Abstract

Objective

Individuals with co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance use disorder (SUD) report heightened levels of numerous risky and health-compromising behaviors, including aggressive behaviors. Given evidence that aggressive behavior is associated with negative SUD treatment outcomes, research is needed to identify the factors that may account for the association between PTSD and aggressive behavior among patients with SUD. Thus, the goal of this study was to examine the role of impulsivity dimensions (i.e., negative urgency, lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance, and sensation seeking) in the relations between probable PTSD status and both verbal and physical aggression.

Methods

Participants were 92 patients in residential SUD treatment (75% male; 59% African American; M age = 40.25) who completed self-report questionnaires.

Results

Patients with co-occurring PTSD-SUD (vs. SUD alone) reported significantly greater verbal and physical aggression as well as higher levels of negative urgency and lack of premeditation. Lack of premeditation and lack of perseverance were significantly positively associated with verbal aggression, whereas negative urgency, lack of premeditation, and lack of perseverance were significantly positively associated with physical aggression. The indirect relation of probable PTSD status to physical aggression through negative urgency was significant.

Conclusions

Results highlight the potential utility of incorporating skills focused on controlling impulsive behaviors in the context of negative emotional arousal in interventions for physical aggression among patients with co-occurring PTSD-SUD.

Keywords: Posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorder, impulsivity, aggressive behavior, verbal aggression, physical aggression

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is characterized by symptoms of intrusion, avoidance, alternations in cognition/mood, and arousal/reactivity following direct or indirect exposure to a traumatic event (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Whereas 8–14% of the general population will meet criteria for PTSD at some point in their lifetime (e.g., Breslau et al., 1998; Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995), heightened rates of PTSD have been found among patients with substance use disorder (SUD), with approximately 36–50% of individuals seeking treatment for a SUD meeting criteria for lifetime PTSD (see Brady, Back, & Coffey, 2004 for a review). Co-occurring PTSD-SUD (vs. SUD alone) has been associated with a range of negative SUD outcomes, including quicker relapse and more severe substance use (e.g., Brown, Stout, & Mueller, 1996) and functional impairment (e.g., Ouimette, Finney, & Moos, 1999) following treatment. Further, individuals with co-occurring PTSD-SUD report greater engagement in risky, self-destructive, and health-compromising behaviors than those with SUD (e.g., Weiss, Tull, Viana, Anestis, & Gratz, 2012) or PTSD (e.g., Weiss, Duke, & Sullivan, 2015) alone.

One such behavior that may be particularly relevant to examine among individuals with co-occurring PTSD-SUD is aggressive behavior. Although rates of aggressive behaviors are elevated among populations with SUD (relative to the general population; e.g., Chermack, Fuller, & Blow, 2000; Murray et al., 2008), the presence of co-occurring mental health disorders in general (e.g., Boles & Johnson, 2001), and PTSD in particular (e.g., Eggleston et al., 2009; Parrott et al., 2003), has been found to exacerbate aggressive behavior among individuals with SUD. Several theories have been proposed to explain the association between PTSD and aggressive behavior. According to the survival mode theory, PTSD may increase the risk for aggressive behavior by diminishing the threshold for perceiving situations as threatening, which initiates a biologically prepared response to threat that may induce anger reactions (Chemtob, Novaco, Hamada, Gross, & Smith, 1997). Alternatively, the fear avoidance theory posits that aggressive behavior may function as an avoidant coping mechanism, attenuating trauma-related fear among individuals with PTSD (e.g., Riggs, Dancu, Gershuny, Greenberg, & Foa, 1992). Specifically, because anger may be experienced as less distressing and more tolerable than the more vulnerable emotion of fear, individuals with PTSD may use anger to avoid processing fear.

Consistent with these theories, individuals with (vs. without) PTSD report significantly greater aggressive behavior in general (e.g., Begić & Jokić-Begić, 2001; McFall, Fontana, Raskind, & Rosenheck, 1999) and in specific situational contexts (e.g., antisocial behaviors, partner violence; Booth-Kewley et al., 2010; Teten et al., 2010). Indeed, meta-analyses provide support for a medium to large effect of PTSD on verbal and physical aggression (Orth & Wieland, 2006; Olatunji, Ciesielski, & Tolin, 2010) – an effect that is stronger than for other anxiety disorders (Olatunji et al., 2010). Moreover, research provides support for potential additive effects of co-occurring PTSD-SUD on aggressive behavior. For instance, Parrott et al. (2003) found higher rates of aggressive behaviors toward intimate partners among individuals with co-occurring PTSD-SUD compared to individuals with SUD or PTSD alone. Likewise, Eggleston et al. (2009) found that individuals with co-occurring PTSD-SUD reported more difficulties controlling violent behavior than individuals with SUD alone or those with SUD and a co-occurring mental health disorder other than PTSD. Notably, however, despite theoretical and empirical literature linking co-occurring PTSD-SUD to aggressive behavior, no studies have examined the factors that may account for the PTSD-aggressive behavior relation among individuals with SUD.

One factor that warrants investigation in this regard is impulsivity. As defined here, impulsivity is a multi-dimensional construct involving: (a) negative urgency (the tendency to act impulsively when experiencing negative emotions); (b) lack of premeditation (a failure to reflect on the consequences of a behavior); (c) lack of perseverance (an inability to focus or follow through on difficult or boring tasks); and (d) sensation seeking (the tendency to enjoy and pursue activities that are new or exciting; Whiteside, Lynam, Miller, & Reynolds, 2005). Although research suggests heightened levels of most of these impulsivity dimensions among individuals with versus without both SUD (e.g., Verdejo-García, Bechara, Recknor, & Pérez-García, 2007) and PTSD (e.g., Joseph, Dalgleish, Thrasher, & Yule, 1997; Kotler, Iancu, Efroni, & Amir, 2001), only negative urgency has been found to be significantly elevated among patients with co-occurring PTSD-SUD versus SUD alone (Weiss, Tull, Anestis, & Gratz, 2013). Notably, this same dimension of impulsivity has also been found to be particularly relevant to aggressive behavior (e.g., Derefinko, DeWall, Metze, Walsh, & Lynam, 2011; Hecht & Latzman, 2015; Miller, Zeichner, & Wilson, 2012). For example, Derefinko and colleagues (2011) found that negative urgency is the dimension of impulsivity most closely related to aggressive behaviors toward intimate partners. Likewise, Hecht and Latzman (2015) found that negative urgency was the only dimension of impulsivity uniquely related to both reactive aggression (i.e., aggression in response to provocation) and proactive aggression (i.e., planned aggression to achieve a secondary goal). Finally, whereas Miller and colleagues (2012) found that both negative urgency and sensation seeking were uniquely related to reactive aggression, only negative urgency was also uniquely related to relational aggression. Together, this research suggests that negative urgency may explain the relation between PTSD and aggressive behavior among individuals with SUD.

Thus, the goal of the present study was to extend extant research on aggressive behavior among individuals with co-occurring PTSD-SUD by examining the roles of specific impulsivity dimensions (i.e., negative urgency, lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance, sensation seeking) in the previously demonstrated relation between PTSD and aggressive behavior among patients with SUD. Specifically, in a sample of patients with SUD, we examined the relations among (a) PTSD and both verbal and physical aggression, (b) PTSD and impulsivity dimensions, (c) impulsivity dimensions and both verbal and physical aggression, and (d) PTSD, impulsivity dimensions, and verbal and physical aggression. Consistent with past research, we expected that patients with co-occurring PTSD-SUD (vs. SUD alone) would report greater verbal and physical aggression (e.g., Eggleston et al., 2009; Parrott et al., 2003), as well as higher levels of negative urgency (e.g., Weiss, Tull, Anestis, et al., 2013). We also expected that each of the impulsivity dimensions would be significantly positively associated with verbal and physical aggression (e.g., Verdejo-García et al., 2007). Finally, extending prior research, we expected that negative urgency (but not lack of premeditation, and lack of perseverance, or sensation seeking) would mediate the relations between probable PTSD status and verbal and physical aggression. Given evidence that aggressive behavior contributes to SUD treatment dropout (Patkar et al., 2004), knowing the factors that increase risk for aggressive behavior among patients with SUD and elevated PTSD pathology may highlight potential targets for intervention to improve SUD treatment outcomes.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were 92 patients in a residential SUD treatment facility in central Mississippi. Participants were predominantly male (n = 69, 75.0%) and ranged in age from 19 to 61 (M age = 40.25, SD = 9.67). In terms of racial/ethnic background, 58.7% of the participants self-identified as African American, 39.1% as White, and 2.2% as another race/ethnicity. Most participants were unemployed (78.3%), reported an annual income under $10,000 (60.9%), and had no higher than a high school education (62.0%). Regarding participants’ primary drug of choice, 43.7% reported cocaine, 28.2% reported alcohol, 14.6% reported marijuana, 7.8% reported opioids, 4.9% reported methamphetamine, and 1.0% reported benzodiazepines.

2.2. Measures

The Life Events Checklist (LEC; Gray, Litz, Hsu, & Lombardo, 2004) is a self-report measure that assesses exposure to 17 potentially traumatic events. The LEC has demonstrated convergent validity with measures assessing varying levels of exposure to potentially traumatic events and psychopathology known to relate to traumatic exposure (Gray et al., 2004).

The PTSD Checklist – Civilian Version (PCL-C; Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993) is a 17-item self-report measure that assesses the severity of DSM-IV PTSD symptoms experienced in response to the most stressful potentially traumatic event identified on the LEC. Using a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely), participants rate the extent to which each symptom has bothered them in the past month. Consistent with Blanchard et al.’s (1996) cut-off score for civilians, a score of ≥ 44 was indicative of a probable PTSD diagnosis. The PCL-C has demonstrated strong test-retest reliability and good construct validity (Weathers et al., 1993). Internal consistency in the present sample was excellent (α = .96).

The UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale (UPPS; Whiteside et al., 2005) is a 45-item self-report measure that assesses negative urgency, lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance, and sensation seeking. Participants rate the extent to which each item applies to them on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = rarely/never true, 4 = almost always/always true). The four scales have been found to have good convergent and discriminant validity (Whiteside et al., 2005). Internal consistency of each scale in this sample was adequate (αs > .79).

The Aggression Questionnaire (AQ; Buss & Perry, 1992) is a 29-item self-report measure that assesses verbal aggression, physical aggression, anger, and hostility. The verbal and physical aggression scales measure aggressive behavior, whereas the anger and hostility scales measure the affective and cognitive components of aggression, respectively. Participants rate the extent to which each item applies to them on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = never or hardly applies to me, 5 = very often applies to me). The AQ has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties (Buss & Perry, 1992). For the purposes of the present study, analyses were only conducted with the verbal and physical aggression subscales (αs > .83).

2.3. Procedure

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Mississippi Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board. Data were collected as part of a larger study examining predictors of risk-taking and impulsive behavior in inpatients with SUD (see Weiss, Tull, Lavender, & Gratz, 2013). To be eligible for inclusion in the study, participants were required to have: (a) obtained a Mini-Mental Status Exam (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) score of ≥ 24, and (b) exhibited no current psychotic disorders (as determined by the SCID-IV; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996). They were recruited no sooner than 72 hours after entry into the facility to limit the potential interference of withdrawal symptoms on study engagement and were provided with information about study procedures and associated risks, following which written informed consent was obtained. Participants completed a series of interviews and questionnaires and received a $20 gift card as reimbursement.

2.4. Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 21 (IBM SPSS, 2012). To identify potential covariates, a series of analyses of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square and correlation analyses were conducted to examine relations among demographic characteristics and the primary study variables. Given the small number of participants in several of the race/ethnicity, income, education, and employment categories, these variables were collapsed into dichotomous variables of White (39.1%) versus non-White (60.9%), over (60.9%) versus under (39.1%) $10,000 annual income, high school diploma or less (62.0%) versus education beyond high school (38.0%), and unemployed (78.3%) versus employed (21.7%). Because inclusion of covariates significantly associated with the independent variable in non-randomized designs may remove a portion of the variance attributed to the independent variable and thus negatively affect its construct validity (Miller & Chapman, 2001), demographic variables that were significantly related to the dependent variables were only included as covariates if they were not significantly related to probable PTSD status.

Next, ANOVAs and analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were conducted to examine between-group (probable PTSD vs. no-PTSD) differences in verbal and physical aggression and impulsivity dimensions. Pearson product-moment correlations were then conducted to evaluate the relations among impulsivity dimensions and verbal and physical aggression. Finally, to examine whether impulsivity dimensions account for the relations between probable PTSD status and verbal and physical aggression, we conducted mediation analyses (see Preacher & Hayes, 2004) with the PROCESS SPSS macro (Hayes, 2013). PROCESS uses ordinary least squares regression and bootstrapping methodology, which confers more statistical power than standard approaches to statistical inference and does not reply on distributional assumptions. The bootstrap method was used to estimate the standard errors of parameter estimates and the bias-corrected confidence intervals of the indirect effects (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002; Preacher & Hayes, 2004). The mediated effect is significant if the 95% confidence interval does not contain zero (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). In this study, 5000 bootstrap samples were used to derive estimates of the indirect effect. Of note, analyses were only conducted utilizing mediator and dependent variables found to be significantly related to probable PTSD status at the bivariate level.

3. Analyses

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

Based on PCL-C data, 41.3% of participants (n = 38) met criteria for probable PTSD. Participants with (M = 56.13, SD = 11.22) versus without (M = 25.83, SD = 7.96) probable PTSD reported more severe PTSD symptoms (F [1, 90] = 229.83, p < .001). Probable PTSD status did not differ as a function of gender, race/ethnicity, income, education, or employment (X2s [1–2] < 0.85, ps > .05); however, participants with (M = 37.00, SD = 9.59) versus without (M = 42.54, SD = 9.13) probable PTSD were younger (F [1, 91] = 7.87, p = .01). Verbal and physical aggression were not related to gender, race/ethnicity, income, education, or employment (Fs [87–91] < 2.66, ps > .05); however, verbal and physical aggression were negatively correlated with age (rs = −.35 and −.23, respectively, ps < .05). Finally, impulsivity dimensions were not associated with income or employment (Fs [1, 91] = 1.86, p > .05); however, women (vs. men) reported higher negative urgency (M = 35.91, SD = 5.44; M = 31.92, SD = 6.56, respectively) and lack of premeditation (M = 25.72, SD = 5.39; M = 21.94, SD = 6.27, respectively; Fs [1, 91] ≥ 6.70, ps < .05); age was negatively associated with negative urgency, lack of premeditation, and sensation seeking (rs = −.23 to −.31, ps < .05); individuals with (M = 18.39, SD = 5.58) versus without (M = 21.18, SD = 3.94) education beyond high school reported lower levels of lack of perseverance (F [1, 91] = 7.87, p = .01); and White (M = 33.97, SD = 7.55) versus non-White (M = 29.30, SD = 6.79) participants reported higher levels of sensation seeking (F [1, 91] = 9.50, p = .003). Subsequent analyses included demographic variables associated with the dependent variables. Given differences in age as a function of probable PTSD status, this variable was not included as a covariate.

3.2. Primary Analyses

3.2.1. Associations between probable PTSD status and verbal and physical aggression

To examine between-group differences in aggressive behavior, we conducted two one-way (probable PTSD vs. non-PTSD) analyses of variance. Between-group differences were detected for verbal, F (1, 87) = 10.70, p = .002, η2 = .11, and physical, F (1, 91) = 11.92, p = .001, η2 = .12, aggression, with inpatients with SUDs with (vs. without) probable PTSD reporting greater verbal and physical aggression (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Between-group Differences in Impulsivity Dimensions and Physical and Verbal Aggression as a Function of Probable PTSD Status

| Probable PTSD (n = 38) | No-PTSD(n = 54) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | Test of Significance | |

| AQ-Physical Aggression | 23.97 (8.13) | 18.44 (7.14) | F (1, 91) = 11.92, p = .001, η2 = .12 |

| AQ-Verbal Aggression | 15.61 (4.32) | 12.40 (4.72) | F (1, 87) = 10.70, p = .002, η2 = .11 |

| UPPS-Negative Urgencya | 35.37 (5.10) | 31.19 (6.87) | F (2, 91) = 9.45, p = .003, η2 = .10 |

| UPPS-Premeditationa | 24.69 (6.24) | 21.61 (6.00) | F (2, 91) = 5.11, p = .03, η2 = .05 |

| UPPS-Perseveranceb | 21.02 (4.90) | 19.48 (4.67) | F (2, 91) = 1.62, p = .21, η2 = .02 |

| UPPS-Sensation Seekingc | 32.50 (7.74) | 30.16 (7.09) | F (2, 91) = 1.48, p = .23, η2 = .02 |

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; UPPS = UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale; AQ = Aggression Questionnaire;

Controlling for gender;

Controlling for education;

Controlling for race/ethnicity.

3.2.2. Associations between probable PTSD status and impulsivity dimensions

To examine between-group differences in impulsivity, we conducted a series of one-way (probable PTSD vs. non-PTSD) analyses of covariance. Controlling for gender, between-group differences were detected for negative urgency, F (2, 91) = 9.45, p = .003, η2 = .10, and lack of premeditation, F (2, 91) = 5.11, p = .03, η2 = .05, with inpatients with SUDs with (vs. without) probable PTSD reporting greater impulsivity in these areas (see Table 1).

3.2.3. Associations between impulsivity and verbal and physical aggression

Zero-order and partial correlations among AQ and UPPS dimensions are presented in Table 2. Verbal aggression was positively associated with lack of premeditation and lack of perseverance, and physical aggression was positively associated with negative urgency, lack of premeditation, and lack of perseverance. The strength and direction of these findings did not change when controlling for gender.

Table 2.

Descriptive Data and Intercorrelations among Impulsivity Dimensions and Physical and Verbal Aggression

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. AQ-Physical Aggression | -- | .74*** | .33** | .36*** | .28** | .14 |

| 2. AQ-Verbal Aggression | .74*** | -- | .26* | .18 | .25* | .02 |

| 3. Negative Urgency | .36*** | .14 | -- | .35** | .28** | .15 |

| 3. UPPS-Premeditation | .30** | .22* | .35** | -- | .15 | .38*** |

| 5. UPPS-Perseverance | .34** | .27* | .31* | .21* | -- | −.02 |

| 6. UPPS-Sensation Seeking | .10 | −.01 | .14 | .31** | .01 | -- |

| M | 20.73 | 13.78 | 32.91 | 22.88 | 20.12 | 31.13 |

| SD | 8.00 | 4.80 | 6.51 | 6.25 | 4.80 | 7.42 |

Note. AQ=Aggression Questionnaire; UPPS=UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale. Zero-order correlations appear above the diagonal and partial correlations covarying for gender appear below the diagonal.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

3.2.4. Role of impulsivity dimensions in the relations between probable PTSD status and both verbal and physical aggression

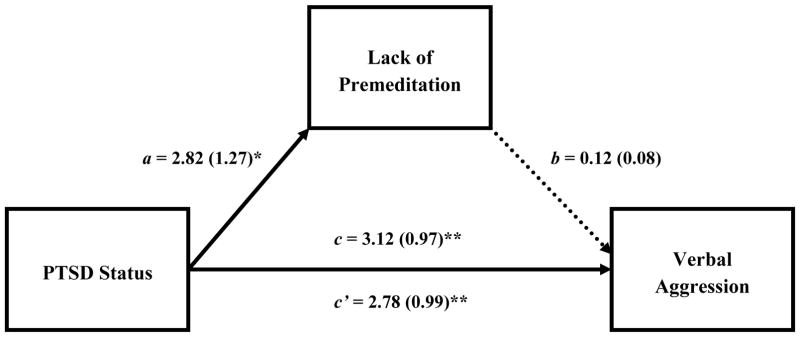

First, analyses were conducted to examine whether lack of premeditation (i.e., the only UPPS dimension associated with both probable PTSD status and verbal aggression) accounted for the relation between probable PTSD status and verbal aggression when controlling for gender. As shown in Figure 1, both the total and direct effects of probable PTSD status on verbal aggression were significant, as was the association between probable PTSD status and lack of premeditation, B = 2.82, SE = 1.27; t = 2.22, p = .03. However, the indirect effect of probable PTSD status on verbal aggression through lack of premeditation was non-significant, B = 0.34; SE = 0.35, 95% CI [−0.15–1.34].

Figure 1.

Summary of Analyses Explicating the Mediating Role of Lack of Premeditation in the Relationship between Probable PTSD Status and Verbal Aggression

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. Dashed lines indicate nonsignificant paths. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

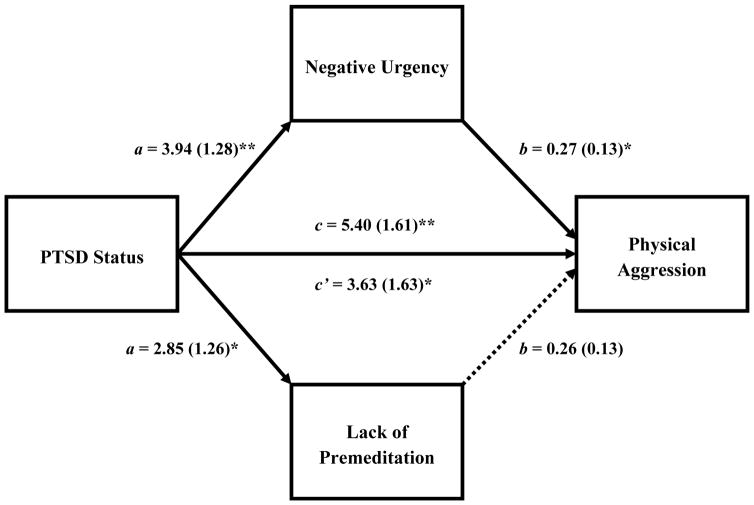

Next, analyses were conducted to examine whether negative urgency and lack of premeditation (i.e., the only UPPS dimensions associated with both probable PTSD status and physical aggression) accounted for the relation between probable PTSD status and physical aggression when controlling for gender. As shown in Figure 2, the total effect of probable PTSD status on physical aggression was significant, as were the associations of probable PTSD status with both negative urgency and lack of premeditation. Further, results revealed a significant indirect effect of probable PTSD status on physical aggression through negative urgency, B = 1.05; SE = 0.64, 95% CI [0.12–2.68], but not lack of premeditation, B = 0.73; SE = 0.61, 95% CI [−0.05–2.41].

Figure 2.

Summary of Analyses Explicating the Mediating Role of Negative Urgency and Lack of Premeditation in the Relationship between Probable PTSD Status and Physical Aggression

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. Dashed lines indicate nonsignificant paths. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

4. Discussion

This study sought to extend extant research on aggressive behavior among individuals with co-occurring PTSD-SUD by examining the roles of distinct impulsivity dimensions in the relations between probable PTSD status and verbal and physical aggression among inpatients with SUD. As expected, and consistent with past research, patients with co-occurring PTSD-SUD (vs. SUD alone) reported greater verbal and physical aggression (e.g., Eggleston et al., 2009; Parrott et al., 2003), as well as higher levels of negative urgency (e.g., Weiss, Tull, Anestis, et al., 2013). Contrary to our hypotheses, however, patients with PTSD-SUD also reported higher levels of lack of premeditation than those with SUD alone. Overall, these findings suggest that patients with PTSD-SUD are more likely to engage in aggressive behavior and exhibit difficulties both reflecting on the consequences of their behaviors in general and controlling their behaviors when experiencing negative emotions in particular.

Although none of the impulsivity dimensions accounted for the relation between probable PTSD status and verbal aggression, negative urgency accounted for a significant portion of the relation between probable PTSD status and physical aggression. These findings highlight negative urgency as one possible factor underlying the PTSD-physical aggression relation. Indeed, a growing body of theory and research suggests that aggressive behaviors in particular may be emotion-dependent, or more likely to occur in the context of intense emotions (e.g., Cyders & Smith, 2007; 2008). According to Inzlicht and Schmeichel (2012), the down-regulation of intense emotions is an effortful and not immediately rewarding process. Thus, as the need for regulation persists, individuals may begin to experience a shift in motivation from the regulation of emotion toward the acquisition of more immediately rewarding and gratifying experiences. This shift in motivation coincides with an increased allocation of attention toward cues that signal more immediate gratification and reward (vs. the need for self-regulation), increasing the likelihood of disinhibited behaviors such as verbal and physical aggression. Future research in this area may enhance our understanding of the role of negative urgency in physical aggression among patients with co-occurring PTSD-SUD.

Furthermore, given findings that (a) none of the impulsivity dimensions mediated the association between probable PTSD status and verbal aggression, and (b) the probable PTSD status-physical aggression relation remained significant when negative urgency was included in the model, future studies should examine other possible factors associated with aggressive behaviors among patients with PTSD-SUD. Two factors worth examining in this regard are emotion dysregulation and distress intolerance, both of which have been found to be associated with PTSD (e.g., Marshall-Berenz, Vujanovic, Bonn-Miller, Bernstein, & Zvolensky, 2010; Weiss, Tull, Anestis, et al., 2013) and aggressive behaviors (e.g., Brem et al., in press; Gratz, Paulson, Jakupcak, & Tull, 2009). Of note, whereas negative urgency has some overlap with emotion dysregulation and distress intolerance, there are important distinctions between these constructs. For example, whereas negative urgency overlaps with one specific dimension of emotion dysregulation (i.e., difficulties inhibiting impulsive behaviors when experiencing negative emotions; see Gratz & Roemer, 2004), emotion dysregulation is a broader, multidimensional construct focused on maladaptive ways of responding to emotions in general, including deficits in the understanding, acceptance, and effective use and modulation of emotions (Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Gratz, Moore, & Tull, 2016). Given past research linking most of these dimensions of emotion dysregulation to both PTSD (e.g., Tull, Barrett, McMillan, & Roemer, 2007; Weiss, Tull, Davis, Dehon, Fulton, & Gratz, 2012) and aggressive behavior (e.g., Shorey, Brasfield, Febres, & Stuart, 2011), research is needed to explore their role in the PTSD-aggressive behavior relation. Likewise, although negative urgency and distress intolerance both represent maladaptive ways of responding to negative affect, negative urgency focuses more specifically on externally-focused behavioral responses, whereas distress intolerance encompasses both internal and external responses, including the perceived ability to tolerate emotional distress, subjective appraisal of distress, attentional dyscontrol, and efforts to alleviate distress (see Simons & Gaher, 2005). Future investigations that focus on disentangling the roles of negative urgency versus distress intolerance more broadly in the PTSD-aggressive behavior association are warranted.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relation of the UPPS impulsivity dimensions to verbal and physical aggression among patients with SUD. Findings highlight the relevance of a lack of premeditation and lack of perseverance to verbal and physical aggression in this population. With regard to the former, findings of an association between lack of premeditation and both verbal and physical aggression suggest that the failure to reflect on the consequences of behavior relates to the tendency to engage in aggressive behavior among inpatients with SUD. Indeed, lack of premeditation has been linked to low levels of executive control (e.g., Philippe et al., 2010) and self-control (e.g., Latzman & Vaidya, 2013), both of which are heightened among patients with SUD (e.g., Miller & Brown, 1991; Verdejo-García & Pérez-García, 2007) and associated with aggressive behavior (e.g., DeWall, Baumeister, Stillman, & Gailliot, 2007; Hancock, Tapscott, & Hoaken, 2010). As for the findings of relations between lack of perseverance and both verbal and physical aggression in our sample, difficulties maintaining attention and following through on tasks (as reflected in this particular dimension of impulsivity) may lead patients with SUD to discontinue goal-directed behaviors in favor of behaviors that produce more immediate reinforcement. As such, patients with SUD and higher levels of lack of perseverance may use verbal and physical aggression because alternative, more adaptive behaviors are not sufficiently reinforced.

As for the relation of negative urgency to both verbal and physical aggression, the tendency to act impulsively when experiencing negative emotions was associated with physical but not verbal aggression in this sample. Although unexpected, this finding is consistent with research suggesting a stronger relation between emotional states and physical versus verbal aggression. For example, Vigil-Colet, Morales-Vives, and Tous (2008) found that anger was more strongly associated with physical aggression than verbal aggression. Likewise, difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when distressed has been found to be more strongly related to physical versus verbal aggression toward an intimate partner (e.g., Shorey et al., 2011). Future research is needed to better understand the potentially divergent role of negative urgency in verbal versus physical aggression. For instance, given evidence to suggest that negative urgency is largely driven by negative reinforcement (see Cyders & Smith, 2007; 2008), studies focused on clarifying the differential relevance of negative (e.g., reducuction or distraction from distress) versus positive (e.g., gratification of an urge) reinforcement to physical and verbal aggression among patients with SUD are needed. Future investigations may also benefit from exploring the motives underlying verbal and physical aggression among patients with SUD, including the extent to which they are best conceptualized as proactive (i.e., goal-directed and implemented for personal gain) versus reactive (i.e., retalitory and emotion-driven; Poulin & Boivin, 2000).

Several limitations warrant consideration. First, the cross-sectional and correlational nature of the data precludes determination of the exact nature and direction of the relations of interest. Prospective studies are needed to examine the precise relations of PTSD, impulsivity, and aggression among patients with SUD. Second, although the PCL-C demonstrates high levels of agreement with empirically-supported PTSD diagnostic interviews (Grubaugh, Elhai, Cusack, Wells, & Frueh, 2007) and the mean PCL-C score for the PTSD group in this study (56.13) was well above the civilian cutoff score (44) for a diagnosis of PTSD, future research is needed to replicate these findings in clinical populations of patients with diagnosed PTSD. Third, research is needed to replicate these findings using DSM-5 guidelines for PTSD. Fourth, following initiation of the present study, an additional dimension of impulsivity was added to the UPPS: positive urgency (the tendency to act impulsively when experiencing positive emotions; Cyders et al., 2007). Given past findings that positive urgency mediates the relation between PTSD symptoms and overall risky behaviors among patients with SUD (Weiss, Tull, Sullivan, Dixon-Gordon, & Gratz, 2015), future research would benefit from exploring the role of positive urgency and related constructs(e.g., nonacceptance of positive emotions and difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior when experiencing positive emotions; Weiss, Gratz, & Lavender, 2015) in the PTSD-aggressive behavior relation as well. Fifth, this study focused on behavioral components of aggression. Given theoretical literature suggesting that cognitive (i.e., hostility) and affective (i.e., anger) components of aggression may mediate the link between PTSD and aggressive behavior (e.g., Chemtob et al., 1997; Riggs et al., 1992), future studies should examine the ways in which anger and hostility interact with negative urgency to influence aggressive behavior among individuals with PTSD-SUD. Finally, this study utilized a small sample size of inpatients with SUD. Thus, the results of this study may not generalize to other SUD (e.g., outpatient, non-treatment-seeking) or non-SUD (e.g., patients with PTSD alone) populations and require replication in larger, more diverse samples. Despite these limitations, findings that negative urgency accounted for a significant portion of the relation between probable PTSD status and physical aggression provide suggestive evidence for the emotion-dependent nature of physical aggression among inpatients with co-occurring PTSD-SUD. These results highlight the potential utility of targeting negative urgency in interventions aimed at reducing aggressive behavior and improving treatment outcomes among inpatients with PTSD-SUD. In particular, treatments that focus on teaching patients skills for tolerating extreme emotional states without immediate action (e.g., distress tolerance skills) and maintaining goal-directed behavior in the context of negative affect (e.g., mindfulness skills) may be useful. Future research examining the effect of directly targeting negative urgency in reducing physical aggression and associated negative outcomes (e.g., SUD treatment dropout; Patkar et al., 2004) among inpatients with co-occurring PTSD-SUD is also needed.

Acknowledgments

Portions of these data were previously presented at the annual meeting of the Anxiety Disorders Association of America in 2013. The authors would like to thank Mr. Forea Ford and the former Country Oaks Recovery Center for their assistance with this project. The authors would also like to thank Sarah Anne Moore, Rachel Brooks, and Jessica Fulton for their assistance with data collection on this project.

Funding

Support for this study was provided by a contract from the Mississippi State Department of Health awarded to the third (KLG) and last (MTT) authors. The research described here was also supported, in part, by grants from the National Institutes of Health (K23DA039327; T32DA019426) awarded to the first author (NHW).

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Nicole H. Weiss, Yale University School of Medicine, 389 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, CT 06511

Kevin M. Connolly, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216, G. V. (Sonny) Montgomery VAMC, 1500 E. Woodrow Wilson Ave., Jackson, MS 39216

Kim L. Gratz, University of Toledo, 2801 W. Bancroft Street, Toledo, OH 43606

Matthew T. Tull, University of Toledo, 2801 W. Bancroft Street, Toledo, OH 43606

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Muraven M, Tice DM. Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1252–1265. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC, Vrana SR, Barefoot JC, Feldman ME, Fairbank J, Moore SD. Magnitude and duration of cardiovascular response to anger in Vietnam veterans with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:228–234. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.1.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begić D, Jokić-Begić N. Aggressive behavior in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Military Medicine. 2001;166:67–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boles SM, Johnson PB. Violence among comorbid and noncomorbid severely mentally ill adults: A pilot study. Substance Abuse. 2001;22:167–173. doi: 10.1023/A:1011172901356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth-Kewley S, Larson GE, Highfill-McRoy RM, Garland CF, Gaskin TA. Factors associated with antisocial behavior in combat veterans. Aggressive Behavior. 2010;36:330–337. doi: 10.1002/ab.20355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Back SE, Coffey SF. Substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13:206–209. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00309.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brem MJ, Khaddouma A, Elmquist J, Florimbio AR, Shorey RC, Stuart GL. Relationships among dispositional mindfulness, distress tolerance, and women’s dating violence perpetration: A path analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. doi: 10.1177/0886260516664317. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: The 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PJ, Stout RL, Mueller T. Posttraumatic stress disorder and substance abuse relapse among women: A pilot study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10:124–128. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.10.2.124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Perry M. The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:452–459. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SR, Pritchard AA, Dominelli RM. Externalizing behavior, the UPPS-P impulsive behavior scale and reward and punishment sensitivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2013;54:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.08.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chemtob CM, Novaco RW, Hamada RS, Gross DM, Smith G. Anger regulation deficits in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1997;10:17–36. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490100104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chermack ST, Fuller BE, Blow FC. Predictors of expressed partner and non-partner violence among patients in substance abuse treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;58:43–54. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:839–850. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derefinko K, DeWall CN, Metze AV, Walsh EC, Lynam DR. Do different facets of impulsivity predict different types of aggression? Aggressive Behavior. 2011;37:223–233. doi: 10.1002/ab.20387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWall CN, Baumeister RF, Stillman TF, Gailliot MT. Violence restrained: Effects of self-regulation and its depletion on aggression. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2007;43:62–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2005.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eggleston AM, Calhoun PS, Svikis DS, Tuten M, Chisolm MS, Jones HE. Suicidality, aggression, and other treatment considerations among pregnant, substance-dependent women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2009;50:415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders – Patient Edition. New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York, NY: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Moore KE, Tull MT. The role of emotion dysregulation in the presence, associated difficulties, and treatment of borderline personality disorder. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2016;7:344–353. doi: 10.1037/per0000198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Paulson A, Jakupcak M, Tull MT. Exploring the relationship between childhood maltreatment and intimate partner abuse: Gender differences in the mediating role of emotion dysregulation. Violence and Victims. 2009;24:68–82. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26:41–54. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MJ, Litz BT, Hsu JL, Lombardo TW. Psychometric properties of the Life Events Checklist. Assessment. 2004;11:330–341. doi: 10.1177/1073191104269954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubaugh AL, Elhai JD, Cusack KJ, Wells C, Frueh BC. Screening for PTSD in public-sector mental health settings: The diagnostic utility of the PTSD Checklist. Depression and Anxiety. 2007;24:124–129. doi: 10.1002/da.20226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock M, Tapscott JL, Hoaken PNS. Role of executive dysfunction in predicting frequency and severity of violence. Aggressive Behavior. 2010;36:338–349. doi: 10.1002/ab.20353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht LK, Latzman RD. Revealing the nuanced associations between facets of trait impulsivity and reactive and proactive aggression. Personality and Individual Differences. 2015;83:192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.04.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inzlicht M, Schmeichel BJ. What is ego depletion? Toward a mechanistic revision of the resource model of self-control. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2012;7:450–463. doi: 10.1177/1745691612454134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S, Dalgleish T, Thrasher S, Yule W. Impulsivity and post-traumatic stress. Personality and Individual Differences. 1997;22:279–281. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00213-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotler M, Iancu I, Efroni R, Amir M. Anger, impulsivity, social support, and suicide risk in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders. 2001;189:162–167. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200103000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latzman RD, Vaidya JG. Common and distinct associations between aggression and alcohol problems with trait disinhibition. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2013;35:186–196. doi: 10.1007/s10862-012-9330-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall-Berenz EC, Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ. Multimethod study of distress tolerance and PTSD symptom severity in a trauma-exposed community sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23:623–630. doi: 10.1002/jts.20568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFall M, Fontana A, Raskind M, Rosenheck R. Analysis of violent behavior in Vietnam combat veteran psychiatric inpatients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1999;12:501–517. doi: 10.1023/A:1024771121189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA, Chapman JP. Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:40–48. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.110.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Zeichner A, Wilson LF. Personality correlates of aggression: Evidence from measures of the five-factor model, UPPS model of impulsivity, and BIS/BAS. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27:2903–2919. doi: 10.1177/0886260512438279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Brown JM. Self-regulation as a conceptual basis for the prevention of addictive behaviours. In: Heather N, Miller WR, Greeley J, editors. Self-control and the addictive behaviours. New South Wales, Australia: Maxwell Macmillan; 1991. pp. 3–79. [Google Scholar]

- Murray RL, Chermack ST, Walton MA, Winters J, Booth BM, Blow FC. Psychological aggression, physical aggression, and injury in nonpartner relationships among men and women in treatment for substance-use disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:896–905. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Ciesielski BG, Tolin DF. Fear and loathing: A meta-analytic review of the specificity of anger in PTSD. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth U, Wieland E. Anger, hostility, and posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:698–706. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette PC, Finney JW, Moos RH. Two-year posttreatment functioning and coping of substance abuse patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13:105–114. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.13.2.105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott DJ, Drobes DJ, Saladin ME, Coffey SF, Dansky BS. Perpetration of partner violence: Effects of cocaine and alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1587–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patkar AA, Murray HW, Mannelli P, Gottheil E, Weinstein SP, Vergare MJ. Pre-treatment measures of impulsivity, aggression and sensation seeking are associated with treatment outcome for African-American cocaine-dependent patients. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2004;23:109–122. doi: 10.1300/J069v23n02_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippe G, Courvoisier DS, Billieux J, Rochat L, Schmidt RE, Van der Linden M. Can the distinction between intentional and unintentional interference control help differentiate varieties of impulsivity? Journal of Research in Personality. 2010;44:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin F, Boivin M. Reactive and proactive aggression: Evidence of a two-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12:115–122. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.12.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/BF03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Gershuny BS, Greenberg D, Foa EB. Anger and post-traumatic stress disorder in female crime victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1992;5:613–625. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490050410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seibert LA, Miller JD, Pryor LR, Reidy DE, Zeichner A. Personality and laboratory-based aggression: Comparing the predictive power of the Five-Factor Model, BIS/BAS, and impulsivity across context. Journal of Research in Personality. 2010;44:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Brasfield H, Febres J, Stuart GL. An examination of the association between difficulties with emotion regulation and dating violence perpetration. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2011;20:870–885. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2011.629342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM. The Distress Tolerance Scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Motivation and Emotion. 2005;29:83–102. doi: 10.1007/s11031-005-7955-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Moore TM, Gordon KC, Ramsey SE, Kahler CW. Psychopathology in women arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:376–389. doi: 10.1177/0886260505282888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teten AL, Schumacher JA, Taft CT, Stanley MA, Kent TA, Bailey SD, … White DL. Intimate partner aggression perpetrated and sustained by male Afghanistan, Iraq, and Vietnam veterans with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:1612–1630. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Barrett HM, McMillan ES, Roemer L. A preliminary investigation of the relationship between emotion regulation difficulties and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdejo-García A, Pérez-García M. Profile of executive deficits in cocaine and heroin polysubstance users: Common and differential effects on separate executive components. Psychopharmacology. 2007;190:517–530. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0632-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigil-Colet A, Morales-Vives F, Tous J. The relationships between functional and dysfunctional impulsivity and aggression across different samples. The Spanish Journal of Psychology. 2008;11:480–487. doi: 10.1017/S1138741600004480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies.1993. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Duke AA, Sullivan TP. Probable posttraumatic stress disorder and women’s use of aggression in intimate relationships: The moderating role of alcohol dependence. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2014;27:550–557. doi: 10.1002/jts.21960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Gratz KL, Lavender J. Factor structure and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of difficulties in the regulation of positive emotions: The DERS-Positive. Behavior Modification. 2015;39:431–453. doi: 10.1177/0145445514566504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Tull MT, Anestis MD, Gratz KL. The relative and unique contributions of emotion dysregulation and impulsivity to posttraumatic stress disorder among substance dependent inpatients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;128:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Tull MT, Davis LT, Dehon EE, Fulton JJ, Gratz KL. Examining the association between emotion regulation difficulties and probable posttraumatic stress disorder within a sample of African Americans. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2012;41:5–14. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.621970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Tull MT, Lavender J, Gratz KL. Role of emotion dysregulation in the relationship between childhood abuse and probable PTSD in a sample of substance abusers. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37:944–954. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Tull MT, Sullivan TP, Dixon-Gordon KL, Gratz KL. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and risky behaviors among trauma-exposed inpatients with substance dependence: The influence of negative and positive urgency. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;155:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.07.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Tull MT, Viana AG, Anestis MD, Gratz KL. Impulsive behaviors as an emotion regulation strategy: Examining associations between PTSD, emotion dysregulation, and impulsive behaviors among substance dependent inpatients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2012;26:453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.01.007. Impulsive behaviors as an emotion regulation strategy: Examining associations between PTSD, emotion dysregulation, and impulsive behaviors among substance dependent inpatients. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Reynolds SK. Validation of the UPPS Impulsive Behaviour Scale: A four-factor model of impulsivity. European Journal of Personality. 2005;19:559–574. doi: 10.1002/per.556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]