Abstract

Adenosine (ADO) is a potent bronchoconstrictor in allergic patients and has been shown to increase the release of histamine from human lung tissues. Antagonists of ADO Α1 and A2A receptors are not effective in attenuating these effects. Therefore, involvement of ADO A3 receptors in the bronchoconstrictor and/or inflammatory effects have to be considered. Eosinophils also play a pivotal role in allergic diseases such as asthma, thus it is natural to consider a link between the A3 receptor and eosinophils. Human peripheral blood eosinophils express the ADO A3 receptor as indicated by detection of the transcript for A3 receptors in polymerase chain reaction-amplified cDNA derived from the cells. A3 receptors on eosinophil membranes were characterized using the A3 receptor agonist radioligand 125l-labeled AB-MECA, which yielded Bmax and Kd values of 1.31 pmol/mg protein and 3.19 nmol/L, respectively. Treatment of eosinophils with the highly potent and selective A3 receptor agonist CI-IB-MECA clearly induced Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ pools followed by Ca2+ influx, suggesting the presence of phospholipase C-coupled A3 receptors. In contrast, the ADO receptor agonists CPA and CGS 21680, selective for A1 and A2A receptors, respectively, at concentrations of ≤30 μmol/L did not elevate the intracellular Ca2+ level. These results attest to the existence of ADO A3 receptors on eosinophils and suggest that ADO stimulates these cells to release Ca2+ from intracellular stores via the activation of A3 receptors.

Graphical abstract

Edema. Despite extensive interstitial edema surrounding the small venule in this myocardial biopsy, the interendothelial cell junctions (arrows) are closed. Original magnification × 10,500. (Courtesy of Ann M. Dvorak, MD, Department of Pathology, Beth Israel Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02215.)

EOSINOPHILS ARE thought to be closely associated with many allergic diseases such as allergic rhinitis, bronchial asthma, or atopic dermatitis.1,2 Under such circumstances, eosinophils infiltrate the tissues and release mediators that are responsible for tissue damage and inflammation.3 Among the allergic diseases, asthma in particular is known to be connected with accumulation of these cells. The severity of asthma correlates with levels of circulating and bone marrow eosinophils, and the clinical evaluation of asthma usually requires a determination of eosinophil count.4,5 The histopathology of asthma shows major eosinophilic infiltration in the epithelium and lamina propria of bronchial mucosa and an associated deposition of eosinophil granule cationic protein.6–9 Eosinophil granule proteins such as major basic protein (MBP) are able to stimulate the release of histamine, which provokes bronchoconstriction, from mast cells or basophils.10 Therefore, knowledge of the factors that regulate the function of eosinophils in tissues is important for the understanding of allergic diseases including asthma.

The role of adenosine (ADO) in asthma has been explored. In asthmatics, inhalation of adenosine causes bronchoconstriction.11 ADO has been shown to increase the release of histamine from human lung fragments.12 This effect is not a direct action of ADO on smooth muscles, but rather occurs in the bronchi through the release of histamine or leukotriene from basophils and mast cells.13 This constriction is blocked by a combination of histamine and leukotriene antagonists.13 In asthmatics, mean ADO concentrations measured in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid are significantly elevated relative to normal patients.14 The mechanism of this ADO-induced constriction has been thought to be a response of mast cells to ADO.13 As mentioned above, eosinophils stimulate mast cells and are able to excrete strong bronchoconstrictors such as leukotriene C4 (LTC4) and platelet-activating factor (PAF) to stimulate directly smooth muscle in bronchi.15,16 Thus, there exists a strong likelihood that eosinophils respond to ADO and other ADO receptor specific agents.

Based on biochemical and pharmacological criteria, two subtypes of ADO receptors, A1 and A2, have been differentiated. However, the potency of xanthines as antagonists of ADO A1 and Α2A receptors are not predictive of effects in blocking bronchoconstriction.17 Therefore, the involvement of another member of the ADO receptor family has to be considered. Recently, a third subtype of ADO receptor, the A3 receptor, was cloned from rat brain and rat testes cDNA libraries.18,19 Its activation stimulates phosphatidyl inositol metabolism in antigen-exposed mast cells and inhibits adenylyl cyclase in transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells.18 A preliminary report by Bai et al20 suggests that A3 receptors in the human lung may be associated with eosinophils rather than mast cells. We hypothesized that human peripheral blood eosinophils might express A3 receptors and, if present, that these receptors could have a role in cell function. As with mast cells, A3 receptor activation may hypothetically stimulate eosinophils, followed by phagocytosis, degranulation, production of cytokines, adhesion to endothelial surfaces, transmigration to tissues, and so forth. In the present study, we demonstrate that ADO A3 receptors are expressed on human eosinophils in relatively high density. Moreover, we found that the selective A3 receptor agoagonist, 2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-adenosine-5-N-methyluronamide (Cl-IB-MECA), induces Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ pools followed by Ca2+ influx.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eosinophil purification

Eosinophils were purified from peripheral blood of patients by Dr Steve Mawhorter at National Institutes of Health and by Dr Bruce S. Bochner (Johns Hopkins Asthma and Allergy Center, Baltimore, MD) with mild allergic disease and hypereosinophilia. The donors with significantly increased eosinophilia were idiopathic hypereosinophilia patients and were not on drug treatment. Purification was carried out using Percoll (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) density gradient centrifugation and negative selection with anti-CD16 monoclonal antibody (MoAb) and immunomagnetic beads coated with goat antimouse IgG (Dynabeads M450; Dynal AS, Oslo, Norway) as previously described.21 The purity of eosinophils based on light microscopic examination of cytocentrifugation preparations stained by Diff-Quik (American Scientific Products, McGraw Park, IL) was >99%.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

The eosinophils used in this assay were carefully isolated with particular attention given to purity. The purity based on light microscopic examination was 100%, based on random counting of 500 cells. Total RNA was prepared by the single-step method22 with slight modifications (RNA STAT-60; TEL-TEST “B”, INC, Friendswood, TX). One microgram of total RNA was incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes with 1 U of RNase-free DNase I (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN), and the first strand cDNA was synthesized with 0.5 μg of oligo (dT)l2–18 primer and 200 U of the cloned M-MLV reverse transcriptase (SUPERSCRIPT II preamplification system; Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD).

The human A3 ADO receptor sequence was amplified with 5′ primer sequence (ACCCCCATGTTTGGCTG) and 3′ primer sequence (GCACAAGCTGTGGTACCTCA) giving a 361 bp product.23,24 The PCR was carried out in 50 μL using the following conditions: the initial denaturing step at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds, except the last elongation at 72°C for 10 minutes. Subsequently, 10 μL of PCR products were run on the 4% NuSieve 3:1 agarose gel (FMC BioProducts, Rockland, ME) and examined by ethidium bromide staining.

Membrane preparation and radioligand binding

Binding studies using the high affinity ADO A3 receptor radioligand [125I]N6-(3-iodo-4-aminobenzyl)-adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide ([125I]AB-MECA; Amersham Life Science, Inc, Arlington Heights, IL) were performed and analyzed as described previously.25 For binding studies, eosinophils were centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 10 minutes on a desktop centrifuge. The pellet was washed with a lysis buffer (10 mmol/L Tris, 5 mmol/L EDTA, pH 7.4) at 5°C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 50 mmol/L Tris, 10 mmol/L MgCL, 1 mmol/L EDTA, pH 8.26 at 5°C (50/10/1 buffer) and disrupted by Dounce homogenization on ice (20 strokes by hand). After centrifugation at 43,000g and 5°C for 10 minutes, the crude membrane pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer to yield a protein concentration of 0.2 mg/mL (corresponding to ~8 × 106 cells). ADO deaminase was added to provide a final concentration of 3 U/mL. A quota of 2 × 105 cells was sufficient for each binding assay.

Binding assays were performed in the lysis buffer in glass tubes with each tube containing 100 μL of the membrane suspension, 50 μL of [l25I]AB-MECA at an optional concentration and 50 μL of ADO deaminase to provide a final concentration of 3 U/mL, in the pH 7.4 lysis buffer. Membranes prepared from HEK-293 cells stably expressing the human A3 receptor were obtained from Receptor Biology, Inc (Baltimore, MD). Incubations were carried out in duplicate for 1 hour at 37°C, in the presence of 1 μmοΙ/L xanthine amine congener (XAC), added to block radioligand binding to A1 receptors. The incubation was terminated by rapid filtration over Whatman GF/B filters, using a Brandell cell harvester (Gaithersburg, MD). Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 200 μmοl/L 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA). A concentration of 0.4 nmol/L [125I]AB-MECA was used in the competition experiments at A3 receptors, and IC50 values were converted to Ki values as described.26 Binding assays at A1- and A2A-receptors were performed as described.27 ADO receptor agonists and antagonists were obtained from Research Biochemicals (Natick, MA) or synthesized as reported.27

Measurement of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration

The cells (106 cells/mL) were incubated in the presence of 1 μg fluo-3AM in a 1:1 mixture of RPMI 1640 and Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) buffer for 40 minutes at room temperature. The cells were suspended in a 1:1 mixture of RPMI medium and HBSS buffer at approximately 106 cells/mL. Ten milliliters of a dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) solution containing 10 μg of fiuo-3 AM (Molecular Probes, Inc, Eugene OR) was added to 10 mL of the cell suspension, and cells were left in the dark for 40 minutes at room temperature. The cells were centrifuged at 1,200 rpm for 10 minutes to remove extracellular dye and were resuspended in HBSS. Two milliliters of cell suspension was added to each cuvette with a magnetic stir bar, and the fluorescence intensity of fluo-3 AM was quantified using a Deltascan fluorescence spectrophotometer (Photon Technology International, Inc, Brunswick, NJ) with the excitation wavelength set at 506 nm and emission wavelength monitored at 526 nm. The maximum fluo-3 fluorescence (Fmax) was determined by adding Triton-X (0.025%) or 4-bromoA23187 (1 μmοΙ/L) in the presence of 1 mmol/L Ca2+. The minimum fluorescence (Fmin) was determined following quenching of fluo-3 with 0.5 mmol/L ethylene glycol-bis-(β-aminoethyl ether)-Ν,Ν,Ν′,Ν′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA).

RESULTS

Expression of A3ADO receptors on eosinophils

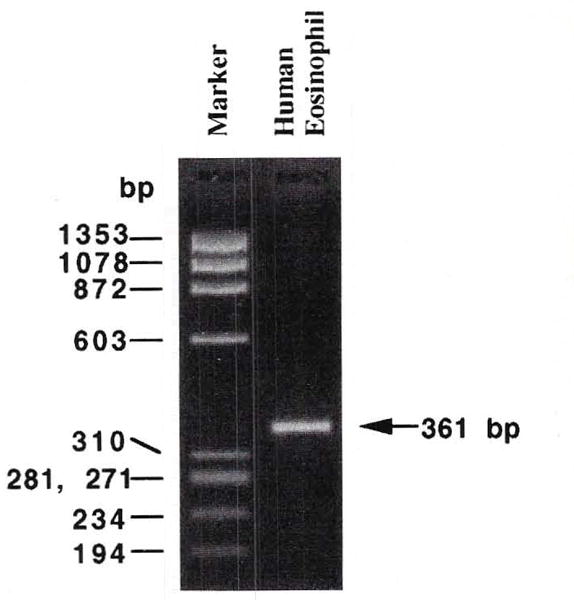

Amplification of a A3 receptor-specific sequence was performed from reverse-transcribed mRNA obtained from eosinophils. The agarose-gel electrophoresis revealed the single band of the expected 361-bp PCR product, indicating the existence of ADO A3 receptor on eosinophils (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

RT-PCR products obtained from eosinophils and separated on a 4% NuSieve 3:1 agarose gel. The PCR product is 361 bp long, according to the human A3 adenosine receptor sequence.

Radioligand binding

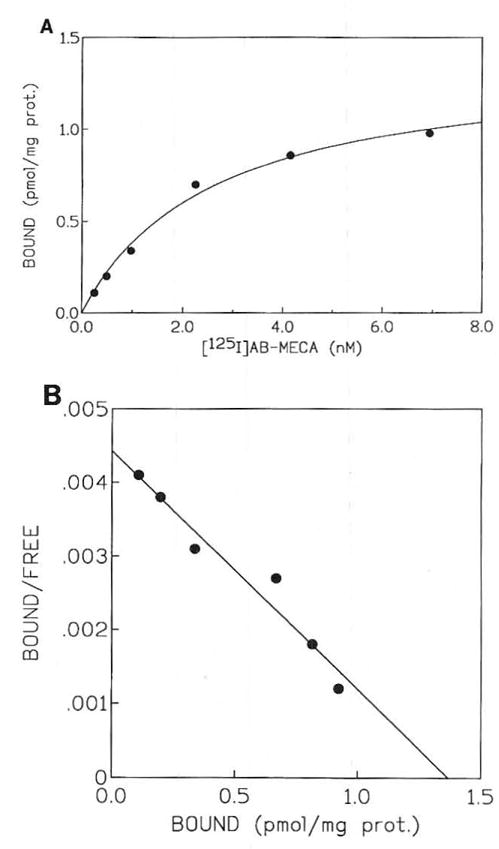

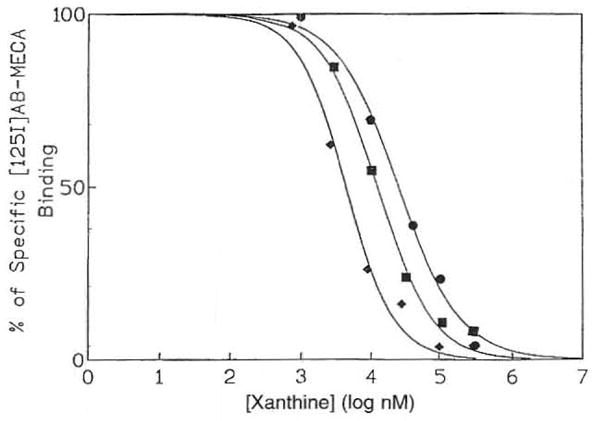

The level of expression of the ADO A3 receptor in human eosinophils was also determined using the high affinity radioligand [125I]AB-MECA25 in saturation binding experiments (Fig 2). This ligand bound to a single, saturable high affinity site in membranes from eosinophils, with Κd and Bmax values of 3.19 ± 0.21 nmol/L and 1.31 ± 0.15 pmol/mg membrane protein, respectively (four experiments). At cloned human A3 receptors membranes of HEK293 cells a Kd value of 0.59 nmol/L for [l25I]AB-MECA saturation was determined.26 Xanthines selected for competition experiments included an amine congener, XAC, and two carboxylic acid derivatives, 8-[4-[[[carboxy]methyl]-oxy]phenyl]-l,3-dipropylxanthine (XCC) and 1,3-dipropyl-8-[4-(z-carboxyethenyl)phenyl]xanthine (BWA 1433). Selected xanthine analogues competed for [125I]AB-MECA binding with a rank order of potency of BWA 1433 >XCC ≈XAC, indicative of A3 receptor pharmacology (Fig 3). The Ki values of 5.23 ± 1.46, 20.0 ± 8.5, and 22.6 ± 7.0 μmol/L were obtained, respectively. These values for [l25I]AB-MECA are comparable with those obtained in CHO cells stably transfected with the A3 receptor cDNA derived from rat brain.18 At cloned human A3 receptors membranes of HEK293 cells the Ki values versus [125I]AB-MECA for XAC and BWA 1433 were determined to be 0.600 ± 0.053 and 0.664 ± 0.031 μmol/L, respectively, assuming a Kd value of 0.59 nmol/L for the radioligand at this receptor.26 At A1 receptors, these xanthines bind with considerably greater affinity.28

Fig 2.

(A) Typical saturation of binding isotherms for specific binding of [125I]AB-MECA in human eosinophil membranes (from hypereosinophilia patients). (B) The corresponding Scatchard transformation is shown. Kd and Bmax values of 3.17 ± 0.23 nmol/L and 1.29 ± 0.19 pmol/mg (n = 3), respectively, were calculated.

Fig 3.

Representative competition curves for inhibition of binding of 125I-AB-MECA to eosinophil membranes (from hypereosinophilia patients) by various ADO receptor antagonists: BWA 1433 (◆); XCC (■); and XAC (●). The K1 values determined were 5.23 ± 1.46, 20.0 ± 8.5, and 22.6 ± 7.0 μmοΙ/L, respectively.

The level of A3 receptor binding was much higher than levels of A1 and A2A receptors present in the same membranes. Binding assays at A1 and A2A receptors using single concentrations of radioligand were performed as described.26 At 0.6 nmol/L of [3H]R-N6-phenylisopropyladenosine, specific binding representing 0.059 pmol/mg protein of A1 receptors was detected. At 3 nmol/L of [3H]2-[4-[(2-carboxyethyl) phenyl ] ethyl-amino]-5′-N-ethylcarbamoyladenosine, specific binding representing 0.063 pmol/mg protein of A2A receptors was detected.

Cytosolic Ca2+ concentration

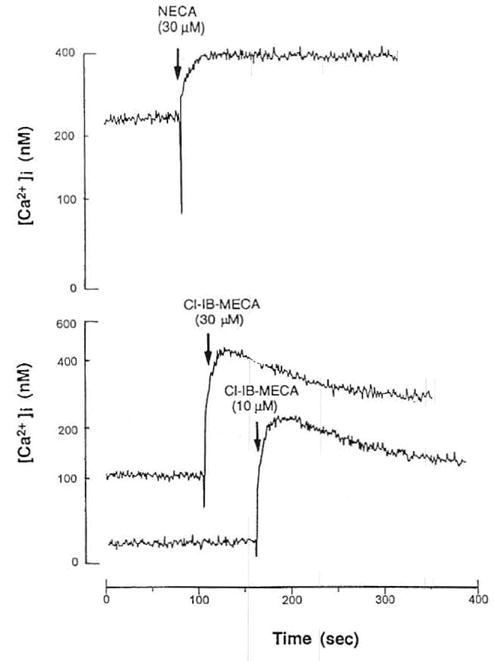

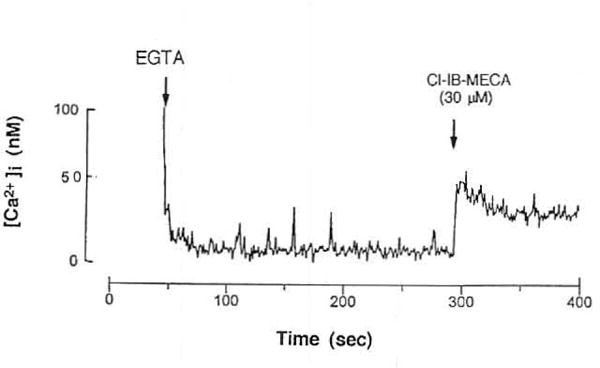

The highly selective A3 receptor agonist, Cl-IB-MECA (10 and 30 μmol/L), produced increases in concentrations of intracellular free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) (Fig 4). It produced a rapid rise followed by a sustained increase in [Ca2+]i. Among the donors selected, those with more significant eosinophilia had a more pronounced [Ca2+]i response, consistent with minimally activated (primed) eosinophils compared with normals. In separate experiments these patients showed increased expression of activation markers, including CD69 and CD25, on their peripheral blood eosinophils compared with normal donors (S. Mawhorter, personal communication, March 1996). Chelation of extracellular Ca2+ with EGTA (0.5 mmol/L) did not abolish the initial rise in [Ca2+]i. Thus, the first rapid increase in [Ca2+]i was due to Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ pools, while the second phase appeared to result from an influx of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig 5). Although NECA (10 μmol/L) induced an increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels, the intensity of the elevation of [Ca2+]i was clearly lower than that of Cl-IB-MECA (Fig 3). NECA is not a selective agonist, although it has a relatively high affinity for the A3 receptor. At concentrations of 30 μmοl/L, CPA and CGS 21680, which would be expected to fully activate any A1 or A2A receptors that may be present, had no effect on intracellular Ca2+ levels in eosinophils (data not shown).

Fig 4.

Effect of adenosine A3 agonists on intracellular Ca2+ levels in eosinophils from hypereosinophilia patients. Cells were prelabeled with FIUO-3AM, as described in Materials and Methods. Effects of NECA (30 μmol/L) and Cl-IB-MECA (10, 30 μmol/L).

Fig 5.

Effect of adenosine A3 agonists on intracellular Ca2+ levels in eosinophils from hypereosinophilia patients. Cells were prelabeled with Fluo-3AM, as described in Materials and Methods. Effects of Cl-IB-MECA (30 μmmol/L) in the presence of 0.5 mmol/L EGTA.

DISCUSSION

These results attest to the existence of ADO A3 receptors on eosinophils. Several methods were used to support this conclusion: (1) Saturable and high-affinity binding of [125I]AB-MECA, an A3 receptor agonist, with relative high density was obtained in membranes prepared from the human eosinophils. The Kd values compared favorably with that obtained at cloned human brain A3 receptors expressed in HEK-293 cells26; (2) ADO analogues competed at [125I]AB-MECA binding sites in the eosinophils with a potency series characteristic of an A3 receptor binding site (BWA1433 >XCC ≈XAC); (3) mRNA encoding the A3 receptor could be amplified by RT-PCR from total RNA samples obtained from the eosinophils; (4) Calcium signaling was observed in eosinophils from hypereosinophilia patients in response to an A3 agonist, but not to an A1 or A2A agonist. The A3 receptor agonist-induced effects on [Ca2+]I in eosinophils are very similar in intensity and pharmacology to those observed in HL-60 cells, for which we have also proposed a functional A3 receptor.29

The role of the ADO A3 receptor on the eosinophils is unclear at present. However, when the eosinophils were exposed to a relatively high concentration of an A3 agonist, synthesized in our laboratory,27 that is ≈2,000-fold selective in binding assays at rat adenosine receptors, an increase in [Ca2+]i was observed. Upon chelation of extracellular Ca2+, the initial rapid rise in [Ca2+]i produced by Cl-IB-MECA was still present, and the later prolonged elevation was absent. These results are consistent with the presence of phospholipase C-coupled ADO A3 receptors on eosinophils. In a previous study of the effects of A3 receptor agonists on HL-60 (human promyelocytic leukemia) cells, very similar effects on [Ca2+]i were seen.29 The calcium ionophore A23187 stimulates these cells to induce the release of granule substances and intact granules by a cytolytic mechanism.30 Some substances are known to stimulate eosinophil function, associated with mobilization of Ca2+ from intracellular stores and secretion of granule substances. Prostaglandin D231 and PAF32,33 one the most potent chemoattractants for eosinophils, are potent stimuli for calcium mobilization. Secretion and other functions induced by these substances appear to depend on both the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores and on G proteins.32,33 Therefore, it is thought that ADO stimulates these cells via the activation of A3 receptors, resulting in the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. It is well-documented that in certain types of cells elevation of the intracellular Ca2+ level induced by various agents can play a crucial role in triggering apoptosis. Also in thymocytes, an antibody against the CD3-T cell receptor complex,34 ATP35 and ADO36 were reported to induce apoptosis by Ca2+-mediated mechanisms, and their effects are mimicked by treatment of the thymocytes with a calcium ionophore. In addition to thymocytes, ADO induced apoptosis in chick embryonic sympathetic neurons.37 Thus, there may be a close relationship between apoptosis and activation of ADO A3 receptor.29

Recent studies have identified a novel ADO receptor sub-type, A3, in the rat18 and similar receptors have been cloned from both human24 and sheep brain cDNA libraries.38 Few physiological functions of ADO A3 receptor are known.28 We proved that A3 receptors are present on eosinophils, and our data are consistent with the possibility that the A3 receptors on the cells are involved in the etiology of various allergic diseases although the possibility that other adenosine receptors or other cells may be involved in these diseases has not been ruled out.

New selective A3 receptor antagonists are currently under development in our laboratory.26 It will be of great interest to determine if a potent antagonist would prevent the elevation of intracellular calcium concentration evoked by an A3 receptor agonist and the activation or apoptosis of the cells. It will be necessary to follow this study with an investigation on how A3 receptor activation affects eosinophil function. A3 receptor antagonists may prove to inhibit infiltration or transmigration of eosinophils to tissues including airway lumen and thus be useful therapeutically in allergic diseases.39

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Bruce S. Bochner (Johns Hopkins Asthma and Allergy Center, Baltimore, MD) for the gift of eosinophils and for helpful discussions and Dr Mark E. Olah and Prof Gary L. Stiles (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC) for preparation of [125I]AB-MECA used in this study.

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

References

- 1.Gleich GJ. The eosinophil and bronchial asthma: Current understanding. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1990;85:422. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(90)90151-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weller PF. The immunobiology of eosinophils. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104183241607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silberstein DS. Eosinophil function in health and disease. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1995;19:47. doi: 10.1016/1040-8428(94)00127-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Discombe G. Criteria of eosinophilia. Lancet. 1946;1:195. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(46)91306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horn BR, Robin ED, Theodore J, VanKessel A. Total eosinophil counts in the management of bronchial asthma. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:1152. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197505292922204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bousquet J, Chanez P, Lacoste JY, Barneon G, Ghavanian N, Enander I, Venhe P, Ahlstedt S, Simony-Lafontainc J, Godard P. Eosinophilic inflammation in asthma. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1033. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199010113231505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filley WV, Holley KE, Kephart GM, Gleich GJ. Identification by immunofluorescence of eosinophil granule major basic protein in lung tissue of patients with bronchial asthma. Lancet. 1982;2:11. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)91152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukuda T, Dunnette SL, Reed CE, Ackerman SJ, Peters MS, Gleich GJ. Increased numbers of hypodense eosinophils in the blood of patients with bronchial asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;132:981. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.132.5.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koshino T, Morita Y, Ito K, Teshima S, Sano Y. Activation of bone marrow eosinophils in asthma. Chest. 1993;103:1931. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.6.1931b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Donnell MC, Ackerman SJ, Gleich GJ, Thomas LL. Activation of basophil and mast cell histamine release by eosinophil granule major basic protein. J Exp Med. 1983;157:1981. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.6.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Church MK, Holgate ST. Adenosine-induced bronchoconstriction and its inhibition by nedocromil sodium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;92:190. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(93)90105-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ott I, Lohse MJ, Klotz KN, Vogt-Moykopf I, Schwabe U. Effect of adenosine on histamine release from human lung fragments. Int Arch Allergy Clin Immunol. 98(50):1992. doi: 10.1159/000236163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bjorck T, Gustafsson LE, Dahlen SE. Isolated bronchi from asthmatics are hyperresponsive to adenosine, which apparently acts indirectly by liberation of leukotrienes and histamine. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:1087. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.5.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Driver AG, Kukoly CA, Ali S, Mustafa SJ. Adenosine in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:91. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weller PF, Lee CW, Foster DW, Corey EJ, Austen KF, Lewis RA. Generation and metabolism of 5-lipoxygenase pathway leukotrienes by human eosinophils: Predominant production of leukotriene C4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:7626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.24.7626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis RA, Austen KF. The biologically active leukotrienes: Biosynthesis, metabolism, receptors, and pharmacology. J Clin Invest. 1984;73:889. doi: 10.1172/JCI111312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howell RE, Gaudette RF, Raynor MC, Warner AT, Muehsam WT, Sehenden JA, Perumattam J, Hiner RN. Mechanisms of xanthine actions in models of asthma. In: Jacobsen KA, Daly JW, Manganiello V, editors. Purines in Cellular Signaling: Targets for New Drugs. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1990. p. 370. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou QY, Li CY, Olah ME, Johnson RA, Stiles GL, Civelli O. Molecular cloning and characterization of an adenosine receptor: The A3 adenosine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyerhof W, Muller-Brechlin R, Richter D. Molecular cloning of a novel putative G-protein coupled receptor expressed during rat spermiogenesis. FEBS Lett. 1991;284:155. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80674-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bai TR, Weir T, Walker B, Salvatore CA, Johnson RG, Jacobson MA. Localization of adenosine-A3 receptors by in-situ hybridization in human lung. FASEB J. 1994;8:A800. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansel TT, Pound JD, Pilling D, Kitas GD, Salmon M, Gentle TA, Lee SS, Thompson RA. Purification of human eosinophils by negative selection using immunomagnetic beads. J Immunol Methods. 1989;122:97. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sajjadi FG, Firestein GS. cDNA cloning and sequence of the human A3 adenosine receptor. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1993;1179:105. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salvatore CA, Jacobson MA, Taylor HE, Linden J, Johnson RG. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human A3 adenosine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olah ME, Gallo-Rodrigucz C, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. [l25I] AB-MECA, a high affinity radioligand for the rat A3 adenosine receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:978. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim HO, Ji X-D, Siddiqi SM, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. 2-Substitution of N6-benzyladenosine-5-uronamides enhances selectivity for A3-adenosine receptors. J Med Chem. 1994;37:3614. doi: 10.1021/jm00047a018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ji X-D, Melman N, Jacobson KA. Interactions of flavonoids and other phytochemicals with adenosine receptors. J Med Chem. 1996;39:781. doi: 10.1021/jm950661k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobson KA, Kim HO, Siddiqi SM, Olah ME, Stiles GL, von Lubitz DKJE. A3-adenosine receptors: Design of selective ligands and therapeutic prospects. Drugs Future. 1995;20:689. doi: 10.1358/dof.1995.020.07.531583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohno Y, Sei Y, Koshiba M, Kim HO, Jacobson KA. Induction of apoptosis in HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells by selective adenosine A3 receptor agonists. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1996;219:904. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fukuda T, Ackerman SJ, Reed CE, Peters MS, Dunnette SL, Gleich GJ. Calcium ionophore A23187 calcium-dependent cytolytic degranulation in human eosinophils. J Immunol. 1985;135:1349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raible DG, Schulman ES, DiMuzio J, Cardillo R, Post TJ. Mast cell mediators prostaglandin-D2 and histamine activate human eosinophils. J Immunol. 1992;148:3536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cromwell O, Bennett JP, Hide I, Kay AB, Gomperts BD. Mechanism of granule enzyme secretion from permeabilized guinea pig eosinophils: Dependence on Ca2+ and guanine nucleotides. J Immunol. 1991;147:1905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kroegel C, Chilvers ER, Giembycz MA, Challiss RA, Barnes PJ. Platelet activating factor stimulates a rapid accumulation of inositol [1,4,5] triphosphate in guinea-pig eosinophils; relationship to calcium mobilization and degranulation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;88:114. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(91)90308-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McConkey DJ, Hartzell P, Amador-Perez JF, Orrenius S, Jondal M. Calcium-dependent killing of immature thymocytes by stimulation via the CD3/T cell receptor complex. J Immunol. 1989;143:1801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pizzo P, Zanovello P, Bronte V, Di Virgilio F. Extracellular ATP causes lysis of mouse thymocytes and activates a plasma membrane ion channel. Biochem J. 1991;274:139. doi: 10.1042/bj2740139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szondy Z. Adenosine stimulates DNA fragmentation in human thymocytes by Ca2+-mediated mechanisms. Biochem J. 1994;304:877. doi: 10.1042/bj3040877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wakade TD, Palmer KC, McCauley R, Przywara DA, Wakade AR. Adenosine-induced apoptosis in chick embryonic sympathetic neurons: A new physiological role for adenosine. J Physiol. 1995;488:123. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Linden J, Taylor HE, Robeva AS, Tucker AL, Stehle J, Rivkes SA, Fink JS, Reppert SM. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a sheep A3 adenosine receptor with widespread tissue distribution. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;44:524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beaven MA, Ramkumar V, Ali H. Adenosine-A(3) receptors in mast-cells. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1994;15:13. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]