Abstract

Parents interact with their environment in important ways that may impact their ability to parent their children positively. The current study uses data from the age 3 wave of the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing study to investigate whether neighborhood processes and community participation relate to internal control, and whether these three variables are associated with child maltreatment behaviors. Using structural equation modeling, the direct and indirect effects of the environment (neighborhood disorder, social control, and social cohesion) and community participation on child maltreatment are tested. The mediating variable tested is internal control. The results show that neighborhood processes and community participation are associated with child neglect, physical child abuse, and psychological aggression but that these associations are driven through their effect on internal control.

Keywords: Neighborhood, Child Maltreatment, Community Participation

Introduction

Child maltreatment remains a significant problem in the United States, with over 6 million children being the subject of a child maltreatment report in federal fiscal year 2013 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015). Children experiencing child abuse and neglect are more likely to experience a host of negative outcomes including mental health complications, drug and alcohol misuse, obesity, and criminal behavior (Gilbert, Widom, Browne, Fergusson, Webb, & Janson, 2009). The experience of living in poverty and in violent neighborhoods may inhibit a parent’s ability to care for and discipline their children affected by their environment. As such, it is essential to investigate the protective mechanisms that can be enhanced to support parents and prevent maltreatment. Parents who have positive and supportive relationships with their neighbors may be able to rely on their neighbors to assist with child rearing duties, obtain parenting advice, and help with emergency child care and basic needs. Parents who actively participate in their neighborhoods may also experience lower risk for maltreating their children due to a myriad of factors, including feeling more empowered, enjoying a higher level of social connections, and being less socially isolated.

Literature Review

Theoretical framework

Child maltreatment researchers have focused on the etiology of abuse and neglect since the seminal article on battered child syndrome from Kempe and colleagues (1962). While the vast majority of the early work in this area focused on individual characteristics of parents, with the application of the ecological model to child maltreatment (Belsky, 1980; Bronfenbrenner, 1979), neighborhoods and the interactions therein have become an increasing point of focus (see Coulton, Crampton, Irwin, Spilsbury, & Korbin, 2007; Freisthler, Merritt, & LaScala, 2006; and Maguire-Jack, 2014 for reviews).

We rely on social disorganization theory to provide a framework for understanding the ways in which certain neighborhood processes and parents’ interactions with their environment might impact a parent’s ability to care for their child. Social disorganization theory (Shaw & McKay, 1942) stipulates that neighborhoods that are characterized by layers of disadvantage related to poverty, unemployment, and population turnover can affect the residents in multiple ways that are harmful. While the original intent of the theory was related to juvenile crime, this theory has been expanded by child maltreatment researchers in proposition that these same negative characteristics of disorganized neighborhoods may also contribute to child abuse and neglect (Ben-Arieh, 2010; Coulton, Korbin, & Su, 1999; Freisthler, 2004; Freisthler, Gruenewald, Remer, Lery, & Needell, 2007; Freisthler, Gruenewald, Ring, & LaScala, 2008; Garbarino & Kostelny, 1992; Korbin, Coulton, Chard, Platt-Houston, & Su, 1998). According to the theory, neighborhoods are “disorganized” when they lack a structure to help maintain social controls that allow their residents to realize shared values (Sampson & Groves, 1989).

In addition to the structural characteristics (e.g. poverty) of neighborhoods, examining the interactions between people and their families and communities is essential for understanding the ways in which communities matter for various social problems (Ungar, Ghazinour, & Richter, 2013). Extensions of social disorganization theory suggest that shared principles and community expectations are required to organize against deviant behaviors within the community. These neighborhood processes are referred to as “collective efficacy,” which is composed of social cohesion and social control (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997). Neighborhood social cohesion refers to common bonds, trust, and feelings of support between neighbors, while neighborhood social control refers to the norms of a community and the willingness to intervene when such norms are being violated. Social cohesion may be protective against child maltreatment because parents living in neighborhoods with high levels of social cohesion have an array of supportive individuals on whom they can rely to meet their needs as well as the needs of their children. Social control, on the other hand, may prevent child maltreatment because of a collective agreement about appropriate treatment of children and for fear of retaliation against a parent who acts outside of those norms.

In another extension of the theory, it is postulated that community members can establish agreement around common values by interacting with the institutions within their community. Participating in local events and organizations may help empower residents to act on their personal goals and their goals for their communities (Sampson, 2001). Further, Sampson and Groves (1989) identify limited participation in local organizations as one of three primary pathways by which neighborhood social disorganization affects residents’ outcomes.

Neighborhood processes and child maltreatment

In a literature review of the community context of child maltreatment, Coulton and colleagues (2007) argued that there was a lack of understanding about the potentially important role of neighborhood processes in child abuse and neglect. This assertion has led to a proliferation of studies on collective efficacy and child maltreatment. A number of studies have found protective effects of collective efficacy. Guterman and colleagues (2009) found that more negative perceptions of collective efficacy and social disorder were associated with higher levels of psychological aggression and physical assault. Several studies have found that a higher rate of neighborhood social cohesion is related to lower rates of child neglect (Maguire-Jack & Wang, 2016; Maguire-Jack & Showalter, 2016) and that a higher level of collective efficacy is associated with lower rates of abuse (Freisthler & Maguire-Jack, 2015) and neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse (Molnar et al., 2016). In related work, Fujiwara, Yamaoka, & Kawachi (2016)) found that residents of neighborhoods with higher rates of maltreatment reported that their neighbors were less likely to assist with childcare, had more negative comments about their neighborhood, had higher levels of stress, and were less likely to engage in neighborhood exchanges compared to residents in neighborhoods with lower rates of maltreatment. Similarly, Vinson, Baldry, and Hargreaves (1996) found that a greater number of interactions with neighbors and acquaintances were associated with lower child abuse rates. It should also be noted that a handful of studies examining these processes have not found evidence of a relationship with maltreatment (Molnar et al., 2003; Coulton, Korbin, & Su, 1999; Deccio et al., 1994).

These social processes are closely aligned with a similar construct of social capital. Social capital relates to the resources that individuals are able to obtain from their various social settings, including communities (Fujiwara, Kubzansky, Matsumoto, & Kawachi, 2012). Studies of social capital have found similar protective mechanisms against maltreatment (Fujiwara, Yamaoka, & Kawachi, 2016).

Community participation and child maltreatment

In addition to the interactions and relationships between neighbors, there may be an additional protective role of participating in various organizations within a community. Participating in community events may provide additional opportunities for making connections with neighbors, thus building social networks, providing the opportunity for parents to be exposed to additional parenting support and knowledge as well as increasing the exposure to other adults, which can form an additional layer of social control. Further, there may be inherent value in participating in events and organizations through increased feelings of internal control and empowerment. Kim and Maguire-Jack (2015) examined neighborhood collective efficacy as well as a mother’s participation in her community, and found that a mother’s involvement in her community was associated with lower levels of psychological aggression and that increased community-level social control was associated with lower levels of physical assault. Additionally, Gracia & Musitu (2003) examined the role of participation in community institutions cross-culturally, and found that although community participation varied between Spanish and Colombian cultures, within both cultures, parents who were abusive had lower levels of community participation. These findings suggest that exposure to other adults’ monitoring over parental behaviors could help prevent child maltreatment.

In a related study, Ellis and colleagues (2015) examined the unique role of sense of belonging in the relationship between social cohesion and violence perpetration and found that even when social cohesion was low, violence was lessened when a sense of belonging was higher. To the extent that community participation relates to a sense of belonging, we expect that community participation may have a protective role in maltreatment.

Internal control and child maltreatment

“Internal control” comes from the psychology concept of “locus of control.” In the locus of control, internal control refers to the extent to which an individual feels in control of his or her behavior or the things that happen to the individual (Wiehe, 1987). “External control” refers to the extent to which the individual feels that their behavior or the events they experience are due to chance, luck, or other individuals (Wiehe, 1987). Prior studies have found that individuals who act aggressively tend to have an external locus of control, rather than an internal locus (Beck & Ollendick, 1976; Duke & Fenhagen, 1975). In terms of child maltreatment, we might expect that parents who engage in abuse and neglect may also have a weaker internal locus of control. An early descriptive study compared 32 abusive mothers to 32 non-abusive mothers and found that those who engaged in child abuse were more likely to have an external locus of control (Wiehe, 1987). Additionally, in a study of social disorder and collective efficacy, Guterman et al. (2009) found a mild direct role of these neighborhood processes on physical abuse, and a more noticeable indirect effect on physical abuse and neglect through their effect on parenting stress and internal control. More negative perceptions of social disorder and collective efficacy were related to lower levels of internal control and higher levels of parenting stress, which were both positively related to psychological aggression and physical abuse (Guterman et al., 2009).

Current study

Two prior studies specifically motivated this work. First, the study referenced above by Guterman and colleagues (2009) examined the relationship between neighborhood disorder, social cohesion, and social control, and child maltreatment, while also considering the mediating role of internal control and parental stress. The study found that internal control played an important role in understanding the connection between these neighborhood processes and child maltreatment (Guterman et al., 2009). Second, the study referenced above by Kim and Maguire-Jack (2015) extended the work of Guterman and colleagues (2009) by examining neighborhood processes, community participation, and child maltreatment. Together, these studies suggest an important role of both neighborhood processes as well as participation in community events and organizations in the prevention of child maltreatment. However, an important gap remains between the two studies. Specifically, while Guterman and colleagues (2009) did not consider the role of community participation, Kim and Maguire-Jack (2015) did not consider the potential mediating role of internal control. The current study builds directly on these two studies by considering neighborhood processes as well as community participation; therefore it considers the role of interacting informally with neighbors as well as the more formal interactions with events and organizations within the community. Further, this study also considers the mediating role of internal control to better estimate direct and indirect effects of the neighborhood process and participation variables.

We hypothesize that a mother’s participation in community events will be predictive of higher levels of internal control and lower levels of child maltreatment behaviors. Further, we hypothesize that a mother’s worse perception of her neighborhood will be associated with higher rates of participation in communities, and be predictive of higher levels of internal control and lower levels of child maltreatment.

Methods

Data

The data are drawn from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS), a longitudinal birth cohort study of newly unwed parents and the well-being of their children. A stratified random sample of all U.S. cities with 200,000 or more people was used to achieve maximum variation in policy environments and labor market conditions across cities. A comparison sample of children born to married parents was also included. The original birth cohort followed 4,898 children born in the US between 1998 and 2000 in 75 hospitals, among whom 3,712 were born to unmarried mothers and 1,186 to married mothers (Reichman, Teitler, Garfinkel, & McLanahan, 2001). The core component of the study consists of interviews with both mothers and fathers at the child’s birth and again when children reach 1, 3, 5, and 9 years of age. Core interviews included information on attitudes, relationships, parenting behavior, demographic characteristics, health (mental and physical), economic and employment status, neighborhood characteristics, and program participation. At ages 3, 5, and 9 years, in-home assessments of children’s cognitive and emotional development, health, parent’s maltreatment behavior, and home environment were conducted (Reichman, Teitler, Garfinkel, & McLanahan, 2001).

The current study uses information from the 3-year FFCWS core and in-home interviews. This subset of data contains the most complete data on the variables for the research question of interest. In total, we had 3,288 participants in the sample.

Measures

Child Maltreatment Risk

Mothers reported their acts of neglect and psychological and physical aggression from the Conflict Tactics Scale: Parent-Child Version (CTS-PC), which serves as a self-report measure of child maltreatment behaviors (Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998). The FFCWS includes five items to measure physical aggression, five items to measure psychological aggression, and five items to measure neglect. Eight questions of severe physical maltreatment (e.g. “grabbing a child around the neck and choking him/her,” “burning or scaling a child on purpose,” “threatening a child with a knife or gun”) from the original scale are excluded. The 5-item subscale of physical aggression includes shaking; hitting the child on the bottom with some hard object (belt, hairbrush, stick); pinching; spanking the child on the bottom with your bare hand; and slapping the child on the hand, arm, or leg. The 5-item subscale of psychological aggression includes shouting/yelling/screaming at the child, swearing/cursing, threatening to spank or hit but not actually doing it, saying you would send child away or would kick the child out of the house, and calling the child dumb or lazy or some other name like that. The 5-item subscale of neglect includes leaving the child home alone but thinking some adult should be with him/her, being so caught up with your own problem that you were not able to show love to the child, being unable to make sure the child got the food he/she needed, being unable to make sure the child got to a doctor or hospital when needed, and being so drunk/high that you had a problem taking care of the child. The mother was asked to report how many times she had done the behavior in the past year on a 7-point ordinal scale. All three scales were originally coded ordinal, with “0” as never happened, “1” as once, “2” as twice, “3” as 3–5 times, “4” as 6–10 times, “5” as 11–20 times, and “6” as more than 20 times. “7” as yes, but not in past year in the original scale was recoded as “1” as once for the clarity of analysis and interpretation. Each item was recoded with a mid-point value (e.g. 4 for “2–5”), and “more than 20 times” was recoded as 25, following Straus’s (1998) guideline to reflect the frequency of the behavior.

Principal component factor analysis validated three child maltreatment variables, showing psychological aggression (eigenvalue = 1.8, 36.2% variance explained, Cronbach’s alpha = .52), physical aggression (eigenvalue = 2.0, 39.2% variance explained, Cronbach’s alpha = .61), and neglect (eigenvalue = 2.0, 40.5% variance explained, Cronbach’s alpha = .54). All factor loadings are .4 or above, with only one exception of shaking the child for physical aggression (factor loading = 0.22). Thus, we dropped that item for the physical aggression scale, and re-ran the analysis, generating eigenvalue at 1.9, 48.4% variance explained, not suggesting substantial improvement for the results. Therefore, we decided to still include the item of shaking the child.

Perceived Neighborhood Processes

Mother’s report of neighborhood processes were measured by a latent variable comprised of social disorder, informal social control and social cohesion.

Social disorder

Social disorder was measured with eight items indicating how often parents assessed the following occurrences taking place in their neighborhood ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (frequently), including drug dealers or users hanging around, drunks hanging around, unemployed adults loitering, adults loitering, gang activity occurring, misbehaving groups of young children, disorderly/misbehaving groups of teens, and disorderly/misbehaving groups of adults (Coulton, Korbin, & Su, 1999). Principal components factor analysis indicated that these eight items formed a single factor, eigenvalue = 5.4 with 67.9 % of variance explained. Higher scores indicate a greater sense of perceived social disorder. Cronbach’s alpha of those eight items was .93.

Informal social control

Informal social control was measured using five items that asked respondents how likely they thought it was that their neighbors would intervene in a series of situations, including children skipping school and hanging out at street corner, children spray-painting graffiti on local building, children showing disrespect to an adult, a fight breaking out in front of their house, and nearby fire station being threatened with budget cuts, with 1 (very likely) to 5 (very unlikely) (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997). These items were scored so that higher scores indicated lower levels of informal social control. Factor analysis yielded an eigenvalue of 3.3 with 66.9 % of the variance explained. Cronbach’s alpha of these five items was .88.

Social Cohesion

Social cohesion was measured using five items indicating respondents’ agreement with the following statements, including “people around here are willing to help their neighbors,” “this is a close-knit neighborhood,” “people in this neighborhood can be trusted,” “people in this neighborhood generally don’t get along with each other,” and “people in this neighborhood do not share the same values” with responses ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997). Two items, “people in this neighborhood generally don’t get along with each other” and “people in this neighborhood do not share the same values,” were reverse coded, such that higher scores indicate a lower sense of social cohesion. Factor analysis yielded an eigenvalue of 2.8 with 55.7 % of the variance explained. Cronbach’s alpha of these five items was .8. Cronbach’s alpha values for all three variables are above .7, with factor loadings ranging from .6 to .9.

Internal control

Internal control was measured using five items, including “I have little control over the things that happen to me,” “there is really no way I can solve some of the problems I have,” “there is little I can do to change many of important things in my life,” “I often feel helpless in dealing with problems,” and “sometimes I feel that I am being pushed around” with responses ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree) (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978). Principal component factor analysis yielded an eigenvalue of 2.9 with 57.4 % of the variance explained. Cronbach’s alpha was .8. Higher scores indicated greater sense of internal control. All factor loadings are above .6.

Community Participation

Community Participation was categorized with six items, indicating mothers’ involvement in the following events, including “group affiliated with your church”; “a service club”; “political, civic, or human rights group”; “labor union or work-related group”; “community organization”; and “group working with children.” Respondents provided answers (1=yes or 0=no) to the above-mentioned questions. We summed up the frequency of respondents’ participation in these community events. The degree of a respondent’s community participation was measured as none (0), some (1), and high (2–6), as applied in prior work (Kim & Maguire-Jack, 2015).

Control variables

We include a number of mothers’ demographic characteristics that prior studies have found to be related to the occurrence of child maltreatment measured by the CTS-PC scale (Guterman et al., 2009; Kim and Maguire-Jack, 2015). Marital status is measured using a binary variable of married or cohabiting/other, with “1” indicating married and “0” indicating cohabiting or other relationship states. Race/Ethnicity statuses in the analysis include African American/Non-Hispanic, White/Non-Hispanic, Hispanic, and other. All four categories were included as dummy variables in the overall model. Maternal age is based on mothers’ self-reported age when the child was 3 years old. Household income is also based on mothers’ self-reported household income when the child was 3 years old with imputed data. Household income was log-transformed to account for the non-normal distribution. Education is also controlled in the model (less than high school, high school or equivalent, some college, or college/graduate school).

Data Analytical Plan

Descriptive analyses were performed using STATA release 12.0 (StataCorp, 2011), and structural equation models were estimated using SAS system’s CALIS procedures release 9.4 (SAS, 2013). Each type of maltreatment was modeled separately. We used a two-step approach, as recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (1988). First, we developed a measurement model using confirmatory factor analysis to examine the model fit to the data. Then, we tested the hypothesized structure model based on prior literature on similar topics. Several goodness-of-fit statistics were used to examine the fit of the model to the data, including the Goodness-of-Fit statistic index (GFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and non-normed-fit index (NNFI). For the GFI and NNFI, values should exceed .9 to show an appropriate fit; the closer to 1.00, the better. For the RMSEA, values close to .04 and lower are evidence of an appropriate fit (Hatcher, 1994; Schumacker & Lomax, 2012).

Results

Descriptives

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics for the sample in this study. The average age of mothers in our sample was about 28 years. Additionally, 31% of the sample was married, 22% was white, 49% were African American, 26% were Hispanic, and 39% had less than a high school education. In terms of the key independent variables, the average level of social disorder was 1.8 on a scale from 1–4, thus indicating a relatively low level of disorder. Social cohesion and social control were 2.53 and 2.38 on average, respectively. Both of these scales ranged from 1–5, thus indicating a moderate amount of control and cohesion. Finally, internal control was 3.39 on average, on a scale from 1–4, thus indicating a very high level of internal control across the sample. In terms of the dependent variables, the average level of psychological aggression was 4.89, indicating that mothers reported verbal abuse about 5 times in the past year. The average level of physical abuse was 3.12, indicating mothers reported physically abusing the focal child about 3 times in the past year. The average level of neglect was much lower, 0.14, indicating that mothers reported neglecting their child very infrequently (less than one time in the past year).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Mothers in the Study Sample (N=3,288)

| Study Variables | % or mean (SD) | Range | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age at child’s birth | 28.09 (6.05) | 16–50 | 3,287 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 31.4 % | 3,284 | |

| Cohabiting/other | 68.6 % | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 21.8 % | 3,279 | |

| African American | 48.9 % | ||

| Hispanic | 25.8 % | ||

| Other | 3.5 % | ||

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 39.1 % | 3,284 | |

| High school or equivalent | 25.3 % | ||

| Some college or technical | 24.9 % | ||

| College or graduate | 10.7 % | ||

| Ln(Income) ($) | 9.92 (1.14) | 1.1 – 13.82 | 3,267 |

| Community Participation (CP)a | .92 (1.19) | 0 – 3 | 3,287 |

| Social Disorderb | 1.80 (.88) | 1 – 4 | 3,203 |

| Social Cohesionc | 2.53 (.99) | 1 – 5 | 3,228 |

| Informal Social Controld | 2.38 (1.23) | 1 – 5 | 3,224 |

| Internal Controle | 3.39 (.63) | 1 – 4 | 3,248 |

| Child Maltreatment Outcomes | |||

| Psychological Aggression | 4.89(4.04) | 0 – 25 | 3,253 |

| Physical Abuse | 3.12(3.68) | 0 – 20.8 | 3,253 |

| Neglect | .14(.87) | 0 – 25 | 3,250 |

Higher scores indicate higher levels of community participation.

Higher scores indicate higher levels of perceived social disorder

Higher scores indicate lower levels of perceived social cohesion

Higher scores indicate lower levels of perceived informal social control

Higher scores indicate higher levels of internal control

Following the two-step approach recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (1998), we first fitted the measurement model and then the structural model. In addition, given that this relationship has not been tested before, we randomly split the sample into halves, a developmental sample and a confirmatory sample. The developmental sample was used to initially test and adjust measurement and structural models. The structural model was finally tested using the confirmatory sample. The large sample size of the Fragile Families dataset also allows us to develop and test models using two randomly split samples, and thus validate our results. We present model fit statistics using both developmental and confirmatory samples in Table 2. We then present descriptive statistics of the confirmatory sample in Table 3, and also present results of the structural model only using the confirmatory sample in Table 4.

Table 2.

Measurement and Structural Model Fit Statistics

| X2 | d.f. | n | GFI | SRMR | BNNI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement model using developmental sample (n=1,644) | ||||||

| Psychological Aggression | 523.62 | 152 | 1596 | .97 | .03 | .96 |

| Physical Abuse | 443.37 | 152 | 1596 | .97 | .03 | .97 |

| Neglect | 356.6 | 152 | 1596 | .98 | .03 | .98 |

| Structural model using developmental sample (n=1,644) | ||||||

| Psychological Aggression | 610.55 | 157 | 1596 | .97 | .04 | .95 |

| Physical Abuse | 530.14 | 157 | 1596 | .97 | .03 | .96 |

| Neglect | 443.59 | 157 | 1596 | .97 | .03 | .97 |

| Structural model using confirmatory sample (n=1,644) | ||||||

| Psychological Aggression | 739.99 | 157 | 1602 | .96 | .04 | .94 |

| Physical Abuse | 493.08 | 157 | 1602 | .97 | .03 | .96 |

| Neglect | 431.52 | 157 | 1602 | .98 | .03 | .97 |

Table 3.

Characteristics of Mothers in the Confirmatory Sample (n=1,644)

| Study Variables | % or mean (SD) | Range | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age at child’s birth | 28 (5.95) | 16–46 | 1,644 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 30.33 % | 1,642 | |

| Cohabiting/other | 69.67 % | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 20.88 % | 1,638 | |

| African American | 50.12 % | ||

| Hispanic | 25.89 % | ||

| Other | 3.11% | ||

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 40.44 % | 1,642 | |

| High school or equivalent | 25.88 % | ||

| Some college or technical | 23.75 % | ||

| College or graduate | 9.93 % | ||

| Ln(Income) ($) | 9.9 (1.15) | 1.94 – 13.49 | 1,631 |

| Community Participation (CP)a | .89 (1.17) | 0 – 3 | 1,644 |

| Social Disorderb | 1.8 (.9) | 1 – 4 | 1,602 |

| Social Cohesionc | 2.51 (.99) | 1 – 5 | 1,615 |

| Informal Social Controld | 2.39 (1.24) | 1 – 5 | 1,613 |

| Internal Controle | 3.39 (.63) | 1 – 4 | 1,624 |

| Child Maltreatment Outcomes | |||

| Psychological Aggression | 4.9 (4.02) | 0 – 25 | 1,626 |

| Physical Abuse | 3.24(3.79) | 0 – 18.2 | 1,626 |

| Neglect | .14(.86) | 0 – 25 | 1,625 |

Table 4.

Results of Structural Model Using Confirmatory Sample (n=1,644)

| Paths | Psychological Aggression β (SE) |

Physical Abuse β (SE) |

Neglect β (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | |||

| Income – CM | .14 (.04)*** | .13(.03)*** | .01(.03) |

| Age – CM | −.12 (.03)*** | −.17(.03)*** | .05(.03) |

| Education – CM | .06 (.04) | .01(.03) | .07(.19) |

| Marriage Status - CM | −.03 (.03) | .02(.03) | .04(.03) |

| White - CM | −.19(.20) | .13(.19) | .03(.18) |

| Black - CM | −.18 (.24) | .26(.23) | .08(.22) |

| Hispanic - CM | −.37 (.21) | −.03(.20) | .07(.19) |

| Other - CM | −.13 (.10) | .03(.10) | .01(.09) |

| Community Participation – Internal Control | .08 (.03)** | .08(.03)** | .08(.03)** |

| Neighborhood Process – Internal Control | −.32 (.03)*** | −.32(.03)*** | −.31(.03)*** |

| Internal Control – CM | −.14 (.04)*** | −.09(.03)** | −.09(.03)** |

| Community Participation – CM | −.03 (.03) | −.01(.03) | −.03(.03) |

| Neighborhood Process – CM | .21 (.04)*** | .12(.04)** | −.01 (.04) |

| Indirect Effect | |||

| Community Participation – Internal Control - CM | −.01(.01)* | −.01(.01)* | −.01(.01)* |

| Neighborhood Process – Internal Control - CM | .05(.01)*** | .03(.01)** | .03(.01)** |

| R-square | 29% | 21.04% | 15.64% |

Note: Standardized estimates;

p <.05,

p < .01,

P<.001

Measurement Model

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to determine the appropriate factor structure of the hypothesized model. We tested the measurement model for physical abuse, psychological aggression, and neglect respectively. Results indicate a good fit of all the models to data. Using the developmental sample, the model fit for the psychological aggression model is X2 (152) =523.62, GFI =.97, SRMR =.03, BNNI = .96; X2 (152) =443.37, GFI = .97, SRMR = .03, BNNI = .97 for physical abuse; X2 (152) =356.6, GFI = .98, SRMR = .03, BNNI = .98 for neglect.

Structural Model

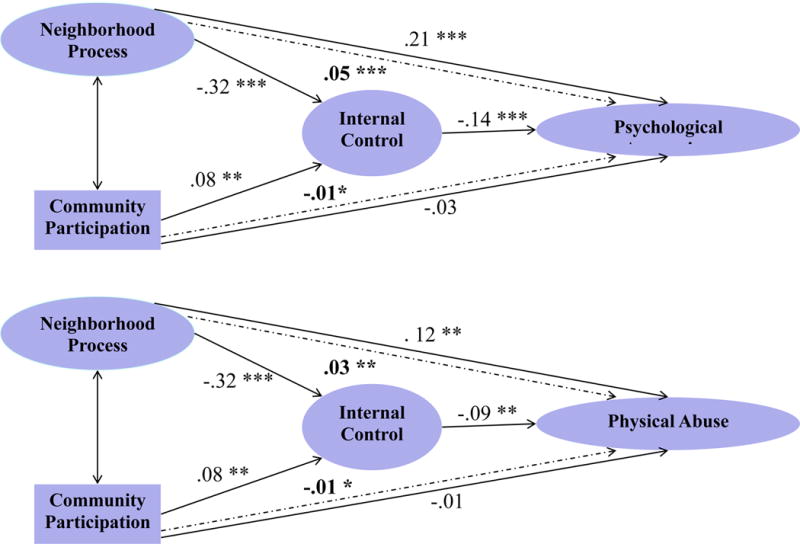

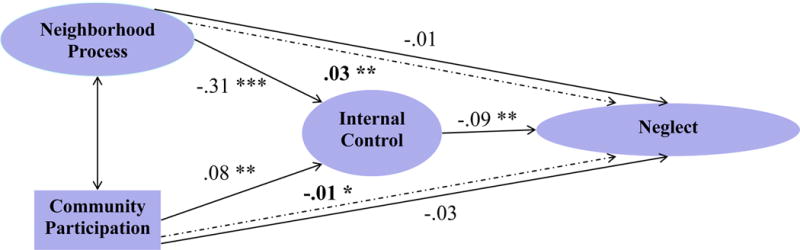

We continued fitting structural models using the developmental sample, and then fitted the model using the confirmatory sample. Results using the developmental sample were similar to results using the confirmatory sample. We presented the results of the structural model using the confirmatory sample in Figure 1. As a reminder, we tested several goodness-of-fit statistics to examine the fit of the model to the data. These included the Goodness-of-Fit statistic index (GFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and Bentler-Bonett Non-normed Index(BNNI). All three models had a good fit of the hypothesized structural model, X2 (157) = 739.99, GFI = .96, SRMR = .04, BNNI = .94 for the psychological aggression model; X2 (157) = 493.08, GFI = .97, SRMR = .03, BNNI = .96 for the physical abuse model; X2 (157)= 431.52, GFI = .98, SRMR = .03, BNNI = .97 for the neglect model.

Figure 1.

Structural model for three types of child maltreatment (n=1644). Notes. Standardized path coefficients are shown, and * p <.05, ** p < .01, *** P<.001. Control variables include race/ethnicity, income, age, education and marital status. The solid line indicates direct effects, and the dotted line suggests indirect effects.

Psychological Aggression Model

As for direct effects, mothers’ perceptions of more negative neighborhood processes were associated with higher levels of psychological aggression behavior (β= .21, SE= .04, p <.001). Mothers’ internal control negatively predicted psychological aggression behavior (β= −.14, SE= .04, p <.001), but the relationship between community participation and psychological aggression risk was not statistically significant. However, mothers’ participation in community activities positively predicted internal control (β= .08, SE= .03, p < .01), while mothers’ perceptions of negative neighborhood processes were negatively predictive of mothers’ internal control (β= −.32, SE= .03, p < .001). Among control variables, results show that the older the mother was, the less likely that she demonstrated psychological aggression (β= −.12, SE= .03, p < .001). However, the higher the mother’s income level was, the more likely the mother showed psychological aggression (β= .14, SE= .04, p < .001). Education level, marital status, and race/ethnicity were not significantly predictive of mothers’ psychological aggression risk. Although the direct pathway from mothers’ community participation to psychological aggression was not significant, a significant indirect effect of internal control was shown between mothers’ community participation and psychological aggression (β= −.01, SE= .01, p < .05). A significant indirect effect of internal control was also found between mothers’ negative perception of neighborhood process and psychological aggression (β= .05, SE= .01, p < .001). This model explained approximately 29% of the variance in mothers’ report of psychological aggression behaviors.

Physical Abuse Model

As for direct effects, the more negatively mothers perceived their neighborhood processes, the more likely that mothers used physical abuse. The predictive relationship was found statistically significant (β= .12, SE= .04, p < .01). Mothers’ participation in community activities did not significantly predict mothers’ physical abuse behaviors. More internal control predicted lower levels of physical abuse, but to a lesser extent compared to psychological behaviors (β= −.09, SE= .03, p < .001). Mothers’ participation in community activities positively predicted internal control (β= .08, SE= .03, p < .01), while mothers’ perception of negative neighborhood processes was negatively predictive of mothers’ internal control (β= −.32, SE= .03, p < .001). Similar to psychological aggression, age negatively predicted mothers’ physical abuse behavior (β= −.17, SE= .03, p < .001), and income level positively predicted physical abuse behavior (β= .13, SE= .03, p < .001). As for indirect effects, similar to psychological aggression, community participation, our primary variable of interest, negatively predicted mothers’ reported physical abuse behaviors via the pathway of internal control (β=-.01, SE= .01, p < .05). The more negatively mothers perceived the neighborhood processes, the more likely they reported physical abuse behaviors via the pathway of internal control (β= .03, SE= .01, p < .01), but the effect of perceived neighborhood process was to a lesser extent compared to that of psychological aggression. This model explained 21.04% of the variation in mothers’ self-reported physical abuse behaviors.

Neglect Model

In terms of direct effects, mothers’ perceptions of negative neighborhood processes and community participation did not significantly predict reported neglect behaviors. However, mothers’ internal control negatively predicted reported neglect behaviors (β= −.09, SE= .03, p < .01). Mothers’ participation in community activities positively predicted internal control (β= .08, SE= .03, p < .01), while mothers’ perceptions of negative neighborhood processes were negatively predictive of mothers’ internal control (β= −.31, SE= .03, p < .001). As for indirect effects, mothers’ participation in community activities and their perceptions of negative neighborhood processes significantly predicted reported neglectful behaviors through the pathway of internal control. Specifically, the more community activities mothers reported to participate in, the less likely mothers showed neglect behaviors via the pathway of internal control (β= -.01, SE= .01, p < .05). Mothers’ perceptions of negative neighborhood processes positively predicted reported neglect behaviors through the pathway of internal control (β= .03, SE= .01, p < .01). This model explained 15.64 % of the variance in mothers’ self-reported neglectful behaviors.

Discussion

This study investigated the role of community participation on mothers’ self-reported child maltreatment behaviors and the mediating role of mothers’ internal control. This study is unique in that it examined the role of community participation and the mediating pathway through internal control, and contributes to the literature on neighborhood and child maltreatment, given the lack of studies exploring neighborhood processes and potential pathways between such factors and child maltreatment. While prior studies have examined the associations between community participation and maltreatment (Gracia & Musitu, 2003; Kim & Maguire-Jack, 2015), the current study was able to examine the effect of community participation, net of the role of other neighborhood processes, and also examined why it matters by also estimating the mediators of this relationship. Our findings are consistent with results from prior research on the direct relationship between neighborhood process and psychological aggression and physical abuse, and also the indirect pathway through internal control, but our findings do not support the direct relationship between negative neighborhood processes and neglect (Guterman et al., 2009). As an extension to Guterman et al.’s work (2009), we tested the role of community participation as a proxy of mothers’ interactions with neighborhood institutions and found that community participation did not directly predict any of three forms of child maltreatment. Our findings differ from results from Kim and Maguire-Jack’s (2015) study that indicates higher levels of community involvement are related to lower rates of psychological aggression. The current study found that community involvement was associated indirectly with all three types of maltreatment, via its influence on internal control, but did not find evidence of a direct effect. There are two important differences between the two studies that may contribute to these differential findings. First, the current study relied on the age 3 wave of FFCWS while the prior study by Kim and Maguire-Jack (2015) relied on the age 5 data. Second, the study by Kim and Maguire-Jack (2015) did not consider the potential mediating pathway or internal control, and therefore may be mis-estimating the impact of community participation on maltreatment.

The findings are also consistent with the findings of Gracia and Musitu (2003), who found that families who were abusive tended to have lower levels of community participation. The protective mechanism of community participation appears to hold across a number of cultures, as the current study was conducted in 20 studies in the United States, and Gracia and Musitu (2003) examined families in Spain and Colombia. In terms of the neighborhood processes, the findings also provide further support for the prior studies that found collective efficacy (and related concepts) to be associated with maltreatment (Fresithler & Maguire-Jack, 2015; Fujiwara et al., 2016; Garbarino & Sherman, 1980; Maguire-Jack & Wang, 2016; Maguire-Jack & Showalter, 2016; Molnar et al., 2016; Vinson et al., 1996).

Our findings have several implications for neighborhood-level prevention efforts aiming to reduce child maltreatment. First, our results show that mothers’ participation in community programs or activities exert positive influence on reducing or preventing mothers’ child maltreating behaviors through enhancing mothers’ internal control. The positive role of internal control in preventing child maltreatment was strongly supported in our study. Enhanced internal control could be one measurable outcome for community programs. Although these programs are not specifically designed to directly cope with child maltreatment, they could potentially improve the overall social environment within a community. When the neighborhood social environment improves, every resident in the neighborhood benefits. It is thus beneficial to invest more in community activities and events targeting families. Efforts to encourage and link at risk families with community activities or events could be helpful to augment their internal control. In addition, our study supports the impact of negative neighborhood processes on the rate of child maltreatment. Child maltreatment prevention efforts at the neighborhood level should consider including efforts to improve community perceptions, which will require improving communities and the connections within. Such strategies include providing opportunities for neighbors to interact and form bonds with one another, being a vehicle for grassroots collaborations to collaborate on neighborhood improvement efforts, improving processes for families to speak out or intervene when problems arise, and encouraging parents to intervene when such processes are in place.

Despite the unique contribution of this study, findings from this study should be interpreted in light its limitations. First, the nature of cross-sectional observational data at a single time point prevents us from drawing any causal conclusions. We cannot establish any temporal ordering of constructs included in the model. It is plausible that mothers’ levels of internal control could influence their desire or willingness to participate in community activities, as well as their perceptions of neighborhood processes. Second, given the high sensitivity and negative connotations of child maltreating behaviors, mothers tended to provide socially desirable and biased responses. Thus, the rate of child maltreatment behaviors in this study may have been underestimated. Third, we cannot rule out impacts of other alternative factors on outcome behaviors, such as parenting stress, maternal mental health status, and available community resources. In particular, it is important to note the challenges associated with social selection for neighborhood-related studies. We cannot parcel out the influence of social selection. Parents might choose to live in high-risk neighborhoods that provides less monitoring over their negative parenting behaviors. Our model definitely does not exhaust all potential pathways leading from community-relevant factors to individual child maltreating behaviors. Caution should be taken while interpreting the results and implications of this study. Another limitation related to the neighborhood aspect of this study is that we examine various neighborhood processes from the perspective of the survey respondent, which is the same individual who provides the information for the outcome measures. An individual’s opinion of the quality of a neighborhood is not an objective measure and is impacted by his or her own background, experience, and various psychological attributes. In a related study of this phenomenon, Polansky and colleagues (1985) found that within the same neighborhood, neglectful mothers reported fewer helping networks than non-neglecting neighbors. Because individual perspectives of neighborhood processes are impacted by individual attributes— attributes which may be associated with maltreatment—the association between neighborhood processes and maltreatment may be overstated. Fifth, we could not conduct multiple group analysis based on race/ethnicity due to an insufficient number of participants in each group. This hinders deeper understanding of measurement and structural invariance as well as any variation in path coefficients across multiple groups. Sixth, the sampling strategy used by the FFCWS led to overrepresentation of high-risk families and unwed mothers, and thus limits the generalizability of our findings of the entire population. Finally, the data from this wave were collected between 2001 and 2003, and to the extent that social mechanisms have changed since that time, the results may not generalize past this timeframe.

Findings in this study suggest several directions for future research related to the role of community participation in preventing child maltreatment. First, in our study, we were interested in the processes within neighborhoods that might contribute to mothers’ maltreating behaviors. Future studies should also incorporate neighborhood structural variables into the model, and explore the interaction between neighborhood structural and process factors. Multilevel structural equation modeling could be applied to estimate the effect of higher-level structural factors on child maltreatment and mediating variables. Second, the role of community participation on child maltreatment may vary greatly for fathers. Future research could examine whether the pathways still hold for fathers. Third, the large amount of missing data in this study prevents us from estimating more pathways as well as conducting multi-group analysis. Another venue for future research could be collecting or using dataset with fewer missing data to examine the role of community participation on child maltreatment.

Conclusion

How parents perceive and respond to their immediate environment, and their actual participation in community activities are important to the way they parent their children. This study found that community participation was associated with lower risk of child abuse and neglect. As such, one potential mechanism for prevention maltreatment is to provide additional opportunities for engaging parents in community programs or events.

Acknowledgments

This work benefits from the Fragile Families Study. The Fragile Families Study was funded by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD (#R01HD36916) and a consortium of private foundations. Persons interested in obtaining Fragile Families contract data should see http://www.fragilefamilies.princeton.edu for further information.

Contributor Information

Yiwen Cao, Doctoral Student, College of Social Work, Ohio State University, 1947 College Road, Columbus, Ohio 43210.

Kathryn Maguire-Jack, Assistant Professor, College of Social Work, Ohio State University

References

- Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103(3):411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Beck S, Ollendick T. Personal space, sex of experimenter, and locus of control in normal and delinquent adolescents. Psychological Reports. 1976;38:383–387. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1976.38.2.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Child maltreatment: An ecological integration. American Psychologist. 1980;35(4):320–335. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.35.4.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arieh A. Localities, social services and child abuse: The role of community characteristics in social services allocation and child abuse reporting. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32(4):536–543. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Coulton C, Crampton D, Irwin M, Spilbury J, Korbin J. How neighborhoods influence child maltreatment: A review of the literature and alternative pathways. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:1117–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulton CJ, Korbin JE, Su M. Neighborhoods and child maltreatment: a multilevel study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23(11):1019–1040. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deccio G, Horner WC, Wilson D. High-risk neighborhoods and high-risk families: Replication research related to the human ecology of child maltreatment. Journal of Social Services Research. 1994;18:123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Duke M, Fenhagen E. Self-parental alienation and locus of control in delinquent girls. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1975;127:103–107. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1975.10532360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BH, Abdi SM, Miller AB, White MT, Lincoln A. Protective factors for violence perpetration in Somali young adults: The role of community belonging and neighborhood cohesion. Psychology of Violence. 2015;5(4):384–392. [Google Scholar]

- Freisthler B. A spatial analysis of social disorganization, alcohol access, and rates of child maltreatment in neighborhoods. Children and Youth Services Review. 2004;26(9):803–819. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.02.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freisthler B, Gruenewald PJ, Remer LG, Lery B, Needell B. Exploring the Spatial Dynamics of Alcohol Outlets and Child Protective Services Referrals, Substantiations, and Foster Care Entries. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12(2):114–124. doi: 10.1177/1077559507300107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freisthler B, Gruenewald PJ, Ring L, LaScala EA. An Ecological Assessment of the Population and Environmental Correlates of Childhood Accident, Assault, and Child Abuse Injuries. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32(11):1969–1975. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00785.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freisthler B, Maguire-Jack K. Understanding the interplay between between neighborhood structural factors, social processes, and alcohol outlets on child physical abuse. Child Maltreatment. 2015;20(4):268–277. doi: 10.1177/1077559515598000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freisthler B, Merritt D, LaScala E. Understanding the ecology of child maltreatment: A review of the literature and directions for the future. Child Maltreatment. 2006;11(3):263–280. doi: 10.1177/1077559506289524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara T, Kubzansky LD, Matsumoto K, Kawachi I. The association between oxytocin and social capital. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e52018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara T, Yamaoka Y, Kawachi I. Neighborhood social capital and infant physical abuse: a population-based study in Japan. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2016;10(13) doi: 10.1186/s13033-016-0047-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J, Kostelny K. Child maltreatment as a community problem. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1992;16(4):455–464. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90062-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J, Sherman D. High-risk neighborhoods and high-risk families: The human ecology of child maltreatment. Child Development. 1980;51:188–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income counties. The Lancet. 373(9657):68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracia E, Musitu G. Social isolation from communities and child maltreatment: a cross-cultural comparison. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:153–168. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00538-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guterman NB, Lee SJ, Taylor CA, Rathouz P. Parental perceptions of neighborhood processes, stress, personal control, and risk for physical child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2009;33:897–906. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher L. A step-by-step approach to using SAS® for factor analysis and structural equation modeling. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kempe H, Silverman F, Steele B, Droegemueller W, Silver H. The battered-child syndrome. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1985;181:17–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.1962.03050270019004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B, Maguire-Jack K. Community interaction and child maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2015;41:146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbin JE, Coulton CJ, Chard S, Platt-Houston C, Su M. Impoverishment and child maltreatment in African American and European American neighborhoods. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10(02):215–233. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire-Jack K. Multilevel investigation into the community context of child maltreatment. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, & Trauma. 23(3):229–248. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire-Jack K, Showalter K. The protective effect of neighborhood social cohesion in child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2016;52:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire-Jack K, Wang X. Pathways from neighborhood to neglect: The mediating effects of social support and parenting stress. Children and Youth Services Review. 2016;66:28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar BE, Buka SL, Brennan RT, Holton JK, Earls F. A multi-level study of neighborhoods and parent-to-child physical aggression: Results from the project on human development in Chicago neighborhoods. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8:84–97. doi: 10.1177/1077559502250822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar BE, Goerge RM, Gilsanz P, Hill A, Subramanian SV, Holton JK, Duncan DT, Beatriz ED, Beardslee WR. Neighborhood-level social processes and substantiated cases of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2016;51:41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polansky N, Ammons P, Guadin J. Loneliness and isolation in child neglect. Social Casework. 1985;66(1):38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Schooler C. The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1978;19(1):2–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, McLanahan SS. Fragile Families: sample and design. Children and Youth Services Review. 2001;23(4–5):303–326. [Google Scholar]

- SAS. SAS Statistical Software: Release 9.4. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. How do communities undergird or undermine human development? Relevant contexts and social mechanisms. In: Booth A, Crouter AC, editors. Does it take a village? Community effects on children, adolescents and families. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Groves WB. Community structure and crime: Testing social-disorganization theory. The American Journal of Sociology. 1989;94(4):774–802. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Rauenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997 Aug;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker RE, Lomax RG. A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. third. New York, NY: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw C, McKay H. Juvenile delinquency in urban areas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1942. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX; StataCorp LP: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the parent-child conflict tactics scales: development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22(4):249–270. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M, Ghazinour M, Richter J. Annual research review: What is resilience within the social ecology of human development? The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54(4):348–366. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Child Maltreatment. Administration on Children and Families, Children’s Bureau; Washington, DC: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vinson T, Baldry E, Hargreaves J. Neighbourhoods, networks, and child abuse. The British Journal of Social Work. 1996;26:523–543. [Google Scholar]

- Wiehe V. Empathy and the locus of control in child abusers. Journal of Social Service Research. 1987;9(2–3):17–30. [Google Scholar]