Abstract

African American young women are overwhelmingly disproportionately burdened by HIV/AIDS in the United States today. The purpose of the current systematic review was to identify the characteristics of efficacious HIV risk-reduction prevention interventions targeting African American adolescent women in order to inform future intervention development and expansion. We searched PubMed, PsychInfo, and ProQuest databases for journal articles and dissertations published between 2000 and 2015 reporting the impacts of HIV risk-reduction prevention interventions in the U.S. targeting African American adolescent women under age 25. Twenty articles assessing the efficacy of 12 interventions were eligible for inclusion. Selected interventions represented a total of 5,556 African American adolescent women and primarily drew from self-efficacy and self-empowerment-based theoretical frameworks. One intervention targeted girls under age 13; eight included participants ages 13–17; ten targeted adolescents aged 18–24 years; and five interventions included women over age 24 among their participants. Most interventions consisted of in-person knowledge and skills-based group or individual sessions led by trained African American female health professionals. Three were delivered via personal electronic devices. All programs intervened directly at the individual-level; some additionally targeted mothers, friends, or sexual partners. Overall, efficacious interventions among this population promote gender and ethnic pride, HIV risk-reduction self-efficacy, and skills building. They target multiple socio-ecological levels and tailor content to the specific age range, developmental period, and baseline behavioral characteristics of participants. However, demonstrated sustainability of program impacts to date are limited and should be addressed for program enhancements and expansions.

Keywords: HIV, HIV Prevention Intervention, Sexually Transmitted Infections, African American, Women, Adolescents, Systematic Review

Introduction

African American young women are overwhelmingly disproportionately burdened by HIV/AIDS throughout the United States (U.S.) today. At current rates, 1 in 32 African American women will be diagnosed with HIV in her lifetime (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015a). This represents an infection rate 5 times higher than that of Hispanic/Latina women and 20 times higher than that of white women (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015a). Accordingly, HIV-related diseases are in the top 7 leading causes of death for African American women ages 20 through 44, a statement that is not true for women of any other racial/ethnic group in the U.S (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). African American adolescent females make up only 15% of the U.S. adolescent female population; yet, by the end of 2012, they comprised 64% of the female adolescents in the U.S. living with HIV (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015c).

As African American women are often diagnosed late in the disease process, it is believed that many African American women receiving their diagnoses in early adulthood acquired HIV during adolescence (Sionean et al., 2014). Additionally, over 60% of perinatal HIV transmissions in the U.S. occur among African Americans (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). As over half of first births among African American women occur before age 24 (Martin, Hamilton, Osterman, Curtin, & Mathews, 2015), perinatal HIV transmission is of particular concern for African American adolescent women. Thus, it is crucial to reduce the burden of HIV for all African American women, starting with adolescents, before many of the risk factors associated with HIV infection are already well-embedded in women’s lives. Prevention efforts appropriately developed for African American adolescent women’s age and developmental stages have the potential to reduce HIV incidence among adolescent African American women of today and the African American adult women and infants of tomorrow.

The immense and sustained disproportionate burden of HIV infection among young African American women is attributed to a complex combination of individual and environmental factors. As over 90% of HIV cases among African American women are acquired through heterosexual contact (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015b), the underlying etiology of the disproportionate burden of HIV among African American women differs from other populations with high rates of HIV — such as men who have sex with men and individuals who use intravenous drugs. Namely, the high prevalence and viral load of HIV, as well as elevated rates of gender inequity, poverty, and lack of educational resources in African American young women’s communities, are all believed to contribute to African American women’s elevated risk for HIV infection in adolescence and young adulthood. Further, the sexual risk behaviors of African American young men and women, and the prevalence of other STIs among African American women, contribute to African American women’s elevated risk, as well (Adimora, Schoenbach, & Floris-Moore, 2009; Paxton, Williams, Bolden, Guzman, & Harawa, 2013; Perkins, Voisin, & Stennis, 2013; Pflieger, Cook, Niccolai, & Connell, 2013; Raiford, Seth, & DiClemente, 2013; Stockman et al., 2013; Wingood & DiClemente, 2000). As Brawner states in an article exploring the multiple levels of HIV/AIDS disease burden among African American women, “…some African American women have minimal room for error because of the sheer concentration of HIV in their geographical and social environments” (Brawner, 2014, p. 634). Thus, African American adolescent women may be at elevated risk for acquiring HIV even when they do not personally exhibit high risk sexual behaviors (Adimora et al., 2006). Further, as adolescent women move along the developmental trajectory from early (<13 years old) to late adolescence (18–24), they are exposed to and engage in different risk behaviors and environments. Important variations in HIV risk behaviors and environments (e.g., sexual behavior, substance use) exist between early, middle, and late adolescence and may have important consequences for women’s risk of acquiring HIV during adolescence (Fergus, Zimmerman, & Caldwell, 2007). Consequently, in determining the most effective mechanisms for reducing HIV risk among African American adolescent women, the complex combination of individual and environmental factors that put African American women at elevated risk for acquiring HIV, as well as their age and developmental stage, must be considered.

The Current Study

As the HIV risk profile of African American adolescent women is unlike that of other populations in the U.S., we cannot predict which intervention characteristics will be most salient for program efficacy based on findings from other populations or studies that combine multiple populations (Lyles et al., 2007). Thus, the current systematic review is exploratory in nature, with the aim of identifying the characteristics of efficacious HIV risk-reduction prevention interventions specifically targeting African American adolescent women (under age 25). The current study aims to contribute to the literature in two important ways. First, we identify characteristics of recent efficacious HIV prevention efforts among this population (through 2015), thereby building upon earlier reviews. Secondly, we isolate the effects of studies specifically for African American heterosexual adolescent women, acknowledging that the risk profiles of African American adolescent women differ from that of older African American women, adolescent women of different races/ethnicities, and African American adolescent males. The findings from this study can be used in the creation and expansion of high-impact prevention approaches that address the needs, environments, and risks specific to African American adolescent women in the United States.

Methods

Search Strategy

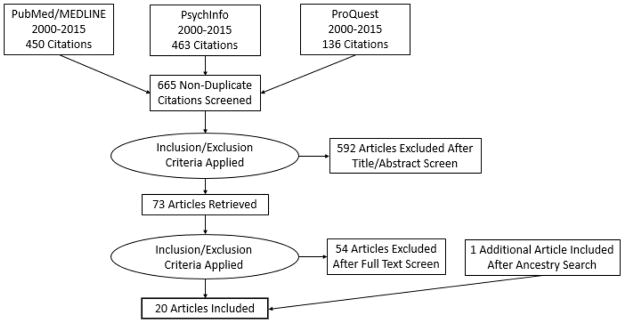

In January of 2016, both authors searched PubMed/MEDLINE, PsychInfo, and ProQuest databases for English-language journal articles and dissertations published between 2000 and 2015. The literature search strategy is outlined in Figure 1. Our search terms included a combination of words related to HIV, African American adolescent women, and efficacy studies of risk-reduction and/or prevention interventions (see search terms in Table 1). Our initial search yielded a total of 1,049 articles across the three databases.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search

Table 1.

Search terms, inclusion, and exclusion criteria

| Search Terms: |

| HIV OR “human immunodeficiency virus” |

| AND “African American” OR black |

| AND adolescen* OR teen* OR young OR youth* |

| AND female* OR women OR girl* OR gender |

| AND prevent* OR risk OR reduc* OR intervention* OR program* OR trial* OR experiment* OR efficac* OR impact* |

|

|

| Inclusion Criteria: |

|

|

| 01/01/2000 – 12/31/2015 |

| Interventions |

| Within the United States |

| Assessing outcomes of intervention ≥3 months post intervention |

| Includes control group |

| Quantitative-conducts statistical analysis to determine efficacy |

| Including African American adolescent women as a target population of the intervention |

| Sample >80% African American |

| If males included, data analyzed by gender |

| Mean age of participants is under 25 |

|

|

| Exclusion Criteria: |

|

|

| Interventions targeting transgender women |

| Interventions targeting IV drug users |

| Interventions targeting individuals living with HIV |

After removing duplicate citations retrieved from the databases (n=384), both authors screened the remaining 665 article titles and abstracts according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 1) and excluded irrelevant articles. During an in-person meeting, we discussed any discrepancies in excluded articles until consensus was reached on the final list of articles for full text screening. Ultimately, 592 articles were excluded at this stage. We repeated this process with both authors screening the full text of the remaining 73 articles and excluded an additional 54 articles that did not meet inclusion/exclusion criteria. The most common reasons articles were excluded during the full text screening were that they 1) did not test intervention effects (such as feasibility or acceptability studies), 2) only tested effects for a short duration (<3 months), or 3) did not include a comparison group in the study design. After an in-person meeting to resolve discrepancies, 19 articles remained for inclusion in the current review derived from the database searches. We next conducted an ancestry search, searching the reference lists of the included articles, for additional appropriate articles (n=1) resulting in a total of 20 articles for inclusion in the current systematic review.

Articles meeting our inclusion criteria assessed HIV risk-reduction intervention outcomes at least 3 months post intervention targeting African American adolescent women in the U.S. with a mean age of less than 25 years. Per quality criteria of HIV risk-reduction intervention studies established by the CDC (Lyles et al., 2007), we included only studies employing a comparison group to determine intervention effects that conducted statistical analyses to determine program efficacy or effectiveness. Articles that included adolescent women of other races/ethnicities were included if the study sample was comprised of over 80% African American adolescent women. Further, studies including adolescent males were only included if data was analyzed separately by gender. Due to the unique HIV risk profile of transgender women (Garofalo, Deleon, Osmer, Doll, & Harper, 2006) and individuals using intravenous drugs (Strathdee et al., 2010), interventions specifically targeting these populations were excluded. We also excluded interventions targeting HIV-positive individuals.

In a second review of the full text of the remaining articles, both authors extracted information describing the characteristics of the interventions (Tables 2 and 3). In describing the characteristics of the interventions, we extracted information regarding the theoretical or conceptual framework reported to drive the intervention approach, the subpopulation of African American adolescent women targeted by the intervention, the mode of delivery of intervention content, and how the comparison group treatment differed from the intervention group. To describe the studies (Table 4), we extracted the characteristics of the study sample, the participant recruitment strategy and/or location, the geographic and/or temporal setting, characteristics of the randomization strategy, the intervention outcomes assessed, and a summary of the main findings. We held an in-person meeting to discuss any discrepancies in extracted information and reach consensus on final information to be included in each of the tables.

Table 2.

Intervention characteristics of HIV risk-reduction programs targeting African American adolescent women

| Program | Reference(s) | Theoretical/ conceptual framework |

Target population | Mode of delivery | Control group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiHLE |

DiClemente et

al, 2004 Wingood et al, 2006 Milhausen et al, 2008 Sales et al, 2010 |

SCT, TGP |

|

|

|

| Enhanced SISTA | Belgrave et al, 2008 | SCT, TGP |

|

|

|

| HORIZONS |

DiClemente et

al, 2009 Sales et al, 2012 |

SCT, TGP |

|

|

|

| HORIZONS + PMI |

DiClemente et

al, 2014 Brown et al, 2014 |

SCT, TGP, Directive, cognitive-behavioral problem-solving and goal-setting approach |

|

|

|

| Multimedia SiHLE | Klein and Card, 2011 | SCT, TGP |

|

|

|

| SAHARA | Wingood et al, 2011 | SCT, TGP |

|

|

|

| SiHLE/HORIZONS adaptation |

Wingood et al,

2013 Seth et al, 2014 Seth et al, 2015 |

SCT, TGP |

|

|

|

| Imara | DiClemente et al, 2014 | SCT, TGP |

|

|

|

| MDRR: Mother/Daughter Risk Reduction | Dancy et al, 2009 | SCT, TRA/TPB |

|

|

|

| Centering-Pregnancy Plus | Kershaw et al, 2009 | SCT, ecological model |

|

|

|

| Project ORE |

Dolcini et al,

2010 Bangi et al, 2013 |

ARRM |

|

|

|

| LSC: Love, Sex, and Choices | Jones et al, 2013 | Sex script theory, Theory of Power as Knowing Participation in Change |

|

|

|

Abbreviations: ARRM: AIDS Risk Reduction Model; SCT: Social Cognitive Theory; TRA/TPB: Theory of Reasoned Action/Theory of Planned Behavior; TGP: Theory of Gender and Power; AA: African American

Table 3.

Age ranges of participants included in reviewed interventions (N=12)

| AGE RANGE |

SiHLE (ages 14–18) |

Enhanced SISTA (ages 18–39) |

HORIZONS (ages 15–21) |

HORIZONS + PMI (ages 14–20 |

Multimedia SiHLE (ages 14–19) |

SAHARA (ages 21–29) |

SiHLE/ HORIZONS adaptation (ages 18–29) |

Imara (ages 13–17) |

MDRR (ages 11–14) |

Centering Pregnancy Plus (ages 14–25) |

Project ORE (ages 14–21) |

Love, Sex, & Choices (ages 18–29) |

TOTALS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >24 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||||||

| 18–24 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | ||

| 13–17 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 8 | ||||

| <13 | X | 1 |

Table 4.

Study characteristics of HIV risk-reduction interventions targeting African American adolescent women

| Program | Reference | Sample | Recruitment | Setting | Study quality | Randomization level |

Outcome(s) | Summary of findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiHLE | DiClemente et al, 2004 |

|

Community health agencies | Birmingham, AL 1995–2002 |

|

|

|

|

| SiHLE | Wingood et al, 2006 |

|

Community health agencies | Birmingham, AL 1995–2002 |

|

|

|

|

| SiHLE | Milhausen et al, 2008 |

|

Community health agencies | Birmingham, AL 1995–2002 |

|

|

|

|

| SiHLE | Sales et al, 2010 |

|

Community health agencies | Birmingham, AL 1995–2002 |

|

|

|

|

| Enhanced SISTA | Belgrave et al, 2008 |

|

Churches, universities, clinics, community centers | Southeastern metropolitan area |

|

NIA |

|

|

| HORIZONS | DiClemente et al, 2009 |

|

Clinics providing sexual health services | Atlanta, GA 2002–2004 |

|

|

|

|

| HORIZONS | Sales et al, 2012 |

|

Clinics providing sexual health services | Atlanta, GA 2002–2004 |

|

|

|

|

| HORIZONS + PMI | DiClemente et al, 2014 |

|

Clinics providing sexual health services | Atlanta, GA 2005–2007 |

|

|

|

|

| HORIZONS + PMI | Brown et al, 2014 |

|

Clinics providing sexual health services | Atlanta, GA 2005–2007 |

|

|

|

|

| Multimedia SiHLE | Klein and Card, 2011 |

|

Market research firm e-mails, ads on Craigslist Facebook & Twitter, flyers at schools, & referrals from contacted individuals | Fremont, Concord, & Sunnyvale, CA |

|

|

|

|

| SAHARA | Wingood et al, 2011 |

|

Planned Parenthood clinic | Atlanta, GA |

|

|

|

|

| SiHLE/HORI ZONS adaptation | Wingood et al, 2013 |

|

Kaiser Permanente Centers | Atlanta, GA 2002–2006 |

|

|

|

|

| SiHLE/HORI ZONS adaptation | Seth et al, 2014 |

|

Kaiser Permanente Centers | Atlanta, GA 2002–2006 |

|

|

|

|

| SiHLE/HORI ZONS adaptation | Seth et al, 2015 |

|

Kaiser Permanente Centers | Atlanta, GA 2002–2006 |

|

|

|

|

| Imara | DiClemente et al, 2014 |

|

Short-term juvenile detention facility | Atlanta, GA 2011–2012 |

|

|

|

|

| MDRR: Mother/Daughter Risk Reduction | Dancy et al, 2009 |

|

NIA | Chicago, IL |

|

|

|

|

| Centering-Pregnancy Plus | Kershaw et al, 2009 |

|

Prenatal clinics | Atlanta, GA & New Haven, CT |

|

|

|

|

| Project ORE | Dolcini et al, 2010 |

|

Street outreach & community agency referral | San Francisco, CA |

|

|

|

|

| Project ORE | Bangi et al, 2013 |

|

Street outreach & community agency referral | San Francisco, CA |

|

|

|

|

| LSC: Love, Sex, and Choices | Jones et al, 2013 |

|

Public housing, STI clinics, community center, storefront, food pantry | Newark, Jersey City, East Orange, & Irvington, NJ |

|

|

|

|

Abbreviations: AA: African American; ACASI: Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview; NIA: No information available; d: days; mo: month; wk: week; fu: follow up; %: percentage; STI: sexually transmitted infection; pts: participants; M: mean; MDRR: Mother/Daughter Risk Reduction; HERR: Health Expert Risk Reduction; MDHP: Mother/Daughter Health Promotion

Methodological Quality Assessment

To evaluate the risk of bias for each of the HIV risk-reduction intervention studies (Lyles et al., 2007), we extracted information regarding the study design, the timeline of follow up outcome assessments, attrition rates, and methods of data collection. Methodological quality information for each study is presented in Table 4.

Results

Description of Intervention Features

Twelve interventions were assessed in the reviewed articles. Three of the interventions, SiHLE, HORIZONS, and Centering Pregnancy Plus (CPP), received a “Best” rating from the CDC in their assessments of Risk Reduction Evidence-based Behavioral Interventions (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015d). Best-evidence Risk Reduction Behavioral Interventions are those with a clearly detailed intervention design, a prospective study design with either a randomly-assigned or minimally-biased comparable control group, at least 50 participants per study arm, at least a 70% retention rate for each arm, a follow-up assessment at least 3 months post-intervention, and demonstrated positive, relevant intervention effects at p≤.05 (Lyles et al., 2007). The CDC defines a relevant outcome as a behavior “that directly impacts HIV risk or a biologic measure indicating HIV or STD infection” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014, p. 1). Five interventions (Multimedia SiHLE, SAHARA, SISTA/HORIZONS adaptation, Imara, and HORIZONS + PMI) are adaptations of one or more of the three CDC “Best” rated interventions listed above. The theoretical and conceptual frameworks informing intervention content and structure as well as the target populations and modes of intervention delivery are presented in Table 2 and described below.

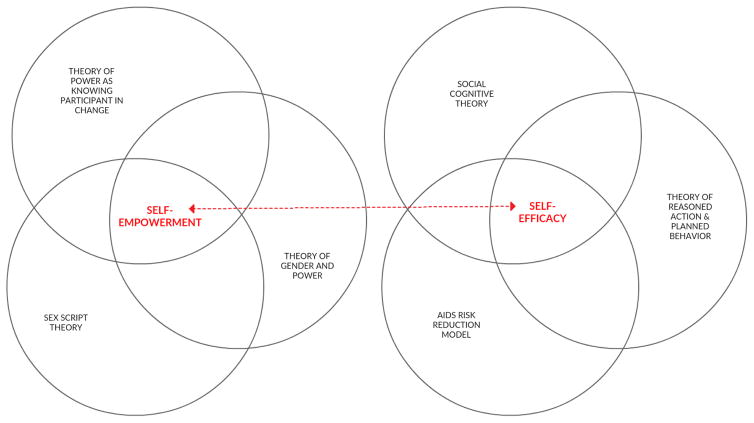

Theoretical frameworks

Each intervention describes one or more theoretical frameworks informing its content, approach, and design (see Table 2 and Figure 2). Common theoretical frameworks employed included those based on increasing participants’ self-efficacy around communicating with partners about sexual and reproductive health topics, refusing sex, and/or using condoms. Self-efficacy-based theoretical frameworks included the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), the AIDS Risk-Reduction Model (ARRM), the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). Other theoretical frameworks focus on increasing participants’ self-empowerment to increase the level of power or control a woman has in her romantic relationships and sexual experiences—including deciding when, with whom, and the steps that will be taken to lower HIV risk during sex, such as using condoms. Self-empowerment-based frameworks included the Theory of Gender and Power (TGP), Sex Script Theory (SST), and the Theory of Power as Knowing Participation in Change (TPKPC). Whether explicitly stated or not, several interventions draw upon socio-ecological models by additionally targeting the friends, mothers, and sex partners of African American adolescent women to reduce their risk of acquiring HIV.

Figure 2.

Dominant theoretical frameworks guiding HIV prevention interventions targeting African American adolescent women, 2000–2015

Target populations

Interventions targeted African American adolescent women from age 11 to 39 (see Table 3). One intervention targeted younger adolescents (ages 11–14); four specifically targeted older adolescents (over age 18). Most (n=7) interventions targeted adolescents of high school age; however, of these, five also targeted women over age 18. The intervention targeting younger adolescents also targeted the girls’ mothers (MDRR) and focused on the mother-daughter relationship and communication as protective against HIV risk. Project ORE targeted African American adolescent women ages 14–18 and their friends ages 14–21 with the objective that participating friends would reinforce the risk-reduction goals set by participants after completion of the single-session intervention. Interventions based on the HORIZONS model provided STI treatment vouchers or expedited therapy for male partners of participants testing positive for an STI in order to reduce participant risk of re-infection and extended biological vulnerability to HIV due to STI infection. Imara targeted African American adolescent women during detainment in a short-term juvenile detention facility as well as following their release to home. Eight interventions targeted adolescents reporting some level of sexual behavior risk (e.g., sexually initiated, recently sexually active, reporting recent unprotected sex with male). One intervention (MDRR) specifically targeted participants from households with low incomes or living in an area of high poverty.

Mode of delivery

Ten interventions were delivered in-person. Of these, all were conducted in group sessions save for one —Imara— which was delivered in-person individually in a juvenile detention center and in the participants’ homes. All in-person sessions were conducted by African American female nurses or health educators aside from MDRR which was delivered by the mothers of participants after they received 12 weeks of intervention facilitator training from research staff. Group sessions were delivered in healthcare settings, schools, community organizations or otherwise not specified. The number of in-person sessions ranged from one (Project ORE) to ten (Centering Pregnancy Plus). Two HORIZONS-based interventions with group sessions and Imara additionally provided individually tailored booster telephone contacts ranging from 4 (HORIZONS and Imara) to 18 (HORIZONS + PMI) to reinforce material from in-person sessions.

Some interventions with demonstrated efficacy via an in-person group design facilitated by African American female health educators or nurses have been adapted to test the efficacy of computer-delivered versions of the interventions in order to decrease per participant intervention cost and increase dissemination feasibility. One intervention (Multi-media SiHLE) delivered all intervention content via 2 60-minute computer-delivered sessions while SAHARA delivered content via a hybrid of 2 60-minute laptop sessions and one 15-minute in-person group session. One intervention did not originate from an in-person-delivery designs: Love, Sex, and Choices consisted of 12 weekly 15–20 minute soap opera video episodes delivered directly to smartphones provided to the participants. All in-person and telephone interventions were delivered by African American women; those delivered electronically featured African American women in video or audio form.

Description of Studies

Study characteristics are summarized in Table 4. Twenty articles assessing participant outcomes from 12 studies are included in the review. This represents 5,556 participants, 2,787 of whom received the intervention tested in the study. The 2,769 control participants received a variety of alternative treatments ranging from no intervention, to an intervention for a dissimilar topic such as nutrition and exercise, to a different version of the intervention than received by the treatment group (see Table 2). Studies range from 135 to 1,047 participants per study. The weighted mean average of the participants’ ages is 18.0 years across all 12 studies. Participant inclusion/exclusion criteria varied across studies. Nine studies included only non-married participants. Studies of 6 interventions included women seeking health services at specific locations. One study included only pregnant women (Centering Pregnancy Plus). Five studies specified that participants must not currently be pregnant and not trying to become pregnant. Other study inclusion criteria required that participants were recently sexually active, had ever had sex with a male, or reported high sexual risk behaviors such as recent unprotected sex with a male. One study included only women that had low incomes; one required that the women live in the same household as their mothers and another required that participants be willing to nominate a friend to participate. Studies conducting secondary analyses included sub-populations of the original study samples, such as only participants who had experienced intimate partner violence, and women reporting baseline depressive symptoms above a designated threshold. Participants were recruited through middle schools, reproductive and sexual health clinics, Kaiser Permanente, juvenile detention centers, community organizations, street outreach, flyers, market research emails and social networking, and/or participant referrals.

Studies assessed participant outcomes related to HIV risk-reduction mediators including HIV prevention knowledge, perceived risk, attitudes, intentions, assertiveness, depression, self-efficacy, parent or partner communication, sexual risk-reduction behaviors, condom application skills, and STI infection or re-infection. Assessed study outcomes reflect both documented direct HIV-risk reduction mediators (e.g., other STI infection, number of sexual partners —both concurrent and sequential, consistent condom use, sex while intoxicated) as well as mediators based on the theoretical frameworks informing intervention content and design (e.g., mother-child communication, assertiveness, condom and/or sex refusal self-efficacy).

Commonly reported indicators of study quality include the study design, time to the furthest assessment point, attrition rate, and the method of data collection. Study quality indicators are presented in Table 4. Eighteen studies used randomized control trial designs with one or two control arms. Two studies report multi-group quasi-experimental designs. Seven studies report conducting secondary or sub-analyses drawing from participant data from 4 randomized control trials. These studies assessed intervention mediators, or evaluated a sub-sample of the participants based on baseline (e.g., depression symptomology, experienced intimate partner violence) characteristics.

The furthest follow-up assessment is a key aspect of behavioral intervention study methodological quality due to the challenge of short-term behavioral interventions in producing sustainable behavior change among individuals within high-risk environments (Lyles et al., 2007). The presently reviewed studies range from 3 months post intervention to 36 months post primary treatment (HORIZONS + PMI) in their furthest point of follow up assessment, with the majority of studies assessing follow-up intervention outcomes between 3 and 12 months post baseline or post intervention. Attrition rates reflect the time to assessment which averages about 10% for assessments up to 3 months post intervention, 20% for assessments at 6 and 12 months post intervention and 39% for the intervention assessing outcomes at 36 months post primary treatment.

Due to the potentially sensitive nature of outcome assessment measures related to HIV risk reduction, twelve studies reported using Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview (ACASI) systems for participant self-reported data collection. Eight studies reported the use of pen and paper questionnaires. In studies assessing outcomes of the SiHLE and Imara interventions, participant condom application skills were assessed via an in-person assessment. Additionally, studies assessing incident STIs as an outcome of interest collected specimens to conduct STI testing.

Discussion

The aim of the current systematic review was to identify the characteristics of risk-reduction interventions with demonstrated efficacy in reducing HIV risk among African American adolescent females under age 25. As the ages of participants in the reviewed studies extended from early to late adolescence, the impacted outcomes reflect the developmental trajectories of adolescents as they progress from early to late adolescence and begin to engage in HIV risk behaviors such as sexual activity and drug and alcohol use. Outcomes ranged from more distal protective factors such as improving mother-child communication among early adolescents (the MDRR study targeted adolescents ages 11–14 regardless of sexual experience) to more proximal and direct protective factors such as increasing the proportion of condom-protected sex acts and reducing STI incidence among older adolescent women with a history of high-risk sexual behavior.

Overall, interventions with positive impacts among African American adolescent women promote self-empowerment and HIV risk-reduction self-efficacy and skills building. They tailor content to the developmental stage, age range, and baseline characteristics of participants, such as previous sexual behavior and incarceration status. Further, secondary analyses of intervention data revealed differential efficacy of interventions by women’s baseline depression symptomology, alcohol use, and experience with interpersonal violence.

Two main challenges for HIV risk-reduction interventions targeting African American adolescent women are demonstrating sustained intervention effects over time and the feasibility of expanding the intervention to reach more participants due to the per-participant resources required for in-person interventions. Notably, interventions in this review report success in extending intervention effects through the use of telephone booster sessions to reinforce in-person group interventions. Also, while not explicitly tested in the reviewed studies, interventions additionally targeting mothers, friends, and partners of African American adolescent women aim to extend sustainability of intervention effects by intervening at the interpersonal relationship level —anticipating that the intervention effects will continue to be reinforced through these relationships after completion of the structured intervention period. The reviewed interventions offer two promising strategies for testing the feasibility of scaling up efficacious in-person interventions: delivering intervention content through electronic devices, and training mothers to deliver intervention content in-person in lieu of health professionals. However, when moving from efficacy to effectiveness trials in delivering HIV risk-reduction interventions via electronic devices, researchers note challenges in feasibility of implementation (DiClemente et al., 2013).

While the reviewed studies contain variation in methodological quality, the majority of studies had clear descriptions of the tested interventions, comparable comparison groups, used ACASI systems and appropriate measures for collecting self-reported data, and maintained retention rates of over 70% by 3 months post-intervention. Considering the challenges associated with conducting sexual health intervention research with adolescents, it is expected that the validity of findings are relatively high for the reviewed studies.

Based on the synthesis of the reviewed studies, we present three main recommendations for practice and future research. Specifically, our findings suggest future studies and intervention efforts in this field should aim to: 1) address factors that have been demonstrated to modify intervention efficacy; 2) include and test strategies to promote long-term sustainability of intervention effects; and 3) continue efforts to promote scalability of efficacious interventions.

To increase intervention efficacy, intervention designers should consider addressing participants’ baseline characteristics that are demonstrated to modify intervention efficacy such as participants’ depression symptomology, substance use, experiences with interpersonal violence, previous sexual experience, and age. This could come in the form of screening participants for the type and content of intervention that would be most appropriate for them considering their baseline characteristics and/or incorporating content into the intervention that addresses these factors. Lessons can be learned from interventions that target both substance use and sexual risk prevention in their content and design (Belgrave, Corneille, Nasim, Fitzgerald, & Lucas, 2008; Coatsworth, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2002).

Also, accounting for variation in risk profile between age groups and developmental stages has the potential to increase the impact of HIV prevention programs among adolescent women. Adolescence is a long developmental period with extensive variation from beginning to end. In addition to the variation in experiences of HIV risk behaviors and environments across adolescence, there is wide variety in decision-making capabilities, autonomy, and access to resources from early to late adolescence that may be associated with adolescents’ risk, and their ability to lower their risk, for acquiring HIV. For example, while minors may consent to their own STI services in all states, they currently need parental consent for HIV testing in 19 states (Guttmacher, 2016). Researchers should consider adolescents’ age and developmental stage both when designing interventions and when analyzing intervention effects. Two studies included in this review found significant differential impacts between younger and older adolescents (Centering Pregnancy Plus and Project ORE) indicating important variation in program effects across adolescent age group and developmental stage. For example, Dolcini et al (2010) found no overall intervention effects across their Project ORE participants, but significant and distinct intervention impacts when assessing impact by age group within the study population. Similarly, in a test of Multimedia SiHLE, Klein and Card (2011) found differential intervention effects for condom use self-efficacy for their non-sexually initiated participants and sexually initiated participants.

While most of the reviewed interventions specifically targeted sexually initiated women and/or women already demonstrating sexual risk behaviors, much of the content addressed in the reviewed interventions is also developmentally appropriate for younger adolescents (Future of Sex Education Initiative, 2012). Thus, another potential strategy for enhancing intervention impact is to begin intervening earlier in adolescence, before sexual risk behavior patterns are already established. According to 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) results, one third of African American female 9th graders already report having had sex (Kann et al., 2014). Thus, African American adolescent women in high risk environments may be in need of effective risk reduction prevention intervention before entering high school. In order to test sustainability of effects of prevention efforts beginning earlier in adolescence, long-term follow up is necessary. If not feasible to follow a comparable control group longitudinally, researchers could draw from measures from national surveys (e.g., YRBS) and compare intervention participants’ behaviors in high school to similar population survey results. A study not included in the review targeted African American adolescent women under age 13 with promising initial efficacy results, but did not meet our inclusion criteria requirements for methodological quality (Bartlett & Shelton, 2010). An additional qualitative study of a prevention intervention for African American girls ages 9–12 was not included in the current review, but begins to address the need for earlier intervention for this population (Shambley-Ebron, 2009). Consequently, interventions targeting African American girls prior to entering high school are also in need of funding for developing trials with high methodological quality to test the longitudinal effects of their interventions.

Additionally, strategies to promote sustainability of intervention effects should be included in intervention design and tested against traditional short-term, individual-level interventions. One of the most promising strategies to date is the inclusion of follow-up telephone booster sessions (DiClemente et al., 2014). Also, interventions targeting mothers, friends, partners, and the community-at-large of African American adolescent women could be coupled with individual-level interventions and tested against individual-level-only interventions to determine if additional intervention in the environmental levels of the individuals prolongs intervention effects.

Finally, efforts to promote scalability of efficacious interventions, such as the use of computer-based multimedia prevention interventions and/or smart phone-delivered educational materials targeted to African American adolescent women, should continue. While researchers have identified successful strategies for adapting in-person content to be delivered electronically and in-person by mothers in lieu of health professionals, further implementation studies and effectiveness trials are needed for interventions targeting African American adolescent women. Lessons can be learned from the facilitators and barriers identified while scaling up other evidence-based HIV prevention interventions (Kegeles, Rebchook, Tebbetts, & Arnold, 2015).

Conclusion

This review provides further evidence that efficacious HIV prevention interventions targeting African American adolescent women promote gender and ethnic pride, self-empowerment, and HIV risk-reduction self-efficacy and skill building. They target multiple socio-ecological levels and tailor content to the specific age range, developmental period, and baseline behavioral characteristics of participants. However, demonstrated sustainability of program impacts to date are limited and should be addressed for program enhancements and expansions. In order to increase program efficacy and effectiveness in a cost-effective manner, our findings suggest that intervention designers should consider factors that are demonstrated to diminish intervention efficacy, include and test strategies to promote sustainability of intervention effects, and continue efforts to promote scalability of efficacious interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Sharon Brown for her guidance in the design and implementation of this review. They would also like to thank the authors and participants of the studies cited in this review. This research has received support from the grants, T32HD007081, Training Program in Population Studies, and R24HD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

C. Emily Hendrick is a PhD candidate in the Health Behavior and Health Education program in the College of Education and an NICHD Predoctoral Trainee in the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. She holds a master’s degree in Public Health with an emphasis in Maternal and Child Health from University of California, Berkeley. Broadly, her research interests include understanding and reducing maternal, child, and adolescent health disparities by investigating the determinants of women’s health behaviors and health across the reproductive years. Within this, she focuses on 1) the intergenerational transmission of health and well-being from mothers to children, and 2) the developmental period of adolescence as a time of vulnerability and opportunity in shaping women’s health behaviors and health across the life course.

Caitlin Canfield is a doctoral student in the Department of Sociology at the University of Texas at Austin where she is specializing in Demography. She works as a graduate student researcher with the Texas Policy Evaluation Project and is an NICHD Predoctoral Trainee in the Population Research Center at the University of Texas. Caitlin holds a master’s degree in Public Health with a specialization in International Health and Development from the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. Her research focuses on disparities in access to reproductive and sexual healthcare services as well as reproductive and sexual health outcomes. She seeks to utilize community-engaged research methods to effect policy change at the local and state levels.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions

CEH conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, participated in the extraction and interpretation of the data, and drafted the manuscript; CC participated in the design of the study, participated in the extraction and interpretation of the data, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

*Denotes articles included in review.

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Floris-Moore MA. Ending the epidemic of heterosexual HIV transmission among African Americans. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37(5):468–471. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FEA, Coyne-Beasley T, Doherty I, Stancil TR, Fullilove RE. Heterosexually transmitted HIV infection among African Americans in North Carolina. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;41(5):616–623. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000191382.62070.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bangi A, Dolcini MM, Harper GW, Boyer CB, Pollack LM.2013Psychosocial outcomes of sexual risk reduction in a brief intervention for urban African American female adolescents Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services 122146–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett R, Shelton T. Feasibility and initial efficacy testing of an HIV prevention intervention for Black adolescent girls. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2010;31(11):731–738. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2010.505313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Belgrave FZ, Corneille M, Nasim A, Fitzgerald A, Lucas V.2008An evaluation of an enhanced Sisters Informing Sisters about Topics on AIDS (SISTA) HIV prevention curriculum: The role of drug education Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services 74313–327. [Google Scholar]

- Brawner BM. A multilevel understanding of HIV/AIDS disease burden among African American women. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing: JOGNN / NAACOG. 2014;43(5):633–643. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12481. 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Brown JL, Sales JM, Swartzendruber AL, Eriksen MD, DiClemente RJ, Rose ES.2014Added benefits: Reduced depressive symptom levels among African-American female adolescents participating in an HIV prevention intervention Journal of Behavioral Medicine 375912–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leading Causes of Death by Age Group, Black Females-United States, 2011. 2011 Retrieved July 16, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/women/lcod/2011/WomenBlack_2011.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among Pregnant Women, Infants, and Children in the United States. 2012 Retrieved August 2, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk_WIC.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PRS Efficacy Criteria for Best-Evidence Risk Reduction (RR) Individual-level, Group-level, and Couple-level Interventions (ILIs/GLIs/CPLs) (Risk Reduction Chapter) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2015 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/dhap/prb/prs/efficacy/rr/criteria/hiv-rr-efficacy-best-ili-gli-cpls.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among African Americans. 2015a Retrieved July 14, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/africanamericans/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance by Race/Ethnicity Slide Set. 2015b Retrieved July 17, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/HIV_2013_RaceEthnicitySlides_508.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among Youth. 2015c Retrieved July 15, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/youth/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Compendium of Evidence-Based Interventions and Best Practices for HIV Prevention. 2015d Retrieved November 29, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prevention/research/compendium/rr/complete.html.

- Coatsworth JD, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. Familias Unidas: A family-centered ecodevelopmental intervention to reduce risk for problem behavior among Hispanic adolescents. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2002;5(2):113–132. doi: 10.1023/a:1015420503275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Dancy BL, Hsieh YL, Crittenden KS, Kennedy A, Spencer B, Ashford D.2009African American adolescent females: Mother-involved HIV risk-reduction intervention Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services 83292–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Bradley E, Davis TL, Brown JL, Ukuku M, Sales JM, … Wingood GM. Adoption and implementation of a computer-delivered HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention for African American adolescent females seeking services at county health departments: Implementation optimization is urgently needed. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2013;63(Suppl 1):S66–71. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318292014f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *DiClemente RJ, Davis TL, Swartzendruber A, Fasula AM, Boyce L, Gelaude D, … Staples-Horne M.2014Efficacy of an HIV/STI sexual risk-reduction intervention for African American adolescent girls in juvenile detention centers: A randomized controlled trial Women & Health 548726–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, Lang DL, Davies SL, Hook EW, III, et al. 2004Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: A randomized controlled trial JAMA 2922171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Rose ES, Sales JM, Lang DL, Caliendo AM, … Crosby RA.2009Efficacy of sexually transmitted disease/human immunodeficiency virus sexual risk–reduction intervention for African American adolescent females seeking sexual health services: A randomized controlled trial Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 163121112–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Sales JM, Brown JL, Rose ES, Davis TL, … Hardin JW.2014Efficacy of a telephone-delivered sexually transmitted infection/human immunodeficiency virus prevention maintenance intervention for adolescents: A randomized clinical trial JAMA Pediatrics 16810938–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Dolcini MM, Harper GW, Boyer CB, Pollack LM.2010Project ORE: A friendship-based intervention to prevent HIV/STI in urban African American adolescent females Health Education & Behavior 371115–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Future of Sex Education Initiative. National sexuality education standards: Core content and skills, K-12. 2012 Retrieved from: http://www.futureofsexed.org/documents/josh-fose-standards-web.pdf.

- Garofalo R, Deleon J, Osmer E, Doll M, Harper GW. Overlooked, misunderstood and at-risk: Exploring the lives and HIV risk of ethnic minority male-to-female transgender youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2006;38(3):230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher Institute. Minors’ Access to STI Services (State Policies in Brief) Washington, DC: 2016. Retrieved from https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/spibs/spib_MASS.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- *Jones R, Hoover DR, Lacroix LJ.2013A randomized controlled trial of soap opera videos streamed to smartphones to reduce risk of sexually transmitted human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in young urban African American women Nursing Outlook 614205–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Hawkins J, Harris WA, … Zaza S. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2013. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2014;63(4):1–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegeles SM, Rebchook G, Tebbetts S, Arnold E. Facilitators and barriers to effective scale-up of an evidence-based multilevel HIV prevention intervention. Implementation Science. 2015;10(1):50. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0216-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kershaw TS, Magriples U, Westdahl C, Rising SS, Ickovics J.2009Pregnancy as a window of opportunity for HIV prevention: Effects of an HIV intervention delivered within prenatal care American Journal of Public Health 99112079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Klein CH, Card JJ.2011Preliminary efficacy of a computer-delivered HIV prevention intervention for African American teenage females AIDS Education and Prevention 236564–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles CM, Kay LS, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Passin WF, Kim AS, … Mullins MM. Best-evidence interventions: Findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000–2004. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(1):133–143. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Curtin SC, Mathews TJ. National Vital Statistics Reports. 1. Vol. 64. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. Births: Final Data for 2013; pp. 1–65. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr64/nvsr64_01.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Milhausen RR, DiClemente RJ, Lang DL, Spitalnick JS, McDermott Sales J, Hardin JW.2008Frequency of sex after an intervention to decrease sexual risk-taking among African-American adolescent girls: Results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial Sex Education 8147–57. [Google Scholar]

- Paxton KC, Williams JK, Bolden S, Guzman Y, Harawa NT. HIV Risk Behaviors among African American women with at-risk male partners. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research. 2013;4(7):221. doi: 10.4172/2155-6113.1000221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins EL, Voisin DR, Stennis KAB. Brief research report: Sociodemographic factors associated with HIV status among African American women in Washington, DC. International Journal of Women’s Health. 2013;5:587–591. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S47162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflieger JC, Cook EC, Niccolai LM, Connell CM. Racial/ethnic differences in patterns of sexual risk behavior and rates of sexually transmitted infections among female young adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(5):903–909. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiford JL, Seth P, DiClemente RJ. What girls won’t do for love: Human immunodeficiency virus/sexually transmitted infections risk among young African-American women driven by a relationship imperative. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2013;52(5):566–571. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Sales JM, Lang DL, DiClemente RJ, Latham TP, Wingood GM, Hardin JW, Rose ES.2012The mediat ing role of partner communication frequency on condom use among African American adolescent females participating in an HIV prevention intervention Health Psychology 31163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Sales JM, Lang DL, Hardin JW, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM.2010Efficacy of an HIV prevention program among African American female adolescents reporting high depressive symptomatology Journal of Women’s Health 192219–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Seth P, Wingood GM, Robinson LS, DiClemente RJ.2014The impact of alcohol use on HIV/STI intervention efficacy in predicting sexually transmitted infections among young African-American women AIDS and Behavior 184747–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Seth P, Wingood GM, Robinson LS, Raiford JL, DiClemente RJ.2015Abuse impedes prevention: The intersection of intimate partner violence and HIV/STI risk among young African American women AIDS and Behavior 1981438–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shambley-Ebron DZ. My sister, myself: A culture- and gender-based approach to HIV/AIDS prevention. Journal of Transcultural Nursing: Official Journal of the Transcultural Nursing Society / Transcultural Nursing Society. 2009;20(1):28–36. doi: 10.1177/1043659608325850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sionean C, Le BC, Hageman K, Oster AM, Wejnert C, Hess KL … Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV Risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among heterosexuals at increased risk for HIV infection--National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System, 21 U.S. cities, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries (Washington, DC: 2002) 2014;63(14):1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockman JK, Lucea MB, Draughon JE, Sabri B, Anderson JC, Bertrand D, … Campbell JC. Intimate partner violence and HIV risk factors among African-American and African-Caribbean women in clinic-based settings. AIDS Care. 2013;25(4):472–480. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.722602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Hallett TB, Bobrova N, Rhodes T, Booth R, Abdool R, Hankins CA. HIV and risk environment for injecting drug users: The past, present, and future. The Lancet. 2010;376(9737):268–284. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60743-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Wingood GM, Card JJ, Er D, Solomon J, Braxton N, Lang D, … DiClemente RJ.2011Preliminary efficacy of a computer-based HIV intervention for African-American women Psychology and Health 262223–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Harrington KF, Lang DL, Davies SL, Hook EW, III, … Hardin JW.2006Efficacy of an HIV prevention program among female adolescents experiencing gender-based violence American Journal of Public Health 9661085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Robinson-Simpson L, Lang DL, Caliendo A, Hardin JW.2013Efficacy of an HIV intervention in reducing high-risk HPV, non-viral STIs, and concurrency among African-American Women: A randomized controlled trial Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 630–1S36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Education & Behavior. 2000;27(5):539–565. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]