Abstract

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is most commonly seen in immunocompromised patients. Besides, skin lesions may also develop due to invasive aspergillosis in those patients. A 49-year-old male patient was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia. The patient developed bullous and zosteriform lesions on the skin after the 21st day of hospitalization. The skin biopsy showed hyphae. Disseminated skin aspergillosis was diagnosed to the patient. Voricanazole treatment was initiated. The patient was discharged once the lesions started to disappear.

Key words: Invasive aspergillosis, disseminated skin invasion, leukemia

Competing interest statement

Conflict of interest: the authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Introduction

The term aspergillosis may refer to illness due to lung invasion, allergy, extrapulmonary dissemination, or cutaneous infection caused by species of Aspergillus. Invasive aspergillosis is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in immuno-compromised patients. Despite early diagnosis and treatment, invasive aspergillosis could be mortal.1-5 Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is most commonly seen in immuno-compromised patients. The diagnosis is made by demonstration of fungi in the tissue.2-4 Invasive aspergillosis could be diagnosed by skin biopsy in suspected patients with common skin lesions such as reported in this article.

Case Report

A 49-year-old male patient was admitted to hematology inpatient to receive FLAG (fludarabine, cytarabine) re-induction chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Labaratory values revealed Hb: 10.1 g/dL, white blood cell count (WBC): 1010/µL (6% neutrophil, 22.1% lymphocyte), platelet count: 45,000/µL. The patient had fever on the 9th day of hospitalization. The patient’s urine and blood cultures were obtained. The patient had febrile neutropenia. Cefoperazone-sulbactam intravenous (IV) treatment was started empirically due to febril neutropenia. Vancomycin was then added to the treatment of the patient due to perianal complaints. The patient’s fever fell at the 48th hour of the treatment. There were no bacterial growth in the blood, urine or stool cultures. Vancomycin and cefoperazone-sulbactam treatments were stopped on the 10th day of the treatment. Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax revealed pleural effusion in the right hemithorax and 31×21 mm sized hyperdense infiltration in the left lobe. Blood galactomannan antigen was found as negative.

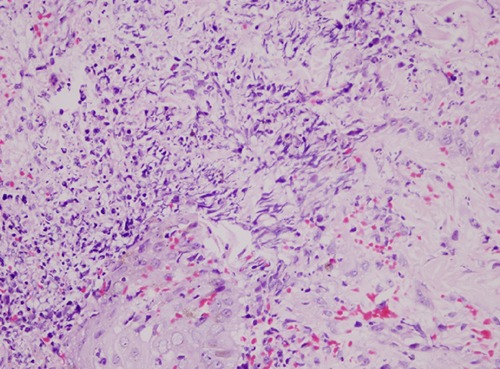

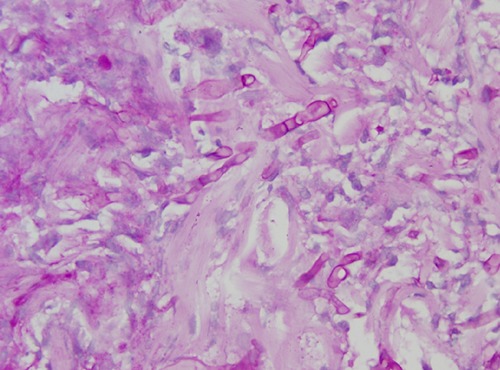

The patient had fever again on the 18th day of hospitalization. Blood, urine and sputum cultures were obtained. Hb: 8.7 g/dL, WBC: 40/µL (40% neutrophil, 28.1% lymphocyte), platelet: 17000/µL, C-reactive protein (CRP): 130 g/dL, CMV-DNA and galactomannan antigen were negative. In this second febrile neutropenia attack, meropenem 3×1 gr IV and vancomycin 2×1 gr IV treatments were empirically started. Due to continue fever, amphotericin B 5 mg/kg/day IV was also empirically started on the 5th day of the second febrile neutropenia attack. Tuberculosis culture, fungal and bacterial cultures were then obtained from the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) sample. Acid resistant bacteria (ARB) staining, tuberculosis real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, aspergillus real time PCR test and galactomannan antigen searching were also done from the BAL sample. Galactomannan level was found to have positive value of 1.27 ng/mL in the BAL specimen. Paranasal sinus CT revealed normal findings. Bullous and zosteriform lesions developed on different areas of the skin on the 21st day of hospitalization (Figures 1-3). The lesions were more common on the lower extremities. Biopsy was taken and sent to pathology. Only small amount of tissue biopsy could be obtained, because of thrombocytopenia. So that, the biopsy specimen was not enough to be sent for culture. Pathological examination of the skin biopsy revealed intensive neutrophil and non-branching fungal hyphae infiltration in the dermis (Figures 4 and 5). Fungal infiltration also seemed to invade the vessels on pathological examination (Figures 4 and 5). Disseminated skin aspergillosis was diagnosed. Voriconazole 2×360 mg IV loading dose and 2×240 mg IV maintanance dose treatments were started, because disseminated aspergillus infection occured under amphotericin B treatment. On the third day of treatment, the patient’s fever decreased. Extremity MRI revealed also newly developed mass which was clinically suitable with fungal infection in both crural regions. The blood level of galactomannan antigen decreased to 0.52 ng/mL under voriconazole treatment. The lesions were decreased and new lesions did not further develop on the skin. Meropenem and vancomycin treatments were stopped on the 14th day of treatment. Lastly, bone marrow aspiration analysis showed no remission after the second induction chemotherapy and cloforabine chemotherapy was planned to use for the patient as the third line induction chemotherapy. Voriconazole treatment dose was changed to 2×200 mg oral dose on the 15th day of the treatment and then the patient was discharged.

Figure 1.

Zosteriform scatris on the skin of the patient with acute myelogenous leukemia during the febrile neutropenia attack.

Figure 2.

Bullous lesions on the skin of the patient with acute myelogenous leukemia during the febrile neutropenia attack.

Figure 3.

Zosteriform scatris with erythematous halo on the skin of the patient with acute myelogenous leukemia during the febrile neutropenia attack.

Figure 4.

Histological findings of invasive cutaneous aspergillosis. Skin biopsy showing fungal hyphae accumulated in the dermiş.

Figure 5.

Non-branching fungal hyphae and intensive neutrophil infiltration in the dermis. Fungal infiltration also seemed to invade the vessels.

Discussion

Aspergillus is a mold which found in nature. It can also cause infection in tissues other than lung. Invasive aspergillosis is seen in immuno-compromised patients, especially in those who had long-term neutropenia.1,2 The spores released from the cones of Aspergillus mold are found in the surroundings. Cutaneous aspergillosis may develop by direct inoculation in the presence of trauma or by spreading through the secondary neighborhood or blood.

The first step for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis could be the non-invasive methods, such as serum biomarkers like galactomannan and beta-D-glucan assays. BAL and/or sputum samples could also be analysed initially. If BAL is obtained, the sample should also be sent for galactomannan antigen detection.5,6 The galactomannan antigen is a polysaccharide in the cell wall of Aspergillus. With methods such as enzyme immunoassay (EIA), this antigen can be detected in serum and/or BAL fluid. In this case, galactomannan antigen in BAL was found to be positive; but the galactomannan antigen in serum was found to be negative. Imaging is also a major and important step at the diagnosis. Thorax CT is useful for the diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Besides, imaging findings associated with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis such as nodules with surrounding hypoattenuation might also be seen in other angioinvasive pulmonary infections. In cases of suspected invasive aspergillosis, the need for thorough investigation including serum galactomannan testing and CT scan cannot be overemphasised.7 Bernardeschi et al. reported cutaneous involvement rate of invasive aspergillosis as at least 1% in 1410 cases.8 And D’Antonio et al. reported cutaneous involvement rate as 4%.9

Voriconazole is recommended as the primary drug in the treatment of invasive aspergillosis.10 Disseminated aspergillosis developed under amphotericin B treatment in our case, so that voriconazole 2×360 mg IV loading dose followed by 2×240 mg IV maintanance dose treatments were administered. The lesions were then decreased, and new lesions did not occur on the skin.

Conclusions

In conclusion, skin lesions developed in leukemia patients under chemotherapy could need to be evaluated histopathologically and microbiologically. Skin involvement of fungal infections should also be kept in mind in such lesions.

References

- 1.Schwartz S, Thiel E. Clinical presentation of invasive aspergillosis. Mycoses 1997;40:S21-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh TJ. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with neoplastic diseases. Semin Respir Infect 1990;5:111-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin SJ, Schranz J, Teutsch SM. Aspergillosis case-fatality rate: systematic review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:358-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Burik JA, Colven R, Spach DH. Cutaneous aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol 1998;36:3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shannon VR, Andersson BS, Lei X, et al. Utility of early versus late fiberoptic bronchoscopy in the evaluation of new pulmonary infiltrates following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010;45:647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sampsonas F, Kontoyiannis DP, Dickey BF, Evans SE. Performance of a standardized bronchoalveolar lavage protocol in a comprehensive cancer center: a prospective 2-year study. Cancer 2011;117:3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agrawal S, Hope W, Sinkó J, Kibbler C. Optimizing management of invasive mould diseases. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011;66:i45-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernardeschi C, Foulet F, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, et al. Cutaneous ınvasive aspergillosis: retrospective multicenter study of the french ınvasive-aspergillosis registry and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Antonio D, Pagano L, Girmenia C, et al. Cutaneous aspergillosis in patients with haematological malignancies. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect 2000;19:362-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walsh TJ, Anaissie EJ, Denning DW, et al. Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice guidlines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:327-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]