Abstract

Embryonic development is highly sensitive to xenobiotic toxicity and in utero exposure to environmental toxins affects physiological responses of the progeny. In the US, the prevalace of allergic asthma is inexplicably rising and in utero exposure to cigarette smoke (CS) increases the risk of allergic asthma (AA) and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) in children and animal models. We reported that gestational exposure to sidestream (secondhand) CS (SS) promoted nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-dependent exacerbation of AA and BPD in mice. Recently, perinatal nicotine injections in rats were reported to induce peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ)-dependent transgenerational transmission of asthma. Herein, we show that F1 and F2 progeny from gestationally SS-exposed mice exhibit exacerbated AA and BPD that is not dependent on the decrease in PPARγ levels. Lungs from these mice show strong eosinophilic infiltration, excessive Th2 polarization, marked airway hyperresponsiveness, alveolar simplification, decreased lung compliance, and decreased lung angiogenesis. At the molecular level, these changes are associated with increased RUNX3 expression, alveolar cell apoptosis, and the antiangiogenic factor GAX, and decreased expression of HIF-1α and pro-angiogenic factors NF-κB and VEGFR2 in the 7-day F1 and F2 lungs. Moreover, the lungs from these mice exhibit lower levels of micro-RNA (miR)-130a and increased levels of miR-16 and miR-221. These miRs regulate HIF-1α-regulated apoptotic, angiogenic, and immune pathways. Thus the intergenerational effects of gestational SS involve epigenetic regulation of HIF-1α through specific miRs contributing to increased incidence of AA and BPD in the progenies.

Keywords: Allergic asthma, Bronchopulmonary dysplasia, Secondhand cigarette smoke, Epigenetics, micro-RNAs

INTRODUCTION

Epidemiological studies suggest that some environmental toxicants affect fetal development and increase the susceptibility to lung diseases (1). Furthermore, exposure to some xenobiotics during pregnancy may adversely affects the health of children; some of these effects are transmittable to subsequent generations (2, 3). Maternal smoking during pregnancy remains relatively common (4, 5) and the risk of cigarette smoke (CS)-associated pulmonary complications are highest in the lungs that are exposed to CS in utero (6–9). Epidemiological evidence and animal studies suggest that exposure to mainstream CS or environmental/sidestream CS (SS) during pregnancy adversely affects the pulmonary health of the offspring, including a higher risk for allergic asthma and airway remodeling (7, 10–14) and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) (15–17). Moreover, CS exposure either during first (18) or third trimester (19) increases the risk of wheeze and asthma in children. We have reported that gestational exposure to SS promotes BPD-like alveolar simplification and marked exacerbation of allergen-induced Th2 polarization and severity of allergic asthma (AA) in mice (20, 21). Normal fetal development occurs under hypoxic conditions and HIF-1α is important for normal organogenesis (22, 23); however, HIF-1α expression is significantly reduced in gestationally SS-exposed animals (17). HIF-1α promotes angiogenesis and suppresses apoptosis; however, in utero SS-exposed mouse lungs have impaired angiogenesis and alveolarization and increased number of apoptotic epithelial cells in the airways (17, 21).

The prevalence of asthma in the US has been rising steadily, particularly among 0–4 yr-olds, where the incidence nearly tripled between 1980 and 1994 (24). Maternal smoking during pregnancy causes epigenetic changes, including methylation of some asthma-related genes (25). Increasing evidence suggest that lung diseases induced through in utero exposure to environmental toxins, are potentially transmitted transgenerationally (2, 3). Epidemiological evidence suggests that women smoking during pregnancy not only increase the risk of asthma in their unborn children but also among grandchildren (26). The mechanisms by which the transgenerational effects of smoking on asthma are manifested are not clear, but epigenetic mechanisms might be implicated (27). Moreover, perinatal exposure of rats to nicotine promotes development of asthma transgenerationally and the response is associated with decreased PPARγ through methylation of its promoter (28–30). In this communication, we show that gestational SS exacerbates AA and BPD transgenerationally through epigenetic mechanisms; however, the effects are independent of PPARγ but linked to specific microRNAs (miRs) that regulate apoptosis and angiogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Pathogen-free BALB/c mice (FCR Facility, Frederick, MD) were kept in exposure chambers and maintained at 26 ± 2°C and 12-hour light/dark cycle. Food and water were provided ad libitum. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Reagents

Buffers and Precast gels for the Western blot analysis were obtained from Bio Rad Laboratories Inc. (Hercules, CA). Specifics for other reagents including antibodies are provided in the description of methods

Gestational exposure to sidestream cigarette smoke (SS)

Adult (3–4 month old) male and female mice were separately acclimatized to SS or filtered air (FA) for 2 weeks, and then paired for mating under the same exposure conditions. Mice were whole-body exposed to SS or FA for 6 hours/day, 7 days/week using Type 1300 smoking machine (AMESA Electronics, Geneva, Switzerland) as described previously (Singh et al., 2013). The machine generated two 70 cm3 puffs/min from 2R1 cigarettes (Tobacco Health Research Institute, Lexington, KY). The dose of SS was approximately equivalent to the amount of SS a pregnant woman would receive by sitting in a smoking bar for 3 hr/day throughout the gestational period (21). After pregnancy was established, male mice were removed and the pregnant mice continued to receive SS or FA until the pups were born. Mice were sacrificed by an intraperitoneal injection of 0.2 ml Euthasol.

Sensitization with Aspergillus fumigatus proteins (Af)

Lyophilized culture filtrate preparation of Aspergillus fumigatus (Greer, Lenoir, NC) was used to elicit allergic response in the animals. Mice (7 weeks old) were immunized intratracheally with 0.1 ml Af (50 μg) in endotoxin-free sterile saline or sterile saline alone) and subsequently challenged intratracheally with 0.1 ml of Af (250 μg) three times at 5-day intervals (Singh et al., 2009). Control animals were given sterile saline.

Measurement of airway resistance and lung compliance

At 48 h after the last Af/saline administration, airway resistance (RL) and dynamic compliance (Cdyn) were measured by the FlexiVent system (SCIREQ, Montreal, Quebec, Canada). Briefly, mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection of avertin (250 mg/kg). A small incision was made in the trachea through which a 20-gauge needle hub was inserted and saline-filled catheter was placed in the esophagus via the mouth to obtain transthoracic pressure. The mouse was placed on the FlexiVent apparatus and ventilated through the tracheal cannula. Doxacurium (0.5 mg/kg) was administered i.p., and heart rate and electrocardiogram were monitored by a Grass Instruments Recorder with Tachograph. RL was assessed using increasing doses of aerosolized methacholine (MCh). RL and Cdyn were derived by manipulation of ventilatory patterns and measurement of upstream and downstream pressures. The peak responses at each MCh concentration were used for data analysis.

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) collection, cell differential, and cytokine analysis

Established protocols were followed to obtain BALF. Briefly, mice were anesthetized and killed by exsanguination at 48 h post last Af challenge. Before excision of the lungs, the trachea was surgically exposed, cannulated and, while the left lung lobe was tied off with a silk thread, the right lobe was lavaged twice with 1 ml sterile Ca 2+/Mg2+ free PBS (pH 7.4). Aliquots were pooled from individual animals. Cell differentials and cytokines assays were performed as described previously (13, 20). Number of macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and eosinophils (Eos) was determined microscopically by counting at least 300 cells/sample. BALF was analyzed for IL-13 and IFN-γ using the Mouse Cytokine ELISA kit (Biosource-Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) according to the manufacturer’s directions. The sensitivity of the assay was <10 pg/ml.

Preparation of lung tissues

Mice were sacrificed and the left lung was inflated and kept in 10% formalin bath at 20 cm pressure for 24 h (21). After washing, the lungs were embedded in paraffin and 5 μm thick sections were cut for histopathology and immunohistochemistry. The right lung was quickly frozen in liquid-N2, and kept at −80°C for making lung homogenates and RNA.

Immunostaining

H&E staining was performed on deparaffinized tissue sections using standard protocols (21). Computer-selected random areas of H&E-stained lung sections were used to quantitate alveolar volumes using NanoZoomer Digital Pathology slide scanner (Hamamatsu K. K. Photonics, Hamamatsu City, Japan). The analysis was done blind.

Immunofluorescence staining for HIF-1α, NF-κB, and CD31

After deparaffinization, immunofluorescence (IF) staining was performed as described previously (17, 21). Lung sections were stained with anti-HIF-1α antibody (Cat#: ab16066, Abcam) or anti- phospho-p65-NF-κB (pRelA) antibody (Cat#: 3033, Cell Signaling Tech). The slides were counter stained with anti-rabbit Alexa 564-conjugated secondary antibody (Cat#: A-11010, Life Technologies). Staining for CD31 (endothelial cell marker) was performed using rabbit anti-CD31 antibody (Cat#: ab28364; Abcam) at 1:2,000 dilution followed by DyLight 549–conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Singh et al., 2013). HIF-1α-, p65-, and CD31-positive cells in the lungs were counted blind using Axiplan 2 imaging (Hamamatsu, Japan) on computer selected 9000 μm2 areas. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue fluorescence). The procedure was repeated three times with different animals.

TUNEL Assay

To detect apoptotic cells, deparaffinized lung sections were stained using fluorescein In Situ Cell Death Detection kit (Cat#: 11 684 795 910; Roche Applied Science, Germany) as per manufacturer’s directions. TUNEL-positive cells were counted blinded.

Western blot analysis

Western blot (WB) analysis of lung homogenates was carried out as described previously (18, 21). Briefly, tissue samples were homogenized in RIPA buffer and the protein content of the extracts was determined by the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The homogenates were run on SDS-PAGE on 10% precast polyacrylamide gels (Bio Rad Lab, Hercules CA). The gels were transferred electrophoretically to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio Rad Lab). The blots were incubated with anti-PPARγ antibody (Cat#: sc-7273, Santa Cruz Biotech). The mouse anti-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotech) was used as a control for a house-keeping protein. After incubating with secondary antibody, immuno-detection was performed using Amersham ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare Bio-Science Corp. Piscataway, NJ) and the images were captured by Fujiform LAS-4000 luminescent image analyzer (FUJIFILM Corporation, Tokyo). Densitometry was used to quantitate the expression of specific proteins and the ratio of PPARγ to actin.

Methylation analysis of PPARγ promoter

Methylation of the CpG island flanking the start site of PPARγ promotor was performed by direct pyrosequencing after bisulfite modification and PCR amplification (EpigenDx, Hopkinton, MA). Assays were pre-validated to ensure that there was no preferential amplification for either methylated or unmethylated DNA.

RT-qPCR for microRNA (miRs), GATA-3 and T-bet

Total RNA isolated from F1 and F2 lungs was used to quantitate miR-16, miR-221, and miR-130a using RNeasy Plus Kit (Qiagen). Stem-loop qPCR was used with specific primers and reagents and the PCR products were amplified using TaqMan MicroRNA Assay together with the TaqMan Universal PCR master Mix and AB StepOnePlus Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The lung expression of GATA-3, T-bet and GAPDH were determined using the One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix and specific labeled primers/probes set (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The relative expression of each mRNA was calculated as previously described (13).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Graph Pad Prism software 5.03 (Graphpad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). The student’s t test was used for comparison between two groups at 95% confidence interval. Results were expressed as the means (± SD). A p value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

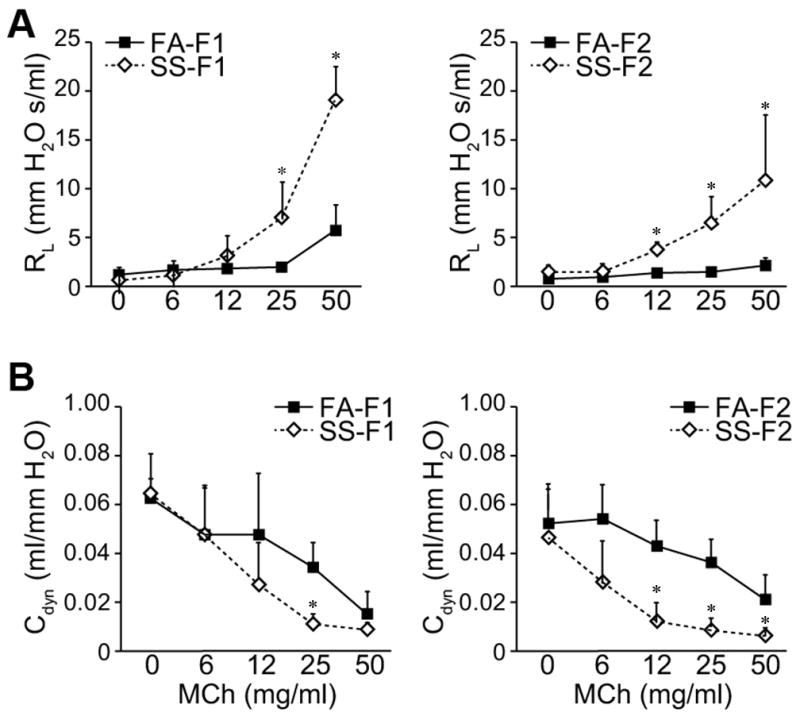

Gestational SS alters airway resistance and lung compliance in F1 and F2 mice

Gestational SS exacerbates Af-induced AA through increase in airway hyperresponsiveness (13, 20). In current experiments, dams were exposed to fresh air (FA) or SS two weeks prior to pregnancy and throughout the gestational period. Progeny derived from these mice (F1) and from mating of F1 (F2) were tested by FlexiVent system for airway resistance (RL) and lung compliance (Cdyn) after Af sensitization. We tested a total of 8 FA- and 17 SS-exposed mice from the F2 progeny of both sexes and compared their response to 6 FA- and SS-exposed mice from F1 generation. The magnitude of increase in airway resistance (Fig. 1A) and decrease in lung compliance (Fig. 1B) was similar in F1 and F2 animals from the SS-exposed dams. Thus, gestational SS exposure not only causes marked increase in airway hyperreactivity in F1 and F2, it also decreases lung compliance in both generations. Moreover, this transmission is independent of gender and exhibited by all the members of the F2 progeny. These results suggest that the inheritance of gestationally SS-induced asthma phenotype involves epigenetic rather than Mendelian genetic transmission.

Fig. 1. Transgenerational effects of gestational SS on airway hyperreactivity and dynamic lung compliance.

Lung resistance (RL) was measured using FlexiVent system in response to: (A), increasing doses of computer-controlled nebulized methacholine (MCh), (B), dynamic lung compliance (Cdyn), which reflects lung compliance at any given time during actual movement of air. Determination of RL and Cdyn was carried after Af-sensitization as described in Methods. The results are representative of two different sets of inhalation exposures. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6 –17/group). * ≤ p = 0.05; FA = filtered air, SS = sidestream cigarette smoke; F1: first generation; F2 second generation.

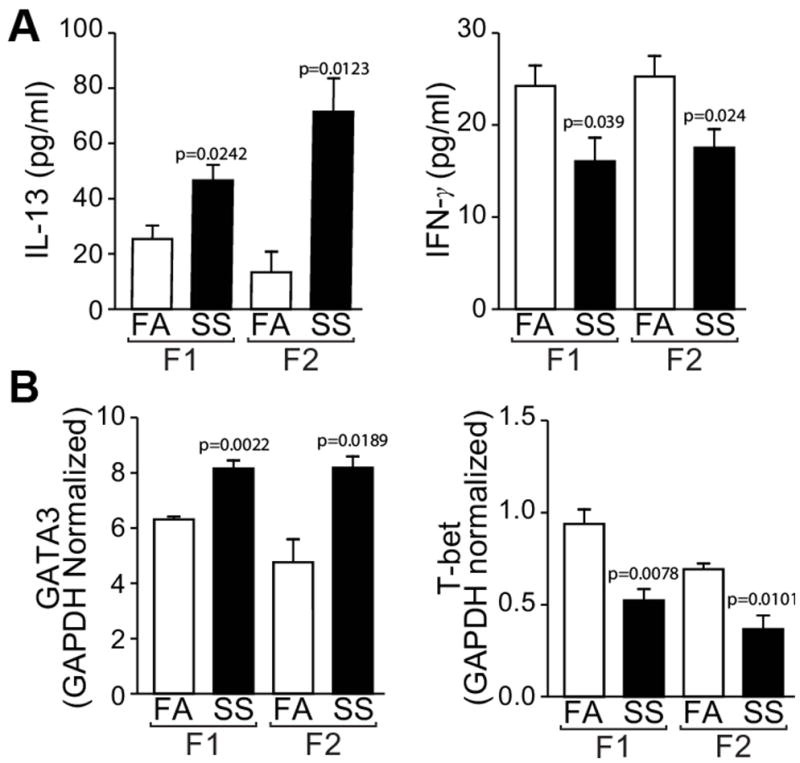

Gestational SS increases allergen-induced Th2 and decreases Th1 markers in F1 and F2 lungs

Gestational SS promotes Af-induced Th2 responses but decreases Th1 markers in F1 lungs (13, 20). To ascertain whether this propensity is transmitted to F2 progeny, following Af sensitization, BAL of F1 and F2 mice derived from FA- and SS-treated dams were analyzed for cellular composition and cytokine expression. Compared to FA, BAL from gestationally SS exposed mice had slightly but significantly higher number of total leukocytes in F1 (FA = 7.4 ± 0.6 x 105; SS = 11.3 ± 1.5 x 105, p=0.001) and F2 (FA = 6.3 ± 1.4 x 105; SS = 8.7 ± 1.1 x 105, p=0.05); however, compared to FA, SS-exposed F1 and F2 mice exhibited a marked difference in the cellular composition of the BAL, including the percentage of eosinophils in F1 (FA: 7.0 ± 3.2; SS: 63.5 ± 10.8, p=0.001) and F2 (FA: 8.6 ± 3.2; SS: 67.2 ± 2.3, p=0.0001) and macrophages: F1 (FA: 85.4 ± 5.7; SS: 26.5 ± 8.9, p=0.001) and F2 (FA: 81.3 ± 7.1; SS: 13.2 ± 3.8, p=0.0001). It is likely that decreased macrophages percentage in SS-exposed BAL reflects a large increase in the eosinophil count. Additionally, we measured the BAL levels of the Th2 cytokine IL-13 and the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ by ELISA (Fig. 2A) and the lung expression of the Th2 transcription factor GATA3 and the Th1 transcription factor T-bet by qPCR (Fig. 2B). Together these results indicate that gestational SS promotes Th2 and suppresses Th1 responses in the lungs of F1 and F2 progenies.

Fig. 2. Transgenerational effect of gestational SS-exposure on Th1/Th2 cytokines/transcription factors.

A: BALF levels of IL-13 (left panel) and IFN-γ ((right panel) were determined by the Mutiplex ELISA kit. B: Lung levels of GATA 3 (left panel) and T-bet (right panel) were determined by quantitative RT-PCR analysis total lung RNA from mice sensitized with Af as described in the Methods section. Results are representative of animal responses from two different sets of inhalation exposures. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 5–7/group. FA = filtered air, SS = secondhand cigarette smoke; F1: first generation; F2 second generation.

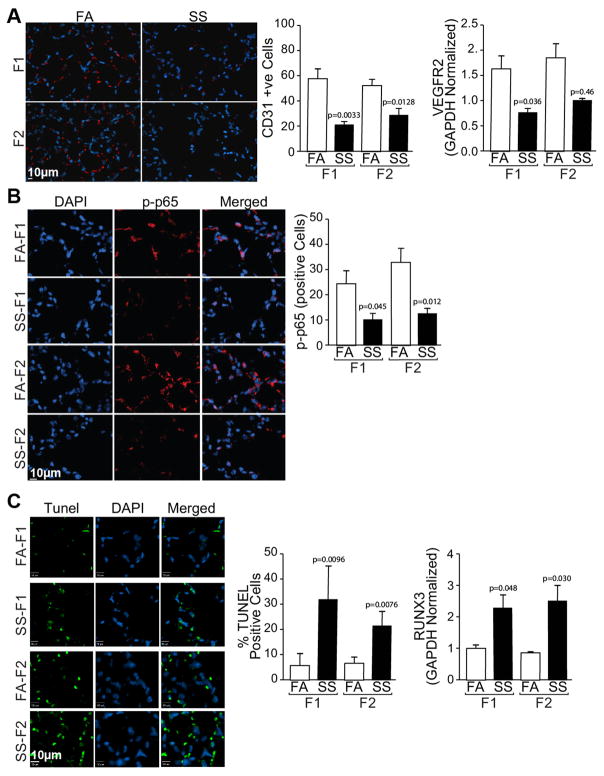

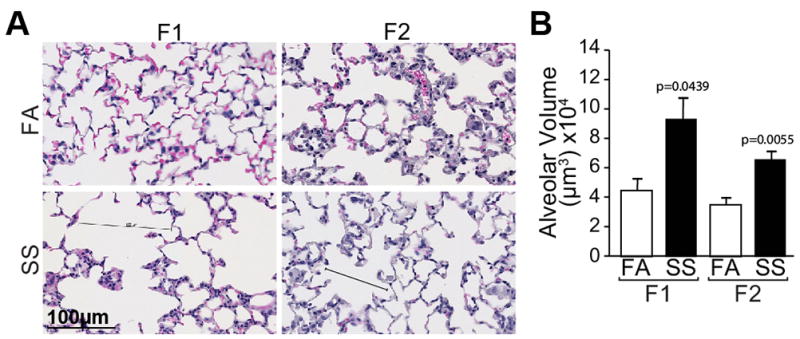

Gestational SS causes alveolar simplification and impairs angiogenesis in F1 and F2 lungs

Angiogenesis is critical for normal lung alveolarization (31) and we have shown that gestational SS impairs alveolarization and angiogenesis in the neonatal lung (17). We carried out similar experiments in F2 animals and compared the results with control (FA) and SS-exposed F1 lungs. H&E staining for alveolar architecture (Fig. 3A) and alveolar volumes (Fig. 3B) of 10 weeks old lungs showed that, compared to FA, gestational SS significantly increases the alveolar volumes in F1 and F2 lungs. Moreover, as detected by immunohistochemistry for CD31 (Fig. 4A, left panel) and its quantitation (Fig. 4A, middle panel) and qPCR analysis of VEGFR2 (Fig. 4A, right panel), gestational SS impairs angiogenesis in both F1 and F2 lungs. Normal expression of NF-κB is critical for angiogenesis of the developing lung (Patel et al., 2005) and, as seen by IHC staining (Fig. 4B, left panel) and its quantitation (Fig. 4B, right panel), nuclear expression of p65-NF-κB is strongly downregulated in the SS-exposed F1 and F2 lungs. In addition, as detected by TUNEL staining (Fig. 4C, left panel) and its quantitation (Fig. 4C, middle panel), gestational SS increases the number of apoptotic cells within the alveoli of F1 and F2 progenies. The transcription factor RUNX3 promotes apoptosis (32) and, as measured by qPCR analysis, its expression is markedly upregulated in gestationally SS-exposed F1 and F2 lungs (Fig. 4C right panel). These data suggest that the effects of gestational SS on lung angiogenesis, alveolar development, and apoptosis are transmitted from F1 to F2 generation.

Fig. 3. Gestational SS-induced alveolar simplification is exhibited by F1 and F2 lungs.

A: H&E stained lung sections (5 um) from F1 and F2 mice; B: quantitation of alveolar volumes. The results are representative of animal responses from two different sets of inhalation exposures. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n =6 –17/group. FA = filtered air, SS = secondhand cigarette smoke; F1: first generation; F2 second generation.

Fig. 4. Gestational SS-exposure downregulates angiogenesis, VGEFR2, p65-NFκB, and upregulates apoptosis in F1 and F2 lungs.

A: Lung sections were stained with anti-CD3 antibody (left anel) and the red florescent cells were quantitated microscopically (middle panel); expression of VEGEFR2 was done by qPCR analysis (right panel).B: Lung sections were stained with phosphorylated(p)-anti-p-65 antibody (left panel) and p-65-positive cells were quantitated (right panel). C: Lung sections were stained for TUNEL-positive cells using In Situ cell Death Detection kit (left panel) and quantitated microscopically (middle panel); RUNX3 levels were determined by quantitative RT-PCR using total lung RNA. Where indicated slides were counterstained with DAPI to visualize nuclei. Results are representative of animal responses from two different sets of inhalation exposures. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 5–7/group. FA = filtered air, SS = secondhand cigarette smoke; F1: first generation; F2 second generation.

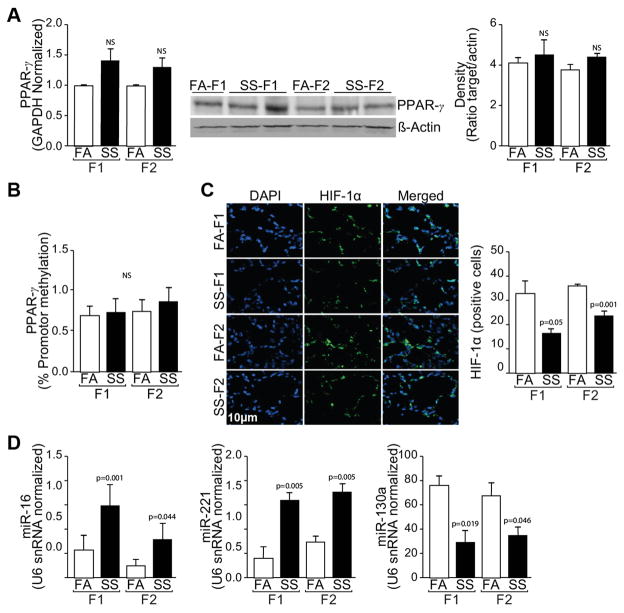

Gestational SS decreases HIF-1α but not PPARγ expression in F1 and F2 progenies

It has recently been demonstrated in rats that daily perinatal injection of nicotine aggravates asthmatic responses transgenerationally and the effects are associated with decreased lung expression of PPARγ through increased PPARγ promoter methylation (29, 30, 33). To ascertain whether gestational SS exposure affected PPARγ in F1 and/or F2 lungs, we measured the mRNA and protein levels as well as promoter methylation of PPARγ in gestationally FA- and SS-exposed mouse lungs. Surprisingly, qPCR and Western blot analysis indicated that gestational SS did not significantly alter either the mRNA or protein levels of PPARγ in F1 or F2 lungs (Fig. 5A left and middle panel). Similarly, pyrosequencing analysis did not show significant changes in the methylation of PPARγ promoter (Fig. 5B). On the other hand, there was non-significant trend for higher levels of PPARγ mRNA and protein in gestationally SS-exposed F1 and F2 lungs. These results suggest that the asthma phenotype induced by gestational SS-exposures in F1 and F2 lungs is not associated with epigenetic changes in PPARγ levels.

Fig. 5. Effects of gestational SS on PPARγ, HIF-1α and miRs in F1 and F2 lungs.

A: Quantitation of PPARγ by quantitative RT-PCR of total lung RNA (left panel); Western blot analysis of lung homogenates for PPARγ (middle panel) and ratio of PPARγ : actin from the Western blots by densitometry (right panel). B: percent methylation of PPARγ promoter (left panel C: Immunofluorescent staining of lung sections for HIF-1α with DAPI for nuclear staining (left panel) and quantitation of HIF-1α-positive cells (right panel). D Quantitative RT-PCR analysis for miR-16 (left panel), miR-221 (middle panel), and miR-130a (right panel). Data are normalized with snRNA U6. The results are representative of animal responses from two different sets of inhalation exposures. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 5–7/group. FA = filtered air, SS = secondhand cigarette smoke; F1: first generation; F2 second generation.

HIF-1α controls angiogenesis as well as apoptosis and is significantly decreased in gestationally SS-exposed animals (17). We quantitated HIF-1α levels in the airways of F1 and F2 animals by immunohistochemistry. Results show that HIF-1α levels are significantly decreased in the airways of gestationally SS-exposed F1 and F2 animals (Fig. 5C left and right panel). Thus, decreased HIF-1α levels are associated with asthma phenotype in F1 and F2 animals from gestationally SS-exposed mice.

Gestational SS affects miRs in F1 and F2 lungs that regulate angiogenesis and apoptosis

Gestational SS affects apoptosis and angiogenesis in the mouse lung (17, 21) and increasing evidence suggests that miRs regulate these processes. We ascertained the effects of gestational SS on some critical miRs that are known to regulate angiogenesis and apoptosis. miR 16 and miR 221 are known to increase apoptosis and autophagy and decrease proliferation and angiogenesis in various cell types (34–36). These miRs are increased in gestationally SS-exposed F1 and F2 mice (Fig. 5D left and middle panel). Conversely, the expression of miR-130a that targets the proapoptotic factor RUNX3 and inhibits autophagy, and stimulates angiogenesis and cell proliferation (37, 38), is significantly decreased in F1 and F2 lungs from gestationally SS-exposed mice (Fig 5D, right panel). These results indicate that gestational SS affects the expression of pro- and anti-apoptotic/angiogenic miRs and these effects are transmitted to the next generation.

DISCUSSION

In recent decades, AA among children has been inexplicably increasing and asthma burden in the US exceeds $56 billion/year (39). In utero exposure to CS, prone children to allergic asthma and BPD (16, 18, 19). The asthma inducing effects of in utero CS exposure are associated with smoking by either parent, suggesting that exposure to environmental/SS during pregnancy has the potential to affect AA in children. Moreover the grandmothers who smoke, elevate the risk of asthma in their nonsmoking granddaughters (26), highlighting the potential of transgenerational transmission of asthmatic phenotype induced by gestational SS exposure. Similarly, in a rat model of allergic asthma, Dr. Rehan’s laboratory clearly demonstrated that the pro-asthmatic effects of perinatal nicotine injections were transmitted to F2 and F3 progenies and the effects were dependent on PPARγ and moderated by PPARγ agonists (29, 33). We have previously shown that gestational exposure of mice to SS induces AA and BPD-like phenotypes in mice and the effects are dependent on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and blocked by the allosteric antagonist of nAChRs mecamylamine (17, 21). Following gestational SS, the proasthmatic and lung architectural changes in F1 mice are associated with Th2 polarization, increased apoptosis and decreased angiogenesis in the neonatal lung. In addition, gestational SS-induces changes in F1 lungs that are strongly correlated with desensitization of nAChRs and decreased levels of HIF-1α (17).

Results presented herein clearly suggest that the effects of gestational SS on AA and BPD are transmitted to F2 generation; this includes a striking increase in methacholine-induced airway hyperresponsiveness and a strong decrease in lung compliance in F1 and F2 progenies. Asthma is mainly a Th2 inflammatory lung disease (40) and Th2 polarization is a hallmark of AA and asthma exacerbations (41). In mice, in utero exposure to CS causes strong Th2 polarization associated with significant increases in Th2 cytokines/Th2 transcription factors and significant decreases in Th1 cytokines/Th1 transcription factors (20).To understand the mechanism by which gestational SS regulates transgenerational transmission of asthma phenotype, we analyzed allergen-induced changes in Th1 and Th2 cytokines/transcription factors in F1 and F2 progenies derived from control and gestationally SS-exposed dams. Results indicate that SS exposure is associated with higher expression of Th2 cytokines/transcription factors such as IL-4, IL-13, and GATA3 and lower expression of Th1 cytokines/transcription factors (e.g., IFN-γ, T-bet). In addition, our preliminary unpublished results show that gestational SS causes a significant decrease in the lung TNF-α and increase in IL-10 in F1 and F2; IL-10 suppress Th1 responses through inhibition of TNF-α and IFN-γ (42). In addition, gestational SS-induced BPD-like changes in F1 to F2 lungs are associated with decreased angiogenesis (lower expression of CD31, VEGF, and VEGFR2). Hypoxic conditions and HIF-1α are important for angiogenesis and normal fetal development (43); gestational SS downregulates HIF-1α and increases airway/alveolar epithelial cell apoptosis in both F1 and F2 lungs.

Because 100% of F2 animals tested (n = 17), derived from gestationally SS-exposed F1 progeny, exhibited exacerbated asthma and BPD-like phenotype, ruled out the Mendelian mode of inheritance, suggesting that the transmission requires epigenetic mechanisms. Maternal smoking has been shown to cause DNA methylation and differential expression of thousands of genes some of which are related to asthma (25). Moreover, proasthmatic effects of perinatal nicotine (I mg/kg) were shown to be passed on to F2 and F3 generations and linked to decreased PPARγ activity through PPARγ gene methylation in alveolar fibroblasts (28, 30). Therefore, we determined whether gestational SS altered the expression of PPARγ mRNA and protein, or affected its phosphorylation or methylation. Surprisingly, none of these PPARγ parameters were significantly decreased in the lungs of F1 or F2 animals derived from gestationally SS-exposed dams. Moreover, although, PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone was shown to moderate the proasthmatic effects of perinatal nicotine administration in rats (33,), PPARγ ligands such as rosiglitazone, pioglitazone, and troglitazone are known to inhibit VEGF-induced angiogenesis (44, 45), but lung VEGF and lung angiogenesis are significantly decreased in the gestationally SS-exposed animals (17 and data presented herein). On the other hand, there is a trend for higher expression of PPARγ in F1 and F2 lungs from gestationally SS-derived animals and, as discussed later, miR-130a that targets PPARγ (46) is decreased in these lungs. Thus, it is highly unlikely that the proasthmatic transgenerational effects of gestational SS are regulated by PPARγ activity. Therefore, it is conceivable that, while both perinatal nicotine injections (29) and gestational SS inhalation (21) promote asthma in F1 and F2 progenies, the two treatments may employ distinct mechanisms.

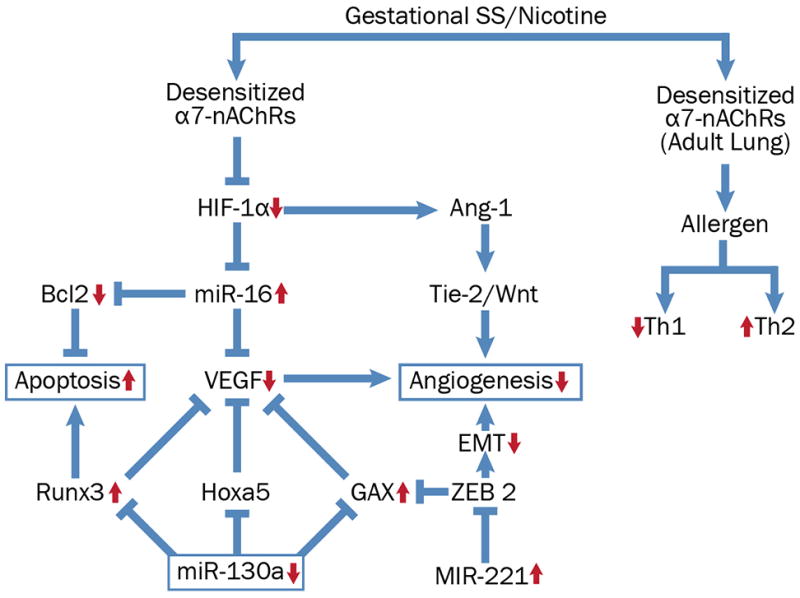

One of the major epigenetic mechanisms for regulation of gene expression involves changes in levels of miRs (47); these non-coding RNAs bind and degrade specific mRNAs (48). Nicotine normally promotes cell proliferation through inhibition of apoptosis and stimulation of angiogenesis through upregulation of HIF-1α (49); however, gestational SS downregulates HIF-1α in the lung through desensitization of nAChRs (17, 21). Because gestational SS-induced changes in HIF-1α are intimately correlated with asthma and BPD in both F1 and F2, we analyzed the expression of some miRs that are known to control angiogenesis and apoptosis and affect HIF-1α levels in the lung (Fig. 6). Of the miRs tested, we observed significant changes in the expression of 3 miRs in both SS-derived F1 and F2 lungs. The expression of miR-16 and miR-221 was significantly elevated and these miRs target and decrease proapoptotic factors such as BIM-BAX, BAK (50–52); BIM, BIK, BAX, and BAK are increased in gestationally SS-exposed lungs (17). ZEB2 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal-transition (EMT) through downregulation of p53 and upregulation of Akt (53, 54) and inhibits the anti-angiogenic factor GAX (52). Although, as yet, we do not have direct evidence to show that gestational SS affects ZEB2; however, GAX and p53 are strongly upregulated and Akt is downregulated in SS-derived F1/F2 lungs (17 and data presented herein). Moreover, our preliminary results suggest that EMT is suppressed in SS-exposed lungs (Singh et al., unpublished results). Gestational SS decreases miR-130a that targets the anti-angiogenic factor GAX and the proapoptotic factor RUNX3 (37, Lee et al., 2015); both GAX and RUNX3 are increased in F1 and F2 lungs from gestationally SS-exposed mice. Furthermore, RUNX transcription factors have been implicated in predicting asthma associated with maternal smoking (55). miR-130a also promotes VEGF synthesis indirectly by targeting VEGF inhibitor Hoxa5. Although as yet we don’t know whether Hoxa5 is upregulated in gestationally SS-exposed lungs, levels of VEGF are markedly reduced in both F1 and F2 lungs. It should be emphasized that we only examined the miRNAs that have been linked to HIF-1α; however, it is likely that gestational SS affects other miRNAs, whose potential effects on AA and BPD remain to be ascertained.

Fig. 6. A tentative schematic diagram showing possible pathways eliciting the effect of gestational SS exposure.

Desensitization of nAChRs during gestational nicotine/SS-exposure affects HIF-1α levels increasing apoptosis and decreasing angiogenesis in the lung. The expression of pro-apoptotic miRs (miR-16 and miR-221) is significantly elevated in gestationally SS-exposed. Gestational SS-exposure decreases miR-130a that targets the anti-angiogenic factor GAX and the proapoptotic factor RUNX3 (both GAX and RUNX3 are increased in F1 and F2 lungs). Red arrows indicate established responses with upward arrows indicating significant increase and downward arrows indicating significant decrease in the indicated response. Components in the pathway that are without the arrows predict the indicated response but remain hitherto unproven.

Nicotine/CS normally downregulates Th2 responses (e.g., allergic asthma, ulcerative colitis) and exacerbates Th1 diseases (56, 57); however, desensitization of nAChRs during gestational nicotine/SS exposure might reverse this pattern (17). In keeping with this prediction, F1 and F2 lungs from gestationally SS-exposed animals show higher Th2 and lower Th1 responses. Together our results suggest that the effects of gestational SS on AA and BPD are transmitted from F1 to F2 generations through epigenetic mechanisms, and changes in specific miRs might contribute to this response by regulating the nAChR-HIF-1α pathway. These possibilities are presented as a tentative schematic pathway in Fig. 6. Participation of other epigenetic mechanisms in regulating AA and BPD responses to gestational nicotine, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications can’t be ruled out at this time.

Acknowledgments

Authors are thankful to Ms. Elise Calvillo for her help with the graphics.

Footnotes

The research was funded in part by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command grant (GW093005) and an NIH grant (HL125000).

References

- 1.Barker DJ, Hales CN, Fall CH, Osmond C, Phipps K, Clark PM. Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia (syndrome X): relation to reduced fetal growth. Diabetologia. 1993;36(1):62–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00399095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aerts L, Van Assche FA. Animal evidence for the transgenerational development of diabetes mellitus. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38(5–6):894–903. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Otterdijk SD, Michels KB. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in mammals: how good is the evidence? FASEB J. 2016;30(7):2457–2465. doi: 10.1096/fj.201500083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hylkema MN, Blacquière MJ. Intrauterine effects of maternal smoking on sensitization, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6(8):660–662. doi: 10.1513/pats.200907-065DP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazurek JM, England LJ. Cigarette Smoking Among Working Women of Reproductive Age-United States, 2009–2013. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):894–899. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinkerton KE, Joad JP. The mammalian respiratory system and critical windows of exposure for children’s health. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl 3):457–462. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein RT, Martinez FD. Asthma phenotypes in childhood: lessons from an epidemiological approach. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2004;5(2):155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiFranza JR, Aligne CA, Weitzman M. Prenatal and postnatal environmental tobacco smoke exposure and children’s health. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4 Suppl):1007–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott JE. Review:The pulmonary surfactant: impact of tobacco smoke and related compounds on surfactant and lung development. Tobacco Induced Diseases. 2004;2(1):3–25. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-2-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh SP, Barrett EG, Kalra R, Razani-Boroujerdi S, Langley V, Kurup RJ, Tesfaigzi Y, Sopori ML. Prenatal cigarette smoke decreases lung cAMP andincreases airway hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(3):342–347. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200211-1262OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rehan VK, Asotra K, Torday JS. The effects of smoking on the developing lung: insights from a biologic model for lung development, homeostasis, and repair. Lung. 2009;187(5):281–289. doi: 10.1007/s00408-009-9158-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sekhon HS, Keller JA, Benowitz NL, Spindel ER. Prenatal nicotine exposure alters pulmonary function in newborn rhesus monkeys. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(6):989–994. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.6.2011097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh SP, Mishra NC, Rir-Sima-Ah J, Campen M, Kurup V, Razani-Boroujerdi S, Sopori ML. Maternal exposure to secondhand cigarette smoke primes the lung for induction of phosphodiesterase-4D5 isozyme and exacerbated Th2 responses: rolipram attenuates the airway hyperreactivity and muscarinic receptor expression but not lung inflammation and atopy. J Immunol. 2009;183(3):2115–2121. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vrijheid M, Martinez D, Aguilera I, Bustamante M, Ballester F, Estarlich M, Fernandez-Somoano A, Guxens M, Lertxundi N, Martinez MD, Tardon A, Sunyer J. INMA Project. Indoor air pollution from gas cooking and infant neurodevelopment. Epidemiology. 2012;23(1):23–32. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31823a4023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antonucci R, Contu P, Porcella A, Atzeni C, Chiappe S. Intrauterine smoke exposure: a new risk factor for bronchopulmonary dysplasia? J Perinat Med. 2004;32(3):272–277. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2004.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez S, Garcia-Meric P, Millet V, Aymeric-Ponsonnet M, Alagha K, Dubus JC. Tobacco smoke in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(7):943–848. doi: 10.1007/s00431-015-2491-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh SP, Chand HS, Gundavarapu S, Saeed AI, Langley RJ, Tesfaigz Y, Mishra NC, Sopori ML. HIF-1α Plays a Critical Role in the Gestational Sidestream Smoke-Induced Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Mice. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137757. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuman Å, Hohmann C, Orsini N, Pershagen G, Eller E, Kjaer HF, Gehring U, Granell R, Henderson J, Heinrich J, Lau S, Nieuwenhuijsen M, Sunyer J, Tischer C, Torrent M, Wahn U, Wijga AH, Wickman M, Keil T, Bergström A ENRIECO Consortium. Maternal smoking in pregnancy and asthma in preschool children: a pooled analysis of eight birth cohorts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(10):1037–1043. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0501OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xepapadaki P, Manios Y, Liarigkovinos T, Grammatikaki E, Douladiris N, Kortsalioudaki C, Papadopoulos NG. Association of passive exposure of pregnant women to environmental tobacco smoke with asthma symptoms in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2009;20(5):423–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2008.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh SP, Gundavarapu S, Peña-Philippides JC, Rir-Sima-ah J, Mishra NC, Wilder JA, Langley RJ, Smith KR, Sopori ML. Prenatal secondhand cigarette smoke promotes Th2 polarization and impairs goblet cell differentiation and airway mucus formation. J Immunol. 2011;187(9):4542–4552. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh SP, Gundavarapu S, Smith KR, Chand HS, Saeed AI, Mishra NC, Hutt J, Barrett EG, Husain M, Harrod KS, Langley RJ, Sopori ML. Gestational exposure of mice to secondhand cigarette smoke causes bronchopulmonary dysplasia blocked by the nicotinic receptor antagonist mecamylamine. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121(8):957–964. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1306611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caniggia I, Mostachfi H, Winter J, Gassmann M, Lye SJ, Kuliszewski M, Post M. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates the biological effects of oxygen on human trophoblast differentiation through TGFbeta(3) J Clin Invest. 2000;105(5):577–587. doi: 10.1172/JCI8316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chakraborty D, Rumi MA, Soares MJ. Nk cells, hypoxia and trophoblast cell differentiation. Cell cycle. 2012;11:2427–2430. doi: 10.4161/cc.20542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mannino DM, Homa DM, Pertowski CA, Ashizawa A, Nixon LL, Johnson CA, Ball LB, Jack E, Kang DS. Surveillance for asthma--United States, 1960–1995. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1998;47(1):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joubert BR, Felix JF, Yousefi P, Bakulski KM, Just AC, Breton C, Reese SE, Markunas CA, Richmond RC, Xu CJ, Küpers LK, Oh SS, Hoyo C, Gruzieva O, Söderhäll C, Salas LA, Baïz N, Zhang H, Lepeule J, Ruiz C, Ligthart S, Wang T, Taylor JA, Duijts L, Sharp GC, Jankipersadsing SA, Nilsen RM, Vaez A, Fallin MD, Hu D, Litonjua AA, Fuemmeler BF, Huen K, Kere J, Kull I, Munthe-Kaas MC, Gehring U, Bustamante M, Saurel-Coubizolles MJ, Quraishi BM, Ren J, Tost J, Gonzalez JR, Peters MJ, Håberg SE, Xu Z, van Meurs JB, Gaunt TR, Kerkhof M, Corpeleijn E, Feinberg AP, Eng C, Baccarelli AA, Benjamin Neelon SE, Bradman A, Merid SK, Bergström A, Herceg Z, Hernandez-Vargas H, Brunekreef B, Pinart M, Heude B, Ewart S, Yao J, Lemonnier N, Franco OH, Wu MC, Hofman A, McArdle W, Van der Vlies P, Falahi F, Gillman MW, Barcellos LF, Kumar A, Wickman M, Guerra S, Charles MA, Holloway J, Auffray C, Tiemeier HW, Smith GD, Postma D, Hivert MF, Eskenazi B, Vrijheid M, Arshad H, Antó JM, Dehghan A, Karmaus W, Annesi-Maesano I, Sunyer J, Ghantous A, Pershagen G, Holland N, Murphy SK, DeMeo DL, Burchard EG, Ladd-Acosta C, Snieder H, Nystad W, Koppelman GH, Relton CL, Jaddoe VW, Wilcox A, Melén E, London SJ. DNA Methylation in Newborns and Maternal Smoking in Pregnancy: Genome-wide Consortium Meta-analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98(4):680–696. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li YF, Langholz B, Salam MT, Gilliland FD. Maternal and grandmaternal smoking patterns are associated with early childhood asthma. Chest. 2005;127(4):1232–1241. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.4.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breton CV, Siegmund KD, Joubert BR, Wang X, Qui W, Carey V, Nystad W, Håberg SE, Ober C, Nicolae D, Barnes KC, Martinez F, Liu A, Lemanske R, Strunk R, Weiss S, London S, Gilliland F, Raby B. Asthma BRIDGE consortium. Prenatal tobacco smoke exposure is associated with childhood DNA CpG methylation. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rehan VK, Liu J, Naeem E, Tian J, Sakurai R, Kwong K, Akbari O, Torday JS. Perinatal nicotine exposure induces asthma in second generation offspring. BMC Med. 2012;10:129. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rehan VK, Liu J, Sakurai R, Torday JS. Perinatal nicotine-induced transgenerational asthma. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;305(7):L501–507. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00078.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gong M, Liu J, Sakurai R, Corre A, Anthony S, Rehan VK. Perinatal nicotine exposure suppresses PPARγ epigenetically in lung alveolar interstitial fibroblasts. Mol Genet Metab. 2015;114(4):604–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alvira CM. Review: Aberrant Pulmonary Vascular Growth and Remodeling in Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Front Med (Lausanne) 2016;3:21. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2016.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhai FX, Liu XF, Fan RF, Long ZJ, Fang ZG, Lu Y, Zheng YJ, Lin DJ. RUNX3 isinvolved in caspase-3-dependent apoptosis induced by a combination of 5-aza-CdR and TSA in leukaemia cell lines. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138(3):439–449. doi: 10.1007/s00432-011-1113-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J, Sakurai R, Rehan VK. PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone reverses perinatal nicotine exposure-induced asthma in rat offspring. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;308(8):L788–796. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00234.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chatterjee A, Chattopadhyay D, Chakrabarti G. MiR-16 targets Bcl-2 in paclitaxel-resistant lung cancer cells and overexpression of miR-16 along with miR-17 causes unprecedented sensitivity by simultaneously modulating autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Signal. 2015;27(2):189–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y, Zhang B, Li W, Wang L, Yan Z, Li H, Yao Y, Yao R, Xu K, Li Z. MiR-15a/16 regulates the growth of myeloma cells, angiogenesis and antitumor immunity by inhibiting Bcl-2, VEGF-A and IL-17 expression in multiple myeloma. Leuk Res. 2016;49:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khella HW, Butz H, Ding Q, Rotondo F, Evans KR, Kupchak P, Dharsee M, Latif A, Pasic MD, Lianidou E, Bjarnason GA, Yousef GM. miR-221/222 Are Involved in Response to Sunitinib Treatment in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Mol Ther. 2015;23(11):1748–1758. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee SH, Jung YD, Choi YS, Lee YM. Targeting of RUNX3 by miR-130a and miR-495 cooperatively increases cell proliferation and tumor angiogenesis in gastric cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6(32):33269–33278. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu Q, Meng S, Liu B, Li MQ, Li Y, Fang L, Li YG. MicroRNA-130a regulates autophagy of endothelial progenitor cells through Runx3. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;41(5):351–357. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barnett SB, Nurmagambetov TA. Costs of asthma in the United States: 2002–2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(1):145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, Jia G, Abbas AR, Ellwanger A, Koth LL, Arron JR, Fahy JV. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(5):388–395. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0392OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kabata H, Moro K, Koyasu S, Asano K. Review: Group 2 innate lymphoid cells and asthma. Allergol Int. 2015;64(3):227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oswald IP, Wynn TA, Sher A, James SL. Interleukin 10 inhibits macrophage microbicidal activity by blocking the endogenous production of tumor necrosis factor alpha required as a costimulatory factor for interferon gamma-induced activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(18):8676–8680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimoda LA, Semenza GL. Review: HIF and the lung: role of hypoxia-inducible factors in pulmonary development and disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(2):152–156. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201009-1393PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aljada A, O’Connor L, Fu YY, Mousa SA. PPAR gamma ligands, rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, inhibit bFGF- and VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2008;11(4):361–367. doi: 10.1007/s10456-008-9118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park BC, Thapa D, Lee JS, Park SY, Kim JA. Troglitazone inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenic signaling via suppression of reactive oxygen species production and extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylation in endothelial cells. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;111(1):1–12. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08305fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu L, Wang J, Lu H, Zhang G, Liu Y, Wang J, Zhang Y, Shang H, Ji H, Chen X, Duan Y, Li Y. MicroRNA-130a and -130b enhance activation of hepatic stellate cells by suppressing PPARγ expression: A rat fibrosis model study. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;465(3):387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu W, Wang F, Yu Z, Xin F. Review: Epigenetics and Cellular Metabolism. Genet Epigenet. 2016;8:43–51. doi: 10.4137/GEG.S32160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krützfeldt J, Stoffel M. Review: MicroRNAs: a new class of regulatory genes affecting metabolism. Cell Metab. 2006;4(1):9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shi D, Guo W, Chen W, Fu L, Wang J, Tian Y, Xiao X, Kang T, Huang W, Deng W. Nicotine promotes proliferation of human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by regulating α7AChR, ERK, HIF-1α and VEGF/PEDF signaling. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43898. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cimmino A, Calin GA, Fabbri M, Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Shimizu M, Wojcik SE, Aqeilan RI, Zupo S, Dono M, Rassenti L, Alder H, Volinia S, Liu CG, Kipps TJ, Negrini M, Croce CM. miR-15 and miR-16 induce apoptosis by targeting BCL2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(39):13944–13949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506654102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ye Z, Hao R, Cai Y, Wang X, Huang G. Knockdown of miR-221 promotes the cisplatin-inducing apoptosis by targeting the BIM-Bax/Bak axis in breast cancer. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(4):4509–4515. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen Y, Banda M, Speyer CL, Smith JS, Rabson AB, Gorski DH. Regulation of the expression and activity of the antiangiogenic homeobox gene GAX/MEOX2 by ZEB2 and microRNA-221. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(15):3902–3913. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01237-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim T, Veronese A, Pichiorri F, Lee TJ, Jeon YJ, Volinia S, Pineau P, Marchio A, Palatini J, Suh SS, Alder H, Liu CG, Dejean A, Croce CM. p53 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition through microRNAs targeting ZEB1 and ZEB2. J Exp Med. 2011;208(5):875–883. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Z, Yang J, Fisher T, Xiao H, Jiang Y, Yang C. Akt activation is responsible for enhanced migratory and invasive behavior of arsenic-transformed human bronchial epithelial cells. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(1):92–97. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haley KJ, Lasky-Su J, Manoli SE, Smith LA, Shahsafaei A, Weiss ST, Tantisira K. RUNX transcription factors: association with pediatric asthma and modulated by maternal smoking. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301(5):L693–701. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00348.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mishra NC, Rir-Sima-Ah J, Langley RJ, Singh SP, Peña-Philippides JC, Koga T, Razani-Boroujerdi S, Hutt J, Campen KC, Kim M, Tesfaigzi Y, Sopori ML. Nicotine primarily suppresses lung Th2 but not goblet cell and muscle cell responses to allergens. J Immunol. 2008;180(11):7655–7663. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kikuchi H, Itoh J, Fukuda S. Chronic nicotine stimulation modulates the immuneresponse of mucosal T cells to Th1-dominant pattern via nAChR by upregulation of Th1-specific transcriptional factor. Neurosci Lett. 2008;432(3):217–221. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]