On a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), respondents were asked to rate how much they agreed with statements of parenting awareness, e.g., “I know how to recognize developmental difficulties in a child.” Similar to the procedure for developing the knowledge questionnaire, we first drafted a set of 8-10 items per unit in the Blended curriculum. We sent the pool of items to the developers of the training to narrow the selection to three items per unit. We then sent the 30 items to the study's head trainer of the Blended training and asked her to identify items that were also relevant to the Foundations approach. A sufficient number of items overlapped so that we could further reduce the number to two items per unit, for a total of 20 items. Each individual's score on the scale was the mean of ratings on the 20 items, with possible means ranging from 1 to 5 and higher scores indicating greater awareness; group means were used for analysis.

User Satisfaction with Overall Training

A core set of 12 items that were germane to both training programs was developed to assess participants' satisfaction with their training. Nine of the items asked respondents to rate statements about the program from 1 (not at all favorable) to 5 (very favorable). Scores used for analysis were the mean ratings for these nine items. In addition, there were three open-ended feedback questions about the training.

Usability Satisfaction with Online Training

Eight items were developed to assess satisfaction with features specific to the online training; five used rating scales similar to the other satisfaction items and another three were Yes/No questions about perceived advantages or disadvantages of online training.

Dropout Rate

The percent of participants who dropped out of the training before the posttest was tracked for each group. Dropouts consisted of subjects who took the pretest but did not complete the training or posttest.

Placement Experiences

Two items were developed for the follow-up trial to assess parents' perceptions of the helpfulness and effectiveness of their training for those parents who had had a child placed in their home. Parents rated each item on a scale of 1 (not helpful at all) to 10 (extremely helpful); they were then asked to provide explanatory comments about their responses.

Results

To assess the reliability/consistency of the scales used to measure knowledge, awareness, and satisfaction, we computed Cronbach's alpha for each. In general, values greater than .7 are considered “acceptable” and those greater than .9 are considered “excellent.” Reliability for the 20 items on the Awareness scale was excellent (α = .94 at pre and .93 at post). Out of the 50 original items on the Knowledge scale, 12 items that were least correlated with the overall mean knowledge score (r < .10) were dropped. The remaining 38 items had acceptable reliability (α = .71 at pre, .76 at post) and were used in further analysis. Reliability for the 9-item User Satisfaction with Overall Training scale was good (α = .83). It was lowest for the 5 items in the Usability Satisfaction with Online Training scale (α = .67); this measure is used only descriptively.

Repeated Measures Analyses of Knowledge and Awareness

To test for a difference in the effect of the training on the treatment and comparison groups' knowledge and awareness, we fit a repeated measures analysis of variance (RM ANOVA) for each variable. A significant interaction of group (treatment or comparison) and time (pre- and posttest assessment) indicates a difference in the effect of the training on the participants. After fitting each model, we used plots of residuals and fitted values to ensure there were no violations of the assumptions of the test. We then followed up each RM ANOVA with post hoc t tests to describe the pre-post differences for each group.

Knowledge

At baseline, there was no significant difference in knowledge between the treatment and comparison groups—t(109) = 1.48, p = .134—nor was there a significant difference between the groups at the posttest—t(109) = 0.35, p = .736. Both the treatment group and comparison group had significant increases in knowledge from pretest to posttest—t(109) = 7.26, p < .001 and t(109) = 4.2, p < .001, respectively. Knowledge increased from a mean of 54.8% correct to 65.7% in the treatment group and 58.5% to 64.8% in the comparison group. However, the significant interaction of group and time— F(1, 109) = 4.901, p = .029—indicated the mean increase in knowledge was significantly larger for the treatment group (10.9%) than for the comparison group (6.3%). (See Table 2 for mean pre- and posttest scores on Knowledge by group.)

Table 2. Mean Pre- and Posttest Scores on Knowledge and Awareness Scales by Group.

| Study Group | Pretest Score, Overall Knowledge Scale | Posttest Score, Overall Knowledge Scale | Pretest Score, Overall Awareness Scale | Posttest Score, Overall Awareness Scale | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Group-Blended Training | M | 54.8% | 65.7% | 3.80 | 4.42 |

| n | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | |

| SD | .13 | .14 | .57 | .36 | |

| Comparison Group - Foundations Training | M | 58.5% | 64.8% | 3.38 | 4.29 |

| n | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | |

| SD | .13 | .13 | .64 | .35 | |

| Total | M | 56.6% | 65.3% | 3.60 | 4.36 |

| n | 111 | 111 | 111 | 111 | |

| SD | .13 | .14 | .64 | .36 |

Note. Means on the Knowledge scale are the group mean percentages of correct responses to the 38 questions on the Knowledge questionnaire. Means on the Awareness scale are the group mean scores on the 20 Awareness questionnaire items, which were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate greater awareness of the parenting issues assessed.

Awareness

In the pretest, the treatment group had greater awareness than the comparison group (t(109) = 3.72, p < 0.001), but in the posttest there was no significant difference between the groups (t(109) = 1.91, p = .058). Both the treatment and comparison groups had significant increases in awareness in the posttest compared to the pretest (t(109) = 7.45, p < 0.001 and t(109) = 10.59, p < 0.001, respectively). The treatment group increased in Awareness from a mean of 3.80 to 4.42; the comparison group increased from a mean of 3.38 to 4.29. The data showed a significant interaction of group and time (F(1, 109) = 6.02, p = .016), indicating the mean increase in awareness was larger for the comparison group (.91) than for the treatment group (.62). (See Table 2 for mean pre- and posttest scores on Awareness by group.)

To further explore the change in Awareness over time, a secondary analysis was performed with RM ANOVA on change in Awareness based on Study Group as well as including a factor for Awareness level at baseline. Participants were split into two groups based on their Awareness score at pretest (baseline). Participants below the average at baseline (median = 3.65) were considered “low” Awareness, and those at or above the median were considered “high.” Results of this additional analysis showed that the interaction of Time (pre/post) by Baseline Awareness (high/low) was significant (F(1, 107) = 90.53, p < .001), whereas the interaction of Time by Study Group was not (F(1, 107) = .044, p = .834). This indicates that participants who started with lower Awareness showed more improvement than those who started with higher Awareness overall, whereas the study group (Blended training/treatment group versus Foundations training/comparison group) did not affect the results. After accounting for baseline Awareness levels, there is no evidence that the comparison group increased more than the treatment group. In addition, among participants who started with higher Baseline Awareness, those in the treatment group were observed to show slightly higher improvements in Awareness (M = 4.1 at pre to M = 4.5 at post) than those in the comparison group (M = 4.1 at pre to M = 4.3 at post). However, this difference in improvement was not significant (as indicated by 3-way interaction of Time, Baseline Awareness, and Study Group, F(1, 107) = 1.76, p = .187).

User Satisfaction with Overall Training

As measured on a scale from 1 to 5, where higher scores indicated greater satisfaction, user satisfaction was high in both the treatment and comparison group—M = 4.37, SD = .41 and M = 4.33, SD = .46, respectively—with no significant difference between them—t(109) = .501, p = .618. (See Table 3 for group means on the individual satisfaction questions and overall scale.)

Table 3. User Satisfaction with Overall Training, by Group.

| Study Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Treatment Group Blended Training (n = 57) | Comparison Group Foundations Training (n = 54) | |||

|

| ||||

| Question: On a scale of 1 (not at all favorable) to 5 (very favorable), how do you feel about: | M | SD | M | SD |

| The overall quality of the presentation of the training materials | 4.28 | .49 | 4.28 | .53 |

| The overall quality of the instructors | 4.49 | .71 | 4.74 | .44 |

| How convenient it was to take the training | 4.16 | .90 | 3.78 | 1.09 |

| How well prepared you are to have children placed in your home | 4.33 | .55 | 4.09 | .78 |

| How well the instruction was organized | 4.33 | .58 | 4.39 | .53 |

| Recommending this course to other prospective foster, adoptive, and relative caregivers | 4.51 | .54 | 4.39 | .76 |

| The handouts you received | 4.18 | .57 | 4.17 | .64 |

| The overall knowledge of the instructor | 4.63 | .59 | 4.78 | .42 |

| How well your questions about being a foster, adoptive, or relative caregiver were answered | 4.42 | .60 | 4.35 | .78 |

|

| ||||

| Overall User Satisfaction Scale (Mean of 9 items above) | 4.37 | .41 | 4.33 | .46 |

Usability Satisfaction with Online Training

On the individual usability items, as well as the overall usability scale, treatment group participants indicated high satisfaction with the online training (see Table 4).

Table 4. Usability Satisfaction with Online Training, Treatment Group Only.

| Treatment Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Question: On a scale of 1 (not at all favorable) to 5 (very favorable), how do you feel about: | M | SD | n |

| Receiving your preservice training on the web | 4.54 | .54 | 57 |

| How easy it was to use the website | 4.44 | .68 | 57 |

| How helpful the interactive exercises were | 4.04 | .71 | 57 |

| The length of the individual courses | 3.93 | .75 | 57 |

| How well the instruction covered the topics | 4.33 | .48 | 57 |

|

| |||

| Overall Usability Scale (Mean of 5 items above) | 4.26 | .42 | 57 |

In addition, treatment group participants responded affirmatively in the parenthetically noted percentages to the following three Yes/No questions at posttest: Did the in-person sessions satisfy your need for personal contact with the agency? (89.5%); Did the in-person sessions help you bond with other prospective foster, adoptive, and relative caregivers? (75.4%); and Was there a good balance between the in-person sessions and online courses? (94.7%).

Dropout Rate

Significantly more participants in the Foundations group dropped out, i.e., 56% compared to only 21% in the Blended group, Χ2 (1, N = 111) = 22.54, p < .001. The dropout rate was remarkably steeper for the Foundations participants in the normal 8-week training format (66%) compared to the weekend training format (17%). (See Table 5 for a breakdown of completion and dropout rates by study group, as well as by subgroups of the Foundations training group.)

Table 5. Completion and Dropout Rates, by Group.

| Blended In-Person and Online Training | Foundations In-person Training | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| DHS Blended Trainees in Three Portland Metro Area Counties | DHS Foundations Trainees in Three Portland Metro Area Counties | Boys and Girls Aid Foundations Trainees | DHS & Boys and Girls Aid Foundations Trainees Combined | |

| Number enrolled in the study | 72 | 99 | 24 | 123 |

| Number & percent who completed the study | 57 (79%) | 34 (34%) | 20 (83%) | 54 (44%) |

| Number & percent who dropped out | 15 (21%) | 65 (66%) | 4 (17%) | 69 (56%) |

Analyses for 3-month Follow-up Assessment

Knowledge

When follow-up data were added to the RM ANOVA for Knowledge, post hoc tests (with Bonferroni corrections) showed that neither group decreased significantly from posttest (treatment group/Blended M = .66, SD = .14; comparison group/Foundations M = .65, SD = .14) to follow-up (Blended M = .64, SD = .14, p = .648; Foundations M = .64, SD = .12, p > .999).

Awareness

When follow-up data were added to the RM ANOVA for Awareness, post hoc tests (with Bonferroni corrections) showed that neither group decreased significantly from posttest (Blended M = 4.41, SD = .36; Foundations M = 4.28, SD = .34) to follow-up (Blended M = 4.32, SD = .38, p = .315; Foundations M = 4.18, SD = .31, p = .299).

Placement Experiences

Parents who had had a child placed in their home were asked how helpful they found their preservice training to be. Parents in the Blended group gave an average rating of 7.71 (SD = 1.49) on a scale of 1 (not at all helpful) to 10 (extremely helpful). Those in the Foundations group gave an average rating of 7.00 (SD = 3.50), which was not significantly different from Blended, t(8.78) = .59, p = .569. When asked if they thought the way they were parenting the children placed with them was more effective than it would have been without the training, both groups were likely to say “yes,” with 88% in the Blended group doing so and 78% in the Foundations group; the difference was not significant, Χ2 (1, N = 42) = .65, p = .421.

Discussion

The current study compared a blended approach to preservice training for resource parents with a classroom-only program. The aim was to see whether the blended approach would produce superior outcomes to the classroom-only approach on parenting knowledge, awareness, and program satisfaction.

Regarding the outcome measures, our study found that the blended approach was more effective in imparting knowledge to prospective resource parents than the classroom-only approach, and that these differences were sustained at the 3-month follow-up assessment. Thus, our study provided critical support for the efficacy of online approaches to present informational components of parent training.

We also found that both interventions were effective in promoting awareness of parenting issues. Furthermore, parents who were least aware of parenting issues in both groups made the greatest gains. However, overall, parents in the classroom approach showed significantly greater gains than those in the blended approach. This unexpected finding prompted us to look further into our data. Our examination was informed by a well-documented understanding in the literature that prospective resource parents can be naïve about the hardships and realities of parenting. Myths such as “love is enough” and “the child's past is irrelevant” are testaments to a false sense of awareness (Smith & Howard, 1999). It seemed plausible, therefore, to expect that parents' perceptions of their own awareness would at first be inflated relative to what they actually knew about parenting a foster child; and that the disparity between awareness and knowledge would diminish as they became more informed. To explore this we looked at post hoc analyses of correlations between awareness and knowledge for each group at pre- and posttest. For both groups there was indeed a negative correlation between knowledge and awareness at pretest—i.e., there was a lack of correspondence between knowledge and awareness (r = -.164 for the treatment group and r = -.243 for the comparison group), while at posttest, the correlation became positive—i.e., there was more of a correspondence between awareness and knowledge (r = .074 for the treatment group and r = .065 for the comparison group). Thus, both parent training interventions seemed useful in moving parents' sense of awareness in greater concordance with their actual knowledge. It would be worth pursuing this connection in future studies to help interventionists understand how to deconstruct parenting myths.

The groups in our study showed a marked contrast in retention rates, with 79% of parents completing the Blended training and 44% completing the Foundations training. The retention rate for the Blended training was also much higher than retention rates previously reported for other programs (Groza et al., 2012). We should note that parents in the Blended program took substantially less time to complete the training than the 8-week Foundations program, which may help explain the group's dramatically higher retention rate. By contrast, we had to extend the length of the study in order for more parents in the Foundations group to complete the training.

On another note regarding retention, the study administrator/lead trainer reported that, when she was setting up the random assignment to experimental groups, a great deal of parent resistance to classroom training was exposed. Almost everyone pressed to be assigned to the Blended group, and some participants actually dropped out of the study because they were assigned to the Foundations group. People gave a variety of reasons for “needing” assignment to the Blended group, all of which stemmed from its reduced in-person training time and/or the increased flexibility of its online units.

Parents in both groups showed comparable satisfaction with their training. The anecdotal data we collected from the open-ended feedback questions on the user satisfaction questionnaire supported parents' comfort with the online approach, and when preferences did arise, they were consistently towards the online approach. There were no reported concerns about the reduced in-person meeting time of the Blended training. It was also encouraging that there were no notable issues with the technology or with parents using it. Since there are still lingering doubts about the user-friendliness of serious online training programs, this bolstered confidence that prospective caregivers were not alienated or distracted by the approach.

Several limitations of the study should be noted. Our sample of prospective resource parents turned out to be more homogeneous and less representative of the national population than we had hoped; in particular, it underrepresented African Americans and Hispanics. Also, in order to obtain adequate numbers for the comparison group within the time constraints of the study, we assigned all participants in the Clackamas County DHS Foundations and the Boys and Girls Aid weekend training to the comparison group, which was not randomized. Finally, we utilized measures developed specifically for this study rather than standardized measures, so information regarding their psychometric properties is limited. Ideally, future studies of a blended approach to preservice training would recruit samples more diverse in terms of ethnicity, race, and perhaps also geography. As statistics become available on the ethnic and racial breakdown of foster, adoptive, and kinship parents, samples in future studies should attempt to be representative of that population.

In conclusion, the results of this study provide promising evidence that a blended approach, which combines the autonomy and convenience of web-based instruction with face-to-face training time, is materially comparable to, if not an improvement upon, standard in-person training. A blended approach, as demonstrated here, can be well-received by prospective resource parents, shorten the lengthy preservice training phase, and ultimately increase the numbers of prospective resource parents who complete training. From an agency perspective, a blended approach can guarantee that the core topics common to the major preservice curriculums are delivered uniformly and efficiently via the web. This effectively frees up valuable in-person training time for trainers to address parent questions, to aid prospective resource parents in the self-selection process, and to present agency-specific or state-mandated information.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this article was supported by Awards R43 HD054032 and R44 HD054032 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

We appreciate the cooperation and support we received for the study described from Sarah Walker and staff of the Oregon Department of Human Services (DHS) Central Office, including foster care program managers Kevin George and A. J. Goins; DHS training staff in the three participating Oregon counties (Multnomah, Washington, and Clackamas); participating training staff at Boys and Girls Aid; and former DHS trainer Helena Abrams, who shared the curriculum development and training responsibilities with the study's lead trainer and article co-author, Maureen Lovejoy. We could not have accomplished the study without them.

Contributor Information

Lee White, Northwest Media, Inc., Eugene, Oregon.

Richard Delaney, Northwest Media, Inc., Eugene, Oregon.

Caesar Pacifici, Northwest Media, Inc., Eugene, Oregon.

Carol Nelson, Northwest Media, Inc., Eugene, Oregon.

Josh Whitkin, Northwest Media, Inc., Eugene, Oregon.

Maureen Lovejoy, Maureen Lovejoy Training LLC, Lake Oswego, Oregon.

Betsy Keefer Smalley, Institute for Human Services, Columbus, Ohio.

References

- Annie E. Casey Foundation. Building successful resource families practice guide: A guide for public agencies. Baltimore, MD: Author; 2012. Retrieved from http://www.aecf.org/resources/building-successful-resource-families/ [Google Scholar]

- Bonk CJ, Graham CR, editors. The handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs. San Francisco: Pfeiffer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. Placement of children with relatives. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children's Bureau; 2013. Retrieved from https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/systemwide/laws-policies/statutes/placement/ [Google Scholar]

- Clark RC, Mayer RE. E-learning and the science of instruction: Proven guidelines for consumers and designers of multimedia learning. 3rd. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney R, Nelson C, Pacifici C, White L, Keefer Smalley B. Web-enhanced preservice training for prospective resource parents: A randomized trial of effectiveness and user satisfaction. Journal of Social Service Research. 2012;38:503–514. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2012.696416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008, Pub. L. No. 110-351, 122 Stat. 3949 (2008).

- FosterParentCollege.com. Annual estimate of the number of prospective foster parents receiving preservice training nationally. Unpublished estimate; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm B. Foster parent training: What the CFS Reviews do and don't tell us (Child & Family Services Reviews: Part II in a Series) Youth Law News: Journal of the National Center for Youth Law. 2003;24:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Groza V, Riley-Behringer M, Cage J, Lodge K. Partners for forever families: A public-private-university initiative and neighborhood-based approach (Year 4 evaluation report) 2012 Retrieved from http://msass.case.edu/downloads/vgroza/Year_4_Evaluation_Report.pdf.

- Güzer B, Caner H. The past, present and future of blended learning: An in depth analysis of literature. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2014;116:4596–4603. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.992. Retrieved from http://ac.els-cdn.com/S187704281401009X/1-s2.0-S187704281401009X-main.pdf?_tid=e523150e-2841-11e6-a202-00000aab0f26&acdnat=1464817596_4c71d89028b0130f90ab26c87191d48f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes G. Using blended learning to increase learner support and improve retention. Teaching in Higher Education. 2007;12(3):349–363. [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy M. Summary of Northwest Media's project, web-enhanced pre-service training for foster, adoptive, and kinship parents. Unpublished report submitted to Northwest Media, Inc; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Means B, Toyama Y, Murphy R, Baki M. The effectiveness of online and blended learning: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Teachers College Record. 2013 Retrieved from https://www.sri.com/sites/default/files/publications/effectiveness_of_online_and_blended_learning.pdf.

- Melton BF, Bland HW, Chopak-Foss J. Achievement and satisfaction in blended learning versus traditional general health course designs. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. 2009 Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/ij-sotl/vol3/iss1/26.

- National Resource Center for Family-Centered Practice and Permanency Planning, Hunter College School of Social Work. Foster parent pre-service training. 2008 Jan; Retrieved from http://www.hunter.cuny.edu/socwork/nrcfcpp/downloads/policy-issues/Foster_Parent_Preservice_Training.pdf.

- Petras DD, Pasztor EM. PRIDE book: New Generation Foster PRIDE/Adopt PRIDE. Washington, D.C.: Child Welfare League of America; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Howard J. Promoting successful adoptions: Practice with troubled families. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children's Bureau. The AFCARS report: Preliminary FY 2014 estimates as of July 2015 (22) 2015 Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport22.pdf.

- Wilson JB, Katz J, Geen R. Listening to parents: Overcoming barriers to the adoption of children from foster care. 2005 Retrieved from http://www.hks.harvard.edu/ocpa/pdf/Listening%20to%20Parents.pdf.