Abstract

Background

Clinical trials show benefit from lowering systolic blood pressure in people aged ≥80 years but non-randomised epidemiological studies suggest lower systolic blood pressure may be associated with higher mortality. This study aimed to evaluate associations of SBP with all-cause mortality by frailty category over 80 years of age and to evaluate SBP trajectories before death.

Methods

A population-based cohort study was conducted using electronic health records of 144,403 participants aged 80 and older registered with family practices in the United Kingdom from 2001 to 2014. Participants were followed for up to five years. Clinical records of systolic blood pressure (SBP) were analysed. Frailty status was classified, using the e-Frailty Index, into the categories of ‘fit’, ‘mild’, ‘moderate’ and ‘severe’ frailty. All-cause mortality was evaluated by frailty status and mean SBP in Cox proportional hazards models. SBP trajectories were evaluated using person months as observations, with mean SBP and antihypertensive treatment status estimated for each person month. Fractional polynomial models were used to estimate SBP trajectories over five years before death.

Results

There were 51,808 deaths during follow-up. Mortality rates increased with frailty level and were greatest at SBP <110 mm Hg. In ‘fit’ women, mortality was 7.7 per 100 person years at SBP 120-139 mm Hg, 15.2 at SBP 110-119 mm Hg and 22.7 at SBP <110 mm Hg; for women with ‘severe’ frailty, rates were 16.8, 25.2 and 39.6 respectively. SBP trajectories showed an accelerated decline in the last two years of life. The relative odds of SBP<120 mm Hg were higher in the last three months of life than five years previously both in treated (odds ratio 6.06, 95% confidence interval 5.40 to 6.81) and untreated patients (6.31, 5.30 to 7.52). There was no evidence of intensification of antihypertensive therapy in the final two years of life.

Conclusions

A terminal decline of SBP in the final two years of life suggests that non-randomized epidemiological associations of low SBP with higher mortality may be accounted for by reverse causation, if participants with lower blood pressure values are closer, on average, to the end of life.

Keywords: hypertension, elderly, antihypertensive treatment, frailty, primary care, mortality

Blood pressure increases with age and older people have a higher prevalence of hypertension.1 2 Elevated systolic blood pressure (SBP) may be the most important risk factor for cardiovascular disease in older people.3 Recently, several large clinical trials4–9 have suggested that use of antihypertensive medications to lower blood pressure may reduce cardiovascular events and mortality in older adults. In the HYpertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET)6 of antihypertensive therapy over the age of 80 years, lowering blood pressure was associated with 30% reduction in stroke, 21% reduction in all-cause mortality, and 64% reduction in heart failure. In the Systolic Blood PRessure INtervention Trial (SPRINT),7 in people aged 75 years or older, management of SBP to a target of less than 120 mm Hg was associated with 34% reduction in cardiovascular events and 33% reduction in all-cause mortality. These results from clinical trials have prompted renewed interest in delivering more intensive management of SBP among very old people.

Several non-randomised epidemiological studies have raised concerns about the safety of intensive lowering of SBP in people aged 80 years and older. In the Umea cohort study of people aged more than 85 years, baseline SBP of less than 120 mm Hg was associated with substantially higher mortality than any other blood pressure category.10 An association of higher blood pressure with lower mortality has been reported in other cohort studies of people aged more than 7511, 12 or 85 years of age.13 These observational findings have led to the suggestion that high blood pressure may not be a risk factor for mortality over 85 years of age.14 The paradoxical association between lower SBP with increased mortality has sometimes been explained in terms of patients’ frailty, which may confound the association of low SBP with mortality in old age.12 There is evidence that SBP levels tend to decline as frailty status increases among very old patients,15 supporting future investigations into the modifying effect of frailty on the association of SBP with mortality. Frail older adults might also be at risk of adverse outcomes from antihypertensive treatment16 but if they are under-represented in trial samples, then the results of clinical trials might not be generalizable to wider community-dwelling populations.17, 18 Odden et al.,19 in an analysis of NHANES data, found evidence of effect modification according to frailty level in terms of walking speed. In fit persons over 65 years, elevated SBP was associated with greater mortality, while in frail participants higher blood pressure was associated with lower mortality risk.

This study aimed to investigate the reasons for conflicting results from non-randomised studies and clinical trials concerning the prognostic significance of SBP in older adults. We conducted longitudinal analyses of primary care electronic health records (EHR) data for a large cohort of adults aged 80 years or older in the United Kingdom. Participants were classified according to frailty level using a previously-reported measure.20 We aimed to evaluate whether the association of SBP with mortality was consistent at different levels of frailty, comparing participants according to antihypertensive treatment status. We also compared SBP trajectories for participants who died with those who did not die during five years’ follow-up.

Methods

Patient Involvement / Data Source

This study used data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). The CPRD is one of the world’s largest databases of primary care EHRs, including approximately 7% of UK general practices, with anonymized data collected from 1990 to present. The registered active population of about 5 million is generally representative of the UK population in terms of age and sex.21 Data collected into CPRD comprise clinical diagnoses, records of blood pressure and other clinical measurements, prescriptions, results of investigations and referrals to specialist services. The protocol for this study received scientific and ethical approval from the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee for CPRD studies (ISAC Protocol 13_151). The CPRD has broad National Research Ethics Service Committee (NRES) ethics approval for observational research studies. All data were fully anonymised and individual consent was not obtained. MG had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for its integrity and the data analysis.

Study Design and Participants

This research was part of a wider study of ageing in the CPRD population. For this we drew a random sample of participants who had their 80th, 85th, 90th, 95th and 100th birthdays while registered in CPRD between 1990 and 2014 including a maximum of 50,000 each of men and women, with replacement, in each age group. There were less than 50,000 men and 50,000 women eligible in the older age groups and, after accounting for participants sampled in more than one age-group, the total sample comprised 299,495 participants. This procedure enhanced representation of older ages in the sample. Participants entered the analysis at the age they were sampled and all analyses were adjusted for age and calendar year. In order to focus on a more recent period, the present analysis was restricted to 183,425 participants, who were registered between 1st January 2001 and 31st December 2009 with latest follow-up at 31st December 2014. After excluding participants who did not have one or more valid blood pressure records during follow-up, there remained 144,403 (79%) participants aged 80 years or older, with one or more blood pressure records.

Main measures

The study analyzed blood pressure measurements recorded into participants’ EHRs at consultations in primary care. For each participant, we calculated the mean of all systolic and diastolic records recorded within the first five years of follow-up. Participants were divided according to their mean SBP values into the categories <110, 110-119, 120-139, 140-159 and ≥160 mm Hg. Antihypertensive drug prescriptions recorded during the first year of follow-up were analyzed to determine whether participants were treated with antihypertensive medications, which were further classified into: A, drugs acting on the renin-angiotensin system, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blocking drugs; B, beta-blockers; C, calcium channel blockers; and D, thiazide diuretics.22 A further category of ‘Other’ antihypertensive drugs was defined, including centrally acting drugs, alpha-blockers and vasodilators.

Clinical records were used to determine smoking status,23 classified into ‘non-smoker’, ‘current smoker’ or ‘ex-smoker’. Body mass index (BMI) was categorized into underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0-29.9 kg/m2 and obese (≥30.0 kg/m2). Serum total cholesterol values were grouped into the categories <3.0, 3.0-3.9, 4.0-4.9, 5.0-5.9 and ≥ 6.0 mmol/L. Indicator variables were included for participants with no values recorded. The prevalence of co-morbidity at the start of the study was determined from analysis of Read medical codes, and drug product codes, for diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, stroke, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, musculoskeletal and connective tissue diseases and nervous system diseases. Multiple morbidity was coded into the categories none, 1 to 2, 3 to 4 and 5 or more. An index of frailty status was calculated for each participant using a previously published 36-item electronic Frailty Index (eFI).20 The eFI was defined based on a cumulative deficit model, which accounts for the number of deficits present in an individual.15 The eFI score was calculated by the presence or absence of individual deficits as a proportion of the total possible based on medical diagnoses recorded during the first 12 months of follow-up. Categories of fit, mild, moderate and severe frailty were defined following Clegg et al.20 but the assessment of quantitative traits (including blood pressure values) and polypharmacy (including antihypertensive medications) were omitted from the assessment of frailty as these were key exposures for this study. Deaths from any cause were obtained from CPRD records. Records were censored after 5 years of follow-up or when participants’ CPRD record ended.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of study participants were described. Time-to-event analyses were conducted to evaluate the association of mean SBP with death from any cause. Mortality rates per 100 person years were estimated as measures of absolute risk, while adjusted hazard ratios were estimated using the Cox proportional hazards model as measures of relative risk. The age at which participants were sampled was included as a stratification variable. The model was SBP category was the exposure of interest, with SBP 120-139 mm Hg as reference. Analyses were conducted separately by gender, frailty category and antihypertensive treatment status. Models were adjusted for age, comorbidity (including CHD, stroke, cancer, COPD, musculoskeletal disorders, digestive disorders, nervous system disorders and dementia), total cholesterol category and smoking status. For participants receiving anti-hypertensive medications, analyses were further adjusted for the number of classes of antihypertensive drugs prescribed and type of drug class. Schoenfeld residuals were evaluated to test the proportional hazards assumption which was not violated.

In order to evaluate blood pressure trajectories, we analyzed blood pressure records for the same sample of participants. We estimated the mean SBP value for each participant month for 60 months from five years before to death or end of study, including all SBP values recorded up to the date of death. We also evaluated antihypertensive drug prescribing over time and classified each participant month as ‘treated’ or ‘not treated’ with antihypertensive drugs. We also estimated the number of antihypertensive drug classes prescribed in each participant month. We used scatter plots, with lowess lines, to compare changes in mean SBP values over time for participants who died by the end of the study and participants who remained alive. We fitted second order fractional polynomial models using mean SBP values for each participant and each month as observations. Models were adjusted for age, gender, calendar year and frailty category. Robust variance estimates were employed to account for clustering of observations by participant. Models were fitted using the ‘mfp’ command in Stata version 14. Predicted values and their confidence intervals were estimated using the ‘fracpred’ command. Logistic regression models were fitted, using generalized estimating equations and robust variance estimates, to estimate the relative odds of SBP<120 mm Hg by quarter up to the date of death.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of 144,403 eligible participants by mean SBP category are shown in Table 1. There were 4,389 (3.0%) participants with SBP <110 mm Hg and 9,381 (6.4%) with SBP 110-119 mm Hg. There were 17,983 (12.5%) with SBP ≥160 mm Hg. Increasing frailty was generally associated with lower blood pressure. In those with SBP <110 mm Hg, 22% were ‘fit’, 28% had ‘moderate frailty’ and 12% had ‘severe frailty’. In participants with SBP ≥ 160 mm Hg, 42% were ‘fit’, 16% had ‘moderate frailty’ and 4% had ‘severe frailty’. Diagnoses of CHD, stroke and dementia were more frequent among those with lower SBP values. Dementia was diagnosed in 12% of participants with SBP<120 mm Hg but only 2% of those with SBP ≥160 mm Hg. Serum total cholesterol values were generally lower in those with lower SBP but there was no clear trend in cigarette smoking. Use of antihypertensive medications was generally more frequent in those with higher SBP values.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort by systolic blood pressure category.

| Systolic blood pressure category (mm Hg) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <110 | 110-119 | 120-139 | 140-159 | ≥160 | ||

| Total | n | 4,389 | 9,381 | 53,931 | 58,719 | 17,983 |

| Women | n | 2,186 (50) | 4,686 (50) | 28,250 (52) | 34,453 (59) | 12,252 (68) |

| Age | Mean, SD | 88.0 (5.4) | 87.1 (5.4) | 85.8 (5.2) | 85.1 (4.9) | 85.6 (4.9) |

| Frailty | Fit | 957 (22) | 2,192 (23) | 15,197 (28) | 21,129 (36) | 7,519 (42) |

| Mild | 1,658 (38) | 3,680 (39) | 22,017 (41) | 23,581 (40) | 6,821 (38) | |

| Moderate | 1,244 (28) | 2,479 (26) | 12,369 (23) | 10,843 (18) | 2,850 (16) | |

| Severe | 530 (12) | 1,030 (11) | 4,348 (8) | 3,166 (5) | 793 (4) | |

| Comorbidity at entry | CHD | 1,555 (35) | 3,332 (36) | 15,890 (29) | 12,870 (22) | 3,253 (18) |

| Stroke | 545 (12) | 1,180 (13) | 5,637 (10) | 4,465 (8) | 1,236 (7) | |

| Cancer | 964 (22) | 2,044 (22) | 11,045 (20) | 11,264 (19) | 3,108 (17) | |

| COPD | 1,040 (24) | 2,022 (22) | 11,142 (21) | 10,789 (18) | 2,932 (16) | |

| Musculoskeletal | 2,988 (68) | 6,527 (70) | 39,093 (72) | 42,096 (72) | 12,208 (68) | |

| Digestive | 2,592 (59) | 5,477 (58) | 31,240 (58) | 32,200 (55) | 8,823 (49) | |

| Nervous system | 3,077 (70) | 6,650 (71) | 39,057 (72) | 41,781 (71) | 12,103 (67) | |

| Dementia | 710 (16) | 1,342 (14) | 4,500 (8) | 2,377 (4) | 516 (3) | |

| Total Cholesterol (mmol/L) | Mean, SD, | 4.4 (1.1) | 4.5 (1.2) | 4.8 (1.2) | 5.1 (1.2) | 5.4 (1.2) |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | Mean, SD, | 63 (10) | 69 (10) | 74 (10) | 79 (10) | 84 (12) |

| Smoking status | Non smoker | 1,340 (31) | 3,445 (37) | 22,759 (42) | 27,304 (47) | 8,211 (46) |

| Current smoker | 517 (12) | 1,351 (14) | 8,359 (16) | 8,624 (15) | 2,189 (12) | |

| Ex smoker | 732 (17) | 1,904 (20) | 12,030 (22) | 12,522 (21) | 3,281 (18) | |

| Not recorded | 1,800 (41) | 2,681 (29) | 10,783 (20) | 10,269 (17) | 4,302 (24) | |

| Antihypertensive medications* | 2,141 (49) | 4,898 (52) | 31,912 (59) | 37,258 (63) | 11,264 (63) | |

| Renin angiotensin system medicatiions † | 1,476 (69) | 3,064 (63) | 17,136 (54) | 18,297 (49) | 5,531 (49) | |

| Beta-blockers † | 676 (32) | 1,745(36) | 10,764 (34) | 12,578 (34) | 4,308 (38) | |

| Calcium channel blockers † | 482 (23) | 1,425 (29) | 12,633 (40) | 16,091 (43) | 4,704 (42) | |

| Diuretics † | 332 (16) | 1,021 (21) | 10,502 (33) | 17,320 (46) | 5,943 (53) | |

| Other antihypertensive † | 86 (4) | 287 (6) | 2,591 (8) | 4,075 (11) | 1,701 (15) | |

Figures are frequencies (column percent) except where indicated.

drugs prescribed in first 12 months of patients’ record

as percent of participants treated with antihypertensive drugs

Mortality and Systolic Blood Pressure

There were 51,808 deaths during follow-up. Table 2 presents mortality rates per 100 person years by frailty, SBP category and antihypertensive treatment status. Mortality increased with increasing frailty category. At each level of frailty, mortality rates were lowest among participants with SBP 140-159 mm Hg, while for participants with SBP 100-119 mm Hg mortality rates were more than twice as high and for participants with SBP<110 mm Hg mortality was more than three times as high. The results were similar among those who were treated with antihypertensive medications and those who were not on treatment. The data reveal that 340 / 7,221 (5%) of treated patients with severe frailty, and 285 / 22,224 (1%) of fit patients, had SBP records less than 110 mm Hg.

Table 2.

Numbers of deaths and mortality rates per 100 person years (py) by systolic blood pressure and frailty category.

| Frailty category | Systolic blood pressure category (mm Hg) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <110 | 110-119 | 120-139 | 140-159 | ≥160 | ||

| Not Treated with Antihypertensive Medications | ||||||

| Fit | N | 672 | 1,478 | 8,463 | 10,350 | 3,807 |

| Mean age | 88.2 | 86.9 | 85.5 | 84.6 | 84.8 | |

| Deaths | 413 | 703 | 2,696 | 2,248 | 833 | |

| Rate (per 100 py) | 20.3 | 13.4 | 8.0 | 5.1 | 5.3 | |

| Mild frailty | N | 846 | 1,742 | 8,510 | 7,491 | 2,080 |

| Mean age | 88.8 | 88.3 | 86.8 | 86.0 | 86.7 | |

| Deaths | 608 | 1,046 | 3,607 | 2,326 | 685 | |

| Rate (per 100 py) | 28.6 | 19.6 | 11.8 | 8.1 | 9.0 | |

| Moderate frailty | N | 540 | 941 | 3,860 | 2,832 | 672 |

| Mean age | 89.3 | 88.5 | 87.7 | 87.5 | 88.3 | |

| Deaths | 432 | 631 | 1,892 | 1,203 | 309 | |

| Rate (per 100 py) | 40.3 | 25.5 | 15.3 | 12.6 | 14.7 | |

| Severe frailty | N | 190 | 322 | 1,186 | 788 | 160 |

| Mean age | 89.1 | 88.7 | 88.4 | 88.1 | 88.4 | |

| Deaths | 162 | 233 | 713 | 409 | 87 | |

| Rate (per 100 py) | 47.9 | 32.3 | 20.7 | 18.0 | 22.5 | |

| Treated with Antihypertensive Medications | ||||||

| Fit | N | 285 | 714 | 6,734 | 10,779 | 3,712 |

| Mean age | 87.5 | 86.3 | 84.5 | 83.9 | 84.6 | |

| Deaths | 185 | 355 | 2,064 | 2,307 | 917 | |

| Rate (per 100 py) | 22.7 | 15.2 | 7.7 | 5.1 | 6.3 | |

| Mild frailty | N | 812 | 1,938 | 13,507 | 16,090 | 4,741 |

| Mean age | 87.5 | 86.1 | 85.1 | 84.7 | 85.6 | |

| Deaths | 599 | 1,036 | 4,864 | 4,322 | 1,506 | |

| Rate (per 100 py) | 31.9 | 16.7 | 9.7 | 6.8 | 8.7 | |

| Moderate frailty | N | 704 | 1,538 | 8,509 | 8,011 | 2,178 |

| Mean age | 86.8 | 86.6 | 85.9 | 85.6 | 86.5 | |

| Deaths | 522 | 942 | 3,696 | 2,717 | 848 | |

| Rate (per 100 py) | 33.8 | 21.9 | 12.7 | 9.3 | 11.6 | |

| Severe frailty | N | 340 | 708 | 3,162 | 2,378 | 633 |

| Mean age | 87.6 | 86.7 | 86.6 | 86.5 | 87.1 | |

| Deaths | 267 | 469 | 1,643 | 1,020 | 293 | |

| Rate (per 100 py) | 39.6 | 25.2 | 16.8 | 13.1 | 16.1 | |

In order to address confounding and the influence of antihypertensive treatment, adjusted hazard ratios for the association of SBP category with mortality were estimated separately by antihypertensive treatment status for men and women and for each frailty category (Table 3). Analyses were adjusted for diastolic blood pressure, age and comorbidity, total cholesterol and smoking status. In men and women, there was a greater relative hazard for SBP 110-119 or <110 mm Hg compared with SBP 120-139 mm Hg as reference category. This association was observed both in participant treated with antihypertensive drugs and untreated participants. Hazard ratios were higher for SBP <110 mm Hg than for SBP 110-119 mm Hg. Hazard ratios for a given SBP category were generally consistent across frailty categories. Hazard ratios were generally lower for SBP 140-159 mm Hg than the reference category. SBP ≥160 mm Hg was not generally associated with higher relative hazard, except in men with severe frailty. When 10 mm Hg systolic blood pressure categories were used for analysis of the sample as a single group, the hazard ratio for SBP 130-139 mm Hg, compared with 120-129 mm Hg as reference, was 0.82 (0.79 to 0.84).

Table 3.

Association of SBP category with all-cause mortality by frailty category, gender and anti-hypertensive treatment.

| SBP category (mm Hg) | ‘Fit’ | ‘Mild frailty’ | ‘Moderate frailty’ | ‘Severe frailty’ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | ||

| Not Treated with Antihypertensive Medications | |||||||||

| Men | <110 | 1.71 (1.42 to 2.05) | <0.001 | 1.96 (1.66 to 2.30) | <0.001 | 2.05 (1.69 to 2.47) | <0.001 | 1.78 (1.21 to 2.64) | 0.004 |

| 110-119 | 1.29 (1.13 to 1.47) | <0.001 | 1.47 (1.31 to 1.65) | <0.001 | 1.58 (1.36 to 1.84) | <0.001 | 1.39 (1.06 to 1.82) | 0.015 | |

| 120-139 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| 140-159 | 0.83 (0.76 to 0.90) | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.78 to 0.92) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.77 to 1.00) | 0.052 | 1.28 (1.01 to 1.61) | 0.039 | |

| ≥160 | 0.87 (0.76 to 0.99) | 0.029 | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.17) | 0.876 | 1.15 (0.91 to 1.46) | 0.239 | 2.32 (1. 57 to 3. 45) | <0.001 | |

| Women | <110 | 1.63 (1.35 to 1.95) | <0.001 | 1.61 (1.38 to 1.88) | <0.001 | 2.11 (1.77 to 2.53) | <0.001 | 2.00 (1.55 to 2.58) | <0.001 |

| 110-119 | 1.26 (1.10 to 1.44) | 0.001 | 1.24 (1.12 to 1.39) | <0.001 | 1.43 (1.25 to 1.64) | <0.001 | 1.47 (1.20 to 1.82) | <0.001 | |

| 120-139 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| 140-159 | 0.73 (0.67 to 0.80) | <0.001 | 0.80 (0.74 to 0.87) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.82 to 0.99) | 0.039 | 0.85 (0.72 to 1.01) | 0.062 | |

| ≥160 | 0.82 (0.72 to 0.92) | 0.001 | 0.81 (0.72 to 0.92) | 0.001 | 0.93 (0.79 to 1.11) | 0.423 | 0.79 (0.56 to 1.11) | 0.176 | |

| Treated with Antihypertensive Medications | |||||||||

| Men | <110 | 2.02 (1.54 to 2.66) | <0.001 | 2.51 (2,16 to 2.91) | <0.001 | 2.00 (1.71 to 2.33) | <0.001 | 1.62 (1.25 to 2.09) | <0.001 |

| 110-119 | 1.54 (1.30 to 1.83) | <0.001 | 1.45 (1.32 to 1.60) | <0.001 | 1.44 (1.29 to 1.61) | <0.001 | 1.31 (1.11 to 1.53) | 0.001 | |

| 120-139 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| 140-159 | 0.78 (0.71 to 0.85) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.78 to 0.88) | <0.001 | 0.89 (0.82 to 0.96) | 0.004 | 0.89 (0.77 to 1.03) | 0.112 | |

| ≥160 | 0.98 (0.85 to 1.13) | 0.748 | 1.04 (0.94 to 1.16) | 0.436 | 1.18 (1.01 to 1.37) | 0.028 | 1.21 (0.90 to 1.63) | 0.212 | |

| Women | <110 | 1.86 (1.39 to 2.47) | <0.001 | 1.98 (1.67 to 2.35) | <0.001 | 2.34 (1.98 to 2.77) | <0.001 | 1.98 (1.53 to 2.56) | <0.001 |

| 110-119 | 1.48 (1.23 to 1.79) | <0.001 | 1.46 (1.30 to 1.63) | <0.001 | 1.55 (1.38 to 1.75) | <0.001 | 1.44 (1.24 to 1.70) | <0.001 | |

| 120-139 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| 140-159 | 0.76 (0.70 to 0.84) | <0.001 | 0.79 (0.74 to 0.84) | <0.001 | 0.81 (0.75 to 0.87) | <0.001 | 0.80 (0.72 to 0.89) | <0.004 | |

| ≥160 | 0.85 (0.75 to 0.96) | 0.011 | 0.91 (0.83 to 1.00) | 0.068 | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.06) | 0.401 | 0.97 (0.82 to 1.15) | 0.733 | |

Figures are hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals adjusted for age, diastolic blood pressure, comorbidity, total cholesterol, smoking and anti-hypertensive treatment.

Systolic Blood Pressure Trajectories

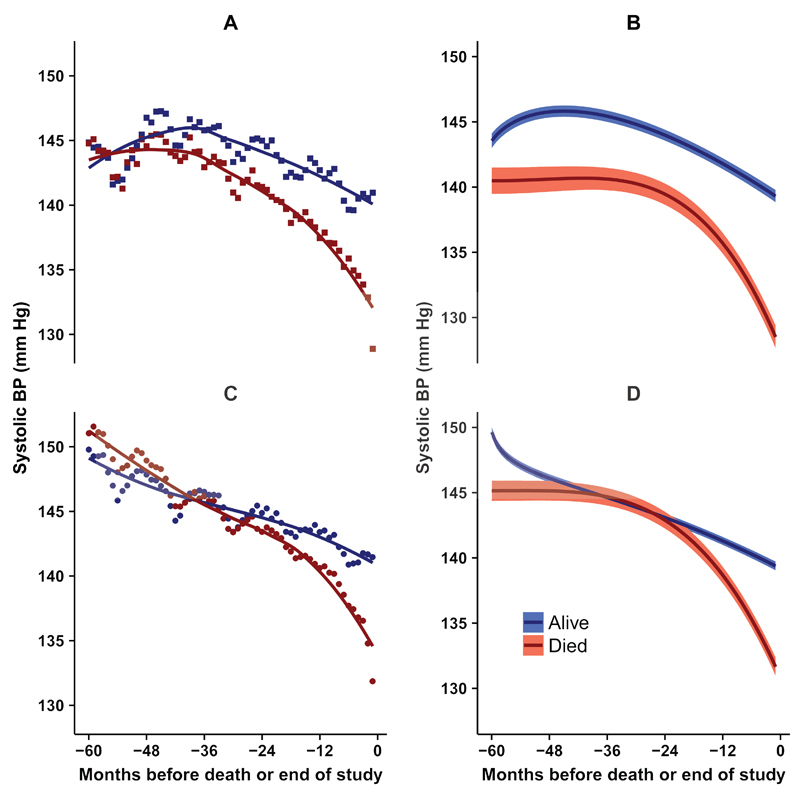

In order to clarify the association of SBP with mortality, we plotted the mean of SBP values recorded by month from five years before death or end of study (Figure 1). Data are presented for 144,403 participants in total. There were a mean of 16,970 (range 10,610 to 26,464) participants contributing data in any single month. Individual participants contributed data in a mean of seven months (range 1 to 58 months). Figure 1 (left panel) shows that mean SBP values declined over time. This decline was more rapid among participants who died than in those who did not die during the study. In the last 12 to 24 months of life, the decline in SBP showed an acceleration, with SBP values being approximately 15 mm Hg lower at the end of the period than at the beginning. SBP values were initially higher in participants who were treated with antihypertensive medications but a terminal decline in SBP values before death was observed in both treated and untreated participants.

Figure 1. Trajectory of systolic blood pressure during 60 months before death (red) or end of study (blue).

Left panels show mean SBP by month: (A) squares, not treated; (C) circles, treated with antihypertensive medications. Right panels show predictions (95% confidence intervals) from multiple fractional polynomial model adjusted for age, gender, calendar year and frailty category: (B) not treated; (D) treated with antihypertensive medications.

Fractional polynomial (FP) models were fitted separately for participants who died, or did not die, by antihypertensive treatment status (Figure 1 right panels and Supplementary Table 1). FP models were adjusted for gender, age, frailty category and calendar year. The FP plots (Figure 1, right panels) confirm an accelerated decline in SBP in the last 24 months of life. In a logistic regression analysis, the relative odds of SBP<120 mm Hg were higher in the last three months of life than five years previously both in treated (odds ratio 6.06, 95% confidence interval 5.40 to 6.81) and untreated patients (6.31, 5.30 to 7.52). (Supplementary Figure 1).

Additional Information and Sensitivity Analyses

Table 4 shows data for blood pressure recording and antihypertensive therapy for deceased and surviving participants by year. Participants who died during the five year study period necessarily had shorter overall follow-up than those who survived. The proportion of participants with one or more blood pressure readings in each year was generally slightly higher among surviving participants than those who died (P<0.001). Surviving participants also tended to have more frequent blood pressure readings than those who died. We noted that the number of blood pressure readings available for analysis was associated both with the mean systolic blood pressure category and with the level of frailty (Supplementary Table 2). Among ‘fit’ participants the median number of BP readings per participant year ranged from 0.8 to 1.8, while for participants with severe frailty the median number of BP readings per year ranged from 2.3 to 3.0. However, SBP trajectories were similar for participants who had had either more, or less than or equal to the mean number of seven participant months with SBP values recorded. (Supplementary Figure 2). There was no evidence that patients who died received more intense antihypertensive therapy. Surviving participants included a slightly lower proportion not prescribed antihypertensive drugs, with higher proportions prescribed two or more classes of antihypertensive drugs (P<0.001). Antihypertensive drug prescribing increased over the period (P<0.001) but there was only weak evidence for a difference in trend according to whether patients survived or not (P=0.042). There was no evidence for intensification of antihypertensive therapy in the final months of life. When participants who died within six months of study entry were excluded from the analysis there was no difference in interpretation (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 4.

Changes in blood pressure and antihypertensive therapy in five years before death.

| Years before Number at study | Number at risk in year | With ≥1 BP reading in year, Freq. (%) | Mean number of months with BP readings* | Mean (SD) SBP | Number of antihypertensive drug classes prescribed in year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No AHT drugs | One class | Two classes | Three classes | Four or more classes | ||||||

| Alive | -5 | 70,954 | 52,379 (74) | 2.5 | 145.4 (17) | 27,759 (39) | 18,402 (26) | 15,793 (22) | 7,140 (10) | 1,860 (3) |

| -4 | 76,716 | 58,513 (76) | 2.5 | 144.3 (17) | 28,096 (37) | 20,333 (27) | 17,884 (23) | 8,104 (11) | 2,299 (3) | |

| -3 | 82,816 | 65,181 (79) | 2.4 | 142.9 (17) | 29,221 (35) | 22,627 (27) | 19,691 (24) | 8,808 (11) | 2,469 (3) | |

| -2 | 88,879 | 72,285 (81) | 2.4 | 141.5 (17) | 30,492 (34) | 24,982 (28) | 21,202 (24) | 9,545 (11) | 2,658 (3) | |

| -1 | 92,554 | 77,463 (84) | 2.3 | 139.6 (17) | 31,168 (34) | 26,697 (29) | 22,320 (24) | 9,831 (11) | 2,538 (3) | |

| Died † | -5 | 8,131 | 4,147 (51) | 1.8 | 144.5 (20) | 3,612 (44) | 2,332 (29) | 1,513 (19) | 529 (7) | 145 (2) |

| -4 | 18,309 | 11,567 (63) | 2.1 | 142.7 (19) | 7,646 (42) | 5,494 (30) | 3,557 (19) | 1,299 (7) | 313 (2) | |

| -3 | 29,425 | 20,556 (70) | 2.1 | 140.6 (19) | 11,795 (40) | 9,077 (31) | 5,875 (20) | 2,169 (7) | 509 (2) | |

| -2 | 39,830 | 31,258 (78) | 2.1 | 138.3 (20) | 15,418 (39) | 12,724 (32) | 8,047 (20) | 2,977 (7) | 664 (2) | |

| -1 | 43,133 | 36,679 (85) | 2.3 | 133.6 (19) | 16,153 (37) | 14,074 (33) | 8,970 (21) | 3,212 (7) | 724 (2) | |

Figures are frequencies (row percent) except where indicated.

Mean number of months in year with BP values recorded for participants with one or more readings

person-time was eligible for analysis from 1st January 2010 to 31st December 2014. Participants who died during this period necessarily had shorter duration of follow-up overall

Discussion

Main Findings

In this large cohort of individuals aged 80 years or older, SBP <120 mm Hg was associated with greater risk of mortality in both men and women when compared to SBP of 120 to 139 mm Hg. The level of frailty was classified from data recorded into primary care EHRs. While mortality was higher in more frail participants, the association of SBP <120 mm Hg with mortality was consistently observed at each level of frailty. The proportion of treated patients with SBP <110 mm Hg increased with frailty level, which might indicate over-treatment in some cases. Longitudinal analysis of participants’ blood pressure records revealed a secular decline in SBP24 but in participants who die, there is an accelerated decline in SBP in the final 24 months of life. These last months of life are associated with greatly increased odds of low SBP recordings. These observations may account for the discrepancy between clinical trial results, which provide evidence of benefit from blood pressure lowering, as compared to non-randomized studies, which generally associate lower SBP with higher mortality. Randomization will ensure that comparison groups are, on average, similar with respect to underlying risk of mortality; in non-randomized studies, reverse causation may apply if lower SBP values are accounted for by proximity to death. Changes in SBP before death were generally similar in participants who were treated, or not treated, with antihypertensive drugs. Analysis of blood pressure recording and prescription of antihypertensive drugs revealed no evidence to suggest that there might be intensification of antihypertensive therapy to account for lower blood pressure before death. Participants who survived to the end of the study period had more frequent blood pressure recordings and were more likely to be treated with multiple antihypertensive drug classes.

Strengths and Limitations

The study has the strengths of a large sample of older adults with comprehensive data for medical diagnoses and drug treatment. The eligibility criteria were unrestricted and the sample may have included non-ambulatory patients, as well as those with dementia or living in nursing homes. These groups of patients are often excluded from clinical trials. Blood pressure measurements were recorded in clinical practice using possibly non-standardized methods, with no regularity of measurements over time in individual participants. Blood pressure measurements in the clinic may be higher than usual ambulatory values25 and may also be appreciably higher than those recorded in clinical trials. In the SPRINT trial a 5 minute rest period was observed for all BP measurements.7, 26 We did not have information concerning resting time, position, cuff size, device type, number of measurements nor whether orthostatic BP measurements were recorded. In spite of these limitations analysis of measurements routinely recorded in primary care may closely resemble those encountered by physicians in their usual practice.

The effect of misclassification of blood pressure will generally be to reduce the strength of reported associations. We did not have sufficient data concerning the dosage of antihypertensive medications. It may also be noted that although information on prescription might be available we cannot guarantee administration of the drugs. There were also missing and possibly misclassified values for important covariates including smoking, which might lead to bias. There is no consensus on the definition of the frailty syndrome and different operational tools have been used to measure this condition 27. Studies comparing different models suggest that most tools used to assess frailty are strongly associated with adverse outcomes including mortality. 28, 29 The Frailty Phenotype 30 and the Frailty Index31 are the two most widely used frailty models. We used a deficit accumulation model to assess frailty, whereas the Frailty Phenotype includes physical measures of frailty such as walking speed, grip strength, low physical activity and weight loss. Studies comparing these models have shown that they both predict adverse outcomes but different frailty models might not necessarily identify the same individuals as frail.32 It is also important to emphasise that physical measures may be difficult to complete in the very old due to their poor health and possible inability to participate.33 The e-Frailty index is based on clinical diagnoses, and records of age-related impairments, that impact on physical and mental functioning. We assumed that items not recorded were absent but clinical records may sometimes have low sensitivity for age-related impairments, especially when these are in their early stages. For example, the prevalence of clinical dementia diagnosis in this sample is almost certainty an underestimate of the true prevalence of the condition. Both the Frailty Phenotype and the deficit accumulation approach may predict adverse outcomes but there may be differential classification of individuals.34 We did not have data concerning gait speed or other objective physical function measures and it should be noted that lack of objective measures of functional problems and including cognitive function may be a limitation of the eFI. However assessment of physical function across different primary care practices might result in bias from misclassification. The eFI addresses activity limitations and cognitive functioning through the analysis of physician recorded diagnostic codes. We excluded blood pressure measurements from estimation of the frailty index but we did not exclude clinical diagnoses of hypotension, hypertension and dizziness which contribute to the 36 deficits contained in the frailty index. This implies that hypertensive individuals may be classified as slightly more frail, but we analyzed frailty in broad categories as recommended by the scale developers. We compared SBP trajectories of participants who died with those who survived to the end of the study but associations might be diminished if the surviving patients were also nearing the end of their lives. During the period of study, there were changes in antihypertensive drug utilisation in this population with declining use of diuretics and increasing use of drugs acting on the renin-angiotensin system and calcium channel blockers.24 There were also secular declines in systolic blood pressure24 and mortality.35 More people are living to older ages but often with greater comorbidity.36 We caution that associations might differ in future periods of time.

Comparison with previous research

In the HYVET trial 6 of antihypertensive therapy over the age of 80 years, blood pressure lowering was associated with substantial reduction in stroke, all-cause mortality and heart failure. In the SPRINT trial 7 in people aged 75 years or older, management of SBP to a target of less than 120 mm Hg was associated with reduction in cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality. To address concerns that the trial samples may not have been representative, each of these clinical trials conducted analyses to show that the main findings were consistent across frailty categories.17, 18

Several previous observational studies showed a negative association of increased blood pressure and mortality in the very old 2, 13, 14, 37, 38. A report from the Established Populations for Epidemiological Studies of the Elderly (EPESE)13 found that in younger elderly individuals aged 65 to 84 years there was a positive association between SBP and mortality even after adjusting for co-morbidities, whereas in men aged 85 years or above, higher SBP was associated with lower mortality. In women aged 85 years and over there was no association between SBP and mortality.13 Rastas et al.39 found that SBP <140 mmHg was associated with higher all-cause mortality in all men and women after adjusting for confounders. In the Umea 85+ study, low SBP was associated with greater mortality even after adjustment for pre-existing comorbidity and frailty.10, 39 While it has been suggested that the association between low blood pressure and mortality might be an indicator of a greater disease burden and a marker of poor health, our results show that low SBP is associated with mortality even in ‘fit’ participants. The results from a population study by Nilsson et al.40 in those aged 80 years and older showed that low SBP was associated with an increased risk of cognitive decline irrespective of frailty status. In the PARTAGE (The Predictive Values of Blood Pressure and Arterial Stiffness in Institutionalized Very Aged Population) study of institutionalized older adults aged 80 years and over, there was effect modification from antihypertensive treatment. Participants with low SBP (<130mm Hg) receiving two or more antihypertensive drugs were at an increased risk of mortality compared to the group receiving either one or no antihypertensive drugs. This study included an institutional sample which may differ from our community dwelling sample and differing definitions of antihypertensive treatment were employed.41 Analysis of NHANES data suggested that the association of lower BP with greater mortality was most evident in frail participants.19 In the present study, mortality rates were elevated for lower blood pressures at all levels of frailty. These differences might be explained by differing participant selection and choice of frailty classification. Considering the totality of evidence, a systematic review suggested that ‘less aggressive treatment’ would be an optimal approach in treating hypertension in older adults.42 A review exploring the management of hypertension in those aged 80 years and over suggested that individualized treatment plans should be designed when treating frail older adults.43

Kalantar-Zadeh et al.44 noted that lower SBP values have been associated with higher mortality in patients with heart failure and end-stage renal failure45 and offered several explanations for this finding. People who live to advanced ages, or to advanced disease states, are necessarily highly selected with the consequence that survivor bias may contribute to patterns of association that differ from those observed in the general population.44 The temporal pattern of exposure may also be important if higher blood pressure confers a short-term survival advantage in the final months of life.44 Deteriorating nutritional status, accompanied by chronic inflammation, may also tend to lower blood pressure levels at the end of life.44

Our results suggest that a substantial decline in blood pressure may be a recognizable feature of the final stages of life, at least in the final two years, with lower SBP often being a marker of proximity to death. Accelerated functional decline before death was noted by Diehr et al.46 in data from the Cardiovascular Health Study. This decline is sometimes referred to as ‘terminal decline’ or ‘terminal drop’.47 Terminal decline has been described previously with respect to cognitive function48 and subjective health measures49 but not blood pressure.

Conclusions

In non-randomized data for people aged more than 80 years, SBP <120 mmHg is associated with higher mortality irrespective of frailty status, gender or antihypertensive treatment. This association may be explained in part by a terminal decline of SBP which is observed in the final two years of life. These observations may account for the discrepancy between randomized and non-randomized studies of SBP and mortality in people aged more than 80 years. Reverse causation may apply if lower SBP values result from proximity to death. The present data may not provide an explanation for BP-outcome associations earlier than two years before death. Whether the observation of more favourable outcomes with higher SBP for periods more than two years before death is ‘true’ or confounded remains uncertain. Consequently, it may be inadvisable to base blood pressure treatment recommendations on non-randomized data for effectiveness outcomes. We noted SBP values less than 110 mm Hg in a minority of treated patients, which suggests that reducing the intensity of antihypertensive therapy may sometimes be important in this age group.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

What is new?

Clinical trials suggest that antihypertensive treatment for octogenarians may reduce mortality and cardiovascular events but non-randomized epidemiological studies generally associate low blood pressure with higher mortality in older adults.

This paper presents data for 144,403 people aged more than 80 years living in the UK.

The sample was classified by frailty level and antihypertensive treatment status.

Longitudinal analysis of patients’ blood pressure records revealed that there is a ‘terminal decline’ in systolic blood pressure in the 24 months before death, not accounted for by changes in antihypertensive treatment.

What are the clinical implications?

Clinicians may be concerned by epidemiological analyses that suggest that lower systolic blood pressure may be associated with higher mortality in older adults.

Recognition that systolic blood pressure may enter a phase of ‘terminal decline’ in the last 24 months of life suggests that ‘reverse causation’ may account for non-randomized epidemiological associations of lower SBP with higher mortality because participants with low blood pressure values may, on average, be closer to the end of life.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the Dunhill Medical Trust [grant number: R392/1114]. MG and AD were supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Safar ME, Levy BI, Struijker-Boudier H. Current perspectives on arterial stiffness and pulse pressure in hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Circulation. 2003;107:2864–2869. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000069826.36125.B4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dregan A, Ravindrarajah R, Hazra N, Hamada S, Jackson SHD, Gulliford MC. Longitudinal Trends in Hypertension Management and Mortality Among Octogenarians: Prospective Cohort Study. Hypertension. 2016;68:97–15. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staessen JA, Gasowski J, Wang JG, Thijs L, Hond ED, Boissel J-P, Coope J, Ekbom T, Gueyffier F, Liu L, Kerlikowske K, et al. Risks of untreated and treated isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly: meta-analysis of outcome trials. Lancet. 2000;355:865–872. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)07330-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu L, Wang JG, Gong L, Liu G, Staessen JA. Comparison of active treatment and placebo in older Chinese patients with isolated systolic hypertension. Systolic Hypertension in China (Syst-China) Collaborative Group. J Hypertension. 1998;16:1823–1829. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816120-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, Celis H, Arabidze GG, Birkenhager WH, Bulpitt CJ, de Leeuw PW, Dollery CT, Fletcher AE. Randomised double-blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension. The Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) Trial Investigators. Lancet. 1997;350:757–764. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)05381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, Staessen JA, Liu L, Dumitrascu D, Stoyanovsky V, Antikainen RL, Nikitin Y, Anderson C. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1887–1898. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, Berlowitz DR, Campbell RC, Chertow GM, Fine LJ, Haley WE, Hawfield AT, Ix JH, Kitzman DW, et al. Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥75 years: A randomozed clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:2673–2682. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahlof B, Lindholm LH, Hansson L, Schersten B, Ekbom T, Wester PO. Morbidity and mortality in the Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension (STOP-Hypertension) Lancet. 1991;338:1281–1285. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92589-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Party MW. Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults: principal results. MRC Working Party. BMJ : BMJ. 1992;304:405–412. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6824.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molander L, Lovheim H, Norman T, Nordstrom P, Gustafson Y. Lower systolic blood pressure is associated with greater mortality in people aged 85 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1853–1859. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hakala SM, Tilvis RS, Strandberg TE. Blood pressure and mortality in an older population. A 5-year follow-up of the Helsinki Ageing Study. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:1019–1023. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo Z, Viitanen M, Winblad B. Low blood pressure and five-year mortality in a Stockholm cohort of the very old: possible confounding by cognitive impairment and other factors. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:623–628. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.4.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satish S, Freeman DH, Jr, Ray L, Goodwin JS. The relationship between blood pressure and mortality in the oldest old. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:367–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Bemmel T, Gussekloo J, Westendorp RG, Blauw GJ. In a population-based prospective study, no association between high blood pressure and mortality after age 85 years. J Hypertension. 2006;24:287–292. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000200513.48441.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381:752–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morley JE. Hypertension: Is It Overtreated in the Elderly? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11:147–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.12.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pajewski NM, Williamson JD, Applegate WB, Berlowitz DR, Boli LP, Chertow GM, Krousel-Wood MA, Lopez-Barrera N, Powell JR, Roumie CL, Still C, et al. Characterizing Frailty Status in the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:649–655. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warwick J, Falaschetti E, Rockwood K, Mitnitski A, Thijs L, Beckett N, Bulpitt C, Peters R. No evidence that frailty modifies the positive impact of antihypertensive treatment in very elderly people: an investigation of the impact of frailty upon treatment effect in the HYpertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) study, a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of antihypertensives in people with hypertension aged 80 and over. BMC Med. 2015;13:78. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0328-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Odden MC, Peralta CA, Haan MN, Covinsky KE. Rethinking the association of high blood pressure with mortality in elderly adults: The impact of frailty. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1162–1168. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clegg A, Bates C, Young J, Ryan R, Nichols L, Ann Teale E, Mohammed MA, Parry J, Marshall T. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing. 2016;45:353–360. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrett E, Gallagher AM, Bhaskaran K, Forbes H, Mathur R, van Staa T, Smeeth L. Data Resource Profile: Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) Intern J Epidemiol. 2015;44:827–836. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sever P. New Hypertension Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence and the British Hypertension Society. J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2006;7:61–63. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2006.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Booth HP, Prevost AT, Gulliford MC. Validity of smoking prevalence estimates from primary care electronic health records compared with national population survey data for England, 2007 to 2011. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:1357–1361. doi: 10.1002/pds.3537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravindrarajah R, D A, Hazra NC, Hamada S, Jackson SHD, Gulliford MC. Declining blood pressure and intensification of blood pressure management among people over 80 years. Cohort study using electronic health records. J Hypertens. 2017 doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001291. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanner RM, Shimbo D, Seals SR, Reynolds K, Bowling CB, Ogedegbe G, Muntner P. White-Coat Effect Among Older Adults: Data From the Jackson Heart Study. J Clin Hypertens. 2016;18:139–145. doi: 10.1111/jch.12644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bakris GL. The Implications of Blood Pressure Measurement Methods on Treatment Targets for Blood Pressure. Circulation. 2016;134:904–905. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xue Q-L. The Frailty Syndrome: Definition and Natural History. Clin geriatr med. 2011;27:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitnitski A, Fallah N, Rockwood MR, Rockwood K. Transitions in cognitive status in relation to frailty in older adults: a comparison of three frailty measures. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15:863–867. doi: 10.1007/s12603-011-0066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cigolle CT, Ofstedal MB, Tian Z, Blaum CS. Comparing models of frailty: the Health and Retirement Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:830–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:146–156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rockwood K. Conceptual Models of Frailty: Accumulation of Deficits. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:1046–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Iersel MB, Rikkert MG. Frailty criteria give heterogenous results when applied in clinical practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:728–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00668_14.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collerton J, Martin-Ruiz C, Davies K, Hilkens CM, Isaacs J, Kolenda C, Parker C, Dunn M, Catt M, Jagger C, von Zglinicki T, et al. Frailty and the role of inflammation, immunosenescence and cellular ageing in the very old: cross-sectional findings from the Newcastle 85+ Study. Mech Ageing Dev. 2012;133:456–466. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rockwood K, Andrew M, Mitnitski A. A comparison of two approaches to measuring frailty in elderly people. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:738–743. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Office of National Statistics. National Life Tables: England. London: Office for National Statistics; 2016. [accessed 20th Feb 2017]. Source: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/lifeexpectancies/bulletins/nationallifetablesunitedkingdom/20132015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Office for National Statistics. Estimates of the Very Old (including Centenarians): England and Wales, and United Kingdom, 2002-2015. London: Office for National Statistics; 2016. [accessed 20th Feb 2017]. Source: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/ageing/bulletins/estimatesoftheveryoldincludingcentenarians/2002to2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boshuizen HC, Izaks GJ, van Buuren S, Ligthart GJ. Blood pressure and mortality in elderly people aged 85 and older: community based study. BMJ. 1998;316:1780–1784. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7147.1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adamsson Eryd S, Gudbjornsdottir S, Manhem K, Rosengren A, Svensson AM, Miftaraj M, Franzen S, Bjorck S. Blood pressure and complications in individuals with type 2 diabetes and no previous cardiovascular disease: national population based cohort study. BMJ. 2016;354:i4070. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rastas S, Pirttilä T, Viramo P, Verkkoniemi A, Halonen P, Juva K, Niinistö L, Mattila K, Länsimies E, Sulkava R. Association Between Blood Pressure and Survival over 9 Years in a General Population Aged 85 and Older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:912–918. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nilsson SE, Read S, Berg S, Johansson B, Melander A, Lindblad U. Low systolic blood pressure is associated with impaired cognitive function in the oldest old: longitudinal observations in a population-based sample 80 years and older. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007;19:41–47. doi: 10.1007/BF03325209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benetos A, Labat C, Rossignol P, Fay R, Rolland Y, Valbusa F, Salvi P, Zamboni M, Manckoundia P, Hanon O, Gautier S. Treatment with multiple blood pressure medications, achieved blood pressure, and mortality in older nursing home residents: The partage study. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:989–995. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Musini VM, Tejani AM, Bassett K, Wright JM. Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4:CD000028. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000028.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benetos A, Rossignol P, Cherubini A, Joly L, Grodzicki T, Rajkumar C, Strandberg TE, Petrovic M. Polypharmacy in the aging patient: Management of hypertension in octogenarians. JAMA. 2015;314:170–180. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Block G, Horwich T, Fonarow GC. Reverse epidemiology of conventional cardiovascular risk factors in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1439–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klassen PS, Lowrie EG, Reddan DN, DeLong ER, Coladonato JA, Szczech LA, Lazarus JM, Owen WF., Jr Association between pulse pressure and mortality in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. JAMA. 2002;287:1548–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.12.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diehr P, Williamson J, Burke GL, Psaty BM. The aging and dying processes and the health of older adults. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:269–278. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00462-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palmore E, Cleveland W. Aging, Terminal Decline, and Terminal Drop. J Gerontol. 1976;31:76–81. doi: 10.1093/geronj/31.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siegler IC. The terminal drop hypothesis: Fact or artifact? Exp Aging Res. 1975;1:169–185. doi: 10.1080/03610737508257957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diehr P, Williamson J, Patrick DL, Bild DE, Burke GL, Md Patterns of Self-Rated Health in Older Adults Before and After Sentinel Health Events. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:36–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.