Abstract

Background

Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM) rates have been increasing in the U.S. Though some studies have reported high overall satisfaction among women who undergo CPM, it is unclear how long-term satisfaction differs from that of women who undergo unilateral mastectomy (UM). Furthermore, few studies have assessed whether the effects of CPM on body image differ from those of breast conserving surgery (BCS) or UM.

Methods

We analyzed responses from a survey of women with both a personal and family history of breast cancer who were enrolled in the Sister Study (n=1176). Among women who underwent mastectomy, satisfaction with mastectomy decision and reconstruction was compared between women who underwent CPM and UM. We also evaluated responses on 5 items related to body image according to surgery type (BCS, UM without reconstruction, CPM without reconstruction, UM with reconstruction, and CPM with reconstruction).

Results

Participants were, on average, 60.8 years old at diagnosis (SD=8.7) and 3.6 years post-diagnosis at the time of survey (SD=1.7). BCS was the most common surgical treatment reported (63%), followed by CPM (22%) and UM (15%). Satisfaction with mastectomy decision was reported by 97% of women who underwent CPM and 89% of those who underwent UM. Compared to other surgery types, women who underwent CPM without reconstruction reported feeling more self-conscious, less feminine, less whole, and less satisfied with the appearance of their breasts. Body image was consistently highest among women who underwent BCS.

Conclusions

In our sample of women with both a personal and family history of breast cancer, most were highly satisfied with their mastectomy decision, including those who elected to undergo CPM. However, body image was lowest among women who underwent CPM without reconstruction. Our findings may inform decisions among women considering various courses of surgical treatment.

Keywords: contralateral prophylactic mastectomy, breast cancer, body image

Background

Recommendations for the surgical treatment of breast cancer have evolved over the past 30 years [1]. While mastectomy was once the standard of care for patients diagnosed with early stage breast cancer, randomized trials have demonstrated equivalent survival for patients treated with breast conserving surgery (BCS) followed by radiation [2, 3]. Despite these findings, recent studies have indicated increasing rates of mastectomy, particularly contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM) [4–7], a trend which may be largely driven by patient choice [8]. Though there is evidence that women with unilateral breast cancer have an increased risk of developing a second cancer in the contralateral breast, the annual risk remains low at about 0.5% [9], and the survival benefit of CPM is unclear [10]. Thus women’s surgical choices may be informed not only by perceptions of individual risk, but also by consideration of potential cosmetic outcomes and patient satisfaction following surgery.

Women who elect to undergo CPM frequently report high satisfaction with the procedure, with overall satisfaction above 80% in most studies [11–13]. Recent reports also suggest that quality of life and well-being are not negatively affected by CPM [13, 14]. On the other hand, adverse effects on body image, such as feeling less feminine or less physically attractive, may be relatively common [12, 14]. However, it is unclear whether body image and satisfaction with appearance following CPM differ from that following BCS or unilateral mastectomy. Furthermore, few studies have evaluated whether reconstruction impacts satisfaction and body image among women who have had either CPM or unilateral mastectomy (UM).

The objective of the current study was to evaluate long-term satisfaction with surgical outcomes in breast cancer patients with a family history of breast cancer. We also examined body image according to surgery type and reconstruction.

Methods

In 2012, the Sister Study Survivorship Survey was conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) to examine experiences with diagnosis and treatment and survivorship concerns among women with a prior breast cancer diagnosis. Survey respondents included in the current study were women diagnosed with breast cancer who were enrolled in the Sister Study, a cohort of initially breast cancer-free women whose sister had been diagnosed with breast cancer. The design and inclusion criteria of the Sister Study have been described elsewhere [15]. This survey was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the NIEHS/NIH as an amendment to the protocol for the Sister Study.

Study population

Sister Study participants were eligible for the Survivorship Survey if they were diagnosed with their first breast cancer by October 9, 2012, had completed recent study follow-up activities, and spoke English, in addition to meeting all other Sister Study inclusion criteria. Among 1565 eligible women in the Sister Study, a total of 1415 completed the survey, for a response rate of 90.4%. For the current study, we excluded women who were later determined to have no breast cancer diagnosis (n=3) and those whose first breast cancer diagnosis was prior to Sister Study enrollment (n=42). We also restricted to women with unilateral breast cancer, excluding those with bilateral breast cancer or missing laterality (n=56). Women with no record of breast surgery or missing information on surgery were excluded (n=37). Seventeen women were excluded because they received an in situ diagnosis other than ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), and three women were excluded who were diagnosed with stage 4 invasive breast cancer. Women who reported that their BRCA1 or BRCA2 test results indicated increased risk of cancer were also excluded from this analysis (n = 74). Seven women with a mastectomy were excluded for missing reconstruction information. In total, 1176 contributed information as patients with incident breast cancer who had undergone breast surgery.

Data collection

Sociodemographic characteristics were taken from questionnaires completed upon enrollment in the Sister Study. Medical records were abstracted to ascertain surgery type (unilateral mastectomy, bilateral mastectomy, or BCS) for 95% of participants. If missing from medical records, this information was taken from self-reported measures on the Survivorship Survey or the Breast Cancer Follow-Up Questionnaire, a questionnaire completed by Sister Study participants approximately six months after diagnosis of incident breast cancer. These self-reported measures were also used to obtain information regarding receipt of reconstruction and other forms of treatment (chemotherapy, radiation therapy and endocrine therapy).

For women who underwent a mastectomy, the Survivorship Survey queried satisfaction with the decision to have a mastectomy and whether they would choose to have a mastectomy again given what they had experienced. These items were each rated on a five-point ordinal scale. Responses for satisfaction with the decision to have mastectomy ranged from “Very satisfied” to “Very dissatisfied,” while responses for the choice to have that mastectomy again ranged from “Definitely yes” to “Definitely not.” Women who had a mastectomy were also asked to report any complications that occurred during or after surgery. Further, women who underwent reconstruction were queried regarding their satisfaction with their reconstruction and the type of reconstruction that they received (alloplastic/implant or autologous).

All participants, regardless of surgery type, responded to five items related to body image following breast cancer treatment. These items were adapted from a body image scale developed for use with cancer patients [16] and pertained to feeling self-conscious about appearance, feeling less feminine as a result of breast cancer, satisfaction with appearance of breasts, body seeming less whole since breast cancer treatment, and feeling less sexually attractive as a result of breast cancer. All such items were rated on a five point ordinal scale, ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree.”

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine participant characteristics by surgery type. Among women who underwent either UM or CPM, outcomes pertaining to mastectomy and reconstruction satisfaction and the occurrence of complications were summarized using frequencies and percentages.

Items pertaining to body image, including feeling self-conscious, less feminine, less whole, and less sexually attractive were scored from 1 (“Strongly agree”) to 5 (“Strongly disagree”). The item pertaining to satisfaction with breast appearance was scored from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly agree”). Thus higher scores on all items reflected better body image. Scores on the five individual items were also summed to create a total body image score. Generalized linear models were used to calculate average scores for individual items and for the total score according to surgery type and reconstruction. All models were adjusted for factors that were considered to potentially influence both surgery type and body image outcomes, including age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, AJCC stage, body mass index (BMI), chemotherapy, radiation, and hormonal therapy.

Results

At the time of survey, time since diagnosis ranged from 7 months to 8 years, with an average of 3.6 years (SD=1.7 years). Overall, 63% of participants underwent BCS, 22% underwent CPM, and 15% underwent UM. Among those who had a mastectomy, 61% elected to undergo reconstruction, with 47% among those who received UM and 70% among those who received CPM. The average age among all participants was 60.8 years (SD=8.7). Those who underwent reconstruction were younger, on average, than those who had BCS or mastectomy without reconstruction. The majority of participants self-identified as white, non-Hispanic (90.4%). More than half were educated with a 4-year degree or higher (57%), with the highest proportion of 4-year degrees among women who underwent CPM with reconstruction (65%). Across surgery types, the majority of participants were diagnosed with either Stage 0 or Stage 1 breast cancer, though the proportion diagnosed with more advanced stages was highest among those who underwent UM (45% among UM without reconstruction, 41% among UM with reconstruction) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics according to surgery type among breast cancer survivors who underwent surgical treatment

| BCS | UM (no reconstruction) | UM with reconstruction | CPM (no reconstruction) | CPM with reconstruction | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Total N | 738 | 94 | 82 | 79 | 183 | |||||

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||||||

| 35–45 | 21 | 3% | 2 | 2% | 7 | 9% | 4 | 5% | 22 | 12% |

| 46–55 | 145 | 20% | 14 | 15% | 31 | 38% | 18 | 23% | 88 | 48% |

| 56–65 | 313 | 42% | 32 | 34% | 29 | 35% | 33 | 42% | 54 | 30% |

| 66–80 | 259 | 35% | 46 | 49% | 15 | 18% | 24 | 30% | 19 | 10% |

| Mean (SD) | 62.1 | (8.4) | 64.3 | (8.2) | 58.0 | (8.4) | 60.7 | (8.4) | 55.0 | (7.9) |

| AJCC Stage at diagnosis | ||||||||||

| 0 | 197 | 28% | 14 | 16% | 13 | 16% | 22 | 28% | 42 | 24% |

| I | 397 | 57% | 35 | 39% | 34 | 43% | 36 | 46% | 74 | 43% |

| II | 87 | 12% | 32 | 36% | 25 | 32% | 15 | 19% | 44 | 25% |

| III | 17 | 2% | 8 | 9% | 7 | 9% | 5 | 6% | 14 | 8% |

| Time since diagnosis | ||||||||||

| 7 months-2 years | 168 | 23% | 18 | 19% | 9 | 11% | 19 | 24% | 43 | 24% |

| 2.1 years-3.5 years | 221 | 30% | 26 | 28% | 29 | 35% | 20 | 25% | 39 | 21% |

| 3.6 years-5 years | 206 | 28% | 30 | 32% | 23 | 28% | 20 | 25% | 62 | 34% |

| >5 years | 143 | 19% | 20 | 21% | 21 | 26% | 20 | 25% | 39 | 21% |

| Mean (years) (SD) | 3.6 | (1.7) | 3.6 | (1.6) | 3.9 | (1.6) | 3.8 | (1.9) | 3.7 | (1.7) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 667 | 90% | 86 | 91% | 71 | 87% | 73 | 92% | 166 | 91% |

| Non-Hispanic black | 36 | 5% | 3 | 3% | 7 | 9% | 2 | 3% | 3 | 2% |

| Hispanic | 18 | 2% | 2 | 2% | 4 | 5% | 2 | 3% | 7 | 4% |

| Other | 17 | 2% | 3 | 3% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 3% | 7 | 4% |

| Education | ||||||||||

| High school/GED and lower | 106 | 14% | 18 | 19% | 5 | 6% | 12 | 15% | 18 | 10% |

| Associate’s Degree/Some college | 210 | 28% | 30 | 32% | 35 | 43% | 24 | 30% | 46 | 25% |

| 4 year degree or higher | 422 | 57% | 46 | 49% | 42 | 51% | 43 | 54% | 119 | 65% |

| Household income per person | ||||||||||

| <$25,000 | 148 | 21% | 34 | 38% | 14 | 18% | 18 | 23% | 35 | 20% |

| $25,000–$37,499 | 100 | 14% | 16 | 18% | 14 | 18% | 12 | 16% | 27 | 15% |

| $37,500–$74,999 | 247 | 35% | 24 | 27% | 31 | 40% | 31 | 40% | 75 | 42% |

| ≥ $75,000 | 209 | 30% | 15 | 17% | 19 | 24% | 16 | 21% | 42 | 23% |

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Never married | 40 | 5% | 8 | 9% | 3 | 4% | 4 | 5% | 7 | 4% |

| Legally married/living as married | 543 | 74% | 67 | 71% | 62 | 76% | 61 | 77% | 154 | 84% |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 155 | 21% | 19 | 20% | 17 | 21% | 14 | 18% | 22 | 12% |

| Parity | ||||||||||

| 0 | 156 | 21% | 24 | 26% | 10 | 12% | 20 | 25% | 31 | 17% |

| 1–2 | 357 | 48% | 39 | 41% | 50 | 61% | 34 | 43% | 107 | 58% |

| 3+ | 225 | 30% | 31 | 33% | 22 | 27% | 25 | 32% | 45 | 25% |

| Current BMI | ||||||||||

| <25 | 266 | 36% | 32 | 34% | 28 | 34% | 21 | 27% | 93 | 51% |

| 25–29.9 | 250 | 34% | 28 | 30% | 33 | 40% | 21 | 27% | 56 | 31% |

| 30+ | 222 | 30% | 34 | 36% | 21 | 26% | 37 | 47% | 34 | 19% |

| Number of first degree relatives with a history of breast cancer | ||||||||||

| Half-sister(s) only | 18 | 2% | 2 | 2% | 1 | 1% | 2 | 3% | 3 | 2% |

| 1 | 493 | 67% | 54 | 57% | 57 | 70% | 39 | 49% | 97 | 53% |

| >1 | 227 | 31% | 38 | 40% | 24 | 29% | 38 | 48% | 83 | 45% |

| Had chemotherapy | ||||||||||

| Yes | 173 | 26% | 38 | 41% | 40 | 49% | 29 | 37% | 89 | 49% |

| No | 501 | 74% | 55 | 59% | 42 | 51% | 50 | 63% | 94 | 51% |

| Had radiation | ||||||||||

| Yes | 669 | 91% | 16 | 17% | 11 | 14% | 10 | 13% | 27 | 15% |

| No | 64 | 9% | 77 | 83% | 69 | 86% | 67 | 87% | 150 | 85% |

| Had endocrine therapy | ||||||||||

| Yes | 485 | 67% | 65 | 70% | 51 | 64% | 36 | 47% | 93 | 52% |

| No | 241 | 33% | 28 | 30% | 29 | 36% | 40 | 53% | 87 | 48% |

Abbreviations: BCS=breast conserving surgery, UM = unilateral mastectomy, CPM = contralateral prophylactic mastectomy, BMI=body mass index

Satisfaction with mastectomy decision was high in both mastectomy subgroups, but was somewhat higher among those who underwent CPM (97%) than among those who underwent UM (89%) (Table 2). Few women reported dissatisfaction with their decision. The proportion reporting that they would have this mastectomy again was also high, with 96% and 97% in the UM and CPM groups, respectively, reporting that they definitely or probably would choose this mastectomy again.

Table 2.

Mastectomy and reconstruction satisfaction by surgery type

| UM | CPM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| N | % | N | % | |

| Satisfaction with decision to have mastectomy | ||||

| Satisfied | 155 | 89% | 254 | 97% |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 16 | 9% | 3 | 1% |

| Dissatisfied | 3 | 2% | 4 | 2% |

| Would have this mastectomy again | ||||

| Definitely/probably yes | 168 | 96% | 254 | 97% |

| Unsure | 4 | 2% | 5 | 2% |

| Definitely/probably not | 3 | 2% | 2 | 1% |

| Had Reconstruction | ||||

| No | 94 | 53% | 79 | 30% |

| Yes | 82 | 47% | 183 | 70% |

| Alloplastic / Implant | 44 | 65% | 141 | 83% |

| Autologous Reconstruction | 24 | 35% | 29 | 17% |

| Missing | 14 | 13 | ||

| Satisfaction with reconstruction | ||||

| Satisfied | 64 | 79% | 140 | 80% |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 2 | 2% | 8 | 5% |

| Dissatisfied | 15 | 19% | 28 | 16% |

| Complications | ||||

| No complications | 142 | 81% | 187 | 72% |

| 1 or more complicationsa | 33 | 19% | 73 | 28% |

| No Reconstruction | 21 | 64% | 25 | 34% |

| Had Reconstruction | 12 | 36% | 48 | 66% |

Abbreviations: UM = unilateral mastectomy, CPM = contralateral prophylactic mastectomy

Complications include bloodloss, hematoma, seroma and infection

Reconstruction was more common among women who had CPM (70%) than among those who had UM (47%). Among those who underwent reconstruction, the majority received implants, though autologous reconstruction was more common among those who had UM (35%) than CPM (17%). Satisfaction with reconstruction was similar in both groups, with 79% and 80% reporting that they were satisfied among those who underwent UM and CPM, respectively. Complications during or after surgery were reported by 28% of women who underwent CPM and 19% of women who underwent UM.

On a scale from 1 (“Strongly agree”) to 5 (“Strongly disagree”), scores on the item “I have felt self-conscious about my appearance” were significantly lower among women who had CPM without reconstruction (mean=2.9; 95% CI: 2.6, 3.2), reflecting greater self-consciousness in this group compared to all other surgery types (vs. BCS: p<0.001; vs. UM without reconstruction: p=0.043; vs. UM with reconstruction: p=0.026; vs. CPM with reconstruction: p=0.029) (Table 3). Those who underwent BCS had higher scores on this item (mean=3.7; 95% CI: 3.6, 3.8), reflecting less self-consciousness compared to women who underwent mastectomy (vs. UM without reconstruction: p=0.018; vs. UM with reconstruction: p=0.054; vs. CPM with reconstruction: p=0.005).

Table 3.

| BCS | UM (no reconstruction) | CPM (no reconstruction) | UM with reconstruction | CPM with reconstruction | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I have felt self-conscious about my appearance | 3.7 (3.6, 3.8) | 3.3 (3.0, 3.6) | 2.9 (2.6, 3.2) | 3.3 (3.0, 3.6) | 3.3 (3.1, 3.5) | <0.001 |

| I have felt less feminine as a result of having had breast cancer | 4.0 (3.9, 4.1) | 3.7 (3.4, 4.0) | 3.1 (2.8, 3.4) | 3.5 (3.2, 3.8) | 3.4 (3.2, 3.6) | <0.001 |

| Since having had breast cancer treatment, my body seems less whole | 4.0 (3.9, 4.2) | 3.5 (3.2, 3.8) | 3.2 (2.9, 3.5) | 3.5 (3.2, 3.8) | 3.5 (3.3, 3.8) | <0.001 |

| I feel less sexually attractive as a result of having had breast cancer | 3.7 (3.6, 3.9) | 3.3 (3.1, 3.6) | 2.8 (2.5, 3.1) | 2.9 (2.6, 3.2) | 3.0 (2.8, 3.3) | <0.001 |

| I am satisfied with the appearance of my breasts | 3.4 (3.3, 3.5) | 2.9 (2.6, 3.2) | 2.4 (2.1, 2.8) | 2.9 (2.6, 3.2) | 3.2 (3.0, 3.4) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: BCS=breast conserving surgery; UM=unilateral mastectomy; CPM=contralateral prophylactic mastectomy

Higher scores indicate better body image

Means adjusted for age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, stage, chemotherapy, radiation, hormonal therapy, BMI

Similarly, women who underwent CPM without reconstruction had lower scores on the item “I have felt less feminine as a result of having had breast cancer” (mean=3.1; 95% CI: 2.8, 3.4) than all other groups, although the comparison with CPM with reconstruction was not statistically significant (vs. BCS: p<0.001; vs. UM without reconstruction: p=0.001; vs. UM with reconstruction: p=0.031; vs. CPM with reconstruction: p=0.100). Scores were highest among women who underwent BCS (mean=4.0; 95% CI: 3.9, 4.1), suggesting better body image among these women compared to those who underwent mastectomy (vs. UM without reconstruction: p=0.090; vs. UM with reconstruction: p=0.007; vs. CPM with reconstruction: p<0.001).

Regarding the statement “Since having had breast cancer treatment, my body seems less whole,” scores were lower among women who underwent CPM without reconstruction (mean=3.2; 95% CI: 2.9–3.5) than among those who underwent BCS (p<0.001) or CPM with reconstruction (p=0.024), and non-significantly lower than women who received UM with reconstruction (p=0.085), or UM without reconstruction (p=0.073). Few women who underwent BCS expressed that their body seemed less whole after treatment (mean=4.0; 95% CI: 3.9, 4.2); scores were significantly higher among women who underwent BCS than among all other groups (vs. UM without reconstruction: p=0.001; vs. UM with reconstruction: p=0.002; vs. CPM with reconstruction: p<0.001).

Women who underwent CPM without reconstruction had the lowest scores on the item “I feel less sexually attractive as a result of having breast cancer” (mean=2.8; 95% CI: 2.5, 3.1), significantly lower than those of women who underwent BCS (p<0.001) or UM without reconstruction (p=0.005). Scores on this item were higher among women who underwent BCS compared to all mastectomy groups (vs. UM without reconstruction: p=0.020; vs. UM with reconstruction: p<0.001; vs. CPM with reconstruction: p<0.001). Women who underwent UM without reconstruction also had higher scores than women who underwent UM with reconstruction (p=0.036) or CPM with reconstruction (p=0.056).

Satisfaction with appearance of breasts was significantly higher among women who underwent BCS (mean=3.4; 95% CI: 3.3, 3.5) than among women who underwent CPM without reconstruction (p<0.001), UM without reconstruction (p=0.004), or UM with reconstruction (p=0.005). Those who underwent CPM without reconstruction expressed the lowest satisfaction (mean=2.4; 95% CI: 2.1, 2.8), significantly lower than that expressed by all other surgery groups (vs. UM without reconstruction: p=0.023; vs. UM with reconstruction: p=0.035; vs. CPM with reconstruction: p<0.001).

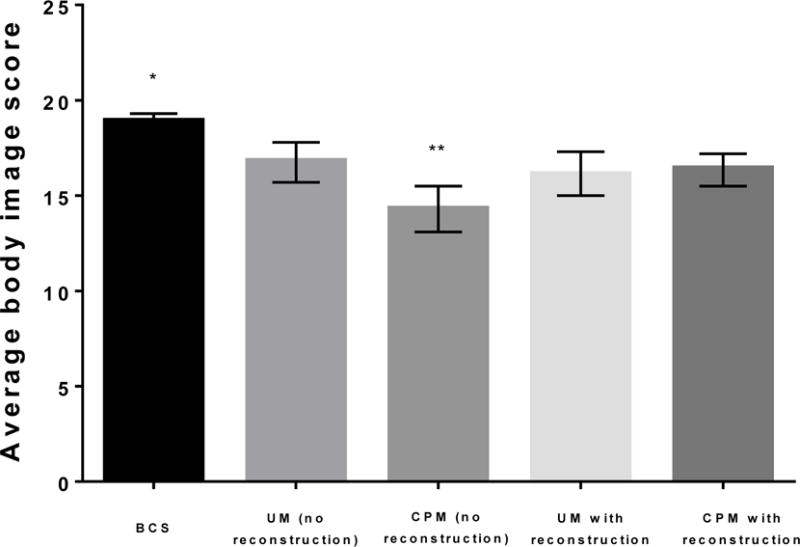

Total body image score, calculated as the sum of the five individual body image items, differed significantly according to surgery type (Figure 1). Women who underwent BCS had the highest average score (mean=18.9; 95% CI: 18.4, 19.3), significantly higher than that of all other surgery types (vs UM without reconstruction p=0.001; vs CPM without reconstruction: p<0.001; vs UM with reconstruction: p<0.001; vs CPM with reconstruction: p<0.001). Scores were lowest among women who underwent CPM without reconstruction (mean= 14.3; 95% CI: 13.1, 15.5), compared to all other surgery types (vs UM without reconstruction: p=0.001; vs UM with reconstruction: p=0.017; vs CPM with reconstruction: p=0.002).

Figure 1.

Total body image score according to surgery type. A higher score indicates better body image. Abbreviations: BCS=breast conserving surgery; UM=unilateral mastectomy; CPM=contralateral prophylactic mastectomy; *significantly higher than all other surgery types (all p<0.01); **significantly lower than all other surgery types (all p<0.05)

Discussion

Given the continued rise in CPM rates among U.S. women with early-stage breast cancer [7], it is increasingly important to consider long-term satisfaction and psychosocial effects associated with prophylactic breast surgery. In this study, women with both a personal and family history of breast cancer reported high satisfaction with their mastectomy decision, with the highest satisfaction reported by those who underwent CPM. However, lower satisfaction with body image was observed among women who underwent CPM without reconstruction.

The high proportion of women who underwent CPM in the current study (22%) reflects nationwide trends in recent years. A report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) showed a tripling of CPM rates between 2005 and 2013 among women diagnosed with unilateral breast cancer, while rates of unilateral mastectomies remained relatively constant [17]. The causes of this increase are not fully understood, though recent studies suggest that factors such as younger age, higher tumor stage, higher socioeconomic status, and family history are associated with CPM [7, 18–21]. The availability of reconstructive surgery and improvements in reconstructive techniques have also likely played a role [22–24]. In our sample, 70% of those who underwent CPM also had reconstruction, with younger age and higher education as the most defining characteristics of this subgroup.

Almost all women in our sample were satisfied with their decision to receive CPM and would choose to have this surgery again. While these results need to be interpreted with caution, due to the use of ad hoc survey questions that had not been previously validated, other recent studies have reported similar satisfaction levels among women who had CPM. Among women who underwent CPM at a single Pittsburgh hospital from 2000 to 2010, Soran et al recently reported that 97% were happy with CPM and 96% would make the same decision if given the choice again [11]. In a similar study, 83% of patients with a family history of breast cancer who elected CPM at Mayo Clinic between 1960 and 1993 were satisfied with their surgery, and 83% reported that they would have CPM again [12]. However, few studies have assessed whether these outcomes differ from those reported by women who opt to undergo UM, rather than CPM. In our sample, satisfaction was actually higher among women who elected to have CPM than among those who chose UM. Yet nearly all women, in both the CPM and UM groups, reported that they would make the same decision again. This suggests that the decision to undergo CPM is ultimately a personal choice, one which the majority of women remain satisfied with in the long term.

Our results also suggest that long-term satisfaction with the decision to have CPM may be largely driven by concerns unrelated to body image. In our sample, those who underwent CPM without reconstruction consistently had the lowest body image scores, despite high satisfaction with their decision to undergo CPM. Women in this group felt more self-conscious, less feminine, and less satisfied with the appearance of their breasts, on average, than women in other surgery subgroups. Though few studies have evaluated similar outcomes across surgery types, a small study from Sweden found that more than half of CPM patients reported problems with feeling self-conscious, less feminine, and less sexually attractive at 6 months after surgery, with similar proportions at 2 years [14]. In a cohort of patients who underwent CPM at Mayo Clinic, 25.6% and 26.0% reported decreases in femininity among those with and without reconstruction, respectively, while 31.5% and 37.9% reported decreases in satisfaction with body appearance approximately 10 years after CPM [25]. Among women who underwent CPM in the current study, some notable differences in body image were observed according to reconstruction. In particular, women who underwent CPM without reconstruction reported low satisfaction with the appearance of their breasts, while those who underwent CPM with reconstruction reported satisfaction nearly as high as that reported by women who underwent BCS. Other recent studies have also observed higher breast satisfaction among women who have undergone CPM with reconstruction as compared to CPM without reconstruction [21]. This may be explained by advances in reconstructive techniques in recent years, leading to improvements in cosmetic outcomes. For women who have elected to undergo CPM, our findings suggest that having reconstruction may be associated with better body image.

It is noteworthy that women who underwent BCS reported the highest satisfaction with body image, both overall and on all individual items that we evaluated. Although BCS is a less radical procedure than mastectomy, women who undergo BCS may still develop breast asymmetry due to the combined effects of surgery and fibrosis from radiotherapy [26], potentially leading to adverse effects on body image. In our sample, the vast majority of women who underwent BCS had either stage 0 or stage 1 cancer. Thus they may have had smaller tumors and smaller surgical areas, contributing to their higher body image. A number of studies have reported better body image among women who undergo BCS than among women who undergo mastectomy [27–29], while others have found little difference in body image across surgery types [30, 31]. Previous findings regarding other measures of cosmetic outcomes have also been conflicting. Though the measures used differ widely across studies, some suggest that cosmetic satisfaction may be best with BCS [32], while others have reported similar or better cosmetic outcomes for women who opt for mastectomy with reconstruction [33, 34]. Nevertheless, our findings demonstrate higher body image among women having BCS, an important factor for women to consider when choosing a course of surgical treatment.

An important strength of this study is the report of responses from a national sample of women treated at multiple institutions. Additionally, the majority of participants completed the survey at least two years after diagnosis; thus our results reflect long-term satisfaction outcomes. Our study also has limitations, including the use of survey measures which have not been subjected to testing of validity and reliability. Though we observed several statistically significant differences in body image across surgery types, the clinical significance of these findings is unclear. Given the retrospective survey design, recall bias is also possible. Furthermore, Sister Study participants included in this analysis were predominately non-Hispanic white and few were diagnosed at younger ages. Thus our findings may not be generalizable to younger women or more diverse populations. All Sister Study participants also had a sister who had previously been diagnosed with breast cancer, further limiting the generalizability of our findings. However, women with a family history of breast cancer represent an important population for studying surgical outcomes, as these women may be at higher risk of developing a second primary breast cancer in the contralateral breast [35], a factor which may influence long-term satisfaction with surgery decisions.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that most women with both a personal and family history of breast cancer are satisfied with their surgery choices in the long-term, including those who elect to undergo CPM. However, concerns related to body image may be more common among women who undergo CPM without reconstruction, particularly when compared to women who undergo BCS. Our findings regarding long-term satisfaction and body image outcomes may inform surgical decisions among women considering CPM.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the helpful comments of Dr. Quaker Harmon.

Funding: This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Z01-ES044005), the Centers For Disease Control and Prevention Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (KL2-TR001109). Dr. Lee was supported by National Institutes of Health (K07CA154850-01A1).

Abbreviations

- BCS

breast conserving surgery

- CPM

contralateral prophylactic mastectomy

- UM

unilateral mastectomy

Footnotes

Declarations:

Ethical approval and consent to participate: This survey was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the NIEHS/NIH as an amendment to the protocol for the Sister Study.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Consent for publication: Not applicable

Availability of data and materials: Data are not publicly available.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions: DPS, HBN designed research; DPS conducted research; CA, JYI, HBN analyzed data; All authors wrote the paper; All authors had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Spano JP, Azria D, Goncalves A. Patients’ satisfaction in early breast cancer treatment: Change in treatment over time and impact of HER2-targeted therapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;94(3):270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, Margolese RG, Deutsch M, Fisher ER, Jeong JH, Wolmark N. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1233–1241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, Greco M, Saccozzi R, Luini A, Aguilar M, Marubini E. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1227–1232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomez SL, Lichtensztajn D, Kurian AW, Telli ML, Chang ET, Keegan TH, Glaser SL, Clarke CA. Increasing mastectomy rates for early-stage breast cancer? Population-based trends from California. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(10):e155–157. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1032. author reply e158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahmood U, Hanlon AL, Koshy M, Buras R, Chumsri S, Tkaczuk KH, Cheston SB, Regine WF, Feigenberg SJ. Increasing national mastectomy rates for the treatment of early stage breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(5):1436–1443. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2732-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katipamula R, Degnim AC, Hoskin T, Boughey JC, Loprinzi C, Grant CS, Brandt KR, Pruthi S, Chute CG, Olson JE, et al. Trends in mastectomy rates at the Mayo Clinic Rochester: effect of surgical year and preoperative magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(25):4082–4088. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.4225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuttle TM, Habermann EB, Grund EH, Morris TJ, Virnig BA. Increasing use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for breast cancer patients: a trend toward more aggressive surgical treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(33):5203–5209. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrow M, Jagsi R, Alderman AK, Griggs JJ, Hawley ST, Hamilton AS, Graff JJ, Katz SJ. Surgeon recommendations and receipt of mastectomy for treatment of breast cancer. Jama. 2009;302(14):1551–1556. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrinton LJ, Barlow WE, Yu O, Geiger AM, Elmore JG, Barton MB, Harris EL, Rolnick S, Pardee R, Husson G, et al. Efficacy of prophylactic mastectomy in women with unilateral breast cancer: a cancer research network project. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(19):4275–4286. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurian AW, Lichtensztajn DY, Keegan TH, Nelson DO, Clarke CA, Gomez SL. Use of and mortality after bilateral mastectomy compared with other surgical treatments for breast cancer in California, 1998–2011. Jama. 2014;312(9):902–914. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soran A, Ibrahim A, Kanbour M, McGuire K, Balci FL, Polat AK, Thomas C, Bonaventura M, Ahrendt G, Johnson R. Decision making and factors influencing long-term satisfaction with prophylactic mastectomy in women with breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2015;38(2):179–183. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318292f8a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frost MH, Slezak JM, Tran NV, Williams CI, Johnson JL, Woods JE, Petty PM, Donohue JH, Grant CS, Sloan JA, et al. Satisfaction after contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: the significance of mastectomy type, reconstructive complications, and body appearance. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):7849–7856. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geiger AM, West CN, Nekhlyudov L, Herrinton LJ, Liu IL, Altschuler A, Rolnick SJ, Harris EL, Greene SM, Elmore JG, et al. Contentment with quality of life among breast cancer survivors with and without contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(9):1350–1356. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.9901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unukovych D, Sandelin K, Liljegren A, Arver B, Wickman M, Johansson H, Brandberg Y. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in breast cancer patients with a family history: a prospective 2-years follow-up study of health related quality of life, sexuality and body image. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(17):3150–3156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buchanan ND, Dasari S, Rodriguez JL, Lee Smith J, Hodgson ME, Weinberg CR, Sandler DP. Post-treatment Neurocognition and Psychosocial Care Among Breast Cancer Survivors. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(6 Suppl 5):S498–508. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopwood P, Fletcher I, Lee A, Al Ghazal S. A body image scale for use with cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(2):189–197. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steiner CAWA, Barrett ML, Fingar KR, Davis PH. Trends in Bilateral and Unilateral Mastectomies in Hospital Inpatient and Ambulatory Settings, 2005–2013. 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freedman RA, Kouri EM, West DW, Rosenberg S, Partridge AH, Lii J, Keating NL. Higher Stage of Disease Is Associated With Bilateral Mastectomy Among Patients With Breast Cancer: A Population-Based Survey. Clin Breast Cancer. 2016;16(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arrington AK, Jarosek SL, Virnig BA, Habermann EB, Tuttle TM. Patient and surgeon characteristics associated with increased use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in patients with breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(10):2697–2704. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0641-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yao K, Stewart AK, Winchester DJ, Winchester DP. Trends in contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for unilateral cancer: a report from the National Cancer Data Base, 1998–2007. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(10):2554–2562. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang ES, Locklear TD, Rushing CN, Samsa G, Abernethy AP, Hyslop T, Atisha DM. Patient-Reported Outcomes After Choice for Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.5427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yi M, Hunt KK, Arun BK, Bedrosian I, Barrera AG, Do KA, Kuerer HM, Babiera GV, Mittendorf EA, Ready K, et al. Factors affecting the decision of breast cancer patients to undergo contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3(8):1026–1034. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cassileth L, Kohanzadeh S, Amersi F. One-stage immediate breast reconstruction with implants: a new option for immediate reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2012;69(2):134–138. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182250c60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashfaq A, McGhan LJ, Pockaj BA, Gray RJ, Bagaria SP, McLaughlin SA, Casey WJ, 3rd, Rebecca AM, Kreymerman P, Wasif N. Impact of breast reconstruction on the decision to undergo contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(9):2934–2940. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3712-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boughey JC, Hoskin TL, Hartmann LC, Johnson JL, Jacobson SR, Degnim AC, Frost MH. Impact of reconstruction and reoperation on long-term patient-reported satisfaction after contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(2):401–408. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4053-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bajaj AK, Kon PS, Oberg KC, Miles DA. Aesthetic outcomes in patients undergoing breast conservation therapy for the treatment of localized breast cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(6):1442–1449. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000138813.64478.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janz NK, Mujahid M, Lantz PM, Fagerlin A, Salem B, Morrow M, Deapen D, Katz SJ. Population-based study of the relationship of treatment and sociodemographics on quality of life for early stage breast cancer. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(6):1467–1479. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-0288-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engel J, Kerr J, Schlesinger-Raab A, Sauer H, Holzel D. Quality of life following breast-conserving therapy or mastectomy: results of a 5-year prospective study. Breast J. 2004;10(3):223–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2004.21323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hopwood P, Haviland J, Mills J, Sumo G, J MB. The impact of age and clinical factors on quality of life in early breast cancer: an analysis of 2208 women recruited to the UK START Trial (Standardisation of Breast Radiotherapy Trial) Breast. 2007;16(3):241–251. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schover LR, Yetman RJ, Tuason LJ, Meisler E, Esselstyn CB, Hermann RE, Grundfest-Broniatowski S, Dowden RV. Partial mastectomy and breast reconstruction. A comparison of their effects on psychosocial adjustment, body image, and sexuality. Cancer. 1995;75(1):54–64. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950101)75:1<54::aid-cncr2820750111>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker PA, Youssef A, Walker S, Basen-Engquist K, Cohen L, Gritz ER, Wei QX, Robb GL. Short-term and long-term psychosocial adjustment and quality of life in women undergoing different surgical procedures for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(11):3078–3089. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Ghazal SK, Fallowfield L, Blamey RW. Comparison of psychological aspects and patient satisfaction following breast conserving surgery, simple mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36(15):1938–1943. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jagsi R, Li Y, Morrow M, Janz N, Alderman A, Graff J, Hamilton A, Katz S, Hawley S. Patient-reported Quality of Life and Satisfaction With Cosmetic Outcomes After Breast Conservation and Mastectomy With and Without Reconstruction: Results of a Survey of Breast Cancer Survivors. Ann Surg. 2015;261(6):1198–1206. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicholson RM, Leinster S, Sassoon EM. A comparison of the cosmetic and psychological outcome of breast reconstruction, breast conserving surgery and mastectomy without reconstruction. Breast. 2007;16(4):396–410. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reiner AS, John EM, Brooks JD, Lynch CF, Bernstein L, Mellemkjaer L, Malone KE, Knight JA, Capanu M, Teraoka SN, et al. Risk of asynchronous contralateral breast cancer in noncarriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with a family history of breast cancer: a report from the Women’s Environmental Cancer and Radiation Epidemiology Study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(4):433–439. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]