Abstract

Background: Congenital hypothyroidism (CH), as one of the most common congenital endocrine disorders, may be significantly associated with congenital malformations. This study investigates urogenital abnormalities in children with primary CH (PCH).

Methods: This case-control study was conducted on 200 children aged three months to 1 year, referred to Amir-Kabir Hospital, Arak, Iran. One hundred children with PCH, as the case group, and 100 healthy children, as the control group, were selected using convenient sampling. For all children, demographic data checklists were filled, and physical examination, abdomen and pelvic ultrasound and other diagnostic measures (if necessary) were performed to evaluate the congenital urogenital abnormalities including anomalies of the penis and urethra, and disorders and anomalies of the scrotal contents.

Results: Among 92 (100%) urogenital anomalies diagnosed, highest frequencies with 37 (40.2%), 26(28.2%) and 9 (9.7%) cases including hypospadias, Cryptorchidism, and hydrocele, respectively. The frequency of urogenital abnormalities among 32 children with PCH, with 52 cases (56.5%) was significantly higher than the frequency of abnormalities among the 21 children in the control group, with 40 cases (43.4%). (OR=2.04; 95%CI: 1.1-3.6; p=0.014).

Conclusion: Our study demonstrated that PCH is significantly associated with the congenital urogenital abnormalities. However, due to the lack of evidence in this area, further studies are recommended to determine the necessity of conducting screening programs for abnormalities of the urogenital system in children with CH at birth.

Keywords: Congenital hypothyroidism, Urogenital abnormalities, Children

↑ What is “already known” in this topic:

Currently, children with congenital hypothyroidism (CH) in Iran do not pass routine screening for urogenital abnormalities. Cardiac and gastrointestinal anomalies are the most common congenital anomalies associated with CH.

→What this article adds:

Since PCH was significantly associated with the congenital urogenital abnormalities, management of anomalies associated with the CH, especially in children PCH, may lead to appropriate management of patients with this disorder

Introduction

Congenital malformation is one of the causes of death in newborns (1). Congenital hypothyroidism (CH) is also one of the common causes of congenital endocrine disorder found in about 1 out of 3,000 to 4,000 live births (2). Based on the evidence, the prevalence of CH in the United States increased by 73% from 1 987 to 2002 (3). As a routine, in many parts of the world, children are evaluated and screened for CH at birth (4). Thyroid digenesis is the cause of 85% of the CH cases, and other causes of this disorder are related to the dyshormonogenesis (5). Based on the evidence, CH can be associated with congenital malformations (6-11). Cardiac and gastrointestinal anomalies are the most common congenital anomalies associated with CH (10,12-18). The relationship between extra-thyroidal malformations (ECMs) and CH in newborns may indicate the role of common genetic components in the etiology of CH and its related anomalies (13); so that, recently, evidence of a genetic link between the incidence of CH and other congenital anomalies have been proposed (12). Based on this evidence, mutations in the genes PAX8 (paired box 8), FOXE1 (forkhead box E1), TTF1 (thyroid transcription factor 1), TTF2 (thyroid transcription factor 2) and TSHR (Thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor) can be associated with thyroid dysplasia and malformations involving the kidney, lung, forebrain, and palate, in addition to interfere with the thyroid follicular cell development (19-23). A better understanding of anomalies associated with the CH, as well as the molecular mechanisms that may be involved in thyroid disorders and its related anomalies could be a critical step towards the identification of the etiology of CH, followed by appropriate management of patients with this disorder (13).

Anomalies of the urogenital system including the anomalies of the urinary tract from the beginning of the urethra consist of the anomalies of the urethra, genitalia, and scrotum and are of great importance in children (24). Some of these anomalies lead to obstruction and dysfunction of the upper urinary tract, even the kidneys, and some others are important causes of sexual dysfunction in future and recurrent urinary infections in infants (24). Several case reports showed that children with CH have disorders in kidney and urinary tract development as well (25-27). However, because of the importance of anomalies associated with CH and studies conducted on urogenital abnormalities in children with CH are small (12), evaluation of these important abnormalities in newborns with CH seems reasonable.

Based on what was said, and the fact that currently the children with CH do not pass routine screening for urogenital abnormalities, the aim of this study was to investigate urogenital abnormalities in children with primary CH (PCH).

Methods

Data

This case-control study was conducted on 200 children aged three months to one year, referred to Amir Kabir hospital, Arak, Iran. 100 children with PCH were selected as the case group and 100 healthy children were included in the study as the control group. Positive results of thyroid screening test performed during the first week after birth (blood test taken from the baby's heel) using serum thyroid function test, including measurement of Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), T4 or free T4 was confirmed by radioimmunoassay (7,13)

As newborns in Iran do pass routine neonatal screening for thyroid disorders, the case group patients were consisted of newborns diagnosed with PCH in the medical center under study, or patients from other provincial medical centers referred to Amir-Kabir Hospital to confirm the diagnosis of CH and start the alternative thyroid therapy.

After obtaining informed consent from parents or the guardians of children, subjects in the two groups were included in the study using convenient sampling method.

Healthy children were selected from children who had referred to two hospitals for common cold, abdominal pain, etc. Matching method was used for selecting the healthy children and children were matched in two groups regarding age and sex.

A check list of demographic and clinical data was completed for each child with the assistance of their parents. The checklist included age, sex, history of maternal exposure to hazardous agents during pregnancy, mother's age during pregnancy, mother's education, family income and history of CH in the first-degree family of children.

Mother's age at pregnancy was classified in one of the three groups of 20 ?, 30-21, and 31? years old. Mother's education was classified in one of the four groups of 1) under diploma, 2) diploma, 3) associate and bachelor, and 4) doctorate and post-doctorate. Family income was classified in one of three groups of less than 5000,000 Rials (low income), 5000,000 to 10 million Rials (medium income) and more than 10 million Rials (high income). The history of mother's exposure to risk factors during pregnancy was defined as the history of consumption of any amount of cigarettes, alcohol and drugs abuse during the first three months of pregnancy. A history of developing CH in the family was defined as the history of CH diagnosed in the first-degree relatives (father, mother, brother or sister).

Children in both groups were examined in detail in terms of urogenital anomalies; they also underwent an abdominal and pelvic ultrasound and, if necessary, other measures. Examination of the children was performed by a nephrologist and the radiology procedures by an expert radiologist. According to these diagnostic measures, the selected anomalies in this study including anomalies of the penis and urethra, and disorders and anomalies of the scrotal contents (24,29) as follows:

1) Anomalies of the Penis and Urethra in boys: Posterior Urethral Valves (PUV), Meatal stenosis, Parameatal urethral cyst, Urethral duplication, congenital urethral fistula, Megalourethra, Urethral hypoplasia, Urethral atresia, Hypospadias, Phimosis, Paraphimosis, Micropenis, Penile torsion, Inconspicuous penis, Agenesis of the penis, lateral penile curvature, 2) Anomalies of the Urethra in girls: Urethral prolapse, Paraurethral cyst, Prolapsed ectopic ureterocele, 3) Disorders and Anomalies of the Scrotal Contents: Undescended testis (Cryptorchidism), Testicular (spermatic cord) torsion, Hydrocele, Inguinal hernia, Testicular tumor.

Children with anomalies developed due to events after birth were excluded from the study.

This study was confirmed by the Ethics Committee of Arak University of Medical Sciences; and all stages of this study conformed to Helsinki declaration principles, and a written informed consent was obtained from all of the participants’ parents.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS version 18 software. Descriptive statistics were reported. Prevalence, odds ratios (OR), and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated for the risk of having congenital anomalies in children with hypothyroidism and those without. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

The mean±SD age of children in the PCH and control groups were 7.4±2.71 and 7.8±2.93 months, respectively (p=0.342). There were 40 (40%) boys and 60 (60%) girls in the case group and 43 (43%) boys and 57 (57%) girls in the control group (p=0.774). Other demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Frequency distribution of the variables .

| Variable | Category | PCH1 group (n=100) N (%) | Healthy group (n=100) N (%) | p2 |

| Positive history of cigarette smoking | - | 23(23) | 13(13) | 0.097 |

| Positive history of Alcohol consumption | - | 7(7) | 1(1) | 0.065 |

| Positive history of drugs abuse | - | 4(4) | 1(1) | 0.369 |

| Positive family history of CH | - | 11(11) | 2(2) | 0.018 |

| Mother's education | Under Diploma | 24(24) | 5(5) | |

| Diploma | 45(45) | 25(25) | ||

| Associate and Bachelor | 27(27) | 57(57) | 0.001 | |

| Doctorate and Post-Doctorate | 4(4) | 13(13) | ||

| Mother's age at pregnancy (year) | 20 ≥ | 5(5) | 13(13) | |

| 30-21 | 34(34) | 69(69) | 0.001 | |

| 31≤ | 61(61) | 18(18) | ||

| Family income | Low3 | 8(8) | 13(13) | |

| Medium4 | 50(50) | 39(39) | 0.229 | |

| High5 | 48(48) | 42(42) |

1Children with primary congenital hypothyroidism, 2 p-values less than .05 were considered significant, 3 Family income less than 5000,000 Rials, 4 Family income 5000,000 to 10 million Rials, 5 Family income more than 10 million Rials

The results showed that the mother's education (OR=2.6; 95%CI:1.6-4.2; p=0.001), family history of CH (OR=6; 95%CI: 1.3-28; p=0.018) and mother's age at the pregnancy (OR =0.8; 95%CI:0.8-0.9; p=0.001) have significant relationship with development of PCH. So that, the prevalence of PCH was significantly higher in the group of mothers with secondary education (diploma), having a positive family history of CH and ?31 maternal age during pregnancy.

Of 92 urogenital abnormalities diagnosed among 32 children in the case group and 21 children in the control group, 52 (56.5%) and 40 (43.4%) cases of anomalies were associated with children in the case and control groups, respectively. Accordingly, the prevalence of urogenital abnormalities in the children with PCH was significantly more than healthy children. (OR=2.04; 95%CI: 1.1-3.6; p=0.014)

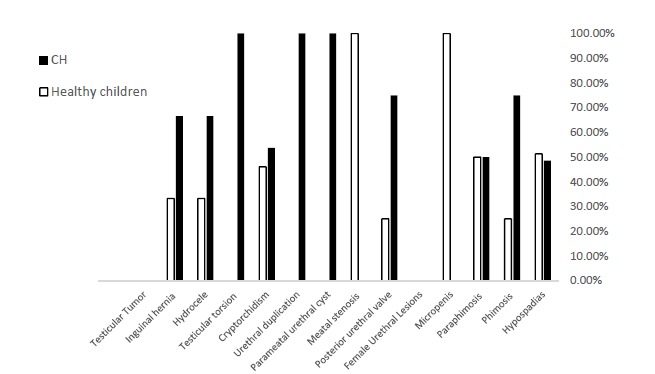

The frequencies of urogenital anomalies in the groups of case and control are depicted in Table 2 and Figure 1. Among 92 urogenital anomalies diagnosed, highest frequencies with 37 (40.2%), 26 (28.2%) and 9 (9.7%) cases including hypospadias, cryptorchidism, and hydrocele, respectively.

Table 2. The frequency distribution of Urogenital Abnormalities in children with primary congenital hypothyroidism and healthy children .

| Urogenital abnormalities | abnormalities in the PCH group b N (%) | abnormalities in the healthy group N (%) | Total of abnormalities N (100%) | p |

| Anomalies of the Penis and Urethra in boys | ||||

| Hypospadias | 18(48.6) | 19(51.3) | 37(100) | 0.423 |

| Phimosis | 3(75) | 1(25) | 4(100) | 0.621 |

| Paraphimosis | 1(50) | 1(50) | 2(100) | >0.05 |

| Micropenis | 0(0) | 1(100) | 1(100) | >0.05 |

| Other penis anomalies1 | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0 | - |

| PUV2 | 3(75) | 1(25) | 4(100) | 0.621 |

| Meatal stenosis | 0(0) | 1(100) | 1(100) | 0.412 |

| Parameatal urethral cyst | 1(100) | 0(0) | 1(100) | 0.311 |

| Urethral duplication | 1(100) | 0(0) | 1(100) | 0.513 |

| Other urethral anomalies3 | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | - |

| Anomalies of the Urethra in girls | ||||

| Urethral prolapse | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | - |

| Paraurethral cyst | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | - |

| Prolapsed ectopic ureterocele | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | - |

| Disorders and Anomalies of the Scrotal Contents | ||||

| Undescended testis | 14(53.8) | 12(46.1) | 26(100) | 0.843 |

| Testicular (spermatic cord) torsion | 3(100) | 0(0) | 3(100) | 0.246 |

| Hydrocele | 6(66.6) | 3(33.3) | 9(100) | 0.498 |

| Inguinal hernia | 2(66.6) | 1(33.3) | 3(100) | 0.712 |

| Testicular tumor | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | - |

| Total Urogenital abnormalities N (%) | 52(56.5) | 40(43.4) | 92(100) | 0.014 |

1Penile torsion, Inconspicuous penis, Agenesis of the penis, lateral penile curvature, 2 Posterior urethral valves, 3 congenital urethral fistula, Megalourethra, Urethral hypoplasia, Urethral atresia

Fig. 1.

The frequency of Urogenital Abnormalities in children with primary congenital hypothyroidism and healthy children

This order of prevalence, i.e. hypo-spadias, cryptorchidism, and hydrocele, included 18 (34.6%), 14 (26.9%), and 6 (11.5%) cases, out of 52 diagnosed anomalies in the PCH group and 19 (47.5%), 12 (30%), and 3 (7.5%) cases, out of 40 (100%) anomalies in the healthy group. Among 117 girls in both groups, no urogenital (urethral) anomalies were found. Although the difference of all urogenital anomalies between the groups was significant, the difference of frequencies of none of the anomalies studied separately was significant between the groups (Table 2).

According to the results, no significant association existed between the anomalies and the history of the mother’s smoking, alcohol consumption, and drug abuse in the first trimester. The results of the two most common anomalies studied showed that hypospadias and cryptorchidism had no significant relationship with smoking history (p=0.52, p=0.07, respectively), alcohol consumption (p=0.06, p=0.4), and drug abuse (p=0.69, p=0.23). In this regard, among 37 children with hypospadias, 6 (16.2%), 0 and 1 (2.7%), and among 26 children with cryptorchidism, 8 (30.7%), 2 (7.6%), and 0 children had mothers with a history of smoking, alcohol consumption, and drug abuse, respectively.

Discussion

The main objective of our study was to examine those ECMs which are less studied in children with CH. Based on our results, the prevalence of urogenital abnormalities in children with PCH was significantly higher than children without CH.

Based on the New York State Congenital Malformation Registry, Kumar J et al. (12) among 980 children with CH and 3,661,585 healthy children born between 1992 and 2005 in the United States, showed that children with CH are significantly prone to comorbidity of renal and urinary tract anomalies, particularly hydronephrosis, hypospadias and renal agenesis.

Based on neonatal screening in four northeastern regions of Italy, Cassio A et al. (7) examined 235 newborns with CH selected from among 745.801 newborns screened in terms of congenital malformations. Authors showed that the prevalence of congenital anomalies in children with CH and the general population was 9.4% and 1.8%, respectively. Based on this study, the prevalence of internal urogenital anomalies in children with CH and the general population of children was 0.43% and 0.11%, respectively; there was no significant difference between the two groups. In the 2 case reports, Satomura K et al. (25) and Jeha GS et al. (27) introduced newborns that were diagnosed with glomerulocystic kidney disease (GCKD) and autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD), respectively, in addition to having CH. Reddy PA et al. (30) in 2010, in India, reported no cases of urogenital anomalies among 70 children with CH.

Most of the studies on congenital anomalies associated with CH have studied extra-urogenital malformations, and fewer studies are found to be conducted on the evaluation of renal and urogenital anomalies in children with CH. In a retrospective review, Gu YH et al. (31) studied ECMs among 1520 newborns. Based on this study, the incidence of ECMs in newborns with CH (222/1520, 14.6%) was significantly higher than the general population.

Olivieri A et al. (13) examined the incidence of congenital anomalies among 1420 children with CH born between 1991 and 1998 in Italy. In this study, the prevalence of congenital malformations in children with CH (8.4%) was four times the incidence in the general population (1.2%). Also, the results of this study showed that CH is significantly correlated with the risk of cardiac anomalies (more than any other anomalies), nervous system and ophthalmic anomalies.

In a cross-sectional study on 76 children with PCH, Kreisner E et al. (10) demonstrated that the prevalence of major congenital malformations in children with CH (13.2%) is significantly more than healthy children.

We showed that there is no significant relationship between urogenital anomalies and a history of smoking, alcohol consumption, and drug abuse in the first trimester of pregnancy.

In a study conducted on 483 newborns with renal malformations and 719 newborns with other urinary tract anomalies, apart from renal anomalies, Källen K et al. (32) reported a significant moderate correlation between maternal smoking history and the risk of congenital renal malformations including agenesis, hypoplasia, and dysplasia. However, according to this study, the association between the history of smoking and alcohol consumption by the mother during pregnancy and the risk of urinary tract anomalies were not significant. In a study conducted on 118 children with congenital anomalies of the urinary tract, Li DK et al. (33) found a strong association between smoking during pregnancy and the risk of congenital urinary tract anomalies. Clarren SK et al. (34) demonstrated that the incidence of renal hypoplasia and dysplasia could be related to the fetal alcohol syndrome. In a study of the fetus of 13 smoking mothers and 13 non-smoking mothers in weeks 22 to 28 and 33 to 38 of pregnancy period using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Anblagan D et al. (35) demonstrated that maternal smoking during pregnancy has a significant relationship with the growth retardation of fetal brain, lungs and kidneys.

According to the evidence obtained so far, although the mother’s smoking, alcohol consumption, and drug abuse during pregnancy can be related to the anomalies of the urogenital system, further studies can be performed in this field in the future because of the following reasons:

When a teratogen plays a role in the development of congenital malformations, determining the exact relationship between these factors and the risk of congenital anomalies is crucial for minimizing their frequencies and decreasing their short- and long-term complications (32).

The exact mechanism of the relationship between smoking, alcohol consumption, and drug abuse and urogenital anomalies is not known currently (32,35).

In addition to the small number of studies about the relationship between smoking, alcohol consumption, and drug abuse and the risk of urinary tract anomalies, their results are sometimes controversial, and they have investigated the anomalies of kidneys with fewer reports on urogenital anomalies.

Since only the relationship between a history of smoking, alcohol consumption, and drug abuse in the first trimester of pregnancy and the risk of urogenital anomalies are studied, it is proposed to perform further studies in this field considering the relationship between the amount of smoking and alcohol and drugs consumed by mother, as well as the type of the drugs during the entire pregnancy, and the risk of urogenital system anomalies.

Given the evidence of the involvement of a common genetic component to the development of CH and congenital anomalies associated with it (13,19-23), and according to numerous clinical evidence obtained about significant association between congenital anomalies and CH (7,10,12-18,31), the association between CH and congenital anomalies can be considered almost inevitable. However, due to the following reasons, continuing research in this area, particularly about anomalies that were less studied, (such as urogenital abnormalities conducted in the present study) is proposed for future studies.

1) Examination of the correlation between CH and different type of congenital anomalies can be helpful in better determining their possible common etiology (13)

2) While there are numerous evidence about the association of some congenital anomalies, especially cardiac anomalies with CH (10,12-18,30); however, evidence about the correlation of some prevalent congenital anomalies, including urogenital abnormalities with CH is little (12)

3) Further studies in the future and then reaching a comprehensive conclusion about the relationship between each of the congenital anomalies and CH, can be helpful in the better management of patients, planning for screening and preventive treatments to improve the prognosis in the children.

Some of the limitations of our study were the small sample size, lack of study of the extra urogenital abnormalities malformations (on the health center facilities under study) and failure to evaluate the prevalence of urogenital abnormalities based on the cause of congenital hypothyroidism. It is recommended that future studies in this area be conducted on a larger sample size, taking into consideration the CH causes, and other extra urogenital abnormalities.

We selected the urogenital anomalies introduced in the Nelson’s textbook of pediatrics (29), according to which the urogenital anomalies are very low in girls. This reason along with low sample size seems to be the causes of finding no urogenital anomalies in the girls; so, conclude screening is not necessary for girls is too early.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that PCH is significantly associated with the congenital urogenital abnormalities. However, due to the lack of evidence in this area, further studies are recommended to determine the necessity of conducting screening programs for abnormalities of the urogenital system in children with CH at birth.

Acknowledgments

The research team wishes to thank Vice-Chancellor for Research at Arak University of Medical Sciences and Amir Kabir Hospital for their financial support (Grant No. 843) and also the children and their parents who contributed to this research.

Conflict of Interest

None Declared.

Cite this article as: Yousefichaijan P, Dorreh F, Sharafkhah M, Amiri M, Ebrahimimonfared M, Rafeie M, Fatemeh Safi. Congenital urogenital abnormalities in children with congenital hypothyroidism. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2017 (30 Jan);31:8. https://doi.org/10.18869/mjiri.31.7

References

- 1.Miniño AM, Heron MP, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics National Vital Statistics System. Deaths: final data for 2004, Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2007;55:1–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toublanc JE. Comparison of epidemiological data on congenital hypothyroidism in Europe with those of other parts of the world . Horm Res (Basel) 1992;38:230–5. doi: 10.1159/000182549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris KB, Pass KA. Increase in congenital hypothyroidism in New York State and in the United States. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2007;91:268–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Therrell BL, Hannon WH. National evaluation of US newborn screening system components. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2006;12(4):236–45. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Refetoff S, Dumont JE, Vassart G. Thyroid disorders. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors.The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited diseases. McGraw Hill; New York 2001. 4029-76.

- 6.Roberts HE, Moore CA, Fernhoff PM, Brown AL, Khoury MJ. Population study of congenital hypothyroidism and associated birth defects, Atlanta, 1979-1992. Am J Med Genet. 1997;71:29–32. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19970711)71:1<29::aid-ajmg5>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassio A, Tato L, Colli C, Spolletini E, Costantini E, Cacciari E. Incidence of congenital malformations in congenital hypothyroidism. Screening. 1994;3:125–30. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oakley GA, Muir T, Ray M, Girdwood RWA, Kennedy R, Donaldson MDC. Increased incidence of congenital malformations in children with transient elevation of thyroid-stimulating hormone on neonatal screening. J Pediatr. 1998;132:726–30. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernhoff PM. Congenital hypothyroidism and associated birth defects: implications for investigators and clinicians. J Pediatr. 1998;132:573–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreisner E, Neto EC, Gross JL. High prevalence of extra thyroid malformations in a cohort of Brazilian patients with permanent primary congenital hypothyroidism. Thyroid. 2005;15:165–9. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taji EA, Biebermann H, Límanová Z, Hníková O, Zikmund J, Dame C. et al. Screening for mutations in transcription factors in a Czech cohort of 170 patients with congenital and early-onset hypothyroidism: identification of a novel PAX8 mutation in dominantly inherited early-onset non-autoimmune hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;156:521–9. doi: 10.1530/EJE-06-0709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar J, Gordillo R, Kaskel FJ, Druschel CM, Woroniecki RP. Increased prevalence of renal and urinary tract anomalies in children with congenital hypothyroidism. J Pediatr. 2009 Feb;154(2):263–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olivieri A, Stazi MA, Mastroiacovo P, Fazzini C, Medda E, Spagnolo A. et al. Study Group forCongenital Hypothyroidism A population-based study on the frequency of additional congenital malformations in infants with congenitalhypothyroidism: data from the Italian Registry for Congenital Hypothyroidism (1991-1998) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002 Feb;87(2):557–62. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazarus JH, Hughes IA. Congenital abnormalities and congenital hypothyroidism. Lancet. 1988;2:52. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92987-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siebner R, Merlob P, Kaiserman I, Sack J. Congenital anomalies concomitant with persistent primary congenital hypothyroidism. Am J Med Gen. 1992;44:57–60. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320440114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cassio A, Tato` L, Colli C, Spolettini E, Costantini E, Cacciari E. Incidence of congenital malformations in congenital hypothyroidism. Screening. 1994;3:125–130. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts HE, Moore CA, Fernhoff PM, Brown AL, Khoury MJ. Population study of congenital hypothyroidism and associated birth defects, Atlanta, 1979-1992. Am J Med Gen. 1997;71:29–32. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19970711)71:1<29::aid-ajmg5>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Jurayyan NA, Al-Herbish AS, El-Desouki MI, Al-Nuaim AA, Abo-BakrAM Abo-BakrAM, Al-Husain MA. Congenital anomalies in infants with congenitalhypothyroidism: is it a coincidental or an associated finding? Hum Hered. 1997;47:33–37. doi: 10.1159/000154386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trueba SS, Auga J, Mattei G, Etchevers H, Martinovic J, Czernichow P. et al. PAX8, TITF1, and FOXE1 gene expression patterns during human development: new insights into human thyroid development and thyroid dysgenesis-associated malformations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:455–62. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plachov D, Chowdhury K, Walther C, Simon D, Guenet JL, Gruss P. Pax8, a murine paired box gene expressed in the developing excretory system and thyroid gland. Development. 1990;110:643–51. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.2.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krude H, Macchia PE, Di Lauro R, Grüters A. Familial hypothyroidism due to thyroid dysgenesis caused by dominant mutations of the PAX8 gene. Proc of the 37th Annual Meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology; Florence, Italy 1998:43.

- 22.Meeus L, Gilbert B, Rydlewski C, Parma J, Roussie AL, Abramowicz M. et al. Characterization of a novel loss of function mutation of PAX8 in a familial case of congenital hypothyroidism with in-place, normal-sized thyroid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;89:4285–91. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouchard M, Souabni A, Mandler M, Neubuser A, Busslinger M. Nephric lineage specification by Pax2 and Pax8. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2958–70. doi: 10.1101/gad.240102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gheissari A, Hashemipour M, Khosravi P, Adibi A. Different aspects of kidney function in well-controlled congenital hypothyroidism. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2012 Dec;4(4):193–8. doi: 10.4274/Jcrpe.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Satomura K, Michigami T, Yamamoto K, Hosokawa S. A case report of glomerulocystic kidney disease with hypothyroidism in a newborn infant. Nippon Jinzo Gakkai Shi 1998;40:602-6. (In Japanese). [PubMed]

- 26.Taha D, Barbar M, Kanaan H, Williamson BJ. Neonatal diabetes mellitus, congenital hypothyroidism, hepatic fibrosis, polycystic kidneys, and congenital glaucoma: a new autosomal recessive syndrome? Am J Med Genet A. 2003;22:269–73. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeha GS, Tatevian N, Heptulla RA. Congenital hypothyroidism in association with Caroli's disease and autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease: patient report. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2005;18:315–8. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2005.18.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elder JS. Anomalies of the Bladder In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, Geme III JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE Nelson Textbook of pediatrics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders. 2011;Chapter:535. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Elder JS. Congenital Anomalies and Dysgenesis of the Kidneys. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, Geme III JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE. Nelson Textbook of pediatrics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2011; Chapter: 531.

- 30.Reddy PA, Rajagopal G, Harinarayan CV, Vanaja V, Rajasekhar D, Suresh V. et al. High prevalence of associated birth defects in congenital hypothyroidism. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2010;2010:940980. doi: 10.1155/2010/940980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bald M, Hauffa BP, Wingen AM. Hypothyroidism mimicking chronic renal failure in reflux nephropathy. Arch Dis Child 2000 Sep;83(3):251-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32. Källen K. Maternal smoking and urinary organ malformations. nt J Epidemiol 1997 Jun;26(3):571-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Li DK, Mueller BA, Hickok DE, Daling JR, Fantel AG, Checkoway H. et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and the risk of congenital urinary tract anomalies. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:249–53. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.2.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clarren SK, Smith DW. The fetal alcohol syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:1063–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197805112981906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anblagan D, Jones NW, Costigan C, Parker AJ, Allcock K, Aleong R. et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and fetal organ growth: a magnetic resonance imaging study. PLoS One 2013 Jul. 3;8(7):e67223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]