ABSTRACT

Azospirillum brasilense Sp7 uses glycerol as a carbon source for growth and nitrogen fixation. When grown in medium containing glycerol as a source of carbon, it upregulates the expression of a protein which was identified as quinoprotein alcohol dehydrogenase (ExaA). Inactivation of exaA adversely affects the growth of A. brasilense on glycerol. A determination of the transcription start site of exaA revealed an RpoN-dependent −12/−24 promoter consensus. The expression of an exaA::lacZ fusion was induced maximally by glycerol and was dependent on σ54. Bioinformatic analysis of the sequence flanking the −12/−24 promoter revealed a 17-bp sequence motif with a dyad symmetry of 6 nucleotides upstream of the promoter, the disruption of which caused a drastic reduction in promoter activity. The electrophoretic mobility of a DNA fragment containing the 17-bp sequence motif was retarded by purified EraR, a LuxR-type transcription regulator that is transcribed divergently from exaA. EraR also showed a positive interaction with RpoN in two-hybrid and pulldown assays.

IMPORTANCE Quinoprotein alcohol dehydrogenase (ExaA) plays an important role in the catabolism of alcohols in bacteria. Although exaA expression is thought to be regulated by a two-component system consisting of EraS and EraR, the mechanism of regulation was not known. This study shows the details of the regulation of expression of the exaA gene in A. brasilense. We have shown here that exaA of A. brasilense is maximally induced by glycerol and harbors a σ54-dependent promoter. The response regulator EraR binds to an inverted repeat located upstream of the exaA promoter. This study shows that a LuxR-type response regulator (EraR) binds upstream of the exaA gene and physically interacts with σ54. The unique feature of this regulation is that EraR is a LuxR-type transcription regulator that lacks the GAFTGA motif, a characteristic feature of the enhancer binding proteins that are known to interact with σ54 in other bacteria.

KEYWORDS: quinoprotein, alcohol dehydrogenase, transcriptional regulator, LuxR, RpoN

INTRODUCTION

Azospirillum brasilense is a nitrogen-fixing, plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium that is known to colonize the roots of a large number of nonlegume plants and promote their growth by producing phytohormones. One important reason for the rhizocompetence of A. brasilense is its ability to preferentially utilize dicarboxylates as a carbon source for growth and nitrogen fixation, as many dicarboxylates are the dominant organic compounds exuded by the roots of C4 grasses (1). Since A. brasilense is a microaerophilic bacterium, it is expected to switch from oxidative to fermentative pathways during microaerobic growth, leading to the production of alcohols. However, in comparison to other species of Azospirillum, the ability of A. brasilense to catabolize carbohydrates and alcohols is very limited (2). Although it can grow on fructose, galactose, and arabinose as a carbon source, it fails to grow on glucose, mannose, sorbose, or sucrose (2). Similarly, Azospirillum lipoferum can utilize glycerol, mannitol, and sorbitol, but A. brasilense uses only glycerol as a carbon source (3).

Although glycerol can diffuse through membranes without a transport system, bacteria metabolize glycerol by using two alternative pathways. In one pathway, glycerol is taken up via an ABC transporter, converted to glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) by a glycerol kinase, and oxidized to dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) by glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, followed by its entry into the glycolytic pathway (4, 5). In the second pathway, glycerol is oxidized to dihydroxyacetone by a glycerol dehydrogenase before being phosphorylated to DHAP by an ATP- or phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent dihydroxyacetone kinase (6). The membrane-bound PQQ-dependent glycerol dehydrogenase in Gluconobacter oxydans (7) catalyzes the oxidation of the secondary group of glycerol to dihydroxyacetone (DHA) in the periplasm (8). This enzyme is unique in having a broad substrate range, including d-sorbitol, glycerol, meso-erythritol, 2-butanol, 3-pentanol, and 2,3-butanediol, and was independently identified as d-arabitol dehydrogenase (9) and d-sorbitol dehydrogenase (10). It is a major polyol dehydrogenase which is involved in the oxidation of almost all sugar alcohols in Gluconobacter (11).

The utilization of alcohols in bacteria takes place through alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs), which oxidize alcohols to aldehydes (12) that are then converted into acetate by aldehyde dehydrogenases and eventually channeled to the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) and glyoxylate cycles via acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) (13). Although most of the ADHs are NAD(P) dependent and are present in the cytoplasm, PQQ-dependent ADHs are found mostly in the membranes or in the periplasm in a limited range of alphaproteobacteria, betaproteobacteria, and gammaproteobacteria (14). PQQ-dependent ADH was first described in Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 17933, which grows aerobically on ethanol and was shown to oxidize ethanol to acetaldehyde by a periplasmic quinoprotein ethanol dehydrogenase (QEDH) that contains PQQ as cofactor (15). QEDH transfers electrons to an endoxidase via soluble cytochrome c550 (16). Quino(hemo)protein alcohol dehydrogenases that have PQQ as a prosthetic group are classified into 3 groups. Type I ADHs are simple quinoproteins having PQQ as the only prosthetic group, whereas type II and type III ADHs are quinohemoproteins having heme c as well as PQQ in the catalytic polypeptide (14).

Although glycerol is one of the few alcohols that A. brasilense Sp7 can utilize under dicarboxylate-deficient conditions (17), very little is known about the genes, proteins, and pathways involved in its utilization and regulation in A. brasilense. In this study, we have identified a glycerol-induced quinoprotein alcohol dehydrogenase (ExaA) in A. brasilense Sp7 and investigated its role in glycerol utilization. We show here the dependence of exaA expression on σ54 and physical interaction of σ54 with a LuxR-type response regulator, which binds to an inverted repeat element located upstream of the exaA gene.

RESULTS

Identification of glycerol-inducible proteins in A. brasilense.

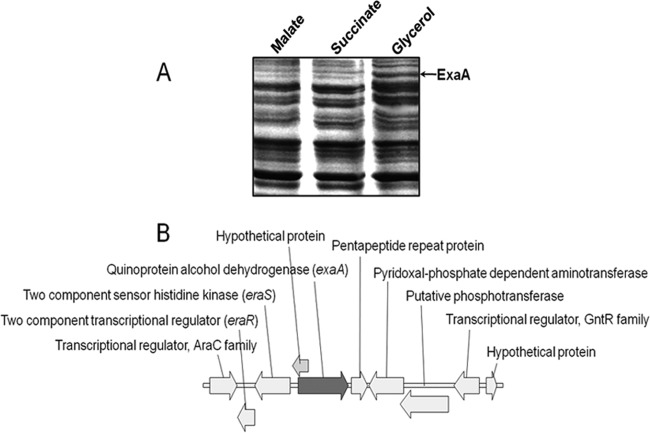

In order to identify glycerol-inducible proteins in A. brasilense Sp7, the SDS-PAGE protein profile of A. brasilense Sp7 cells grown in minimal medium containing glycerol (40 mM) as the sole carbon source was compared with that of cells grown in medium containing malate or succinate as the sole carbon source. Proteins that were differentially expressed in glycerol-grown cells vis-à-vis malate-grown cells were identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–tandem mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS/MS) and are listed in Table 1. This comparison revealed a distinctly upregulated protein in the glycerol medium, which was either absent or synthesized at a low level when A. brasilense was grown in medium containing succinate or malate as the carbon source (Fig. 1A). Analysis of the peptides of the upregulated protein revealed that the peptides matched with a PQQ-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase (ExaA) (Fig. 1B) of A. brasilense Sp7.

TABLE 1.

MALDI-MS/MS-based identification of proteins upregulated in A. brasilense Sp7 and its exaA::Km mutant after transfer to minimal medium containing glycerol as the sole carbon sourcea

| Spot no. | Locus tag | Probable protein function(s) | Mascot score(s) | Protein molecular mass (Da)/pI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1, V2 | AZOBR_p330074 | Quinoprotein alcohol dehydrogenase (ExaA) | 308, 529 | 70,022/6.52 |

| V3, V4, V5 | AZOBR_p460073 | Peptidase | 322, 103, 318 | 45,227/5.19 |

| V6 | AZOBR_p210013 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | 160 | 55,831/5.89 |

| V7, V9 | AZOBR_180211 | Quinoprotein methanol/ethanol dehydrogenase (ExaA1) | 645, 468 | 62,931/6.29 |

| V8, V10 | AZOBR_p280093 | Putative sugar ABC transporter, substrate-binding periplasmic component (GlpS) | 124, 230 | 65,055/5.8 |

| V11 | AZOBR_110079 | Branched-chain amino acid ABC transporter, substrate-binding periplasmic component | 543 | 38,982/6.37 |

| V12 | AZOBR_p440158 | Sugar ABC transporter, periplasmic binding component | 329 | 34,114/7.63 |

| V13 | AZOBR_10236 | Cysteine synthase A | 694 | 33,894/5.69 |

| V14 | AZOBR_10141 | Lysine/arginine/ornithine ABC transporter, periplasmic binding component | 329 | 29,831/6.0 |

| V15, V16, V17, V18 | AZOBR_p440163 | Sugar ABC transporter, substrate-binding component | 691, 419, 576, 298 | 38,346/5.38 |

The protein corresponding to spots V1 and V2 was upregulated in wild-type A. brasilense Sp7. Other proteins were upregulated in the exaA::Km mutant.

FIG 1.

(A) Comparison of the SDS-PAGE protein profiles of A. brasilense Sp7 grown in minimal medium containing malate, succinate, or glycerol (each 40 mM) as the sole carbon source. SDS-PAGE shows upregulation of a protein in the A. brasilense Sp7 culture grown with glycerol as the carbon source that was absent in cultures grown with C4-dicarboxylates as the carbon source. This protein was identified as quinoprotein alcohol dehydrogenase (ExaA) by MALDI-MS/MS (Table 1). (B) Genetic organization of exaA of A. brasilense Sp7 showing a divergently oriented two-component regulatory system and a pentapeptide repeat protein-encoding gene located downstream of exaA.

Bioinformatic analysis of the ExaA protein.

When we analyzed the phylogeny of the gene encoding ExaA (locus tag, AZOBR_p330074, designated exaA) of A. brasilense, it showed close relatedness to QedA of Pseudomonas putida, ExaA of P. aeruginosa, Boh of Pseudomonas butanovora, and ExaA2 of Azoarcus sp. strain BH72 (see the supplemental material at http://cimap.res.in/english/images/Director/Supplemental_Material_JB00035-17.pdf). The deduced amino acid sequence of ExaA showed good alignment and homology with ExaA proteins from P. aeruginosa (76% identity), Azoarcus (74% identity), P. butanovora (72% identity), and P. putida (69% identity). The exaA gene was organized in an orientation opposite that of the genes encoding a two-component regulatory system consisting of a sensor histidine kinase (EraS) and a LuxR-type response regulator (EraR). A gene encoding a pentapeptide repeat protein is located immediately downstream of the exaA gene (Fig. 1B). Although the A. brasilense genome revealed another copy of exaA (locus tag AZOBR_180211, encoding ExaA1) showing 55% identity with the glycerol-inducible exaA, it was not associated with regulatory genes. Hence, we focused our attention on the glycerol-inducible ExaA. The gene organization of exaA in A. brasilense is similar to that found in Azoarcus strain BH72, P. putida, and P. aeruginosa, except that the gene encoding cytochrome c550 was conspicuous by its absence in the vicinity of exaA in A. brasilense (http://cimap.res.in/english/images/Director/Supplemental_Material_JB00035-17.pdf).

Effect of different alcohols on exaA promoter activity.

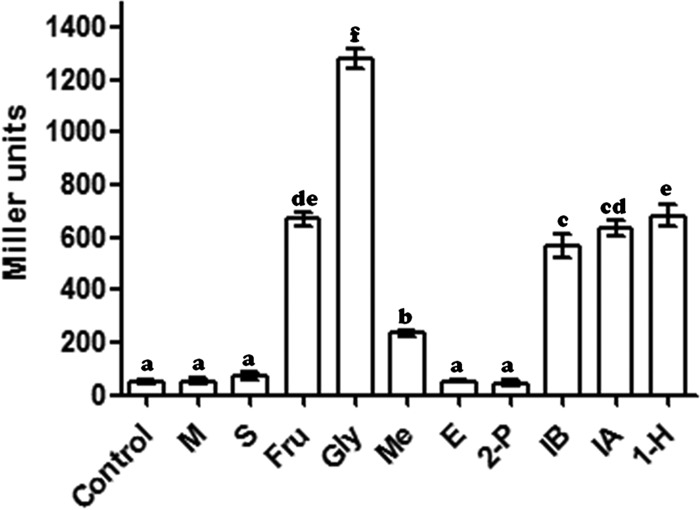

In order to examine the inducibility of the exaA promoter by different carbon sources, we monitored the β-galactosidase activity of A. brasilense harboring an exa::lacZ fusion in response to malate, succinate, fructose, glycerol, and various alcohols. Glycerol, fructose, and primary and secondary long-chain alcohols (C4 to C6) all induced exaA promoter activity significantly (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2). Glycerol caused the maximum induction of the exaA promoter, while short-chain-length alcohols (C1 to C3) showed poor induction. Besides glycerol, fructose and longer-chain-length alcohols also induced the exaA promoter significantly (P < 0.05).

FIG 2.

Promoter activity of exaA in A. brasilense Sp7 after induction by various substrates (such as 0.5% [vol/vol] alcohols or 40 mM fructose or succinate) in minimal medium. Error bars show standard deviations (SD) for triplicates of three independent experiments. Data (n = 3) were analyzed by using the SPSS17 software and were subjected to one general linear model analysis of variance (ANOVA). The differences between means were compared, and letters above the bars indicate the result of Tukey's multiple-comparison test (different letters have P values of <0.05). M, malate; S, succinate; Fru, fructose; Gly, glycerol; Me, methanol; E, ethanol; 2-P, 2-propanol; IB, isobutyl alcohol; IA, isoamyl alcohol; 1-H, 1-hexanol.

Effect of inactivation of exaA in A. brasilense.

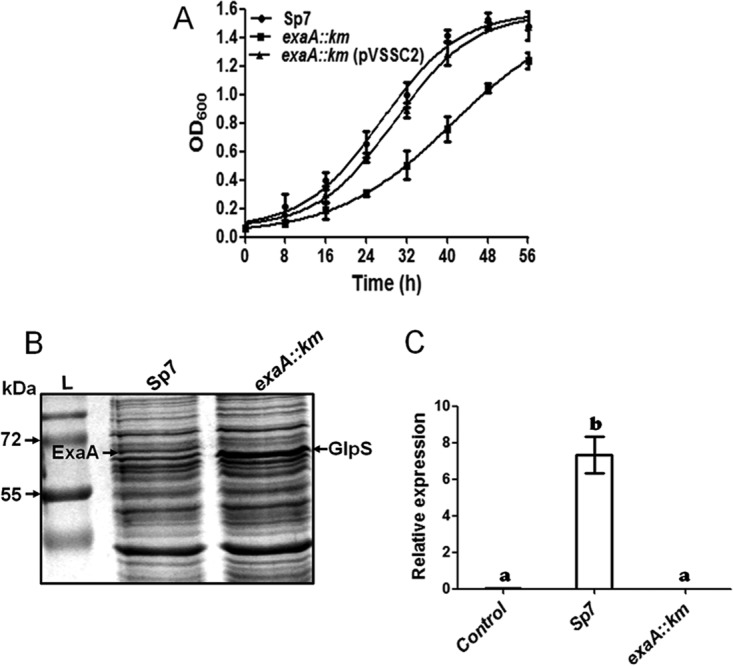

In order to study the role of exaA, we generated an exaA::Km mutant of A. brasilense by insertional inactivation of the gene. The mutant grew more slowly than the parental strain in minimal medium containing glycerol as the sole carbon source. The doubling times of the parent and the mutant were 12 h and 16 h, respectively. Complementation of the exaA::Km mutant via overexpression of exaA along with its downstream gene encoding a pentapeptide repeat protein resulted in a higher rate of growth, with a doubling time of 13.5 h (Fig. 3A). In order to ascertain if the reduced growth of the exaA::Km mutant was due to the lack of ExaA protein, we resolved the total proteins of the mutant and the parent in SDS-PAGE gels and confirmed that ExaA was not detectable in the mutant (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, an analysis of the exaA transcript levels in the exaA::Km mutant and A. brasilense Sp7 showed that exaA transcripts were not detectable in the exaA::Km mutant (Fig. 3C). However, a new protein (GlpS) was conspicuously upregulated in the mutant, and it was identified by MALDI-MS/MS as a substrate-binding periplasmic component of an ABC transporter (locus identification [ID], AZOBR_p280093). This protein is encoded within a “glycerol utilization locus” that contains six genes (glpSTPQUV) encoding a putative ABC transporter, and it is flanked by glpK (encoding glycerol kinase) and glpD (encoding glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase). A similar type of organization of a glycerol utilization locus is also found in several alphaproteobacteria, including Rhizobium leguminosarum, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Rhodopseudomonas palustris, and Roseobacter sp. (5).

FIG 3.

(A) Growth curves of A. brasilense Sp7, the exaA::Km mutant, and an exaA::Km complemented strain in glycerol (40 mM) minimal medium. Each point of the curve is the mean of triplicates for three independent experiments, and error bars show standard deviation (SD) at each point of growth. (B) SDS-PAGE of total proteins extracted from A. brasilense Sp7 and the exaA::Km mutant grown in medium supplemented with glycerol (40 mM) as the sole source of carbon. The exaA::Km mutant shows upregulation of GlpS protein and reduced expression of ExaA protein. Lane L, molecular mass markers. (C) Relative expression and transcript analysis of the exaA gene in A. brasilense Sp7 and the exaA::Km mutant grown in glycerol-supplemented minimal medium, as determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR). A zero transcript level was observed in the exaA::Km mutant. The mRNA level for rpoD was used as an internal standard for normalization. Error bars show SD of triplicates from three independent experiments, and differences between means were compared. Letters above the bars indicate the result of Tukey's multiple-comparison test (different letters have P values of <0.05).

Identification of proteins upregulated in the exaA::Km mutant.

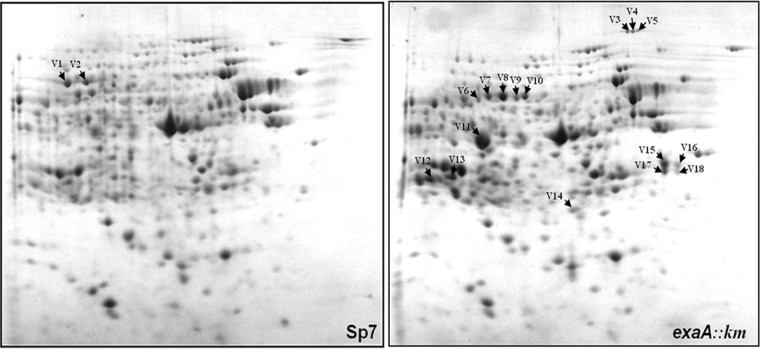

Since SDS-PAGE analysis of the total proteins of the exaA::Km mutant revealed upregulation of a periplasmic protein that was a component of an ABC transporter, we analyzed the differences in the proteomes of the exaA::Km mutant and A. brasilense Sp7 grown in minimal medium with glycerol as the sole carbon source. The differentially expressed proteins (in A. brasilense Sp7 versus the exaA::Km mutant) were identified by MALDI-MS/MS (Fig. 4 and Table 1). Table 1 shows that aside from the absence of the ExaA protein and the upregulation of GlpS, the exaA::Km mutant had several other proteins that were upregulated, including the second quinoprotein alcohol dehydrogenase (AZOBR_180211) and the periplasmic component of several ABC transporters of sugars and amino acids (Table 1).

FIG 4.

Comparison of the proteomes of A. brasilense Sp7 and the exaA::Km mutant grown in minimal medium containing glycerol (40 mM) as the sole carbon source. The 2D gel pictures show the presence of ExaA protein as V1 and V2 spots in A. brasilense Sp7 and its absence in the exaA::Km mutant. Several other proteins were upregulated in the exaA::Km mutant, which were identified as periplasmic components of several different ABC transporters and another copy of quinoprotein ethanol/methanol dehydrogenase (ExaA1).

Identification of promoter elements of exaA.

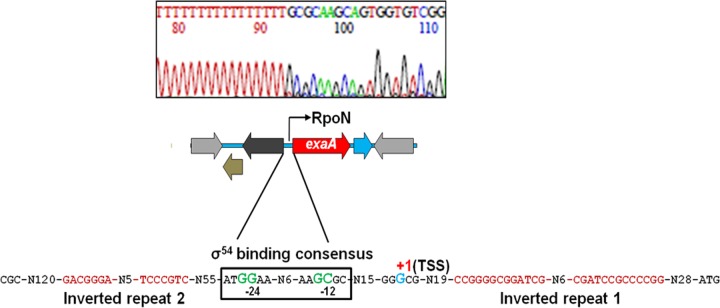

In order to locate the promoter of exaA, we performed 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′ RACE) to identify the transcription start site (TSS). Sequencing of the cDNA after 5′ RACE indicated a G that was located 81 nucleotides (nt) upstream of the start codon ATG (Fig. 5). A search for a promoter sequence in the region upstream of the TSS identified GG and GC elements with a 10-nucleotide spacing, found in typical −24/−12 type RpoN (σ54)-dependent promoters. Although the −12 GC element is usually located 11 to 13 nucleotides upstream of the TSS (18), we found that the −12 GC element in the exaA promoter was located 19 nucleotides upstream of the TSS. The longest known distance between the TSS and the GC element is 21 nucleotides (19).

FIG 5.

Determination of the transcription start site (TSS) of exaA by 5′ RACE. The electropherogram depicting the TSS of exaA is representative of results from sequencing of multiple clones obtained after the 5′-RACE experiment. The genetic organization of the RpoN-dependent promoter showing two inverted repeats (IRs) upstream and downstream of the promoter is presented. The TSS is indicated by +1, and the associated promoter region is boxed.

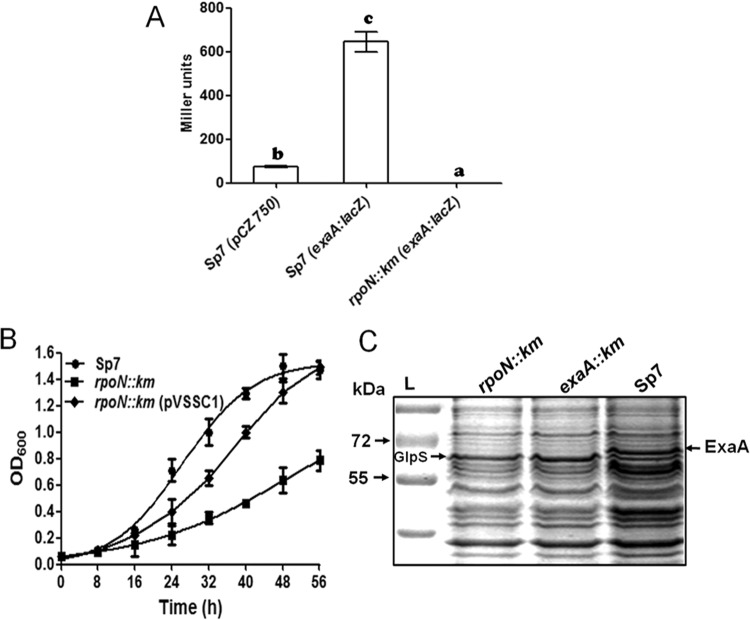

Regulation of expression of exaA by σ54.

Since the −12 GC element of the predicted σ54-dependent promoter consensus of exaA was located at an unusual distance of 19 nucleotides from the TSS, we validated the σ54 dependence of the exaA promoter by fusing the exaA upstream region with the promoterless lacZ reporter in a broad-host-range vector, and we also constructed an rpoN::Km mutant in A. brasilense Sp7. The exaA::lacZ fusion was then mobilized into A. brasilense Sp7 and its rpoN::Km mutant to compare β-galactosidase activity. Although there was significant expression of the exaA::lacZ fusion in A. brasilense Sp7, the rpoN::Km mutant did not show any detectable expression (Fig. 6A), clearly indicating that exaA expression was RpoN dependent. It also showed that the exaA upstream region contained a σ54-dependent promoter. When we compared the growth of the rpoN::Km mutant with that of A. brasilense Sp7 in the medium containing glycerol as a sole carbon source, the growth of the rpoN::Km mutant was considerably slower (Fig. 6B). While A. brasilense Sp7 attained an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.3 in 40 h, the rpoN::Km mutant could reach an OD600 of only 0.4 in the same duration. After complementation of the rpoN::Km mutant by overexpressing rpoN and its downstream gene (encoding a putative sigma-modulating protein), the growth rate increased, with the complemented strain reaching an OD600 of 1 in 40 h. In order to ascertain whether the rpoN::Km mutant failed to express exaA, we compared the protein profile of the rpoN::Km mutant with those of the exaA::Km mutant and A. brasilense Sp7 by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 6C), followed by identification of the differentially expressed proteins by MALDI-MS/MS. This analysis revealed that the exaA::Km and rpoN::Km mutants lacked expression of the ExaA protein, corroborating the dependence of exaA expression on σ54.

FIG 6.

(A) Bar graph showing the promoter activity of the exaA gene in A. brasilense Sp7 and its rpoN::Km mutant. β-Galactosidase activities were assayed with samples taken from three independent cultures in triplicate after 3 h of growth in minimal medium containing glycerol (40 mM) as the carbon source. Means ± SD for triplicates from three independent experiments are indicated, and differences between means were compared. Letters above the bars indicate the result of Tukey's multiple-comparison test (different letters have P values of <0.05). (B) Growth curves of A. brasilense Sp7, the rpoN::Km mutant, and the rpoN::Km complemented strain in glycerol (40 mM) minimal medium. Each point of the curve represents the mean of triplicates from three independent experiments, and the error bar at each point shows SD. (C) SDS-PAGE showing induction of ExaA protein in A. brasilense Sp7 and its absence in the exaA::Km and rpoN::Km mutants, grown in minimal glycerol (40 mM) medium. Mutants also show an upregulation of GlpS protein. Lane L, molecular mass markers. Arrows indicate induced ExaA and GlpS proteins.

Role of inverted repeats flanking the RpoN-dependent promoter in regulation of expression of exaA.

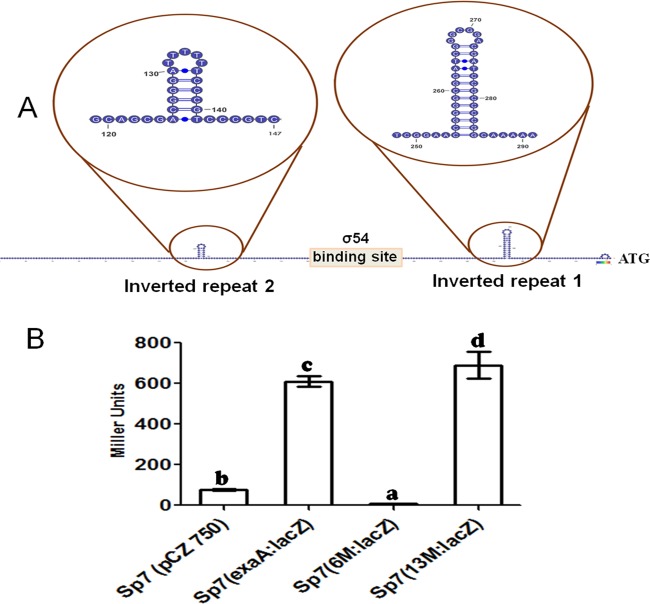

To identify and characterize the roles of other possible cis-acting elements in the vicinity of the −12/−24 promoter, we examined the exaA upstream region for the occurrence of inverted repeat sequences, which are often the sites for binding of transcription regulators. We identified one inverted repeat both upstream and downstream of the −12/−24 promoter. The first inverted repeat (IR1), with a strong stem-loop structure (CCGGGGCGGATCG-N6-CGATCCGCCCCGGC) and dyad symmetry with a 13-nucleotide-long GC-rich arm on each side of the loop, was located downstream of the −12/−24 promoter and 28 nucleotides upstream of the start codon of exaA. The second inverted repeat (IR2), containing a 17-bp sequence motif with dyad symmetry (ACGGGATTTTTTCCCGT, where the two arms of the dyad are in bold) and 6-nucleotide-long arms, was located 59 nt upstream of the −12/−24 promoter (Fig. 7A). In order to assess the importance of each of these inverted repeats, we constructed two exaA::lacZ fusion derivatives: one with a disruption of the IR1 (13M::lacZ) and the second with a disruption of IR2 (6M::lacZ). When we compared the β-galactosidase activities from these two derivatives vis-à-vis the unmutated exaA::lacZ fusion, we found that the disruption of IR2 had a drastic adverse effect on exaA promoter activity in A. brasilense Sp7 whereas the disruption of IR1 did not show any significant effect (Fig. 7B).

FIG 7.

(A) Promoter region of exaA showing the presence of two highly stable inverted repeats, 2 and 1, present upstream and downstream of the RpoN-binding site, respectively. (B) Bar graph showing the activities of the exaA promoter and mutant promoters (6M and 13M for IR2 and IR1, respectively) in wild-type A. brasilense. β-Galactosidase activities were assayed with triplicates of 40 mM glycerol-grown cultures for 3 h. A drastic adverse effect was observed on the activity of the exaA promoter after IR2 mutation. Error bars show SD of triplicates from three independent experiments, and differences between means were compared. Letters above the bars indicate the result of Tukey's multiple-comparison test (different letters have P values of <0.05).

Binding of EraR protein to IR2 in the exaA upstream region.

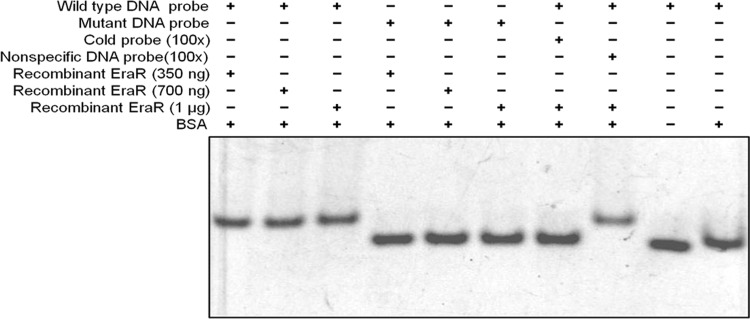

Since the disruption of IR2 had a negative effect on the expression of exaA, we inferred that IR2 might be the binding site for a positive regulator of exaA transcription. Due to the considerable similarity of IR2 to the EraR-binding site of P. aeruginosa (20), we used an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) to examine the ability of the recombinant EraR protein of A. brasilense Sp7 to bind to the exaA upstream region harboring IR2. Two 5′-6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-labeled probes, a wild-type probe of the promoter region containing IR2 and a mutant probe (in which IR2 was disrupted by replacing complementary sequences with similar sequences), were incubated with increasing amounts of fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC)-purified 6×His-tagged EraR protein (350 ng, 700 ng, and 1 μg) in a binding buffer. A 5′-FAM-labeled wild probe with competitors (cold probe and nonspecific DNA from another region of the promoter) was also incubated as a control with purified EraR (1 μg) protein. The EraR protein retarded the mobility of the probe containing wild-type IR2 at all three concentrations used but failed to retard the mobility of the probe having disrupted IR2. Prior incubation of the protein with cold wild probe failed to retard the mobility of the FAM-labeled probe, while a similar retardation in mobility was observed when the EraR protein was preincubated with nonspecific DNA from the other region of the promoter (Fig. 8). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) and other buffer constituents did not show any mobility shift with the native probe. This result clearly indicated that IR2 is the binding site for the regulator EraR.

FIG 8.

EMSA depicting binding of recombinant EraR protein with FAM-labeled DNA probes of inverted repeat 2 (IR2) present upstream of the exaA promoter. Binding components are indicated. No binding of EraR protein was noticed with the mutated IR2 and nonspecific DNA probes. BSA did not bind to the DNA probe.

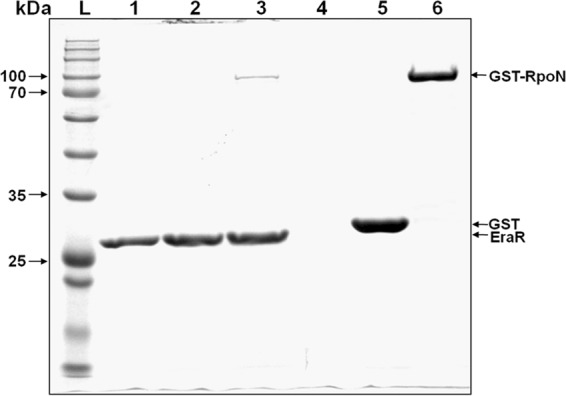

Interaction of EraR response regulator with σ54.

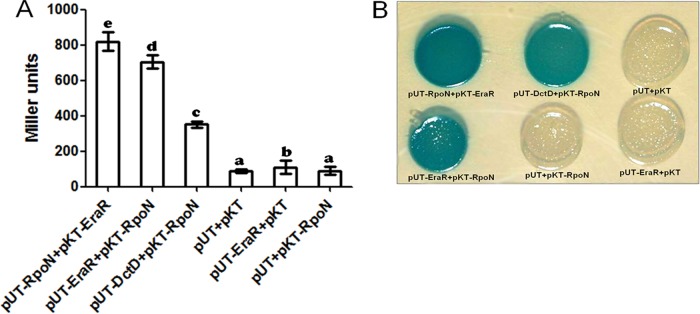

The results obtained so far indicated that the exaA upstream region harbored a σ54-dependent promoter and an inverted repeat, which is a binding site for the EraR regulator. In order to know whether the σ54 protein physically interacts with the EraR protein, we used an Escherichia coli two-hybrid assay (bacterial two-hybrid [BACTH] system) in which protein-protein interaction was determined by the reconstitution of adenylate cyclase subdomains T18 and T25 to the functional holoenzyme (21). When eraR (cloned in pKT25 or pUT18), rpoN (cloned in pKT25 or pUT18), or dctD (cloned in pUT18) was expressed individually in E. coli BTH101 cells, none showed any β-galactosidase activity. When DctD (a well-known bacterial enhancer binding protein [bEBP]) was coexpressed with RpoN, it showed a positive interaction. Coexpression of EraR and RpoN, whether from pKT25 and pUT18 or vice versa, also showed the same level of interaction in terms of β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 9A) and on a 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) plus isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) plate (Fig. 9B), indicating a positive protein-protein interaction between EraR and σ54. We further confirmed this interaction by a pulldown assay in which EraR was fused to a hexahistidine tag, whereas σ54 was fused to a glutathione S-transferase (GST) tag. When the 6×His-tagged EraR protein, which was bound to nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin, was allowed to interact with GST or GST-fused RpoN in the binding buffer, eluted in the cracking buffer by washing the resin with washing buffer, and resolved in a 12% SDS-PAGE gel, we recovered two proteins: a 6×His-tagged EraR and a GST-tagged σ54 (Fig. 10). The GST protein, however, was not pulled down by the 6×His-tagged EraR protein. This observation reconfirmed that EraR interacts with σ54. The purities of GST, GST-fused RpoN, and EraR were confirmed by Western blotting (see the supplemental material at http://cimap.res.in/english/images/Director/Supplemental_Material_JB00035-17.pdf) and MALDI-MS/MS.

FIG 9.

(A) Protein-protein interaction between EraR and RpoN as determined with a bacterial two-hybrid system (BACTH). E. coli BTH101 was cotransformed with plasmid pairs, such as pUT/pKT, pUT-EraR/pKT, pUT/pKT-RpoN, pUT-EraR/pKT-RpoN, pUT-RpoN/pKT-EraR, and pUT-DctD/pKT-RpoN. A β-galactosidase assay was performed on overnight cultures grown in the presence of 0.5 mM IPTG. pUT/pKT, pUT-EraR/pKT, and pUT/pKT-RpoN plasmid pairs were used as a negative control. Means ± SD for triplicates from three independent experiments were measured, and differences between means were compared. Letters above the bars indicate the result of Tukey's multiple-comparison test (different letters have P values of <0.05). (B) The interactions between EraR and RpoN are shown qualitatively on X-Gal-plus-IPTG plates.

FIG 10.

Pulldown assay showing protein-protein interaction between RpoN and EraR. SDS-PAGE (12%) gel depicting the pulldown of GST-tagged RpoN (∼600 pmol) as prey using 6×His-tagged EraR (∼200 pmol) as bait with Ni-NTA beads. Lane 1, 6×His-tagged EraR (100 pmol); lane 2, 6×His-tagged EraR (200 pmol) plus GST (600 pmol); lane 3, 6×His-tagged EraR (200 pmol) plus GST-tagged RpoN (600 pmol); lane 4, Ni-NTA beads only; lane 5, purified GST only (1,000 pmol); lane 6, purified GST-tagged RpoN only (600 pmol); lane L, molecular mass markers.

DISCUSSION

In an attempt to identify proteins that are involved in glycerol utilization in A. brasilense Sp7, we identified a periplasmic quinoprotein alcohol dehydrogenase (ExaA), which was expressed in cultures grown with glycerol as the sole carbon source but absent in cultures grown with malate or succinate as the carbon source. Inactivation of the gene encoding ExaA reduced the growth of A. brasilense Sp7 on glycerol but did not completely abolish it. The slow growth of an exaA::Km mutant, in comparison to that of its parent, in the glycerol-containing medium suggests that inactivation of exaA in A. brasilense blocks the energy-efficient pathway of glycerol utilization. A comparison of the proteome of the exaA::Km mutant with that of its parent revealed an upregulation of several periplasmic proteins, which were components of ABC-type high-affinity transporters of sugars and amino acids. Since glycerol is a relatively poor source of carbon for A. brasilense, inactivation of exaA will further reduce the availability of energy required for cellular functions due to the adoption of a less-energy-efficient glycerol utilization pathway. Hence, under a situation of such distress, the cell might be expected to upregulate the expression of high-affinity transporters that could help in scavenging micromolar concentrations of alternative sources of carbon (22).

Genomes of alcohol-utilizing bacteria often encode more than one alcohol dehydrogenase. Because of their broad substrate range, quinoprotein alcohol dehydrogenases (such as ExaA) seem to confer environmental fitness to the host bacteria, as the expression of this enzyme is induced by multiple inducers and enables survival on various substrates (14). PQQ-dependent glycerol dehydrogenases of P. aeruginosa (23) and Gluconobacter suboxydans degrade a wide range of substrates, including both primary and secondary alcohols (11). P. butanovora, an n-alkane-degrading bacterium, harbors a quinoprotein ADH (BOH), which enables growth on 1-butanol, 2-butanol, 2-propanol, 2 pentanol, and butyraldehyde, and the gene encoding BOH is induced by a broad range of alcohols. The occurrence of two ExaA genes in the A. brasilense genome was intriguing, as A. brasilense does not utilize alcohols other than glycerol. However, exaA of A. brasilense is also induced by a broad range of compounds in the absence of dicarboxylates and facilitates growth on alternative carbon sources, including glycerol and fructose. While P. putida HK5 expresses three different ExaA proteins upon exposure to alcohols (24), Azoarcus sp. strain BH72 harbors 5 copies of ADHs, of which ExaA1 and ExaA2 were quinohemoproteins, whereas ExaA2, ExaA3, and ExaA5 were quinoproteins (25). ExaA2 and ExaA3 were the main ADHs involved in the oxidation of ethanol, as both were induced by ethanol, and their disruption resulted in reduced growth on ethanol (25).

An analysis of the genome of A. brasilense revealed that it encodes two pathways of glycerol utilization: a phosphotransferase system (PTS)-dependent dihydroxyacetone (DHA) kinase pathway (comprising DhaL [AZOBR_p220044] and DhaK [AZOBR_p220044]) and a pathway consisting of glycerol-specific ABC transporter components, glycerol kinase (AZOBR_p280095), and glycerol-3P-dehydrogenase (AZOBR_p280087). Hence, it can be hypothesized that in A. brasilense, the periplasmically located ExaA transforms glycerol into DHA, which in turn is converted into DHA phosphate by a DHA kinase before being transported to the cytoplasm via a membrane-bound DHA phosphotransferase system (26). Upregulation of the periplasmic component of an ABC transporter gene of the glycerol utilization locus in the exaA::Km mutant indicates that glycerol, after its conversion to DHA, is preferentially transported via an ATP-independent PTS (26). Upon inactivation of exaA, glycerol might be transported via an ATP-dependent ABC transporter and then phosphorylated to glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) by a glycerol kinase (5). G3P would then get oxidized by glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase to DHAP in the cytoplasm. Since the pathway involving glycerol kinase and glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase requires more energy for the conversion of glycerol into DHAP, it is expected to be a less-energy-efficient pathway for glycerol utilization. Thus, ExaA is part of an energy-efficient pathway for glycerol utilization in A. brasilense.

In P. aeruginosa, ethanol oxidation is controlled by a complex regulatory network which consists of three cytoplasmically located sensor kinases and three LuxR family response regulators (27). The response regulator ErbR (AgmR) controls the transcription of operons exaBC, pqqABCDE, and eraSR (28). EraSR constitutes a two-component system with a sensor kinase and a response regulator to control the transcription of the exaA gene (20, 28). The details of the regulation of exaA expression by LuxR-type regulators, however, were not elucidated (29). Although the occurrence of a σ54-dependent promoter consensus was shown upstream of boh in P. butanovora, qgdA of P. putida (27), the two LuxR-regulated genes, and the qrr4 gene in Vibrio harveyi (30), none of them were experimentally shown to be regulated by σ54. In this study, after identifying a putative σ54-dependent promoter upstream of the TSS of exaA, we established the dependence of the exaA promoter on σ54. The σ54-dependent promoters are usually activated by bacterial enhancer binding proteins (bEBPs) that bind upstream of the promoter and interact through their highly conserved GAFTGA domains with σ54 in the σ54-core enzyme complex bound to the promoter (20, 31). Related proteins that lack the GAFTGA signature motif have not been shown to activate transcription at σ54-dependent promoters (32). In this study, we have shown for the first time to our knowledge that the EraR response regulator, which is devoid of a GAFTGA domain, is involved in regulating the expression of exaA and that it binds to an inverted repeat in the exaA upstream region and physically interacts with σ54. A comparison of the deduced amino acid sequence of ExaR of A. brasilense with that of ExaE of P. aeruginosa and with NtrC and DctD of A. brasilense revealed that ExaR and ExaE were homologous and different from NtrC and DctD (see the supplemental material at http://cimap.res.in/english/images/Director/Supplemental_Material_JB00035-17.pdf), which harbor the GAFTGA domain characteristic of the bacterial enhancer binding proteins.

Regulation of σ54 dependent promoters by DNA binding proteins other than bEBPs has been demonstrated earlier, but none were shown to physically interact with σ54. The nucleoid binding protein Fis was shown to bind to a site at −55 relative to the start of transcription of glnA in E. coli to activate the expression of the σ54-dependent promoter glnAp2 by inducing bending of the intervening DNA (33). Similarly, in the case of the TOL plasmid of Pseudomonas putida, integration host factors (IHF) were shown to bind at positions −53 to −79 to induce DNA bending to stimulate recruitment of σ54 at the σ54-dependent Pu promoter for interaction with an upstream-bound bEBP, XylR. These results indicated that the binding of σ54-RNA polymerase (RNAP) to a promoter can be subjected to regulation by factors other than the intrinsic affinity of σ54-RNAP for the −12/−24 site (34). Furthermore, cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP), which is not related to σ54 activators, was shown to repress the activation of the σ54-dependent promoter of dctA by its ability to compete with DctD (a bEBP) for binding at the DctD-binding sites located upstream of the dctA promoter (35). In light of these observations, it appears that EraR might be an atypical EBP which lacks the typical GAFTGA domain or that it might be a protein that helps an unknown bEBP to activate the expression of the σ54-dependent exaA promoter in A. brasilense. Whether EraR itself is a bEBP which contacts σ54 in the holoenzyme bound to the promoter to isomerize a closed complex into an open complex or is an auxiliary activator of an unknown bEBP remains to be elucidated.

The occurrence of a 17-bp sequence motif with dyad symmetry (ACGGGATTTTTTCCCGT; bold letters indicate dyads) located 58 nt upstream of the −12/−24 promoter of exaA in A. brasilense was very similar to a 23-bp sequence (CGTCCGGGAA-N3-TTCCCGGACG) suggested to be a binding motif for EraR in P. aeruginosa (20). This was a prima facie indication that the 17-bp inverted repeat might be a binding site for EraR in A. brasilense Sp7. A drastic negative effect on the expression of exaA by the disruption of this secondary structure clearly indicated that this sequence might be the site for the binding of the positive regulator. Using an electrophoretic mobility shift assay, we have shown that the purified EraR protein retarded the mobility of a DNA fragment harboring IR2 (ACGGGATTTTTTCCCGT) but failed to retard a similar sequence that lacked the dyad symmetry of the IR2. These observations clearly indicated that CAGCGACGGGA-N5-TCCCGTCCCGT was the binding site for EraR, which positively regulated the expression of exaA.

EraR belongs to the TetR protein superfamily of repressors, which have conserved helix-turn-helix DNA binding domains to recognize and bind to the DNA operator sequences possessing dyad symmetry (36). Typically, the expression of genes under the control of TetR-type repressors is activated when a TetR-type repressor binds to its ligand and is released from the DNA. In some cases, TetR proteins were shown to activate gene expression, but the mechanism to explain this was not described (8, 20, 32). In this study, we have described some unknown features of the regulation of expression of exaA. Unlike most TetR-type repressors, EraR is a positive regulator of the expression of exaA in A. brasilense. On the basis of the results obtained in this study, the exaA promoter is activated by EraR and σ54. Since exaA is expressed in the absence of dicarboxylates and in the presence of glycerol, it can be hypothesized that the levels of dicarboxylates in the cell regulate the binding affinity of EraR for IR2. In the absence of dicarboxylates in the medium, EraR might bind to the IR2 to interact with the σ54 to activate transcription by the σ54-core enzyme complex bound to the −12/−24 promoter. In the presence of dicarboxylates, however, the affinity of EraR for IR2 might not cause repression of exaA. Further investigation is needed to understand this reverse catabolite repression in A. brasilense. Does EraR, which activates the transcription of exaA, become inactivated by its interaction with dicarboxylates, or does the sensor protein EraS sense the levels of dicarboxylates to bring about a posttranslational modification of EraR?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, culture conditions, and chemicals.

A. brasilense Sp7 was maintained in minimal malate medium at 30°C. For experiments, Azospirillum was grown in minimal glycerol medium containing glycerol (40 mM) as the sole source of carbon. E. coli strains DH5α, S.17-1, and BL21(DE3)pLysS were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C. E. coli BTH101 was grown in LB medium at 30°C. The plasmids used in this study are described in Table 2. All chemicals used for growing bacteria were purchased from Merck (Germany) or HiMedia (India). Restriction enzymes, DNase, RNase, Taq polymerase, and alkaline phosphatase were purchased from New England BioLabs. A first-strand cDNA synthesis kit was purchased from Fermentas. A 5′ RACE kit was purchased from Roche Life Science (USA). The bar graphs were prepared using the GraphPad Prism software.

TABLE 2.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant property(ies)a | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | ΔlacU169 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thiL relA1 | Gibco/BRL |

| E. coli S.17-1 | Smr recA thi pro hsdR RP4-2(Tc::Mu Km::Tn7) | 49 |

| E. coli BL21λ(DE3)pLysS | ompT hsdS(rB− mB−) dcm+ endA galλ (DE3) | Novagen |

| E. coli BTH101 | F− cya-99 araD139 galE15 galK16 rpsL1 (Strr) hsdR2 mcrA1 mcrB1 | Euromedex |

| A. brasilense Sp7 | Wild-type strain (ATCC 29729) | 50 |

| exaA::Km mutant | A. brasilense Sp7 exaA gene disrupted by insertion of Kmr cassette | This work |

| rpoN::Km mutant | A. brasilense Sp7 rpoN gene disrupted by insertion of Kmr cassette | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCZ750 | pFAJ1700 containing the KpnI-AscI lacZ gene from pCZ367 plasmid; Tcr Ampr | 41 |

| pVSS1 | pCZ750 derivative; exaA::lacZ Tetr Ampr | This work |

| pAPDM7 | pCZ750 derivative; 7M::lacZ mutant of palindrome 2; Tcr Ampr | This work |

| pAPDM13 | pCZ750 derivative; 13M::lacZ mutant of palindrome 1; Tcr Ampr | This work |

| pET28a | Expression vector; Ampr with T7 promoter | Novagen |

| pVSS2 | eraR (AZOBR_p330071; 659 bp) cloned at BamHI and HindIII sites of pET28a vector | This work |

| pGEX-2TK | Expression vector; Ampr | GE Healthcare |

| pVSS3 | rpoN (1,644 bp) cloned at BamHI and EcoRI sites of pGEX-2TK vector | This work |

| pUT18C | pUT18 derived from vector pUC19; Ampr; encodes the T18 fragment (amino acids 225 to 399 of CyaA) with lac promoter; expresses chimeric proteins | Euromedex |

| pVSS4 | eraR gene (659 bp) cloned at XbaI and EcoRI sites of pUT18C vector | This work |

| pVSS5 | rpoN gene (1,575 bp) cloned at XbaI and EcoRI sites of pUT18C vector | This work |

| pVSS6 | dctD gene (1,377 bp) cloned at XbaI and EcoRI sites of pUT18C vector | This work |

| pKT25 | Encodes T25 fragment (corresponding to first 224 amino acids of CyaA) with lac promoter; derived from low-copy-no. plasmid pSU40; Kmr; expresses chimeric proteins | Euromedex |

| pVSS7 | rpoN gene (1,575 bp) cloned at XbaI and EcoRI sites of pKT25 vector | This work |

| pVSS8 | eraR gene (659 bp) cloned at XbaI and EcoRI sites of pKT25 vector | This work |

| pSUP202 | ColE1 replicon, mobilizable plasmid, suicide vector suitable for A. brasilense; Ampr Tcr Cmr | 49 |

| pUC4K | Vector containing Kmr cassette | GE Healthcare |

| pGEM-T Easy vector | TA cloning vector | Promega |

| pVSSD1 | rpoN (AZOBR_p1110045) gene disruption plasmid | This work |

| pVSSD2 | exaA (AZOBR_p330074) gene disruption plasmid | This work |

| pMMB 206 | Cmr, broad-host-range low-copy-no. expression vector | 42 |

| pVSSC1 | rpoN (1,575 bp) and downstream gene encoding σ54 modulation protein (594 bp), both from A. brasilense Sp7, cloned into EcoRI and HindIII restriction sites of pMMB206 | This work |

| pVSSC2 | exaA (1,964 bp) and downstream gene (encoding a pentapeptide repeat protein) cloned into BamHI and HindIII restriction sites of pMMB206 | This work |

Smr, spectinomycin resistance; Strr, streptomycin resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Tcr, tetracycline resistance; Ampr, ampicillin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance.

Bioinformatic analyses.

The amino acid sequences of ExaA and ExaA1 of A. brasilense Sp7 were retrieved from the Genoscope database (https://www.genoscope.cns.fr/agc/microscope/mage/viewer.php), and similar sequences from other bacteria for which the exaA gene was described were retrieved from the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Levels of sequence identity and similarity were calculated using a multiple-sequence alignment tool obtained from the EBI server (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/). The deduced amino acid sequences of EraR (AZOBR_p330071), NtrC (AZOBR_p110010), and DctD (AZOBR_p1140109) of A. brasilense Sp7 were aligned with that of ExaE of P. aeruginosa (GenBank accession no. WP_004349494) to determine the phylogenetic relationships among them. The alignment was used for making a dendrogram with the help of the MEGA 5.05 software using 1,000 bootstrap replications and the Pearson model. Genetic organization was constructed using the Vector NTI software (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Insertional inactivation of exaA and rpoN in A. brasilense Sp7.

For construction of the exaA::Km and rpoN::Km mutants, primers (Table 3) were designed to amplify each gene along with its flanking regions in two amplicons. Amplicon A included a part (∼200 to 400 bp) of the 5′ region of the gene along with its upstream flanking region containing EcoRI and BglII restriction sites at the two ends, and amplicon B included part of the 3′ region (∼200 to 400 bp) of the gene with its downstream flanking region containing BglII and PstI restriction sites at the ends. Amplicons A and B were amplified using sets of primers (QKAF/QKAR and QKBF/QKBR, and KRF1/KRR1 and KRF2/KRR2, respectively). The two amplicons were first cloned in pGEM-T Easy vector and then excised via digestion with EcoRI and BglIII and with BglIII and PstI, respectively. The two excised fragments were then cloned in a suicide vector, pSUP202, in a three-fragment ligation. A kanamycin resistance (Kmr) gene cassette, derived from pUC4K after digestion with BamHI, was ligated to a BglII-linearized pSUP202 construct (pSUP202 with amplicons A and B). The final constructs harboring the exaA::Km (pVSSD2) and rpoN::Km (pVSSD1) inserts (Table 2) were conjugatively mobilized into A. brasilense Sp7 using E. coli S17.1 as the donor. The exconjugants were selected on minimal malate plates supplemented with kanamycin. Site-specific insertion of the Kmr cassette in the exconjugants was confirmed by gene-specific amplification using two sets of primers, PMBQF/PMBQR and PMBRPNF/PMBRPNR (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequencea (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| ExaAF | CCCAAGCTTACAGCGATGCCGAGATCAAG |

| ExaAR | GCTCTAGACGTGAAAGGCCGTTTTTTCCGGCTCTAGACGTGAAAGGCCGTTTTTTCCG |

| PF | CCCAAGCTTCGCCGTCTGATCCTTCCG |

| PR | GCTCTAGAGCGTTTCCCCCGTGAAAG |

| 7DF | GACGGGACCGTCCGGGATGTCATC |

| 7DR | CCGGACGGTCCCGTCAAAAATCCCGTCGCTGCGG |

| 13DF | GCGTTTCCCCCGTGAAAGGCCGTTTTTGCCGGGGCGGATCGTCCGCCCCGGGGCGGATCG |

| 13DR | TCCGCCCCGGGGCGGATCGTTCCGACACCACTGCTTG |

| pET28QF | CGGGATCCATGACCTTGACCATCCTCCT |

| pET28QR | CCCAAGCTTCATTTCTCACGCGATTTCAAGAC |

| pGeXRPNF | CGGGATCCGCCTCTAGTGCGGTTTCCCTG |

| pGeXRPNR | CCGGAATTCGCTGTCAATCAAGGACGACCC |

| PUTQF | TGCTCTAGAGATGACCTTGACCATCCTCCT |

| PUTQR | CGGAATTCCATTTCTCACGCGATTTCAAGAC |

| PUTDCTDF | TGCTCTAGAGATGACGACCGGCAGCATCG |

| PUTDCTDR | CGGAATTCTCACTCCACGAAATCCTCG |

| PKTRPNF | GCTCTAGACCTGCCCATGGCGCTCAGC |

| PKTRPNR | CGGAATTCCGCTGTCAATCAAGGACGACCC |

| KRF1 | AACTGCAGCGACCTGCTTCTACATGATCAC |

| KRR1 | GAAGATCTCAGGGAAACCGCACTAGAGG |

| KRF2 | GAAGATCTTCCAAGATGTCACGCATGTAAC |

| KRR2 | CGGAATTCCAGAAGGACGTCGAAGATCG |

| PMBRPNF | CGGAATTCCATGGCGCTCAGCCAACGCCTTG |

| PMBRPNR | CCCAAGCTTTCAGGCGCCGGCCTTCTCCGCC |

| QKAF | AACTGCAGCAGCTCGTCGTGGATTTCGC |

| QKAR | GAAGATCTGAGGAATCCGGCAACCACC |

| QKBF | GAAGATCTCTCCGGCATCATCTCCTCC |

| QKBR | CGGAATTCAGCGGCAATCGGTCATCAGC |

| PMBQF | CGGGATCCATGACTTTATCCTTGGACACCC |

| PMBQR | CCCAAGCTTTCACTTGGTGGTGGTCACTCG |

| QGSP1 | CATACATCAGCACGTCGC |

| QGSP2 | TGTCGTCCCAGGTGACATCG |

| QGSP3 | CGGTGGAGGCGAGGAATCCG |

| QRTF | AAGAAGTTCGCCGATCACAAGG |

| QRTR | CGCATCCAGATCTCGTCGCC |

| Oligo(dT) anchor primer | GACCACGCGTATCGATGTCGACTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTV |

| PCR anchor primer | GACCACGCGTATCGATGTCGAC |

| CompFDNA | CCGTCCGGGATGTCATCACACGCCCCTTGCCAGAGTTTCGTCCC |

| CompCDNA | GGCAGGCCCTACAGTAGTGTGCGGGGAACGGTCTCAAAGCAGGG |

Underlining indicates restriction enzyme recognition sites.

Proteome analysis by SDS-PAGE and two-dimensional gel electrophoresis.

To study the expression profile of A. brasilense Sp7 in minimal medium containing different carbon sources, an overnight culture grown in LB medium was pelleted by centrifugation, washed, and reinoculated in 30 ml of minimal medium containing malate, succinate, and glycerol (40 mM) as the sole source of carbon, up to an OD600 of 0.04. Bacteria were grown at 30°C with shaking at 180 rpm in an incubator shaker. After 30 h of growth (OD600, ≈1), cells were harvested by centrifugation. One-tenth of the pellet was lysed, and ∼40 μg of protein sample was resolved by 12% SDS-PAGE. Protein bands showing upregulation were cut from the gel, and after in-gel digestion with trypsin, they were analyzed by MALDI-MS/MS. The peptide mass list obtained from the analyzer (Bruker) was used for a Mascot search against the NCBI database.

To study the expression profiles of wild-type and exaA::Km mutant strains by two-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis, overnight-grown cultures were reinoculated into medium containing glycerol (40 mM each) as the sole carbon source. Mid-log-phase cells were harvested by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm and 4°C for 5 min. The procedure for protein isolation and 2D gel electrophoresis was performed as described earlier (39). A 13-cm immobilized dry strip with a pH range of 4 to 7 (GE Healthcare) soaked with 800 μg of protein was used for isoelectric focusing (IEF). The steps for IEF and 2D gel electrophoresis were carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions (GE Healthcare). After in-gel trypsin digestion, samples were analyzed by MALDI-MS/MS. The peptide mass list obtained from the analyzer (ABI) was used for a Mascot search against the NCBI database.

DNA manipulations and construction of plasmids.

Recombinant DNA work was performed according to standard protocols (40). To study the transcriptional regulation of exaA, an exaA::lacZ fusion (pVSS1) was constructed in vector pCZ750 (41) harboring a promoterless lacZ reporter. The upstream region (313 bp) of exaA was obtained by PCR amplification using the primers ExaAF/ExaAR (Table 3). For complementation of the exaA::Km and rpoN::Km mutants, the exaA gene (1,964 bp) and the rpoN gene along with the gene encoding σ54-modulating protein (2,176 bp) were cloned into a broad-host-range expression vector, pMMB206 (42), to construct recombinant plasmids pVSSC2 and pVSSC1, respectively (Table 2).

Determination of TSS.

The transcription start site (TSS) of the exaA gene was determined by using a 3′/5′ RACE kit (Roche), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, total RNA was isolated by the TRIzol method from A. brasilense Sp7 cells collected from stationary-phase cultures grown in glycerol minimal medium. After DNase I treatment, the exaA transcript was reverse transcribed into cDNA by gene-specific primer QGSP1 (Table 3). The cDNA was purified, and a poly(dA) tail was added at the 3′ end. The resulting poly(dA)-tailed cDNA was amplified by PCR using the oligo(dT) anchor primer provided with the kit and the QGSP2 primer, which was complementary to the region upstream of the QGSP1 binding site. The amplicons from the first PCR were used as the template in the second PCR using the anchor primer provided with the kit and the QGSP3 primer, which is complementary to the region further upstream of the QGSP2 binding site. Amplified products obtained from the second PCR were ligated into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), and the nucleotide sequences of more than 20 distinct clones were determined by the ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer (ABI).

Construction of exaA::lacZ fusion and its mutant derivatives.

An analysis of the upstream region (313 bp) of exaA revealed two palindromic sequences which were located 172 and 28 bp upstream of ATG. These palindromes formed strong loops even at 90°C. To check the role of these loops in the regulation of exaA expression, we constructed mutant copies of the upstream region in which loops were permanently opened by replacing TCCCGTC with GACGGGA and CGATCCGCCCCGG with CCGGGGCGGATCG, using a modified overlap extension technique (43), and the primers used are listed in Table 3. Wild-type and mutant amplicons of the promoter were cloned in pCZ750 vector. Wild-type and recombinant constructs (pAPDM7 and pAPDM13) (Table 2) were conjugatively mobilized into A. brasilense Sp7 via E. coli S17.1, and a β-galactosidase assay was performed (44).

β-Galactosidase assay.

A. brasilense Sp7 carrying pVSS1 plasmid was grown overnight in LB (5 ml) medium containing tetracycline (10 mg/ml) with shaking at 200 rpm and 30°C. Cells from a 1-ml culture were harvested, washed, and resuspended in an equal volume of minimal malate (40 mM) medium. The cell suspension was then diluted 5-fold in the same medium containing tetracycline and desired alcohols (0.5% [vol/vol]) and/or 40 mM fructose and succinate. β-Galactosidase activity was determined from an equal number of cells after incubating the cultures with shaking for 6 h at 30°C (45). A. brasilense Sp7 and the rpoN::Km mutant harboring pVSS1 plasmid were grown overnight in 5 ml of LB medium. Cultures (1 ml) were pelleted by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended in 30 ml of minimal medium containing 40 mM glycerol as the sole carbon source. Samples were collected after 3 h and β-galactosidase assays were performed (44).

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from A. brasilense Sp7 and its mutants using cultures grown for 30 h in minimal medium containing 40 mM glycerol. RNA was extracted by the TRIzol method, treated with DNase I (RNase-free) for 1 h at 37°C, and heat-inactivated at 65°C for 10 min. The quality of the RNA was checked by denaturing formaldehyde-agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR was carried out to check the DNA contamination for each RNA sample using a housekeeping gene (rpoD encoding σ70). DNA-free RNA was quantified by using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo). cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of RNA using a Fermentas kit. Real-time PCR was performed with the primer pair QRTF/QRTR (Table 3), which produced amplicons of 145 bp from the middle part of the exaA gene using SYBR green I (Roche) in a LightCycler 480 II instrument (Roche), according to the manufacturer's instruction. A small amplicon of rpoD was used as an endogenous control for relative quantification by the 2−ΔΔCT method (46).

EMSA.

Unlabeled (cold probe) and 5′-FAM-labeled oligonucleotides of the exaA upstream region, including the predicted ExaR-binding site (CTTTTGCCGCAGCGACGGGATTTTTTCCCGTCCCGTCCGGGATGT), where the underlined sequence is predicted to form secondary structure), along with their complementary strands, were synthesized. A 5′-FAM-labeled oligonucleotide having a mutation in the predicted ExaR-binding site (CTTTTGCCGCAGCGACGGGATTTTTGACGGGACCGTCCGGGATGT), along with its complementary strand, was also synthesized. In addition, an unlabeled oligonucleotide of the IR2 downstream region (competitor) and its complementary strand were also synthesized (Table 3). Equimolar concentrations of labeled oligonucleotides and the complementary oligonucleotides were denatured by heating at 95°C for 3 min, followed by annealing at 25°C for 5 min. Recombinant EraR protein was purified first by affinity chromatography with Ni-NTA and then by FPLC using a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare). The purity of recombinant protein was examined on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and verified by MALDI-MS/MS. The protein-DNA binding reaction was carried out in binding buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 20 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 500 ng of poly(dI-dC), and 0.3% BSA] on ice for 3 h. Each binding reaction was carried out using 1 pmol FAM-labeled DNA probe and different amounts of recombinant proteins. Competitor DNA probes were used at a 100× higher concentration of the labeled probe. DNA-protein complexes were resolved on a 12.5% native polyacrylamide gel, and the image was captured using the ImageQuant LAS 4000 software (GE Healthcare).

Bacterial two-hybrid assay for protein-protein interaction between EraR and RpoN.

For the bacterial two-hybrid assay, the complete eraR gene (659 bp) was cloned in pUT18C as well as in pKT25 (pVSS4 and pVSS8) (Table 2) using the primers PUTQF/PUTQR. Similarly, the rpoN gene (1,575 bp) was also cloned in pKT25 and pUT18C (pVSS7 and pVSS5) (Table 2) using the primers PKTRPNF and PKTRPNR (Table 3), respectively. The dctD gene, encoding a bEBP of A. brasilense, which is known to interact with RpoN, was also cloned in the pUT18C vector (pVSS6) (Table 2) using the primers PUTDCTDF/PUTDCTDR (Table 3) as a positive control. A study of the in vivo protein-protein interaction between EraR and RpoN was carried out using a bacterial two-hybrid system, as described earlier (47).

In vitro pulldown assay for protein-protein interaction.

The eraR (659 bp) and rpoN (1,644 bp) genes were cloned in pET28a (pVSS2) (Table 2) and pGEX-2TK (pVSS3) (Table 2), respectively. For in vitro pulldown assays, molar quantities (∼200 pmol) of purified 6×His-tagged EraR were mixed with 20 μl of Ni-NTA-agarose beads as bait to pull down the GST-tagged RpoN and GST proteins. Subsequently, the beads were incubated with a 3-fold molar excess of purified recombinant GST-tagged RpoN protein and GST protein in the binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 200 mM KCl, 5 mM DTT, and 0.1% Triton X-100) at 4°C for 2 h. The beads were washed extensively in washing buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 200 mM KCl, 5 mM DTT, and 0.5% Triton X-100), and at the end, the bound proteins were eluted by boiling the beads in 40 μl of cracking dye (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 2% SDS, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, and 100 mM DTT). Proteins were resolved in a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and visualized after staining with Coomassie R-250. The control reaction of EraR and GST proteins was subjected to a similar treatment, and 50% of the bait proteins were loaded as input material (48).

Detection of 6×His-tagged EraR and GST-tagged RpoN by Western immunoblotting.

The recombinant EraR and RpoN proteins used for the pulldown assay were resolved in a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and electroblotted onto the polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore). The blotted membrane was blocked overnight with skimmed milk (5%) dissolved in 1× PBST (phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20) and exposed to mouse monoclonal anti-GST (1:4,000 dilution) and anti-6× His (1:5,000 dilution) antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich) in two separate reactions for 1 h at room temperature with gentle shaking. The blot was washed three times with 1× PBST for 8 min each at room temperature. A polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse IgG–horseradish peroxidase antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a secondary antibody at a 1:10,000 dilution in 1× PBST buffer to probe the blot for 1 h. The blot was again washed three times with 1× PBST for 10 min each and developed by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution (6 mg of DAB in 10 ml of PBST containing 3% H2O2). Color development was terminated by using 1× PBST buffer.

Statistical analysis.

In figures with bar graphs, the letters above the bars represent a homogeneous subset of treatments. The subsets with the same letters indicate that means within subsets were at par (not significant), while subsets with different letters differed significantly from others. The numbers are calculated mean values at a 95% confidence level (P < 0.05).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

V.S.S. acknowledges support of a junior/senior research fellowship of the University Grants Commission, New Delhi. A.P.D. and A.G. acknowledge financial support from the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research and the Department of Science and Technology (Young Scientist Fellowship), respectively. S.S. also acknowledges financial support from the Department of Biotechnology, India.

We thank Mike Merrick (JIC, Norwich), Siddavatam Dayananda (University of Hyderabad), and Mukti Nath Mishra, BHU, for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Del Gallo M, Fendrik I. 1994. The rhizosphere and Azospirillum, p 57–75. In Okon Y. (ed), Azospirillum/plant associations. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martinez-Drets G, Del Gallo M, Burpee CL, Burris RH. 1984. Catabolism of carbohydrate and organic acids by the azospirilla. J Bacteriol 159:80–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartmann A, Zimmer W. 1994. Physiology of Azospirillum, p 15–41. In Okon Y. (ed), Azospirillum/plant associations. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claret C, Salmon JM, Romieu C, Bories A. 1994. Physiology of Gluconobacter oxydans during dihydroxyacetone production from glycerol. Appl Environ Microbiol 41:359–365. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding H, Yip CB, Geddes BA, Oresnik IJ, Hynes MF. 2012. Glycerol utilization by Rhizobium leguminosarum requires an ABC transporter and affects competition for nodulation. Microbiology 158:1369–1378. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.057281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.González-Pajuelo M, Meynial-Salles I, Mendes F, Soucaille P, Vasconcelos I. 2006. Microbial conversion of glycerol to 1,3-propanediol: physiological comparison of a natural producer, Clostridium butyricum VPI 3266, and an engineered strain, C. acetobutylicum DG1(pSPD5). Appl Environ Microbiol 72:96–101. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.1.96-101.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prust C, Hoffmeister M, Liesegang H, Wiezer A, Fricke WF, Ehrenreich A, Gottschalk G, Deppenmeier U. 2005. Complete genome sequence of the acetic acid bacterium Gluconobacter oxydans. Nat Biotechnol 23:195–200. doi: 10.1038/nbt1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsushita K, Toyama H, Adachi O. 1994. Respiratory chains and bioenergetics of acetic acid bacteria. Adv Microb Physiol 36:247–301. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(08)60181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adachi O, Fujii Y, Ghaly MF, Toyama H, Shinagawa E, Matsushita K. 2001. Membrane-bound quinoprotein d-arabitol dehydrogenase of Gluconobacter suboxydans IFO 3257: a versatile enzyme for the oxidative fermentation of various ketoses. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 65:2755–2762. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugisawa T, Hoshino T. 2002. Purification and properties of membrane-bound d-sorbitol dehydrogenase from Gluconobacter suboxydans IFO 3255. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 66:57–64. doi: 10.1271/bbb.66.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsushita K, Fujii Y, Ano Y, Toyama H, Shinjoh M, Tomiyama N, Miyazaki N, Sugisawa T, Hoshino T, Adachi O. 2003. 5-Keto-d-gluconate production is catalyzed by a quinoprotein glycerol dehydrogenase, major polyol dehydrogenase, in Gluconobacter species. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:1959–1966. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.4.1959-1966.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toyama H, Fujii A, Matsushita K, Shinagawa E, Ameyama M, Adachi O. 1995. Three distinct quinoprotein alcohol dehydrogenases are expressed when Pseudomonas putida is grown on different alcohols. J Bacteriol 177:2442–2450. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2442-2450.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arai H, Sakurai K, Ishii M. 2016. Metabolic Features of Acetobacter aceti, p 255–271. In Matsushita K, Toyama H, Tonouchi N, Okamoto-Kainuma A (ed), Acetic acid bacteria: ecology and physiology. Springer Japan KK, Tokyo, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toyama H, Mathews FS, Adachi O, Matsushita K. 2004. Quinohemoprotein alcohol dehydrogenases: structure, function, and physiology. Arch Biochem Biophys 428:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rupp M, Görisch H. 1988. Purification, crystallisation and characterization of quinoprotein ethanol dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler 369:431–439. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1988.369.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reichmann P, Gorisch H. 1993. Cytochrome c550 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochem J 289:173–178. doi: 10.1042/bj2890173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goebel EM, Krieg NR. 1984. Fructose catabolism in Azospirillum brasilense and Azospirillum lipoferum. J Bacteriol 159:86–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanstockem M, Michiels K, Vanderleyden J, Van Gool A. 1987. Transposon mutagenesis of Azospirillum brasilense and Azospirillum lipoferum: physical analysis of Tn5 and Tn5-mob insertion mutants. Appl Environ Microbiol 53:410–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrios H, Valderrama B, Morett E. 1999. Compilation and analysis of sigma (54)-dependent promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 27:4305–4313. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.22.4305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schobert M, Gorisch H. 2001. A soluble two-component regulatory system controls expression of quinoprotein ethanol dehydrogenase (QEDH) but not expression of cytochrome c550 of the ethanol-oxidation system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 147:363–372. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-2-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karimova G, Pidoux J, Ullmann A, Ladant D. 1998. A bacterial two-hybrid system based on a reconstituted signal transduction pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:5752–5756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferenci T. 1996. Adaptation to life at micromolar nutrient levels: the regulation of Escherichia coli glucose transport by endoinduction and cAMP. FEMS Microbiol Rev 18:301–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1996.tb00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chattopadhyay A, Förster-Fromme K, Jendrossek D. 2010. PQQ-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase (QEDH) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is involved in catabolism of acyclic terpenes. J Basic Microbiol 50:119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vangnai AS, Arp DJ, Sayavedra-Soto LA. 2002. Two distinct alcohol dehydrogenases participate in butane metabolism by Pseudomonas butanovora. J Bacteriol 184:1916–1924. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.7.1916-1924.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krause A, Leyser B, Miché L, Battistoni F, Reinhold-Hurek B. 2011. Exploring the function of alcohol dehydrogenases during the endophytic life of Azoarcus sp. strain BH72. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 24:1325–1332. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-05-11-0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monniot C, Zébré A C, Désirée Aké F M, Deutscher J, Milohanic E. 2012. Novel listerial glycerol dehydrogenase- and phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent dihydroxyacetone kinase system connected to the pentose phosphate pathway. J Bacteriol 194:4972–4982. doi: 10.1128/JB.00801-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mern DS, Ha SW, Khodaverdi V, Gliese N, Gorisch H. 2010. A complex regulatory network controls aerobic ethanol oxidation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: indication of four levels of sensor kinases and response regulators. Microbiology 156:1505–1516. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.032847-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gliese N, Khodaverdi V, Schobert M, Gorisch H. 2004. AgmR controls transcription of a regulon with several operons essential for ethanol oxidation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 17933. Microbiology 150:1851–1857. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26882-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jobling MG, Holmes RK. 1997. Characterization of hapR, a positive regulator of the Vibrio cholerae HA/protease gene hap, and its identification as a functional homologue of the Vibrio harveyi luxR gene. Mol Microbiol 26:1023–1034. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6402011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pompeani AJ, Irgon JJ, Berger MF, Bulyk ML, Wingreen NS, Bassler BL. 2008. The Vibrio harveyi master quorum-sensing regulator, LuxR, a TetR-type protein is both an activator and a repressor: DNA recognition and binding specificity at target promoters. Mol Microbiol 70:76–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bush M, Dixon R. 2012. The role of bacterial enhancer binding proteins as specialized activators of σ54-dependent transcription. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76:497–529. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00006-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Studholme DJ, Dixon R. 2003. Domain architectures of sigma54-dependent transcriptional activators. J Bacteriol 185:1757–1767. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.6.1757-1767.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huo YX, Nan BY, You CH, Tian ZX, Kolb A, Wang YP. 2006. FIS activates glnAp2 in Escherichia coli: role of a DNA bend centered at −55, upstream of the transcription start site. FEMS Microbiol Lett 257:99–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bertoni G, Fujita N, Ishihama A, de Lorenzo V. 1998. Active recruitment of σ54-RNA polymerase to the Pu promoter of Pseudomonas putida: role of IHF and αCTD. EMBO J 17:5120–5128. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.5120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Kolb A, Buck M, Wen J, Gara F, Buc H. 1998. CRP interacts with promoter-bound σ54 RNA polymerase and blocks transcriptional activation of the dctA promoter. EMBO J 17:786–796. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.3.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alatoom AA, Aburto R, Hamood AN, Colmer-Hamood JA. 2007. VceR negatively regulates the vceCAB MDR efflux operon and positively regulates its own synthesis in Vibrio cholerae 569B. Can J Microbiol 53:888–900. doi: 10.1139/W07-054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reference deleted.

- 38.Reference deleted.

- 39.Kumar S, Rai AK, Mishra MN, Shukla M, Singh PK, Tripathi AK. 2012. RpoH2 sigma factor controls the photooxidative stress response in a non-photosynthetic rhizobacterium, Azospirillum brasilense Sp7. Microbiology 158:2891–2902. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.062380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dombrecht B, Vanderleyden J, Michiels J. 2001. Stable RK2-derived cloning vectors for the analysis of gene expression and gene function in Gram-negative bacteria. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 14:426–430. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morales VM, Backman A, Bagdasarian M. 1991. A series of wild-host-range low-copy-number vectors that allow direct screening for recombinants. Gene 97:39–47. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90007-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. 1989. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Promden W, Vangnai AS, Toyama H, Matsushita K, Pongsawasdi P. 2009. Analysis of the promoter activities of the genes encoding three quinoprotein alcohol dehydrogenases in Pseudomonas putida HK5. Microbiology 155:594–603. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.021956-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. 2008. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protoc 3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Battesti A, Bouveret E. 2012. The bacterial two-hybrid system based on adenylate cyclase reconstitution in Escherichia coli. Methods 58:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gupta N, Gupta A, Kumar S, Mishra R, Singh C, Tripathi AK. 2014. Cross-talk between cognate and noncognate RpoE sigma factors and Zn2+-binding anti-sigma factors regulates photooxidative stress response in Azospirillum brasilense. Antioxid Redox Signal 20:42–57. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Biotechnology 1:784–791. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nur I, Steinitz YL, Okon Y, Henis Y. 1981. Carotenoid composition and function in nitrogen-fixing bacteria of the genus Azospirillum. J Gen Microbiol 122:27–32. [Google Scholar]