Abstract

Despite evidence of a relation between borderline personality disorder (BPD) pathology and physical health problems, the mechanisms underlying this relation remain unclear. Given evidence that emotion dysregulation may affect physical health by altering physiological functioning, one mechanism that warrants examination is emotion dysregulation. This study examined BPD symptoms as a prospective predictor of physical health symptoms 8-months later and the mediating role of emotion dysregulation in this relation. Participants completed three assessments over an 8-month period, including a BPD diagnostic interview. Results of analyses examining baseline predictors of later physical health symptoms revealed a significant unique association between baseline BPD symptom severity and physical health symptoms 8-months later, above and beyond baseline physical health symptoms, depression and anxiety symptoms, and emotion dysregulation. Moreover, structural equation modeling revealed a significant indirect relation of BPD symptoms at Wave 1 to physical health symptoms at Wave 3 through emotion dysregulation at Wave 2.

Keywords: emotion regulation, borderline personality, physical health, health problems, emotion dysregulation, longitudinal

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a serious mental health problem associated with severe functional impairment (Skodol, Gunderson, McGlashan et al., 2002), substantial mental and physical disability (particularly in women; Grant et al., 2008), high rates of co-occurring psychiatric disorders (Skodol, Gunderson, Pfohl et al., 2002), elevated risk for a variety of self-destructive and health-compromising behaviors (Linehan, 1993; Skodol, Gunderson, Pfohl et al., 2002), and a high rate of mortality by suicide (10%; Work Group on Borderline Personality Disorder, 2001). Although the interpersonal and emotional consequences of BPD are well documented (e.g., Clifton, Pilkonis, & McCarty, 2007; Gratz et al., 2014; Herr, Hammen, & Brennan, 2008; Hoffman et al., 2005; Rosenthal et al., 2008), less is known about the physical health consequences of BPD or the extent to which BPD symptoms increase the risk for future physical health problems. This is an important area of inquiry, however, given the well-established relation between physical and mental health (Kiecolt-Glaser, McGuire, Robles, & Glaser, 2007; Salovey, Rothman, Detweiler, & Steward, 2000), the significant economic and societal costs associated with chronic medical problems (Hoffman, Rice, & Sung, 1996; Yach, Hawkes, Gould, & Hofman, 2004), and the relation between co-occurring physical health conditions and increased suicide risk among individuals with BPD (El-Gabalawy, Katz, & Sareen, 2010).

A small but growing body of research suggests an association between BPD and a broad range of physical health problems (see Dixon-Gordon, Whalen, Layden, & Chapman, in press). For example, studies using large, representative community samples have found a unique association between BPD and numerous physical health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, hypertension/arteriosclerosis, hepatic disease, gastrointestinal disease, arthritis, and venereal disease (e.g., El-Gabalawy et al., 2010; Moran et al., 2007), as well as various chronic pain conditions (e.g., musculoskeletal pain, headache; Braden & Sullivan, 2008; McWilliams & Higgins, 2013). Moreover, results of a large-scale epidemiological study of BPD revealed a unique association between BPD and both overall physical disability and the specific domains of physical functioning, bodily pain, and general health (Grant et al., 2008).

Heightened physical health problems have also been observed in clinical samples of predominantly female BPD patients. For example, in a large-scale longitudinal study of BPD patients, Frankenburg and Zanarini (2004) found that the failure to remit from BPD over a 6-year period was associated with heightened risk for a variety of chronic physical health problems, including chronic fatigue, fibromyalgia, temporomandibular joint syndrome, obesity, osteoarthritis, diabetes, hypertension, back pain, and urinary incontinence. Moreover, non-remitted BPD patients were more likely to utilize costly forms of medical treatment (i.e., emergency room visits and/or medical hospitalizations), as well as pain and sleep medications for sustained periods (Frankenburg & Zanarini, 2004). Similar associations between persistent BPD symptoms and negative physical health outcomes were found at the 10-year follow-up as well, with non-remitted BPD associated with increased risk for obesity, osteoarthritis, diabetes, and urinary incontinence, as well as heavy use of sleep and pain medications (Keuroghlian, Frankenburg, & Zanarini, 2013). Despite accumulating evidence linking BPD to poor physical health outcomes, however, the mechanisms underlying this relation remain unclear. Research in this area may improve our understanding of the ways in which BPD symptoms contribute to physical health problems and highlight potential targets for intervention to prevent the occurrence of these problems.

One mechanism that warrants examination in this regard is emotion dysregulation. Considered to be one of the most central and defining features of BPD, emotion dysregulation is thought to underlie many of the symptoms and associated difficulties of this disorder (Koenigsberg et al., 2009; Linehan, 1993). Although research in this area has generally focused on the role of emotion dysregulation in the emotional, behavioral, and interpersonal problems associated with BPD (Dixon-Gordon, Gratz, Breetz, & Tull, 2013; Gratz, Breetz, & Tull, 2010; Gratz et al., 2014; Koenigsberg et al., 2001; Linehan, 1993), emerging evidence suggests that emotion dysregulation may have a deleterious effect on physical health as well. Specifically, maladaptive emotion regulation is positively associated with increased sympathetic activation and physiological responding in response to stressors (Gross, 1998) and when engaging in emotionally evocative tasks (Gross & Levenson, 1997). Conversely, adaptive emotion regulation is associated with decreased physiological and HPA-axis responding (Abelson, Liberzon, Young, Khan, 2005; Goldin, McRae, Ramel, & Gross, 2008). The influence of emotion regulation on physiological activation may be particularly relevant to physical health outcomes given the robust association between allostatic load, or the prolonged physiologic response to stress (e.g., chronic sympathetic nervous system and HPA axis activation), and the development of chronic health conditions (Cohen, Janicki-Deverts, & Miller, 2007; McEwen, 1996). Indeed, allostatic load has been implicated in numerous health conditions such as cardiovascular disease, upper respiratory tract infections, asthma, and autoimmune diseases (Cohen et al., 2007). Thus, the heightened emotion dysregulation associated with BPD may be one mechanism underlying the worse physical health outcomes in this population. Notably, however, despite both robust empirical support for the role of emotion dysregulation in BPD-related difficulties and strong theoretical support for the relevance of emotion dysregulation to poor physical health, no studies have examined the role of emotion dysregulation in the relation between BPD symptoms and physical health symptoms.

The goals of this study were to examine BPD symptoms as a prospective predictor of physical health symptoms within a community sample of young adult women, and explore the mediating role of emotion dysregulation in the relation between BPD symptoms and later physical health symptoms. To this end, we examined the unique relation of baseline BPD symptoms to physical health symptoms 8-months later, above and beyond other relevant baseline predictors (including physical health symptoms, depression and anxiety symptoms, emotion dysregulation, and relevant demographics). We also examined the indirect relation of BPD symptoms to physical health symptoms through intermediary levels of emotion dysregulation. We hypothesized that BPD symptoms would predict greater physical health symptoms 8-months later (above and beyond other baseline predictors), and that the relation of BPD symptoms to later physical health symptoms would be indirect through emotion dysregulation.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from a large prospective study of emotion dysregulation and sexual revictimization among young adult women (the population most at risk for sexual victimization; see Breslau et al., 1998; Pimlott-Kubiak & Cortina, 2003). Women aged 18–25 were recruited from the community for a study on “women’s life experiences and adjustment” (see Procedures for further details). Participants completed three assessments (separated by 4-month increments) over an 8-month period. To be included in the current study, participants had to complete all three assessments.

One hundred and fifty-one women were recruited from a metropolitan area in the Southern United States. Of these participants, 136 completed the Wave 2 assessment, 122 completed the Wave 3 assessment, and 118 completed all three assessments. There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics or baseline levels of BPD symptoms, emotion dysregulation, or physical health symptoms between participants who completed (vs. did not complete) all three assessments (ps > .10). The final sample of participants (N = 118) ranged in age from 18 to 25 years (M = 21.67, SD = 2.00) at Wave 1 and were ethnically diverse (75.4% African American; 22.9% White; 2.5% Latina). With regard to educational attainment, 96.6% of participants had received their high school diploma or GED, with many (79.7%) continuing on to complete at least some higher education. Approximately two-thirds of participants (69.5%) were full-time students, with an additional 7.6% enrolled part-time. Most participants (94.9%) were single.

Measures

Predictor variable

The BPD module of the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV; Zanarini, Frankenburg, Sickel, & Young, 1996) was administered at Wave 1 to obtain an interview-based assessment of BPD symptom severity (i.e., the number of BPD criteria with threshold ratings). Past research indicates that the DIPD-IV demonstrates good inter-rater and test-retest reliability for the assessment of BPD (Zanarini et al., 2000), with an inter-rater kappa coefficient of .68 and a test-retest kappa coefficient of .69. All interviews were conducted by bachelors- or masters-level clinical assessors trained to reliability with the first author (κ ≥ .80). Discrepancies (found in fewer than 10% of cases) were discussed as a group and a consensus was reached. Inter-item consistency of the BPD items in this sample was adequate (α = .79).

Mediator variable

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) is a 36-item self-report measure that assesses individuals’ current levels of emotion dysregulation across six domains: nonacceptance of negative emotions, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors when distressed, difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when distressed, lack of access to effective emotion regulation strategies, lack of emotional awareness, and lack of emotional clarity. The DERS demonstrates good test-retest reliability and construct and predictive validity and is significantly associated with objective measures of emotion regulation (Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Gratz, Rosenthal, Tull, Lejuez, & Gunderson, 2006; Gratz & Tull, 2010; Vasilev, Crowell, Beauchaine, Mead, & Gatzke-Kopp, 2009). Higher scores indicate greater emotion dysregulation. The DERS was administered at all thee Waves (αs ≥ .95).

Outcome variable

The Cohen-Hoberman Inventory of Physical Symptoms—Revised (CHIPS-R; Campbell, Greeson, Bybee, & Raja, 2008) was used to assess physical health symptoms. Participants were presented with a list of 35 commonly experienced physical symptoms (e.g., “headaches,” “dizziness,” “stomach pain”) and asked to indicate how much each physical health problem had bothered or distressed them during the past four months (including the current day) on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extreme bother). Items are summed to create an overall index of physical health symptoms. The CHIPS-R was administered at all three Waves (αs ≥ = .94).

Mood and anxiety symptoms

Given evidence of a relation between mood and anxiety symptoms and both BPD symptoms (Gratz et al., 2014; Snyder & Pitts, 1988; Tomko, Trull, Wood, & Sher, 2014) and physical health problems (Katon, 2003; Sala, Cox, & Sareen, 2008), the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) was used to assess the severity of depression and anxiety symptoms. The DASS-21 is a 21-item self-report questionnaire designed to differentiate between core symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. Participants rate the extent to which each item applies to them on a 4-point Likert-type scale (0 = never, 3 = almost always). The DASS-21 demonstrates adequate test-retest reliability and good construct and discriminant validity (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995; Roemer, 2001). To control for the influence of mood and anxiety symptoms on the relations of interest and ensure that any observed relation between BPD symptoms and physical health symptoms is not due solely to their shared associations with mood and anxiety symptoms, the current study used Wave 1 data for both the depression subscale (7 items; α = .87) and the anxiety subscale (7 items; α = .75).

Procedures

All procedures received prior approval by the Institutional Review Board of the participating institution. Recruitment methods included both random sampling from the community and community advertisements. First, women within the targeted age range (18–25) were identified from a large database of residential mailing addresses compiled by Survey Sampling International (SSI), a private research organization that provides sampling services to government and academic research entities. Information used to identify household members matching the designated gender and age criteria was obtained by SSI from a variety of secondary sources including school and voter registration lists. Randomly selected individuals from this list were sent a letter inviting them to participate in a longitudinal study of life experiences and adjustment. The recruitment letter contained a description of the project, a post-paid response card to be mailed back by interested individuals, and a $1 cash incentive. Women were also recruited through advertisements for a study on “women’s life experiences and adjustment” posted online and throughout the community (including coffee shops, churches, stores, hospitals, colleges, and clinics). All participants provided written informed consent.

At Waves 1 and 3, participants completed a series of self-report questionnaires and laboratory tasks. All questionnaires were administered online and completed on a computer in the laboratory. At Wave 1, participants additionally completed a diagnostic interview (including the DIPD-IV). The Wave 2 assessment included online self-report questionnaires only, and could be completed either at home or in the laboratory. Participants were compensated $75 for the Wave 1 assessment, $25 for the Wave 2 assessment, and $50 for the Wave 3 assessment.

Analytic Strategy

Associations between demographic variables (i.e., age, racial/ethnic background, and income) and the outcome variable (i.e., physical health symptoms at Wave 3) were examined using correlation analyses and analysis of variance. Any demographic variable found to be significantly associated with physical health symptoms at Wave 3 was included as a covariate in subsequent analyses. Correlation analyses were conducted to examine interrelations among the study variables, and a hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted to examine the unique association between BPD symptoms at Wave 1 and physical health symptoms at Wave 3 above and beyond baseline physical health symptoms, depression and anxiety symptoms, and emotion dysregulation (as well as relevant demographics).

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was then used to examine whether emotion dysregulation at Wave 2 mediates the relation between BPD symptom severity at Wave 1 and physical health symptoms at Wave 3, controlling for physical health symptoms, depression symptoms, and anxiety symptoms at Wave 1 (as well as relevant demographics). AMOS 20.0 (Arbuckle, 2010) was employed to analyze the path models, obtain maximum-likelihood estimates of model parameters, and provide goodness-of-fit indices (Peters & Enders, 2002). Standard measures including χ2, normed fit index (NFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and p of the close fit (PCLOSE) were used to assess model fit. A non-significant χ2, values of NFI, TLI, and CFI ≥ .90, lower RMSEA values (<.05), and higher PCLOSE values (>.05), are considered indicators of good model fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1992; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Lei & Wu, 2007).

Finally, consistent with current recommendations (Kline, 2011; Preacher & Hayes, 2004), bootstrapping procedures were utilized to estimate the significance of any indirect effects. Compared to the causal steps approach to testing mediation (e.g., Baron & Kenny, 1986), bootstrap methodology directly tests the indirect effect, is more statistically powerful, and does not rely on distributional assumptions (McCartney, Burchinal, & Bub, 2006). Bootstrapping was done with 5,000 random samples generated from the observed covariance matrix to estimate bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and significance values for the standardized indirect effects in the final model.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Based on the BPD module of the DIPD-IV, 14 participants (11.9%) met full diagnostic criteria for BPD and an additional 9 participants (7.6%) met criteria for subthreshold BPD (defined as meeting four criteria for BPD). Although physical health symptoms at Wave 3 were not significantly related to participant age (r = .07, p = .44) or income (r = −.09, p = .34), these symptoms did vary as a function of participant racial background, with White participants reporting significantly greater physical health symptoms than non-White participants (F [1, 117] = 6.01, p = .02). Thus, racial background (White vs. non-White) was included as a covariate in subsequent analyses. Descriptive data, as well as intercorrelations among the primary study variables, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive and Correlational Data for the Primary Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | -- | .02 | .19* | .01 | .02 | .01 | −.15 | −.05 | .13 | −.03 | .07 |

| 2. Racial Background | -- | -- | .08 | .14 | −.01 | .20* | .15 | .24** | −.06 | .04 | .22* |

| 3. Depression Symptoms at Wave 1 | -- | -- | -- | .52*** | .55*** | .52*** | .31** | .42*** | .45*** | .29** | .27** |

| 4. Anxiety Symptoms at Wave 1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | .52*** | .43*** | .26** | .31** | .52*** | .43*** | .47*** |

| 5. BPD Symptoms at Wave 1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | .40*** | .27** | .30** | .49*** | .40*** | .46*** |

| 6. Emotion Dysregulation at Wave 1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | .69*** | .69*** | .26** | .25** | .30** |

| 7. Emotion Dysregulation at Wave 2 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | .82*** | .12 | .32*** | .31** |

| 8. Emotion Dysregulation at Wave 3 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | .21* | .39*** | .43*** |

| 9. Physical Health Symptoms at Wave 1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | .69*** | .55*** |

| 10. Physical Health Symptoms at Wave 2 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | .67*** |

| 11. Physical Health Symptoms at Wave 3 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

|

| |||||||||||

| M | 21.67 | -- | 5.56 | 5.52 | 1.75 | 70.50 | 71.76 | 66.56 | 21.06 | 19.04 | 14.42 |

| SD | 2.00 | -- | 7.08 | 6.33 | 1.95 | 21.85 | 23.01 | 21.33 | 20.77 | 22.76 | 17.12 |

Note. BPD = Borderline personality disorder; Racial background: 1 = White, 0 = Non-White.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Primary Analyses

To examine the unique relation of baseline BPD symptoms to later physical health symptoms above and beyond other relevant baseline variables, a hierarchical multiple regression analysis predicting Wave 3 physical health symptoms was conducted with baseline physical health symptoms, depression and anxiety symptoms, emotion dysregulation, and racial background entered in the first step and BPD symptom severity entered in the second step (see Table 2). Results revealed a significant unique association between BPD symptom severity and Wave 3 physical health symptoms, with the inclusion of BPD symptom severity in the second step significantly improving the model (ΔR2 = .03, ΔF = 6.44, p < .05).

Table 2.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis Examining the Unique Relation of Baseline Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms to Physical Health Symptoms 8-Months Later

| β | b (SE) | t | R2(Adj) | R2Δ | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | .41 (.39) | .41*** | 15.68*** | |||

| Racial background | .21 | 8.64 (3.05) | 2.83** | |||

| Physical health symptoms at Wave 1 | .49 | .40 (.07) | 5.53*** | |||

| Depression symptoms at Wave 1 | −.13 | −.31 (.23) | −1.34 | |||

| Anxiety symptoms at Wave 1 | .21 | .56 (.26) | 2.17* | |||

| Emotion dysregulation at Wave 1 | .11 | .09 (.07) | 1.23 | |||

| Step 2 | .44 (.41) | .03* | 14.77*** | |||

| BPD symptoms at Wave 1 | .24 | 2.08 (.82) | 2.54* |

Note. BPD = borderline personality disorder; Racial background: 1 = White, 0 = Non-White.

p< .05.

p < .01.

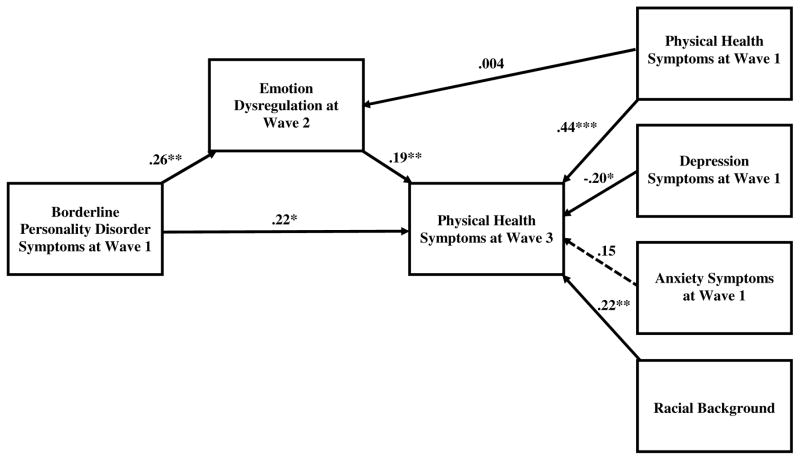

Next, SEM was used to examine whether emotion dysregulation at Wave 2 mediates the relation between BPD symptom severity at Wave 1 and physical health symptoms at Wave 3. The final model (see Figure 1) provided a good fit to the data, χ2 (6) = 11.34, p = .08, NFI = .95, TLI = .92, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .09, PCLOSE = .18. As presented in Figure 1, BPD symptom severity at Wave 1 was significantly positively associated with emotion dysregulation at Wave 2 (β = .26, p = .01) and physical health symptoms at Wave 3 (β = .22, p = .01). Furthermore, emotion dysregulation at Wave 2 was significantly positively related to physical health symptoms at Wave 3 (β = .19, p = .01). Moreover, findings revealed a significant indirect effect of BPD symptom severity at Wave 1 on physical health symptoms at Wave 3 through the pathway of emotion dysregulation at Wave 2 (β = .05, SE = .03, p = .02, 95% CI = 0.01–0.13), providing support for the mediating role of intermediary emotion dysregulation in the relation between BPD symptom severity and later physical health symptoms.1 Notably, when examining a similar model with emotion dysregulation at Wave 1 (vs. Wave 2) as the mediator of the association between BPD symptoms at Wave 1 and physical health symptoms at Wave 3, the indirect effect of BPD symptoms on later physical health symptoms through baseline emotion dysregulation was not significant (β = .03, SE = .04, p = .35, 95% CI = −0.04–0.12). Overall, these findings suggest that despite the relative stability of emotion dysregulation over time within this sample (see Table 1), there is something unique to intermediary emotion dysregulation (vs. baseline levels) that explains the relation of BPD symptoms to later physical health symptoms.

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Model Exploring the Mediating Role of Emotion Dysregulation in the Relation between Borderline Personality Disorder Symptom Severity and Physical Health Symptoms

Note. Weights are reported in the figure using standardized estimates. Dashed lines indicate nonsignificant paths. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. Model fit statistics: χ2 (6) = 11.34, p = .08, NFI = .95, TLI = .92, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .09, PCLOSE = .18.

Follow-up analyses examining the specific dimensions of emotion dysregulation that may mediate the relation of BPD symptoms to physical health symptoms revealed two significant emotion dysregulation dimensions: lack of access to effective emotion regulation strategies (indirect effect: β = .06, SE = .04, p = .02, 95% CI = 0.01–0.15) and lack of emotional clarity (indirect effect: β = .03, SE = .03, p = .04, 95% CI = 0.001–0.11). None of the other specific emotion dysregulation dimensions emerged as significant.

Discussion

Despite past research indicating heightened physical health problems in BPD (El-Gabalawy et al., 2010; Frankenburg & Zanarini, 2004), the mechanisms underlying this association remain unclear. The results of this study suggest that emotion dysregulation may be one such mechanism, accounting for the relation between BPD symptoms and physical health symptoms 8-months later in a large community sample of young adult women. Specifically, findings highlight the particular relevance of lack of access to effective emotion regulation strategies and lack of emotional clarity to this relation. These findings add to the growing body of research on the negative consequences of emotion dysregulation both in and outside the context of BPD (e.g., Axelrod, Perepletchikova, Holtzman, & Sinha, 2011; Crowell, Puzia, & Yaptangco, 2015; Gratz et al., 2010; Selby, Ward, & Joiner, 2010; Weiss, Sullivan, & Tull, 2015) and highlight physical health as an important outcome in need of further examination. Specifically, research is needed to examine the ways in which emotion dysregulation may contribute to the development of physical health symptoms among women with BPD pathology.

One such pathway may involve dysfunction of the stress response. Greater difficulties regulating emotion may increase sensitivity to and/or interfere with the successful navigation of stressful life events among individuals with BPD symptoms (Sapolsky, 2007), increasing their susceptibility to chronic stress. For example, studies have consistently shown that individuals with BPD exhibit hyperactivity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis (Wingenfeld, Spitzer, Rullkötter, & Löwe, 2010), indicating dysfunction of the stress response. Such hyperactivity results in frequent systemic elevations of glucocorticoids and catecholamines in the body, which, in turn, can promote a heightened proinflammatory response and contribute to immune system dysfunction (Cohen et al., 2012; Glaser & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005; Steptoe, Hamer, & Chida, 2007). Over time, this process puts elevated stress on the body and may increase susceptibility to the development of numerous disease states (Chrousos, 2000; Cohen et al., 2012; Glaser & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005). Consistent with this premise (as well as the results of the current study), past research has found that elevated levels of emotional distress increase risk for inflammation (Everson-Rose & Lewis, 2005; Miller, Chen, & Cole, 2009) and that maladaptive emotion regulation is associated with elevated levels of C-reactive protein (a biomarker of inflammation associated with the development of coronary heart disease; Appleton, Buka, Loucks, Gilman, & Kubzansky, 2013). Indeed, findings that lack of access to effective emotion regulation strategies and lack of emotional clarity were the only two dimensions of emotion dysregulation to account for the relation of BPD symptoms to later physical health symptoms are consistent with this model, as well as past research linking maladaptive emotion regulation strategies to increased sympathetic activation and physiological arousal (e.g., Gross, 1998). Specifically, given evidence that confusion regarding emotional states can exacerbate emotional distress (Wilkowski & Robinson, 2008), this heightened emotional distress combined with a lack of access to effective strategies for modulating that distress may contribute to chronic HPA axis activation and related inflammation, increasing the risk for chronic health problems.

Although the results of this study highlight one mechanism that may underlie the association between BPD symptoms and poor physical health outcomes, several limitations warrant consideration. First, although the use of a diverse community sample of women is a strength of this study, the extent to which these findings generalize to clinical samples of patients with BPD remains unclear. Most participants in this sample did not endorse clinically-significant levels of BPD symptoms, which may have influenced the strength of the observed relations, as well as the generalizability of our findings to patients with BPD. Given past findings of a relation of BPD to numerous physical health problems, examining these relations within a more severe sample of individuals with BPD diagnoses may have produced stronger results. Likewise, given the rather unique characteristics of our sample, the extent to which our findings are applicable to other relevant nonclinical or community samples is also unclear. For example, by focusing on only young adult women, the generalizability of our findings to older adults or men remains unknown. Although past findings that BPD is associated with significantly greater mental and physical disability in women (vs. men; Grant et al., 2008) support the exclusive focus on women within this study, the exclusion of older adults may have restricted the range of physical health symptoms present within this sample, reducing our statistical power and limiting the generalizability of our findings to individuals at risk for serious physical health problems. Future research examining this model among older adults, as well as individuals with physical health problems, is needed. Such research may help elucidate the role of BPD symptoms in physical health problems among individuals at greatest risk for poor physical health outcomes. Research examining these relations among both clinical and nonclinical samples of men is also needed, particularly in light of findings that gender may moderate the relations between both BPD (Johnson et al., 2003) and emotion dysregulation (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012) and related difficulties. Finally, it is important to note that the majority of participants in this sample identified as African-American. As such, the extent to which findings apply to young women of other racial/ethnic backgrounds warrants examination in future studies.

An additional limitation is the exclusive reliance on self-report measures of emotion dysregulation and physical health symptoms, responses to which may be influenced by an individual’s willingness and/or ability to report accurately on emotional responses. Future studies would benefit from the inclusion of objective indices of both emotion dysregulation (e.g., behavioral and/or physiological measures; Appelhans & Luecken, 2006; Gratz et al., 2006; Gratz, Tull, Matusiewicz, Breetz, & Lejuez, 2013) and physical health problems (e.g., blood pressure, blood glucose levels, CD4 T-lymphocyte count, Immunoglobulin E, and/or biological markers of inflammation, such as C-reactive protein or Interleukin-6). Likewise, this study used an overall score of physical health symptoms. Future research should investigate the role of emotion dysregulation in specific health problems among individuals with BPD pathology. For example, given findings of both HPA axis hyperactivity and high levels of psychological stress among individuals with BPD (e.g., Wingenfeld et al., 2010), BPD symptoms and related emotion dysregulation may have particular relevance for stress-related illnesses, such as hypertension, headache, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic fatigue.

Furthermore, although our use of a prospective design facilitates examination of the relation between baseline BPD symptoms and later emotion dysregulation and physical health symptoms, future research should examine these relations over more extended time periods, as well as explore the precise nature of their interrelations over time. In particular, to better elucidate the temporal relations among these variables, research is needed to examine these relations among individuals with less stable emotion dysregulation (e.g., patients receiving treatment targeting emotion regulation; samples with traumatic exposure between assessments). Doing so would facilitate examination of the specific patterns of change in each of the constructs of interest and the extent to which changes in emotion dysregulation over time predict subsequent changes in physical health symptoms.

Finally, although results provided evidence for an indirect relation of BPD symptoms to physical health symptoms through intermediary levels of emotion dysregulation, this relation was modest in size and did not fully explain the relation of baseline BPD symptoms to later physical health symptoms. Thus, future research is needed to examine other potential mechanisms that may underlie the relation between BPD symptoms and physical health problems, including poor health-related behaviors (e.g., lack of exercise, poor diet, prescription drug abuse), poor adherence to medication regimes, and risky behaviors (e.g., Frankenburg & Zanarini, 2004; Palmer, Salcedo, Miller, Winiarski, & Arno, 2003; Tull, Gratz, & Weiss, 2011). In particular, given findings of heightened rates of poor health-related behaviors/lifestyle choices among individuals with BPD (e.g., smoking, daily alcohol consumption, lack of exercise; Frankenburg & Zanarini, 2004), as well as evidence of a strong association between these behaviors and later physical health problems (Schoenborn, Adams, & Peregoy, 2013), the role of poor health-related behaviors in the relation between BPD symptoms and physical health symptoms deserves particular attention. Likewise, research is needed to examine the factors that may increase the risk for poor health-related and other risky behaviors among individuals with BPD. In particular, given the relevance of impulsivity to both BPD and health-risk behaviors (e.g., Black et al., 2009; Bornovalova, Gratz, Delany-Brumsey, Paulson, & Lejuez, 2006; Lynam, Miller, Miller, Bornovalova, & Lejuez, 2011), as well as emerging evidence suggesting a relation between impulsivity and physical health problems (Nederkoom, Braet, Van Eijs, Tanghe, & Jansen, 2006; Nes, Roach, & Segerstrom, 2009; Stupiansky, Hanna, Slaven, Weaver, & Fortenberry, 2013), research examining the mediating role of impulsivity in the relation between BPD symptoms and later physical health symptoms (both directly and indirectly through heightened health-risk behaviors) is needed.

Despite limitations, the results of this study add to the small but growing body of literature on the relevance of both BPD and emotion dysregulation to physical health problems. Given evidence that physical health problems can lead to a reduced quality of life and further increase the likelihood of psychiatric difficulties (e.g., depression; Dantzer, O’Connor, Freund, Johnson, & Kelley, 2008), co-occurring physical health symptoms may complicate psychological treatments for BPD and warrant systematic attention during the assessment and treatment of individuals with BPD pathology. Moreover, given evidence that emotion dysregulation underlies the relation between BPD symptoms and later physical health symptoms, research is needed to examine whether successful completion of empirically-supported treatments for BPD that focus on improving emotion regulation (e.g., mentalization-based treatment [Bateman & Fonagy, 2004], dialectical behavior therapy [Linehan, 1993], emotion regulation group therapy [Gratz & Gunderson, 2006]) also contributes to improved physical health within this population.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant R01 HD062226, awarded to the fourth author (DD). Work on this paper by the second author (NHW) was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant T32 DA019426.

Footnotes

When examining a similar model controlling for emotion dysregulation at Wave 1, the indirect effect of BPD symptoms on later physical health symptoms through Wave 2 emotion dysregulation was not significant (β = −.004, SE = .02, p = .72, 95% CI = −0.05–0.03). This finding was consistent with expectations, as levels of emotion dysregulation were highly stable in this sample across time (see Table 1).

References

- Abelson JL, Liberzon I, Young EA, Khan S. Cognitive modulation of the endocrine stress response to a pharmacological challenge in normal and panic disorder subjects. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:668–675. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelhans BM, Luecken LJ. Heart rate variability as an index of regulated emotional responding. Review of General Psychology. 2006;10:229–240. [Google Scholar]

- Appleton AA, Buka SL, Loucks EB, Gilman SE, Kubzansky LD. Divergent associations of adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies with inflammation. Health Psychology. 2013;32:748–756. doi: 10.1037/a0030068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod SR, Perepletchikova F, Holtzman K, Sinha R. Emotion regulation and substance use frequency in women with substance dependence and borderline personality disorder receiving dialectical behavior therapy. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37:37–42. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.535582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman AW, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment of BPD. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2004;18:36–51. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.1.36.32772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RA, Serowik KL, Rosen MI. Associations between impulsivity and high- risk sexual behaviors in dually diagnosed outpatients. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35:325–328. doi: 10.1080/00952990903075034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Gratz KL, Delany-Brumsey A, Paulson A, Lejuez CW. Temperamental and environmental risk factors for borderline personality disorder among inner-city substance users in residential treatment. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2006;20:218–231. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2006.20.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among adults with self-reported pain conditions in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. The Journal of Pain. 2008;9:1106–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: The 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research. 1992;21:230–258. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Greeson MR, Bybee D, Raja S. The co-occurrence of childhood sexual abuse, adult sexual assault, intimate partner violence, and sexual harassment: a mediational model of posttraumatic stress disorder and physical health outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:194–207. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos GP. Stress, chronic inflammation, and emotional and physical well-being: concurrent effects and chronic sequelae. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2000;106:S275–S291. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.110163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton A, Pilkonis PA, McCarty C. Social networks in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:434–441. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.4.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Doyle WJ, Miller GE, Frank E, Rabin BS, Turner RB. Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:5995–5999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118355109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298:1685–1687. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell SE, Puzia ME, Yaptangco M. The ontogeny of chronic distress: emotion dysregulation across the life span and its implications for psychological and physical health. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2015;3:91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: When the immune system subjugates the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2008;9:46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Gordon KL, Gratz KL, Breetz A, Tull MT. A laboratory-based examination of responses to social rejection in borderline personality disorder: The mediating role of emotion dysregulation. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2013;27:157–171. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2013.27.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Gordon KL, Whalen DJ, Layden BK, Chapman AL. A systematic review of personality disorders and health outcomes. Canadian Psychology. doi: 10.1037/cap0000024. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Gabalawy R, Katz L, Sareen J. Comorbidity and associated severity of borderline personality disorder and physical health conditions in a nationally representative sample. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2010;72:641–647. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181e10c7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson-Rose SA, Lewis TT. Psychosocial factors and cardiovascular diseases. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:469–500. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC. The association between borderline personality disorder and chronic medical illness, poor health-related lifestyle choices, and costly forms of health care utilization. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:1660–1665. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress-induced immune dysfunction: Implications for health. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2005;5:243–251. doi: 10.1038/nri1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, McRae K, Ramel W, Gross JJ. The neural basis of emotion regulation: Reappraisal and suppression of negative emotion. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63:577–586. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, Ruan WJ. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: Results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:533–545. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Breetz A, Tull MT. The moderating role of borderline personality in the relationships between deliberate self-harm and emotion-related factors. Personality and Mental Health. 2010;4:96–107. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Kiel EJ, Latzman RD, Elkin TD, Moore SA, Tull MT. Maternal borderline personality pathology and infant emotion regulation: Examining the influence of maternal emotion-related difficulties and infant attachment. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2014;28:52–69. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2014.28.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Rosenthal MZ, Tull MT, Lejuez CW, Gunderson JG. An experimental investigation of emotion dysregulation in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:850–855. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Tull MT. Assessing mindfulness and acceptance processes in clients: Illuminating the theory and practice of change. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2010. Emotion regulation as a mechanism of change in acceptance-and mindfulness-based treatments; pp. 107–133. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Tull MT, Matusiewicz AM, Breetz A, Lejuez CW. Multimodal examination of emotion regulation difficulties as a function of co-occurring avoidant personality disorder among women with borderline personality disorder. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2013;4:304–314. doi: 10.1037/per0000020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ. Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:224–237. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Levenson RW. Hiding feelings: The acute effects of inhibiting negative and positive emotion. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:95–103. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr NR, Hammen C, Brennan PA. Maternal borderline personality disorder symptoms and adolescent psychosocial functioning. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2008;22:451–465. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.5.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman C, Rice D, Sung HY. Persons with chronic conditions: their prevalence and costs. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;276:1473–1479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman PD, Fruzzetti AE, Buteau E, Neiditch ER, Penney D, Bruce ML, … Struening E. Family connections: a program for relatives of persons with borderline personality disorder. Family Process. 2005;44:217–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2005.00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Shea MT, Yen S, Battle CL, Zlotnick C, Sanislow CA, … Gunderson JG. Gender differences in borderline personality disorder: Findings from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2003;44:284–292. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:216–226. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keuroghlian AS, Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC. The relationship of chronic medical illness, poor health-related lifestyle choices, and health care utilization to recovery status in borderline patients over a decade of prospective follow-up. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2013;47:1499–1506. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, McGuire L, Robles TF, Glaser R. Psychoneuroimmunology: Psychological influences on immune function and health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:537–547. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.3.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Koenigsberg HW, Harvey PD, Mitropoulou V, New AS, Goodman M, Silverman J, … Siever LJ. Are the interpersonal and identity disturbances in the borderline personality disorder criteria linked to the traits of affective instability and impulsivity? Journal of Personality Disorders. 2001;15:358–370. doi: 10.1521/pedi.15.4.358.19181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigsberg HW, Siever LJ, Lee H, Pizzarello S, New AS, Goodman M, … Prohovnik I. Neural correlates of emotion processing in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2009;172:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei P, Wu Q. Introduction to structural equation modeling: Issues and practical considerations. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 2007;26:33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. 2. Australia: Psychology Foundation of Australia; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Miller JD, Miller DJ, Bornovalova MA, Lejuez CW. Testing the relations between impulsivity-related traits, suicidality, and nonsuicidal self-injury: A test of the incremental validity of the UPPS model. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2011;2:151–160. doi: 10.1037/a0019978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney K, Burchinal MR, Bub KL. Best practices in quantitative methods for developmentalists. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2006:71. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2006.07103001.x. (Serial No. 285) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;338:171–179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams LA, Higgins KS. Associations between pain conditions and borderline personality disorder symptoms. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2013;29:527–532. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31826ab5d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Chen E, Cole SW. Health psychology: Developing biologically plausible models linking the social world and physical health. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:501–524. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran P, Stewart R, Brugha T, Beddington P, Bhugra D, Jenkins R, Coid JW. Personality disorder and cardiovascular disease: Results from a national household survey. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007;68:69–74. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nederkoorn C, Braet C, Van Eijs Y, Tanghe A, Jansen A. Why obese children cannot resist food: The role of impulsivity. Eating Behaviors. 2006;7:315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nes LS, Roach AR, Segerstrom SC. Executive functions, self-regulation, and chronic pain: A review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;37:173–183. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2012;8:161–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer NB, Salcedo J, Miller AL, Winiarski M, Arno P. Psychiatric and social barriers to HIV medication adherence in a triply diagnosed methadone population. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2003;17:635–644. doi: 10.1089/108729103771928690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimlott-Kubiak S, Cortina LM. Gender, victimization, and outcomes: reconceptualizing risk. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:528–539. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L. Measures for anxiety and related constructs. In: Antony MM, Orsillo SM, Roemer L, editors. Practitioner’s guide to empirically based measures of anxiety. New York: Guilford Publications; 2001. pp. 49–83. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal MZ, Gratz KL, Kosson DS, Cheavens JS, Lejuez CW, Lynch TR. Borderline personality disorder and emotional responding: A review of the research literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:75–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala T, Cox BJ, Sareen J. Anxiety disorders and physical illness comorbidity: An overview. In: Zvolensky MJ, Smits J, editors. Anxiety in health behaviors and physical illness. Springer; New York: 2008. pp. 131–154. [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P, Rothman AJ, Detweiler JB, Steward WT. Emotional states and physical health. American Psychologist. 2000;55:110–121. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM. Stress, stress-related disease, and emotional regulation. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 606–615. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn CA, Adams PF, Peregoy JA. Health behaviors of adults: United States, 2008–2010. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Statistics. 2013;10:1–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Ward AC, Joiner TE. Dysregulated eating behaviors in borderline personality disorder: Are rejection sensitivity and emotion dysregulation linking mechanisms? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010;43:667–670. doi: 10.1002/eat.20761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, Dyck IR, Stout RL, Bender DS, … Oldham JM. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:276–283. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Pfohl B, Widiger TA, Livesley WJ, Siever LJ. The borderline diagnosis I: Psychopathology, comorbidity, and personality structure. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:936–950. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder S, Pitts WM. Characterizing anxiety in the DSM-III borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1988;2:93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Hamer M, Chida Y. The effects of acute psychological stress on circulating inflammatory factors in humans: a review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2007;21:901–912. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupiansky NW, Hanna KM, Slaven JE, Weaver MT, Fortenberry JD. Impulse control, diabetes-specific self-efficacy, and diabetes management among emerging adults with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2013;38:247–254. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomko RL, Trull TJ, Wood PK, Sher KJ. Characteristics of borderline personality disorder in a community sample: Comorbidity, treatment utilization, and general functioning. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2014;28:734–750. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2012_26_093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Gratz KL, Weiss NH. Exploring associations between borderline personality disorder, crack/cocaine dependence, gender, and risky sexual behavior among substance-dependent inpatients. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2011;2:209–219. doi: 10.1037/a0021878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilev CA, Crowell SE, Beauchaine TP, Mead HK, Gatzke-Kopp LM. Correspondence between physiological and self-report measures of emotion dysregulation: A longitudinal investigation of youth with and without psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2009;50:1357–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Sullivan TP, Tull MT. Explicating the role of emotion dysregulation in risky behaviors: A review and synthesis of the literature with directions for future research and clinical practice. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2015;3:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingenfeld K, Spitzer C, Rullkötter N, Löwe B. Borderline personality disorder: hypothalamus pituitary adrenal axis and findings from neuroimaging studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:154–170. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Work Group on Borderline Personality Disorder. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yach D, Hawkes C, Gould CL, Hofman KJ. The global burden of chronic diseases: Overcoming impediments to prevention and control. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:2616–2622. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Sickel AE, Young L. The diagnostic interview for DSM-IV personality disorders (DIPD-IV) Belmont, MA: McLean Hospital; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, Dolan R, Sanislow C, Schaefer E, … Gunderson JG. The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: Reliability of axis I and II diagnoses. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2000;14:291–299. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]