Abstract

Background

A critical assessment of current health care practices, as well as the training needs of various health care providers, is crucial for improving patient care. Several approaches have been proposed for defining these needs with attention on communication as a key competency for effective collaboration. Taking our cultural context, resource limitations, and small-scale setting into account, we researched the applicability of a mixed focus group approach for analysis of the communication between doctors and nurses, as well as the measures for improvement.

Study objective

Assessment of nurse-physician communication perception in patient care in a Caribbean setting.

Methods

Focus group sessions consisting of nurses, interns, and medical specialists were conducted using an ethnographic approach, paying attention to existing communication, risk evaluation, and recommendations for improvement. Data derived from the focus group sessions were analyzed by thematic synthesis method with descriptive themes and development of analytic themes.

Results

The initial focus group sessions produced an extensive list of key recommendations which could be clustered into three domains (standardization, sustainment, and collaboration). Further discussion of these domains in focus groups showed nurses’ and physicians’ domain perspectives and effects on patient care to be broadly similar. Risks related to lack of information, knowledge sharing, and professional respect were clearly described by the participants.

Conclusion

The described mixed focus group session approach for effectively determining current interprofessional communication and key improvement areas seems suitable for our small-scale, limited resource setting. The impact of the cultural context should be further evaluated by a similar study in a different cultural context.

Keywords: interprofessional communication, focus group sessions, nurses’ perspective, cultural context, quality of care

Introduction

The successful implementation of competency based medical training (and practice) requires a seamless alignment with the culture and local health care needs of a community. In countries with limited economic and human resources, a critical assessment of current health care practices as well as the training needs of various health care providers is crucial for defining the required cadres for program design and implementation.1,2

Several studies in the literature have described different strategies which investigators have used to obtain the information required to address these needs. Some of these strategies have included conducting interviews with stakeholders, Delphi studies, observational studies or consultation with expert panels.3 Further scrutiny of the various competency domains in the health care (and medical educational) literature has also shown that “communication” is a universal key competency that health care professionals need to be able to collaborate effectively. Communication in this context is described as an individual professional’s ability to converse effectively with other health care professionals, patients, and families in their communities.4 However, in all of these interactions, the context of the health care professional and local culture in which they are working, is expected to be taken into account.1,2

Collaboration in health care can be described as the capability of every health care professional, to effectively embrace complementary roles within a team, work cooperatively, share the responsibilities for problem-solving, and make the decisions needed to formulate and carry out plans for patient care.5,6 It has been observed that the interprofessional collaboration between physicians, nurses, and other members of the health care team increases the collective awareness of each others’ (type of) knowledge and skills. Furthermore, this contributes to the quality of care through the continued improvement in decision-making.7

Deming argues that trust, respect, and collaboration are inherent to the effectiveness of any team.8 He believed that teamwork is central to a system where its employees work for and together to achieve a common goal. According to O’Daniel and Rosenstein, it is imperative that an interdisciplinary approach be used when considering teamwork models in health care.9 Unlike a multidisciplinary approach, interdisciplinary approaches have the advantage of coalescing a joint effort from different disciplines (with a common goal) to address a patient’s health care problem. This pooling of specialized services, is what contributes to lasting and effective integrated interventions.9 In addition, it has been demonstrated that improved interprofessional collaboration and communication are important factors which health care workers consider to be crucial in improving clinical effectiveness and job satisfaction.10

The communication between nurses and physicians is considered to be a key factor for effective interprofessional collaboration and thus, for the assurance of the quality of care. Therefore the reliable appraisal of communication and collaboration in a clinical work environment is crucial for improvement and sustainment of quality of care. It is also dependent on the social exchange within a specific (cultural) context11 which is of relevance to the micro system in which the medical professional performs in resource limited environments.2 Within this context, the authors were interested in finding out the nature of the interactions between communication and collaboration in relation to the cultural settings in which they occurred.12 This query constituted the first rationale for the need for further investigation.

To date, several approaches have been used to explore different domains of communication which need improvement within the nurse-physician collaborations. Most of these studies have relied on the use of extensive questionnaires which professionals have had to answer.13,14 The reports from many of these studies have shown that the perceptions of various professional groups differ with respect to the quality of the current (interprofessional) communication. This has created challenges in identifying those areas which actually require improvement as well as defining the training programs needed to achieve them.13,15

In the authors’ continued efforts to assure the quality of care in their local setting, they recently described the strategic role of competency based medical education in health care reform.1 The conditions proposed for the success of such a program included the need to tailor the curriculum to the specific needs of the local resource limited, Caribbean context. These conditions were based on the observations from a separate study which investigated the cultural context of their local setting based on Hofstede’s theory of how countries’ cultures influenced workplace values.16 Using this theory of cultural dimensions, the authors analyzed the culture of their local context and described it as masculine, collective, and with a high power distance index.17 This classification contributed to the second rationale for this study, which was aimed at investigating whether the local culture’s high power index and masculinity had any influence on the quality of collaboration between the different health care providers e.g., nurses and physicians within the organization. The authors’ assumptions were that by gaining more insight into the nature and extent of these interactions, it would be possible to design better solutions for the local health care problems. Therefore in this paper, interprofessional collaboration was explored within the cultural climate of a hospital organization in a resource limited Caribbean environment. The authors were interested in the perceived quality of communication between stakeholders as well as the measures which could be used to improve interprofessional collaboration.

Methods

The study was performed at the St. Elisabeth Hospital Curaçao, the sole general hospital on the Dutch Caribbean island of Curaçao (population 150,000) with 300 beds. The hospital provides services in all major clinical specialties, and also offers adult, pediatric, and neonatal intensive care. The hospital, as an educational setting, is affiliated to a number of tertiary medical institutions in the Netherlands and provides accredited residency and pre-residency training for Dutch medical students of the University Medical Center Groningen.18,19

In December 2014, six focus group sessions were conducted among the medical and nursing staff at the St. Elisabeth Hospital, Curaçao. A total of 61 health care professionals participated in the study and consisted of nurses, medical interns, and medical specialists. After voluntary registration by participants, focus discussion groups (FDG) were formed of 10–11 participants. Each FDG consisted of 1–2 medical specialists, 1–2 interns, and 8–9 nurses. FDG sessions were held sequentially within a week. We used an ethnographic approach for this study, as our objective was to understand the different professional cultures, the quality of the interactions between them, and how they contributed to the quality and safety of patient care. We were particularly interested in understanding the nature of the interactions, bearing in mind that values within cultures and professional groups have been found to impact the climate and structure of organizations.16,17,20 The domain of interprofessional collaboration which we focused on, was communication and we paid specific attention to:

local experience with the existing communication skills;

which improvements would be recommended;

prioritizing these recommendations.

Our choice for using focus group sessions was based on the fact that it is a well-established qualitative methodology for eliciting the respondents’ perspectives, and that the interactions between the participants would provide more information and probably even trigger the formulation of new ideas on the theme.1,17 The quality of group interviews was based on the authors’ experience in qualitative medical education research and use of FDG in the local setting as previously described,1,19 and on standards for qualitative interview as outlined by the Department of Primary Care at the University of Oxford. All focus groups were conducted in individual conference rooms and lasted approximately 45–90 minutes. The participation of the medical and nursing staff members was voluntary and they all consented in writing to be interviewed. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Institutional Review Board of the St. Elisabeth Hospital.

The sessions were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim immediately following the interview. Data were iteratively read and analyzed by thematic synthesis method, in which text coding was first performed, followed by the development of descriptive themes, and then generation of analytical themes in the last stage. We chose this approach because it is suitable for analyzing relatively unstructured, text-based data in an inclusive and rigorous manner.

Results

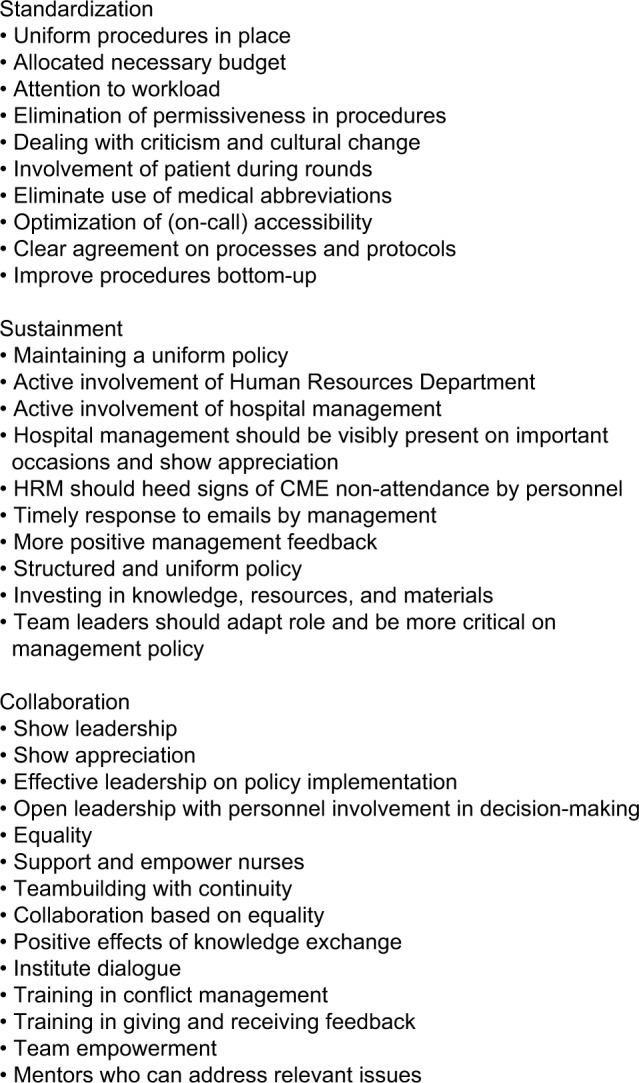

The focus group meetings were held during the period of a week in December of 2014. The outcome of the discussion within the focus groups produced an extensive list of key recommendations which are presented in Figure 1. The main findings from the initial analysis of the list of key recommendations were clustered into three domains:

uniformity in sharing and upholding of procedures (standardization);

maintaining and sharing of knowledge (sustainment);

collaboration based on professional respect (collaboration).

These domains were further discussed in the same focus groups resulting in descriptions of current perspectives on the common themes and their effects as formulated by physicians and nurses respectively. Other outcomes were also identified from the interview but were related to organizational management (and not directly to interprofessional communication) and therefore were left out of our further analysis of the essential domains for interprofessional communication. The perspectives of the nurses and physicians, as well as the perceived effects on the quality of interprofessional collaboration are presented in Table 1. A further in-depth analysis of the relationships between the three domains are described in more detail in the following sections.

Figure 1.

Key list of recommendations.

Abbreviations: CME, continuous medical education; HME, human resource management.

Table 1.

Key communication domains

| Communication domain | Nurses | Physicians |

|---|---|---|

| Uniformity in sharing and upholding of procedures (standardization) | ||

|

| ||

| Current perspective | Ambiguities (unclearness) in patient treatment plan is experienced as a major obstacle. Lack of procedures or uniformity in procedures used. Searching for solutions to missing or unclear information is time-consuming. Lack of autonomy in own professional tasks. Established agreements with other departments (laboratory, radiology) are not upheld and hinder collaboration. |

Searching for information is time-consuming. Patient information is often incomplete. Unclear policy within departments. Communication gap with other health care providers. Nurses are often unapproachable. |

| Effects | Increased risk for errors. Lack of efficiency. Loss of motivation. Dissension and isolation. Suboptimal patient care. |

Time-consuming. Higher margin for errors. Dissension and discouragement (loss of motivation). |

|

| ||

| Maintaining and sharing of knowledge (sustainment) | ||

|

| ||

| Current perspective | Lack of access to the knowledge of medical specialists and interns (knowledge sharing). Sense of a frequent need to gain knowledge from the medical specialist. The hierarchical structure of medical team causes ambiguity in approach to patient care. Nurses’ knowledge unavailable to physician. One-sided relationship. |

Lack of cohesion. Individualism in approach to solving clinical problems and performing procedures (silos). Inadequate consultation within and between professional groups (physician, nurses). Loss of information. |

| Effects | Suboptimal patient care. Lack of motivation. High personnel turnover, increased risk for errors. Lack of sustainability. |

Waste of time. Loss of motivation and knowledge. Lack of efficiency. |

|

| ||

| Collaboration based on professional respect (collaboration) | ||

|

| ||

| Current perspective | Unequal professional relationship between physician and nurses. Absence of an environment for asking questions. Suboptimal collaboration. |

Unequal professional relationship between physician and nurses. Poor acknowledgment of nurses’ professional autonomy by peers. Insufficient knowledge sharing. |

| Effects | Low motivation. Increased work absenteeism. High personnel turnover. Suboptimal patient care. Negative atmosphere. Disagreement. Waste of time. |

Higher risk for errors. Loss of time and motivation. Suboptimal patient care. Fragmentation. |

Uniformity in sharing and upholding of procedures (standardization)

In cases where procedures were not being conducted or upheld in professional collaboration, there is the serious risk of losing domain related knowledge.

From the nurses’ perspective, lack of clarity in patients’ treatment plans was experienced as a major obstacle. The existing agreements with other departments (laboratory, radiology) were not being upheld and hinder collaboration.

As possible effects, increased risk for errors, lack of efficiency, loss of motivation, dissension and isolation resulting in suboptimal patient care were mentioned.

From the physicians’ perspective, the time-consuming search for information (which was often incomplete), lack of clear department policies coupled with the apparent unapproachability of nurses were reported as major obstacles.

These time-consuming endeavors resulting in higher incidence of errors were mentioned as negative effects. As a result, demotivation and dissent could be expected.

Maintaining and sharing of knowledge (sustainment)

A perceived lack of professional respect constrained knowledge sharing within and between professional teams.

The nurses experienced that there was insufficient knowledge sharing between them, the medical specialists, and interns. They perceived an unclear approach in treatment plans due to the hierarchical structure of the professional relationship of physicians, which fostered a one-sided relationship. Consequently, the perceived knowledge and experiences of the nurses were not effectively shared with the physicians.

The possible effects described were suboptimal patient care as a result of the nurses’ knowledge not being available to the physician, and a lack of motivation. High personnel turnover and increased risk for errors can be expected with lack of sustainability of the care process.

From the physicians’ perspective a lack of team cohesion was observed, characterized by performing procedures and seeking for solutions to problems individually rather than collectively in teams.

It was anticipated that a loss of time and motivation, as well as lack of efficiency could therefore be expected. Also, this could result in a loss of information which is crucial for optimal patient care.

Collaboration based on professional respect (collaboration)

The existent knowledge gap (by virtue of the different disciplines) fortified the experience of lack of respect among professional teams. This was felt to also hinder optimal collaboration and consultation for procedures.

For the nurses, the perceived lack of professional respect and hostile attitude of medical specialists and/or interns in the treatment process hindered a safe environment for asking questions. Low motivation and increased work absenteeism could result with high personnel turnover. As a result suboptimal patient care was seen as a serious negative effect.

From the physicians’ perspective the lack of professional respect for nurses and peers (especially junior physicians) can lead to insufficient knowledge sharing. This environment creates a higher risk for errors. The ensuing loss of time and motivation can lead to suboptimal patient care.

These results show the current perspectives and possible effects of the three essential domains, as formulated by the nurses and physicians during the focus group sessions, to be broadly similar. Both nurses and physicians accentuate the necessity for improvement of these essential domains for achieving better interprofessional communication and patient quality care.

Discussion

In this paper, the investigators set out to investigate the quality of interprofessional collaboration within a small-scale resource limited health care setting. The authors were interested in understanding the perceived impact of communication on interprofessional collaboration and the role, if any, of the cultural context on the quality of interprofessional collaboration. For this purpose, their hospital organization was an ideal test model as it was situated in Curaçao, which is representative of a small-scale, resource limited health care environment in the Caribbean.

Several methods have been used to assess the perceived physician-nurse communication level and its shortcomings. Mostly surveys based on self report questionnaires have been used to address the different perspectives.13,21,22 Within self report surveys many options exist, further complicating comparability of study results.15 However, it has been well-described in literature that different medical professionals (e.g., nurses and physicians) have different perspectives on the quality of their interprofessional communication and factors affecting effective communication.13,22 In small-scale settings the use of questionnaires for assessing interprofessional communication has been reported for an intensive care unit department (making use of separate questionnaires)22 with stark differences in perspectives of nurses and physicians.

These observed differences in perception of interprofessional communication are an important factor affecting priority topics’ delineation, design and implementation of training programs for effectively addressing (unsatisfactory) local interprofessional communication. These shortcomings of self report studies can be avoided by making use of focus group session discussions which can lead to common formulated targets regarding interprofessional communication. The focus group method described in this paper by nature stimulates a uniform team approach in all areas of patient care by having the participants discuss the aforementioned issues (including local cultural challenges), and jointly formulate important domains for improvement. To our knowledge this report is the first to address this issue making use of a mixed focus group method. Interestingly, Minamizono et al. recently emphasized the positive effects of regular interprofessional meetings to improve (patient) information sharing and quality of care, which is also in line with World Health Organization recommendations.14

The focus group sessions described in this manuscript (starting with a key list of recommendations) resulted in the three major domains which were used to address the improvement of interprofessional communication and concomitantly patient care, namely:

uniformity in sharing and upholding of procedures (standardization);

maintaining and sharing of knowledge (sustainment);

collaboration based on professional respect (collaboration).

Further elaboration of these domains in the focus group sessions (current perspectives and effects) resulted in clear descriptions of the perspectives and expected effects between nurses and physicians. Shortcomings in communication around patient care could also be linked to organizational and individual factors (work attitude and personal behavior). Our results align with other studies which demonstrate that mutual understanding of team treatment plans,23 interprofessional meetings,14 and interprofessional attitude24,25 are crucial areas of patient care which need improvement. For optimal collaborative interactions, sharing of skills and knowledge is necessary and leads to high quality patient care. The perception of professional respect on the other hand, constitutes a key component for effective communication.26 Also, as others have proposed, sharing of patient information should be the prioritized point of focus in communication improvement.13

Interestingly, the three major domains described in this paper correlate with the major risk factors for patient safety which have been described in the literature, i.e., lack of critical information and misinterpretation of information.27 These results clearly indicate the need for training and designing improvement programs which focus on interprofessional communication for all health care professionals involved. Investing in clear procedures for team treatment plans, effective colleague interactions (at meetings) should improve interprofessional communication as well as the quality of patient care.14 In-house continuous education programs should also focus on these areas. Specific techniques and structural communication protocols like SBAR – situation, background, assessment, and recommendation25 – should be introduced to effectively facilitate communication about patients.23

One of the domains of professional medical training requiring extra attention is the area of interprofessional communication.2 The recent introduction of patient centered approach in health care has been an important development which requires effective teamwork and interprofessional communication.2 Several studies on adverse events and incidents have shown that positive outcomes in the quality of patient care have been associated with effective interprofessional communication.12–14 Studies about intensive care unit team members have also shown that acknowledging the concerns of every member in the health care team has a positive effect on patient outcome.21

With respect to organizational culture, most health care environments are hierarchical in nature, with physicians being at the top of that hierarchy. It is taken as a given that such environments are collaborative and that communication is open. Unlike the physicians however, nurses and other supporting staff often perceive problems in communication.28,29 In a review of the literature on organizational communication, (vertical) hierarchies were identified as a common barrier to effective communication and collaboration.28,30–33 It was also found that differences in these vertical hierarchies led to communication failures between health care teams. These failures were linked to concerns with upward influence, role conflict, ambiguity, and struggles with interpersonal power and conflict.12

In the opinion of the authors, the cultural context in which a health organization is located contributes significantly to the quality of the organizational culture and the perceived quality of communication and interprofessional collaboration.16 The authors believe, that a good grasp of the nature and extent of this phenomenon is crucial for tackling local challenges and developing effective interventions to improve health care processes. According to Hofstede et al., the culture of a community can be described as “the collective programming of the mind distinguishing the members of one group or category of people from others”.16 Using six dimensions, a contextual representation for this definition was provided and included the “power distance index” i.e., the degree to which the less powerful in society accept and expect that power is distributed unequally, “individualism versus collectivism” i.e., the preference for a loosely-knit social framework in which individuals take care of self as opposed to the tightly-knit collective framework. Other dimensions included, “masculinity versus femininity” i.e., the preference in society for achievement, heroism, and assertiveness as opposed to cooperation, modesty, caring for the weak and quality of life, “uncertainty avoidance index” i.e., the degree to which society feels uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity, and the recently included dimensions of “long-term orientation versus short-term normative orientation” and “indulgence versus restraint” dimension.

Drawing back on our findings in this study, the masculinity, collectivity, and high power distance index in our setting may have affected the nature of the professional culture and communication we identified. Especially when we closely reflect on the different ways the nurses perceived the collaboration and learning opportunities with the doctors and vice versa.17 A further analysis of the described mixed focus group approach in a different cultural context could therefore serve to show the general applicability of this method and the cultural effects on the perceived key improvements in interprofessional communication.

In conclusion, the results in this paper demonstrate the importance of continuous improvement in communication and corroborate the existent calls for more leadership (development) in health care delivery and education.3,22 A competency based approach to teamwork learning and development has also been advocated.2 This approach fits well within the educational intervention for communication and continuous professional development in our hospital.1 Finally, the use of focus group sessions as a platform for continuous appraisal should effectively support the local endeavors and effectively substitute for the use of (complicated) questionnaires in small-scale settings, effectively addressing local hierarchical and cultural challenges among medical professionals.14

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant of the Netherlands Caribbean Foundation for Clinical Higher Education (NASKHO).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Busari JO, Duits AJ. The strategic role of competency based medical education in health care reform: a case report from a small scale, resource limited, Caribbean setting. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:13. doi: 10.1186/s13104-014-0963-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–1958. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clay-Williams R, Braithwaite J. Determination of health-care teamwork training competencies: a Delphi study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2009;21(6):433–440. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzp042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank JR, Snell LS, Sherbino J, editors. CanMEDS 2015 Physician Competency Framework. Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; Ottawa: 2015. [Accessed April 16, 2017]. Available from: www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/common/documents/canmeds/framework/can-meds_reduced_framework_e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagin CM. Collaboration between nurses and physicians: no longer a choice. Acad Med. 1992;67(5):295–303. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baggs JG, Schmitt MH. Collaboration between nurses and physicians. Image: the Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1988;20(3):145–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1988.tb00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensen C, Larson JR., Jr Collaborative medical decision making. Med Decis Making. 1993;13(4):339–346. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9301300410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deming WE. Out of crisis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Center for Advanced Engineering Study; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Daniel M, Rosenstein AH. Professional Communication and Team Collaboration. In: Hughes RG, editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. pp. 1–14. Chapter 33. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flin R, Fletcher G, McGeorge P, Sutherland A, Patey R. Anaesthetists’ attitudes to teamwork and safety. Anaesthesia. 2003;58(3):233–242. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eichbaum Q. The problem with competencies in global health education. Acad Med. 2015;90(4):414–417. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutcliffe KM, Lewton E, Rosenthal MM. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186–194. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200402000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hailu FB, Kassahun CW, Kerie MW. Perceived nurse-physician communication in patient care and associated factors in public hospitals of Jimma Zone, South West Ethiopia: cross sectional study. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0162264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minamizono S, Hasegawa H, Hasunuma N, Kaneko Y, Motohashi Y, Inoue Y. Physician’s perceptions of interprofessional collaboration in clinical training hospitals in Northeastern Japan. J Clin Med Res. 2013;5(5):350–355. doi: 10.4021/jocmr1474w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ang WC, Swain N, Gale C. Evaluating communication in healthcare: Systematic review and analysis of suitable communication scales. Journal of Communication in Healthcare. 2013;6(4):216–222. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofstede G, Hofstede GJ, Minkov M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. Revised and Expanded 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill USA; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Busari JO, Verhagen EA, Muskiet FD. The influence of the cultural climate of the training environment on physicians’ self-perception of competence and preparedness for practice. BMC Med Educ. 2008;8:51. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-8-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuks JB. The bachelor-master structure (two-cycle curriculum) according to the Bologna agreement: a Dutch experience. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2010;27(2) doi: 10.3205/zma000670. Doc33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koeijers JJ, Busari JO, Duits AJ. A case study of the implementation of a competency-based curriculum in a Caribbean teaching hospital. West Indian Med J. 2012;61(7):726–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hofstede G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ten Have EC, Hagedoorn M, Holman ND, Nap RE, Sanderman R, Tulleken JE. Assessing the quality of interdisciplinary rounds in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2013;28(4):476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang LP, Harding HE, Tennant I, et al. Interdisciplinary communication in the intensive care unit at the University Hospital of the West Indies. West Indian Med J. 2010;59(6):656–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scalise D. Clinical communication and patient safety. Hosp Health Netw. 2006;80(8):49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bryon E, Gastmans C, de Casterlé BD. Nurse-physician communication concerning artificial nutrition or hydration (ANH) in patients with dementia: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(19–20):2975–2984. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.04029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renz SM, Boltz MP, Wagner LM, Capezuti EA, Lawrence TE. Examining the feasibility and utility of an SBAR protocol in long-term care. Geriatr Nurs. 2013;34(4):295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casanova J, Day K, Dorpat D, Hendricks B, Theis L, Wiesman S. Nurse-physician work relations and role expectations. J Nurs Adm. 2007;37(2):68–70. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200702000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tjia J, Mazor KM, Field T, Meterko V, Spenard A, Gurwitz JH. Nurse-physician communication in the long-term care setting: perceived barriers and impact on patient safety. J Patient Saf. 2009;5(3):145–152. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3181b53f9b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weick KE. Puzzles in organizational learning: an exercise in disciplined imagination. British Journal of Management. 2002;13:S7–S16. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations . The Joint Commission guide to improving staff communication. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission Resources; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dansereau F, Markham SE. Superior-subordinate communication: multiple levels of analysis. In: Jablin FM, Putnam LL, Roberts KH, et al., editors. Handbook of organizational communication. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1987. pp. 343–388. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frost PJ. Power, politics, and influence. In: Jablin FM, Putnam LL, Roberts KH, et al., editors. Handbook of organizational communication. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1987. pp. 503–548. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jablin FM. Task Force relationships: a life-span perspective. In: Knapp ML, Miller GR, editors. Handbook of interpersonal communication. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1987. pp. 389–420. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stohl C, Redding WC. Messages and message exchange processes. In: Jablin FM, Putnam LL, Roberts KH, editors. Handbook of organizational communication. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1987. pp. 451–502. [Google Scholar]