Abstract

The pseudouridine at position 43 in vertebrate U2 snRNA is one of the most conserved post-transcriptional modifications of spliceosomal snRNAs; the equivalent position is pseudouridylated in U2 snRNAs in different phyla including fungi, insects, and worms. Pseudouridine synthase Pus1p acts alone on U2 snRNA to form this pseudouridine in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and mouse. Furthermore, in S. cerevisiae, Pus1p is the only pseudouridine synthase for this position. Using an in vivo yeast cell system, we tested enzymatic activity of Pus1p from the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, the worm Caenorhabditis elegans, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, and the frog Xenopus tropicalis. We demonstrated that Pus1p from C. elegans has no enzymatic activity on U2 snRNA when expressed in yeast cells, whereas in similar experiments, position 44 in yeast U2 snRNA (equivalent to position 43 in vertebrates) is a genuine substrate for Pus1p from S. cerevisiae, S. pombe, Drosophila, Xenopus, and mouse. However, when we analyzed U2 snRNAs from Pus1 knockout mice and the pus1Δ S. pombe strain, we could not detect any changes in their modification patterns when compared to wild-type U2 snRNAs. In S. pombe, we found a novel box H/ACA RNA encoded downstream from the RPC10 gene and experimentally verified its guide RNA activity for positioning Ψ43 and Ψ44 in U2 snRNA. In vertebrates, we showed that SCARNA8 (also known as U92 scaRNA) is a guide for U2-Ψ43 in addition to its previously established targets U2-Ψ34/Ψ44.

Keywords: modification guide RNA, pseudouridine, Pus1p, U2 snRNA

INTRODUCTION

The isomerization of uridine to pseudouridine is the most abundant post-transcriptional modification found in stable RNA molecules. When pseudouridine was discovered in early RNA studies, it was even designated as a “fifth” nucleoside (Cohn and Volkin 1951; Davis and Allen 1957). First identified in abundant RNAs, such as rRNAs, tRNAs, and U snRNAs, pseudouridine has since been found in almost all types of RNAs, including mRNAs, snoRNAs, long noncoding RNAs, and telomerase RNA (Zhao et al. 2007; Carlile et al. 2014; Lovejoy et al. 2014; Schwartz et al. 2014). Pseudouridine synthases are enzymes that catalyze pseudouridine formation. Based on sequence similarities, pseudouridine synthases have been classified into six distinct families (Mueller and Ferré-D'Amaré 2009; Spenkuch et al. 2014). These enzymes act either alone or with a guide RNA, known as a box H/ACA snoRNA. In the latter case, target recognition relies on specific base-pairing between the substrate and the guide RNA. Thus, a single pseudouridine synthase, Cbf5/NAP57/dyskerin, functions at different positions and in different RNAs (for review, see Yu and Meier 2014).

Eukaryotic spliceosomal snRNAs are extensively modified (Karijolich and Yu 2010). For instance, numerous pseudouridines are found in all vertebrate snRNAs and at least 14 pseudouridines were detected in human U2 snRNA alone (Deryusheva et al. 2012). Most snRNA modifications in higher eukaryotes depend on guide RNAs (Karijolich and Yu 2010; Deryusheva and Gall 2013; Adachi and Yu 2014). However, in budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), snRNAs contain only nine pseudouridines: In addition to six constitutive pseudouridines, two in U1 snRNA, three in U2 snRNA, and one in U5 snRNAs (Massenet et al. 1999), there are three inducible pseudouridines, two in U2 snRNA (Wu et al. 2011) and one in U6 snRNA (Basak and Query 2014). Modification mechanisms have been identified for all five pseudouridines in U2 snRNA, both constitutive (Massenet et al. 1999; Ma et al. 2003, 2005) and inducible (Wu et al. 2011), and for the inducible pseudouridine in U6 snRNA (Basak and Query 2014). Four of these six positions are modified by two stand-alone pseudouridine synthases, Pus1p and Pus7p.

Pus1p, a member of the TruA pseudouridine synthase family, acts on several types of RNA substrates. Besides U2 and U6 snRNAs in S. cerevisiae (Massenet et al. 1999; Basak and Query 2014), it modifies uridines in many different tRNAs (Motorin et al. 1998; Chen and Patton 1999; Hellmuth et al. 2000; Patton and Padgett 2003; Patton et al. 2005; Behm-Ansmant et al. 2006), in the mouse steroid receptor RNA activator (Zhao et al. 2007), and in a set of mRNAs (Carlile et al. 2014; Lovejoy et al. 2014; Schwartz et al. 2014). In humans, mutations in the PUS1 gene are associated with mitochondrial myopathy and sideroblastic anemia (MLASA). Although Pus1p is a site-specific enzyme, it lacks strict sequence recognition requirements (Sibert and Patton 2012). Pus1p's from different species, although highly conserved structurally, differ in their ability to catalyze pseudouridylation of certain conserved positions in tRNAs (Behm-Ansmant et al. 2006). As for U2 snRNA, in S. cerevisiae Pus1p is the only pseudouridylation machinery that modifies position 44 at the branch point recognition region; in vertebrates the equivalent position is 43, and this pseudouridine is one of the most conserved pseudouridines across all eukaryotic species. Whereas mouse Pus1p can pseudouridylate U2 snRNA when expressed in the pus1Δ yeast strain (Behm-Ansmant et al. 2006), the activity of Pus1p from other species is rather ambiguous (Hellmuth et al. 2000; Patton and Padgett 2003). Using an in vivo yeast cell system, we test here Pus1p from different phyla: a mammal (mouse), an amphibian (Xenopus tropicalis), an insect (Drosophila melanogaster), a worm (Caenorhabditis elegans), and two fungi (S. cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe). We show species-specific differences in the ability of Pus1p to modify U2 snRNA. For instance, C. elegans Pus1p appears to lack activity on U2 snRNA when expressed in yeast cells. At the same time, our data demonstrate redundant Pus1p-dependent and guide RNA-mediated pseudouridylation of U2 snRNA at position 43 in vertebrates and in S. pombe.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

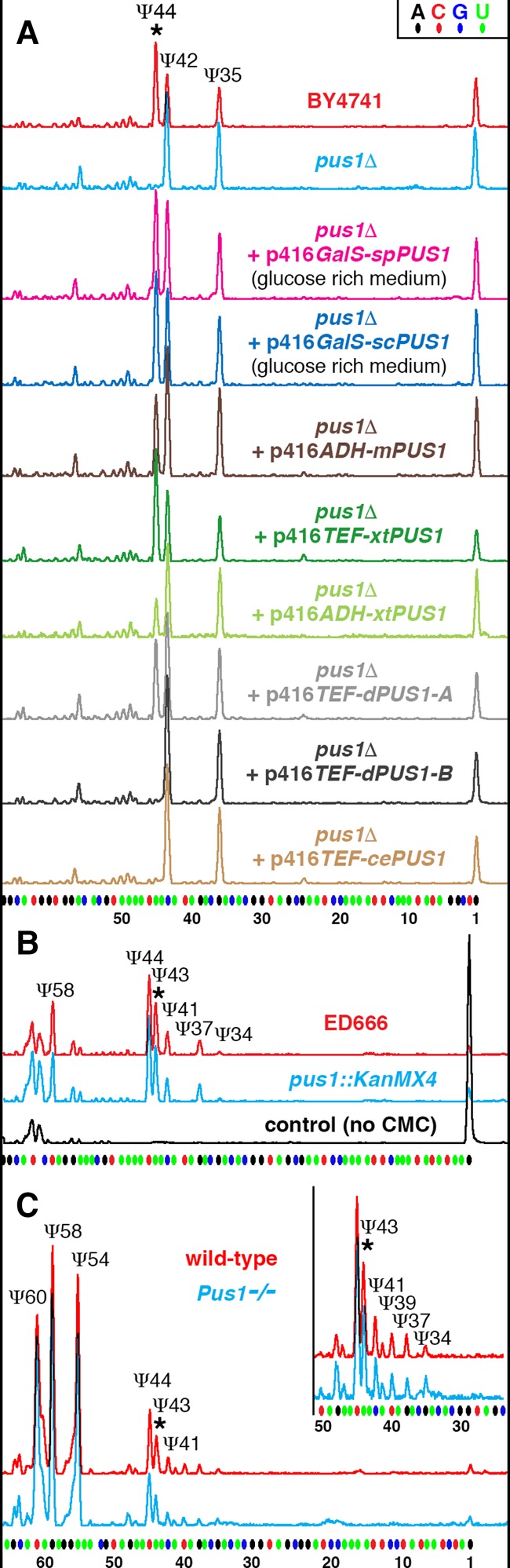

Genes encoding Pus1p have been annotated in many species. Based on data from yeast S. cerevisiae and mouse (Massenet et al. 1999; Behm-Ansmant et al. 2006), Pus1p is generally assumed to modify U2 snRNA, yet Pus1p from other species has never been tested directly for enzymatic activity on U2 snRNA. In fact, C. elegans U2 snRNA has not been considered as a cePus1p substrate, because in mutant worms, the absence of Pus1p activity on tRNAs had no effect on U2 snRNA modification (Patton and Padgett 2003). Based on complementation analysis and sequence similarity, PUS1 has been earlier identified in S. pombe (Hellmuth et al. 2000); more recently, the pus1Δ strain has become available from the S. pombe gene deletion collection (Kim et al. 2010). Pus1p is the only pseudouridine synthase in S. cerevisiae that is active on U2 snRNA at position 44 (Fig. 1A). However, the pus1Δ strain of S. pombe shows a U2 snRNA modification pattern identical to its parental ED666 “wild-type” strain (Fig. 1B). It is worth noting here that we verified the PUS1 deletion by PCR and sequencing the amplified fragments. These observations suggest that U2 snRNA can be modified in C. elegans and S. pombe by a Pus1p-independent mechanism.

FIGURE 1.

Pus1p enzymatic activity on U2 snRNA in different species. (A) S. cerevisiae U2 snRNA is normally pseudouridylated at positions 35, 42, and 44 (wild-type BY4741 strain, red trace). In a Pus1p-deficient S. cerevisiae strain, the pseudouridine at position 44 is missing (pus1Δ, blue trace). Pus1p from fission yeast S. pombe (spPus1p, magenta trace) when expressed in S. cerevisiae pus1Δ strain modifies yeast U2 snRNA as efficiently as S. cerevisiae Pus1p (scPus1p, dark blue trace). Mouse, Xenopus, and Drosophila Pus1p enzymes can rescue pseudouridylation at position 44 in yeast S. cerevisiae pus1Δ strain, yet a much higher level of expression is required (mPus1p, dark brown trace; xtPus1p, green traces; dPus1p-A/CG4159-PA, gray trace). Compare the efficiency of pseudouridylation when Xenopus Pus1p is expressed from plasmids with different promoter activities: ADH promoter (light green trace) and TEF promoter (dark green trace). Pus1p from C. elegans and the longer isoform of Drosophila Pus1p could not modify yeast U2 snRNA even when overexpressed (cePus1p, light brown trace; dPus1p-B/CG4159-PB, black trace). (B) U2 snRNA pseudouridylation mapping in S. pombe wild-type (ED666, red trace) and pus1Δ (pus1::KanMX4, blue trace) strains. U2 snRNA from the pus1Δ strain is modified at all the normal positions, including position 43. (C) U2 snRNA pseudouridylation mapping in wild-type (red trace) and Pus1 knockout (Pus1−/−, blue trace) mice. Inset in C zooms in on the branch point recognition region; note no differences between wild-type and mutant strains in their U2 snRNA modification patterns. Stars indicate peaks corresponding to pseudouridine at position 44 in S. cerevisiae U2 snRNA or equivalent position 43 in S. pombe and mouse U2 snRNA.

Pus1 knockout mice have been recently generated. In these mice, Pus1p-dependent modification of tRNAs was shown to be missing, but U2 snRNA was not tested (Mangum et al. 2016). We analyzed U2 snRNA pseudouridylation in the Pus1 knockout mice and their wild-type siblings using RNA samples kindly provided by Jeffrey Patton and Diego Altomare (University of South Carolina). Again we did not detect any differences between wild-type and mutant mice in their U2 snRNA modification patterns (Fig. 1C). While spPus1p and cePus1p enzymatic activity on U2 snRNA has not yet been verified (Hellmuth et al. 2000; Patton and Padgett 2003), U2 snRNA was identified as a genuine substrate for mPus1p (Behm-Ansmant et al. 2006).

We decided to test the enzymatic activity of Pus1p from S. pombe and several higher eukaryote species in the pus1Δ S. cerevisiae strain. We chose X. tropicalis, D. melanogaster, and C. elegans Pus1p. Mouse and S. cerevisiae Pus1p served as positive controls in these experiments. The activity on U2 snRNA was evident for Pus1p from all examined species, except for C. elegans (Fig. 1A). However, in contrast to yeast Pus1p, mouse, Xenopus, and Drosophila enzymes were less efficient. To restore Ψ44 in U2 snRNA, they needed to be overexpressed, whereas both scPus1p and spPus1p could rescue pseudouridylation of this position in the pus1Δ S. cerevisiae strain even when expressed at a low level from a leaky GalS promoter. Expression levels of exogenous Pus1p were verified by Western blots using HA-tagged versions of the Pus1p expression constructs; beforehand, we tested that the HA-tag did not affect Pus1p enzymatic activity.

Intriguingly, the predicted PUS1 gene in Drosophila, CG4159, produces two alternatively spliced variants, of which only the shorter isoform, CG4159-PA, can modify U2 snRNA (Fig. 1A). The difference between the two isoforms of Drosophila Pus1p is small—a short 32 aa extension at the N terminus. Nevertheless, the web server IUPred (http://iupred.enzim.hu), which predicts intrinsically unstructured regions (Dosztányi et al. 2005), suggests that the N terminus of the longer isoform no longer forms a typical disordered tail (Czudnochowski et al. 2013), but instead is incorporated in a large globular domain. In mammals, short and long isoforms of Pus1p have also been reported, but these variants do not change the unstructured nature of the N terminus. For now, we do not know if both isoforms of Pus1p are expressed in Drosophila, even though the two variants of PUS1 mRNA are equally abundant. However, it is tempting to speculate that expression of the inactive, alternatively spliced isoform of Pus1p could represent a mechanism for fine-tuning U2 snRNA pseudouridylation at the branch point recognition region and consequently regulating pre-mRNA splicing efficiency.

We should emphasize here that we consider only positive results as meaningful in this study; one could find many reasons why a protein lacks enzymatic activity when expressed in a heterologous system. Our data clearly demonstrate that Pus1p is an enzyme for U2 snRNA pseudouridylation in the yeasts S. cerevisiae and S. pombe, the fruit fly Drosophila, as well as mammals and amphibians. At the same time, pseudouridylation of U2 snRNA at position 43 can occur independently of Pus1p, at least in S. pombe and mouse (Fig. 1B,C). Redundant modification activity has been previously observed for pseudouridylation of position 34 in Xenopus U2 snRNA, when the guide RNA pugU2-34/44 was tested in the Xenopus oocyte system (Zhao et al. 2002). The corresponding guide RNA (SCARNA8 or U92) is highly conserved across species (Darzacq et al. 2002; Lestrade and Weber 2006; Deryusheva and Gall 2013). Later, the guide RNA-independent activity on U2 snRNA at position 34 was identified for the single-protein pseudouridine synthase Pus7p from Xenopus, human, and Drosophila (YT Yu laboratory; S Deryusheva and JG Gall, unpubl.). Thus, we were not surprised that position 43 also could be modified by two independent mechanisms. The remaining problem was to identify the Pus1p-independent modification machinery at that position.

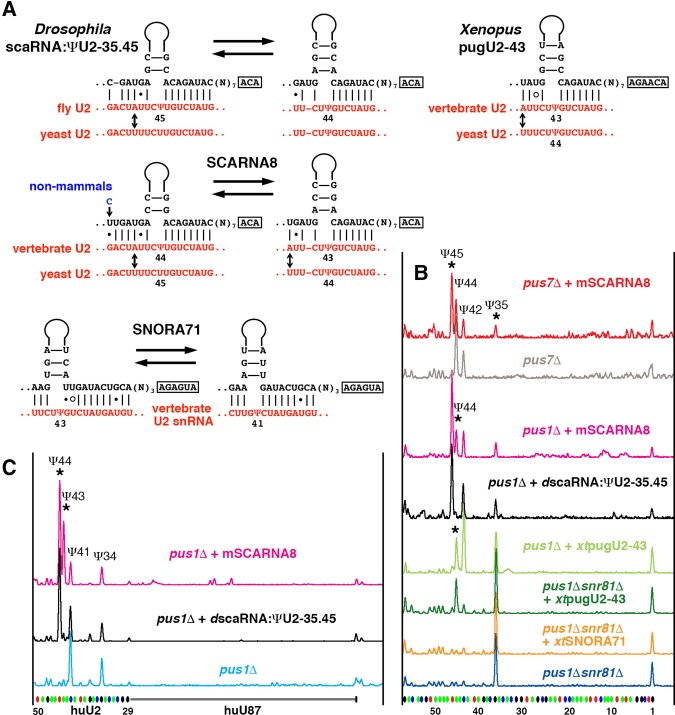

In our previous study of Xenopus oocytes, we found that depletion of SCARNA8 (also called pugU2-34/44 and U92) resulted in depletion of pseudouridylation not only at position 44, but at position 43 as well (Deryusheva and Gall 2013). However, when we tested the orthologous Drosophila guide RNA in the yeast cell system, we could only detect modification activity on yeast U2 snRNA at positions 35 and 45 (equivalent to positions 34 and 44 in vertebrates). With the new evidence for redundant pseudouridylation activity on U2 snRNA, we reanalyzed potential base-pairing of Drosophila scaRNA:ΨU2-35.45 and vertebrate SCARNA8 with U2 snRNA (Fig. 2A). In fact, the ability of vertebrate SCARNA8 to direct modification at positions 43 and 44 is reasonably stronger than Drosophila scaRNA:ΨU2-35.45. Thus, as predicted, mouse SCARNA8 induced the pseudouridylation of yeast U2 snRNA at positions 35 and 45 when expressed in the pus7Δ strain (Fig. 2B, top two traces), and pseudouridylation of yeast U2 snRNA at positions 45 and 44 when expressed in the pus1Δ strain (positions 45, 44, and 35 correspond to positions 44, 43, and 34 in vertebrates) (Fig. 2B, magenta trace). The yeast U2 snRNA sequence at the branch point recognition region is slightly different from that of vertebrates, which makes base-pairing weaker (the mismatch is depicted by an arrow in Fig. 2A). Thus the modification of endogenous yeast U2 snRNA is probably less efficient. Pseudouridylation of the target positions became more prominent when an artificial RNA was tested, which contained a sequence identical to vertebrate U2 snRNA (Fig. 2C, magenta trace). In the same optimized substrate, Drosophila scaRNA:ΨU2-35.45 could not induce modification at the position corresponding to position 43 in vertebrate U2 snRNA (Fig. 2C, black trace). Thus we positively identified SCARNA8 as a guide for U2 pseudouridylation at position 43 in vertebrates, which makes SCARNA8 a triple guide for the highly conserved positions 34, 43, and 44 in the branch point recognition region. It is puzzling that Drosophila scaRNA:ΨU2-35.45 has the same base-pairing with yeast U2 snRNA for positioning U2-Ψ44 as a vertebrate SCARNA8 (Fig. 2A), yet the Drosophila RNA is not functional at this position (Fig. 2B, black trace). The efficiency might depend on the binding affinity with the substrate as a whole, not with each modifying position separately; thus, in vertebrate SCARNA8, stronger binding in the alternative configuration to position U2-Ψ45 might facilitate efficient sliding to position U2-Ψ44. We still need to learn more about guide RNA functionality, especially in the cases of complex multitarget pseudouridylation pockets.

FIGURE 2.

Vertebrate guide RNAs for U2 snRNA pseudouridylation at position 43. (A) Predicted base-pairing with the U2 snRNA branch point recognition region. Arrows indicate nucleotides in U2 snRNA that differ between yeast and higher eukaryotes. (B,C) Testing guide RNA activities in a yeast cell system. (B) Modification of yeast U2 snRNA mediated by Drosophila scaRNA:ΨU2-35.45, mouse SCARNA8, Xenopus SNORA71, and pugU2-43 guide RNAs expressed in the pus7Δ, pus1Δ, and pus1Δsnr81Δ strains. (C) Modification of the vertebrate branch point recognition region (nucleotides 29–52) inserted into an artificial U87-derived RNA, mediated by mouse SCARNA8 and Drosophila scaRNA:ΨU2-35.45 guide RNAs expressed in the pus1Δ strain. Stars indicate the guide RNA-induced modifications.

Multiple guide RNAs are typically assigned to the most important modified positions. Pseudouridines at the branch point recognition region of U2 snRNA represent such functionally crucial modifications (Yu et al. 1998; Zhao and Yu 2004, 2007; Yang et al. 2005). Yet SCARNA8 is encoded by a single-copy gene in most vertebrate genomes. To find other potential guide RNAs for pseudouridylation of position 43 in U2 snRNA, we screened known vertebrate box H/ACA RNAs for antisense elements specific to the U2 snRNA branch point recognition region. SNORA71 stood out in this analysis because its 5′-terminal pseudouridylation pocket could base pair with U2 snRNA (Fig. 2A). Since both positions 43 and 41 can be modified by base-pairing within the same pseudouridylation pocket, we used the S. cerevisiae double mutant pus1Δsnr81Δ to test SNORA71 guide activity on U2 snRNA. When SNORA71 was expressed in this mutant strain, it could not restore pseudouridylation of the endogenous yeast U2 snRNA (Fig. 2B, two bottom traces). Moreover, it did not support modification of an artificial substrate identical to the branch point recognition region of vertebrate U2 snRNA. Even though we did not demonstrate SNORA71 modification activity on U2 snRNA, we could not rule it out by our experiments.

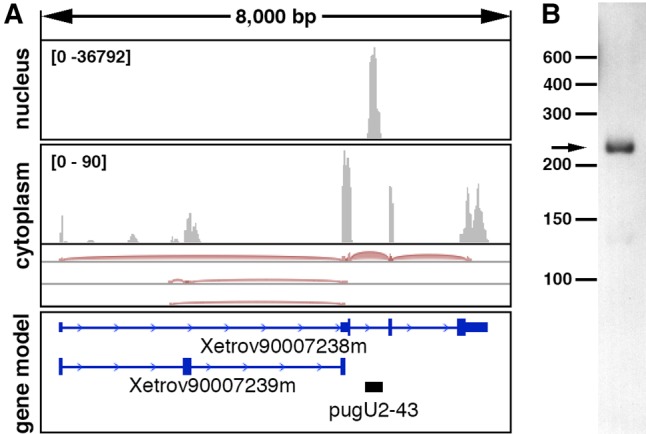

Another candidate for pugU2-43 guide RNA was identified in our recent bioinformatic search for novel snoRNAs in Xenopus oocytes. A novel box H/ACA RNA was found in intron 2 of the annotated transcript Xetrov90007238m (Fig. 3A). We verified its expression by RACE and Northern blot analysis (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, we showed that this guide RNA inefficiently modified yeast U2 snRNA at position 44 (equivalent to position 43 in vertebrate U2 snRNA) (Fig. 2A,B). Taken together, our data demonstrate that in vertebrates, position 43 in U2 snRNA can be modified by both guide RNA-independent (Pus1p) and guide RNA-mediated mechanisms; out of the three candidate RNAs we tested, SCARNA8 is the most likely U2-Ψ43 specific guide RNA.

FIGURE 3.

Expression of the novel Xenopus pugU2-43 RNA detected by RNA deep-sequencing of oocyte nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA (A) and by Northern blot analysis of X. tropicalis liver RNA (B). (A) IGV browser view of RNA deep-sequencing reads (PRJNA302326) previously generated in our laboratory (Talhouarne and Gall 2014) and aligned to the X. tropicalis 9.0 genome. The black bar in the gene model panel indicates pugU2-43 RNA newly identified in the nuclear fraction.

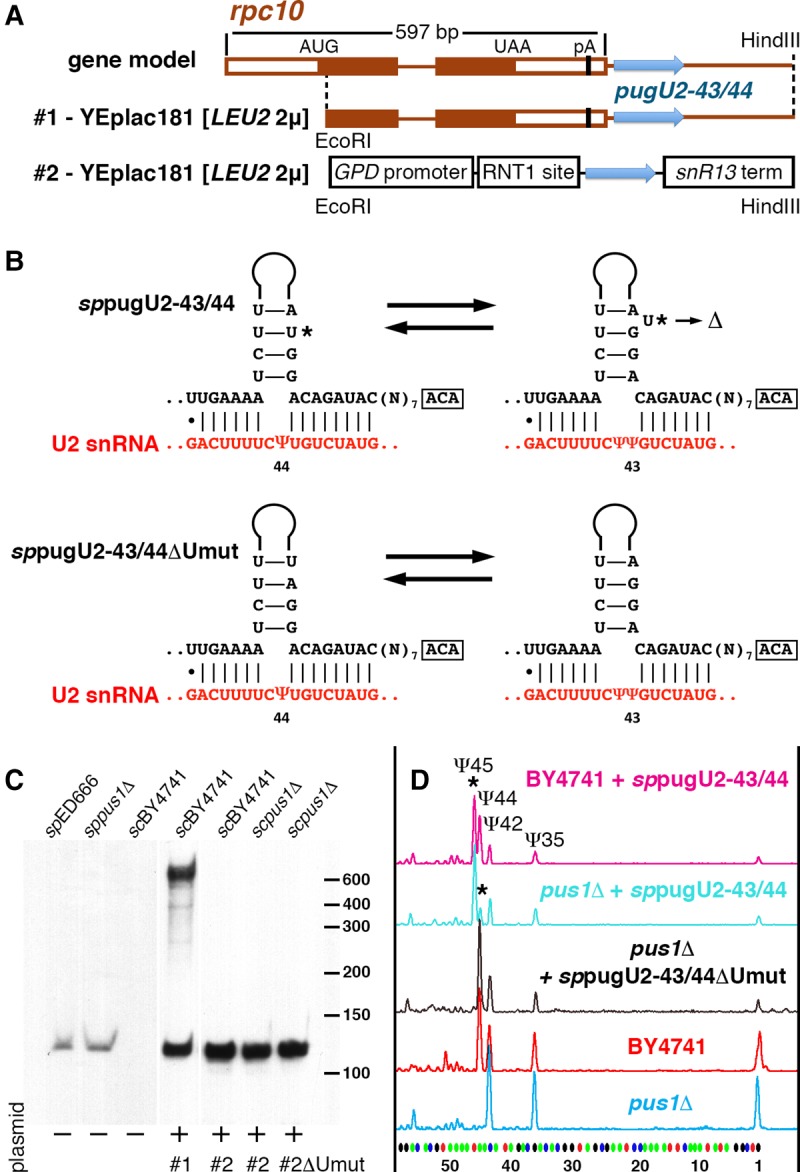

Despite the hundreds of noncoding RNAs annotated in the fully sequenced S. pombe genome (http://www.pombase.org), the list of snoRNAs is far from complete; in fact, no guide RNAs for U2 snRNA modification have been identified so far. Using a nucleotide blast database search, we found a putative U2 snRNA-specific guide RNA downstream from the RPC10 gene (Fig. 4A). Standard 5′ and 3′ RACE and Northern blot analysis confirmed the expression of this RNA in S. pombe (Fig. 4C). The nucleotide sequence was deposited to the Third Party Annotation Section of the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession number BK009173. We predict that the newly identified box H/ACA RNA can direct modification of U2 snRNA at positions 43 and 44 (Fig. 4B). Unfortunately, we could not recover a haploid clone with a deletion of this guide RNA: Either the pugU2-43/44 is an essential RNA in S. pombe or the genomic manipulations in close proximity to the RPC10 gene affect the expression of RPC10, a well-characterized essential gene. As an alternative for further functional assays, we cloned a 695-bp fragment of S. pombe genomic DNA containing the newly identified guide RNA into YEplac181 vector without a promoter (Fig. 4A) and transformed S. cerevisiae cells with this plasmid. The S. cerevisiae transformants showed (i) expression of the fully processed S. pombe guide RNA (Fig. 4C) and (ii) pseudouridylation of U2 snRNA at position 45, equivalent to position 44 in S. pombe U2 snRNA (Fig. 4D). This demonstrated that the newly identified S. pombe RNA is a genuine guide RNA for U2 snRNA pseudouridylation. More importantly, expression of this guide RNA in the pus1Δ S. cerevisiae strain induced modification of both position 45 and 44, although position 44 was modified less efficiently than in the wild-type strain (Fig. 4D). The pseudouridylation pocket of S. pombe pugU2-43/44 RNA has a one-nucleotide bulge in the upper stem when base paired with S. pombe U2 snRNA for positioning Ψ43 (Fig. 4B, star). It has been noticed previously in an S. cerevisiae cell system that stability of the upper stem structure in a pseudouridylation pocket-bearing hairpin might significantly influence guide RNA functionality (Xiao et al. 2009). We deleted this one nucleotide and expected to see a slight increase in guide activity on Ψ44, when the mutated guide RNA was expressed in the pus1Δ S. cerevisiae strain. Strikingly, the one-nucleotide deletion, which stabilized the configuration for Ψ44 positioning, completely abolished Ψ45 formation (Fig. 4D, black trace). These observations indicate that preexisting pseudouridylation at position 44 inhibits the formation of pseudouridine at position 45. Similar inhibition was observed previously when we tested Drosophila scaRNA:ΨU2-35.45 in the yeast cell system (Deryusheva and Gall 2013). If crosstalk between different positions within heavily modified regions is a general phenomenon, a mechanism for coordinated positioning of post-transcriptional modifications deserves special investigation.

FIGURE 4.

S. pombe guide RNA for U2 snRNA pseudouridylation at positions 43 and 44. (A) Scheme of the endogenous gene and expression constructs for S. pombe pugU2-43/44 RNA. (B) Predicted structural alterations and base-pairing with U2 snRNA within the 3′-terminal pseudouridylation pocket of sppugU2-43/44 RNA. Star indicates uridine in the upper stem that was deleted in the mutant variant sppugU2-43/44ΔUmut. (C) Northern blot analysis of endogenous expression of pugU2-43/44 RNA in S. pombe strains and exogenous expression from plasmids (two constructs shown in A) in S. cerevisiae. All samples were run on the same gel and probed simultaneously. The first three lanes are shown with a longer exposure than the remaining four lanes. (D) Probing the modification guide RNA activities of sppugU2-43/44 in the BY4741 wild-type and the pus1Δ mutant strains of S. cerevisiae. Stars indicate modifications that are induced by sppugU2-43/44 RNA expression.

Conclusions

We found two types of pseudouridine synthase that catalyze the formation of U2-Ψ43 (or 44) in yeasts, Drosophila, and vertebrates. One is the stand-alone enzyme Pus1p, which acts on U2 snRNA in yeasts, Drosophila, and vertebrates. At the same time, another pseudouridine synthase Cbf5/Dyskerin and a guide RNA are found in S. pombe and vertebrates. Based on this redundancy, we postulate that alterations in U2 snRNA modification do not contribute to the mitochondrial myopathy and sideroblastic anemia (MLASA) phenotype associated with PUS1 mutations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Guide RNA sequence analysis

To identify the box H/ACA guide RNA that modifies U2 snRNA at positions 44 and 43 in S. pombe, we used the short sequence BLASTN search on PomBase (http://genomebrowser.pombase.org/Schizosaccharomyces_pombe/blastview); the query sequence was ggACAGATACgg (3′-side of the pseudouridylation pocket, highly conserved across species). Hits were screened for the TGAAAA sequence (expected yeast-specific 5′-side of the pocket) upstream of the query sequence and the ACA box downstream from the query sequence. The computationally identified guide RNA was verified by Northern blot analysis and 5′ and 3′ RACE.

Expression in yeast cells

Yeast strains used in this study were the following: S. cerevisiae BY4741, which served as the wild-type strain; mutant strains pus7Δ, pus1Δ, and pus1Δsnr81Δ were provided by Yi-Tao Yu (University of Rochester Medical Center); S. pombe wild-type strain 972, the mutant strain pus1::KanMX4, and its parental strain ED666 were provided by Peter Espenshade (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine).

The construct for expression of mouse Pus1p in yeast (Behm-Ansmant et al. 2006) was kindly provided by Dr. Yuri Motorin (CNRS-Université de Lorraine). The insert originally cloned into p416GALS vector was cut with XbaI and XhoI and sub-cloned into p416ADH vector. To clone PUS1 ORFs from yeast, the annotated ORFs of S. cerevisiae PUS1/YPL212C and S. pombe PUS1/SPCC126.03 were amplified from genomic DNA of BY4741 and 972 yeast strains using proofreading DNA polymerase Q5 (New England Biolabs). RT-PCR was used to obtain PUS1 ORFs from X. tropicalis, C. elegans, and D. melanogaster. Total RNA isolated from different tissues (oocytes and liver of X. tropicalis) or from whole organisms (wild-type strain of C. elegans and y w strain of D. melanogaster) was used as the templates for RT-PCR. Appropriate restriction sites were added with primers to clone the PUS1 coding sequences into various yeast expression vectors: p416GALS, p416ADH, p416TEF. Two annotated isoforms of CG4159 mRNA predicted to encode Pus1p in Drosophila (http://flybase.org) were amplified and cloned: One isoform produces a 410 aa protein (CG4159-PA), and the other gives rise to a 442 aa protein with an extra 32 aa at the N terminus (CG4159-PB). The C. elegans Pus1p coding sequence was as previously identified (Patton and Padgett 2003). Since disordered N- and C-terminal residues of human Pus1p were found not essential for enzymatic activity (Czudnochowski et al. 2013), we additionally made HA-tagged versions of the Pus1p expression constructs. This allowed us to monitor expression of the exogenous Pus1p. To add one copy of HA-tag to the C terminus of Pus1p, the corresponding in-frame sequence was included in the reverse primers.

Drosophila scaRNA:ΨU2-35.45 expression constructs were previously generated (Deryusheva and Gall 2013). To express mouse U92/SCARNA8, Xenopus pugU2-43, and S. pombe pugU2-43/44 guide RNAs, the corresponding coding sequences were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA and cloned into YEplac181 [LEU2 2μ] vector containing a GPD promoter, an RNT1 cleavage site, and an snR13 terminator; the vector was constructed in the Yi-Tao Yu Laboratory (University of Rochester Medical Center) (Huang et al. 2011). Additionally, a fragment of S. pombe genomic DNA containing most of the RPC10 protein coding sequence, the 3′-UTR and a downstream 232-bp region was cloned into YEplac181 between EcoRI and HindIII restriction sites (see Fig. 4A). The Xenopus SNORA71 coding sequence was introduced by replacement of snR191 in the fragment of the yeast NOG2 gene cloned into p415GAL1 vector. To make an artificial RNA substrate identical to the branch point recognition region of vertebrate U2 snRNA, a fragment of human U2 snRNA (nucleotides 29–52) was inserted into the human U87 scaRNA and a yeast expression construct was generated as previously described (Deryusheva and Gall 2013). PCR-based mutagenesis and overlap-extension PCR were used to make mutant and chimeric RNA-expressing constructs.

Junction regions and entire inserts were sequenced in all recombinant plasmids. Plasmids were introduced into yeast cells using standard lithium acetate methods. Selective SC and EMM media were used to grow S. cerevisiae and S. pombe, respectively, with either glucose or galactose as a source of sugar.

RNA extraction

Hot acid phenol extraction was used to isolate RNA from yeast cells. TRIzol reagent was used to extract RNA from X. tropicalis oocytes and liver, whole D. melanogaster adults, and whole C. elegans worms. After phase separation, RNA was purified using the Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep kit (Zymo Research). All manipulations with X. tropicalis were performed according to established and approved IACUC protocols.

Northern blot

Total RNA was separated on 8% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gels and transferred onto a nylon membrane (Zeta Probe, Bio-Rad). Digoxigenin (Dig)-labeled PCR probes were used to detect endogenous and overexpressed guide RNAs. Hybridization was performed at 42°C in DIG Easy Hyb buffer (Roche). The hybridized probes were visualized using an anti-Dig antibody conjugated with alkaline phosphatase and the chemiluminescent substrate CDP-Star (Roche) according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Western blot analysis

For protein extraction, yeast cells were centrifuged, resuspended in 0.1 N sodium hydroxide, and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Samples were pelleted, resuspended in the 2× sample buffer, and boiled for 5–6 min. Proteins were separated on Tris–SDS acrylamide gels, transferred onto a PVDF membrane, and probed with rat anti-HA mAb 3F10 (Roche) at a final concentration of 40 ng/mL in 5% nonfat dry milk. A secondary anti-rat antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Jackson ImmunoResearch) was used at a dilution of 1:40,000. SuperSignal West Dura chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific) was used to detect HRP.

RNA modification analysis

A primer extension-based modification mapping method was used to analyze pseudouridylation of yeast and mouse U2 snRNA (Kiss and Jády 2004; Deryusheva and Gall 2009). Fluorescently labeled oligonucleotides specific for vertebrate and S. cerevisiae U2 snRNA and for U87-based artificial substrate RNA were previously described ( Deryusheva and Gall 2013; Deryusheva et al. 2012). To analyze S. pombe U2 snRNA, a new 6-FAM-labeled oligonucleotide was designed: [106–129] AAGCCAGAGGCTTTCCAACTCAAA. To detect pseudouridines, test RNA samples were treated first with CMC [N-cyclohexyl-N′-(2-morpholinoethyl) carbodiimide metho-p-toluene sulfonate] (Sigma-Aldrich) for 20–30 min and then with pH 10.4 sodium carbonate buffer for 3–4 h at 37°C. Primer extension was performed using either AMV-RT (New England Biolabs) or EpiScript RT (Epicentre) at 0.5 mM dNTP concentration. Reaction products were purified by ethanol precipitation; dry pellets were dissolved in formamide, mixed with the GeneScan-500 LIZ Size Standard and separated on an ABI3730xl capillary electrophoresis instrument (Applied Biosystems).

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. J.G.G. is an American Cancer Society Professor of Developmental Genetics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the following individuals for kindly supplying reagents: Yi-Tao Yu, University of Rochester Medical Center, for S. cerevisiae mutant strains and expression vectors; Jeffrey Patton and Diego Altomare, University of South Carolina, for RNA samples from Pus1 KO mice; Yuri Motorin, CNRS-Université de Lorraine, for mouse PUS1 construct p416GalS-mPUS1; Peter Espenshade, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, for S. pombe strains; Geraldine Seydoux, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, for wild-type C. elegans worms. This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (grant number R01 GM33397 to J.G.G.).

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.061226.117.

REFERENCES

- Adachi H, Yu YT. 2014. Insight into the mechanisms and functions of spliceosomal snRNA pseudouridylation. World J Biol Chem 5: 398–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basak A, Query CC. 2014. A pseudouridine residue in the spliceosome core is part of the filamentous growth program in yeast. Cell Rep 8: 966–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behm-Ansmant I, Massenet S, Immel F, Patton JR, Motorin Y, Branlant C. 2006. A previously unidentified activity of yeast and mouse RNA:pseudouridine synthases 1 (Pus1p) on tRNAs. RNA 12: 1583–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlile TM, Rojas-Duran MF, Zinshteyn B, Shin H, Bartoli KM, Gilbert WV. 2014. Pseudouridine profiling reveals regulated mRNA pseudouridylation in yeast and human cells. Nature 515: 143–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Patton JR. 1999. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian pseudouridine synthase. RNA 5: 409–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn WE, Volkin E. 1951. Nucleoside-5′-phosphates from ribonucleic acid. Nature 167: 483–484. [Google Scholar]

- Czudnochowski N, Wang AL, Finer-Moore J, Stroud RM. 2013. In human pseudouridine synthase 1 (hPus1), a C-terminal helical insert blocks tRNA from binding in the same orientation as in the Pus1 bacterial homologue TruA, consistent with their different target selectivities. J Mol Biol 425: 3875–3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzacq X, Jády BE, Verheggen C, Kiss AM, Bertrand E, Kiss T. 2002. Cajal body-specific small nuclear RNAs: a novel class of 2′-O-methylation and pseudouridylation guide RNAs. EMBO J 21: 2746–2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis FF, Allen FW. 1957. Ribonucleic acids from yeast which contain a fifth nucleotide. J Biol Chem 227: 907–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deryusheva S, Gall JG. 2009. Small Cajal body-specific RNAs of Drosophila function in the absence of Cajal bodies. Mol Biol Cell 20: 5250–5259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deryusheva S, Gall JG. 2013. Novel small Cajal-body-specific RNAs identified in Drosophila: probing guide RNA function. RNA 19: 1802–1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deryusheva S, Choleza M, Barbarossa A, Gall JG, Bordonné R. 2012. Post-transcriptional modification of spliceosomal RNAs is normal in SMN-deficient cells. RNA 18: 31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosztányi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P, Simon I. 2005. IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics 21: 3433–3434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmuth K, Grosjean H, Motorin Y, Deinert K, Hurt E, Simos G. 2000. Cloning and characterization of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe tRNA:pseudouridine synthase Pus1p. Nucleic Acids Res 28: 4604–4610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Karijolich J, Yu YT. 2011. Post-transcriptional modification of RNAs by artificial Box H/ACA and Box C/D RNPs. Methods Mol Biol 718: 227–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karijolich J, Yu YT. 2010. Spliceosomal snRNA modifications and their function. RNA Biol 7: 192–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DU, Hayles J, Kim D, Wood V, Park HO, Won M, Yoo HS, Duhig T, Nam M, Palmer G, et al. 2010. Analysis of a genome-wide set of gene deletions in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nat Biotechnol 28: 617–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss T, Jády BE. 2004. Functional characterization of 2′-O-methylation and pseudouridylation guide RNAs. Methods Mol Biol 265: 393–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lestrade L, Weber MJ. 2006. snoRNA-LBME-db, a comprehensive database of human H/ACA and C/D box snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 34: D158–D162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy AF, Riordan DP, Brown PO. 2014. Transcriptome-wide mapping of pseudouridines: pseudouridine synthases modify specific mRNAs in S. cerevisiae. PLoS ONE 9: e110799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Zhao X, Yu YT. 2003. Pseudouridylation (Psi) of U2 snRNA in S. cerevisiae is catalyzed by an RNA-independent mechanism. EMBO J 22: 1889–1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Yang C, Alexandrov A, Grayhack EJ, Behm-Ansmant I, Yu YT. 2005. Pseudouridylation of yeast U2 snRNA is catalyzed by either an RNA-guided or RNA-independent mechanism. EMBO J 24: 2403–2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangum JE, Hardee JP, Fix DK, Puppa MJ, Elkes J, Altomare D, Bykhovskaya Y, Campagna DR, Schmidt PJ, Sendamarai AK, et al. 2016. Pseudouridine synthase 1 deficient mice, a model for mitochondrial myopathy with sideroblastic anemia, exhibit muscle morphology and physiology alterations. Sci Rep 6: 26202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massenet S, Motorin Y, Lafontaine DL, Hurt EC, Grosjean H, Branlant C. 1999. Pseudouridine mapping in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae spliceosomal U small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) reveals that pseudouridine synthase Pus1p exhibits a dual substrate specificity for U2 snRNA and tRNA. Mol Cell Biol 19: 2142–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motorin Y, Keith G, Simon C, Foiret D, Simos G, Hurt E, Grosjean H. 1998. The yeast tRNA:pseudouridine synthase Pus1p displays a multisite substrate specificity. RNA 4: 856–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller EG, Ferré-D'Amaré AR. 2009. Pseudouridine formation, the most common transglycosylation in RNA. In DNA and RNA modification enzymes: structure, mechanism, function and evolution (ed. Grosjean H), pp. 363–376. Landes Bioscience, Austin, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Patton JR, Padgett RW. 2003. Caenorhabditis elegans pseudouridine synthase 1 activity in vivo: tRNA is a substrate, but not U2 small nuclear RNA. Biochem J 372: 595–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JR, Bykhovskaya Y, Mengesha E, Bertolotto C, Fischel-Ghodsian N. 2005. Mitochondrial myopathy and sideroblastic anemia (MLASA): missense mutation in the pseudouridine synthase 1 (PUS1) gene is associated with the loss of tRNA pseudouridylation. J Biol Chem 280: 19823–19828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Bernstein DA, Mumbach MR, Jovanovic M, Herbst RH, Leon-Ricardo BX, Engreitz JM, Guttman M, Satija R, Lander ES, et al. 2014. Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals widespread dynamic-regulated pseudouridylation of ncRNA and mRNA. Cell 159: 148–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibert BS, Patton JR. 2012. Pseudouridine synthase 1: a site-specific synthase without strict sequence recognition requirements. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 2107–2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spenkuch F, Motorin Y, Helm M. 2014. Pseudouridine: still mysterious, but never a fake (uridine)! RNA Biol 11: 1540–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talhouarne GJ, Gall JG. 2014. Lariat intronic RNAs in the cytoplasm of Xenopus tropicalis oocytes. RNA 20: 1476–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Xiao M, Yang C, Yu YT. 2011. U2 snRNA is inducibly pseudouridylated at novel sites by Pus7p and snR81 RNP. EMBO J 30: 79–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao M, Yang C, Schattner P, Yu YT. 2009. Functionality and substrate specificity of human box H/ACA guide RNAs. RNA 15: 176–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, McPheeters DS, Yu YT. 2005. Psi35 in the branch site recognition region of U2 small nuclear RNA is important for pre-mRNA splicing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 280: 6655–6662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu YT, Meier UT. 2014. RNA-guided isomerization of uridine to pseudouridine–pseudouridylation. RNA Biol 11: 1483–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu YT, Shu MD, Steitz JA. 1998. Modifications of U2 snRNA are required for snRNP assembly and pre-mRNA splicing. EMBO J 17: 5783–5795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Yu YT. 2004. Pseudouridines in and near the branch site recognition region of U2 snRNA are required for snRNP biogenesis and pre-mRNA splicing in Xenopus oocytes. RNA 10: 681–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Yu YT. 2007. Incorporation of 5-fluorouracil into U2 snRNA blocks pseudouridylation and pre-mRNA splicing in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res 35: 550–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Li ZH, Terns RM, Terns MP, Yu YT. 2002. An H/ACA guide RNA directs U2 pseudouridylation at two different sites in the branchpoint recognition region in Xenopus oocytes. RNA 8: 1515–1525. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Patton JR, Ghosh SK, Fischel-Ghodsian N, Shen L, Spanjaard RA. 2007. Pus3p- and Pus1p-dependent pseudouridylation of steroid receptor RNA activator controls a functional switch that regulates nuclear receptor signaling. Mol Endocrinol 21: 686–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]