Abstract

Objective

Describe the utilization, accessibility, and satisfaction of primary and preventative health-care services of community-dwelling individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI).

Design

Cross sectional, in-person or telephonic survey, utilizing a convenience sample.

Setting

Community.

Participants

Individuals with SCI greater than 12-months post injury.

Interventions

N/A.

Outcome measures

Demographic, injury related, and 34-item questionnaire of healthcare utilization, accessibility, and satisfaction with services.

Results

The final sample consisted of 142 participants (50 female, 92 male). Ninety-nine percent of respondents had a healthcare visit in the past 12-months with primary care physicians (79%), with SCI physiatrists (77%) and urologists (50%) being the most utilized. 43% of the sample reported an ER visit within the past 12-months, with 21% reporting multiple visits. People who visited the ER had completed significantly less secondary education (P = 0.0386) and had a lower estimate of socioeconomic status (P = 0.017). The majority of individuals (66%) were satisfied with their primary care physician and 100% were satisfied with their SCI physiatrist. Individuals who did not visit an SCI physiatrist were significantly more likely to live in a rural area (P = 0.0075), not have private insurance (P = 0.0001), and experience a greater decrease in income post injury (P = 0.010).

Conclusion

The delivery of care for people with SCI with low socioeconomic status may be remodeled to include patient-centered medical homes where care is directed by an SCI physiatrist. Further increased telehealth efforts would allow for SCI physiatrists to monitor health conditions remotely and focus on preventative treatment.

Keywords: Accessibility, Satisfaction, Healthcare services, Disability, Rehabilitation, Injury, Outpatient, Spinal cord injury

Introduction

Healthcare for individuals following spinal cord injury (SCI) plays a significant and necessary role in reducing an individual's risk of managing and preventing associated, secondary, or chronic conditions. People may experience a myriad of associated conditions that, based on the level and completeness of the injury, include sensory (e.g. skin), motor (e.g. paralysis), or autonomic issues (e.g. bowel and bladder issues).1–5 Although associated conditions are rarely preventable, medications, medical devices, cognitive or behavioral therapy, and assistive technology can assist with effective management.6

Individuals with SCI are also at greater risk of developing secondary conditions, which may include pain, obesity, fatigue, deconditioning, urinary tract infections, and pressure sores.6 Studies have reported that following SCI, individuals deal with around 8–14 secondary conditions per year.7,8 Secondary medical conditions complicate and exacerbate living with SCI by impacting the long-term overall health, productivity/employment, dignity, mobility, and independence of the individual.9 If not managed appropriately, these secondary conditions will lead to hospitalizations for complications including urinary tract infections, decubitus ulcers, pneumonia, or septicemia.10 Improved self-management skills and a proactive healthcare team is critical if secondary conditions are to be prevented.6

When individuals experience secondary conditions, they are at increased risk for developing chronic conditions such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, cancer, arthritis, diabetes, kidney disease, and asthma.6 This greater risk is associated with a variety of factors including pre-morbid health, age, greater physical inactivity, smoking, alcohol, obesity, high blood pressure and cholesterol, lack of access to healthcare, and numerous psychosocial issues.6,11,12 As a consequence of the increased risk of developing secondary and chronic conditions following SCI mortality rates are higher, with health-related factors the most significant predictors of life expectancy.13

As a result of the health conditions experienced following SCI, there is a significant financial burden for the patient and their families. Overall, individuals are estimated to spend from $508,904 to $1,044,197 yearly on healthcare utilization for their first year post injury and $67,415 to $181,328 on each subsequent year.14 Further, following SCI, it has been reported that people have a median of 22 contact points with the healthcare system in the year of injury compared to 3 for the general population.10

As a result there is a critical need for healthcare providers to effectively support and meet the unique and complex needs of individuals with SCI. However, several studies suggest that there are numerous barriers to utilization and accessibility of healthcare services following SCI. For example, accessible transportation and cost are considered significant barriers, as well as cognitive biases and attitudes towards care.15 Consequently, people living with SCI often face restricted access to services from specialists, and only half of those who need rehabilitation services will receive it.16 The issue is compounded by the fact that individuals face barriers when visiting their physicians or specialists (e.g. family physicians, physiatrists, internists, neurologists, neurosurgeons, orthopedic surgeons, urologists).17 Donnelly et al.18 reported that from a sample of 373, 93% had a family doctor, 63% an SCI physiatrist, and 56% had both. However, 27% of the sample reported that they could not use all the equipment in their family physicians’ offices with inaccessible exterior doorways and a lack of transfer aids cited as common issues.

Further, results of a recent national, online survey completed by 108 individuals post SCI 19 revealed that participants cited a lack of preventative health screenings and physician knowledge as barriers. For example, of the sample, 39.6% of women reported that they had not had a pelvic examination or Papanicolaou smear within the previous 3 years, and only 40% of women 50 years of age or older had received a mammogram in the previous year.19 When asked how well they felt their primary care physician understood medical concerns specific to their SCI, 33.3% of participants responded “not at all” or “a little,” 30.6% responded “moderately well,” and 36.1% responded “well” or “very well.”19 The Stillman et al. study did not examine differences in participant's healthcare utilization, perceived knowledge, and satisfaction between individuals who had an SCI physiatrist compared with only a primary care physician. This is important because few primary care physicians have training treating SCI-related medical issues and a limited number of patients with SCI in their practice.20 Additionally, all participants were recruited via internet, and no in-person or telephone surveys were performed. Therefore, the aim of this study was to describe the utilization, accessibility, and satisfaction of primary and preventative health-care services of community-dwelling individuals with SCI. The study was cross sectional, utilized a convenience sample, and included a brief survey.

Method

Participants

Participants were sampled from either (1) a registry of former patients at a single inpatient rehabilitation hospital or (2) current patients at a single outpatient SCI Clinic in the southwest United States who were consecutively scheduled for follow-up visits between 1/1/14 and 11/1/14. Individuals were recruited from the outpatient SCI Clinic in person and telephonically from the patient registry. Individuals listed on the patient registry were contacted telephonically if they had not followed up at outpatient SCI clinic after their inpatient rehabilitation. Inclusion criteria were ages 18 to 64 years old, traumatic- or non-traumatic SCI, and living in the community for at least 12-months post discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. The age was limited to 64 years as older adults face different health conditions (e.g. arthritis) and we would not have been able to recruit a large enough sample to stratify results by age. Exclusion criteria were severe cognitive impairment (determined by clinical judgement of treating SCI physiatrist) and pre-morbid mental illness (e.g. bi-polar) or developmental disability.

Procedure

All procedures were approved through the hospital's Institutional Review Board to ensure that the study was completed in an ethical manner. Individuals who met the inclusion criteria were approached either in person during a routine follow-up visit, or telephonically. Individuals were informed about the purpose of the study and given a survey cover letter that detailed the study requirements and that participation was voluntary. Participants were asked demographic and injury-related questions followed by a survey assessing utilization, accessibility, and satisfaction of primary and preventative healthcare services recommended by a physician. Preventative health services include age and sex specific recommendations by a physician such as a mammogram for females age 40 years and older or colonoscopy for males or females 50 years or older. It also included general health prevention recommendation such as having a flu shot recommended or asked about tobacco usage or frequency of exercise participation. Surveys were completed by a non-clinical research coordinator and took approximately15 minutes to complete, upon which individuals were finished with the study. Participants did not receive compensation.

Measures

Demographic information was obtained from a brief questionnaire and the patient's electronic medical record and included: age, sex, ethnic/racial identification, self-reported socioeconomic indicators (pre-injury income, current income, occupation, living situation, education level), and insurance status. Socioeconomic status was also estimated using the zip code provided to create a Geo Unit Quality Score, which is a function of the value and type of homes in that zip code, the education of those over the age of 25, and the occupations of the labor force, with the national average score in the US being 100. Injury-related information was also obtained and included: etiology of injury, traumatic or non-traumatic injury, level of injury, age at time of injury, and length of rehabilitation stay. Healthcare related information was obtained from a questionnaire developed by two SCI physiatrists, an SCI psychologist, and a research coordinator. The final survey consisted of 34 questions assessing health care utilization (e.g. “Have you been to the emergency room in the last 12 months?”), health care access (e.g. “Indicate whether or not the following doctors’ offices and/or equipment were accessible.”), preventative health information provided (e.g. “If you are a female aged 21 or over, do you get a PAP smear at least every 3 years?”), and satisfaction with current health care delivery (e.g. “My primary care physician is knowledgeable about my spinal cord injury needs?”). See the full survey in Supplemental Data File 1.

Data analytic approach

Data were summarized with means and standard deviations for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Additionally, a preventative care compliance score was calculated for each participant, which was defined as the number of preventative health activities the participant reported completing within a 12-month period divided by the total number of preventative health activities that were applicable to the participant based on gender and age. Analysis to compare between group differences was performed using t-tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. For categorical variables with low counts, Fisher exact tests were used. Statistical significance was set at the 0.05 level and all analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Additional analysis was performed to determine which socioeconomic factors were associated with each other. χ2 tests were used when comparing categorical variables, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used when comparing continuous or ordinal variables to categorical variables, and Spearman correlations were used for two continuous or ordinal variables.

Results

A total of 149 participants met the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were contacted. One hundred completed the survey in person during a routine follow-up visit, 42 telephonically, and 7 people refused, resulting in a final sample of 142 and 95% response rate. Of the 7 people who refused, 1 was in person (survey was taking too long) and 6 were telephonic (5 did not return calls, 1 did not have time). The 100 participants who completed the survey in person were consecutive patients seen between 1/1/14 and 11/1/14 who met inclusion criteria returning for their regular clinic visit. The 42 participants who completed the survey telephonically were from the patient registry and had never followedup at the outpatient SCI Clinic but met inclusion criteria. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the study participants and Table 2 summarizes injury-related information.

Table 1.

Summary of demographic characteristics

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 142) | Phone (N = 42) | Visit (N = 100) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at time of survey | 40.8 ± 13.0 | 42.0 ± 13.5 | 40.3 ± 12.8 |

| Male Sex | 92 (65%) | 29 (69%) | 63 (63%) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 16 (11%) | 6 (14%) | 10 (10%) |

| Race | |||

| Asian | 4 (3%) | 3 (7%) | 1 (1%) |

| Black/African American | 16 (11%) | 6 (14%) | 10 (10%) |

| White | 119 (84%) | 33 (79%) | 86 (86%) |

| More than one race | 3 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (3%) |

| Geo Unit Quality Score | 101.1 ± 13.7 | 97.9 ± 11.7 | 102.5 ± 14.3 |

| Education Level | |||

| Elementary school | 2 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (1%) |

| High school Diploma or Equivalent | 63 (44%) | 18 (43%) | 45 (45%) |

| Associate's/ Vocational/Technical Degree | 27 (19%) | 9 (21%) | 18 (18%) |

| Bachelor's Degree | 29 (20%) | 10 (24%) | 19 (19%) |

| Postgraduate Degree | 21 (15%) | 4 (10%) | 17 (17%) |

| Relationship status | |||

| Single | 65 (46%) | 20 (48%) | 45 (45%) |

| Married | 58 (41%) | 16 (38%) | 42 (42%) |

| Divorced | 17 (12%) | 5 (12%) | 12 (12%) |

| Widowed | 2 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (1%) |

| Change in Income After Injury * | |||

| Decreased | 48 (34%) | 19 (13%) | 29 (29%) |

| Stayed same | 53 (37%) | 12 (29%) | 41 (41%) |

| Increased | 21 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (21%) |

| Not reported | 20 (14%) | 11 (26%) | 9 (9%) |

| Type of Insurance | |||

| Self Pay/Uninsured | 4 (3%) | 3 (7%) | 1 (1%) |

| Medicare | 26 (18%) | 11 (26%) | 15 (15%) |

| Medicaid | 7 (5%) | 3 (7%) | 4 (4%) |

| Medicare and Medicaid | 10 (7%) | 5 (12%) | 5 (5%) |

| Private | 64 (45%) | 14 (33%) | 50 (50%) |

| Private and Public | 31 (22%) | 6 (14%) | 25 (25%) |

*Only includes those who reported both current and prior to injury income

Table 2.

Summary of injury information

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 142) | Phone (N = 42) | Visit (N = 100) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at injury | 33.0 ± 13.2 | 38.0 ± 13.8 | 30.6 ± 12.4 |

| Years since injury | 8.1 ± 4.6 | 4.8 ± 5.9 | 9.6 ± 5.7 |

| Paraplegic or Tetraplegic | |||

| Paraplegic | 70 (49%) | 22 (52%) | 48 (48%) |

| Tetraplegic | 67 (47%) | 17 (40%) | 50 (50%) |

| Unknown | 5 (4%) | 3 (7%) | 2 (2%) |

| Level of injury | |||

| Cervical | 67 (47%) | 19 (45%) | 48 (48%) |

| Thoracic | 60 (42%) | 17 (40%) | 43 (43%) |

| Lumbar | 10 (7%) | 5 (12%) | 5 (5%) |

| Unknown | 5 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 4 (4%) |

| AIS Impairment Scale | |||

| A = Complete | 73 (51%) | 18 (43%) | 55 (55%) |

| B = Sensory Incomplete | 14 (10%) | 5 (12%) | 9 (9%) |

| C = Motor Incomplete | 21 (15%) | 8 (19%) | 13 (13%) |

| D = Motor incomplete | 22 (15%) | 3 (7%) | 19 (19%) |

| Unknown | 12 (8%) | 8 (19%) | 4 (4%) |

Healthcare utilization

The majority of participants reported seeing a primary care physician (79%) followed by an SCI physiatrist (77%), urologist (50%), wound care specialist (27%), pain management specialist (22%), neurosurgeon (19%), and orthopedic surgeon (13%). Of the female participants, 28% had visited an obstetrician/gynecologist. Forty-three percent of the sample reported having an ER visit in the past 12-months with 21% having multiple visits. The primary reasons for the visit were genital/urological (15%), skin problems (7%), pneumonia (4%), and other (23%) (reactions to medications, bleeding, back pain, and fatigue). Table 3 summarizes the preventative care screenings completed by participants and procedures/questions completed during their annual checkup. Sixty-six percent of participants reported completing all of the preventative care measures that were applicable to them based on age and gender (e.g. annual Papanicolaou smear for females aged 21–65).

Table 3.

Preventative care – Preventative care screenings completed and procedures/questions completed at annual checkup

| Preventative care (if applicable)* | Overall | Phone | Visit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of completed measures | 66% ± 16% | 66% ± 17% | 66% ± 16% |

| Per health guidelines | |||

| Papanicolaou smear | 31 (63%) | 7 (58%) | 24 (65%) |

| Mammogram | 15 (71%) | 3 (75%) | 12 (71%) |

| Colonoscopy | 26 (54%) | 7 (50%) | 19 (56%) |

| Annual checkup | |||

| Flu Shot | 78 (55%) | 21 (50%) | 57 (57%) |

| Exercise 5 days a week | 40 (28%) | 13 (31%) | 27 (27%) |

| Cholesterol checked | 80 (57%) | 27 (68%) | 53 (53%) |

| Blood glucose checked | 90 (64%) | 25 (63%) | 65 (65%) |

| Blood pressure | 138 (99%) | 39 (98%) | 99 (99%) |

| Weight checked | 83 (59%) | 24 (60%) | 59 (59%) |

| Asked about tobacco products | 102 (73%) | 26 (65%) | 76 (76%) |

| Asked about alcohol consumption | 100 (71%) | 25 (63%) | 75 (75%) |

| Asked about diet | 79 (56%) | 25 (63%) | 54 (54%) |

| Asked about contraception use | 25 (19%) | 9 (13%) | 16 (17%) |

*All percentages are calculated using the total number of patients for which each preventative care measure is applicable.

Differences in utilization were also found based on demographic and socioeconomic related variables. Individuals who visited an SCI physiatrist in the past 12 months (n = 110) were significantly more likely to live in an urban area (P = 0.0075), have private insurance (P ≤ 0.0001), and see a specialist (P = 0.0002), when compared to individuals who did not (n = 32). Conversely, individuals who did not follow up with an SCI physiatrist were significantly more likely to report a reduction in household income following injury (P = 0.0100). Further, individuals who reported having an ER visit in the past 12-months reported completing less post-secondary education (P = 0.0386) and having lower household income (P = 0.0004) than people who did not. This result is emphasized by the finding that individuals who had an ER visit had a significantly lower Geo Unit Quality Score (98) compared to participants who did not (104; P = 0.0170). No other significant differences were found in utilization based on demographic, injury, or socioeconomic variables. When comparing socioeconomic related variables, significant associations or differences were found between education and marital status (P = 0.006), education and private insurance (P = 0.02), marital status and private insurance (P ≤ 0.001), marital status and income (P < 0.001), and private insurance and income (P < 0.001). Significant Spearman correlations were found between education and current income (r = 0.27, P = 0.001) and income and Geo Unit Quality Score (r = 0.39, P < 0.001).

Accessibility

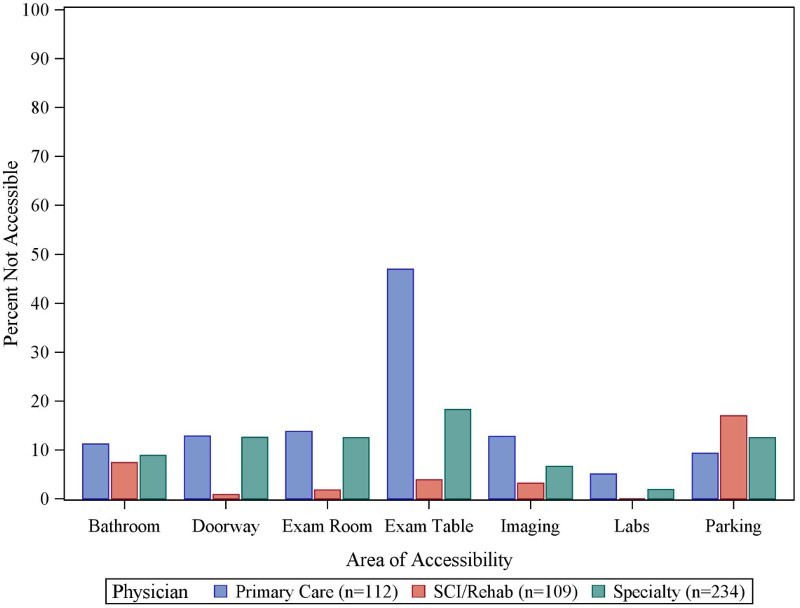

Figure 1 displays the percentage of participants that reported accessibility barriers from their primary care physician, SCI physiatrist, and specialty physician's offices (i.e. Obstetrician, Pain Management, Urologist, Orthopedic Surgeon, Neurosurgeon, Wound Care). The responses for specialty physician's office visits were aggregated to reflect the total number of visits for the entire sample. Thus, of the 142 total participants, individuals made a total of 234 specialty visits. Participants responded not applicable in this section if they did not see the specified type of provider or receive the specified service at their provider's office (e.g. labs). Participants reported SCI physiatrist's offices as the most accessible (except for parking), followed by specialty and primary care.

Figure 1.

Accessibility issues with primary care, SCI/Rehab, and specialty physician's offices

Satisfaction with healthcare

The majority of participants (66%) reported that their primary care physician was knowledgeable about their SCI needs (somewhat agree, agree, or strongly agree) and 100% viewed their SCI physiatrist as knowledgeable. Finally, more than half of individuals (55%) agreed that their physicians communicated well (somewhat agree, agree, or strongly agree), while only 14% disagreed (somewhat disagree, disagree).

Discussion

Overall, results indicate that utilization, accessibility, and satisfaction with healthcare was higher in some areas, yet similar for others when compared to previous SCI research and population level data.21 For utilization, 99% of individuals in the current sample reported that they had healthcare visits in the past 12 months, which is consistent with previous SCI research.10,19,22 This level of utilization is significantly higher than population data reported in the 2013 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) which indicated that 24.7% of the population aged 18–44 and 15.1% aged 45–64 reported no healthcare visits in the previous 12 months.21 The pattern of primary care, SCI physiatrist, and specialty utilization in the current study is also consistent with previous SCI literature,10,18,19,23 and emphasizes another disparity compared to the general population who report less visits with a primary care physician (62.7% for ages 18–44 and 46.7% for ages 45–64) or specialist (44.8%).21 Again, increased healthcare utilization may be attributed to the fact that individuals post SCI live with a greater number of 23health conditions relative to the general population.10,22,23

For preventative health services, qualified participants in the current sample had rates consistent with previous SCI literature19 and population level data (72.6% mammogram, 63.8% Papanicolaou smear, 55.5% colonoscopy, and 57.7% flu vaccines).21 In addition, accessibility issues were consistent with previous SCI literature19 reporting that examination tables are considered the least accessible aspect of primary care offices, which may be due to general practitioners not having height adjustable exam tables or qualified staff to accommodate individuals in wheelchairs.19

However, there were several differences between the current results and previous literature that warrant discussion. While the majority of participants were satisfied (66%) with their physician's knowledge of SCI and communication with each other (55%), this finding is relatively inconsistent with existing SCI literature. For example, Stillman et al.19 reported that 65.7% of the sample perceived they were provided incomplete care by a primary care or specialty physician and only 53.7% were satisfied with their primary care. A potential reason for this low satisfaction is provided by Cox et al.15 who found that the greatest perceived barrier for needs being met was the limited knowledge of SCI by their local specialist.15 The fact that 100% of respondents in the current study were satisfied with their SCI physiatrist's knowledge supports this notion. In addition, results from the current study indicate that individuals visited the ER (43% of sample within the past 12-months) less frequently than other samples of individuals with SCI (57%),24 although the primary reasons for ER visits (e.g. genital/urological, skin problems, pneumonia) are consistent with previous findings.10,24 Again, a primary difference with the current sample was that the majority of participants were under the care of a SCI physiatrist.

There were several differences in utilization based on socioeconomic factors. For example, individuals with less post-secondary education, lower household income, and lower Geo Unit Quality Score were more likely to visit the ER. Conversely, individuals who had visited an SCI physiatrist were significantly more likely to live in an urban area, experience a smaller decrease in income post injury, have private insurance, and visit a specialist. Both findings are consistent with previous literature, which consistently reports that insurance coverage limitations lead to poor access to rehabilitative services (e.g. visiting an SCI specialist) for people with chronic or disabling conditions.6,15,16,19 Likewise, Beatty et al.16 reported that income level was significantly correlated with difficulty receiving care and that individuals with incomes lower than $20,000 were least likely to receive care when needed. For individuals living in more rural areas, the literature suggests that individuals have lower healthcare utilization (e.g. physician, specialist visits) due to issues with access and availability of healthcare resources.23,25 However, this may result in individuals only option for receiving care being the ER.23

If these issues are to be addressed there are several points for consideration. First, access to care for people with Medicaid needs to be improved so that individuals can visit an SCI physiatrist. In certain states (e.g. Texas) this is dictated by state legislature and improved data demonstrating the benefits of regular visits with an SCI physiatrist is needed (e.g. reduced ER visits, readmissions). However, Medicaid coverage does vary by state so this challenge does not apply to all SCI physiatrists. Second, having a patient-centered medical home26,27 specifically for individuals living with SCI offers an opportunity to centralize care and improve quality and efficiency. This would be particularly beneficial to people with SCI living in a rural area as it would allow them to visit one location and receive all services (e.g. wound, urological, pain). An SCI physiatrist would direct the individuals care at the patient centered medical home. Accessibility of care could be further enhanced with greater utilization of telehealth. For example, the SCI physiatrist could communicate via videoconference to individuals living in rural areas and evaluate, diagnose, and prescribe remotely (e.g. homehealth visit, lab, prescription). This ability to connect remotely would allow the SCI physiatrist to proactively treat individuals rather than allowing an issue to worsen and result in an ER visit. With the Veteran Affairs home telehealth program as an example,28 and recognized need to utilize mobile health technology to support the complex needs of people with chronic conditions,29 there is an opportunity to better serve people living with SCI. Finally, healthcare provider (e.g. physician, nursing) training should include content on the unique needs of people with a disability in general, including those with SCI. As results from the current study and previous literature indicate that individuals with SCI are less satisfied with the knowledge of their primary care physician, it is clear that improved training is required.

Limitations and future research directions

It is important to note that there are several limitations with the study. First, the study only included participants from one inpatient hospital and outpatient SCI Clinic in a single geographic area of the United States so results may not be generalizable to other clinics and regions. However, with variations in healthcare coverage existing between States (e.g. Medicaid coverage), obtaining utilization and accessibility information that is applicable to all geographic regions will be challenging. Future research efforts could be completed in different hospital systems, states or regions to further examine trends in utilization and barriers faced. Second, it is also important to note some similarities and differences between the current sample and the population level data available from the National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center.30 For example, the percentage of people with insurance (97% current sample; 96% population level) and a household income more than $25,000 (70%; 60%) was similar. However, the number of people with a college degree (35%; 10.3%) differed significantly, again influencing the generalizability of results. Third, based on the differences found in utilization due to socioeconomic factors, it is critical that future efforts engage this subgroup of people living with an SCI who are not necessarily part of a healthcare system. By treating underserved individuals as part of a research or quality project, differences in patient outcomes and cost to the healthcare system could be examined. Fourth, the survey only included self-report data with no objective information on healthcare utilization. Future research should use county or state level data to objectively identify trends in utilization. In addition, individuals who are high utilizers of the healthcare system should be identified and engaged in telehealth programs or patient centered medical homes, as described above, to proactively treat their health. Fifth, the sample was limited to individuals with a maximum age of 64 years old. This reduced the number of respondents and also missed valuable data on older adults living with SCI who are at greater risk of morbidity and mortality. If the health of individuals is to be addressed across the lifespan it is important that healthcare utilization be examined in older adults living with SCI. Finally, the survey did not include questions related to sexual health or sexuality following SCI, which are important needs for the population as limited resources are available and SCI health care providers may be uncomfortable assessing sexuality.31 While the survey asked about contraception use we did not obtain information regarding the participants sexuality needs living with SCI and should be examined.

As we address the healthcare needs of people with SCI it is important to consider the objectives of Healthy People 2020, which includes national health promotion and disease-prevention goals for the U.S. Specifically, objectives include reducing the proportion of people with disabilities who report delays in receiving primary care and having 100% of people complete preventative care measures.32 Based on current results and previous literature, there is an opportunity for healthcare providers to improve compliance with health screenings. In addition, another objective of Healthy People 2020 is to reduce the proportion of people with disabilities, including SCI, who report physical or program barriers to local health and wellness programs.32 When building new and retro-fitting existing medical facilities it is critical to consider the principle of “universal design”, which ensures that accessibility to buildings and public spaces is fully accessible for people with disabilities.33 This approach to the design of healthcare facilities ensures physical accessibility for everyone.

Conclusion

Despite their complex needs and higher rates of utilization when compared to the general population, individuals with SCI and disability in general continue to face barriers when accessing healthcare resources. Accessible facilities, improved training for healthcare professionals about the unique needs of people with SCI, and the enhanced use of technology to enable people living in rural areas with transportation barriers to communicate with healthcare providers is needed. Further, as the high cost of healthcare and access to coverage are major barriers preventing individuals from receiving the appropriate services, the delivery model for people with SCI may need to adapt to include those who are currently not getting adequate care. For example, multi-disciplinary outreach services can eliminate costs and travel for people with SCI. In addition, research and analysis on socio-demographic factors such as transportation, work-related issues, quality of life, needs for better healthcare, and psychological factors can assist in learning more about the needs of individuals with SCI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thanks the patients that participated in the study and were gracious enough to give us their time. The authors would also like to thank Samantha Cleveland for her logistical support.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors None.

Funding None.

Conflicts of interest None

Ethics approval None.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here at doi:10.1080/10790268.2016.1184828.

References

- 1.Paker N, Soy D, Kesiktas N, Nur Bardak A, Erbil M, Ersoy S, et al. Reasons for rehospitalization in patients with spinal cord injury: 5 years’ experience. Int J Rehabil Res 2006;29(1):71–6. doi: 10.1097/01.mrr.0000185953.87304.2a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savic G, Short DJ, Weitzenkamp D, Charlifue S, Gardner BP.. Hospital readmissions in people with chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2000;38(6):371–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardenas DD, Hoffman JM, Kirshblum S, McKinley W.. Etiology and incidence of rehospitalization after traumatic spinal cord injury: a multicenter analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85(11):1757–63. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkowitz M. Assessing the socioeconomic impact of improved treatment of head and spinal cord injuries. J Emerg Med 1993;11 Suppl 1:63–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirshblum S, Campagnolo D.. Spinal Cord Medicine. Second ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rimmer JH, Rowland JL.. Health promotion for people with disabilities: implications for empowering the person and promoting disability-friendly environments. Am J Lifestyle Med 2008;2(5):409–20. doi: 10.1177/1559827608317397 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloemen-Vrencken JH, Post MW, Hendriks JM, De Reus EC, De Witte LP.. Health problems of persons with spinal cord injury living in the Netherlands. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(22):1381–9. doi: 10.1080/09638280500164685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunn M, Love L, Ravesloot C.. Subjective health in spinal cord injury after outpatient healthcare follow-up. Spinal Cord 2000;38(2):84–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Post M, Noreau L.. Quality of life after spinal cord injury. J Neurol Phys Ther 2005;29(3):139–46. doi: 10.1097/01.NPT.0000282246.08288.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dryden D, Saunders L, Rowe B, May L, Yiannakoulias N, Svenson L, et al. Utilization of health services following spinal cord injury: a 6-year follow-up study. Spinal Cord 2004;42(9):513–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer M, Krishnamoorthi V, Smith B, Evans C, Andre J, Ganesh S, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in patients with spinal cord injuries/disorders. Am J Nephrol 2012;36(6):542–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LaVela SL, Evans CT, Prohaska TR, Miskevics S, Ganesh SP, Weaver FM.. Males aging with a spinal cord injury: prevalence of cardiovascular and metabolic conditions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93(1):90–5. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.07.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krause JS, Saunders LL.. Health, secondary conditions, and life expectancy after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92(11):1770–5. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center Spinal cord injury facts and figures at a glance [document on the internet]. 2013. Available from https://www.nscisc.uab.edu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Cox RJ, Amsters DI, Pershouse KJ.. The need for a multidisciplinary outreach service for people with spinal cord injury living in the community. Clin Rehabil 2001;15(6):600–6. doi: 10.1191/0269215501cr453oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beatty PW, Hagglund KJ, Neri MT, Dhont KR, Clark MJ, Hilton SA.. Access to health care services among people with chronic or disabling conditions: patterns and predictors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003;84(10):1417–25. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(03)00268-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.John Hopkins Medicine Health Library Spinal cord injury. Available at. http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/healthlibrary/conditions/physical_medicine_and_rehabilitation/spinal_cord_injury_85,P01180/. Accessed 27 April 2016.

- 18.Donnelly C, McColl M, Charlifue S, Glass C, O'Brien P, Savic G, et al. Utilization, access and satisfaction with primary care among people with spinal cord injuries: a comparison of three countries. Spinal Cord 2006;45(1):25–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stillman MD, Frost KL, Smalley C, Bertocci G, Williams S.. Health care utilization and barriers experienced by individuals with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95(6):1114–26. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirshblum S. The value of comprehensive primary care follow-up. J Spinal Cord Med 2014;37(4):370. doi: 10.1179/2045772313Y.0000000190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Health in the United States Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levi R, Hultling C, Seiger Å. The Stockholm spinal cord injury study. Health-related issues of the Swedish annual level-of-living survey in SCI subjects and controls. Spinal Cord 1995;33(12):726–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munce S, Guilcher S, Couris C, Fung K, Craven BC, Verrier M, et al. Physician utilization among adults with traumatic spinal cord injury in Ontario: a population-based study. Spinal Cord 2009;47(6):470–6. doi: 10.1038/sc.2008.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skelton F, Hoffman JM, Reyes M, Burns SP.. Examining health-care utilization in the first year following spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2015;38(6):690–5. doi: 10.1179/2045772314Y.0000000269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guilcher S, Munce S, Couris C, Fung K, Craven B, Verrier M, et al. Health care utilization in non-traumatic and traumatic spinal cord injury: a population-based study. Spinal Cord 2009;48(1):45–50. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Centered Medical Homes. 2015. [cited 2015 June 12]; Available from http://pcmh.ahrq.gov/.

- 27.Hernandez B, Damiani M, Wang TA, Driscoll C, Dellabella P, LePera N, et al. Patient-centered medical homes for patients with disabilities. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil 2015;14(1):61–75. doi: 10.1080/1536710X.2015.989562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hogan TP, Wakefield B, Nazi KM, Houston TK, Weaver FM.. Promoting access through complementary ehealth technologies: recommendations for VA's home telehealth and personal health record programs. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26 (Suppl 2):628–35. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1765-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steele Gray C, Miller D, Kuluski K, Cott C.. Tying ehealth tools to patient needs: exploring the use of ehealth for community-dwelling patients with complex chronic disease and disability. JMIR Res Protoc 2014;3(4):e67. doi: 10.2196/resprot.3500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center 2014 Annual Report Complete Public Version [document on the internet]. 2015 [cited 2015 June 12]. Available from https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/.

- 31.Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Sexuality and reproductive health in adults with spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33(3):281–336. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2010.11689709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.United States Department of Health and Human Services Disability and Health Objectives. 2014 [cited 2015 June 12]. Available from www.healthypeople.gov.

- 33.Lid IM. Universal design and disability: an interdisciplinary perspective. Disabil Rehabil 2014;36(16):1344–9. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.931472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.