ABSTRACT

Although one of the most important missions of end-of-life education is to ensure proper inter-professional education (IPE), in Japan, end-of-life care IPE has not been given enough attention especially in community settings. This study aims at developing an effective workshop facilitator training program on end-of-life care IPE and acquiring the know-how to set up and efficiently run administrative offices. We first developed a tentative facilitation training program and conducted it in five cities nationwide. The training strategy was as follows: (1) participating in the workshop, (2) attending a lecture on facilitation, (3) conducting a preparatory study, (4) attending one workshop session as a facilitator, and (5) reflecting on one’s attitude as a facilitator based on workshop participants’ questionnaire, peer-feedback, and video recording. A total of 10 trainees completed the training program. We assessed the level of improvement in the trainees’ facilitation skills and the efficacy of the training course using a qualitative approach. This formative study helped us identify several aspects needing improvement, especially in the areas of information technology and social media. Progress in these areas may have a positive impact on the education of community health care professionals whose study hours are limited, helping provide continued facilitation training.

Key Words: Workshop, Inter-professional education, Older people, Facilitation

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the number of elderly deaths has increased very rapidly in Japan, and there has consequently been an increased national awareness about the importance of quality end-of-life care for the elderly.1-4) In 2001, the Japan Geriatric Society issued a position statement on end-of-life care for the elderly: a revised version of the report was published in 2012.3) In this statement, the organization emphasized the key role of education in palliative care for the elderly, noting that “the majority of health care professionals receive insufficient specialized training in the care of terminally-ill patients.” The statement further proposed that “concrete and practical instruction in the care of dying patients, including the management of symptoms and communication skills, be provided.”

Similarly, other countries with high proportions of older people have also come to acknowledge deficiencies in both undergraduate and postgraduate end-of-life care education programs for health care professionals.5-10) Although literature suggests that this issue has been investigated, it is clear that, until recently, end-of-life care education has not been given sufficient attention, especially in community settings. Therefore, after reviewing related literature,11-13) the authors developed a community-based educational program on end-of-life care for the elderly.14) This program was primarily designed for professional caregivers, with an emphasis on basic attitudes toward end-of-life care practices. The workshop was tested nationwide with two hundred and forty-seven participants. Our six-month follow-up data confirms improvements in the participants’ attitudes toward end-of-life care provision.

In addition, high quality end-of-life care requires seamless inter-professional teamwork. One of the most important missions of end-of-life education is therefore to ensure proper inter-professional education (IPE).5) The workshop program, which was originally only geared toward non-medical care professionals, was subsequently adjusted to also target IPE.15)

Two major barriers hamper the promotion of this type of program nationwide. First, the development and implementation of IPE programs tends to rely largely on a number of well-trained facilitators who have gained expertise through ‘hands-on’ involvement in facilitating IPE.16) Although several studies address this issue,17-19) there is still a lack of empirical evidence regarding type of approaches are effective to prepare for this type of work. Second, the successful implementation of the program requires the establishment of efficient administrative offices in charge of operation management. The aims of this formative research are to develop a comprehensive training program for workshop facilitators and develop the know-how to set up and run administrative offices efficiently.

METHODS

Central executive committee

We created a central executive committee for our IPE program at Nagoya University in April 2014. We recruited 6 committee members: a nurse, 3 care managers, and 2 directors of home care support offices.

Inter-professional education program

The educational program, whose details were explained elsewhere,14) was originally developed as a 7-hour workshop-style course focusing on important end-of-life care themes such as: definition of end-of-life of the elderly, signs and symptoms of imminent death, advanced care planning, issues related to tube feeding, communication with bed-ridden elderly, communication with family members of end-of-life elderly patients, staff education concerning key elements in the provision of end-of-life care.

During the session “definition of end of life of the elderly”, the participants discussed and defined the onset of the end-of-life stage for the elderly. During the session “signs and symptoms of imminent death”, the participants discussed and listed the frequently observed signs and symptoms of imminent death among end-of-life elderly. During the session “advance care planning”, the participants discussed a hypothetical case where a caring staff provides emergency cardiopulmonary resuscitation to a resident with a do-not-resuscitate order. During the session “issues related to tube feeding”, the participants took part in a debate on the pros and cons of tube feeding for end-of-life care elderly residents. During the session “communication with family members of end-of-life elderly patients”, we used role-play to get the participants to share their experiences on dealing with families of end-of-life residents. During the session “communication with bed-ridden elderly”, the participants watched a 2-minute trigger video script where a bed-ridden elderly was being treated roughly, and discussed proper attitudes toward elderly residents. During the session “staff education concerning key elements in the provision of end-of-life care for elderly residents”, the participants discussed the items they felt should be prioritized in the provision of end-of-life care for elderly residents and designed a micro teaching program for inexperienced caring staff based on the discussion results.

Facilitation training course planning and management

We launched the FTC nationwide and concurrently opened program coordinating offices in five regions: Tohoku (Akita City), Kanto (Yokohama City), Tokai (Nagoya City), Kansai (Himeji City), and Shikoku (Tokushima City). Each office was asked to recruit a number of FTC participants in each district. The eligibility requirements included being involved in community-based integrated care and IPE. A total of 10 female trainees completed the FTC (Table 1).

Table 1.

Committee’s assessment for the improvement of facilitation skills

| No. | Age | Occupation | City | Improvements | Points for improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Early 50s | Nurse | Akita | She seems to have acquired a wider perspective | She should make use of pauses to improve the effectiveness of her speech |

| She now looks more confident | Her speech is still lacking in emotion | ||||

| Her speech has become smoother | She uses set phrases such as “Let me see…” too frequently | ||||

| She should adopt a pace that is more in sync with the participants | |||||

| 2 | Late 30s | Care manager |

Akita | The speed of her speech has improved | No other comments |

| She is now able to pay attention to the audience | |||||

| She is now able to keep a good pace with the audience | |||||

| 3 | Early 50s | Care manager |

Yokohama | She is now able tos whilepeak while looking at the entire audience | She still looks a littletoo serious |

| She is now able to use body language effectively to get her point across | |||||

| 4 | Late 30s | Care manager |

Yokohama | Her speech has become smoother | Her explanations lacked clarity |

| Her voice has become clearer | She should look at the participants rather than the slide | ||||

| She should focus less on reading and more on explaining | |||||

| 5 | Late 30s | Care manager |

Yokohama | She is now able to explain with feeling | She should explain the various concepts she wants to convey in her own words |

| Her speed is now slower and her speech clearer | |||||

| She is now able to pause effectively during speech | |||||

| She is now able to elicit questions during her sessions | |||||

| The second time, she did not pressure the audience to agree with her opinions | |||||

| 6 | Early 30s | Care manager |

Himeji | She now appears less nervous | She should make eye contact with the participants rather than look at her memo |

| She is now able to use words of her own to explain her thoughts | |||||

| She is now able to use pauses effectively during her speech | |||||

| She has improved her vocal tone | |||||

| She now looks confident | |||||

| 7 | Late 40s | Care manager |

Nagoya | She seems to have acquired a wider perspective | No other comments |

| She is now able to avoid unnecessary words during her speech | |||||

| 8 | Early 40s | Social worker |

Nagoya | She is now able to entertain the audience | No other comments |

| 9 | Early 40s | Public health nurse |

Tokushima | She now looks at the audience and appears a little more confident | She still needs to work on projecting a more confident image |

| The speed of her speech is now appropriate | She is unable to establish a good rapport with the audience because she is still too serious | ||||

| 10 | Early 40s | Care manager |

Tokushima | She is now able to use pauses to her advantage during speech | She should be mindful of meaningless gestures |

| The speed of her speech has improved | |||||

| She is now able to illicit questions from the audience |

The committee organized a facilitation training course (FTC) for an IPE workshop program on end-of-life care for the elderly. The training strategy was as follows: (1) participating in the IPE workshop, (2) attending a lecture on facilitation, (3) conducting preparatory study, (4) attending one workshop session as a facilitator (25 to 50 minutes), and (5) reflecting on one’s attitude as a facilitator based on the workshop participants’ questionnaire, peer-feedback, and video recording. From January 2014 to December 2015, the first author (YH) and two members of the central executive committee conducted an IPE workshop in each region, in which recruited FTC trainees took part. The trainees then attended a 20-minute lecture on facilitation given by YH and conducted preparatory study (involving textbook reading and presentation practice) to acquire the skills to facilitate a session during the subsequent IPE workshop. The central executive committee invited all the trainees to a 2-hour IPE workshop with 12 to 14 participants at Nagoya University to provide them with an opportunity to facilitate. After the workshop, they received feedback from workshop participants and peers, and viewed video recordings of their own facilitation session from the central executive committee. Prior to the feedback session, the central executive committee discussed and created a checklist of facilitation skills for participants and peers to provide constructive feedback to trainees: e.g., creating a welcoming, comfortable atmosphere, promoting effective group communication, intervening when needed, and managing time and workflow. Each trainee was informed about the audio-recording process and gave permission for his or her data to be used.

Facilitation skills assessment

Three to six months later, each program office held a 2-hour follow-up workshop to assess the level of improvement in the trainees’ facilitation skills. The committee members evaluated the effects of the facilitation training program by comparing previous and subsequent video recordings. Using the facilitation skills checklist as a springboard, the committee members discussed their personal views and continued to exchange observations with their peers until a consensus was reached.

Formative assessment for the training course and IPE program

In March 2016, the central executive committee members held focus-group discussions among themselves to review the shortcomings of both the FTC and the overall IPE workshop program promotion process. The discussions aimed at developing a strategic action plan to promote the workshop program. The focus group question session was open-ended and moved from the general to the specific; the debate continued until all members felt that the data had been dealt with exhaustively. Discussion time was 40 minutes for FTC and 70 minutes for the promotion of the IPE program. The discussion was audio-recorded and all statements made during the exchange were chronicled in the field notes. Following discussions, YH transcribed the entire recording and converted the members’ statements into single-sentence labels. In order to properly identify the issues, the members were encouraged to specify the problems with the program during the course of the discussion.

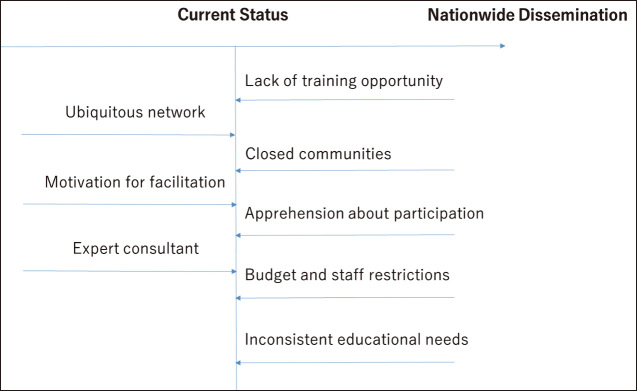

For the areas needing improvement in FTC, we categorized the qualitative data of the members’ statements inductively. Regarding the IPE program promotion, we used the KJ method to identify and visualize the issues to solve.20) First, YH and a research assistant selected the most representative labels out of all listed labels, organized them into groups and combined those that shared strong similarity in terms of quality as a result of grouping (Fig 1). Second, we formulated a representative sentence and key phrase for each group, making sure to retain the core meaning of the group labels. Finally, we arranged these groups according to their interrelationships.

Fig. 1.

Summary figure of strategies for the nationwide promotion of the end-of-life care workshop program

Ethics clearance

This study was approved by the Bioethics Review Committee of Nagoya University School of Medicine (approval number 2014-0321). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

RESULTS

Effects on facilitation skills

The committee’s assessment on the improvement of facilitation skills is shown in Table 1. Some trainees acquired more confidence in facilitation over time; others still had difficulty speaking smoothly in front of an audience. A few trainees continued to deliver their speech in a monotonous tone even after the course. However, few comments were made regarding the improvement of basic facilitation skills.

Assessment of FTC content

After processing the qualitative data related to FTC content, we extracted the following 8 main themes for the improvement of our training course: 1) lack of education theory; 2) lack of goal-setting by participants; 3) lack of basic facilitation skills education; 4) lengthy program; 5) lack of repetition practice; 6) difficulty recruiting an audience to provide feedback; 7) lack of follow-up support to help participants host the workshop in their hometown; and 8) difficulty adapting the course to suit trainees’ levels and needs. The improvement suggestions for the training course are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Committee's suggestions for the improvement of the training course

| Category | Label |

|---|---|

| Educational theory | We would like to teach specific educational principles |

| We need an educational consultant | |

| Goal setting on individual facilitation performance |

We would like to explain the role of facilitators |

| We have to clarify the goals of this training course | |

| Trainees should set their own goals for facilitation activities | |

| We would like trainees to understand that they can use facilitation skills in their own workplace | |

| Basic facilitation skills | We would like trainees to understand that time keeping is an important facilitation skill |

| We need to include the acquisition of basic facilitation skills to the goals | |

| Course length | We would like to shorten the course |

| Repetition practice | The course needs to include a repetition of the facilitation practice |

| Recruitment | It is difficult to recruit workshop participants |

| It is not easy to recruit skilled facilitators | |

| Follow-up support | We need to set up a facilitator authorization system |

| We would like trainees to host the workshop in their own cities | |

| We think that this training program should be held on an ongoing basis | |

| Follow-up support is needed to help trainees open workshops in their own cities | |

| We would like to watch follow-up video recordings of the trainees' facilitation in their own cities | |

| Tailor-made programs | Some trainees require mental skills training |

| We need to adjust the training course according to the target seminar/workshop scale | |

| Some trainees need to improve their slide-making skills | |

| Some trainees seem to read the scenarios without any expression | |

| We would like to coach the trainees to adjust their progress schedule | |

| Some trainees are not familiar with the Power Point application | |

| Some trainees need to improve their computer operation skills |

Strategies for the nationwide promotion of the end-of-life care workshop program

After processing the qualitative data of the discussions, we described a number of areas needing improvement in “Strategies for overcoming the barriers to the promotion of our high-quality workshop program”. Given that independent labels are treated as individual groups in the KJ method, we identified the following 8 themes: 1) budget and staff restrictions hindering business expansion; 2) conveying that facilitation is a challenging but worthwhile task; 3) building a nationwide network of various types of organizations and public; 4) apprehension from numerous communities about introducing IPE; 5) letting learners know that they will benefit from the workshop; 6) changing educational needs; 7) restricted settings for practical facilitation training; and 8) involvement of experts as supervisors. The next organizational step in the KJ method involved creating a chart: we arranged all the themes (including independent labels) onto a large sheet of paper, paying close attention to the inter-relationships between each theme (Fig 1).

Budget and staff restrictions

Holding workshops in and around Nagoya City is practical and economical because we can make use of the education resources of Nagoya University. Organizing workshops elsewhere in the country, however, entails various types of expenses for clerical work, advertisement, transportation and accommodation.

- My schedule does not allow me the flexibility to travel all over Japan to host workshops (Participant 4)

- The more facilitators and administrative staff we have, the more complex workshop coordination becomes (Participant 9)

Challenging but rewarding task

Most candidate facilitators are community health care professionals who work at the site. Professional engagements often make it difficult for them to stay motivated to continue managing workshops in the community overtime.

- Workshop planning is a difficult but interesting and rewarding task (Participant 3)

- Balancing the demands of work and facilitation activities is not easy (Participant 5)

Need for ubiquitous network

Social media networks have made it easier to build and maintain connections in recent years. In fact, we have used social media tools to organize meetings and advertise our workshops:

- We would like to train leaders of facilitators in all key areas (Participant 4)

- We would like to collaborate with other community education groups (Participant 6)

- Facebook is still not very popular among health care professionals (Participant 9)

Closed communities

IPE is just starting to attract attention in Japan. Some communities prefer to follow more traditional educational programs consisting mainly of lectures, and do not wish to adopt more active learning methods such as workshop-style sessions. Also, in certain communities workshops are biased in terms of number of professionals attending; in some cases too few physicians or too many care managers end up attending due to lack of advertisement:

- Community support service centers distribute seminar information to home care support offices but not to institutions and establishments for home care services (Participant 4)

- Some community leaders are too guarded to launch new study meetings (Participant 6)

Apprehension about participation

A number of obstacles affected workshop attendance. Some community care workers were unable to convince their superiors about the benefits of attending our workshop. Also, some people felt intimidated about participating in a workshop sponsored by a prestigious institution (Nagoya University). In addition, due to lack of advertisement, many facilities and care workers were unaware of when and where our workshops were held. Also, central executive committee members generally view our workshop as an opportunity for serious study but not for social interaction and exchange.

- Nagoya University is a prestigious institution (Participant 3)

- Lack of understanding from superiors is a barrier to attending or holding workshops (Participant 6)

Inconsistent educational needs

Participant 9 mentioned the problem of changing educational trends. For instance, dementia and end-of-life care may be popular topics for a while, but then transferring is in the spotlight at another time.

Lack of training opportunity

Participant 3 thought that there were few opportunities to take on the role of workshop facilitator in real settings. Inspired by the training program, she plans to take up the challenge of coordinating workshop programs to promote facilitation skills in the communities.

Expert consultant

Participant 4 emphasized the importance of inviting experts to attend the workshop as supervisors. Without the assistance of experts, facilitators find it difficult to answer participants’ questions or provide valuable feedback during the workshop. However, securing the attendance of expert supervisors to our workshop is still a challenging task due limited of funds and availability of trained professionals.

DISCUSSIONS

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first trial study in the world to focus on the strategies for the widespread adoption of a multidisciplinary and community-based end-of-life care IPE program, whose educational effects have previously been tested nationwide.14) As a strategy to promote evidence-based end-of-life care IPE program, we provided a pilot practical training session for facilitators. This formative study brought to light a number of effective strategies to promote evidence-based end-of-life care education nationwide.

The FTC helped a number of trainees improve their voice and speaking skills. Some trainees seem to have been able to improve the speed of their speech, while others appear to have been able to get over their nervousness and develop confidence while speaking. Our central executive committee members rated highly the quality of both IPE and FTC programs, and expressed a strong wish to promote them.

In addition, we highlighted the fact that FTC could be a very cost-effective program. The program does not require the expertise of skilled facilitators to teach and assess trainees, but rather focuses on self-study and self-reflection. Moreover, the program can provide learning opportunities to both trainee facilitators and workshop participants simultaneously.

New strategies for the promotion of our workshop program were also suggested: e.g., collaborating with other organizations to convey that facilitation is a worthwhile, interesting task. In addition, recent technological advances in medical education settings have made it possible for users to enjoy online courses.21, 22) Similarly, our committee members highlighted the necessity for a nationwide online connection through social media in order to promote FTC and IPE programs. One possible measure to reinforce follow-up training is to use distance learning or E-learning systems.

However, a number of areas in our FTC program still need to be improved. First, even though FTC covers a wide range of facilitating skills such as the display of enthusiasm, humor, and empathy as well as complex interchange with learners, the program only enabled a few trainees to improve basic speech skills. According to the committee’s observation data, trainees who failed to progress in this area seemed to stick to set scenarios and lacked the flexibility to adapt to the various situations. The format of our textbook, which includes examples of speeches and PowerPoint slides for all chapters, may have contributed to this problem. The textbook probably should have included explanatory guides rather than speech drafts,11) and offered the option to revise the presentation slides and speech drafts on the users’ computer.

Second, the eligibility requirements may not have been optimal and should be reconsidered. Although trainees were involved in community-based IPE, most of them acted as novice facilitators. The work of Egan-Lee E et al.16) shows that many novice facilitators, despite participating in an intensive strategy designed to support them in their IPE facilitation work, still feel unprepared and continue to have a poor conceptual understanding of core IPE and inter-professional collaboration principles.

Third, our course should have provided more time for reflection and feedback. A possible explanation for our failure to reach the expected educational effects is that, as novice facilitators, our trainees may have needed extensive role-play sessions as preliminary skill practice before performing in front of an audience. Bylund et al. previously showed that a 3–4-hour comprehensive communication skills training workshop prepared 32 novice facilitators to competently facilitate.23) In this study, the trainees were paired with an experienced co-facilitator who guided the training process and provided feedback to the trainees during role-play sessions. Also, our program should have provided trainees more feedback on basic facilitation skills by questioning participants. Although a basic facilitation checklist was included in the workshop participants’ questionnaire, it was not sufficient to generate improvements in this area. The questionnaire also included a comment section for participants to provide feedback to trainees, but very few shared their opinion; this is partly due to lack of time but also to a lack of motivation because many of the workshop participants were more interested in learning about end-of-life care than facilitation.

CONCLUSION

We developed and conducted a nationwide facilitation training course to promote our multidisciplinary community-based educational program on end-of-life care. This formative study helped us pinpoint several issues to tackle, especially in the area of information technology and the use of social media. Advances in these fields may be of benefit in the education of community health care professionals whose study hours are limited, helping provide continued facilitation training.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are grateful to all the participants for giving their time and energy to this study. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 26460595.

REFERENCES

- 1).Hirakawa Y. Palliative Care for the Elderly: A Japanese perspective. In: Contemporary and Innovative Practice in Palliative Care, edited by Chang E, Johnson A. pp. 271–290, 2012, In Tech, Rijeka.

- 2).Watanabe M, Yamamoto-Mitani N, Nishigaki M, Okamoto Y, Igarashi A, Suzuki M. Care managers’ confidence in managing home-based end-of-life care: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr, 2013; 13: 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3).Uemura K, Iijima S, Japan Geriatrics Society Ethical Committee. Position of the Japan Geriatrics Society on terminal care medical treatment for the elderly 2012. Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi, 2012; 49: 387–392. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4).Oshitani Y, Nagai H, Matsui H. Rationale for physicians to propose do-not-resuscitate orders in elderly community-acquired pneumonia cases. Geriatr Gerontol Int, 2014; 14: 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5).Kaasalainen S, Willison K, Wickson-Griffiths A, Taniguchi A. The evaluation of a national interprofessional palliative care workshop. J Interprof Care, 2015; 29: 494–496. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6).Allen SL, Davis KS, Rousseau PC, Iverson PJ, Mauldin PD, Moran WP. Advanced care directives: overcoming the obstacles. J Grad Med Educ, 2015; 7: 91–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7).Ellman MS, Fortin AH 6th, Putnam A, Bia M. Implementing and evaluating a four-year integrated end-of-life care curriculum for medical students. Teach Learn Med, 2016; 28: 229–239. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8).Flood JL, Commendador KA. Undergraduate nursing students and cross-cultural care: A program evaluation. Nurse Educ Today, 2016; 36: 190–194. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9).Parks SM, Haines C, Foreman D, McKinstry E, Maxwell TL. Evaluation of an educational program for long-term care nursing assistants. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2005; 6: 61–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10).von Gunten, CF., Mullan, P., Nelesen, RA., Soskins, M., Savoia, M., Buckholz, G., et al. Development and evaluation of a palliative medicine curriculum for third-year medical students. J Palliat Med, 2012; 15: 1198–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11).Henderson ML, Hanson L, Reynolds K. Improving nursing home care of the dying: a training manual for nursing home staff. pp. 1–88, 2000, Springer Publishing Company, New York.

- 12).Hirakawa Y, Masuda Y, Kuzuya M, Iguchi A, Uemura K. Non-medical palliative care and education to improve end-of-life care at geriatric health services facilities: a nationwide questionnaire survey of chief nurses. Geriatr Gerontol Int, 2007; 7: 266–270.

- 13).Hirakawa Y, Kuzuya M, Uemura K. Opinion survey of nursing or caring staff at long-term care facilities about end-of-life care provision and staff education. Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 2009; 49: 43–48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14).Hirakawa Y, Kimata T, Uemura K. Short- and long-term effects of workshop-style educational program on long-term care leaders’ attitudes toward facility end-of-life care. J Community Med Health Educ, 2013; 3: 234.

- 15).Hirakawa Y, Abe Y. Effects of inter-professional end-of-life care workshop: A questionnaire survey. Kanwa Kea, 2014 (in Japanese); 24: 40–42.

- 16).Egan-Lee E, Baker L, Tobin S, Hollenberg E, Dematteo D, Reeves S. Neophyte facilitator experiences of interprofessional education: implications for faculty development. J Interprof Care, 2011; 25: 333–338. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17).Ruiz MG, Ezer H, Purden M. Exploring the nature of facilitating interprofessional learning: findings from an exploratory study. J Interprof Care, 2013; 27: 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18).Lindqvist SM, Reeves S. Facilitators’ perceptions of delivering interprofessional education: a qualitative study. Med Teach, 2007; 29: 403–405. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19).Freeman S, Wright A, Lindqvist S. Facilitator training for educators involved in interprofessional learning. J Interprof Care, 2010; 24: 375–385. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20).Raymond S. The KJ Method: A technique for analyzing data derived from Japanese ethnology. Hum organ, 1997; 56: 233–237.

- 21).Nevin CR, Westfall AO, Rodriguez JM, Dempsey DM, Cherrington A, Roy B, et al. Gamification as a tool for enhancing graduate medical education. Postgrad Med J, 2014; 90: 685–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22).Prunuske AJ, Henn L, Brearley AM, Prunuske J. A randomized crossover design to assess learning impact and student preference for active and passive online learning modules. Med Sci Educ, 2016; 26: 135–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23).Bylund CL, Brown RF, di Ciccone BL, Diamond G., Eddington J, Kissane DW. Assessing facilitator competence in a comprehensive communication skills training programme. Med Educ, 2009; 43: 342–349. [DOI] [PubMed]