Abstract

Aim

To study and explores the feasibility and efficacy of re-irradiation (Re-RT) for locally recurrent head and neck cancer (HNC) and second primary (SP) malignancies.

Background

The most common form of treatment failure after radiotherapy (RT) for HNC is loco-regional recurrence (LRR), and around 20–50% of patients develop LRR. Re-irradiation (Re-RT) has been the primary standard of care in the last decade for unresectable locally recurrent/SP HNC.

Materials and methods

It was a retrospective analysis in which we reviewed the medical records of 51 consecutive patients who had received Re-RT to the head and neck region at our institute between 2006 and 2015.

Results

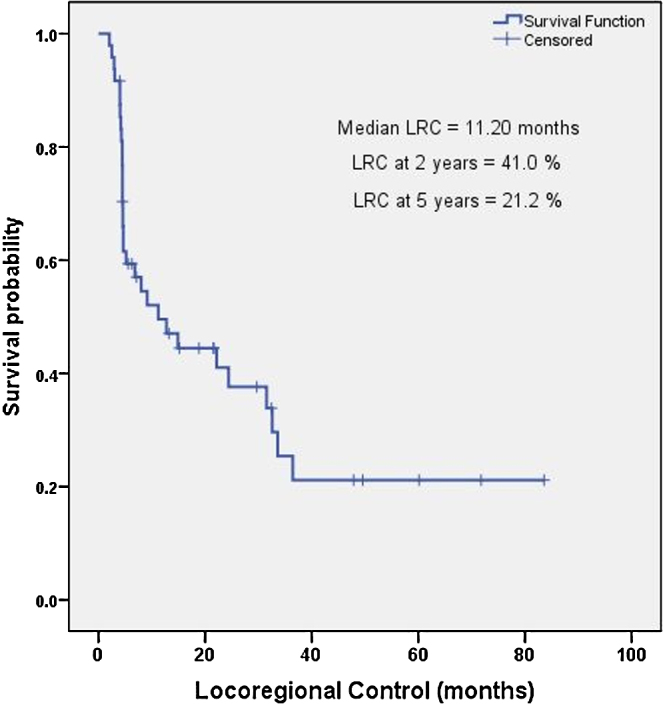

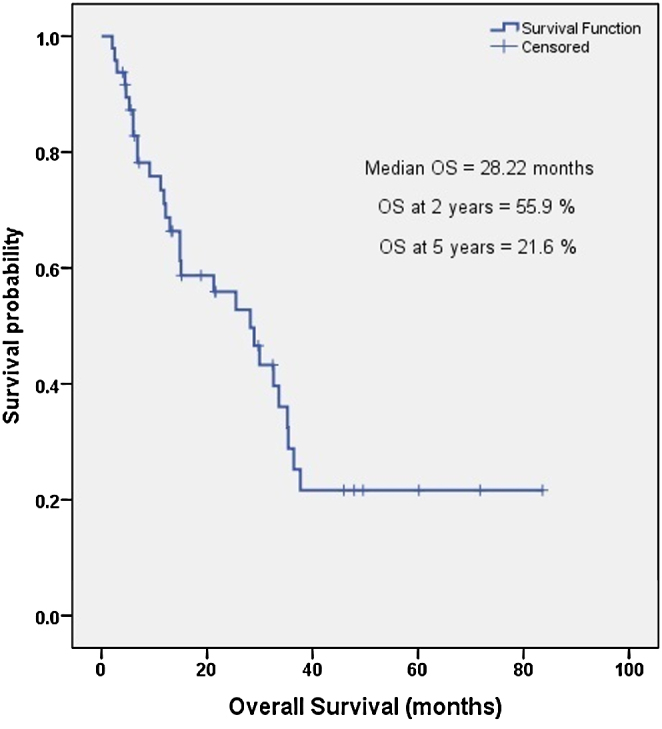

Forty-eight patients were included for assessment of acute and late toxicities, response evaluation at 3 months post Re-RT, and analyses of locoregional control (LRC) and overall survival (OS). The median LRC was 11.2 months, and at 2 and 5 years the LRC rates were 41% and 21.2%, respectively. A multivariate analysis revealed two factors: initial surgical resection performed prior to Re-RT, and achievement of CR at 3 months after completion of Re-RT to be significantly associated with a better median LRC. The median OS was 28.2 months, and at 1, 2, and 5 years, OS were 71.1%, 55.9% and 18%, respectively. A multivariate analysis revealed initial surgical resection performed prior to Re-RT, and achievement of CR at 3 months post completion of Re-RT being only two factors significantly associated with a better median OS. Acute toxicity reports showed that no patients developed grade 5 toxicity, and 2 patients developed grade 4 acute toxicities.

Conclusion

Re-RT for the treatment of recurrent/SP head and neck tumors is feasible and effective, with acceptable toxicity. However, appropriate patient selection criteria are highly important in determining survival and treatment outcomes.

Keywords: Head neck, Reirradiation, Intensity modulated radiotherapy, Recurrent, Salvage

1. Background

The most common form of treatment failure after radiotherapy (RT) for head and neck cancers (HNC) is locoregional recurrence (LRR), and around 20–50% of patients develop LRR.1, 2, 3 Those who survive are also at risk of developing a second primary (SP) malignancy. The risk of SP varies from 3 to 5% per year.4, 5 An added complication for LRR and SP malignancy is the fact that salvage therapy often yields poor results. Despite advancements in surgery, survival rates for locally recurrent/SP are low, with 40–60% of cancer-related deaths being due to LRR.6, 7 Moreover, recurrent disease is only resectable in 15–20% of patients. The remaining patients require management with either palliative chemotherapy or supportive care.

Reirradiation (Re-RT) has been the primary standard of care in the last decade for unresectable locally recurrent/SP HNC. The main reasons for this include the availability and increasing use of newer RT techniques, such as intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), “renewed confidence” of physicians in delivering a second course of RT with radical intent, and the information available about factors which can be used for appropriate patient selection for Re-RT. Moreover, Re-RT has replaced chemotherapy and supportive care as the treatment of choice for unresectable locally recurrent/SP HNC.

One of the challenges of Re-RT is the fact that patients have previously received a high dose of irradiation. Therefore, the probabilities of late toxicities are increased, especially in instances where Re-RT is delivered in a short time interval after the first course of RT, or in the event that surgical resection has been performed for the first primary or locally recurrent/SP HNC. Growing evidence favoring the role of Re-RT for unresectable locally recurrent/SP HNC and postoperative Re-RT in patients with high risk features following salvage surgery has been presented in the last decade.

We reviewed our 10 years of experience in using IMRT for Re-RT for locally recurrent/SP HNC, and explored the long-term treatment outcomes, toxicity, and factors that affect the treatment outcomes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Pretreatment work up

The institutional ethics board approved this retrospective study. We reviewed the medical records of 51 consecutive patients who had received Re-RT to the head and neck region at our institute between 2006 and 2015. The first course of RT was performed either at our centre or elsewhere.

The patient selection criteria were stringent for this study. The inclusion criteria were:

-

1.

Patients for whom the first course of RT technique type (either conventional or IMRT) and total delivered target dose were available

-

2.

Patients who did not develop severe toxicity as a result of prior radiation

-

3.

First and recurrent/SP malignancy were squamous cell carcinomas

-

4.

Re-RT using IMRT only

-

5.

Retreated sites included oral cavity, oropharynx, larynx and hypopharynx only (nasopharynx, paranasal sinus, salivary gland, thyroid, skin and metastasis of unknown origin were excluded)

-

6.

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status ≤2 at the time of Re-RT

-

7.

Intent of Re-RT being curative, with or without concurrent chemotherapy

-

8.

Minimum time period between completion of the first course of RT and the commencement of Re-RT was 1-year

Patients who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy were excluded from our analyses.

Tumors were classified as SP when they originated more than 2 cm away from the original tumor site or when patients had been in complete remission for at least 24 months.

Pretreatment assessment included clinical examination, endoscopy with biopsy under anesthesia, locoregional imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and metastatic screening using chest radiography and upper abdominal ultrasound. Thirty-six (70%) patients underwent positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT). Dental prophylaxis was done for all patients prior to the commencement of Re-RT. Assisted feeding (nasogastric tube or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy) was provided for 23 (45%) patients before the commencement of Re-RT.

2.2. Treatment strategy

All patients were assessed by a Multidisciplinary Tumor Board and evaluated for surgical resection. Two patients who were treated with intra-operative brachytherapy and 1 patient treated with electron beam radiotherapy were excluded. Thus, 48 patients were included for assessment of acute and late toxicities, response evaluation at 3 months post Re-RT, and analyses of locoregional control (LRC) and survival. Thirty-six of the 48 patients had unresectable/inoperable disease, and underwent definitive Re-RT. The remaining 12 patients underwent adjuvant Re-RT in view of the presence of features such as pT3/pT4, positive resection margin, and nodal positivity. Concurrent chemotherapy with weekly Cisplatin 40 mg/m2 was given to patients with positive surgical margin or extranodal extension.

2.3. Re-irradiation delivery

All patients underwent Re-RT with IMRT technique. A limited margin of 1–1.5 cm was given around the gross tumor volume (GTV), truncated from bone and air in unresectable disease cases or tumor bed in resectable cases to create a clinical target volume (CTV). A 3–5 mm margin was given around the CTV to create the planning target volume (PTV). To enhance target delineation, if available, MRI or PET-CT were registered with planning computed tomography. Any regions at risk of subclinical disease beyond 1–1.5 cm were not targeted. There was no elective nodal irradiation policy. The PTV was targeted to 66 Gy for definitive Re-RT and at least 60 Gy for adjuvant Re-RT with conventional fractionation schedule (1.8–2 Gy per fraction once daily for 5 days per week).

For patients who had received their first course of RT outside of our institute by two-dimensional conventional technique (parallel-opposed laterals shrinking field technique by manual planning), it was assumed that their spinal cord and brainstem had received 44 Gy. Therefore, while planning Re-RT for these patients dose constraints given to their planning risk volume (PRV) spine and PRV brainstem was 6 Gy and 9 Gy point dose maximum, respectively. For patients who underwent their first RT at our centre and for whom record on organs at risk (OARs) doses was available, the dose constraints given to PRV spine and PRV brainstem were such that the respective cumulative doses (sum total by first RT and Re-RT) to these OARs did not exceed 50 Gy and 54 Gy, respectively. Similarly, carotid arteries were assumed to have had received 66 Gy during the first course of RT by two-dimensional technique if there was no record available. While planning Re-RT, the cumulative dose (sum total by first RT and Re-RT) to carotid arteries was kept below 120 Gy point dose maximum. All other OARs, such as parotid glands, constrictors and mandible, were given a dose constraint as low as possible, however, ensuring that PTV dose is not compromised.

2.4. End points and statistical analysis

The primary end points chosen for this study were response at 3 months after Re-RT completion, locoregional control (LRC), and overall survival (OS). Response assessment was done at 3 months of completion of Re-RT by RECIST criteria. Response was categorized as complete response (CR) when there was a complete disappearance of detectable disease both clinically and radiologically. Partial response and stable disease were grouped together and categorized as residual disease. LRC was calculated as the time from the date of Re-RT commencement to the date of local or regional recurrence. OS was calculated as the time from the date of the commencement of Re-RT to death or to the date of last follow-up. Univariate analyses for median LRC and OS were performed using Kaplan–Meier curves. Log-rank test was used for comparison between groups. Multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazard model. Acute toxicities were assessed weekly until 3 months and late toxicities were assessed beyond 3 months after completion of Re-RT using toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC).8 All statistical analyses were performed using a statistical package for the social science system (SPSS version 20, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA), and a p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All reported p values are two-tailed.

3. Results

Of the 48 patients included, 36 (75%) underwent definitive Re-RT and 12 (25%) underwent adjuvant Re-RT. Concurrent chemotherapy was administered to 30 (62.5%) patients. None of the patients required salvage surgery after receiving curative Re-RT for the residual disease. Patient and disease related characteristics at the time of initial RT and Re-RT are summarized in Table 1, Table 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Patient and disease related characteristics for first primary.

| Factors | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Median (range in months) | 60 (36–73) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 43 (89.6) |

| Female | 5 (10.4) |

| Site | |

| Oral cavity | 16 (33.3) |

| Oropharynx | 17 (35.4) |

| Larynx | 5 (10.4) |

| Hypopharynx | 8 (16.7) |

| Others | 2 (4.2) |

| T-stage | |

| T1 | 5 (10.4) |

| T2 | 17 (35.4) |

| T3 | 20 (41.7) |

| T4 | 6 (12.5) |

| N-stage | |

| N0 | 16 (33.3) |

| N1 | 19 (39.6) |

| N2a | 0 (0) |

| N2b | 1 (2.1) |

| N2c | 9 (18.7) |

| N3 | 3 (6.3) |

| Clinical stage | |

| I | 5 (10.4) |

| II | 2 (4.2) |

| III | 22 (45.8) |

| IV | 19 (39.6) |

| Treatment done | |

| Surgery followed by RTa ± CCTb | 15 (31.3) |

| CCRTc | 29 (60.4) |

| CCRT followed by Salvage surgery | 4 (8.3) |

| Technique of first RT | |

| 2Dd | 34 (70.8) |

| IMRTe | 14 (29.2) |

| Dose of RTf(Gy) – Median (range in Gy) | 66.6 (50–71.1) |

Radiotherapy.

CCT – Concurrent chemotherapy.

Concurrent chemoradiation.

Two-dimensional radiotherapy.

Intensity modulated radiotherapy.

Radiotherapy.

Table 2.

Patient and disease related characteristics of recurrent/SP malignancies.

| Factors | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Median (range in months) | 63.5 (40–78) |

| Age groups (years) | |

| ≤60 | 22 (45.8) |

| >60 | 26 (54.2) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 43 (89.6) |

| Female | 5 (10.4) |

| Progression type | |

| Recurrence | 15 (31.3) |

| Second primary | 33 (68.8) |

| Progression pattern | |

| Local | 9 (18.8) |

| Nodal | 5 (10.4) |

| Local + Nodal | 1 (2.1) |

| Second primary | 33 (68.7) |

| T-stage | |

| T0 | 5 (10.4) |

| T1 | 10 (20.8) |

| T2 | 16 (33.3) |

| T3 | 9 (18.8) |

| T4 | 8 (16.7) |

| N-stage | |

| N0 | 33 (68.7) |

| N1 | 7 (14.6) |

| N2a | 1 (2.1) |

| N2b | 5 (10.4) |

| N2c | 2 (4.2) |

| N3 | 0 (0) |

| Clinical stage | |

| I | 8 (16.7) |

| II | 10 (20.8) |

| III | 14 (29.2) |

| IV | 16 (33.3) |

| Treatment given | |

| Surgery followed by Re-RTa ± CCTb | 12 (25) |

| CCRTc | 27 (56.2) |

| Re-RTd alone | 9 (18.8) |

| Re-RT type | |

| Definitive | 36 (75) |

| Adjuvant | 12 (25) |

| Concurrent chemotherapy | |

| Given | 30 (62.5) |

| Not given | 18 (37.5) |

| Re-RTddose (Gy) | |

| Median (range in Gy) | 60.06 (40–67.56) |

| Cumulative dose (Gy) | |

| Median (range in Gy) | 126.10 (110–137.6) |

| Cumulative RTedose cut-off | |

| ≥120 Gy | 31 (64.6) |

| <120 Gy | 17 (35.4) |

| Interval between first RTeand Re-RTd | |

| Median (in months) (range) | 41.88 (12.8–156.42) |

| ≥2 years | 39 (81.3) |

| <2 years | 9 (18.8) |

Reirradiation.

Concurrent chemotherapy.

Concurrent chemoradiation.

Reirradiation.

Radiotherapy.

All patients completed the full course of Re-RT, except one who discontinued it at 40 Gy because of poor tolerance to irradiation. At 3 months after Re-RT completion, 43.8% of patients achieved a CR. The median follow-up period was 14.9 months. At the time of analysis, 18 patients (37.5%) were alive and 30 patients (62.5%) had died. Fourteen patients (29.2%) were alive without any evidence of disease, 4 (8.3%) were alive with disease, 26 (54.2%) with disease had died, and 4 (8.3%) had died without any evidence of disease.

The median LRC was 11.2 months (2.04–83.61 months), and 2-year and 5-year LRC were 41% and 21.2%, respectively as shown in Fig. 1. A univariate analysis of the prognostic factors affecting the median LRC showed a statistically significant improvement with two factors: initial surgical resection performed prior to Re-RT, and achievement of CR at 3 months after completion of Re-RT. A multivariate analysis confirmed these two factors to be significantly associated with a better median LRC as shown in Table 3.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimates for locoregional control with reirradiation for recurrent/second primary head and neck cancer.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of predictive factors for locoregional control with re-irradiation.

| Factor | Groups | Univariate |

Multivariate |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRa (CIb) | p value | HRa (CIb) | p value | ||

| Age | ≤60 years | Reference | – | ||

| >60 years | 1.07 (0.52–2.19) | 0.852 | |||

| Progression type | SPc | Reference | – | ||

| Recurrence | 1.032 (0.48–2.19) | 0.936 | |||

| Progression pattern | SP | Reference | 0.921 | ||

| Local | 0.952 (0.358–2.530) | 0.921 | |||

| Nodal | 0.854 (0.290–2.513) | 0.774 | |||

| Local + Nodal | 2.49 (0.32–19.10) | 0.380 | |||

| T Stage | T0-2 | Reference | – | ||

| T3-4 | 1.068 | 0.857 | |||

| N Stage | Absent | Reference | – | ||

| Present | 1.359 | 0.408 | |||

| Type of treatment | Surgery followed by Adjuvant Re-RTd | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| CCRTe | 2.77 (1.06–8.183) | 0.041 | 5.45 (1.50–19.80) | 0.010 | |

| Re-RT alone | 4.83 (1.44–16.17) | 0.010 | 5.95 (1.46–24.16) | 0.013 | |

| Concurrent chemotherapy | Given | Reference | – | ||

| Not given | 1.15 (0.54–2.41) | 0.711 | |||

| Interval between two RTf | ≤2 years | Reference | – | ||

| >2 years | 0.446 (0.15–1.29) | 0.402 | |||

| Re-RT dose | Continuous | 1.02 (0.93–1.07) | 0.19 | ||

| Early response | CRg | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| Residual | 9.31 (3.51–24.69) | 0.000 | 13.43 (4.41–40.92) | 0.000 | |

Hazard ratio.

Confidence interval.

Second primary.

Reirradiation.

Concurrent chemoradiation.

Radiotherapy.

Complete response.

The median OS was 28.2 months (2.04–83.61 months), and 2-year and 5-year OS were 55.9% and 21.6%, respectively as shown in Fig. 2. A univariate analysis identified 3 factors that significantly affected the median OS: initial surgical resection performed prior to Re-RT, achievement of CR at 3 months post completion of Re-RT, and at least a 2-year interval between the two courses of RT. A multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazard model revealed that only the first two factors were significantly associated with a better median OS, as shown in Table 4.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates for overall survival with reirradiation for recurrent/second primary head and neck cancer.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of predictive factors for overall survival following reirradiation.

| Factor | Groups | Univariate |

Multivariate |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRa (CIb) | p value | HRa (CIb) | p value | ||

| Age | ≤60 years | Reference | – | ||

| >60 years | 0.915 (0.44–1.88) | 0.809 | |||

| Progression type | SPc | Reference | – | ||

| Recurrence | 1.15 (0.53–2.47) | 0.715 | |||

| Progression pattern | SPc | Reference | – | ||

| Local | 0.72 (0.26–1.93) | 0.515 | |||

| Nodal | 1.01 (0.34–2.99) | 0.975 | |||

| Local + Nodal | 1.51 (0.19–11.55) | 0.689 | |||

| T Stage | T0-2 | Reference | – | ||

| T3-4 | 1.24 (0.59–2.59) | 0.567 | |||

| N Stage | Absent | Reference | – | ||

| Present | 1.40 (067–2.91) | 0.367 | |||

| Type of Treatment | Surgery followed by Adjuvant Re-RTd | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| CCRTe | 2.85 (1.12–9.67) | 0.033 | 3.14 (1.04–10.82) | 0.030 | |

| Re-RTf alone | 5.45 (1.43–20.71) | 0.013 | 4.78 (1.14–20.08) | 0.032 | |

| Concurrent Chemotherapy | Given | Reference | – | ||

| Not given | 1.31 (0.60–2.84) | 0.495 | |||

| Interval between two RTg | ≤2 years | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| >2 years | 0.364 (0.12–1.04) | 0.050 | 0.491 (0.16–1.50) | 0.213 | |

| Re-RT Dose | Continuous | 1.03 (0.98–1.05) | 0.121 | ||

| Early response | CRh | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| Residual | 8.19 (2.84–23.66) | 0.000 | 8.66 (2.93–25.61) | 0.000 | |

Hazard ratio.

Confidence interval.

Second primary.

Reirradiation.

Concurrent chemoradiation.

Re-irradiation.

Radiotherapy.

Complete response.

Acute toxicity reports showed that no patients developed grade 5 toxicity, 2 developed grade 4 acute toxicity, one discontinued Re-RT because of severe mucositis, and 16 developed grade ≥3 acute toxicity. Late toxicity assessment showed 19 patients (39.5%) developed grade ≥3 toxicity, 7 (14.5%) developed grade 4 toxicity, and none developed grade 5 toxicity. Two patients developed severe osteoradionecrosis and none developed catastrophic events such as carotid blow out. Acute and late toxicities are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Acute and late toxicities with re-irradiation.

| Toxicity type | No. of patients by grade |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade ≥3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | |

| Acute toxicity | |||

| Mucositis | 11 | 2 | 0 |

| Dermatitis | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Taste | 8 | 1 | 0 |

| Late toxicity | |||

| Dysphagia | 9 | 2 | 0 |

| Xerostomia | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Neck fibrosis | 9 | 2 | 0 |

| Loss of taste | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Pharyngeal stricture/stenosis | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Laryngeal edema | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| Trismus | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| Osteoradionecrosis | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Carotid blow out | 0 | 0 | 0 |

4. Discussion

The 1980s and 1990s witnessed many single institutional studies which consistently showed poor 2-year OS rates for recurrent HNC with Re-RT varying from 19% to 33%.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Four prospective studies failed to show any improvement in survival despite the usage of higher doses of Re-RT in conventional fractionation or altered fractionation schedules in combination with concurrent chemotherapy.9, 10, 11, 12 The addition of concurrent chemotherapy to Re-RT or altered fractionation schedules of Re-RT did not seem to improve the survival in these patients.13, 14

IMRT creates a conformal dose distribution around the target and creates a steep dose gradient outside the target, which limits the doses to OARs, making IMRT suitable for Re-RT. Lee et al. were the first to show an improved 2-year locoregional progression-free survival using IMRT compared with conventional techniques (52% vs. 20%).15 The outcomes of Re-RT with IMRT have been impressive, with 2-year LRC and OS rates ranging from 27 to 67% and 31 to 58%, respectively.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Studies have delivered Re-RT doses ranging from 60 to 69 Gy in various fractionation schedules. One of the main benefits of IMRT is its ability to deliver high doses to the gross disease while sparing the normal surrounding OARs.

The survival outcomes reported in our study are consistent with those previously published. One characteristic feature of our study was the stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria to study the profiles of patients who commonly presented with locally recurrent/SP HNC at our clinic. Although the LRC rates observed by us are comparable with those observed in other IMRT studies, we found a relatively higher OS rate (2-year rate = 55.9%) compared with those studies. The most likely explanation for this is the zero incidence of grade 5 toxicity in our study. Other factors that may have contributed to a better OS are inclusion of favorable sites and squamous only histology (sarcoma and melanoma excluded), minimum 1-year time interval between the first and Re-RT, and exclusion of patients with a poor performance status.

Several prognostic factors that affect the survival and/or tumor control have been evaluated using either univariate and/or multivariate analyses. These factors help to predict patient responses and establish appropriate selection criteria of patients for Re-RT. These factors include age,15, 17, 24, 25, 26 gender,17, 22, 23 type of second event (recurrent vs. SP),24, 28 site of recurrent/SP tumor,15, 18, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 28 stage of recurrent disease,18, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 29 time interval between the initial RT and Re-RT,22, 23, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 technique of Re-RT (IMRT vs. non-IMRT),15, 22 dose of Re-RT,13, 15, 22, 23, 29, 30, 31, 32 cumulative radiation dose (sum of initial RT and Re-RT),17, 28 prior surgical resection of recurrent/SP,15, 28 addition of concurrent chemotherapy,15, 23, 28 performance status,22, 23, 30 comorbidities,22, 23, 29 achievement of CR after Re-RT,30 volume of overlap with previous RT field,14 the planning target volume (PTV) of Re-RT,14 and surface area of recurrent disease.14 Our study established three factors that significantly affected overall survival outcomes, these were initial surgical resection performed prior to Re-RT, achievement of CR at 3 months after Re-RT, and interval of at least 2 years between the two courses of RT.

Various agents have been evaluated as concurrent agents with Re-RT.15, 17, 18, 19, 23, 28 A study by Gustave-Roussy Institute demonstrated better long-term survival with chemotherapy when combined with Re-RT compared with Re-RT alone.14 Consistent with prior reports on IMRT,17, 18, 19, 20, 31 our study did not find any benefit of platinum-based chemotherapy as a concurrent agent with Re-RT. More than 70% of patients in our study had received concurrent platinum based chemotherapy with their first course of RT and 62.5% patients during Re-RT. We feel that tumors that have recurred after platinum based concurrent chemotherapy may be more resistant to the same drug, hence retreatment with a similar drug have not provided any benefit in outcomes.

Recurrence of previously irradiated tumors increases the likelihood of radiation-resistant clones. Therefore, to achieve the desired tumoricidal effect and subsequent cure, it is necessary to deliver sufficiently higher doses of radiation whilst keeping side effects to an acceptable level. Many investigators have used various Re-RT doses depending upon the type of fractionation protocols used (conventional fractionation, hyperfractionation, accelerated fractionation, etc.), the type of technique used (non-IMRT, IMRT), and end points selected. In the pre-IMRT era, the delivered dose of Re-RT ranged from 40 to 60 Gy. Several studies have reported Re-RT doses above 46 Gy,31 50 Gy,29, 30, 32 58 Gy,13, 34 and 60 Gy9, 12, 24, 33 as predictors of response rates and survival outcomes in univariate or multivariate analyses. It has been possible to achieve dose escalation for Re-RT using IMRT as shown by various single institutional studies where the majority of patients received higher median doses of Re-RT including 59.4 Gy,15, 22 60 Gy,16, 17, 20, 35, 36 66 Gy,23 68 Gy,19 and 69 Gy.18, 21 In our study the median dose delivered was 60.1 Gy. The inability to deliver higher doses in our study may be due to two factors. First, 70% of patients had undergone conventional RT as their initial treatment which may have caused a problem in achieving spinal cord tolerance during Re-RT. Second, 25% of patients were given Re-RT as an adjuvant therapy in which the surgical bed, in the absence of negative margins and extracapsular extension, requires no more than 60 Gy.

Patients undergoing Re-RT are at risk of developing any or all of the known radiotherapy related complications including acute and chronic dysphagia, soft tissue necrosis/osteoradionecrosis, trismus/fibrosis, and carotid blow out. In the pre-IMRT era the incidence of grade 5 toxicities varied from 3.5 to 11%.9, 12, 13, 14, 24, 25 The incidence of grade 3–4 complications with Re-RT has not changed considerably despite the introduction of IMRT; the incidence varies from 10 to 40%.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 22, 23 However, in the IMRT era, the decrease in the incidence of grade 5 treatment related toxicity is notable. Our current study reported similar trend of toxicity as seen in various IMRT series. Notably, none of the patients developed grade 5 toxicities.

Not all cases of unresectable recurrent/SP HNC are candidates for Re-RT. In our experience we have found it easier to deliver Re-RT for patients who have received the first course of RT at our centre, because in these cases we could use complete details of their initial treatment and treatment squeal for safe delivery of Re-RT. Various well established factors are now known which can be utilized for case selection for this technically challenging treatment. Patients with a good performance status, no comorbidities, having a long gap between the first RT and Re-RT (atleast 1-year) and not having had severe toxicity with the first RT are the most suitable candidates for Re-RT.

Homogeneity in the use of dose fractionation used for Re-RT, concurrent chemotherapy regimen delivered, and stringent selection criteria including those patients cohort who commonly present in our daily practice for Re-RT are strengths of our study. Retrospective data collection and possible biases associated with it, and relatively small sample size are the limitations of this study.

5. Conclusion

Re-RT for the treatment of recurrent/SP HNC is feasible and effective, with acceptable toxicity. However, clinical judgment and careful patient selection criteria are highly important for safe delivery of Re-RT.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Financial disclosure

None declared.

References

- 1.Bourhis J., Le Maître A., Baujat B. Individual patients’ data meta-analyses in head and neck cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19:188. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3280f01010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernier J., Domenge C., Ozsahin M. Postoperative irradiation with or without concomitant chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1945. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper J.S., Pajak T.F., Forastiere A.A. Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1937. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim S.Y., Roh J.L., Yeo N.K. Combined 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography and computed tomography as a primary screening method for detecting second primary cancers and distant metastases in patients with head and neck cancer. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1698. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee D.H., Roh J.L., Baek S. Second cancer incidence, risk factor, and specific mortality in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149(4):579–586. doi: 10.1177/0194599813496373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodwin W.J., Jr. Salvage surgery for patients with recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: when do the ends justify the means? Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1–18. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200003001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kostrzewa J.P., Lancaster W.P., Iseli T.A., Desmond R.A., Carroll W.R., Rosenthal E.L. Outcomes of salvage surgery with free flap reconstruction for recurrent oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:267–272. doi: 10.1002/lary.20743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox J.D., Stetz J., Pajak TF: Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31(5):1341–1346. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00060-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langlois D., Eschwege F., Kramar A. Reirradiation of head and neck cancers. Presentation of 35 cases treated at the Gustave Roussy Institute. Radiother Oncol. 1985;3:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(85)80006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emami B., Bignardi M., Spector G.J., Devineni V.R., Hederman M.A. Reirradiation of recurrent head and neck cancers. Laryngoscope. 1987;97:85–88. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198701000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levendag P.C., Meeuwis C.A., Visser A.G. Reirradiation of recurrent head and neck cancers: external and/or interstitial radiation therapy. Radiother Oncol. 1992;23:6–15. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(92)90299-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevens K.R., Jr., Britsch A., Moss W.T. High-dose reirradiation of head and neck cancer with curative intent. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;29:687–698. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90555-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haraf D.J., Weichselbaum R.R., Vokes E.E. Re-irradiation with concomitant chemotherapy of unresectable recurrent head and neck cancer: a potentially curable disease. Ann Oncol. 1996;7:913–918. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a010793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Crevoisier R., Bourhis J., Domenge C. Full-dose reirradiation for unresectable head and neck carcinoma: experience at the Gustave-Roussy Institute in a series of 169 patients. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3556–3562. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.11.3556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee N., Chan K., Bekelman J.E. Salvage re-irradiation for recurrent head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:731–740. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biagioli M.C., Harvey M., Roman E. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy with concurrent chemotherapy for previously irradiated, recurrent head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:1067–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sulman E.P., Schwartz D.L., Le T.T. IMRT reirradiation of head and neck cancer-disease control and morbidity outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duprez F., Madani I., Bonte K. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy for recurrent and second primary head and neck cancer in previously irradiated territory. Radiother Oncol. 2009;93:563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Popovtzer A., Gluck I., Chepeha D.B. The pattern of failure after reirradiation of recurrent squamous cell head and neck cancer: implications for defining the targets. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:1342–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sher D.J., Haddad R.I., Norris C.M., Jr. Efficacy and toxicity of reirradiation using intensity-modulated radiotherapy for recurrent or second primary head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2010;116(20):4761–4768. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duprez F., Berwots D., Madani I. High-dose reirradiation with intensity-modulated radiotherapy for recurrent head-and-neck cancer: disease control, survival and toxicity. Radiother Oncol. 2014;111(3):388–392. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riaz N., Hong J.C., Sherman E.J. A nomogram to predict loco-regional control after re-irradiation for head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2014;111:382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takiar V., Garden A.S., Ma D. Reirradiation of Head and Neck Cancers With Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy: Outcomes and Analyses. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;95(4):1117–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spencer S.A., Harris J., Wheeler R.H. RTOG 96-10: reirradiation with concurrent hydroxyurea and 5-fluorouracil in patients with squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51:1299–1304. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01745-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langer C.J., Harris J., Horwitz E.M. Phase II study of low-dose paclitaxel and cisplatin in combination with split-course concomitant twice-daily reirradiation in recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: results of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Protocol 9911. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4800–4805. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grossman C.E., Mick R., Langer C.J. Prognostic nomograms for toxicity and survival after head and neck cancer reirradiation and chemotherapy: A secondary analysis of RTOG 9610 and 9911. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90:S101. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mallick S., Gandhi A.K., Joshi N.P. Re-irradiation in head and neck cancers: an Indian tertiary cancer centre experience. J Laryngol Otol. 2014;128(11):996–1002. doi: 10.1017/S0022215114002497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoebers F., Heemsbergen W., Moor S. Reirradiation for head-and-neck cancer: delicate balance between effectiveness and toxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(3):e111–e118. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanvetyanon T., Padhya T., McCaffrey J. Prognostic factors for survival after salvage reirradiation of head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1983–1991. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schaefer U., Micke O., Schueller P. Recurrent head and neck cancer: retreatment of previously irradiated areas with combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy-results of a prospective study. Radiology. 2000;216:371–376. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.2.r00au04371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janssen S., Baumgartner M., Bremer M. Re-irradiation of head and neck cancer-impact of total dose on outcome. Anticancer Res. 2010;30(9):3781–3786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salama J.K., Vokes E.E., Chmura S.J. Long-term outcome of concurrent chemotherapy and reirradiation for recurrent and second primary head-and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:382–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langendijk J.A., Kasperts N., Leemans C.R., Doornaert P., Slotman B.J. A phase II study of primary reirradiation in squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck. Radiother Oncol. 2006;78:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chopra S., Gupta T., Agarwal J.P. Re-irradiation in the management of isolated neck recurrences: Current status and recommendations. Radiother Oncol. 2006;81:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kharofa J., Choong N., Wang D. Continuous-course reirradiation with concurrent carboplatin and paclitaxel for locally recurrent, nonmetastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head-and-neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:690–695. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.06.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zygogianni A., Kyrgias G., Kouvaris J. Re-irradiation in Head & Neck cases using IMRT technique: a retrospective study with toxicity and survival report. Head Neck Oncol. 2012;23(4):78. [Google Scholar]