Abstract

Objective

Liver dysfunction due to heart failure (HF) is known as congestive hepatopathy. It has recently been reported that liver stiffness assessed by transient elastography reflects increased central venous pressure. The Fibrosis-4 (FIB4) index (age (years) × aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L)/platelet count (109/L) × square root of alanine aminotransferase (IU/L)) is expected to be useful for evaluating liver stiffness in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. We aimed to investigate the impact of the FIB4 index on HF prognosis, with consideration for liver fibrosis markers and underlying cardiac function.

Methods

Consecutive 1058 patients with HF who were admitted to our hospital were divided into three groups based on their FIB4 index: first (FIB4 index <1.72, n=353), second (1.72≤FIB4 index <3.01, n=353) and third tertiles (3.01≤FIB4 index, n=352). We prospectively followed for all-cause mortality.

Results

During the follow-up period (mean 1047 days), 246 deaths occurred. In the Kaplan-Meier analysis, all-cause mortality progressively increased from the first to third groups (12.2%, 21.0% and 36.6%, p<0.01). In the Cox proportional hazard analysis, FIB4 index was an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with HF (p<0.05). In comparisons of laboratory and echocardiographic findings, the third tertile had higher levels of type IV collagen 7S, procollagen type III peptide, hyaluronic acid, left atrial volume, mitral valve E/e’, inferior vena cava diameter and right atrial end systolic area (p<0.01, respectively).

Conclusion

The FIB4 index, a marker of liver stiffness, is associated with higher all-cause mortality in patients with HF.

Keywords: heart failure

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

It has been recently reported that the liver stiffness, which reflects increased central venous pressure, measured by transient elastography increases along with decompensated heart failure (HF) developing and decreases with clinical improvement. A simple index for the assessment of liver stiffness and/or impairment of liver reserve may be useful in patients with HF

What does this study add?

In this present study, we first presented that the Fibrosis-4 (FIB4) index, a simple marker of liver stiffness, is associated with markers of liver fibrosis, larger right and left heart volume overload and higher all-cause mortality in patients with HF.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

The FIB4 index can be an alternative marker to measurement of liver stiffness. Each parameters of the FIB4 index can be measured quickly even in clinics, emergent medical service and so on with point-of-care testing.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a widespread and serious problem that has been reported in many countries.1 Associated with worsening multiple organ failure including kidney and liver,1 HF also causes liver dysfunction with a combination of reduced arterial perfusion and passive congestion.2–4 Liver congestion might be mutually associated with liver stiffness, resulting in fibrosis (eg, nutmeg liver) and adverse prognosis.2–5 It has recently been reported that the liver stiffness measured by transient elastography increases along with the development of decompensated HF and decreases with clinical improvement.5–7 A simple index for the assessment of liver stiffness and/or impairment of liver reserve may be useful in patients with HF. The Fibrosis-4 (FIB4) index (age (years) × aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L)/platelet count (109/L) × square root of alanine aminotransferase (IU/L)) has been reported to be useful for evaluating liver fibrosis or stiffness in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).8 FIB4 index, which can be calculated simply and repeatedly, indicates liver stiffness and impairment of liver reserve. Thus, we aimed to verify the value of FIB4 index as a risk assessment tool for mortality in patients with HF and its underlying cardiac function and liver fibrosis confirmed by established biochemical markers such as type IV collagen 7S, procollagen type III peptide (PIIIP) and hyaluronic acid.9 10

Methods

Subjects and study protocol

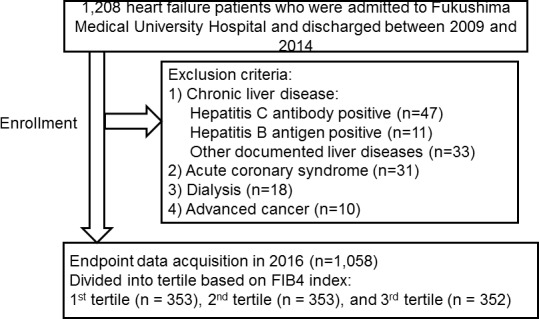

This was a prospective observational study of patients with decompensated HF who were discharged from Fukushima Medical University Hospital between 2010 and 2014. The diagnosis of decompensated HF was defined based on the Framingham criteria.11 Blood samples were obtained at discharge. All patients underwent testing for hepatitis B antigen and hepatitis C antibody, and their medical history was checked for chronic liver disease (cirrhosis, hepatic tumours, bile duct disease, etc). Patients with liver disease, acute coronary syndrome, dialysis and advanced cancer were excluded. The flow chart of patients is shown in figure 1. We calculated each patient’s FIB4 index using the following formula: (age (years) × aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L)/platelet count (109/L) × square root of alanine aminotransferase (IU/L)).8 Consecutive 1058 patients were divided into three groups based on their FIB4 index8 at discharge: first tertile (FIB4 index <1.72, n=353), second tertile (1.72≤ FIB4 index <3.01, n=353) and third tertile (3.01≤ FIB4 index, n=352).

Figure 1.

Patient flow chart.

Hypertension was defined as the recent use of antihypertensive drugs, systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg. Dyslipidaemia was defined as the recent use of cholesterol-lowering drugs, a triglyceride value of ≥150 mg/dL, a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol value of ≥140 mg/dL and/or a high-density lipoprotein cholesterol value of <40 mg/dL. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of <60 mL/min/1.73 cm2,12 and anaemia was defined as haemoglobin levels of <12.0 g/dL in females and <13.0 g/dL in males.1 Atrial fibrillation was identified by an ECG performed during hospitalisation and/or from medical records including history.

We compared the clinical features and the results of several examinations, performed at hospital discharge. The patients were followed up until 2016 for all-cause mortality, and the causes of cardiac death were classified by independent experienced cardiologists as worsened HF in accordance with the Framingham criteria,11 ventricular fibrillation documented by ECG or implantable devices or acute coronary syndrome. Status and dates of death were obtained from the patients’ medical records. If these data were unavailable, status was ascertained by a telephone call to the patients’ referring hospital physician. Those administering the survey were blind to the analyses, and written informed consent was obtained from all study subjects. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of Fukushima Medical University, and the investigation conforms with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Reporting of the study conforms to STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) along with references to STROBE and the broader EQUATOR guidelines.13

Measurement of type IV collagen 7S, PIIIP and hyaluronic acid

The levels of serum type IV collagen 7S was measured by radioimmunoassay (Type IV collagen 7S kit, SCETI MEDICAL LABO KK, Tokyo, Japan). Serum PIIIP was measured by immunoradiometric assay (RIA-gnost PIIIP ct, CISbioBioassays, Codolet, France). Serum hyaluronic acid was measured by latex agglutination-turbidimetric immunoassay (LPIA Ace HA, LSI Medience, Tokyo, Japan). These assays were blindly performed by a laboratory company (LSI Medience, Tokyo, Japan).

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed blindly by experienced cardiologists and medical technologists with standard techniques.14 The echocardiographic parameters investigated included left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left atrial volume, the ratio of early transmitral flow velocity to mitral annular velocity (mitral valve E/e’), inferior vena cava diameter, systolic pulmonary arterial pressure (SPAP), right atrial end-systolic area and right ventricular fractional area change (RV-FAC). Mitral valve E/e’ was calculated by transmitral Doppler flow and tissue Doppler imaging. SPAP was calculated by adding the right atrial pressure (estimated by the diameter and collapsibility of the inferior vena cava) to the systolic transtricuspid pressure gradient.14 The RV-FAC, defined as (end-diastolic area–end-systolic area)/end-diastolic area × 100, is a measure of right ventricular systolic function. All measurements were performed using ultrasound systems (ACUSON Sequoia, Siemens Medical Solutions, Mountain View, California, USA).

Statistical analysis

Parametric variables are presented as mean±SD, non-parametric variables were log transformed (eg, B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), hyaluronic acid), and categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages. The characteristics of the three groups were compared using analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, and the χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Multivariable regression analysis was used to determine which element of FIB4 index related to the index. Correlations between FIB4 index and markers which is related with liver fibrosis and congestion (eg, type IV collagen 7S, PIIIP, hyaluronic acid, BNP and estimated GFR) were assessed using Spearman’s correlation analysis. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for presenting the event-free rate, and the log-rank test was used for initial comparisons. To prepare for potential confounding factors in the Cox regression analyses, we considered the following clinical factors, which are not included in the FIB4 index and possibly affect the risk of mortality in patients with HF: sex, body mass index, New York Heart Association class, ischaemic aetiology, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, atrial fibrillation, haemoglobin, estimated GFR, sodium, BNP, LVEF and use of several medicines such as renin–angiotensin–system (RAS) inhibitors, β-blockers, diuretics and inotropic agents. Baseline variables with p<0.05 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. We constructed two models: in the first, we analysed the FIB4 index as a categorical variable (Third, second vs first tertile), and in the second we analysed the FIB4 index as a continuous variable. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all comparisons. These analyses were performed using a statistical software package SPSS V.24.0.

Results

In the multiple regression analysis to determine FIB4 index, the elements of the index were as follows: aspartate aminotransferase, ß=0.473, p<0.001; platelet count, ß=−0.293, p<0.001; age, ß=0.122, p<0.001; alanine aminotransferase, ß=−0.116, p=0.015. In addition, there were significant positive correlations between FIB4 index and other markers of liver fibrosis, congestion and renal function (type IV collagen 7S, R=0.313, p<0.001; PIIIP, R=0.233, p=0.009; hyaluronic acid, R=0.303, p<0.001; BNP, R=0.285, p<0.001; and estimated glomerular filtration rate, R=−0.143, p<0.001).

The comparisons of clinical features in the present study are shown in table 1. The third tertile had higher age, lower levels of body mass index, higher prevalence of New York Heart Association class III or IV, atrial fibrillation, CKD and anaemia, lower prevalence of dyslipidaemia and higher usage of diuretics and inotropic agents. In the laboratory data (table 2), the third tertile had higher levels of BNP, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transaminase, type IV collagen 7S, PIIIP, hyaluronic acid and lower levels of total protein, albumin, cholinesterase and estimated GFR. In the echocardiographic data (table 2), the third tertile had higher levels of left atrial volume, mitral valve E/e’, inferior vena cava diameter and right atrial end-systolic area. In contrast, LVEF, SPAP and RV-FAC change did not significantly differ among the three groups.

Table 1.

Comparisons of clinical features of patients by tertiles of FIB4 index (n=1058)

| First tertile FIB4 <1.72 (n=353) |

Second tertile 1.72< FIB4<3.01 (n=353) |

Third tertile 3.01< FIB4 (n=352) |

p Value | |

| Age (years) | 56.1±15.0 | 70.6±10.6** | 75.4±9.4**†† | <0.001 |

| Male gender (n, %) | 230 (65.2) | 213 (60.3) | 200 (56.8) | 0.075 |

| Body mass index (kg/cm2) | 24.4±4.4 | 23.0±4.3** | 22.7±3.8**†† | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 125.8±29.5 | 129.2±33.4 | 129.6±33.0 | 0.222 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 73.0±20.6 | 72.9±20.0 | 72.1±20.5 | 0.820 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 82.0±23.5 | 79.8±25.0 | 80.7±24.7 | 0.490 |

| NYHA class III or IV | 4 (1.1) | 9 (2.5) | 18 (5.1) | 0.006 |

| Ischaemic aetiology (n, %) | 79 (22.4) | 94 (26.6) | 104 (29.5) | 0.094 |

| Reduced LVEF (n, %) | 197 (55.8) | 179 (50.7) | 192 (54.5) | 0.367 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Hypertension (n, %) | 256 (72.5) | 295 (83.6) | 280 (79.5) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes (n, %) | 134 (38.0) | 151 (42.8) | 147 (41.8) | 0.390 |

| Dyslipidaemia (n, %) | 290 (82.2) | 280 (79.3) | 258 (73.3) | 0.014 |

| Atrial fibrillation (n, %) | 98 (27.8) | 137 (38.8) | 175 (49.7) | <0.001 |

| CKD (n, %) | 149 (42.2) | 207 (58.6) | 258 (73.3) | <0.001 |

| Anaemia (n, %) | 155 (43.9) | 196 (55.5) | 238 (67.6) | <0.001 |

| Medications | ||||

| RAS inhibitors (n, %) | 262 (74.2) | 274 (77.6) | 267 (75.9) | 0.572 |

| β-blockers (n, %) | 278 (78.8) | 288 (81.6) | 271 (77.0) | 0.317 |

| Diuretics (n, %) | 217 (61.5) | 249 (70.5) | 263 (74.7) | 0.001 |

| Inotropic agents (n, %) | 25 (7.1) | 34 (9.6) | 57 (16.2) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as median (IQR).

**p<0.01 versus 1 tertile.

††p<0.01 versus second tertile.

BP, blood pressure; NYHA, New York Heart Association; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; CKD, chronic kidney disease; RAS, rennin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

Table 2.

Laboratory and echocardiographic data

| First tertile (n=353) |

Second tertile (n=353) |

Third tertile (n=352) |

p Value | |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| Log BNP | 2.2±0.6 | 2.5±0.5 | 2.6±0.5**†† | <0.001 |

| Total protein (g/L) | 7.1±0.8 | 7.0±0.7 | 6.8±0.8**†† | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 3.8±0.6 | 3.7±0.6 | 3.5±0.6**†† | <0.001 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.9±0.5 | 0.9±0.5 | 1.1±0.7 | 0.146 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.1±0.1 | 0.1±0.1 | 0.2±0.2 | 0.086 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 246.4±114.3 | 257.9±134.2 | 280.8±114.4** | 0.008 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase (U/L) | 55.9±64.1 | 60.0±96.3 | 76.6±95.5** | 0.009 |

| Cholinesterase (U/L) | 294.1±88.2 | 266.2±77.1 | 215.0±70.0**†† | <0.001 |

| Estimated GFR (mL/min/1.73 cm2) | 62.6±25.2 | 56.4±22.3** | 48.1±21.8**†† | <0.001 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 138.9±3.3 | 139.2±3.6 | 138.4±4.4† | 0.018 |

| Type IV collagen 7S (ng/mL) | 4.5±1.7 | 4.8±1.7* | 5.9±2.5**†† | <0.001 |

| PIIIP (U/mL) | 0.6±0.3 | 0.7±0.4* | 0.8±0.3**† | <0.001 |

| Log hyaluronic acid | 1.6±0.3 | 1.9±0.4** | 2.1±0.4**†† | <0.001 |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| LVEF (%) | 49.0±17.0 | 50.0±15.9 | 50.2±14.9 | 0.640 |

| Left atrial volume (mL) | 74.9±47.9 | 82.8±56.6 | 92.5±72.0** | 0.004 |

| Mitral valve E/e’ | 13.8±7.0 | 15.3±9.8 | 16.6±9.1** | 0.004 |

| Inferior vena cava diameter (mm) | 14.4±4.6 | 14.5±4.4 | 16.2±5.4**†† | <0.001 |

| SPAP (mm Hg) | 30.3±18.5 | 30.2±15.2 | 31.0±14.9 | 0.854 |

| Right atrial end-systolic area (cm2) | 17.6±10.4 | 17.4±8.5 | 20.9±11.1**†† | 0.003 |

| RV-FAC (%) | 42.1±15.8 | 41.6±13.3 | 41.7±14.3 | 0.941 |

Data are presented as median (IQR).

*p<0.05 and **p<0.01 versus

*p<0.05 and **p<0.01 versus first tertile. †p<0.05 and ††p<0.01 versus second tertile.

BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; Mitral valve E/e’, ratio of the peak transmitral velocity during early diastole to the peak mitral valve annular velocity during early diastole; PIIIP, procollagen type III peptide; RV-FAC, right ventricular fractional area change; SPAP, systolic pulmonary artery pressure.

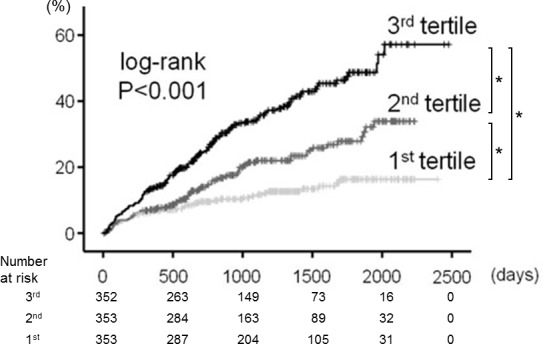

In the follow-up period (mean 1047 days), 246 deaths (122 cardiac deaths and 124 non-cardiac deaths) occurred. In the Kaplan-Meier analysis (figure 2), all-cause mortality increased progressively from the first group to the third group (p<0.001). In the Cox proportional hazard analysis (table 3), a high FIB4 index was an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with HF.##

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis for all-cause mortality among the three groups (first, second and third tertiles of the FIB4 index). *p<0.05.

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazard model of all-cause mortality in heart failure

| All-cause mortality (n=246/1058) | HR | 95% CI | p Value |

| FIB4 index as categorical variable | |||

| Third versus first tertile unadjusted | 3.547 | 2.511 to 5.012 | <0.001 |

| Third versus first tertile adjusted* | 1.943 | 1.071 to 3.526 | 0.020 |

| Second versus first tertile unadjusted | 1.855 | 1.274 to 2.702 | 0.001 |

| Second versus first tertile adjusted* | 1.488 | 1.028 to 2.127 | 0.039 |

| FIB4 index as continuous variable | |||

| Unadjusted model | 1.194 | 1.120 to 1.275 | <0.001 |

| Adjusted model* | 1.127 | 1.018 to 1.253 | 0.042 |

*Adjusted for sex, body mass index, New York Heart Association class, ischaemic aetiology, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, atrial fibrillation, haemoglobin, estimated glomerular filtration rate, sodium, B-type natriuretic peptide, left ventricular ejection fraction, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors, β-blockers, diuretics, inotropic agents.

Discussion

The present study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to report that the FIB4 index, a marker of liver stiffness, is associated with type IV collagen 7S, PIIIP, hyaluronic acid, BNP, larger right and left heart volume overload, as well as higher all-cause mortality in patients with HF.

Systemic venous congestion rise to neurohormonal activation (eg, RAS), decreases plasma natriuretic peptide,15 leads to HF progression, may contribute to worsening multiple organ failure5 16 17 and result in adverse prognosis.18 Increased central venous pressure causes liver stiffness.5 19 20 The liver transient elastography shows increased liver stiffness at admission due to HF and an improvement at discharge.7 The FIB4 index8 can be used as an alternative marker for the measurement of liver stiffness and/or reserve. It can be calculated with only four parameters that are measured in daily medical care. These parameters, such as aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase and platelet count, can be measured quickly even in clinics by emergency medical services and more with point-of-care testing.

HF, especially decompensated HF, sometimes consists of not only congestion, but also reduced arterial flow called hypoxic hepatopathy. Hypoxia causes centrilobular necrosis in the liver and leads to the elevation of transaminase.21 In addition, increased central venous pressure causes hepatocyte atrophy and perisinusoidal oedema in the liver.2 4 Sinusoidal damage leads to impaired clearance of aspartate aminotransaminase.22 Portal hypertension and liver fibrosis cause a reduced platelet count. Increased pressure within the hepatic sinusoid favours bile duct damage by disrupting endothelial cells and the inter hepatocyctic tight junctions that separate the extravascular space from the bile canaliculus. Further, stagnant flow favours thrombosis within sinusoids, hepatic venules and portal tracts, thereby contributing to liver fibrosis.3 23 Centrilobular liver cell necrosis can extend to peripheral areas if HF persists and worsens, and is followed by the deposition and spread of connective tissue bridging one central vein to another, ultimately leading to liver cirrhosis.3 Concordant with these findings, in the present study, there were significant associations between type IV collagen 7S, PIIIP, hyaluronic acid, BNP and the FIB4 index. Moreover, right and left volume overload was assumed in high FIB4 index groups in the present study. Therefore, an elevated FIB4 index might indicate liver fibrosis, underlying increased venous pressure and congestion.

In addition, HF and NAFLD has some common pathophysiology and comorbidities. Elevated RAS, oxidative stress, insulin resistance and inflammation cause atherosclerosis and increase organ fibrosis in patients both with HF1 and NAFLD.24 25 NAFLD is associated with atherosclerosis,26 27 reduced coronary flow reserve,28 impaired myocardial metabolism, left ventricular dysfunction and higher cardiovascular mortality.3 25 29 30 These may explain the association between the severities of NAFLD (FIB4 index) and HF.

Study limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, as a prospective cohort study of a single centre with a relatively small number of patients, the study may be somewhat underpowered. Second, it remains unclear whether the FIB4 index reflects only liver fibrosis and/or congestion resulting in liver stiffness. Although patients with HF with documented liver disease were excluded, we cannot completely deny the presence of liver disease. The relationships between the FIB4 index and other fibrosis evaluations, such as liver biopsy, which is not generally applied in patients with HF, or imaging (eg, CT, elastography) should be assessed in further studies. Third, we have conducted the present study using only variables on hospitalisation, without taking into consideration changes in medical parameters and postdischarge treatment. Therefore, the present results should be viewed as preliminary, and further studies with a larger population are needed.

Conclusion

The FIB4 index, a marker of liver stiffness, is associated with type IV collagen 7S, PIIIP, hyaluronic acid, BNP, larger right and left heart volume overload and higher mortality in patients with HF.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the efforts of Ms Kumiko Watanabe and Hitomi Kobayashi for their outstanding technical assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: AY and YT: drafted thearticle and conceptualised the study; YS and YK: performed the statisticalanalysis; SW, TY, SA, TM, TS, SS, MO, AK, TY, HK and KN: obtained general data;SS and YT: revised the article critically for important intellectual content.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained

Ethics approval: Ethical Committee of Fukushima Medical University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;2016:891–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Samsky MD, Patel CB, DeWald TA, et al. Cardiohepatic interactions in heart failure: an overview and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:2397–405. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Møller S, Bernardi M. Interactions of the heart and the liver. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2804–11. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nikolaou M, Parissis J, Yilmaz MB, et al. Liver function abnormalities, clinical profile, and outcome in acute decompensated heart failure. Eur Heart J 2013;34:742–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jalal Z, Iriart X, De Lédinghen V, et al. Liver stiffness measurements for evaluation of central venous pressure in congenital heart diseases. Heart 2015;101:1499–504. 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-307385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taniguchi T, Sakata Y, Ohtani T, et al. Usefulness of transient elastography for noninvasive and reliable estimation of right-sided filling pressure in heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2014;113:552–8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Colli A, Pozzoni P, Berzuini A, et al. Decompensated chronic heart failure: increased liver stiffness measured by means of transient elastography. Radiology 2010;257:872–8. 10.1148/radiol.10100013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shah AG, Lydecker A, Murray K, et al. ; Nash Clinical Research Network. Comparison of noninvasive markers of fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:1104–12. 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.05.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sanyal AJ. American Gastroenterological A. AGA technical review on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2002;123:1705–25. 10.1053/gast.2002.36572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grigorescu M. Noninvasive biochemical markers of liver fibrosis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2006;15:149–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McKee PA, Castelli WP, McNamara PM, et al. The natural history of congestive heart failure: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med 1971;285:1441–6. 10.1056/NEJM197112232852601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:247–54. 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007;335:806–8. 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification. Eur J Echocardiogr 2006;7:79–108. 10.1016/j.euje.2005.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kalra PR, Anagnostopoulos C, Bolger AP, et al. The regulation and measurement of plasma volume in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:1901–8. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01903-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mohamed BA, Schnelle M, Khadjeh S, et al. Molecular and structural transition mechanisms in long-term volume overload. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:362–71. 10.1002/ejhf.465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Francis GS, et al. Importance of venous congestion for worsening of renal function in advanced decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:589–96. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Testani JM, Chen J, McCauley BD, et al. Potential effects of aggressive decongestion during the treatment of decompensated heart failure on renal function and survival. Circulation 2010;122:265–72. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.933275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Millonig G, Friedrich S, Adolf S, et al. Liver stiffness is directly influenced by central venous pressure. J Hepatol 2010;52:206–10. 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yoshitani T, Asakawa N, Sakakibara M, et al. Value of virtual touch quantification elastography for assessing liver congestion in patients with heart failure. Circ J 2016;80:1187–95. 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Birrer R, Takuda Y, Takara T. Hypoxic hepatopathy: pathophysiology and prognosis. Intern Med 2007;46:1063–70. 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.0059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kamimoto Y, Horiuchi S, Tanase S, et al. Plasma clearance of intravenously injected aspartate aminotransferase isozymes: evidence for preferential uptake by sinusoidal liver cells. Hepatology 1985;5:367–75. 10.1002/hep.1840050305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cogger VC, Fraser R, Le Couteur DG. Liver dysfunction and heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2003;91:1399. 10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00370-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fotbolcu H, Zorlu E. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease as a multi-systemic disease. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:4079–90. 10.3748/wjg.v22.i16.4079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brea A, Puzo J. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular risk. Int J Cardiol 2013;167:1109–17. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.09.085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Targher G, Bertolini L, Padovani R, et al. Relations between carotid artery wall thickness and liver histology in subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetes Care 2006;29:1325–30. 10.2337/dc06-0135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brea A, Mosquera D, Martín E, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with carotid atherosclerosis: a case-control study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:1045–50. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000160613.57985.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yilmaz Y, Kurt R, Yonal O, et al. Coronary flow reserve is impaired in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: association with liver fibrosis. Atherosclerosis 2010;211:182–6. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.01.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bhatia LS, Curzen NP, Calder PC, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a new and important cardiovascular risk factor? Eur Heart J 2012;33:1190–200. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Targher G, Day CP, Bonora E. Risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1341–50. 10.1056/NEJMra0912063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]