Abstract

Objective

In patients with mild to moderate operative risk, surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) is still the preferred treatment for patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis (AS). Aiming to broaden the knowledge of postsurgical outcomes, this study reports a broad set of morbidity outcomes following surgical intervention.

Methods

Our cohort comprised 442 patients referred for severe AS; 351 had undergone SAVR, with the remainder (91) not operated on. All patients were evaluated using the 6-minute walk test (6MWT), were assigned a New York Heart Association class (NYHA) and Canadian Cardiovascular Society class (CCS), with additional scores for health-related quality of life (HRQoL), cognitive function (Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)) and myocardial remodelling (at inclusion and at 1-year follow-up). Adverse events and mortality were recorded.

Results

Three-year survival after SAVR was 90.0%. SAVR was associated with an improved NYHA class, CCS score and HRQoL, and provoked reverse ventricular remodelling. The 6MWT decreased, while the risks of major adverse cardiovascular events (death, non-fatal stroke/transient ischaemic attack or myocardial infarction) and all-cause hospitalisation (incidence rate per 100 patient-years) were 13.5 and 62.4, respectively. The proportion of cognitive disability measured by MMSE increased after SAVR from 3.2% to 8.8% (p=0.005). Proportion of patients living independently at home, having attained NYHA class I, was met by 49.1% at 1 year. Unoperated individuals had a poor prognosis in terms of any outcome.

Conclusion

This study provides knowledge of outcomes beyond what is known about the mortality benefit after SAVR to provide insight into the morbidity burden of modern-day SAVR.

Keywords: Aortic valvne disease, Surgery -valve, Quality of care and outcomes

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

In patients with severe symptomatic aortic valve stenosis (aortic stenosis), surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) has been shown to improve survival, relieve symptoms and increase quality of life.

What does this study add?

This study provides a broader-based insight into what to expect after SAVR through a variety of morbidity outcomes. This study describes current standard care for patients with severe AS in low to intermediate surgical risk who are referred to a tertiary centre for evaluation of aortic valve replacement.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

The variety of treatment outcomes presented in this study might prove valuable in the process of shared decision-making between members of the heart team and patients seeking advice based on their preferences. A careful look at postsurgical morbidity outcomes following SAVR in an era where transcatheter aortic valve replacement is proposed by some as the new standard of care, is much needed. Knowledge of multiple patient-relevant outcomes following SAVR is valuable for clinicians seeking to engage in the ongoing adaptation towards individualised patient care, and such data should be taken into consideration when designing new randomised trials.

Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common type of valvular heart disease and its prevalence is expected to double in the next two decades.1 There is no medical therapy to prevent the natural progression of the disease, but aortic valve replacement (AVR) improves survival and relieves symptoms. Left unoperated, patients who eventually become symptomatic face a dismal prognosis of up to 50% mortality over 2 years.2 American and European guidelines3 4 recommend AVR in case of severe, symptomatic AS, with surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) being the standard approach for patients with a low to intermediate surgical risk.5 Multiple studies have confirmed the beneficial effects of SAVR on mortality, symptom relief and increased quality of life at subsequent follow-up.6 7 However, morbidity outcomes are less often reported. In modern medicine, individualised patient care calls for increased knowledge of outcomes so that patients can have realistic expectations following SAVR. The requirement for knowledge of morbidity outcomes and future physical performance in the process of shared decision-making is imminent. With this study, we aim to provide data on patient-relevant outcomes beyond what is known, in an effort to improve decision-making as a result. We report a broad set of morbidity outcomes and measures of physical performance in patients with severe AS referred for evaluation of AVR, reflecting modern-day clinical practice at a single tertiary centre.

Methods

Study design and patient population

Between May 2010 and March 2013, patients with severe AS referred for evaluation for AVR were prospectively included in an observational cohort in our tertiary centre (Oslo University Hospital Rikshospitalet, Norway). Inclusion criteria included age (>18 years), and the ability to read and write Norwegian. Patients without severe AS, unwilling participants, or patients with previous AVR or percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty were excluded. Thirty-eight subjects scheduled for transcatheter aortic valve implantation were excluded due to the limited number of transcatheter interventions performed during this period. Severe AS was defined in accordance with current guidelines.4 In cases of a low-flow, low-gradient state, with either preserved or reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), patients were further evaluated by low-dose dobutamine stress and/or transoesophageal echocardiography. Coronary angiography was performed in all patients before surgery. The heart team was blinded for additional study data when routinely evaluating every patient and deciding whether or not to operate. Participants were assessed prior to a decision as to whether to undergo SAVR (baseline) and at 1 year after intervention or continued medical treatment (follow-up). After 5 years, mortality data were obtained from the Norwegian National Cause of Death Registry, resulting in a complete 3-year follow-up for all patients. The Regional Committee for Ethics in Medicine approved the study protocol, which also complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was registered in Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01794832).

Clinical data collection at baseline and 1-year follow-up

Data collected at baseline and follow-up comprised clinical and physical examinations including resting blood pressure, a standard resting 12-lead ECG, peripheral blood sampling and transthoracic echocardiography. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was calculated by the Canadian Stroke Network online calculator (http://www.strokengine.ca/assess/cci/), and the operative risk by the Euro(II)SCORE (Euro(II)SCORE, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation) (http://www.euroscore.org/calc.html). Functional status and/or symptoms of exertional dyspnoea or angina were assessed using the New York Heart Association functional class (NYHA) and the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) grade. Functional performance was assessed by the 6-minute walk test (6MWT). Questionnaires provided data forhealth-related quality of life (HRQoL), cognition (the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), current living conditions and degree of independence.

Transthoracic echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed using Vivid 7 or E9 ultrasound scanners (GE Vingmed Ultrasound, Horten, Norway). The severity of aortic valve stenosis was assessed by continuous wave Doppler through multiple acoustic windows in order to obtain the maximal jet velocity. Maximal instantaneous and mean pressure gradients across the aortic valve were measured using the time velocity integral, and the aortic valve area was estimated using the continuity equation. The modified biplane Simpson was used to calculate LVEF.

Measures of physical function, HRQoL and cognitive ability

In addition to functional status (NYHA) and performance (6MWT), we report a favourable composite endpoint comprising that proportion of patients with a status of NYHA I who lived independently, in their own house. For assessment of HRQoL, two generic instruments were included: the Short Form36 version 2 Health Survey (SF-36v2)and EuroQol 5-Dimension (EQ-5D). The SF-36v2 generates two summary scales: Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS). The EuroQol visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS) is an interval scale ranging from 0 to 100, with 100 indicating the best possible state of health. Patients were asked to rate their health status using this scale visualised as a thermometer. MMSE is an interview-based test on cognitive ability where any score above 25 (out of 30)8 indicates normal cognition, that is, no cognitive dysfunction.

Adverse clinical events and hospitalisation

We reviewed the medical records for all patients in the year following study inclusion. Data on adverse events (AEs) and hospitalisation were collected from patients’ operating and local hospitals. To avoid missing data, we also registered codes for diagnoses and procedures.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics are provided as means with SD, or medians with IQR, as appropriate. To compare the operated and unoperated patients, χ² tests were used for categorical data, with t-tests or Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables, where appropriate. Analyses of changes from baseline to follow-up were performed using χ² tests, or paired t-tests, again as appropriate. Cox regression analyses were performed to examine the associations between baseline variables and the risk of all-cause 3-year mortality, or the composite endpoint, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE; all-cause mortality, non-fatal transient ischaemic attack (TIA)/stroke or myocardial infarction (MI)), within a 1-year time frame following inclusion. Baseline variables included in multivariate analyses were selected based on existing litterature4 6 (online supplementary table 2 and online supplementary table 3). Time-to-event analyses were performed with the use of Kaplan-Meier estimates and compared with using the log-rank test. Data were analysed using STATA V.14. A p Value (two-sided) of less than 5% was considered statistically significant. A full description of the statistical analysis is included in the online supplementary material.

openhrt-2017-000588supp001.pdf (217.8KB, pdf)

openhrt-2017-000588supp002.pdf (88.4KB, pdf)

openhrt-2017-000588supp003.pdf (186.7KB, pdf)

Results

Clinical characteristics

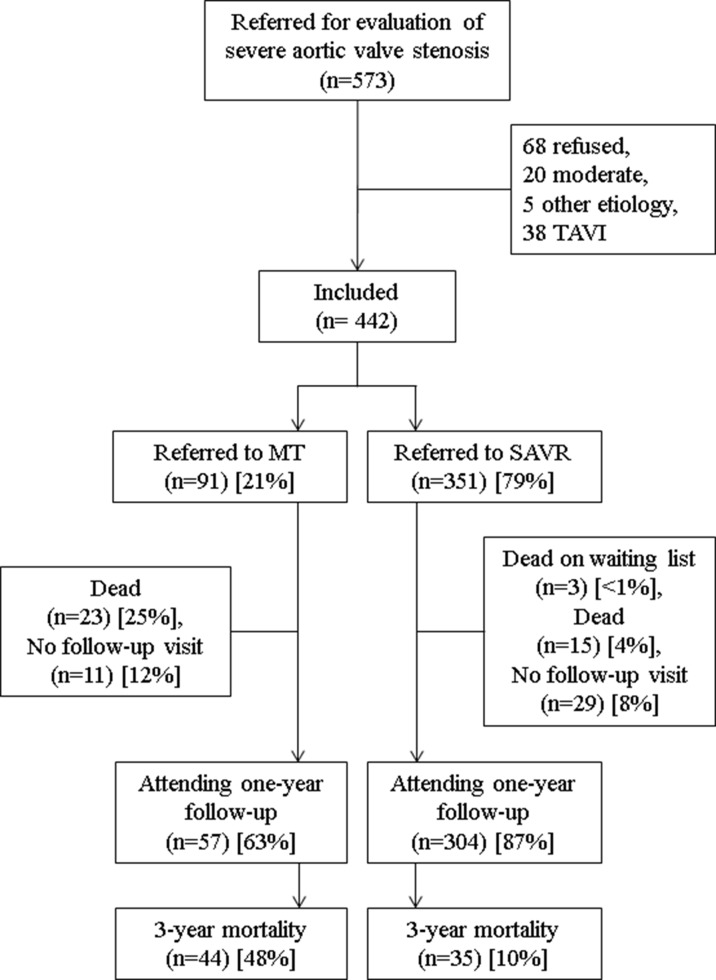

Of 573 consecutively registered eligible patients, 68 declined participation, 5 received other diagnoses, 20 had moderate AS, and 38 were excluded following referral for TAVR (figure 1). Among the 442 included patients, 91 (20.6%) did not undergo surgery, either because of a lack of symptoms (n=34), a high risk-benefit ratio (n=37) or refusal (n=20); the remainder, 351 (79.4%), underwent SAVR by standard full sternotomy. After referral, 3 patients died while awaiting SAVR. The transfusion rate (>4 units of red packed cells) was 17.5%. Among 17 (4.9%) patients staying >48 hours in intensive care, the median stay was 5 days (IQR: 3–8 days) and they were intubated for a median of 2.6 hours (IQR: 1.3–13.4 hours). Among those operated on, 279 (80.2%) received bioprosthetic valves, with concomitant bypass surgery performed in 103 (29.6%). For operated patients, the median (IQR) stay before transfer was 3 (3–4) days, and the time spent for continued postoperative recovery in local hospitals was 6 (4–11) days. After being discharged from their local hospitals, 21 (6.0%) patients were readmitted to receive care for either mediastinal or sternal wound-healing problems. A total of 304 (86.6%) operated and 57 (62.6%) unoperated patients attended 1-year follow-up at our centre (figure 1). Non-attenders in both groups were generally more comorbid, had higher serum levels of biomarkers, more symptoms and used more medication at baseline (online supplementary table 1). Baseline characteristics demonstrate that patients who underwent SAVR (vs those not operated on) were younger, had a higher body mass index, diastolic blood pressure, NYHA and CCS class (both worse), fewer comorbidities (heart failure, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus and kidney disease), used less medication (diuretics, warfarin and digitalis), had a lower Charlson Comorbidity Index score and Euro(II)SCORE (table 1). Echocardiography demonstrated higher cardiac output, aortic peak velocity and aortic mean gradient in operated patients, while estimated valve areas were comparable for both groups. Biochemical analyses revealed higher serumhaemoglobin and estimated glomerular filtration rate, while serumcreatinine, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and high-sensitive troponin T were lower in operated versus unoperated patients. In addition, operated patients scored higher (better) for HRQoL (PCS, EQ-5D index score), walked further on the 6MWT and had higher mean MMSE compared with unoperated patients at baseline.

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram. MT, medical treatment; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variables | All patients, n=442 | Surgical AVR, n=351 | Unoperated, n=91 | p Value |

| Demography | ||||

| Mean age, years | 74±11 | 73±10 | 81±9 | <0.0001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 249 (56) | 205 (58) | 44 (48) | 0.085 |

| Married or partner, n (%) | 270 (65) | 223 (67) | 47 (58) | 0.139 |

| Body mass index, kg/m² | 26±5 | 26±4 | 25±5 | <0.0001 |

| Medical history, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 202 (46) | 162 (46) | 40 (44) | 0.708 |

| Heart failure | 28 (6) | 17 (5) | 11 (12) | 0.011 |

| Atrial fibrillation, all types | 94 (21) | 65 (19) | 29 (32) | <0.006 |

| Diabetes mellitus type I and II | 48 (11) | 31 (9) | 17 (19) | <0.007 |

| Pulmonary disease | 77 (17) | 57 (16) | 20 (22) | 0.198 |

| Kidney disease | 25 (6) | 15 (4) | 10 (11) | 0.013 |

| Coronary artery disease | 131 (30) | 106 (30) | 25 (27) | 0.612 |

| Clinical findings | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 143±22 | 144±22 | 139±24 | 0.057 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 77±12 | 77±12 | 74±13 | 0.026 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 73±13 | 73±13 | 74±13 | 0.398 |

| Medication, n (%) | ||||

| Beta-blocker | 206 (47) | 157 (45) | 49 (54) | 0.120 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 178 (40) | 135 (38) | 43 (47) | 0.262 |

| Calcium antagonist | 89 (20) | 71 (20) | 18 (20) | 0.924 |

| Statin | 233 (53) | 192 (55) | 41 (46) | 0.101 |

| Diuretic | 165 (37) | 107 (30) | 58 (64) | <0.0001 |

| Warfarin | 90 (20) | 61 (17) | 29 (32) | 0.002 |

| Platelet inhibitor | 231 (52) | 190 (54) | 41 (45) | 0.122 |

| Digitalis | 31 (7) | 19 (5) | 12 (13) | 0.010 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| 0 | 177 (40) | 150 (43) | 27 (30) | |

| 1–2 | 213 (48) | 170 (48) | 43 (47) | |

| ≥3 | 52 (12) | 31 (9) | 21 (23) | |

| Surgical risk score | ||||

| Euro(II)SCORE, median ± IQR | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) | 4 (2–8) | <0.0001 |

| NYHA classification, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| Class I | 48 (11) | 21 (6) | 27 (30) | |

| Class II | 205 (46) | 176 (50) | 29 (32) | |

| Class III/IV | 189 (43) | 154 (44) | 35 (38) | |

| CCS grade, n (%) | 0.002 | |||

| Score 0 | 251 (57) | 186 (53) | 65 (71) | |

| Score 1–2 | 163 (37) | 144 (41) | 19 (21) | |

| Score 3–4 | 28 (6) | 21 (6) | 7 (8) | |

| Echocardiographic measures | ||||

| SWTd, cm | 1.1±0.2 | 1.1±0.2 | 1.1±0.2 | 0.472 |

| LVIDd, cm | 5.0±0.6 | 5.0±0.6 | 4.9±0.6 | 0.153 |

| PWTd, cm | 0.9±0.1 | 0.9±0.1 | 0.9±0.1 | 0.504 |

| LVEF, % | 56.2±9.2 | 56.4±8.6 | 55.1±11.2 | 0.227 |

| Cardiac output, L/min | 4.9±1.2 | 4.9±1.2 | 4.6±1.3 | 0.034 |

| Aortic peak velocity, m/s | 4.7±0.8 | 4.7±0.8 | 4.5±0.7 | 0.021 |

| Aortic mean gradient, mm Hg | 55±18 | 56±18 | 51±18 | 0.013 |

| Aortic valve area, cm² | 0.7±0.2 | 0.7±0.2 | 0.7±0.2 | 0.253 |

| Biochemical values | ||||

| Haemoglobin, g/dL | 13.6±1.6 | 13.8±1.5 | 13.1±1.9 | 0.0004 |

| Blood platelets, 109/L | 251±70 | 251±68 | 248±79 | 0.668 |

| hs-CRP, mg/L | 5.1±9 | 4.7±8 | 6.6±12 | 0.085 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.9±0.8 | 5.9±0.7 | 6.0±1.0 | 0.186 |

| Creatinine, µmol/L | 87±29 | 85±28 | 93±31 | 0.027 |

| eGFR, mL/min | 74±33 | 78±32 | 58±29 | <0.0001 |

| NT-pro-BNP, pmol/L, median (IQR) | 91 (33–234) |

71 (30–178) |

192 (58–402) |

<0.0001 |

| hs-TnT, ng/mL, median (IQR) | 14 (10–25) | 12 (10–22) | 19 (12–38) | <0.0001 |

| Quality of life | ||||

| Summary PCS | 39±11 | 39±10 | 36±13 | 0.009 |

| Summary MCS | 50±11 | 50±11 | 48±14 | 0.337 |

| EQ-5D UK index score | 0.72±0.22 | 0.73±0.21 | 0.65±0.27 | 0.001 |

| EQ-VAS score | 59±22 | 60±21 | 56±24 | 0.090 |

| 6-Min walk test, m | 446±133 | 460±127 | 374±144 | <0.0001 |

| MMSE score | 28.1±2.4 | 28.4±2.0 | 27.0±3.5 | <0.0001 |

Plus–minus values are means±SD. p Values for comparison between operated and unoperated patients.

ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; AVR, aortic valve replacement; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (Cockcroft-Gault formula); EQ-5D UK, EuroQol 5-Dimension United Kingdom; Euro(II)SCORE, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c; EQ-VAS, EuroQol visual analogue scale; hs-CRP, high-sensitive C-reactive protein; hs-TnT, high-sensitive troponin T; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVIDd, left ventricular internal dimension at end diastole; MCS, Mental Component Summary; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCS, Physical Component Summary; PWTd, posterior wall thickness at end-diastole; SWTd, septal wall thickness at end-diastole.

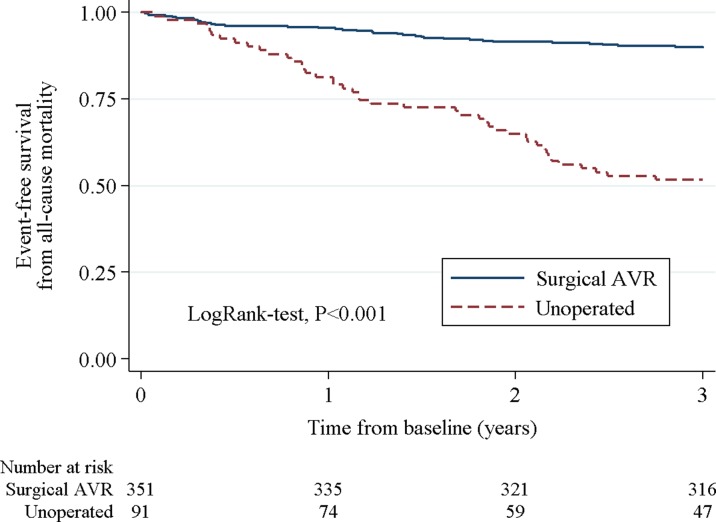

Survival, symptom improvement and quality of life

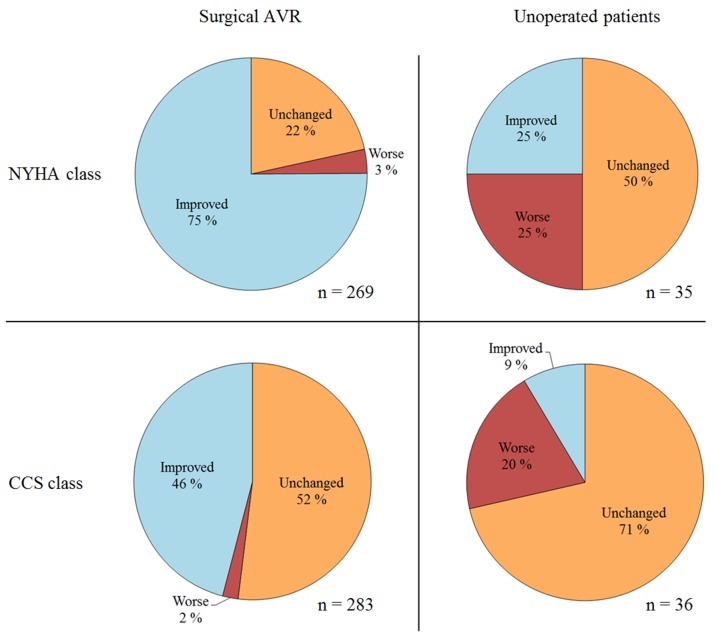

Overall survival 3 years after SAVR was 90%. Thirty-day mortality was <1%. Survival curves for operated and unoperated patients are displayed in figure 2. Compared with patients who underwent isolated SAVR, 3-year mortality was not significantly different in those who underwent concomitant bypass surgery (p=0.626). Among unoperated individuals, the 3-year mortality was 48.4% (29.5% in patients without symptoms, 67.6% in high-risk patients and 45.0% in patients refusing intervention). In multivariate cox regression analyses, higher age (HR: 1.05, CI 1.01 to 1.10, p=0.003) and LVEF (HR: 0.97, CI 0.94 to 1.00, p=0.012) were associated with death among those operated on, whereas in unoperated patients LVEF (HR: 0.97, CI 0.95 to 1.00, p=0.044) and coronary artery disease (CAD) (HR: 2.18, CI 1.10 to 4.32, p=0.025) were associated (online supplementary table 2). At follow-up, 1 year after surgery, symptoms were significantly decreased (less), with 75% and 46% of patients improving by at least one class for NYHA and CCS, respectively (table 2, figure 3). Self-perceived physical HRQoL, as measured by PCS, improved significantly in operated patients, while remaining unchanged among unoperated patients. Furthermore, overall general HRQoL, as assessed by the EQ-5D UK index score and EQ-VAS, improved among operated patients, with no change observed for unoperated patients (table 2).

Figure 2.

Change in symptoms in operated and unoperated patients 1 year following evaluation of surgical AVR. Pie charts display change from baseline to follow-up in NYHA and CCS class for operated and unoperated patients who had data on both time points. Improvement or worsening is defined as at least one class change. AVR, aortic valve replacement; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Table 2.

Changes in symptoms, functional performance, echocardiographic measurements, patient-reported outcomes, cognitive ability, current living conditions and degree of independence from baseline to 1-year follow-up among patients with results on both time points

| Surgical AVR | Unoperated | |||||||

| Paired* | BL | FU | p Value† | Paired* | BL | FU | p Value† | |

| NYHA class | 269 (76.7) | <0.0001 | 36 (39.6) | 0.756 | ||||

| I | 15 (5.6) | 188 (69.9) | 11 (30.6) | 12 (33.3) | ||||

| II | 142 (5.8) | 62 (23.0) | 15 (41.7) | 12 (33.3) | ||||

| III or IV | 112 (41.6) | 19 (7.1) | 10 (27.7) | 12 (33.3) | ||||

| CCS class | 283 (80.6) | <0.0001 | 35 (38.5) | 0.355 | ||||

| 0 | 152 (53.7) | 272 (96.1) | 28 (80.0) | 30 (85.7) | ||||

| I or II | 115 (40.6) | 10 (3.5) | 5 (14.3) | 5 (14.3) | ||||

| III or IV | 16 (5.7) | 1 (<1) | 2 (5.7) | 0 (0) | ||||

| 6-Min walk test distance, m | 217 (61.8) | 466±123 | 444±132 | 0.0001 | 23 (25.3) | 412±171 | 369±141 | 0.046 |

| Echocardiography | 254 (72.4) | |||||||

| SWTd, cm | 1.1±0.2 | 1.0±0.2 | <0.0001 | 51 (56.0) | 1.2±0.2 | 1.2±0.2 | 0.913 | |

| LVIDd, cm | 5.0±0.6 | 4.9±0.5 | <0.0001 | 51 (56.0) | 4.9±0.6 | 4.9±0.7 | 0.391 | |

| PWTd, cm | 0.9±0.1 | 0.8±0.1 | <0.0001 | 51 (56.0) | 0.9±0.1 | 0.9±0.2 | 0.924 | |

| LVEF, % | 56.6±8.5 | 58.1±8.0 | 0.001 | 50 (54.9) | 56.3±11.2 | 55.1±11.7 | 0.302 | |

| Patient-reported outcomes | ||||||||

| PCS | 231 (65.8) | 40±10 | 47±11 | <0.0001 | 33 (36.2) | 37±13 | 34±12 | 0.064 |

| MCS | 231 (65.8) | 51±11 | 51±12 | 0.957 | 33 (36.2) | 49±13 | 46±14 | 0.208 |

| EQ-5D UK index score | 260 (74.0) | 0.74±0.2 | 0.79±0.2 | 0.01 | 45 (49.5) | 0.69±0.3 | 0.62±0.2 | 0.13 |

| EQ-VAS | 245 (69.8) | 61±21 | 73±18 | <0.0001 | 37 (40.7) | 62±25 | 57±24 | 0.153 |

| Cognitive ability | 283 (80.6) | 42 (46.2) | ||||||

| MMSE | 28.4±2.0 | 28.1±2.4 | 0.032 | 27.4±2.9 | 26.9±3.6 | 0.113 | ||

| MMSE <25‡ | 9 (3.2) | 25 (8.8) | 0.005 | 5 (11.9) | 9 (21.4) | 0.242 | ||

| Living independently at home in NYHA class I | 289 (82.3) | 16 (5.5) | 142 (49.1) | – | 48 (52.7) | 11 (22.9) | 6 (12.5) | <0.0001§ |

*Paired indicates patients with results at baseline and 1-year follow-up.

†p Values for comparison of results at baseline and follow-up.

‡Patients scoring 25 points or less on MMSE.

§p Value for comparison of operated versus unoperated patients at follow-up.

Plus–minus values are means ±SD, absolute frequencies and (%) proportion of group.

AVR, aortic valve replacement; BL, baseline; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; EQ-5D UK, EuroQol 5-Dimension United Kingdom; EQ-VAS, EuroQol visual analogue scale; FU, follow-up; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVIDd, left ventricular internal dimension at end-diastole; MCS, Mental Component Summary; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCS, Physical Component Summary; PWTd, posterior wall thickness at end-diastole; SWTd, septal wall thickness at end-diastole.

Figure 3.

Overall 3-year survival in operated and unoperated patients with severe aortic stenosis. AVR, aortic valve replacement.

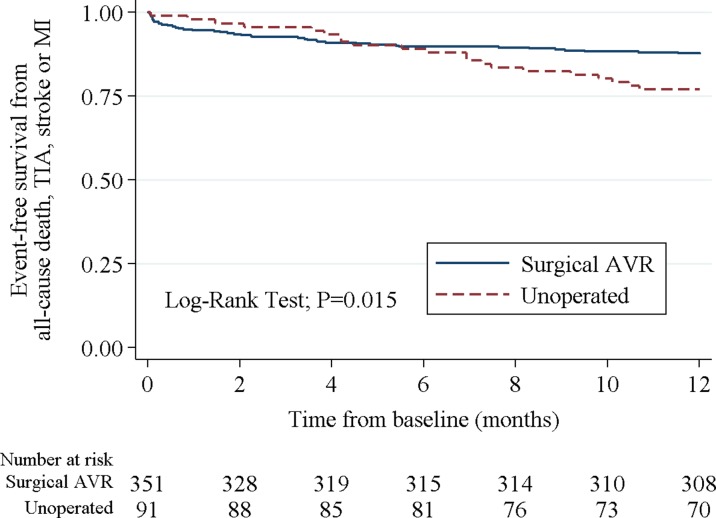

Adverse events and hospitalisation

The composite of cardiovascular AEs as defined by MACE was met by 43 (12.3%) patients in the year following SAVR, and the incidence rate (IR) per 100 patient-years was 13.5 (table 3, figure 4). Among unoperated patients, 21 (23.1%) experienced MACE (IR: 26.3). CAD was the only covariate in multivariate cox regression analyses to have an association with MACE in operated patients (HR: 2.06, CI 1.09 to 3.89, p=0.027) and unoperated patients (HR: 3.94, CI 1.44 to 10.77, p=0.002) (online supplementary table 3). Although the number of AEs was similar in both groups, the IR for antibiotic-requiring infections was twofold greater in the operated group (IR: 47.2) versus the unoperated group (IR: 18.9) (p=0.0001). Conversely, the number of MIs was lower among operated (IR: 1.2) than unoperated (IR: 12.1) patients (p<0.0001). Rehospitalisation within 30 days of discharge occurred more often for operated than unoperated patients (26% vs 2%, p<0.0001). However, for all hospitalisations within the first year, the median length of stay was longer among unoperated than operated patients (14 days (6–24) vs 6 (3–14), p=0.002). The number of patients hospitalised at least once during the 1-year observation period was 148 (42.2%) for the operated group versus 41 (45.1%) for the unoperated group (p=0.411).

Table 3.

Adverse events in operated and unoperated patients with severe aortic stenosis in the year following inclusion

| Event | Surgical AVR, n=351 | Unoperated, n=91 | |||||

| n (%) |

Time at

risk (years) |

Rate/time * | n (%) |

Time at

risk (years) |

Rate/time * | p Value † | |

| All-cause mortality | 16 (4.6) | 340 | 4.7 | 17 (18.7) | 83 | 20.4 | <0.0001 |

| MACE | 43 (12.3) | 318 | 13.5 | 21 (23.1) | 80 | 26.3 | 0.009 |

| TIA | 8 (2.3) | 335 | 2.4 | None | 83 | None | 0.084 |

| Stroke | 21 (6.0) | 325 | 6.5 | 3 (3.3) | 83 | 3.6 | 0.179 |

| TIA or stroke | 28 (8.0) | 322 | 8.7 | 3 (3.3) | 83 | 3.6 | 0.065 |

| New pacemaker | 21 (6.0) | 324 | 6.5 | 6 (7.7) | 79 | 7.6 | 0.359 |

| Myocardial infarction | 4 (1.1) | 338 | 1.2 | 10 (11.0) | 83 | 12.1 | <0.0001 |

| Endocarditis | 8 (2.3) | 335 | 2.4 | 1 (1.1) | 84 | 1.2 | 0.286 |

| Antibiotic-requiring infection | 116 (33.0) | 246 | 47.2 | 15 (16.5) | 80 | 18.9 | 0.0001 |

| Cardiac hospitalisation‡ | 32 (9.1) | 322 | 9.9 | 27 (29.7) | 77 | 35.1 | <0.0001 |

| All-cause hospitalisation‡ | 148 (42.2) | 237 | 62.4 | 41 (45.1) | 68 | 60.3 | 0.411 |

| Any-cause 30-day rehospitalisation§ | 90 (25.6) | 292§ | 31.8§ | 2 (2.2) | 85§ | 2.4§ | <0.0001 |

*Rate per 100 patient-years.

†p Values for comparison of incidence rates in operated and unoperated patients.

‡Hospitalisation defined as at least an overnight stay.

§Thirty days counting from discharge after postoperative recovery in local hospital, or from inclusion date for unoperated patients. Time at risk per 30 days and rate per 100 patient months.

AVR, aortic valve replacement; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event (see definition in the Methods section); TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Figure 4.

Event-free survival from major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) in operated and unoperated patients with severe aortic stenosis. MACE is defined as time to all-cause death, transient ischaemic attack (TIA), stroke or myocardial infarction (MI). AVR, aortic valve replacement.

Measures of functional performance, independence and cognitive ability

Changes in functional performance and cognitive ability, from baseline to 1-year follow-up, are displayed in table 2. After SAVR, the mean walking distance on the 6MWT test decreased from baseline to follow-up by 26 m (baseline: 466±123 m vs follow-up: 444±132 m, p=0.0001). At follow-up, 95.0% of operated and 89.8% of unoperated patients lived in their own home (p=0.146). The proportion of operated patients experiencing a favourable composite of function and independence (living alone, without minor or major assistance and functional in NYHA class I) increased significantly from baseline to follow-up, although this was only attainable for almost half of the patients (16 of 289 (5.5%) vs 142 of 289 (49.1%), p<0.0001) (table 2).

The proportion of patients developing a cognitive disability as defined by a cut-off of 25 points or less8 on the MMSE increased significantly when retested at follow-up (baseline 3.2% vs follow-up 8.8%, p=0.005). And although the mean values at baseline and 1-year follow-up were above the cut-off, there was a decrease in the mean MMSE score from 28.4 to 28.1 (p=0.032).

Geometry and function of left ventricle

The results indicate that wall thicknesses were decreased and LVEF increased for operated patients at follow-up. In contrast, no significant changes in geometric measurements or LVEF were observed in unoperated patients (table 2).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort, it was confirmed that for patients with severe AS and low and intermediate surgical risk, SAVR provides symptom relief, improve HRQoL, provoke reverse ventricular remodelling and is associated with a significant survival benefit at subsequent follow-up. Although the aforementioned outcomes have been reported in numerous previous studies, there are few reports describing morbidity and hospitalisation following SAVR. Postsurgical incidences of AEs after SAVR have been reported in large registry studies,9 in high-risk patients10 and elderly subjects.11 Results in this cohort provide such data in patients with low to intermediate surgical risk. In this study, more than a quarter of patients underwent a rehospitalisation within 30 days of postsurgical discharge, and about one-third were subjected to antibiotic-requiring infections in the year following surgical intervention. Interestingly, these numbers were higher than for unoperated patients who were significantly older and had more comorbidities. Moreover, the risks of all-cause hospitalisation during the first year were comparable between the two patient groups, suggesting that the postoperative rehabilitation and hospitalisations related to the intervention constitute a non-negligible morbidity burden in the first postoperative year. As demonstrated in table 3, among the registered AEs, antibiotic-requiring infections were the leading cause of all-cause hospitalisation during the first year after SAVR. On the basis of our retrospective analysis of AEs, we cannot conclude whether these infections (mainly pneumonias) had a strong indication for initiating antibiotic treatment, but nevertheless these events made a considerable contribution to the overall morbidity. In terms of cerebrovascular events, the incidences of TIA and stroke in our cohort were somewhat higher than was reported during the 1-year follow-up in a cohort study of Wenaweser et al,10 where patients had considerably higher surgical risk. This finding suggests closer preoperative attention to risk factors.

Although most patients view survival as their main outcome when deciding to accept the risk of undergoing heart surgery, some may be concerned with other outcomes, such as the independence from home nursing. To address this, we report the proportion of patients attaining the composite of being symptom-free (NYHA class I) and having reclaimed their independence of daily life at 1-year follow-up. At baseline, 5.5% of operated patients attained this composite and 49.1% at follow-up, suggesting that the chances of reclaiming symptom-free daily life are relatively high, but not attainable for all patients after SAVR. Another more commonly reported measure of functional status is NYHA, which has several limitations and is proposed to neither be a true reflection of functional capacity nor functional performance, as several factors influence individuals’ daily life.12 In this study, the 6MWT and NYHA were measured, and interestingly the two measurements diverged. Although there was a significant improvement in the NYHA classification, the 6MWT distance was decreased compared with baseline performance. Although one might expect a stronger correlation between improvement in NYHA and the 6MWT, these instruments measure conceptually different aspects of physical function and their correlation coefficient is weak.13 Other than methodological errors, this rather unanticipated finding may be explained by a restrain of physical performance due to an abnormal tissue calcification of the entire cardiovascular system,14 a pathological process that may persist to inhibit walking performance on the 6MWT 1 year after valve replacement.

Despite the AEs, operated patients reported an increased mean PCS, EQ-5D UK index and EQ-VAS 1 year after SAVR. One study proposed that a meaningful change in the PCS is 4–7 points,15 which translates into an improvement for operated patients and a non-significant decline for unoperated patients. Compared with SF-36v2, the EQ-5D is primarily a supplementary tool because of its low sensitivity.16 Nevertheless, changes reported in this cohort suggest an overall improvement in operated patients and no change among unoperated patients. The mean MMSE score decreased in both groups at follow-up, but without reaching a ‘meaningful change’ of 2–4 points.17 However, the proportion of operated patients who scored >25 points was significantly increased at follow-up, suggesting a non-negligible consequence of SAVR on cognitive function.

The survival benefit of undergoing SAVR for patients with severe symptomatic AS has been established by previous studies.18 The 90.0% survival rate at 3 years reported in this study is slightly higher than is reported in other comparable cohorts. In a recent publication,19 3-year survival after SAVR was 83.4%, despite having the same proportion of patients aged >70 years (67.0%), and fewer patients with a medium-risk or high-risk Euro(II)SCORE. Mortality during the natural disease course of severe AS is largely derived from historic reports,20 21 with more recent data collected for elderly patients with an increased risk.22 A study demonstrating the beneficial effect of SAVR on survival in octogenarians with severe AS revealed that mortality at a median of 2.5 years was 33% in the AVR group and 64% in the conservatively treated group.23 The relatively low mortality among operated individuals in the present cohort could be attributed to lower age and lower surgical risk compared with other series.

Limitations

This relatively large cohort has some limitations. First, this is not a randomised trial, and therefore the comparison of operated and unoperated patients is only useful in the sense that this study aims to provide contemporary data from the complex clinical reality at a tertiary centre. Second, it is likely that patients were self-selected as individuals motivated to seek a referral to a tertiary centre (ie, introducing bias). Third, the patient population was quite heterogeneous; operated patients had low to intermediate risk, and among unoperated patients there were both very high risk (declined intervention) and lower risk (asymptomatic, and those refusing intervention) individuals.

Conclusion

The increased survival benefit, symptom relief and overall improvement in quality of life after undergoing SAVR are confirmed in this relatively large cohort of patients with severe, symptomatic AS. However, in this study, surgical intervention was associated with a considerable amount of postoperative adverse clinical events and hospitalisations, even surpassing event rates for unoperated patients. Furthermore, the results indicate that most patients considering SAVR at a modern-day tertiary centre can expect their cognitive function and symptom-free independence of daily life to be preserved after the postoperative rehabilitation period. Not undergoing AVR was associated with poor outcomes, and this study serves as a reminder of the importance of careful clinical assessment and proper treatment recommendation for all patients with severe AS. In respect to future randomised controlled trials with TAVR versus SAVR, this description of current complex clinical practice may provide a comparative background for evaluating outcomes in the era of individualised patient care.

Acknowledgments

Wenche Stueflotten (guarantor), Sonia Aslam and Caroline Rudi provided important assistance in terms of data collection and logistic flow of study participants.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Regional Ethics Committee (REK sør-øst).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, et al. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet 2006;368:1005–11. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69208-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kodali SK, Williams MR, Smith CR, et al. ; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Two-year outcomes after transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1686–95. 10.1056/NEJMoa1200384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease.J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;2014:e1–e132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Andreotti F, et al. ; Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). Eur Heart J 2012;33:2451–96. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rashedi N, Otto CM. Aortic stenosis: changing disease concepts. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2015;23:59–69. 10.4250/jcu.2015.23.2.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bouma BJ, van Den Brink RB, van Der Meulen JH, et al. To operate or not on elderly patients with aortic stenosis: the decision and its consequences. Heart 1999;82:143–8. 10.1136/hrt.82.2.143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shan L, Saxena A, McMahon R, et al. A systematic review on the quality of life benefits after aortic valve replacement in the elderly. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;145:1173–89. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Woodford HJ, George J. Cognitive assessment in the elderly: a review of clinical methods. Qjm 2007;100:469–84. 10.1093/qjmed/hcm051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mohr FW, Holzhey D, Möllmann H, et al. ; GARY Executive Board. The german aortic valve registry: 1-year results from 13,680 patients with aortic valve disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;46:808–16. 10.1093/ejcts/ezu290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wenaweser P, Pilgrim T, Kadner A, et al. Clinical outcomes of patients with severe aortic stenosis at increased surgical risk according to treatment modality. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:2151–62. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.05.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carnero-Alcázar M, Reguillo-Lacruz F, Alswies A, et al. Short- and mid-term results for aortic valve replacement in octogenarians. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2010;10:549–54. 10.1510/icvts.2009.218040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bennett JA, Riegel B, Bittner V, et al. Validity and reliability of the NYHA classes for measuring research outcomes in patients with cardiac disease. Heart Lung 2002;31:262–70. 10.1067/mhl.2002.124554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Myers J, Zaheer N, Quaglietti S, et al. Association of functional and health status measures in heart failure. J Card Fail 2006;12:439–45. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Otto CM, Prendergast B. Aortic-valve stenosis--from patients at risk to severe valve obstruction. N Engl J Med 2014;371:744–56. 10.1056/NEJMra1313875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deutsch MA, Bleiziffer S, Elhmidi Y, et al. Beyond adding years to life: health-related quality-of-life and functional outcomes in patients with severe aortic valve stenosis at high surgical risk undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Curr Cardiol Rev 2013;9:281–94. 10.2174/1573403X09666131202121750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centre for Health Economics, University of York, York Y01 5DD UK. The EuroQol Group. EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hensel A, Angermeyer MC, Riedel-Heller SG. Measuring cognitive change in older adults. do reliable change indices of the SIDAM predict dementia? J Neurol 2007;254:1359–65. 10.1007/s00415-007-0549-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schwarz F, Baumann P, Manthey J, et al. The effect of aortic valve replacement on survival. Circulation 1982;66:1105–10. 10.1161/01.CIR.66.5.1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thyregod HG, Holmberg F, Gerds TA, et al. Heart team therapeutic decision-making and treatment in severe aortic valve stenosis. Scand Cardiovasc J 2016;50:146–53. 10.3109/14017431.2016.1148825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ross JR, Braunwald E. Aortic stenosis. Circulation 1968;38:61–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Horstkotte D, Loogen F. The natural history of aortic valve stenosis. Eur Heart J 1988;9 Suppl E:57–64. 10.1093/eurheartj/9.suppl_E.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. ; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1597–607. 10.1056/NEJMoa1008232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Piérard S, Seldrum S, de Meester C, et al. Incidence, determinants, and prognostic impact of operative refusal or denial in octogenarians with severe aortic stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:1107–12. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.12.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

openhrt-2017-000588supp001.pdf (217.8KB, pdf)

openhrt-2017-000588supp002.pdf (88.4KB, pdf)

openhrt-2017-000588supp003.pdf (186.7KB, pdf)