Abstract

High mortality rates from invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised patients are prompting research toward improved antifungal therapy and better understanding of fungal physiology. Herein we show that Aspergillus fumigatus, the major pathogen in aspergillosis, imports exogenous cholesterol under aerobic conditions and thus compromises the antifungal potency of sterol biosynthesis inhibitors. Adding serum to RPMI medium led to enhanced growth of A. fumigatus and extensive import of cholesterol, most of which was stored as ester. Growth enhancement and sterol import also occurred when the medium was supplemented with purified cholesterol instead of serum. Cells cultured in RPMI medium with the sterol biosynthesis inhibitors itraconazole or voriconazole showed retarded growth, a dose-dependent decrease in ergosterol levels, and accumulation of aberrant sterol intermediates. Adding serum or cholesterol to the medium partially rescued the cells from the drug-induced growth inhibition. We conclude that cholesterol import attenuates the potency of sterol biosynthesis inhibitors, perhaps in part by providing a substitute for membrane ergosterol. Our findings establish significant differences in sterol homeostasis between filamentous fungi and yeast. These differences indicate the potential value of screening aspergillosis antifungal agents in serum or other cholesterol-containing medium. Our results also suggest an explanation for the antagonism between itraconazole and amphotericin B, the potential use of Aspergillus as a model for sterol trafficking, and new insights for antifungal drug development.

The filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus is the primary pathogen for invasive aspergillosis, which causes high mortality in immunocompromised individuals such as AIDS, chemotherapy, and organ transplant patients. The polyene amphotericin B (AMB) is the preferred treatment for aspergillosis but shows serious nephrotoxicity (32). Azole sterol biosynthesis inhibitors represent another mainstay therapy for invasive aspergillosis. The triazole itraconazole (ITC) has been used extensively in the past decade, despite problems with acquired drug resistance (13, 15, 35, 37, 49) and limited bioavailability (27, 41). Voriconazole (VRC) is a newer triazole that has excellent bioavailability and shows broad-spectrum antifungal activity, even against ITC-resistant strains of Aspergillus spp. (28). However, elevated MICs have already been described (1, 48), and VRC-resistant strains have been isolated in the laboratory by prolonged exposure to selection pressure (34). A further concern with azoles is the development of cross-resistance (36). These problems are prompting studies of factors that affect drug efficacy (2) as well as research toward new antimycotic agents (29).

The primary target of AMB and the azole inhibitors is believed to be the fungal membrane sterol ergosterol (20, 32). AMB binds to ergosterol and proton ATPase pumps in the membrane (7, 32), leading to pore formation, consequent leakage of essential nutrients, and cell death. In contrast, the azoles ITC and VRC inhibit the P-450-dependent 14α-demethylase (Erg11p), a critical enzyme in sterol biosynthesis (19, 43, 52). This inhibition leads to depletion of ergosterol and accumulation of 14α-methyl sterols (19, 30, 43). The altered sterol composition disrupts the membrane structure, thereby retarding fungal growth (9, 20) and morphogenic development (6, 8).

Some pathogenic microorganisms, such as trypanosomes (12, 42), can utilize exogenous cholesterol, a structural analog and surrogate for ergosterol in membranes. Cholesterol import also occurs in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae but only under anaerobic conditions (5). Unlike yeast, filamentous fungi, such as Aspergillus niger (10, 39) and Chrysosporium keratinophilum (3), can import cholesterol under aerobic conditions. Recently, A. fumigatus was reported to thrive in the presence of high concentrations of human serum (21). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that A. fumigatus may import cholesterol and use it as a substitute for membrane ergosterol, thus protecting the fungus against sterol biosynthesis inhibitors.

To test this proposal, we cultured A. fumigatus in medium containing human serum with and without azole antifungal agents. Although pathogenic filamentous fungi usually invade tissue rather than blood, serum provided a simple and reproducible experimental system for investigating sterol uptake. We found that the serum-accelerated growth was accompanied by extensive cholesterol import. Even higher sterol uptake occurred in the presence of azole inhibitors and appeared to attenuate the effects of ITC. These findings suggest new targets for drug development and underscore the importance of screening antifungal agents in cholesterol-containing medium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antifungal agents.

Sporanox, an oral solution containing 10 mg of ITC/ml, solubilized by 400 mg of hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin/ml, was a product of Janssen Pharmaceutica N. V. (Beerse, Belgium). Vfend, a lyophilized powder containing 200 mg of VRC and 3,200 mg of sulfobutyl ether β-cyclodextrin sodium, was from Pfizer-Roerig (New York, N.Y.). Vfend was reconstituted with 19 ml of sterile water, as recommended for intravenous use, to give a clear solution, and was stored at −80°C.

Human serum.

Human serum was collected at the Transfusion Service Department, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Tex., from healthy residential donors. The serum was screened and tested negative for all blood-borne pathogens. The serum was pooled to encompass all blood types (A, B, AB, and O), including Rh-negative and -positive blood. Hemolysed, turbid, or cloudy samples were excluded. The pooled serum was filter sterilized with a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter (Corning, Inc., Corning, N.Y.) and stored at −80°C. The total cholesterol level in pooled serum was measured as 180 mg/dl by both routine clinical test (Eastman Kodak, Buffalo, N.Y.) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis after saponification.

Spore preparation.

The A. fumigatus strain 90906 was from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.). This well-studied strain is used for quality control in the M38-A standardized antifungal susceptibility test (38). The strain was inoculated on Sabouraud dextrose agar Emmons (SDAE) plates (Becton, Dickinson, and Co., Sparks, Md.) containing 0.5% pancreatic digest of casein, 0.5% peptic digest of animal tissue, 2% (wt/vol) dextrose, and 1.7% agar at 35°C. After 7 days, the spores were harvested in saline by probing the colonies with the tip of a sterile Pasteur pipette. After the suspension settled for 10 min, the supernatant, with no germinated conidia, was adjusted to 4.2 × 107 cells/ml with a hemocytometer. The conidial suspension was then aliquoted into 1-ml cryotubes and stored at −80°C. Spores were streaked on SDAE plates and cultured for 48 h at 35°C to determine the titer of CFU showing 95% viability.

Broth culture of A. fumigatus.

Liquid cultures were done in 1-liter Erlenmeyer flasks containing 250 ml of RPMI 1640 medium with l-glutamine and phenol red but without bicarbonate (Gibco BRL Laboratories, Grand Island, N.Y.) and buffered with 0.165 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) at pH 7.0. Human serum was thawed overnight at 4°C and added to cultures to give serum concentrations of 0 (control), 0.3, 3, 10, or 30%. For experiments using free cholesterol instead of serum, the cholesterol was dissolved in ethanol at 13.5 mg/ml, and 1 ml was added to each flask. Various concentrations of ITC and VRC solutions were freshly prepared in RPMI medium immediately before culture. Each flask was inoculated with a 1-ml aliquot of stock spores (thawed at room temperature). The cultures were incubated at 35°C, with shaking at 200 rpm.

Cell growth measurement.

After a fixed period of time, the mycelia were harvested by vacuum filtration through two layers of Miracloth (Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.), and the pellets were rinsed thoroughly with saline to remove traces of culture medium. Up to 60 mg (dry weight) of sediments was obtained by centrifugation at 3,000 × g from a 250-ml culture with 3% serum but without spore inoculation. These sediments, presumably being serum protein and lipids, could not be harvested by filtration because they easily pass through Miracloth. However, they partially aggregated with the fungal mycelia to exaggerate the cell mass isolated from low-yield cultures. When cell mass was >100 mg, sediment formation was not observed, this material apparently having been consumed by the fungus. In purified cholesterol experiments giving low yields of mycelia, exogenous cholesterol was rinsed from the filter pellet with CH2Cl2. (With high yields of mycelia, essentially all of the exogenous cholesterol was consumed.) The cell pellets were lyophilized for 16 h, further dried in vacuo to constant mass, and stored at −80°C before sterol analysis. The dry weight of mycelia was used as a measure of cell growth.

Dissolved oxygen levels.

Aspergillus species are obligate aerobes, and reduced oxygen levels retard their growth (24). The oxygen concentration in the broth cultures was consequently monitored with a VWR brand traceable digital oxygen meter (Control Co., Friendswood, Tex.). The probe was calibrated using air (20.8% O2) and was confirmed with air-saturated water (8.2 mg O2/liter) and N2-saturated water (0 mg O2/liter). The oxygen probe was prewarmed in a 35°C water bath before immersion in the cultures. The probe was gently swirled for about 1 min to reach stable readings.

Folch extraction.

Lyophilized cells were ground manually in a mortar. To a 150-mg portion of cell powder (or 200 μl of human serum) was added 2 mg of the antioxidant butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT; Sigma) in 400 μl of ethanol and 200 μg of the internal standard epicoprostanol (≥95% purity; Sigma) in 1 ml of ethanol. The resulting samples were extracted following the Folch procedure (17), with some modifications. Briefly, the mixture was suspended in 30 ml CH2Cl2-MeOH (2:1), sonicated for 1 h, and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 min. We used CH2Cl2 instead of CHCl3, because the latter often contains traces of HCl and phosgene, which cause degradation of ergosterol and cholesterol. The pellet was subjected to two further rounds of extraction and centrifugation. The combined supernatants from centrifugation were evaporated in vacuo. The residual organic phase was suspended in 10 ml of water and extracted with three 30-ml volumes of hexane. The combined hexane-soluble phase was dried under a nitrogen stream to a lipophilic residue containing both free and esterified sterols.

Saponification.

To a 10- to 50-mg portion of the ground dried mycelia was added 2 mg of BHT in 400 μl ethanol, 200 μg of epicoprostanol in 1 ml of ethanol, and 5 ml of 10% KOH in 80% ethanol. The mixture was purged under a nitrogen stream for 2 min and then was tightly capped and heated at 70°C for 2 h. After cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was diluted with 5 ml of water and was extracted with three 15-ml volumes of hexane. The combined hexane extracts were washed three times with 5 ml of water and 5 ml of brine and were evaporated in vacuo to a residue comprising the nonsaponifiable lipids (NSL).

NMR.

1H and 13C NMR spectra were measured as CDCl3 solutions at 25°C on a Bruker Avance 500-MHz spectrometer and were referenced to tetramethylsilane at 0 ppm (1H) or CDCl3 at 77.00 ppm (13C).

Plasma membrane isolation.

To a 12- to 14-g portion (wet weight) of thawed cells harvested from 3% serum cultures was added a suspension buffer (25 mM TrisCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 0.25 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, pH 8.5) to a total volume of 50 ml. The suspension was divided into two 50-ml Falcon tubes, each containing 10 ml of 0.5 mm-diameter glass beads. Cell disruption was done with a Fisher Genie 2 vortex mixer (Scientific Industries, Inc., Bohemia, N.Y.). Vortex mixing was performed manually for two 10-min sessions at the maximal speed, with a 5 min interval to recool the tubes on ice. After removal of the cell debris and glass beads at 700 × g, the plasma membrane was isolated by sucrose gradient centrifugation as described for yeast (54). The resulting plasma membranes were subjected to the modified Folch extraction described above, followed by NMR analysis. Parallel experiments were done on the corresponding intact cell samples (1 g [wet weight]).

Statistical analysis.

Differences between groups were evaluated by the Student's t test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Serum enhances growth of A. fumigatus.

In a time-course study, A. fumigatus was cultured in media containing 0 to 30% human serum to optimize serum concentration and determine an appropriate endpoint for harvesting cells. Under our culture conditions, no growth was detected visually during the first 14 h, with or without added serum. Beyond 20 h, the presence of 3 to 30% human serum led to two- to threefold increases in cell dry weight relative to that of serum-free controls (Fig. 1A). These data are in accord with the serum-induced growth acceleration reported by Gifford et al. (21). The cultures in 3, 10, and 30% serum reached saturation after 32 h, but the 24-h point was in the exponential growth phase at all tested serum concentrations. As standard conditions for subsequent experiments, we chose 3% serum, which is sufficient for marked growth acceleration, and a 24-h harvest time, which produces enough cellular material for sterol analysis but without nutritional limitation of growth.

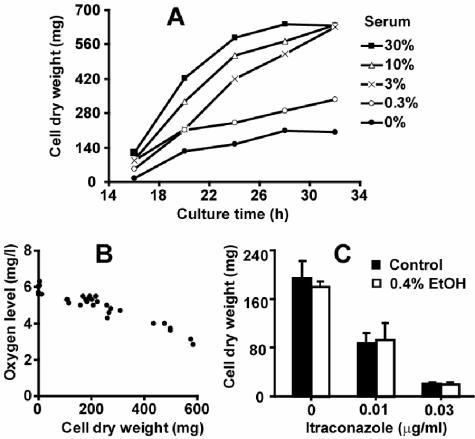

FIG. 1.

Growth of A. fumigatus cultured in 250 ml of RPMI 1640 medium under aerobic conditions. (A) Time course study showing growth enhancement by human serum. Each data point represents a single determination. (B) Inverse correlation between growth and dissolved oxygen. Data were obtained from 24-h cultures containing various amounts of serum, cholesterol, or drugs. (C) Growth in medium containing 0.4% ethanol (EtOH) with or without ITC. Data represent the means ± standard deviations of three independent determinations. No significant difference (P > 0.05) was found between 0 and 0.4% ethanol-treated cells at the same concentration of ITC.

Dissolved oxygen in the medium decreased gradually during cell growth. At harvest, this varied from 6.3 to 3.2 mg/liter and was inversely proportional to cell mass (Fig. 1B). The rapidly growing cells evidently consumed more dissolved oxygen from the medium than could be supplied by aeration from shaking. The inverse correlation between growth and dissolved oxygen was unaffected by addition of serum or drugs to the medium.

Effect of serum on ergosterol levels and cholesterol import.

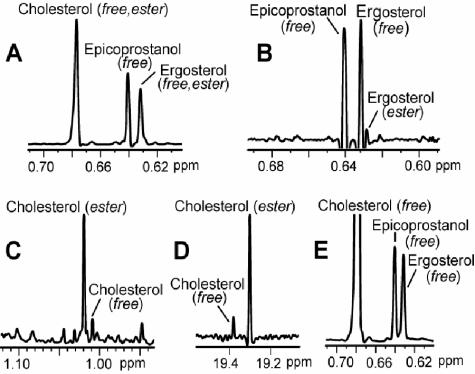

As shown in Fig. 2, sterols in the NSL fraction were quantitated from the 500-MHz 1H NMR spectrum based on resolution of the H-18 signals of cholesterol (δ 0.678), ergosterol (δ 0.631), and the internal standard epicoprostanol (δ 0.641). The ratio of ester to free sterol in the Folch extracts was determined by comparing ester and free sterol signal intensities of ergosterol (δH 0.629 versus 0.632) and cholesterol (δH 1.019 versus 1.009 and δC 19.29 versus 19.38). Errors from interference by extraneous signals were excluded by confirming the ratios using a variety of 1H and 13C NMR signal pairs, including olefinic signals and the H-18 ester/free sterol signals for cholesterol (δH 0.677 versus 0.678), the latter pair requiring substantial Gaussian apodization for resolution.

FIG. 2.

Partial NMR spectra showing peaks used for quantitation. (A) Folch extract of cells cultured in 0.3% serum, showing the H-18 signals for cholesterol, ergosterol, and the internal standard epicoprostanol. (B) Folch extract of a control sample. Strong resolution enhancement was used to separate the peaks of free and esterified ergosterol. (C) The H-19 peaks of free and esterified cholesterol of a Folch extract of cells cultured in 3% serum. (D) The C-19 peaks of free and esterified cholesterol in the 13C NMR spectrum (125 MHz) of the same sample as that shown in panel C. (E) The H-18 signals of NSL of cells cultured in 54 μg of cholesterol/ml.

Table 1 shows the ergosterol and cholesterol levels of cells cultured for 24 h in different concentrations of human serum. Fungal growth increased with increasing serum concentration, whereas cholesterol import from 3 to 30% serum was fairly constant at about 20 μg/mg. The cultures grown in 3% serum consumed 67% of the cholesterol available in the medium, but only 10 to 30% of available cholesterol was used at higher serum concentrations. About 80% of the imported cholesterol was stored in ester form. Cholesterol import had no obvious effect on ergosterol levels, contrary to our expectation that growth in serum would be accelerated by use of imported cholesterol instead of ergosterol for new membranes. Ergosteryl ester was detected only in cells cultured in 0 and 0.3% serum, suggesting that any stored ergosterol was released for use in membrane to sustain the rapid growth observed with 3 to 30% serum. It should be noted that the modified Folch extraction seemed less efficient than saponification in extracting ergosterol, especially from control and 0.3%-serum-cultured cells. (Those cells were more difficult to pulverize with a mortar and pestle than cells from cultures containing 3 to 30% serum.) However, cholesterol extraction appeared to be complete.

TABLE 1.

Cholesterol import in A. fumigatus cultured with different concentrations of human seruma

| Measurement | Import levels at serum concn (%):

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.3 | 3 | 10 | 30 | |

| Cell mass (mg/250 ml) | 237 ± 27 | 286 ± 33 | 454 ± 41 | 545 ± 45 | 587 ± 9 |

| Total cholesterol in medium (mg) | 0 | 1.35 | 13.5 | 45 | 135 |

| Cholesterol import (mg/250 ml) | 0 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 9.0 ± 0.6 | 12.5 ± 2.7 | 13.9 ± 3.2 |

| Cholesterol (μg/mg of cell) | 0 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 19.9 ± 2.5 | 22.7 ± 3.2 | 23.8 ± 5.5 |

| Cellular ester/free cholesterol | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 0.6 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | |

| Free cholesterol (μg/mg of cell) | 0 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 3.6 ± 0.8 | 3.6 ± 0.7 |

| Cholesteryl ester (μg/mg of cell) | 0 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 16.5 ± 2.0 | 19.1 ± 2.4 | 20.0 ± 4.8 |

| Ergosterol (μg/mg of cell) | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.3 |

| Cellular free/ester ergosterol | 16.4 ± 6.7 | 26.6 ± 8.7 | ND | ND | ND |

| Free ergosterol (μg/mg of cell) | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.3 |

| Ergosterol ester (μg/mg of cell) | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Total free sterol (μg/mg of cell) | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 5.7 ± 0.4 | 6.0 ± 0.8 | 6.6 ± 0.8 |

| Cellular free cholesterol/free ergosterol | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| Total cellular cholesterol/ergosterol | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 8.7 ± 1.7 | 9.6 ± 1.5 | 8.1 ± 2.4 |

Results are from 250-ml cultures in 1-liter flasks. Sterols were quantitated by 1H NMR analysis of the Folch extract of lyophilized mycelia. Data represent the means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments. ND, not determined. The ratio of ester/free cholesterol in human serum was 3.3 ± 0.0 as measured with the same modified Folch extraction.

Effects of serum or purified cholesterol on ITC-treated A. fumigatus.

We next studied how cholesterol import affects the activities of antifungal agents. This work was generally done with subinhibitory drug concentrations, because our experimental methodology required fungal growth. As shown in Table 2, 0.01 and 0.03 μg of ITC/ml reduced the cell growth by 58 to 82% and ergosterol levels by 34 to 79%. At an ITC concentration of 0.12 μg/ml, cell growth was completely eliminated. However, addition of 3% serum to the medium resulted in a dramatic rescue effect, allowing considerable growth even at the highest ITC dose. At the intermediate ITC dose, growth even exceeded that in controls lacking both serum and ITC, and ergosterol levels were only moderately depressed. Cholesterol uptake increased markedly with increasing ITC concentration, a result suggesting that cells upregulate cholesterol import when ergosterol biosynthesis is compromised.

TABLE 2.

Effects of serum or purified cholesterol on ITC-treated A. fumigatusa

| Treatment | ITC (μg/ml) | Cell mass (mg) | Ergosterol (μg/mg) | Cholesterol (μg/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.00 | 185 ± 20 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | |

| 0.01 | 78 ± 8b* | 1.9 ± 0.1b* | ||

| 0.03 | 33 ± 2b* | 0.6 ± 0.0b* | ||

| 0.12 | 0 ± 0b* | |||

| Serum (3%) | 0.00 | 460 ± 34b* | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 24.2 ± 1.9 |

| 0.03 | 260 ± 4c* | 2.2 ± 0.1c** | 35.8 ± 0.7 | |

| 0.12 | 99 ± 3c* | 1.2 ± 0.1c* | 68.5 ± 3.2 | |

| Cholesterol (54 μg/ml) | 0.00 | 211 ± 11 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 61.1 ± 2.1 |

| 0.01 | 202 ± 15c* | 2.7 ± 0.0c* | 60.5 ± 2.8 | |

| 0.03 | 111 ± 4c* | 2.3 ± 0.0c* | 105.5 ± 3.5 | |

| 0.12 | 6 ± 1c* | ND | ND |

Cell mass represents dried cells from 250-ml cultures. Sterol levels were determined from 1H NMR analysis of the NSL of lyophilized cells. ND, not determined. These data represent the means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.05.

Comparison with control (0% serum and 0% ITC; n = 6).

Comparison with same dose of drug-treated cells with no serum or cholesterol.

In order to exclude the growth-promoting effects of nonsterol serum components, we also cultured A. fumigatus with purified cholesterol. In these experiments, cholesterol was added from an ethanolic solution to a final concentration of 54.0 μg/ml, equivalent to that in 3% serum. A control experiment showed that the final concentration of 0.4% ethanol did not affect cell growth with or without ITC (Fig. 1C). We did not attempt to solubilize the cholesterol with cyclodextrins or detergents like Tween-80, because the former can sequester cholesterol and the latter is known to affect sterol metabolism in A. niger (39). Lipoprotein cholesterol and liposome preparations that would introduce an additional carbon source for growth were also avoided. Our results showed that cholesterol alone had a substantial rescue effect, giving marked increases in growth and ergosterol levels compared to those of control cultures with 0.01 and 0.03 μg of ITC/ml. At 0.01 μg of ITC/ml, cholesterol essentially negated all effects of ITC on fungal growth and ergosterol levels. The protective effect of cholesterol was diminished at 0.03 μg of ITC/ml, with cell growth being halved and cholesterol import increasing by 73% relative to that of drug-free cultures. Although these protective properties of cholesterol were substantial, serum consistently gave a much stronger rescue effect.

Effects of serum or purified cholesterol on VRC-treated A. fumigatus.

Experiments analogous to those described for ITC were performed on VRC, a newer antifungal agent. As shown in Table 3, doses of 0.12 to 0.30 μg of VRC/ml reduced cell growth by 18 to 96% and ergosterol levels by 29 to 61%. In contrast to the ITC experiments, serum had little or no protective effect. At the lowest dose (0.12 μg/ml) of VRC, serum enhanced growth, although the cell mass was less than that in drug-free serum cultures. No protective effect was found at higher VRC concentrations, despite a twofold increase in cholesterol import at the intermediate VRC dosage. Surprisingly, ergosterol levels were lower than those in the serum-free VRC cultures.

TABLE 3.

Effects of serum or purified cholesterol on VRC-treated A. fumigatusa

| Treatment | VRC (μg/ml) | Cell mass (mg) | Ergosterol (μg/mg) | Cholesterol (μg/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.00 | 174 ± 8 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | |

| 0.12 | 143 ± 2b* | 2.2 ± 0.0b* | ||

| 0.20 | 75 ± 7b* | 1.9 ± 0.1b* | ||

| 0.30 | 8 ± 2b* | 1.2 ± 0.1b* | ||

| 0.50 | 0 ± 0b* | ND | ||

| Serum (3%) | 0.12 | 348 ± 14c* | 1.6 ± 0.1c* | 26.7 ± 1.5 |

| 0.20 | 80 ± 12d | 0.5 ± 0.0c* | 64.8 ± 5.2 | |

| 0.30 | 0 ± 0 | ND | ||

| Cholesterol (54 μg/ml) | 0.12 | 166 ± 10c** | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 69.6 ± 11.7 |

| 0.20 | 94 ± 4c** | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 101.3 ± 14.6 | |

| 0.30 | 21 ± 2c* | 1.3 ± 0.0 | 374.2 ± 36.8 |

Substitution of purified cholesterol for serum in the medium provided some protection at all VRC concentrations. Some growth enhancement was observed at the highest dosage, enabling measurements of cholesterol import. VRC treatment caused dramatic dose-dependent increases in cholesterol import, with the level of cholesterol at the highest dosage being six times that in drug-free culture. However, ergosterol levels were unchanged relative to those of serum-free or cholesterol-free cultures. In sharp contrast to experiments with ITC, the drug-induced reduction in ergosterol levels was not even partially restored by serum or purified cholesterol in VRC-treated cultures, although cholesterol import was comparable to that in ITC experiments. These combined results indicate that serum and purified cholesterol provide much less protection against VRC than ITC.

Aberrant sterol profile in ITC- and VRC-treated Aspergillus spp.

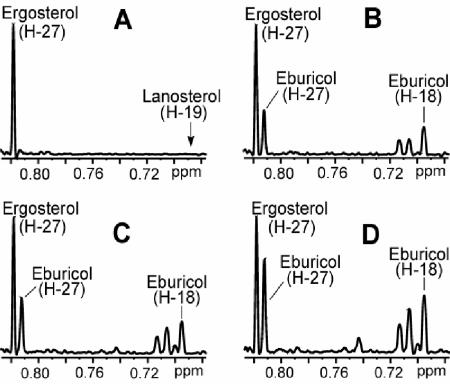

Several aberrant sterols were observed in 1H NMR spectra of NSL from drug-treated cells. As shown in Fig. 3, a major product is eburicol, present at 30% of the ergosterol level in cells treated with moderate concentrations of ITC or VRC. In contrast to reports of lanosterol as a prominent sterol in S. cerevisiae ERG11 mutants (19) and VRC-treated Candida spp. (43), our samples showed negligible amounts of lanosterol (<1% relative to ergosterol). Also, 4α-methyl sterols were present at 40% of 4,4-dimethyl sterol levels, a higher ratio than that reported for yeast by gas chromatographic analysis (19, 43). Aberrant sterols from ITC- and VRC-treated cells had a similar profile, which was not affected by serum or cholesterol in the medium.

FIG. 3.

1H NMR spectra showing profiles of the major aberrant sterol intermediates that accumulate upon treatment with ITC and VRC. Samples are from the NSL of the cell pellets. (A) Control culture with no drug treatment. Lanosterol was also below the 1% detection limit in drug-treated cultures. (B) Cells treated with 0.01 μg of ITC/ml. Cells treated with 0.12 μg of VRC/ml (C) or with 0.20 μg/ml VRC (D). Signals at δ 0.701, 0.706, and 0.743 represent unidentified sterols, such as 14α-methylfecosterol.

Incorporation of cholesterol into plasma membrane.

In a separate experiment, A. fumigatus was cultured in 3% serum with ITC, VRC, or no drug. (The former two cultures showed about 10% growth inhibition.) After collection of the mycelia by filtration and cell disruption, plasma membrane was isolated from each sample by sucrose gradient centrifugation. NMR analysis of the Folch extracts showed that the total cholesterol/ergosterol ratio in the plasma membrane fraction was about 10% of that in intact cells, whereas the ratio of free/esterified cholesterol increased two- to fourfold (Table 4). The ester contaminant in the membrane fraction probably arose from breakage of lipid particles during processing.

TABLE 4.

Analysis of plasma membrane sterolsa

| Sample no. | Cholesterol/ergosterol

|

Free/ester cholesterol

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact cells | Plasma membrane | Intact cells | Plasma membrane | |

| 1 | 5.47 | 0.50 | 0.12 | 0.45 |

| 2 | 5.07 | 0.38 | 0.08 | 0.17 |

| 3 | 5.07 | 0.42 | 0.13 | 0.33 |

Data were from a single analysis of non-drug-treated control culture (sample 1) or ITC- and VRC-treated cells (samples 2 and 3). All the cells were cultured in 3% serum.

These preliminary data indicate that cholesterol is partially incorporated into the plasma membrane of cells cultured in 3% serum but that the major membrane sterol remains ergosterol. Repeated attempts to isolate plasma membrane from cultures with higher levels of growth inhibition failed, as judged by free/esterified cholesterol ratios, perhaps because of the heavy loading of cholesterol in the presence of drugs or because of the drug-induced distortions of membrane properties, as was reported for Candida spp. (6).

DISCUSSION

Antifungal therapy with sterol biosynthesis inhibitors is often thwarted by the ability of the pathogen to counteract the drug-induced changes in sterol homeostasis. This can occur through mutations of 14α-demethylase (16), lesions in the Δ5(6)-desaturase (19), upregulation of ergosterol biosynthesis genes (25, 26), or overexpression of drug efflux pumps (14, 37, 46). Another possible factor is exogenous sterol uptake. Although uptake of abiotic cholesterol by filamentous fungi is known (3, 39), effects of sterol import on antifungal therapy have never been studied. Our results demonstrate that the fungal pathogen A. fumigatus imports cholesterol from medium, a process that is associated with enhanced growth. Cholesterol import increases markedly in the presence of azole antifungals and appears to attenuate the effects of these drugs.

Unlike many other pathogenic microorganisms, A. fumigatus thrives in high concentrations of serum. This enhanced growth has been ascribed to the unusual ability of A. fumigatus to acquire iron from serum (21), presumably by excretion and uptake of siderophores (23). Our results from culturing A. fumigatus with purified cholesterol in RPMI medium indicate that the cholesterol in serum also enhances growth. Interestingly, this mild stimulatory effect of purified cholesterol was accompanied by an almost threefold increase of cholesterol import relative to that of cultures in serum-containing medium. When azole drugs were present, cholesterol import had a greater effect on fungal growth. Both serum and purified cholesterol showed a marked rescue effect on ITC-treated A. fumigatus. Ergosterol levels were significantly restored, and cholesterol was imported in higher amounts than in cultures without drug. Serum also accelerated cell growth somewhat at a low dose of VRC. These observations indicate that cholesterol import may have adverse effects on antifungal therapy. Therefore, it may be beneficial to screen sterol biosynthesis inhibitors intended for use against aspergillosis in the presence of serum or other cholesterol-containing media.

In contrast to the pronounced rescue effect on ITC, serum did not protect A. fumigatus at higher concentrations of VRC, and ergosterol levels were not improved by serum or cholesterol. We considered several factors that might account for these differing rescue effects. Toxicity of aberrant sterol intermediates was deemed an unlikely factor, because noncholesterol sterol profiles were generally similar in the ITC- and VRC-treated cultures, with or without serum or cholesterol. Azoles inhibit the 14α-demethylase by competing with heme for iron in the active site (51, 52), and differing iron-chelating capacities of the azoles may have contributed to the uneven rescue effects. A related factor could be differential sequestration of exogenous iron, which can be growth limiting. Protein binding of azoles influences antifungal potency in Candida albicans (45, 53), and the higher binding of ITC relative to that of VRC (4, 44) could partially explain the disproportionate rescue effects. Differences due to cholesterol import represent still another factor of potential importance. These effects may be related to the improved clinical efficacy of VRC over ITC in aspergillosis therapy.

The mechanism linking cholesterol import with fungal growth and protection against azole toxicity is not obvious. We initially hypothesized that imported cholesterol could facilitate growth by relieving the proliferating cells of the need to synthesize ergosterol for new membrane formation. However, unlike the downregulation of ergosterol biosynthesis in Trypanosoma brucei by cholesterol import (12), ergosterol levels were normal in A. fumigatus grown with serum or purified cholesterol. Moreover, most of the imported cholesterol was in ester form, presumably being stored in lipid particles, as occurs in yeast (55). Although cholesterol has been implicated as a carbon source in filamentous fungi (3), our spectral analyses did not indicate any cholesterol oxidation products or other sterol metabolites. Also, the RPMI medium already contained abundant carbon for growth. Sucrose gradient centrifugation confirmed that some of the imported cholesterol was present in plasma membrane. This result supports the hypothesis that cholesterol is incorporated into membranes to compensate for ergosterol depletion and that this process underlies the protective mechanism of cholesterol import against azole antifungals.

Cholesterol import could also counteract azole toxicity by fulfilling nonmembrane functions of ergosterol. For example, in yeast, ergosterol is implicated in amino acid and pyrimidine transport, respiratory activity (40), and cell cycle progression (33). The in vitro sequestration of drugs by cholesterol in the medium might have further contributed to the rescue effects, especially for the hydrophobic ITC. However, our observation that nearly all the exogenous cholesterol was imported in most ITC-treated cultures indicates that extracellular cholesterol binding was not responsible for the rescue effects.

Exogenous cholesterol is known to protect fungi against polyene antibiotics like AMB by sequestration of the drugs (20, 22). Cholesterol import may also influence the efficacy of AMB. Prior exposure of A. fumigatus to azoles makes subsequent AMB therapy less effective (31). Our findings indicate that this exposure stimulates cholesterol import and leads to substantial incorporation of cholesterol into plasma membrane. The reduced affinity of AMB for cholesterol- versus ergosterol-containing membranes (18) thus can explain why AMB administration needs to precede azole therapy for aspergillosis. Sterol-AMB interactions may have different mechanistic origins in Candida (20).

The mechanisms of sterol uptake by Aspergillus differ from that used by some other microorganisms. Trypanosoma brucei imports sterol by endocytosis via low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors (11). This mechanism presumably does not operate in Aspergillus, because a BLAST search of the A. fumigatus genome (http://www.tigr.org) predicted no orthologs of known LDL receptors. In contrast, A. fumigatus does encode close homologs of the S. cerevisiae ATP-binding cassette transporters AUS1 and PDR11, which were recently reported to be required for sterol uptake in yeast (50). A key difference between these fungi is that S. cerevisiae imports sterols only under anaerobic conditions, whereas A. fumigatus sterol import is independent of dissolved oxygen concentration. These fungi may use similar transport proteins but regulate their expression differently. Cholesterol uptake by Aspergillus appears to be a well-regulated process. For example, the extent of cholesterol import was almost independent of serum concentration (3 to 30% range) but was highly dependent on the concentration of azole antifungal agents. The ease and extent of sterol import in filamentous fungi compared to that of yeast suggests that Aspergillus could be a useful model for studying cellular sterol trafficking (47).

In summary, we have demonstrated that A. fumigatus readily imports exogenous cholesterol under aerobic conditions. Our results, although mostly from subinhibitory drug concentrations, indicate that cholesterol import is associated with enhanced fungal growth and reduced potency of sterol biosynthesis inhibitors. Assessing the clinical ramifications of this effect will require classical susceptibility testing and animal studies. We are presently developing a small-scale MIC test using the NCCLS M38-A format, and the preliminary data are consistent with results described here. Our findings, together with the recognition that pathogenic microorganisms differ markedly in their ability to import cholesterol (3, 39), have immediate biomedical implications and should foster the development of improved antifungal agents.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Robert A. Welch Foundation (C-1323) and NIH (AI41598) for funding.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham, O. C., E. K. Manavathu, J. L. Cutright, and P. H. Chandrasekar. 1999. In vitro susceptibilities of Aspergillus species to voriconazole, itraconazole, and amphotericin B. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 33:7-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler-Moore, J., and R. T. Proffitt. 2002. AmBisome: liposomal formulation, structure, mechanism of action and pre-clinical experience. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49(Suppl. 1):21-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.al Musallam, A. A., and S. S. Radwan. 1990. Wool-colonizing micro-organisms capable of utilizing wool-lipids and fatty acids as sole sources of carbon and energy. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 69:806-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andes, D., K. Marchillo, T. Stamstad, and R. Conklin. 2003. In vivo pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a new triazole, voriconazole, in a murine candidiasis model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3165-3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andreasen, A. A., and T. J. Stier. 1953. Anaerobic nutrition of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. I. Ergosterol requirement for growth in a defined medium. J. Cell Physiol. 41:23-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belanger, P., C. C. Nast, R. Fratti, H. Sanati, and M. Ghannoum. 1997. Voriconazole (UK-109,496) inhibits the growth and alters the morphology of fluconazole-susceptible and -resistant Candida species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1840-1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolard, J. 1986. How do the polyene macrolide antibiotics affect the cellular membrane properties? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 864:257-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borgers, M., and M. A. Van de Ven. 1989. Mode of action of itraconazole: morphological aspects. Mycoses 32(Suppl. 1):53-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bottema, C. D., R. J. Rodriguez, and L. W. Parks. 1985. Influence of sterol structure on yeast plasma membrane properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 813:313-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chowdhury, B., S. K. Das, and S. K. Bose. 1998. Use of resistant mutants to characterize the target of mycobacillin in Aspergillus niger membranes. Microbiology 144(Pt. 4):1123-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coppens, I., and P. J. Courtoy. 2000. The adaptative mechanisms of Trypanosoma brucei for sterol homeostasis in its different life-cycle environments. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:129-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coppens, I., and P. J. Courtoy. 1995. Exogenous and endogenous sources of sterols in the culture-adapted procyclic trypomastigotes of Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 73:179-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dannaoui, E., E. Borel, M. F. Monier, M. A. Piens, S. Picot, and F. Persat. 2001. Acquired itraconazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:333-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Sorbo, G., H. Schoonbeek, and M. A. De Waard. 2000. Fungal transporters involved in efflux of natural toxic compounds and fungicides. Fungal Genet. Biol. 30:1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denning, D. W., K. Venkateswarlu, K. L. Oakley, M. J. Anderson, N. J. Manning, D. A. Stevens, D. W. Warnock, and S. L. Kelly. 1997. Itraconazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1364-1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diaz-Guerra, T. M., E. Mellado, M. Cuenca-Estrella, and J. L. Rodriguez-Tudela. 2003. A point mutation in the 14α-sterol demethylase gene cyp51A contributes to itraconazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1120-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folch, J., M. Lees, and G. H. Sloane Stanley. 1957. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226:497-509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garrigues, J.-C., I. Rico-Lattes, E. Perez, and A. Lattes. 1998. Comparative study for the incorporation of a new antifungal family of neoglycolipids and amphotericin B in monolayers containing phospholipids and cholesterol or ergosterol. Langmuir 14:5968-5971. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geber, A., C. A. Hitchcock, J. E. Swartz, F. S. Pullen, K. E. Marsden, K. J. Kwon-Chung, and J. E. Bennett. 1995. Deletion of the Candida glabrata ERG3 and ERG11 genes: effect on cell viability, cell growth, sterol composition, and antifungal susceptibility. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2708-2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghannoum, M. A., and L. B. Rice. 1999. Antifungal agents: mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:501-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gifford, A. H., J. R. Klippenstein, and M. M. Moore. 2002. Serum stimulates growth of and proteinase secretion by Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect. Immun. 70:19-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gottlieb, D., H. E. Carter, J. H. Sloneker, and A. Ammann. 1958. Protection of fungi against polyene antibiotics by sterols. Science 128:361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haas, H. 2003. Molecular genetics of fungal siderophore biosynthesis and uptake: the role of siderophores in iron uptake and storage. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 62:316-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall, L. A., and D. W. Denning. 1994. Oxygen requirements of Aspergillus species. J. Med. Microbiol. 41:311-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henry, K. W., J. T. Nickels, and T. D. Edlind. 2002. ROX1 and ERG regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: implications for antifungal susceptibility. Eukaryot. Cell 1:1041-1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henry, K. W., J. T. Nickels, and T. D. Edlind. 2000. Upregulation of ERG genes in Candida species by azoles and other sterol biosynthesis inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2693-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffman, H. L., E. J. Ernst, and M. E. Klepser. 2000. Novel triazole antifungal agents. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 9:593-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson, L. B., and C. A. Kauffman. 2003. Voriconazole: a new triazole antifungal agent. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:630-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson, M. D., and J. R. Perfect. 2003. Caspofungin: first approved agent in a new class of antifungals. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 4:807-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelly, S. L., D. C. Lamb, A. J. Corran, B. C. Baldwin, and D. E. Kelly. 1995. Mode of action and resistance to azole antifungals associated with the formation of 14α-methylergosta-8,24(28)-dien-3β,6α-diol. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 207:910-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kontoyiannis, D. P., R. E. Lewis, N. Sagar, G. May, R. A. Prince, and K. V. Rolston. 2000. Itraconazole-amphotericin B antagonism in Aspergillus fumigatus: an E-test-based strategy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2915-2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Latge, J. P. 1999. Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:310-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lees, N. D., M. Bard, and D. R. Kirsch. 1999. Biochemistry and molecular biology of sterol synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 34:33-47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manavathu, E. K., O. C. Abraham, and P. H. Chandrasekar. 2001. Isolation and in vitro susceptibility to amphotericin B, itraconazole, and posaconazole of voriconazole-resistant laboratory isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 7:130-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore, C. B., N. Sayers, J. Mosquera, J. Slaven, and D. W. Denning. 2000. Antifungal drug resistance in Aspergillus. J. Infect. 41:203-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosquera, J., and D. W. Denning. 2002. Azole cross-resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:556-557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nascimento, A. M., G. H. Goldman, S. Park, S. A. Marras, G. Delmas, U. Oza, K. Lolans, M. N. Dudley, P. A. Mann, and D. S. Perlin. 2003. Multiple resistance mechanisms among Aspergillus fumigatus mutants with high-level resistance to itraconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1719-1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2002. Antifungal susceptibility testing for filamentous mold. M38a. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 39.Nemec, T., and K. Jernejc. 2002. Influence of Tween 80 on lipid metabolism of an Aspergillus niger strain. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 101:229-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parks, L. W., S. J. Smith, and J. H. Crowley. 1995. Biochemical and physiological effects of sterol alterations in yeast-a review. Lipids 30:227-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patterson, T. F., J. Peters, S. M. Levine, A. Anzueto, C. L. Bryan, E. Y. Sako, O. L. Miller, J. H. Calhoon, and M. G. Rinaldi. 1996. Systemic availability of itraconazole in lung transplantation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2217-2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodrigues, C. O., R. Catisti, S. A. Uyemura, A. E. Vercesi, R. Lira, C. Rodriguez, J. A. Urbina, and R. Docampo. 2001. The sterol composition of Trypanosoma cruzi changes after growth in different culture media and results in different sensitivity to digitonin-permeabilization. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 48:588-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanati, H., P. Belanger, R. Fratti, and M. Ghannoum. 1997. A new triazole, voriconazole (UK-109,496), blocks sterol biosynthesis in Candida albicans and Candida krusei. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2492-2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schafer-Korting, M., H. C. Korting, F. Amann, R. Peuser, and A. Lukacs. 1991. Influence of albumin on itraconazole and ketoconazole antifungal activity: results of a dynamic in vitro study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:2053-2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schafer-Korting, M., H. C. Korting, W. Rittler, and W. Obermuller. 1995. Influence of serum protein binding on the in vitro activity of anti-fungal agents. Infection 23:292-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slaven, J. W., M. J. Anderson, D. Sanglard, G. K. Dixon, J. Bille, I. S. Roberts, and D. W. Denning. 2002. Increased expression of a novel Aspergillus fumigatus ABC transporter gene, atrF, in the presence of itraconazole in an itraconazole resistant clinical isolate. Fungal Genet. Biol. 36:199-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sturley, S. L. 2000. Conservation of eukaryotic sterol homeostasis: new insights from studies in budding yeast. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1529:155-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verweij, P. E., M. Mensink, A. J. Rijs, J. P. Donnelly, J. F. Meis, and D. W. Denning. 1998. In-vitro activities of amphotericin B, itraconazole and voriconazole against 150 clinical and environmental Aspergillus fumigatus isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 42:389-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Warris, A., C. M. Weemaes, and P. E. Verweij. 2002. Multidrug resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:2173-2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilcox, L. J., D. A. Balderes, B. Wharton, A. H. Tinkelenberg, G. Rao, and S. L. Sturley. 2002. Transcriptional profiling identifies two members of the ATP-binding cassette transporter superfamily required for sterol uptake in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 277:32466-32472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xiao, L., V. Madison, A. S. Chau, D. Loebenberg, R. E. Palermo, and P. M. McNicholas. 2004. Three-dimensional models of wild-type and mutated forms of cytochrome P450 14α-sterol demethylases from Aspergillus fumigatus and Candida albicans provide insights into posaconazole binding. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:568-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoshida, Y., and Y. Aoyama. 1987. Interaction of azole antifungal agents with cytochrome P-45014DM purified from Saccharomyces cerevisiae microsomes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 36:229-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhanel, G. G., D. G. Saunders, D. J. Hoban, and J. A. Karlowsky. 2001. Influence of human serum on antifungal pharmacodynamics with Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2018-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zinser, E., and G. Daum. 1995. Isolation and biochemical characterization of organelles from the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 11:493-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zweytick, D., K. Athenstaedt, and G. Daum. 2000. Intracellular lipid particles of eukaryotic cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1469:101-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]