Abstract

Background:

Since 1998, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) has supported more rapid implementation of research into clinical practice.

Objectives:

With the passage of the Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act of 2014 (Choice Act), QUERI further evolved to support VHA’s transformation into a Learning Health Care System by aligning science with clinical priority goals based on a strategic planning process and alignment of funding priorities with updated VHA priority goals in response to the Choice Act.

Design:

QUERI updated its strategic goals in response to independent assessments mandated by the Choice Act that recommended VHA reduce variation in care by providing a clear path to implement best practices. Specifically, QUERI updated its application process to ensure its centers (Programs) focus on cross-cutting VHA priorities and specify roadmaps for implementation of research-informed practices across different settings. QUERI also increased funding for scientific evaluations of the Choice Act and other policies in response to Commission on Care recommendations.

Results:

QUERI’s national network of Programs deploys effective practices using implementation strategies across different settings. QUERI Choice Act evaluations informed the law’s further implementation, setting the stage for additional rigorous national evaluations of other VHA programs and policies including community provider networks.

Conclusions:

Grounded in implementation science and evidence-based policy, QUERI serves as an example of how to operationalize core components of a Learning Health Care System, notably through rigorous evaluation and scientific testing of implementation strategies to ultimately reduce variation in quality and improve overall population health.

Key Words: quality of care, access to care, evidence-based medicine, organization and delivery of care, research and technology

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), part of the cabinet-level US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), is the largest integrated health system in the United States. VHA serves approximately 9 million patients through its network of over 1600 facilities, 20,000 physicians, and 288,000 employees.1 One of the persistent challenges for VHA, as for other large health systems, is rapidly adapting to new knowledge and ensuring consistent quality across different settings. Over the past 2 years, VHA has been rocked by scandals involving extended waiting times for care, manipulated data, and quality problems at specific facilities.2 Although evidence suggests that quality and patient satisfaction in the VHA remain comparable with the private sector,3,4 neither were consistent across its medical centers, nor was VHA perceived to have kept pace with other health care industry leaders.2

Subsequently VHA is undergoing substantial transformations in the ways it provides health care, notably with the passage of the Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act of 2014 (“Choice Act”)5 in 2014, and the establishment of community provider networks. The Choice Act was passed in response to widespread concern in gaps in quality of care that were highlighted by media reports in which a VA whistleblower attributed the deaths of 40 veterans to long waiting times at the Phoenix VA Health Care System. A report by the VA Office of the Inspector General found significant gaps in access to care due in part to widespread variation in quality of care.6 Subsequent recommendations stemming from the Choice Act’s mandated external evaluation of VHA7 and Commission on Care8 also include establishment of a clearer path for VHA to implement “best practices” consistently to reduce variation in quality. VHA responded to recommendations to expand access to care by establishing the Office of Community Care to consolidate purchased care services as well as promote coordination of services across VA and non-VA providers by establishing community provider networks.

VHA’s Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI), established in 1998, was an internal funding program intended to help VHA address the challenge of translating research knowledge into practice more quickly and consistently.9 QUERI comprises a national network of academically affiliated scientists who are funded by VHA to work closely with national, regional, and facility-level leaders on projects aimed to rapidly implement effective clinical practices into routine care and evaluate the results of those implementation efforts.10 Essential to QUERI’s role is the deployment of implementation strategies, which are highly specified, scientific approaches that help providers and health systems adopt effective practices. Many of these strategies are derived from the growing field of implementation science,11 an interdisciplinary field comprised of public health, informatics, sociology, economics, psychology, and clinical expertise that seeks to understand and act on organizational, provider, and consumer-level barriers and facilitators to implementation of effective practices.12,13

Since its inception, QUERI has responded to the changing needs of VHA. With the passage of the Choice Act, VHA is undergoing an unprecedented reorganization that has not been seen in a generation. Specifically, the Choice Act’s Section 101 allows Veterans enrolled in VHA care waiting for longer than 30 days or living >40 miles from a VHA clinic the option to seek care from non-VHA health providers.6 The Choice Act also mandated an independent assessment (Section 201) of VHA business and health care practices. The report produced from this independent assessment7 was released in September 2015 and included a number of strong recommendations. The one most salient to QUERI in particular (and to health system scientists in general) was that VHA reduces variation in care by providing a clear path to implement existing best practices, especially across facilities with lower quality of care scores. In addition, the Choice Act mandated the establishment of a VHA Commission on Care (Section 202) to comprehensively assess and make recommendations for how to best organize and deliver VHA care over the long term. One of the strongest recommendations to come out of the Commission on Care’s final report8 was the establishment of community provider networks, accessible to Veterans through use of a Choice Card, implemented as a result of Choice Act Section 101. The establishment of these networks was seen as an alternative to privatization of the VA by allowing VA to formalize relationships with non-VA providers, and represents VHA’s move toward becoming a payer and provider of health care.8

This paper describes how QUERI is responding to the Choice Act, notably through use of scientific-supported implementation strategies to promote more rapid uptake of effective practices across different settings, as well as use of rigorous evaluation of new VHA programs/policies, to ultimately improve Veteran health. As a national program, QUERI responded to major Choice Act mandates in 3 ways: (1) by continuing to work with frontline providers to promote implementation of effective practices into routine clinical care to enhance access and quality of care; (2) support rigorous evaluations on the Choice Act implementation and other VA programs/policies; and (3) create a national network of implementation Programs, or “laboratories” to continue to support VHA’s efforts to more rapidly implement research into practice more consistently. Knowledge, tools, and methods produced through these goals in turn inform the interdisciplinary fields of implementation science and evidence-based policymaking.

QUERI is in a unique position to support and respond to VHA’s implementation of the Choice Act, by funding scientists who are embedded in the VHA health care system to support scientific studies that are aligned with VHA clinical and policy goals. QUERI investigators develop, deploy, and evaluate implementation of effective practices in close partnership with VHA clinical operations leaders. In doing so, QUERI strives to support VHA’s transformation through the National Academy of Medicine Learning Health Care System framework,12 which is composed of continuous learning cycles where data generated from delivering health care are used to create evidence to improve care, which in turn is applied to further promote the spread of effective practices systematically. To this end, QUERI can serve as an example of how other health care systems can both deploy and study new practices/policies simultaneously using implementation science and rigorous evaluation methods.

METHODS

At its inception in 1998, QUERI focused on how to deploy best practices in response to VHA’s major transformation in the 1990s from a hospital-based to a primary care–based system.13 During this time, QUERI emphasized implementation of evidence-based clinical practices for conditions that were most burdensome to Veterans, including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and mental disorders.9 QUERI promoted these best practices by building formal connections between research and operations through disease-focused, investigator-initiated projects and strategic planning.14

However, QUERI’s disease-focused centers limited its ability to address cross-cutting areas that would ensure consistent quality across sites throughout a complex health system. As a result, and in response to the Choice Act as well as its own strategic planning process, QUERI reorganized in 2015 to be nimbler and more responsive to changing VHA priorities, addressing issues such as access, timeliness, and coordination of care in a changing Veteran population that suffers from multiple chronic and acute care concerns.

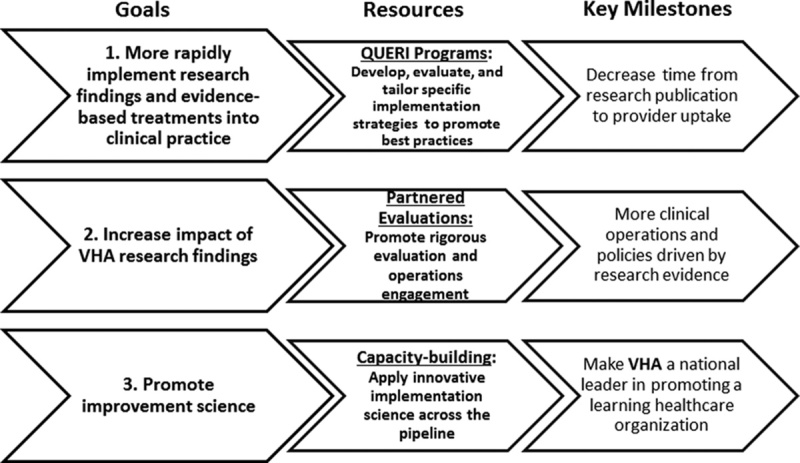

To this end, QUERI’s national priority goals were updated (Fig. 1):

FIGURE 1.

QUERI national strategic goals: accelerating research impact in a Learning Health Care System. QUERI indicates Quality Enhancement Research Initiative; VHA, Veterans Health Administration.

Rapidly translate research findings or evidence-based treatments (best practices) into clinical practice.

Increase impact of VHA research findings through bidirectional partnership, rigorous evaluation, and communication with all levels in the VHA.

Make VHA a national leader in promoting a Learning Health Care System through innovative implementation science.

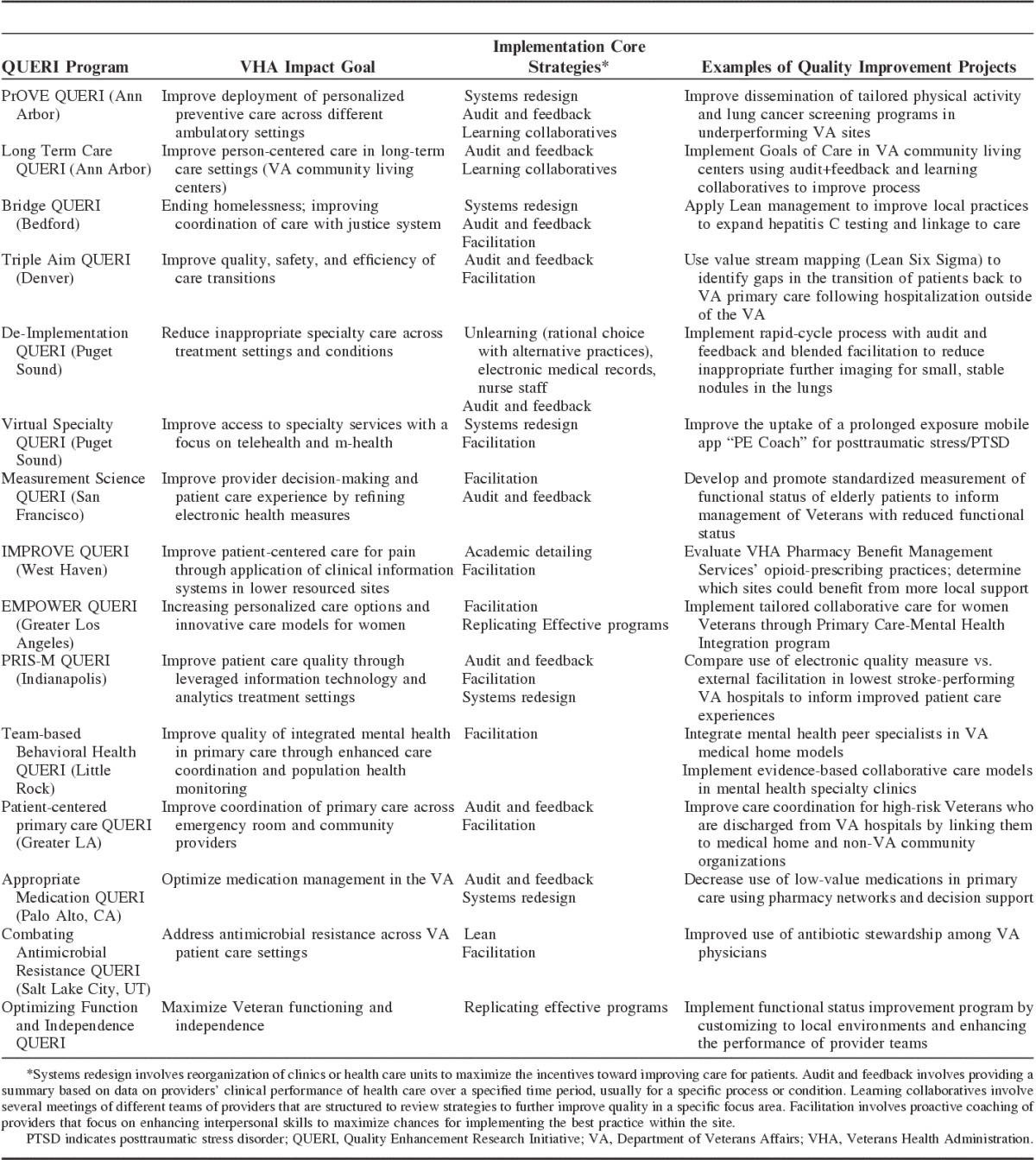

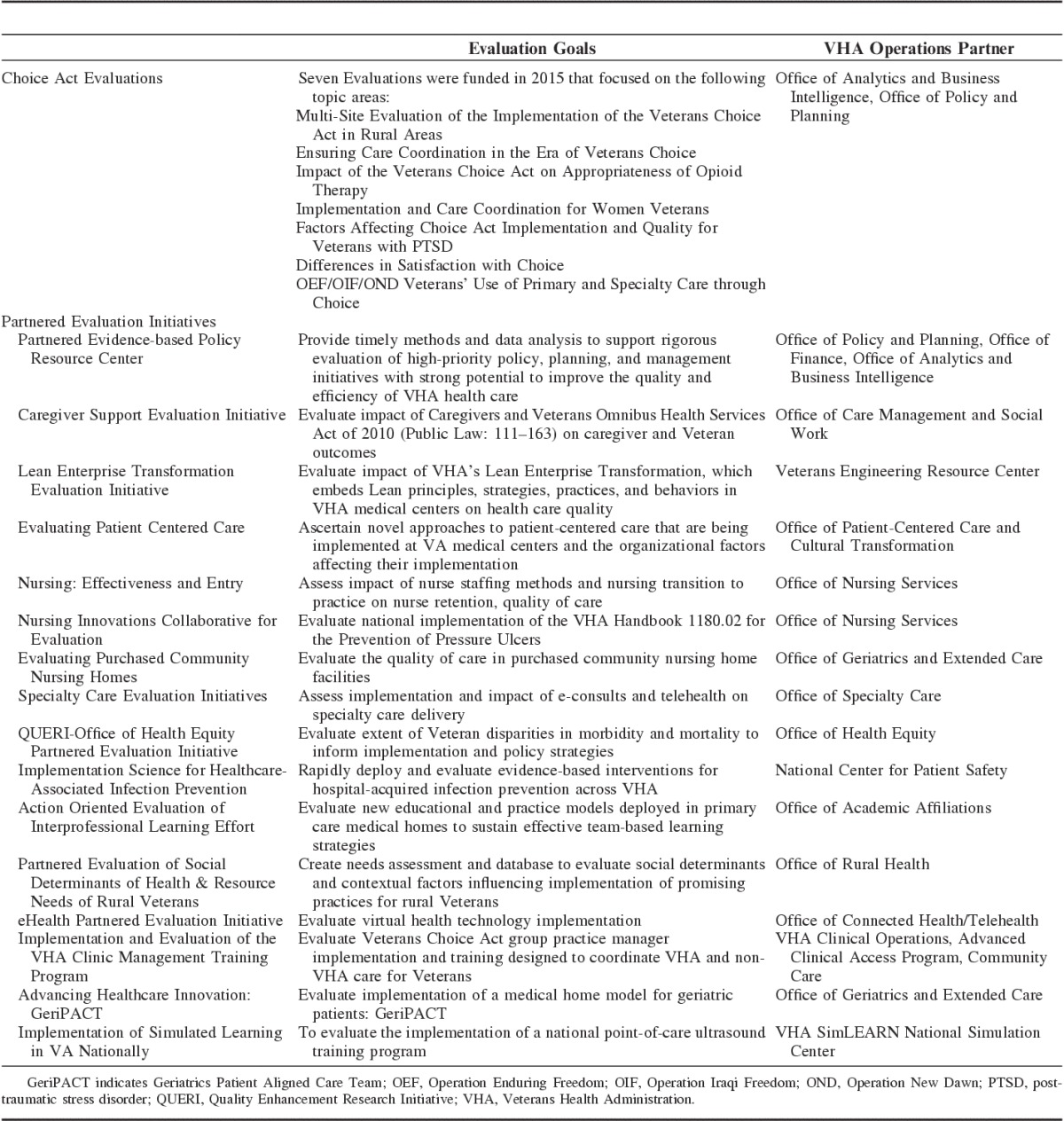

Each goal was operationalized by funding a national network of QUERI field-based Programs in 2015 that serve as laboratories for developing and testing scientifically based implementation strategies (Table 1) to facilitate uptake of effective practices more consistently across different sites. These Programs were updated versions of its disease-focused Centers and were in response to the Choice Act’s Section 201 integrated report recommendations. These goals also led to the funding of several Partnered Evaluations in collaboration with VHA clinical operations to rigorously assess impact of the Choice Card implementation and other VA programs/policies on Veteran care (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

National Network of QUERI Programs

TABLE 2.

QUERI Choice Act and Partnered Evaluation Initiatives

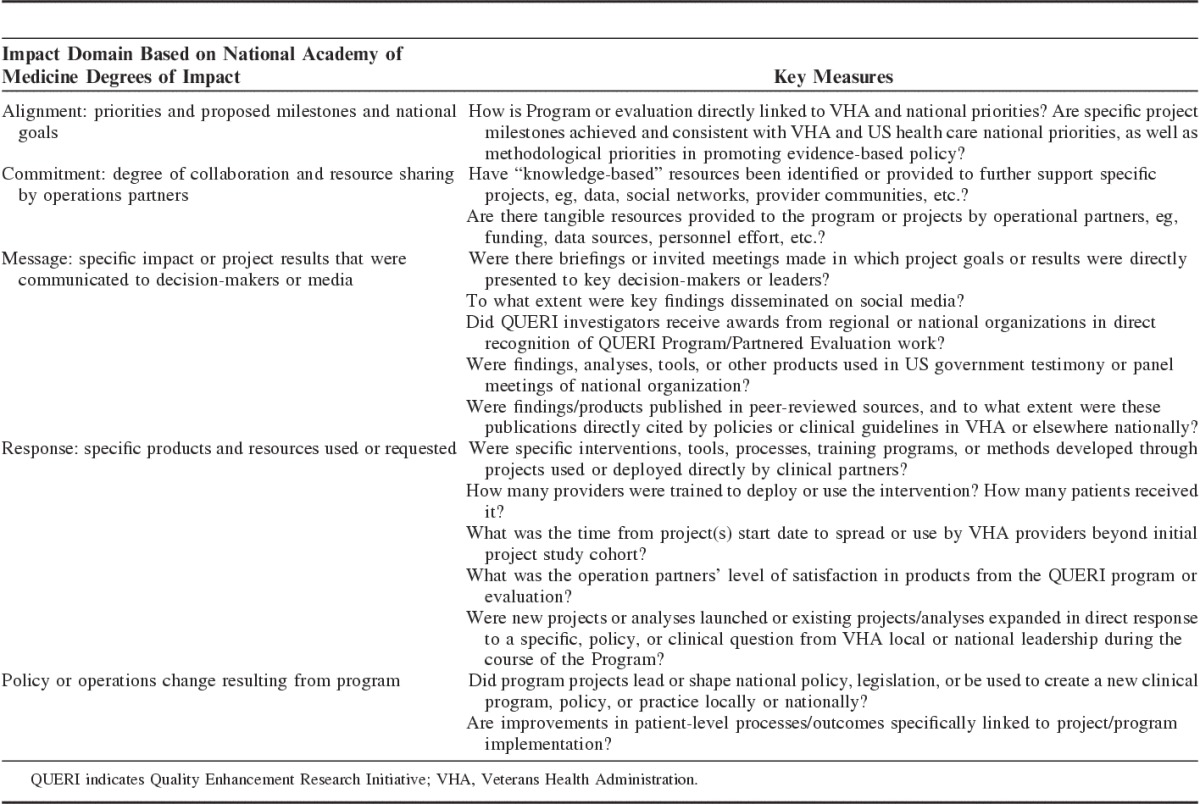

QUERI’s progress toward achieving these goals is assessed using measures derived from the National Academy of Medicine Degrees of Impact framework (Table 3).15 These measures seek to assess the impact of work performed across Programs and Partnered Evaluation Initiatives, including products, methods, or tools that are used by providers, as well as national changes in programs or policies resulting from the work in VHA and beyond.

TABLE 3.

QUERI Impact Metrics

National Network of QUERI Programs

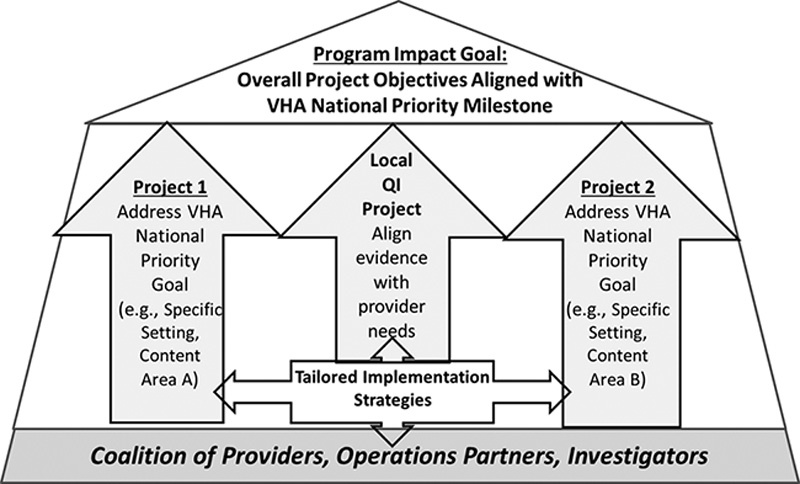

Strategic goal 1 is accomplished by supporting the national network of QUERI Programs (Table 1). The overall architecture of the QUERI Programs is depicted in Figure 2. Each Program is led by investigators in partnership with clinical operations leaders and providers that focus on achieving a VHA national priority goal. Currently, the VHA goals as articulated by the Office of the Undersecretary for VHA include: including improving access, improving employee (provider) engagement, establishing a high-performing network, promoting best practices consistently across sites, and restoring trust and confidence in VHA. QUERI Programs are designed to promote achievement of these VHA priorities as well as in response to the Choice Act external evaluation recommendations by developing and deploying common, unified implementation strategies that provide a clearer path to quality improvement. That is, the goal of using implementation strategies is to decrease time from publication of a best practice to its use by clinical providers, thus reducing the persistent gap between research and practice.16

FIGURE 2.

QUERI program: general architecture. QUERI indicates Quality Enhancement Research Initiative; QI, Quality Improvement; VHA, Veterans Health Administration.

Fifteen QUERI Programs (Table 1) were awarded in 2015 and 2016 through a peer-review process involving both scientific and clinical operations experts. Each Program is funded for 5 years, after which it must submit a new, competitive proposal (which assumes, as with VHA priority goals, Program goals may need updating and reassessing). The Programs focus on achieving an impact goal congruent with a VHA national priority that is functionally supported by at least 2 separate VHA clinical or policy-based national program offices representing different business lines of functioning (eg, informatics, nursing, primary care, specialty care, pharmacy). Involvement of >1 national program office ensures that there is a coalition of VHA national leaders who have a stake in the realization of the priority goal and that the goal is relevant to various components of the VHA system. The impact goal of each QUERI Program is attained through the deployment of specific projects using a common implementation strategy or set of strategies. The clinical goal of these projects is to rapidly deploy best practices, especially across lower performing sites, to address recommendations from the Choice Act’s integrated evaluation. Each project, while focusing on a cross-cutting national priority goal, may retain essential areas of scientific expertise by focusing on specific health conditions. The Programs’ overall scientific goal is to serve as laboratories for implementation strategies, testing how best to design or tailor them, and how to make them efficient, effective, and replicable to improve quality across sites.

Rigorous Evaluations Informing Evidence-based Policy

For Strategic goal 2, QUERI supports use of rigorous methods through the deployment of national evaluations of VHA programs or policies. Several of these evaluations involved assessing the initial implementation of the Choice Act (Table 2), conducted in close collaboration with VHA’s Office of Analytics and Business Intelligence. These evaluations primarily focused on critically assessing methods for measuring patient care quality and experience, as well as the impact of the initial implementation of the Choice Act on care access and availability of non-VA providers for Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder, use of opioid therapy across VA and non-VA care settings, and coordination of care for women Veterans. Some of the evaluations used qualitative and quantitative analyses to assess implementation of the Choice Act under third-party administrators. Others sought to determine appropriate quality of care and satisfaction measures (as well as appropriate data sources) to better assess the impact of the Choice Act among Veterans. Key findings from these evaluations revealed initial challenges in obtaining data on non-VA care, as well as limited availability of specialty care providers, especially in rural areas.

These initial Choice Act evaluations also informed subsequent national QUERI evaluations to study the implementation of other VHA programs and policies including Community Care. Notably, Community Care is a key recommendation of the Commission on Care’s final report, which called for establishment of non-VA community provider networks to enhance access to care for Veterans (Choice Act Section 202). Specific evaluations recently launched by QUERI and cofunded by VHA clinical operations included assessment of VA and non-VA care access measures, provider availability and social determinants of health, evaluation of VHA’s Caregiver Support Program to determine cost of providing care to non-Veteran family members, and implementation of VHA clinic management training programs designed to improve coordination of VA and non-VA care (Table 2).

QUERI Partnered Evaluations are intended to rigorously assess the impact, spread, and sustainability of VHA national clinical programs or policies. All Partnered Evaluations are peer reviewed by a scientific review panel to ensure utilization of the most rigorous implementation and evaluation methods. The ultimate goals of these evaluations are to have more VHA clinical operations and policies driven by research evidence and to enable VHA clinical operations to more readily tap into the national network of evaluation and implementation experts. In 2016, VHA leaders increased their investment in funding QUERI Partnered Evaluation Initiatives in response to the US Office of Management and Budget’s recommendation that government agencies invest in evidence-based policy,17 particularly through the use of randomized program evaluation designs.18,19 As a result, the number of Partnered Evaluation Initiatives recently doubled in response to greater interest in evaluation.

Most recently, and in response to an urgent need to address another key recommendation from the Choice Act Section 202’s Commission on Care report to promote a high-performing practice network through the diffusion of best practices, QUERI launched a national evaluation of the VHA’s Diffusion of Excellence initiative. This initiative was a complementary program aimed at spreading best practices more consistently across VHA sites using a “bottom-up” approach. Over 250 promising practices were submitted by VHA frontline providers nationwide and were vetted by subject matter experts through social media and a national Diffusion Council. Top-rated practices were bid on by facility directors through a “Shark Tank” approach, in which they committed funding to replicate the practices at their site. The objective of the QUERI evaluation is to determine the impact of the diffusion of the best practices on achievement of the Undersecretary’s goals of improving access to care and quality, as well as determine how the initiative was implemented and lessons learned in terms of its further spread and sustainability.

Implementation Science Network

For Strategic goal 3, QUERI remains grounded in scientific rigor by promoting the growing field of implementation science, the study of methods to promote the uptake of effective practices in routine care. QUERI was one of the first entities to establish a national network of implementation scientists. This network has been expanded through the new Programs and national Partnered Evaluations to spread implementation science and training opportunities for investigators in VHA and beyond. QUERI’s continued leading role in implementation science is reflected in the required Implementation Cores of each Program (Table 1). Ultimately, to boost deployment of best practices in VHA and beyond, QUERI supports sustained investment in a critical mass of trained scientists and increased linkages with other health systems to promote an interdisciplinary perspective in quality improvement.

QUERI’s national network of implementation scientists is also poised to address a key recommendation from the Choice Act’s integrated evaluation (Section 201) as well as the Commission on Care’s recommendation to promote best practices more consistently on a national scale, specifically, by working with local providers and national leaders to help implement best practices (Section 202). Identification and deployment of scientifically supported implementation strategies represent important future directions of the implementation science field, and was also called out as a key component of a Learning Health Care system.20 Hence, QUERI can also inform further implementation of Community Care, recommended by the Commission on Care’s Section 201 and 202, by identifying which implementation strategies are most effective in coordinating care and improving quality, given variations in health care practice culture, climate, resources, and provider training, so that providers buy into these strategies and patients can take advantage of effective practices more rapidly.

RESULTS

As the VHA responds to the Choice Act, QUERI is poised to deploy more initiatives to support VHA’s ongoing transformation to a Learning Health Care System. A unique service QUERI provides is the deployment and evaluation of effective implementation strategies, to support VHA’s response to the Choice Act’s Section 201 recommendation toward a clearer path in deployment of best practices to reduce variation in quality of care. The use of implementation strategies has also been cited as a priority research topic based on a recent National Academy of Medicine Roundtable on Learning Health Care System research.20 Rigorous study of implementation strategies to promote use of existing best practices can potentially have greater policy and public health impacts than traditional efficacy research on identifying effective treatments or practices because of the emphasis on promoting access and improving quality, especially in lower resourced settings when the availability of effective treatments is uncertain.21

The QUERI programs, through their Implementation Cores, are currently evaluating a multidisciplinary set of strategies designed to further implement best practices in VHA. Many of these strategies arise from the public health and clinical disciplines, such as Audit and Feedback, and more recently, Replicating Effective Programs22 and Community Engagement,23 which involve substantial input from frontline providers and end-users in the adaptation of and training in best practices. Other strategies derived from the psychology and business literatures focus on optimizing provider team functioning through mentoring,24 leadership and strategic thinking,25 or learning collaboratives.26 These approaches complement ongoing efforts by many health care systems in adopting systems redesign or Lean approaches to improve overall quality of care.27

Ultimately, for these implementation strategies to be effective and sustainable in promoting uptake of best practices in a Learning Health Care System such as VHA, they will need to be further operationalized and evaluated among a wider group of frontline providers. They will also need to be deployed within the community provider networks to promote more consistent quality of care across non-VA providers. These strategies will need to integrate parallel growth in knowledge regarding information technology/“Big Data,” behavioral science, and health care regulatory policy. Specifically, QUERI and VHA will need to invest in more consistent capture of non-VA data to facilitate implementation and evaluation efforts across community provider networks. As with clinical treatments, implementation strategies will require tailoring to achieve their goals of improving the uptake of effective practices across underperforming sites. Notably, emerging implementation studies have incorporated adaptive or sequential multiple assessment randomized trial designs that can inform tailoring of implementation strategies across different organizational contexts.28

QUERI also supports VHA Learning Health Care System initiatives that generate new evidence for implementation through a national network of Evidence Synthesis Program (ESP) centers.29 These centers provide timely, accurate systematic reviews of targeted topics of clinical or policy importance to VHA leadership. The topics are nominated by VHA operations leaders and, after vetting for scope and feasibility, are then sent to one of 4 centers across the United States, who in turn develop a synthesis of the evidence based on the literature as well as recommendations for VHA policy and practice. Examples of recent ESP systematic reviews include wait times and access to care, pay-for-performance, pharmacogenomic testing for antidepressants, cannabis for the treatment of chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder, and electronic health record–based interventions to reduce inappropriate imaging. Published ESP reports have not only informed care within VHA facilities but can serve as a hub for promoting best practices in its emerging community provider networks.

Further, QUERI is increasingly investing in building capacity for routine data collection to inform rapid national program implementation and evaluation, a central component of the Learning Health Care System framework. Each of the Choice Act evaluations and several of the Partnered Evaluation Initiatives (Table 2) have responded to VHA’s need for more comprehensive and consistent clinical data on Veteran processes and outcomes of care to monitor care outside of VHA and implementation of best practices. Increasingly these evaluations will need to rely on non-VA services data from third-party providers or community provider networks. The initial QUERI-funded Choice Act evaluations experienced barriers to accessing third-party data sources, which then informed efforts to better capture these data through VHA’s Office of Community Care. Nonetheless, VHA will require more efforts to ensure that non-VA data are recorded accurately and consistently.

Given the growth in data capacity building and partnered evaluations, QUERI has worked with VHA leaders to streamline and communicate regulatory processes for quality improvement protocols. Partnered evaluations are facilitated through VHA’s clarification in policies around the definition of “research” and operationalization of a process for clinical operations to approve evaluations that are considered quality improvement.30 This guidance has led to the ability of QUERI investigators to respond more rapidly to VHA clinical operations’ needs to conduct rapid evaluations, even potentially involving randomization. To this end, QUERI deployed an Implementation and Quality Improvement toolkit to facilitate design of quality improvement and program evaluation studies consistent with the Common Rule.

Finally, QUERI recently funded an Evidence-based Policy Resource Center (PEPReC) to support rigorous evaluation of high-priority policy, planning, and management initiatives with strong potential to improve the quality and efficiency of VHA health care. PEPReC emphasizes the use of randomized program evaluations to assess the effectiveness of new VHA policies and practices and determine which implementation strategies are most effective in their deployment.31 Rigorous evaluation design through randomization can result in more effective practices and prevent wasted effort and expense on ineffective approaches, ultimately producing greater return on the resources invested.18 Current PEPReC-supported evaluations include a predictive model for suicide prevention, clinical dashboards to assess opioid safety, Veteran home and community-based services, and telehealth for dermatology. The path toward rigorous program evaluation will continue in the federal government for years to come, as tough decisions are made in regards to appropriations. The Evidence-based Policymaking Commission Act, signed into law in March 2016, proposes to enact a commission to support the development of more standardized data for rigorously evaluating policies and ultimately help VHA transformation as a Learning Health Care System.32

CONCLUSIONS

As VHA becomes more of a health care payer as well as provider through the Choice Act and Community Care, its reorganization will involve substantial changes that will have intended and unintended consequences on Veteran quality of care. In response, QUERI supports VHA’s transformation through the use of implementation strategies that promote deployment of best practices across different settings and through rapid and rigorous evaluations of new programs and policies.

In addition, QUERI’s updated strategic goals in implementation and evaluation science can inform ongoing implementation of the Choice Act and Community Care programs, and ultimately the evolution of a Learning Health Care System in VHA and elsewhere. Specifically, rigorous evaluations are especially needed regarding deployment of best practices across VA and non-VA services to inform implementation of community provider networks. Moreover, QUERI is poised to apply implementation science toward assessing the impact of Choice Act and Community Care implementation on patient and clinician decision-making and clinical team functioning/engagement across VA and non-VA providers. Rigorous studies on the organizational (eg, leadership), financial (eg, value-based purchasing), and provider (eg, workload) factors associated with implementation of care coordination best practices across VA and non-VA care settings will also be needed. Finally, further evaluation of the Choice Act’s impact on non-VA health care systems will be needed as more Veterans receive care outside the VA clinic walls, especially as VA and non-VA health care systems become more integrated.

Overall, through its national network of Programs, Partnered Evaluations, and implementation scientists, QUERI serves as an example of how to operationalize core components of a Learning Health Care System, particularly through funding, regulatory, and collaboration mechanisms by which scientists can actively participate in the deployment and evaluation of best practices in real-world health care settings to ultimately improve care for Veterans and beyond.

Footnotes

Supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research & Development Service.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of VA.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Giroir BP, Wilensky GR. Reforming the Veterans Health Administration—beyond palliation of symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1693–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kizer KW, Jha AK. Restoring trust in VA health care. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:295–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hogan MM, et al. Comparison of quality of care for patients in the Veterans Health Administration and patients in a national sample. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:938–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper AL, Jiang L, Yoon J, et al. Dual-system use and intermediate health outcomes among Veterans enrolled in Medicare Advantage Plans. Health Serv Res. 2015;50:1868–1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act of 2014 (“Choice Act” US Public Law 113–146). 2014. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/113/plaws/publ146/PLAW-113publ146.pdf. Accessed December 7, 2016.

- 6.US Department of Veterans Affairs. Healthcare Inspection Access to Urology Service Phoenix VA Health Care System, Phoenix, Arizona. Washington, DC: Office of Inspector General; 2015. Report No. 14-00875-03. Available at: http://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-14-00875-03.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.The MITRE Corporation. Independent Assessment of the Health Care Delivery Systems and Management Processes of the Department of Veterans Affairs Volume I: Integrated Report. McLean, VA: The MITRE Corporation; 2015. Available at: http://www.va.gov/opa/choiceact/documents/assessments/integrated_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Commission on Care. Commission on Care Final Report. Washington, DC: Commission on Care; 2016. Available at: https://commissiononcare.sites.usa.gov/files/2016/07/Commission-on-Care_Final-Report_063016_FOR-WEB.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demakis JG, McQueen L, Kizer KW, et al. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI): a collaboration between research and clinical practice. Med Care. 2000;38(suppl 1):I17–I25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stetler CB, McQueen L, Demakis J, et al. An organizational framework and strategic implementation for system-level change to enhance research-based practice: QUERI Series. Implement Sci. 2008;3:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Best care at lower cost: the path to continuously learning health care in America. Recommendations. 2012. Available at: http://iom.nationalacademies.org/∼/media/Files/Report%20Files/2012/Best-Care/Best%20Care%20at%20Lower%20Cost_Recs.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2015.

- 13.Feussner JR, Kizer KW, Demakis JG. The Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI): from evidence to action. Med Care. 2000;38(suppl 1):I1–I6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubenstein LV, Mittman BS, Yano EM, et al. From understanding health care provider behavior to improving health care: the QUERI framework for quality improvement. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative. Med Care. 2000;38(suppl 1):I129–I141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Annual report. 2014. Available at: https://iom.nationalacademies.org/∼/media/Files/About%20the%20IOM/2014/IOMAnnualReport.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2015.

- 16.Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational research. J R Soc Med. 2011;104:510–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bridgeland J, Orszag P. Can government play moneyball? How a new era of fiscal scarcity could make Washington work better. 2013. Available at: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2013/07/can-government-play-moneyball/309389/. Accessed November 17, 2015.

- 18.Finkelstein A, Taubman S. Health care policy. Randomize evaluations to improve health care delivery. Science. 2015;347:720–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen H, Baicker K, Taubman S, et al. The Oregon health insurance experiment: when limited policy resources provide research opportunities. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2013;38:1183–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chambers DA, Feero WG, Khoury MJ. Convergence of Implementation Science, Precision Medicine, and the Learning Health Care System: a new model for biomedical research. JAMA. 2016;315:1941–1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woolf SH. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA. 2008;299:211–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kilbourne AM, Neumann MS, Pincus HA, et al. Implementing evidence-based interventions in health care: application of the replicating effective programs framework. Implement Sci. 2007;2:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wells KB, Jones L, Chung B, et al. Community-partnered cluster-randomized comparative effectiveness trial of community engagement and planning or resources for services to address depression disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1268–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirchner JE, Ritchie MJ, Pitcock JA, et al. Outcomes of a partnered facilitation strategy to implement primary care-mental health. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(suppl 4):904–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Farahnak LR, et al. Leadership and organizational change for implementation (LOCI): a randomized mixed method pilot study of a leadership and organization development intervention for evidence-based practice implementation. Implement Sci. 2015;10:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nadeem E, Olin SS, Hill LC, et al. Understanding the components of quality improvement collaboratives: a systematic literature review. Milbank Q. 2013;91:354–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicolay CR, Purkayastha S, Greenhalgh A, et al. Systematic review of the application of quality improvement methodologies from the manufacturing industry to surgical healthcare. Br J Surg. 2012;99:324–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kilbourne AM, Almirall D, Eisenberg D, et al. Adaptive Implementation of Effective Programs Trial (ADEPT): cluster randomized SMART trial comparing a standard versus enhanced implementation strategy to improve outcomes of a mood disorders program. Implement Sci. 2014;9:132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development. Evidence-based Synthesis Program website. 2015. Available at: http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/. Accessed November 15, 2015.

- 30.US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research Oversight. VHA handbook 1058.05 transmittal sheet: VHA operations activities that may constitute research. 2011. Available at: http://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=2456. Accessed November 15, 2015.

- 31.Shulkin DJ. Beyond the VA crisis—becoming a high-performance network. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1003–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.US House of Representatives. Evidence-based Policymaking Commission Act, Public Law No: 114-140. 2016. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/1831. Accessed December 7, 2016.