Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to assess the characteristics of neuropathic pain after non-traumatic, non-compressive (NTNC) myelopathy and find potential predictors for neuropathic pain.

Design

We analyzed 54 patients with NTNC myelopathy. The Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ) and the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS) were used to assess pain. Health-related QOL was evaluated by the Short Form 36-item (SF-36) health survey.

Results

Out of 48 patients with pain, 16 (33.3%) patients experienced neuropathic pain. Mean age was significantly lower in patients with neuropathic pain than in patients with non-neuropathic pain (39.1 ± 12.5 vs. 49.8 ± 9.3, P = 0.002). There were no statistically significant differences in the other variables including sex, etiology of myelopathy, pain and QOL scores between the two groups. A binary logistic regression revealed that onset age under 40, and non-idiopathic etiology were independent predictors of the occurrence of neuropathic pain. Both SF-MPQ and LANSS scores were significantly correlated with SF-36 scores, adjusted by age, sex, presence of diabetes mellitus, and current EDSS scores (r = –0.624, P < 0.0001 for SF-MPQ; r = –0.357, P = 0.017 for LANSS).

Conclusion

Neuropathic pain must be one of serious complications in patients with NTNC myelopathy and also affects their quality of life. Onset age and etiology of myelopathy are important factors in the development of neuropathic pain in NTNC myelopathy.

Keywords: Spinal cord, Myelopathy, Chronic pain, Neuropathic pain, Quality of life

Introduction

Chronic pain is a frequent problem for patients with myelopathy. Any level of pain following myelopathy interferes with rehabilitation and has a negative effect on quality of life.1 On average, 65% of individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) and 49% with non-traumatic SCI suffer from pain.2,3 The International Spinal Cord Injury Pain classification divides SCI pain into nociceptive, neuropathic, and other pain.4 According to previous studies, nociceptive pain is the most common type associated with myelopathy.5

However, approximately 30 to 40% of the pain manifests as neuropathic pain.6–8 Neuropathic pain in myelopathy is related to the damage of the nerve root and spinal cord; it tends to be chronic and responds poorly to treatment, resulting in various complications such as joint contractures, muscle atrophy, pressure sores, and cardiovascular problems.9 Therefore, it is important to diagnose neuropathic pain accurately and rapidly. Old age at the time of injury, early onset of neuropathic pain following myelopathy, and an initial intense and continuous pain appear to be predictive factors for the development and chronicity of neuropathic pain.1,10–13

But little is known about the characteristics or predictive factors of neuropathic pain in non-traumatic, non-compressive (NTNC) myelopathy. Most previous studies of myelopathy pain were limited to traumatic and compressive causes despite numerous patients with NTNC myelopathy, such as acute transverse myelitis, neuromyelitis optica (NMO), multiple sclerosis (MS) or infective myelopathy who experience pain for a long period after disease onset.2,14

The first objective of this study was to evaluate the prevalence and characteristics of neuropathic pain in patients with NTNC myelopathy. The second aim was to determine potential predictors for neuropathic pain in these patients.

Methods

All patients with NTNC myelopathy who visited the department of neurology of a university hospital between March 2014 and September 2014 were included. We interviewed a total 58 patients who were diagnosed with NTNC myelopathy at least 3 months after onset. Three months was chosen as a standard point of division between acute and chronic pain.15 All patients had an abnormal intra-cord signal demonstrated by spinal MRI. Patients with dementia and those who experienced pain from other diseases were excluded. Patients were examined and interviewed by an experienced neurologist at their regular visit to the outpatient clinic. All patients completed questionnaires for pain and quality of life. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital and all patients provided informed consent prior to participation.

The etiology of myelopathy was classified as idiopathic, demyelinating diseases (NMO, MS), infection, or other causes via medial record review. The diagnosis of NMO was made based on the 2006 Wingerchuk criteria,16 while MS was diagnosed according to the 2010 McDonald criteria.17 The level of myelopathy was categorized as cervical, thoracic, lumbar, or multi-level lesion. Results from cerebrospinal fluid and electrophysiological tests, in addition to a number of laboratory tests for differentiating cause of myelopathy were also reviewed.

Patients were interviewed about the location, patterns, and characteristics of their pain. The length of time between onset of disease to pain occurrence, and the total pain duration were also recorded. When neuropathic pain was present, it was classified as either above-level, at-level, or below-level neuropathic pain.7 The Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), which is used to measure the different qualities of the subjective pain experience. It contains 11 sensory words and four affective words to describe pain.18 Patients indicated which of the 15 words described their pain and rated the intensity of the pain as 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (severe). A total score was calculated by summing the sensory and affective scores. The Korean version of the SF-MPQ has been previously validated in a chronic pain population.19 Neuropathic pain was diagnosed if patients scored 12 or more on the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS).20 The LANSS scale, first invented by Bennett, is a useful tool that helps clinicians distinguishing neuropathic pain from nociceptive pain.20 The LANSS consists of 7 items: dysesthesia, autonomic, evoked, paroxysmal, thermal, allodynia, and tender/numb. Each item was assigned a score from 1 to 5, and the total score could range from 0 to 24. The Korean version of the LANSS was validated by Cho et al.21 Patient functional status was assessed using the Short Form-36 (SF-36).22 This general health status measure contains eight domains: physical functioning, physical role limitation, mental health, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, and emotional role limitation. The eight domain scales can be combined to obtain two summary scores, physical and mental component summary, related to physical function and mental health respectively. The scores range from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating a higher level of function and/or better health. The reliability of the Korean version has been previously validated.23

In the characteristic of patients with pain, continuous data are expressed as the mean and range, and non-continuous data are expressed as the median. The pain descriptors in the neuropathic and non-neuropathic pain groups were compared using a Mann-Whitney U test. A χ2-test and Fisher's exact test were used for categorical variables to compare pain characteristics of the non-neuropathic and neuropathic pain groups. For continuous variables with normal distribution and non-normal distribution, the t-test and Mann-Whitney U test were used, respectively. Binary logistic regression analyses were performed to adjust for various factors such as age, sex, and laboratory result. The relationship between variables was examined by Spearman's correlation coefficient. All statistical analysis was performed by the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 11.0 software. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 58 patients interviewed, four patients were excluded due to dementia (n = 2) and refusal to give study consent (n = 2). In total, 48 patients reported pain whilst 6 patients did not have pain. We analyze data of 48 patients who reported pain after NTNC myelopathy.

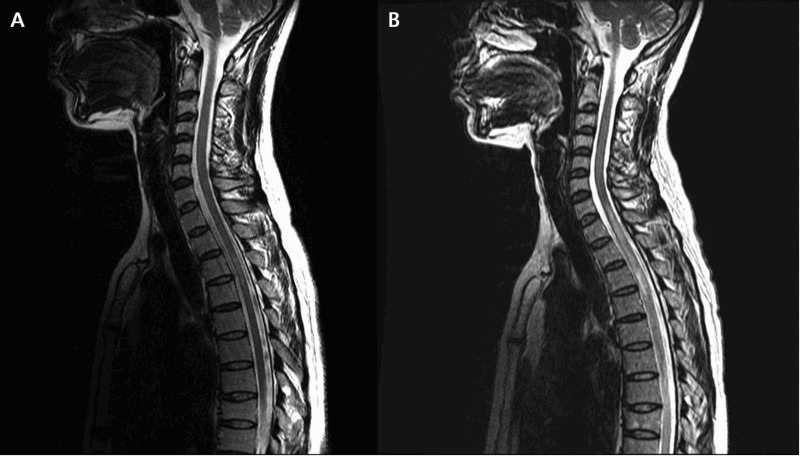

Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients with pain are summarized in Table 1. The mean patient age was 46.2 ± 11.5 years (± standard deviation [SD]); 27 patients (56.3%) were men. Eighteen (37.5%) patients had recurrent myelopathy (Fig. 1) and six (12.5%) patients had diabetes mellitus (DM). Median (range) initial and current Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores were 3.0 (0–9) and 2.2 (0–7.5), respectively. The majority of cases had idiopathic etiology (n = 36, 75%), and the most common level of lesion was in the thoracic cord (n = 23, 47.9%).

Table 1.

Characteristic of patients with pain

| Pain (+) (n = 48) | |

|---|---|

| Mean age ± SD | 46.2 ± 11.5 |

| Male, n (%) | 27 (56.3) |

| DM, n (%) | 6 (12.5) |

| Recurrent myelopathy, n (%) | 18 (37.5) |

| Median EDSS (range) | |

| Initial | 3.0 (0–9) |

| Current | 2.2 (0–7.5) |

| Etiology of myelopathy | |

| Idiopathic | 36 (75) |

| NMO, n (%) | 6 (12.5) |

| MS, n (%) | 2 (4.2) |

| Infection, n (%) | 3 (6.3) |

| Others, n (%) | 1 (2.1) |

| Lesion level | |

| Cervical, n (%) | 21 (43.8) |

| Thoracic, n (%) | 23 (47.9) |

| Lumbosacral, n (%) | 0 (0) |

| Multi-level, n (%) | 4 (8.3) |

| Onset of pain after myelopathy | |

| < 3 months, n (%) | 41 (85.4) |

| 3–6 months | 6 (12.5) |

| ≥ 6 months | 1 (2.1) |

| Median pain duration, month (range) | 52 (35–162) |

| Pattern of pain | |

| Continuous, n (%) | 35 (72.9) |

| Intermittent, n (%) | 13 (27.1) |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; DM, Diabetes mellitus; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; NMO, Neuromyelitis optica; MS, Multiple sclerosis

Figure 1.

Recurrent transverse myelitis. (A) Sagittal T2 weighted image shows increased signal at T3–4 level. (B) Sagittal T2 weighted image after 2 years show recurrence of myelitis with extended lesion at C7-T10 level in the same patient.

In total, 41 (85.4%) patients stated that pain initiated during the first 3 months of myelopathy onset. Median (range) pain duration was 52 (3.5–162) months and the median (range) SF-MPQ score was 12 (1–34). Thirty five (72.9%) patients reported continuous pain throughout the day (Table 1). The most common descriptors used by patients were exhausting, gnawing, and heavy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pain descriptors used in patients with myelopathy

| Overall patients (n = 48, multiple choice) | Patient with neuropathic pain (n = 16, multiple choice) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throbbing | 29 | 10 | 0.783 |

| Shooting | 22 | 10 | 0.034 |

| Stabbing | 19 | 11 | <0.001 |

| Sharp | 18 | 11 | 0.332 |

| Cramping | 16 | 8 | 0.332 |

| Gnawing | 37 | 15 | 0.204 |

| Hot-burning | 10 | 9 | 0.066 |

| Aching | 24 | 11 | 0.046 |

| Heavy | 34 | 11 | 0.231 |

| Tender | 24 | 9 | 0.055 |

| Splitting | 8 | 8 | 0.164 |

| Exhausting | 39 | 14 | 0.091 |

| Sickening | 7 | 7 | 0.183 |

| Fearful | 23 | 6 | 0.805 |

| Punishing | 10 | 6 | 0.273 |

Out of 48 patients with pain, 16 (33.3%) patients reported neuropathic pain. Otherwise, 32 (66.6%) experienced non-neuropathic pain, which included nociceptive or mixed pain. In pair-wise comparisons between non-neuropathic and neuropathic pain groups, mean (±SD) age was statistically significantly lower in patients with neuropathic pain than in patients with non-neuropathic pain (39.1 ± 12.5 vs. 49.8 ± 9.3, P = 0.002). However, overall median pain score (assessed by SF-MPQ) was significantly higher in patients with neuropathic pain (8 vs. 17.5, P = 0.004). There were no statistically significant differences in the other variables including sex, DM, etiology of myelopathy, CSF study, pain duration, total SF-36 score, and HADS score between the two pain groups (Table 3). Exhausting and gnawing were also the most common pain descriptors in patients with neuropathic pain. However, shooting, stabbing, and aching descriptors were significantly highly used in patients with neuropathic pain (Table 2).

Table 3.

Pain characteristics in myelopathy

| Non-neuropathic pain (LANSS < 12, n = 32) | Neuropathic pain (LANSS ≥ 12, n = 16) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 49.8 ± 9.3 | 39.1 ± 12.5 | 0.002 |

| Male, n (%) | 20 (62.5) | 7 (43.8) | 0.177 |

| DM, n (%) | 6 (18.8) | 0 (0) | 0.064 |

| Etiology | |||

| Idiopathic, n (%) | 25 (78.1) | 11 (68.8) | 0.408 |

| NMO, n (%) | 4 (12.5) | 2 (12.5) | |

| MS, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Infection, n (%) | 3 (9.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Others, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.3) | |

| Initial EDSS, median (range) | 3 (0–9) | 2.8 (1–8) | 0.741 |

| Current EDSS, median (range) | 2.3 (0–7.5) | 2.3 (0–7.5) | 0.848 |

| Length of lesion, median (range) | 3.5 (1–24) | 3.5 (1–17) | 0.680 |

| Onset to pain, median (range) | 0 (0–5) | 0 (0–9) | 0.905 |

| Median pain duration (range) | 54 (3.5–160) | 31 (5–166) | 0.485 |

| Median SF-MPQ (range) | 8 (2–34) | 17.5 (1–26) | 0.004 |

| Median SF-36 (range) | 73.2 (49.4–104.3) | 70.5 (50.3–102.1) | 0.101 |

| Median HADS (range) | 15 (1–29) | 18.5 (2–29) | 0.306 |

LANSS, Leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs; SD, standard deviation; DM, Diabetes mellitus; NMO, Neuromyelitis optica; MS, Multiple sclerosis; CSF, Cerebrospinal fluid; SF-MPQ, short form McGill pain questionnaire; SF-36, short form 36; HADS, Hospital anxiety depression scales

A binary logistic regression was performed to evaluate the predictive factors for the development of neuropathic pain in NTNC myelopathy. The following factors were entered into the model: (1) age of myelopathy onset > 40 year old, (2) sex, (3) etiology; idiopathic or non-idiopathic, (4) initial EDSS score. The results showed that onset age under 40 and non-idiopathic etiology were independent predictors of the occurrence of neuropathic pain (Table 4). The Nagelkerke R2 value was 0.383, suggesting a strong association between neuropathic pain and the independent variables in the regression analysis.

Table 4.

Predictive factors for occurrence of neuropathic pain

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | 2.899 (0.549–15.315) | 0.210 |

| Age < 40 | 16.596 (3.044–90.477) | 0.001 |

| Non-idiopathic etiology | 2.126 (1.373–12.116) | 0.049 |

| Initial EDSS | 0.909 (0.657–1.258) | 0.565 |

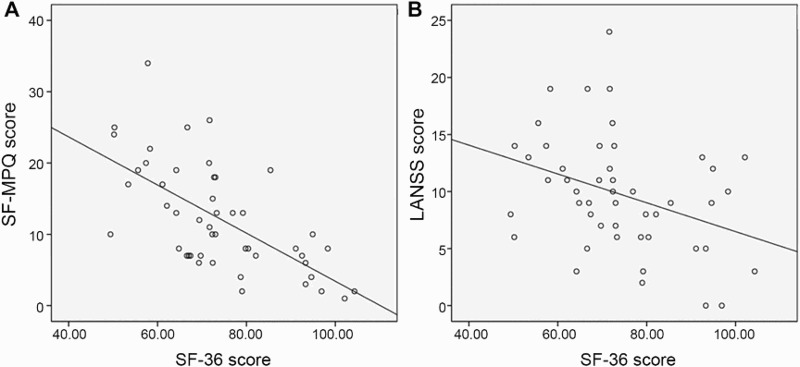

Both the SF-MPQ and LANSS scores showed significant correlation with SF-36 scores adjusted by age, sex, presence of DM, and current EDSS scores (r = –0.624, P < 0.0001 for SF-MPQ; r = –0.357, P = 0.017 for LANSS). However, SF-MPQ scores, which indicated total pain, showed a higher correlation with SF-36 scores than the LANSS scores (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Relationship between quality of life and total pain score (A) and neuropathic pain score (B) after adjusted by age, sex, DM, current EDSS score (r = –0.624, P < 0.0001 for SF-MPQ; r = –0.357, P = 0.017 for LANSS).

Discussion

Non-traumatic non-compressive (NTNC) myelopathy accounts for 30–50% of spinal cord disorders.22,24 Chronic pain is a frequent complication in patients with NTNC myelopathy.2,25 In earlier reports, the frequency of chronic pain after non-traumatic SCI was 49.3–66.7%.2,14 Long-standing neuropathic pain is considered one of the most challenging problems associated NTNC myelopathy, but few studies reported on the frequency of neuropathic pain in NTNC myelopathy.26 Werhagen reported that 38% of patients with non-traumatic SCI suffer from neuropathic pain.26 In the present study, 88.9% of patients reported chronic pain and one third of cases had neuropathic features. The percentage of overall pain was higher in our study than previous report.26 We speculated that this result had several causes. First, we evaluated only chronic pain. After the acute stage of myelopathy, nociceptive pain due to weakness, overuse, and spasticity increases naturally. Second, because pain is a subjective symptom, it is difficult to objectify the existence of pain or measure its severity. That might be the main reason why the studies to date reported different frequencies of pain after non-traumatic SCI. In our study, the proportion of patients with neuropathic pain was similar to that of a previous report.26 In NTNC myelopathy, unlike traumatic SCI, there is no injury to or compression of the structures surrounding the spinal cord. Therefore, neuropathic pain could be more common than nociceptive pain in NTNC myelopathy. However, the present study revealed that 32 (67%) patients had non-neuropathic pain. The plausible reason for this result is that patients with NTNC myelopathy are older than those with traumatic SCI.27,28 Even if we excluded patients who experienced pain from other diseases, the elderly would have more pain-causing problems such as arthritis or muscle cramps. These factors could affect the majority of our patients, who had NTNC myelopathy with non-neuropathic pain.

In our study, patients with neuropathic pain showed no difference in sex, myelopathy etiology, pain duration, or the existence of diabetes compared to patients with non-neuropathic pain. However, mean age was significantly lower in these patients. In the one existing study of neuropathic pain in NTNC myelopathy, women reported neuropathic pain below the level of the lesion more often (40%) than did men (13%). The prevalence was particularly high (64%) for patients with malignant spinal cord diseases. Age at spinal cord symptom onset, complete/incomplete injury, and injury level had no significant influence on the prevalence.26

While many studies have shown that neuropathic pain is a common and serious problem after myelopathy, the understanding of the factors associated with its development is limited. In the present study, several variables were significantly related to the development of neuropathic pain after the onset of myelopathy. First, the age of patients in the neuropathic pain group was significantly lower than that of the non-neuropathic group. This is contrary to other studies in which older age has been found as a predictor for persistent neuropathic pain.26,29–31 Numerous studies have shown that increasing age is a predictive factor for chronic pain following surgery,32 illness,33 or injury.34 This may be due to age related changes in endogenous pain control mechanisms at the central level.35–38 In contrast, age and neuropathic pain following SCI have not been found to be related.10,39,40 Indeed, one study found that myelopathy-related neuropathic pain was mainly observed in patients aged between 30 and 39 years, but there was no correlation with age and pain severity.41 A more substantial understanding of the mechanisms of neuropathic pain in myelopathy is still elusive. Unlike other disease, myelopathy leads to direct damage to the anatomical substrates related to pain control. Thus, neuropathic pain can occur through several different potential mechanisms. For example, active recovery after spinal cord damage in young patients can enhance neuroplasticity and thus can induce severe neuropathic pain.42–44

With regard to age, binary logistic regression analysis confirmed findings of the paired comparison analysis, showing that onset age below 40 is an independent predictive factor for the development of neuropathic pain. A recent study found a marked difference in the effectiveness of diffuse noxious inhibitory control (DNIC) between a group of healthy participants aged between 40 to 55 years old and a group of patients aged between 20 and 35 years.45 DNIC, which is also referred to as the bulbospinal endogenous pain control mechanism, is one of the most understood descending inhibitory pain mechanisms. It has been suggested that pain perception and endogenous pain modulation function decline by middle age and continue to deteriorate thereafter.45 The present findings support this suggestion because there was a significantly higher occurrence of neuropathic pain in patients under the age of 40.

Besides age, non-idiopathic etiology was another significant predictor for neuropathic pain. A previous study reported that patients with a malignant etiology of myelopathy experienced neuropathic pain more frequently than other etiologic subgroups.46 Most studies, however, failed to find a relationship between the etiology of myelopathy and neuropathic pain.13,47 In the present study, known etiology such as MS, NMO, or infection was associated with a higher frequency of neuropathic pain. Unfortunately, the reason for these results is presently unknown. We speculate that the expanded lesion size and high recurrence rate of myelopathy with non-idiopathic etiology could have influenced our results.

Myelopathy pain is intense and constant, aggravated by various stimuli encountered during daily activities, and interferes with quality of life beyond just limiting motor functions. In one study, 70% of patients with myelopathy reported that pain affected their life to a great extent41 and in another report, more than 90% of such patients stated that their pain interfered with daily activities.48 Furthermore, numerous other studies have found that the health related quality of life of patients with neuropathic pain is worse than in those with non-neuropathic pain.49,50 In this study, both SF-MPQ and LANSS scores showed a significant correlation with SF-36 scores after adjustment for age, sex, presence of DM, and current EDSS score. In contrast to previous studies, SF-MPQ scores exhibited a higher correlation to SF-36 than LANSS scores. This may be because nociceptive pain is the most common type of pain during myelopathy, and secondly, a relatively low number of patients were included in this study.

Pain is a significant problem in patients with NTNC myelopathy and requires various therapies like pharmacotherapy, physical modalities, nerve blocks and behavioral interventions. There have numerous studies about the treatment of pain in SCI, and many drugs such as opioid, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antidepressants, or antiepileptics have been found to be effective in alleviating pain. Our patients are also taking such medications to control their pain. But many of them continued to experience mild to moderate pain despite taking the prescribed medications.

A major limitation of this study is that we included patients who visited our outpatients clinic regularly. Therefore, the case series could be confounded by a selection bias. Secondly, although we used the clinically accepted division point for the definition of chronic pain, a longer period of investigation on pain outcomes may be warranted to determine if manifestations of pain change over time. Thirdly, specific pain score tools for evaluating neuropathic pain in myelopathy have not been developed yet. The LANSS pain scale, however, is usually used for assess the neuropathic pain by various causes. Lastly, psychosocial variables pertinent to the development and maintenance of chronic pain were not fully examined. Various psycho-social differences such as catastrophizing, depression, or fear-related cognition may account for chronic pain.51,52 Further studies about the relationship between these issues and chronic pain may be needed.

In our study, the characteristics of chronic pain, especially neuropathic pain, in NTNC myelopathy were assessed and the predictive factors for development of neuropathic pain were investigated. Almost patients with NTNC myelopathy reported chronic pain and younger age of myelopathy onset was related to the development of neuropathic pain. A significant relationship was also found between pain and quality of life. These findings enhance the understanding of pain in NTNC myelopathy and may contribute to the advancement of research in this field as well as development of proper treatment.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors All co-authors contributed to study design and conduct of this research, and to analyze the data. EOI and JIS also contributed in writing and editing the manuscript.

Funding None.

Conflicts of interest None.

Ethics approval None.

References

- 1.Anke AG, Stenehjem AE, Stanghelle JK.. Pain and life quality within 2 years of spinal cord injury. Paraplegia 1995;33(10):555–9. doi: 10.1038/sc.1995.120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nair KP, Taly AB, Maheshwarappa BM, Kumar J, Murali T, Rao S.. Nontraumatic spinal cord lesions: a prospective study of medical complications during in-patient rehabilitation. Spinal Cord 2005;43(9):558–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siddall PJ, Loeser JD.. Pain following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2001;39(2):63–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryce TN, Biering-Sorensen F, Finnerup NB, Cardenas DD, Defrin R, Ivan E, et al. International Spinal Cord Injury Pain (ISCIP) Classification: part 2. Initial validation using vignettes. Spinal Cord 2012;50(6):404–12. doi: 10.1038/sc.2012.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siddall PJ, Taylor DA, McClelland JM, Rutkowski SB, Cousins MJ.. Pain report and the relationship of pain to physical factors in the first 6 months following spinal cord injury. Pain 1999;81(1–2):187–97. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00023-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonica JJ. Introduction: semantic, epidemiologic, and educational issues. In: Casey KL. Pain and Central Nervous System Disease: the central pain syndromes. New York: Raven Press, 1991; p. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siddall PJ, Taylor DA, Cousins MJ.. Classification of pain following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 1997;35(2):69–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finnerup N, Johannesen I, Sindrup S, Bach FW, Jensen TS.. Pain and dysesthesia in patients with spinal cord injury: a postal survey. Spinal Cord 2001;39(5):256–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu WT, Huang YH, Chen DC, Huang YH, Chou LW.. Effective management of intractable neuropathic pain using an intrathecal morphine pump in a patient with acute transverse myelitis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2013;9:1023–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norrbrink Budh C, Lund I, Ertzgaard P, Holtz A, Hultling C, Levi R, et al. Pain in a Swedish spinal cord injury population. Clin Rehabil 2003;17(6):685–90. doi: 10.1191/0269215503cr664oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Budh CN, Osteraker AL.. Life satisfaction in individuals with a spinal cord injury and pain. Clin Rehabil 2007;21(1):89–96. doi: 10.1177/0269215506070313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kennedy P, Frankel H, Gardner B, Nuseibeh I.. Factors associated with acute and chronic pain following traumatic spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord 1997;35(12):814–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siddall PJ, McClelland JM, Rutkowski SB, Cousins MJ.. A longitudinal study of the prevalence and characteristics of pain in the first 5 years following spinal cord injury. Pain 2003;103(3):249–57. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00452-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rouleau P, Guertin PA.. Traumatic and nontraumatic spinal-cord-injured patients in Quebec, Canada. Part 3: pharmacological characteristics. Spinal Cord 2011;49(2):186–95. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, et al. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain 2015;156(6):1003–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Weinshenker BG.. Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2006;66(10):1485–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000216139.44259.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawkes CH, Giovannoni G.. The McDonald Criteria for Multiple Sclerosis: time for clarification. Mult Scler 2010;16(5):566–75. doi: 10.1177/1352458510362441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melzack R. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain 1987;30(2):191–7. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)91074-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi SA, Son C, Lee JH, Cho S.. Confirmatory factor analsis of the Korean version of the short-form McGill pain questionnaire with chronic pain patients: a comparison of alternative models. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015;13:15. doi: 10.1186/s12955-014-0195-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett M. The LANSS Pain Scale: the leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs. Pain 2001;92(1–2):147–57. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00482-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho SI, Lee CH, Park GH, Park CW, Kin HO.. Use of S-LANSS, a tool for screening neuropathic pain, for predicting postherpetic neuralgia in patients after acute herpes zoster events: a single-center, 12-month, prospective cohort study. J Pain 2014;15(2):149–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKinley WO, Seel RT, Hardman JT.. Nontraumatic spinal cord injury: incidence, epidemiology, and functional outcome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999;80(6):619–23. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(99)90162-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han CW, Lee EJ, Iwaya T, Kataoka H, Kohzuki M.. Development of the Korean version of Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey: health related QOL of healthy elderly people and elderly patients in Korea. Tohoku J Exp Med 2004;203(3):189–94. doi: 10.1620/tjem.203.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Putten JJ, Stevenson VL, Playford ED, Thompson AJ.. Factors affecting functional outcome in patients with nontraumatic spinal cord lesions after inpatient rehabilitation. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2001;15(2):99–104. doi: 10.1177/154596830101500203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta A, Taly AB, Srivastava A, Murali T.. Non-traumatic spinal cord lesions: epidemiology, complications, neurological and functional outcome of rehabilitation. Spinal Cord 2009;47(4):307–11. doi: 10.1038/sc.2008.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Werhagen L, Hultling C, Molander C.. The prevalence of neuropathic pain after non-traumatic spinal cord lesion. Spinal Cord 2007;45(9):609–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.New PW, Rawicki HB, Bailey MJ.. Nontraumatic spinal Cord injury: demographic characteristics and complications. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002;83(7):996–1001. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.33100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burney RE, Maio RF, Maynard F, Karunas R.. Incidence, characteristics, and outcome of spinal cord injury at trauma centers in North America. Arch Surg 1993;128(5):596–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420170132021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ.. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet 2006;367(9522):1618–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68700-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Margot-Duclot A, Tournebise H, Ventura M, Fattal C.. What are the risk factors of occurence and chronicity of neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury patients? Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2009;52(2):111–23. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2008.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jung BF, Johnson RW, Griffin DR, Dworkin RH.. Risk factors for postherpetic neuralgia in patients with herpes zoster. Neurology 2004;62(9):1545–51. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000123261.00004.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White CL, LeFort SM, Amsel R, Jeans ME.. Predictors of the development of chronic pain. Res Nurs Health 1997;20(4):309–18. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dworkin RH. Which indiviuals with acute pain are most likely to developed a chronic pain syndrome? Pain Forum 1997;6(2):127–36. doi: 10.1016/S1082-3174(97)70009-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baldwin M, Johnson W, Butler R.. The error of using returns-to-work to measure the outcomes of health care. Am J Ind Med 1996;29(6):632–41. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edwards RR, Fillingim RB, Ness TJ.. Age-related differences in endogenous pain modulation: a comparison of diffuse noxious inhibitory controls in healthy older and younger adults. Pain 2003;101(1–2):155–65. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00324-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gibson SJ, Helme RD.. Age-related differences in pain perception and report. Clin Geriatr Med 2001;17(3):433–56. doi: 10.1016/S0749-0690(05)70079-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karp JF, Shega JW, Morone NE, Weiner DK.. Advances in understanding the mechanisms and management of persistent pain in older adults. Br J Anaesth 2008;101(1):111–20. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Washington LL, Gibson SJ, Helme RD.. Age-related differences in the endogenous analgesic response to repeated cold water immersion in human volunteers. Pain 2000;89(1):89–96. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00352-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakipoglu-Yuzer GF, Atci N, Ozgirgin N.. Neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury. Pain Physician 2013;16(3):259–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ravenscroft A, Ahmed YS, Burnside IG.. Chronic pain after SCI. A patient survey. Spinal Cord 2000;38(10):611–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Werhagen L, Budh CN, Hultling C, Molander C.. Neuropathic pain after traumatic spinal cord injury--relations to gender, spinal level, completeness, and age at the time of injury. Spinal Cord 2004;42(12):665–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karl A, Birbaumer N, Lutzenberger W, Cohen LG, Flor H.. Reorganization of motor and somatosensory cortex in upper extremity amputees with phantom limb pain. J Neurosci 2001;21(10):3609–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li S, Overman JJ, Katsman D, Kozlov SV, Donnelly CJ, Twiss JL, et al. An age-related sprouting transcriptome provides molecular control of axonal sprouting after stroke. Nat Neurosci 2010;13(2):1496–504. doi: 10.1038/nn.2674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahncke HW, Bronstone A, Merzenich MM.. Brain plasticity and functional losses in the aged: scientific bases for a novel intervention. Prog Brain Res 2006;157:81–109. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)57006-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lariviere M, Goffaux P, Marchand S, Julien N.. Changes in pain perception and descending inhibitory controls start at middle age in healthy adults. Clin J Pain 2007;23(6):506–10. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31806a23e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yap EC, Tow A, Menon EB, Chan KF, Kong KH.. Pain during in-patient rehabilitation after traumatic spinal cord injury. Int J Rehabil Res 2003;26(2):137–40. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200306000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ullrich PM, Jensen MP, Loeser JD, Cardenas DD.. Pain intensity, pain interference and characteristics of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2008;46(6):451–5. doi: 10.1038/sc.2008.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Finnerup NB, Johannesen IL, Sindrup SH, Bach FW, Jensen TS.. Pain and dysesthesia in patients with spinal cord injury: a postal survey. Spinal Cord 2001;39(5):256–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith BH, Torrance N.. Epidemiology of neuropathic pain and its impact on quality of life. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2012;16(3):191–8. doi: 10.1007/s11916-012-0256-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith BH, Torrance N, Bennett MI, Lee AJ.. Health and quality of life associated with chronic pain of predominantly neuropathic origin in the community. Clin J Pain 2007;23(2):143–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210956.31997.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Katz J, Selter Z.. Transition from acute to chronic postsurgical pain: risk factors and protective factors. Expert Rev Neurother 2009;9(5):723–44. doi: 10.1586/ern.09.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Molton IR, Stoelb BL, Jensen MP, Ehde DM, Raichle KA, Cardenas DD.. Psychological factors and adjustment to chronic pain in spinal cord injury: replication and cross-validation. J Rehabil Res Dev 2009;46(1):31–42. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2008.03.0044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]