Abstract

Streptococcus suis (S. suis) form biofilms and causes severe diseases in humans and pigs. Biofilms are communities of microbes embedded in a matrix of extracellular polymeric substances. Eradicating biofilms with the use of antibiotics or biocides is often ineffective and needs replacement with other potential agents. Compared to conventional agents, promising and potential alternatives are biofilm-inhibiting compounds without impairing growth. Here, we screened a S. suis adhesion inhibitor, rutin, derived from Syringa. Rutin, a kind of flavonoids, shows efficient biofilm inhibition of S. suis without impairing its growth. Capsular polysaccharides(CPS) are reported to be involved in its adherence to influence bacterial biofilm formation. We investigated the effect of rutin on S. suis CPS content and structure. The results showed that rutin was beneficial to improve the CPS content of S. suis without changing its structure. We further provided evidence that rutin specifically affected S. suis biofilm susceptibility by affecting CPS biosynthesis in vitro. The study explores the antibiofilm potential of rutin against S. suis which can be used as an adhesion inhibitor for the prevention of S. suis biofilm-related infections. Nevertheless, rutin could be used as a novel natural inhibitor of biolfilm and its molecular mechanism provide basis for its pharmacological and clinical applications.

Keywords: Streptococcus suis, biofilms, rutin, adhesion, CPS

Introduction

Streptococcus suis (S. suis) is a major swine pathogen and a zoonotic agent that causes severe invasive diseases in pigs, including meningitis and streptococcal toxic shock-like syndrome (Gottschalk et al., 2010). What’s more, S. suis is a major public health issue and an emerging zoonotic agent in Southeast and East Asia (Sriskandan and Slater, 2006; Gottschalk et al., 2007). In 2005, a survey showed more than two hundred human cases of S. suis in China among them 39 were found dead (Yang et al., 2006). Meanwhile, studies showed that S. suis could cause persistent infections due to its ability of forming biofilms in vivo (Wang Y. et al., 2011).

Biofilms are microbial sessile communities characterized by bacterium that are adhered to biotic or abiotic surfaces or to each other, are surrounded by a polymer matrix and exhibit an altered phenotype compared to planktonic cells (Fux et al., 2005). Biofilm cells are known to be 10–1,000 times more opposed to antimicrobial agents compared to planktonic cells (Gilbert et al., 1997). This may be due to a decreased penetration of antibiotics, a decreased growth rate of the biofilm cells and/or a decreased metabolism of bacterial cells in biofilms (Kiedrowski and Horswill, 2011). In addition, the presence of persisted cells and the expression of specific resistance genes in biofilms may contribute to this tolerance (Conlon, 2014).

Bacterial adhesion to a substrate is the first essential step for biofilm formation. Meanwhile, it has been reported that CPS was involved in the adherence of pneumococci to host cells (Allegrucci and Sauer, 2007), and the encapsulated isolated clinical pneumococcal were found to have impaired biofilm formation (Moscoso et al., 2006). Previously, several studies have demonstrated that the mutant strain of non-encapsulated pneumococcal showed stronger adhesion ability and enhanced biofilm formation ability than their encapsulated parents in vitro (Waite et al., 2001; Moscoso et al., 2006; Allegrucci and Sauer, 2007; McEllistrem et al., 2007). It is well known that Wzx/Wzy-dependent pathway is responsible for the formation of S. suis CPS (Wang K. et al., 2011). In this pathway, first, an initial monosaccharide is linked to the inner face of the cytoplasmic membrane by an initial sugar transferase. Second, other monosaccharides are joined sequentially by specific glycosyltransferases to assemble repeated units. Then, the repeated units are transported to the outer surface of the cytoplasmic membrane by Wzx flippase, and each repeated unit is combined and polymerized to form the lipid linked CP by Wzy polymerase. Finally, mature CPS is translocated to the peptidoglycan by the membrane protein complex (Okura et al., 2013). The genes involved in this pathway contain a gene cluster (cps gene cluster) and are usually located at the same chromosomal locus (Bentley et al., 2006). The cps gene cluster includes the genes encoding the initial sugar transferase, Wzx flippase (wzx), Wzy polymerase (wzy), additional glycosyltransferases, and enzymes to modify the repeated units or to add other moieties on CPS (Roberts, 1996; Bentley et al., 2006; Okura et al., 2013). Therefore, adhesion inhibitors were screened by affecting CPS biosynthesis.

Recently, few novel bactericidal or bacteriostatic agents have been developed and their antimicrobial activity lead to selective pressure, with antimicrobial resistance as an inevitable consequence of their use (Roca et al., 2015). For this reason, innovative antimicrobials with novel targets and modes of action are needed. A recently developed method aimed at interference with biofilm development without affecting bacterial growth compared to traditional bactericidal or bacteriostatic uses to inhibit biofilms (McDougald et al., 2012). Various natural products are successful in regulating biofilms development. The benefits of using natural products in biofilm inhibition are their higher specificity and lower toxicity compared to synthetic compounds (Koo and Jeon, 2009). For example, mulberry leaves has been shown to inhibit Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation by affecting bacterial adhesion (Islam et al., 2008).

Rutin, a well-known and widely used citrus flavonoid glycoside, has a lot of benefical pharmacological effects such as antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antihypertensive effects (Erlund et al., 2000; Middleton et al., 2000). It is found in many foods, such as orange, buckwheat, apple, onion, lemon, and grapefruit. In addition, rutin was identified as the principal anti-biofilm compounds in burdock leaf and inhibited biofilm formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by betabolomics-based screening (Lou et al., 2015). We have analyzed the relationship between the spectrum and the impact of Syringa oblata Lindl. aqueous extract on S. suis biofilms in vitro. According to high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) fingerprint and anti-biofilm activity test, gray relational analysis was applied to find the active composition. Rutin make significant contribution to anti-biofilm activity according to the relational grade analysis. Our previous results also showed that rutin was confirmed as the main anti-biofilm compounds in Syringa oblata Lindl. aqueous extract and truly affects S. suis biofilms in vitro (Bai et al., 2017).

In this work, we provided evidence that rutin inhibits the biofilm formation of S. suis by affecting CPS biosynthesis in vitro. The study explores the antibiofilm potential of rutin against S. suis which can be used as an adhesion inhibitor for the prevention of S. suis biofilm-related infections.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

Streptococcus suis (ATCC700794) was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. Bacteria were cultured aerobically as mentioned in our previous study (Yang et al., 2015). Briefly, bacteria grown at 37°C in Todd-Hewitt broth (THB; Sigma–Aldrich) or Todd-Hewitt broth agar (THA) added with 5% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Sijiqing Ltd, Hangzhou, China) (Yang et al., 2015).

Effectiveness of Rutin on Inhibition of Biofilm by the TCP Assay

The effect of rutin on S. suis biofilm formation was assayed as previously described (Bai et al., 2017). Briefly, a mid-exponential growth culture of S. suis was diluted to an optical density of 105–106 cells/mL. Then, 100 μL of cultures distributed in 96-well microplates (Corning Costar, NY, United States) containing 100 μL of sub-MICs of rutin solution (1/2 MIC (0.1563 mg/mL), 1/4 MIC (0.0781 mg/mL), 1/8 MIC (0.0391 mg/mL), and 1/16 MIC (0.0195 mg/mL)), negative control wells were included. After incubation for 72 h at 37°C without shaking, the wells were washed twice with distilled water, dried and fixed with 200 μL of 99% methanol for 5 min. Then, the wells were decanted, left to dry and stained with 200 μL of 2% crystal violet for another 5 min. Excess stain was rinsed off gently by water, the microplates were air dried, and the bound dye was solubilized with 200 μL of 33% glacial acetic acid. Crystal violet-stained bacteria were quantified measuring the A595 nm (DG5033A, Huadong Ltd, Nanjing, China). The reported values are the means of three measurements (Bai et al., 2017).

Growth Inhibitory Test

Growth inhibitory test was performed by the previously described method with minor modifications (Yang et al., 2015). Briefly, the culture medium was added with 1/4 MIC (0.0781 mg/mL) of rutin and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Control cells were also incubated in the absence of rutin. The rutin-treated and untreated cultures samples were taken every hour for measuring at OD600 nm.

Observation by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

A mid-exponential growth culture of S. suis was diluted to an optical density of 105–106 cells/mL. Then, a volume of 2 mL was added to a 6-well microplates (Corning Costar, NY, United States) containing a sterilized rough glass slide (1 cm × 1 cm). After culturing in stationary conditions for 72 h at 37°C, the glass slide were rinsed with sterile PBS in order to eliminate any non-adherent bacteria. The remaining biofilms were fixed with fixative solution (2 mM CaCl2 in 0.2 M cacodylate buffer, 2.5% (w/v) glutaraldehyde, 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde, pH 7.2) for 6 h and washed with PBS, then fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide containing 6% (w/v) sucrose and 2 mM potassium ferrocyanide in cacodylate buffer. The samples were dried, gold sputtered with an ion sputtering instrument (current 15 mA, 2 min) and observed using SEM (FEI Quanta, Netherland) (Bai et al., 2017).

Adhesion Assays

Adhesion assays was performed as previously described (Hamada et al., 1981). In brief, a mid-exponential growth culture of S. suis was diluted to an optical density of 105–106 cells/mL and each 2 mL [THB or 1/4MIC (0.0781 mg/mL) rutin] were added to a 6-well microplate (Corning Costar, NY, United States) containing sterilized rough organic membrane (1 cm × 1 cm). The plate were incubated in stationary conditions for for 24 h at 37°C, the non-adherent bacteria were decanted, and the remaining adherence were removed by 0.5 M of sodium hydroxide. Then, the cells were quantified at 600 nm. Percentage adherence = [OD600 of adhered cells/ (OD600 of adhered cells+OD600 of supernatant cells)].

PCR Amplification and Nucleotide Sequencing

To investigate whether rutin cause the cps gene mutation, a mid-exponential growth culture of S. suis was diluted to an optical density of 105–106 cells/mL and the culture medium was supplemented with 1/4 MIC (0.0781mg/mL) of rutin incubating at 37°C for 24 h. Control cells were also incubated in the absence of rutin. Chromosomal DNA from S. suis was prepared as previously described (Qin et al., 2006). Briefly, Bacterial colonies were suspended in 50 μL distilled water to extract DNA, followed by boiling for 5 min. Ex Taq DNA polymerase was used to perform PCR choosing the conditions: 94°C for 10 min, 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 57°C–60°C for 30 s (Details are shown in Table 1), and 72°C for 30 s; followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. The following primer pairs used in this work are listed in Table 1. The identity of the PCR product was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Sequence alignments were conducted using the BLAST program.

Table 1.

Primers used for the PCR.

| Genes | Primer sequence | Annealing temperature |

|---|---|---|

| cps 2A | Forward: 5′- TTCCACCCACCAAGTCGA -3′ | 60°C |

| Reverse: 5′- TGGCGGGCAAAATCAATA -3′ | ||

| cps 2B | Forward: 5′- TCTATTTCTGTGCGTGAT -3′ | 60°C |

| Reverse: 5′- TTGGAGTGGTTGGTTCTT -3′ | ||

| cps 2C | Forward: 5′- ATAACCTGAACGAGCATA -3′ | 57°C |

| Reverse: 5′- AGAGAGGGAGTAAATAAAAC -3′ | ||

| cps 2D | Forward: 5′- GATTTTTTCTGGTGTTTC -3′ | 60°C |

| Reverse: 5′- TCATATTTGGTGTGGATG -3′ | ||

| cps 2E | Forward: 5′- TGTCCATTTTGAACATCC -3′ | 60°C |

| Reverse: 5′- TTTTGCTCAGAAACGAGT -3′ | ||

| cps 2F | Forward: 5′- AGGACCAATCCGACAAGC -3′ | 60°C |

| Reverse: 5′- TGAACATAATGGAGCAAC -3′ | ||

| cps 2G | Forward: 5′- CATACCAATGACAAGAGC -3′ | 60°C |

| Reverse: 5′- GACCAAATCAGTGTAATCTA -3′ | ||

| cps 2H | Forward: 5′- GCCTCTTATTCAGGTTAT -3′ | 60°C |

| Reverse: 5′- CTTTTCTTTTTGTTTTCG -3′ | ||

| cps2I | Forward: 5′- GTACTCCATTGTCTTTGT -3′ | 57°C |

| Reverse: 5′- GAATTGTTTTTGATTCTT -3′ | ||

| cps 2J | Forward: 5′- ACCGCTCATATAATGATT -3′ | 57°C |

| Reverse: 5′- GGAGGGTTACTTGCTACT -3′ | ||

| cps 2K | Forward: 5′- CCAGCAACTGCCACAAGG -3′ | 57°C |

| Reverse: 5′- GCATAAGTCGCGCCAAGG -3′ | ||

| cps 2L | Forward: 5′- CAGAAAGCAACAGAAAAA -3′ | 60°C |

| Reverse: 5′- GAATCCAACAAATAGTAGAATA -3′ | ||

| cps 2M | Forward: 5′- AACAGGCAAATTAGAAAG -3′ | 60°C |

| Reverse: 5′- TGATAAAGTATGGACAGAAG -3′ | ||

| cps 2N | Forward: 5′- CTCGTGGGTGCGGTTTTA -3′ | 60°C |

| Reverse: 5′- CAGCCCTTGTCTTGGGATTA -3′ | ||

| cps 2O | Forward: 5′- CGATAGGGGCTGACTGAG -3′ | 57°C |

| Reverse: 5′- CGCGAGAAATTTGATGA -3′ | ||

| cps 2P | Forward: 5′- AAGCAGGGTAAGGGGTTG -3′ | 60°C |

| Reverse: 5′- ACTGGTATGGCTGTTATGGA -3′ | ||

| cps 2Q | Forward: 5′- CCGCTTCGATGTCTTTGA -3′ | 60°C |

| Reverse: 5′- TGGGATTATGCGTCGCTTAT -3′ | ||

| cps 2R | Forward: 5′- TATAGTGACGAAGACAGC -3′ | 60°C |

| Reverse: 5′-ATATTTTGAAGATAAACCG -3′ | ||

| cps 2S | Forward: 5′-AACAAGGCTAACAGACGA -3′ | 60°C |

| Reverse: 5′-GTGATGACGAAGGAAGAT -3′ | ||

| cps 2T | Forward: 5′-GCAACTAAAAATAAATTG -3′ | 57°C |

| Reverse: 5′-AAGAGTGCTCTAAGACCA -3′ | ||

| cps 2U | Forward: 5′-ATACCTCGCCATCTTTTA -3′ | 60°C |

| Reverse: 5′-GCTGATTCCCTCTTTTTG -3′ |

RNA Isolation and Quantitative RT-PCR

The quantitative Real-Time PCR was performed as described in our previous study (Yang et al., 2015). To investigate the effect of rutin on expression of cps gene, a mid-exponential growth culture of S. suis was diluted to an optical density of 105–106 cells/mL and the culture medium was added with 1/4 MIC (0.0781mg/mL) of rutin prior to further incubating at 37°C for 24 h. The control cells were also incubated without rutin. Bacteria were collected by centrifugation (12,000 ×g, 5 min, 4°C) and treated with an RNASE REMOVER I (Huayueyang Ltd, Beijing, China). RNA extraction was performed with an E.Z.N.A. Bacterial RNA isolating kit (Omega, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA (100 ng/mL) was reverse transcribed in S1000 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories) by using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase and random hexamers. The specific primers used for the quantitative RT-PCR (listed in Table 2) were designed by Takara Company (Takara Ltd, Dalian, Liaoning, China). The 16S rRNA gene was used for normalization of target genes. The amplification conditions for cps and 16S rRNA were 94°C for 10 min followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for 15 s, 60°C for 60 s and 72°C for 20 s, and then 72°C for 10 min (Yang et al., 2015).

Table 2.

Primers used for the quantitative RT-PCR analysis.

| Genes | Primer sequence |

|---|---|

| cps 2A | Forward: 5′-ATGAAAAAGAGAAGCGGACGAAGTA-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- TTATTTTTCAACAAGTACGGACTGA-3′ | |

| cps 2B | Forward: 5′-ATGAACAATCAAGAAGTAAATGCAA-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- CTATTTTAATTTCTTCGAATCTGGT-3′ | |

| cps 2C | Forward: 5′-ATGGCGATGTTAGAAATTGCACGTA-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- TTAGGCTTTTTTGCCGTAATTTCCG-3′ | |

| cps 2D | Forward: 5′-ATGATTGATATCCATTCGCATATCA-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- TTACTGTACTTGATTTTTCAATATC-3′ | |

| cps 2E | Forward: 5′-ATGAATATTGAAATAGGATATCGCC-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- TTACTTACTTCCCTCTCTCAACAAT-3′ | |

| cps 2F | Forward: 5′-ATGAGAACAGTTTATATTATTGGTT-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- TTATCCTTTAAACAACTTCTCATAC-3′ | |

| cps 2G | Forward: 5′-ATGAAAAAGATTCTATATCTCCATG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- TCAGTATACTTTGAGGGAGGTGTAG-3′ | |

| cps 2J | Forward: 5′-ATGGAAAAAGTCAGCATTATTGTAC-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- TTAATCATTATTTTTTTCTTCCCTA-3′ | |

| cps 2K | Forward: 5′-ATGATTAACATTTCTATCATCGTCC-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- TTACCGAGTACTACTTTCACTTCTT-3′ | |

| cps 2L | Forward: 5′-ATGAATCCAACAAATAGTAGAATAG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- TCAGATGGTTCTCGAATAGCTCAAT-3′ | |

| cps 2M | Forward: 5′-GTGCGTTCCAAGGTAGATACTTTCA-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- TTATCGTTTTCCACGTACTCTCATA-3′ | |

| cps 2N | Forward: 5′-TTGAGACGAATTTATATTTGCCATA-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- CTATTCTATCCCCTCACGCAAAATA-3′ | |

| cps 2P | Forward: 5′-ATGGTTTATATTATTGCAGAAATTG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- TTACATTTGATTTTCAAAAGCACTA-3′ | |

| cps 2Q | Forward: 5′-ATGAAAAAAATTTGTTTTGTGACAG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- CTATCTATCATAAAACTCTTTCATG-3′ | |

| cps 2R | Forward: 5′-ATGAAAAAAGTAGCCTTTCTAGGAG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- CTATTTAATCTTTCTAGCAGGTACA-3′ | |

| cps 2S | Forward: 5′-ATGGAACCAATTTGTCTGATTCCTG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- TTATCTTGTCAAACTTGTCAAAATC-3′ | |

| cps 2T | Forward: 5′-ATGAAGCAATTGCTACAGTATTATT-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- CTAATAGTATTTTAATATATACTCC-3′ | |

| cps 2U | Forward: 5′-TTGTTAGTTTATAATTTGGCTAGAG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- TTAAAAAAGGGACTTCAACTTCAAT-3′ | |

| cps 2V | Forward: 5′-TTATAATGCACTAGTATACTGTATA-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- ATGTCTCATTGGAATCAATTTTTAA-3′ | |

| 16S rRNA | Forward: 5′- TGCTAGTCACCGTAAGGCTAAG -3′ |

| Reverse: 5′- GGCTGCAAGATTTCCTTGAT -3′ |

Capsule Extraction, and Capsular Polysaccharide Purification and Isolation

Bacteria were grown in 50 mL of Todd Hewitt broth (THB) at 37°C for 24 h, diluted to 5 L in fresh THB with 1/4 MIC (0.0781 mg/mL) rutin, and cultured for 24 h. Control cells were incubated without rutin. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 10000 g, suspended in 0.1 mol/L-1 Glycine-buffer (Biotopped Ltd, Beijing, China) solution pH 9.2. The CPS was prepared as previously described (Katsumi et al., 1996), with some modifications. Briefly, nucleic acids were removed by precipitation by adding 0.1 mol/L-1 CaCl2 (Tianli Ltd, Tianjin, China) and ethanol (Tianli Ltd, Tianjin, China) to 25% v/v, and then centrifuged at 7000 g at 25°C. The ethanol concentration in the supernatant was enhanced to 80% v/v to precipitate the CPS. The suspension was centrifuged (9000 g at 4°C) after overnight at 4 °C. The CPS was purified by gel filtration chromatography on a column filled with Sephacryl S-300 (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). The elusion was performed with 50 mmol/L-1 NH4HCO3 (Zhiyuan Ltd, Tianjin, China) at a flow rate of 1.3 mL/min-1. Purification was collected and freeze dried. The polysaccharides content was determined by the method (using phenol sulfuric acid) described previously (Dubois et al., 1951).

The Desialylated Polysaccharide Production

Thirty microgram of sample was hydrolyzed with 0.1 mol/L-1 trifluoroacetic acid to determine the composition of monosaccharide (TFA; Zhiyuan Ltd, Tianjin, China) (5 mL) at 80°C for 60 min, and then centrifuged at 10000 g for 5 min using ultrafiltration centrifuge tube (Millipore, Billerica, MA, United States). The centrifugation step was repeated three times, and the samples were collected. The top samples are the desialylated polysaccharide, and the bottom samples are the sialic acid. The solution was evaporated to dryness with a stream of N2 at room temperature. The precipitation was collected, respectively.

PMP–HPLC Analysis

Alternatively, in order to determine the composition of monosaccharide, 1 mg of sample was hydrolyzed with 2mol/L-1 trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (0.5 mL) at 120°C for 100 min, at 120°C for 100 min, followed by evaporation with N2. Polysaccharide hydrolyzate and monosaccharide standard [glucose (Glc), N-acetylglucosamine (GlcN), galactose (Gal), rhamnose (Rha)] (Jinshui Ltd, Shanghai, China) by pre-column derivatization with 1-phenyl-3-methyl-5-pyrazolone (PMP; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, United States). The hydrolysates were fully converted to its PMP derivatives according to the previous method (Guitang et al., 2007), with few modifications. Briefly, the sample was dissolved in 100 μL of H2O, and mixed with 100 μL of 0.3 mol/L NaOH (Tianli Ltd, Tianjin, China) and 120 μL of 0.5 mol/L PMP. The mixture was allowed to react for 30 min at 70°C. Then, 100 μL of HCl (0.3 mol/L) (Ligong Ltd, Harbin, Heilongjiang, China) was added to the mixture and 500 μL of chloroform (Ligong Ltd, Harbin, Heilongjiang, China) was added to extract the remaining PMP. The extraction process was repeated three times. The PMP derivatized sample solution was filtrated through a 0.22 μm membrane. Then the compositions of monosaccharide were determined by HPLC (Waters, Shanghai, China) with an UV detector at 245.0 nm on a Waters chromatograph. The mobile phase was made of Methanol (Kemiou Ltd, Tianjin, China) (A) and 0.01 mol/mL formic acid (Kemiou Ltd, Tianjin, China) (pH 6.8) (B) (A:B = 82:18, v/v). With 20 μL of injection volume, separation was performed on a Spherisorb-C18 Column (Waters, Shanghai, China) (5 μm, 250 mm × 4.6 mm) at 30°C and 1 mL/min of flow rate.

Analysis of Sialic Acid by the Fluorometric HPLC Methods

The sialic acid samples and N-acetylgucosamine acid (Neu5Ac; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, United States) were added 0.2 mL of 0.01 mol/L-1 TFA and 0.2 mL of 7 mmol/L-1 DMB (TCI, Tokyo, Japan) solution in 5 mmol/L trifluoroacetic acid containing 1 mol/L 2-mercaptoethanol and 18 mmol/L sodium hydrosulfite (Guangfu, Tianjin, China), and incubated at 60°C for 2 h. The sample solution filtrated through a 0.22 μm membrane after derivatized by DMB. The composition of monosaccharide was determined by HPLC equipped with an EV detector (Ex 373 nm and Em 448nm) on a Waters chromatographic system. The mobile phase was made of CH3OH (A), CH3CN (Kemiou Ltd, Tianjin, China) (B) and 0.05% TFA (C) (A: B: C = 6:4:90, v/v/v). Separation was performed on a Spherisorb-C18 Column (5 μm, 250 mm × 4.6 mm) at 26°C and 1 mL/min of flow rate at an injection volume of 20 μL.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

The polysaccharide and the desialylated polysaccharide were exchanged in 33 mmol/L-1 phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) in 2H2O (99.9 atom% 2H), freeze dried, and dissolved in the same amount of 2H2O (99.96 atom% 2H). Nuclear magnetic resonance (Bruker, Beijing, China, NMR) spectra were acquired on polysaccharide samples at concentrations of circa (1%–3%).

Statistical Analysis

All the assays were performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as means ± standard deviations. Data were analyzed by the Student’s t-test. Statistics were determined using SPSS software, version 18.0.

Results

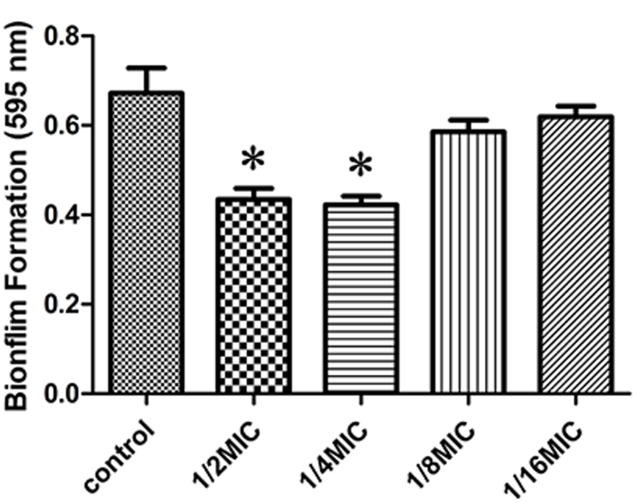

Effectiveness of Rutin on Inhibition of Biofilm Formation by the TCP Assay

We determined the effect of sub-inhibitory concentrations of rutin on biofilm production in vitro. The MIC values of rutin for S. suis was 0.3125 μg⋅mL-1. As shown in Figure 1, 1/2 MIC (0.1563 mg/mL) and 1/4 MIC (0.0781 mg/mL) of rutin were able to significantly inhibit biofilm production (p < 0.05). Rutin at 1/8 MIC (0.0391 mg/mL) and 1/16 MIC (0.0195 mg/mL) had no significant effect on S. suis biofilm formation.

FIGURE 1.

Effect of rutin at different concentrations on Streptococcus suis biofilm formation. The data are expressed as the means ± standard deviations. Asterisk indicates statistically significant difference of treatment versus untreated culture (∗p < 0.05).

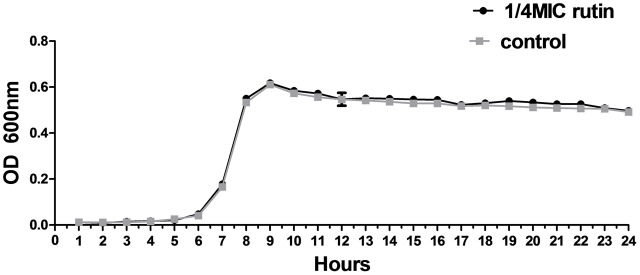

Growth Inhibitory Activity of Rutin

The growth of S. suis was measured for cultures with 0 MIC and 1/4 MIC (0.0781 mg/mL) of rutin. The growth curves for 1/4 MIC of rutin were not significantly different in lag, exponential, and stationary phases during 24 h of incubation (Figure 2). The results suggested that the growth of S. suis was unaffected by the addition of 1/4 MIC (0.0781 mg/mL) rutin.

FIGURE 2.

Growth curve of S. suis in the absence of rutin and in the presence of rutin at 1/4 MIC (0.0781 mg/ml). The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviations.

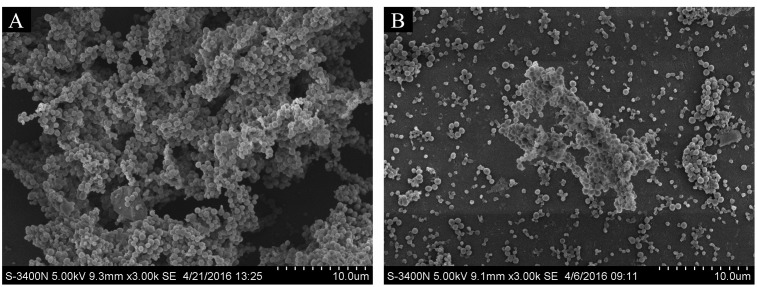

Direct Observation of Biofilm Formation In Vitro by SEM

To observe the effect of rutin on biofilm production, the architecture of biofilms formed in the absence or in the presence 1/4 MIC (0.0781 mg/mL) of rutin was studied by SEM. As shown in Figure 3A, when biofilm was formed in the absence of rutin, the aggregates and microcolonies of S. suis covered almost entirely the glass slide surface. However, when biofilm was formed in the presence 1/4 MIC (0.0781 mg/mL) of rutin, a marked variability in the three-dimensional biofilm architecture was noted. Biofilm thickness is thin and bacteria are scattered (Figure 3B). These results suggested that rutin at 1/4MIC (0.0781 mg/mL) significantly inhibited the biofilm formation of S. suis in vitro.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of rutin on S. suis biofilm by scanning electron microscope. Biofilm formation of S. suis without rutin (A). Biofilm formation of S. suis with 1/4 MIC (0.0781 mg/ml) rutin treatment (B).

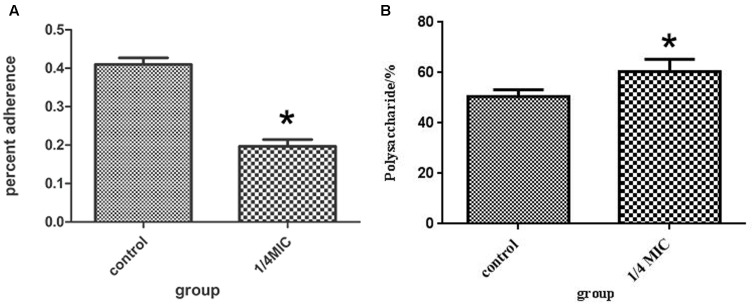

Anti-adherence Activity of Extract Against S. suis

The inhibitory effects at 1/4 MIC (0.0781 mg/mL) of rutin on adherence of S. suis are shown in Figure 4A. The rutin inhibited adherence in a pronounced manner. The anti-adherence rate of S. suis is 20% at a concentration of 1/4MIC (0.0781 mg/mL) of rutin.

FIGURE 4.

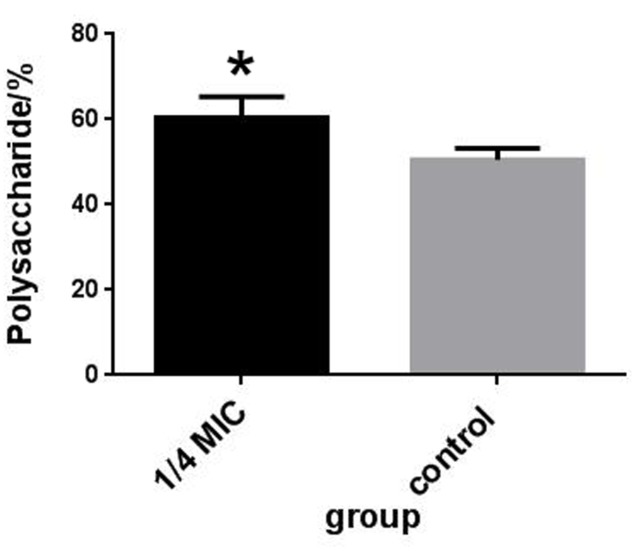

Effect of 1/4 MIC (0.0781 mg/ml) rutin on S. suis adhesion (A). Effect of 1/4 MIC (0.0781 mg/ml) rutin on the polysaccharides content of S. suis (B). The data are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Asterisk indicates statistically significant difference of treatment versus untreated culture (∗p < 0.05).

PCR Amplification and Nucleotide Sequencing

The mapping of the cps genes in the genome of S. suis by PCR are shown in Figure 5. Sequencing was performed to confirm that no mutation occurred. Detailed information is shown in the Supplementary Figures S1–S21. The Supplementary Figures S1–S21 shows the results of cps2A-cps2U sequence alignment. The sequence of the cps gene cluster has no difference between rutin-treated and untreated cells.

FIGURE 5.

Mapping of the cps in the genome of S. suis by PCR. The 1–21 stands for cps2A–2U, respectively.

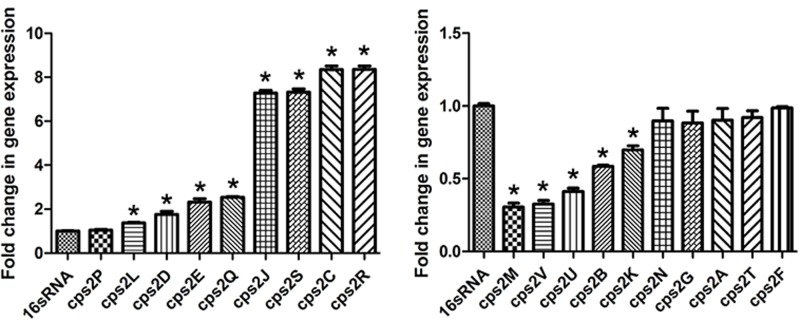

The Effect of 1/4 MIC of Rutin on Expression of cps Genes

Thereafter, the effect of rutin on the expression profile of cps gene cluster was analyzed. As displayed in Figure 6, when the culture medium was in the presence 1/4 MIC (0.0781 mg/mL) of rutin, expression of the genes cps2C, cps2D, cps2E, cps2J, cps2L, cps2R, and cps2Q was up regulated. However, the expression of the genes cps2B, cps2M, cps2K, cps2U, and cps2V was down regulated.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of rutin on mRNA expression of cps genes in S. suis. The data are expressed as means ± standard deviations. The expression was normalized to 16S rRNA. Controls refer to the absence of rutin. Asterisk indicates statistically significant difference of treatment versus untreated culture (∗p < 0.05).

Capsule Polysaccharide Content Determination

The rutin effect for polysaccharides content of S. suis was shown in Figure 4B. The contents of total sugar were analyzed by phenol-sulfuric method. 50.54 ± 2.69 % and 60.46 ± 4.91 % of the polysaccharides content were observed in the control and rutin group, respectively (P < 0.05). The results suggested that the polysaccharides content significantly increased when the bacteria was incubated with rutin.

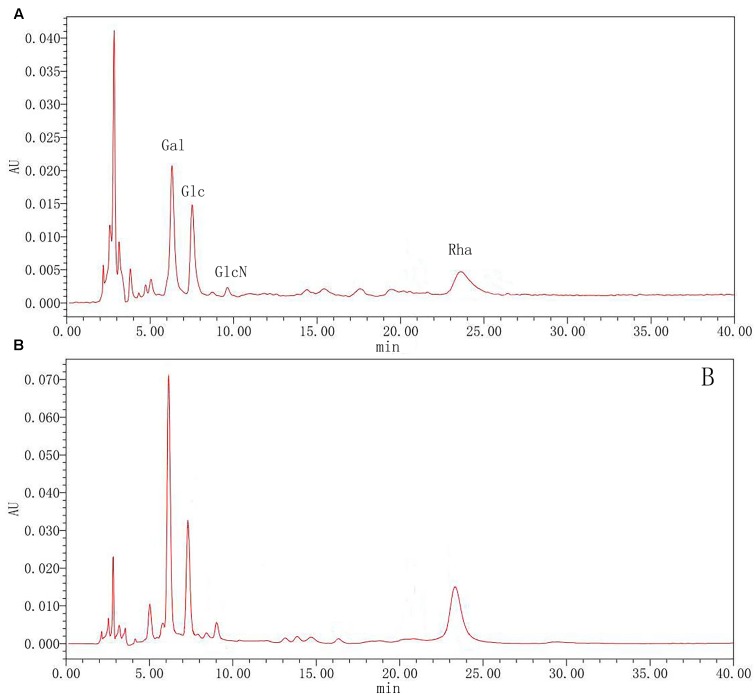

HPLC Characterization of Polysaccharides

To further clarify polysaccharides, the compositions were examined by acid hydrolysis and HPLC. After PMP derivatization, the composition of monosaccharides from the hydrolyzed products was examined by HPLC. From the chromatograms, Glc and Gla, GlcN and Rha were detected in both rutin group and control group. As shown in Figure 7, the results showed that there was the no significant difference between the rutin and control group. The molar ratio of monosaccharides (Rha: Gal: Glc: GlcN) was 1:2.22:0.95:0.76 and 1: 2.03: 1.29: 0.74 for the rutin group and control group, respectively. These results exhibited that the monosaccharide compositions had no significant difference when the culture medium was added with 1/4 MIC (0.0781 mg/mL) rutin.

FIGURE 7.

High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) chromatograms of monosaccharides after hydrolysis of polysaccharide in control (A) and rutin (B) groups.

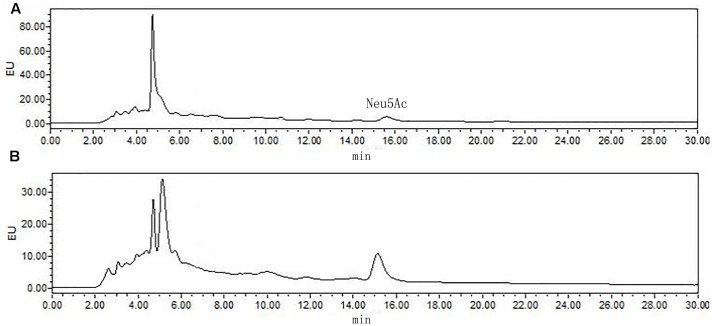

The most significant feature of the sialic acid is their instability. DMB possess significant advantages in its specific reactivity with the α-keto acids of sialic acids. After DMB derivatization, the sialic acid from the hydrolyzed products was determined by HPLC. As shown in Figure 8, Neu5Ac was detected in the product of the rutin group and the control group. The ratio of sialic acid content of the control and rutin group was 1:1.84. The results of HPLC suggested that the content of Rha, Glc, Gal, GlcN, and Neu5Ac of rutin group was generally higher than that of control group.

FIGURE 8.

High performance liquid chromatography chromatograms of sialic acid (Neu5Ac) in control (A) and rutin (B) groups.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

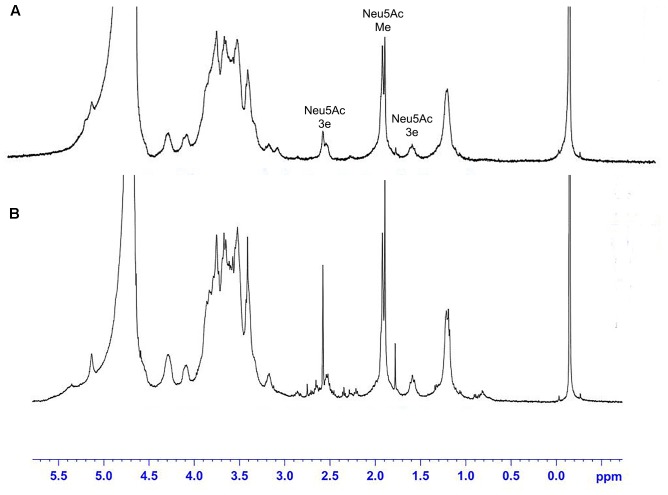

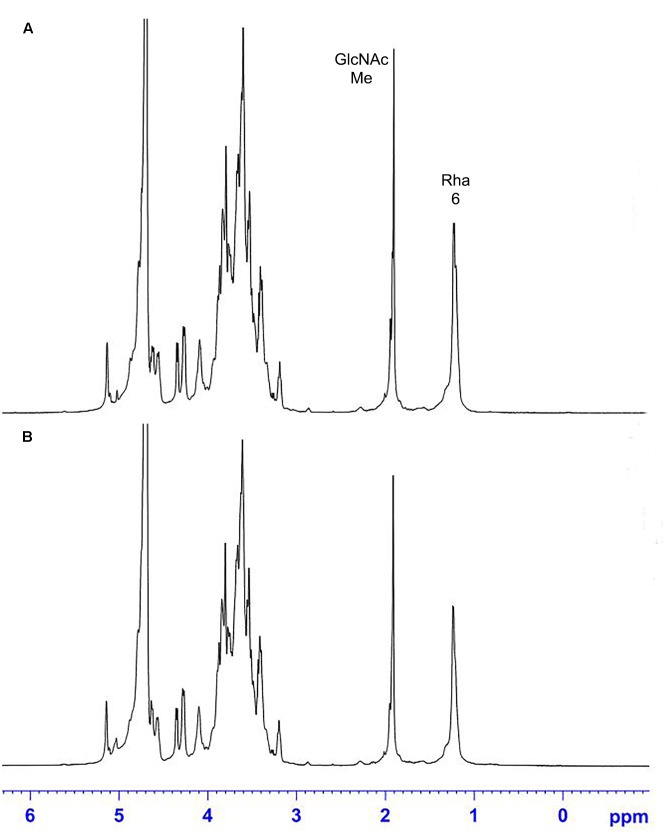

The 1H NMR spectra of the S. suis CPS of rutin group and control group before and after desialylated are shown in Figures 9, 10. The same spectra was observed in the 1H NMR spectra of the S. suis CPS after and before acid hydrolysis reported by the Van Calsteren (Van Calsteren et al., 2010). The 1H NMR spectra of the polysaccharides of S. suis of control group and rutin group are shown in Figure 9. There was conformity between two polysaccharides for their 1H NMR spectra. The 1H NMR spectra of the desialylated polysaccharides of S. suis control group and rutin treated group are shown in Figure 10. The result showed that there was no difference between the structures of two desialylated polysaccharide. On the 1H NMR spectra, polysaccharide signals were concentrated in the δ 3.3 ∼ 4.0 ppm range. Reporter resonance signals were identified on both spectra: acetyl methyl protons of N-acetylglucosamine near δ 2.0, and methyl protons in position 6 of rhamnose at crica δ 1.2. Signals characteristic of sialic acid, that is, acetyl methyl protons near δ 2.0 and methylene protons in position 3 at δ 2.579 and 1.591 vanished fully after hydrolysis. The only difference between the spectra of the Figures 9, 10 was the loss of the sialic acid signals.

FIGURE 9.

500 MHz 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra of capsular polysaccharide in control (A) and rutin (B) groups.

FIGURE 10.

500 MHz 1H NMR spectra of desialylated polysaccharide in control (A) and rutin (B) groups.

Discussion

In this work the ability of rutin to inhabit S. suis biofilms was investigated by TCP assay and SEM. The TCP assay according to the ability of bacteria to form biofilms on the microplates indicated indirectly that the sub-inhibitory concentrations of rutin could inhibit the S. suis biofilm formation in vitro. Then, the effect of rutin on the structure of biofilm of S. suis was observed directly by SEM. Our results showed that rutin could inhibit S. suis biofilm formation at 1/4MIC (0.0781 mg/mL). However, it is still unclear why rutin affects S. suis biofilms in vitro. In addition, a question remained unanswered: how does rutin affect S. suis biofilms at the molecular level? Then, we investigated the influence of rutin on S. suis growth in vitro. The results suggested that rutin could significantly inhibit biofilm formation of S. suis but had had no effect on its growth by the addition of 1/4MIC (0.0781 mg/mL) rutin. Rutin was previously shown to affect attachment of Staphylococcal aureus (Liu et al., 2015) and inhibit the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation (Lou et al., 2015). Thus, anti-adherence activity of rutin was investigated. Our results showed that rutin inhibited adherence in an obvious manner.

Previous reports had demonstrated that CPS was play an important role in the adhesion of host cells (Allegrucci and Sauer, 2007), and the encapsulated clinical pneumococcal isolates have impaired biofilm formation (Moscoso et al., 2006). The structure of the CPS can also affect biofilm formation. For example, the α-D-Glc is partially replaced with α-D-GlcNAc in Vibrio cholera polysaccharide which gives it high viscosity and promotes biofilm formation (Yildiz et al., 2014). Thus, the content and structure of S. suis CPS were detected. Results showed that rutin are beneficial to improve the CPS content of S. suis. Elliott and Tai (Elliott and Tai, 1978) defined the capsular polysaccharide of S. suis as consisting of five sugars including Rha, Glc, Gal, GlcNAc and Neu5Ac. The polysaccharides in the rutin and control group contained five monosaccharides as above after hydrolysis and derivation. It is consistent with the results of Elliott and Tai (1978). Van Calsteren has given the description about the sugar structure of S. suis CPS (Van Calsteren et al., 2010). In this study, the same 1H NMR spectra was observed in S. suis CPS when S. suis was cultivated in the presence of rutin. Our findings are in consistent with the results of Van Calsteren (Van Calsteren et al., 2010). According to our results, rutin had no effect on the structure of S. suis CPS. Therefore, rutin may affect the capsular polysaccharide content and then affect the bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation.

Finally, we addressed the question that how rutin resulted in an increased content of S. suis capsular polysaccharide. It has been stated earlier that multiple genes involved in the synthesis of CPS. Smith et al. (1999) identified cps gene cluster which is essential for the synthesis of the repeating unit of CPS and found that CPS is comprised of Glc, Gal, GlcN, Rha, and Neu5Ac. Van Calsteren et al. (2010) elucidated CPS structure of S. suis and predicted the cps genes responsible for the synthesis of CPS repeating units. In addition, S. suis CPS were considered to be synthesized by the wzx/wzy-dependent pathway due to possession of wzx and wzy genes (Wang K. et al., 2011; Okura et al., 2013). The genes in wzx/wzy-dependent pathway comprise of cps gene cluster and are usually located at the same locus on chromosome (Bentley et al., 2006).

It has been predicted previously that cps2E gene was the initiating gene in the process of the synthesis of the repeating unit of CPS, and the removal of cps2E gene led to the complete absence of CPS, as was previously reported in Streptococcus pneumoniae (Cartee et al., 2005). In our study, we found that cps2E gene was significantly upregulated in the presence of rutin. The up regulation of cps2E may promote the synthesis of the capsular polysaccharide and thus inhibit biofilm formation. It has been demonstrated that the gene cps2L was responsible for the synthesis of sialyltrans-ferase which in turn mediate the transfer of sialic acid to CPS repeating units (Van Calsteren et al., 2010). The sialic acid played a major role in the regulation of bacterial adhesion (Charland et al., 1996; Segura and Gottschalk, 2002; Lewis et al., 2012). The expression level of cps2L gene was up regulated in the present study. The up regulation of cps2L may promote the synthesis of the capsular polysaccharide.

Previously, it has been predicted that the gene cps2G and cps2J were involved in the synthesis of long side chain and short side chain of cps units (Van Calsteren et al., 2010). Although the expression level of cps2G gene did not change, the expression level of cps2J gene was up regulated in the present study. Furthermore, cps2L, cps2E, cps2J, and cps2G gene were found in S. suis responsible for different glycosyltransferases involved in CPS synthesis. The above four deletion mutants with their sialic acid content decreased and CPS incomplete in S. suis SC19 and indicated enhanced adhesion to host cells (Zhang et al., 2016). Therefore, the up regulation of cps2J may promote the synthesis of the capsular polysaccharide.

It has been demonstrated that CpsD is an autophosphorylating tyrosine kinase regulated by CpsC that is required for CpsD tyrosine phosphorylation (Morona et al., 2000; Bender and Yother, 2001) and both may be important regulators connecting capsule synthesis to cell division. CpsB is a manganese dependent tyrosine phosphatase that influences dephosphorylation of CpsD, as a kinase inhibitor, autophosphorylation of CpsB may prevent CpsD in its C-terminal tyrosine and weaken the activity of the CpsD protein, and inhibit the production of capsular polysaccharide. It has been mentioned earlier that a cps2D-deleted strain produced lesser amount of CPS was avirulent (Morona et al., 2004). Much higher expressions were detected for cps2C and cps2D when S. suis was cultivated in the presence of rutin. The expression level of cps2A and cps2B gene was down regulated in the present study. cpsB, cpsC, and cpsD are essential for encapsulation, while cpsA is not necessary as previously reported (Morona et al., 2004). So, the expression level of cps2A gene down regulated may have no effect on the amount of capsular polysaccharide. These data suggested that the cps2B, cps2C, and cps2D expression might be partly responsible for the reduced biofilm. However, the detailed molecular mechanism still unknown.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate that 1/4MIC (0.0781 mg/mL) of rutin inhibits S. suis biofilm formation without impairing its growth in vitro. We investigate the effect of rutin on S. suis CPS content and structure. The results reveal that rutin is beneficial to improve the polysaccharide content of S. suis without changing its structure. The potential mechanism may be that rutin is beneficial to improve the polysaccharide content of S. suis which affects bacterial adhesion. The cps2B, cps2C, cps2D, cps2E, cps2J, and cps2L might be responsible for the reduced biofilm. Altogether our findings demonstrate that rutin interfers with CPS synthesis in S. suis and thereby decreases biofilm formation of S. suis. Thus, our findings found the rough regulation of S. suis biofilm formation that may be utilized potentially to manage S. suis biofilm infections.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: YL. Performed the experiments: SW, CW, LG, YZ, YY, CX. Analyzed the data: WD, JC, IM, XC. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: HC, XH, DL.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31472231), National Science and Technology Support Plan of China (No. 2015BAD11B00), and Ministry of agriculture pig industry system (CARS-36).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphar.2017.00379/full#supplementary-material

Effect of rutin on cps gene sequences.

References

- Allegrucci M., Sauer K. (2007). Characterization of colony morphology variants isolated from Streptococcus pneumoniae biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 189 2030–2038. 10.1128/JB.01369-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai J., Yang Y., Wang S., Gao L., Chen J., Ren Y., et al. (2017). Syringa oblata Lindl. Aqueous extract is a potential biofilm inhibitor in S. suis. Front. Pharmacol. 8:26 10.3389/fphar.2017.00026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender M. H., Yother J. (2001). CpsB is a modulator of capsule-associated tyrosine kinase activity in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Biol. Chem. 276 47966–47974. 10.1074/jbc.M105448200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley S. D., Aanensen D. M., Mavroidi A., Saunders D., Rabbinowitsch E., Collins M., et al. (2006). Genetic analysis of the capsular biosynthetic locus from all 90 pneumococcal serotypes. PLoS Genet. 2:e31 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartee R. T., Forsee W. T., Bender M. H., Ambrose K. D., Yother J. (2005). CpsE from type 2 Streptococcus pneumoniae catalyzes the reversible addition of glucose-1-phosphate to a polyprenyl phosphate acceptor, initiating type 2 capsule repeat unit formation. J. Bacteriol. 187 7425–7433. 10.1128/JB.187.21.7425-7433.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charland N., Kobisch M., Martineau-Doize B., Jacques M., Gottschalk M. (1996). Role of capsular sialic acid in virulence and resistance to phagocytosis of Streptococcus suis capsular type 2. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 14 195–203. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1996.tb00287.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon B. P. (2014). Staphylococcus aureus chronic and relapsing infections: evidence of a role for persister cells: an investigation of persister cells, their formation and their role in S. aureus disease. Bioessays 36 991–996. 10.1002/bies.201400080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M., Gilles K., Hamilton J. K., Rebers P. A., Smith F. (1951). A colorimetric method for the determination of sugars. Nature 168 167 10.1038/168167a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott S. D., Tai J. Y. (1978). The type-specific polysaccharides of Streptococcus suis. J. Exp. Med. 148 1699–1704. 10.1084/jem.148.6.1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlund I., Kosonen T., Alfthan G., Maenpaa J., Perttunen K., Kenraali J., et al. (2000). Pharmacokinetics of quercetin from quercetin aglycone and rutin in healthy volunteers. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 56 545–553. 10.1007/s002280000197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fux C. A., Costerton J. W., Stewart P. S., Stoodley P. (2005). Survival strategies of infectious biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 13 34–40. 10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P., Das J., Foley I. (1997). Biofilm susceptibility to antimicrobials. Adv. Dent. Res. 11 160–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk M., Segura M., Xu J. (2007). Streptococcus suis infections in humans: the Chinese experience and the situation in North America. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 8 29–45. 10.1017/S1466252307001247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk M., Xu J., Calzas C., Segura M. (2010). Streptococcus suis: a new emerging or an old neglected zoonotic pathogen? Future Microbiol. 5 371–391. 10.2217/fmb.10.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitang H. A. O., Shangwei C., Song Z. H. U., Hongping Y. I. N., Jun D. A. I., Yuhua C. A. O. (2007). Analysis of monosaccharides and uronic acids in polysaccharides by pre-column derivatization with p-aminobenzoic acid and high performance liquid chromatography. Chin. J. Chromatogr. 25 75–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada S., Torii M., Kotani S., Tsuchitani Y. (1981). Adherence of Streptococcus sanguis clinical isolates to smooth surfaces and interactions of the isolates with Streptococcus mutans glucosyltransferase. Infect. Immun. 32 364–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam B., Khan S. N., Haque I., Alam M., Mushfiq M., Khan A. U. (2008). Novel anti-adherence activity of mulberry leaves: inhibition of Streptococcus mutans biofilm by 1-deoxynojirimycin isolated from Morus alba. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62 751–757. 10.1093/jac/dkn253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsumi M., Saito T., Kataoka Y., Itoh T., Kikuchi N., Hiramune T. (1996). Comparative preparation methods of sialylated capsule antigen from Streptococcus suis type 2 with type specific antigenicity. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 58 947–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiedrowski M. R., Horswill A. R. (2011). “New approaches for treating staphylococcal biofilm infections,” in Antimicrobial Therapeutics Reviews: Antibiotics That Target the Ribosome, ed. Bush K. (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; ), 104–121. [Google Scholar]

- Koo H., Jeon J. G. (2009). Naturally occurring molecules as alternative therapeutic agents against cariogenic biofilms. Adv. Dent. Res. 21 63–68. 10.1177/0895937409335629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis L. A., Carter M., Ram S. (2012). The relative roles of factor H binding protein, neisserial surface protein A, and lipooligosaccharide sialylation in regulation of the alternative pathway of complement on meningococci. J. Immunol. 188 5063–5072. 10.4049/jimmunol.1103748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Chen F., Bi C., Wang L., Zhong X., Cai H., et al. (2015). Quercitrin, an inhibitor of Sortase A, interferes with the adhesion of Staphylococcal aureus. Molecules 20 6533–6543. 10.3390/molecules20046533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Z., Tang Y., Song X., Wang H. (2015). Metabolomics-based screening of biofilm-inhibitory compounds against Pseudomonas aeruginosa from burdock leaf. Molecules 20 16266–16277. 10.3390/molecules200916266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougald D., Rice S. A., Barraud N., Steinberg P. D., Kjelleberg S. (2012). Should we stay or should we go: mechanisms and ecological consequences for biofilm dispersal. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10 39–50. 10.1038/nrmicro2695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEllistrem M. C., Ransford J. V., Khan S. A. (2007). Characterization of in vitro biofilm-associated pneumococcal phase variants of a clinically relevant serotype 3 clone. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45 97–101. 10.1128/JCM.01658-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton E., Jr., Kandaswami C., Theoharides T. C. (2000). The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: implications for inflammation, heart disease, and cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 52 673–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morona J. K., Miller D. C., Morona R., Paton J. C. (2004). The effect that mutations in the conserved capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis genes cpsA, cpsB, and cpsD have on virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 189 1905–1913. 10.1086/383352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morona J. K., Paton J. C., Miller D. C., Morona R. (2000). Tyrosine phosphorylation of CpsD negatively regulates capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis in streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 35 1431–1442. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01808.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscoso M., Garcia E., Lopez R. (2006). Biofilm formation by Streptococcus pneumoniae: role of choline, extracellular DNA, and capsular polysaccharide in microbial accretion. J. Bacteriol. 188 7785–7795. 10.1128/JB.00673-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okura M., Takamatsu D., Maruyama F., Nozawa T., Nakagawa I., Osaki M., et al. (2013). Genetic analysis of capsular polysaccharide synthesis gene clusters from all serotypes of Streptococcus suis: potential mechanisms for generation of capsular variation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79 2796–2806. 10.1128/AEM.03742-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L., Watanabe H., Yoshimine H., Guio H., Watanabe K., Kawakami K., et al. (2006). Antimicrobial susceptibility and serotype distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated from patients with community-acquired pneumonia and molecular analysis of multidrug-resistant serotype 19F and 23F strains in Japan. Epidemiol. Infect. 134 1188–1194. 10.1017/S0950268806006303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts I. S. (1996). The biochemistry and genetics of capsular polysaccharide production in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50 285–315. 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roca I., Akova M., Baquero F., Carlet J., Cavaleri M., Coenen S., et al. (2015). The global threat of antimicrobial resistance: science for intervention. New Microbes New Infect. 6 22–29. 10.1016/j.nmni.2015.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura M., Gottschalk M. (2002). Streptococcus suis interactions with the murine macrophage cell line J774: adhesion and cytotoxicity. Infect. Immun. 70 4312–4322. 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4312-4322.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. E., Damman M., Van Der Velde J., Wagenaar F., Wisselink H. J., Stockhofe-Zurwieden N., et al. (1999). Identification and characterization of the cps locus of Streptococcus suis serotype 2: the capsule protects against phagocytosis and is an important virulence factor. Infect. Immun. 67 1750–1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriskandan S., Slater J. D. (2006). Invasive disease and toxic shock due to zoonotic Streptococcus suis: an emerging infection in the East? PLoS Med. 3:e187 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Calsteren M.-R., Gagnon F., Lacouture S., Fittipaldi N., Gottschalk M. (2010). Structure determination of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 capsular polysaccharide. Biochem. Cell Biol. 88 513–525. 10.1139/o09-170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite R. D., Struthers J. K., Dowson C. G. (2001). Spontaneous sequence duplication within an open reading frame of the pneumococcal type 3 capsule locus causes high-frequency phase variation. Mol. Microbiol. 42 1223–1232. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02674.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Fan W. X., Cai L. J., Huang B. X., Lu C. P. (2011). Genetic analysis of the capsular polysaccharide synthesis locus in 15 Streptococcus suis serotypes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 324 117–124. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02394.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Zhang W., Wu Z., Lu C. (2011). Reduced virulence is an important characteristic of biofilm infection of Streptococcus suis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 316 36–43. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02189.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W.-Z., Yu H.-J., Jing H.-Q., Xu J.-G., Chen Z.-H., Zhu X.-P., et al. (2006). An outbreak of human Streptococcus suis serotype 2 infections presenting with toxic shock syndrome in Sichuan, China. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi 27 185–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. B., Wang S., Wang C., Huang Q. Y., Bai J. W., Chen J. Q., et al. (2015). Emodin affects biofilm formation and expression of virulence factors in Streptococcus suis ATCC700794. Arch. Microbiol. 197 1173–1180. 10.1007/s00203-015-1158-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz F., Fong J., Sadovskaya I., Grard T., Vinogradov E. (2014). Structural characterization of the extracellular polysaccharide from Vibrio cholerae O1 El-Tor. PLoS ONE 9:e86751 10.1371/journal.pone.0086751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Ding D., Liu M., Yang X., Zong B., Wang X., et al. (2016). Effect of the glycosyltransferases on the capsular polysaccharide synthesis of Streptococcus suis serotype 2. Microbiol. Res. 185 45–54. 10.1016/j.micres.2016.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Effect of rutin on cps gene sequences.